1. Introduction

An increase in factories, industrial activity, and demographic expansion has negatively impacted the environment by producing polluted and dangerous polluted water. Contaminated water flows primarily consist of emerging contaminants, which are persistent non-biodegradable chemicals [

1]. These substances linger in the environment, accumulate within food chains, and present hazards not only to human well-being but also to ecosystems and microbial populations [

2,

3,

4]. Water polluted by toxic heavy metals is a major problem worldwide. Strict environmental regulations on heavy metal discharge and growing demand for purified water exhibiting minimal concentrations of heavy metals content have highlighted the urgent need to develop efficient heavy metal removal technologies.

Water treatment is essential to make water suitable for various uses such as domestic activities, industrial and agricultural activities. Unfortunately, however, the polluted water treatment process itself has become an industry that pollutes the environment in various ways [

5]. In the past, water treatment methods were limited, but with advances in knowledge and technology, researchers have developed environmentally friendly and effective contaminated water treatment methods [

6,

7,

8].

The unique properties of nanosorbents offer unprecedented opportunities for the highly efficient and cost-effective metals removal. Different nanoparticles and dendrimers extensive research has been conducted to explore their potential, in this regard. While magnetite nanoparticles extensive research has been conducted to investigate their potential uses in the field of biomedicine [

9,

10]. On the other hands, their application in the environmental field has received limited attention in previous studies [

11].

Scientific research shows that Adsorption is a more efficient method used in water treatment and is increasingly used because of its affordability, convenient availability of raw materials and decreased usage of treatment agents [

12]. It has the capability to eliminate not only heavy metals present in polluted water but also organic substances and various contaminants in water [

13,

14]. Recent concerns focus using nanomaterials for the purpose of decreasing COD and BOD

5 levels, while taking into account ecological safety concerns [

15].

Magnetite nanoparticles are widely employed in the treatment of contaminated water due to their extensive specific surface area, concise diffusion paths, and surface functional groups that can be readily tailored for specific adjustments. Moreover, the application of an external magnetic field streamlines the separation of magnetite nanoparticles, simplifying their retrieval and enabling their reuse through recycling processes [

16].

Recent research has presented evidence indicating the beneficial impact of magnetic fields on wastewater treatment. Magnetic fields have also been examined in terms of their potential to safeguard human health [

17].

On the other hands, numerous researchers have investigated the use of magnetic fields to treat water in various areas. For example, magnetic water treatment has been tested to see how it affects the growth of fruits and vegetables. Some studies found that using these devices led to better yields. For instance, the yield of melon crops increased by 39%, and potato yields went up by 41%, with a magnetic field strength of 0.33 Tesla and 52% with 0.29 Tesla, compared to using untreated water [

18]. Additionally, scientists have looked into how magnetic treatment affects the physical and chemical properties of water. They examined factors like pH, conductivity, surface tension, turbidity, and evaporation rate. Using magnetic devices with different strengths (0.5 and 0.29 Tesla), they found that applying a magnetic field made the water’s pH decrease. This change seemed to enhance the germination rate and seed capacity before the seeds developed into seedlings [

19]. Some researchers even explored the effects of magnetic treatment on melon production in areas with high soil salinity. They discovered that applying a permanent magnetic treatment lowered the water’s electrical conductivity while increasing its pH. These changes led to a significant increase in melon crop yields. The researchers focused on a concept involving radical ion pairs as the entities affected by magnetic fields and the source of resulting effects. Several scientists reported that exposing irrigation water to a magnetic field prior to use improved plant productivity and altered the water and mineral metabolism of the plants [

20,

21,

22]. The magnetic treatments also impacted the physical parameters of water, such as pH and electrical conductivity. The application of a magnetic field reduced water’s surface tension by up to 24% and increased the amount of water that evaporated compared to untreated water [

23].

Reducing COD and BOD

5 is of utmost importance to levels that allow this sewage to be discharged into rivers. According to the ISO standard (International-Organization for the Standardization of Discharge of Sewage to the Aquatic Environment), the COD value is required to be less than 30mgO

2/L, and the BOD

5 value is less than 250mgO

2/L. Today, many researchers focus on COD and BOD

5 removal using magnetite nanoparticles [

24,

25,

26,

27].

This study is the first focusing on diminishing BOD5 and COD levels in water by adsorption on magnetite nanoparticles under a high magnetic intensity. Adsorption on magnetic nanoparticles is enhanced by utilization of a magnetic field through physical excitation of ions as well as molecules of nanoparticles and organic pollutants. Furthermore, the implementation of a magnetic field simplifies the separation of magnetite nanoparticles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the samples and magnetic process

The water samples were collected from the Wedi El Bey river Tunisia.

MNPS are combined with a magnetic field intensity of 1 Tesla from Delta Water for the treatment of polluted water over a period of 50 minutes.

