1. Introduction

Maxillofacial fractures are a common occurrence in trauma patients, and the use of miniplates for fixation has become a popular method since their introduction in the late 1970s [

1]. Miniplates offer advantages such as low-profile design, better visualization, stability, and strength, allowing for early mobilization and faster recovery, they have also demonstrated high levels of biocompatibility and a low rate of hardware-related complications [

2]. Miniplates are commonly used for mandibular, zygomatic, and maxillary fractures, as well as fractures of the nasal bones, orbit, and frontal bone [

2]. Another advantage of miniplates is that they provide stability and strength to the fracture site. The use of miniplates also allows for easier removal of the fixation device, reducing the risk of complications and the need for additional surgeries. While miniplates have proven effective, their limitations should be considered. Complex fractures or patients with poor bone quality may require alternative fixation methods [

3]. Metal sensitivity or allergies must also be considered before choosing miniplates [

4,

5]. The decision to remove or retain miniplates after jaw surgery is a topic of ongoing debate. Complications such as infection, plate loosening, and plate exposure are common reasons for removal [

5,

6]. Infections can be serious and may require removal to prevent further complications [

7,

8]. Loosening and plate exposure can compromise stability and cause discomfort or pain. However, removal itself carries risks, including pain, increased infection risk, and reduced stability [

5]. Few studies have reported additional issues related to miniplates, such as the formation of foreign body granulomas or entrapment of facial nerve branches [

9,

10].

Small steel plates and screws are frequently utilized for the purpose of providing stability and support to fractured bones. Nevertheless, their presence in the body can result in various outcomes, both positive and negative. On the positive side, these miniplates play a crucial role in preserving bone alignment, facilitating the healing process, and restoring normal function. They effectively counteract the forces exerted on the fractured bone, allowing patients to regain mobility more quickly than traditional methods like casts or immobilization. A significant consideration in the field of orthopedics revolves around whether to remove these miniplates once the bone has fully healed. While the removal of miniplates may initially appear advantageous by eliminating potential discomfort, reducing the risk of infection, and preventing stress-induced weakening of the bone, it presents its own set of complexities. Surgical removal of miniplates carries inherent risks, including complications related to anesthesia, infection, and the potential for damage to surrounding tissues. Moreover, the procedures for miniplates removal contribute additional costs to the healthcare system and may extend patients’ recovery periods. Conversely, the non-removal approach entails leaving the small steel plates and screws in place after the bone has healed. This approach has gained popularity due to its perceived benefits, such as avoiding the risks associated with removal surgeries and alleviating the financial burden on both patients and healthcare systems. Nonetheless, the continued presence of these miniplates can potentially give rise to complications. Some studies have underscored the risk of stress shielding, in which the presence of miniplates may lead to a reduction in bone density around the miniplates site. This phenomenon can impact the overall structural integrity of the bone and potentially lead to long-term issues.

To guide decisions regarding removal, it is crucial to assess the rationale and factors influencing the decision. This study aims to conduct a meta-analysis of relevant studies to determine the rationale for maxillofacial fracture plate removal and explore the factors influencing the decision to remove or retain these miniplates. Long-term follow-up is essential to evaluate the fate of these miniplates and inform clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

This study represents a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. We formulated the research protocol following the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) and registered it under PROSPERO registration number CRD42023399232.

2.1. Search strategy

Following the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA statement, we conducted a systematic review of the available literature. We searched various databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and Scopus, to identify potentially eligible studies. The search used specific keywords such as "maxillofacial fractures," "titanium miniplates," "screws," "complications," "removal," and "maxillofacial trauma." We included studies published from 1989 to 2022 in our meta-analysis. The selected studies for analysis were those that reported on the outcomes of using miniplates in maxillofacial surgery, including details on complications and removal rates. We also employed additional sources, including websites and citation searching, to identify relevant studies.

2.2. Selection of studies

The search strategy resulted in 259 studies, and after removing duplicates and filtering. Secondly, the abstracts of the remaining 111 studies were scanned by two reviewers to remove studies irrelevant to this review. 57 articles were sought for retrieval, of which only 44 were retrieved for full-text reading. Articles that did not satisfy a predetermined eligibility criterion were excluded, and so finally 11 articles were found eligible to be included in this review [Figure 1].

We reviewed all research papers centered on the removal of miniplates in patients undergoing trauma and maxillofacial surgery. Information gathered from each study encompassed details such as the study’s participant demographics, research methodology, sample size, age distribution, gender distribution, the quantity of miniplates both inserted and removed, the location of miniplate placement and removal, the specific type of miniplates employed, the rationale behind removal, and the duration between miniplate insertion and subsequent removal.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria:

To be considered for inclusion in this study, articles had to meet specific eligibility criteria, as outlined by both inclusion and PICOS criteria:

Inclusion Criteria:

1 Language Requirement: Articles had to be in English.

2 Full-Text Availability: The full text of the article needed to be accessible.

3 Patient Population: The study had to involve patients with fractured jaws who were treated using miniplate fixation and had a minimum follow-up duration of 12 months.

