1. Introduction

Thraustochytrids (class Labyrinthulea) are heterotrophic eukaryotic microbes that live in marine environments including brackish water [

1,

2]. Thraustochytrids can accumulate large amount of oils in their the cell bodies, and in some thraustochytrids, high amount of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are also produced [

3,

4]. Long-chain ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids including DHA play important roles in neural and retinal development and in photoreceptor function and vision [

5]. It has been established that (

i) among Eskimos who live in Greenland, the occurrence of thrombosis is significantly even though their diet includes high-fat foods, and (

ii) ω-3 PUFAs in foods contribute to the prevention of thrombosis [

6]. Beyond the prevention of thrombosis, additional functions of DHA have been reported to include contributions to the prevention of cancer and Alzheimer's dementia, and a role in the development of the infant brain [

7,

8,

9,

10]. DHA has thus attracted the interest of the general public, and various PUFA-containing products are now available over-the-counter. On the other hand, alternatives to fish oil have been desired due to the depletion of natural resources and the risk of contaminants [

11,

12]. In an approach to overcome these issues, a thraustochytrid that produces high amounts of DHA, i.e.,

Aurantiochytrium, has been investigated.

However, obtaining oil and DHA from

Aurantiochytrium is more expensive than obtaining from natural resources, due especially to the cost of the medium components that are necessary for culturing

Aurantiochytrium. Glucose and yeast extract have been widely used as the respective carbon and nitrogen sources for culturing thraustochytrids, and the cost of DHA production is derived mainly from the medium compositions. It is therefore essential to identify a low-cost medium for the production of DHA by

Aurantiochytrium [

13]. Molasses is a thick and sweet syrup obtained from the manufacture of sugar cane and beets [

14]. Molasses contains sugars (sucrose and reducing sugars), nitrogen, phosphorus, minerals and vitamins. The main minerals in molasses are sodium, calcium and magnesium. Thraustochytrids require carbon and nitrogen sources and also salts; artificial seawater has thus been added to the medium for the efficient growth of thraustochytrids [

15]. Molasses can be considered a good alternative candidate as a medium component because it contains essential nutrients and salt, and because it is inexpensive.

We conducted the present study to investigate the use of molasses as an alternative medium for thraustochytrids. DHA-producing thraustochytrids were isolated, and the growth, lipids content and fatty acid composition were evaluated. When microbes are transferred to a different medium and conditions, the growth is sometimes inhibited because microbes can utilize nutrients in the medium by using enzymes for growth. Microbes need to adopt to environmental changes for growth, and it is possible that the release of extracellular enzymes changes. The test strains used in this study were therefore repeatedly acclimatized in molasses medium, and the production of extracellular enzymes was also compared between the strains that were acclimatized to molasses medium and the strains that were not acclimatized.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test strains

Aurantiochytrium sp. strain mem0039 (accession no. LC339681) isolated previously from seawater on the coast in Oita, Japan was used in this study. Additionally, thraustochytrids were newly isolated for this study from Tsubokawa river in Okinawa prefecture, Japan by pine pollen biting method [

16]. Thraustochytrids which attached to pine pollen were inoculated on TPTW agar plate medium [

17], and 13 strains (mem2378-2390) were isolated.

2.2. DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction and sequencing of 18S rDNA

Isolated thraustochytrids were cultured in 100 mL of a GY liquid medium consisting of glucose 3.0 g, yeast extract 1.0 g, vitamin mixture (vitamin B

1 200 mg, vitamin B

2 1 mg, vitamin B

12 1 mg per 100 mL of artificial seawater (ASW) [pH 7.0] at 28 °C for 96 hr with shaking (110 rpm). The cultured cells were collected by centrifugation (5,000 g, 5 min), and genome DNA was extracted by the phenol chloroform method [

18]. The 18S rDNA gene in the extracted DNA was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method according to the method of Honda et al. (1999) [

19]. The PCR products were purified by the polyethylene glycerol-precipitation method [

20]. The molecular size and concentration of the purified PCR products were confirmed by 1.5% agarose-gel electrophoresis. Sequencing were carried out with 3730xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2.3. Construction of the phylogenetic tree

The data of nucleotide sequences of the isolates were deposited in the database of the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The nucleotide sequences were aligned using CLUSTALX2 [

21]. The corresponding sequences in other thraustochytrids were obtained from the NCBI’s GenBank, and the phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method with MEGA ver. 6.0 software [

22].

2.4. Acclimatization of thraustochytrids to molasses-based medium

Commercial beets molasses (Shouyuu Kogyo Co. Ltd., Okayama, Japan) was purchased for this study. Molasses was diluted at fourfold with distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to 4.0 by addition of the NaOH solution. The diluted molasses was autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min and used as a basal molasses medium (M medium) for the acclimatization of isolates. The 9 strains that were able to grow on the M agar medium, i.e., strains mem0039, mem2378, mem2181, mem2182, mem2183, mem2386, mem2387, mem2388 and mem2389 were transferred to the M agar medium, and this process was continued 10 times (acclimatized strains).

2.5. Profiles of the extracellular enzymes and biomass in acclimatized and non-acclimatized strains

The extracellular enzymes were screened by an API® ZYM system (BioMérieux, Lyon, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. M medium-acclimatized and non-acclimatized strains were cultured in GY liquid medium and M liquid medium at 28°C for 96 hr with shaking (110 rpm). The aliquots of cultured cells were washed twice with sterile ASW and suspended in sterile ASW. The optical density of the cell suspensions at 600 nm was adjusted to 1.0 and used for the API ZYM assay.

2.6. Conditions for the hydrolysis of the molasses and the culture trial with hydrolyzed-molasses

The pH of the molasses was adjusted to 1.0 or 3.0, and the molasses was autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. After autoclaving, the pH was adjusted to 6.8 by the addition of 30% (w/v) NaOH solution, and the product was used as hydrolyzed-molasses (HM). Its chemical components were analyzed as described below in section 2.7. The sugar composition was identified by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) according to the method by Stefanis and Ponte Jr. [

23]. The salinity was measured with a AS710 Cond/TDS/Sal/RES meter (AS ONE, Osaka, Japan).