2.2. Synthesis of MNPs

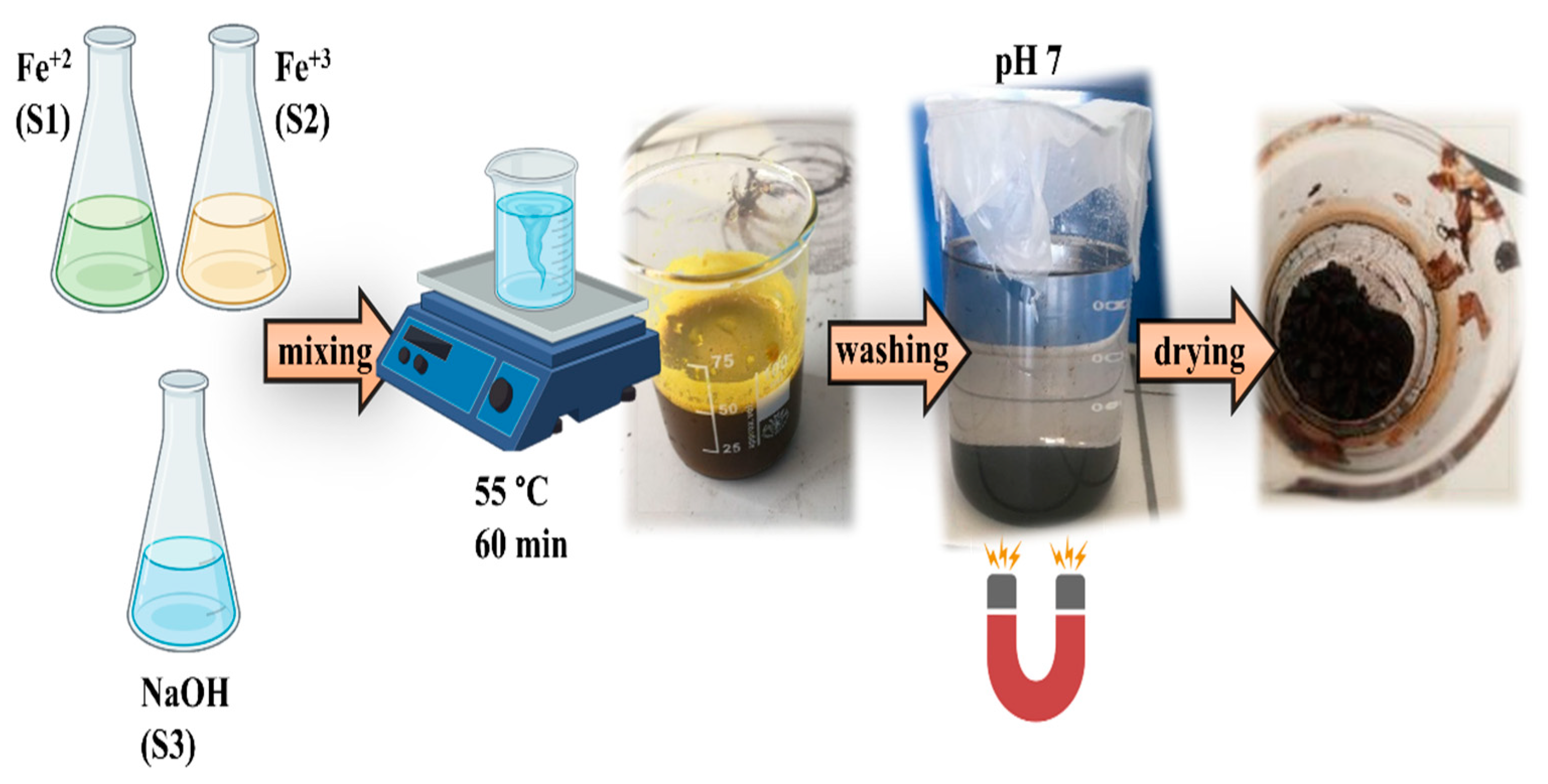

MNPs were prepared by the co-precipitation protocol presented in

Figure 1, following the Massart method with some modifications [

28] as described below. Deionized water (20 mL) was combined with 3.5 g of iron (II) chloride to prepare the Fe

+2 precursor solution (S1), while for a Fe

+3 precursor solution (S2), by dissolving 8.64 grams of iron(III) chloride in 20 milliliters of deionized water. For the third solution (S3), dissolve 7.2 g of sodium hydroxide in 100 mL of deionized water. For each experiment, the combined volume of the three solutions was 140 mL, and the reaction took place at 55°C for a duration of 60 minutes. Maintain chemical reaction volume by adding deionized water. The obtained MNPs were magnetically decanted and washed with deionized water until they attained a neutral pH (7-8). Well-dried magnetite nanoparticles were stored for characterization as follows.

2.3. Characterization

The morphological aspect of MNPs was characterized using a FEG TECNAI T20 Transmission-Electron-Microscope (TEM) at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV and Quanta FEG 650 model scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 10 kV, 120000 of magnification and 12.1 mm of working distance. For TEM analysis, samples were conditioned from a dilute solution containing the MNPs by dropping the colloid onto a holey Carbon cupper grid to determine the morphology and particle size distribution. Statically analysis (n=200) was performed on TEM images using ImageJ analysis software. The chemical composition of the samples was analyzed using a Perkin Elmer FTIR Frontier Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer. Additionally, chemical analysis was performed using an Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) detector on a Quanta FEG 650 model Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) operating at 10 kV. The crystal structure of the resulting product was investigated using a Bruker D8 Advance high-resolution X-ray powder diffractometer (XRD) with Cu-K radiation. (1.5418 Å).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. MNPs characterization

3.1.1. Electron microscopy analysis

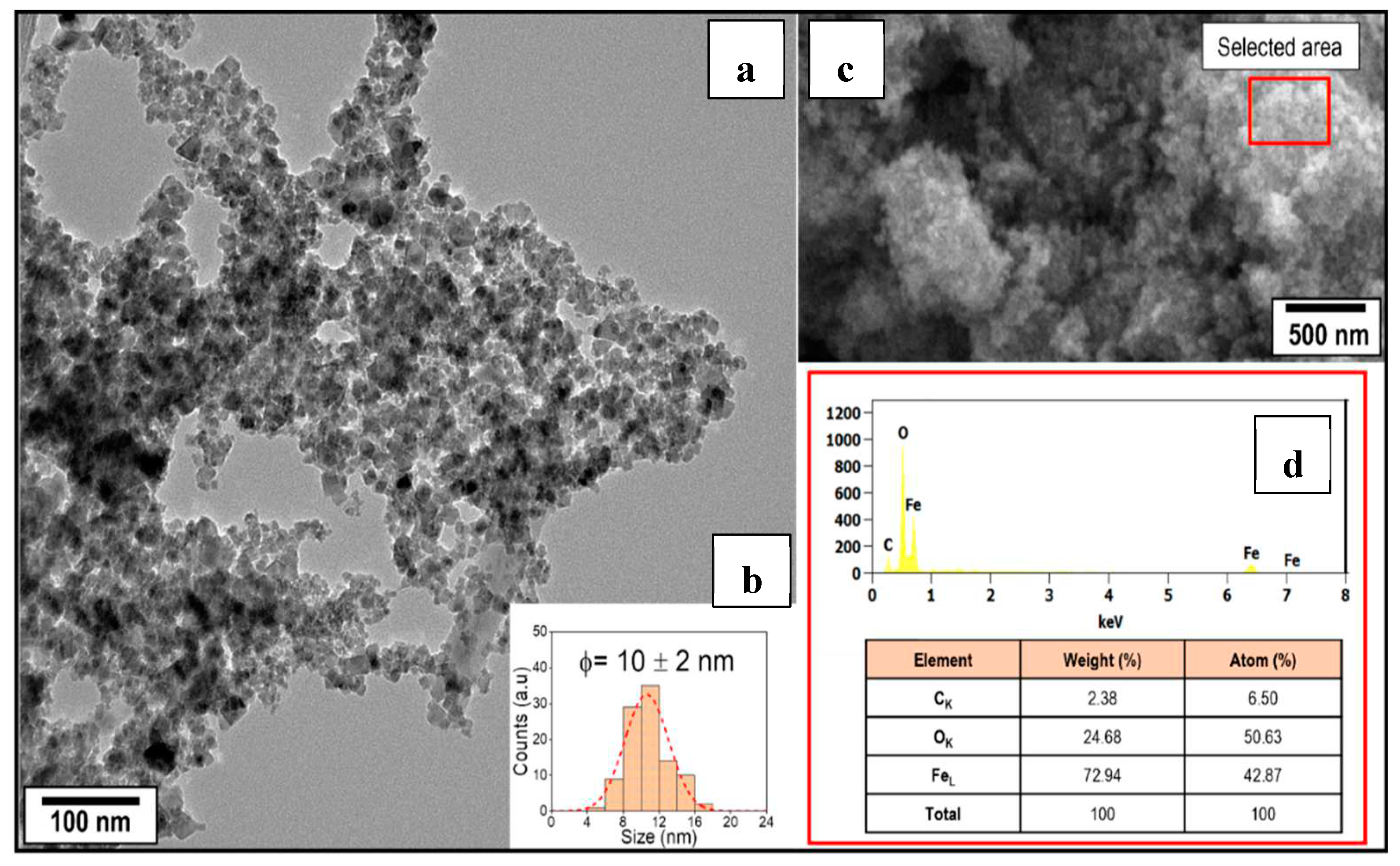

TEM analysis revealed partially agglomerated particles with an average particle size = 10 ± 2 nm (

Figure 2a). The histogram of the static sample analysis (n = 200) is shown in

Figure 2b. It was previously reported that nanoparticle agglomeration was induced by Van der Waals forces arise due to operating conditions and the drying process. The existence of remaining water and NaOH facilitated the clustering of nanoparticles due to a nanometer size in the tens of nanometers.