4 Intervention and Comparison: The study should investigate rigid internal fixation with miniplates, with or without plate removal.

5 Outcome Measure: The primary outcome of interest was the percentage of miniplates that were removed.

6 Study Design: Eligible studies included clinical trials, controlled trials, retrospective studies, and case series.

Exclusion Criteria:

1 Language Exclusion: Articles published in languages other than English were excluded.

2 Non-Human Studies: Studies conducted on animals or in vitro were not considered.

3 Duplicate Publications: Duplicate articles, which could introduce bias, were excluded.

4 Insufficient Information: Articles lacking complete and detailed information about miniplate sites and numbers were excluded.

5 Publication Types: Editorial letters, case reports, and review articles were excluded.

6 Short Follow-Up: Studies with a follow-up duration of less than 12 months were also excluded.

The screening process involved a review of article titles and abstracts, followed by a thorough examination of the full-text publications of potentially relevant studies. Two independent reviewers (NA and NI) conducted this eligibility assessment in a standardized, non-blinded manner. The agreement level between the reviewers was assessed using the kappa statistic for all screening steps. Kappa values falling between 0.40 and 0.59 indicated fair agreement, values between 0.60 and 0.74 indicated good agreement, and values of 0.75 or higher indicated excellent agreement. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through consensus, and if necessary, a third reviewer (MJ) was consulted.

2.4. Data Extraction Process:

Two separate assessors, identified as NA and NI, collected the following data from articles meeting the inclusion criteria: author names, publication year, study design, the number of patients and plates inserted, average patient age, gender ratio, the location of miniplate placement (mandible or maxilla), reasons for miniplate removal, and the average follow-up duration in months. To assess the level of agreement between these assessors, the kappa statistic, applying the same criteria used during the study selection phase, was utilized. In cases of discrepancies, the assessors resolved them through discussion. If a consensus could not be reached, a third evaluator (MJ) was consulted to provide an assessment.

2.5. Study characteristics (Quality assessment)

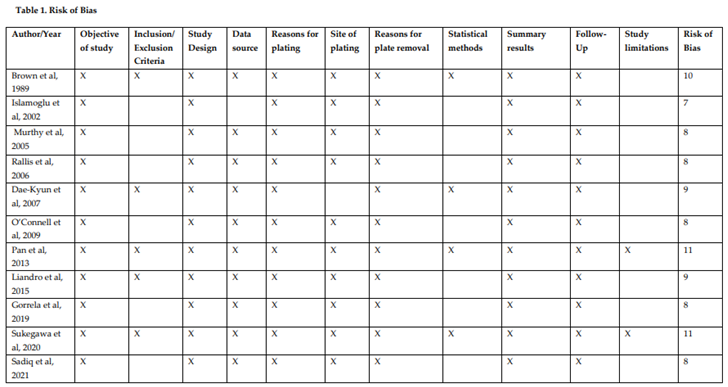

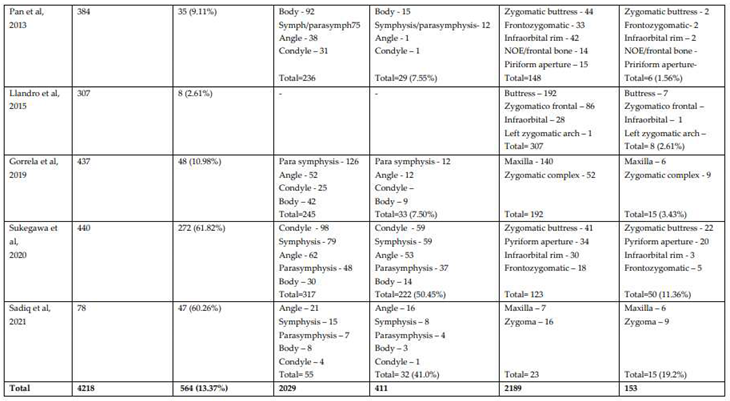

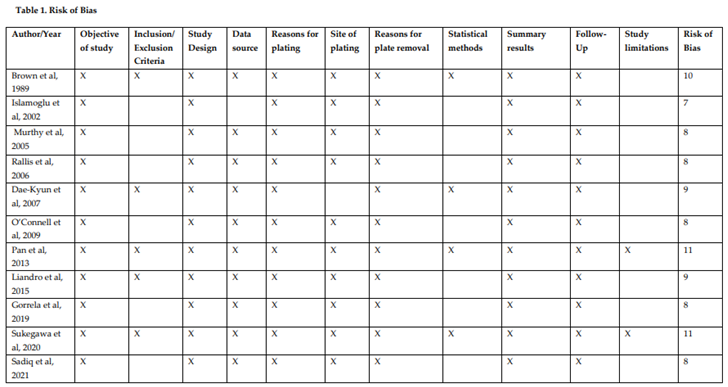

The review incorporated 11 articles that met our inclusion criteria. These articles were published within the time frame of 1989 to 2022. Among these selected articles, 5 had a low risk of bias, while 6 exhibited a moderate risk of bias. Notably, none of the articles were deemed to have a high risk of bias, as summarized in Table 1.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The data underwent analysis using the CMA-V4 software, employing the random-effects model for estimating the combined prevalence and its corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Within this analysis, we evaluated heterogeneity among the studies using Cochran’s Q statistics, the I2 statistic describing the percentage of total variation across included studies due to heterogeneities, and the tau square (T2) test.

