1. Introduction

Relevance. The present study attempts mathematical modeling and proposals of empirical applications based on the theory of public goods and methods of applied econometrics in industrial organization in the field of health care. In many countries of the world the state takes an active part in the formation and regulation of the market of health services [

1]. At the same time, in such countries as, for example, Russia, the state system guarantees free access of citizens to the majority of the most common services in the sphere of health care on the basis of application of the mechanism of compulsory health insurance [

2]. Profile authorities at the regional and federal levels are faced with the need to make decisions on the provision of medical services. We are talking about decisions related to the determination of the number of specialized doctors and medical staff, beds, as well as decisions in the field of personnel training, including the planning of the number of budgetary places in specialized educational institutions. But what is the basis for making decisions about the optimal number of doctors, for example, cardiologists, at the level of a particular region? To date, such decisions are made on the basis of federal regulations, which contain standardized average coefficients that determine the number of certain doctors per 100,000 people, taking into account the expected number of requests for medical services and the average appointment time [

3]. These coefficients do not sufficiently take into account the characteristics of territories, for example, socio-economic status, demographic characteristics of the population. It is also about the fact that the characteristics of territories can lead to variations in the extent to which the number of doctors can influence mortality from a particular disease, and even to estimate the average impact, other things being equal, it is necessary to take into account the presence of observed and omitted variables, reverse causality and other econometric problems [

4]. For example, according to Rosstat data, in the Penza region the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases is 749 per 100,000 people, with a cardiologist supply rate of 12.4 per 100,000 people, while in the Nenets Autonomous District the corresponding mortality rate is less than 348 per 100,000 people, with a cardiologist supply rate of 6.8 per 100,000 people in 2019.

The level of development of the region itself, its geographical location, proximity to the federal center and specialized educational institutions are also important in the context of explaining the existing level of medical personnel supply [

5]. In many respects, this will determine whether the region will be able to attract the necessary number of specialists for what is defined in the federal standards.

Thus, according to statistical data, there is a significant difference in the indicator of availability of cardiologists in the regions of the Russian Federation. For example, in such regions as the Jewish Autonomous Region, the Pskov Region, the Kurgan Region, and the Vologda Region, the number of cardiologists per 100,000 people is less than 6. And in such regions as the Astrakhan Oblast, North Ossetia, and St. Petersburg, the number of cardiologists per 100,000 people is more than 16 [

6].

The currently used approach also does not allow us to answer the question of how many specialists should be employed to maximize the indicator of public welfare. There is also no way to compare managerial decisions related to the choice between doctors of different specialties, or between hiring an additional cardiologist or building a crosswalk near a school to reduce child mortality from accidents.

At the theoretical level, the research problem is defined by the existence of a gap that arises when trying to answer the question of what should be the optimal equilibrium volume of medical services in order to maximize the indicator of public welfare. In this paper we assume that the state, striving to maximize the indicator of public welfare, will strive to form the volume of supply of medical services as close as possible to the optimal one. And due to the peculiarities of the market of services in the sphere of health care, for example, the existence of long waiting lists due to underfunding, here and further we will assume that the supply of services in the sphere of health care in the optimal volume from the point of view of maximizing the indicator of public welfare will lead to the establishment of the equilibrium level of production and consumption of relevant services on the market as close as possible to the optimal volume. The existence of this gap is due to the fact that the state-guaranteed access to free health services in some cases leads to the fact that these services begin to be fully or partially characterized by the properties of public goods [

7]. The state can strive for universal free access to health care because the consumption of health care services is a source of positive externalities, and thus without state guarantees or other forms of regulation, such as subsidizing health care services, underconsumption of health care services compared to the optimal level can be expected [

8]. On the other hand, the fact that health care services begin to be characterized by the properties of public goods leads to the fact that other well-known problems arise, for example, the problem of the stowaway, which creates the preconditions for underfunding of the health care sector within the mechanism of compulsory health insurance [

9]. For this and other reasons, the state has to make decisions both on the amount of additional financing of the health care sector and on the directions of spending the corresponding funds, which ultimately determines the volume of supply and, to a large extent, the equilibrium volume of specific medical services in the market under consideration.

In subsection 3.1 of this section we will consider a theoretical model for determining the optimal number of cardiologists based on the Samuelson equation [

10]. However, in order to apply it in practice, it will be necessary to estimate the utility of hiring additional physicians in monetary terms, in order to compare it with the corresponding costs. In doing so, estimating the utility in monetary terms would require, on the one hand, an estimate of the cost of living, which in turn can take into account both an estimate under other things being equal and an estimate taking into account its expected duration and quality [

11]. On the other hand, it is necessary to calculate the impact of the number of specialized physicians on the mortality rate from the respective disease area [

12]. This is what will be the main focus of this paper.

Research question: how will the mortality rate of the population from cardiovascular diseases change, all other things being equal, if an additional number of cardiologists is hired in the regions of the Russian Federation? The most common research results in the literature demonstrate the negative impact of the indicator of availability of specialized medical personnel on the mortality rate from specific disease areas [

13]. Such an impact can be explained by a significant reduction in the patient's waiting time in queues, which in turn can contribute to the receipt of timely medical care [

14]. The importance of timely medical care is also important in the context of the presence of expected transaction costs in the perception of the potential patient, which has a significant impact on his or her decision to seek medical care. For example, the more a patient believes that there are long waiting lists and other transaction costs associated with staff shortages, the more he or she will be motivated to come to the hospital later, which, other things being equal, increases the likelihood of an adverse outcome [

15]. Professional competition among specialists may also be important, so that in the case of an acute shortage of physicians with the relevant profile, they will have much less incentive to invest resources and make efforts to improve the quality of their work, for example by attending courses to improve their own qualifications, due to the fact that in the current conditions in the area, the employer will have an extremely strong incentive to retain the employee under any conditions.

In addition to the above-mentioned channels of influence of the level of medical personnel supply on the population mortality from the corresponding disease areas, it is important to emphasize the existence of conditions for the emergence of false positives and false negatives, which may lead to underestimation or overestimation of the corresponding influence and, to a certain extent, prevent the interpretation of the desired causal relationships.

