1. Introduction

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) is a rare systemic necrotizing vasculitis, affecting small-to-medium sized vessels [

1]. EGPA is included in the spectrum of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) as approximately 40% of the patients present antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) mainly specific for myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA) [

2]. Prevalence in the general population is 10.7-13 per million, with an annual incidence estimated as 1-4 per million per year [

3]. EGPA’s clinical manifestations are extremely heterogeneous affecting different organs and systems with a variable involvement over time. The disease has unique characteristics as it combines respiratory manifestations to hypereosinophilic disorders and AAV features [

4]; [

5] and different areas of the upper respiratory tract can be affected with Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) involvement. The aim of this study was to assess type of ENT manifestations present at time of diagnosis in our cohort of EGPA patients and correlate the findings with distinct variables as sex, age at diagnosis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) status and previous reports of the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study conducted by the Division of Internal Medicine and Clinical Immunology of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Federico II, medical records of 25 EGPA patients (15males, 10 females) of the last 10 years (2013-2023), were retrospectively examined, to assess type and prevalence of ENT manifestations during initial hospital access for clinical evaluation and diagnosis. Consultation was performed by Ear, Nose and Troat (ENT) hospital specialists. Inclusion criteria for clinical records research were: final diagnosis of EGPA according to the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria [

6] and/or the definition of EGPA adopted by the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference [

2] and more recently by the classification criteria of the ACR/EULAR 2022[

7]. For each patient, baseline characteristics (sex, age at diagnosis), laboratory findings (eosinophil count and ANCA status (MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA) at time of diagnosis were registered (

Table 1).

Extra-ENT clinical manifestations (pulmonary infiltrates, peripheral nervous system involvement, arthralgia/arthritis, cardiac involvement, glomerulonephritis, ocular involvement, skin involvement) were also assessed. In addition, medical records of computer tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the maxillary sinus and ENT examination with rhinofibrolaryngoscopy with flexible instruments were reported together with information on previous surgery for ENT disease. The following ENT features, in accordance to the ENT area of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) [

8], were registered:

1.Bloody nasal discharge / crusts / ulcers / granulomata

2.Paranasal sinus involvement

3.Subglottic stenosis /corditis/vocal cord paralysis /hoarseness/dysphonia

4.Conductive hearing loss / tympanic membrane changes/ otorrhea

More in detail, medical records and ENT consultation were also examined for the following features: epistaxis, nasal swelling, rhinorrhea, turbinate hypertrophy, nasal septum perforation, saddle nose, nasal bone deformities, eosinophilic rhinitis, subglottic stenosis, corditis, vocal cord paralysis, hoarseness/dysphonia, hearing loss, tympanic membrane changes, otorrhea, chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyposis (CRSwNP and CRSsNP, respectively).

All procedures complied with the Helsinski Declaration of 1964, subsequently revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Correlation of baseline features (age, sex and ANCA status) with the different ENT clinical manifestations were tested by Fisher’s exact test analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). Differences were considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

In our cohort of EGPA patients, ENT clinical manifestations at time of diagnosis were: chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP) (13 patients, 52%), turbinate hypertrophy (12 patients, 48%), nasal swelling (10 patients, 40%), rhinorrhoea (10 patients, 40%), chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP) (8 patients, 32%), nasal bone deformities (8 patients, 32%), nasal crusts (5 patients, 20%), nasal mucosal ulcers (3 patients, 12%), corditis (3 patients, 12%), hoarseness/dysphonia (3 patients, 12%), hearing loss (3 patients, 12%), eosinophilic rhinitis (1 patient, 4%), mucoceles (1 patient, 4%). Subglottic stenosis, vocal cord paralysis, tympanic membrane change or otorrhea were not registered at time of diagnosis. Main ENT manifestations at time of diagnosis in our EGPA patients are reported in

Table 2 A and 2 B (divided by BVAS area).

