1. Introduction

Information theory plays a crucial role in quantifying the uncertainty inherent in random phenomena. Its applications span a variety of areas, as detailed in Shannon’s influential work [

1]. Considering a non-negative random variable

X with an absolutely continuous cumulative distribution function (cdf)

and a probability density function (pdf)

, the Tsallis entropy of order

becomes a relevant measure as defined in [

2], given by

for all

where

denotes the expectation and

for

denotes the quantile function. In general, the Tsallis entropy can take negative values, but it can be made non-negative by choosing appropriate values of

. An important observation is that

, which illustrates the convergence of Tsallis entropy to Shannon differential entropy. Unlike the Shannon entropy, which exhibits additivity, the Tsallis entropy exhibits non-additivity. In particular, for two independent random variables

X and

Y in the Shannon framework

holds, while in the Tsallis framework we find

. The non-additive nature of the Tsallis entropy provides greater flexibility compared to the Shannon entropy, making it applicable in various areas of information theory, physics, chemistry, and technology.

Considering the lifetime of a newly introduced system denoted by

X, the tsallis entropy

serves as a measure of the inherent uncertainty of the system. However, there are cases where the actors have knowledge about the current age of the system. For example, they know that the system is operational at time

t and want to evaluate the uncertainty in the remaining lifetime given by

. In such scenarios, the conventional Tsallis entropy

no longer provides the desired insight. Therefore, a new measure, the residual Tsallis entropy (RTE), is introduced, defined as follows:

where

is the pdf of

and

is the survival function of

X.

Extensive research has been done in the literature to explore various properties and statistical applications of Tsallis entropy. For detailed insights, we recommend the work of Asadi

et al. [

3], Nanda and Paul [

4], Zhang [

5], Maasoumi [

6], Abe [

7], Asadi

et al. [

8], and the references cited in these works. These sources provide comprehensive discussions on this topic and allow for a deeper understanding of Tsallis entropy in various contexts.

The aim of this paper is to study the properties of RTE in terms of order statistics. We consider a random sample of size n from a distribution F denoted by . The order statistic represents the ordering of these sample values from smallest to largest, denoted . Order statistics are very important in many areas of probability and statistics because they can be used to describe probability distributions, to test how well a data set fits a particular model, to control the quality of a product or process, to analyze the reliability of a system or component, and for many other applications.

Moreover, they are indispensable in reliability theory, especially for studying the lifetime properties of coherent systems and performing lifetime tests on data obtained by various censoring methods. For a thorough understanding of the theory and applications of order statistics, we recommend the comprehensive review by David and Nagaraja [

9]. This source covers the topic in depth and provides useful insights into the theoretical and practical aspects of order statistics. Many researchers have studied the information properties of order statistics and have gained useful insights, which can be found in [

10,

11,

12] and the references therein. Zarezadeh and Asadi [

13] studied properties of residual Renyi entropy of order statistics and record values; see also [

14]. Continuing this line of research, our study aims to contribute to the field by investigating the properties of residual Tsallis entropy in terms of order statistics. More recently, Alomani and Kayid [

15] have studied the properties of the Tsallis entropy of a coherent and mixed system.

The results of this work is structured as follows: In

Section 2, we present the representation of RTE for order statistics denoted as

from a sample drawn from an arbitrary continuous distribution function

We express these RTE in terms of RTE for order statistics from a sample drawn from a uniform distribution. Since closed-form expressions for the RTE of order statistics are often not available for many statistical models, we derive upper and lower bounds to approximate the RTE. We provide several illustrative examples to demonstrate the practicality and usefulness of these bounds. In addition, we study the monotonicity properties of RTE for the extremum of a sample under mild conditions. We find that the RTEs of the extremum of a random sample exhibit monotonic behavior as the number of observations in the sample increases. However, we counter this observation by presenting a counterexample that demonstrates the non-monotonic behavior of RTE for other order statistics

with respect to sample size. To further analyze the monotonic behavior, we examine the RTE of order statistics

with respect to the index of order statistics

Our results show that the RTE of

is not a monotonic function of

i over the entire support of

Throughout the paper, “

" and “

" stand for usual stochastic and likelihood ratio orders, respectively, for more details on these orderings, we refer the reader to Shaked and Shanthikumar [

16].

