Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Bacterial Cultures

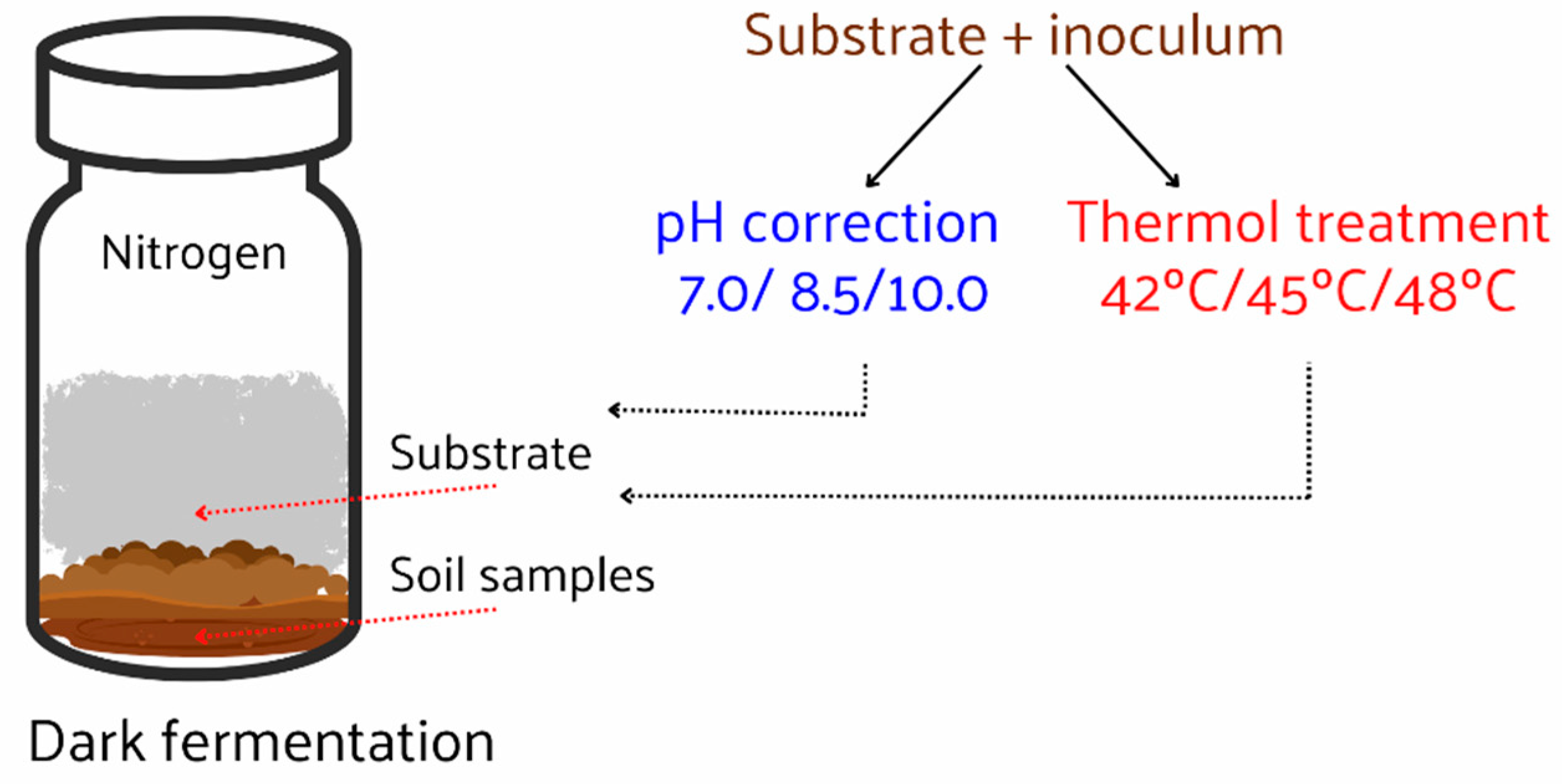

2.2. Hydrogen Fermentation Experimentation

2.3. Experimental Conditions: Temperature Acclimation and pH Optimization

2.4. Substrate and inoculum preparation

2.5. Assessment of hydrogen production during anaerobic digestion process

2.6. Genetic Analysis of Highly Salt-Tolerant Hydrogen-Producing Bacteria using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