The SEM image (

Figure 2c) confirmed the agglomeration in cumulus over 500 nm and EDS spectrum (

Figure 2d) shown clearly the elemental contributions from Fe

L (0.705 eV), O

K (0.523 eV), and C

K (0.523 eV) present in the sample. According to the table of elemental analysis result, the sample contains 72.94% Fe and 24.68% O in mass. The presence of 2.38% of carbon can be attributed to the utilization of carbon tape for securing the sample to the holder.

3.1.2. FTIR Spectra

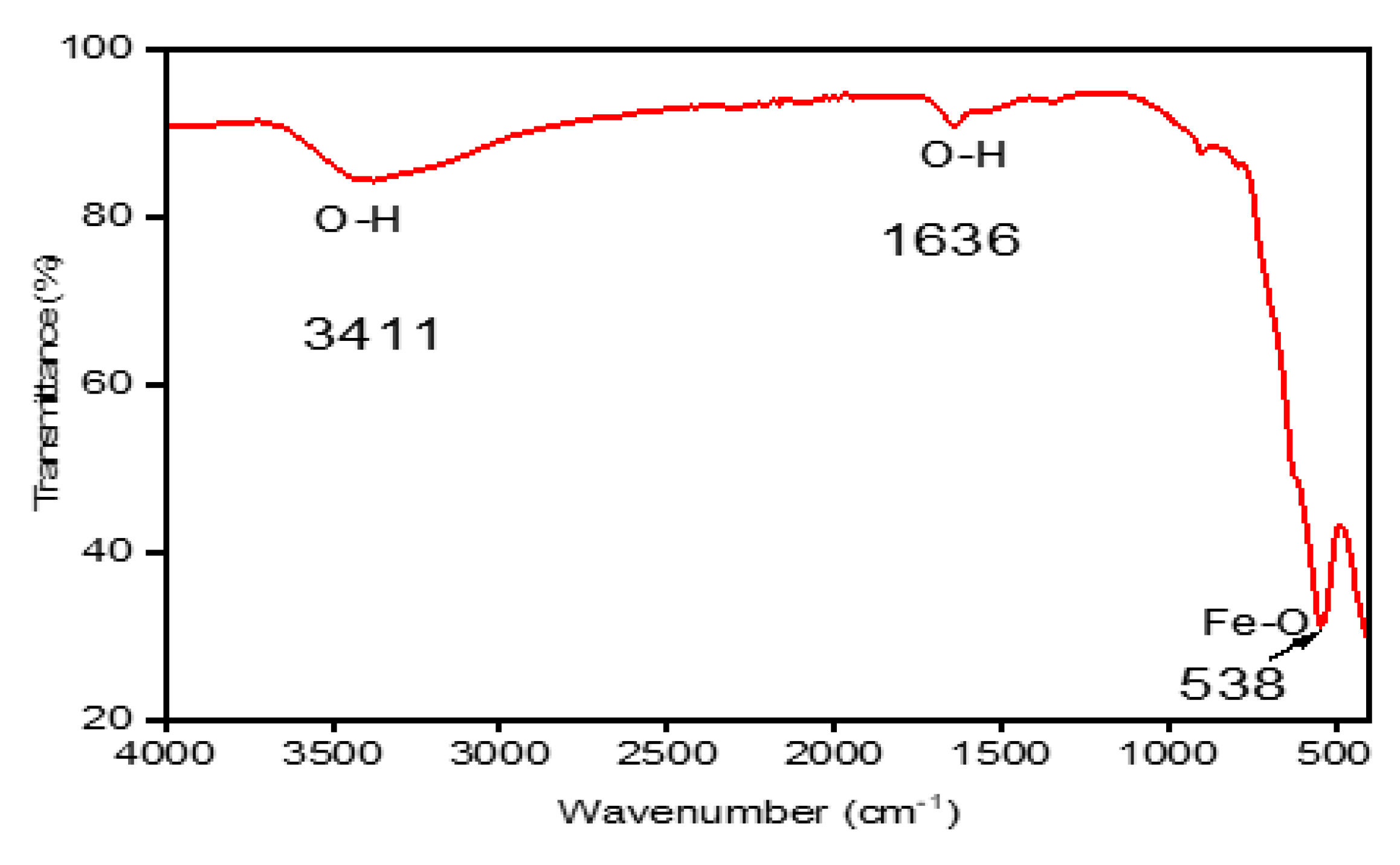

Figure 3 displays the FTIR spectra of the MNPS samples. It exhibits a noticeable absorption band at 538 cm

-1, corresponding to the stretching of Fe-O functional groups inherent to the magnetite lattice (Fe

3O

4).

Another important result is the absence of vibration mode of FeII-O assigned to maghemite, which appears generally at 613.32 cm-1, 509.17 cm-1 and mentioned in the literature. This result clearly shows that the obtained nano-product is composed only by pure magnetite.

O-H bending vibration and hydrogen-bonded water molecules adhering to the surface are responsible for two more vibration bands that are located at 3411 cm

-1 and 1636 cm

-1 [

29].

The outcomes of this research are in agreement with earlier studies that identified a broad and intense absorption peak within the range of 540 to 630 cm-1, which corresponds to Fe-O bonds in bulk magnetite.

The main interactions between hydroxyl groups (3411 and 1636 cm

-1) and Fe (538 cm

-1) were detected. Waldron’s work is cited by [

30] findings support the notion that magnetite can form crystals with interconnected structures, where atoms are bonded by balanced forces such as ionic, covalent, or van der Waals interactions. The observed outcomes suggest that vibrational modes of the Fe-O bond are linked to octahedral and tetrahedral sites, manifesting around 440 cm

-1 and 560 cm

-1, respectively.

