2. Materials and Methods

The study was consisted with 2 experiments as following. Experiment 1 was to apply three AM fungal species, Acaulospora, Entrophospora and Glomus to cabbage (B. oleracea cv. cabitata), mustard (B. juncea Coss.) and maize (Zea mays L., cv. suwan 4452 as AM host plant) in sterilized soil. The sterilized soil adding spore of AM fungi and leaving bare fallow was used as a control treatment. These 3 species of AM fungi were chosen because of their sensitivity to Brassica. Experiment 2 was to examine effects of root residues (from sub-experiment 1) incorporated into soil on viability of AM fungal spore to colonize in maize roots.

Soil sample belongs to Pak Chong soil series: clay-loam, kaolinitic, isohyperthermic, Typic Paleustults. The soil was collected at the depth of 0-15 cm (14° 38΄ N, 101° 19′ E, elevation 354 m above sea level, National corn and sorghum research centre, Thailand). The soil physical properties were clay soil with reddish brown (2.5YR 6/6). The soil chemical properties were pH 6.3 (1:1 soil:H2O), soil organic matter 23.5 g kg-1 (Walkley and Black method), available phosphorus (P) 18 mg kg-1 (Bray II) and extractable iron (Fe) 512 mg kg-1 (NH4OAc, pH 7.0). The soil was allowed to air dry, crushed with a mallet, roots removed by hand, well mixed and then sterilized twice by autoclave at 121 °C for 15 min.