To further interpret the meta-analysis results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, removing one study at a time to gauge its impact on the overall outcomes. This approach assessed the resilience of the findings and potential influence of any individual study on the overall effect estimation. The sensitivity analysis confirmed that removing any single study did not significantly alter the overall effect estimate. The results remained consistent, with the effect size falling within the overall estimate range.

Furthermore, we assessed heterogeneity among the incorporated studies using a chi-squared test and the I-squared statistic. The chi-squared test yielded a significant result (p<0.001), signifying substantial heterogeneity among the studies. The I-squared statistic was 86.4%, indicating a considerable degree of heterogeneity.

To explore potential sources of this heterogeneity, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on the indication for plate removal. This analysis demonstrated a reduction in heterogeneity when grouping studies based on the indication for plate removal. The I-squared statistic decreased to 69.2% for infection, 79.1% for tooth extraction, and 43.2% for other reasons.

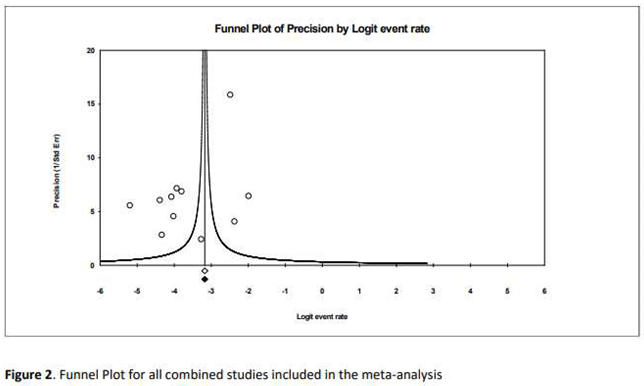

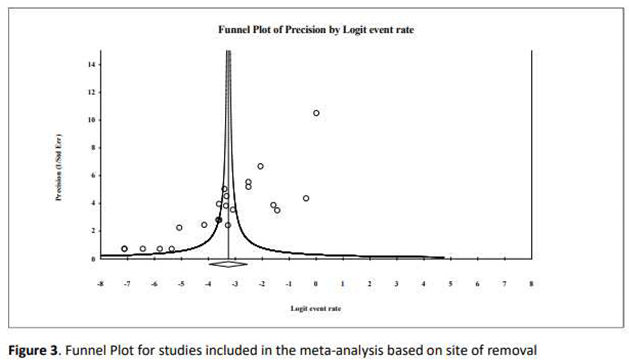

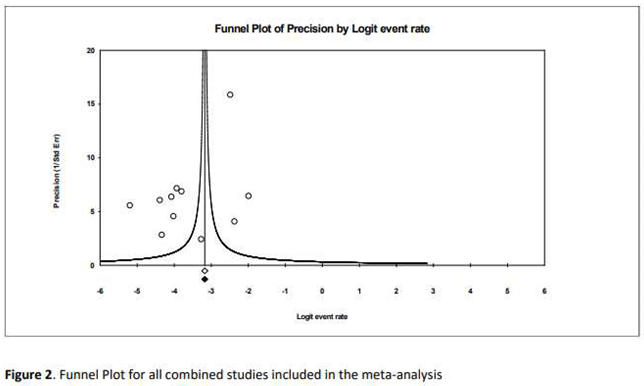

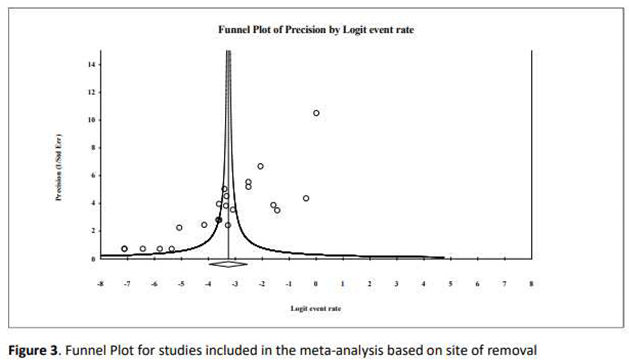

Additionally, we utilized a funnel plot to evaluate potential publication bias in the encompassed studies. The plot displayed a relatively symmetrical distribution of studies, suggesting no significant publication bias [Figure 2] and [Figure 3].

3. Results

A total of 259 articles were identified, of which 248 were excluded, 11 remaining articles satisfied our criteria and were included in our review [Figure 1], 10 of which were retrospectives and 1 prospective. A risk of bias assessment was done following STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (Table 1).