2.7. Growth trial

Acclimatized and non-acclimatized strains were cultured in GY33 medium, M medium and HM medium at 28°C for 96 hr with shaking (110 rpm). The contents of total sugar and nitrogen in the M medium and HM medium were adjusted to those of the GY33 medium. Aliquots of the cultures were centrifuged at 5,000 g for 5 min to collect cells, and the collected cells were washed twice with 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution. The washed cells were dried at 105°C overnight, and the biomass was calculated as a dry cell weight (DCW). The remaining cultures were washed the same way and stored at -20°C until the lipid extraction.

2.8. Chemical analysis

The chemical components were analyzed using following methods. Total sugar content was analyzed by the phenol-sulfonic method. Ammonia-nitrogen, nitrite-nitrogen, nitrate-nitrogen, total nitrogen, phosphate-phosphorus and total phosphorus were analyzed according to the method of Strickland and Parsons [

24]. The mineral composition of the molasses was analyzed by the inductively coupled plasma method with an inductivity-coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) (ICPS-8100, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The operating conditions of the ICP-OES were as follows: 1.2 L/ min plasma gas flow rate, 14.0 L /min auxiliary gas flow rate, 0.7 L/ min nebulizer gas flow rate, 0.7 L/ min carrier gas flow rate, and 1.2 kW radio frequency power.

Total lipids in the cultured cells were extracted by the Folch method [

25]. The total lipid extracted was esterified by reactions at 80°C for 3 hr with a HCl–methanol solution (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Tokyo, Japan) in a dry thermo unit (DTU-2C, TAITEC, Tokyo). The analysis of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) was performed with a gas chromatograph (GC-2014, Shimadzu). An injection port and a flame-ionization detector were held at 250 °C. The column temperature was initially held at 150°C and programmed to 220°C at 2 °C per min. Helium was used as the carrier gas. The FAMEs sample included 19:0 (nonadecanoic acid, Fluka Chemika, Buchs, Switzerland) as an internal standard and the content of each fatty acid was calculated from each peak area of the chromatogram relative to the peak of the internal standard. The peak assignment was based on a comparison of the retention times of standard fatty acids.

3. Results

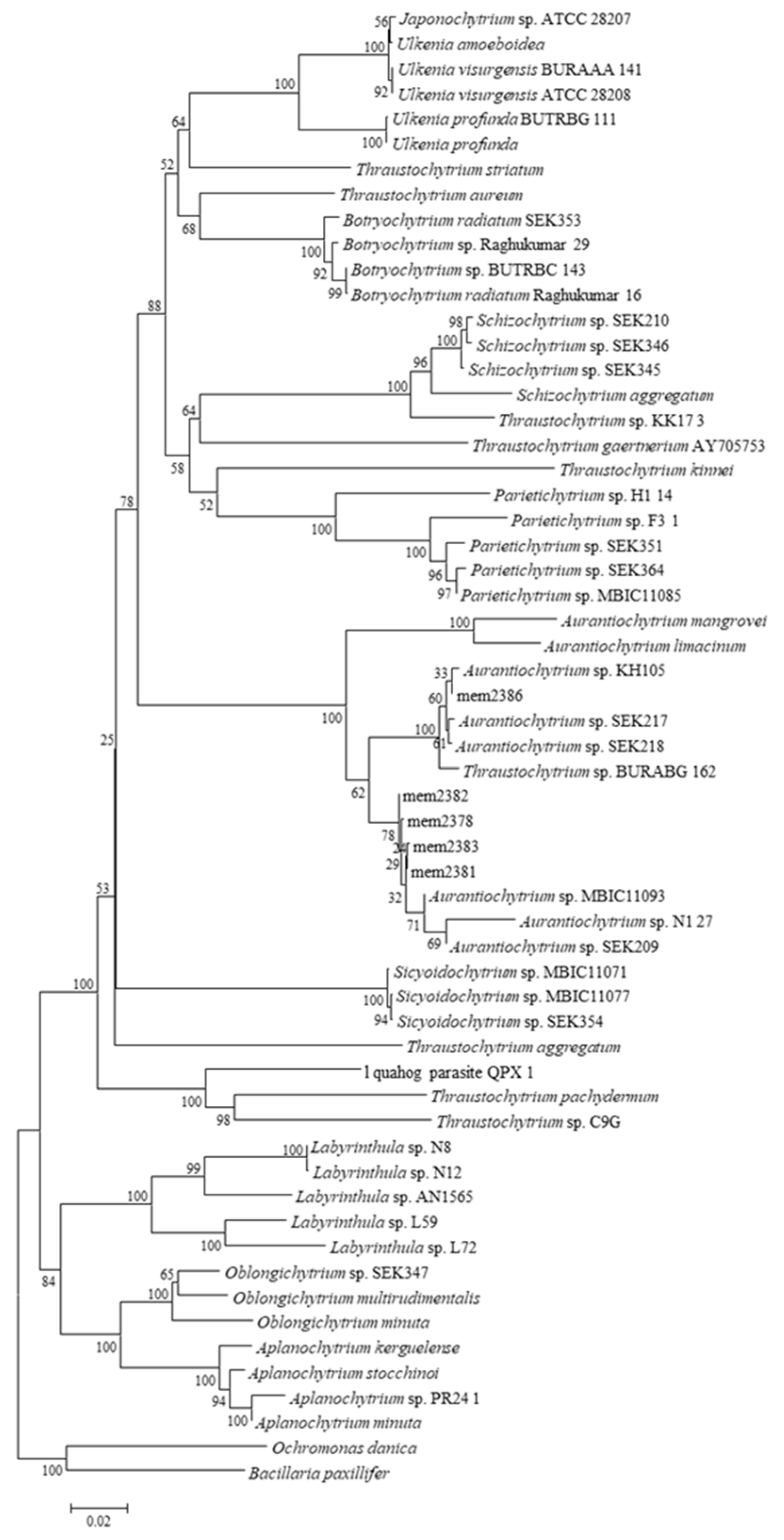

3.1. The phylogenetic tree and the identification of isolates

Partial sequences of 18S rRNA gene was obtained from five

Aurantiochytrium sp. strains; mem2378, mem2381, mem2382, mem2383, and mem2386. In the cases of three other strains (mem2387, mem2388 and mem2389), the amplification of 18S rRNA gene was not observed. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using partial sequence data (≒600 bp), and the data of six strains were located in the cluster of genus

Aurantiochytrium (

Figure 1).