2.6.1. PCR-DGGE and Sequencing

2.6.2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

3. Results

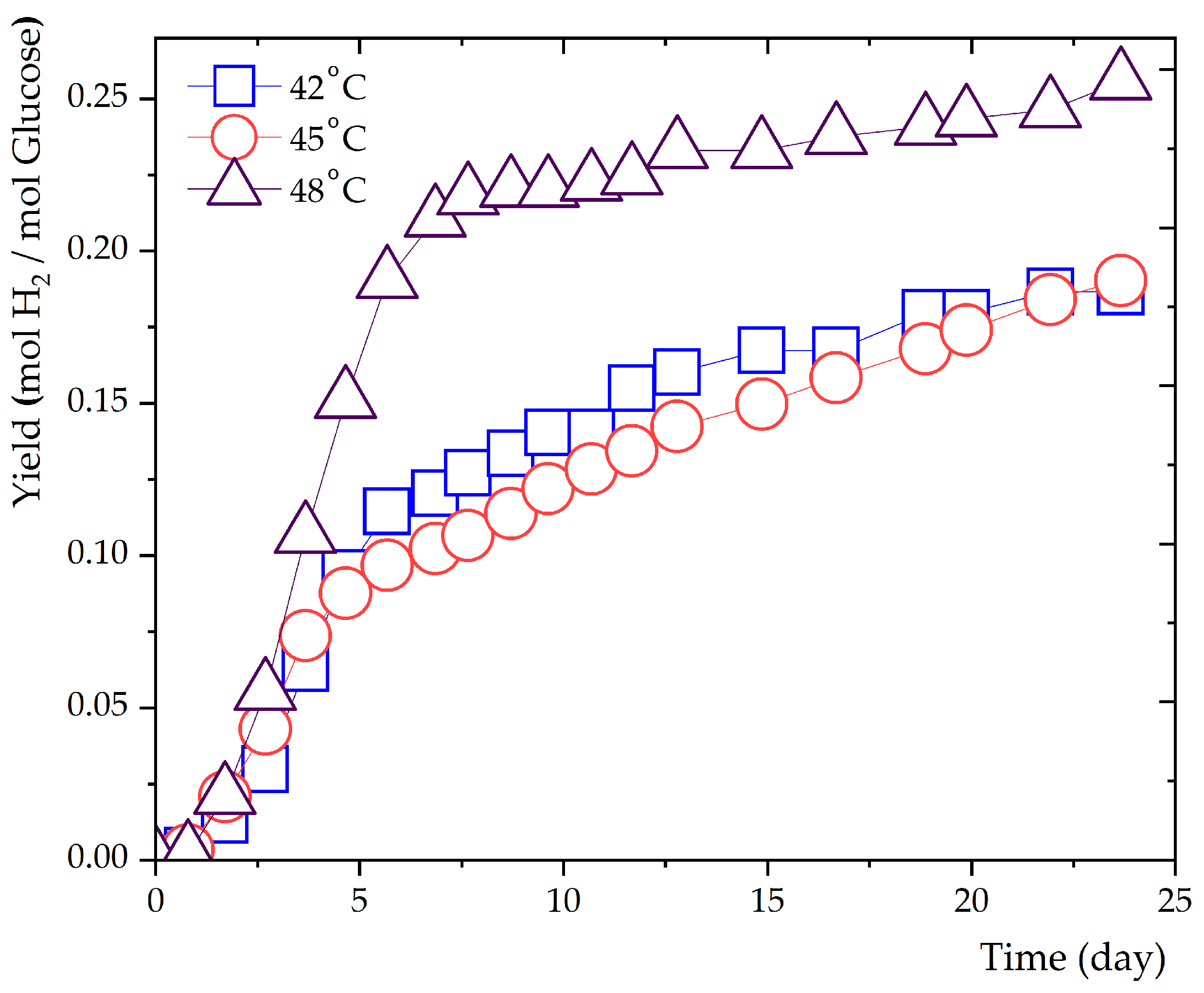

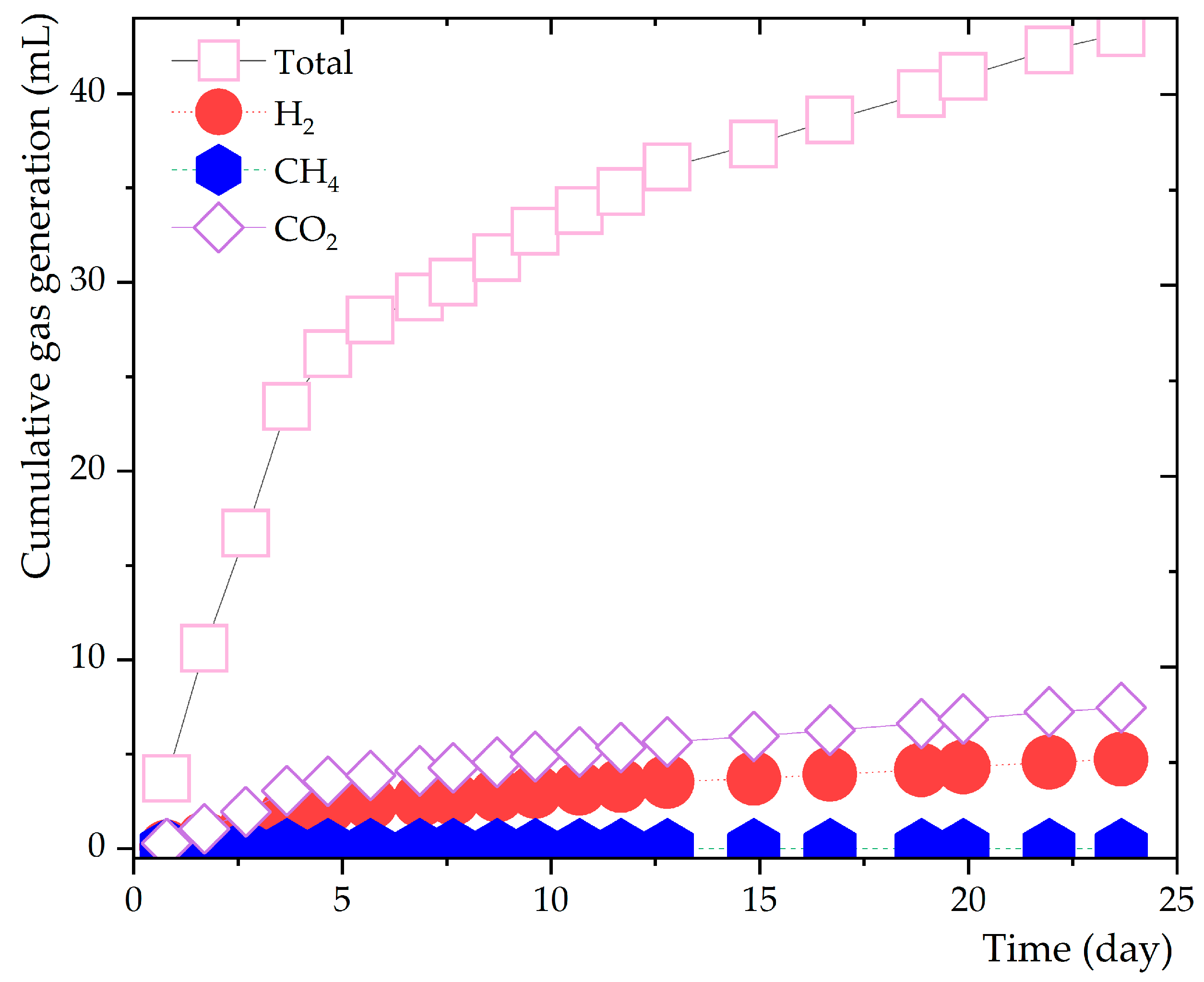

3.1. Thermal Responsiveness of Hydrogen Production

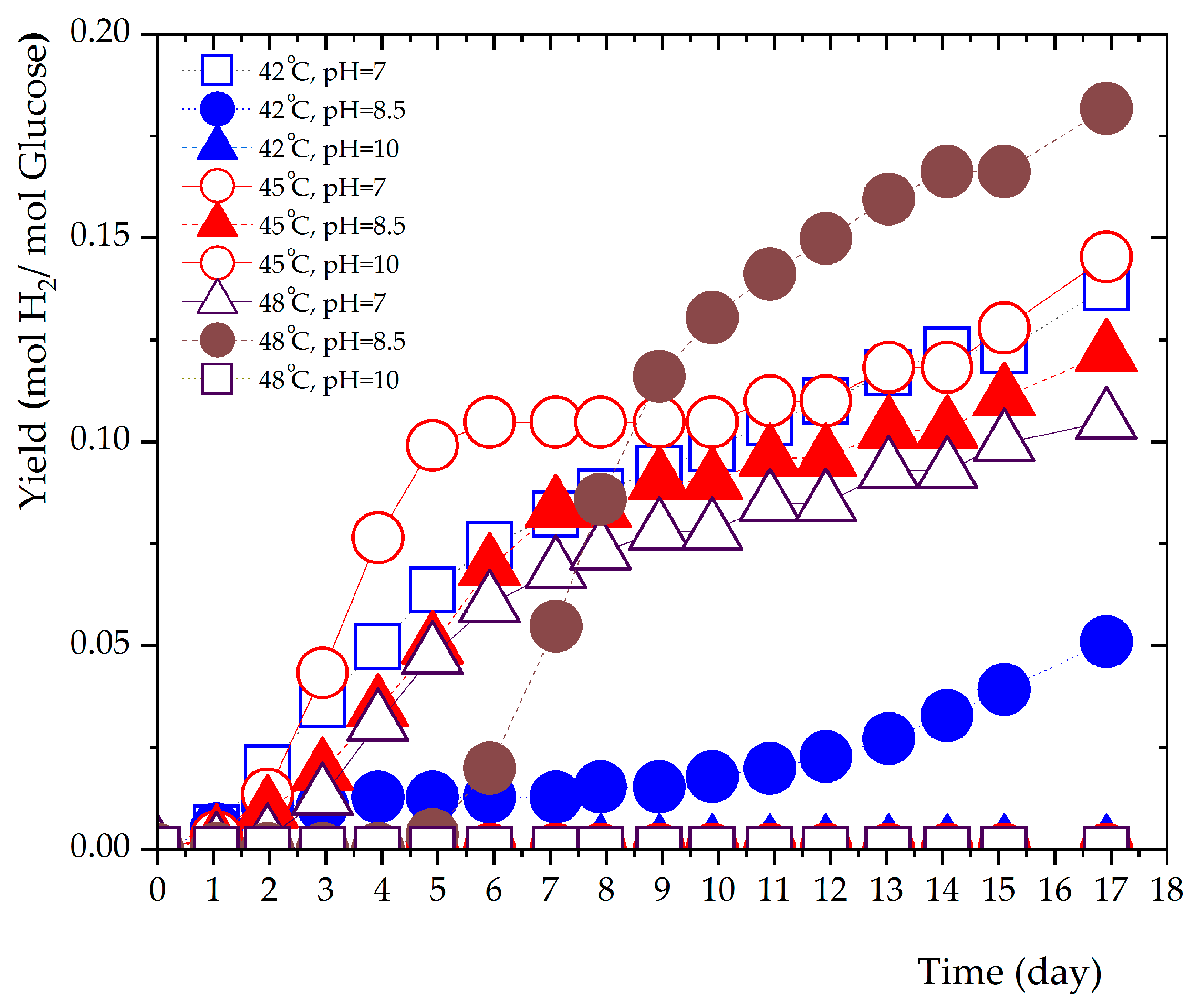

3.2. Influence of pH Conditions on Hydrogen Production.

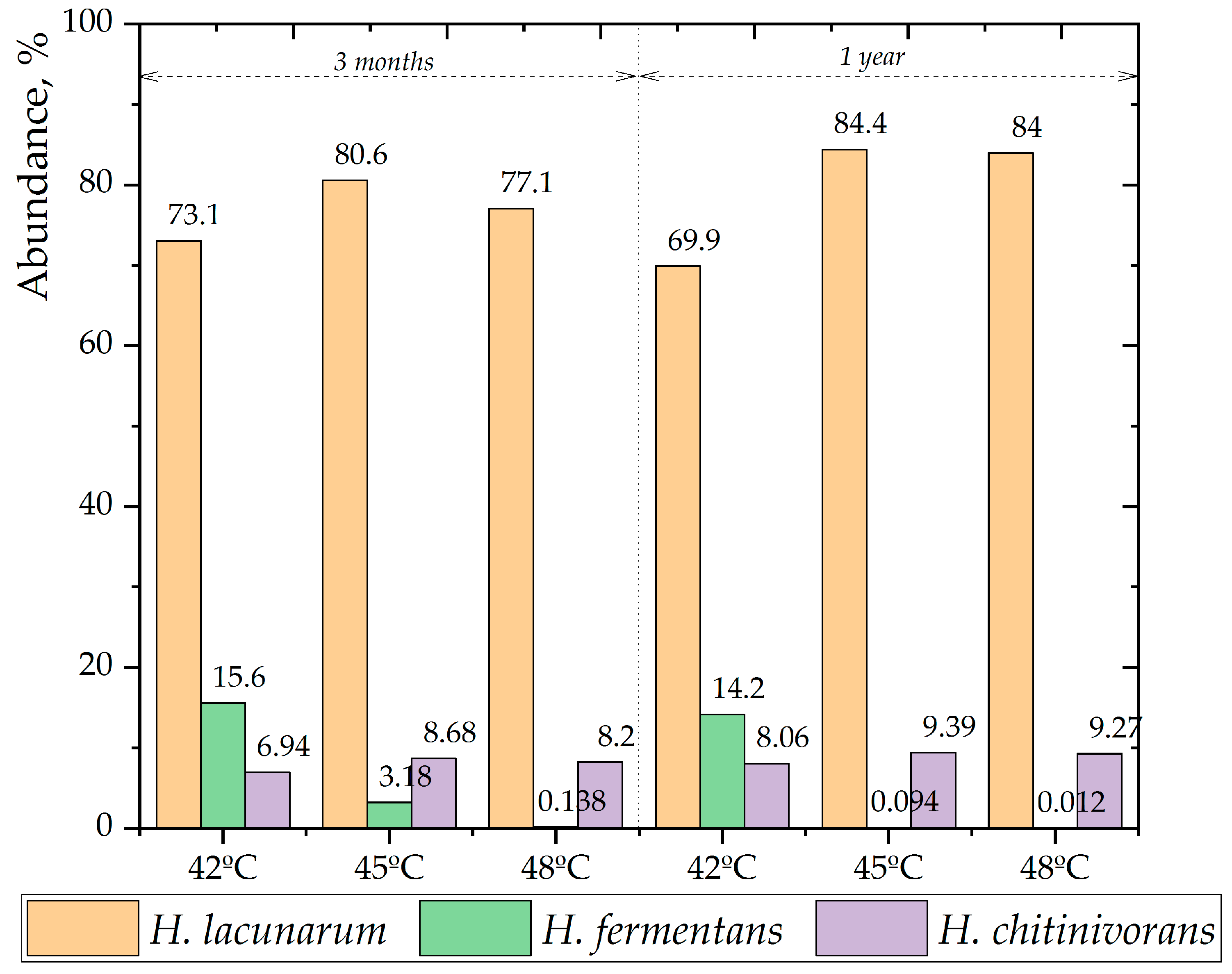

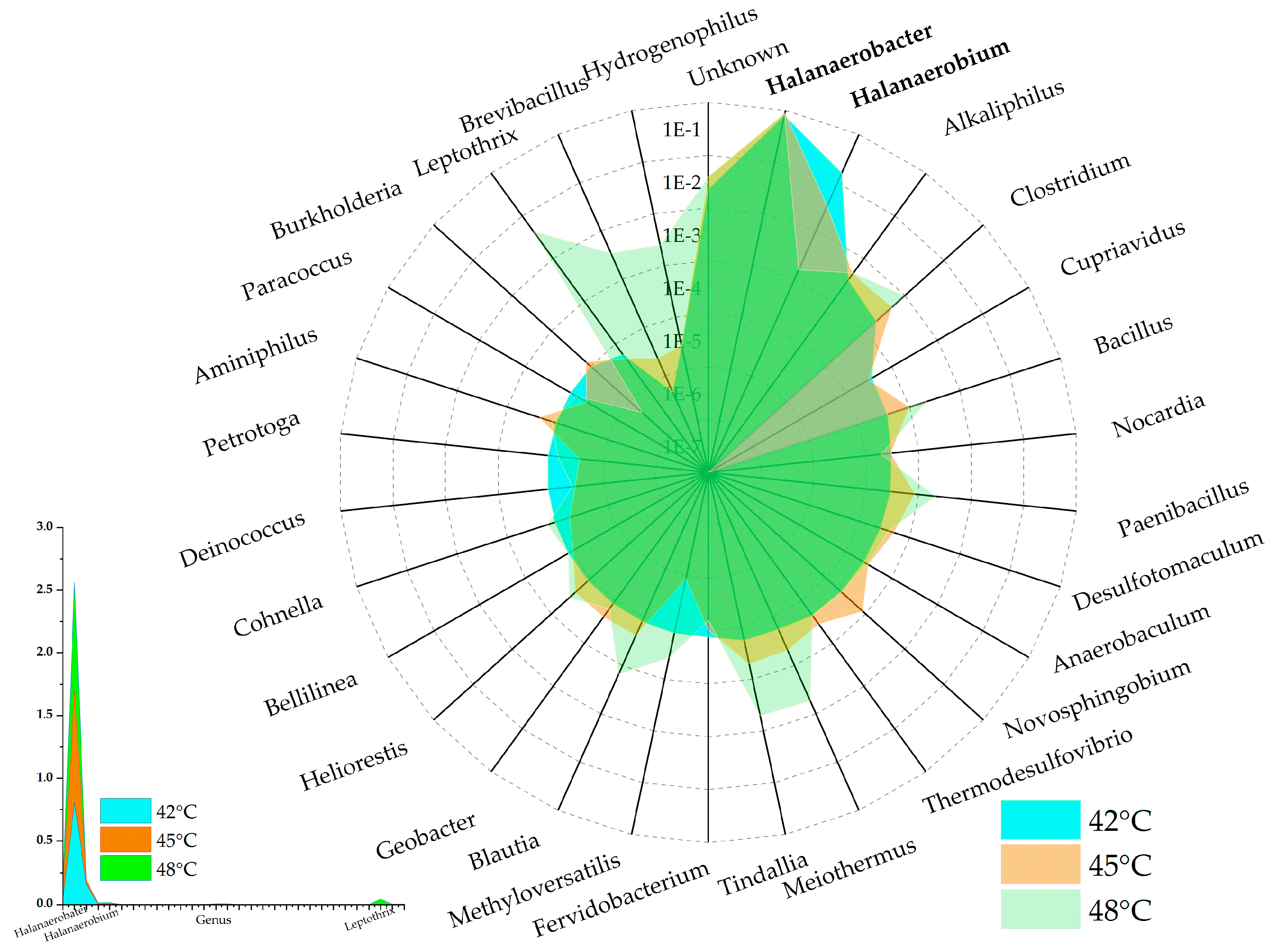

3.3. PCR-DGGE and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Analysis

3.4. Functional Characterization of Halophilic Bacteria in High-Salt Soil Anaerobic Digestion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Owusu, P.A.; Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. A