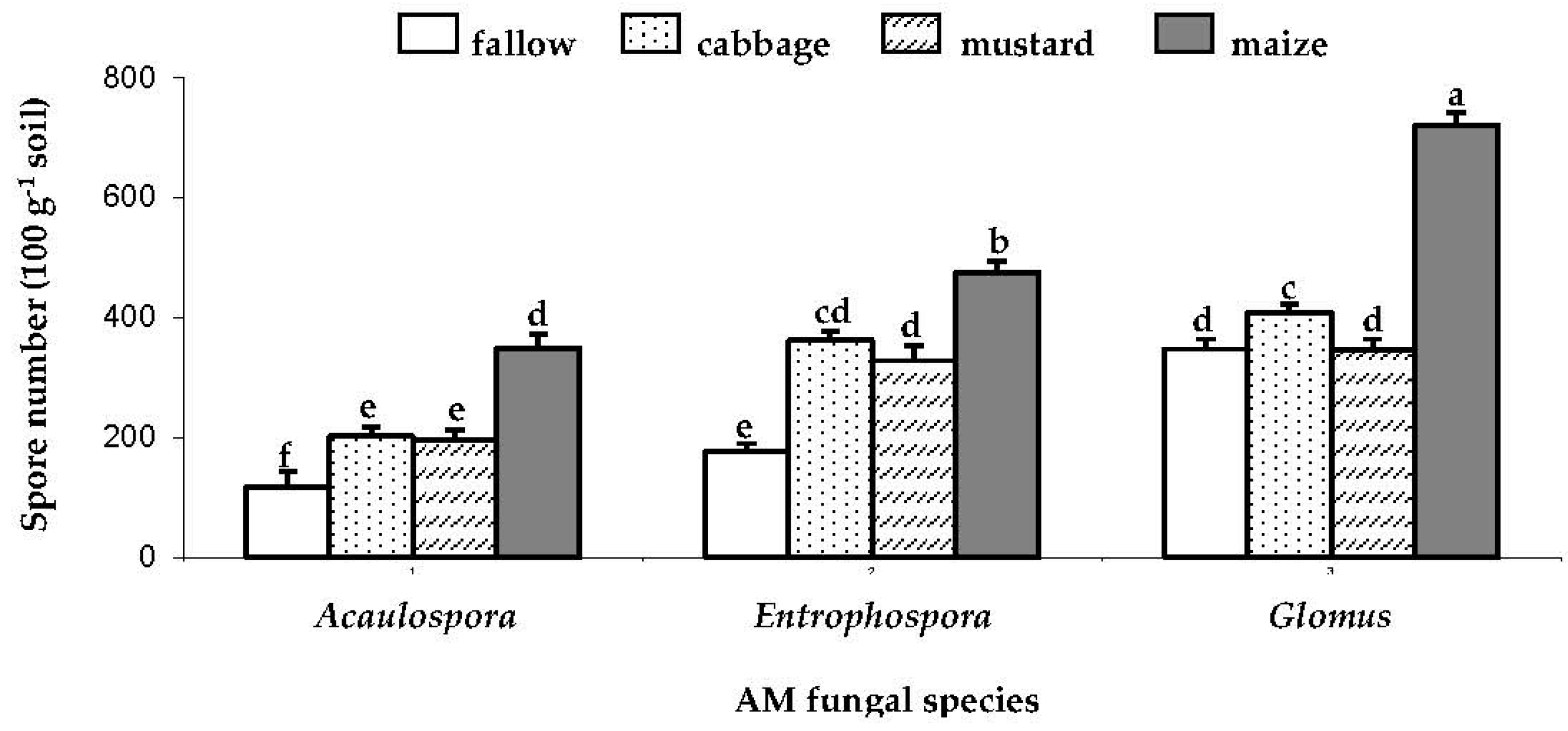

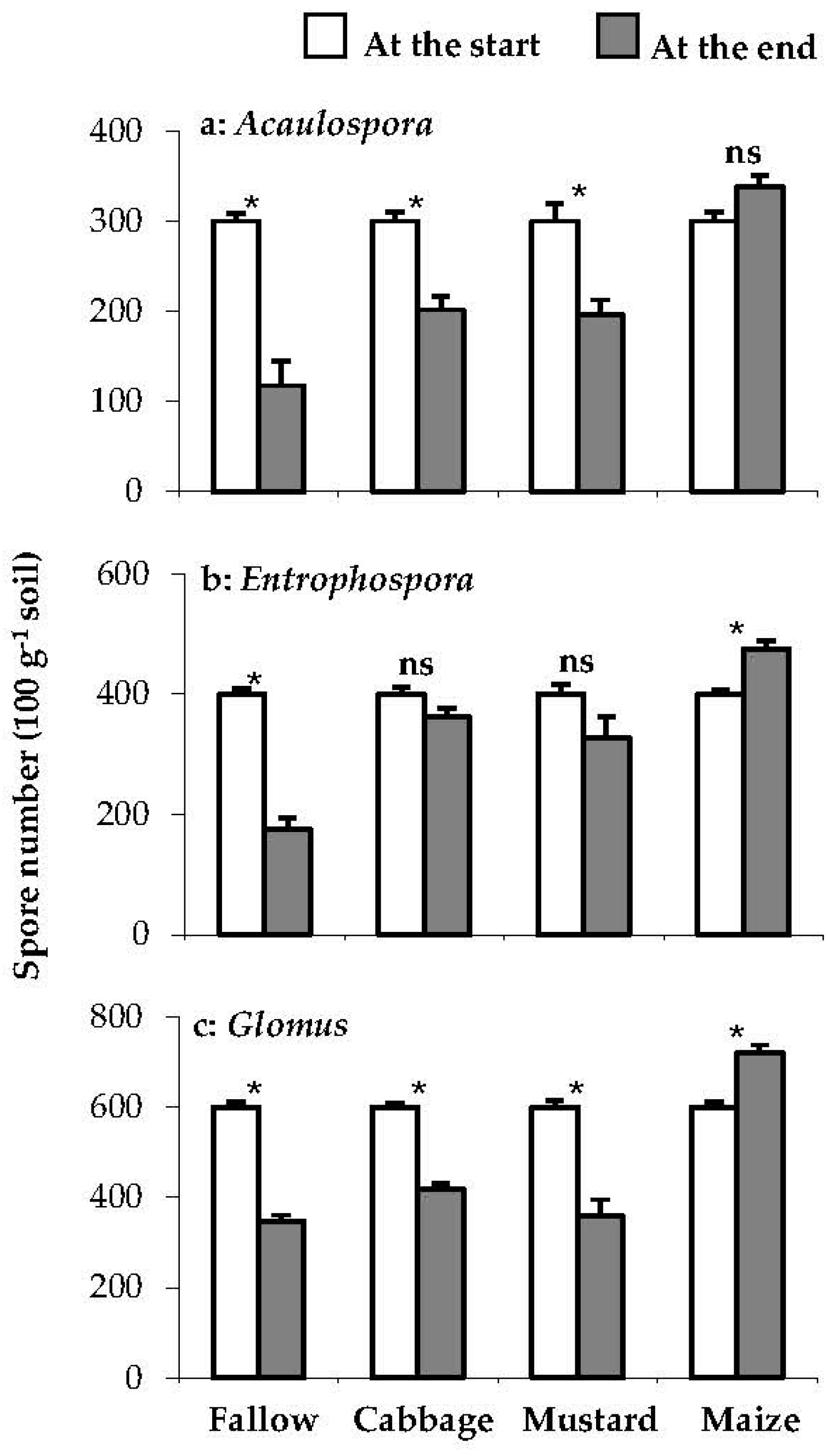

Experiment 1 Pot experiment was undertaken in completely randomized design with 3 replications consisting of factorial combinations of 3 AM fungal species (Acaulospora, Entrophospora and Glomus) and 4 crop regimes (fallow, cabbage, mustard and maize).