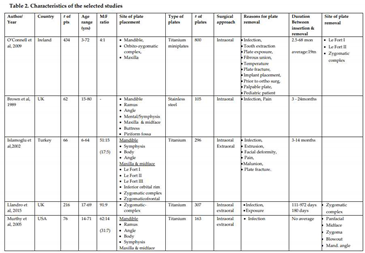

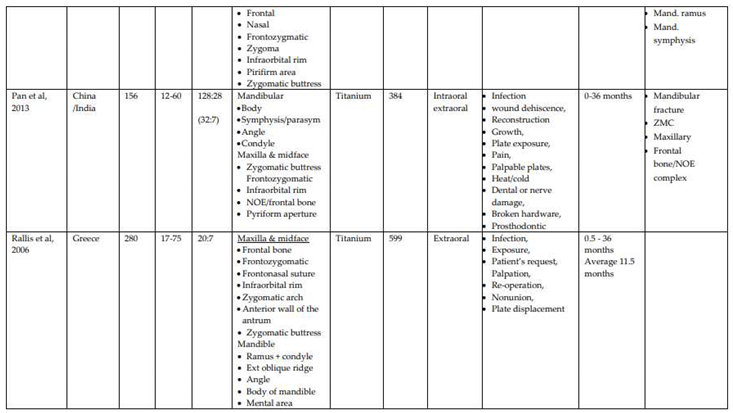

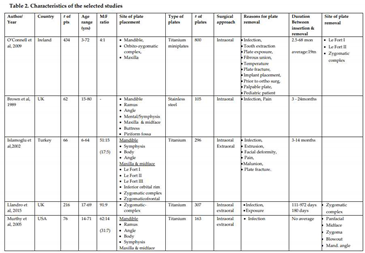

Eleven studies were included in the meta-analysis, and a total of 2,240 patients were assessed. With M:F ratio range from 4:1 [

16] to 86:3 [

19]. The studies were all retrospective in nature, with the largest study including 434 patients [

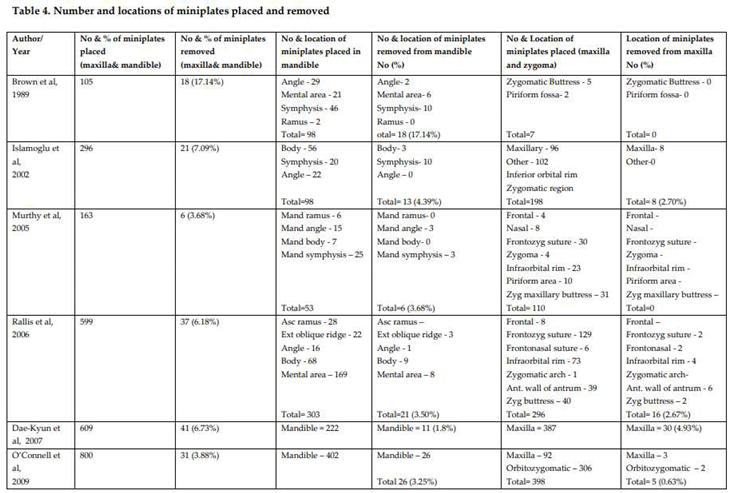

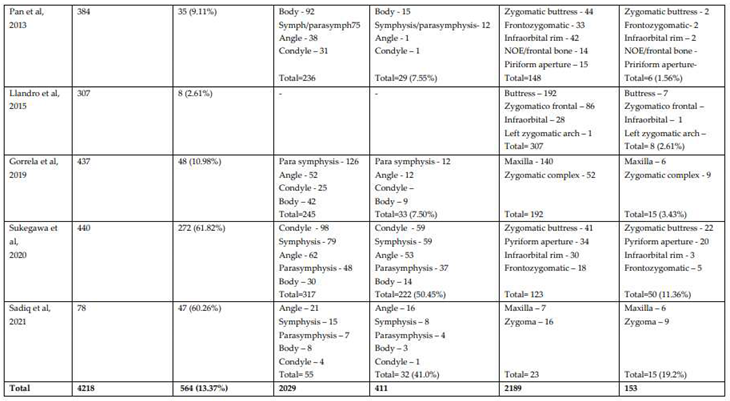

16] (Table 2). Total number of miniplates inserted was 4218, and total number of miniplates removed were 564 (13.3%), the mean time to removal was 10.9 months, with the longest time to removal being 24 years.

