Submitted:

17 September 2023

Posted:

18 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

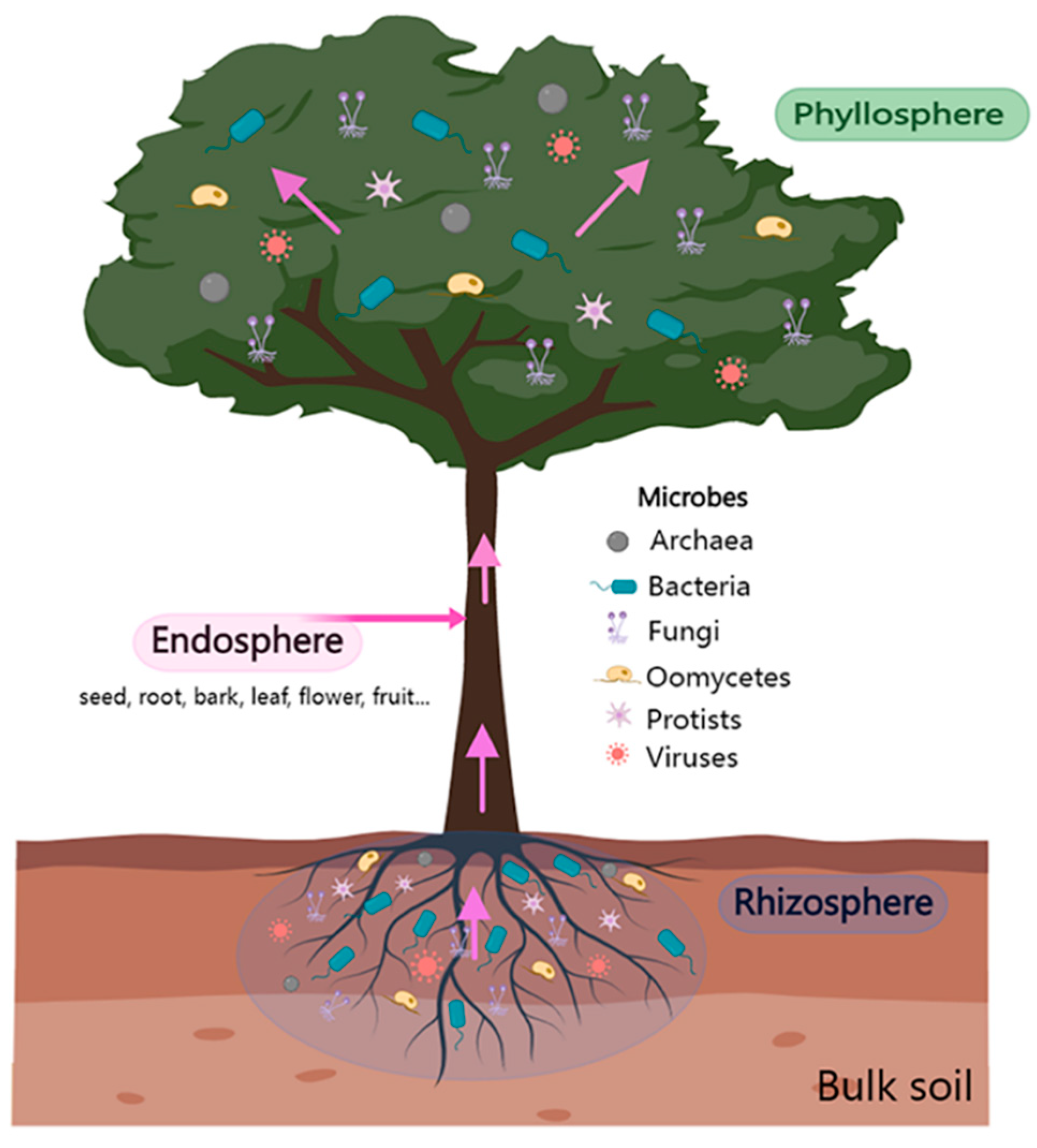

1. Introduction

2. Tree Rhizosphere Microbiome-Mediated Protection against Pathogens

2.1. Soil-Borne Pathogens and Beneficial Microbes in the Tree Rhizosphere

2.2. Root Exudates and Microbial signal Molecules Affecting Rhizosphere Microbiome of Trees

2.3. Root Microbiome Enhances Plant Disease Resistance

3. Tree Rhizosphere Microbiome-Mediated Protection against Pathogens

3.1. Multiple Factors Drive the Colonization of Microbial Aggregates on the Phylloplane

3.2. Stability of Microbial Consortia against Pathogen Perturbation

3.3. Phyllosphere-Mediated Resistance to Pathogen Invasion

4. Contribution of Tree Endosphere Microbiome in the Control of Forest Diseases

5. Pathogen Invasion Triggers Innate Immune Responses in Plants

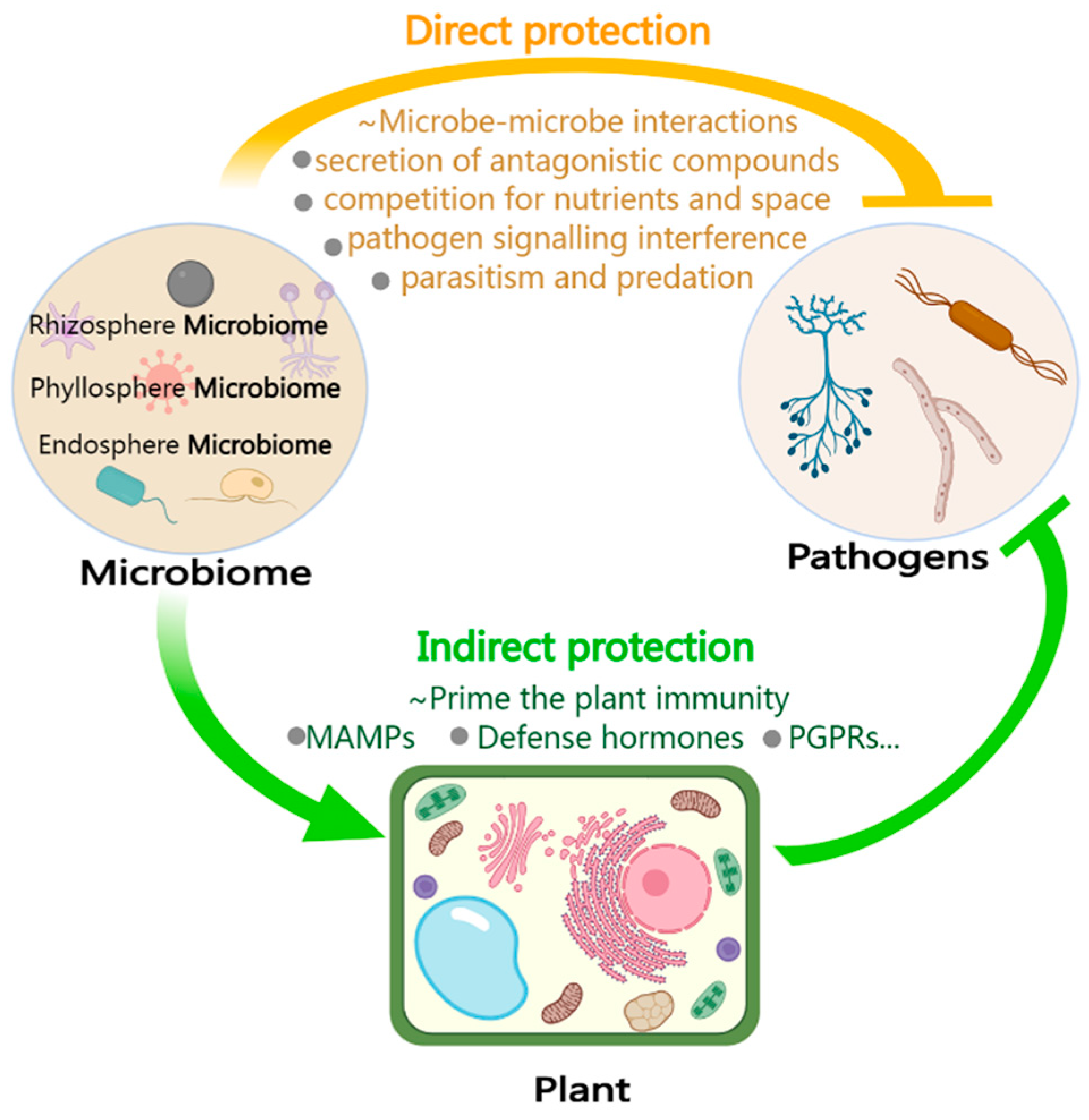

6. The Microbiome Enhances Plant Immunity and Functions as an Extension of the Plant Immune System

6.1. Acting Directly against Pathogens: Direct Interaction between Microbes

6.2. Acting Indirectly against Pathogens: Stimulating or Inducing Plant Immunity

7. Future Perspectives: Integrating Tree-Pathogen-Microbiome Interactions into Forest Pest Management

7.1. The Challenges of Applying BCAs in Protecting Trees

7.2. The Advantages in Tree Pathogen Inhibition by Multi-Strain BCAs over Single-strain bcas

7.3. Microbial Interactions Promote Rhizosphere Colonization

7.4. Microbial Interactions Suppress Forest Pathogen Growth

7.5. Microbial Interactions Induce Enhanced Plant Defense Responses to Pathogens

7.6. Future Perspectives of Applying BCAs in Protecting Trees

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bettenfeld, P.; Fontaine, F.; Trouvelot, S.; Fernandez, O.; Courty, P.-E. Woody plant declines. what’s wrong with the microbiome? Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vettraino, A.; Morel, O.; Perlerou, C.; Robin, C.; Diamandis, S.; Vannini, A. Occurrence and distribution of Phytophthora species in European chestnut stands, and their association with Ink Disease and crown decline. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2005, 111, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigling, D.; Prospero, S. Cryphonectria parasitica, the causal agent of chestnut blight: Invasion history, population biology and disease control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasier, C.M. Rapid evolution of introduced plant pathogens via interspecific hybridization: Hybridization is leading to rapid evolution of Dutch elm disease and other fungal plant pathogens. Bioscience 2001, 51, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, N.J.; Garbelotto, M.; Goss, E.M.; Heungens, K.; Prospero, S. Emergence of the sudden oak death pathogen Phytophthora Ramorum. Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futai, K. Pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, T.C.; Yun, H.Y.; Lu, S.-S.; Goto, H.; Aghayeva, D.N.; Fraedrich, S.W. Isolations from the redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus, confirm that the laurel wilt pathogen, Raffaelea lauricola, originated in Asia. Mycologia 2011, 103, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturrock, R.; Frankel, S.; Brown, A.; Hennon, P.; Kliejunas, J.; Lewis, K.; Worrall, J.; Woods, A. Climate change and forest diseases. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospero, S.; Cleary, M. Effects of host variability on the spread of invasive forest diseases. Forests 2017, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdenrieder, O.; Pautasso, M.; Weisberg, P.J.; Lonsdale, D. Tree diseases and landscape processes: The challenge of landscape pathology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-N.; Ren, M.; Zhan, J. Modeling plant diseases under climate change: Evolutionary perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jia, H. Metagenome-wide association studies: Fine-mining the microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, R.; Jumpponen, A.; Schlatter, D.C.; Paulitz, T.; Gardener, B.M.; Kinkel, L.L.; Garrett, K. Microbiome networks: A systems framework for identifying candidate microbial assemblages for disease management. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heijden, M.G.; Hartmann, M. Networking in the plant microbiome. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babalola, O.O. Beneficial bacteria of agricultural importance. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Schlaeppi, K.; Spaepen, S.; Van Themaat, E.V.L.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospero, S.; Botella, L.; Santini, A.; Robin, C. Biological control of emerging forest diseases: How can we move from dreams to reality? For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Jia, J.; He, C.; Zeng, L.; Fang, Y.; Qiu, G.; Lan, X.; Su, J.; He, X. Multi-omics of pine wood nematode pathogenicity associated with culturable associated microbiota through an artificial assembly approach. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corinne, V.; Bastien, C.; Emmanuelle, J.; Heidy, S. Trees and Insects Have Microbiomes: Consequences for Forest Health and Management. Curr. For. Rep. 2021, 7, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiegbu, F.O. Chapter 22 - Forest microbiome: Challenges and future perspectives. In Forest Microbiology; Asiegbu, F.O., Kovalchuk, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D.J.; Hoke, A.J.; Koch, J. The emergence of beech leaf disease in Ohio: Probing the plant microbiome in search of the cause. Forest Pathol. 