1. Introduction

The development of edible active packaging films and coatings is the result of the modern age sustainability and circular economy spirit intrusion to the food packaging sector of the food industry [

1,

2,

3]. Additionally to the common food packaging properties, an active packaging film and/or coating interacts with the food to enhance the preservation and shelf-life [

4,

5]. By using edible active packaging films and coatings instead of films based on common fusel polymers in food industry, the target of reduced food waste and reduced CO

2 fingerprint is achieved.

Starch, chitosan, gelatin, pectin, and alginates are the most used biodegradable biopolymers to the development of edible active films and/or coatings [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Alginates chemical group is consisting of alginic acid and alginate salts such as sodium alginate (E401), potassium alginate (E402), ammonium alginate (E403), and calcium alginate (E404). These alginates are naturally occurring indigestible polysaccharides which are commonly produced by and refined from various genera of brown algae. Alginates are composed of the unbranched, linear, binary copolymers -D-mannuronic acid (M) and -L-guluronic acid (G) which are linked by 1–4 glycosidic bonds [

10,

11]. Alginic acid and calcium alginate are insoluble in water while sodium alginate, potassium alginate, and ammonium alginate are water-soluble polymers. Alginates are considered as the most promising candidates to be applied as edible active food packaging and coating in food packaging sector. The main reason is that the European Commission (EC) listed alginic acid and its salts (E400–E404) as an authorized food additive. Thus, alginates are widely used in various food industries as a thickening agent, stabilizer, emulsifier, chelating agent, encapsulation, swelling, a suspending agent, or used to form gels, films, and membrane [

11,

12]. Among alginates sodium alginate is the most common salt of alginate used for edible films and coatings [

11].

Essential oils (EOs) and their derivatives are phytochemicals which are widely applied in active food packaging in the last decade due to their natural abundance and their significant antioxidant and antimicrobial activity [

13,

14,

15]. To avoid the quick loss of EOs antioxidant and the reduce of the antimicrobial activity, due to their volatile nature, recently it was suggested to adsorb them in nanoclays such as bentonite and halloysite. The produced nanohybrid materials were controlled the release of the EOs out of the food packaging film [

16,

17]. Halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) belong to the kaolin groups and are aluminosilicate, clay-based nanotubes. They are of the most utilized nanoclays for the production of active food packaging materials [

17]. HNTs are typically 0.2–1.5 μm in length, while the inner and the outer diameters are ca. 10–30 nm and 40–70 nm respectively. HNTs are nanostructured materials (at least one dimension in the range of 1–100 nm) [

18] Their advantages are the lack of toxicity, their low cost, and their biocompatibility. The unique tubular structure (Fig. 1a) is render HNT a desirable nanofiller material for sustainable packaging and a carrier for active compounds such as EOs and other phytochemicals.

Tsalafouti is an artisanal Greek traditional cheese, potential for nomination as Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) product and capable to significantly boost local entrepreneurship [

19]. Greek traditional methods for cheese production are multiple and diverse. Tsalafouti stands out for its unique preparation method and for its sensory properties. Greece already produces 23 cheeses with PDO certification, and 50 other well-known traditional varieties. Until nowadays, Tsalafouti could be categorized as a lesser-known Greek cheese. Nevertheless, it exhibits a substantial increasing potential for commercial acknowledgement. Its unique organoleptic characteristics, combined with its potential for value-added commercialization, are making it a food with ambitious candidacy for receiving the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status. PDO status would not only establish Tsalafouti as a prestigious, certified Greek cheese but also would affirm its distinct regional identity and its quality attributes. Thus, Tsalafouti will be transformed from a local unknown regional product to a well-known product of marked distinction and gastronomical importance [

20].

Produced locally in the Greek mountains, using ovine milk during the summer's end lactation period, Tsalafouti is an acid-curd cheese that possesses a soft, spreadable texture, a consistently white color, and a mildly acidic, sour, and refreshing taste [

21]. The production process is based on spontaneous acid fermentation by indigenous microorganisms, given that no starter culture or rennet is added. Traditionally, this cheese was stored in caves under running water for several days to acidify. Its compact texture typically comes through isoelectric precipitation of casein micelles due to the lowering of pH. This process initiates by the milk's native microorganisms under the microclima of the maturation environment [

19]. Sensory evaluation has shown that Tsalafouti retains its organoleptic properties for up to 45 days [

21]. Tsalafouti wasn’t tested with edible coatings until recently, and thus, this study was an innovative research start for such cheese conservation.

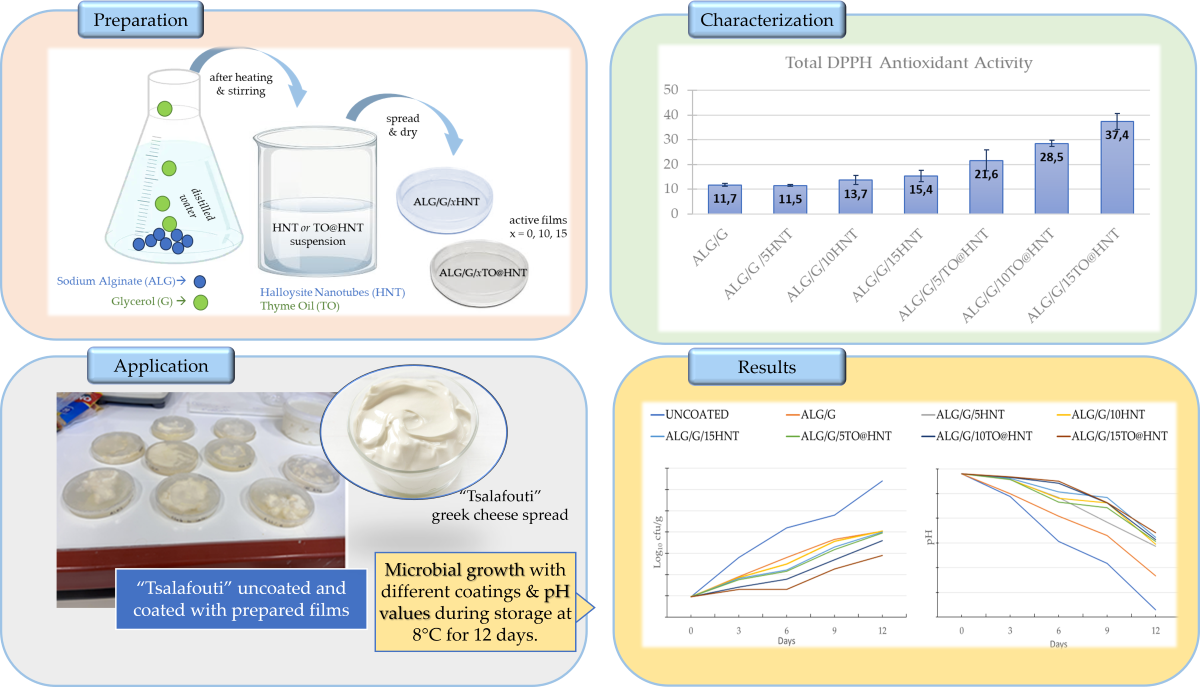

A recent study presented the development of rich in thymol TO@HNT nanohybrid via a green distillation-evaporation/adsorption process [

22]. The developed TO@HNT nanostructure was then incorporated successfully to a chitosan/polyvinyl-alcohol matrix in one project and to low density polyethylene matrix in another. Results of both projects were promising for development of active coating. Such coatings and active films were tested for kiwi-fruits preservation and for fresh pork fillets preservation respectively [

22,

23]. In this work, the performance of such TO@HNT hybrid nanostructure in a sodium alginate/glycerol (ALG/G) matrix was studied. TO@HNT nanohybrid dispersed homogeneously into an ALG/G aquatic solution at 5, 10, and 15 final nominal wt.% concentgration to obtain ALG/G/xTO@HNT (x=5, 10 and 15) active films/coatings. Pure HNT also incorporated into the ALG/G aquatic solution at 5, 10, and 15 final nominal wt.% concentration to obtain ALG/G/xHNT (x=5, 10 and 15) active films/coatings for comparison. Both obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films were characterized physiochemically with X-Ray diffraction (XRD) analysis and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Tensile, and water/oxygen barrier properties as well as antioxidant activity of the obtained films were also studied. According to the evaluation results based on all studied properties, the obtained optimum ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films were applied as coating in fresh Tsalafouti cheese. Specific novelty points of the current study are: (i) The preparation method and the characterization results of such novel ALG/G/xTO@HNT active films which are reported for the first time, (ii) results from application of such novel ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as edible active coating on “Tsalafouti” type spreadable cheese to extend shelf life first time which are reported also for the first time.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD analysis of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