3.1.3. (BET) Surface Area Analysis

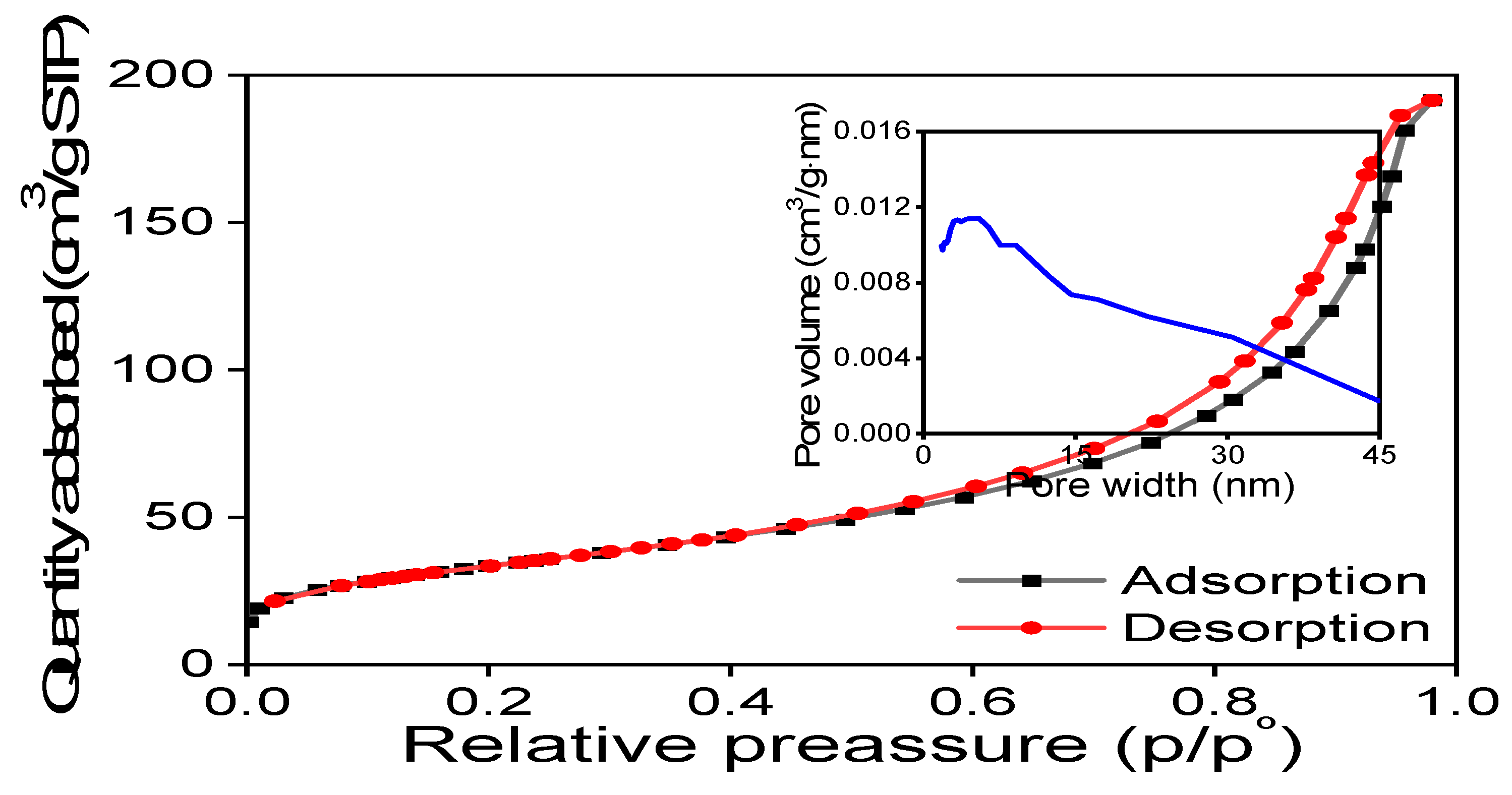

The MNPs underwent analysis using the BET technique to ascertain the specific surface area and distribution of porosity within the powder. These parameters are crucial for adsorbing pollutants in polluted water and enabling the removal of various molecules. The resulting BET surface area was 121.44 ± 0.14 m2/g. The pore volume measures approximately 0.28 cm3/g, and the pore diameter is 10.30nm.

As depicted in

Figure 4, the acquired MNPs exhibit characteristics akin to a type III isotherm, where the adsorbate-adsorbate interaction dominates while the substrate exerts weak interactions. However, the BET surface area is considerable and suitable for adsorption in heterogeneous surfaces.

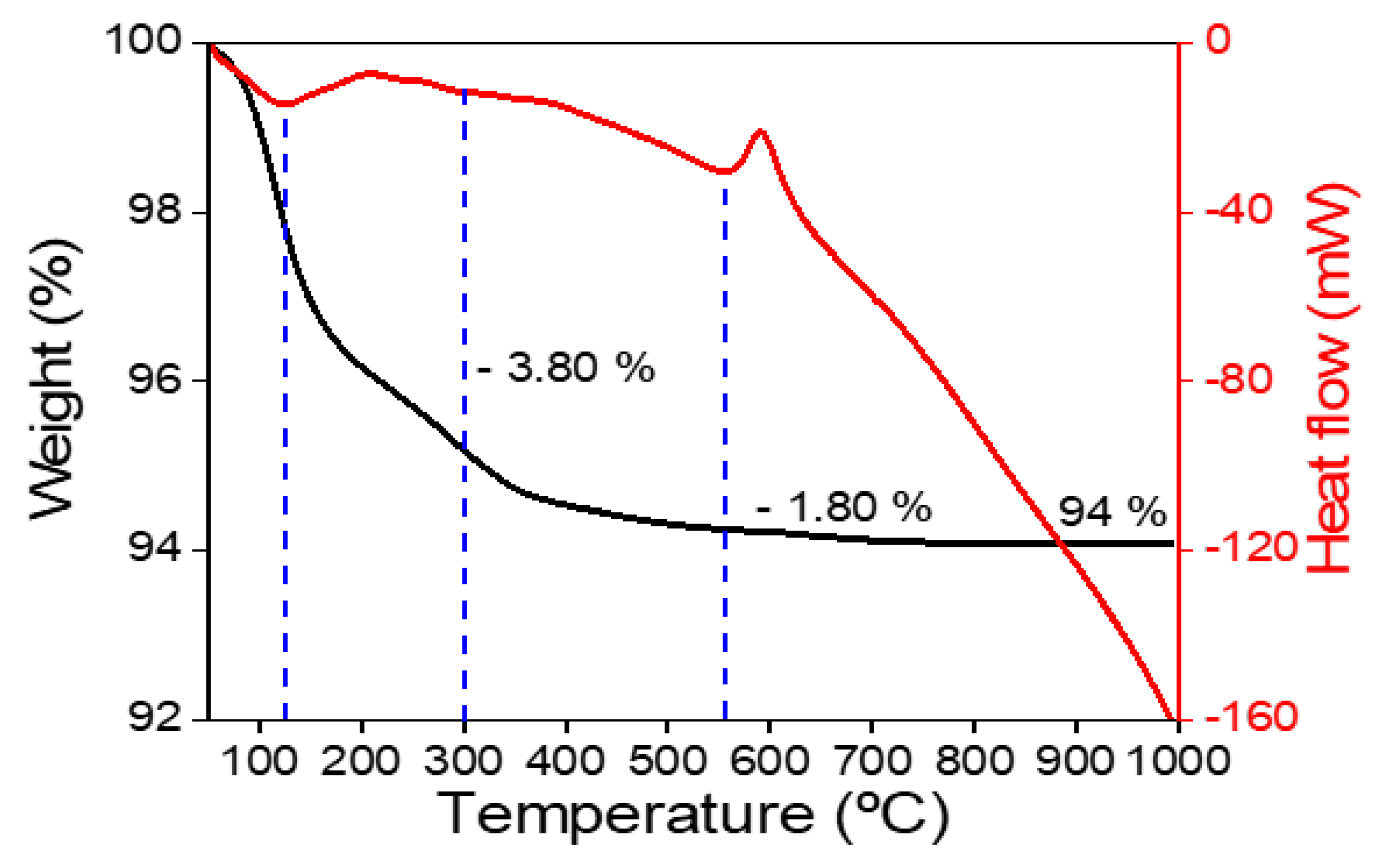

3.1.4. Thermal analysis

Figure 5 depicts the Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA) curve of the Fe

3O

4 precursor. The TGA curve in the thermogram shows two distinct mass loss phases. Between 50 and 300 °C, the initial mass loss phase is slow. The removal of surface adsorbed water was responsible for the mass loss, which was 3.80%.