False positives can occur for a variety of reasons, but they usually fall into one of the following categories: the presence of reverse causality, omitted variables, and peculiarities in the statistics used. In our case, the problem of reverse causality seems to be a significant one. The fact is that in some cases, in practice, there is even a positive correlation between the availability of medical personnel and mortality rates, which is largely due to the fact that in those areas where there is a high level of mortality from certain diseases, specialized authorities will try to increase the number of specialized medical personnel [

16]. At the same time, even if a negative impact is detected during modeling, there is always a risk that this impact is underestimated due to the fact that reverse causality may exist. The underestimation of the corresponding negative impact can also lead to the problem of missing variables, for example, the variable characterizing the level of well-being and lifestyle of the inhabitants of a given area [

17]. For example, it is known that a high income can lead to a person having a less physically active lifestyle, being more susceptible to the influence of bad habits, sleep disorders and being overweight [

18]. On the other hand, high income and the associated level of development of the area will contribute to a higher indicator of availability of medical personnel that characterizes the area [

19]. In combination, this will result in areas with both high mortality rates and high physician availability, creating a false-positive relationship. Existing inaccuracies in the statistical data may also lead to an underestimation of the negative impact of physicians on mortality. This may be due to the fact that in reality we do not observe the level of morbidity or mortality from a particular disease, but only indicators of detected morbidity or mortality. Thus, the availability of specialist physicians in an area has a greater direct effect on the recorded morbidity rate and a lesser effect on the recorded mortality rate. Therefore, it may be expected that areas characterized by a high availability of specialist physicians will be characterized by a higher level of recorded mortality from the corresponding diseases [

20]. On the other hand, high availability of specialists may in some cases be associated with false diagnoses, which may also contribute to an increase in detected morbidity and mortality in the area.

False negatives may also be associated with omitted variables. For example, in practice, it is quite difficult to assess factors related to cultural aspects that characterize the attitude of the inhabitants of a given territory towards their health at the regional level. At the same time, an attentive attitude of the inhabitants of the region to their own health can lead to the fact that they are more likely to lead a healthy lifestyle, for example, to eat properly, to lead a physically active lifestyle, which will contribute to the reduction of the indicator characterizing the mortality rate from a particular direction of the disease [

21]. At the same time, people who pay attention to their own health can also pay attention to issues related to the prevention of certain diseases, for example, in terms of early visits to doctors, which will also contribute to the increase in demand for medical services in the territory and create favorable conditions that contribute to the increase in the number of medical personnel [

22]. As a result, there will be areas with both low mortality and high availability of specialists, but it will not be the doctors themselves, but first of all the attitude of the population to its own health. Similar reasoning can be given when analyzing the influence of the parameter of the level of medical literacy of the population, which can not always be expressed as an indicator of the level of education in general [

23]. The indicator of the level of development of the territory can also act as a missing variable. On the one hand, a more developed territory is more likely to have high rates of availability of specialized doctors, while it is important to note that it is also more likely to have lower mortality rates, for example, due to preventive measures such as popularization of sports, access to quality food, medicines, opportunities to spend leisure time and organize quality recreation [

22]. These circumstances may also contribute to inaccurate estimates in the absence of relevant data.

The above-mentioned reasons for the existence of false-negative and false-positive relationships are prerequisites that can potentially lead to underestimation or overestimation of the influence of indicators characterizing the impact of the level of availability of medical personnel on indicators characterizing the mortality rate of the population from the relevant disease areas.

Scientific novelty of the study. First, an approach to determining the equilibrium volume of services in the sphere of health care on the example of the supply of cardiologists, which differs from the existing ones by comparing the benefits and costs of hiring additional doctors, allowing to ensure the maximization of the indicator of public welfare, as well as the possibility of comparing the returns of decisions related to the recruitment of doctors of different profiles, as well as costs of non-medical nature, leading to the saving of human lives. Secondly, an econometric model for assessing the impact of the indicator of medical personnel availability on the indicator of mortality from specific disease areas, using the example of cardiovascular diseases, which differs from the existing ones by using a quasi-experimental method of estimation based on the author's instrumental variables, allowing to overcome the influence of econometric problems, in particular the problem of reverse causality and missing variables. Third, an approach to the design of instrumental variables for the application of quasi-experimental econometric methods for solving the problems of causal impact estimation is formed, which differs from the existing ones by using various modifications of spatial matrices and spatial econometric methods, including those that allow us to form arguments in favor of their exogeneity.

Thus, this study is aimed at developing approaches to improve the accuracy of estimates that characterize the impact of the indicator of availability of specialized medical personnel on the mortality rate of the population from specific diseases, which in turn allows us to implement an approach to determine the volume of supply of services in the field of health care based on the comparison of benefits and costs of its provision. The accuracy of the relevant estimates may allow the use of management decision support systems, which, among other things, will significantly improve the efficiency and targeting of relevant decisions, due to the possibility of forecasting and comparing the impact, including at the interagency level.

Structure of the paper. In the section "Introduction" the field of the research problem is presented, the research question is formulated and the relevance of the work is outlined. The "Literature Review" section summarizes the key findings in the context of the research question. In the section "Methods" the description of the theoretical model is given, on the basis of which the approach to answer the question about the optimal volume of supply of services in health care using the number of specialized cardiologists as an example is proposed, the tools for its empirical realization are suggested, including the tools of applied microeconometrics, models of spatial econometrics, the data are described, and the justification of the quasi-experimental method used in the work is formed. The section "Results" describes the main indicators in regression equations obtained in the course of econometric modeling. The section "Discussion" forms the main limitations of the study, compares the obtained results with those already known in the literature, and provides a discussion of the directions of their application in practice. In the section "Conclusion" the main results are formed, the theoretical and practical significance of the study is assessed, and directions for further research are formed.

This study contributes to the theoretical literature that discusses approaches to determining the optimal level of service provision in quasi-public goods markets using the example of the market for health care services [

24,

25]. It also contributes to the literature in the direction of refining empirical methods for assessing the contribution of health care financing policies to reducing population mortality, using cardiovascular disease as an example [

26].

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Theoretical Model for Determining the Optimal Number of Physicians

Need for government intervention. The consumption of health services by the population leads to positive externalities. For example, healthier individuals are more likely to be more productive, start new businesses, make scientific discoveries, and achieve other successes that benefit the rest of society [

62]. The presence of positive externalities in consumption means that market equilibrium without government intervention will result in the amount of services consumed being less than the optimal amount in terms of maximizing public welfare. This happens because individual economic agents, when deciding to purchase and consume an additional unit of a good, consider only the personal utility received, which is less than the utility for the whole society, leading to underconsumption. There are various ways in which the government can intervene to correct such "market failures", such as subsidies [

63]. In practice, instead of subsidizing each individual patient, the state subsidizes medical organizations, which, together with the presence of compulsory health insurance, forms the contours of modern health care systems in countries with models similar to the health care system in the Russian Federation [

64].