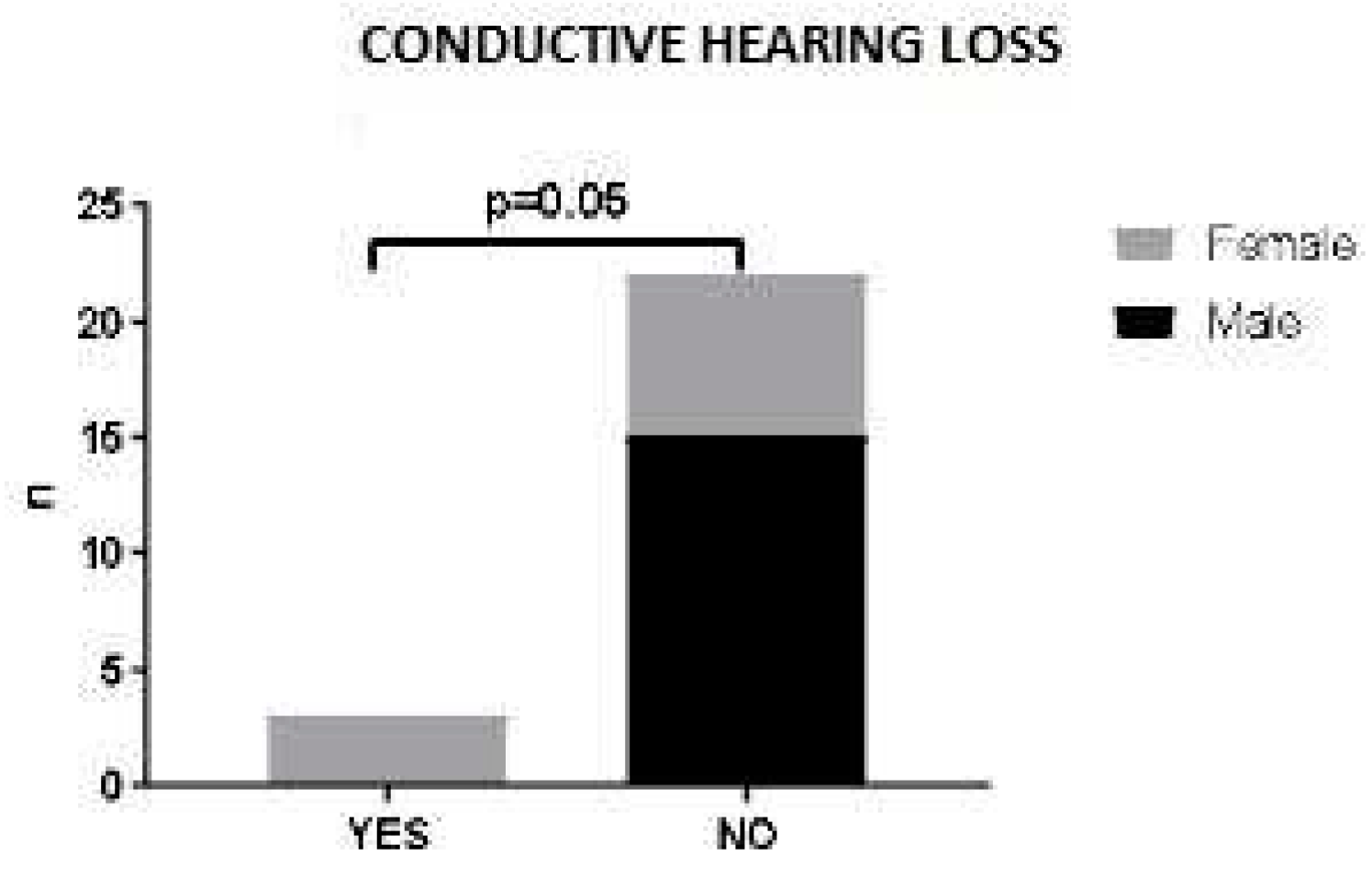

No statistically significant correlation was found between sex, age at diagnosis or ANCA status and ENT clinical manifestations (data not shown). A trend was observed between sex and ENT involvement: in our patient cohort, hearing loss was associated with female sex. Indeed, male patients did not present this ENT manifestation at time of diagnosis (p=0.052) (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

