1. Background on value chain selection

1.1. The Contextual Assessment:

The Gambia is among the poorest countries in the world, with overall poverty rate recorded at 48.65%1 using the less than USD1.25 per person per day, and 8 % of them considered food insecure2. The main features of the economy are its small size and narrow market; and is little diversified relying mainly on agriculture, tourism, re-export trade. The country has a small export base, with groundnuts, cashew and fish in its export market. The tourism sector has contributed approximately 16-20% of GDP in 2016, and has been the largest foreign exchange earner. Wholesale and retail trade was also a major sector of the economy (contributing about 25% of GDP)3, reflecting the importance of re-exports. The main drivers of growth are services (66% of GDP in 2016), and a volatile, drought-prone agriculture sector (21% of GDP in 2016)4. Remittances and international aid play an important role in sustaining the economy. Subsistence agriculture predominates; and groundnuts are the leading cash crop. The fisheries sector contributes about 2% to GDP; and the sector is important for food security and export earnings.

There is a rising rural poverty (from 64% 2010 to 70% in 2015); and a growing gap between rural and urban Gambia with regards to access to markets. The country was rated 47.3 on the Gini Index in 20135, indicating a high prevalence of income inequality6. While the proportion of households living below the poverty line is 31.6 per cent in urban areas, rural poverty is on the increase, as 60% of rural households living in poverty in 2003 have increased to 62.1% in 20107 and to 69% in 2016 (IHS report 2017). The rural areas accounts for 42.2 per cent of the country’s population, but they hold 60 per cent of its poor8.

Food insecurity disproportionately distresses households, affecting mainly those residing in rural areas. The last Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis (CFSVA)9revealed that food insecurity has increased in about 5.6% since 2011. Rural regions were found to have the highest number of food-insecure households in the country, ranging 12% to 18% of households. The number of smallholder farmers in The Gambia is estimated to comprise 43.1% of the population, and 22.6% of the economy10. Those in the rural regions lack suitable access and integration to (local) markets making them vulnerable to recurring shocks especially during lean seasons. With declining productivity over the years11, the country’s rural population faces higher prevalence of food poverty.

Though, the real GDP growth fluctuated substantially in recent years with declining trend through 1999 – 2018 period ending at 5.4% in 2018, higher than the recorded 4.6 % in 201712. IMF recorded the GDP per capita at US$705 in 2018, and the inflation rate of that year was at 8%. The Gambia is highly vulnerable to recurrent droughts, floods and other climate change related risks. Agriculture is typically contributing up to 30 per cent of GDP, although this declined to 27 per cent in 2017 (GBoS 2017). Average agricultural production growth rate per annum was 2.5 per cent from 2007-2016 (way below the population growth rate of 3.1 per cent), with relatively wide yield gap across major crops. The sector employs 46.4% of the working population and 80.7 per cent of the rural working population (IHS 2015/2016).

Agro-industries constitute 15 per cent of GDP, which is a significant component of Gambia’s industries and another growth driver. Groundnuts are the main source of foreign exchange for The Gambia, accounting for 30 per cent, and meeting 50 per cent of the national food requirement (CCA 2015). Agriculture has a key role in helping achieve Government’s objectives for economic growth and development. Promoting growth and employment in The Gambia must reflect development of the agriculture value chain.

1.2. Profile of The Gambia Agriculture Value Chain

A rapid review of literature and project documents provided some basic data on agriculture value chain in The Gambia. Agriculture is found as one of the main drivers of Gambia’s GDP growth, and source of livelihood for 72 per cent of the population. The sector is characterised by low commercialization as 62% of farm households produce for only self-consumption, 34% produce for both self-consumption and commercial sale, leaving only 4% of households producing purely for commercial sale13. There is limited value addition and there exist few formal private sector enterprises in agribusiness. Local agricultural products are largely marketed through informal channels, in contrast to organized large-scale imported products (e.g. rice)

Agriculture value chain development is a national priority, underscoring promotion of agri-business and agro processing; rebuilding and revitalizing the agricultural market infrastructure through cooperatives and commodity exchanges; quality assurance mechanism to strengthen access to export markets; increased production and productivity using sustainable land and water management practices to address hunger and food security needs; and promotion of climate smart agriculture to build rural resilience14.

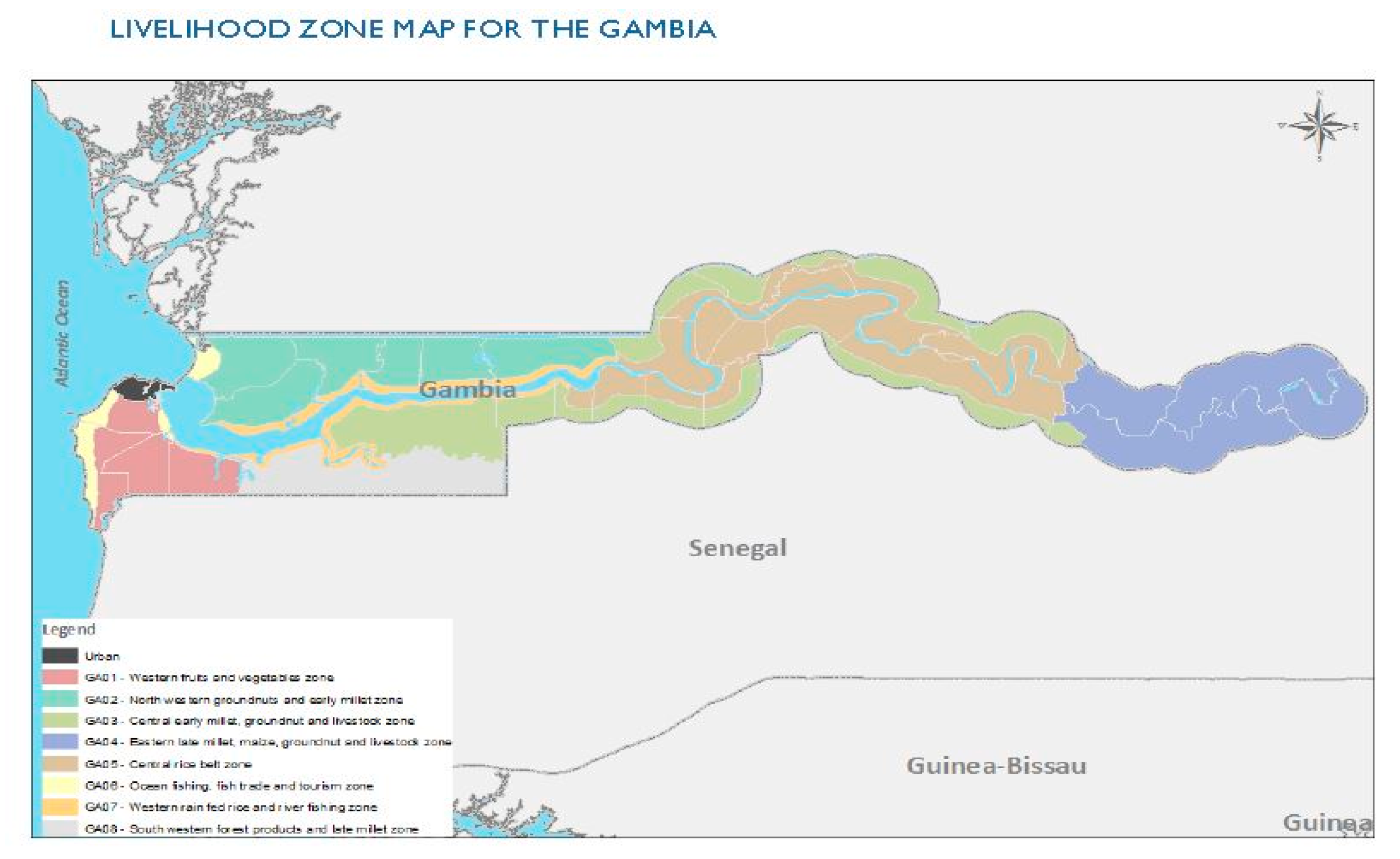

Gambia’s agriculture is relatively undiversified, mainly smallholder based and characterized by rain-fed subsistence crops. The main crops are groundnuts, rice, millet, maize and sorghum, as well as more intensive cultivation of vegetables and tropical fruits.Fruits and vegetable (primarily mangoes and tomatoes) production predominates in the Western Region of the Country, while groundnuts and early millet are the basis of the local economy in North Bank Region. Even though groundnuts is produced and livestock reared in all the regions, rice production takes centre stage in the Central Regions – Lower River and Central River Regions. Groundnuts, rice, maize, late millet, sorghum, cowpeas and some early millet constitute the local livelihoods of the eastern URR of The Gambia.

Figure 1.

Livelihood Zone Map of The Gambia.

Figure 1.

Livelihood Zone Map of The Gambia.

There are a number of limitations in the agriculture value chain including low productivity and marketing constraints that are worsening household purchasing powers. Some of these challenges include use of traditional low input/output production practices; inadequate incomes of smallholder producers due to low competitiveness of locally produced major agro-commodities with cheaper imports; and essential inputs are relatively expensive, and not easily affordable by majority of resource-poor smallholder producers.

The sector is indeed constrained by a host of factors such as adverse climatic conditions, overdependence on foreign aids (for instance food, fertilizer, human capital, etc.), poor extension services, declining soil fertility, poor land and water resource management, increasing global commodity prices, inadequate implementation of domestic policies, and limited access to financial services to promote the value chain functions: production, aggregation, processing and marketing. Fertilizer subsidy program exists but appears ineffective in reaching a majority of farmers

Weak capacity of producer organizations, under-performing support institutions that deliver essential services of extension and finance (credit), and limited access to market information; poor rural infrastructure (feeder roads) limiting access to markets are key barriers to agriculture value chain development. Generally, Gambia’s agriculture value chain is of limited economies of scale to encourage and attract investment in the various function, especially in mechanized farming that would increase productivity and expand production areas. Other causes of low performance of the value chain are unfavourable macro-fiscal stance in recent years, weak policy implementation and institutional framework, rainfall variability and climate shocks, lack of transport and market infrastructure, inappropriate storage facilities for major agro-commodities, high levels of aflatoxin contamination in groundnuts, low levels of application of food safety management systems along the value chains, as well as poor adherence to Sanitary and Phyto–Sanitary (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) standards of export markets.

The transformation from a predominantly subsistence to a commercial and diversified agriculture sector will significantly contribute to Gambia’s economic growth. However, low and unpredictable level of agricultural output induces price volatility that negatively affects the agricultural markets, and creates production and price risks that are unfavourable for increased investment. Value chains of rice and livestock are supply-base with limited market orientation. To commercialize the commodities requires improvements in post-harvest practices, processing with value additions and meeting quality standards; improving and expanding market chain linkages and trade opportunities; as well as strengthening and promoting linkages among key institutions and actors along the value chains of the two commodities.

There are limited industrial processing facilities for major crops in The Gambia, except the groundnut mill at Denton Bridge, which attracted some private investment to processfor oil extraction. NGOs and some international development partners patronized local communities with cereal (rice, millet and maize) milling facilities through their mainstreamed gender programmes. The only industrial rice milling facility that was set up at Kuntaur is no longer operating. A large tomato processor is established at Banjulinding, but using imported tomato and recipe. Industrial fishing is declining, but artisanal fisheries is thriving and supplying a number of exporting fish processing facilities. There is one organized abattoirs in Abuko; and there exist only one medium-sized milk processor with a capacity of 500 liters / hr. The growing cashews exports overtaking groundnut exports in the recent past, are exported 100% in raw forms; as there is no processing facility for this commodity.

Transportation of agricultural goods is an essential function of the agriculture value chain. Generally, the trunk roads in The Gambia are good conditions, albeit feeder roads are in poor shapes adversely affecting farmers’ access to inputs and markets. The main road network (800 km, 80% paved) is well maintained, but the secondary/feeder road network (~2,500km) is under-funded and poorly managed, and are in “poor condition”15. High rural-urban migration is constraining labour availability for agriculture, leaving farm work for the aging populations.

Inadequate capital investment in agriculture constrained commercialization of the sector. Availability and cost of finance are extremely high due to financial institutions high interest rates. Such short term interest rates with high collateral requirements have been limiting availability of finance for private investment in the productive sectors. Also, financial institutions claimed lack of understanding of needs and risks associated with agriculture financing; and there exist no organized non-banking finance companies with network and capacity to undertake agriculture lending

Trade in The Gambia has been facing challenges of the market size, effective local demand, fluctuating commodity prices, and an undiversified product and export base. However, there are huge potentials for agricultural trade growth with country’s unique geographical location at the mouth of many navigable river in West Africa, which accorded it a vibrant entrepôt trade. Banjul port is small compared to larger peers (particularly Dakar) but perceived to be more efficient. While liberal trade policies and duty arbitrage attracted neighbouring countries to patronize Gambia’s re-export trade, the ECOWAS CET eliminated that opportunity. Nonetheless, The Gambia’s location, good trunk road infrastructure and inland waterways is still providing natural advantages for trade with neighbouring countries in the sub-region.

1.3. Value chain selection

Based on the conclusions of the above agriculture value chain assessment, the following nine commodities were selected for further value chain analysis:

Rice was selected based on its critical role as one of the main staple foods in the country with huge potential for import substitution. Although rice is the staple food of all Gambians, domestic production was only 19 per cent of country’s needs (IHS 2015/16). Therefore, rice imports accounts for half of all food importations. Over the years, CIF value of the commodity has increased from D84 million in 1994 to about D1.923 billion in 2014. Rice imports were $35m/year (almost 4% of GDP), representing a large opportunity for import substitution. In 2017, about 215,000 tons of rice was consumed in the country but only 40,000 tons were produced locally, thus USD74 million was spent on importation of rice16. The growing food import bill has direct impact on the economy. The main constraints limiting the potentials of rice smallholder farmers to increase production and productivity is the difficulty of access to developed irrigation perimeters, land preparation, post-harvest handling, investment finance and marketing. The absence of strong rice grower’s organizations also poses a challenge for the development of rice17.

Groundnut was selected given its widespread and traditional prevalence as a cash crop and the potential to regain waning competitiveness. Groundnuts in The Gambia contributes 7% of the GDP18 employing over 150,000 farmers realizing a total production of 109,780 MT in 201719. Groundnut production is found competitiveness at current prices, even accounting for the lower export prices currently obtained for The Gambia’s poorer quality (high aflatoxin) nuts, used for oil processing (China) and feed (India). However, higher revenues from groundnuts could be possible via quality aflatoxin-free edible nut production, and if higher quality seeds are available. Increasing private investment will suggest a major structural reforms to improve incentives and enable price differentiation in the groundnuts industry.

Exports of fresh Gambian nuts to European markets are grossly limited by the high contamination of aflatoxin. Majority of the nuts are exported at much lower prices to China for processing oil or to India for bird feed, missing the higher-value opportunity offered by EU and US markets. The competitiveness of local processing for oil remains challenging, given high financing, input costs and lack of market-based pricing. Government control of farm-gate prices for groundnuts (being a political commodity) can be misconstrued by the private sector, and this undermines their participation and investment in the sector.

Horticulture (mango and tomato) were selected for analysis as potential export crops, considering their performances in the export markets, and benefits accruing to certain firms. Mango is the largest single fruit in The Gambia, with estimates of annual production varying widely from 1,500 (FAO) to 8,000MT for exports alone (GoTG, 2018); with 40% of the produce being currently commercialized20. Gambian mango is a six-month seasonal crop of different varieties, with some important competitive advantages: a) being able to harvest over range of half year, and b) having production peak from May-July, after seasons of some major producing countries.

Millet and Maize were selected because of their critical roles in traditional household food and nutrition security among Gambian families, with huge potentials for food import substitution. Both commodities are drought resistant with great potentials to increase, on a sustainable basis, the income of rural producers, entrepreneurs (actors) that are engaged in the production, processing, storage and marketing.