3.2. Chemical composition of molasses

The results of the chemical composition analysis are summarized in

Table 1. Compared with the values of the 1% yeast extract solution which was used as the nitrogen source in the standard GY31 medium, the organic-nitrogen and total nitrogen in the molasses was tenfold, significantly higher. The total phosphorus in the molasses was significantly higher than that in the 1% yeast extract solution. Inorganic nitrogen, ammonia-nitrogen, nitrite-nitrogen and nitrate-nitrogen were detected in only the molasses. The total sugar content was 103.32 ± 2.56. For the culture experiment, the compositions of the molasses medium and the control medium were adjusted to contain the same levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and sugars based on these analytical data.

Table 2 shows the mineral composition of the molasses, which contained mailny potassium (3493 mg/L), sodium (2341 mg/L), calcium (647 mg/L) and magnesium (511 mg /L).

The chemical composition of the hydrolyzed molasses (HM) is presented in

Table 3. The contents of total sugar, total nitrogen and total phosphorus were each significantly less compared to those of the molasses without hydrolysis.

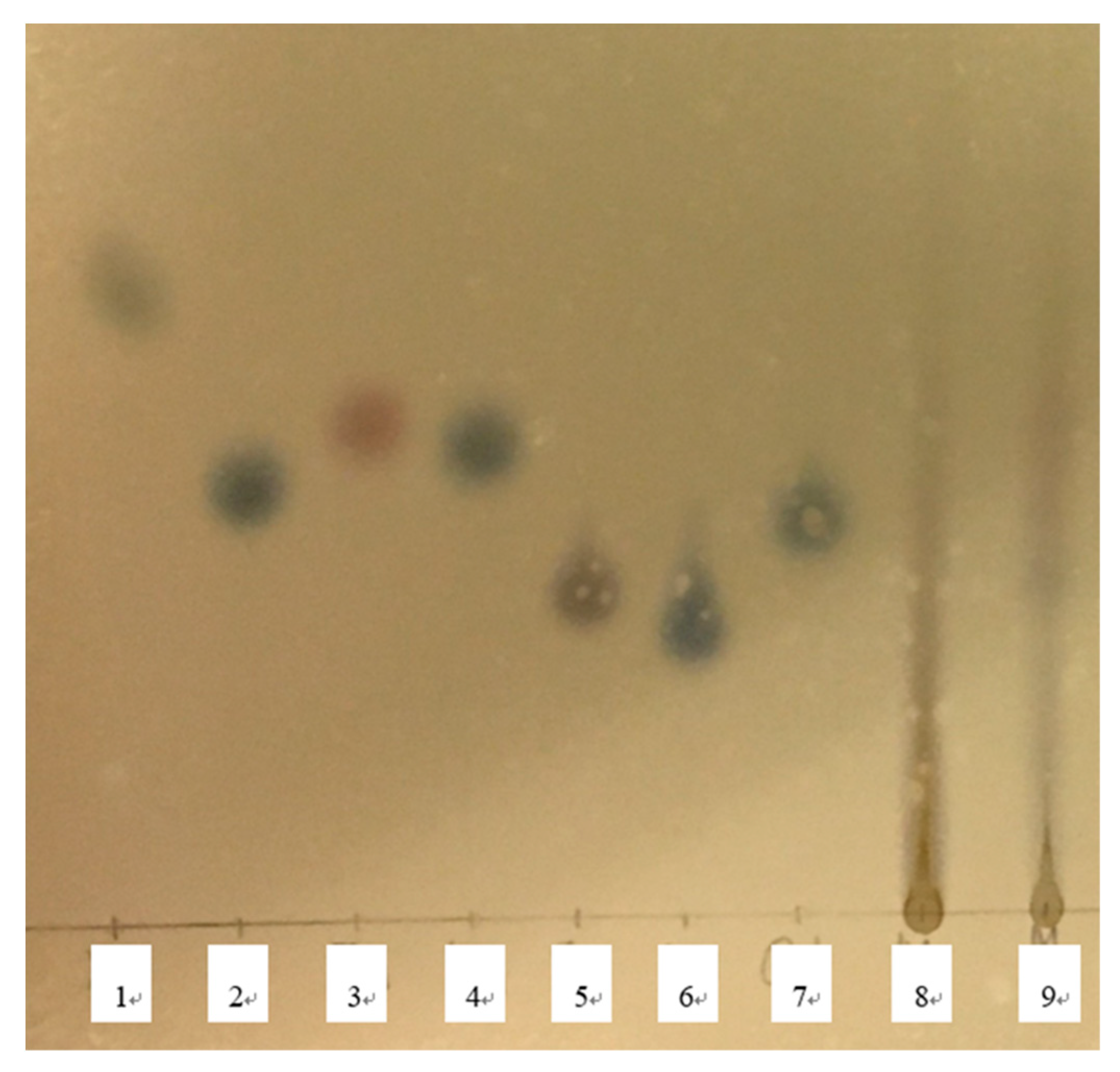

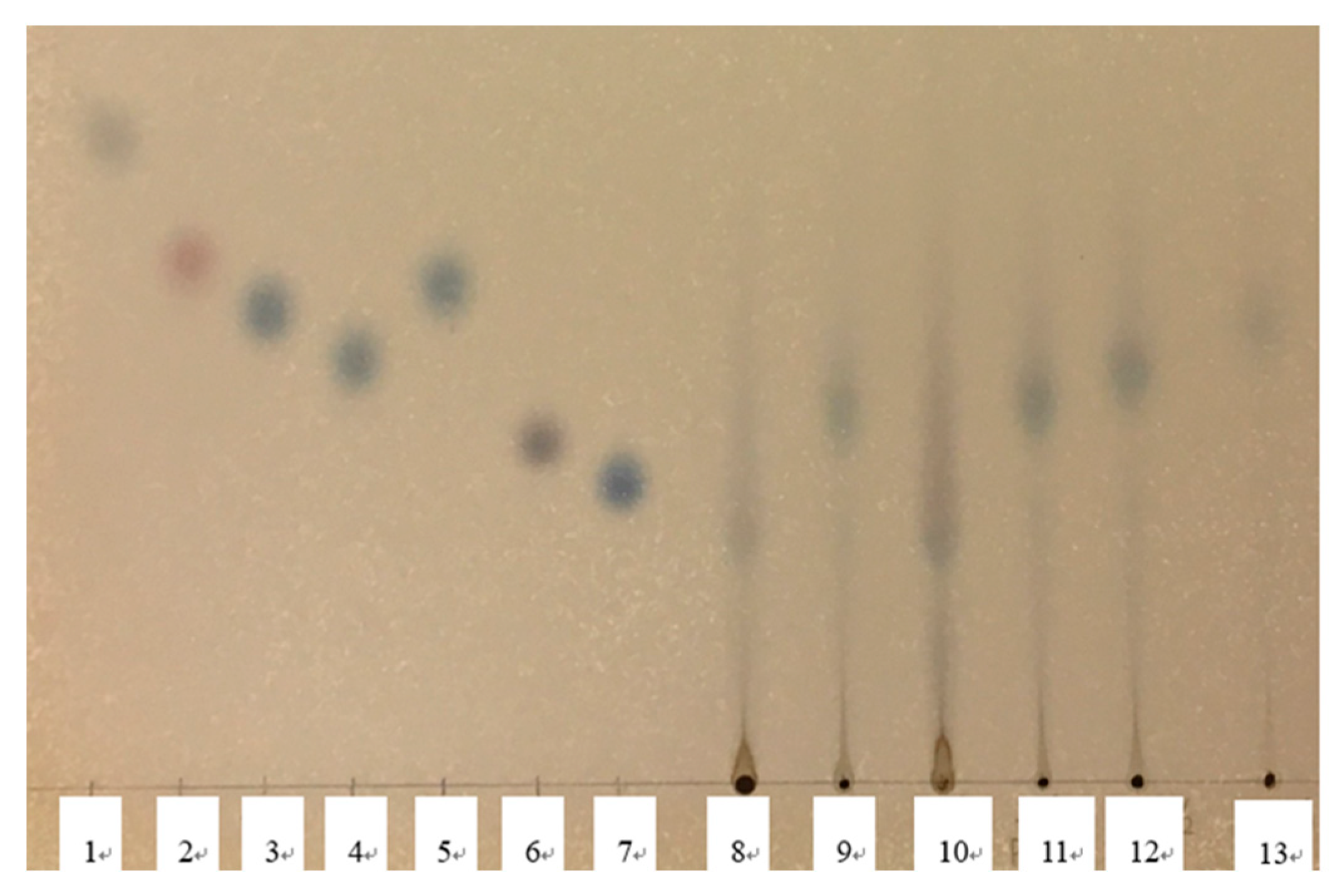

3.3. Sugar composition

The TLC results are depicted

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. In the molasses before hydrolysis, single spot was detected around an original point, and long tailing was also detected. The single spots were not detected in a comparison with the retention factor (RF) value of standard sugars (

Figure 1). In the HM, the RF value increased before hydrolysis, and the pH-lowering and the increased dilution rate induced the increase in the RF. By comparison to RF of standard sugar solutions, the RF in the single spots of hydrolyzed molasses at pH 1.08 and in the twofold diluted and sixfold diluted HM were similar to those of the glucose and mannose solution.

3.4. Culture trial of acclimatized and non-acclimatized strains in the M and HM medium

Table 4 provides the results of the biomass and total lipid content in the culture trial. The growth and total lipid content of the non-acclimatized strains mem2383 and mem2386 in HM medium were greatly decreased compared to those in the GY33 medium. The growth and total lipid content of the acclimatized strains mem2383 and mem2386 in the HM medium were higher and lower, respectively than those in the M medium. The growth and the total lipid content of