In the course of EGPA it is possible to identify a “prodromal” phase characterized by respiratory manifestations of the upper and lower airways which can even precede systemic manifestations by many years [

9]. The second stage of the disease, is defined as "eosinophilic" for the presence in circulation of a high quantity of tissue infiltrating eosinophils, is characterized by systemic involvement with fever, asthenia, weight loss and arthromyalgia whereas the third phase is defined as "vasculitic", characterized by the worsening of systemic symptoms and by the involvement of the peripheral nervous, renal and cutaneous systems. EGPA diagnosis should be always considered in patients with asthma, chronic rhinosinusitius and eosinophilia who develop end-organ involvement (peripheral neuropathy, lung infiltrates, cardiomyopathy or other complications [

10].

Nasal and sinus involvement has been always listed among clinical criteria for EGPA diagnosis since introduction of 1990’s ACR classification criteria [

6] to 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference [

2] until the latest ACR/EULAR 2022 classification criteria [

7]. Thus, nasal and sinus involvement are central to the ENT manifestations in EGPA and important for its diagnosis. In CRSwNP associated to EGPA, polyps commonly reoccur after surgical excision and frequently coexist with other manifestations such as otitis media [

11].

A retrospective analysis by Bacciu A et al., on twenty-eight EGPA patients showed evidence of ENT involvement in 21 (75%) at disease onset and/or diagnosis. Only 2/21 (9.5 %) received EGPA diagnosis by an otolaryngologist. The most common ENT manifestations were allergic rhinitis in 9 patients (42.8%) and nasal polyposis in 16 patients (76.1%). Three patients (14.2%) developed chronic rhinosinusitis without polyps, three (14.2%) had nasal crusting [

12].

In the first systematic review of the literature on 1175 patients with EGPA, among clinical and cohort studies results, 48.0% to 96.0% of patients presented with various rhinologic conditions, including sinusitis, nasal polyps, rhinitis, nasal crusting, and nasal obstruction. Patients with documented nasal or paranasal sinus biopsies demonstrated eosinophilic infiltration in 35% to 100% of samples with no evidence of necrotizing vasculitis or eosinophilic granuloma [

13].

In a 2018 retrospective observational study, the diagnosis of EGPA was suspected by linking refractory otitis media with effusion (OME) and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis that affected all patients object of the study. Almost 60 percent of patients who required grommet insertion for otitis media with effusion (OME) in the setting of nasal polyps met the diagnostic criteria or had a formal diagnosis of EGPA. Thus, the co-existing presence of nasal polyps and resistant OME should raise the possibility of EGPA. The pathophysiology of EGPA indicates that initially rhinological manifestations are the main symptoms, and recognition of nasal polyposis and OME together may lead to earlier referral and subsequent diagnosis of the disease given that the pulmonary manifestations are frequently quiescent [

14].

In our cohort, 52% of the patients had CRSwNP. CRSwNP were present in our EGPA patients independently of the ANCA status, similarly to previous literature data [

10,

15]. In addition, different rhinologic manifestations were present in our patients at time of diagnosis: turbinate hypertrophy (48%), nasal swelling (40%), rhinorrhoea (40%), chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP) (32%), nasal bone deformities 32%), nasal crusts ( 20%), nasal mucosal ulcers (12%), eosinophilic rhinitis (4%), mucoceles (4%). The latter, are inflammatory changes of the sinus mucosa that often occur after surgery for recalcitrant nasal polyposis [

16] and overcomplicate CRSwNP management in EGPA [

17].