2020, 50, e12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zi, H.; Sonne, C.; Li, X. Microbiome sustains forest ecosystem functions across hierarchical scales. Eco-Environ. Health 2023, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: Diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiegbu, F.O.; Kovalchuk, A. Forest Microbiology: Volume 1: Tree Microbiome: Phyllosphere, Endosphere and Rhizosphere; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov, Y. Factors affecting rhizosphere priming effects. J. Plant Nutr. Soil. Sci. 2002, 165, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsinger, P.; Bengough, A.G.; Vetterlein, D.; Young, I.M. Rhizosphere: Biophysics, biogeochemistry and ecological relevance. Plant Soil. 2009, 321, 117–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.M. Phytophthora species emerging as pathogens of forest trees. Curr. For. Rep. 2015, 1, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, T.A.; Wingfield, M.J. Ralstonia solanacearum and R. pseudosolanacearum on Eucalyptus: Opportunists or Primary Pathogens? Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, P.; Liao, F.; Weng, Q.; Chen, Q. First report of bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum on fig trees in China. For. Pathol. 2016, 46, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, J.; Wingfield, M. Ceratocystis species: Emerging pathogens of non-native plantation Eucalyptus and Acacia species. South. For. A J. For. Sci. 2009, 71, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, I.; Roux, J.; Wingfield, B.; O’Neill, M.; Wingfield, M. Ceratocystis fimbriata infecting Eucalyptus grandis in Uruguay. Australas Plant Pathol. 2003, 32, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markakis, E.A.; Tjamos, S.E.; Antoniou, P.P.; Paplomatas, E.J.; Tjamos, E.C. Biological control of Verticillium wilt of olive by Paenibacillus alvei, strain K165. BioControl 2016, 61, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, C. Quantitative detection of pathogen DNA of Verticillium wilt on smoke tree Cotinus coggygria. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.; Hiemstra, J. A Compendium of Verticillium Wilts in Tree Species; Ponsen and Looijen: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hrynkiewicz, K.; Baum, C. The Potential of Rhizosphere Microorganisms to Promote the Plant Growth in Disturbed Soils; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Karaki, G.N. The Role of Mycorrhiza in the Reclamation of Degraded Lands in Arid Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 823–836. [Google Scholar]

