Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of MIL-88A(Fe)

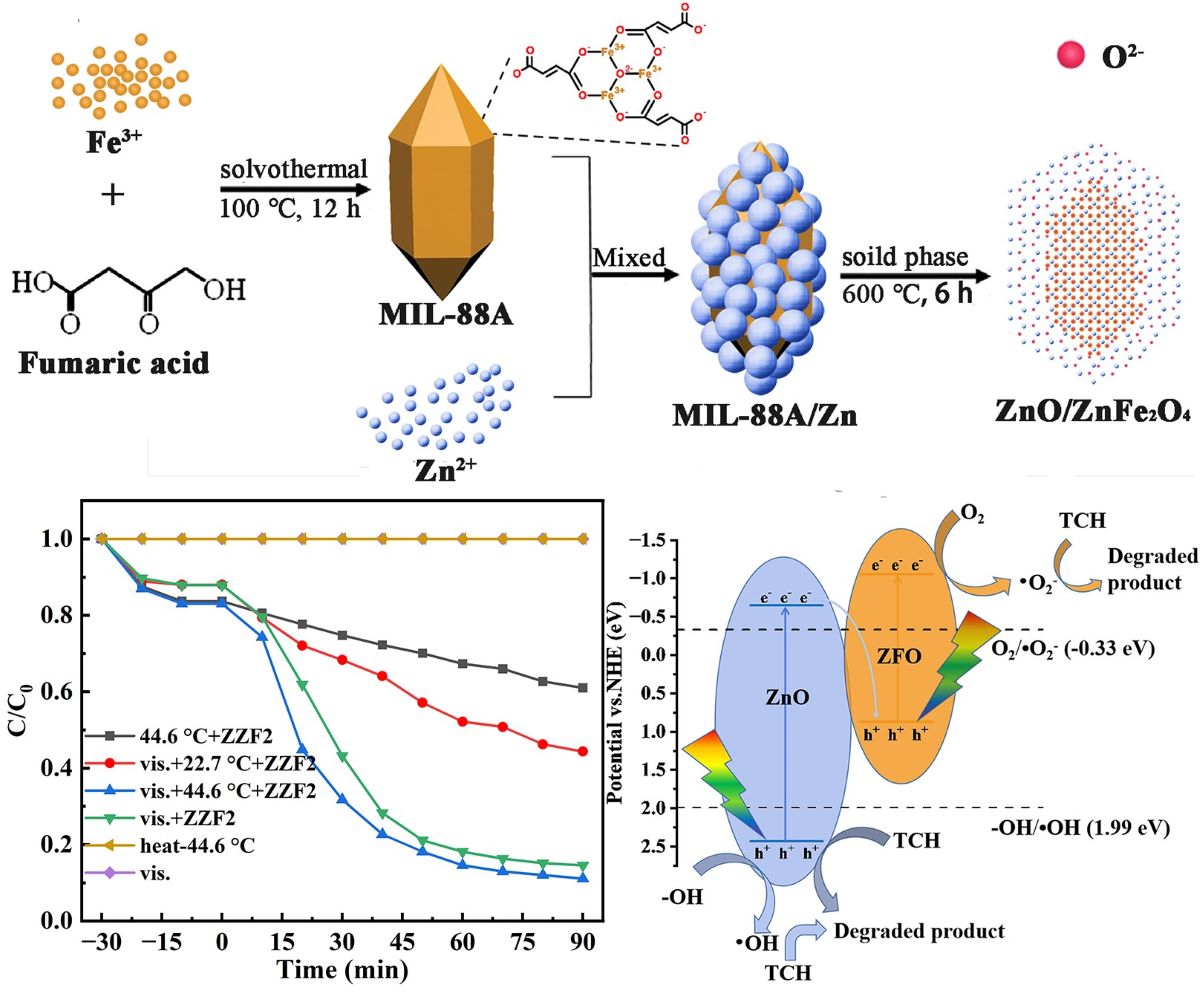

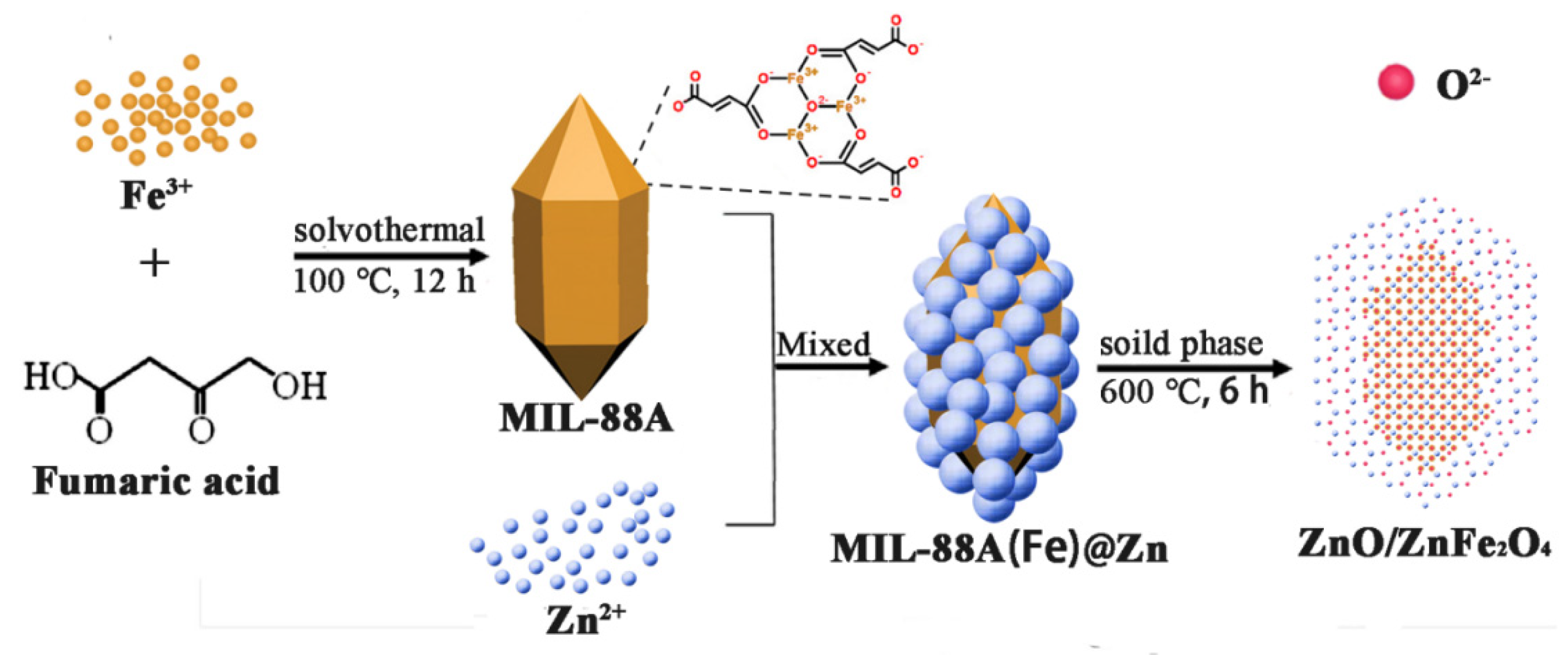

2.3. Preparation of ZnO/ZnFe2O4

2.4. Photocatalyst Characterizations, Photocatalytic (Photoelectrochemical) Test, and Photothermal Conversion Performance

