Submitted:

09 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study population

Allergens

Plasma collection and isolation and culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Antibodies

Cell surface and intracellular staining

Detection of sCD23 and cytokine levels

Statistics

Results

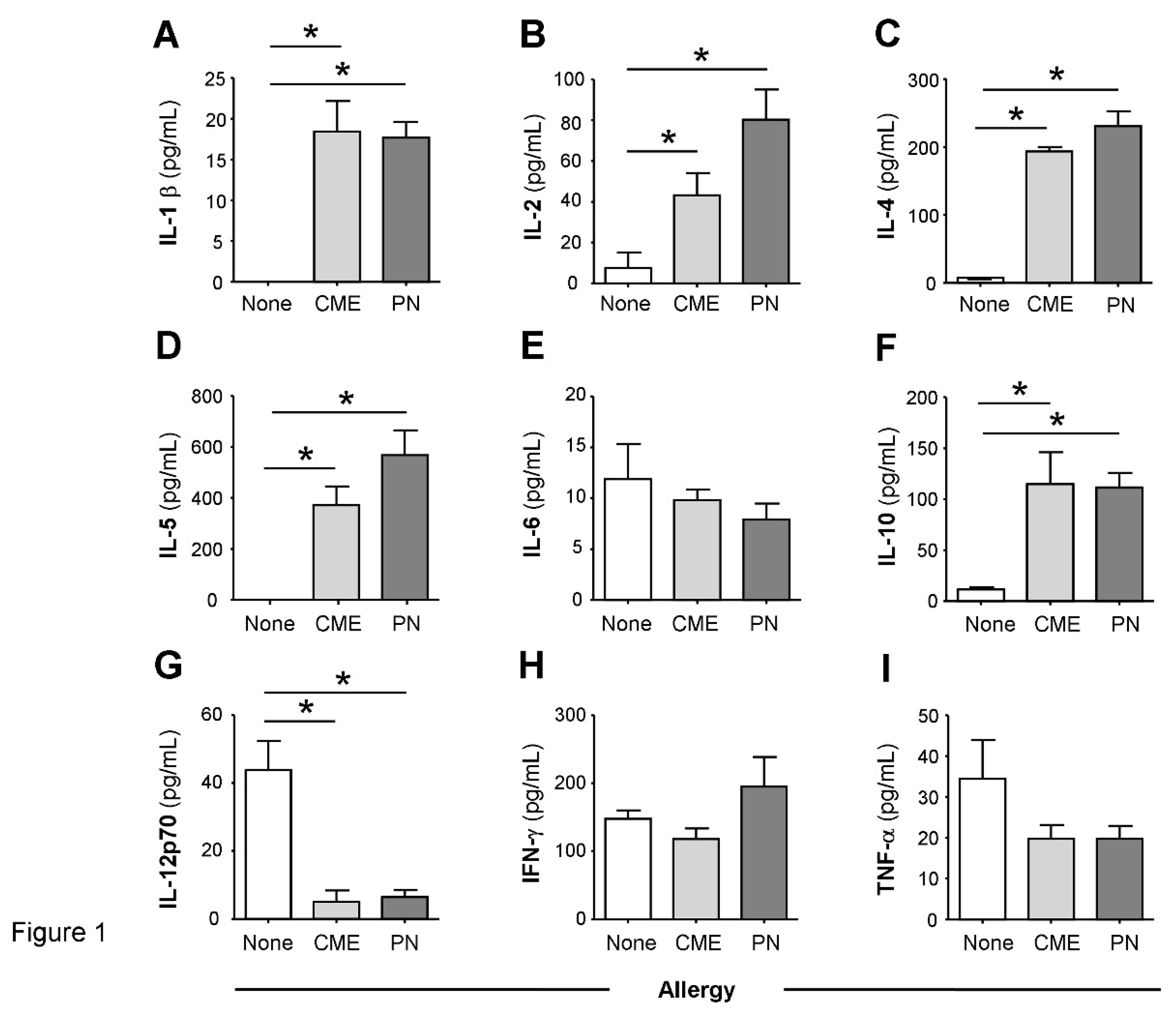

