Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gas Diffusion Layer package and nanofibers synthesis

2.2. SCMFCs architecture and operation

2.3. Characterizations and measurements

3. Results and Discussion

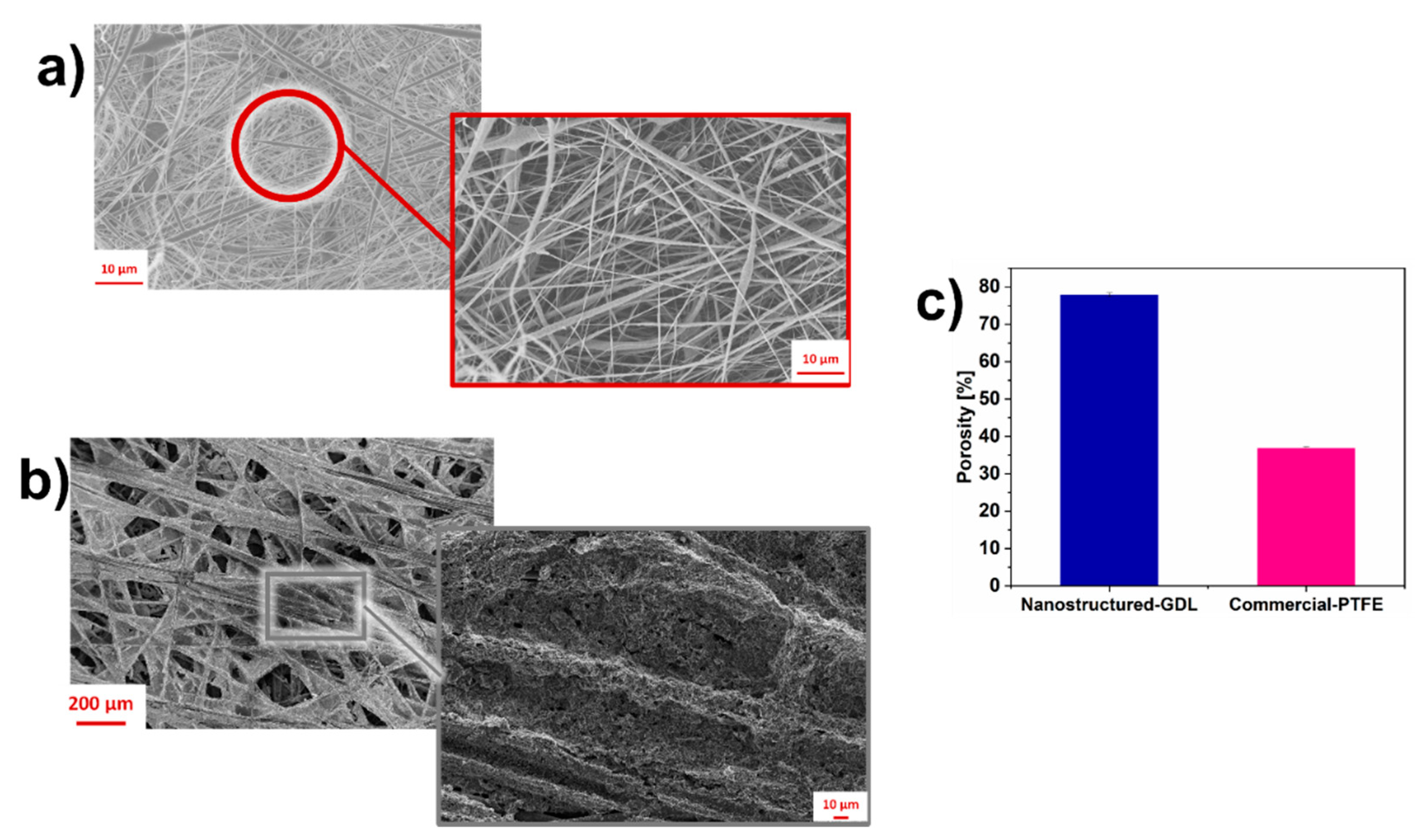

3.1. Morphological properties of nanostructured-GDL and commercial-PTFE

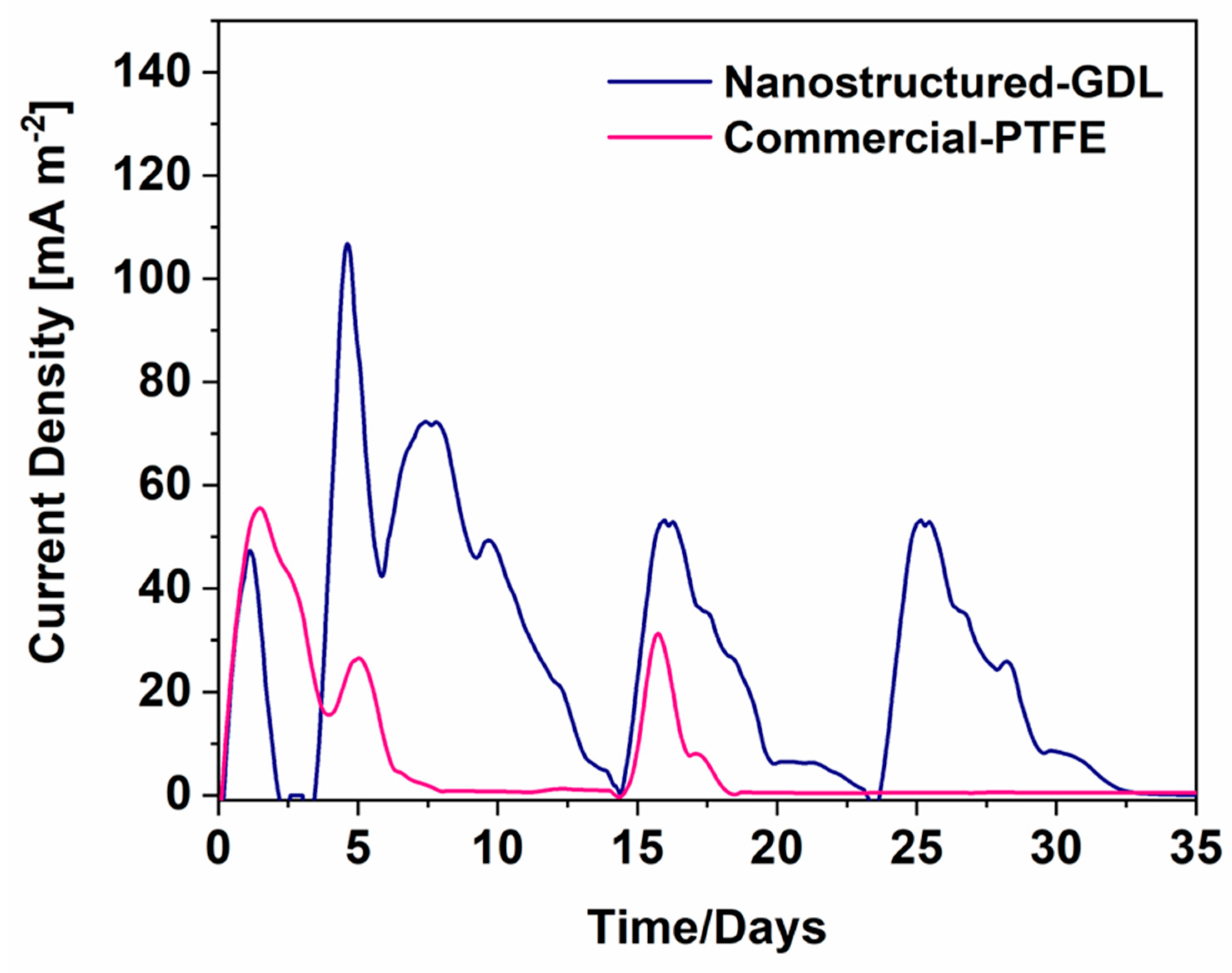

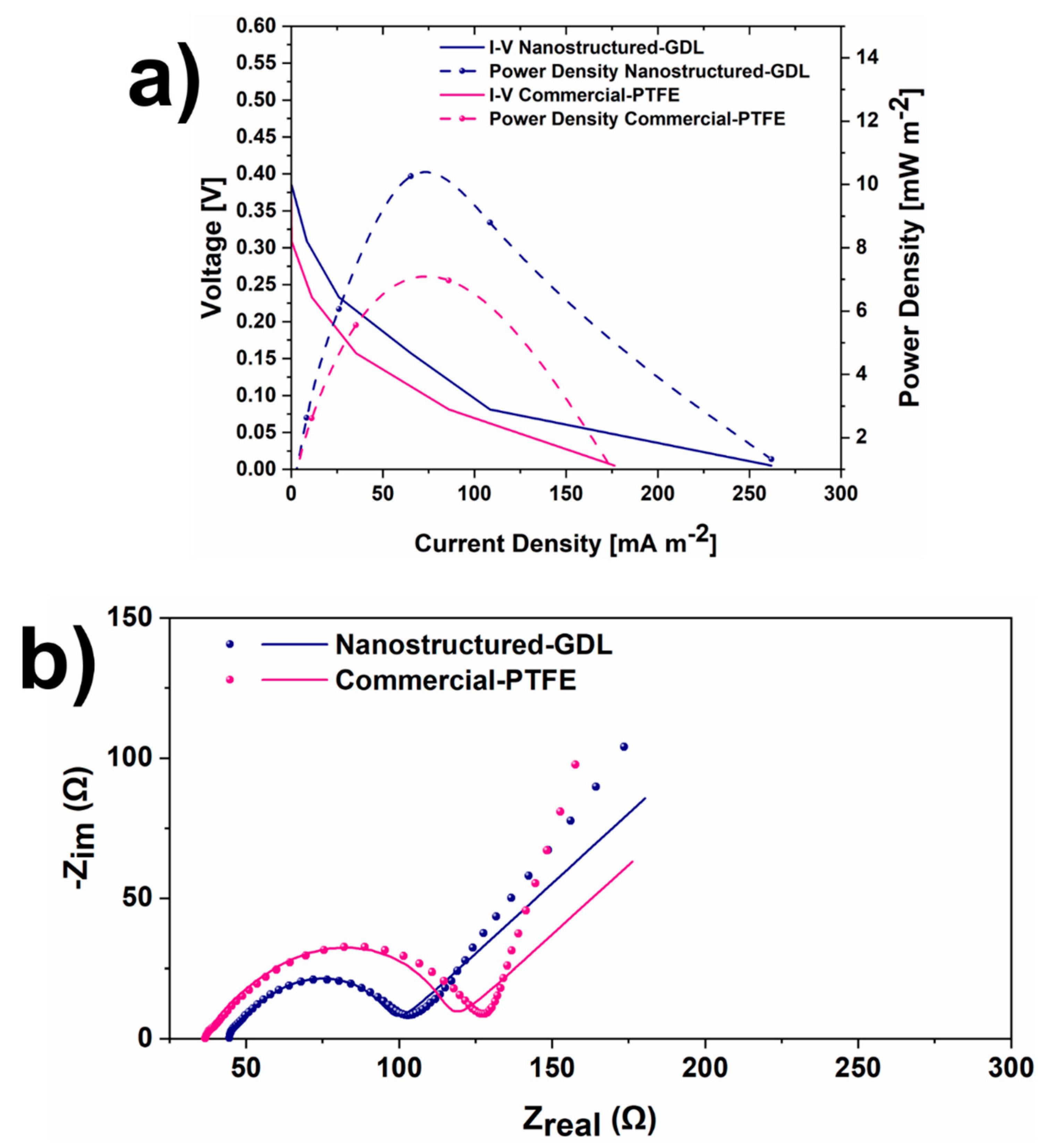

3.2. SCMFCs performance

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walsh, B.; Ciais, P.; Janssensz, I.A.; Penuelas, J.; Riahi, J.; Rydza, F.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Obersteiner, M. . Pathways for balancing CO2 emissions and sinks. Nature Communication 2017, 8, 14856–14868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, B. Single chamber microbial fuel cells (SCMFCs) treating wastewater containing methanol. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 2340–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cistiani, P.; Trasatti, S.P. In Field Applications of Single Chamber Membraneless Microbial Fuel Cells (SCMFCs) for Wastewater Treatment, Metal Reduction and Nutrients Removal. 2014 Meet. Abstr. MA2014-02 2283. [CrossRef]