3. Results and Discussion

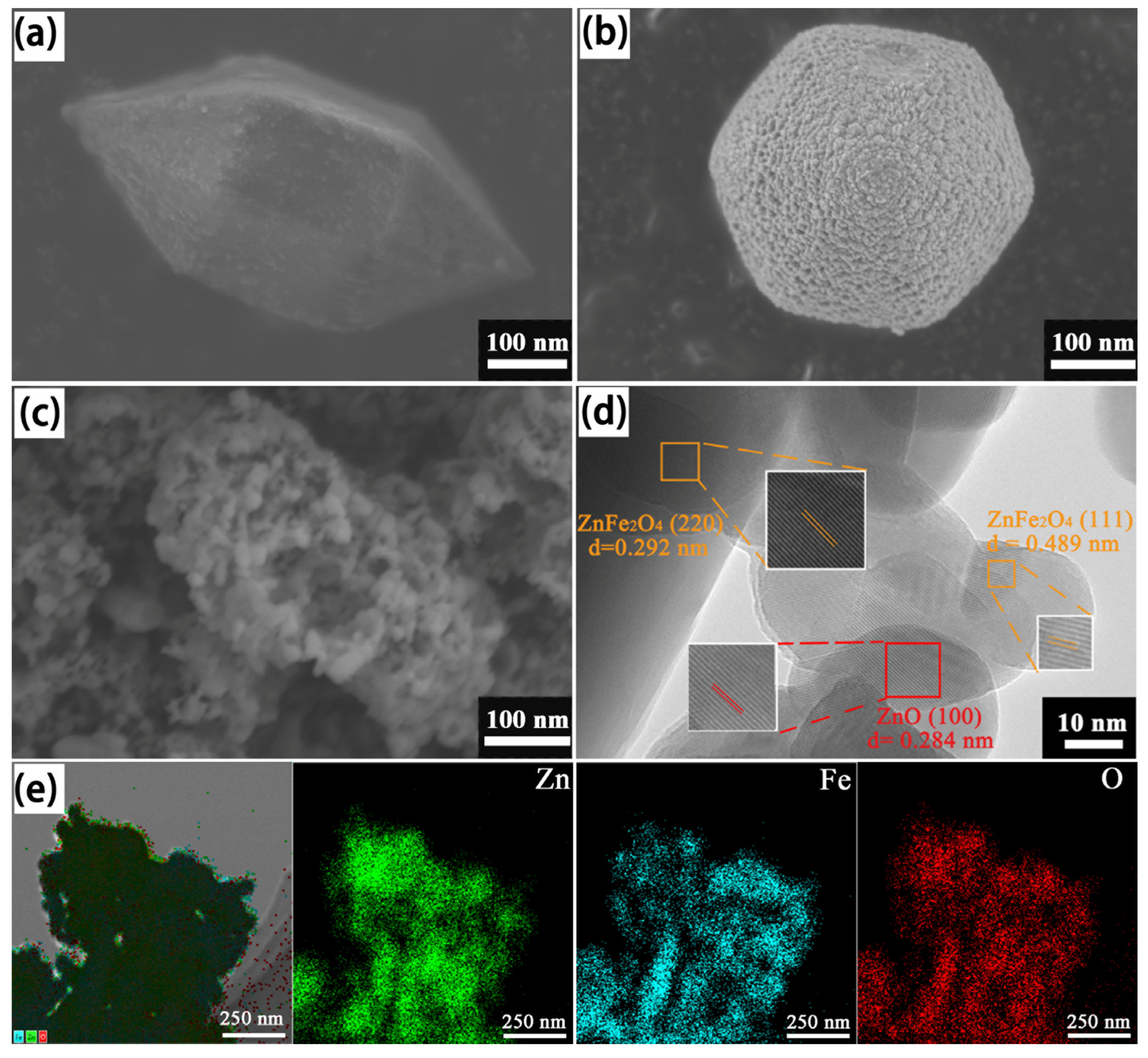

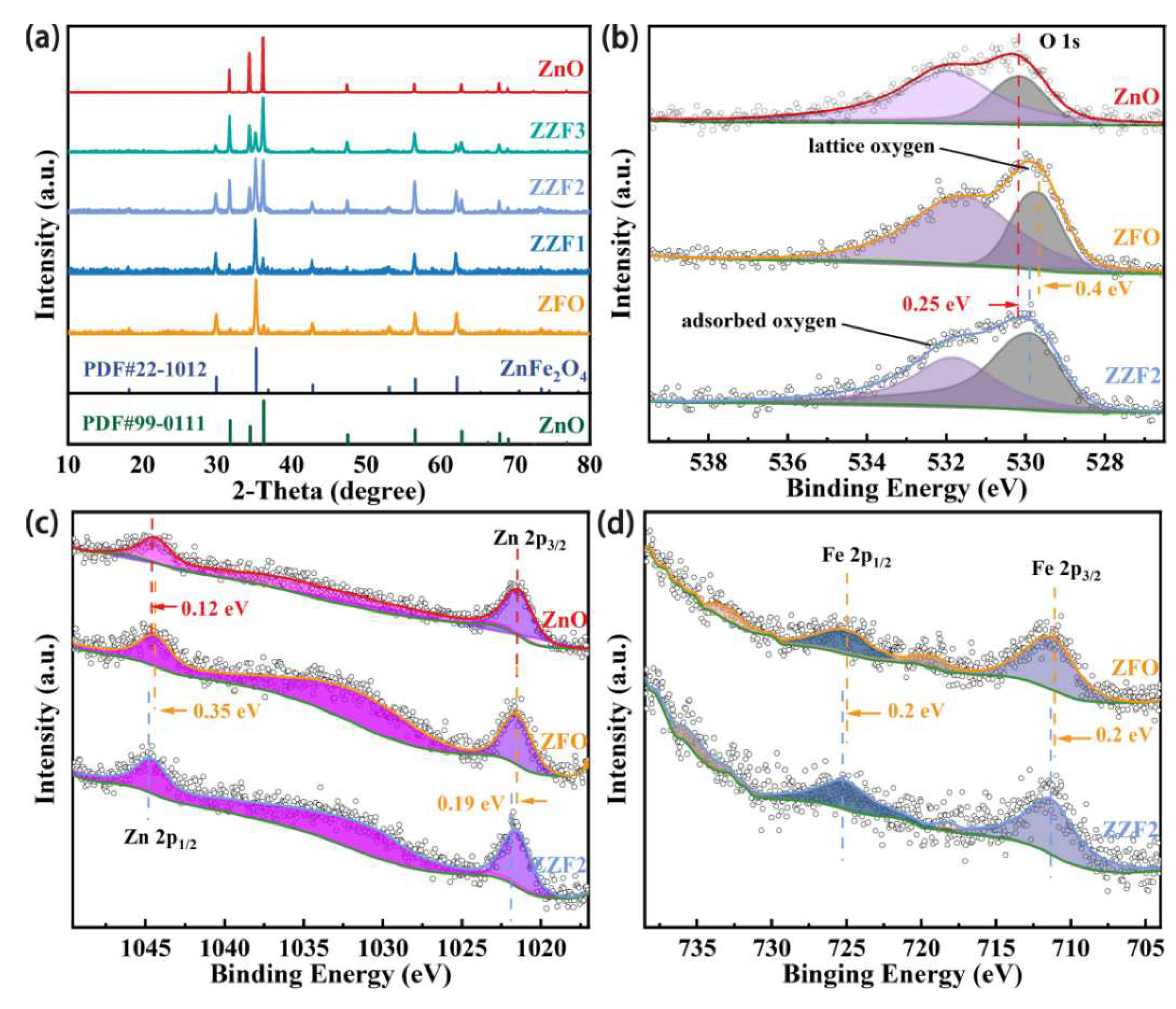

3.1. Morphology and Structure

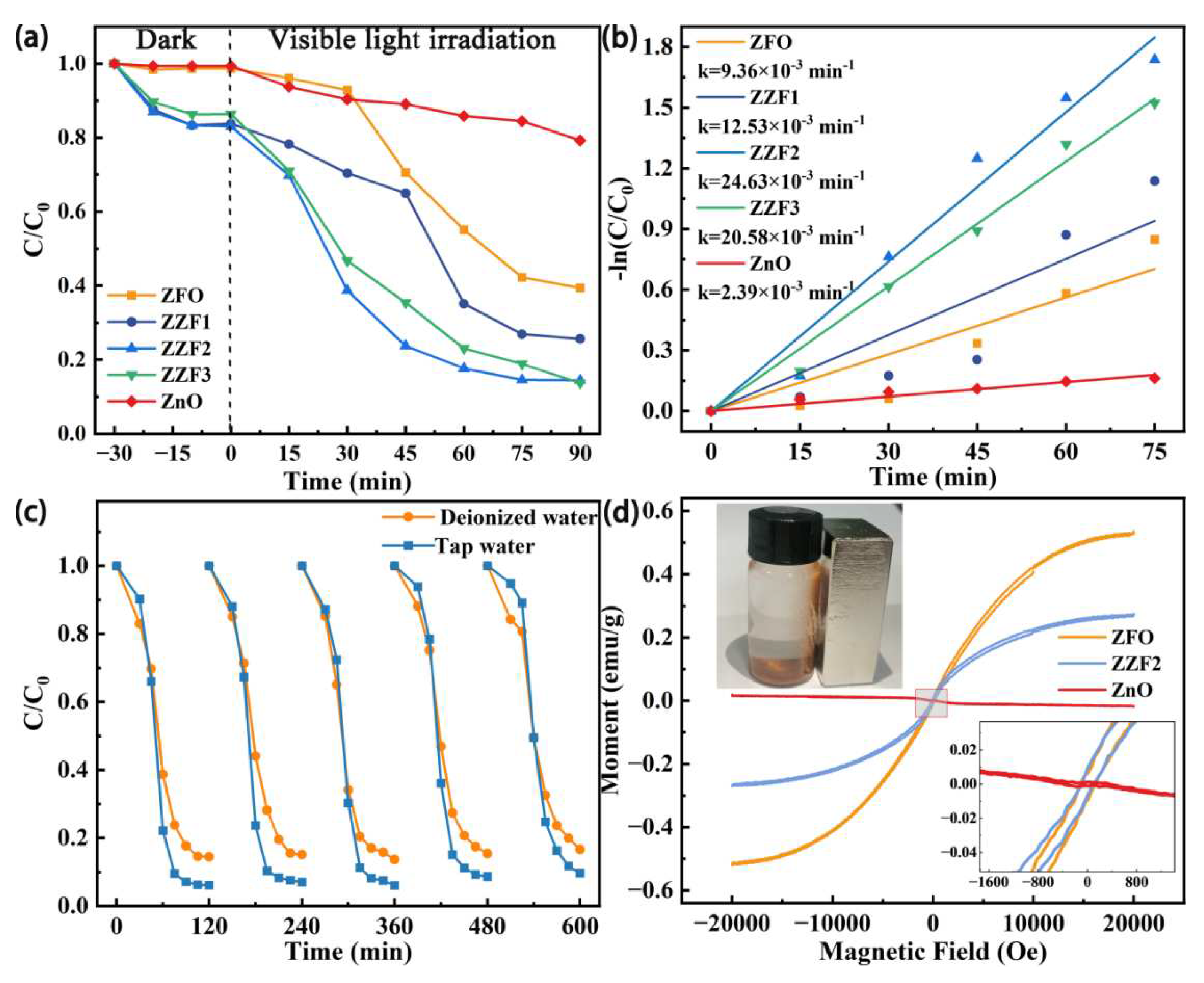

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity and Reusability

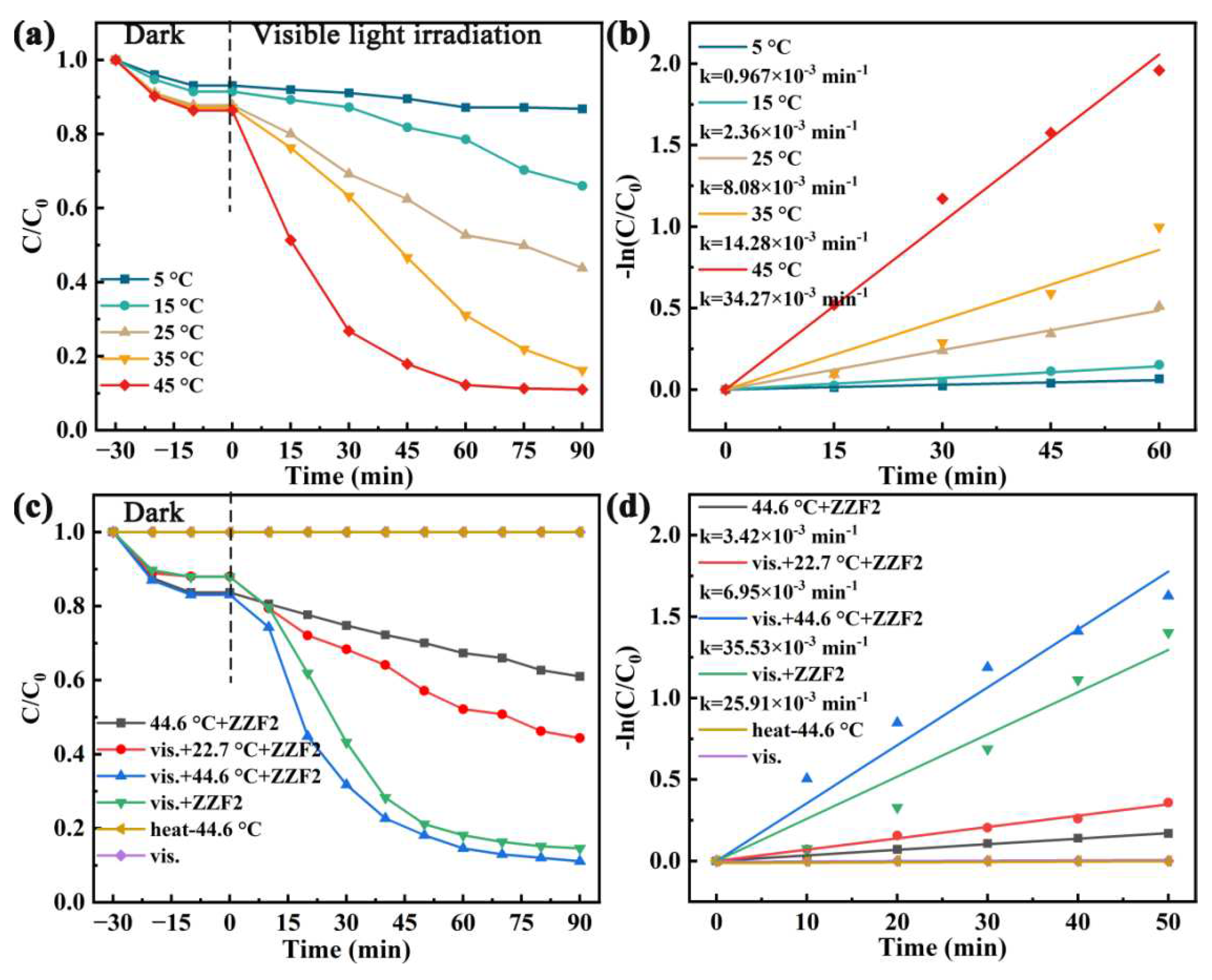

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Catalytic Effect

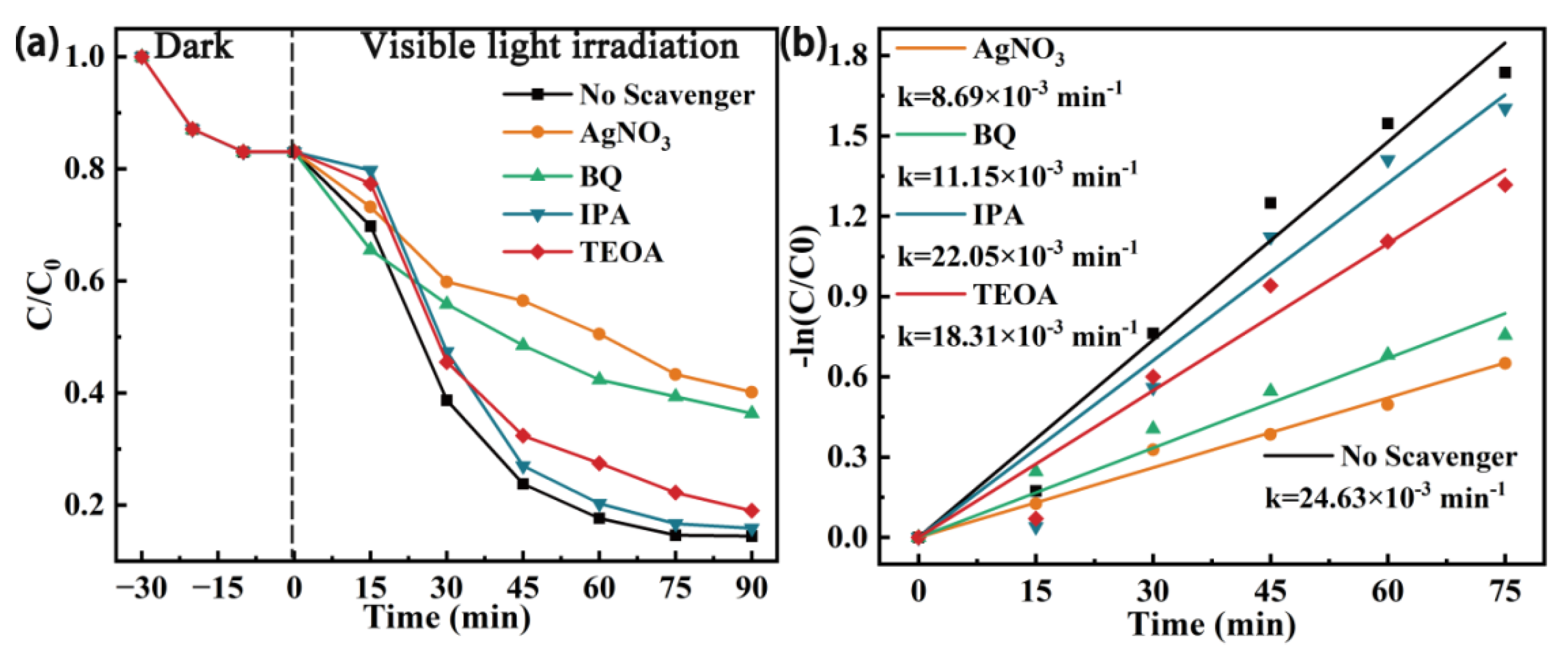

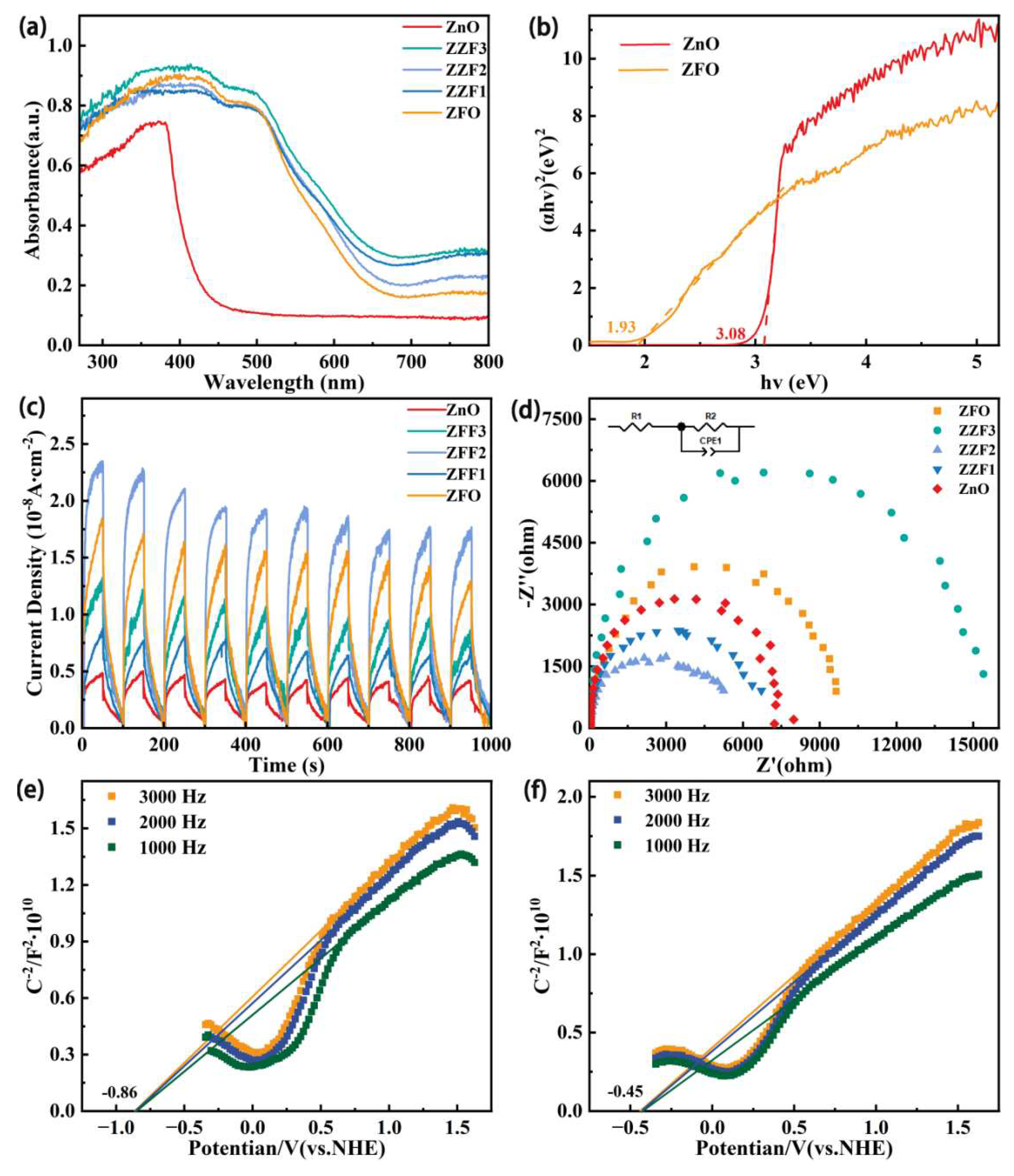

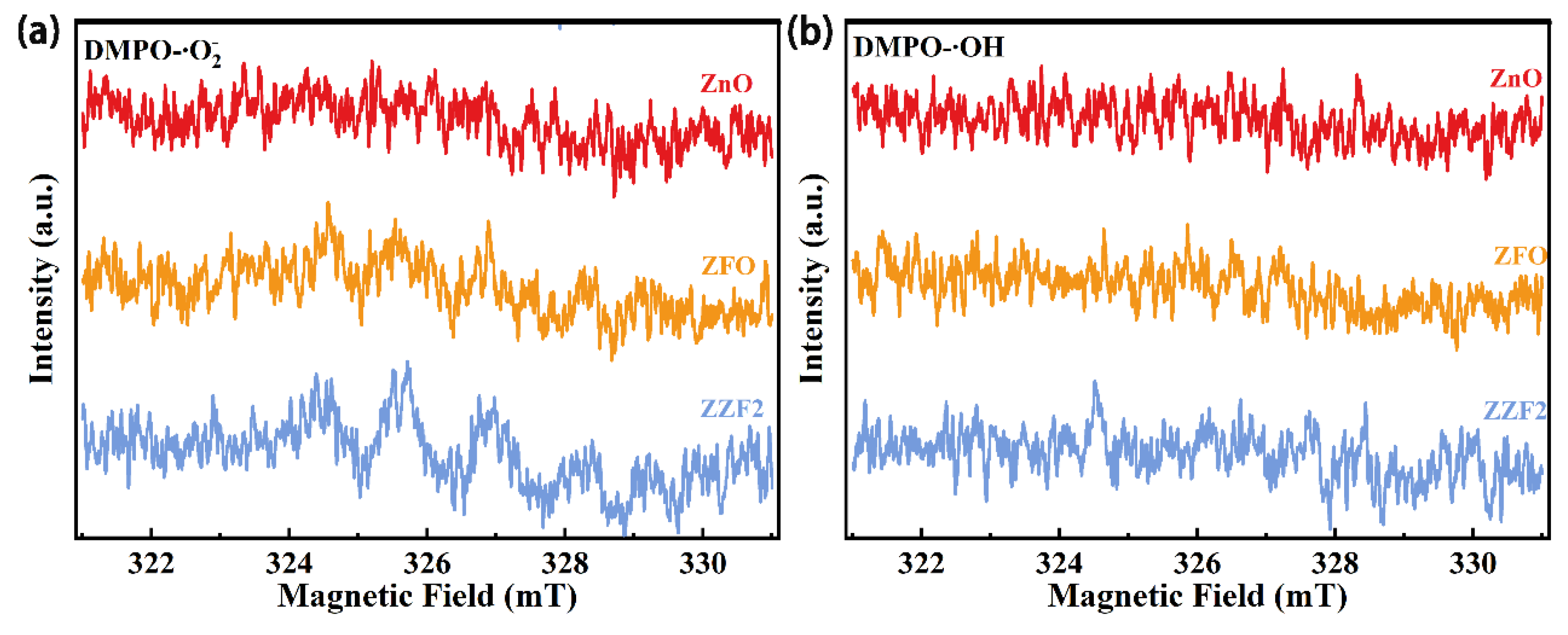

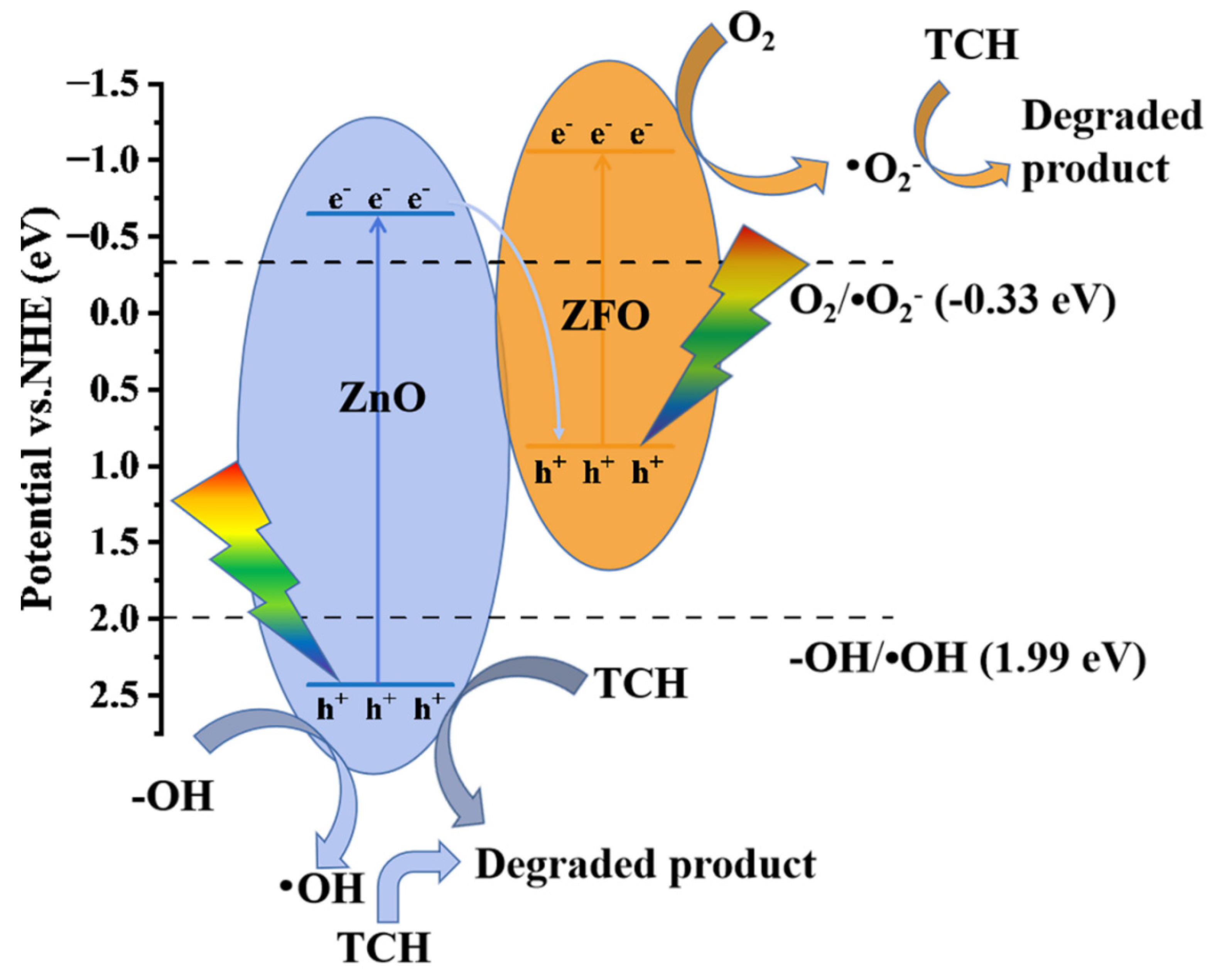