Review of Renewable Energy Sources, Sustainability Issues and Climate Change Mitigation. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.G.; Nguyen-Thi, T.X.; Phong Nguyen, P.Q.; Tran, V.D.; Ağbulut, Ü.; Nguyen, L.H.; Balasubramanian, D.; Tarelko, W.; A. Bandh, S.; Khoa Pham, N.D. Recent Advances in Hydrogen Production from Biomass Waste with a Focus on Pyrolysis and Gasification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorato-Salazar, J.A.; Sadhukhan, J. Annual Biomass Variation of Agriculture Crops and Forestry Residues, and Seasonality of Crop Residues for Energy Production in Mexico. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 119, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, T.; Chopra, M.; Sharma, I. Bioenergy: Biomass Sources, Production, and Applications. Green Approach to Altern. Fuel a Sustain. Futur. 2023, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J.A.; Epelle, E.I.; Tabat, M.E.; Orivri, U.; Amenaghawon, A.N.; Okoye, P.U.; Gunes, B. Waste Biomass Valorization for the Production of Biofuels and Value-Added Products: A Comprehensive Review of Thermochemical, Biological and Integrated Processes. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 159, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velvizhi, G.; Jacqueline, P.J.; Shetti, N.P.; K, L.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Emerging Trends and Advances in Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Biofuels. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 345, 118527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, C.; Dincer, I. Review and Evaluation of Hydrogen Production Options for Better Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodabadi, A.; Mahmoudi, A.; Ghasemi, H. The Potential of Hydrogen Hydrate as a Future Hydrogen Storage Medium. iScience 2021, 24, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2019.