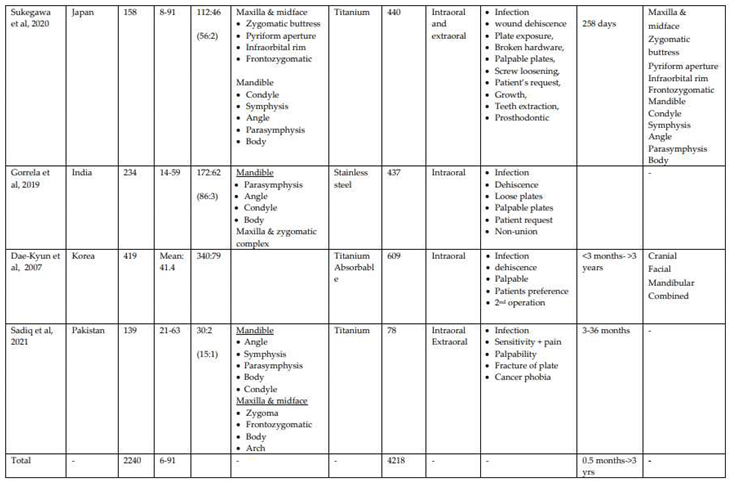

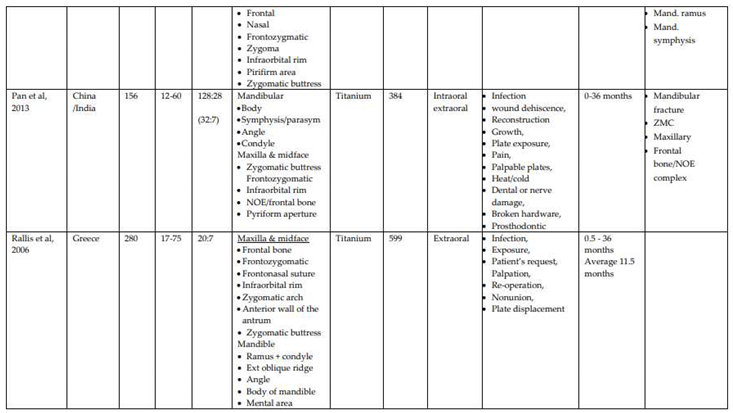

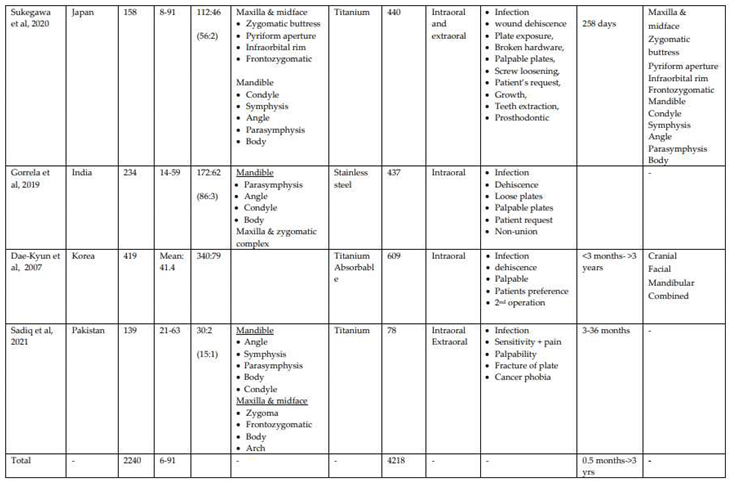

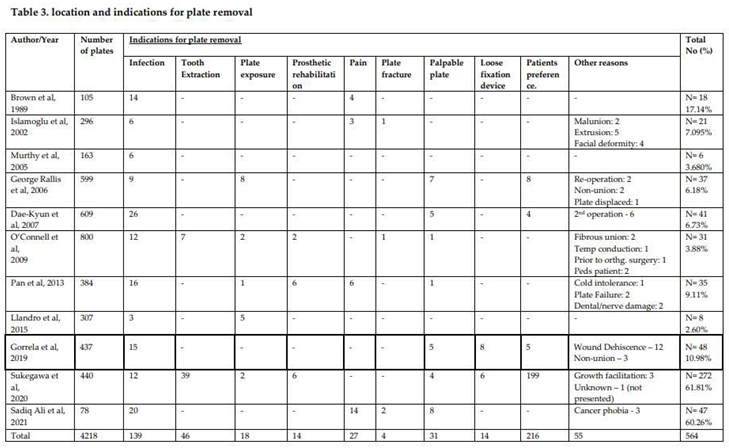

In terms of the reasons for miniplates removal, request by the patient (216 cases, 38.2%), followed by infection was reported in 139 cases (24.6%), and tooth extraction (46 cases, 8.1%). Other indications included palpable plate (31 cases, 5.4%), pain (27 cases, 4.8%), plate exposure (18 cases, 3.1%), and lose plates (14 cases, 2.4%). Other relatively less common reasons that resulted in miniplates removal include, prosthetic rehabilitation, and wound dehiscence, temperature sensitivity, malunion, nonunion, fibrous union, miniplate displacement, and facial deformity (Table 3).

The duration of miniplates removal was reported in a few studies, with some studies reporting a mean duration of 6 months, while others reported up to 10 years. For example, O’Connell et al. [

16] reported a mean duration of 3.3 years, while Sukegawa et al. [

20] reported a mean duration of 10 years.