3.4. Analysis of the Photocatalytic Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. Daghrir, P. Drogui, Tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: a review, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2013, 11(3), 209-227. [CrossRef]

- N. Barhoumi, N. Oturan, S. Ammar, A. Gadri, M.A. Oturan, E. Brillas, Enhanced degradation of the antibiotic tetracycline by heterogeneous electro-Fenton with pyrite catalysis, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2017, 15(4), 689-693. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. Yamashita, H. Tanaka, Performance of UV and UV/H2O2 processes for the removal of pharmaceuticals detected in secondary effluent of a sewage treatment plant in Japan, J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 166(2), 1134-1140. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Liu, Y. Yang, J. Kang, M.H. Fan, J.H. Qu, Removal of tetracycline from water by Fe-Mn binary oxide, J. Environ. Sci., 2012, 24(2), 242-247. [CrossRef]

- J.J. López-Peñalver, M. Sánchez-Polo, C.V. Gómez-Pacheco, J. Rivera-Utrilla, Photodegradation of tetracyclines in aqueous solution by using UV and UV/H2O2 oxidation processes, J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol., 2010, 85(10), 1325-1333. [CrossRef]

- D. Akhil, D. Lakshmi, P.S. Kumar, D.V.N. Vo, A. Kartik, Occurrence and removal of antibiotics from industrial wastewater, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2021, 19(2), 1477-1507. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Liu, B. Li, J. Wu, Y.X. Liu, Photocatalytic oxidation removal of elemental mercury from flue gas. A review, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2020, 18(2), 417-431. [CrossRef]

- A. Saravanan, P.S. Kumar, D.V.N. Vo, P.R. Yaashikaa, S. Karishma, S. Jeevanantham, B. Gayathri, V.D. Bharathi, Photocatalysis for removal of environmental pollutants and fuel production: a review, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2021, 19(1), 441-463. [CrossRef]

- X.M. Peng, W.D. Luo, J.Q. Wu, F.P. Hu, Y.Y. Hu, L. Xu, G.P. Xu, Y. Jian, H.L. Dai, Carbon quantum dots decorated heteroatom co-doped core-shell Fe-0@POCN for degradation of tetracycline via multiply synergistic mechanisms, Chemosphere, 2021, 268. [CrossRef]