Constitutive plasma cytokines in food allergy

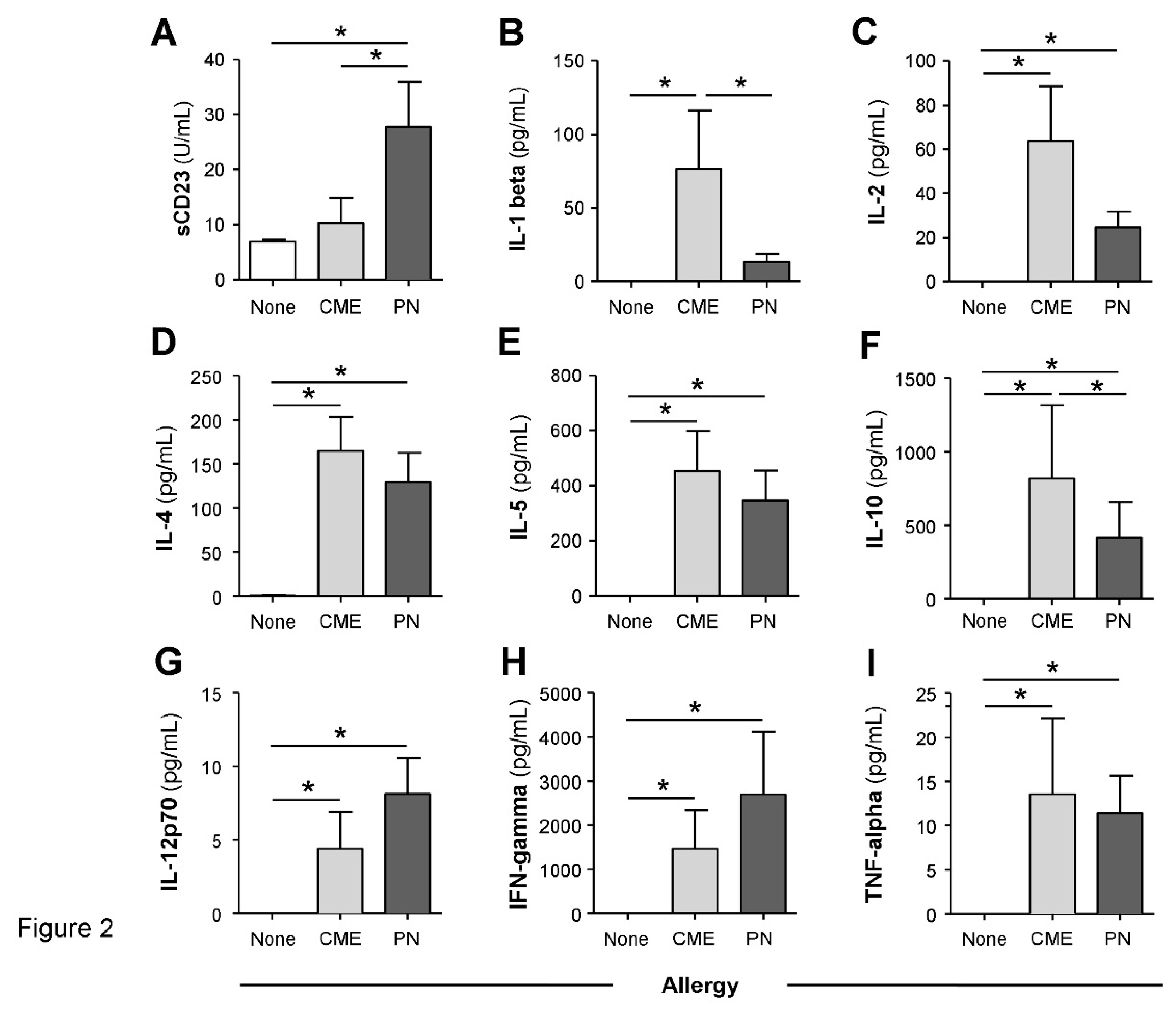

Spontaneous in vitro sCD23 release and cytokine secretion by MNC in food allergy

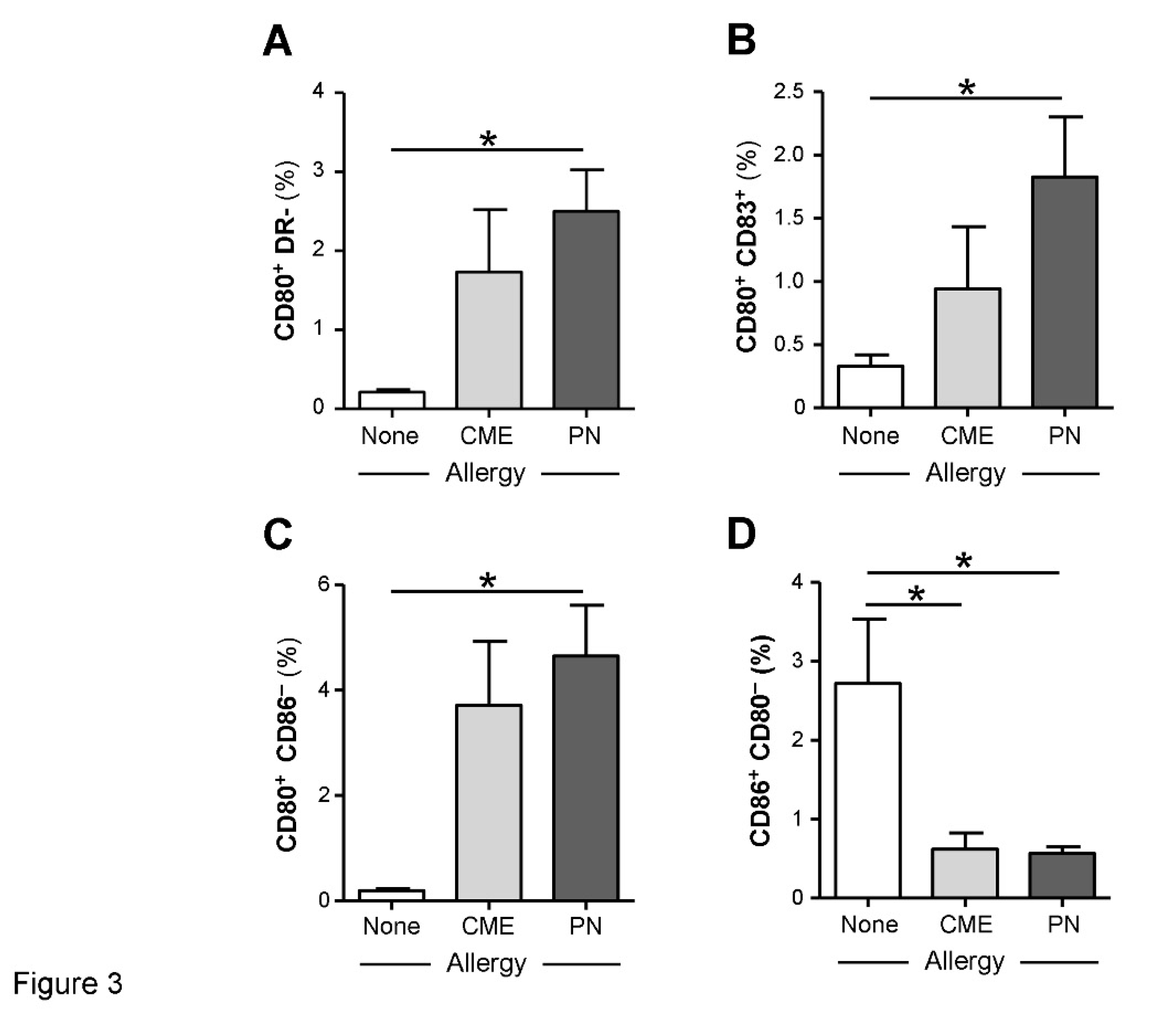

Allergy-associated abnormalities in the expression of costimulatory molecules

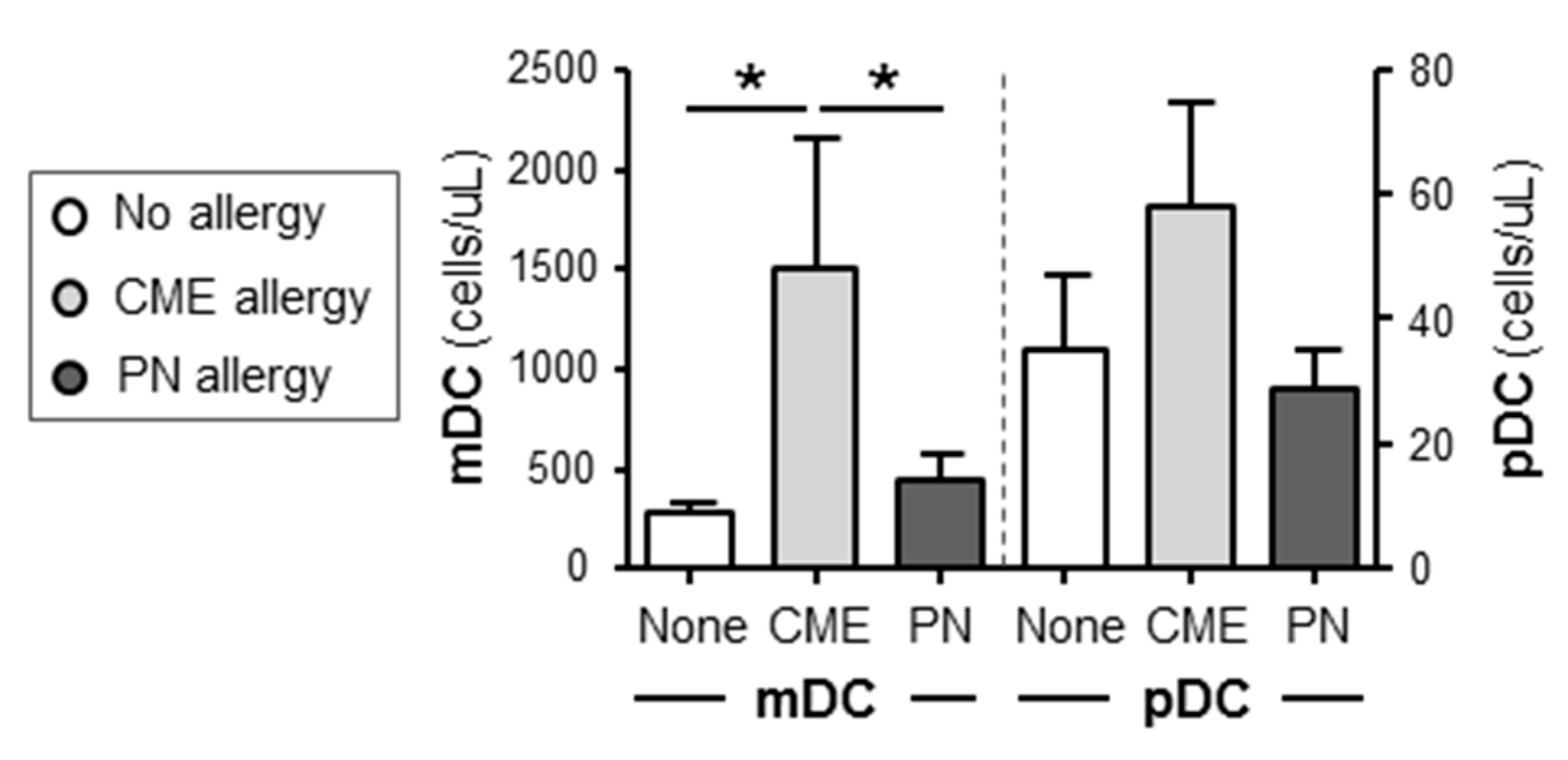