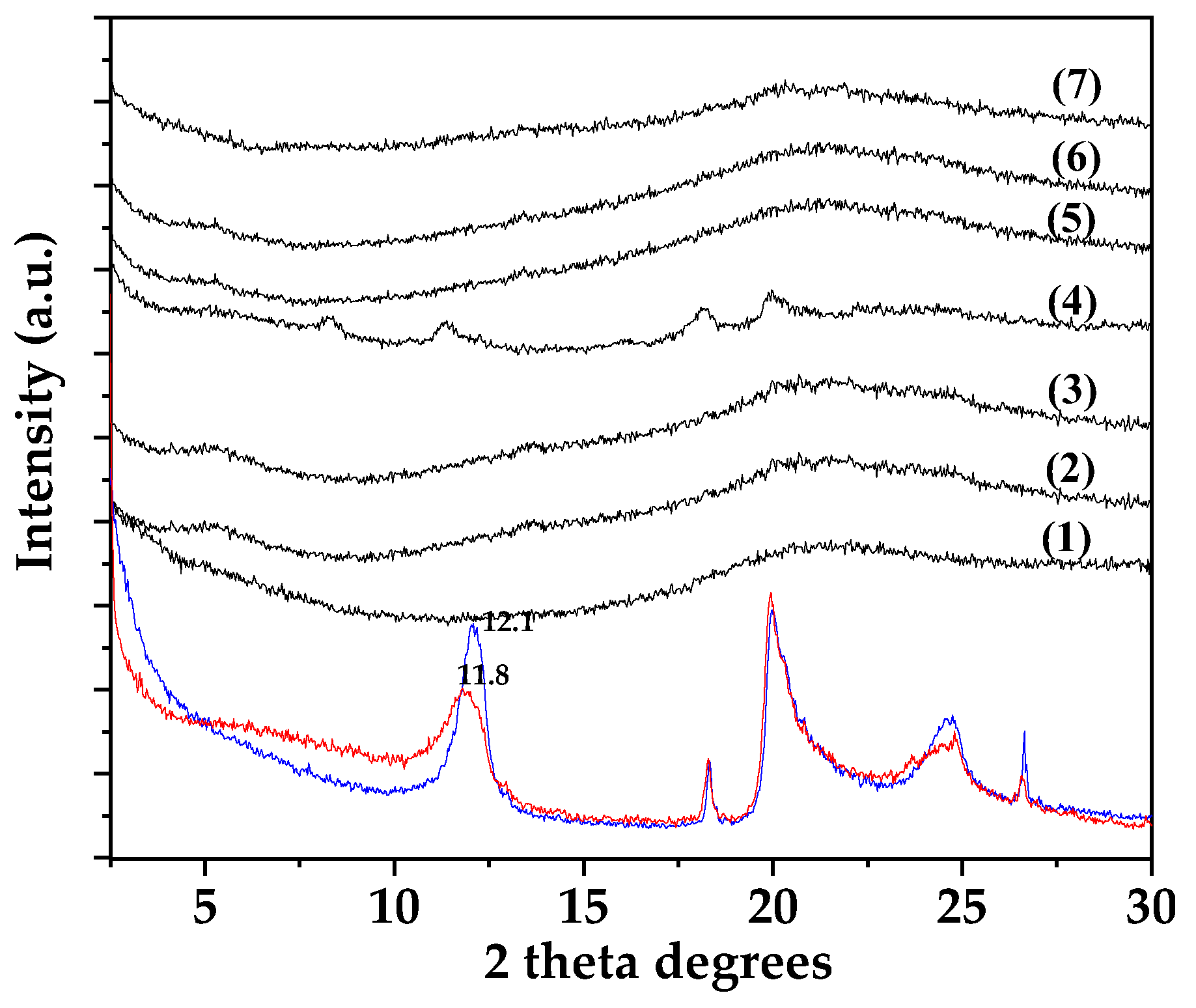

In the

Figure 1 the XRD plots of pure HNT powder (black line) and TO@HNT nanohybrid powder (red line) in the range of 2-30

o 2 theta are shown. In the same

Figure 1 the XRD plots of pure ALG/G film (line (1)), all ALG/G/xHNT films (lines (2), (3), and (3)) and all ALG/G/xTO@HNT films (lines (4), (5), and (6)) are also shown for comparison.

According to previous reports [

22,

23] in both pure HNT and TO@HNT XRD plots (see black and red line plots in the bottom of

Figure 1) and the characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 12.0, 20.1, and 24.6 2 theta are corresponded to (001), (100), and (002) planes of Halloysite nanotube crystal structure [

22]. A small decrease of approx. 0.03

o of HNT basal spaycing indicates probably the insertion of small water molecules in HNT’s interlayer space [

22].

In the case of pure ALG/G film XRD plot (see line (1) plot in

Figure 1) the broad peak with central position at 2θ = 21.6 is corresponded to the amorphous structure of alginate [

24].

In the case of all ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films XRD plots no change in the characteristic peak of ALG/G characteristic peak at 21.6

o is observed implying that the addition of both HNT and modified TO@HNT do not affect the amorphous phase of ALG/G matrix. In advance, the characteristic peaks of HNT crystal structure dissapeared in all cases except of the case of ALG/G/15HNT film. This indicates the high dispersity of both HNT and TO@HNT in ALG/G matrix. Higher dispersity is achieved by the modified TO@HNT nanohybrid in comparison to the pure HNT [

22].

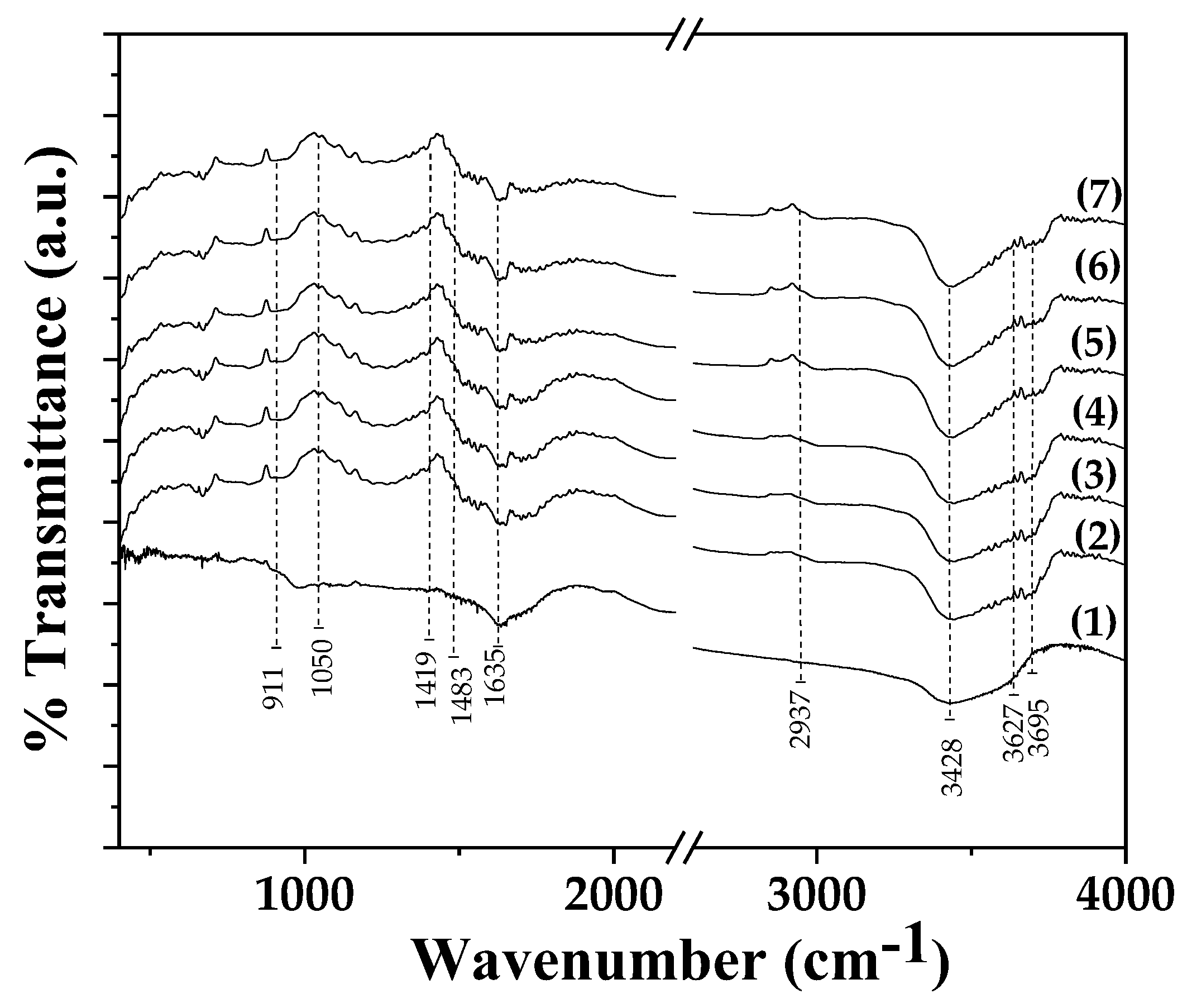

2.2. FTIR spectroscopy of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

FTIR plots of pure ALG/G film as well as from all ALG/G/xHNT and all ALG/G/xTO@HNT films are shown in

Figure 2 for comparison.