- X.B. Li, J. Xiong, X.M. Gao, J. Ma, Z. Chen, B.B. Kang, J.Y. Liu, H. Li, Z.J. Feng, J.T. Huang, Novel BP/BiOBr S-scheme nano-heterojunction for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic tetracycline removal and oxygen evolution activity, J. Hazard. Mater., 2020, 387. [CrossRef]

- B. Louangsouphom, X. Wang, J. Song, X. Wang, Low-temperature preparation of a N-TiO2/macroporous resin photocatalyst to degrade organic pollutants, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2019, 17(2), 1061-1066. [CrossRef]

- J.X. Low, B.Z. Dai, T. Tong, C.J. Jiang, J.G. Yu, In Situ Irradiated X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Investigation on a Direct Z-Scheme TiO2/CdS Composite Film Photocatalyst, Adv. Mater., 2019, 31(6). [CrossRef]

- S.Y. Fang, Y.H. Hu, Thermo-photo catalysis: a whole greater than the sum of its parts, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2022, 51(9), 3609-3647. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiong, L. Huang, S. Mahmud, F. Yang, H. Liu, Bio-synthesized palladium nanoparticles using alginate for catalytic degradation of azo-dyes, Chin. J. Chem. Eng., 2020, 28(5), 1334-1343. [CrossRef]

- X.M. Jia, Q.F. Han, H.N. Liu, S.Z. Li, H.P. Bi, A dual strategy to construct flowerlike S-scheme BiOBr/BiOAc1-xBrx heterojunction with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity, Chem. Eng. J., 2020, 399. [CrossRef]

- X.H. He, T.H. Kai, P. Ding, Heterojunction photocatalysts for degradation of the tetracycline antibiotic: a review, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2021, 19(6), 4563-4601. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, S. Du, Y. Wang, Z. Han, X. Li, G. Li, Q. Hu, H. Xu, C. He, P. Fang, Synergy of yolk-shelled structure and tunable oxygen defect over CdS/CdCO3-CoS2: Wide band-gap semiconductors assist in efficient visible-light-driven H2 production and CO2 reduction, Chem. Eng. J., 2023, 454 140113. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, S. Du, Y. Wang, Z. Han, W. Ma, H. Xu, Y. Lei, P. Fang, Metal-organic coordination polymers-derived ultra-small MoC nanodot/N-doped carbon combined with CdS: A hollow Z-type catalyst for stable and efficient H2 production/CO2 reduction, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2023, 608 155176. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, F. Zhang, M. Yang, P. Fang, POSS modified NixOy-decorated TiO2 nanosheets: Nanocomposites for adsorption and photocatalysis, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2021, 566 150604. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, S. Du, Z. Han, Y. Wang, T. Jiang, S. Wu, C. Chen, Q. Han, S. Suo, H. Xu, F. Ren, P. Fang, Ohmic-functionalized type I heterojunction: Improved alkaline water splitting and photocatalytic conversion from CO2 to C2H2, Chem. Eng. J., 2023, 144438. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiong, H. Wan, M. Islam, W. Wang, L. Xie, S. Lü, S.M.F. Kabir, H. Liu, S. Mahmud, Hyaluronate macromolecules assist bioreduction (AuIII to Au0) and stabilization of catalytically active gold nanoparticles for azo contaminated wastewater treatment, Environ. Technol. Innov., 2021, 24 102053. [CrossRef]

- W. Zeng, A. Gui, X. He, M. Tang, X. Zhang, X. He, Y. Hu, K. Di, Y. Dong, Y. Xiong, P. Fang, H. Sang, Z. Chen, P. Gui, Van der Waals Black Phosphorus/Bi10O6S9 Heterojunction Harvesting Ambient Electric Field Energy for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Sense, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2023, 127(2), 1229-1243. [CrossRef]

- W. Ma, M. Du, H. Li, Y. Wang, Z. Han, C. Chen, S. Zhang, Q. Han, Y. Li, J. Fang, P. Fang, The binary piezoelectric synergistic effect of KNbO3/MoS2 heterojunction for improving photocatalytic performance, J. Alloy. Compd., 2023, 960 170669. [CrossRef]

- F. Guo, W. Shi, M. Li, Y. Shi, H. Wen, 2D/2D Z-scheme heterojunction of CuInS2/g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity towards the degradation of tetracycline, Sep. Purif. Technol., 2019, 210 608-615. [CrossRef]

- B. Han, Y.H. Hu, Highly Efficient Temperature-Induced Visible Light Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Water, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119(33), 18927-18934. [CrossRef]

- Y.X. Li, M.M. Wen, Y. Wang, G. Tian, C.Y. Wang, J.C. Zhao, Plasmonic Hot Electrons from Oxygen Vacancies for Infrared Light-Driven Catalytic CO2 Reduction on Bi2O3-x, Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit., 2021, 60(2), 910-916. [CrossRef]

- Z.L. Ma, W. Liu, W. Yang, W.C. Li, B. Han, Temperature effects on redox potentials and implications to semiconductor photocatalysis, fuel, 2021, 286. [CrossRef]

- B. Han, Y.H. Hu, Highly Efficient Temperature-Induced Visible Light Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Water, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119(33), 18927-18934. [CrossRef]

- S. Rej, L. Mascaretti, E.Y. Santiago, O. Tomanec, Š. Kment, Z. Wang, R. Zbořil, P. Fornasiero, A.O. Govorov, A. Naldoni, Determining Plasmonic Hot Electrons and Photothermal Effects during H2 Evolution with TiN–Pt Nanohybrids, ACS Catal., 2020, 10(9), 5261-5271. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Li, X.Q. Yang, C.R. Ma, Y. Lei, Z.Y. Cheng, Z.B. Rui, Selectively recombining the photoinduced charges in bandgap-broken Ag3PO4/GdCrO3 with a plasmonic Ag bridge for efficient photothermocatalytic VOCs degradation and CO2 reduction, Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2021, 291. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Kong, C.L. Jiang, Z.B. Rui, S.H. Liu, F.L. Xian, W.K. Ji, H.B. Ji, Photothermocatalytic synergistic oxidation: An effective way to overcome the negative water effect on supported noble metal catalysts for VOCs oxidation, Chem. Eng. J., 2020, 397. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang, C.H. Li, H.J. Chen, R.B. Jiang, L.D. Sun, Q. Li, J.F. Wang, J.C. Yu, C.H. Yan, Plasmonic Harvesting of Light Energy for Suzuki Coupling Reactions, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2013, 135(15), 5588-5601. [CrossRef]