2. Residual Tsallis Entropy of Order Statistics

Hereafter, we present an expression for the RTE of order statistics in relation to the RTE of order statistics from a uniform distribution. Let us consider the pdf and the survival function of

denoted by

and

, respectively, where

. It holds that

where

is known as the complete beta function; see e.g., David and Nagaraja [

9]. Furthermore, we can express the survival function

as follows:

where

is known as the incomplete beta functions. In this section, we adopt the notation

to denote that the random variable

Y follows a truncated beta distribution with pdf given by:

The paper is concerned with the study of the residual tsallis entropy of the random variable

, which measures the degree of uncertainty about the predictability of the residual lifetime of the system contained in the density of

. In reliability engineering,

-out-of-

n systems are an important type of structure. In this case, an

-out-of-

n system functions if and only if at least

components of

n components function. We consider a system consisting of independent and identically distributed components whose lifetimes are represented by

. The lifetime of the whole system is determined by the order statistic

, where

i denotes the position of the order statistic. When

, this corresponds to a serial system, while

represents a parallel system. In the context of

-out-of-

n systems operating at time

t, the RTE of

serves as a measure of entropy associated with the remaining lifetime of the system. This dynamic entropy measure provides system designers with valuable information about the entropy of

-out-of-

n systems in operation at a given time

t.

To increase computational efficiency, we introduce a lemma that establishes a relationship between the RTE of order statistics from a uniform distribution and the incomplete beta function. This relation is crucial from a practical point of view and allows for a more convenient computation of RTE. The proof of this lemma, which follows directly from the definition of RTE, is omitted here because it involves simple computations.

Lemma 1.

Suppose we have a random sample of size n from a uniform distribution on (0,1) and we arrange the sample values in ascending order where the i-th order statistic. Then