In all plots the characteristic sodium-alginate peaks are observed. The broad band at 3428 cm

-1 is assigned to the streching vibration of hydrogen-bonded O–H groups [

24,

25]. The band at 1635 cm

-1 is assigned to the asymmetric stretching vibration of COO groups, the band at 1419 cm

-1 to the symmetric stretching vibration of COO groups, and the band at 1050 cm

-1 to the elongation vibration of C-O groups [

24,

25].

In the case of HNT and TO@HNT based films in FTIR plots the characteristic peaks of HNT are also observed among with sodium alginate bands. More specifically, the band at 911 cm

-1 is assigned to the bending vibration of Al–O–OH group bonds of HNT [

26,

27]. The band at 3695 cm

−1 is assigned to the streching vibration of O-H group bond of HNT [

26,

27]. In addition, the peak at 1483 cm

-1 is assigned to the deformation vibration of Si-C bond of HNT, the band at 2937 cm

-1 is assigned to the streching vibration of C-H bond of HNT and the band at 3627 cm

−1 to the streching vibration of N-H bond of HNT [

26,

27].

With a careful glance, it is obtained that the main difference between FTIR plots of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT is that in the case of all ALG/G/xTO@HNT FTIR plots the band of O-H group stretching at 3428 cm

-1 is more intense than the same band of all ALG/G/xHNT FTIR plots. This implies a higher interaction between OH groups of the ALG/G matrix and OH groups of modified TO@HNT nanohybrid than OH groups of the ALG/G matrix and pure HNT OH groups. Thus, FTIR in accordance with XRD suggested a higher dispersion of modified TO@HNT nanohybrid in ALG/G matrix than pure HNT in ALG/G matrix [

22].

2.3. Tensile properties of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

The calculated Elastic Modulus (E), ultimate stregth (σ

uts), and %elongation at break (ε%) values of all ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as well as pure ALG/G film are listed in

Table 1 for comparison.

As it is obtained from

Table 1 in the case of ALG/G/xHNT addition of 10 and 15 wt.% content of pure HNT in the ALG/G matrix results in a significant increase of stress and strength values and a decrease of elongation at break values. This behavior is indicative of successful addition of nanoclay in polymer/biopolymer matrix results in nanocomposite films. In the case of 5wt.% addition of HNT in ALG/G matrix a significant decrease of stress and strength values among with a significant increase of %elongation at break values is obtained. Although these result are somewhat peculiar, similar trends have been documented previously in the addition of sodium montmorillonite (NaMMT) nanoclay in chitosan/glycerol matrix [

28,

29]. It has been founded that the addition of 2.5 wt% NaMMT was associated with the more homogenous distribution of water and glycerol across the system, resulting in better plasticization effect in resulted nanocomposite films. On the contrary in the case of all ALG/G/xTO@HNT films the addition of all wt.% contents of TO@HNT results in nanocomposite films with higher stress-strength values than pure ALG/G film. In addition, the obtained %elongation at break value of ALG/G/5TO@HNT film is higher than ALG/G film, while for ALG/G/10TO@HNT and ALG/G/15TO@HNT films the %elongation at break values are lower than ALG/G film. In advance, for ALG/G/10TO@HNT and ALG/G/15TO@HNT films the %elongation at break values is higher than the %elongation at break values of ALG/G/10HNT and ALG/G/15HNT films correspondingly. Thus, combining the tensile properties results it is obtained that addition of TO@HNT in ALG/G matrix results in “stronger” nanocomposite films in accordance with the higher interplay of TOHNT with ALG/G matrix mentioned hereabove in FTIR and XRD characterization results. It also obvious that the TO molecules act as plasticizer which boosts the plasticization of obtained nanocomposite films [

30,

31,

32].

2.4. Water/Oxygen barrier properties ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

In the

Table 2 the calculated WVTR and OTR values of all ALG/G/xHNT and all ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as well as pure ALG/G film are listed. From these values the Water Vapor Diffusion coefficient (D

wv) and oxygen permeability (Pe

O2) values have been calculated and listed for comparison.

As it is obtained from the D

wv values on

Table 2 the water vapor diffusion coefficient of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films is decreased in comparison of D

wv value of pure ALG/G film except the D

wv value of ALG/G/5HNT film. Higher D

wv values decrease is achieved for TO@HNT based films than HNT based film due to the hydrophobic nature of TO. The lowest D

wv values are achieved from ALG/G/10TO@HNT and ALG/G/15TO@HNT films.

PeO2 values of all ALG/G/xHNT films and all ALG/G/xTO@HNT films are lower than PeO2 values of pure ALG/G film. ALG/G/xTO@HNT films achieve lowest PeO2 values than the ALG/G/xHNT films. The lowest PeO2 values achieved from ALG/G/10HNT and ALG/G/10TO@HNT films.

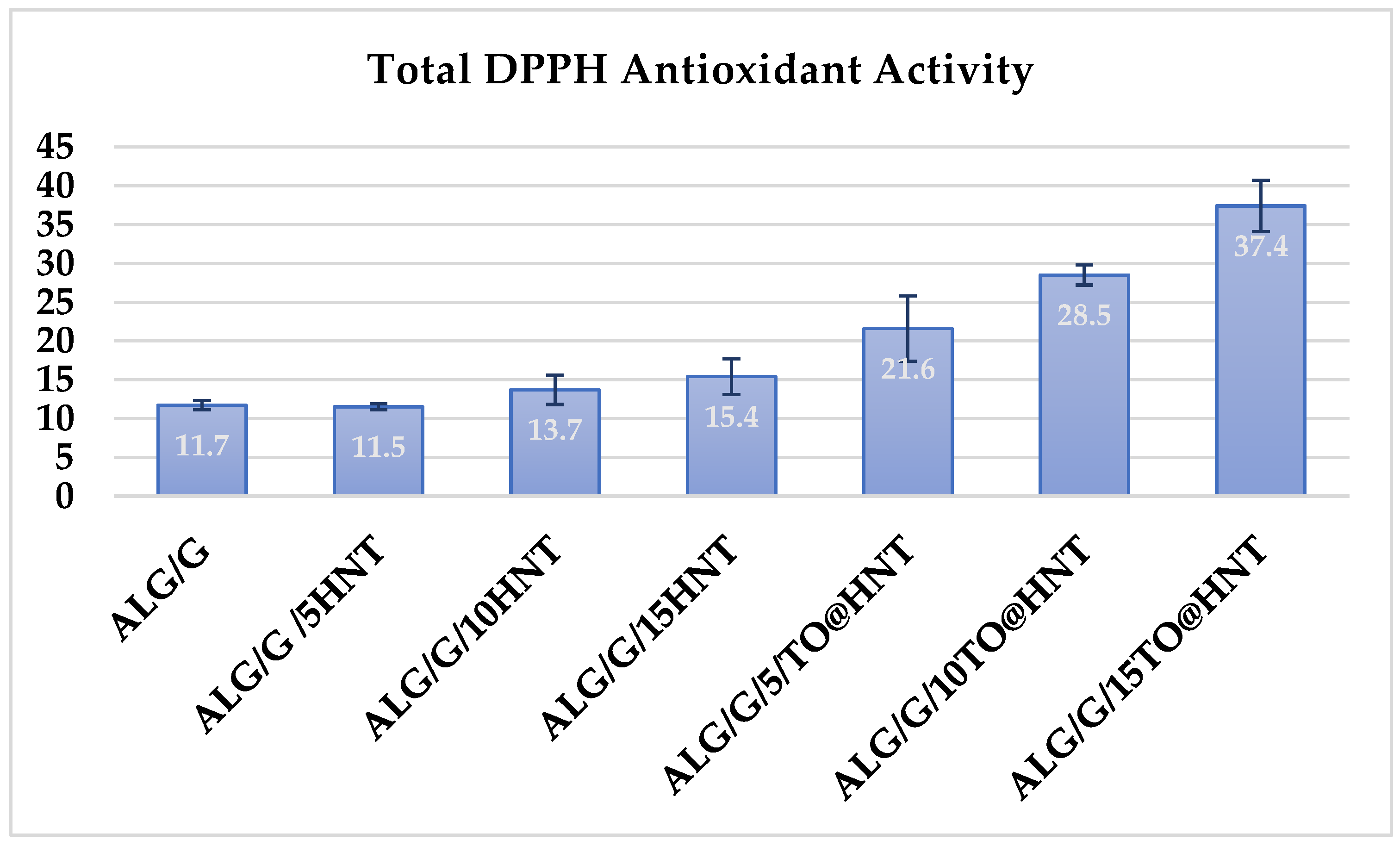

2.5. DPPH assay total antioxidant activity values ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

In the

Figure 3 the calculated total antioxidant activity values of all ALG/G/xHNT and all ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as well as pure ALG/G film are listed for comparison.