Livestock (ruminants and chicken) were selected for wealth and employment creation. Activities of the various livestock value chains - production (of ruminants and poultry), processing, marketing and services - provide diversified livelihood opportunities to rural, peri-urban and urban inhabitants. Livestock contributes 5 - 7 % of national GDP and 20 - 25% of agricultural GDP with majority of farmers being smallholder farmers21. The milk value chain is dominated by small scale farmers practicing integrated crop/livestock production. The present domestic production of beef, milk, lamb, meat and chicken is far short of national demand. The deficit in supply is supplemented with imports. The demand for livestock products throughout the year offers an opportunity to generate income by increasing the quantity marketed.

1.4. Target audience of the report

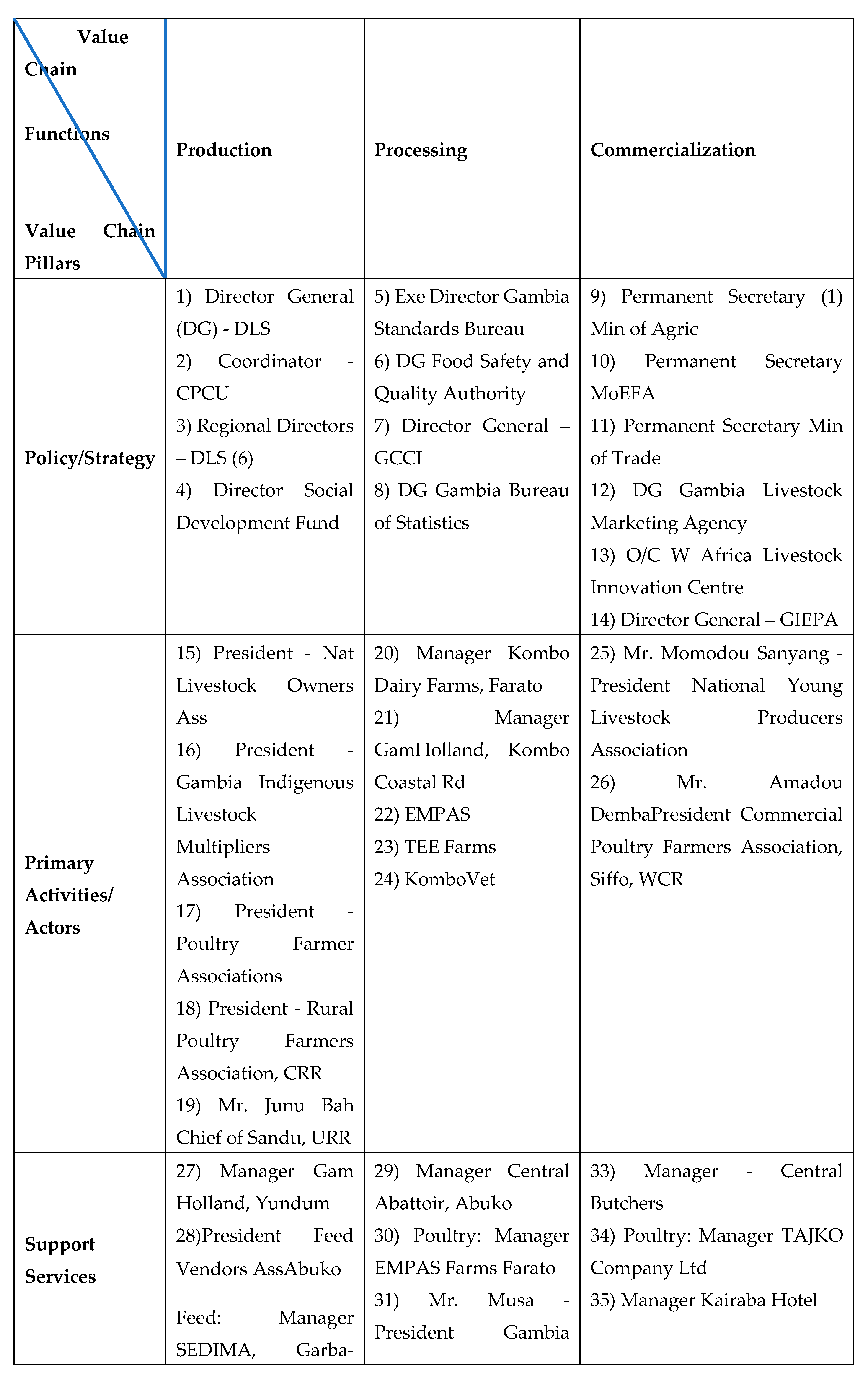

The Government of The Gambia, its agri-business community, and the private sector are the target audience of this report. Key stakeholders are at all levels of the value chain: 1) policy and strategy (for creating the enabling environment); 2) core value chain actors, their cooperatives/associations and governance structures (from production to consumption); and 3) support services (input dealers, financial institutions, and the transport union). Key audience at policy and strategy level are the Permanent Secretaries of Ministries of Trade, Finance and Agriculture, while their technical departments and relevant state institutions (e.g. GIEPA, GCCA, Standard Bureau, Food Safety and Quality Authority, etc.) shall be mandated to implement the strategic recommendations. The external audience targets are development partners, International Institutions and Aid Agencies in supporting value chain development efforts in The Gambia.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sources of data and validation

This value chain analysis used a combination of methods to capture both quantitative and qualitative information. Desk research - review of multiple literatures, followed by field data collection –stakeholder consultations, formal interviews with focus groups of actors at various stages of the value chain using a structured questionnaire, and comprehensive analysis of value chain functions was employed in the study. Qualitative methods – semi-structured key informant interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) – was used to provide quality information. In this way, the two categories of methods were complementary and mutually reinforcing.

2.2. Desk research:

Extensive review of relevant FAO internal documents (including the project documents), current sector strategies, National Strategy documents, literature of major development sectors, and key documentations on the target agro-commodities was conducted to produce a draft report on the commodity. The study team review other relevant publications from the project partners: food industries, WFP, FAOSAT, World Bank and WTO Gambia Trade Policy Review, and Government line ministries (such as Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Trade, Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, etc.) and agencies (including GIEPA, NaNA, Food Safety Agency, NARI, DOA, DLS and Fisheries among others) in order to incorporate their perspectives and expectations. Other secondary sources include documents from national and international stakeholders, such as Gambia Groundnut Council, Livestock Marketing Agency, and women’s groups in vegetable production, NACOFAG, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), & multilateral organizations. The consultants also, review those published and unpublished literature on topics related to the selected agro-commodities in The Gambia, e.g. NGO publications, journal articles, magazine, and conference and seminar papers.

b) Stakeholder consultations:

Delving down on information from the desk research, the team verified different roles of stakeholders and actors in the value chain of the commodity. Stakeholder consultations with private farms and enterprises of individual commodities was conducted to generate relevant data from input supply to marketing/consumption levels. The Consultants also, engaged key informants in partner Government Ministries: Agriculture, Trade and Employment, Finance and Economic Affairs to collect basic information on i) institutional frameworks relating to marketing of the commodity, financial and extension services, etc.; and ii) information on the impacts of policy and regulatory frameworks on the value chain of the commodity; options and viability of processing enterprises; and private sector investment were assessed.

c) Field data collection using three techniques:

i)Focus Group Discussion “FGD” with value chain actors at different stages along the value chain: input suppliers, primary producers/herders, processors, marketing agents, customers/consumers, private business operators on the product were conducted to generate relevant qualitative data on the commodity. Semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted to triangulate quality data collected from FDGs. An illustrative interview guide (with research questions) for each stage of the value chain was provided.

ii) Formal interviews with a sample of actors at different stages along the value chain of the commodity was conducted using a structured questionnaire. To select respondents, simple random sampling method was used in the 6 regions and Greater Banjul Area (GBA), the objective of which was to collect information from representative actors along the value chain of the commodity in purposively selected sample entities/locations. Sample of respondents were drawn from a cap in each location for all the functions, except for policy and strategy which was targeting official stakeholders. Tablets were programmed with the questionnaire using the Open Data Kit (ODK) which was used for data collection.

iii) Market and profit margin analysis: Informal interviews were conducted with actors in the commodity market including retailers, wholesalers, transporters, customers, etc. to assess the pricing system, market linkages and customer satisfaction on the commodity.

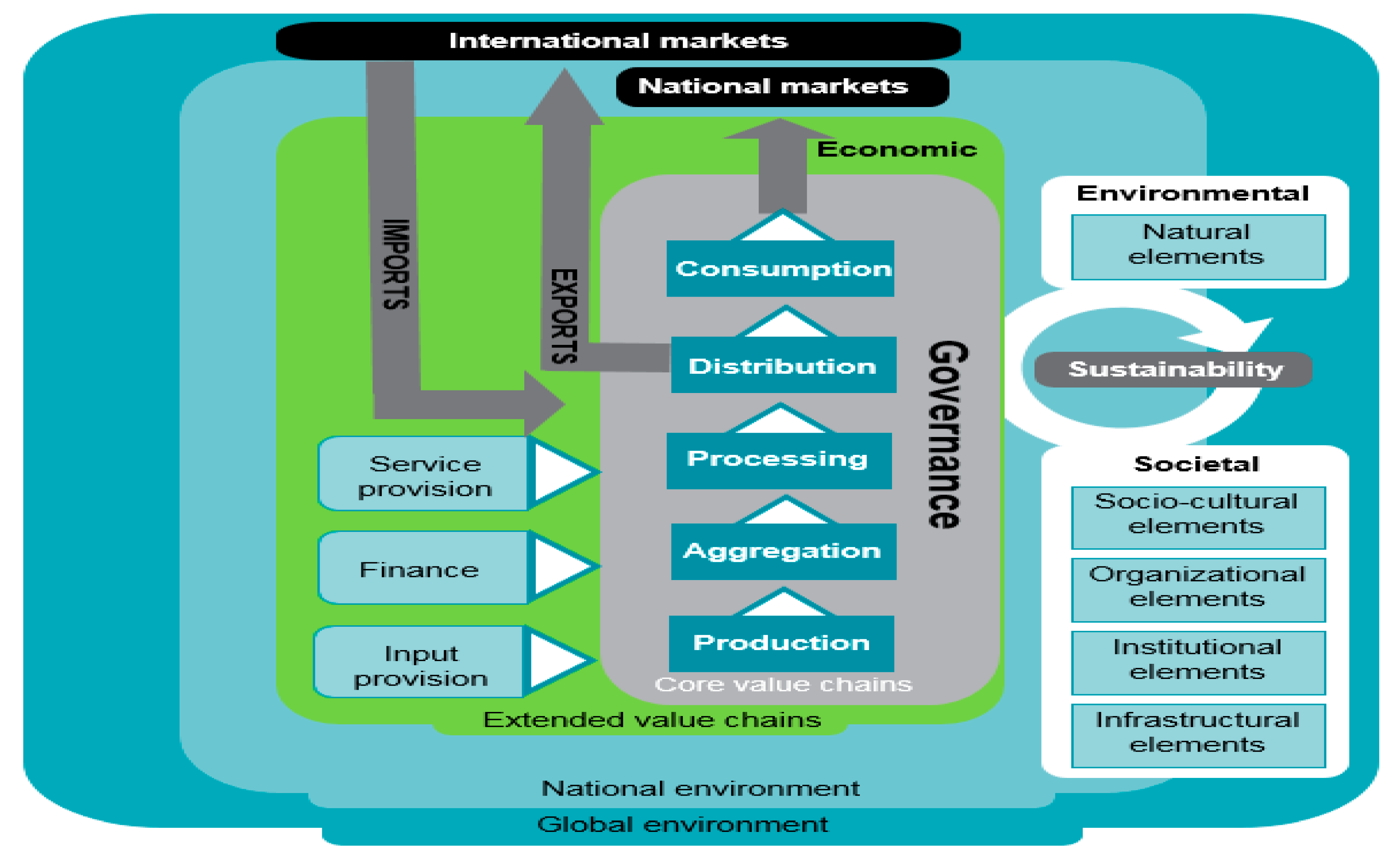

2.3. Conceptual framework: Sustainable Food Value Chain framework, Decent Rural Employment concept

This value chain analysis employed FAO’s analytical framework for Sustainable Food Value Chain Development (SFVC) approach offering a broader understanding of key drivers influencing value chain actors, its inter-linkages and interconnected activities to make value addition by transforming raw agricultural produce to final consumers in a holistic way to address the sustainability of the food systems. With the SFVC approach, this identified the root causes why value chain actors are not able to take advantage of the opportunities presented by the end markets.

Therefore, the VCA process underscored the assessment of economic, social and environmental outcomes (measuring performance); and undertook performance appraisal of the value chain actors to see how the actors and their activities are interlinked and coordinated (understanding performance), and how value added is distributed, while engaging relevant stakeholders to build consensus on upgrading strategy of the value chain (improving performance).

Figure 2.

FAO's Conceptual Framework for Value Chain Analysis.

Figure 2.

FAO's Conceptual Framework for Value Chain Analysis.

3. Chicken Value Chain Analysis

3.1. Introduction

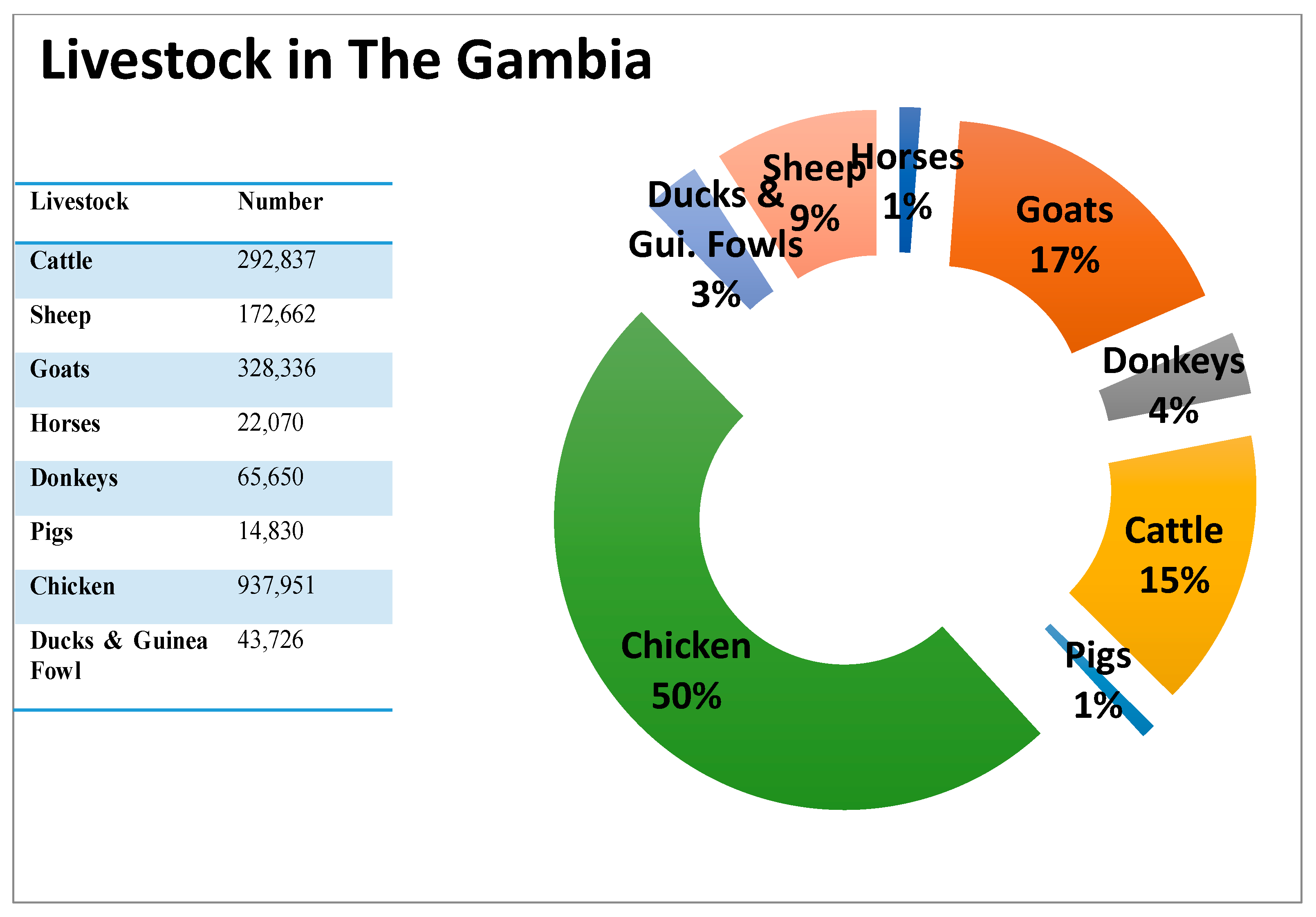

Livestock production is estimated to contribute to 5-7% of the Gambia’s GDP and up to 16 - 20% of Agricultural GDP. Livestock is held in most instances as savings or as a risk management option (ActionAid and Oxfam 2004, Sanyang et al 2017). The livestock produced in The Gambia are Cattle, Small Ruminants, Pigs, Horses and Donkeys, Chicken and other poultry.