for all

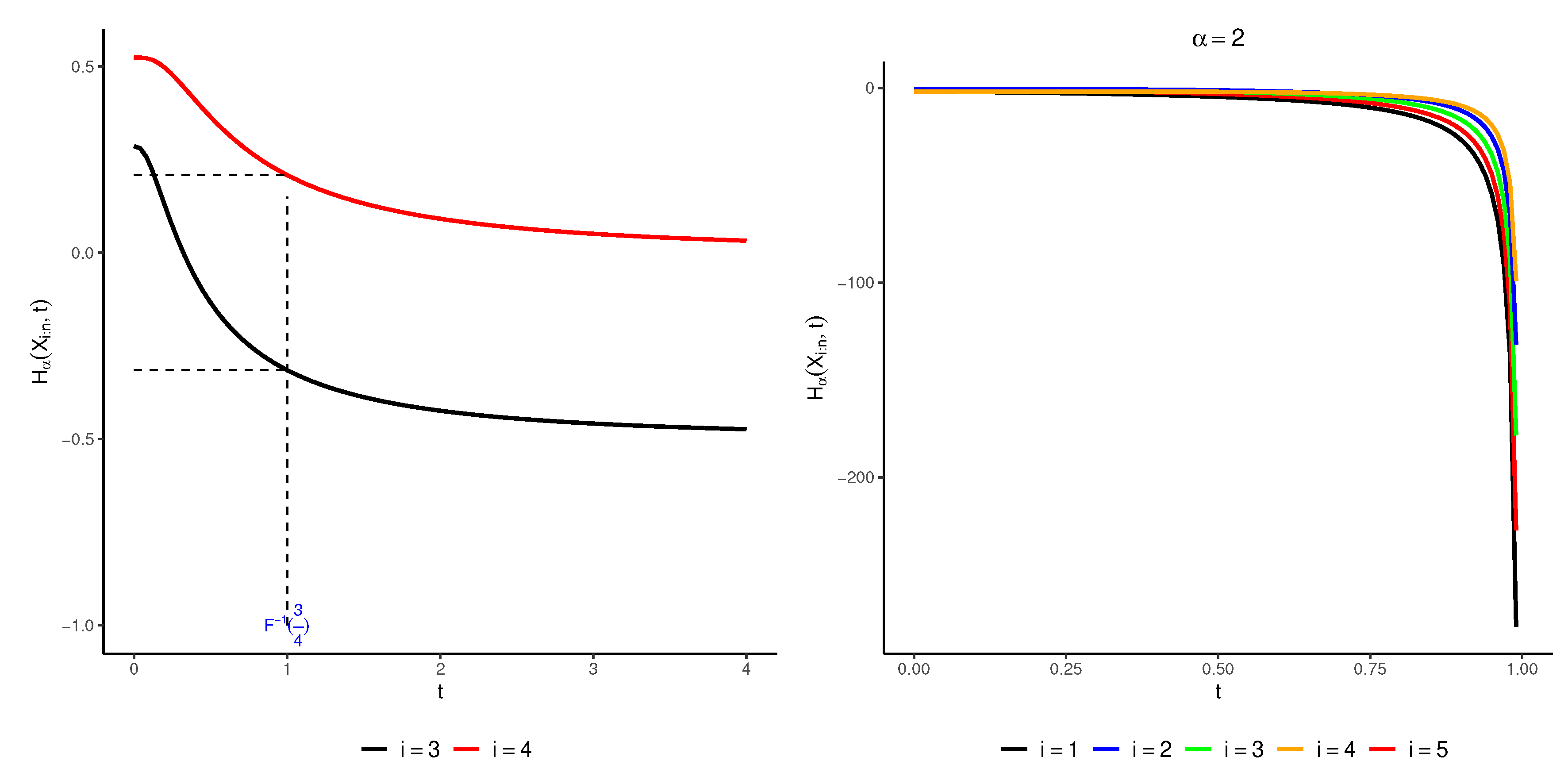

Using this lemma, researchers and practitioners can easily compute the RTE of order statistics from a uniform distribution using the well-known incomplete beta function. This computational simplification improves the applicability and usability of RTE in various contexts. In

Figure 1, we show the plot of

for different values of

and

when the total number of observations is

. The figure shows that there is no inherent monotonicity between the order statistics. However, in the following analysis (Lemma 3), we establish conditions under which a monotonic relationship can be established between the index

i and the number of components in the system. This lemma will provide valuable insight into the arrangement of the system components and the resulting effect on the reliability of the system.

The upcoming theorem establishes a relationship between the RTE of order statistics and the RTE of order statistics from a uniform distribution.

Theorem 1.

The residual Tsallis entropy of for all can be expressed as follows:

where

Proof. By using the change of

from (

2),(

3) and (

5), we get

The last equality is obtained from Lemma 1 and this completes the proof. □

After some calculation, it can be seen that when in (

7) the order

goes to unity, the Shannon entropy of

i-th order statistic from a sample of

F can be written as follows:

where

The specialized version of this result for

was already obtained by Ebrahimi

et al. [

12]. Below, we provide an example for illustration.