The removal of physically adsorbed water during the decomposition of Fe3O4 is revealed by the second stage of mass loss, which occurs between 300 and 500oC and indicates a mass loss of 1.80%. The weight of the magnetite nanoparticles was nearly constant above 500 °C, but an exothermic peak was observed around 600°C, indicating a phase transition from Fe3O4 to Fe2O3. The phase transition was carried out at temperatures between 550 and 700 °C.

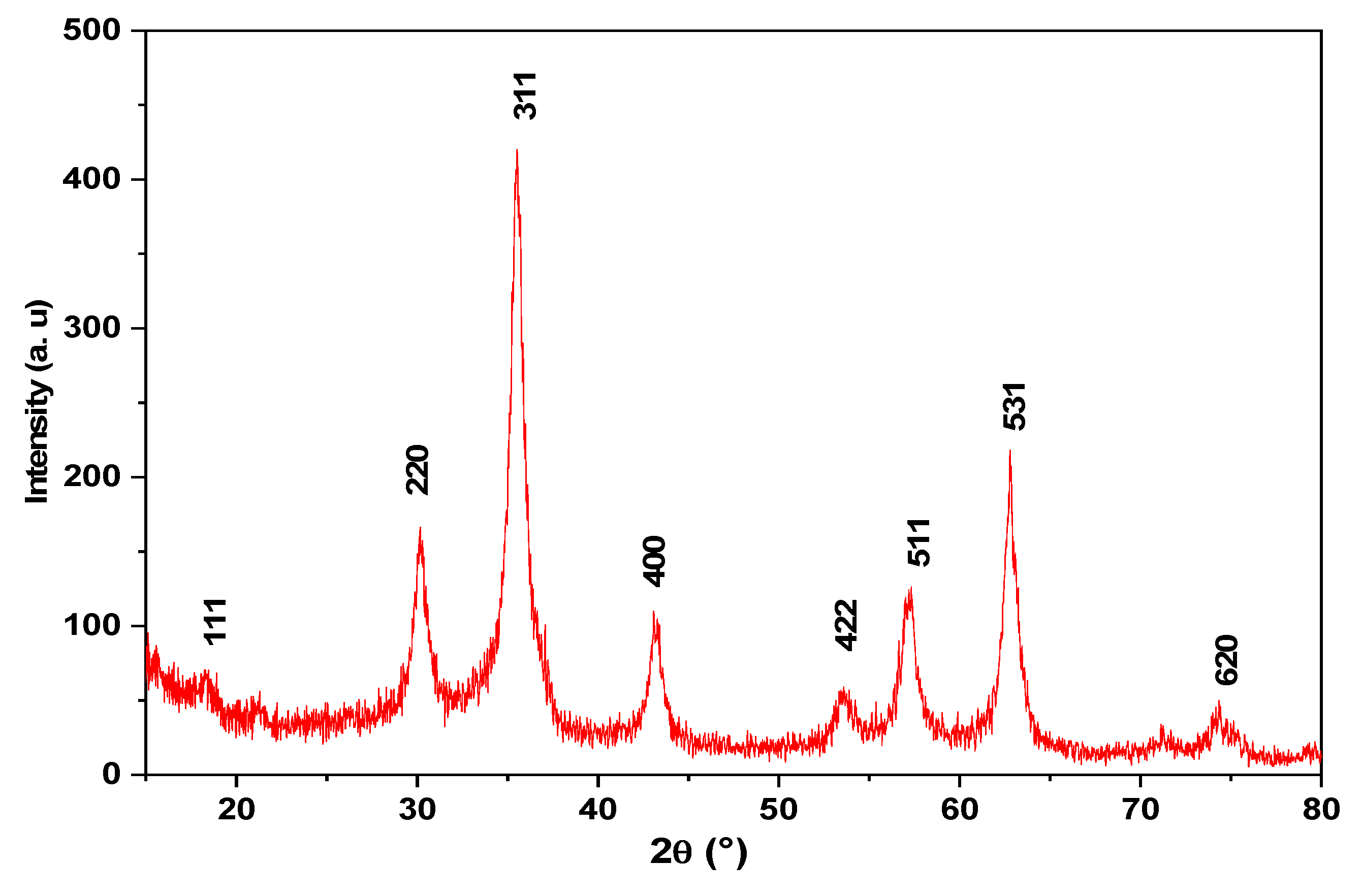

3.1.5. XRD analysis

Figure 6 illustrates the XRD patterns of the magnetite nanoparticles. All diffraction peaks are catalogued according to the Magnetite (Fe

3O

4) ICSD Pattern with the number 01-080-0390. The findings in the ICSD Pattern of Magnetite (Fe

3O

4) [

31,

32,

33,

34] are consistent with this outcome.

The produced magnetite has a cubic spinel structure, According to the Fe

3O

4 NP XRD pattern recorded in the literature [

35]. The crystalline and high purity of magnetite with nanoparticles size were confirmed by the extent of peak broadening and the absence of unaccounted peaks. Using Debye-equation Scherrer’s (2),The average crystal size of the magnetite nanoparticles was approximated [

36].

Where: D=represents the average crystal size,

: = signifies the wavelength of the X-ray radiation (1.5406 Å),K: denotes the dimensionless form factor (0.9), θ: signifies the Bragg’s angle in degrees and β: signifies the line’s FWHM (full width at half maximum) in radians [

37].

The FWHM of the Fe3O4 prominent peak (2 = 35.4s66°) of XRD patterns, which corresponds to the plane, was used to estimate the mean crystalline size (100). The average crystal size of the synthesized nanomaterials is ~ 10 nm.