- Khabou, W.; Hajji, B.; Zouari, M.; Rigane, H.; Abdallah, F.B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve growth and mineral uptake of olive tree under gypsum substrate. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 73, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaut, N.; Sanguin, H.; Ouahmane, L.; Bressan, M.; Thioulouse, J.; Baudoin, E.; Galiana, A.; Hafidi, M.; Prin, Y.; Duponnois, R. Potentialities of ecological engineering strategy based on native arbuscular mycorrhizal community for improving afforestation programs with carob trees in degraded environments. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 79, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A. Biological control of crown gall. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2016, 45, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, P.; Navarro-Raya, C.; Valverde-Corredor, A.; Amyotte, S.G.; Dobinson, K.F.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Colonization process of olive tissues by Verticillium dahliae and its in planta interaction with the biocontrol root endophyte Pseudomonas fluorescens PICF7. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, P.M.; Ruano-Rosa, D.; Schilirò, E.; Prieto, P.; Ramos, C.; Rodríguez-Palenzuela, P.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain PICF7, an indigenous root endophyte from olive (Olea europaea L.) and effective biocontrol agent against Verticillium dahliae. Stand. Genomic Sci. 2015, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wook eYang, J. ISR meets SAR outside: Additive action of the endophyte Bacillus pumilus INR7 and the chemical inducer, benzothiadiazole, on induced resistance against bacterial spot in field-grown pepper. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, H.P.; Weir, T.L.; Perry, L.G.; Gilroy, S.; Vivanco, J.M. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, J.; Martinoia, E.; Northen, T. Feed your friends: Do plant exudates shape the root microbiome? Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; Louie, K.B.; Hao, Z.; Mansoori, N.; da Rocha, U.N.; Shi, S.; Cho, H.; Karaoz, U.; Loqué, D.; Bowen, B.P. Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Robert, C.A.; Cadot, S.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Li, B.; Manzo, D.; Chervet, N.; Steinger, T.; Van Der Heijden, M.G. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetz, U.; Martinoia, E. Root exudates: The hidden part of plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrappa, T.; Czymmek, K.J.; Paré, P.W.; Bais, H.P. Root-secreted malic acid recruits beneficial soil bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeis, S.L.; Paredes, S.H.; Lundberg, D.S.; Breakfield, N.; Gehring, J.; McDonald, M.; Malfatti, S.; Glavina del Rio, T.; Jones, C.D.; Tringe, S.G. Salicylic acid modulates colonization of the root microbiome by specific bacterial taxa. Science 2015, 349, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of different plant root exudates and their organic acid components on chemotaxis, biofilm formation and colonization by beneficial rhizosphere-associated bacterial strains. Plant Soil. 2014, 374, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Pei, Y.; Huang, W.; Ding, J.; Siemann, E. Increasing flavonoid concentrations in root exudates enhance associations between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and an invasive plant. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Liu, W.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y. The root microbiome: Community assembly and its contributions to plant fitness. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jaramillo, J.E.; Mendes, R.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Impact of plant domestication on rhizosphere microbiome assembly and functions. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, J.M.; Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Rhizosphere microbiome assemblage is affected by plant development. ISME J. 2014, 8, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmink, J.; Nazir, R.; Corten, B.; Van Elsas, J. Hitchhikers on the fungal highway: The helper effect for bacterial migration via fungal hyphae. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeier, S.; Smits, T.H.; Ford, R.M.; Keel, C.; Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y. Taking the fungal highway: Mobilization of pollutant-degrading bacteria by fungi. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 4640–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriuso, J.; Ramos Solano, B.; Fray, R.G.; Cámara, M.; Hartmann, A.; Gutiérrez Mañero, F.J. Transgenic tomato plants alter quorum sensing in plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, S.T.; Schikora, A. AHL-priming functions via oxylipin and salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitas, V.; Kim, H.-S.; Bennett, J.W.; Kang, S. Sniffing on microbes: Diverse roles of microbial volatile organic compounds in plant health. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Cordovez, V.; De Boer, W.; Raaijmakers, J.; Garbeva, P. Volatile affairs in microbial interactions. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrain, B.; Farag, M.A.; Ryu, C.-M.; Ghigo, J.-M. Role of bacterial volatile compounds in bacterial biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 39, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosetta, C.M.; Wolfe, B.E. Causes and consequences of biotic interactions within microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. The phyllosphere microbiome shifts toward combating melanose pathogen. Microbiome 2022, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, S.A.; Griffiths, J.; Ton, J. Crying out for help with root exudates: Adaptive mechanisms by which stressed plants assemble health-promoting soil microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, V.J.; Perez-Jaramillo, J.; Cordovez, V.; Tracanna, V.; De Hollander, M.; Ruiz-Buck, D.; Mendes, L.W.; van Ijcken, W.F.; Gomez-Exposito, R.; Elsayed, S.S. Pathogen-induced activation of disease-suppressive functions in the endophytic root microbiome. Science 2019, 366, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokalis-Burelle, N.; McSorley, R.; Wang, K.-H.; Saha, S.K.; McGovern, R.J. Rhizosphere microorganisms affected by soil solarization and cover cropping in Capsicum annuum and Phaseolus lunatus agroecosystems. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2017, 119, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalla, K.; Wieland, G.; Buchner, A.; Zock, A.; Parzy, J.; Kaiser, S.; Roskot, N.; Heuer, H.; Berg, G. Bulk and rhizosphere soil bacterial communities studied by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis: Plant-dependent enrichment and seasonal shifts revealed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4742–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado-Blanco, J.; Abrantes, I.; Barra Caracciolo, A.; Bevivino, A.; Ciancio, A.; Grenni, P.; Hrynkiewicz, K.; Kredics, L.; Proença, D.N. Belowground microbiota and the health of tree crops. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Rahman, S.F.S.; Singh, E.; Pieterse, C.M.; Schenk, P.M. Emerging microbial biocontrol strategies for plant pathogens. Plant Sci. 2018, 267, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zi, H.; Zhu, H.; Liao, Y.; Li, X. Rhizosphere microbiome of forest trees determines their resistance to soil-borne pathogens. Reserch Square. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorholt, J.A. Microbial life in the phyllosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindow, S.E.; Brandl, M.T. Microbiology of the phyllosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.W.; Weingarten, E.A.; Jackson, C.R. The role of the phyllosphere microbiome in plant health and function. Annu. Plant Rev. Online 2018, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapp, M.; Ploch, S.; Fiore-Donno, A.M.; Bonkowski, M.; Rose, L.E. Protists are an integral part of the Arabidopsis thaliana microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, B.; Nga, N.T.T.; Jones, J.B. Relative level of bacteriophage multiplication in vitro or in phyllosphere may not predict in planta efficacy for controlling bacterial leaf spot on tomato caused by Xanthomonas perforans. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritpitakphong, U.; Falquet, L.; Vimoltust, A.; Berger, A.; Métraux, J.P.; L'Haridon, F. The microbiome of the leaf surface of Arabidopsis protects against a fungal pathogen. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Zhu, Y.G.; Wang, J.T.; Singh, B.; Han, L.L.; Shen, J.P.; Li, P.P.; Wang, G.B.; Wu, C.F.; Ge, A.H. Host selection shapes crop microbiome assembly and network complexity. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, N.; Horton, M.W.; Bergelson, J. Bacterial communities associated with the leaves and the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e56329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maignien, L.; DeForce, E.A.; Chafee, M.E.; Eren, A.M.; Simmons, S.L. Ecological succession and stochastic variation in the assembly of Arabidopsis thaliana phyllosphere communities. mBio 2014, 5, e00682–00613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Müller, D.B.; Srinivas, G.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Potthoff, E.; Rott, M.; Dombrowski, N.; Münch, P.C.; Spaepen, S.; Remus-Emsermann, M. Functional overlap of the Arabidopsis leaf and root microbiota. Nature 2015, 528, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Ruppel, S. Progress in cultivation-independent phyllosphere microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 87, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, J.A.; Spor, A.; Koren, O.; Jin, Z.; Tringe, S.G.; Dangl, J.L.; Buckler, E.S.; Ley, R.E. Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6548–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmotte, N.; Knief, C.; Chaffron, S.; Innerebner, G.; Roschitzki, B.; Schlapbach, R.; von Mering, C.; Vorholt, J.A. Community proteogenomics reveals insights into the physiology of phyllosphere bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16428–16433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knief, C.; Delmotte, N.; Chaffron, S.; Stark, M.; Innerebner, G.; Wassmann, R.; Von Mering, C.; Vorholt, J.A. Metaproteogenomic analysis of microbial communities in the phyllosphere and rhizosphere of rice. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izhaki, I.; Fridman, S.; Gerchman, Y.; Halpern, M. Variability of bacterial community composition on leaves between and within plant species. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 66, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inácio, J.; Pereira, P.; Carvalho, d.M.; Fonseca, A.; Amaral-Collaco, M.; Spencer-Martins, I. Estimation and diversity of phylloplane mycobiota on selected plants in a mediterranean–type ecosystem in Portugal. Microb. Ecol. 2002, 44, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kembel, S.W.; O’Connor, T.K.; Arnold, H.K.; Hubbell, S.P.; Wright, S.J.; Green, J.L. Relationships between phyllosphere bacterial communities and plant functional traits in a neotropical forest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13715–13720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.M.; Galambao, M.; Rowntree, J.; Goodhead, I.; Hall, J.; O’Brien, D.; Atkinson, N.; Antwis, R.E. Complex associations between cross-kingdom microbial endophytes and host genotype in ash dieback disease dynamics. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, K.; Becker, R.; Behrendt, U.; Kube, M.; Ulrich, A. A comparative analysis of ash leaf-colonizing bacterial communities identifies putative antagonists of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.; Maillard, F.; Alvarez-Lopez, V.; Guinchard, S.; Bertheau, C.; Valot, B.; Blaudez, D.; Chalot, M. Bacterial diversity associated with poplar trees grown on a Hg-contaminated site: Community characterization and isolation of Hg-resistant plant growth-promoting bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, A.J.; Bowers, R.M.; Knight, R.; Linhart, Y.; Fierer, N. The ecology of the phyllosphere: Geographic and phylogenetic variability in the distribution of bacteria on tree leaves. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 2885–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, J.W.; Jones, S.E.; Prober, S.M.; Barberán, A.; Borer, E.T.; Firn, J.L.; Harpole, W.S.; Hobbie, S.E.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Knops, J.M. Consistent responses of soil microbial communities to elevated nutrient inputs in grasslands across the globe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10967–10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarraonaindia, I.; Owens, S.M.; Weisenhorn, P.; West, K.; Hampton-Marcell, J.; Lax, S.; Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A.; Martin, G.; Taghavi, S. The soil microbiome influences grapevine-associated microbiota. mBio 2015, 6, e02527–e02514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, J.K.; Yuan, L.; Layeghifard, M.; Wang, P.W.; Guttman, D.S. Seasonal community succession of the phyllosphere microbiome. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, O.M.; Burch, A.Y.; Lindow, S.E.; Post, A.F.; Belkin, S. Geographical location determines the population structure in phyllosphere microbial communities of a salt-excreting desert tree. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7647–7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, O.M.; Burch, A.Y.; Elad, T.; Huse, S.M.; Lindow, S.E.; Post, A.F.; Belkin, S. Distance-decay relationships partially determine diversity patterns of phyllosphere bacteria on Tamrix trees across the Sonoran Desert. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6187–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Messier, C.; Kembel, S.W. Host species identity, site and time drive temperate tree phyllosphere bacterial community structure. Microbiome 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, T.; Robin, C.; Capdevielle, X.; Desprez-Loustau, M.-L.; Vacher, C. Spatial variability of phyllosphere fungal assemblages: Genetic distance predominates over geographic distance in a European beech stand (Fagus sylvatica). Fungal Ecol. 2012, 5, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Maynard, Z.; Gilbert, G.S.; Coley, P.D.; Kursar, T.A. Are tropical fungal endophytes hyperdiverse? Ecol. Lett. 2000, 3, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.L.; Kour, D.; Sheikh, I.; Dhiman, A.; Yadav, N.; Yadav, A.N.; Rastegari, A.A.; Singh, K.; Saxena, A.K. Endophytic fungi: Biodiversity, ecological significance, and potential industrial applications. In Recent Advancement in White Biotechnology through Fungi; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault, R.; Laforest-Lapointe, I. Plant-microbe interactions in the phyllosphere: Facing challenges of the anthropocene. ISME J. 2022, 16, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Xiong, C.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Q.L.; Ma, B.; Zhou, S.Y.D.; Tan, J.; Zhang, L.M.; Cui, H.L.; Duan, G.L. Impacts of global change on the phyllosphere microbiome. New Phytol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpponen, A.; Jones, K. Massively parallel 454 sequencing indicates hyperdiverse fungal communities in temperate Quercus macrocarpa phyllosphere. New Phytol. 2009, 184, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balint, M.; Bartha, L.; O'Hara, R.B.; Olson, M.S.; Otte, J.; Pfenninger, M.; Robertson, A.L.; Tiffin, P.; Schmitt, I. Relocation, high-latitude warming and host genetic identity shape the foliar fungal microbiome of poplars. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balint, M.; Tiffin, P.; Hallstroem, B.; O'Hara, R.B.; Olson, M.S.; Fankhauser, J.D.; Piepenbring, M.; Schmitt, I. Host genotype shapes the foliar fungal microbiome of balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera). PLoS ONE. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, A.; Salas Gonzalez, I.; Mittelviefhaus, M.; Clingenpeel, S.; Herrera Paredes, S.; Miao, J.; Wang, K.; Devescovi, G.; Stillman, K.; Monteiro, F. Genomic features of bacterial adaptation to plants. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junker, R.R.; Tholl, D. Volatile organic compound mediated interactions at the plant-microbe interface. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 810–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosoveanu, A.; Gimenez-Mariño, C.; Cabrera, Y.; Hernandez, G.; Cabrera, R. Endophytic fungi from grapevine cultivars in Canary Islands and their activity against phytopatogenic fungi. Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 2014, 7, 1497. [Google Scholar]