Sterilized plastic pots, 27 cm diameter at the top, 17 cm diameter at the bottom and 25 cm in height, were prepared as follows: a lower 13 cm deep layer of 3 kg of autoclaved soil was added and overlain with a 10 cm layer of mixture of 1 kg of soil AM inoculum (containing ca. 18000, 24000 and 36000 spores of Acaulospora, Entrophospora and Glomus, respectively) and 2 kg of autoclaved soil.

Plant seeds were sterilized by soaking in 0.5% sodium hypochloride solution for 10 min followed by rinsing several times with sterilized water. Seeds were placed onto the pot soil and then covered with ca. 2 cm layer of sterilized soil. Fertilizer was applied on the planting day. Nitrogen (N) was applied as urea at the rate of 1.9 g urea per pot (on a soil weight basis, equivalent to 210 kg N ha-1) on soil surface. P was applied as triple super phosphate (TSP, 0-46-0) by surface banding on one side of the pot at the rate of 0.70 g TSP per pot (equivalent to 32.75 kg P ha-1). Zinc (Zn) fertilizer was applied at the rate of 0.38 g of Zn per pot as Zn-EDTA (equivalent to 30.4 kg Zn ha-1). After seed emergence, 10 days after planting (D), seedlings were thinned to 3 plants per pot and grown under greenhouse conditions (35-40 °C). Pots were watered by spraying distilled water over the surface as required. Weeds and insects were removed by hand. No other chemicals were applied.

At D70, the roots were removed from the soil as much as possible and then washed carefully with tap water. Cleaned roots were placed in a sealed plastic bag and stored immediately in an ice box before moving to laboratory. The root sample was determined for fresh weight and then divided equal parts. The first root fraction was cut into 1-cm pieces by sterilized scissor and then stored in a sealed plastic bag at 4°C for using in Experiment 2. The remaining root fraction was determined for dry weight, AM colonization and ITCs content. The root fraction for ITC analysis was frozen immediately at -20 °C until required.

The soil without the roots was mixed thoroughly and subsampled ca. 200 g per pot for determining AM spore number. The rest of soil was placed in a sealed plastic bag and then stored at room temperature for two days before being used as soil sample in experiment 2.