3.2. MNPs as water quality enhancement agents

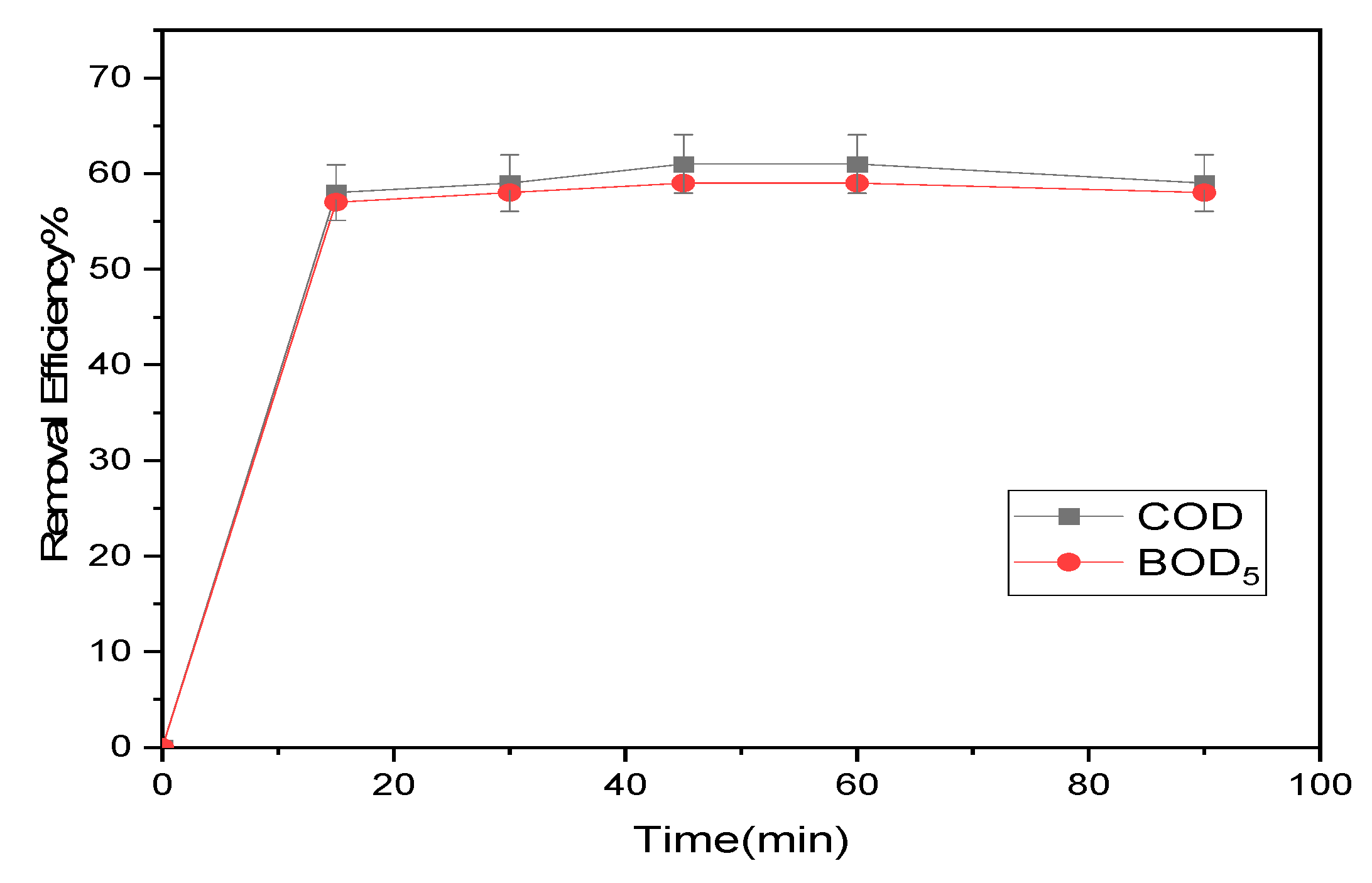

3.2.1. Impacts of contact duration

The influence of contact time on the efficiency of BOD

5 and COD removal was initially tested for 177 and 56.5 mg/L, respectively, at times (15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min) with 1 g of magnetite NPs due to the significance of contact time on the reduction of COD and BOD

5 by magnetite. The pH of the contaminated water was kept at 8, stirring occurred at approximately 200 rpm, and the ambient temperature was maintained at 20±1 °C. The results obtained showed a high level of COD and BOD

5 removal reaching 61% within 50 minutes. This implies that in order to achieve optimal efficiency, the contact time should be set to a minimum of 50 minutes. (

Figure 7). Nevertheless, the outcomes revealed that the removal efficiency for COD and BOD

5 reached a plateau following a contact time of 50 minutes. After 60 min, the equilibrium time of treatment is attained because the absorption capacity of COD and BOD5 has remained constant. According to the study carried out Tlili et al. [

27], the impact of MNPs treatment was realized by synthesizing nanoparticles using the combustion method, with a diameter of 17 nm. It was concluded that the optimum time for achieving maximum efficiency in reducing COD and BOD

5 was 80 minutes. These results suggest that the diameter of the nanoparticles and the method of synthesis influence the time required to achieve maximum efficiency in reducing pollution, underlining the importance of these parameters in the treatment process.

3.2.2. Effect of iron oxide nanoparticles concentration

Figure 8 shows the removal efficiency of COD and BOD

5 from water contaminated with different concentrations of iron oxide nanoparticles. The results indicate that the adsorption efficiency of COD increased from 40% to 65% when the dosage of Fe

3O

4-MNP was increased from 0.5 g/L to 1.5 g/L, and that the value remained unchanged from the mass of 0.8 g/L. For BOD

5, the removal efficiency increased from 64% to 65% in the range from 0.8 g/L to 1 g/L and decreased with increasing magnetite dosage. This can be due to the fact that a rise in adsorbent dose causes a rise in the amount of nanoparticle active sites and the specific adsorption surface, which causes a significant increase in the nanoparticle molecules’ capacity for adsorption on magnetite surfaces.

3.2.3. Effect of pH

Experiments were performed in neutral acidic and alkaline media with BOD5 and COD concentrations (177 and 56.5 mg/L), pH values (4, 6, 7, 8 and 9) using 0.8 g/L. Fe3O4 NPs, contact time 50 min, stirring rate 200 rpm, and ambient temperature 25 ± 1 °C.

At equilibrium, the removal efficiencies of COD and BOD

5 were (61, 62.2, 63.4, 64.4 and 63.8%), respectively and (60.8, 63, 64.2, 65 and 64.8 %), in this order as shown

Figure 9.

The outcomes revealed that the peak removal efficiency occurred at a pH of 8, within weakly alkaline conditions. This finding is attributable to the behavior of small magnetite particles in highly acidic environments; they degrade due to the influence of acid, resulting in nanoparticles with vacant sites that affect adsorption activity. Conversely, in strongly alkaline solutions, an abundance of OH- ions can intensify the removal rate of COD and BOD5 by activating adsorption sites for negatively charged ions. Notably, numerous researchers have observed similar outcomes using varied adsorbent materials for polluted water treatment, thus highlighting the efficacy of pH = 8.