Differences in the numbers of immune cell subsets

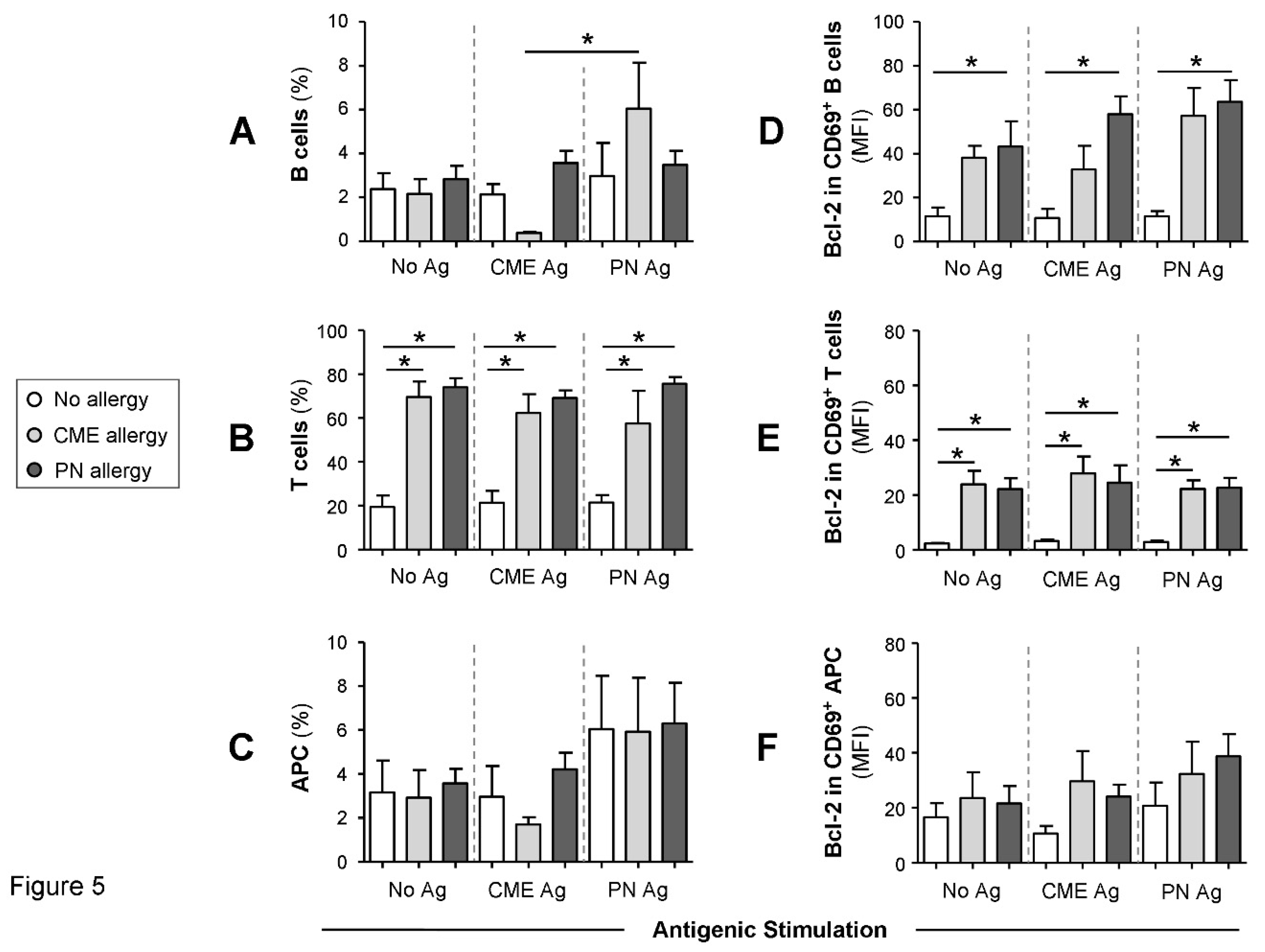

Survival advantage of immune cell subtypes from allergic children

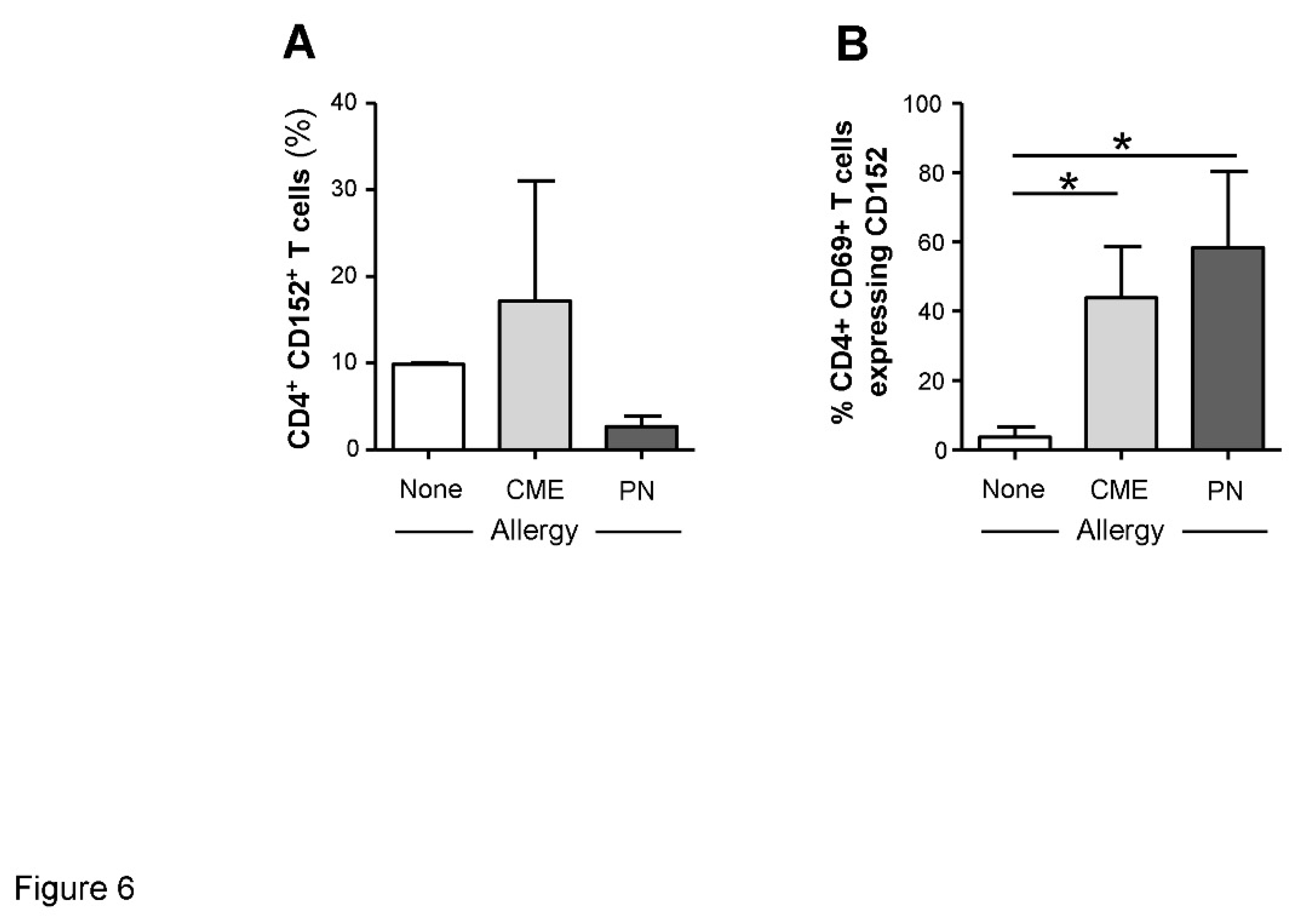

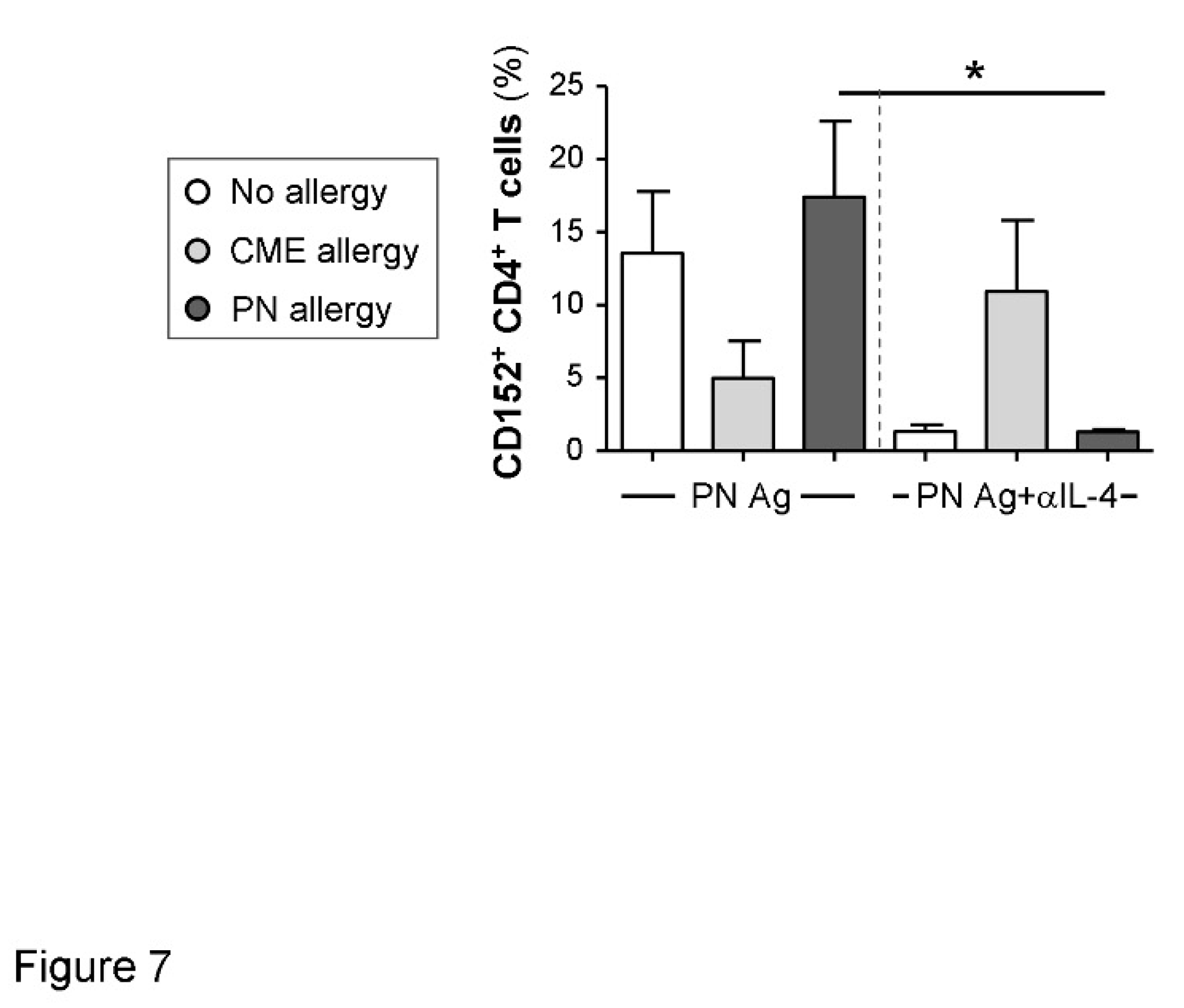

IL-4-mediated regulation of CD152 expression

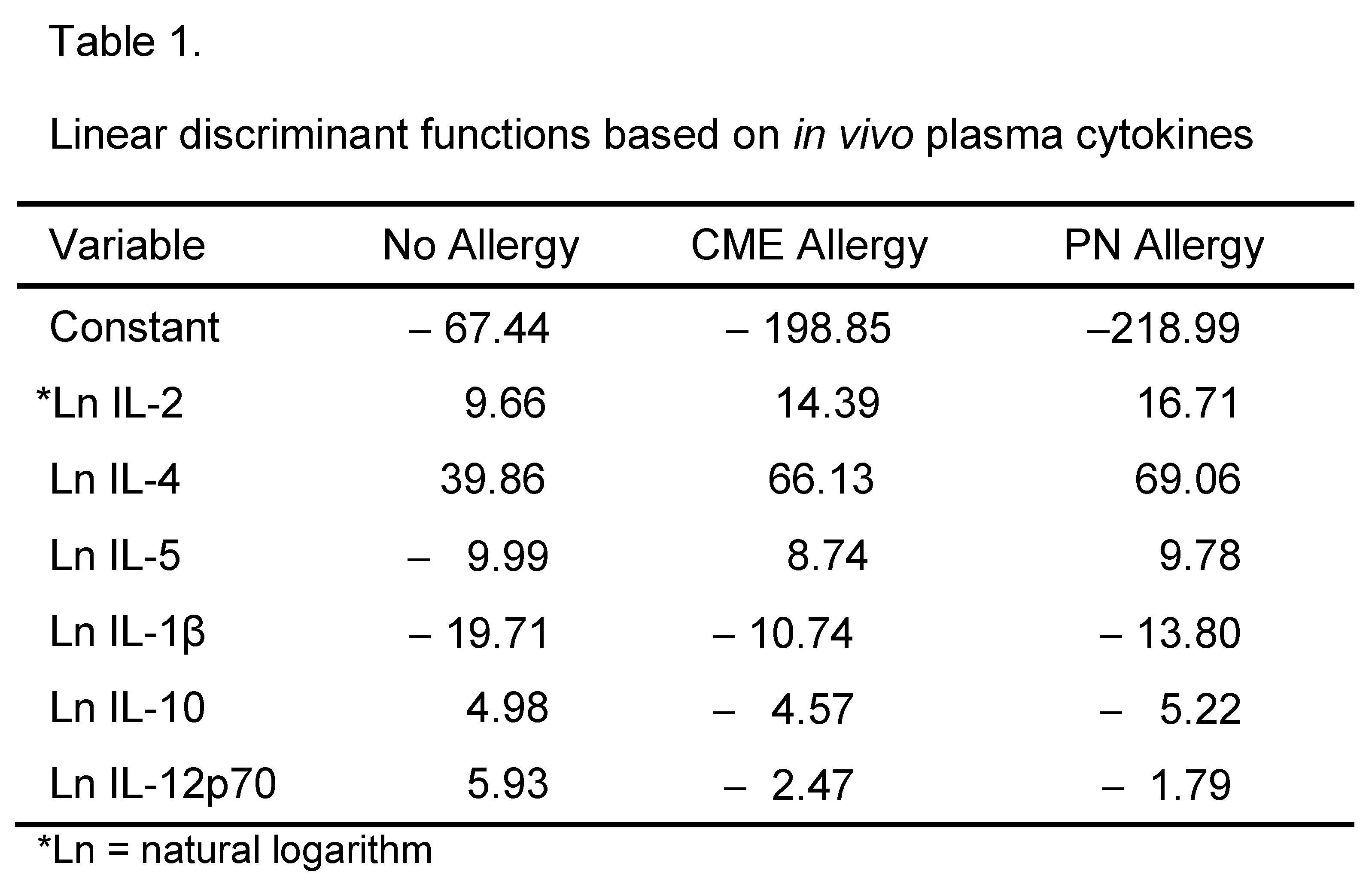

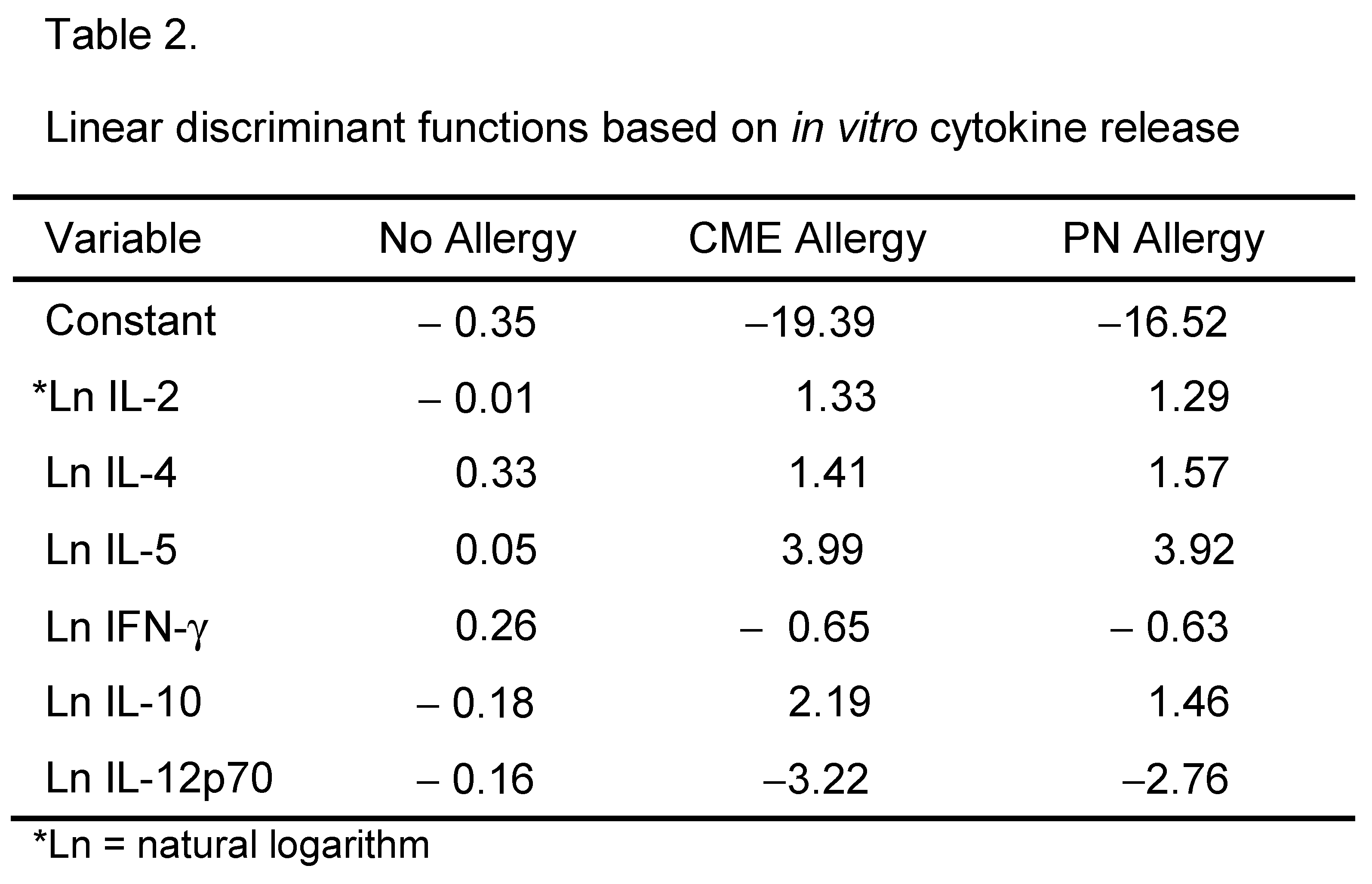

Canonical discriminant analysis

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ling Z, Li Z, Liu X, Cheng Y, Luo Y, Tong X, Yuan L, Sun J, Li L, C. Altered Fecal Microbiota Composition Associated with Food Allergy in Infants. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 2546–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomicić S, Fälth-Magnusson K, Böttcher MF. Dysregulated Th1 and Th2 responses in food-allergic children--does elimination diet contribute to the dysregulation? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010, 4, 649–655. [Google Scholar]

- Chatila, T. Regulatory T cells: Key Players in Tolerance and Autoimmunity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2009, 38, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon HK, Lee CG, So JS, Chae CS, Hwang JS, Sahoo A, Nam JH, Rhee JH, Hwang KC, Im SH. Generation of regulatory dendritic cells and CD4+Foxp3+ T cells by probiotics administration suppresses immune disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107, 2159–2164.

