Submitted:

20 September 2023

Posted:

21 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Breast Cancer biomarkers

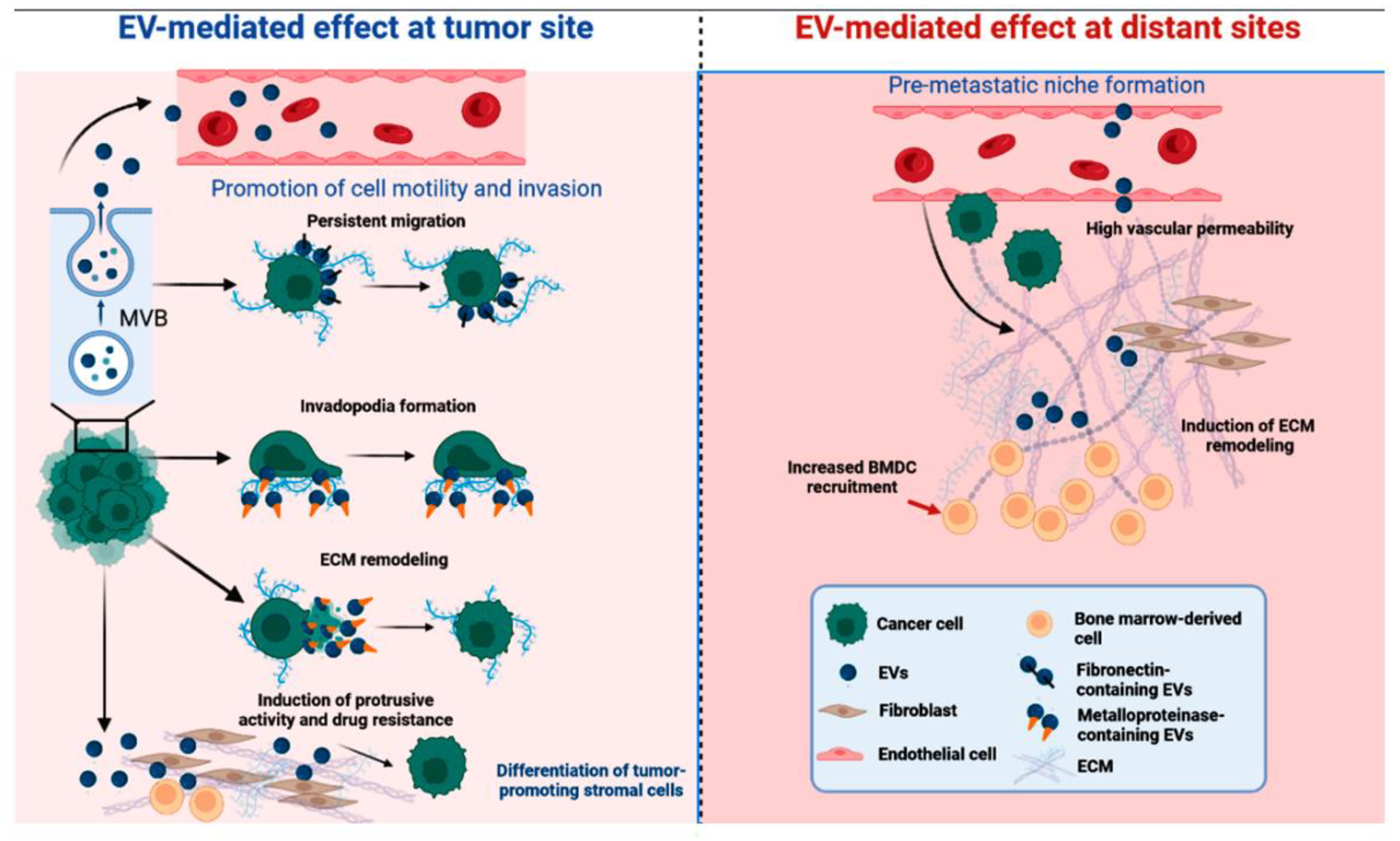

Extracellular vesicles in cancer intercellular communication

EVs shuttle cargo proteins that regulate tumorigenesis and show diagnostic and prognostic potential.

