Submitted:

23 September 2023

Posted:

26 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

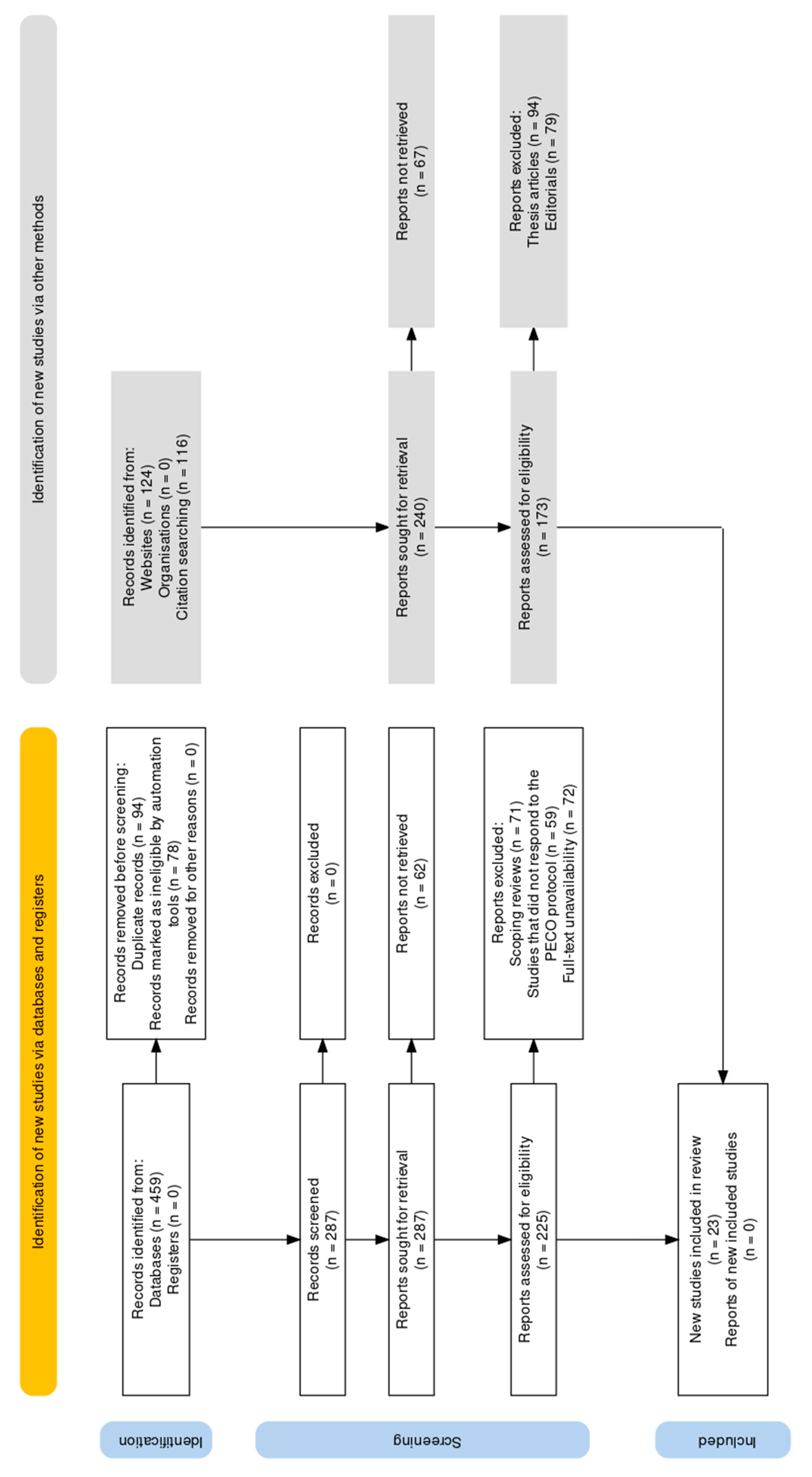

Review design and protocol

Search strategy

Selection protocol

Inclusion criteria:

- Study types: This systematic review considered a wide spectrum of research methodologies eligible for inclusion. These methodologies encompassed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, observational studies, experimental studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

- Population: The study population of interest included individuals diagnosed with CD or animal models of CD.

- Interventions: Included studies primarily focused on the evaluation or exploration of mitochondrial-based interventions. These interventions comprised various strategies, such as dietary interventions, exercise programs, pharmacological interventions, probiotics, and any approaches targeting mitochondrial function or dynamics.

- Outcomes: Eligible studies were required to report outcomes related to the effectiveness, safety, or influence of mitochondrial interventions on Crohn's disease (CD). The outcomes of interest encompassed alterations in both motor and non-motor symptoms, changes in quality of life, disease progression, biochemical markers, and any pertinent clinical assessments.

- Publication date: No constraints were placed on the publication date of the included studies.

Exclusion criteria:

- Case reports: Case reports were excluded from this systematic review to maintain a higher level of evidence and mitigate potential bias associated with single-case observations.

- Thesis articles: Articles originating from theses and unpublished theses themselves were excluded due to concerns regarding limited peer review and potential shortcomings in methodological rigor.