- Osman, A.I.; Mehta, N.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Hefny, M.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Rooney, D.W. Hydrogen Production, Storage, Utilisation and Environmental Impacts: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen Energy, Economy and Storage: Review and Recommendation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, A.M.; Lewis, J.D.; Afzal, M.T. Potential of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) for Bioenergy Production in Canada: Status, Challenges and Outlook. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshemese, Z.; Deenadayalu, N.; Linganiso, L.Z.; Chetty, M. An Overview of Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion and the Possibility of Using Sugarcane Wastewater and Municipal Solid Waste in a South African Context. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegoda, J.N.; Li, B.; Patel, K.; Wang, L.B. A Review of the Processes, Parameters, and Optimization of Anaerobic Digestion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, I.; Bremges, A.; Stolze, Y.; Hahnke, S.; Cibis, K.G.; Koeck, D.E.; Kim, Y.S.; Kreubel, J.; Hassa, J.; Wibberg, D.; et al. Genomics and Prevalence of Bacterial and Archaeal Isolates from Biogas-Producing Microbiomes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R. ze; Fang, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.; Shao, Q.; Fang, F.; Feng, Q.; Cao, J.; Luo, J. Distribution Patterns of Functional Microbial Community in Anaerobic Digesters under Different Operational Circumstances: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bari, H.; Lahboubi, N.; Habchi, S.; Rachidi, S.; Bayssi, O.; Nabil, N.; Mortezaei, Y.; Villa, R. Biohydrogen Production from Fermentation of Organic Waste, Storage and Applications. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachapur, V.L.; Kutty, P.; Pachapur, P.; Brar, S.K.; Le Bihan, Y.; Galvez-Cloutier, R.; Buelna, G. Seed Pretreatment for Increased Hydrogen Production Using Mixed-Culture Systems with Advantages over Pure-Culture Systems. Energies 2019, 12, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, W. Effect of Temperature on Fermentative Hydrogen Production by Mixed Cultures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 5392–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, L.; Sarangi, P.K.; Singh, A.K.; Prakash, A.; Shadangi, K.P. Lignocellulosic Waste Biomass for Biohydrogen Production: Future Challenges and Bio-Economic Perspectives. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 2022, 16, 838–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, D.T.; Ogunbiyi, O.D.; Akamo, D.O.; Otun, K.O.; Akinpelu, D.A.; Adegoke, J.A.; Fapojuwo, D.P.; Oladoye, P.O. Factors Affecting Biohydrogen Production: Overview and Perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27513–27539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.R.; Garcia, J.L.; Patel, B.K.; Cayol, J.L.; Baresi, L.; Mah, R.A. Haloanaerobium Alcaliphilum Sp. Nov., an Anaerobic Moderate Halophile from the Sediments of Great Salt Lake, Utah. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1995, 45, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.C. Biohydrogen. Adv. Renew. Energy Syst. 2014, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Zeng, H.; Gao, Y.; Mo, T.; Li, Y. Bio-Hydrogen Production by Dark Anaerobic Fermentation of Organic Wastewater. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubitz, W.; Ogata, H. Hydrogenases, Structure and Function. Encycl. Biol. Chem. Second Ed. 2013, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu J, R.; Usman T M, M.; S, K.; Kannah R, Y.; K N, Y.; P, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Kumar, G. A Critical Review on Limitations and Enhancement Strategies Associated with Biohydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 16565–16590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lourdes Moreno, M.; Pérez, D.; García, M.T.; Mellado, E. Halophilic Bacteria as a Source of Novel Hydrolytic Enzymes. Life 2013, 3, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokashe, N.; Chaudhari, B.; Patil, U. Operative Utility of Salt-Stable Proteases of Halophilic and Halotolerant Bacteria in the Biotechnology Sector. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taroepratjeka, D.A.H.; Imai, T.; Chairattanamanokorn, P.; Reungsang, A. Extremely Halophilic Biohydrogen Producing Microbial Communities from High-Salinity Soil and Salt Evaporation Pond. Fuels 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karray, F.; Ben Abdallah, M.; Kallel, N.; Hamza, M.; Fakhfakh, M.; Sayadi, S. Extracellular Hydrolytic Enzymes Produced by Halophilic Bacteria and Archaea Isolated from Hypersaline Lake. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohban, R.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Ventosa, A. Screening and Isolation of Halophilic Bacteria Producing Extracellular Hydrolyses from Howz Soltan Lake, Iran. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayol, J.L.; Ollivier, B.; Patel, B.K.C.; Prensier, G.; Guezennec, J.; Garcia, J.L. Isolation and Characterization of Halothemothrix Orenii Gen. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994, 44, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudiartha, G.A.; Imai, T.; Mamimin, C.; Reungsang, A. Effects of Temperature Shifts on Microbial Communities and Biogas Production: An In-Depth Comparison. Fermentation 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taroepratjeka, D.A.H.; Imai, T.; Chairattanamanokorn, P.; Reungsang, A. Investigation of Hydrogen-Producing Ability of Extremely Halotolerant Bacteria from a Salt Pan and Salt-Damaged Soil in Thailand. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Imai, T.; Ukita, M.; Sekine, M.; Higuchi, T. Triggering Forces for Anaerobic Granulation in UASB Reactors. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudiartha, G.A.W.; Imai, T. An Investigation of Temperature Downshift Influences on Anaerobic Digestion in the Treatment of Municipal Wastewater Sludge. J. Water Environ. Technol. 2022, 20, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.J.; Zheng, Y.M.; Yu, H.Q. Influence of NaCl on Hydrogen Production from Glucose by Anaerobic Cultures. Environ. Technol. 2005, 26, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierra, M.; Trably, E.; Godon, J.-J.; Bernet, N. Fermentative Hydrogen Production under Moderate Halophilic Conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 7508–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Achen, W.; Wenjie, W.; Xuesong, L.; Liuxia, Z.; Guangwen, H.; Daqing, H.; Wenli, C.; Qiaoyun, H. High Salinity Inhibits Soil Bacterial Community Mediating Nitrogen Cycling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e01366–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, G. Hydrogen Production of a Salt Tolerant Strain Bacillus Sp. B2 from Marine Intertidal Sludge. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivistö, A.; Santala, V.; Karp, M. Hydrogen Production from Glycerol Using Halophilic Fermentative Bacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8671–8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerholm, M.; Isaksson, S.; Karlsson Lindsjö, O.; Schnürer, A. Microbial Community Adaptability to Altered Temperature Conditions Determines the Potential for Process Optimisation in Biogas Production. Appl. Energy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, U.; Tandukar, M.; Hajaya, M.G.; Pavlostathis, S.G. Transition of Municipal Sludge Anaerobic Digestion from Mesophilic to Thermophilic and Long-Term Performance Evaluation. Bioresour. Technol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanthi Kiran, K.; Chandra, T.S. Production of Surfactant and Detergent-Stable, Halophilic, and Alkalitolerant Alpha-Amylase by a Moderately Halophilic Bacillus Sp. Strain TSCVKK. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 77, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshabaki Isfahani, F.; Tahmourespour, A.; Hoodaji, M.; Ataabadi, M.; Mohammadi, A. Characterizing the New Bacterial Isolates of High Yielding Exopolysaccharides under Hypersaline Conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.W.; Park, T.; Tong, Y.W.; Yu, Z. Chapter One - The Microbiome Driving Anaerobic Digestion and Microbial Analysis. In; Li, Y., Khanal, S.K.B.T.-A. in B., Eds.; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 5, pp. 1–61 ISBN 2468-0125.