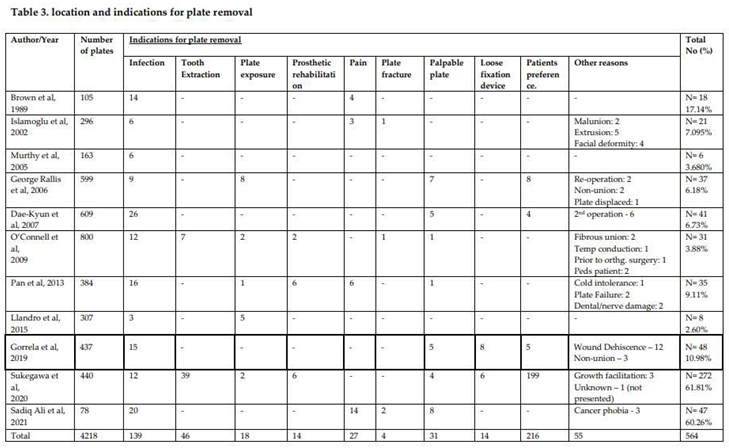

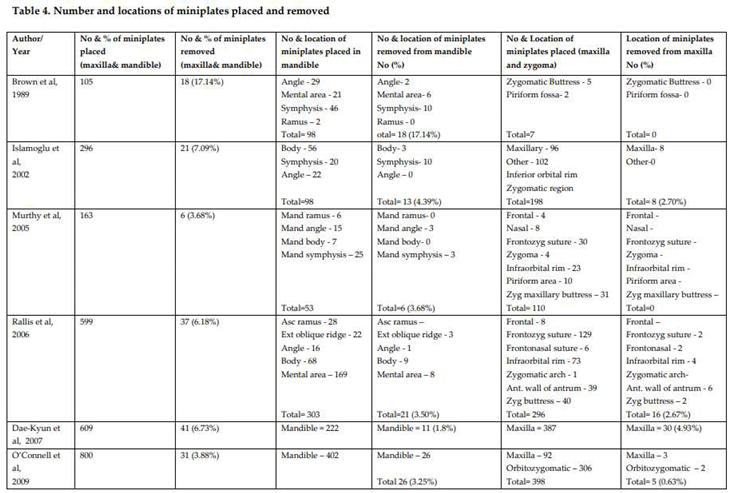

The site of miniplates removal also varied, with some studies reporting a higher incidence of removal in the mandible (411 72.8%), especially symphasis/parasymphasis region 122 (29.7%), angle of mandible 88 (21.4%) compared to the maxilla (153 27.1%) especially zygomatic buttress 31 (20.3%) and piriform fossa 20 (13.0%) (Table 4).

Meta-analysis of studies:

We conducted a meta-analysis based on eleven studies. The effect size index is the event rate. The random-effects model was applied for the analysis. The studies considered in the analysis are viewed as a random sample from a larger pool of potential studies, and this analysis aims to draw inferences for that broader population. The calculated mean effect size is 0.026, falling within a 95% confidence interval of 0.014 to 0.048. This interval represents the range within which the mean effect size in the comparable universe of studies could potentially lie.

The Q-statistic was used to test the null hypothesis that all studies in the analysis share a common effect size. The computed Q-value was 472.749 with 10 degrees of freedom, yielding a p-value less than 0.001. Employing a significance criterion of alpha set at 0.100, we reject the null hypothesis, implying that the true effect size may vary among the studies. The I-squared statistic was found to be 98%, indicating that a significant portion (98%) of the observed effect variance is attributed to true effects rather than sampling error.

Assuming a normal distribution of true effects (in logit units), we estimated the prediction interval to be between 0.002 and 0.247. Within this interval, the true effect size in 95% of all comparable populations is expected to fall.

Analysis Based on Site of Removal

When considering the site of removal, the mean effect size is 0.034, with a 95% confidence interval spanning from 0.019 to 0.060. This range reflects the potential variation in the mean effect size within the universe of comparable studies. The I-squared statistic for this analysis is 97.5%, indicating that a substantial portion (97%) of the observed effect variance is due to true effects rather than sampling error.

4. Discussion

The use of miniplates for the fixation of facial bone fractures has gained popularity due to their effectiveness in achieving stability and facilitating rapid recovery. However, there are instances where the removal of these miniplates becomes necessary post-surgery due to various reasons.

In this study, a total of 2,240 patients were assessed, encompassing a wide range of age groups from pediatric patients to elderly individuals. The majority of studies showed a higher representation of male patients. The studies were conducted in various countries, potentially reflecting differences in healthcare practices and patient demographics. The rationales for plate removal varied across studies, spanning from infections and pain to more specific concerns such as plate exposure, growth issues, and considerations for prosthetic rehabilitation. These discrepancies highlight the intricacies of maxillofacial surgeries and how patient characteristics may influence the decision to remove plates. These differences also underscore the importance of thorough patient assessment and personalized interventions in these surgical procedures.

The decision on whether to keep or remove miniplates utilized in maxillofacial surgery is frequently influenced by several factors, such as the patient’s age, medical history, and the location and nature of the fracture. The presence of infection or exposure of the plate may necessitate removal, while the absence of complications might indicate that retaining the plates is a viable option.

Our research findings indicate that the most common reason for miniplate removal was patient request, followed by tooth extraction and infection at the surgical site. This discovery aligns with prior studies that have identified infection as the primary driver for miniplate removal [

22,

23]. Miniplates, positioned in sensitive submucosal tissues, are susceptible to environmental trauma and the forces generated during chewing, which can compromise their stability, lead to screw loosening, provoke inflammation, and increase the risk of infection. Insufficient suturing techniques and suboptimal cooling of bone during screw hole preparation have also been associated with miniplate failure due to infection. Patients involved in road traffic accidents, in particular, are at a higher risk of contaminated wounds and a heightened likelihood of future miniplate removal [

24].