Figure 3.

Livestock Population in The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services, 2016.

Figure 3.

Livestock Population in The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services, 2016.

The Chicken value chain in The Gambia has witnessed significant interest in the past years. Apart from Fish, Chicken provides the cheapest source of protein in the Gambia. Over the past three years, most intervention aiming to address youth irregular migration within and from The Gambia has targeted the chicken value chain. This is based on its potentials for the creation of employment especially for young people.

With a better understanding of the actors, their activities, linkages, constraints and opportunities for value generation, such interventions may be better targeted and impactful. This is the value add that this value chain analysis seeks to contribute.

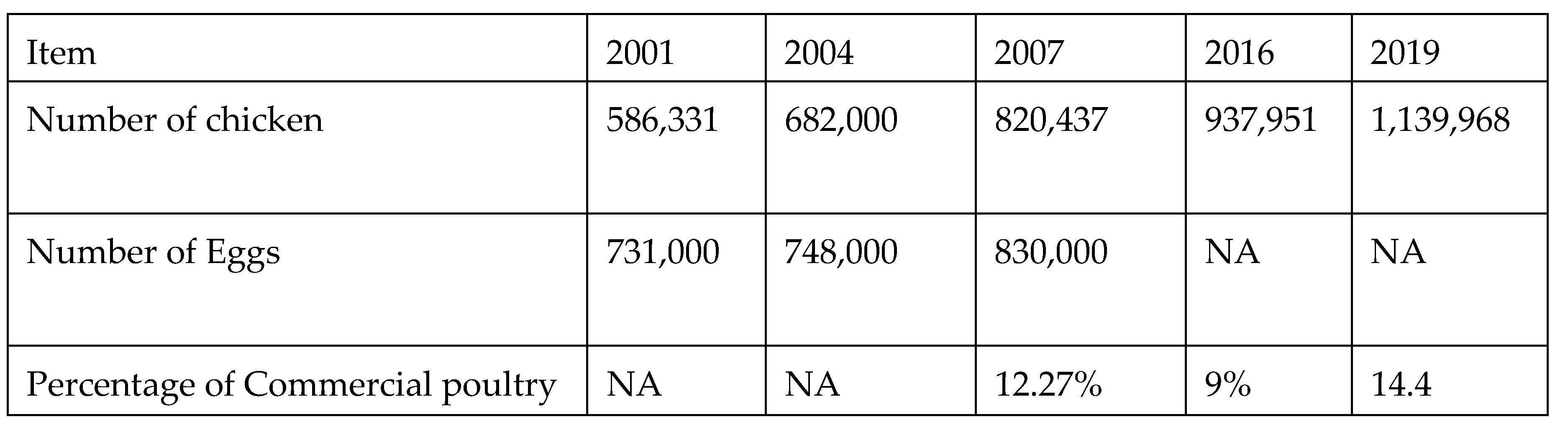

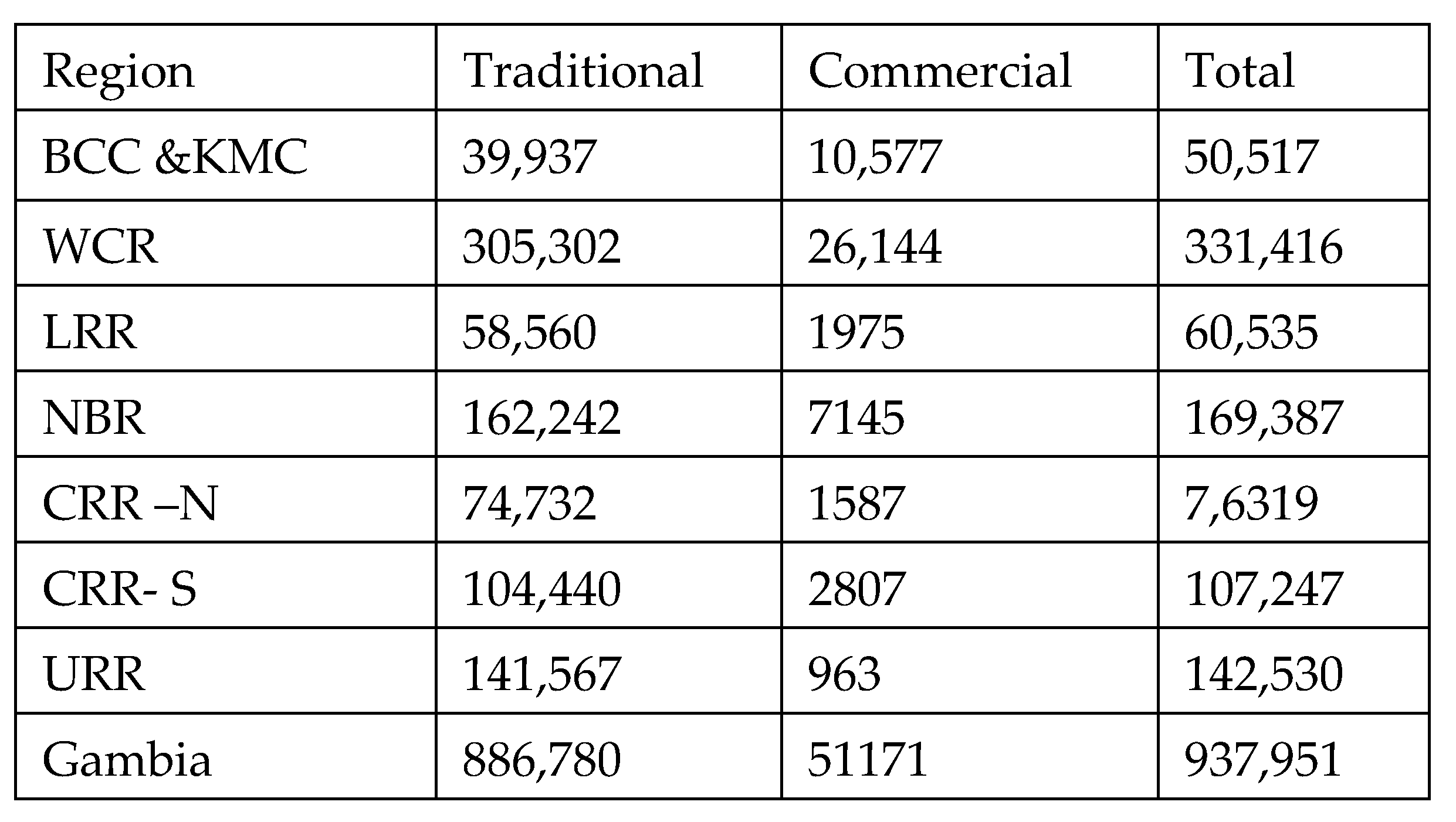

The 2016 National Livestock Census estimates the population of chicken in The Gambia to about 937,951 chickens. Compared to the 2001/2002 estimated figure of 586,331, this represents a 60% increase (National Agricultural Census). The table below show the trend in the number of chicken and eggs produced in The Gambia.

Figure 4.

Chicken Production Trends In The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2016.

Figure 4.

Chicken Production Trends In The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2016.

Up to 90% of the chicken population is produced through traditional means in rural and peri-urban areas and about 10% is produced by commercial poultry producers, normally in urban areas and rural growth centres. In tradition system local chicken are left to roam and scavenge around for food. Marketing is conducted within the village or in lumos. The purpose for traditional production is for family consumption, for savings or for sale during lean periods when food is scare or during emergencies. Key constraints encountered with this system include high mortality, lack of feed and day-old-chicks. Commercial poultry production is predominantly in peri-urban and urban areas and rural growth centres in the country.

More than 44% of households and 60% of rural households in The Gambia raise chicken. Women raise more than 60% of the chicken produce in the Gambia. However, the number of women in commercial poultry production is low, estimated to be less than 2%.

Between 35 - 38% of the chicken is produced in West Coast Region of The Gambia. The concentration of commercial chickens in the West Coast Region and Greater Banjul Area is in response to the high demand for poultry products in these regions accounting for more than 51% of the human population, having a relatively higher per capita income, and home to major hotels, guest houses and restaurants in The Gambia (FAO 2008).

Local production of chicken products (eggs and chicken) is below 10% of domestic demand. GIEPA 2012 estimates that 200,000 eggs are consumed daily in The Gambia, of which only 9% is produced locally. The market is flooded with imported cheap broiler/eggs mainly from Brazil, Holland and the Middle East. Over the years, the volumes of imports have increased to cater for increasing consumer population and demand for chicken in The Gambia.

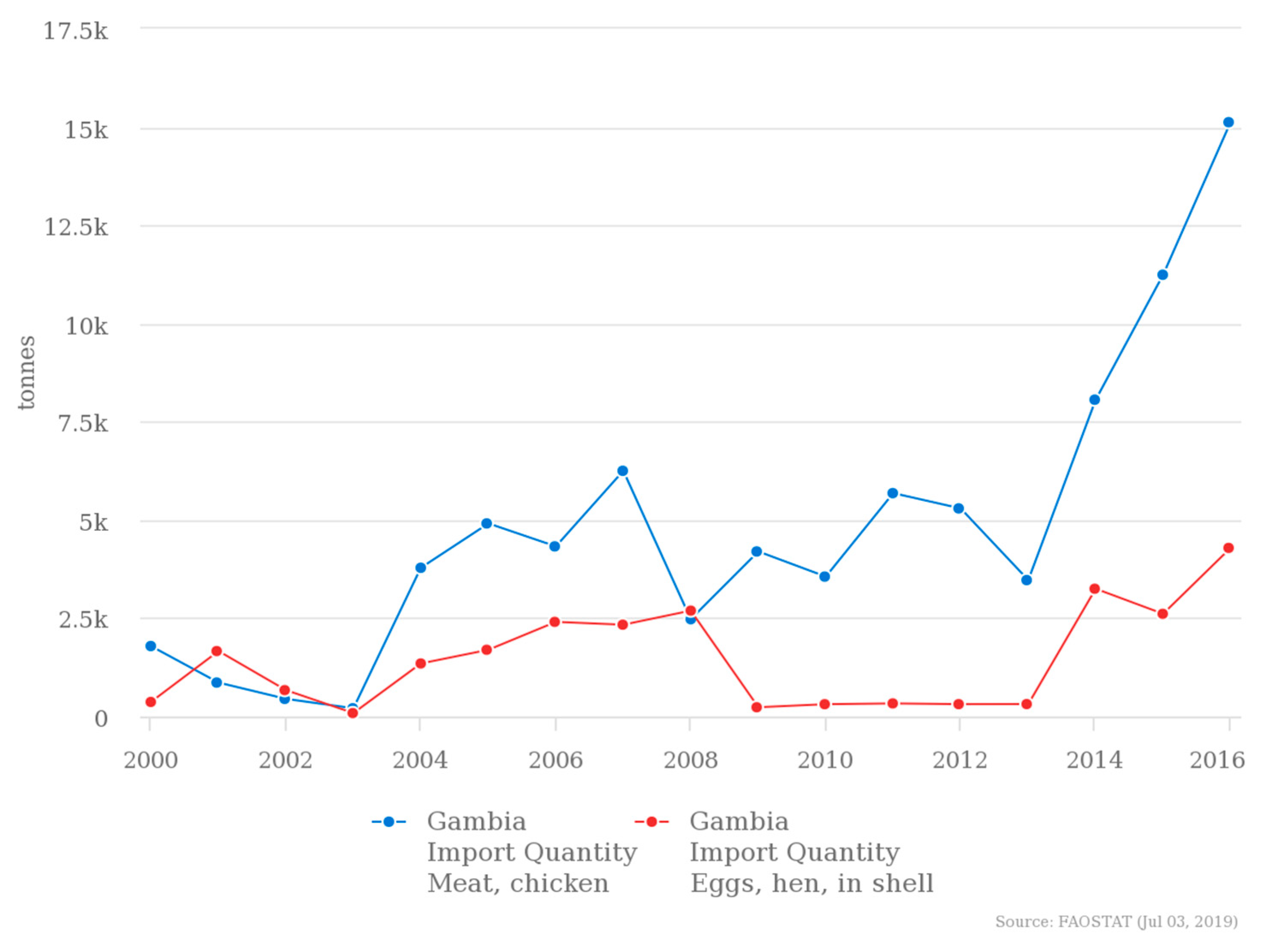

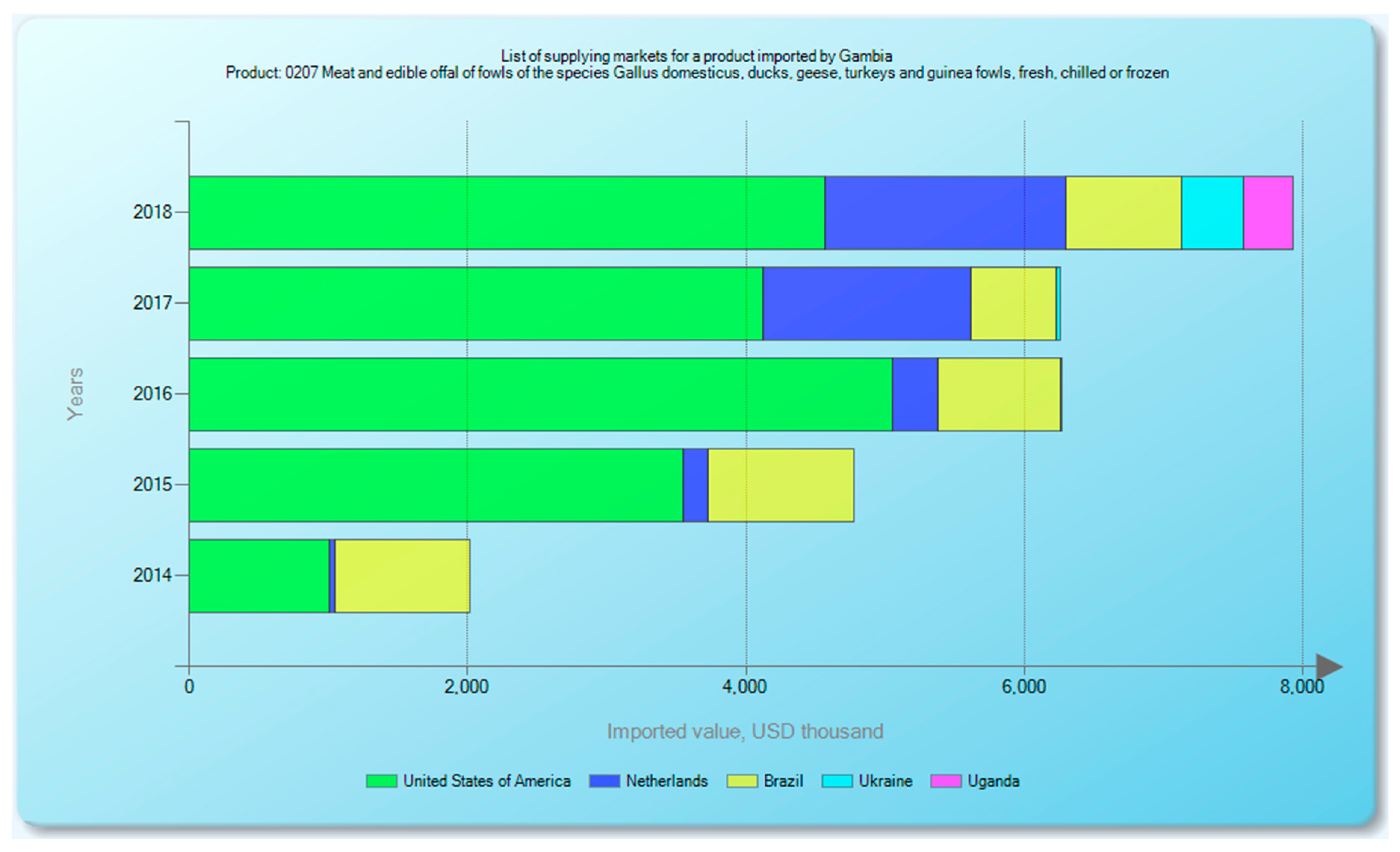

Figure 5.