Small antioxidant activity values are obtained for all ALG/G/xHNT film as well as for pure ALG/G film due to the antioxidant properties of sodium alginate chain. All the TO@HNT based films exhibited significant antioxidant activity due to the presence of TO molecules. Antioxidant activity of ALG/G/xTO@HNT film is increased as the wt.% content of TO@HNT is increased.

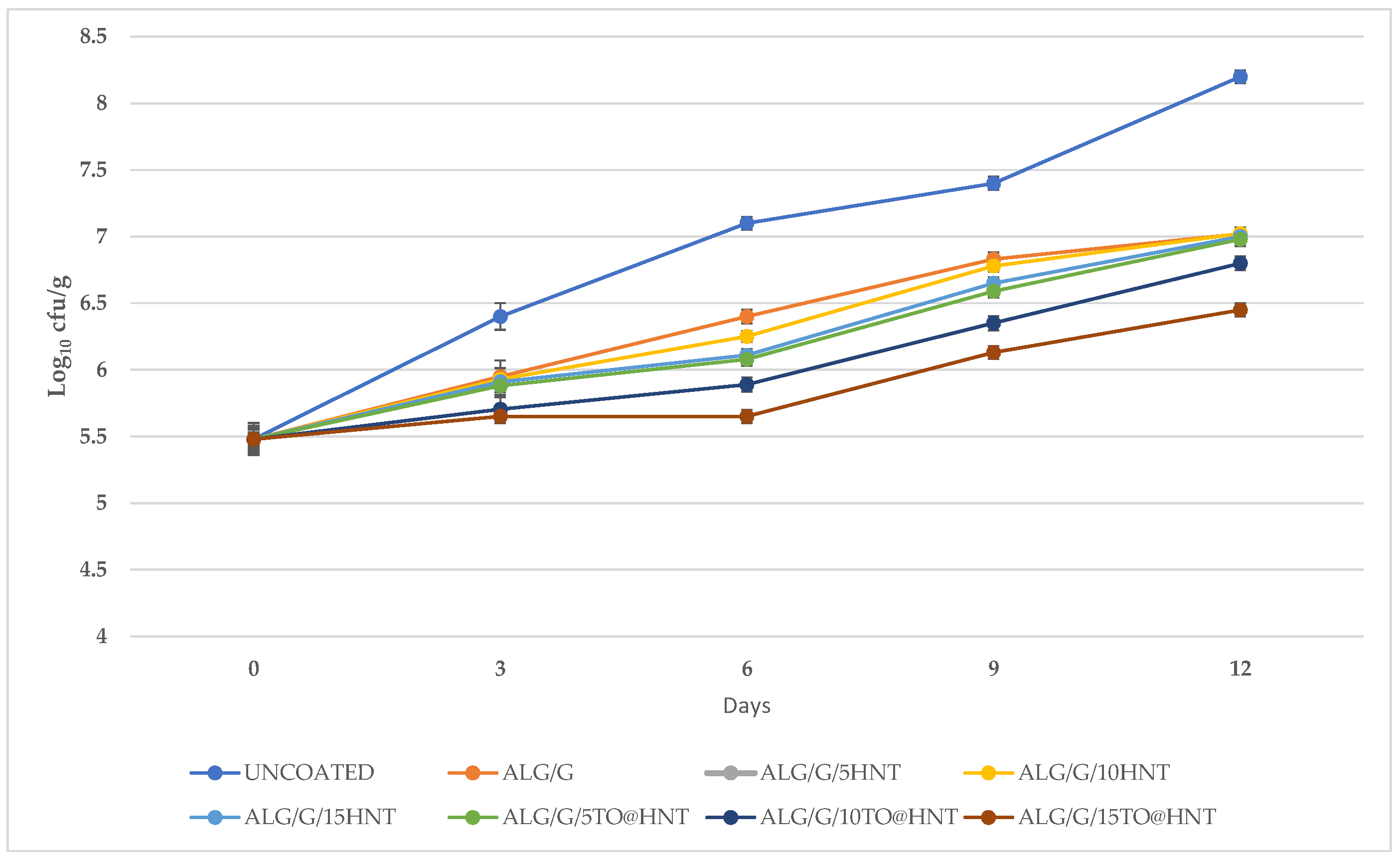

2.6. Application of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT as active coatings to preserve “tsalafouti” type spreadable cheese.

All ALG/G based films tested above, were used as active coatings to assess their efficacy in protecting “tsalafouti” spreadable cheese against mesophilic microbial population growth. Throughout the 12-day experimental period, microbial enumeration for different Tsalafouti cheese samples, both coated and uncoated, illustrated a discernible trend. All samples recorded an escalation in log10 cfu/g values, a marker indicative of bacterial proliferation. The uncoated sample exhibited the most pronounced growth, escalating from an initial 5.48 log10 cfu/g to a final count of 8.20 log10 cfu/g on Day 12 (

Figure 4).

For the coated samples, the upward trend persisted, albeit with variable rates of microbial proliferation dependent on the specific coating type. The final log10 cfu/g values for ALG/G, ALG/G/5HNT coatings ranged between 7.00 and 7.02. Despite their continued growth, the ALG/G/10HNT and ALG/G/15HNT coatings yielded marginally lower final values, 7.00 and 6.98, respectively. The ALG/G/5TO@HNT and ALG/G/10TO@HNT coatings demonstrated a more controlled rate of microbial growth, with final log10 cfu/g values falling between 6.80 to 6.45. Most notably, the ALG/G/15TO@HNT coating culminated with the lowest final microbial count, reporting a log10 cfu/g value of 6.27. This result posits the ALG/G/15TO@HNT coating as the most effective in managing bacterial proliferation among all tested coatings.

Significantly, the results reflect a reduction of more than one log10 cfu/g unit across all samples when comparing the initial microbial count to the anticipated growth in the absence of coating. This finding indicates a significant role of the coatings in inhibiting microbial growth in Tsalafouti cheese over time. The results are in line with other relative studies which demonstrated that alginate sodium coatings enhanced with clays or essential oil offer a log10 cfu/g reduction [

24].