Data extraction

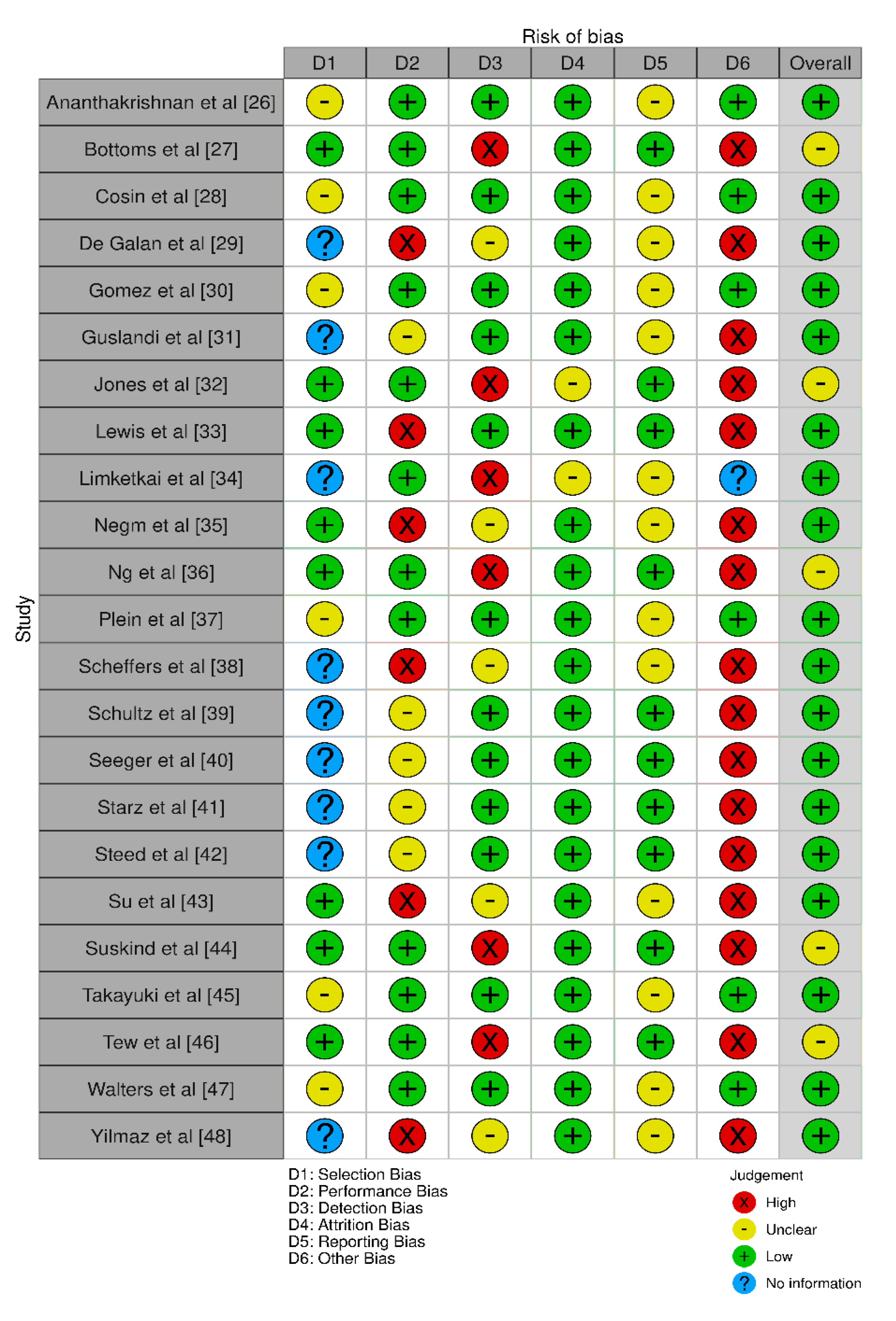

Bias assessment

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

References

- Colombel, J.F.; Panaccione, R.; Bossuyt, P.; Lukas, M.; Baert, F.; et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018, 390, 2779–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, N.L.; Rajeev, S.; Jayme, T.S.; Wang, A.; Keita, A.V.; et al. Crohn’s disease pathobiont adherent-invasive E coli disrupts epithelial mitochondrial networks with implications for gut permeability. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, A.; McGovern, D.P.; Barrett, J.C.; Wang, K.; Radford-Smith, G.L.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat. Gen. 2010, 42, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltekova, V.D.; Wintle, R.F.; Rubin, L.A.; Amos, C.I.; Huang, Q.; et al. Functional variants of OCTN cation transporter genes are associated with Crohn disease. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.; Barrett, J.C.; Prescott, N.J.; Tremelling, M.; Anderson, C.A.; et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugathasan, S.; Denson, L.A.; Walters, T.D.; Kim, M.O.; Marigorta, U.M.; et al. Prediction of complicated disease course for children newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease: a multicentre inception cohort study. Lancet 2017, 389, 1710–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottawea, W.; Chiang, C.K.; Muhlbauer, M.; Starr, A.E.; Butcher, J.; et al. Altered intestinal microbiotahost mitochondria crosstalk in new onset Crohn’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, J.D.; Olaison, G.; Peterson, K.H.; Franzén, L.E.; Lindmark, T.; et al. Augmented increase in tight junction permeability by luminal stimuli in the non-inflamed ileum of Crohn’s disease. Gut 2002, 50, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloian, S.; Rath, E.; Hammoudi, N.; Gleisinger, E.; Blutke, A.; et al. Mitochondrial impairment drives intestinal stem cell transition into dysfunctional Paneth cells predicting Crohn’s disease recurrence. Gut 2020, 69, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Esmaeilniakooshkghazi, A.; Patnaik, S.; Wang, Y.; George, S.P.; et al. Villin-1 and gelsolin regulate changes in actin dynamics that affect cell survival signaling pathways and intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1405–1420.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidrich, A.; Buzan, J.M.; Barnes, S.; Reuter, B.K.; Skaar, K.; et al. Altered epithelial cell lineage allocation and global expansion of the crypt epithelial stem cell population are associated with ileitis in SAMP1/YitFc mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, T.E.; Tomczak, M.F.; Niederreiter, L.; Ko, H.J.; Bock, J.; et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature 2013, 503, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, W.G.; Park, M.Y.; Maubert, M.; Engelman, R.W. SHIP deficiency causes Crohn’s disease-like ileitis. Gut 2011, 60, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkwirth, C.; Dargazanli, S.; Tatsuta, T.; Geimer, S.; Lower, B.; et al. Prohibitins control cell proliferation and apoptosis by regulating OPA1-dependent cristae morphogenesis in mitochondria. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijtmans, L.G.; de Jong, L.; Artal Sanz, M.; Coates, P.J.; Berden, J.A.; et al. Prohibitins act as a membrane-bound chaperone for the stabilization of mitochondrial proteins. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2444–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theiss, A.L.; Idell, R.D.; Srinivasan, S.; Klapproth, J.M.; Jones, D.P.; et al. Prohibitin protects against oxidative stress in intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, C.; Martini, E.; Wittkopf, N.; Amann, K.; Weigmann, B.; et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-α-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature 2011, 477, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Shen, J. The roles and functions of Paneth cells in Crohn’s disease: a critical review. Cell Prolif. 2020, 54, e12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.C.; Gao, F.; McGovern, D.P.; Stappenbeck, T.S. Spatial and temporal stability of Paneth cell phenotypes in Crohn’s disease: implications for prognostic cellular biomarker development. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.C.; Gurram, B.; Baldridge, M.T.; Head, R.; Lam, V.; et al. Paneth cell defects in Crohn’s disease patients promote dysbiosis. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e86907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.C.; Kern, J.T.; VanDussen, K.L.; Xiong, S.; Kaiko, G.E.; et al. Interaction between smoking and ATG16L1T300A triggers Paneth cell defects in Crohn’s disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 5110–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.C.; Naito, T.; Liu, Z.; VanDussen, K.L.; Haritunians, T.; et al. LRRK2 but not ATG16L1 is associated with Paneth cell defect in Japanese Crohn’s disease patients. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e91917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDussen, K.L.; Liu, T.C.; Li, D.; Towfic, F.; Modiano, N.; et al. Genetic variants synthesize to produce Paneth cell phenotypes that define subtypes of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.L.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Khalili, H.; Konijeti, G.G.; et al. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gut 2014, 63, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottoms, L.; Leighton, D.; Carpenter, R.; Anderson, S.; Langmead, L.; Ramage, J.; Faulkner, J.; Coleman, E.; Fairhurst, C.; Seed, M.; et al. Affective and enjoyment responses to 12 weeks of high intensity interval training and moderate continuous training in adults with Crohn's disease. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0222060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosin-Roger, J.; Simmen, S.; Melhem, H.; Atrott, K.; Frey-Wagner, I.; Hausmann, M.; de Vallière, C.; Spalinger, M.R.; Spielmann, P.; Wenger, R.H.; et al. Hypoxia ameliorates intestinal inflammation through NLRP3/mTOR downregulation and autophagy activation. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Galan, C.; De Vos, M.; Hindryckx, P.; Laukens, D.; Van Welden, S. Long-Term Environmental Hypoxia Exposure and Haematopoietic Prolyl Hydroxylase-1 Deletion Do Not Impact Experimental Crohn's Like Ileitis. Biology (Basel). 