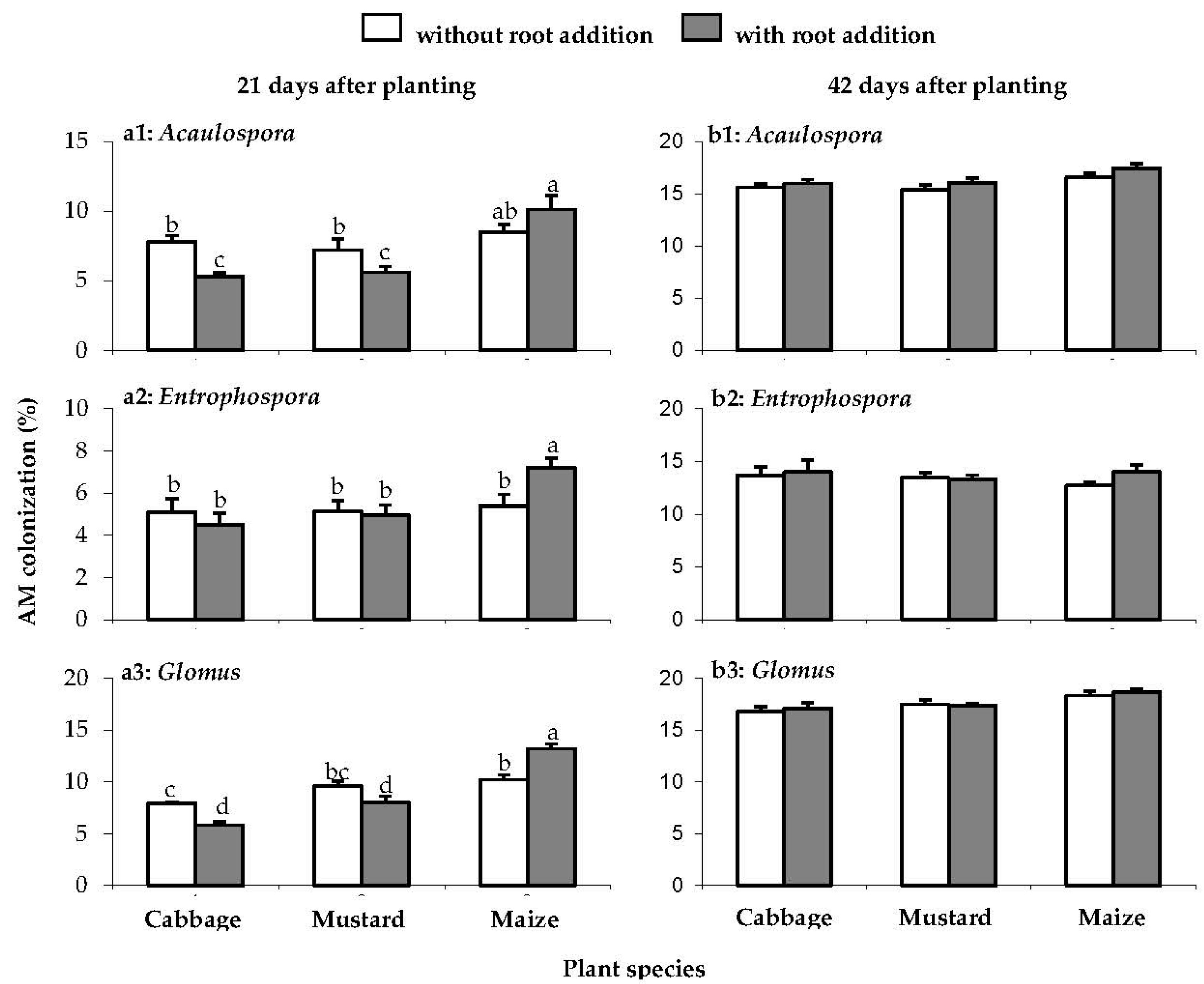

Experiment 2 The soil sample from Experiment 1 was divided into equal parts (for with/without root incorporation) and then placed in sterilized plastic pots. The root fraction from Experiment 1 which was stored in sealed plastic bag at 4 °C for 2 days, was added into soil pot in treatment with root incorporation. The root was mixed throughout the soil with a sterilized spatula. This process was also undertaken with maize soil from Experiment 1. Distilled water was added to pots to field capacity (30% w/v) and then a transparent plastic bag was placed over the pot without being sealed. The pots were maintained at room temperature for 6 weeks. Maximum and minimum temperatures of incubation room were 32±3 and 25±3 °C, respectively (during late wet season, from September to October, 2022).

After soil-root incubation period, three maize seeds were planted in each pot. After seeds emergence (D10), maize was thinned to one plant per pot. Maize was grown in greenhouse conditions (35-40 °C) during the early dry season, from November to December, 2022. Fertilizer was applied on the planting day. N was applied as urea at the rate of 0.9 g urea per pot (equivalent to 210 kg N ha-1) on soil surface. P was applied as triple super phosphate (TSP, 0-46-0) by surface banding on one side of the pot at the rate of 0.35 g TSP per pot (equivalent to 32.75 kg P ha-1). Zinc (Zn) fertilizer was applied at the rate of 0.19 g of Zn per pot as Zn-EDTA (equivalent to 30.4 kg Zn ha-1). Pots were watered by spraying distilled water over the surface as required. Weeds and insects were removed by hand. No other chemicals were applied. At D21 and D42, each of 3 replications was harvested for determining AM colonization.

In Experiment 1, root sample was determined for dry weight, AM colonization and ITC contents and soil sample was determined for spore number. In Experiment 2, determination of AM colonization in maize root was undertaken.

The soil samples were left to air-dry for determining the total AM spore number by the wet sieving and decanting method [

11] followed by sucrose centrifugation [

12].

AM colonization was done by cleared in 10% KOH solution (w/v), stained with trypan blue (C. I. 23850, Ajex Finechem) [

13], determined by making slides and viewing the roots with a compound microscope [

14] and then the percentage of AM colonization was calculated by the method of Trouvelet [

15].

The Brassica root fraction was determined the types of ITCs. Briefly, 5 g of fresh weight were de-frosted, finely chopped and then placed in 50 ml centrifuge tube. The 0.1 M CaCl2 and ether, each of 5 ml, were added into the centrifuge tube. The tube was shaken at 100 rpm for 30 min and then centrifuged at 239 g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and placed at 4 °C prior to analysis. The extraction process was conducted twice producing ca. 10 ml ether extractant. The samples were identified for the types of ITCs by GC/MS. The analysis was undertaken by using a Thermo Scientific (ITO 900) equipped with a mass spectrophotometer detector. The column was a 30m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 μm (TR-5ms Thermo®). The temperature program was set at initial 35 °C for 3 min, at ramp 1 (12 °C min-1) 96 °C and ramp 2 (18°C min-1) 240 °C for 6 min. The post run condition was set at 300 °C with 5 min hold time. The sample was injected splitless by AI/AS 3000 autosampler at an oven temperature of 50 °C. The carrier gas used was helium at flow rate 1 ml min-1 and velocity 30 cm s-1. 2-phenylethyl ITC was used as standard.