Consequences of state intervention. In fact, the actions of the state lead to the fact that health services begin to be characterized by the properties of public goods. We are talking about characteristics such as non-excludability and non-competitiveness [

10]. The fulfillment of these characteristics can be interpreted in different ways. For example, non-excludability implies that it is impossible to provide a service to one consumer without providing it to all others, and to some extent universal free medical care implies this. On the other hand, the non-competitiveness property is satisfied in a more truncated form, because when a doctor sees a patient, he cannot see a second patient at the same time. In this case, the second patient is still seen, but at a later time, which in practice is characterized by long queues at the doctor's office [

65]. For such services, the concept of quasi-public services is often used in the literature [

25]. In fact, it would be more accurate to consider the system as a whole as a quasi-public good, rather than each individual service in the health care system. And as the main characteristic we can consider its throughput capacity per unit of time. For example, if there are 20 doctors working in the system, they can serve a larger number of patients with less waiting time than if there are only 10 doctors working in the system, all other things being equal. This is analogous to a public swimming pool with free access but queues. In the case of health care, the size of the system, i.e. its capacity, is determined to a greater extent by the state. In fact, we are talking about the equilibrium volume of services provided, and although it is determined by the interaction of supply and demand, the peculiarities of the market, combined with the fact that there is a deficit of services on the market, which can be confirmed by the presence of queues, leads to the fact that the state, by influencing the supply of services, for example by increasing the number of doctors, directly affects the equilibrium level of consumption. The state determines the interest rate that characterizes the level of payments to the mandatory health insurance funds and participates in the additional financing of the health care system [

66]. The role of additional financing is growing, in part because of the problem of "stowaways" resulting from free access to the health care system regardless of the patient's own contribution.

Approach to determining the optimal number of doctors. In the literature, it is common to use Samuelson's equation [

10] to determine the optimal quantity of public goods in the context of maximizing public welfare. According to it, the volume of public goods is considered optimal if the total marginal utility of all consumers is equal to the marginal cost of its production. It is assumed that the conditions are met, according to which an increase in the volume of public goods always leads to an increase in the utility of its consumption, but each additional unit leads to an increasingly smaller increase. In this case, the costs increase at an accelerated rate as the volume of public goods produced increases.

Let the production of health care services be determined by the required number of specialized doctors. All other costs related to medical personnel, equipment, and other infrastructure are determined by the number of doctors. That is, from the point of view of society, we have a cost function of the form (1) and a utility function of the form (2). Then, the public welfare indicator can be expressed by formula (3), and the condition for maximizing the level of public welfare is given by formula (4).

where, y is the number of physicians, through which the volume of services provided, the scale or throughput of the health care system is determined.

Formula (4) is a necessary and sufficient condition for maximization, in view of the corresponding properties of the cost and utility functions, namely v'(y)>0,v''(y)<0 and c'(y)>0 c''(y)≥0 for any y>0, c(0)=0. The economic interpretation of the introduced properties of the considered functions is as follows. Each additional physician will bring additional benefits, but the magnitude of these benefits will decrease. Even if the amount of equipment and other infrastructure also increases, the intuition may be that doctors will initially help patients with simpler diagnoses and treat more and more severe cases, so that each new doctor will face more difficulties, so that the contribution of each additional doctor to saving lives will decrease over time, although it will remain positive. In terms of costs, hiring an additional physician and providing him or her with a work environment will always incur additional costs, as more resources will be expended to find new qualified personnel. This may be due, for example, to the limited number of personnel in the area, which will require more effort and resources to attract new personnel, particularly to cover transportation and other transaction costs.

For simplicity, the utility function is given for society as a whole, without distinguishing between the utilities of individual patients and externalities. This is due to the fact that in practice it is rather labor-intensive to derive the utility functions of individual patients or the influence of external effects, and therefore the paper proposes an alternative way of estimating utility.

Let us give an economic interpretation of formula (4). If is fulfilled, it will mean that the last hired doctor still brings more benefits to society compared to the costs, and therefore, taking into account the considered properties, it is necessary to hire one more doctor, i.e. there is an underproduction of services in health care. That is, the indicator of public welfare can be increased by increasing the number of doctors. If is fulfilled, it will mean that hiring the last doctor has brought more costs to society than benefits and, therefore, there is an overproduction of services. And only at that number of doctors, when the equality of marginal utility and marginal cost functions is ensured, the maximization of the indicator of public welfare will be achieved.

In order to use formula (4), it is necessary to calculate the value of marginal cost, which is beyond the scope of this study, but does not seem difficult in any case, given the available information on current and potential costs. It is also necessary to obtain the function of marginal social utility, and here it is proposed to express it in the form of the product of the index characterizing the increase in the number of lives saved in case of hiring an additional doctor by the cost of one life saved. (

) (5). Then equation (4) takes on the form of (6). The question of estimating the cost of a life saved is also beyond the scope of this paper and can be considered both in a simple form, other things being equal, and taking into account its expected duration, qualitative characteristics, which is relevant, for example, when choosing between doctors of different profiles, medical procedures, and other alternatives.

The main empirical focus of this paper is to derive the death_heart_'(y) function. In the following, different model specifications are proposed that allow this. It is important to note that this function can be evaluated as a constant or as a function directly dependent on the number of physicians, e.g. allowing for the diminishing contribution of each additional physician. The most promising approaches include variants that allow the contribution of an additional physician to be estimated taking into account other indicators of the area, including socioeconomic and demographic characteristics.

3.2. Data

In order to answer the formulated research question, it is necessary to consider as a dependent variable the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases in the regions of the Russian Federation. In addition to assessing the direct impact of the variable characterizing the availability of qualified medical personnel, control variables will be considered in the modeling. The variables characterizing the level of alcohol and tobacco consumption, unemployment, education, poverty, the proportion of the elderly, the proportion of the urban population, the ratio of men to women, marriage and divorce rates, real income, air and water pollution, and the incidence of cardiovascular diseases will be considered as control variables in the basic version of the model. Other variables will be considered for additional checks, such as the variable describing the average CVD mortality rate in neighboring regions that share a common border with the region under consideration, as well as instrumental variables, which will be discussed in subsections 3.4 and 3.5.

More information about the variables used in the study and approaches to their calculation can be found in

Table 1.

The work uses data from 81 regions of the Russian Federation for the period from 2012 to 2019, for which the corresponding statistical observations are available for each year from 2012 to 2019 [

6]. The statistical characteristics of the used data are shown in

Table 2.