strain mem2383 was increased by acclimatization treatment in the HM medium. The growth of total lipid content of strain mem2386 were increased and decreased, respectively by acclimatization treatment in the HM medium. The growth of the acclimatized strain mem2387 in the HM medium was reduced compared to that in the M medium. In case of strain mem0039, the growth in the M medium was lower than that in the GY33 medium, and the acclimatization treatment did not enhance the growth.

Table 5 shows the total sugar content in the culture medium. In case of the GY33 medium, the sugar content significantly decreased for 96 h. The total sugar content in the HM medium with acclimatized strains 2386 and 2387 decreased as compared to those in the medium M. In case of strain 0039, the sugar content did not change much in the M and HM medium in spite of acclimatization treatment and hydrolysis.

Table 6 shows the fatty acid composition of cells cultured in the GY33, M and HM media. In all strains cultured in the GY33 medium, C15:0 and C16:0 were detected as major unsaturated fatty acids, and C22:5 n-6 and C22:6n-3 (i.e., docosahexaenoic acid, DHA) were detected as major unsaturated fatty acids. In the cases of strains mem2383 and mem2387, the amount of DHA in the cells of acclimatized strains was significantly higher than that in the non-acclimatized strains. In the HM medium, significantly increased C18:2 was observed despite its non-detection in the GY33 medium. In the case of strain mem2386, the DNA ratio was 25%-35% in all conditions. For strain mem0039, the DHA ratios of the non-acclimatized and acclimatized strains cultured in the HM medium were significantly lower than those in the GY33 medium and M medium.

Table 7 presents the results of the API ZYM-assay of the production of extracellular enzymes. In the cases of all of non-acclimatized strains cultured in GY31 medium, mainly the enzymatic activities of leucine aryl-amidase, valine aryl-amidase, acid phosphatase and naphthol AS-BI phosphohydrolase were detected. All of these enzyme activities decreased or disappeared by culturing in M medium without acclimatization treatment, with the exception of strain mem2386. However, in the cases of the acclimatized strains, these enzyme activities recovered. Regarding β-glucosidase also, the same trend was shown in strains mem2383 and mem2387. Interestingly, although lipase was not detected in strain mem -2387 or -2389 cultured in the GY31 medium, the activities were detected in the acclimatized strains cultured in the M medium.