Infections linked to miniplates typically remain confined within the bone and seldom progress to osteomyelitis or delayed union. When infection arises within the initial 6 weeks after fixation, conservative management involving pus drainage and antibiotic therapy may suffice to facilitate fracture healing while retaining the fixed bone. Once the fracture is stable and healed, miniplate removal may be performed. However, if the infection extends to the underlying operated bone and bony union is incomplete, miniplate removal followed by external fixation and bone grafting might be necessary. Infections can stem from oral cavity bacteria or improper aseptic techniques during surgery. Brown et al. [

11] documented 14 out of 105 miniplates being removed due to infection, while O’Connell et al. [

16] noted 12 out of 800 miniplates being removed for the same reason.

In certain instances, infection can be attributed to tooth damage during the fixation surgery, the presence of teeth within the fracture line during trauma, or compromised blood supply in the edentulous mandible. However, when infection does not affect the bone, miniplates can be preserved through the application of antibiotics, cleaning, removal of infected tissue, and the elimination of infection sources. Small plates can harbor bacteria, which may lead to sustained inflammation and discomfort. Research indicates that the occurrence of infection in patients with retained small plates can reach up to 30% [

25]. The probability of infection increases over time, implying that the longer a small plate remains within the body, the greater the likelihood of infection.

In our study, 4.8% of miniplate removals were attributed to pain. Other reasons for removal encompassed patient requests, growth limitations in pediatric cases, prosthetic rehabilitation requirements, deformities stemming from malunion or non-union, tooth extraction, wound reopening, palpability, nerve impairment, and cold intolerance. Mosbah et al. [

26] reported a 14% incidence of post-surgery pain around the fixation site, while Bhatt et al. [

27] identified pain in 24% of cases. For pediatric patients, miniplates should ideally be removed within two to three months after fracture surgery to prevent growth restrictions. Nevertheless, Cole et al. [

28] suggest that removal should only be conducted in symptomatic cases. In our investigation, the removal rate was higher among patients under 40 years old, diverging from Park et al.’s [

29] findings that indicated higher removal rates among patients under 30 years old. Nonetheless, the previous study discovered elevated miniplate removal rates in patients aged 30 years or older.

Hardware failure represents another reason for miniplate removal. Over time, miniplates, composed of metal, can corrode, become brittle, or fracture. Hardware failure can lead to pain, discomfort, or even bone displacement. The incidence of hardware failure ranges from 1% to 23%, with most cases occurring within the first year of fixation [

30]. Retained miniplates might cause discomfort or pain, especially when located near facial muscles, nerves, or tendons. Such discomfort can impede the patient’s quality of life, especially if the miniplate is situated in a visible region, such as the cheek or jawbone.

Miniplates may also become visible through the skin or lead to scarring, which can be a cosmetic concern for some patients, prompting them to consider removal. Although the benefits of using titanium-based alloy miniplates for osteosynthesis are well-established, questions persist regarding their long-term effects. Recent research has concentrated on assessing the tissue surrounding removed titanium materials to investigate potential consequences. While the removal of titanium devices has typically been limited to cases of infection or exposure [

16], there are concerns about the local cellular impact of metallic particles that can infiltrate nearby tissues [

31,

32,

33] and potentially migrate through the lymphatic system to other organs [

34]. Studies have pointed to local reactions and immune-inflammatory responses in fibrous connective tissue deposits, with titanium being implicated in the induction of oxidative stress [

35]. Although allergic reactions to titanium-based alloys are rare, there have been reported cases of facial eczema [

36,

37].Tooth extraction constitutes another rationale for miniplate removal. During orthodontic treatment, teeth may need to be extracted to facilitate proper alignment. This can result in the removal of miniplates used for fracture stabilization. O’Connell et al. [

16] noted that out of 800 miniplates, two were removed due to tooth extraction.

Plate exposure arises when the miniplate becomes visible through the skin or mucosa. This can occur due to inadequate wound closure, insufficient soft tissue coverage, or suboptimal plate placement. Islamoglu et al. [

12] documented three out of 296 miniplates being removed due to plate exposure, while Gorrela et al. [

19] reported no cases of plate exposure among 437 miniplates.

Prosthetic rehabilitation serves as another cause for miniplate removal. Prosthetic rehabilitation involves dental implants, and in some instances, miniplates must be removed to facilitate this procedure. Islamoglu et al. [

12] reported four out of 296 miniplates being removed due to prosthetic rehabilitation.

Pain emerges as another impetus for the removal of miniplates employed in treating maxillofacial fractures. Pain can stem from various sources, such as nerve damage or impingement, plate migration, or cold intolerance. Pan et al. [

17] highlighted one case of miniplate removal due to cold intolerance and two instances stemming from plate failure out of 384 miniplates. Dae-Kyun et al. [

15] outlined five cases of plate removal due to palpable plates and six occurrences due to dental/nerve damage out of 609 miniplates.