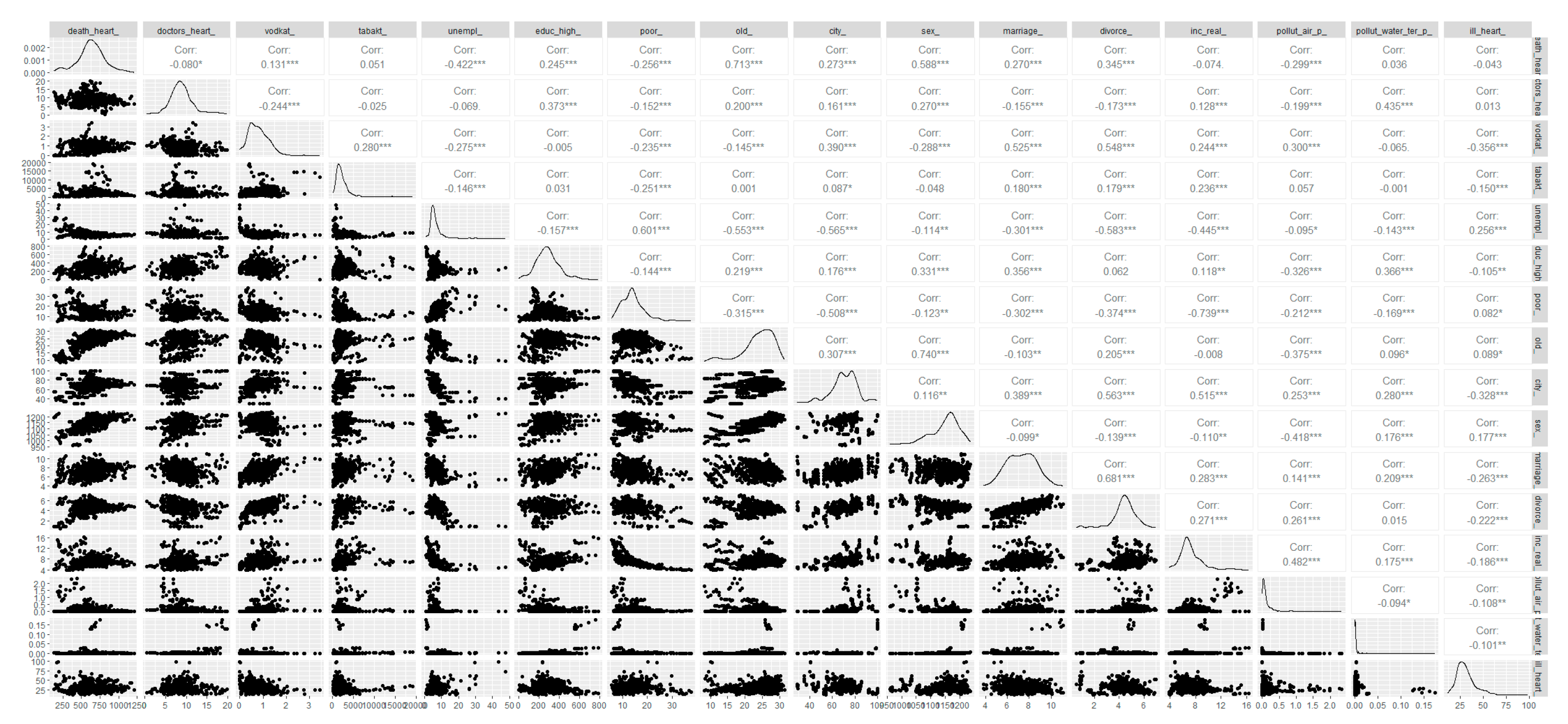

Figure A1 provides more detailed information on the statistical properties of the variables considered in the basic regression, including the correlation matrix and information on their distribution. High correlation values of 0.68 and 0.74 are observed between the variables characterizing the marriage and divorce rates, as well as between the variables describing the male-female ratio and the share of persons above working age, respectively. These results are to be expected given the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the population of the Russian regions, in particular the demographic pyramid. Although the indicators themselves are not critically high, this aspect is taken into account in the modeling, for example, by considering different specifications. The analysis of the distributions of key variables allows us to conclude that there are "heavy tails", in particular for the variables characterizing the mortality rate and the level of availability of cardiologists. In this case, we decided to use the logarithms of these variables, which, among other things, allows us to take into account the fact that the change in the mortality rate as a function of the recruitment of each additional physician may not be a constant, for example, depending on the current level of physicians.