- Z.Z. Lou, Q. Gu, Y.S. Liao, S.J. Yu, C. Xue, Promoting Pd-catalyzed Suzuki coupling reactions through near-infrared plasmon excitation of WO3-x nanowires, Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2016, 184 258-263. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarina, H.Y. Zhu, Q. Xiao, E. Jaatinen, J.F. Jia, Y.M. Huang, Z.F. Zheng, H.S. Wu, Viable Photocatalysts under Solar-Spectrum Irradiation: Nonplasmonic Metal Nanoparticles, Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit., 2014, 53(11), 2935-2940. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Wang, Y. Wang, Y. Cheng, Z.F. Liu, Q.S. Guo, M.N. Ha, Z. Zhao, Hydrogen-treated mesoporous WO3 as a reducing agent of CO2 to fuels (CH4 and CH3OH) with enhanced photothermal catalytic performance, J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, 4(14), 5314-5322. [CrossRef]

- X.B. Chen, L. Liu, P.Y. Yu, S.S. Mao, Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals, Science, 2011, 331(6018), 746-750. [CrossRef]

- B. Han, W. Wei, L. Chang, P.F. Cheng, Y.H. Hu, Efficient Visible Light Photocatalytic CO2 Reforming of CH4, ACS Catal., 2016, 6(2), 494-497. [CrossRef]

- S.Y. Fang, W. Zhang, K. Sun, Y.H. Hu, Highly efficient thermo-photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline catalyzed by tungsten disulfide under visible light, Environ. Chem. Lett., 2023, 21(3), 1287-1295. [CrossRef]

- X.H. Zhang, B.Y. Lin, X.Y. Li, X. Wang, K.Z. Huang, Z.H. Chen, MOF-derived magnetically recoverable Z-scheme ZnFe2O4/Fe2O3 perforated nanotube for efficient photocatalytic ciprofloxacin removal, Chem. Eng. J., 2022, 430. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhang, H.Y. Cao, A. Dar, D.Q. Li, L.A. Zhou, C.Y. Wang, Construction of oxygen defective ZnO/ZnFe2O4 yolk-shell composite with photothermal effect for tetracycline degradation: Performance and mechanism insight, Chin. Chem. Lett., 2023, 34(1). [CrossRef]

- Y.Y. Fang, Q.W. Liang, Y. Li, H.J. Luo, Surface oxygen vacancies and carbon dopant co-decorated magnetic ZnFe2O4 as photo-Fenton catalyst towards efficient degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride, Chemosphere, 2022, 302. [CrossRef]

- N. Nasseh, L. Taghavi, B. Barikbin, M.A. Nasseri, Synthesis and characterizations of a novel FeNi3/SiO2/CuS magnetic nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in simulated wastewater, J. Clean Prod., 2018, 179 42-54. [CrossRef]

- C. Cai, Z.Y. Zhang, J. Liu, N. Shan, H. Zhang, D.D. Dionysiou, Visible light-assisted heterogeneous Fenton with ZnFe2O4 for the degradation of Orange II in water, Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2016, 182 456-468. [CrossRef]

- J.Q. Li, Z.X. Liu, Z.F. Zhu, Magnetically separable ternary hybrid of ZnFe2O4-Fe2O3-Bi2WO6 hollow nanospheres with enhanced visible photocatalytic property, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2014, 320 146-153. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, Y.J. Chen, W. Han, S.M. Liang, Y.Z. Jiao, G.H. Tian, ZIF-8 derived hierarchical ZnO@ZnFe2O4 hollow polyhedrons anchored with CdS for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction, Sep. Purif. Technol., 2023, 309. [CrossRef]

- H. Song, L.P. Zhu, Y.G. Li, Z.R. Lou, M. Xiao, Z.Z. Ye, Preparation of ZnFe2O4 nanostructures and highly efficient visible-light-driven hydrogen generation with the assistance of nanoheterostructures, J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3(16), 8353-8360. [CrossRef]

- C.H. Zhang, X.Y. Han, F. Wang, L.J. Wang, J.S. Liang, A Facile Fabrication of ZnFe2O4/Sepiolite Composite with Excellent Photocatalytic Performance on the Removal of Tetracycline Hydrochloride, Front. Chem., 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- W.H. Fei, Y. Song, N.J. Li, D.Y. Chen, Q.F. Xu, H. Li, J.H. He, J.M. Lu, Hollow In2O3@ZnFe2O4 heterojunctions for highly efficient photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline under visible light, Environ. Sci.-Nano, 2019, 6(10), 3123-3132. [CrossRef]

- B.Y. Yang, S.K. Zhang, Y. Gao, L.Q. Huang, C. Yang, Y.D. Hou, J.S. Zhang, Unique functionalities of carbon shells coating on ZnFe2O4 for enhanced photocatalytic hydroxylation of benzene to phenol, Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2022, 304. [CrossRef]

- Z.F. Yang, X.N. Xia, L.H. Shao, L.L. Wang, Y.T. Liu, Efficient photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline under visible light by Z-scheme Ag3PO4/mixed-valence MIL-88A(Fe) heterojunctions: Mechanism insight, degradation pathways and DFT calculation, Chem. Eng. J., 2021, 410. [CrossRef]

- J. Luo, Y. Wu, X. Chen, T. He, Y. Zeng, G. Wang, Y. Wang, Y. Zhao, Z. Chen, Synergistic adsorption-photocatalytic activity using Z-scheme based magnetic ZnFe2O4/CuWO4 heterojunction for tetracycline removal, J. Alloy. Compd., 2022, 910. [CrossRef]

- D.H. Zhu, L. Cai, Z.Y. Sun, A. Zhang, P. Heroux, H. Kim, W. Yu, Y.A. Liu, Efficient degradation of tetracycline by RGO@black titanium dioxide nanofluid via enhanced catalysis and photothermal conversion, Sci. Total Environ., 2021, 787. [CrossRef]

- T. Cai, W.G. Zeng, Y.T. Liu, L.L. Wang, W.Y. Dong, H. Chen, X.N. Xia, A promising inorganic-organic Z-scheme photocatalyst Ag3PO4/PDI supermolecule with enhanced photoactivity and photostability for environmental remediation, Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 2020, 263. [CrossRef]

- L.J. Zhang, S. Li, B.K. Liu, D.J. Wang, T.F. Xie, Highly Efficient CdS/WO3 Photocatalysts: Z-Scheme Photocatalytic Mechanism for Their Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Evolution under Visible Light, ACS Catal., 2014, 4(10), 3724-3729. [CrossRef]

- Q.L. Xu, L.Y. Zhang, J.G. Yu, S. Wageh, A.A. Al-Ghamdi, M. Jaroniec, Direct Z-scheme photocatalysts: Principles, synthesis, and applications, Mater. Today, 2018, 21(10), 1042-1063. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).