Chicken and Egg Imports to The Gambia (.

Figure 5.

Chicken and Egg Imports to The Gambia (.

The local producers do not have the capacity to compete with imported poultry products. In addition, the industry lacks key inputs such as skilled expertise in relevant areas of the value chain, domestic supply of parent stock, hatcheries, day-old chicks as well as the absence of feed mills.

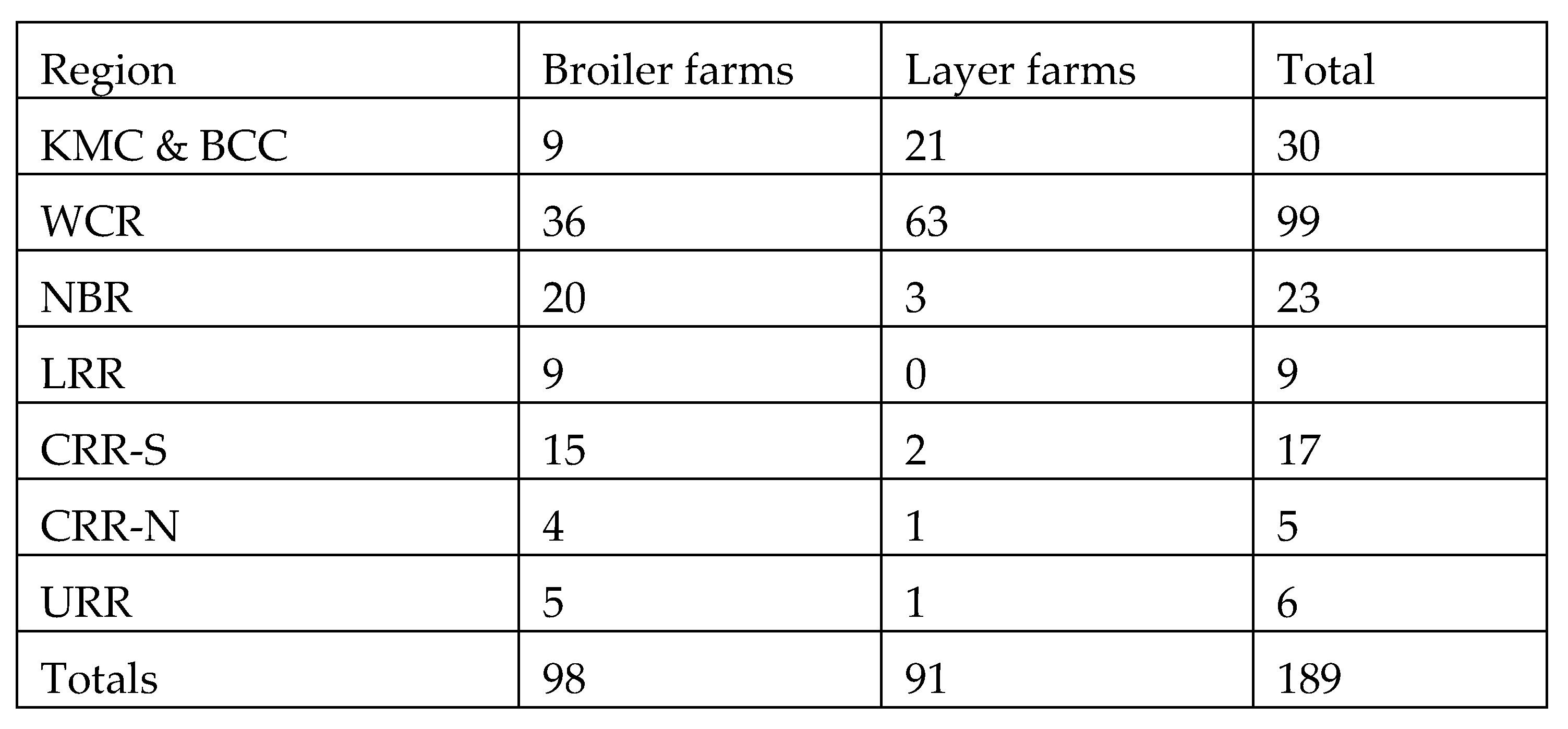

The 2016 Livestock Census reported 71 broiler farms and 42 layer farms across the eight regions of The Gambia. 37% of broiler farms and more than 70% of layer farms are located in West Coast Region and Greater Banjul Area. However, the scenarios have changed significantly with more than 81 commercial chicken producers and community-based organisations in poultry production across the country entering the chicken market. In the past three – five years, most of these farmers and groups are supported by projects including FASDEP, FAO, AVCDP, NEMA and the EU funded Teki-fii (make it in Gambia) projects implemented by different agencies in the Gambia.

Figure 6.

Commercial Chicken Production In The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2014 and Authors own estimates from data provided by feed importers/producers.

Figure 6.

Commercial Chicken Production In The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2014 and Authors own estimates from data provided by feed importers/producers.

An assessment of the poultry farms in The Gambia conducted by the Department of Livestock Services in 2014 show that most of the farms are operating below capacity with tilizedon for broiler farms estimated at 31.9% whilst 51% tilizedon is estimated for layers (DLS 2016).

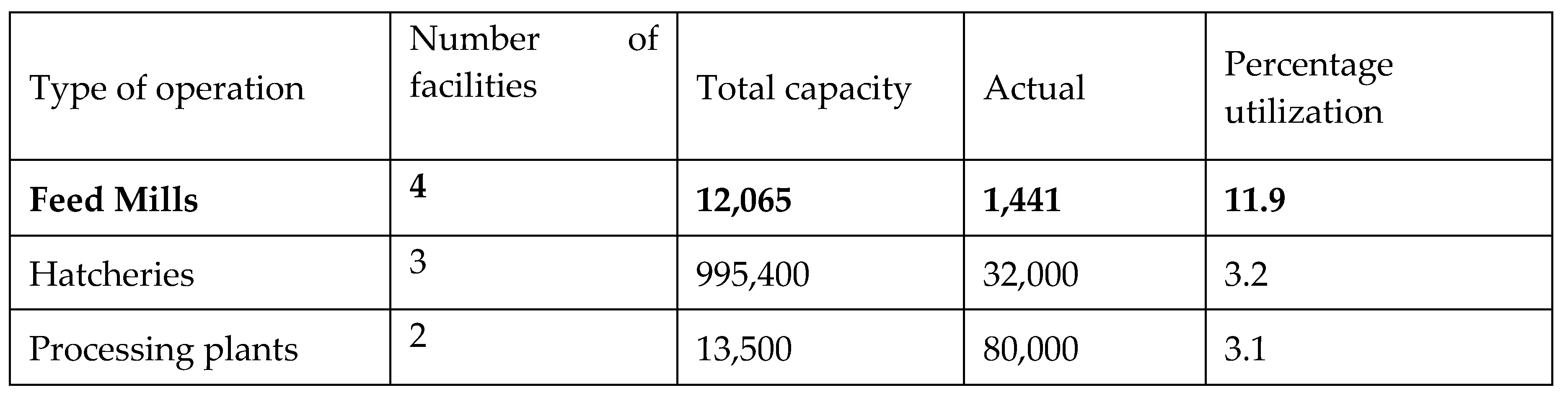

The numbers of years poultry farmers in the Gambia stay in business is very short. It is estimated that 44% close their businesses three years into production or significantly reduce production (FAO 2008, ActionAid and Oxfam 2004). For example, In 2016, the number of feed mills was estimated to be four, with three hatcheries and two processing plants. In 2019, none of these feed mills are operational. In 2019, our count shows that there is only one feed mill (GamHolland Enterprise) currently operating in The Gambia. Despite the fact that the mill has the capacity to produce more than 80% of the feed demand for the national poultry industry, it is still underutilized and lack functional laboratories for feed analysis (DLS 2014).

CENELAA which use to produce 51% of the total feed produced and the government owned Gambia Food and Feed Industry (GFFI) are no more operational.

Feed imports account for 60% of the feed use in the chicken value chain in The Gambia. The main importers include Kombo Poultry farm, Dam Jah, PRODAS etc which import mainly from Senegal. The major constraint to the production of feed in The Gambia is the high cost of imported feed input such as maize bran. Currently the maize bran when imported cost D16/kg whilst if bought in The Gambia, this can reduce up to D10 – D8/kg. Therefore it is estimated that investments in the production of maize bran in The Gambia can reduce the price of locally produced chicken by 14 – 18%

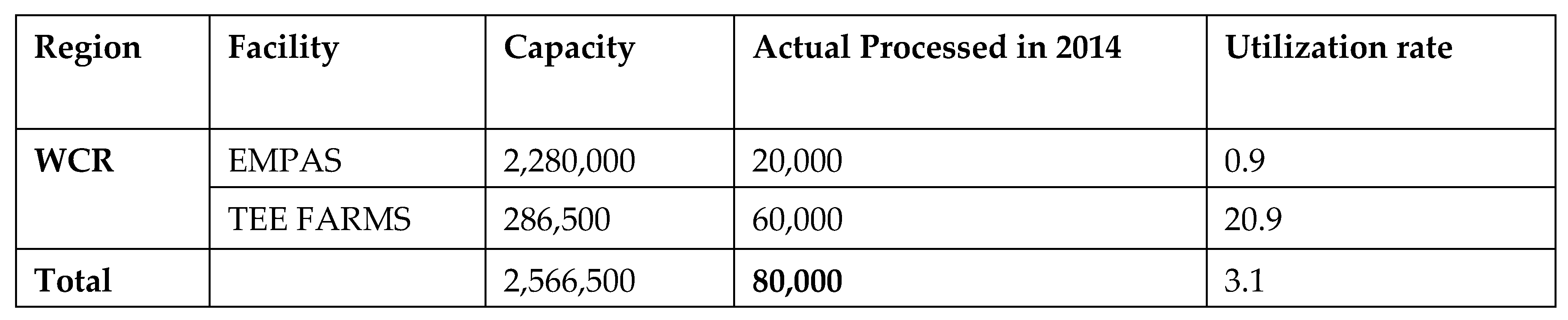

The hatcheries and processing plants are operating below 3% of capacity. As showed in the table below presenting facilities assessed and their production records. There are currently three hatcheries in the Gambia operated by EMPAS, Tee Farms and Kombo Poultry. In 2014, the National Census estimated that these are only tilized to only 3.2%.

Figure 7.

Infrastructure for Chicken Production and Processing. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2016.

Figure 7.

Infrastructure for Chicken Production and Processing. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2016.

The low utilization of hatcheries is caused by unavailability of parent stock in the Gambia. The current national demand for hatchery services is significantly lower than what can be produced by the hatcheries. It is important to note however that the low demand in hatchery services is mainly influenced by the low demand on local poultry products in The Gambia. Day-old chicks for the commercial sector were mainly imported from Europe, but currently most of the chicks are imported from Senegal. The chicks are transported by road (FAO 2008)

The players in the Veterinary services provision in the Gambia are mainly private operators. They include: AGROVET, SUMAVET, GAMVET, KOMBO VET, SAMIVET and VETSAN. These are concentrated around the KMC and WCR with branches or substations up country. The Department of Livestock Services provides extension services and manages responses to major diseases outbreak. However, the department is still poorly resourced and not in every district of the Gambia. For example, in the Sandu District of the Upper River Region of The Gambia, farmers reported no staff of the Directorate posted in the district.

3.2. End markets

There is an increasing demand for poultry products in The Gambia due to increase population, ommercializ and growth in nominal incomes. In 1992, only 22% of the Gambian population lived in the Urban areas, compared to 57% estimated in 2018 (GboS 2018, Jatta R 2010).

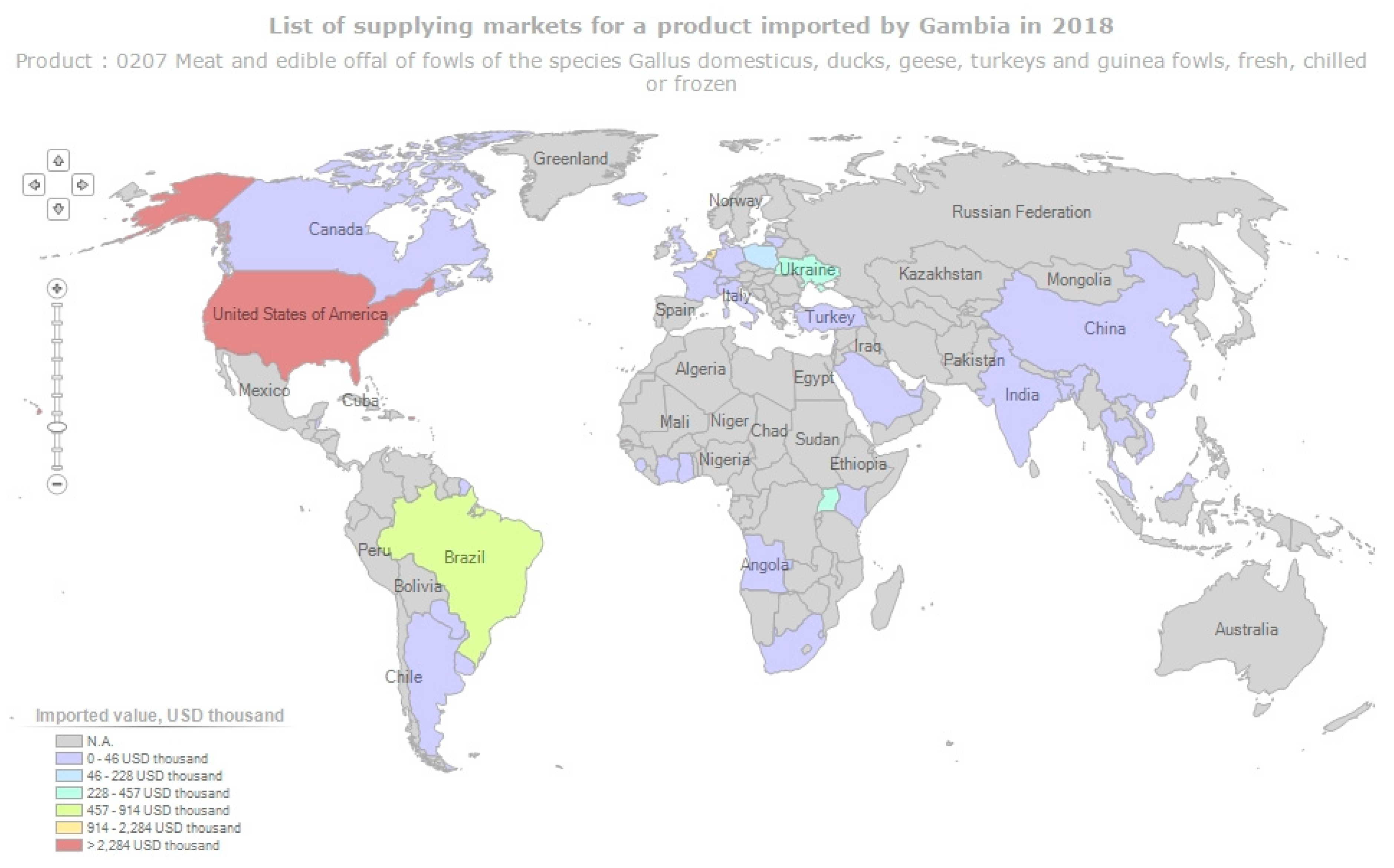

Only about 9% - 11% of the domestic demand is met by local production. The 2016 imports of poultry products shows that 15,504 MT of meat and 4,077 MT of eggs were imported (DLS 2016, FAOSTAT) mainly from Brazil, Holland, China etc.