- Ruiter B, Shreffler WG. The role of dendritic cells in food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012, 129, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst O, Mowat AM. Oral tolerance to food protein. Mucosal Immunol 2012, 5, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodowczyk A, Markiewicz L, Wróblewska B. Mutations in the filaggrin gene and food allergy. Prz Gastroenterol 2014, 9, 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Guerrerio AL, Chichester KL, Bieneman AP, Hamilton RA, Wood RA, Schroeder JT. Dendritic cell and T cell responses in children with food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2011, 41, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesteanu AC, Katsikis PD. Memory T cells need CD28 costimulation to remember. Semin Immunol. 2009, 21, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriello F, Sethna MP, SD, Schweitzer AN, Tivol EA, Jacoby D, Strom TB, Simpson EM, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. B7-1 and B7-2 Have Overlapping, Critical Roles in Immunoglobulin Class Switching and Germinal Center Formation. Immunity 1997, 6, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk F, Nierkens S, de Jong W, Wehrens EJ, Boon L, van Kooten P, Knippels LM, Pieters R. The CD28/CTLA-4-B7 signaling pathway is involved in both allergic sensitization and tolerance induction to orally administered peanut proteins. J Immunol 2007, 178, 6894–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenschow DJ, Walunas TL, Bluestone JA. CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Ann Rev Immunol 1996, 14, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijk F, Hoeks S, Nierkens S, Koppelman SJ, van Kooten P, Boon L, Knippels LM, Pieters R. CTLA-4 signaling regulates the intensity of hypersensitivity responses to food antigens, but is not decisive in the induction of sensitization. J Immunol 2005, 174, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohmann U, Orabona C, Fallarino F, Vacca C, Calcinaro F, Falorni A, Candeloro P, Belladonna ML, Bianchi R, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. CTLA-4–Ig regulates tryptophan catabolism in vivo. Nat. Immunol 2002, 3, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannin P, Delneste Y, Lecoanet-Henchoz S, Gauchat J-F Jonathan Ellis J, Bonnefoy J-Y. CD86 (B7.2) on human B cells. A functional role in proliferation and selective differentiation into IgE and IgG4-producing cells. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 15613–15619. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AM, Hobson PS, utton MR, Kao MW, Drung B, Schmidt B, Fear DJ, Beavil AJ, McDonnel JM, Sutton BJ, Gould HJ. Soluble CD23 Controls IgE Synthesis and Homeostasis in Human B Cells. J Immunol 2012, 188, 3199–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould HJ, Sutton BJ. IgE in allergy and asthma today. Nature Rev Immunol 2008, 8, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edkins AL, Borland G, Acharya M, CogdellRJ, Ozanne BW, Cushley W. Differential regulation of monocyte cytokine release by αV and β2 integrins that bind CD23. Immunol 2012, 136, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, J. White LJ. Bradford W. Ozanne BW, Pierre Graber P, Jean-Pierre Aubry J-P, Jean-Yves Bonnefoy JY, William Cushley W. Inhibition of Apoptosis in a Human Pre-B–Cell Line by CD23 Is Mediated Via a Novel Receptor. Blood 1997, 90, 234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Cairns JA, Holder MJ, Abbot SD, Jansen KU, Bonnefoy JY, Gordon J, MacLennan I C. Recombinant 25-kDa CD23 and interleukin 1 alpha promote the survival of germinal center B cells: evidence for bifurcation in the development of centrocytes rescued from apoptosis. Eur J Immunol 1991, 21, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, S. Regulation of lymphocyte survival by the BCL-2 gene family. Ann Rev Immunol 1995, 13, 513–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graninger WB, Steiner CW, Graninger MT, Aringer M, Smolen JS. Cytokine regulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression in lymphocytes of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Death Diff 2000, 7, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronica MA, Goenka S, Boothby M. IL-4-dependent induction of BCL-2 and BCL-X(L)IN activated T lymphocytes through a STAT6- and pi 3-kinase-independent pathway. Cytokine 2000, 12, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man AL, Bertelli E, Regoli M, Chambers SJ, Nicoletti C. Antigen-specific T cell–mediated apoptosis of dendritic cells is impaired in a mouse model of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004, 113, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arques JL, Regoli M, Bertelli E, Nicoletti C. Persistence of apoptosis-resistant T cell-activating dendritic cells promotes T helper type-2 response and IgE antibody production. Mol Immunol 2008, 45, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicherer SH, Food allergy from infancy through adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020, 8, 1854–1864.