4. Discussion

The composition of molasses generally consists of sucrose and monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose, and the total sugar content is approx. 60% [

26]. In the present study, the concentration of total sugar was approx. 10% and thus lower than this previous report. Our TLC results did not indicate the existence of sucrose and fructose (

Figure 2). Mordenti et al. stated that monosaccharides (fructose and glucose) are inverted sugars than cannot be fermented because these sugars combine with nitrogen in amino acids through the Maillard reaction [

26]. The amount of reducing sugars in beet molasses has been estimated to approximately, from 0.5% to 1.5% [

27].

In another study’s TLC analysis, it was reported that a high concentration of inorganic salts in samples cause tailing [

28]. In our present investigation, tailing occurred in the hydrolyzed molasses without dilution. To avoid the interference by salts, the samples were diluted sixfold. The RF values were greater than those of the non-diluted samples, and the RF values of blue spots were similar to those of glucose (

Figure 3).

The growth of strain mem2383 in the HM medium was significantly improved by the acclimatization treatment (

Table 4). Microbes produce various extracellular enzymes to degrade materials and absorb nutrients. In all of the present non-acclimatized strains, leucine aryl-amidase and valine aryl-amidase activities disappeared, and the activities were recovered by the acclimatization process (

Table 7). Amidases are enzymes that break the amide bonds in compounds to amine and carboxylic acid. Leucine aryl-amidase (also known as leucine aminopeptidase) and valine aryl-amidase (known as valine peptidase) catalyze the hydrolysis of peptides or proteins at the N-terminal end of leucine residues and valine residues, respectively. Aminopeptidases play a critical role in the metabolism of microbial cells and cleave N-terminal amino acid residues from peptides, and they are involved in the process of protein degradation [29, 30]. The result of the API ZYM assay showed that strain mem2386 strongly produced leucine aryl-amidase and valine aryl-amidase in both the GY medium and the M medium regardless of the presence or absence of the acclimatization process. The growth of the strains other than strain mem2386 in the M medium was greatly reduced compared to that in the GY33 medium. On the other hand, in the case of strain mem2386, the obtained biomass in the HM medium was maintained at 64% compared to that in the GY33 medium. A stable production of enzymes related to protein digestion (e.g., amino peptidase) might support the growth in strain mem2386.

In all of

Aurantiochytirum strains examined in this study, acid phosphatase and naphthol AS-BI phosphohydrolase were detected, and both of these enzymes are related to the metabolism of phosphorus. Phosphatases, which are ubiquitous enzymes in nature, catalyze a hydrolytic reaction involving the C-O-P linkage of phosphate ester [

31,

32]. Phytate has been known as major phosphorus source in plant seeds and is also contained in molasses [

33]. Phytases, which hydrolyze phytates to

myo-inositol and phosphoric acid, are a subgroup of phosphatases [

34]. Microbes improve the bioavailability of organic phosphoric compounds with these enzymes. Phosphatases are also distributed in various thraustochytrid genera and species [

35,

36]. Our present results demonstrated that the productions of these enzymes are prohibited under the M medium, and recovered by acclimatization treatment (

Table 7).

The necessity of amino acids in thraustochytrids is unclear. The chemical analysis of molasses showed that its nitrogen was mainly organic nitrogen (

Table 1). Mee et al. (1979) reported that cane molasses contains aspartic and glutamic acids and alanine in protein as major amino acids [

37]. Mordenti et al (2021) reported that in beet molasses, the content of crude protein was 98 g/kg on a dry basis [

26] and was calculated as 77 g/kg on a wet basis. The concentration of the crude protein of the molasses used in our study was significantly lower than that in the report by Mordenti et al.

Aurantiochytirum can synthesize DHA via a polyketide pathway, not a standard (desaturase/ elongase) pathway [

38,

39]. Palmitic acid and DHA are thus detected in

Aurantiochytrium as a major saturated fatty acid and an unsaturated fatty acid, respectively, and intermediates in the desaturase/elongase pathway such as stearic acid (18:0), oleic acid (18:1), linoleic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid are scarce. We detected stearic acid, oleic acid and linoleic acid in

Aurantiochytrium strains cultured in the HM and M media although they were not detected or detected at lower ratios in the strains cultured in the GY33 medium. It has been reported that stearic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid are present in the lipids fraction of molasses as major fatty acids [

26], and it has predicted that strains cultured in molasses absorb these fatty acids and accumulate these fatty acids in cell bodies. One of our earlier studies confirmed the content of oleic acid in cultured cells of thethraustochytrid

Thraustochytrium aureum ATCC 34304 by the addition of oleate containing Tween 80 into the culture medium [

40].

Ma et al. (2023) indicated that a

Schizochytrium sp. had poor utilization of sucrose (which is rich in cane molasses), and they were successful at increasing the sucrose utilization in the