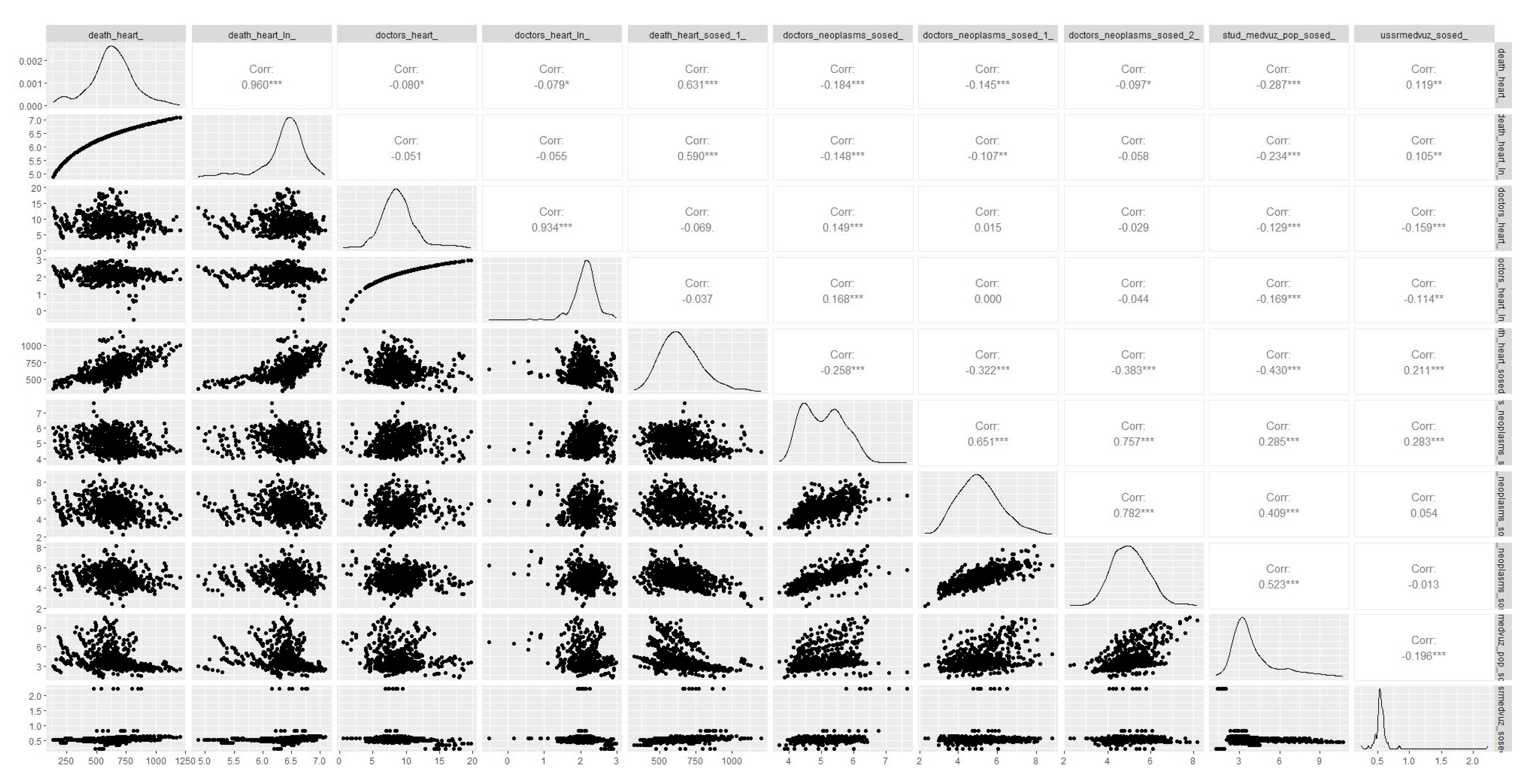

Figure A2 shows that after logarithmization, the corresponding variables became closer to normal. In fact, the logarithmic procedure allows us to estimate the impact of the variable in question as a percentage, but if necessary, we can always estimate the corresponding model without the logarithm and obtain an estimate of how many additional lives will be saved by hiring an additional cardiologist, including the effects of diminishing returns.

3.3. Models Considered

To obtain the function death_heart_'(y), it is first necessary to model the variable death_heart_, where the main attention will be given to the correct assessment of the influence of the variable characterizing the number of doctors on it. As previously demonstrated, there are a large number of reasons for underestimating or overestimating this effect, for example, due to the presence of prerequisites for the presence of false positive and false negative relationships due to the problem of reverse causality, missing variables, the specifics of the available data, etc.. Solving some of these problems is the main one. the main elements of the scientific novelty of this study. We will consider the following models, including those using the instrumental variable method (more details in subsection 3.3.4)

Linear models, where the contribution of each additional physician to the total number of lives saved is assumed to be constant:

- Spatial sampling regression model (m1.1)

- Versions of m1 using the instrumental variable method, namely considering the variables doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ (m1.2), stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_ (m1.3), ussrmedvuz_sosed_ (m1.4) as the instrument and simultaneously doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_, ussrmedvuz_sosed_ (m1.5).

- Version m1.1 within the panel data model with fixed effects on the territory without instrumentation (m1.6) and with instrumentation, where the variable doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ (m1.7) is considered as an instrument

where - regression coefficients, - random error, - characterizes the fixed effect of region i, independent of time

Nonlinear models that assume that the contribution of each additional physician to the total number of lives saved varies with all parameters of the function:

- Spatial sampling regression model (m2.1)

- Versions m2.1 using the instrumental variable method, namely considering the variables doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ ussrmedvuz_sosed_ (m2.2) and the same variables and their squares (m2.3) as an instrument, as well as the set of variables doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_, ussrmedvuz_sosed_ (m2.4) and a set of the same variables and their squares (m2.5).

- Version m2.1 within the panel data model with fixed effects on the area without instrumentation (m2.6) and with instrumentation, where the variable doctors_neoplasms_sosed (m2.7) is considered as an instrument.

Non-linear models, assuming that the contribution of each additional physician to the total number of lives saved may change as the number of physicians increases:

- Spatial sampling regression model (m3.1)

- Versions of m3.1 using the instrumental variable method, i.e. considering as the instrument the variable doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ (m3.2), stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_ (m3.3), ussrmedvuz_sosed_ (m3.4) and at the same time doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_, ussrmedvuz_sosed_ (m3.5).

- Version m3.1 within the panel data model with area fixed effects without instrumentation (m3.6) and with instrumentation, where the variables doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ and doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_ (m3.7) and doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_ and doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_ (m3.8) are considered as instruments.

In order to justify the exogeneity of the instrumental variables used, a model based on spatial econometrics (m4.4-m4.5) is evaluated, which tests for the existence of an association between the CVD death rate between a given region and its neighbors (for more details, see subsection 3.6). Specifications with an additional control variable death_heart_sosed_1 (m4.1) and specifications omitting highly correlated variables (m4.2-m4.3) are considered. In addition, specifications (m5.1-m5.9) with instrumental variables doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_ and doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_ are considered to demonstrate the argumentation aimed at interpreting their exogenous properties (more details in subsections 3.4 and 3.5).

3.4. Application of the Instrumental Variable Method

The use of the instrumental variables method is justified by the need to solve, at least partially, the problems that arise in the course of econometric modeling due to the presence of reverse causality, omitted variables, and the specificity of the data used [

62].

In practice, instrumental variables usually have two main requirements. They must satisfy the properties of relevance and exogeneity. The relevance property implies that the instrumental variable must have an effect on the variable whose effect on the dependent variable is to be estimated. In addition to theoretical justification, this property can be tested using various tests. In practice, the most commonly used test is the Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic (or F-statistic in first stage regression). The exogeneity property implies that the instrumental variable is not related to the dependent variable in any way except through the variable whose influence is estimated in the paper. This property is usually justified by economic intuition and is not directly tested. However, if there is at least one instrument whose exogeneity is not in doubt, other instruments can be tested for exogeneity using the Sargan test [

67].