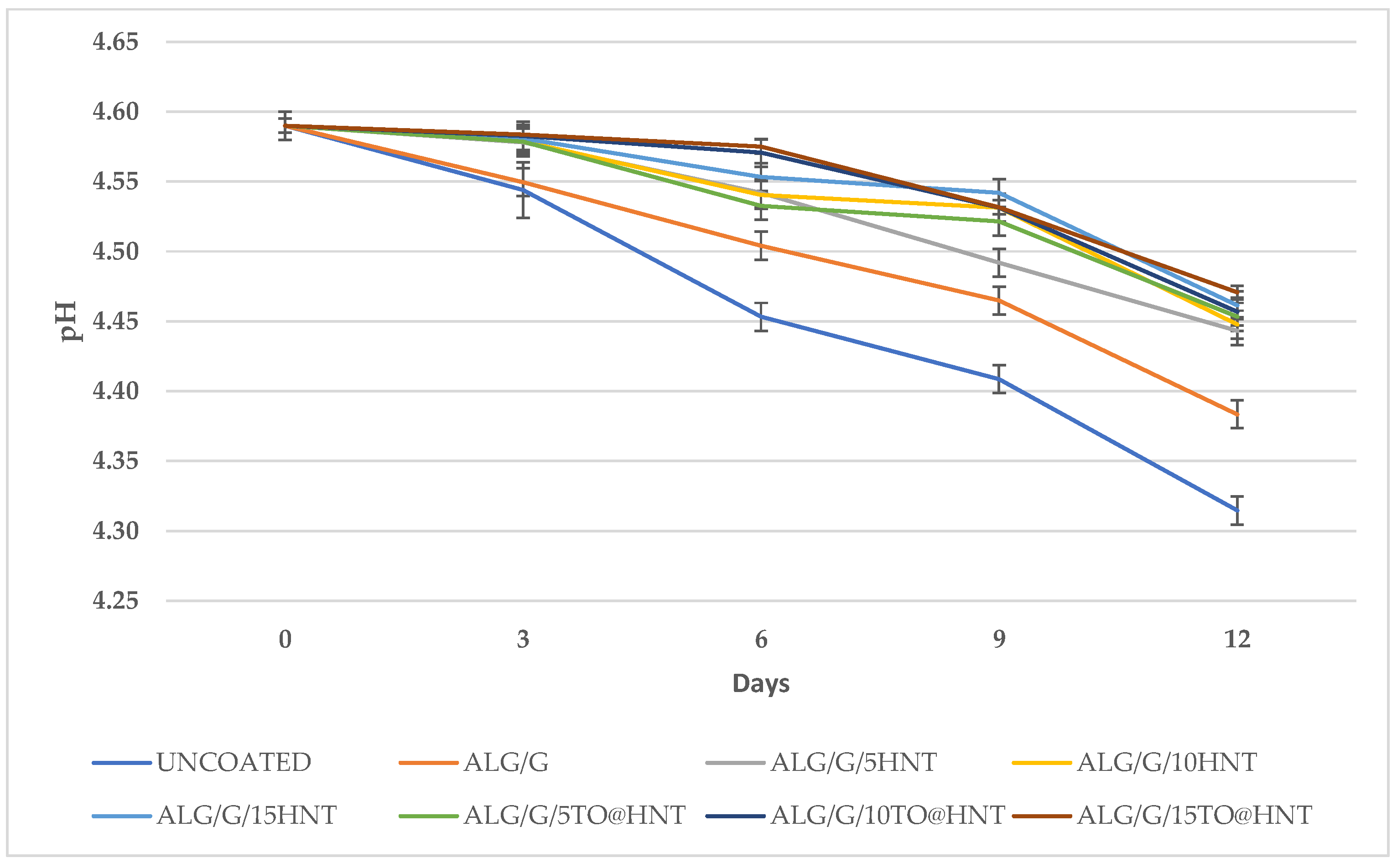

Moreover, the results presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 5 illustrate the pH changes in Tsalafouti soft cheese during 12 days of storage at 8 °C, under various alginate-based coatings enriched with halloysite nanotubes (HNT) and thyme oil (TO), applied at levels of 5, 10, and 15%. Across all samples, there's a noticeable decrease in pH, indicative of the production of galactic acid. The uncoated cheese displayed the most significant reduction in pH, whereas the alginate-based coatings resulted in a more gradual decline. Among the HNT and TO coatings, higher concentrations tended to maintain slightly higher pH levels. This pattern might imply a potential delay in microorganism population growth, especially at 10 and 15 wt.% contents of HNT and thyme oil. These findings emphasize the role of coating type and concentration in influencing pH and, by extension, microbial stability, offering a promising avenue for optimizing cheese preservation and quality.

The pH of the uncoated cheese, which served as the control in this experiment, decreased from 4.59 on Day 0 to 4.315 on Day 12. The decrease in pH indicates an increase in acidity, which is frequently associated with the proliferation of lactose-consuming microorganisms, such as lactic acid bacteria. As these microbes metabolize lactose, they produce lactic acid, lowering the pH and thereby indicating their proliferation and growth.

During the same 12-day period, all coated cheese samples maintained higher pH levels, indicating less microbial activity. The specific coatings appear to effectively inhibit the growth of microorganisms, as evidenced by the smaller pH decrease observed in coated cheese compared to uncoated cheese. Among the coated samples, the ALG/G/15HNT, ALG/G/10TO@HNT, and ALG/G/15TO@HNT coatings maintained the highest pH levels on Day 12, indicating that these coatings may be the most effective at inhibiting microbial growth, if all other factors remain constant. The findings of this research are consistent with prior work, specifically Silva et al., (2022), where similar effects were observed in alginate coated and uncoated fresh cheese samples [

33]. This reinforces the potential applicability of alginate-based coatings in extending cheese shelf-life.

Figure 5.

The Influence of Various Coatings on pH Levels in Tsalafouti Cheese: A 12-Day Experimental Analysis.

Figure 5.

The Influence of Various Coatings on pH Levels in Tsalafouti Cheese: A 12-Day Experimental Analysis.

3. Conclusions

Apart from the circular economy and environmental benefits, which will be achieved by the development of such food packaging and coatings, a qualitative novel product exhibiting improved mechanical, water/oxygen barrier, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity properties seems to have been developed during this study. The optimum sample ALG/G/15TO@HNT which was indicated as the most promising material could be the target of a next step scaled -up similar process. Results from the preservation of a too sensitive food like “Tsalafouti” Greek soft cheese shown that we prepared a material capable to be applied as edible active packaging or coating to a big variety of foods.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The sodium Alginate powder used was purchased from Acros-Organics (Zeel West Zone 2, Janssen Pharmaceuticalaan 3aB2440 Geel, Belgium). The glycerol used was purchased from Carlo-Erba (Denzlinger Str. 27, 79312 Emmendingen, Germany). Thyme oil was purchased from a local pharmacy market and produced by Chemco (Via Achille Grandi, 13–13/A, 42030 Vezzano sul Crostolo RE, Italy). Halloysite clay nanotubes used was purchased by Sigma-Aldrich (product 685445, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Fifteen fresh pork pancetta with approximate weight 400 g each were provided by a local meat processing plant Aifantis Company within one hour after slaughtering. The media used for microbiological analyses were plate count agar (PCA) and Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA). These media were purchased from VWR International GmbH.

4.2. TO@HNT hybrid nanostructure preparation

The rich in thymol TO@HNT hybrid nanostructure used was prepared according to the methodology described recently based on a novel a green distillation-evaporation/adsorption process [

22,

23]. According to the physicochemical characterization of such TO@HNT nanohybrid with XRD analysis, FTIR spectroscopy, thermogravimetric (TG) analysis, and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements of pure HNT and modified TO@HNT nanohybrid it was showed that physisorption of a mixture rich in TO molecules took place on the external surface of HNT while the calculated average TO content on HNT was 34.5 wt% [

22,

23]. The controlled release process of physiosorbed molecules is easier compared to that of chemisorbed molecules in such EOs–nanoclays hybrids.