2021, 10, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ferrer, M.; Amaro-Prellezo, E.; Dorronsoro, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, R.; Vicente, Á.; Cosín-Roger, J.; Barrachina, M.D.; Baquero, M.C.; Valencia, J.; Sepúlveda, P. HIF-Overexpression and Pro-Inflammatory Priming in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Improves the Healing Properties of Extracellular Vesicles in Experimental Crohn's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 11269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guslandi, M.; Mezzi, G.; Sorghi, M.; Testoni, P.A. Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000, 45, 1462–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Baker, K.; Speight, R.A.; Thompson, N.P.; Tew, G.A. Randomised clinical trial: combined impact and resistance training in adults with stable Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020, 52, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.D.; Sandler, R.S.; Brotherton, C.; Brensinger, C.; Li, H.; Kappelman, M.D.; Daniel, S.G.; Bittinger, K.; Albenberg, L.; Valentine, J.F.; et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Specific Carbohydrate Diet to a Mediterranean Diet in Adults With Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021, 161, 837–852.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limketkai, B.N.; Akobeng, A.K.; Gordon, M.; Adepoju, A.A. Probiotics for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020, 7, CD006634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negm, M.; Bahaa, A.; Farrag, A.; et al. Effect of Ramadan intermittent fasting on inflammatory markers, disease severity, depression, and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: A prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol 2022, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, V.; Millard, W.; Lebrun, C.; Howard, J. Low-intensity exercise improves quality of life in patients with Crohn's disease. Clin J Sport Med. 2007, 17, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plein, K.; Hotz, J. Therapeutic effects of Saccharomyces boulardii on mild residual symptoms in a stable phase of Crohn's disease with special respect to chronic diarrhea--a pilot study. Z Gastroenterol. 1993, 31, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scheffers, L.E.; Vos, I.K.; Utens, E.M.W.J.; Dieleman, G.C.; Walet, S.; Escher, J.C.; van den Berg, L.E.M.; Rotterdam Exercise Team. Physical Training and Healthy Diet Improved Bowel Symptoms, Quality of Life, and Fatigue in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023, 77, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Timmer, A.; Herfarth, H.H.; Sartor, R.B.; Vanderhoof, J.A.; Rath, H.C. Lactobacillus GG in inducing and maintaining remission of Crohn's disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2004, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, W.A.; Thieringer, J.; Esters, P.; Allmendinger, B.; Stein, J.; Schulze, H.; Dignass, A. Moderate endurance and muscle training is beneficial and safe in patients with quiescent or mildly active Crohn's disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020, 8, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starz, E.; Wzorek, K.; Folwarski, M.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Stachowska, L.; Przewłócka, K.; Stachowska, E.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K. The Modification of the Gut Microbiota via Selected Specific Diets in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steed, H.; Macfarlane, G.T.; Blackett, K.L.; Bahrami, B.; Reynolds, N.; Walsh, S.V.; Cummings, J.H.; Macfarlane, S. Clinical trial: the microbiological and immunological effects of synbiotic consumption - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in active Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010, 32, 872–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Kang, Q.; Wang, H.; Yin, H.; Duan, L.; Liu, Y.; Fan, R. Effects of glucocorticoids combined with probiotics in treating Crohn's disease on inflammatory factors and intestinal microflora. Exp Ther Med. 2018, 16, 2999–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suskind, D.L.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y.-M.; Wahbeh, G.; Singh, N.; Braly, K.; Nuding, M.; Nicora, C.D.; Purvine, S.O.; Lipton, M.S.; et al. The Specific Carbohydrate Diet and Diet Modification as Induction Therapy for Pediatric Crohn’s Disease: A Randomized Diet Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Nakahigashi, M.; Umegae, S.; Kitagawa, T.; Matsumoto, K. Impact of Elemental Diet on Mucosal Inflammation in Patients with Active Crohn's Disease: Cytokine Production and Endoscopic and Histological Findings. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2005, 11, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, G.A.; Leighton, D.; Carpenter, R.; Anderson, S.; Langmead, L.; Ramage, J.; Faulkner, J.; Coleman, E.; Fairhurst, C.; Seed, M.; et al. High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training in adults with Crohn's disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.S.; Quiros, A.; Rolston, M.; Grishina, I.; Li, J.; Fenton, A.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Thai, A.; Andersen, G.L.; Papathakis, P.; et al. Analysis of Gut Microbiome and Diet Modification in Patients with Crohn's Disease. SOJ Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, İ.; Dolar, M.E.; Özpınar, H. Effect of administering kefir on the changes in fecal microbiota and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease: A randomized controlled trial. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019, 30, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, G.; Novak, E.A.; Siow, V.S.; Cunningham, K.E.; Griffith, B.D.; et al. Nix-mediated mitophagy modulates mitochondrial damage during intestinal inflammation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 33, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natl. Inst. Health. 2020. MARVEL: Mitochondrial Anti-oxidant Therapy to Resolve Inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis (MARVEL). Natl. Inst. Health, Washington, DC. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04276740.