- Balint-Kurti, P.; Simmons, S.J.; Blum, J.E.; Ballaré, C.L.; Stapleton, A.E. Maize leaf epiphytic bacteria diversity patterns are genetically correlated with resistance to fungal pathogen infection. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinska, P.; Wypij, M.; Agarkar, G.; Rathod, D.; Dahm, H.; Rai, M. Endophytic actinobacteria of medicinal plants: Diversity and bioactivity. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, S.; Prasanna, R. Prospecting the characteristics and significance of the phyllosphere microbiome. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Sabri, A.; Ljung, K.; Hasnain, S. Auxin production by plant associated bacteria: Impact on endogenous IAA content and growth of Triticum aestivum L. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 48, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, A.Y.; Zeisler, V.; Yokota, K.; Schreiber, L.; Lindow, S.E. The hygroscopic biosurfactant syringafactin produced by Pseudomonas syringae enhances fitness on leaf surfaces during fluctuating humidity. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 2086–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoim, P.R.; Van Overbeek, L.S.; Berg, G.; Pirttilä, A.M.; Compant, S.; Campisano, A.; Döring, M.; Sessitsch, A. The hidden world within plants: Ecological and evolutionary considerations for defining functioning of microbial endophytes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Nomura, K.; Wang, X.; Sohrabi, R.; Xu, J.; Yao, L.; Paasch, B.C.; Ma, L.; Kremer, J.; Cheng, Y. A plant genetic network for preventing dysbiosis in the phyllosphere. Nature 2020, 580, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, P.A.; Pieterse, C.M.; de Jonge, R.; Berendsen, R.L. The soil-borne legacy. Cell 2018, 172, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, J.; Carvalhais, L.C.; Percy, C.D.; Prakash Verma, J.; Schenk, P.M.; Singh, B.K. Evidence for the plant recruitment of beneficial microbes to suppress soil-borne pathogens. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2873–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordovez, V.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Carrión, V.J.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Ecology and evolution of plant microbiomes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzke, F.; Thiergart, T.; Hacquard, S. Contribution of bacterial-fungal balance to plant and animal health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Casa Vargas, J.M.; Schlatter, D.C.; Hagerty, C.H.; Hulbert, S.H.; Paulitz, T.C. Rhizosphere community selection reveals bacteria associated with reduced root disease. Microbiome 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.-J.; Kong, H.G.; Choi, K.; Kwon, S.-K.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, P.A.; Choi, S.Y.; Seo, M.; Lee, H.J. Rhizosphere microbiome structure alters to enable wilt resistance in tomato. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.; Koskella, B. Nutrient-and dose-dependent microbiome-mediated protection against a plant pathogen. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2487–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakuschkin, B.; Fievet, V.; Schwaller, L.; Fort, T.; Robin, C.; Vacher, C. Deciphering the pathobiome: Intra-and interkingdom interactions involving the pathogen Erysiphe alphitoides. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 72, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginnan, N.A.; Dang, T.; Bodaghi, S.; Ruegger, P.M.; McCollum, G.; England, G.; Vidalakis, G.; Borneman, J.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Roper, M.C. Disease-induced microbial shifts in citrus indicate microbiome-derived responses to huanglongbing across the disease severity spectrum. Phytobiomes J. 2020, 4, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-D.; Zhu, Z.-R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. The phyllosphere microbiome shifts toward combating melanose pathogen. Microbiome 2022, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brader, G.; Compant, S.; Vescio, K.; Mitter, B.; Trognitz, F.; Ma, L.-J.; Sessitsch, A. Ecology and genomic insights into plant-pathogenic and plant-nonpathogenic endophytes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyee, B.; Pornsuriya, C.; Ito, S.-i.; Sunpapao, A. Trichoderma spirale T76-1 displays biocontrol activity against leaf spot on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) caused by Corynespora cassiicola or Curvularia aeria. Biol. Control. 2019, 129, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loc, N.H.; Huy, N.D.; Quang, H.T.; Lan, T.T.; Thu Ha, T.T. Characterisation and antifungal activity of extracellular chitinase from a biocontrol fungus, Trichoderma asperellum PQ34. Mycology 2020, 11, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Pandey, K.D. Endophytic bacteria: A new source of bioactive compounds. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, M.T.; Mostafa, A.A.-F.; Al-Askar, A.A.; Sayed, S.R.; Rady, A.M. Antagonistic activity of Trichoderma harzianum and Trichoderma viride strains against some fusarial pathogens causing stalk rot disease of maize, in vitro. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest. Co. 2021, 33, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Khan, R.A.A. Biological control of bacterial wilt in tomato through the metabolites produced by the biocontrol fungus, Trichoderma harzianum. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest. Co. 2021, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, A.; Nita, M.; Ishii, T.; Watanabe, M.; Noutoshi, Y. Biological control agent Rhizobium (= Agrobacterium) vitis strain ARK-1 suppresses expression of the essential and non-essential vir genes of tumorigenic R. vitis. BMC Res. Notes. 2019, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Tao, Y.; Tao, X.; Su, Q.; Cai, J.; Qin, C.; Ding, W.; Li, C. Sesquiterpenes with phytopathogenic fungi inhibitory activities from fungus Trichoderma virens from Litchi chinensis Sonn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 10646–10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, A.A. Endophytes: Colonization, behaviour, and their role in defense mechanism. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, L.C.; Herre, E.A.; Sparks, J.P.; Winter, K.; García, M.N.; Van Bael, S.A.; Stitt, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guiltinan, M.J. Pervasive effects of a dominant foliar endophytic fungus on host genetic and phenotypic expression in a tropical tree. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, T.; Nan, Z.; Li, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus alleviates alfalfa leaf spots caused by Phoma medicaginis revealed by RNA-seq analysis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, P.E.; Peay, K.G.; Newcombe, G. Common foliar fungi of Populus trichocarpa modify Melampsora rust disease severity. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.H.; Ye, J.R.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.L.; Wu, X.Q. Isolation and characterization of a new Burkholderia pyrrocinia strain JK-SH007 as a potential biocontrol agent. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 2203–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanney, J.B.; McMullin, D.R.; Green, B.D.; Miller, J.D.; Seifert, K.A. Production of antifungal and antiinsectan metabolites by the Picea endophyte Diaporthe maritima sp. nov. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarah, M.W.; Kesting, J.R.; Sørensen, D.; Miller, J.D. Antifungal metabolites from fungal endophytes of Pinus strobus. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1833–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarah, M.W.; Walker, A.K.; Seifert, K.A.; Todorov, A.; Miller, J.D. Screening of fungal endophytes isolated from eastern white pine needles. In The Formation, Structure and Activity of Phytochemicals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Segaran, G.; Sathiavelu, M. Fungal endophytes: A potent biocontrol agent and a bioactive metabolites reservoir. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Emonet, A.; Dénervaud Tendon, V.; Marhavy, P.; Wu, D.; Lahaye, T.; Geldner, N. Co-incidence of damage and microbial patterns controls localized immune responses in roots. Cell 2020, 180, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacquard, S.; Spaepen, S.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Interplay between innate immunity and the plant microbiota. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017, 55, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, J.; Dai, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Shi, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, E. Discriminating symbiosis and immunity signals by receptor competition in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023738118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.; Bakker, P.A. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, P.A.; Berendsen, R.L.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Vismans, G.; Yu, K.; Li, E.; Van Bentum, S.; Poppeliers, S.W.; Gil, J.J.S.; Zhang, H. The soil-borne identity and microbiome-assisted agriculture: Looking back to the future. Mol. Plant. 2020, 13, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G.J.; Flors, V.; García-Agustín, P.; Jakab, G.; Mauch, F.; Newman, M.-A.; Pieterse, C.M.; Poinssot, B.; Pozo, M.J. Priming: Getting ready for battle. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, V.; Johnson, K.; Sugar, D.; Loper, J. Antibiosis contributes to biological control of fire blight by Pantoea agglomerans strain Eh252 in orchards. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusey, P.; Stockwell, V.; Reardon, C.; Smits, T.; Duffy, B. Antibiosis activity of Pantoea agglomerans biocontrol strain E325 against Erwinia amylovora on apple flower stigmas. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Shao, J.; Li, B.; Yan, X.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Contribution of bacillomycin D in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 to antifungal activity and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Qiu, M.; Feng, H.; Zhang, N.; Shen, Q. Enhanced control of cucumber wilt disease by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 by altering the regulation of its DegU phosphorylation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, R.; Ruan, Y.; Shen, Q. Effects of novel bioorganic fertilizer produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens W19 on antagonism of Fusarium wilt of banana. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2013, 49, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Raza, W.; Shen, Q.; Huang, Q. Antifungal activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NJN-6 volatile compounds against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5942–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piewngam, P.; Zheng, Y.; Nguyen, T.H.; Dickey, S.W.; Joo, H.-S.; Villaruz, A.E.; Glose, K.A.; Fisher, E.L.; Hunt, R.L.; Li, B. Pathogen elimination by probiotic Bacillus via signalling interference. Nature 2018, 562, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Xie, J.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, B.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, P.; Barbetti, M.J. A cosmopolitan fungal pathogen of dicots adopts an endophytic lifestyle on cereal crops and protects them from major fungal diseases. ISME J. 2020, 14, 3120–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Miao, Y.; Rahimi, M.J.; Zhu, H.; Steindorff, A.; Schiessler, S.; Cai, F.; Pang, G.; Chenthamara, K.; Xu, Y. Guttation capsules containing hydrogen peroxide: An evolutionarily conserved NADPH oxidase gains a role in wars between related fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 2644–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bayram Akcapinar, G.; Atanasova, L.; Rahimi, M.J.; Przylucka, A.; Yang, D.; Kubicek, C.P.; Zhang, R.; Shen, Q.; Druzhinina, I.S. The neutral metallopeptidase NMP1 of Trichoderma guizhouense is required for mycotrophy and self-defence. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Jiao, S.