Mammary canine EVs proteomic studies are scarce

EVs proteomics may identify novel breast cancer biomarkers

| Author | Proteins |

|---|---|

| Khan et al. (2014) [36] | Survivin and splice variants |

| Harris et al. (2015) [37] | Vimentin, galectin-3-binding protein, annexin A1, plectin, protein CYR61, EGF-like repeat and discoidin I-like domain containg protein, filamin-B, protein-glutamine gamma-glutamytransferase 2 |

| Blomme et al. (2016) [38] | Myoferlin |

| Vardaky et al. (2016) [40] | Periostin |

| Hurwitz et al. (2016) [42] | Periostin, raftilin (lipid-raft regulating protein), fibulin-7 (adhesion molecule), and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (serine protease inhibitor) |

| Moon et al. (2016) [43] | Fibronectin |

| Lee et al. (2017) [45] | Del-1 |

| Gangoda et al. (2017) [46] | Ceruloplasmin, metadherin |

| Maji et al. (2017) [47] | Anexin A2 |

| Rontogianni et al. (2019) [48] | EPHA2, DNAJA1, PABPC1, and NRP1, ERBB2, GRB7, EIF3H and ARFGEF2 |

| Jordan et al. (2020) [20] | Spliceosome, transcription factors, ribosomal proteins, tRNA ligases, proteasome units, pyrophosphatase, annexin and vesicle markers LAMP-1 and EEA1, NUMA1, vitronectin, collagen, filamin proteins, and EDIL3 |

| Dalla et al. (2020) [49] | Actin cytoplasmic 1, pyruvate kinase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit alpha, sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit beta-3 and voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 |

| Risha et al. (2020) [50] | Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1), glypican 1 (GPC-1), and disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10) |

| Vinik et al. (2020) [51] | Fibronectin, FAK, MEC1, B-actine, p90RSK_pT573, N-Cadherin and C-Raf |

| Li et al. (2021) [52] | CD151 |

| Patwardhan et al. (2021) [53] | Thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) |