Chicken imports represent the third highest commodity imports in the Gambia (based on value) only second to Rice and Oils. The Major importers are Supermarkets, Hotels and Restaurants. These include Tajco firms, Kariaba Shopping Centre, Chellarams, Alvehag and Marouns Supermarket. These firms are mainly owned by foreign investors in The Gambia or Gambians of Lebanese descent.

While the estimated price of imported chicken is about D90/kg, a Kg of locally produce chicken is estimated at D131.00. The major cost in production of chicken is feed (by 60% of the cost). The cost of maize is also estimated to be 60% of the cost of feed. Thus a clear under-utilised end market at production is maize bran. Currently much of the maize bran use for the production of feed in The Gambia is imported from Mali.

The price of imported whole chicken (of approximately 1.3kg – 1.5kg) has increased over the years from approximately D45 in 2004 to D190 in 2019. The same can be noted of the price of eggs. It was estimate that the price of egg was D4.35 in 2004 and now ranging between D8- D10 in 2019 (ActionAid and Oxfam 2004).

Processing of chicken and chicken products is very low in The Gambia. It is estimated that only 3% of Chicken in The Gambia is processed at least through the stages of slaughter, dressing, sorting and packaging. A potential emerging niche market is portioning and roasting. There is an increasing number of small scale operators in all lumos, peri-urban and urban markets in the Gambia who engage in portioning, roasting and selling of chicken portions. This provides a source of protein to consumers who cannot afford whole chicken or people whose households are single or very few. However, much of the chicken used in roadside roasting imported chicken.

Most of the farms prefer to sell life birds than engage in processing. The economics of processing for small scale firms show that when birds are sold life, they price higher than the dressed chicken. For example the farm gate price of dressed chicken is about D190, whilst whole chicken is sold at D225

Most of the industrial buyers (Hotel, Supermarkets, and Restaurants) also have a preference for life birds. This is because of the safety and hygiene status of the meat they need to sell to tourist, which is not often guaranteed by small scale commercial producers.

The sale of chicken products is seasonal. The tourist season (November – April) represent the peak market period whilst June – September is the period of lowest demand of poultry products. For example, GIEPA 2012, reported that the highest monthly importation of eggs was observed in October (270 MT) coinciding with the start of the winter tourist season and the least in August.

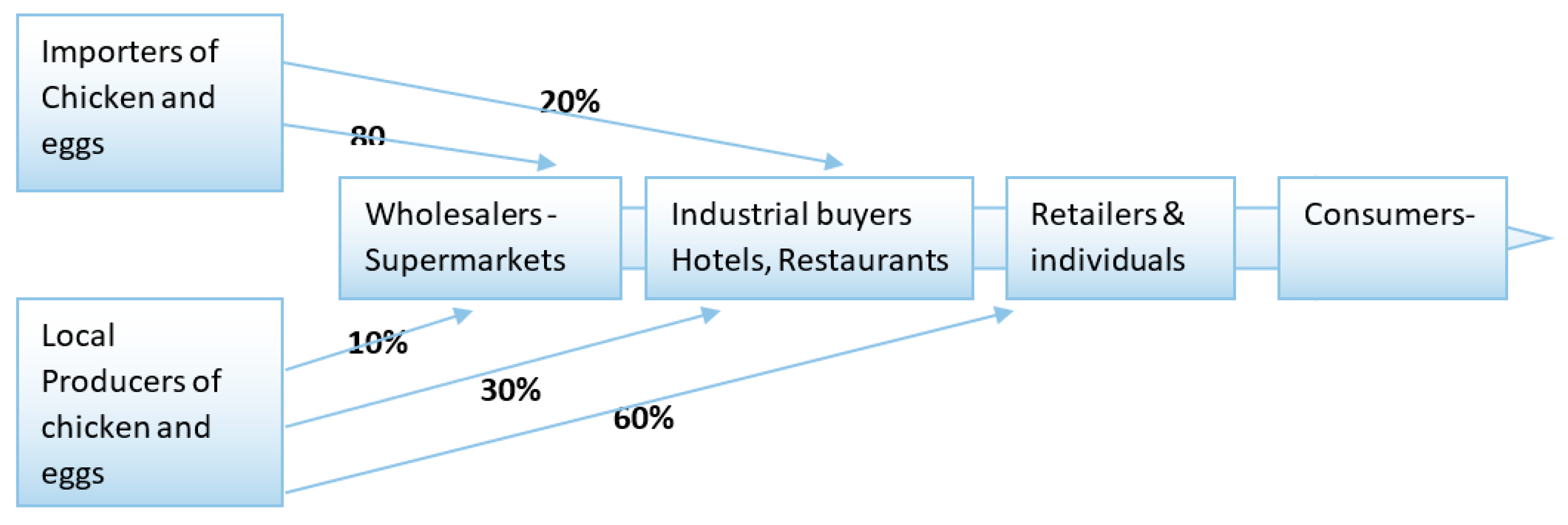

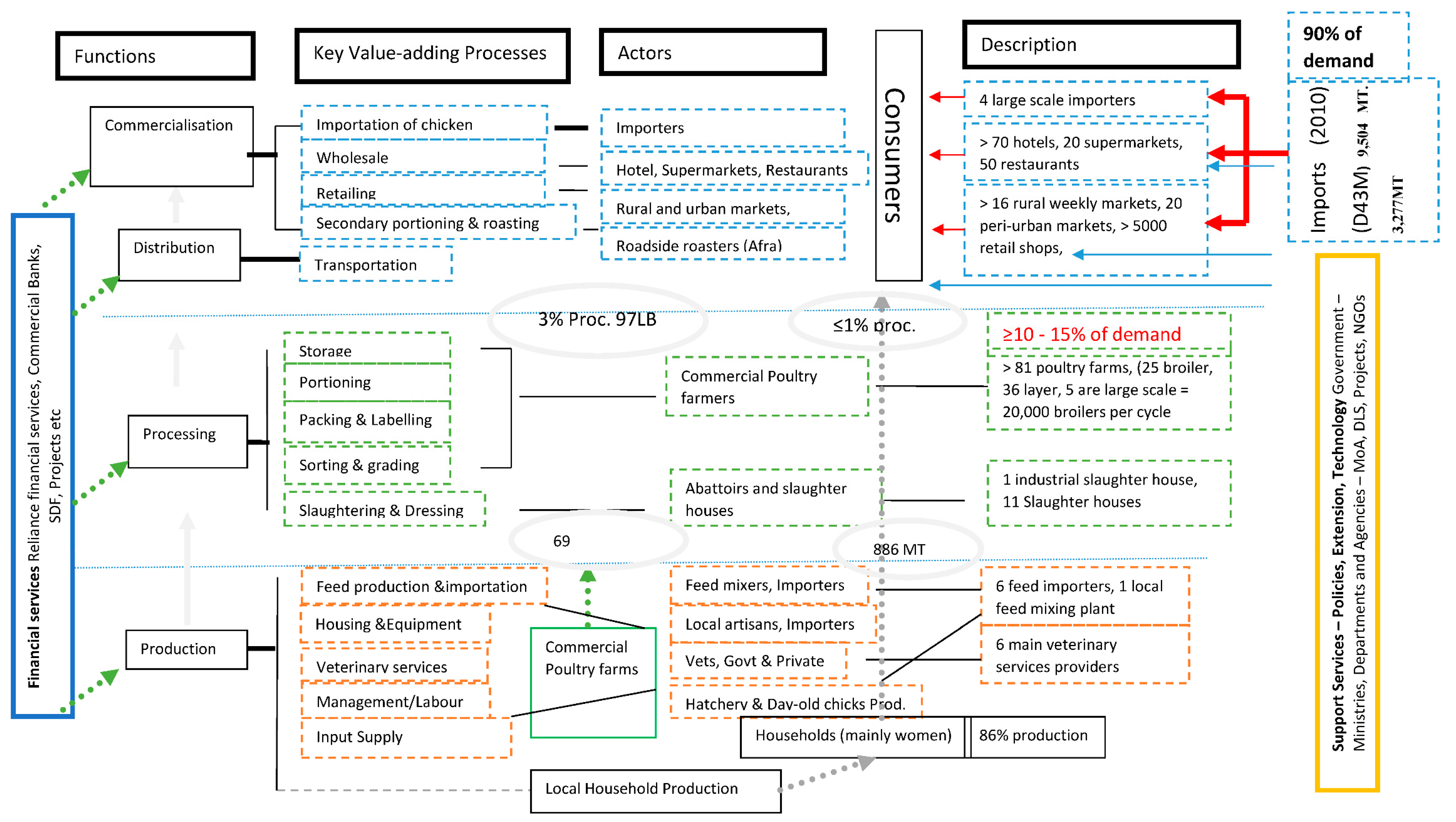

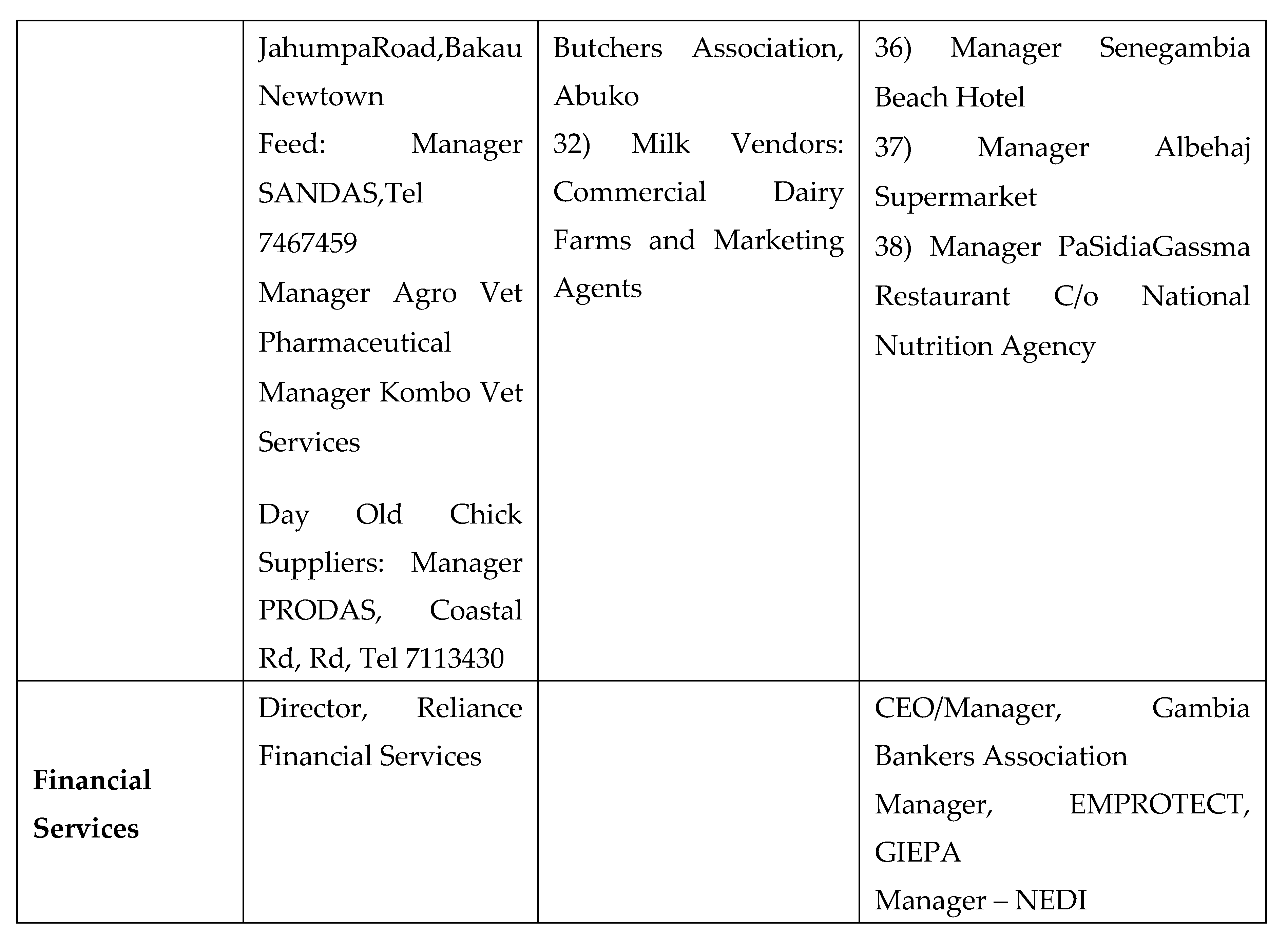

3.3. Value chain map

The Chicken Value chain map presents the value chain actors, their value-adding activities and their linkages. Chicken and chicken products that are sold for consumption in the Gambia are mainly life chicken, Whole chicken, chicken portions, offals and eggs. These are sold to individual consumers, retailers who engage in secondary portioning, roasting and selling and wholesalers mainly of hotels, restaurants, pastry shops, motels etc.

The key actors in the ommercialization of chicken and chicken products in The Gambia include:

- -

Importers of frozen chicken (whole and portions) and eggs. Most chicken import sources are from USA, Europe and Asia.

- -

Importers then supply wholesalers, mainly Supermarkets in large volumes of chicken and egg trays. More than 75% of imported chicken is channelled through supermarkets.

- -

Hotels, motels and restaurants are either supplied by importers directly. In a few instances (especially during the tourist off season, they buy from wholesalers

- -

These wholesalers then sell to retailers in smaller quantities of chicken and egg trays

- -

-

From domestic producers, chicken products (life birds, dressed chicken or eggs) are either sold directly to retailers (in villages, lumos or walk-in customers) or to supermarkets and hotels by producers.

- o

About 60% of chicken is sold to retailers and 40% to supermarkets and hotels.

- o

On the other hand, for eggs, more than 60% is sold to hotels, supermarkets and restaurants.

- -

Retailers collect eggs from producers and sell them to other small retail shops, kiosks and restaurants in urban centers and to domestic consumers. These are often in trays

- -

Individual buyers who buy from retailers, or hotels and restaurant for consumption (mainly during feasts and occasions) in trays and single eggs. In some instances, individual buyers also buy from producers, especially I communities where poultry farms are situated.

Figure 8.

Market Chain for Chicken and Eggs.

Figure 8.

Market Chain for Chicken and Eggs.

Between 55 – 60% of the chicken and eggs produced by local producers is sold to retailers at farm gate; sold as life birds and in trays of eggs.

In processing, the key value activities include slaughtering and dressing, sorting and packaging, portioning and storage. Only a limited percentage of the chicken produced in the Gambia is processed. More than 95% is sold as life birds.

Below is the value chain map showing the key function, value adding activities, the actors and the flow of production, processing and ommercialization.

3.4. Value chain geographic map

Figure 9.

Value Chain Geographic Map – The Gambia.

Figure 9.

Value Chain Geographic Map – The Gambia.

Chicken is produced in all the regions of The Gambia. The concentration is collated with access to markets and climate conditions (temperature). The West Coast Region has the highest concentration of chickens in The Gambia for both Commercial poultry as well as traditional back yard systems. The map above shows the density of chicken produced across the eight regions of the Gambia.

The table below presents a headcount of chicken conducted by the Department of Livestock Services in 2016 as part of the Livestock Census.

Figure 10.

Chicken Production across Regions of The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2016.

Figure 10.

Chicken Production across Regions of The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2016.

3.5. Core value chain functions

3.5.1. Production

The key inputs in the production of chicken are:

There are 3 hatcheries (EMPAS, Tee farms and Abuko Poultry Training Centre) with capacities of 142,200. Under full operation, each of the hatcheries assessed has the capacity to hatch 7 times per annum. As such, the annual production capacity of the three hatcheries in the period under review was estimated at 995,400 day old chicks. These hatcheries are therefore seriously underutilized in that only 22.5% of the total capacity is hatched.

Traditional chicken production mostly suffers from high mortality. However, it is cheaper and thus more widespread.