Example 1. Suppose that

X is a standard exponential distribution with mean unity. Then

and we have

Thus, from (

7), we obtain

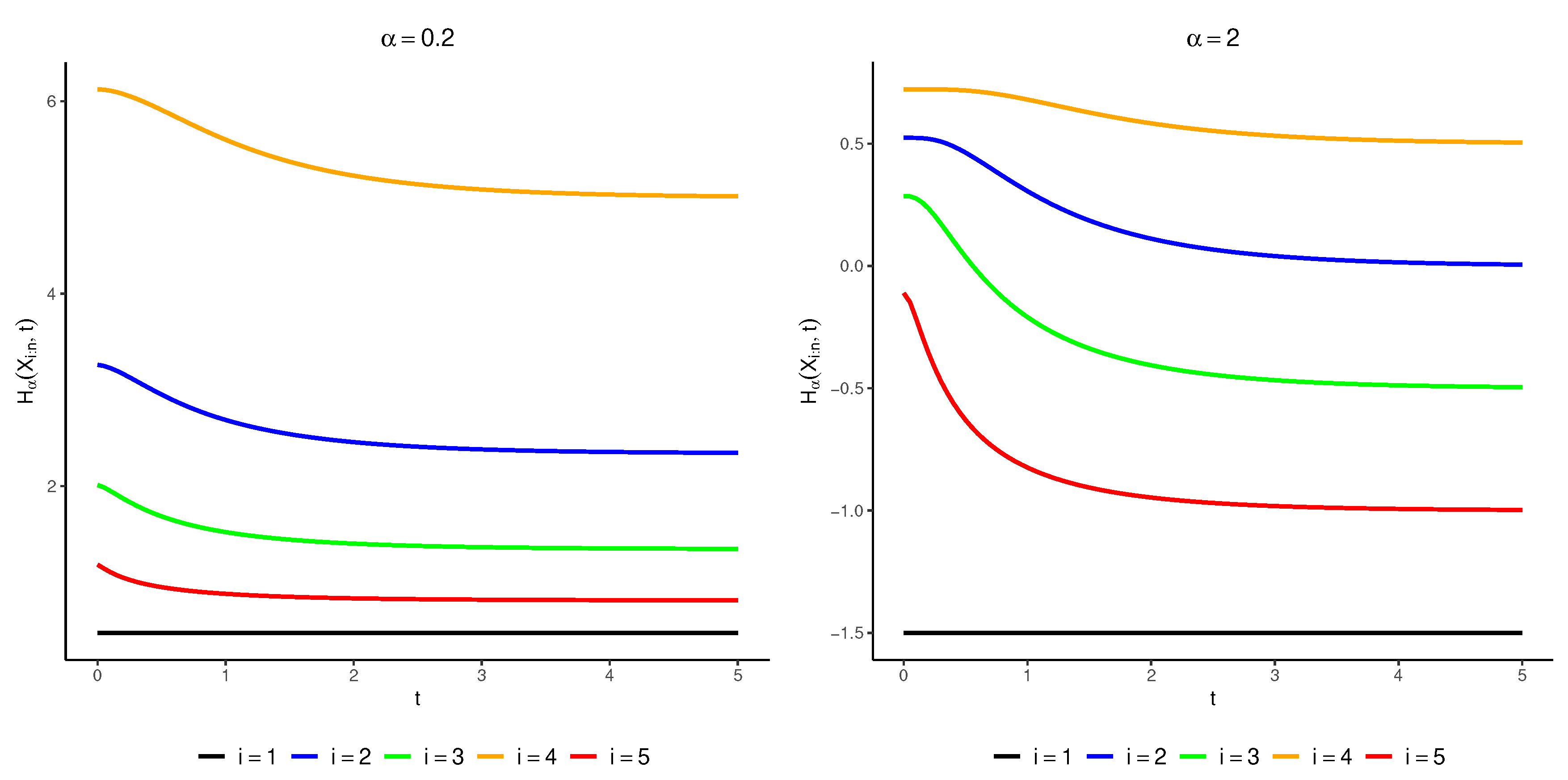

In

Figure 2, we plotted

for some values of

and

when

When

, we can use (

10) to get

Also, we know that

Therefore, we have

This finding reveals an intriguing characteristic: the discrepancy between the RTE of the lifetime of a series system and the RTE of each component is not influenced by time. Instead, it solely relies on two factors: the number of components within the system and the parameter

in the exponential case.

While we have successfully obtained a closed expression for the first order statistics of RTE in the exponential distribution, the task becomes significantly more difficult when we consider the higher order statistics in some other distributions. Unfortunately, closed-form expressions for the RTE of higher-order statistics in these distributions, as well as in many other distributions, are generally not available. Given this limitation, we are motivated to explore alternative approaches to characterizing the RTE of order statistics. We therefore propose to establish thresholds for the RTE of order statistics. To this end, we present the following theorem as a conclusive proof that provides valuable insight into the nature of these bounds and their applicability in practical scenarios.

Theorem 2. Consider a non-negative continuous random variable X with pdf f and cdf Let us denote the RTEs of X and the i-th order statistic as and respectively.

- (a)

Let where is the mode of the distribution of , then for we have

- (b)

Suppose we have where m is the mode of the pdf f, such that . Then, for any we obtain

Proof.

(a) By applying Theorem 2.3, we only need to find a bound for

To this aim, for

we have

The result now is easily obtained by recalling (

7).

(b) Since for

it holds that

one can write

The result now is easily obtained from relation (

7) and this completes the proof. □

The given theorem branches into two elements. The first subdivision, denoted (i), establishes a lower bound for the RTE associated with , denoted . It should be noted that the given lower bound can be transformed into an upper bound under certain conditions. This bound is formed by using the incomplete beta function together with the RTE of the original distribution. Conversely, in part (ii) of the theorem, a lower bound is introduced for the RTE of , denoted as . This lower bound is expressed via the RTE of order statistics from a uniform distribution and the mode, represented by m, of the underlying distribution. This finding provides interesting insights into the information properties of and provides a quantifiable measure of the lower bound of RTE with respect to the mode of the distribution.

In the following lemma we deal with the monotonic behavior of the RTE of order statistics. To lay the groundwork for our subsequent findings, we first introduce a central lemma that plays a fundamental role in our analysis.