- O-Thong, S.; Mamimin, C.; Kongjan, P.; Reungsang, A. Chapter Six - Two-Stage Fermentation Process for Bioenergy and Biochemicals Production from Industrial and Agricultural Wastewater. In; Li, Y., Khanal, S.K.B.T.-A. in B., Eds.; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 5, pp. 249–308 ISBN 2468-0125.

- Hung, K.-S.; Liu, S.-M.; Tzou, W.-S.; Lin, F.-P.; Pan, C.-L.; Fang, T.-Y.; Sun, K.-H.; Tang, S.-J. Characterization of a Novel GH10 Thermostable, Halophilic Xylanase from the Marine Bacterium Thermoanaerobacterium Saccharolyticum NTOU1. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, A.; Bansal, N.; Kumar, S.; Bischoff, K.M.; Sani, R.K. Improved Lignocellulose Conversion to Biofuels with Thermophilic Bacteria and Thermostable Enzymes. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 128, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-H.; Whang, L.-M. Resource Recovery from Lignocellulosic Wastes via Biological Technologies: Advancements and Prospects. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Ribose-5-Phosphate Isomerases: Characteristics, Structural Features, and Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6429–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.A.; Rawat, D.; Ahi, J.D.; Koiri, R.K. Ameliorative Effect of Piracetam on Emamectin Benzoate Induced Perturbations in the Activity of Lactate Dehydrogenase in Murine System. Adv. Redox Res. 2021, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeßen, C.; Wolf, N.; Cramer, B.; Humpf, H.-U.; Steinbüchel, A. In Vitro Biosynthesis of 3-Mercaptolactate by Lactate Dehydrogenases. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2018, 108, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Xing, X. Disruption of Lactate Dehydrogenase and Alcohol Dehydrogenase for Increased Hydrogen Production and Its Effect on Metabolic Flux in Enterobacter Aerogenes. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 194, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