Schizochytrium sp. by overexpressing endogenous sucrose hydrolase [

41]. Our present findings demonstrated that the strain’s growth in molasses medium was improved by the hydrolysis of molasses and by the acclimatization treatment. However, the yields of biomass and lipid were lower than those in the standard medium. To resolve these issues, further studies applying genetic manipulation and a survey of inhibitory factors are necessary.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study revealed that the growth of a newly isolated Aurantiochytrium was significantly inhibited in molasses medium and was recovered by acclimatization treatment in molasses medium. The profiles of extracellular enzymes was also affected by this treatment. The fatty acid composition in the cultured cells was affected by the molasses medium compared to the basal GY medium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T., T.G. and Y.I.; methodology, Y.T. and N.T.; validation, Y.T. and N.T.; Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, Y.T., N.T., T.M. and K.S.; investigation, Y.T.; resources, Y.T., G.T. and Y.I.; data curation, Y.T. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.T.; visualization, Y.T. and N.T.; supervision, Y.T.; project administration, T.G. and Y.I.; funding acquisition, T.G and Y.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Industry-academia-government collaboration R&D support project, grant number 265”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raghukumar, S. Ecology of the marine protists, the Labyrinthulomycetes (Thraustochytrids and Labyrinthulids). Europ. J. Protistol. 2002, 38, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorni, L.; Dini, F. Distribution and abundance of thraustochytrids in different Mediterranean coastal habitats. Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 2002, 30, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghukumar, S. Thraustochytrids marine protist: production of PUFAs and other engineering tehchnologies. Mar. Biotechnol. 2008, 10, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Ren, L.J.; Sun, G.N.; Ji, X.J.; Nie, Z.K.; Huang, H. Batch, fed-batch and repeated fed-batch fermentation processes of the marine thraustochytrid Schizochytrium sp. for producing docosahexaenoic acid. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 36, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, A.; Flores, L.; Shene, C.; Chisti, Y.; Larama, G.; Asenjo, J.A.; Armenta. Antarctic thraustochytrids as sources of carotenoids and high-value fatty acids. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, K.; Toshima, Y.; Asak, F.; Nakashima, M. Effect of dietary docosahexaenoic acid in the rat middle cerebral artery thrombosis model. Thromb. Res. 1995, 78, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.; Rauter, A.P.; Bandarra, N. Marine Sources of DHA-Rich Phospholipids withAnti-Alzheimer Effect. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, L. , Brambilla, P. ; Mazzocchi, A.; Harsløf, L.B.S.; Ciappolino, V.; Agostoni, C. DHA Effects in Brain Development and Function. Nutrients 2016, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Pejaver, R.K.; Sukhija, M.; Ahuja, A. Role of DHA, ARA, & phospholipids in brain development: An Indian perspective. Clin. Epidemiology Glob. Health 2017, 5, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Rodrigues, J.; Philippsen, H.K.; Dolabela, M.F.; Nagamachi, C.Y.; Pieczarka, J.C. The potential of DHA as cancer therapy strategies: a narrative review of in vitro cytotoxicity trials. Nutrietns 2023, 15, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan-Geels, G.; Bishop, K.S.; Ferguson, L.R. Alternative Sources of Omega-3 Fats: Can We Find a Sustainable Substitute for Fish? Nutrients 2013, 5, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tur, J.A.; Bibiloni, M.M. , Sureda, A.; Pons, A. Dietary sources of omega 3 fatty acids: public health risks and benefits. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, S23–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; El-Samawaty, A.E.M.A.; Elgorban, A.M.; Bahkali, A.H. Utilization of low-cost substrates for the production of high biomass, lipid and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) using local native strain Aurantiochytrium sp. YB-05. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Nunzio, M.D.; Danesi, F.; Caboni, M.F.; Bordoni, A. Sugar cane and sugar beet molasses, antioxidant-rich alternatives to refined sugar. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2012, 60, 12508–12515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabala, L.; McMeekin, T.; Shabala, S. Thraustochytrids can be grown in low-salt media without affecting PUFA production. Mar. Botechnol. 2013, 2013 15, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Wilkens, S.; Adcock, J.L.; Puri, M.; Barrow, C.J. Pollen baiting facilitates the isolation of marine thraustochytrids with potential in omega-3 and biodiesel production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 40, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoka, Y.; Nagano, N.; Okita, Y.; Izumida, H.; Sugimoto, S.; Hayashi, M. Effect of addition of Tween 80 and potassium dihydrogenphosphate to basal medium on the isolation of marine eukaryotes, thraustochytrids. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2008, 105, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, C.P.; Hargreaves, R.H.M. An improved protocol for the isolation of total genomic DNA from Labyrinthulomycetes. Biotehnocol. Lett. 2015, 37, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, D.; Yokochi, T.; Nakahara, T.; Raghukumar, S.; Nakagiri, A.; Schaumann, K.; Higashihara, T. Molecular phylogeny of labyrinthulids and thraustochytrids based on the sequencing of 18S ribosomal RNA gene. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1999, 46, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Riesner, D. Purification of nucleic acids by selective precipitation with polyethylene glycol 6000. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 354, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar,S. ; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanis, V.A.D.; Ponte Jr., J.G. Separation of sugars by thin-layer chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1968, 34, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, J.D.H.; Parsons, T.R. A. Practical Hand Book of Seawater Analysis. Fish. Res. Board Canada 1972, 167, 1–311. [Google Scholar]