- Gane, E.J.; Weilert, F.; Orr, D.W.; Keogh, G.F.; Gibson, M.; et al. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant mitoquinone decreases liver damage in a phase II study of hepatitis C patients. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, B.J.; Rolfe, F.L.; Lockhart, M.M.; Frampton, C.M.; O’Sullivan, J.D.; et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ as a disease-modifying therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletti, V.; Palermo, G.; Del Prete, E.; Mancuso, M.; Ceravolo, R. Understanding the multiple role of mitochondria in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders: lesson from genetics and protein-interaction network. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 636506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, M.; Li, K.; Beard, M.R.; Showalter, L.A.; Scholle, F.; et al. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, A.; Noe, N.; Tischner, C.; Kladt, N.; Lellek, V.; et al. Defining the action spectrum of potential PGC-1α activators on a mitochondrial and cellular level in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2400–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, N.L.; Goudie, L.; Xu, W.; Sabouny, R.; Rajeev, S.; et al. Perturbed mitochondrial dynamics is a novel feature of colitis that can be targeted to lessen disease. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadwell, K.; Patel, K.K.; Maloney, N.S.; Liu, T.C.; Ng, A.C.; et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn’s disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell 2010, 141, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogala, A.R.; Schoenborn, A.A.; Fee, B.E.; Cantillana, V.A.; Joyce, M.J.; et al. Environmental factors regulate Paneth cell phenotype and host susceptibility to intestinal inflammation in Irgm1-deficient mice. Dis. Model Mech. 2018, 11, dmm031070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Lapaquette, P.; Bringer, M.A.; Darfeuille-Michaud, A. Autophagy and Crohn’s disease. J. Innate Immun. 2013, 5, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Eun, H.S.; Jo, E.K. Roles of autophagy-related genes in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Cells 2019, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kaser, A.; et al. Paneth cell alertness to pathogens maintained by vitamin D receptors. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadwell, K.; Patel, K.K.; Komatsu, M.; Virgin, H.W.I.V.; Stappenbeck, T.S. A common role for Atg16L1, Atg5 and Atg7 in small intestinal Paneth cells and Crohn disease. Autophagy 2009, 5, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Intermittent Cold Exposure | Intermittent Heat Exposure | Evolutionary Based Foods | Intermittent Fasting | Circadian-Based Interventions | Fermented Drinks | Fermented Foods | Intermittent Hypercapnia | Intermittent Hypoxia | Intermittent Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| ScienceDirect | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| IEEE Xplore | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| PsycINFO | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| Web of Science | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| Embase | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| CINAHL | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| Scopus | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| Google Scholar | ("ice bath" OR "cold plunge" OR "whole body cryotherapy" OR "cryochamber") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("sauna" OR "infrared sauna") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("paleo diet" OR "paleolithic diet" OR "ketogenic diet" OR "carnivore diet") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("intermittent fasting" OR "caloric restriction" OR "fasting") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("bluelight therapy" OR "melatonin" OR "bright light therapy" OR "light therapy" OR "blue light blocker") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("probiotic drinks" OR "kefir" OR "kombucha" OR "ayran" OR "buttermilk") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("fermented foods" OR "miso" OR "natto" OR "Tempeh" OR "skyr" OR "strained yoghurt" OR "greek yoghurt") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("breath holding" OR "hypercapnia") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("ihht" OR "altitude training" OR "breath holding") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") | ("hiit" OR "high intensity interval training" OR "tabata" OR "interval training") AND ("Crohn’s disease" OR "Crohn’s") |