Lemma 2.

Consider two non-negative functions, and , where is an increasing function. Let t and c be real numbers such that . Additionally, assume that the random variable follows a pdf , where as

Let r be real valued and define function as follows:

- (i)

If for then is an increasing function of

- (ii)

If for then is a decreasing function of

Proof. We just prove Part (i) since the proof for Part (ii) is similar. Assuming that

is differentiable in terms of

r, we can obtain

where

It is evident that

Using the fact that

and that

is an increasing function, one can show that

. This implies that (

13) is non-positive (non-negative), and hence

is an increasing function of

r. □

Corollary 1. Under the assumptions of Lemma 2, it can be proven that when is decreasing, the following holds:

- (i)

For then is a decreasing function of

- (ii)

If for then is a increasing function of

Due to Lemma 2, we can prove the following corollary for -out-of-n systems with components having uniform distributions.

Lemma 3.

- (i)

When considering a parallel (series) system consisting of n components with a uniform distribution over the unit interval, the RTE of the system lifetime decreases as the number of components increases.

- (ii)

If are integers, then for

Proof. (i) The presumption is that the system operates in parallel. Analogous reasoning can be applied to a series system to authenticate the outcome via Remark 2.9. From Lemma 1, we get

So, Lemma 2 readily reveals that

can be depicted as (

12) where

and

. We adopt the assumption, devoid of any generality loss, that

is a continuous variable. Considering

the ratio

is increasing (decreasing) in

t and hence we can establish the inequality

where the pdf of

is defined in equation (

11). By applying Lemma 2, we can deduce that the RTE of the parallel system is a decreasing function as the number of components increases.

(ii) To begin, we observe that

Furthermore, the pdf of

as stated in (

11) is expressed as

where in this context

and

Hence, it is apparent that for

and

(or

), we can write

In conclusion, it can be inferred for

that

and this signifies the end of the proof. □

Theorem 3. Consider a parallel (series) system consisting of n independent and identically distributed random variables representing the lifetime of the components. Assume that the common distribution function F has a pdf f that is increasing (decreasing) in its support. Then, the RTE of the system lifetime is decreasing in

Proof. Assuming that

then

indicates the pdf of

It is evident that

is increasing in

This implies that

and therefore

. Moreover, for

is an increasing (decreasing) function of

Therefore

From Theorem 2.3, for

we have

The first inequality is obtained by noting that

is non-negative. The last inequality is obtained from Part (i) of Lemma 3. Thus, one can conclude that

for all

□

Many distributions have decreasing pdfs, such as the exponential distribution, the Pareto distribution, and mixtures of these two. On the other hand, some distributions have increasing pdfs, such as the power distribution with its density function. Using part (i) of the corollary 1, we can prove a theorem for distributions whose pdfs go up or down. But we have to be careful, because this theorem does not work for all kinds of -out-of-n systems, as the next example shows.