3.5.2. Aggregation

Aggregation in The chicken value chain in the Gambia is least developed and tilized. The potential to tilized the traditional poultry production in The Gambia lies in aggregation and storage of life bird for marketing. Storage facilities are scare, and where they are tilized, cost of electricity is high and uncompetitive. The three industrial operation EMPAS, T-Farms and Gunjur Poultry farm (owned by Mr. Momodou Sanyang) operate outlets close to the Tourist Development Area that collect life birds, process them and package them for selling. However, in the past two years, most of the market outlets have not operated even up to 30% capacity.

3.5.3. Processing

The two processing plants have the capacity to process 2,565,000 broilers per annum when fully utilized in 190 working days. During the Livestock assessment of 2014, an observation of the poultry processing process was conducted as depicted in the figure below.

Figure 11.

Chicken Processing Facilities – The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2014.

Figure 11.

Chicken Processing Facilities – The Gambia. Source: Department of Livestock Services 2014.

It is estimated that less than 1% of traditionally produced chicken is processed. There are about four small scale processing facilities (for slaughtering and dressing) established by the Livestock and Horticulture Development Project in some regions of the Gambia. However, even these are grossly ustomizeded as most people prefer life birds.

3.5.4. Distribution

The mode of transport for the distribution of chicken and chicken products is by road transport using cars. No specific types of cars or vehicles are use for the transportation of poultry products from farms to markets or from one market to another. The two industrial poultry producers EMPAS, Tee Farms have had market outlets near the Tourist Development areas. At village level, chicken are either sold at village level, farm gate or taken to the nearby lumos in small quantities.

3.5.5. Commercialisation

Per capita consumption of chicken in the Gambia in 2007 was equivalent to 1.1 kg. In the rural areas of the Gambia, this can be as low as 0.5 In 1996, it was estimated that egg consumption levels in rural Gambia was negligible, and FAO estimated national egg consumption levels at 1 kg per capita per year in 2001 and 2003.

Frozen whole chicken, chicken cuts and offal and eggs represent the most significant poultry products imported to the country. Close to 88% of the population purchase their poultry products (meat and eggs) from the supermarkets, while a quarter each buy from local producers, as well as the local market (Touray, 2008). Most of the Supermarkets get their supplies from imports. Importation of poultry and poultry products is mostly from Europe (Holland, Germany), USA and Brazil and Senegal as well.

Figure 12.

Import Sources _ Chicken.

Figure 12.

Import Sources _ Chicken.

Figure 13.

Chicken Imports_ Sources and Volumes.

Figure 13.

Chicken Imports_ Sources and Volumes.

In 2009, the country imported 4,237 metric tonnes of chicken and 565 metric tonnes of eggs valued at D51,743,000 and D27,679.000.00, respectively. In 2010 and 2011, 4,909 and 6,484 metric tonnes of poultry meat were imported. The quantities of shell eggs imported during the same periods were 2,108 and 3,333 metric tonnes.

Chicken products from the traditional sector and commercial farms are sold live (broilers), at farm gate, to intermediaries, or directly to consumers. In the rural areas, the main live bird (indigenous) markets comprise the Lumos. Beside the Lumos, the other markers are urban markets in the urban areas of the Gambia. Industrial buyers also form a significant market for life birds in The Gambia

In these markets, there are specific areas where the caged birds are sold. These birds are either sold live, or slaughtered and dressed, at the request of the client. These designated areas lack the basic hygiene and sanitation facilities. As the birds are in close contact with humans, and also given that the offal and by-products from the slaughtered birds are not properly disposed of, the potential risks for disease transmission are high. Furthermore, the slaughtering of the birds is done without veterinary supervision

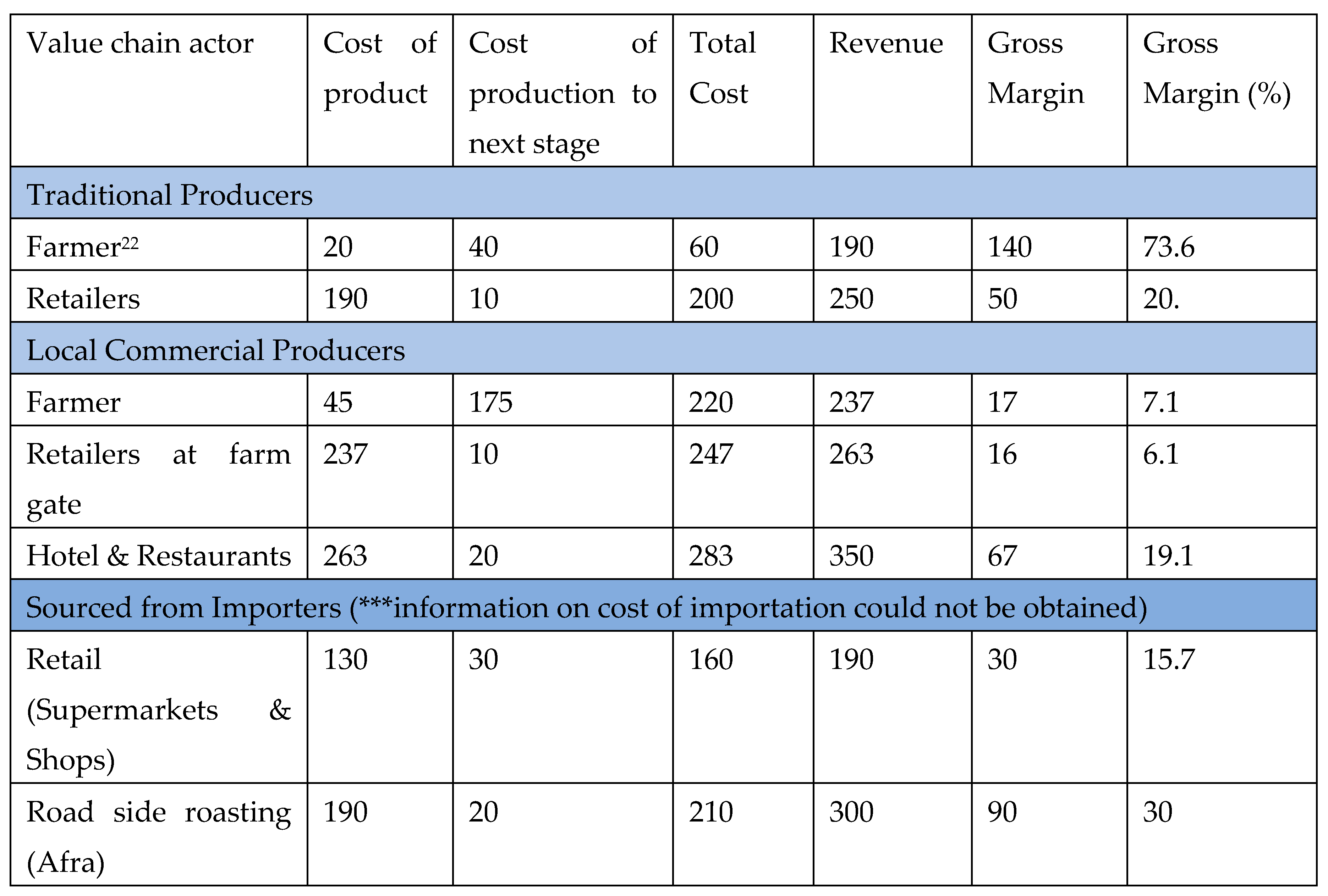

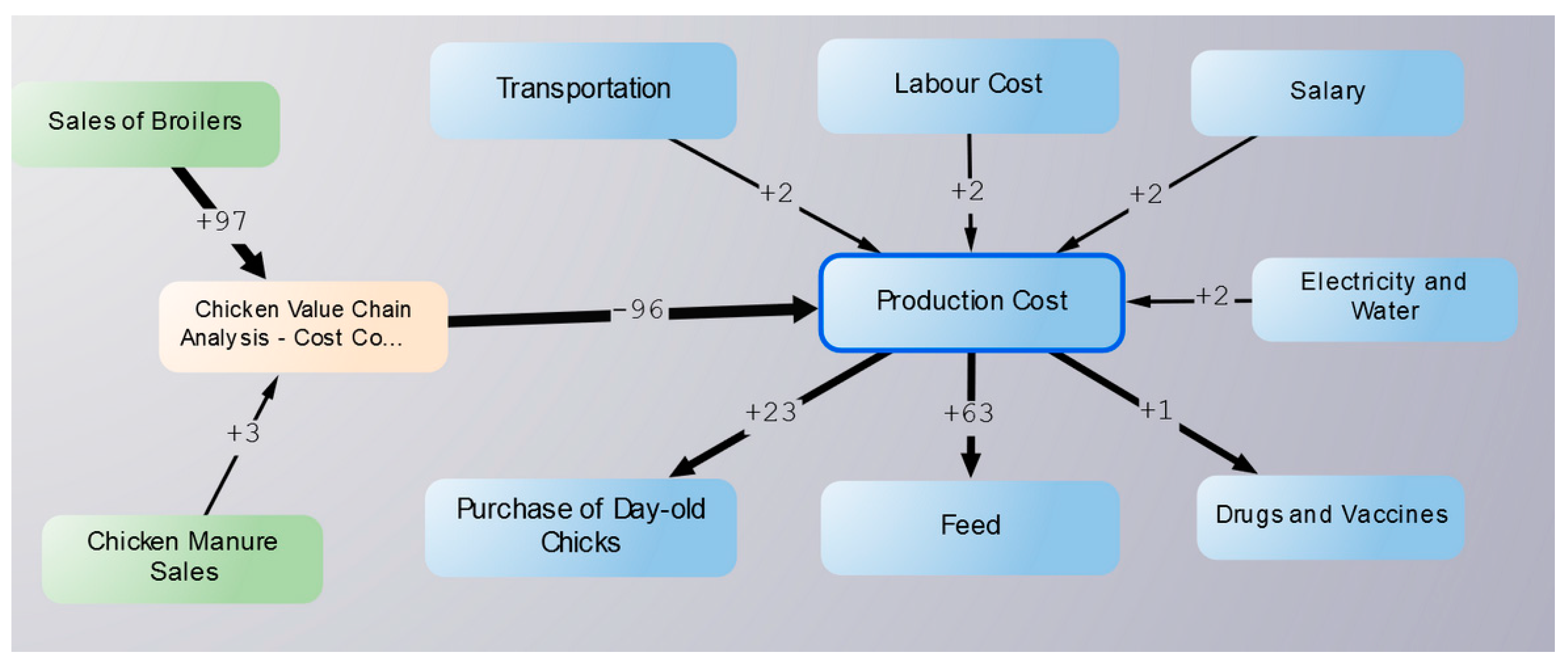

3.6. Margin analysis

The major cost in the production of chicken in The Gambia is the cost of feed. This is approximately 60-63% of the cost of raising chicken. The second most important cost is the cost of buying day-old chicks. Currently all the day-old chicks being raised in The Gambia are imported from Senegal. This represents 18 – 23% of the cost of producing chicken.

From our calculation, we estimate that the cost of raising one broiler in The Gambia is about D220.00. For every broiler raised, farmers receive a gross margin between D17 – D20. Therefore the return on investment for raising chicken is calculated as 9%.

Most chicken produced in The Gambia (60-70%) are sold as life birds at maturity to retailers. These are sold at farm gate. On average the cost is about 225 per life bird, weighing approximately 1.3 – 1.6kg after dressing. Retailers will transport, keep them in ustomized cages around major markets for selling to individual consumers.

On average, the chicken is sold for the price of D250 – D275. The cost of transportation and other cost (caging, payment of taxes) is D10 per bird.

The Chicken value chain in The Gambia comprises the farmer, wholesalers, retailers and market traders. However, for the purpose of this report, we will focus on the chain from local production, to retailers and then market vendors.

Figure 14.

Margin Analysis.

Figure 14.

Margin Analysis.

The margin analysis shows that, while it is very profitable to produce chicken through traditional means, the production cycle is much longer and done at far small scale. With effective diseases control and access to market, traditional chicken production in The Gambia can be expanded and ommercialized.

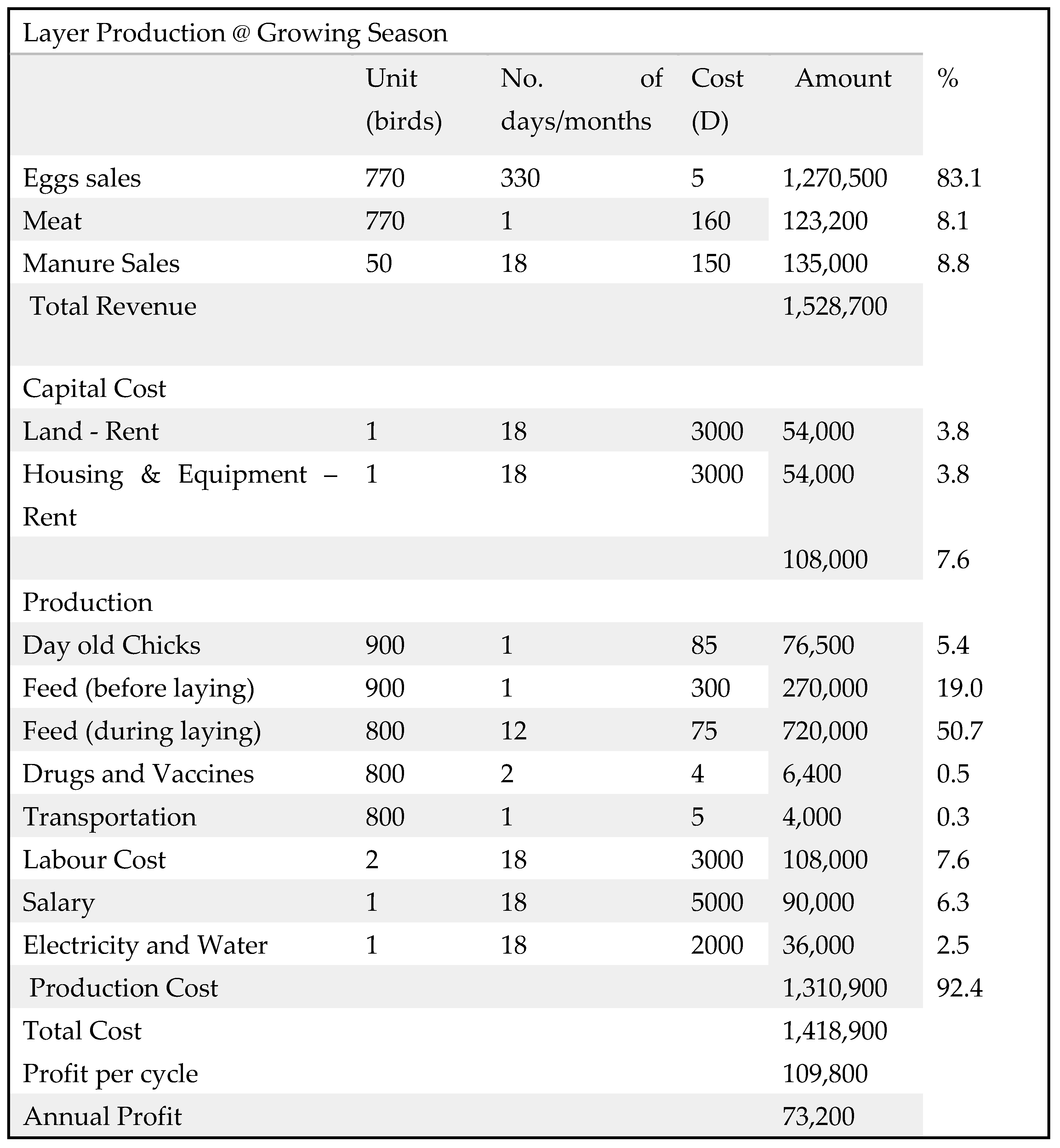

The figure below shows that 90% of the cost for raising poultry is operating costs. These include cost of buying day-old chicks, feed, drugs and vaccines, salaries, labour costs, and transportation. For the revenue the sale of chicken or eggs represents between 85-96% of the revenue from chicken production. The detailed cost calculation s is shown in the two tables below;

Figure 15.

Cost Components for Chicken Production.

Figure 15.

Cost Components for Chicken Production.