| Study | Aims | Study design | Methodology assessed | Type of mitochondrial intervention assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ananthakrishnan et al [26] | Investigate the association between dietary fat and risk of Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). | Prospective cohort study | Cox proportional hazards models | Long-chain n-3 PUFAs, trans-unsaturated fatty acids |

| Bottoms et al [27] | Explore affective and enjoyment responses to high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in adults with Crohn's disease (CD). | Randomized feasibility trial | Heart rate, ratings of perceived exertion (RPE-L and RPE-C), feeling state (FS), Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) | HIIT and MICT protocols |

| Cosin et al [28] | Investigate the role of hypoxia in regulating inflammation and autophagy in Crohn's disease patients and murine colitis models. | Experimental study | Measurement of inflammatory markers, autophagy, and NLRP3 expression | Hypoxia, HIF-1α activation, mTOR/NLRP3 pathway, autophagy |

| De Galan et al [29] | - Investigate the impact of environmental hypoxia and immune cell-specific deletion of oxygen sensor prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) 1 on Crohn's-like ileitis in mice. | Experimental mouse model | - Haematological assessment - Evaluation of distal ileal hypoxia via pimonidazole staining - Histological scoring and gene expression analysis - Comparison between TNF∆ARE/+ mice and Phd1-deficient TNF∆ARE/+ mice |

Environmental hypoxia, immune cell-specific Phd1-deletion |

| Gomez et al [30] | - Assess the therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) engineered to overexpress hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha and telomerase. | Experimental in vitro and in vivo studies | - Analysis of macrophage repolarization, cytokine release, and functional assays - Evaluation of anti-inflammatory effects on endothelium and fibrosis - Testing in a mouse colitis model | EVs derived from MSCs overexpressing HIF-1alpha and telomerase |

| Guslandi et al [31] | - Evaluate the role of Saccharomyces boulardii in the maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease in patients in clinical remission. | Randomized controlled trial | Comparison of clinical relapses based on CDAI values between patients receiving mesalamine alone and those receiving mesalamine plus Saccharomyces boulardii | Saccharomyces boulardii as a probiotic agent |

| Jones et al [32] | To assess the effect of 6 months of combined impact and resistance training on bone mineral density (BMD) and muscle function in adults with CD. | Randomized controlled trial with exercise and control groups. | - Measurement of BMD using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. - Assessment of muscle function including measures of upper and lower limb strength and endurance. - Evaluation of fatigue severity. |

Combined impact and resistance training program for 6 months. |

| Lewis et al [33] | To compare the effectiveness of the Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) to the Mediterranean diet (MD) as treatment for Crohn's disease (CD) with mild to moderate symptoms. | Randomized controlled trial comparing SCD and MD diets. | - Assessment of symptomatic remission at week 6. - Measurement of fecal calprotectin (FC) response. - Measurement of C-reactive protein (CRP) response. |

Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) and Mediterranean diet (MD). |

| Limketkai et al [34] | To assess the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the induction of remission in CD. | Inclusion of two studies involving probiotics and placebo groups. | - Assessment of remission induction in CD. - Evaluation of adverse events. |

Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG and synbiotic treatment. |

| Negm et al [35] | - Effect of IF during Ramadan on CD patients - Impact on clinical disease activity, quality of life, and depression |

Prospective study with IBD patients observing Ramadan fasting | - Serum CRP and stool calprotectin levels - Partial Mayo score - Harvey Bradshaw index - Simple IBD questionnaire |

Intermittent fasting (IF) during Ramadan |

| Ng et al [36] | - Effects of low-intensity walking on Crohn's disease patients' quality of life | Prospective study with exercise and nonexercise groups | - Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire - Inflammatory Bowel Disease Stress Index - Harvey-Bradshaw Simple Index |

Low-intensity walking program |

| Plein et al [37] | - Effects of Saccharomyces boulardii on Crohn's disease patients with diarrhea | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study | - Frequency of bowel movements - BEST Index | Saccharomyces boulardii (S.b.) yeast preparation |

| Scheffers et al [38] | Assess the effects of a 12-week lifestyle intervention in children with IBD. | Randomized semi-crossover controlled trial, lifestyle program (physical training + dietary advice) | Physical fitness, patient-reported outcomes, clinical disease activity, nutritional status | Lifestyle intervention (physical training + diet) |

| Schultz et al [39] | Determine the effect of oral Lactobacillus GG (L. GG) on inducing or maintaining medically induced remission in Crohn's disease. | Randomized placebo-controlled trial | Inducing or maintaining remission in Crohn's disease | Oral Lactobacillus GG (L. GG) |

| Seeger et al [40] | Examine and compare the safety, feasibility, and potential beneficial effects of individual moderate endurance and moderate muscle training in patients with Crohn's disease. | Random allocation to control, endurance, or muscle training group | Safety, feasibility, disease activity, inflammatory parameters, quality of life, physical activity, and strength | Moderate endurance and moderate muscle training |

| Starz et al [41] | Investigate the influence of reduction diets, including low-FODMAP diet and others, on the microbiome of patients with CD. | Review article | Effect of reduction diets (e.g., low-FODMAP, lactose-free, gluten-free) on gut microbiota composition and diversity. | Dietary interventions |

| Steed et al [42] | Investigate the effects of synbiotic consumption (Bifidobacterium longum and Synergy 1) on disease processes in patients with Crohn's disease. | Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial | Clinical outcomes, histological scores, immune marker transcription levels, mucosal bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy numbers. | Synbiotic supplementation (Bifidobacterium longum and Synergy 1) |

| Su et al [43] | Investigate the effect of glucocorticoids combined with probiotics on inflammatory factors and intestinal microflora in the treatment of Crohn's disease. | Randomized controlled trial (control group with oral sulfasalazine, treatment group with probiotics and glucocorticoids) | Clinical efficacy, changes in inflammatory factors, incidence of infection, changes in intestinal flora. | Combination of glucocorticoids and probiotics |