- Folch, J.; Ascoli, I.; Lees, M.; Meath, J.A.; Lebaron, N. Preparation of lipid extracts from brain tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 195, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordenti, A.L.; Giaretta, E.; Campidonico, L.; Parazza, P.; Formigoni, A. ; A Review Regarding the Use of Molasses in Animal Nutrition. Animals 2021, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B. Working with sugars (and molasses). In Proceedings of the 13th Annual Florida Ruminant Nutrition Symposium, Gainesville, FL, USA, 11–12 January 2002; pp. 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, M. Separation of some carbohydrates in urine. Jpn. J. Clin. Chem. 1973, 2, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, R.; Tomar, D.; Pandya, C.D.; Singh, R. The leucine aminopeptidase of Staphylococcus aureus is secreted and contributes to biofilm formation. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, e357–e381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, S.M.; Tay, S.T.; Puthucheary, S.D. Enzymatic and molecular characterization of leucine aminopeptidase of Burkholderia pseudomallei. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.A.; Magboul, P.; McSweeney, L.H. Purification and characterization of an acid phosphatase from Lactobacillus plantarum DPC2739. Food Chem. 1999; 65, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.A.; Magboul, P.; McSweeney, L.H. Purification and properties of an acid phosphatase from Lactobacillus curvatus DPC2024. Int. Dairy J. 1999; 9, 849–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, H.; Ouvry, A.; Bervas, E.; Guy, C.; Messager, A.; Demigne, C.; Remesy, C. Strains of lactic acid bacteria isolated from sourdoughs degrade phytic acid and improve calcium and magnesium solubility from whole wheat flour. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2281–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, A.; Satyanarayana, T. Phytases: microbial sources, production, purification, and potential biotechnological applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2003, 23, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taoka, Y.; Nagano, N.; Okita, Y.; Izumida, H.; Sugmito, S.; Hayashi, M. Extracellular enzymes produced by marine eukaryotes, thraustochytrids. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Li, W.H.; Chen, C.C.; Cheng, T.H. , Lan, Y.H.; Huang, M.D.; Chen, W.M.; Chang, J.S.; Chang, H.Y. Diverse Enzymes With Industrial Applications in Four Thraustochytrid Genera. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 573907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mee, J.M.L; Brooks, C.C.; Stanley, R.W. Amino acid and fatty acid composition of cane molasses. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1979, 30, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Sakaguchi, K.; Matsuda, T.; Abe, E.; Hama, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Honda, D.; Okita, Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Okino, N.; Ito, M. I ncrease of eicosapentaenoic acid in thraustochytrids through thraustochytrid ubiquitin promoter-driven expression of a fatty acid Δ5 desaturase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 2011. 77, 3870–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, N.; Sakaguchi, K.; Taoka, Y.; Okita, Y.; Honda, D.; Ito, M.; Hayashi, M. Detection of genes involved in fatty acid elongation and desaturation in thraustochytrid marine eukaryotes. J. Oleo Sci. 2011, 60, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoka, Y.; Nagano, N.; Okita, Y.; Izumida, H.; Sugmito, S.; Hayashi, M. Effect of Tween 80 on the growth, lipid accumulation and fatty acid composition of Thraustochytrium aureum ATCC 34304. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011, 111, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, W.; Huang, P.; Gu, Y.; Sun, X.; Huang, H. Enhanced docosahexaenoic acid production from cane molasses by engineered and adaptively evolved Schizochytrium sp. Biores. Tech. 2023, 376, 128833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method based on the partial sequence of the 18S rRNA gene of thraustochytrids isolates and corresponding region in those for authentic thraustochytrids genes. Numbers at branches denote the bootstrap percentage of 1000 replicates. The scale at the bottom indicates the evolutionary distance of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method based on the partial sequence of the 18S rRNA gene of thraustochytrids isolates and corresponding region in those for authentic thraustochytrids genes. Numbers at branches denote the bootstrap percentage of 1000 replicates. The scale at the bottom indicates the evolutionary distance of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 2.

The result of thin layer chromatograph with standard sugar solutions 1) xylose, 2) glucose, 3) fructose, 4) Mannose, 5) sucrose, 6) maltose and 7) galactose, and molasses samples 8) non-diluted molasses and 9) two-times diluted molasses.

Figure 2.

The result of thin layer chromatograph with standard sugar solutions 1) xylose, 2) glucose, 3) fructose, 4) Mannose, 5) sucrose, 6) maltose and 7) galactose, and molasses samples 8) non-diluted molasses and 9) two-times diluted molasses.

Figure 3.

The result of thin layer chromatograph with standard sugar solutions 1) xylose, 2) fructose, 3) glucose, 4) galactose, 5) mannose, 6) sucrose and 7) maltose, and molasses samples at different dilution level and different pH 8 and 10) non-diluted, pH 3.08, 9 and 11) non-diluted, pH 1.08, 12) two-times diluted, pH 1.08 and 13) 6 times-diluted, pH 1.08.

Figure 3.

The result of thin layer chromatograph with standard sugar solutions 1) xylose, 2) fructose, 3) glucose, 4) galactose, 5) mannose, 6) sucrose and 7) maltose, and molasses samples at different dilution level and different pH 8 and 10) non-diluted, pH 3.08, 9 and 11) non-diluted, pH 1.08, 12) two-times diluted, pH 1.08 and 13) 6 times-diluted, pH 1.08.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of molasses and 1% yeast extract.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of molasses and 1% yeast extract.

| |

Molasses |

1% yeast extract |

| Total sugar (g/L) |

102.32±2.56 |

UN |

| Ammonia-nitrogen (g/L) |

0.78±0.03 |

ND |

| Nitrite-nitrogen (mg/L) |

0.012±0.00 |

ND |

| Nitrate-nitrogen (g/L) |

0.27±0.01 |

ND |

| Organic-nitrogen (g/L) |

9.76±0.10* |

0.89±0.04 |

| Total nitrogen (g/L) |

12.51±0.08* |

1.19±0.01 |

| Total phosphorus (mg/L) |

0.51±0.02* |

0.12±0.00 |

| Solid content (%) |

37.34±0.07 |

UN |

Table 2.

Mineral composition of molasses.

Table 2.

Mineral composition of molasses.

| Elements |

Molasses (mg/L) |

| Ca |

647.4 |

| Mg |

511.7 |

| Fe |

48.9 |

| Na |

2341.1 |

| K |

3493.9 |

| Cu |

1.5 |

| Mn |

11.9 |

| Al |

8.1 |

| Zn |

8.1 |

Table 3.

Chemical composition of molasses and hydrolyzed molasses.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of molasses and hydrolyzed molasses.

| |

Molasses (M) |

Hydrolyzed molasses (HM) |

| Total sugar (g/L) |

102.43±6.34 |

70.98±2.41 |

| Total nitrogen (g/L) |

12.37±0.34 |

8.66±0.25 |

| Total phosphorus |

0.85±0.04 |

0.66±0.08 |

| Salinity |

106 |

130 |

Table 4.

Biomass and lipid of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium.

Table 4.

Biomass and lipid of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium.

| |

|

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

A |

| Strains |

Medium |

GY33 |

HM |

HM |

M |

| 2383 |

Biomass (g/L) |

7.2 |

0.6 |

3.3 |

1.7 |

| |

Lipid (%) |

48 |

10.3 |

13.2 |

26.5 |

| 2386 |

Biomass (g/L) |

5.7 |

3 |

3.7 |

2.7 |

| |

Lipid (%) |

29.2 |

21.7 |

11.9 |

13.9 |

| 2387 |

Biomass (g/L) |

4.8 |

2 |

1.1 |

2 |

| |

Lipid (%) |

24.1 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

8.7 |

| 39 |

Biomass (g/L) |

2.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

| |

Lipid (%) |

26.3 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

3.9 |

Table 5.

Total sugar content in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium after cultivation of strains at 0 h and 96 h cultivation.

Table 5.