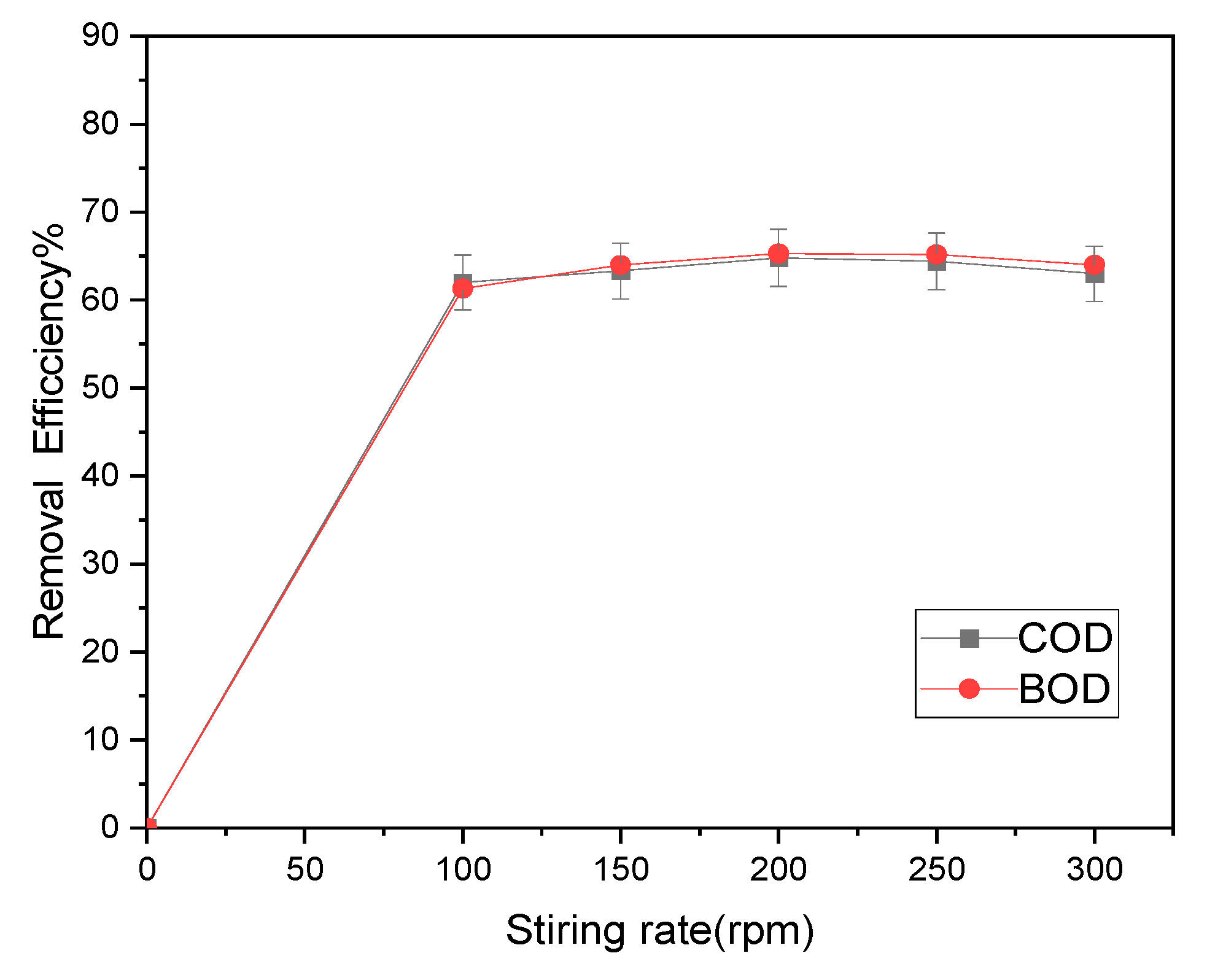

3.2.4. Impact of stirring rate

Stirring speed affects the adsorption efficiency and is a crucial parameter in the investigation of COD and BOD

5 removal. In this study, the concentration of magnetite was 0.8 g/L, pH 8, room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and stirred for 50 minutes to study the effect of stirring speed on the efficiency of removal of COD and BOD

5 under the concentration of 177 and 56.5 mg/ Lift. According to

Figure 10, the elimination efficiencies for BOD

5 and COD were, respectively, (62, 63.3, 64.8, 64.4, and 63%) and (61.3, 64, 65.3, 65.2, and 64%), respectively. According to the results, 200 rpm was the ideal stirring speed, while stirring speeds above this point may not result in increased removal efficiency.

Based on the research of the Tlili et al. [

27] , it was found that a stirring rate of 250 rpm is ideal for achieving the highest efficiency in reducing COD and BOD

5 levels. These findings indicate that the size of nanoparticles and the synthesis method have an impact on the time needed to reach peak pollution reduction efficiency, highlighting the significance of these factors in the treatment procedure.

3.3. Coupling adsorption and magnetic separation for the reduction of COD and BOD5

After identifying the optimal conditions for water treatment, the ideal parameters were defined as follows: a contact time of 50 minutes, a concentration of 0.8 g/L of iron oxide nanoparticles, a pH of 8, and a mixing speed of 200 rpm. Under these conditions, the treatment of polluted water using iron oxide nanoparticles (MNPs), without magnetic coupling, resulted in a significant COD reduction (64%) and a BOD5 reduction (65%).

Subsequently, additional treatment was conducted by introducing a magnetic field using an intense of 1 Tesla coupling of the nanoparticles treatments under the determined optimal conditions. The results showed a significant improvement, with a decrease on 84% COD and 85% BOD5, indicating a reduction improvement of 20%.

These findings are consistent with a study of Tlili et al. [

27], which examined the impact of MNP treatment on polluted water using magnetic coupling with a field intensity of 0.33 Tesla. The results of this study revealed a reduction on 76% COD and 78% BOD

5, confirming that the higher magnetic intensity, the more significant the reduction in contaminants.

Based on these studies, the application of a high intensity magnetic field can improve the removal of COD and BOD5 from polluted water. When magnetic fields are combined with Fe3O4 nanoparticles, removal efficiency can improve significantly. Furthermore, the specific outcomes of this investigation highlight the efficacy of magnetic nanoparticles synthesized via the co-precipitation method. The highest reduction efficiencies of 84% for COD and 85% for BOD5 were achieved after 50 min of contact time, at a pH of 8, using 1g/l of MNPs, and a stirring rate set at 200 rpm. Furthermore, the application of a magnetic field with an intensity of 1T significantly enhanced the removal efficiencies.

4. Conclusions

The coprecipitation method for synthesizing magnetite nanoparticles appears promising as an adsorbent for removing organic compounds from contaminated water. During the experiments, a significant reduction of 64% for COD and 65% for BOD5 was achieved in just 50 minutes, using optimal conditions such as a pH of 8, a concentration of magnetite nanoparticles at 0.8 g/l, and an agitation speed of 200 revolutions per minute.