| Suskind et al [44] | To determine the potential efficacy of three versions of the specific carbohydrate diet (SCD) in active Crohn’s Disease. | 18 patients with mild/moderate CD were enrolled and randomized to SCD, modified SCD (MSCD), or whole foods (WF) diet. Evaluation at baseline, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks included PCDAI, inflammatory labs, and multi-omics evaluations. | Impact of SCD, MSCD, and WF diets on clinical remission, CRP levels, and microbiome composition. | Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD), Modified SCD (MSCD), Whole Foods (WF) Diet |

| Takayuki et al [45] | To examine the impact of elemental diet (Elental) on mucosal inflammation in Crohn's disease, mainly by cytokine measurements. | 28 consecutive patients with active CD were treated with Elental for 4 weeks. Mucosal biopsies were obtained before and after treatment. Control group consisted of 20 patients without inflammation. | Effect of elemental diet on clinical remission, endoscopic healing, histologic healing, and mucosal cytokine concentrations. | Elemental Diet (Elental) |

| Tew et al [46] | To assess the feasibility and acceptability of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in adults with Crohn's disease (CD). | Participants with quiescent or mildly-active CD were randomly assigned to HIIT, MICT, or usual care control. Feasibility outcomes included recruitment, retention, outcome completion, exercise attendance. Data collected on cardiorespiratory fitness, disease activity, and more. | Feasibility and acceptability of HIIT and MICT exercise training in adults with CD. | High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training (MICT) |

| Walters et al [47] | Develop methodology for fecal sample processing and detect changes in gut microbiota of Crohn’s disease patients receiving specialized diets | Pilot diet crossover trial comparing specific carbohydrate diet (SCD) vs. low residue diet (LRD) on gut microbiota composition and resolution of IBD symptoms. Assessment of gut microbiota using high-density DNA microarray PhyloChip. | DNA extraction using a column-based method, gut microbiota composition, microbial complexity, changes in B. fragilis abundance | Specialized carbohydrate diet (SCD) vs. low residue diet (LRD) |

| Yilmaz et al [48] | Investigate effects of kefir consumption on fecal microflora and symptoms of IBD patients | Single-center, prospective, open-label randomized controlled trial. Administration of 400 mL/day kefir to patients for 4 weeks. Assessment of stool Lactobacillus and Lactobacillus kefiri content by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. | Stool Lactobacillus and Lactobacillus kefiri content, abdominal pain, bloating, stool frequency, stool consistency, feeling good scores | Probiotic consumption |

| Study | Parameters Assessed | Inferences Observed | Results Observed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ananthakrishnan et al [26] | - Dietary fat intake (total fat, saturated fats, unsaturated fats, n-6 and n-3 PUFAs, trans-unsaturated fatty acids) - Risk of Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) |

- No association between cumulative energy-adjusted intake of various fats and risk of CD or UC. - High intake of long-chain n-3 PUFAs may be associated with a trend towards lower risk of UC. - High long-term intake of trans-unsaturated fatty acids may be associated with a trend towards an increased incidence of UC. |

- No significant association between various fat intake and CD or UC risk. - Long-chain n-3 PUFAs associated with a potential lower risk of UC. - Trans-unsaturated fatty acids potentially linked to increased UC incidence. |

| Bottoms et al [27] | - Heart rate (HR) - Ratings of perceived exertion for legs (RPE-L) and central (RPE-C) - Feeling state (FS) - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) - Affective and enjoyment responses to high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in adults with Crohn's disease (CD) |

- HR, RPE-L, and RPE-C were higher during HIIT compared to MICT. - FS scores were similar between HIIT and MICT. - No significant difference in PACES scores between HIIT and MICT. - Both HIIT and MICT protocols elicited similar enjoyment and affect in adults with quiescent or mildly-active CD. |

- HR during HIIT significantly greater than during MICT. - Higher RPE-L and RPE-C during HIIT compared to MICT. - Similar FS scores between HIIT and MICT. - No significant difference in PACES scores between HIIT and MICT. - HIIT and MICT both resulted in similar enjoyment and affect in CD patients. |

| Cosin et al [28] | - Expression of inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-6, NLRP3) - Autophagy modulation - Effects of hypoxia and dimethyloxalylglycine-mediated hydroxylase inhibition on inflammation - Role of mTOR/NLRP3 pathway in inflammation and autophagy regulation |

- Hypoxia reduces inflammatory markers and increases autophagy. - Hypoxia inhibits NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 expression. - Hypoxia counteracts inflammation by downregulating mTOR/NLRP3 pathway and promoting autophagy. - Hypoxia and HIF-1α activation are protective in mouse models of colitis. |

- Reduced expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and NLRP3 in response to hypoxia. - Increased autophagy and reduced NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 expression due to hypoxia. - Dimethyloxalylglycine-mediated hydroxylase inhibition ameliorates colitis and downregulates NLRP3 while promoting autophagy. - Hypoxia and HIF-1α activation are protective against colitis by inhibiting mTOR/NLRP3 pathway and promoting autophagy. |

| De Galan et al [29] | - Impact of environmental hypoxia and immune cell-specific deletion of oxygen sensor prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) 1 on Crohn's-like ileitis in mice. - Systemic inflammation assessed by haematology. - Distal ileal hypoxia evaluated by pimonidazole staining. - Histological scoring and gene expression analysis of ileitis. |

- Long-term environmental hypoxia or haematopoietic Phd1-deletion does not impact experimental ileitis development. - Hypoxia increases red blood cell count, haemoglobin, haematocrit, and pimonidazole intensity in the ileum. - Hypoxia leads to an increase in circulatory monocytes, ileal mononuclear phagocytes, and proinflammatory cytokine expression in WT mice. - No histological or ileal gene expression differences identified between TNF∆ARE/+ mice in hypoxia versus normoxia or between haematopoietic Phd1-deficient TNF∆ARE/+ and WT counterparts. |