- Clemente A, Chambers SJ, Lodi F, Nicoletti C, Brett GM. Use of indirect competitive ELISA for the detection of Brazil nut in food products. Food Contr 2004, 15, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivory K, Chambers SJ, Pin C, Prieto E, Arques JL, Nicoletti C. Oral delivery of Lactobacillus casei Shirota modifies allergen-specific immune responses in allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2008, 38, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D. , Turzer S, Ganchev G, Schütte W, Seliger B, Möller. Monitoring Blood Immune Cells in Patients with Advanced Small Cell Lung Cancer Undergoing a Combined Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor/Chemotherapy. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Uchida Y, Kurasawa K, Nakajima H, Nakagawa N, Tanabe E, Sueishi M, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Increase of dendritic cells of type 2 (DC2) by altered response to IL-4 in atopic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001, 108, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho D, Gomez M, Sanchez-Madrid F. CD69 is an immunoregulatory molecule induced following activation. Trends Immunol 2005, 26, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandiyan P, Gärtner G, Soezeri O, Radbruch A, Schulze-Osthoff K, Brunner-Weinzierl MC. CD152 (CTLA-4) determines the unequal resistance of Th1 and Th2 cells against activation-induced cell death by a mechanism requiring PI3 kinase function. J Exp Med 2004, 199, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd CE, Taylor A, Schneider H. CD28 and CTLA-4 coreceptor expression and signal transduction. Immunol Rev 2009, 229, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre ML, Noel PJ, Eisfelder BJ, Chuang E, Clark MR, Reiner SL, Thompson CB. Regulation of surface and intracellular expression of CTLA4 on mouse T cells. J Immunol 1996, 157, 4762–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioli, C, Gatta L, Ubaldi V, Doria G. Inhibition of IgG1 and IgE production by stimulation of the B cell CTLA-4 receptor. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 5530–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdis CA, Blesken T, Akdis M, Wüthrich B, Blaser K. Role of interleukin-10 in specific immunotherapy. J. Clin Invest 1998, 102, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang TD, Tang MLK, Koplin JJ, Licciardi PV, Eckert JK, Tan T, Gurin LC, Ponsonby A-L, Allen KL. Characterization of plasma cytokines in an infant population cohort of challenge-proven food allergy. Allergy 2013, 68, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Weber CB, Alexander SI, Henault LE, James L, Lichtman AH. IL-4 Enhances IL-10 Gene Expression in Murine Th2 Cells in the Absence of TCR Engagement. J Immunol 1999, 162, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotoski LC, Simons FER, Chooniedass R, Liem J, Ostopowich, Becker AB, HayGlass KT. Are Plasma IL-10 Levels a Useful Marker of Human Clinical Tolerance in Peanut Allergy? PLoS One 2010, 5, e11192. [Google Scholar]

- Stone SF, Cotterell C, Isbister GK, Holdgate A, Brown SG. Elevated serum cytokines during human anaphylaxis: Identification of potential mediators of acute allergic reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009, 124, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma JP, Yauch RL, Kang HK, Lee HG, Kim BS. Preferential induction of IL-10 in APC correlates with a switch from Th1 to Th2 response following infection with a low pathogenic variant of Theiler’s virus. J. Immunol 2002, 168, 4221–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laouini D, Alenius H, Bryce P, Oettgen H, Tsitsikov E, Geha RS. IL-10 is critical for Th2 responses in a murine model of allergic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 2003, 112, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi N, Nagumo H, Agematsu K. IL-10 enhances B-cell IgE synthesis by promoting differentiation into plasma cells, a process that is inhibited by CD27/CD70 interaction. Clin Exp Immunol 2002, 129, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnonen J, Kainulainen L, Ruuskanen O, Nikoskelainen J, Arvilommi H. IL-4 synergizes with IL-10 and anti-CD40 MoAbs to induce B-cell differentiation in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Scand J Immunol 1997, 45, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uejima Y, Takahashi K, Komoriya K, Kurozumi S, and Ochs HD. Effect of interleukin-10 on anti-CD40- and interleukin-4-induced immunoglobulin E production by human lymphocytes. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol 1996, 110, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakae S, Komiyama Y, Yokoyama H, Nambu A, Umeda M, Iwase M, Homma I, Sudo K, Horai R, Asano M, Iwakura Y. IL-1 is required for allergen-specific Th2 cell activation and the development of airway hypersensitivity response. Int Immunol 2003, 15, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 1996, 87, 2095–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haelst Pisani C, JS Kovach JS, Kita H, Leiferman KM, Gleich GJ, Silver JE, Dennin R, Abrams JS. Administration of interleukin-2 (IL-2) results in increased plasma concentrations of IL-5 and eosinophilia in patients with cancer. Blood 1991, 78, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumchen K, Ulbricht H, Staden U, Dobberstein K, Beschorner J, de Oliveira LC, Shreffler WG, Sampson HA, Niggemann B, Wahn U, Beyer K. Oral peanut immunotherapy in children with peanut anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010, 126, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouro T, Takatsu K. IL-5- and eosinophil-mediated inflammation: from discovery to therapy. Int Immunol 2009, 2, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Bublin M, Breiteneder H. Cross-Reactivity of Peanut Allergens. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014, 14, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenfeld P, Docena GH, Añón MC, Fossati CA. Detection and identification of a soy protein component that cross-reacts with caseins from cow’s milk. Clin Exp Immunol 2002, 130, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu F-D. Cross-reactivity between aeroallergens and food allergens. World J Methodol 2015, 5, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansom DM, Manzotti CN, Zheng Y. What’s the difference between CD80 and CD86? Trends Immunol 2003, 24, 313–318.

- Casas R, Skarsvik S, Lindström A, Zetterström O, Duchén K. Impaired maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells from birch allergic individuals in association with birch-specific immune responses. Scand J Immunol 2007, 66, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubo M, Trinschek B, Kryczanowsky F, Tuettenberg A, Steinbrink K, Jonuleit H. Costimulatory Molecules on Immunogenic Versus Tolerogenic Human Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol 2013, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan P, Gärtner D, Soezeri O, Radbruch A, Schulze-Osthoff K, Brunner-Weinzierl MC. CD152 (CTLA-4) determines the unequal resistance of Th1 and Th2 Cells against activation-induced cell death by a mechanism requiring PI3 kinase function. J Exp Med 2004, 199, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica MA, Goenka S, Boothby M. IL-4-dependent induction of BCL-2 and BCL-X(L)IN activated T lymphocytes through a STAT6- and PI3-kinase-independent pathway. Cytokine 2000, 12, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. , Letai, A, Sarosiek, K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: the balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers SJ, Bertelli E, Winterbone MS, Regoli M, Man AL, Nicoletti C. Adoptive transfer of dendritic cells from allergic mice induces specific immunoglobulin E antibody in naïve recipients in absence of antigen challenge without altering the T helper 1/T helper 2 balance. Immunology. 2004, 112, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graninger WB, Steiner CW, Graninger MT, M Aringer M, Smolen JS. Cytokine regulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression in lymphocytes of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Death Differ 2000, 7, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berin MC, Sampson HA. Food allergy: an enigmatic epidemic. Trends Immunol 2013, 34, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudter J, Neurath MF. Apoptosis of T cells and the control of inflammatory bowel disease: therapeutic implications. Gut. 2007, 56, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).