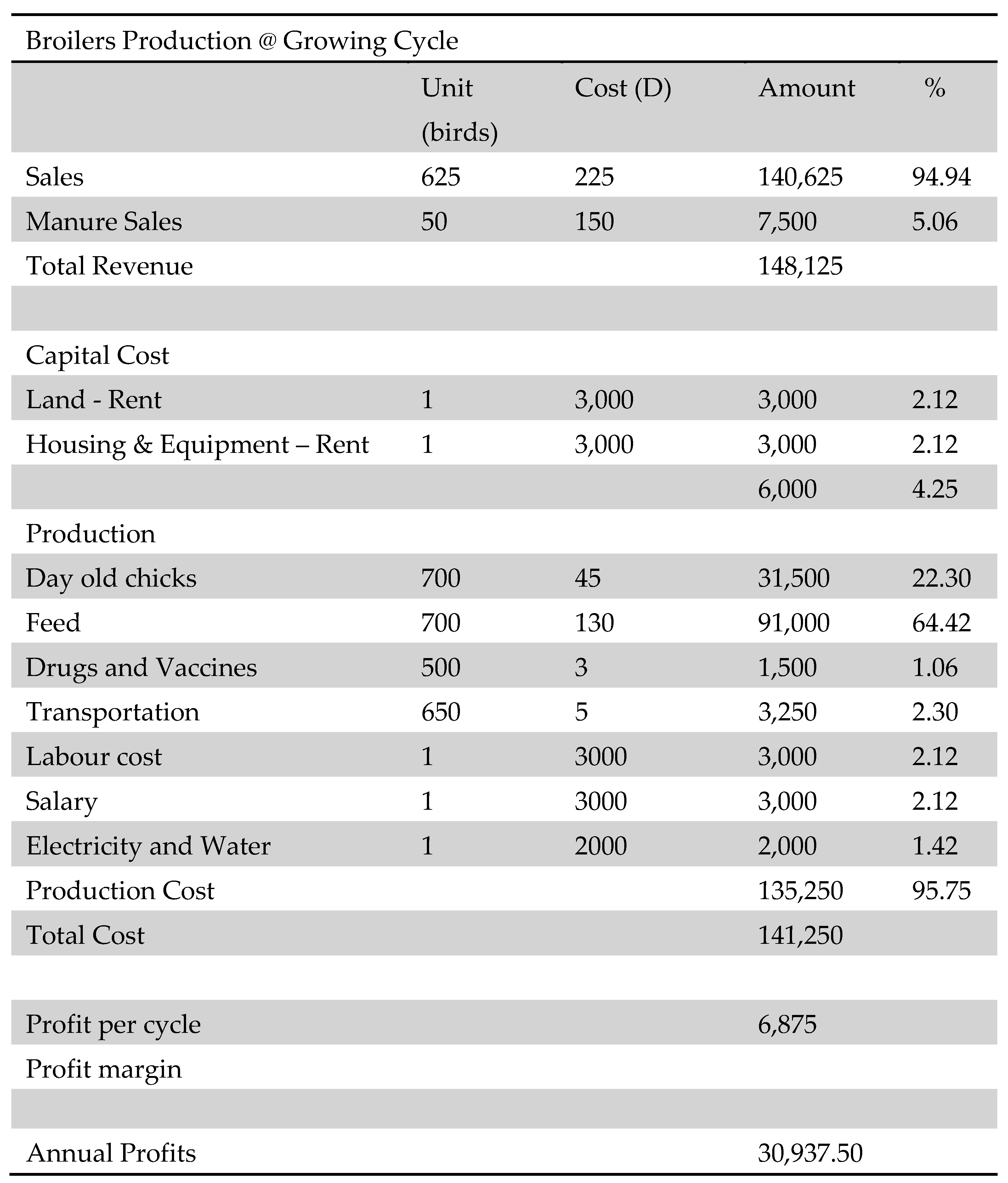

The tables below show estimated cost for the production of broilers and layers. This data is collected from discussion with poultry farmers and through reviews of accounts held by some of the farms. The figures were validated during the Stakeholders mapping by discussing with other farmers and staff of technical departments under the Department of Livestock Services

The cost for broiler production system is estimated 625 birds for one ton of chicken. Each bird is estimated to weigh 1.6kg as a life bird.

Figure 16.

Broiler Production: Cost estimates.

Figure 16.

Broiler Production: Cost estimates.

We observe that the larger the number of birds in broiler production, the lower the unit costs and thus the higher the profitability. This is similar to the conclusion in Lieshout and Touray 2018 that Broiler farming will only yield an attractive work/risk rewarding profit for 1 farmer with a minimum of 500 live birds.

The figures are slightly different from the production of broilers. The table show that it is relatively more productive and profitable to produce layers than broilers.

In the tables above, we make the following assumptions.

- -

Every layer produces at least D330,000 a cycle (18 months)

- -

Exit rates for commercial poultry are low

- -

The minimum broiler farm size to employ 1 FTE is 500 birds.

- -

Every bird sold at the market produces between 1.3kg.

Figure 17.

Layer Production: Cost Components.

Figure 17.

Layer Production: Cost Components.

Unlike Lieshout and Touray 2018, we observe that small scale layer farming is more attractive than small scale broiler (egg) farming.

3.7. Value chain governance

The Agriculture sector has been regarded as one of three priority sectors of Government in the Gambia from the 1990s to date- from PRSP 1, PRSP II, PAGE, NDP. The Chicken value chain is one of the common targeted commodities for most government projects, especially for projects implemented in the Agriculture and the Natural Resources Sectors, Rural development, in youth and Migration, in Employment creation and now in Climate Change Adaptation intervention.

The Department of Livestock Services serves as the technical service for the Ministry of Agriculture. The Department of Livestock Services supports in extension services provision, disease control, meat examination, training of livestock producers etc.

The Ministry of Trade industry and employment is responsible for the trade policy. Together with the Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs and the Gambia Revenue authority influence chicken imports through policies around tariffs and other import taxes.

The projects under the Ministry of Agriculture, International NGOs, FAO, UNDP etc provide financing and start up capital. Over the years, projects have provided start up capital for youth and women farmers either individually or as a group. Donor funded projects have also provided training to livestock producers, provision of grants for the construction of key infrastructure such as hatcheries, slaughter houses, life bird markets, meat stall etc.

3.8. Value chain support services

The private sector is a key enabler of the chicken value chain in The Gambia. Veterinary services are mainly provided by private veterinary services. In 2019, six privately owned veterinary services provider are in operation. However, most of them target commercial farms

Only 5-8% of the chicken value chain in The Gambia is financed by banks and Microfinance instructions. The transaction cost for loans is high estimated at 27- 30% (including interest and transaction cost) Reliance Financial Services provides most of the private financing to chicken farmers in The Gambia. For example, Reliance Financial Services provides loans at a cost 1.5% per month interest, 2% transaction fees with Land Clearance/ Lease document serving as collateral. On the other hand, most commercial bank loans are structured around 21% interest, 3% transaction fees with a Land Lease document as guarantee

3.9. Enabling environment

3.9.1. Societal environment

Chicken is the second cheapest source of protein accessible to the Gambia; second to fish. Compared to the price of meat (beef, mutton etc), Chicken is cheaper. In most ceremonies (naming ceremonies, weddings etc), the most common protein is chicken. This presents one of the high demand areas for chicken.

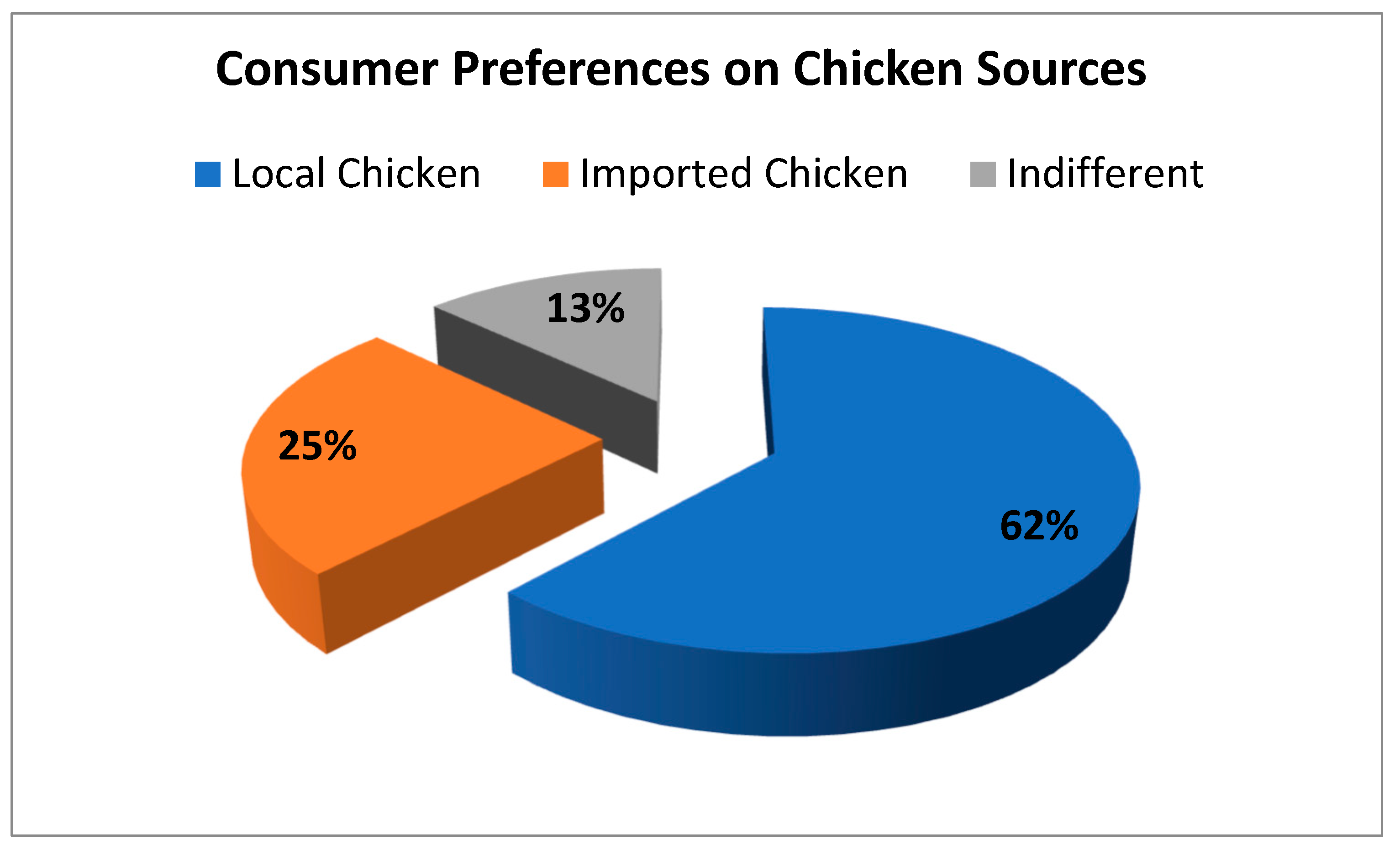

One of the key enablers of chicken production in The Gambia is the increasing awareness of Gambians to adopt healthy consumption behaviours. These include the preferences around consumption of fresh foods, including locally produced fresh chicken. The figure below shows consumer preference for local chicken over imported chicken in The Gambia.

Figure 18.

Consumer Preferences on Chicken _ Local and Imported.

Figure 18.

Consumer Preferences on Chicken _ Local and Imported.

Adapted from ActionAid and Oxfam 2004

Chicken is also produced by more than 60% of households in the rural areas. It is easy to produce, especially at semi-intensive scale. Women are also produce 60% of chicken. Therefore, it can be targeted for poverty reduction at scale.

It is important to note that there is a favourable government policy environment as in the second generation of both the Agriculture and Natural Resource Policy and the Gambia National Agricultural Investment Plan for increased odernizationion of agriculture and making agriculture attractive for young people.

3.9.2. Natural environment

Chicken is produced throughout the year in The Gambia unlike some of the other Sahelian countries.

Chicken is regarded as a climate resilient value chain. It is very competitive and can be produced in smaller spaces. With increasing populations, environmental degradation and loss of rangelands, chicken is easier to producer than other livestock, such as cattle and small ruminants. Over the past two decades, a high level of deforestation and degradation of forests and rangelands have occurred. In urban, peri-urban and growth centres in The Gambia, raising of cattle and small ruminants is no more regarded as suitable for most of the regions In The Gambia.

Chicken Manure is highly recommended by Horticulture producers as one of the best and easily accessible. Other enablers to the growth of the chicken value chain include;

- -

Good road network across the length of The Gambia making cost f transportation lower

- -

Availability of raw material like groundnut cake, maize, oyster shells and smoke fish in The Gambia, unlike other parts of the neighbouring countries

- -

Low crime rate and political stability in The Gambia

- -

Low frequency of disease outbreaks

4. Constraints and upgrading opportunities

4.1. Root causes of constraints and integrated solutions

Competition from Cheap Imports

The key binding constraint in the chicken value chain is the competition that local producers face from cheap chicken imports.

There is evidence of dumping of chicken in the Gambia as the retail prices of chicken from the source countries are higher than the retailer prices that are sold in The Gambia (ActionAid and Oxfam 2004). In addition, the tariffs on imports have reduced. An early report showed that tariffs have reduced from 28% to 18% on both chicken and egg imports from 1998 to 2004.

The price of imported frozen whole chicken has been about GMD 70.83 or US$ 3.11 per kg, while that of dressed or live broilers from the commercial sector is about GMD 96.15, or US$ 4.22, and local chickens (live) GMD 107.14, or US$ 4.71. (FAO 2008). Similarly in Lieshout and Touray, it is estimated that the average bird from Brazil weighs 1.89 kg frozen, so the kg price is D116. From there it is sold onto the market with margins ranging from 15-25%. The cost price for an equal product from the Gambia is D158 per kg, or 36% more expensive. From there it is sold onto the market with margins ranging from 15-25%. The cost price for an equal product from the Gambia is D158 per kg, or 36% more expensive.

The tariffs and non-tariff barriers imposed by countries make it difficult for poultry farmers and businesses in developing countries to compete because of the imports of cheap subsidized poultry products from the US and the EU (GIEPA, 2012)

Therefore, relative to import, chicken production is affected by high cost of production in The Gambia. This is as a result of the high cost of inputs which are also imported. These include feed and day-old chicks, which represent close to 85% of the cost of production. It is however important to note that the quality of some of the local produce are higher than that of imported products, especially eggs. It is generally observed that imported eggs are 30 -48% smaller than locally produced eggs (Lieshout and Touray 2018).

Access to market

As a result of the high prices of locally produced chicken and the availability of cheaper substitutes from imports, most farms do not have a ready market. As a result, farmers do not produce at capacity. The inability for farmers to secure markets makes poultry production in The Gambia highly risky and not attractive to bank financing.

Access to finance

Loans to the Agricultural sector in The Gambia are estimated to be less than 5% of total credit provided by commercial banks and microfinance institutions. The high cost of interest as well as the poor penetration of financial services providers, excludes farmers from accessing loans. Banks also provide short term loans which are largely seen to be inappropriate for long gestation periods for poultry production (especially layers).

In addition, Collaterals requested by banks cannot be provided by farmers, especially women farmers and small businesses

To access funding from projects, matching grants are normally the structure of financing. The Matching grants are schemes that provide grants to framers up to the tune of 40-60% of the cost of the business. These matching grants require initial capital as well as business proposal. The inability of farmers to write business proposals or pay for the cost of writing a business proposal therefore tend to exclude farmers from accessing matching grants provided by projects.

Cost of input (Feed)

Since feed is 60- 63% of chicken production, appropriate investments should be made in that segment of the value chain. It is estimated that investments in a proper feed milling plant with well qualified skilled staff can reduce cost of production by 14 – 18%. It can also have a multiplier effect of maize production and maize farmers in The Gambia.