This study evaluates the impact of the indicator of availability of specialized medical personnel - cardiologists - on the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases. In fact, it is necessary to find such instrumental variables that would have an impact on the indicator of availability of cardiologists, but would not be associated with the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases. The instrumental variables considered in this paper are: three different versions of the indicator characterizing the average level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions, calculated on the basis of different spatial matrices (more details on spatial matrices in section 3.3. 5) (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_, doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_), the average level of provision with medical students in neighboring regions (neighbors - all other regions of the Russian Federation) (stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_), and the average level of provision with medical institutions in neighboring regions in 1991 (neighbors - all other regions of the Russian Federation) (ussrmedvuz_sosed_).

Let us consider the fulfillment of the relevance properties for the instrumental variables under consideration. Will the relevance property be met? If there is a high availability of doctors, especially oncologists, around a region, it is more likely that this region will also have a relatively high availability of medical personnel. There may be a direct link, for example, it may be possible to attract personnel from neighboring regions. But there may also be unobserved factors that contribute to more favorable conditions for attracting physicians. For example, if the neighboring regions have a high number of cardiologists, then perhaps there are specialized educational institutions nearby, or in general, this cluster of regions has favorable conditions for attracting doctors, which could be due to geographical or even historical reasons. Similar reasoning can be applied to the variables characterizing the average level of medical students in neighboring regions and the average level of medical institutions in neighboring regions in 1991. Are the exogeneity properties satisfied? The main problem in this case is that there may be unobserved characteristics that characterize clusters of areas. For example, a high level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions may mean that this cluster of regions has a generally high level of development, and thus the same level of development determines both a high level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions and, for example, a relatively low level of mortality from CVDs in the region under consideration itself. This is an example of one of the channels showing that the instrument can be related to the dependent variable in a different way, which means that the exogeneity property is violated. The way in which the average level is calculated is also important, e.g. if we consider only a close circle of neighbors, it is more likely that exogeneity is violated, because closer areas are more likely to have the same characteristics (more on spatial matrices and the calculation of averages of indicators in neighbors in Section 3.3.5). The variable stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_, for example, has a similar problem because the level of endowment in neighboring regions may also affect both the number of medical students per capita and the level of endowment in the region under consideration, leading to a violation of the exogeneity property. In this regard, the instrumental variable ussrmedvuz_sosed_, which describes the average level of medical facilities in neighboring regions in 1991, seems to be the most promising. Due to the fact that the data describe the values of the corresponding characteristics of the territories 20 years ago, after which significant changes occurred both in the sphere of health care and in other spheres of the state structure, we can more confidently expect this variable to fulfill the exogeneity property. It is also important to recognize that the same instrumental variable properties may be satisfied when modeling on a spatial sample, but not when working with panel data models.

For example, if we consider stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_ as an instrumental variable in models with spatial sampling, we can expect the relevance property to be satisfied because, all else being equal, if a large number of medical students graduate from neighboring regions year after year, we can expect the level of care in the region under consideration to be relatively high. However, if we consider the same variable as an instrumental variable in models with panel data, at least one problem arises in the context of the relevance property, i.e. the influence of the instrument on the variable characterizing the level of supply of medical personnel in terms of lags. If the number of trainees has increased in a given year, it is unlikely that the number of physicians will increase in the same year.

On the other hand, when considering the instrumental variables doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_ and doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_, the exogeneity property may not be fulfilled for them in the case of working with models based on spatial sampling, as it was shown above, due to the presence of latent relationships between the quality of development of a group of territories, the level of mortality from CVDs and the availability of doctors both in the region under consideration and in the neighboring regions. At the same time, when considering models based on panel data, where relationships between changes in the relevant variables are important, the exogeneity property may already be fulfilled. For example, it can be assumed that certain events or latent factors may lead to an increase in the level of physician availability in neighboring regions over a short period of time, which in turn will affect the level of physician availability in the region under consideration, but will not have time to affect the level of CVD mortality through channels other than the indicator of physician availability.

Part of the confidence in the exogeneity of the variables used can be increased by attempting to test this property using the Sargan test, provided that there is no doubt about the exogeneity of the ussrmedvuz_sosed_ variable. This is particularly important when justifying the choice of the spatial matrix used to calculate the value characterizing the average level, for example, the provision of oncologists in neighboring regions.

Section 4 summarizes the results of the relevant checks, including a check for the presence of an interspatial relationship between regions for the indicator of mortality from CVD.

3.5. Spatial Matrices

Let us consider the algorithm of forming instrumental variables on the basis of different types of spatial matrices using the example of the indicator characterizing the average level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions. Spatial matrices characterize the weights used to calculate the average values of indicators in neighboring regions for a given region. The study considers three types of spatial matrices.

The first type: spatial matrix of regions of the Russian Federation, which provides information about neighboring regions that directly share a common border. That is, for each region all other neighboring regions are selected with equal weight. For example, if a region has only two neighbors, then when calculating the average level of a parameter in its neighbors, their arithmetic mean is taken.

The second type of spatial matrix is considered in a similar way, but the neighbors are both the nearest neighbors that have a direct common border and the neighbors that share a common border with the nearest neighbors, i.e., regions that share a common border with the region under consideration.

The third type of spatial matrix considers all other regions of the Russian Federation as neighboring regions. However, the squares of the inverse distances between the considered region and all other regions are considered as weights. Economic distances are considered as distances taking into account the presence of transport.

Accordingly, the first, second and third types of spatial matrices allow us to obtain weights for the calculation of the variables stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_1_, stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_2_, stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_, respectively.

3.6. Application of Spatial Econometric Methods

One of the reasons for the violation of the exogeneity of the considered instrumental variables may be the existence of a spatial relationship between mortality rates. There may be the following channel of the relationship between the instrumental variable and the dependent variable. For example, the value of the average level of provision of medical students in neighboring regions may directly affect the value of provision of medical personnel in neighboring regions, which in turn may affect the level of mortality, for example, from cardiovascular diseases in neighboring regions, and this indicator may be related to the mortality rate in the considered region. To test this hypothesis, additional specifications are considered.

Model (m4.1), which differs from model (m1.2) by adding another control variable characterizing the average death rate from cardiovascular diseases in the neighboring regions (death_heart_sosed_1_).

Model (m4.4), which will differ from model (m1.6) by the use of the Spatial AvtoRegressive Approach (SAR), which provides for the direct inclusion in the regression equation of a coefficient characterizing the presence of spatial autoregression, i.e. the influence of neighboring regions, based on a spatial matrix of weights of the third type [

68].