- Long-term hypoxia or Phd1-deletion does not affect ileitis development. - Hypoxia-related changes in blood parameters and ileal hypoxia are observed. - Hypoxia induces an increase in circulatory monocytes, ileal mononuclear phagocytes, and proinflammatory cytokine expression in WT mice, but this does not translate into histological or gene expression differences in TNF∆ARE/+ mice. |

| Gomez et al [30] | - Effects of extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from MSCs engineered to overexpress HIF-1alpha and telomerase on M1 macrophages (Mφ1) repolarization. - Analysis of surface markers, cytokines, and functional assays in co-culture. - Anti-inflammatory effects on activated endothelium and fibrosis. - Therapeutic capacity in a mouse colitis model. |

- EVMSC-T-HIFc induces repolarization of monocytes from Mφ1 to an Mφ2-like phenotype with reduced inflammatory cytokine release. - EVMSC-T-HIFc-treated Mφ1 exhibits immunosuppressive effects similar to Mφ2 on activated PBMCs and reduces PBMC adhesion to activated endothelium. - EVMSC-T-HIFc prevents myofibroblast differentiation in TGF-β-treated fibroblasts. - EVMSC-T-HIFc administration promotes healing in a mouse colitis model. |

- EVMSC-T-HIFc effectively repolarizes Mφ1, reducing inflammatory cytokine release. - Immunomodulatory effects of EVMSC-T-HIFc are similar to Mφ2. - EVMSC-T-HIFc reduces PBMC adhesion to activated endothelium and prevents myofibroblast differentiation. - EVMSC-T-HIFc promotes healing in a mouse colitis model, preserving colon length and altering the Mφ1/Mφ2 ratio. |

| Guslandi et al [31] | - Role of Saccharomyces boulardii in the maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease in patients in clinical remission. - Clinical relapses assessed by CDAI values. |

- Saccharomyces boulardii may represent a useful tool in the maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease, as clinical relapses were less frequent in patients receiving mesalamine plus the probiotic agent. | - Clinical relapses as assessed by CDAI values were less frequent in patients treated with mesalamine plus Saccharomyces boulardii compared to those receiving mesalamine alone, suggesting a potential role for Saccharomyces boulardii in the maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease. |

| Jones et al [32] | - Bone mineral density (BMD) - Muscle function |

- Exercise intervention for 6 months improved BMD at the lumbar spine. - Exercise group had superior muscle function outcomes. - Lower fatigue severity observed in the exercise group. |

- BMD values were significantly higher in the exercise group at the lumbar spine. - Superior muscle function outcomes in the exercise group. - Lower fatigue severity in the exercise group. - Three exercise-related adverse events reported. |

| Lewis et al [33] | - Symptomatic remission - Fecal calprotectin (FC) response - C-reactive protein (CRP) response |

- Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) was not superior to the Mediterranean diet (MD) in achieving symptomatic remission. - No significant differences in FC and CRP responses between SCD and MD groups. |

- Symptomatic remission rates at week 6 were similar between SCD and MD groups. |

| Limketkai et al [34] | - Remission induction in CD - Adverse events |

- Probiotics did not show a significant difference compared to placebo in inducing remission in Crohn's disease (CD) after six months. | - No significant difference in remission induction between probiotics and placebo. - No significant difference in adverse events between probiotics and placebo. |

| Negm et al [35] | - Serum CRP and stool calprotectin levels - Partial Mayo score - Harvey Bradshaw index - Simple IBD questionnaire |

- No significant change in serum CRP and stool calprotectin levels - Significant rise in partial Mayo score after fasting - Older age and higher baseline calprotectin associated with higher Mayo score change |

- Serum CRP (median): 0.53 vs 0.50, P = 0.27 - Calprotectin (median): 163 vs 218, P = 0.62 - Partial Mayo score (median): 1 vs 1, P = 0.02 - Harvey-Bradshaw index (median): 4 vs 5, P = 0.4 - Worsening clinical parameters in UC patients, more pronounced in older patients and those with higher baseline calprotectin levels |

| Ng et al [36] | - Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire - Inflammatory Bowel Disease Stress Index - Harvey-Bradshaw Simple Index |

- Statistically significant improvement in quality of life in all 3 outcome measurement questionnaires - No detrimental effects on disease activity |

- Exercise group showed significant improvement in quality of life based on the mentioned questionnaires (P < 0.05) |

| Plein et al [37] | - Frequency of bowel movements - BEST Index | - Reduction in the frequency of bowel movements and BEST Index as compared to baseline - S.b. group showed significant reduction in frequency of bowel movements and BEST Index - No adverse drug events observed |

- Frequency of bowel movements (evacuations/day): 5.0 +/- 1.4 vs 4.1 +/- 2.3, p < 0.01 - BEST Index: 193 +/- 32 vs 168 +/- 59, p < 0.05 - S.b. group had reduced frequency of bowel movements and BEST Index in the tenth week (3.3 +/- 1.2 evacuations/day and 107 +/- 85) - Control group did not show this effect; values returned to initial levels |

| Scheffers et al [38] | Physical fitness (maximal and submaximal exercise capacity, strength, core stability), patient-reported outcomes, clinical disease activity, nutritional status | 12-week lifestyle intervention improved bowel symptoms, quality of life, and fatigue in pediatric IBD patients. | - Peak VO2 did not change significantly after the 12-week program. - Exercise capacity measured by 6-minute walking test and core stability improved. - Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index decreased significantly. - Fecal calprotectin decreased significantly. - Quality of life (IMPACT-III) improved on 4 out of 6 domains and total score. - Parents-reported quality of life and total fatigue score also improved significantly. |