- Logrono, W.; Perez m Urquizo, G.; Kadier, A.; Echeverria, M.; Recalde, C.; Rakhely, G. Single chamber microbial fuel cell (SCMFC) with a cathodic microalgal biofilm: A preliminary assessment of the generation of bioelectricity and biodegradation of real dye textile wastewater. Chemosphere 2017, 176, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanikkul, P.; Pisutpaisal, N. Membrane-less MFC based biosensor for monitoring wastewater quality. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglio, M.; Massaglia, G.; Vasile, N.; Margaria, V.; Chiodoni, A.; Salvador, G.P.; Marasso, S.L.; Cocuczza, M.; Saracco, G.; Pirri, C.F. A fluid dynamics perspective on material selection in microbial fuel cell-based biosensors. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 4533–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Curtis, T.P.; Head, I.M.; Velasquez-Orta, S.B.; Scott, K. A single chamber packed bed microbial fuel cell biosensor for measuring organic content of wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2879–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E.; Rabaey, K. Conversion of wastes into bioelectricity and chemicals by using microbial electrochemical technologies. Science 2012, 337, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E.; Hamelers, B.; Rozendal, R.; Schroder, U.; Keller, J.; Freguia, S.; Aelterman, P.; Verstraete, W.; Rabaey, K. Microbial fuel cells: methodology and technology. Environmental Science and Technology 2006, 40, 5181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babauta, J.; Renslow, R.; Lewandowski, Z.; Beyenal, H. Electrochemically active biofilms: facts and fiction. A review Biofouling 2012, 28, 789–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnisch, F.; Aulenta, F.; Schroeder, U. Comprehensive Biotechnology 2nd ed; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2011; pp. 644–659. [Google Scholar]

- Dange, P.; Savla, N.; Pandit, S.; Bobba, R.; Jung, S.P.; Gupta, P.K.; Sahni, M.; Prasad, R. A Comprehensive Review on Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cells. Journal of Renewable Materials 2022, 10, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.B.; Daud, W.R.W.; Ghasemi, M.; Leong, J.X.; Lim, S.S.; Ismail, M. Non-Pt catalyst as oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cells: A review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2014, 38, 4870–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, K. Chapter 3.5 - Effective and Nonprecious Cathode Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Microbial Fuel Cells. In Microbial Electrochemical Technology Sustainable Platform for Fuels, Chemicals and Remediation Biomass, Biofuels and Biochemicals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2019; pp. 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Kundu, P.P. Enhancing sustainable bioelectricity generation using facile synthesis of nanostructures of bimetallic Co–Ni at the combined support of halloysite nanotubes and reduced graphene oxide as novel oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalyst in single-chambered microbial fuel cells. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2022, 47, 29413–29429. [Google Scholar]