Miniplate fractures can occur due to various factors, including improper plate placement, or excessive stress on the plate. Brown et al. [

11] detailed four cases of miniplate removal due to plate fracture out of 105 miniplates.

Loose fixation devices represent another cause for miniplate removal in maxillofacial fracture treatment. Loose fixation devices can result from several factors, including suboptimal plate placement, improper screw positioning, or undue stress on the plate. Rallis et al. [

14] noted seven instances of miniplate removal due to loose fixation devices out of 599 miniplates.

Patient request constitutes another rationale for the removal of miniplates employed in maxillofacial fracture treatment. Furthermore, other reasons encompass poor aesthetics, exposure, cold intolerance, nerve impairment, and cancer phobia.

Regarding the time span between initial surgery and miniplate removal, the majority of cases involved removal within one year. According to existing literature, most miniplate removals took place between 6 months and 1-year post-fixation, with some cases being removed even within less than 3 months following fixation. It is generally advised that miniplates be removed after confirming bone healing, typically within 6 months to a year. The broad spectrum of miniplate removal times identified in this study can be attributed to a complex interplay of patient-specific elements, fracture characteristics, surgical techniques, healing rates, and potential complications. Tailored patient care, clinical discretion, and continuous evaluation are crucial for determining the optimal timing of plate removal to ensure optimal results.

The mandible was the predominant site for miniplate removal, accounting for the majority (72.8%) of cases, particularly in the mandibular body and symphysis region. In a study by Park et al. [

29], they found the mandibular angle region to be the primary location for miniplate removal (39.5%), while Islamoglu et al. [

12] reported that the mandible was involved in 62.85% of hardware removal cases in the maxillofacial region. The increased tendency to remove miniplates from the mandible, as observed in our study and other research, may be linked to the mandible’s denser cortical bone structure relative to other facial bones. Additionally, the main blood supply to the mandible originates from the inferior alveolar artery and periosteum, both of which are susceptible to damage during trauma and surgical procedures [

14,

27]. Furthermore, the relatively thicker intraoral mucosa during surgical approaches heightens the risk of plate exposure.

Matthew and colleagues [

38] conducted an assessment of Champy titanium and stainless steel miniplates and screws used to stabilize mandibular fractures in an animal model. They retrieved these miniplates and screws at 4, 12, and 24 weeks after the surgery and concluded that there is no conclusive evidence supporting the routine removal of either titanium or stainless steel miniplates within six months following insertion. However, titanium tends to degrade over time due to wear and the release of particles. The resulting corrosion and wear byproducts, including metal ions or particles, can lead to tissue changes ranging from fibrosis to infection and necrosis [

39].

Given its superior corrosion resistance, non-carcinogenic nature, hypoallergenicity, non-toxicity, and excellent tissue compatibility, titanium hardware can be safely retained in the maxillofacial region [

40]. However, the metallic composition (stainless steel or titanium) played a negligible role in the number of miniplates removed, as the removal count was equivalent for both materials.

Initially, Champy [

2] recommended miniplate removal after three months of fixation, which became the established practice. Subsequently, authors leaned toward retaining Vitallium miniplates, which exhibited greater inertness. Frost et al. [

42] determined that approximately 18% of Vitallium miniplates necessitated removal for clinical reasons. Titanium emerged as a successful material in numerous surgical procedures, with nearly 100% of it being released at the site during osteosynthesis, remaining stable and clinically inert within surrounding tissues. Hence, routine removal of titanium miniplates, except in cases of infection, dehiscence, or hypersensitivity, was not deemed necessary. Miniplate removal should primarily address miniplate-related symptoms. While some authors advocate routinely removing miniplates to avert interference with jaw function and osteoporosis, most studies suggest removal only when symptoms manifest and discourage the routine removal of asymptomatic miniplates [

11,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Amidst the ongoing discourse and implications concerning metal plates, researchers have developed novel bioresorbable and bioactive materials as alternatives. These materials, such as polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, and copolymers of polyglycolic acid and polylactic acid, incorporated with hydroxyapatite in polylactic acid, stimulate the formation of new bone tissue without inducing mutagenic effects. Despite the appealing biodegradation characteristic of these materials, there is currently insufficient follow-up data from comparative studies between metallic alloys and bioresorbable substances [

51,

52,53].

The question of whether to remove miniplates after fracture healing remains a subject of debate within the medical community. One major influencer in this decision is the cost associated with miniplate removal, which can substantially vary among different countries. The cost of miniplate removal for jawbone fracture fixation is a multifaceted issue shaped by a range of factors. While procedural costs are relatively consistent, discrepancies in hospitalization expenses and potential complications can lead to significant cost disparities. Healthcare providers and policymakers should consider these economic factors while strategizing for jawbone fracture management and subsequent implant removal.

Limitations of this study encompass the lack of injury specifics due to the predominantly retrospective nature of the studies, as well as the challenge of tracking patient’s post-treatment for assessing post-operative complications.