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, G. A simplified synthetic community rescues Astragalus mongholicus from root rot disease by activating plant-induced systemic resistance. Microbiome 2021, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Vismans, G.; Yu, K.; Song, Y.; De Jonge, R.; Burgman, W.P.; Burmølle, M.; Herschend, J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Disease-induced assemblage of a plant-beneficial bacterial consortium. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhao, J.; Wen, T.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Goossens, P.; Huang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Vivanco, J.M.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Root exudates drive the soil-borne legacy of aboveground pathogen infection. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.; Garrett, K.; Bockus, W. Meeting the challenge of disease management in perennial grain cropping systems. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Blanco, J.; JJ Lugtenberg, B. Biotechnological applications of bacterial endophytes. Curr. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautasso, M.; Schlegel, M.; Holdenrieder, O. Forest health in a changing world. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 826–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzola, M.; Freilich, S. Prospects for biological soilborne disease control: Application of indigenous versus synthetic microbiomes. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, B.K.; Yadav, S.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, H.B. Microbial consortium-mediated plant defense against phytopathogens: Readdressing for enhancing efficacy. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2015, 87, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorholt, J.A.; Vogel, C.; Carlström, C.I.; Müller, D.B. Establishing causality: Opportunities of synthetic communities for plant microbiome research. Cell Host Microbe. 2017, 22, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.L.; Pepe, O. Microbial consortia: Promising probiotics as plant biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-García, L.F.; González-Almario, A.; Cotes, A.M.; Moreno-Velandia, C.A. Trichoderma virens Gl006 and Bacillus velezensis Bs006: A compatible interaction controlling Fusarium wilt of cape gooseberry. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.F.; Saidi, N.B.; Vadamalai, G.; Teh, C.Y.; Zulperi, D. Effect of bioformulations on the biocontrol efficacy, microbial viability and storage stability of a consortium of biocontrol agents against Fusarium wilt of banana. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.A.; Durán, P.; Hacquard, S. Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome 2018, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, R.; Menezes, R.C.; Grabe, V.; Li, D.; Baldwin, I.T.; Groten, K. A suite of complementary biocontrol traits allows a native consortium of root-associated bacteria to protect their host plant from a fungal sudden-wilt disease. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 1154–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechty, Z.; Santos-Medellín, C.; Edwards, J.; Nguyen, B.; Mikhail, D.; Eason, S.; Phillips, G.; Sundaresan, V. Comparative analysis of root microbiomes of rice cultivars with high and low methane emissions reveals differences in abundance of methanogenic archaea and putative upstream fermenters. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeier, S.; Smits, T.H.M.; Ford, R.M.; Keel, C.; Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y. Taking the fungal highway: mobilization of pollutant-degrading bacteria by fungi. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 4640–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmink, J.A.; Nazir, R.; Corten, B.; van Elsas, J.D. Hitchhikers on the fungal highway: The helper effect for bacterial migration via fungal hyphae. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, T.; Friman, V.-P.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Jousset, A. Trophic network architecture of root-associated bacterial communities determines pathogen invasion and plant health. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wei, Z.; Friman, V.-P.; Gu, S.-h.; Wang, X.-f.; Eisenhauer, N.; Yang, T.-j.; Ma, J.; Shen, Q.-r.; Xu, Y.-c.; et al. Probiotic diversity enhances rhizosphere microbiome function and plant disease suppression. mBio 2016, 7, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Wei, Z.; Shao, Z.; Friman, V.-P.; Cao, K.; Yang, T.; Kramer, J.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Mei, X.; et al. Competition for iron drives phytopathogen control by natural rhizosphere microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traxler, M.F.; Watrous, J.D.; Alexandrov, T.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Kolter, R. Interspecies interactions stimulate diversification of the Streptomyces coelicolor secreted metabolome. mBio 2013, 4, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola, A.R.B.; Thomy, D.; Lai, D.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Proksch, P. Inducing secondary metabolite production by the endophytic fungus Fusarium tricinctum through coculture with Bacillus subtilis. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 2094–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishchany, G.; Mevers, E.; Ndousse-Fetter, S.; Horvath, D.J.; Paludo, C.R.; Silva-Junior, E.A.; Koren, S.; Skaar, E.P.; Clardy, J.; Kolter, R. Amycomicin is a potent and specific antibiotic discovered with a targeted interaction screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10124–10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar Sarma, B.; Bahadur Singh, H. Microbial consortium–mediated reprogramming of defence network in pea to enhance tolerance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Behboudi, K.; Ahmadzadeh, M.; Javan-Nikkhah, M.; Zamioudis, C.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced systemic resistance in cucumber and Arabidopsis thaliana by the combination of Trichoderma harzianum Tr6 and Pseudomonas sp. Ps14. Biol. Control 2013, 65, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, J.; Goossen-van de Geijn, H. Twenty-four years of Dutch Trig® application to control Dutch elm disease. BioControl 2016, 61, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).