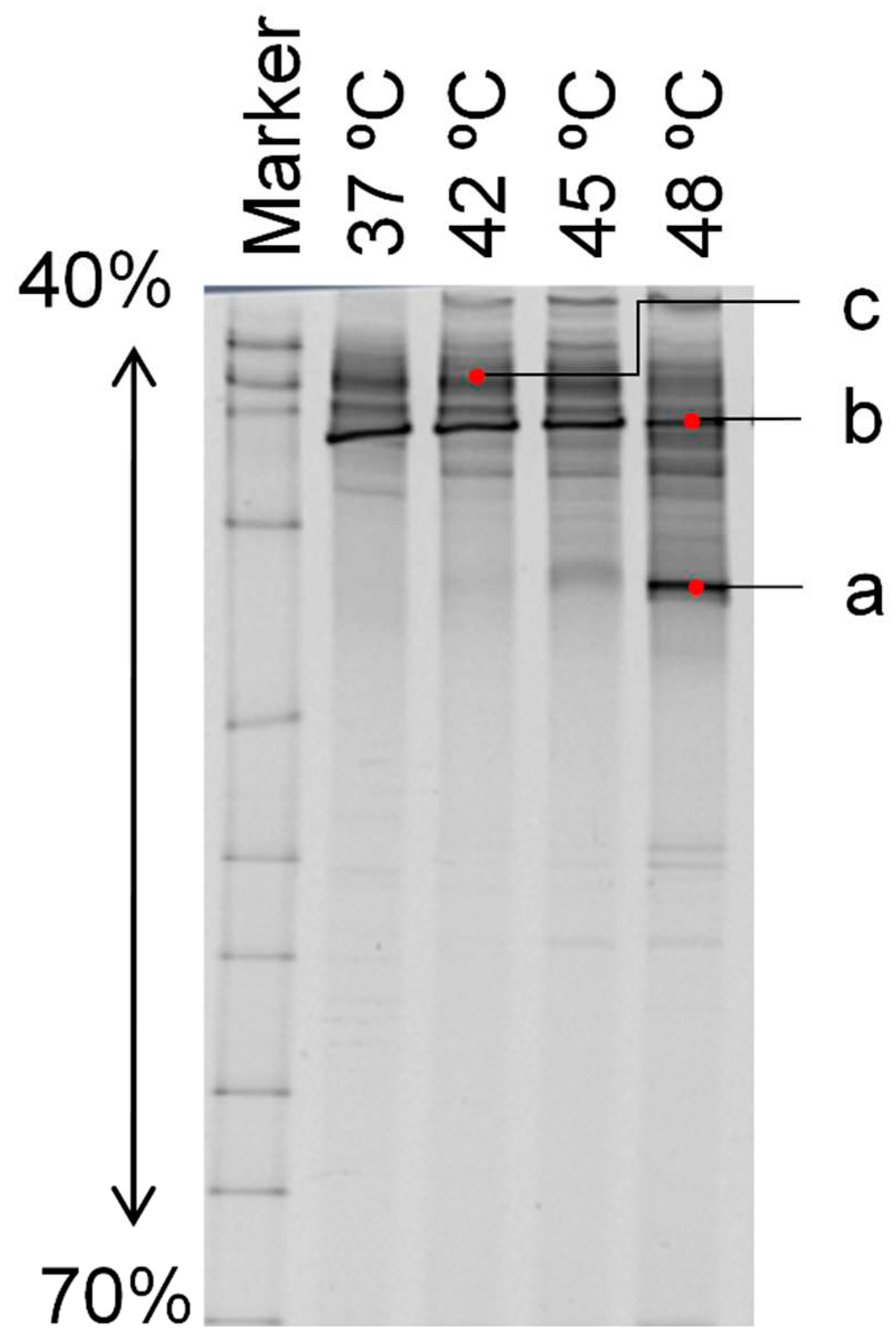

| Band | Related species | Homologous |

|---|---|---|

| a | Halanaerobacter lacunarum | 100% |

| b | Halanaerobiumfermentans | 100% |

| c | Halanaerobium saccharolyticum subsp. Senegalense | 94.29% |

| AD Phase | Enzymes (EC) | Reaction | Relative abundance (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 °C | 45 °C | 48 °C | |||

| Hydrolysis | Xylan 1,4-beta-xylosidase(EC: 3.2.1.37) | D-Xylose + 1,4-beta-D-Xylan <=> 1,4-beta-D-Xylan + H2O | 16.43 | 4.66 | 2.44 |

| D-ribose-5-phosphate aldose-ketose isomerase (EC: 5.3.1.6) | D-Ribose 5-phosphate <=> D-Ribulose 5-phosphate | 16.30 | 4.50 | 6.91 | |

| Acidogenesis | L-lactate dehydrogenase (EC: 1.1.1.27) | (S)-Lactate + NAD+ <=> Pyruvate + NADH + H+ | 16.21 | 4.33 | 2.47 |

| Methanogenesis | CoB-CoM Ferredoxin: H2 reductase (EC: 1.8.98.5) | Coenzyme M 7-mercaptoheptanoylthreonine-phosphate heterodisulfide + Dihydromethanophenazine <=> Coenzyme B + Coenzyme M + Methanophenazine | 0.328 | 0.709 | 1.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).