1. Introduction

For over thirty years, cosmologists have built up conclusive evidence that cosmic expansion is accelerating. To explain such observation, we need to assume that there is a mysterious new component: Dark Energy (DE) or a Cosmological Constant,

. This new term is usually interpreted as a repulsive force between galaxies that opposes gravity and dominates the expansion. Such strange behaviour is often flagged as one of the most important challenges to understand the laws of Physics today and could provide an observational window to understand Quantum Gravity ([

1]).

Usually, cosmic acceleration is defined by the adimensional coefficient

, where

. For a universe with an equation of state

this results in

. For regular matter or radiation we have

so we expect the expansion to decelerate (

) because of gravity. However, concordant measurements from galaxy clustering (e.g. [

2,

3,

4]), Type Ia supernova ([

5,

6]) and CMB ([

7,

8]) all agree with an expansion that tends asymptotically to

or

(e.g. see [

9] and references therein for a review of more recent results, including weak gravitational lensing). This behaviour is very consistent with a Cosmological Constant

(see [

10,

11,

12]) where

tends to

and

q tends to

. What does this all mean?

The term Dark Energy (DE) was introduced by [

13] to refer for any component with

. However, there is no fundamental understanding of what DE is or why we measure a term with

. A natural candidate for DE is

, which is equivalent to

and can also be thought of as the ground state of a field (the DE), similar to the Inflaton but with a much smaller (

) energy scale.

can also be a fundamental constant in GR, but this has some other complications ([

10,

11,

12]).

2. Cosmic Acceleration

Current observations of the cosmos seem consistent with General Relativity (GR) with a flat FLRW (Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker) metric in comoving coordinates, corresponding to a homogeneous and isotropic space :

where we use units of

and

is the scale factor. For a classical perfect fluid with matter and radiation density

, the solution to Einstein’s field equations (called LCDM) is well known:

where

, where

and

represents the current (

) matter and radiation density,

and

. The cosmological constant (

) term corresponds to

where

Km/s/Mpc. Given

and

we can use the above equations to find

.

Cosmic acceleration is usually defined as

, where the dot represents a derivative with respect to proper time

. A derivative over Eq.

2 shows that:

For

Eq.

2-

3 indicate that as time passes (

) we have that

and

. This is because gravity opposes cosmic expansion and brings the expansion asymptotically to a halt. Including