- Sciarria, T.P.; Costa De Olyveira, m.A.; Mecheri, B.; D’ePifanio, A.; Goldfarb, J.L.; Adani, F. Metal-free activated biochar as an oxygen reduction reaction catalyst in single chamber microbial fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 462, 228183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindrella, L.; Kannan, A.M.; Lin, J.F.; Saminathan, K.; Ho, Y.; Lin, C.W.; Wertz, J. Gas diffusion layer for proton exchange membrane fuel cells—A review. Journal of Power Sources 2009, 194, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, L.R.; Shukla, A.K.; Behrsing, T.; Avery, N.R.; Muddle, B.C.; Forsyth, M. Diffusion layer parameters influencing optimal fuel cell performance. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2000, 30, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergat, M.; Shukla, A.K. Effect of diffusion-layer morphology on the performance of solid-polymer-electrolyte direct methanol fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2002, 104, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Wan Do, H.; Jin, D.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Soon, A.; Moon, J.; Shim, W. Revisiting the Role of the Triple-Phase Boundary in Promoting the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Aluminum–Air Batteries. Advanced functional Materials 2021, 31, 2101720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Huang, W.; Wan, L.Y.; Yang, J.; Xie, R.J.; Zheng, Y.P.; Tan, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.S.; Zaghib, K.; Zheng, L.R.; Sun, S.H.; Zou, Z.Y.; Sun, S.G. Identification of the active triple-phase boundary of a non-Pt catalyst layer in fuel cells. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadd8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pang, Y.; Xu, H.; Martinez, A.; Chen, K.S. PEM Fuel cell and electrolysis cell technologies and hydrogen infrastructure development – a review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garapati, M.S.; Nechiyil, D.; Jouliè, S.; Bacsa, R.R.; Sundara, R.; Bacsa, W. Proton-Conducting Polymer Wrapped Cathode Catalyst for Enhancing Triple-Phase Boundaries in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, C.; Agrios, A.; Pasaogullari, U.; Li, B. Effects of gas diffusion layer (GDL) and micro porous layer (MPL) on cathode performance in microbial fuel cells (MFCs). International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2011, 36, 13096–13104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathas, M.F., Roth, J., Fleming, J., Lehnert, W., Vielstich, W., Gasteiger, H.A., et al., Eds.; HandBOok of Fuel Cells-Fundamentals, Technology and Applications. (Chapter 42). 2003, Vol.3.

- Li, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wu, S.; Song, D.; et al. A review of water flooding issues in the proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Journal of Power Sources 2008, 178, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaogullari, U.; Wang, C.Y. Two-phase transport and the role of micro-porous layer in polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Electrochimica Acta 2004, 49, 4359–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostick, J.T.; Fowler, M.W.; Ioannidis, M.A.; Pritzker, M.D.; Volfkovich, Y.M.; Sakars, A. Capillary pressure and hydrophilic porosity in gas diffusion layers for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources 2006, 156, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, E.; Grattieri, M.; Faggianelli, A.; Cristiani, P.; Trasatti, S. PTFE effect on the electrocatalysis of the oxygen reduction reaction in membraneless microbial fuel cells. Bioelectrochemistry. 2015, 106, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Yang, Y.W.; Hung, T.F.; Huang, J.; Yang, F.L. Novel single-layer gas diffusion layer based on PTFE/carbon black composite for proton exchange membrane fuel cell. J. Power Sources. 2007, 173, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamavaram, V.; Veedu, V.; Kannan, A.M. Synthesis and characterization of platinum nanoparticles on in situ grown carbon nanotubes based carbon paper for proton exchange membrane fuel cell cathode. J. Power Sources 2009, 188, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakata, S.; Hara, M.; Kakinuma, K.; Uchida, M.; Tryk, D.A.; Uchida, H.; Watanabe, M. Investigation of the effect of a hydrophilic layer in the gas diffusion layer of a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell on the cell performance and cold start behaviour. I. 2014, 120, 247–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, T.; Nakajima, H.; Inamoto, M.; Morishita, M. Novel hydrophilic double microporous layer coated gas diffusion layer to enhance performance of polymer electrolyte fuel cells under both low and high humidity. Journal of Power Sources 2013, 234, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Min, B.; Logan, B.E. Cathode performance as a factor in electricity generation in microbial fuel cells. Environmental Science Technology 2004, 38, 4900–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaglia, G.; Frascella, F.; Chiadò, A.; Sacco, A.; Marasso, S.L.; Cocuzza, M.; Pirri, C.F.; Quaglio, M. Electrospun Nanofibers: from Food to Energy by Engineered Electrodes in Microbial Fuel Cells. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaglia, G.; Margaria, V.; Sacco, A.; Castellino, M.; Chiodoni, A.; Pirri, C.F.; Quaglio, M. N-doped carbon nanofibers as catalyst layer at cathode in single chamber Microbial Fuel Cells. IJHE 2019, 44, 4442–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cathode electrodes | R1 [Ω] | R2 [Ω] | R3 [Ω |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanostructured-GDL | 44.3 | 12.04 | 38.4 |

| Commercial-PTFE | 36.9 | 25.7 | 50.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).