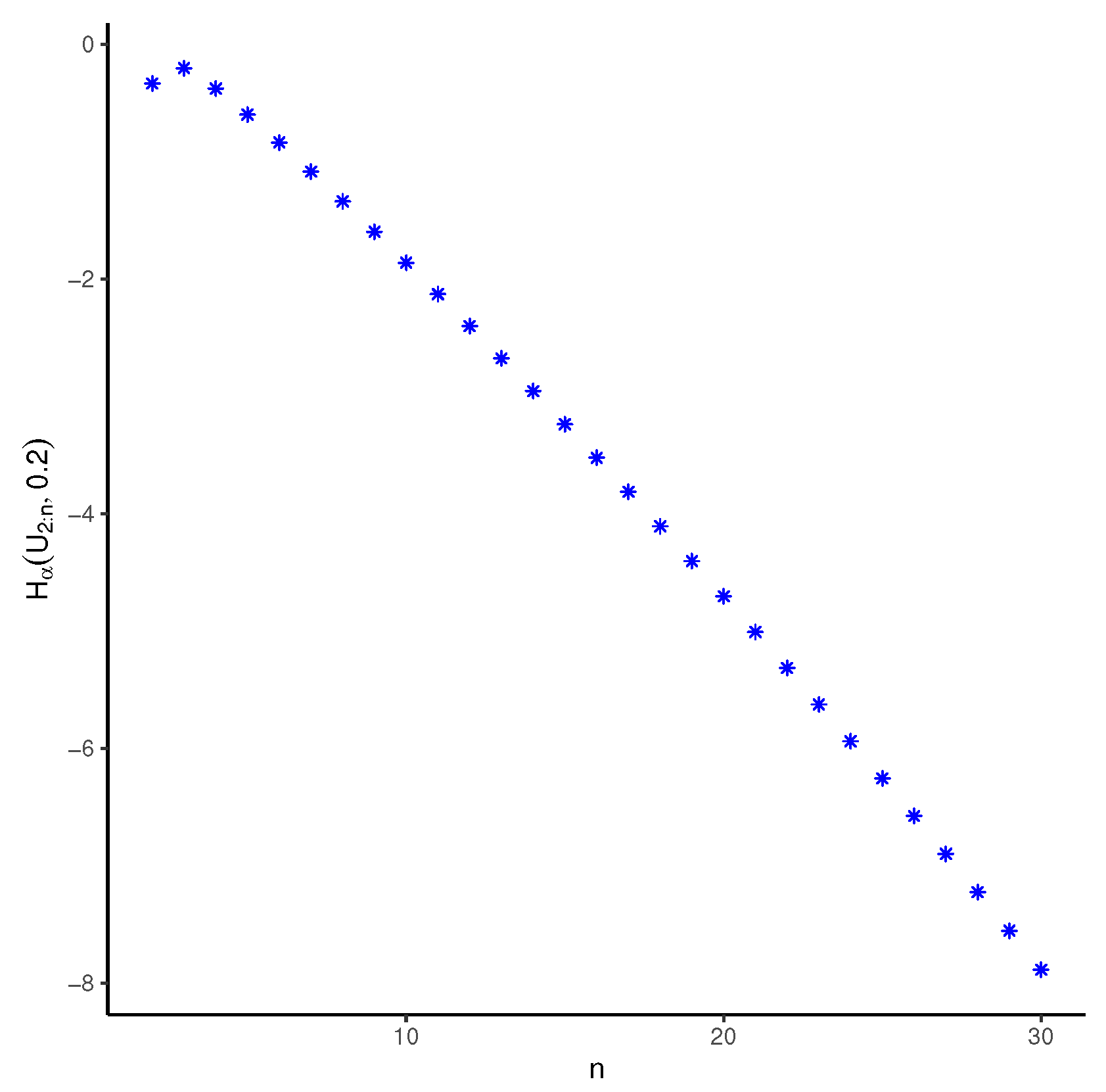

Example 2. Let us consider the system works if at least

of its

n components work. Then, the system’s lifetime is the second smallest component lifetime,

The components have the same distribution, uniform on

In

Figure 3, we see how the RTE of

changes with

n when

and

The graph shows that the RTE of the system does not always decrease as

n increases. For example, it reveals that

is less than that of

.

In reliability theory, we can imagine a case where the pdf decreases, and thus the RRE of a serial system decreases, when the system has more components. This happens when we have a lifetime model with a failure rate () that decreases with time. Then the data distribution must have a density function that also decreases. Some lifetime distributions in the reliability domain have the property that their RTE decreases as their scale parameter increases. This is the case, for example, with the Weibull distribution with a shape parameter less than one and with the Gamma distribution with a shape parameter less than one. Therefore, the RTE of a series system with components following these distributions becomes smaller as the number of components increases.

Now, we want to see how the RTE of order statistics changes with We use Part (ii) of Lemma 3, which gives us a formula for the RTE of in terms of

Theorem 4. Suppose X is a continuous random variable that is always positive. Its distribution function is F and its pdf is The pdf f decreases over the range of possible values of Let and be two whole numbers such that Then the RTE of the -th smallest value of X among n samples, is less than or equal to the RTE of the -th smallest value, for all values of X that are greater than or equal to the th percentile of

Proof. For

it is easy to verify that

and hence

. Now, we have

Using Part (ii) of Lemma 3 and the same reasoning as in the proof of Theorem 3, we can obtain the result. □