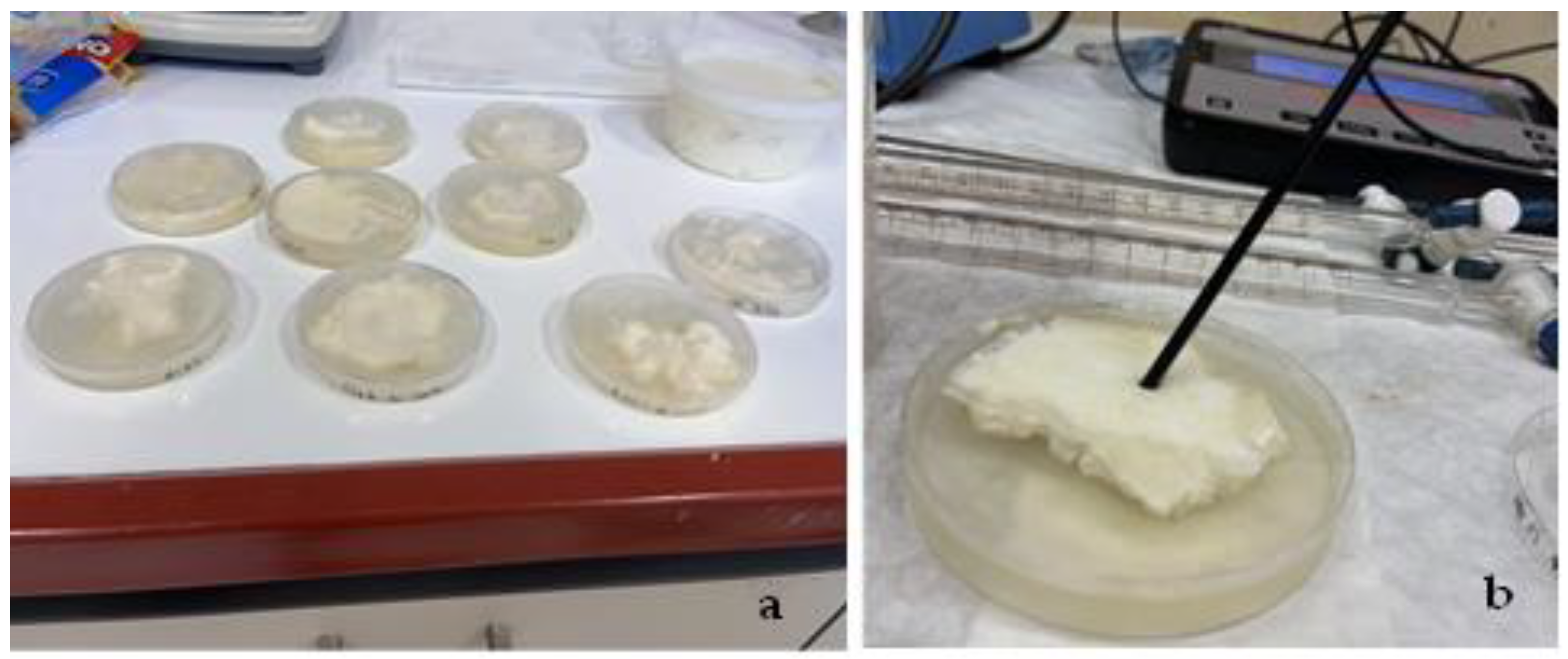

4.3. Preparation of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT active Films

For each film 2 g ALG and 1 g G was spread into 90 mL of distilled water and was heated under continuous stirring since a homogeneous hydrogel was obtained. Simultaneously 0.15, 0.30, and 0.45 g of pure HNT powder or TO@HNT nanohybrid powder was dispersed under vigorous stirring in 10 mL of distilled water using a glass beaker. Then, the homogeneous ALG/G hydrogel was added gradually in the obtained HNT or TO@HNT suspension and vigorously stirred for 2 h. The obtained ALG/G/xHNT (where x=5, 10 and 15) and ALG/G/xTO@HNT (where x=5, 10 and 15) hydrogels were spread in 2 petri dishes (50 mL each) of 11 cm diameter and dried at 25

oC. For comparison pure ALG/G film without the addition of HNT powder or TO@HNT nanohybrid was prepared. The obtained films were pilled of and stored further in a desiccator at 25

oC and 50 %RH (see

Figure 6).

4.4. XRD analysis of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

The obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as well as pure ALG/G film were characterized with XRD analysis by using a Brüker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer instrument (Brüker, Analytical Instruments, S.A., Athens, Greece) and according to the experimental condition described recently [

22].

4.5. FTIR spectroscopy of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

The relaxations of HNT and TO@HNT with ALG/G matrix were investigated with FTIR spectroscopy measuraments. For the measuraments an FT/IR-6000 JASCO Fourier transform spectrometer (JASCO, Interlab, S.A., Athens, Greece) was employed according to the experimental conditions described recently [

22].

4.6. Tensile measuraments of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

Tensile properties of all obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as well as pure ALG/G were carried out according to the ASTM D638 method and the methodology described recently [

22,

35]. For the tensile measurements a Simantzü AX-G 5kNt instrument (Simandzu Asteriadis, S.A., Athens, Greece) was employed.

4.7. Water Vapor Transmission Rate Measurements and Water Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

The Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR g/cm

2.s) for all obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films, as well as pure ALG/G film was measured according to the ASTM E96/E 96M-05 method at 38

οC and 95 %RH by using a handmade apparatus and employing. The calculated WVTR values were transformed to water vapor diffusivity (D

wv) values according to the theory and equations described in detail in previous publications [

24,

36].

4.8. Oxygen Transmission Rate Measurements and Oxygen Permeability Calculation

Oxygen Transmission Rate (OTR) values (cc O

2/m

2/day) for all obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films, as well as pure ALG/G film were measured according to the ASTM D 3985 method at 23

oC and 0% RH. For the measuraments an oxygen permeation analyzer (O.P.A., 8001, Systech Illinois Instruments Co., Johnsburg, IL, USA) was employed. From the measured OTR values the oxygen permeability coefficient values (PeO

2) were calculated according to the theory and equations provided in detail in previous publications [

24,

36].

4.9. Total antioxidant activity of ALG/G/xAC and ALG/G/xTO@AC films

The total antioxidant activity of all ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films was estimated according to the diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) method. For the experiments a 40 ppm ethanolic solution of DPPH stock solution was prepared. Inside a dark glass bottle 10 ml of DPPH stock solution and 300 mg of each film were putted and incubated for 24 hours. The absorbance at 517 nm wavelength of the DPPH solution was measured in the biggening (0 h) and in the end (24 h) of the incubation using a Jasco V-530 UV-vis spectrophotometer. For comparison the absorbance of a 10 mL of ethanolic DPPH solution without the addition of any film was measured at 517 nm and considered as the blank sample.

The % antioxidant activity after 24 h incubation of films was calculated according to the following equation:

4.10. Antibacterial Activity Tests of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films

Acquired from the Institute of Technology of Agricultural Products, ELGO-DEMETER, located in Lykovryssi, Greece, four foodborne pathogenic bacterial strains were utilized to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the films. These strains included Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica (DSMZ 17420) (Gram-negative bacteria), as well as Staphylococcus aureus (DSMZ 12463) and Listeria monocytogenes (DSMZ 27575) (Gram-positive bacteria). The assessment of the films' antimicrobial properties was conducted using the well diffusion method.

The initial step of the experiment involved culturing the bacterial strains in Mueller Hinton Broth at 37°C for 24 hours to promote growth, resulting in a bacterial concentration ranging from 107 to 108 colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU mL-1). Subsequently, to ensure consistent growth of bacterial colonies, the bacterial cultures were evenly spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates with a rotation of the plates at 60-degree intervals.

For testing purposes, 6-mm wells were created on the agar surface of the plates using a cork borer that had been sanitized with alcohol and flamed. These wells were then filled with 100 μl of the test suspensions, which were used to form the final films. Following this step, the plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight.

Following the incubation period, the calipers were utilized to measure the diameters of clear zones surrounding the wells that held the antimicrobial suspensions. This measurement was carried out to assess the level of antimicrobial activity exhibited by the suspensions against the tested bacteria. To ensure the reliability and consistency of the results, the entire experimental procedure was performed in triplicate.

4.11. Application of ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films as active coatings for “tsalafouti” type spreadable cheese shelf - life.

The mesophilic microbial population in coated Tsalafouti soft cheese was assessed using PCA (Plate Count Agar). Microbiological analysis was performed for the total count of mesophilic bacteria. In accordance with the findings of Pala et al. [

37] and Evert et al. [

38] on Ricotta fresh cheese, the microbial analysis on Mesophilic bacteria in Tsalafouti soft cheese validates that such microbial metric serves as a robust indicator of such traditional cheese shelf - life. Briefly, coating materials were first left to dry in sterile petri dishes (both in dish and the lid) at 30 °C for 48 h. Subsequently, 30 g of Tsalafouti cheese was measured and positioned within the Petri dishes, creating a sandwich-like arrangement, aiming to achieve a uniform coating; this was done under sterile conditions (see

Figure 7a). The coated cheese samples were then stored at a consistent temperature of 8°C until the time of assessment. Intermediate samples of Tsalafouti cheese were taken randomly every 3 days for microbiological analysis and for a period of 12 days. For each measurement day, the corresponding petri dish was removed, and 15 g of the cheese was transferred into 90 mL of sterile peptone water. The mixture underwent homogenization for a precise 5-minute duration to obtain a homogeneous blend. Post-homogenization, the blend was transferred to 9 mL tubes for dilution. Subsequently, 0.1 mL of the diluted cheese blend was drawn using a sterile pipette and evenly spread on a PCA agar plate with a sterile cell spreader. These petri dishes were incubated at 35 °C for a 48h duration. After the incubation period, microbial colonies were enumerated, and the colony counts were converted to log10 for analysis. Through this process, the microbial population in coated Tsalafouti soft cheese samples was thoroughly evaluated, providing insights into the efficacy of the coatings for microbial control. For comparison the pH of all coated and uncoated samples was monitored every 3 days during the preservation period of 12 days (see

Figure 7b).

4.12. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the microbial tests data corroborates the findings as being statistically significant at a 5% level (p≤0.05), with a test statistic F equaling 2.683385 and a p-value of 0.0260449. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected. Furthermore, the large observed effect size (0.89) indicates substantial and meaningful differences not attributable to random chance, while the η2 of 0.44 signifies that the group accounts for 44.3% of the variance from the average. This empirical evidence underscores the potential utility of various coatings in the effective control of bacterial proliferation, thereby enhancing the microbial quality of Tsalafouti cheese and potentially other cheese varieties.