4.1. Ear involvement

As for otologic manifestations, serous otitis media, purulent otitis media, unilateral facial palsy progressive sensorineural hearing loss were reported in a small number of patients (4.7%, 4,7%, 4,7% and 9.5%, respectively) in the retrospective analysis by Bacciu A et al. [

12]. Otitis media, sensorineural hearing loss, mastoiditis and facial nerve palsies have been reported by the Goldfarb J M et al. systematic review [

13]. In addition, in the 2018 Irish Study, sixteen patients were affected by otitis media with effusion (OME) before receiving EGPA diagnosis [

14]. In a more recent systematic review on the diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients with otologic manifestations of EGPA, a systematic search for relevant published literature in PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE databases was done: Hearing loss and middle ear effusion were the most common presentation in EGPA [

18]. Middle ear effusion in EGPA is characterized by thick, mucoid aural discharge with increased number of eosinophils, and conductive hearing loss may result from effusion or obstruction resulting from eosinophilic granuloma [

12]. In a recent korean case-control study (2022), the most prevalent manifestation associated with OME was conductive hearing loss, followed by mixed type hearing loss. Therefore, OME can result in a mild-to-moderate conductive hearing loss. Interestingly, the maintenance of steroid dose for EGPA should be adequately adjusted to control ear symptoms and to prevent progressive hearing loss [

19]. In addition, neurological involvement most commonly manifests as mononeuritis multiplex or hearing loss in EGPA patients [

20]. Hearing loss was reported in 12% of our patients and was associated to female sex.