However, the most significant advancement came from using a very strong magnetic field of 1 Tesla (DELTA WATER) under the same optimal conditions. This innovative approach significantly boosted the reduction efficiency, increasing it from 20% to a remarkable 84% for COD and reaching an impressive 85% for BOD5. The use of this high-intensity magnetic field opens up new possibilities in the treatment of contaminated water, highlighting its substantial potential for more effective removal of organic contaminants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T, A.E and M.F ; methodology, H.T, A.E , M.F; software, A.M and M.F; validation, H.T, A.E, M.F, K.H.N, and A.N; formal analysis H.T; investigation KHN.; resources, H.T; A.E and A.M; data curation, H.T ,A.E and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T, A.E; writing—review and editing, MF, A.E; supervision, M.F.; funding acquisition, A.M and K.H.N; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through the large group Research Program under grant number RGP 2/171/44.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Tunisia for their continuous encouragement by project of young researcher 20PJEC04-03. On the other hand we thank the company ’Delta Water’ for the devices dedicated to testing, and our sincere thanks to Prof. Ahmed Ibrahim and Prof. Sherif Ibrahim for granting the devices to perform the experimental test.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fan, L.; Xie, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Yao, D.; Li, T. Magnetically recoverable Fe3O4@polydopamine nanocomposite as an excellent co-catalyst for Fe3+ reduction in advanced oxidation processes. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2020, 92, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.H.; Zhang, T.C.; Shea, P.J.; Comfort, S.D. Effects of Oxide Coating and Selected Cations on Nitrate Reduction by Iron Metal. J. Environ. Qual. 2003, 32, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, W.X. Enhanced biological treatment of industrial wastewater with bimetallic zero-valent iron. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5384–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vicente, I.; Merino-Martos, A.; Guerrero, F.; Amores, V.; de Vicente, J. Chemical interferences when using high gradient magnetic separation for phosphate removal: Consequences for lake restoration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Qiang, Z.; Chang, J.H.; Ben, W.; Qu, J. Synthesis of carbon-coated magnetic nanocomposite (Fe3O4 at C) and its application for sulfonamide antibiotics removal from water. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2014, 26, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Chiang, Y.W.; Santos, R.M. X-ray Diffraction Techniques for Mineral Characterization: A Review for Engineers of the Fundamentals, Applications, and Research Directions. Minerals 2022. 12, 205. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Nayak, A. Cadmium removal and recovery from aqueous solutions by novel adsorbents prepared from orange peel and Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 180, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A.; Gupta, V.K. . Functionalization of tungsten oxide into MWCNT and its application for sunlight-induced degradation of rhodamine B. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 362, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meldrum, F.C.; Heywood, B.R.; Mann, S. Magnetoferritin : In Vitro Synthesis of a Novel Magnetic Protein. Science, 1992, 257, 522–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Matsunaga, T. Fully automated chemiluminescence immunoassay of insulin using antibody - Protein A - Bacterial magnetic particle complexes. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 3518–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinowski, P.; Bury, D.; Krupa, M.; Ścieżyńska, D.; Prabhu, P.; Bogacki, J. Magnetite and hematite in advanced oxidation processes application for cosmetic wastewater treatment. Processes 2020, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Cordova, A.; Silva-Gordillo, M.D.M.; Muñoz, G.A.; Arboleda-Faini, X.; Almeida Streitwieser, D. Comparison of the adsorption capacity of organic compounds present in produced water with commercially obtained walnut shell and residual biomass. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4041–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajahmadi, Z.; Younesi, H.; Bahramifar, N.; Khakpour, H.; Pirzadeh, K. Multicomponent isotherm for biosorption of Zn(II), CO(II) and Cd(II) from ternary mixture onto pretreated dried Aspergillus niger biomass. Water Resour. 2015 11, 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, K.; Ghoreyshi, A.A. Phenol removal from aqueous phase by adsorption on activated carbon prepared from paper mill sludge. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 6505–6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.R.; Ghoresyhi, A.A.; Rahimpour, A.; Younesi, H.; Pirzadeh, K. COD removal from landfill leachate using a high-performance and low-cost activated carbon synthesized from walnut shell. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2018, 205, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliwa, A.M.; Leswifi, T.Y.; Onyango, M.S.; Maity, A. Magnetic adsorption separation (MAS) process: An alternative method of extracting Cr(VI) from aqueous solution using polypyrrole coated Fe3O4 nanocomposites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 158, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.M.; Silva, J.G.; Cardoso, V.L.; De Resende, M.M. Removal and desorption of chromium in synthetic effluent by a mixed culture in a bioreactor with a magnetic field. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2020, 91, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amor, H. Ben; Elaoud, A.; Elmoueddeb, K. Influence of Magnetic Field on Water Characteristics and Potato Cultivation Influence of Magnetic Field on Water Characteristics and Potato Cultivation. Journal of Environmental and Agricultural Sciences 2018, 16, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Elaoud, A.; Turki, N.; Amor, H. Ben; Jalel, R.; Salah, N.B. Influence of the Magnetic Device on Water Quality and Production of Melon. Int. J. Curr. Engi. Tech. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Amor, H. Ben; Elaoud, A.; Hozayn, M. Does Magnetic Field Change Water pH ? Asian R. J. of Agric. 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amor, H.; Elaoud, A.; Ben Hassen, H.; Ben Salah, N.; Masmoudi, A.; Elmoueddeb, K. Characteristic study of some parameters of soil irrigated by magnetized waters. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, H.; Hozayn, M.; Elaoud, A.; Attia Abdd El-monem, A. Inference of Magnetized Water Impact on Salt-Stressed Wheat. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 4517–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, H. Ben; Elaoud, A.; Salah, N. Ben; Elmoueddeb, K. Effect of Magnetic Treatment on Surface Tension and Water Evaporation. International Journal of Advance Industrial Engineering 2017, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatamian, M.; Divband, B.; Shahi, R. Ultrasound assisted co-precipitation synthesis of Fe3O4/ bentonite nanocomposite: Performance for nitrate, BOD and COD water treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 31, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, S.S.; Khan, A.A.; Zafar, M.N.; Alhaji, M.H.; Sanaullah, K.; Shafqat, S.R.; Murtaza, S., Pang. Development of amino-functionalized silica nanoparticles for efficient and rapid removal of COD from pre-treated palm oil effluent. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesas, R.H.; Baei, M.S.; Rostami, H.; Gardy, J.; Hassanpour, A. An investigation on the capability of magnetically separable Fe3O4/mordenite zeolite for refinery oily wastewater purification. J. Environ. Manage 2019, 241, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, H.; Elaoud, A.; Asses, N.; Horchani-naifer, K.; Ferhi, M. Reduction of Oxidizable Pollutants in Waste Water from the Wadi El Bey River Basin Using Magnetic Nanoparticles as Removal Agents. Magnetochemistry 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.H.; Wu, S.H. Synthesis of nickel nanoparticles in water-in-oil microemulsions. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, T.; Chiang, K.Y.; Yu, C.C.; Yu, X.; Okuno, M.; Hunger, J.; Nagata, Y.; Bonn, M. The bending mode of water: A powerful probe for hydrogen bond structure of aqueous systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 8459–8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliramaji, S.; Zamanian, A.; Sohrabijam, Z. Characterization and Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticles by Innovative Sonochemical Method. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2015, 11, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, F.G.; Dıaz, A.N.; Peinado, M.R.; Belledone, C. Free and sol–gel immobilized alkaline phosphatase-based biosensor for the determination of pesticides and inorganic compounds. Analytica Chimica Acta 2003, 484(1), 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zeng, H.; Robinson, D.B.; Raoux, S.; Rice, P.M.; Wang, S.X.; Li, G. Monodisperse MFe2O4 ( M ) Fe, Co, Mn ) Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 4, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.W.; Chen, W.C. A disposable glucose biosensor based on drop-coating of screen-printed carbon electrodes with magnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 304, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, A.J.S.; Lee, J.; Rahman, A. Electrochemical Sensors Based on Carbon Nanotubes. Sensors 2009, 2289–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, Y.I.; Lee, C.S.; Park, J.C.; Kim, D. The enhanced anisotropic properties of the Fe3-xMxO4 (M = Fe, Co, Mn) films deposited on glass surface from aqueous solutions at low temperature. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 2003, 36, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayoom, M.; Bhat, R.; Asokan, K.; Shah, M.A.; Dar, G.N. Unary doping effect of A 2 + ( A = Zn, Co, Ni ) on the structural, electrical and magnetic properties of substituted iron oxide nanostructures. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron 2020, 31, 8268–8282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Khan, T.A.; Asim, M. Removal of arsenic from water by electrocoagulation and electrodialysis techniques. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2011, 40, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).