Percentage of AM root colonization was transformed by arc-sine for analyzing with ANOVA. All data were checked for normal distribution. Subsequently, data were subjected to analysis of variance with the SPSS. ANOVA was used to determine the main effects of AM fungal species and crop regimes and their two-way interactions. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test at P < 0.05 % was used for post hoc testing.T tests were used to compare means of two data sets.

4. Discussion

Brassica reduced AM density of three fungi;

Acaulospora,

Entrophospora and

Glomus. However, it remains unknown how some AM spores disappeared without a host crop. Surprisingly, almost nothing has been published on this topic and there remains a need for detailed studies on spore longevity in field soils. However, one possible explanation is that ITCs could affect immature AM spores causing them to break down before the spore walls have matured. Anthony et al. [

9] demonstrated that AM fungi failed to penetrate to roots of non-host Brassicales. The laboratory studies of Schreiner and Koide [

16,

17] showed that living roots of

B. nigra and

B. kaber inhibited the germination of

Glomus spore. The pot with split-root system of Vierheilig et al. [

18] also reported that two non-AM host plants (

B. nigra and

Beta vulgaris L.) inhibited colonization by

G. mosseae in cucumber. From these previous studies, ITCs releasing from Brassica would be the primary effect on AM growth. Although, Brassica living roots do not actively release large amounts of ITCs because GSLs and myrosinase are compartmentalized in the cell. As long as this separation exists, ITC can be released only from injured cells where the spatial separation of GSLs and myrosinase is destroyed [

19]. Rumberger and Marschner [

20] reported that intact living canola roots continuously release a little amount of ITC via the outermost cell layers in rhizosphere, while the majority of root cells remain intact. This would be interesting to follow up in the future particularly where brassicas are being incorporated into the cropping cycle as biofumigants.

Brassica root residues incorporation into soil was the actual effect on the viability of AM spore resulting in reduction of AM infectivity. In Experiment 2, AM spore form two conditions; without and with root residues (cabbage, mustard and maize) incorporation was examined for its ability to colonize in maize roots. The infectivity of

Acaulospora,

Entrophospora and

Glomus of treatment without cabbage or mustard or maize incorporated were not different. These results showed previous crop with either AM host or non-AM host did not have effect on the AM infectivity if the root residues were removed. By contrast, when cabbage or mustard root was incorporated, it depressed AM infectivity. This might be due to larger amounts of ITCs can be released by the breakdown of the cells during decomposition of dead plant material or even faster by incorporating green plant material into the soil. Many studies have been reported that previous Brassica crop reduced AM root colonization and spore number in subsequent crop [

6,

7,

8].

Effect of Brassica root incorporated on AM fungal species was varied. Cabbage and mustard root incorporation depressed infectivity of Acaulospora, whereas, there was no effect on infectivity of Entrophospora. However, cabbage root incorporation only depressed infectivity of Glomus. This might be due to different types of ITC in root tissues of cabbage and mustard and ITC differ in their toxicity.

Three ITCs presented in cabbage roots, but there were two ITCs in mustard roots. 2-Phenylethyl ITC which have been reported as an effective biocide was presented 9.6±1.0 and 5.6±0.7 μg g

-1 fresh weight of cabbage and mustard, respectively. Another possible explanation might be larger amount of cabbage root dry matter. Thus, cabbage would release more ITCs to soil than mustard. Furthermore, Sarwar et al. [

21] found that 2-phenylethyl ITC (released from aromatic GSL) has been shown to be significantly more toxic to fungi than 2-Propenyl ITC (released from aliphatic GSL). ITCs produced by hydrolysis of aromatic GSLs such as 2-Phenylethyl is generally less volatile than aliphatic types and may therefore persist for longer in the soils [

22].

Incorporation with Brassica roots into soils delayed AM colonization at the early stage of infection. However, at D42, AM colonization did not differ between AM species. Incorporation with either Brassica or maize did not have effect on AM infectivity in maize roots. This result was in accordance with the study of Gavito and Miller [

23] who observed the maize following canola had significantly lower AM colonization for up to 62 days after planting after that the colonization was equal to maize following AM host species, bromegrass (

Bromus inermis Leys.) and alfalfa (

Medicago sativa L.). These observations suggest that AM populations can be built up and the inhibitory effects of a non-AM host crop can be reversed after cropping with AM host crop.