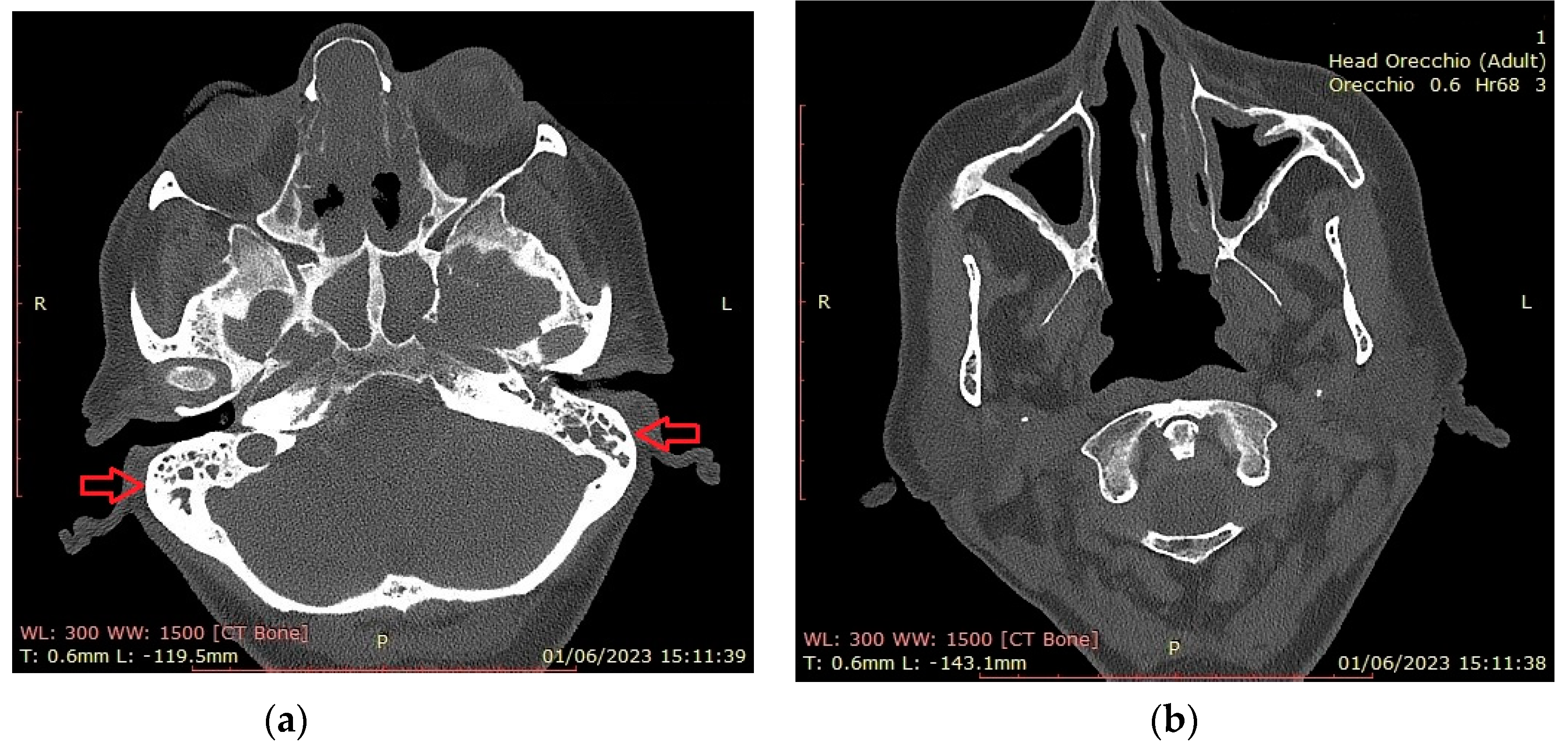

Figure 2 shows CT findings in a EGPA female patient with mastoiditis, hearing loss and CRSwNP. The patient was on dupilumab treatment for recurrent CRSwNP and had previous nasal and sinus surgery.

4.2. Laryngeal involvement

Larynx is also involved in EGPA. In a 1997 case report on a 59-year-old EGPA patient, a video-laryngostroboscopy revealed paresis and hypotonia of the right vocal cord with a decrease in the adduction phase but a normal appearance of the laryngeal mucosa. Authors reported manifestations likely due to a vasculitic process of the vasa nervorum of the vagus nerve, mainly of the superior laryngeal nerve. Another clue supporting this theory was the efficacy of steroid treatment in improving laryngeal symptoms [

21]. In a 2005 retrospective analysis of 21 EGPA patients selected from the SE.PRI. VA. study group no cases of laryngeal involvement were reported [

12]. In a more recent study, recurrent laryngeal polyposis has been reported and extravascular eosinophilic histology was demonstrated for laryngeal polyps [

13]. In another study on 43 EGPA patients, laryngeal movements during laryngoscopy were not compromised, with no specific lesions observed under conventional white light or narrow-band imaging. Most of the patients (n = 31; 72 %), showed a certain degree of laryngeal hyperaemia, limited to the arytenoids in 23 cases (53.4%) and more diffuse to the whole larynx in 8 cases (18.6%). Thick endolaryngeal mucus was found in 10 patients (23.2%) and laryngeal swelling in 17 patients (39.5 %; mild in 11 patients and moderate in 6 patients). Vocal fold swelling was generally slight and present in a minority of patients (n = 11; 25.6 %). Narrow-band imaging endoscopy confirmed the aforementioned features, showing particular enhancement of the microvessels and their dilation. The mean Reflux Finding Score was low (3.3 ± 3.2), with only seven patients (16.2 per cent) scoring 7 or higher.

Corditis (12%) and hoarseness/dysphonia (12%) were the only laryngeal manifestations in our cohort of patients at time of diagnosis.

While primary laryngeal involvement in EGPA patients is very uncommon according to the reviews, laryngeal inflammation seems to be a common feature as laryngitis or gastroesophageal reflux. This suggests that the clinical meaning of laryngeal involvement in assessing disease activity for the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score should be reconsidered. However, ENT evaluation is needed to rule out possible subglottic inflammation [

22].

4.3. Microscopic features of head and neck manifestations in EGPA

Tissue samples for ENT regions may be examined but biopsies of the sino-nasal mucosa/ polyps are often non-diagnostic without evidence of necrotizing vasculitis or eosinophilic granulomas [

12]. When present, the granulomatous inflammation in the upper respiratory tract shows central necrosis containing nuclear fragments of granulocytes and is surrounded by a palisade of epithelioid cells and by large numbers of eosinophils. Granulomatous inflammation and areas of necrosis are often confluent, with a ‘geographic’ appearance at low magnification. Multinucleated giant cells are almost invariably present and are pathognomonic for EGPA when seen in isolation in lung or upper airway biopsy samples, in cytology specimens from bronchoalveolar lavage, or in nasal swabs taken when clinical features suggestive of AAV are present [

23]. In the Goldfarb JM et al. systematic review, 48.0% to 96.0% of patients with some head and neck involvement presented eosinophilic infiltration in 35% to 100% of samples nasal or paranasal sinus biopsies [

13].