Moreover, statistical analysis was performed on mechanical properties, water/oxygen barrier, and antioxidant activity data, using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) through SPSS software. The Tukey HSD test was employed to evaluate the significance of mean values. Significance was set at the 5% level (p≤0.05) to determine statistically relevant differences. All data are presented as mean value ± standard deviation (SD). The measurements were conducted in at least three replications for consistency and reliability.

Author Contributions

Synthesis experiment design, A.E.G., C.P. and C.E.S.; paper writing, A.E.G., E.K., K.Z., E.R., and C.E.S.; overall evaluation of this work, A.E.G. and C.E.S.; experimental data analysis and interpretation, A.E.G., C.E.S. and C.P.; XRD, FTIR, tensile measurements, antioxidant activity, WVTR, and OTR, experimental measurements, and fresh bananas packaging test, A.E.G., A.L., K.Z., S.G., V.K.K, G.K., and C.E.S.; tsalafouti soft cheese preservation test E.K., A.K., L.A., K.Z. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was no funded.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hamam, M.; Chinnici, G.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Pecorino, B.; Maesano, G.; D’Amico, M. Circular Economy Models in Agro-Food Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Strenger, M.; Maier-Nöth, A.; Schmid, M. Food Packaging and Sustainability – Consumer Perception vs. Correlated Scientific Facts: A Review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 298, 126733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.A.M. Sustainable (Food) Packaging – an Overview. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 2014, 31, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahari, H.; Soufiani, S.P. Smart and Active Food Packaging: Insights in Novel Food Packaging. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Md.W.; Haque, Md.A.; Mohibbullah, Md.; Khan, Md.S.I.; Islam, M.A.; Mondal, Md.H.T.; Ahmmed, R. A Review on Active Packaging for Quality and Safety of Foods: Current Trends, Applications, Prospects and Challenges. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Ji, N.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Bioactive and Intelligent Starch-Based Films: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 116, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Morsi, R.E.; Kerch, G.; Elsabee, M.Z.; Kaya, M.; Labidi, J.; Khawar, K.M. Current Advancements in Chitosan-Based Film Production for Food Technology; A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 121, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; Du, W.-X.; de Avena-Bustillos, R. J.; de Soares, N. F.F.; McHugh, T.H. Edible Films from Pectin: Physical-Mechanical and Antimicrobial Properties - A Review. Food Hydrocolloids 2014, 35, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.S.; Sarbon, N.M. Physical and Mechanical Characteristics of Gelatin-Based Films as a Potential Food Packaging Material: A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontominas, M.G. Use of Alginates as Food Packaging Materials. Foods 2020, 9, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk Parreidt, T.; Müller, K.; Schmid, M. Alginate-Based Edible Films and Coatings for Food Packaging Applications. Foods 2018, 7, E170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, I.D.; Rehman, Z.U.; Moradali, M.F.; Wang, Y.; Rehm, B.H.A. Microbial Alginate Production, Modification and Its Applications. Microbial Biotechnology 2013, 6, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpena, M.; Nuñez-Estevez, B.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A. Essential Oils and Their Application on Active Packaging Systems: A Review. Resources 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Barkauskaite, S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Essential Oils as Additives in Active Food Packaging. Food Chemistry 2021, 343, 128403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Martínez, A.; López-Gómez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Potential of Essential Oils from Active Packaging to Highly Reduce Ethylene Biosynthesis in Broccoli and Apples. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh, D.; Majdoub, H.; Darder, M. An Overview of Clay-Polymer Nanocomposites Containing Bioactive Compounds for Food Packaging Applications. Applied Clay Science 2022, 216, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ren, T.; Perkins, P.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Applications of Halloysite Nanotubes in Food Packaging for Improving Film Performance and Food Preservation. Food Control 2021, 124, 107876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sothornvit, R. Nanostructured Materials for Food Packaging Systems: New Functional Properties. Current Opinion in Food Science 2019, 25, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malissiova, E.; Meleti, E.; Samara, A.; Alexandraki, M.; Manouras, A. The Traditional Greek Cheese Tsalafouti: History, Technology, Nutrition and Gastronomy. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2023, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukis, C.; Voidarou, C.; Demertzis, P. G.; Akrida, K. Demertzi Effect of The Composition of Grazing Matter on The Quality Characteristics of The Traditional Greek Dairy Product “Tsalafouti”. Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology 2017, 11, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa, E.C.; Kondyli, E.; Malamou, E.; Kakouri, A.; Vlachou, A.-M.; Samelis, J. Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Characteristics of ‘Tsalafouti’ traditionalGreek Dairy Product. Food Res. 2022, 6, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinos E. Salmas; Aris E. Giannakas; Dimitrios Moschovas; Eleni Kollia; Stsvros Georgopoulos; Christina Gioti; Areti Leontiou; Apostolos Avgeropoulos; Anna Kopsacheili; Learda Avdulai; et al. Kiwi Fruits Preservation Using Novel Edible Active Coatings Based on Rich in Thymol Halloysite Nanostructures and Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Gels. Gels Bioactive Gel Films and Coatings Applied in Active Food Packaging.

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Moschovas, D.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karabagias, I.K.; Baikousi, M.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Katerinopoulou, K.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; et al. Development, Characterization, and Evaluation as Food Active Packaging of Low-Density-Polyethylene-Based Films Incorporated with Rich in Thymol Halloysite Nanohybrid for Fresh “Scaloppini” Type Pork Meat Fillets Preservation. Polymers 2023, 15, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Moschovas, D.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Georgopoulos, S.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Aktypis, A.; Proestos, C.; Karakassides, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. The Increase of Soft Cheese Shelf-Life Packaged with Edible Films Based on Novel Hybrid Nanostructures. Gels 2022, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoradosoa, T.A.; Ali, G.; Delattre, C.; Laroche, C.; Petit, E.; Wadouachi, A.; Michaud, P. Extraction and Characterization of an Alginate from the Brown Seaweed Sargassum Turbinarioides Grunow. J Appl Phycol 2010, 22, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barot, T.; Rawtani, D.; Kulkarni, P. Physicochemical and Biological Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Immobilized Halloysite Nanotubes-Based Resin Composite for Dental Applications. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Functionalization of Halloysite Clay Nanotubes by Grafting with γ-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane | The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jp805657t (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Xie, D.F.; Martino, V.P.; Sangwan, P.; Way, C.; Cash, G.A.; Pollet, E.; Dean, K.M.; Halley, P.J.; Avérous, L. Elaboration and Properties of Plasticised Chitosan-Based Exfoliated Nano-Biocomposites. Polymer 2013, 54, 3654–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.; Grigoriadi, K.; Leontiou, A.; Barkoula, N.-M.; Ladavos, A. Preparation, Characterization, Mechanical and Barrier Properties Investigation of Chitosan–Clay Nanocomposites. Carbohydrate Polymers 2014, 108, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymers | Free Full-Text | Current Trends in the Utilization of Essential Oils for Polysaccharide- and Protein-Derived Food Packaging Materials. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/6/1146 (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Leontiou, A.; Baikousi, M.; Moschovas, D.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Avgeropoulos, A. Synthesis of a Novel Chitosan/Basil Oil Blend and Development of Novel Low Density Poly Ethylene/Chitosan/Basil Oil Active Packaging Films Following a Melt-Extrusion Process for Enhancing Chicken Breast Fillets Shelf-Life. Molecules 2021, 26, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Baikousi, M.; Leontiou, A.; Siasou, Z.; Karakassides, M.A. Development of Poly(L-Lactic Acid)/Chitosan/Basil Oil Active Packaging Films via a Melt-Extrusion Process Using Novel Chitosan/Basil Oil Blends. Processes 2021, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.P.M.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Silva, C.C.G. Application of an Alginate-Based Edible Coating with Bacteriocin-Producing Lactococcus Strains in Fresh Cheese Preservation. LWT 2022, 153, 112486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saegeman, V.S.M.; Ectors, N.L.; Lismont, D.; Verduyckt, B.; Verhaegen, J. Short- and Long-Term Bacterial Inhibiting Effect of High Concentrations of Glycerol Used in the Preservation of Skin Allografts. Burns 2008, 34, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Moschovas, D.; Karabagias, I.K.; Gioti, C.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Kehayias, G.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Novel-Thymol@Natural-Zeolite/Low-Density-Polyethylene Active Packaging Film: Applications for Pork Fillets Preservation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Baikousi, M.; Kollia, E.; Tsigkou, V.; Proestos, C. Effect of Copper and Titanium-Exchanged Montmorillonite Nanostructures on the Packaging Performance of Chitosan/Poly-Vinyl-Alcohol-Based Active Packaging Nanocomposite Films. Foods 2021, 10, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, C.; Scarano, C.; Venusti, M.; Sardo, D.; Casti, D.; Cossu, F.; Lamon, S.; Spanu, V.; Ibba, M.; Marras, M.; et al. Shelf Life Evaluation of Ricotta Fresca Sheep Cheese in Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Ital J Food Saf 2016, 5, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evert-Arriagada, K.; Hernández-Herrero, M.M.; Juan, B.; Guamis, B.; Trujillo, A.J. Effect of High Pressure on Fresh Cheese Shelf-Life. Journal of Food Engineering 2012, 110, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

XRD plots of pure HNT (black line) and modified TO@HNT nanohyberid (red line) as well as for pure ALG/G film (line (1)), ALG/G/5HNT film (line (2)), ALG/G/10HNT film (line (3)), ALG/G/15HNT film (line (4)), ALG/G/5TO@HNT film (lines (54)), ALG/G/10TO@HNT film (lines (6)), and ALG/G/15TO@HNT film (lines (7)).