brings the expansion to accelerate so that

and

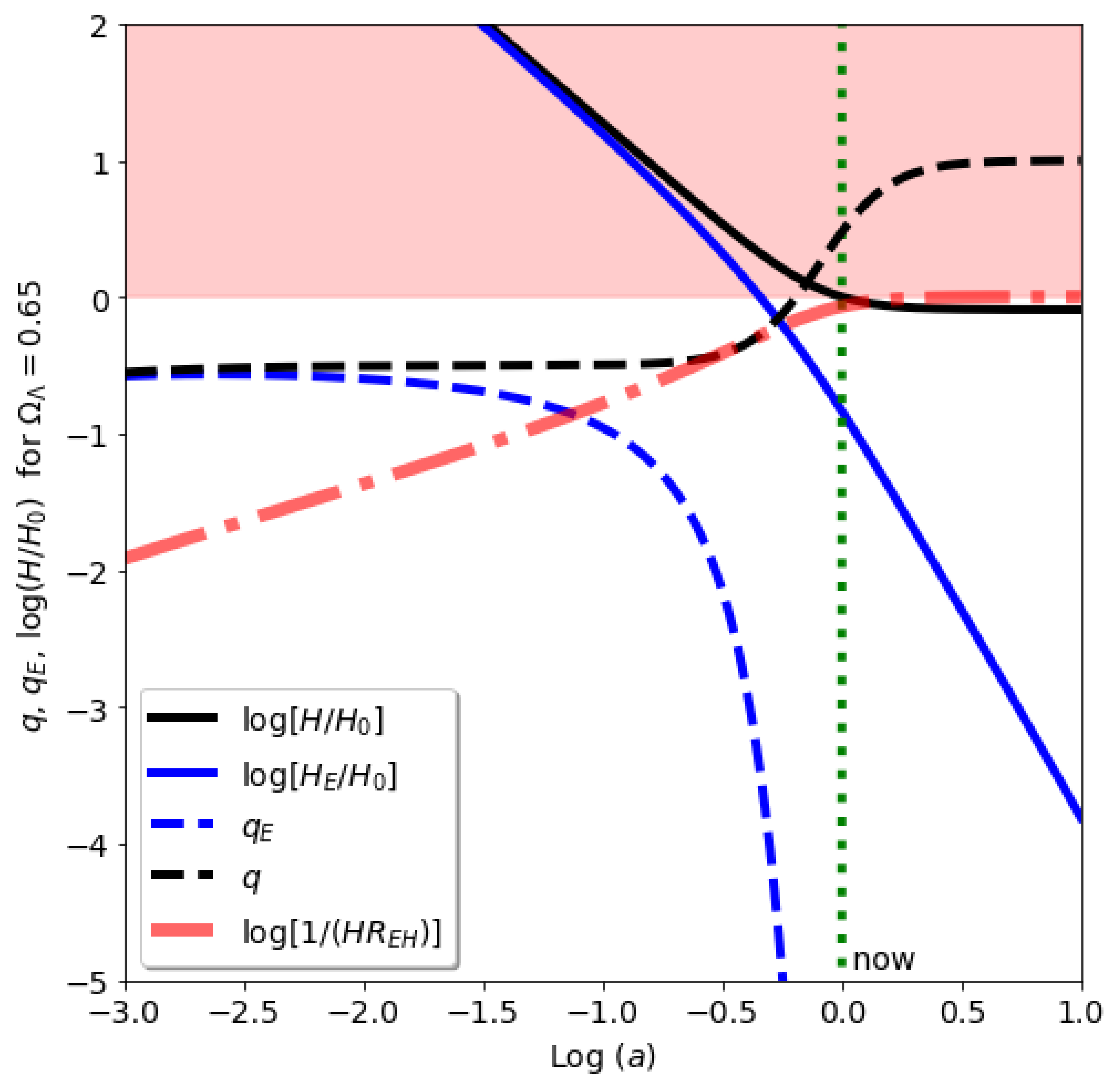

. This is illustrated as black lines in

Figure 1 for

. The effect of

is then interpreted as a mysterious new repulsive force (or Dark Energy) that opposes gravity.

But this interpretation of acceleration, based on

, corresponds to the acceleration of 3D space-like events,

, of fixed comoving separation

:

so that

and

. Such events are not causally connected and correspond to a non-local theory of Gravity or to the Newtonian approximation of action at a distance where the speed of light is infinite. We need a better definition of acceleration to identify the nature of its physical causes within GR.

3. Event Acceleration

To have a coordinate invariant measurement of cosmic acceleration we need to use the distance between the events that are causally connected. We introduce here the event expansion rate and acceleration to have an invariant measurement and to better interpret the effects of in the cosmic expansion and therefore its possible mysterious meaning.

A photon emitted at time

can travel following an outgoing radial null geodesic

which from Eq.

1 implies

. The proper distance

traveled between the event at

and the future event at

is then (see e.g. [

14]):

Thus, we argue that we should use

R instead of

d in Eq.

4 as a measure of distance in cosmology to define cosmic acceleration and expansion rate. Such change is equivalent to a simple change of coordinates in the FLRW metric of Eq.

1, from comoving coordinates

to physical coordinates

:

We then have that

(where, as before, the dot is a derivative with respect to

) and we can define the expansion rate between events as:

where the additional term,

corresponds to a friction term. There is an ambiguity in this definition because

R in Eq.