In our patients, eosinophilic infiltrations were reported in the medical records of polyp tissue biopsies or nasal cytology (data not shown).

EGPA is a rare vasculitis and multicenter studies should be auspicable to generate more significant clinical observations. In this context, our study has some limitations as the retrospective design and the small number of subjects make it difficult to extend the results to EGPA patients overall.

5. Conclusions

EGPA’s complex pattern of clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory values and histologic findings request a multidisciplinary collaboration between allergists-immunologists otolaryngologists, pulmonologists, pathologists and other specialists in order to fastly built a valid diagnostic work-up. ENT manifestations in EGPA may be polymorphic and precocious, and EGPA diagnosis should be always considered in patients with ENT involvement with comorbid asthma and eosinophilia who develop other clinical complications. ENT specialists should be aware of their leading position in this diagnostic race.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

upon demand.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Vaglio, A., C. Buzio, and J. Zwerina, Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss): state of the art. Allergy 2013, 68, 261–273. [CrossRef]

- Jennette, J.C., et al., 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Lane, S.E., R. Watts, and D.G. Scott, Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2005, 7, 270–275. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, M.E., et al., Unmet needs and evidence gaps in hypereosinophilic syndrome and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023, 151, 1415–1428. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagni, F., F. Bello, and G. Emmi, Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Dissecting the Pathophysiology. 2021, 8.

- Masi, A.T., et al., The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum 1990, 33, 1094–1100.

- Grayson, P.C., et al., 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2022, 81, 309–314. [CrossRef]

- Kermani, T.A., et al., The Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score as a Measure of Disease Activity in Patients with Giant Cell Arteritis. J Rheumatol 2016, 43, 1078–1084. [CrossRef]

- Guillevin, L., et al., Churg-Strauss Syndrome Clinical Study and Long-Term Follow-Up of 96 Patients. 1999, 78, 26–37.

- Emmi, G., et al., Evidence-Based Guideline for the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2023, 19, 378–393. [CrossRef]

- Bacciu, A., et al., Nasal polyposis in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 325–329. [CrossRef]

- Bacciu, A., et al., Ear, nose and throat manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2006, 126, 503–509. [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, J.M., et al., Head and Neck Manifestations of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis:A Systematic Review. 2016, 155, 771–778.

- Kavanagh, F.G., et al., Polyps, grommets and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Laryngol Otol, 2018, 132, 236–239. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comarmond, C., et al., Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65, 270–281. [CrossRef]

- Chobillon, M.A. and R. Jankowski, Relationship between mucoceles, nasal polyposis and nasalisation. Rhinology 2004, 42, 219–224.

- Detoraki, A., et al., Real-life evidence of low-dose mepolizumab efficacy in EGPA: a case series. Respiratory Research 2021, 22, 185. [CrossRef]

- Ashman, P.E., et al., Otologic Manifestations of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: A Systematic Review. Otol Neurotol 2021, 42, e380–e387. [CrossRef]

- Kang, N., et al., Intractable middle ear effusion in EGPA patients might cause permanent hearing loss: a case–control study. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2022, 18, 68.

- Almaani, S., et al., ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: An Update. J Clin Med 2021, 10.

- Mazzantini, M., et al., Neuro-laryngeal involvement in Churg-Strauss syndrome. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 1998, 255, 302–306. [CrossRef]

- Seccia, V., et al., Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and laryngeal involvement: review of the literature and a cross-sectional prospective experience. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 2018, 132, 619–623.

- Kitching, A.R., et al., ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2020, 6, 71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).