Concluding Remarks and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Miller, K.D.; Kramer, J.L.; Newman, L.A.; Minihan, A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenmo, K. Canine mammary gland tumors. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2003, 33, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszak, I.; Ruszczak, A.; Kanafa, S.; Kacprzak, K.; Król, M.; Jurka, P. Current biomarkers of canine mammary tumors. Acta Vet. Scand. 2018, 60, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhtakia, R. A Brief History of Breast Cancer: Part I: Surgical domination reinvented. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2014, 14, e166–e169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shiovitz, S.; Korde, L.A. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, K. Breast cancer: origins and evolution. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 3155–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimirzaie, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Akbari, M.R. Liquid biopsy in breast cancer: A comprehensive review. Clin. Genet. 2019, 95, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.J.A.d.; Causin, R.L.; Varuzza, M.B.; Calfa, S.; Hidalgo Filho, C.M.T.; Komoto, T.T.; Souza, C.d.P.; Marques, M.M.C. Liquid biopsy as a tool for the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvaei, S.; Daryani, S.; Eslami-S, Z.; Samadi, T.; Jafarbeik-Iravani, N.; Bakhshayesh, T.O.; Majidzadeh-A, K.; Esmaeili, R. Exosomes in cancer liquid biopsy: A focus on breast cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 10, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, T.K.Y.; Tan, P.H. Liquid biopsy in breast cancer: A focused review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021, 145, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, A.; Lenze, D.; Hummel, M.; Kohn, B.; Gruber, A.D.; Klopfleisch, R. Identification of six potential markers for the detection of circulating canine mammary tumour cells in the peripheral blood identified by microarray analysis. J. Comp. Pathol. 2012, 146, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Hu, J.; Hu, G. Biomarker studies in early detection and prognosis of breast cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1026, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gam, L.-H. Breast cancer and protein biomarkers. World J. Exp. Med. 2012, 2, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke, S.Y.; Lee, A.S.G. The future of blood-based biomarkers for the early detection of breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 92, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis, J.E.; Gromov, P.; Cabezón, T.; Moreira, J.M.A.; Ambartsumian, N.; Sandelin, K.; Rank, F.; Gromova, I. Proteomic characterization of the interstitial fluid perfusing the breast tumor microenvironment: a novel resource for biomarker and therapeutic target discovery. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2004, 3, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Buxton, I.L.O. Evolution of medical approaches and prominent therapies in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonyak, M.A.; Li, B.; Boroughs, L.K.; Johnson, J.L.; Druso, J.E.; Bryant, K.L.; Holowka, D.A.; Cerione, R.A. Cancer cell-derived microvesicles induce transformation by transferring tissue transglutaminase and fibronectin to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, 4852–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: where we are and where we need to go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.R.; Hall, J.K.; Schedin, T.; Borakove, M.; Xian, J.J.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Lyons, T.R.; Schedin, P.; Hansen, K.C.; Borges, V.F. Extracellular vesicles from young women’s breast cancer patients drive increased invasion of non-malignant cells via the Focal Adhesion Kinase pathway: a proteomic approach. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.-L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; Singh, S.; Williams, C.; Soplop, N.; Uryu, K.; Pharmer, L.; King, T.; Bojmar, L.; Davies, A.E.; Ararso, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Hernandez, J.; Weiss, J.M.; Dumont-Cole, V.D.; Kramer, K.; Wexler, L.H.; Narendran, A.; Schwartz, G.K.; Healey, J.H.; Sandstrom, P.; Labori, K.J.; Kure, E.H.; Grandgenett, P.M.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; de Sousa, M.; Kaur, S.; Jain, M.; Mallya, K.; Batra, S.K.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Brady, M.S.; Fodstad, O.; Muller, V.; Pantel, K.; Minn, A.J.; Bissell, M.J.; Garcia, B.A.; Kang, Y.; Rajasekhar, V.K.; Ghajar, C.M.; Matei, I.; Peinado, H.; Bromberg, J.; Lyden, D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabalee, J.; Towle, R.; Garnis, C. The role of extracellular vesicles in cancer: cargo, function, and therapeutic implications. Cells 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-X.; Gires, O. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in breast cancer: From bench to bedside. Cancer Lett. 2019, 460, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfleisch, R.; Klose, P.; Weise, C.; Bondzio, A.; Multhaup, G.; Einspanier, R.; Gruber, A.D. Proteome of metastatic canine mammary carcinomas: similarities to and differences from human breast cancer. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 6380–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Herráez, P.; Martín de las Mulas, J.; Rodríguez, F.; Déniz, J.M.; Espinosa de los Monteros, A. Expression of 14-3-3 σ protein in normal and neoplastic canine mammary gland. Vet. J. 2011, 190, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagarlamudi, K.K.; Westberg, S.; Rönnberg, H.; Eriksson, S. Properties of cellular and serum forms of thymidine kinase 1 (TK1) in dogs with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and canine mammary tumors (CMTs): implications for TK1 as a proliferation biomarker. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, S.C.; Shrivastava, S.; Saxena, S.; Kumar, N.; Maiti, S.K.; Mishra, B.P.; Singh, R.K. Surface plasmon resonance immunosensor for label-free detection of BIRC5 biomarker in spontaneously occurring canine mammary tumours. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhaikrue, I.; Srisawat, W.; Nambooppha, B.; Pringproa, K.; Thongtharb, A.; Prachasilchai, W.; Sthitmatee, N. Identification of potential canine mammary tumour cell biomarkers using proteomic approach: Differences in protein profiles among tumour and normal mammary epithelial cells by two-dimensional electrophoresis-based mass spectrometry. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2020, 18, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarindo, G.H.; Novais, A.A.; Chuffa, L.G.A.; Zuccari, D.A.P.C. Metabolic alterations in canine mammary tumors. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-M.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.W.; Yoon, J.-H.; Kim, B.-G.; Cho, J.-Y. Common plasma protein marker LCAT in aggressive human breast cancer and canine mammary tumor. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, Y.G.; Mulder, L.M.; van Zeijl, R.J.M.; Paskoski, L.B.; van Veelen, P.; de Ru, A.; Strefezzi, R.F.; Heijs, B.; Fukumasu, H. Proteomic Analysis Identifies FNDC1, A1BG, and Antigen Processing Proteins Associated with Tumor Heterogeneity and Malignancy in a Canine Model of Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.H.-C.; Chang, S.-C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H.-P. Serum Level of Tumor-Overexpressed AGR2 Is Significantly Associated with Unfavorable Prognosis of Canine Malignant Mammary Tumors. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gast, M.-C.W.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H. Clinical proteomics in breast cancer: a review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 116, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondermarck, H.; Tastet, C.; El Yazidi-Belkoura, I.; Toillon, R.-A.; Le Bourhis, X. Proteomics of breast cancer: the quest for markers and therapeutic targets. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latterich, M.; Abramovitz, M.; Leyland-Jones, B. Proteomics: new technologies and clinical applications. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2737–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Bennit, H.F.; Turay, D.; Perez, M.; Mirshahidi, S.; Yuan, Y.; Wall, N.R. Early diagnostic value of survivin and its alternative splice variants in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.A.; Patel, S.H.; Gucek, M.; Hendrix, A.; Westbroek, W.; Taraska, J.W. Exosomes released from breast cancer carcinomas stimulate cell movement. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomme, A.; Fahmy, K.; Peulen, O.; Costanza, B.; Fontaine, M.; Struman, I.; Baiwir, D.; de Pauw, E.; Thiry, M.; Bellahcène, A.; Castronovo, V.; Turtoi, A. Myoferlin is a novel exosomal protein and functional regulator of cancer-derived exosomes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 83669–83683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, C.; Ba, Z.; Xu, H.; Yan, X.; Liu, W.; Zhu, B.; Wang, L.; Ren, C. Myoferlin, a multifunctional protein in normal cells, has novel and key roles in various cancers. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7180–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardaki, I.; Ceder, S.; Rutishauser, D.; Baltatzis, G.; Foukakis, T.; Panaretakis, T. Periostin is identified as a putative metastatic marker in breast cancer-derived exosomes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 74966–74978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorafshan, S.; Razmi, M.; Safaei, S.; Gentilin, E.; Madjd, Z.; Ghods, R. Periostin: biology and function in cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, S.N.; Rider, M.A.; Bundy, J.L.; Liu, X.; Singh, R.K.; Meckes, D.G. Proteomic profiling of NCI-60 extracellular vesicles uncovers common protein cargo and cancer type-specific biomarkers. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 86999–87015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, P.-G.; Lee, J.-E.; Cho, Y.-E.; Lee, S.J.; Jung, J.H.; Chae, Y.S.; Bae, H.-I.; Kim, Y.-B.; Kim, I.-S.; Park, H.Y.; Baek, M.-C. Identification of Developmental Endothelial Locus-1 on Circulating Extracellular Vesicles as a Novel Biomarker for Early Breast Cancer Detection. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-C.; Yang, C.-H.; Cheng, L.-H.; Chang, W.-T.; Lin, Y.-R.; Cheng, H.-C. Fibronectin in cancer: friend or foe. Cells 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.; Jung, J.H.; Park, H.Y.; Moon, P.-G.; Chae, Y.S.; Baek, M.-C. Exosomal Del-1 as a Potent Diagnostic Marker for Breast Cancer: Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, e748–e756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangoda, L.; Liem, M.; Ang, C.-S.; Keerthikumar, S.; Adda, C.G.; Parker, B.S.; Mathivanan, S. Proteomic Profiling of Exosomes Secreted by Breast Cancer Cells with Varying Metastatic Potential. Proteomics 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.; Chaudhary, P.; Akopova, I.; Nguyen, P.M.; Hare, R.J.; Gryczynski, I.; Vishwanatha, J.K. Exosomal annexin II promotes angiogenesis and breast cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontogianni, S.; Synadaki, E.; Li, B.; Liefaard, M.C.; Lips, E.H.; Wesseling, J.; Wu, W.; Altelaar, M. Proteomic profiling of extracellular vesicles allows for human breast cancer subtyping. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla, P.V.; Santos, J.; Milthorpe, B.K.; Padula, M.P. Selectively-Packaged Proteins in Breast Cancer Extracellular Vesicles Involved in Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risha, Y.; Minic, Z.; Ghobadloo, S.M.; Berezovski, M.V. The proteomic analysis of breast cell line exosomes reveals disease patterns and potential biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinik, Y.; Ortega, F.G.; Mills, G.B.; Lu, Y.; Jurkowicz, M.; Halperin, S.; Aharoni, M.; Gutman, M.; Lev, S. Proteomic analysis of circulating extracellular vesicles identifies potential markers of breast cancer progression, recurrence, and response. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Pi, H.; Li, Z.; Yao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Shen, P.; Li, X.; Ji, J. Proteomic Landscape of Exosomes Reveals the Functional Contributions of CD151 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2021, 20, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patwardhan, S.; Mahadik, P.; Shetty, O.; Sen, S. ECM stiffness-tuned exosomes drive breast cancer motility through thrombospondin-1. Biomaterials 2021, 279, 121185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).