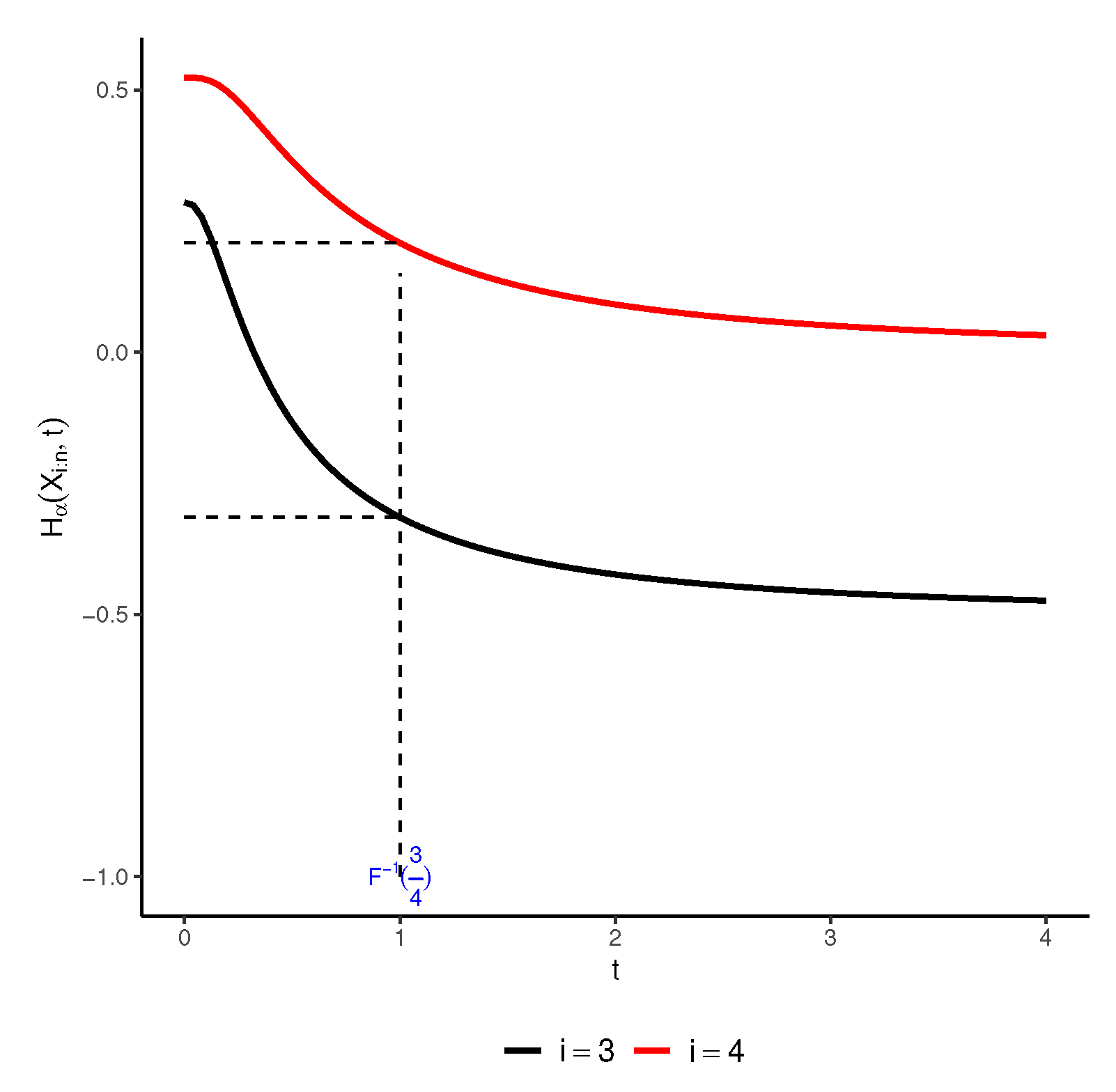

The following example shows that the condition cannot be dropped from the conditions of theorem.

Example 3. Assume the survival function of

X as

In

Figure 4, we see how the RTE of order statistics

for

and

, changes with

The plots show that the RTE of the order statistics does not always go up or down as

i goes up for all values of

For example, for the values of

the RTE is not monotonic in terms of

We can get a useful result from Theorem 4.

Corollary 2. Suppose X is a non-negative continuous random variable that is always positive with cdf F and pdf The pdf f decreases over the range of possible values of Let i be a whole number that is less than or equal to half of Then, the RTE of is increasing in i for values of t greater than the median of distribution.

Proof. Suppose

This means that

where

is the middle value of

By Theorem 4, we get for

that

□