Total sugar content in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium after cultivation of strains at 0 h and 96 h cultivation.

| |

|

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

A |

| Strains |

Medium |

GY33 |

HM |

HM |

M |

| 2383 |

0 h |

29.5 |

25.1 |

24.5 |

26.9 |

| |

96 h |

9.7 |

27 |

24.1 |

27.5 |

| 2386 |

0 h |

32.4 |

25 |

25.8 |

26.6 |

| |

96 h |

21.8 |

21.1 |

21.7 |

26 |

| 2387 |

0 h |

32 |

25.5 |

24.9 |

26.8 |

| |

96 h |

13.7 |

25 |

20 |

26.3 |

| 39 |

0 h |

31.2 |

25.2 |

25.8 |

26.9 |

| |

96 h |

14.1 |

24.4 |

26.8 |

26.8 |

Table 6.

(1). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem2383 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium. (2). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem2386 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium. (3). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem2387 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium. (4). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem0039 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium.

Table 6.

(1). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem2383 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium. (2). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem2386 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium. (3). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem2387 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium. (4). Fatty acid composition in the strain mem0039 cells of un-acclimatized (UN-A) and acclimatized (A) strains cultured in GY 33 medium, HM medium and M medium.

| |

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

A |

| Fatty acids |

GY33 |

HM |

HM |

M |

| (1) |

| C14:0 |

2.13 |

1.56 |

1.81 |

0.6 |

| C15:0 |

29.95 |

1.09 |

9.34 |

3.01 |

| C16:0 |

10.42 |

37.93 |

23.41 |

15.65 |

| C16:1 |

ND |

3.75 |

0.95 |

0.93 |

| C17:0 |

7.04 |

0.8 |

4.3 |

3.15 |

| C18:0 |

0.64 |

8.61 |

4.24 |

1.3 |

| C18:1 |

ND |

1.67 |

1.32 |

1.91 |

| C18:2 |

ND |

39.56 |

16.69 |

5.47 |

| C20:4n-6 |

1.11 |

0.11 |

0.91 |

2.84 |

| C20:5n-3 |

1.8 |

0.33 |

2.61 |

6.18 |

| C22:5n-6 |

12.5 |

0.3 |

9.24 |

18.33 |

| C22:5n-3 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| C22:6n-3 |

33.43 |

4.3 |

23.82 |

38.72 |

| ND, not detected. |

| (2) |

| C14:0 |

0.73 |

1.78 |

1.92 |

1.19 |

| C15:0 |

22.34 |

11.43 |

12.82 |

11.97 |

| C16:0 |

5.84 |

23.04 |

22.35 |

16.83 |

| C16:1 |

ND |

0.88 |

0.76 |

1.06 |

| C17:0 |

8.23 |

5.28 |

5.41 |

6.8 |

| C18:0 |

0.83 |

3.9 |

3.55 |

2.12 |

| C18:1 |

ND |

0.62 |

0.61 |

0.59 |

| C18:2 |

ND |

13.27 |

13.6 |

12.09 |

| C20:4n-6 |

2.21 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

1.36 |

| C20:5n-3 |

5.03 |

2.25 |

2.25 |

2.68 |

| C22:5n-6 |

16.76 |

9.84 |

9.48 |

11.79 |

| C22:5n-3 |

2.64 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

1.45 |

| C22:6n-3 |

35.38 |

25.83 |

25.42 |

30.08 |

| (3) |

| C14:0 |

1.37 |

1.48 |

1.22 |

0.79 |

| C15:0 |

30.05 |

1 |

7.18 |

2.49 |

| C16:0 |

7.57 |

39.31 |

20.65 |

16.1 |

| C16:1 |

0 |

3.33 |

1.04 |

1.91 |

| C17:0 |

11.24 |

0.73 |

1.69 |

3.43 |

| C18:0 |

0.5 |

10.01 |

3.81 |

2.79 |

| C18:1 |

0 |

1.74 |

0.6 |

1.47 |

| C18:2 |

0 |

38.58 |

15.04 |

6.59 |

| C20:4n-6 |

1.28 |

0.1 |

2.1 |

3.53 |

| C20:5n-3 |

2.82 |

0.37 |

5.17 |

5.9 |

| C22:5n-6 |

13.88 |

0 |

13.54 |

19.57 |

| C22:5n-3 |

0.92 |

0 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

| C22:6n-3 |

30.37 |

3.36 |

26.65 |

34.16 |

| (4) |

| C14:0 |

0.62 |

1.46 |

1.78 |

2.33 |

| C15:0 |

7.6 |

0.99 |

1.17 |

6.33 |

| C16:0 |

22.33 |

37.99 |

39.55 |

24.43 |

| C16:1 |

0 |

3.33 |

3.79 |

2.04 |

| C17:0 |

11.44 |

0.66 |

0.76 |

2.66 |

| C18:0 |

2.13 |

7.76 |

8.32 |

4.2 |

| C18:1 |

0 |

1.95 |

1.78 |

1.37 |

| C18:2 |

0 |

41.27 |

39.33 |

12.34 |

| C20:4n-6 |

1.04 |

0.19 |

0.15 |

0.59 |

| C20:5n-3 |

3.83 |

0.71 |

0.21 |

1.34 |

| C22:5n-6 |

13.42 |

0 |

0 |

11.03 |

| C22:5n-3 |

2.39 |

0.29 |

0 |

0.56 |

| C22:6n-3 |

35.3 |

3.38 |

3.15 |

30.8 |

Table 7.

Profile of extracellular enzymes in strains mem2383, 2386, 2387 and 0039 by API-ZYME assay.

Table 7.

Profile of extracellular enzymes in strains mem2383, 2386, 2387 and 0039 by API-ZYME assay.

| |

mem2383 |

mem2386 |

mem2387 |

mem0039 |

| |

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

UN-A |

UN-A |

A |

| |

GY31 |

M |

M |

GY31 |

M |

M |

GY31 |

M |

M |

GY31 |

M |

M |

| Enzyme No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 5 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

| 6 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

| 7 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 8 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 10 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

| 11 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

| 12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 13 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 14 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 15 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 16 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

| 17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 18 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 19 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).