Figure 1.

XRD plots of pure HNT (black line) and modified TO@HNT nanohyberid (red line) as well as for pure ALG/G film (line (1)), ALG/G/5HNT film (line (2)), ALG/G/10HNT film (line (3)), ALG/G/15HNT film (line (4)), ALG/G/5TO@HNT film (lines (54)), ALG/G/10TO@HNT film (lines (6)), and ALG/G/15TO@HNT film (lines (7)).

Figure 2.

FTIR plots of (1) ALG/G, (2) ALG/G/5HNT (3) ALG/G/10HNT, (4) ALG/G /15HNT, (5) ALG/G /5TO@HNT, (6) ALG/G/10TO@HNT, and (7) ALG/G /15TO@HNT obtained films.

Figure 2.

FTIR plots of (1) ALG/G, (2) ALG/G/5HNT (3) ALG/G/10HNT, (4) ALG/G /15HNT, (5) ALG/G /5TO@HNT, (6) ALG/G/10TO@HNT, and (7) ALG/G /15TO@HNT obtained films.

Figure 3.

Calculated DPPH total antioxidant activity values of films.

Figure 3.

Calculated DPPH total antioxidant activity values of films.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Microbial Growth in Tsalafouti Cheese with Coatings Over 12 Days.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Microbial Growth in Tsalafouti Cheese with Coatings Over 12 Days.

Figure 6.

photo images (1) pure CS/PVOH films, (2) CS/PVOH/5HNT, (3) CS/PVOH/10HNT, (4) CS/PVOH/15HNT, (5) CS/PVOH/5TO@HNT, (6) CS/PVOH/10TO@HNT, and (7) CS/PVOH/5TO@HNT films.

Figure 6.

photo images (1) pure CS/PVOH films, (2) CS/PVOH/5HNT, (3) CS/PVOH/10HNT, (4) CS/PVOH/15HNT, (5) CS/PVOH/5TO@HNT, (6) CS/PVOH/10TO@HNT, and (7) CS/PVOH/5TO@HNT films.

Figure 7.

(a) “Tsalafouti” spread cheese uncoated and coated with two disc shape films of all obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT as well as ALG/G films inside plastic petri dishes, (b) pH measurement of “tsalafouti” coated samples during the preservation period of 12 days.

Figure 7.

(a) “Tsalafouti” spread cheese uncoated and coated with two disc shape films of all obtained ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT as well as ALG/G films inside plastic petri dishes, (b) pH measurement of “tsalafouti” coated samples during the preservation period of 12 days.

Table 1.

Calculated values of Young’s (E) Modulus, ultimate tensile strength (uts) and % strain at break ("b).

Table 1.

Calculated values of Young’s (E) Modulus, ultimate tensile strength (uts) and % strain at break ("b).

| Sample code name |

E-Elastic Modulus (MPa) |

σuts (MPa) |

%ε |

| ALG/G |

445.5(63.8) |

15.2(2.4) |

40.2(4.7) |

| ALG/G/5HNT |

25.4(6.6) |

2.4(0.7) |

86.9(11.4) |

| ALG/G/10HNT |

617.7(20.3) |

21.8(1.9) |

32.6(5.8) |

| ALG/G/15HNT |

621.3(59.5) |

16.9(3.5) |

18.4(6.7) |

| ALG/G/5TO@HNT |

480.9(20.1) |

16.5(0.9) |

46.5(6.4) |

| ALG/G/10TO@HNT |

607.3(53.4) |

19.2(1.6) |

36.8(4.1) |

| ALG/G/15TO@HNT |

628.9(66.6) |

18.5(1.1) |

33.4(3.9) |

Table 2.

Film thickness, water vapor transmission rate (WVTR), water diffusivity (D), oxygen transmission rate (OTR), and oxygen diffusivity (PeO2) values of pure ALG/G film as well as all ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films.

Table 2.

Film thickness, water vapor transmission rate (WVTR), water diffusivity (D), oxygen transmission rate (OTR), and oxygen diffusivity (PeO2) values of pure ALG/G film as well as all ALG/G/xHNT and ALG/G/xTO@HNT films.

| Sample code name |

Film thickness (mm) |

Water Vapor Transmission Rate.10-6 (g/cm2.day) |

Water Vapor Diffusion Coefficient Dwv (10-4 cm2/s) |

Film thickness (mm) |

Oxygen Transmission Rate (ml/m2.day) |

Oxygen permeability PeO2 10-6(cm2.s-1) |

| ALG/G |

0.15±0.01 |

2.46±0.12 |

8.69±0.11 |

0.15±0.01 |

196459±185 |

3.41±0.31 |

| ALG/G/5HNT |

0.16±0.01 |

2.57±0.10 |

9.69±0.09 |

0.22±0.01 |

134254±124 |

3.38±0.32 |

| ALG/G/10HNT |

0.17±0.01 |

2.09±0.13 |

8.39±0.12 |

0.17±0.01 |

82374±84 |

1.60±0.16 |

| ALG/G/15HNT |

0.16±0.01 |

2.14±0.09 |

8.07±0.08 |

0.13±0.01 |

192154±186 |

2.95±0.28 |

| ALG/G/5TO@HNT |

0.15±0.01 |

2.17±0.07 |

7.67±0.06 |

0.15±0.01 |

125335±112 |

2.14±0.19 |

| ALG/G/10TO@HNT |

0.14±0.01 |

2.16±0.07 |

7.13±0.05 |

0.33±0.01 |

34984±54 |

1.33±0.21 |

| ALG/G/15TO@HNT |

0.14±0.01 |

2.16±0.05 |

7.11±0.04 |

0.20±0.01 |

124256±123 |

2.91±0.29 |

Table 3.

pH Values of Tsalafouti Soft Cheese During Storage at 8°C for 12 Days after application of different coatings.

Table 3.

pH Values of Tsalafouti Soft Cheese During Storage at 8°C for 12 Days after application of different coatings.

| Coating Type |

Day 0 |

Day 3 |

Day 6 |

Day 9 |

Day 12 |

| Uncoated |

4.59 ± 0.10 |

4.544 ± 0.12 |

4.453 ± 0.11 |

4.409 ± 0.13 |

4.315 ± 0.15 |

| ALG/G |

4.59 ± 0.05 |

4.550 ± 0.09 |

4.504 ± 0.07 |

4.465 ± 0.08 |

4.383 ± 0.10 |

| ALG/G/5HNT |

4.59 ± 0.12 |

4.578 ± 0.14 |

4.542 ± 0.13 |

4.492 ± 0.12 |

4.443 ± 0.11 |

| ALG/G/10HNT |

4.59 ± 0.07 |

4.579 ± 0.05 |

4.541 ± 0.09 |

4.531 ± 0.10 |

4.448 ± 0.08 |

| ALG/G/15HNT |

4.59 ± 0.15 |

4.581 ± 0.11 |

4.553 ± 0.10 |

4.542 ± 0.12 |

4.461 ± 0.14 |

| ALG/G/5TO@HNT |

4.59 ± 0.11 |

4.579 ± 0.13 |

4.533 ± 0.08 |

4.521 ± 0.09 |

4.453 ± 0.07 |

| ALG/G/10TO@HNT |

4.59 ± 0.13 |

4.583 ± 0.07 |

4.571 ± 0.15 |

4.531 ± 0.11 |

4.457 ± 0.09 |

| ALG/G/15TO@HNT |

4.59 ± 0.09 |

4.584 ± 0.08 |

4.575 ± 0.05 |

4.532 ± 0.14 |

4.471 ± 0.10 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).