The Processing function of chicken in the Gambia is not developed as more than 90% of birds are sold as life birds. However, stakeholders argue to portioning of poultry into smaller potions presents an opportunity that is untapped. Secondary portioning, roasting and selling is growing in The Gambia because, it provides for buyers with small family sizes who cannot buy whole chicken or prefer to buy some part of the chicken

Processing Facilities and costs

More than 80% of the chicken produced in The Gambia is still produced through local tradition systems. One of the key challenges is the access to markets of these schemes. The absence of aggregation points fitted with storage facilities is one of the key limiting factors to the expansion and the odernization of the traditional poultry production in The Gambia. For traditional poultry producers, the market is at local level where prices are low. In most cases, sale of chicken is done during the hungry or lean period when prices are low. The availability of aggregation centres fitted with storage capabilities close to communities can create a market for farmers at local level.

High Mortality due to Newcastle Disease outbreak in The Gambia

It is believed that more than 60% of mortality of chicken in The Gambia is caused by Newcastle disease. This is even more important for local production of chicken.

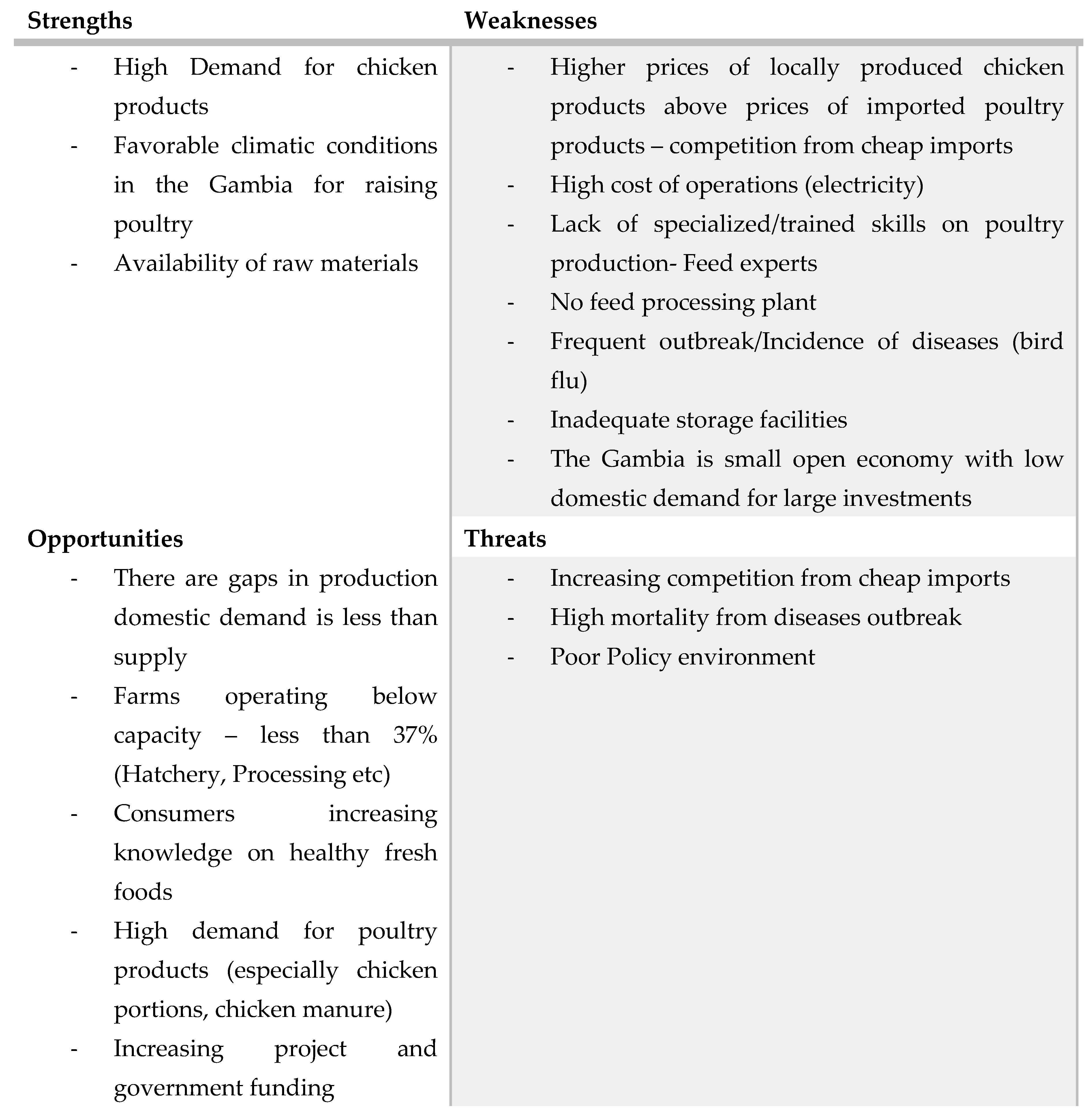

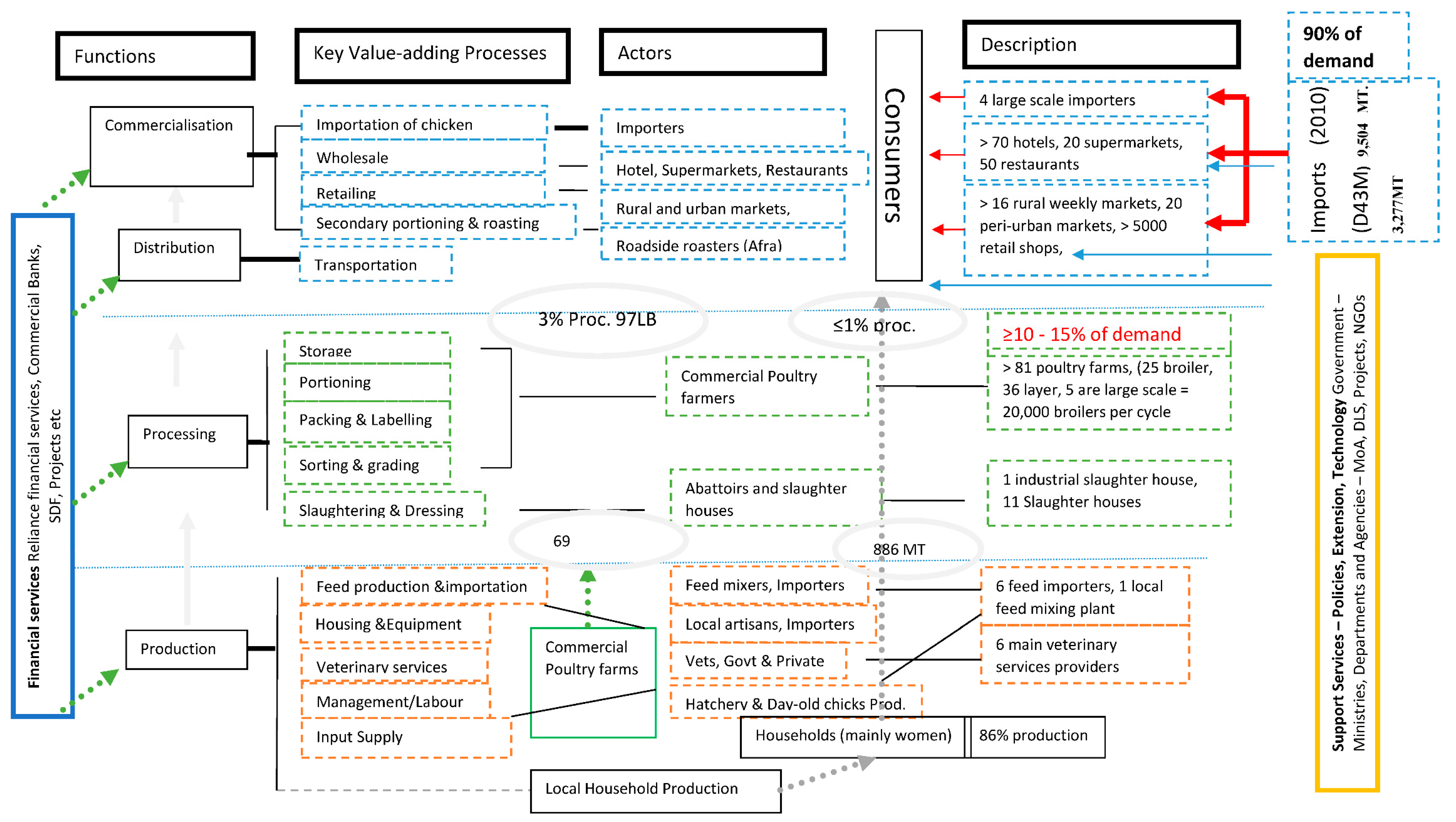

4.2. SWOT Analysis

The table below represents the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Challenges in the Chicken Value Chain in the Gambia. The SWOT analysis was developed with stakeholders during the stakeholders mapping exercises, through consultations with actors in the field and through relevant literature review.

Figure 19.

SWOT Analysis Table.

Figure 19.

SWOT Analysis Table.

A study by GIEPA, details the following facts about the Gambia that makes Chicken Value chain investments attractive and that the country can be used as a hub for West Africa in terms of the poultry value chain.

Strong demand and production potentials (for example egg imports grew more than41%from 2010 – 2011 and Good competitive agricultural policy framework

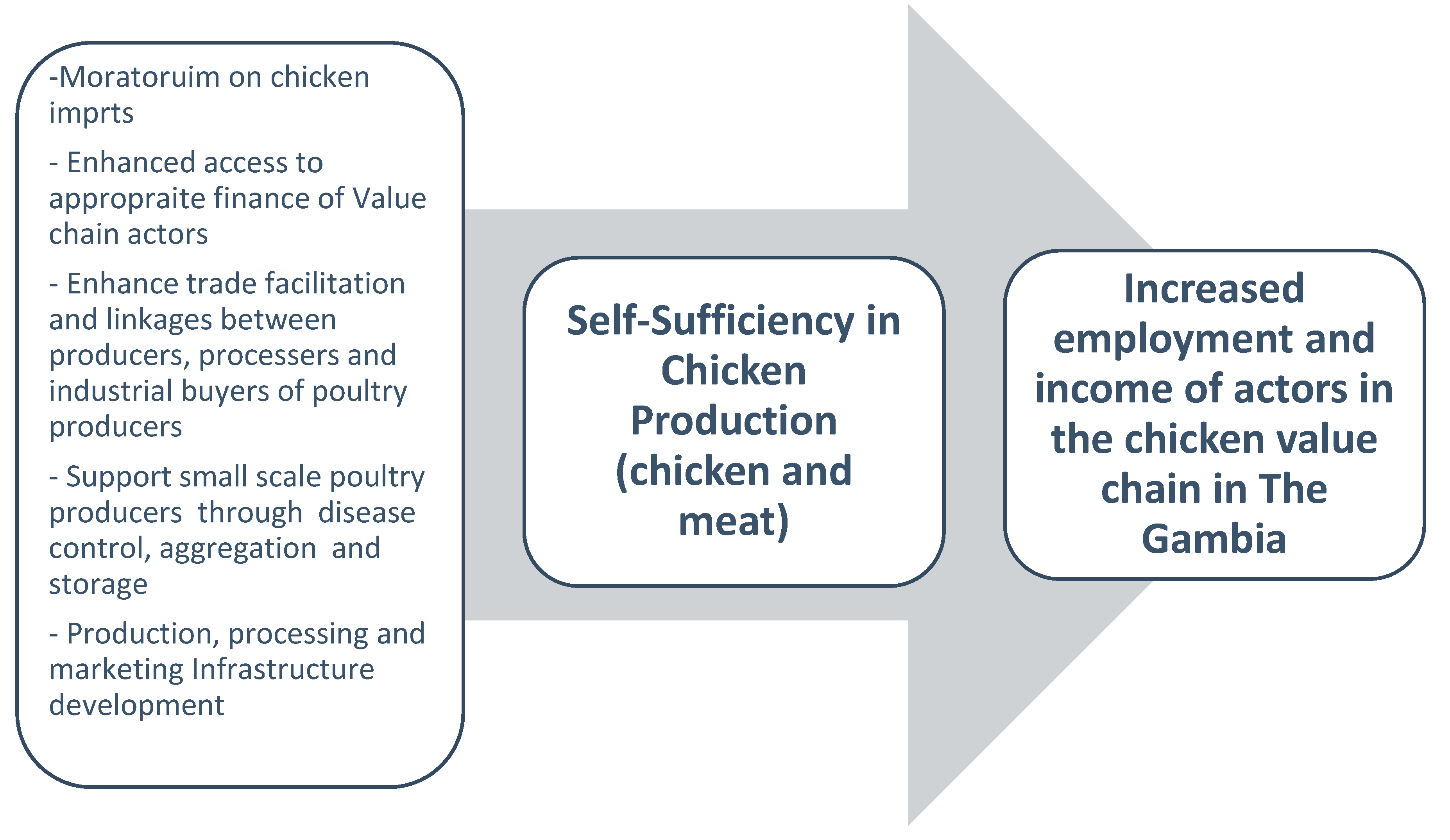

5. Vision of Success

Discussion with most of the key actors and through review of relevant grey literature, chicken production is envisioned to grow by 15% by 2020 from 2008 levels, through commercialisation of agriculture. The actors’ vision of successes converges on having access to markets for Gambian farmers. “When I am able to sell all my chicken and eggs at the appropriate times, then this country will more”. Mr. Amadou Demba.

The Vision of the actors of the Chicken value chain In the Gambia is self sufficiency in Chicken production in The Gambia. Given that current farms are operating below capacity (less than 40%) capacity, it is believed that with appropriate enabling environment for the operation of the farms to full capacity and the encouragement of new entries, the Gambia can produce its chicken and egg demands. The key factors include;

A ban, or a moratorium r the imposition of high taxes on Importation of chicken products in The Gambia

Investment in Feed Production

Training of specialised experts in feed production, veterinary services etc

This Theory of change is built on the vision of challenges and opportunities of the chicken value chain in the Gambia.

Figure 20.

Theory of Change for the Development of Chicken Value Chain.

Figure 20.

Theory of Change for the Development of Chicken Value Chain.

5.1. Strategic recommendations

Imposition of import tariffs or Import Bans

Undoubtedly, an overwhelming major of commercial poultry producers (88% in Action Aid and Oxfam 2004) recommend protection of local industry through regulations of imports. Enhance trade facilitation through imposition of an import ban or a moratorium on chicken and eggs imports is therefore recommended.

Employment potentials of Chicken Value Chain

Given the high participation of imports in the production and marketing of chicken in The Gambia, the key leverage point is that of the development and implementation of trade policies that guarantee access to market and reduction in the cost of imported inputs. The potential for the chicken value chain to generate employment is phenomenal – “If we control imports, the chicken industry in the Gambia can sustainably employ an equivalent number of staff employed in the Agricultural Sector by Government. I have observed how changes in policy concerning importation of chicken in Senegal have resurrected the local chicken industry in Senegal within a few years. I suggest that Government of the Gambia should consider doing the same” – Mr. Ngum, an importer of Chicken feed and Day-old chicks noted.

Enhanced access to appropriate finance for Chicken Value chain actors

Chicken production is largely profitable in The Gambia. Providing competitive long-term financing to actors will boost the ability for expansion of critical inputs and infrastructure in the Value Chain. For example, financing of a feed mill can reduce the cost of chicken in The Gambia by at least 14%.

- -

Make available soft loans to value chain actors through public-private partnerships

- -

Reduce collateral on loans

- -

Introduction of Insurance schemes on chicken producers to hedge failures

Modernisation and commercialisation of Local – Traditional Chicken Production

More than 90% of the chicken produced in The Gambia is produced through traditional means; where chicken are left to fend for food. It is the value chain for the poor, especially women and young people. Chicken is produced by more than 50% of households in The Gambia. Mortality cause by Newcastle disease causes up to 45 - 50% of chicken mortality in The Gambia

Therefore the modernisation of the local production through Disease control and access to market through aggregation and storage can lead to a 150% increase in chicken production within 18 months. Support is required for small scale poultry producers through aggregation and enhanced market infrastructure.

Support specialized training in poultry production, processing and disease control etc.

There is a shortage of specialized skills for veterinary services in The Gambia. For example, it is reported that there is no feed nutritionist that can support feed production in The Gambia. GamHolland, the only feed mill in The Gambia rely on foreign experts from Holland to support the mixing of feed.

Infrastructure development:

Support feed manufacturers through public-private partnerships, provision of small-scale hatcheries