Model (m4.5), which will differ from model (m1.6) by using the spatial Durbin approach (SDM), which implies that the model takes into account the presence of spatial autoregressive relationships for both the dependent variable and all other variables [

69]. That is, the model assumes that the mortality rate in a given region is influenced not only by factors that characterize that region, but also by the level of mortality in neighboring regions (as in model m4.4), as well as by the average level of all other characteristics of neighboring regions.

where W is a matrix characterizing the spatial component in the model (third option, more details in subsection 3.3.5), ρ is a coefficient reflecting the presence of spatial effects.

Specifications m4.4 and m4.5 are designed to directly test the existence of an interspatial relationship for the dependent variable. Specifically, to answer the question of whether the level of CVD mortality in a given region depends on the average level of CVD mortality in neighboring regions. If there is no such relationship, this will allow us to be more confident about the exogeneity of the instrumental variables used. Although the M4.1 specification does not fully solve the endogeneity problem that may be present in the M1.2 model if the appropriate instrument is used, it may also increase confidence in the results if they are not significantly different.

4. Results

This section discusses the estimation results of the models proposed in the Methods section. In particular,

Table 3 summarizes the estimation results of the linear models considered. According to the estimation results of model m1.1, an increase in the supply of cardiologists by 1 person per 100,000 people will lead to a decrease in the mortality rate by 11.2 persons per 100,000 people. In other words, hiring one additional physician results in an average of 11 lives saved per year. According to the results of the model based on panel data m1.6, hiring an additional doctor leads to an average of 7.5 lives saved per year. However, the results of the models that attempt to solve the corresponding econometric problems show different results. In particular, model m1.5, which considers all three of the main instruments used in the study as instrumental variables, suggests that hiring an additional doctor leads to an average of 48 lives saved per year. These results confirm expectations about the underestimation of results in basic models that do not use quasi-experimental methods.

Consideration of more complex nonlinear models, in which the contribution of each additional physician to the total number of lives saved is no longer assumed to be a constant, also shows a similar underestimation in the absence of the instrumental variables method.

Table 4 summarizes the estimation results of nonlinear models in which the contribution of each additional doctor to the total number of lives saved is assumed to vary with all parameters of the function. Thus, according to the results obtained with the m2.5 model, a 1% increase in the level of availability of cardiologists leads to an average reduction of 0.7% in the mortality rate from cardiovascular disease, while in the models without the instrumental variables method the similar estimate is only 0.16% (m2.1) or 0.06% in the case of the model based on panel data without instrumentation (m2.6).

Table 5 shows the outcomes of the nonlinear models estimation. It assumes that as the number of physicians grows, the value of each added physician to the total lives saved can change. Based on the results of model m1.4 and m3.5, a 1% rise in the number of heart doctors, on average, causes a 0.7% drop in cardiovascular fatalities. At the rate of one cardiologist per 100,000 people, their impact on the number of lives saved is at least 129 per 100,000 people. With each unit increase in availability, that number decreases by 5 more people. Without employing instrumental variable methods, models m3.1 and m3.6 either vastly underestimate or have an unintuitive interpretation of the cardiologists' contribution.

In almost all cases where the method of instrumental variables was applied, both in the case of models based on spatial sampling and models based on panel data, identical results were obtained, which indicates the relative stability of the obtained results. The instrumental variable characterizing the average level of medical facilities in neighboring regions in 1991 (ussrmedvuz_sosed_) can be considered exogenous from the point of view of economic intuition to the greatest extent. Since it does not change over the period under consideration, it cannot be considered in models based on panel data, due to which we will consider models m1.5, m2.5 and m3 as the main models for interpreting the results. 5, where all the main instruments are considered, namely the average level of provision with oncology doctors in neighboring regions (neighbors are all other regions of the Russian Federation) (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_), the average level of medical students in neighboring regions (neighbors - all other regions of the Russian Federation) (stud_medvuz_pop_sosed_) and the average level of medical institutions in neighboring regions in 1991 (neighbors - all other regions of the Russian Federation) (ussrmedvuz_sosed_), which in turn, given our confidence in the exogeneity of the variable ussrmedvuz_sosed_ allows us to test the exogeneity of the other two instruments using the Sargan test. Thus, according to the Sargan test, in all three cases the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid instruments, i.e., uncorrelated with the error term cannot be rejected. For example, in the case of m2.5 model we have the following result (Hansen J statistic = 0.273, P-val = 0.8724)

The precision of the estimates of the impact of the remaining variables is beyond the scope of this study, since they were treated only as control variables. Quasi-experimental methods were not used in their estimation, so the results may be both under- and overestimated due to various econometric problems.

5. Discussion

Nonlinear models that take into account the dependence of the marginal effect of the level of provision with cardiologists on the population mortality from cardiovascular diseases on the socio-economic characteristics of the territory or at least the current number of personnel are more promising for obtaining the death_heart_'(y), function, for example, because they can take into account the decreasing marginal utility of medical personnel. Based on the results of the m3.5 model, we can represent the death_heart_'(y) function in the form (7).

Based on the m2.5 model, the marginal benefit of hiring an additional physician depends not only on the current number of physicians, but also on other characteristics of the area. This approach can be further developed in future studies. The results of formula (7), provided that there is a cost function characterizing the expenditures for attracting cardiologists and providing conditions for their work, as well as the existence of objective economic estimates of the cost of living [

70], allow us to determine the optimal number of cardiologists in the area. At the same time, if the region is operating in conditions of scarcity of financial resources, then the use of a similar approach to assess the marginal contribution of doctors of other specialties and even areas of financing not related to the health system, for example, related to the construction of safe crosswalks, can allow us to compare such decisions and make management decisions that contribute to maximizing the indicator of public welfare in the best possible way..

Robustness Check 1

One of the channels of violation of the exogeneity condition for the instruments used in this work, except for ussrmedvuz_sosed_, was the presence of interspatial relationship of the dependent variable. It is necessary to check whether the average CVD mortality rate in neighboring regions affects the CVD mortality rate in the region under consideration. In model m4.4, where spatial autoregressive analysis (SAR) is used to estimate the spatial relationship between the dependent variables, a positive relationship is directly demonstrated (spatial rho = 0.782***). However, there is reason to believe that this effect is not causal. In fact, considering the more advanced Spatial Darbin model leads to different estimates (Spatial rho = -0.146), i.e. the relationship is not statistically significant. This can be explained by the fact that the Spatial Darbin model takes into account not only the influence of the average mortality rate of neighboring regions on the region under consideration, but also the influence of the average level of characteristics of neighboring regions (SPATIAL X). Due to the fact that the SAR model does not take into account the influence of characteristics of neighboring regions other than the level of SWD mortality, and the spurious relationship arises. These results give more credence to the exogeneity of the instruments used.