| Schultz et al [39] | Effect of oral Lactobacillus GG (L. GG) on inducing or maintaining medically induced remission in Crohn's disease. | L. GG did not demonstrate a benefit in inducing or maintaining medically induced remission in Crohn's disease. | - 5 out of 11 patients finished the study. - Median time to relapse was not significantly different between L. GG and placebo groups. |

| Seeger et al [40] | Safety, feasibility, and potential beneficial effects of individual moderate endurance and moderate muscle training in patients with Crohn's disease. | Both individual moderate endurance and muscle training can be safely performed in patients with mild or quiescent Crohn's disease. | - Higher dropout rate in the endurance group compared to the muscle group. - Maximal and average strength in upper and lower extremities increased significantly in both groups. - Emotional function significantly improved in the endurance group. - No statistically significant changes in disease activity or other outcome parameters in this pilot cohort. |

| Starz et al [41] | Influence of reduction diets (e.g., low-FODMAP, lactose-free, gluten-free) on the gut microbiota composition and diversity. | Reduction diets may lead to decreased abundance of beneficial microbial species (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) and reduced microbial diversity. CDED (Crohn’s disease exclusion diet) with partial enteral nutrition has a positive influence on the microbiota. | Reduction diets, including low-FODMAP, lactose-free, and gluten-free diets, negatively affect microbial diversity and the abundance of beneficial microbial species. CDED improves microbiota and may impact the future course of the disease. |

| Steed et al [42] | Clinical outcomes, histological scores, immune marker transcription levels, mucosal bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy numbers. | Synbiotic consumption (Bifidobacterium longum and Synergy 1) improves clinical outcomes, reduces Crohn's disease activity indices, and histological scores. It has a limited effect on certain immune markers (IL-18, INF-gamma, IL-1beta) but reduces TNF-alpha expression at 3 months. Mucosal bifidobacteria increase in synbiotic patients. | Synbiotic consumption (Bifidobacterium longum and Synergy 1) is effective in improving clinical symptoms, reducing disease activity indices, and histological scores in patients with active Crohn's disease. It leads to changes in specific immune markers and an increase in mucosal bifidobacteria. |

| Su et al [43] | Clinical efficacy, changes in inflammatory factors, incidence of infection, changes in intestinal flora. | Combination of probiotics and glucocorticoids in the treatment of Crohn's disease improves clinical curative effect, reduces the secretion of inflammatory factors, and enhances intestinal flora (e.g., increased lactobacillus and reduced yeast, enterococci, and peptococcus). Treatment group exhibits significantly higher treatment efficiency and lower infection rate compared to the control group. | Combining probiotics with glucocorticoids in Crohn's disease treatment results in improved clinical outcomes, reduced inflammatory factors, and positive changes in intestinal flora composition. The treatment group shows better treatment efficiency and lower infection rates compared to conventional treatment methods. |

| Suskind et al [44] | PCDAI, inflammatory labs, multi-omics evaluations | At week 12, all participants (n = 10) who completed the study achieved clinical remission. The C-reactive protein (CRP) levels decreased significantly in all three diet groups (SCD, MSCD, and WF). The microbiome composition shifted in all patients across the study period, with consistent changes in the predicted metabolic mode of organisms. | Clinical remission achieved in all participants. Significant reduction in CRP levels. Shifts in microbiome composition. |

| Takayuki et al [45] | Mucosal cytokine concentrations (IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) | Clinical remission achieved in 71% of patients. Endoscopic healing and improvement rates were observed in the terminal ileum and large bowel. Histologic healing and improvement rates were also observed. Changes in mucosal cytokine concentrations, specifically a decrease after treatment. Correction of the IL-1ra/IL-1β ratio. | Clinical remission, endoscopic healing, and histologic healing observed. Reduction in mucosal cytokine levels. Correction of IL-1ra/IL-1β ratio. |

| Tew et al [46] | Feasibility outcomes (recruitment, retention, outcome completion, etc.), cardiorespiratory fitness, disease activity, quality of life, adverse events, intervention acceptability | High attendance and completion rates for both HIIT and MICT groups. Mean increase in peak oxygen uptake was greater following HIIT than MICT. Few non-serious exercise-related adverse events, and some participants experienced disease relapse during follow-up. | High feasibility and acceptability of HIIT and MICT exercise training. Greater improvement in peak oxygen uptake with HIIT. Some adverse events and disease relapses observed. |

| Walters et al [47] | Gut microbiota composition, microbial complexity, abundance of Bacteroides fragilis | Lower gut microbiome complexity in IBD patients compared to healthy controls. Increased abundance of B. fragilis in fecal samples from IBD patients. Changes in gut microbiome composition and complexity in response to specialized carbohydrate diet (SCD). SCD associated with restructuring of gut microbial communities. | - The complexity of the gut microbiome was lower in IBD patients. - Increased abundance of B. fragilis in fecal samples of IBD-positive patients. - Temporal response to SCD resulted in increased microbial diversity. - LRD diet associated with reduced diversity of microbial communities. - Changes in composition and complexity of the gut microbiome observed in response to specialized carbohydrate diet. |

| Yilmaz et al [48] | Stool Lactobacillus, Lactobacillus kefiri content, abdominal symptoms, feeling good scores | Kefir consumption may modulate gut microbiota. Significant decrease in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in patients with CD. Increased hemoglobin levels. Bloating scores significantly reduced in the last 2 weeks of the study. Increased feeling good scores. | - Stool Lactobacillus bacterial load in treatment group between 104 and 109 CFU/g. - Significant reductions in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in CD patients. - Increased hemoglobin levels. - Reduction in bloating scores during the last 2 weeks. - Improvement in feeling good scores. - Kefir consumption may improve patient's quality of life in the short term. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).