In model m4.3, the instrumentation considered as a control the variable characterizing the average CVD mortality rate in neighboring regions (nearest neighbors), which did not change the results. Although this is not a sufficient condition for confidence in the exogeneity of the instrument, it allows us to believe with greater confidence in the presence of the necessary level of exogeneity.

The estimates in models M4.1 and M4.2 also allow us to verify that potential multicollinearity due to the variables characterizing the sex ratio, the proportion of elderly, the marriage rate and the divorce rate does not affect the results obtained in the study. In particular, the omission of some of these variables does not significantly change the results.

Robustness check 2

In some models, when applying the method of instrumental variables, not only the indicator characterizing the average level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions, where all other regions of the Russian Federation were considered as neighboring regions, taking into account the distance between them (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_), but also other versions of this indicator, in which other spatial matrices were used (for more details, see subsection 3.3.5). These are the indicator characterizing the average level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions, where regions sharing a common border are considered neighboring regions (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_), and a similar indicator where immediate neighbors and neighbors of immediate neighbors are considered neighbors (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_). In models based on spatial sampling, these tools produced different results. Thus, in the case of doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ (model m2.2), we can state that a 1% increase in the availability of cardiologists leads to a 0.7% decrease in CVD mortality, which is consistent with the main results of the study, while doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_ and doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_ provide an estimate of the contribution with a positive sign.

Our assumption is that despite the fact that all these instruments have relevance properties, i.e. they have an impact on the level of physician supply in the area under consideration, they differ in the degree of exogeneity. Presumably, the versions of the instrument calculated using only the nearest neighbors or the nearest neighbors and their neighbors are less exogenous than the version of the instrument using all other regions. This can be explained by the fact that neighboring areas are more likely to have common unobserved factors that simultaneously affect both the instrumental variable and the dependent variable in the model, which may lead to unintuitive results. If this hypothesis is true, the Sargan test should show it, at least for models where the instruments produce opposite results. This should require that we are reasonably confident in the exogeneity of the ussrmedvuz_sosed_ instrument.

These are exactly the results obtained using the Sargan test when estimating models m5.3, m5.4 and m5.5 in

Table 7. The Sargan test confirms the exogeneity only of the instrument doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, i.e. the variable characterizing the average level of availability of oncologists in neighboring regions, where all other regions of the Russian Federation were considered as neighboring regions, taking into account the distance between them.

Another interesting result is obtained in models based on panel data. There, the results when using all three instruments separately (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_, doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_, doctors_neoplasms_sosed_2_) show relatively close results, although even there the version of the instrument that considers only nearest neighbors as neighbors (doctors_neoplasms_sosed_1_) leads to estimates that differ from the expected results. At the same time, the Sargan test in the m5.8 model, provided we believe in the exogeneity of the doctors_neoplasms_sosed_ instrument, allows us to believe in the exogeneity of all three versions of this instrument when using models based on panel data. This can be explained by the fact that in these models it is the relationships between changes in the corresponding variables that are important. In this case, it is necessary to take into account lags. For example, relationships between changes in staffing rates in neighboring regions and in the region of interest may have shorter lags than similar relationships between the instrument and CVD mortality, which may explain the exogeneity of these instruments when considering models based on panel data, as opposed to models based on spatial sampling, where lags are not considered at all.

6. Conclusion

The study attempts to propose a theoretical and empirical approach to determining the optimal number of medical specialists in the region using the example of cardiologists. The theoretical approach is based on the Samuelson equation.

In the author's version of the theoretical model it was shown that, taking into account all the introduced economic parameters, such as the properties of the cost function, the maximization of the indicator of public welfare is achieved if such a number of doctors is hired that the marginal contribution of the last hired doctor to the growth of the public utility function is equal to the marginal cost of hiring him, taking into account the cost of providing conditions for his work. It was proposed to calculate the marginal social utility function as the product of the indicator characterizing the increase in the number of lives saved in case of hiring an additional doctor at the cost of one life saved.

The main empirical result consists in the econometric modeling of the indicator of mortality from cardiovascular diseases to obtain the function describing the increase in the number of lives saved in case of hiring an additional doctor. As part of the answer to the question of how the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases will change, all other things being equal, if an additional number of cardiologists is hired in the regions of the Russian Federation, various model specifications were constructed and evaluated, which were designed primarily to solve the main econometric problems. The causes of econometric problems leading to potential underestimation or overestimation of relevant causal relationships were described on the basis of reverse causality phenomena, omitted variables, and the specificity of the data used. The main approach to solve these problems was the application of quasi-econometric methods, in particular the instrumental variable method.

In order to apply the instrumental variable method, an approach to the construction of instrumental variables was formed, which differs from the existing ones by using various modifications of spatial matrices. Strategies of justifying the exogeneity of the instrumental variables used, including on the basis of spatial econometric methods, were considered separately.

Based on the findings from linear models, adding another doctor results in saving an average of 48 lives annually. Nonlinear models using logarithmic function reveal that a 1% boost in cardiologists' accessibility leads to an average decrease of 0.7% in cardiovascular deaths. Using a model that accounts for varying contributions of each additional doctor to the total number of lives saved, we found that when 1 cardiologist is available per 100,000 people, their impact on the number of lives saved is at least 129 per 100,000 people. This decreases by 5 people for every unit increase in availability beyond that level. This is over three times higher than the estimates in the base models, which didn't use the instrumental variable method.

These results allowed us to obtain estimates of the marginal social utility function of hiring additional cardiologists, which, together with the cost function and cost-of-living estimates, allow us to determine the optimal number of cardiologists in the area. If the region is operating under conditions of scarcity of financial resources, the estimates of the marginal contribution of physicians of other specialties and even non-health care financing areas can allow to compare such decisions and to make management decisions that contribute to maximizing the indicator of public welfare in the best possible way. The latter determines the practical relevance of the study, which lies in the possibility of developing evidence-based health policy tools.

In further research, it is necessary to estimate more rigorously the function of the marginal public utility of hiring and providing conditions for the work of additional medical personnel, in particular, on the basis of the development of models that take into account the dependence of the marginal contribution of doctors in reducing the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases on the characteristics of the territory itself, for example, on the basis of the approach proposed in this paper on the basis of nonlinear models using logarithmization. The correctness of the proposed algorithms of formation and justification of the possibility of using the instrumental variables used in this paper on the basis of different spatial neighborhood matrices are also to be evaluated.