5 depends also on the arbitrary time

use to define

R. To break this ambiguity we will fix here

R to be the distance to

(which corresponds to a possible Event Horizon):

where

. As we will see in next section, this choice implies that

is zero unless

. So this new invariant way to define cosmic expansion and acceleration reproduces the standard one when

. But for

we have that the event expansion halts

(blue line in in

Figure 1) due to the friction term (red line) for

, while the standard Hubble rate definition approaches a constant

(black line). This might seem irrelevant at first look, but the physical interpretation is quite different. In the standard definition the expansion becomes asymptotically exponential (de-Sitter or inflationary expansion) while in our new definition it becomes static!

The event acceleration can then be measured as:

As before, for

the friction term,

, makes little difference between

q and

. For

the friction term asymptotically cancels the

term in

(i.e. Eq.

3) so that

is always negative, no matter how large is

(

and

). The net effect of the

term is to bring the expansion of events to a faster stop (

) that in the case with gravity alone. This is illustrated in

Figure 1. The

term produces a faster deceleration (than with gravity alone). This corresponds to an attracting (and not repulsive) force, as explained in more detail in the Appendix.

4. Event Horizon

But what is more relevant to understand the meaning of

is that the additional deceleration brings the expansion to a halt within a finite proper distance between the events, creating an Event Horizon (EH). This is the maximum distance that a photon emitted at time

can travel following the outgoing radial null geodesic:

where

. For

we have

, so there is no EH. But for

we have that

(red line in

Figure 1). We can then see that

corresponds to a causal horizon or boundary term. The analog force behaves like a rubber band between observed galaxies (events) that prevents them crossing some maximum stretch (i.e. the EH). We can interpret such force as a boundary term that just emerges from the finite speed of light (see the Appendix).

The FLRW metric with

, asymptotically tends to the de-Sitter metric, which can be written as:

This form corresponds to a static 4D hyper-sphere of radius

. So in this (rest) frame, events can only travel a finite distance

within a static 3D surface of the imaginary 4D hyper-sphere. Thus there is a frame duality that allows us to equivalently describe de-Sitter space as either static (in proper or physical coordinates

and

t) or exponentially expanding (in comoving coordinates

and

).

This frame duality can be understood as a Lorentz contraction

, where

. An observer in the rest frame, sees the moving fluid element

contracted by the Lorentz factor

. Therefore, the FLRW metric becomes de-Sitter:

This radial element corresponds to the metric of a hypersphere of radius

that expands towards a constant event horizon

(see also [

15] and the Appendix in [

16]). This duality is better understand using our new measures for the expansion rate

and cosmic deceleration

based on the distance between causal events.

5. Comparison to Data

We show next how to estimate the new measure of cosmic acceleration,

, using direct astrophysical observations. As an example consider the Supernovae Ia (SNIa) data as given by the ’Pantheon Sample’ compilation ([

17]) consisting on 1048 SNIas between

. Each SNIa provides a direct estimate of the luminosity distance

at a given measured redshift

z. This corresponds to comoving look-back distance:

so that

gives us directly

, where the prime is a derivative respect to

z. The second derivative gives us the acceleration:

is given by the model prediction in Eq.

10 (arbitrarily fixed at

in both data and models). We adopt here the approach presented in [

18], who used an empirical fit to the luminosity distance measurements, based on a third-order logarithmic polynomial:

where

. [

18] find a good fit to:

and

to the full SNIa ’Pantheon Sample’. We use these values of

A and

B and its corresponding errors to estimate

H,

q and

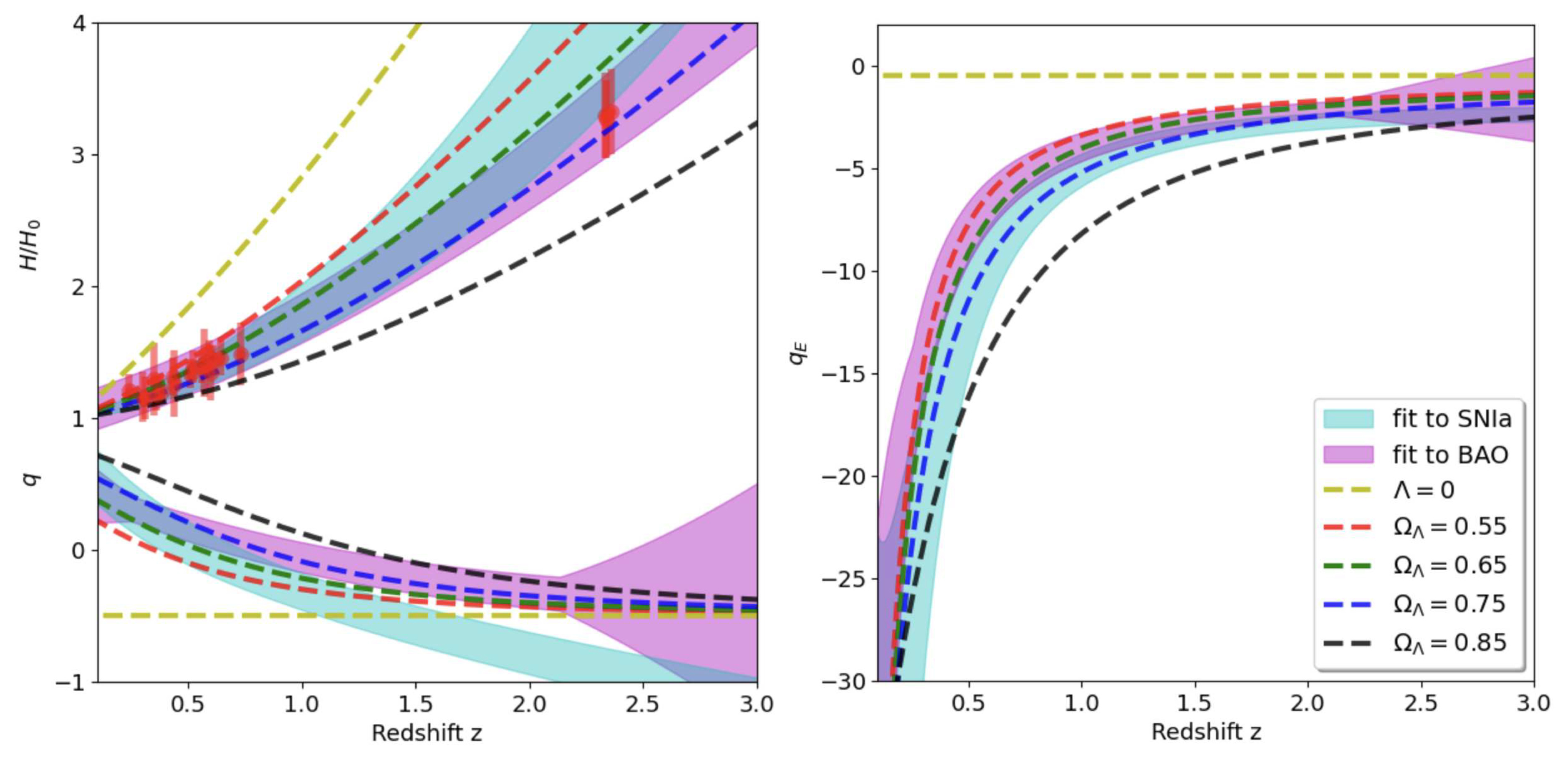

using the above relations. Results for

H and

q are shown as shaded cyan regions in the left panel

Figure 2. They are compared to the LCDM predictions in Eq.

2 and

3.

There is a very good agreement in

for

. At

, the

estimates are also consistent with the

predictions. But the detailed

evolution with redshift does not seem to follow any of the model predictions, specially for

. The

estimates are too steep compare to the different models predictions. If we compare instead the

estimates (see right panel of

Figure 2) we find a much better agreement with the model predictions. This seems to validate our

approach, but it is not clear from this comparison alone if this is caused by the fitting function use in Eq.

15.

To test this further we use measurements of the radial BAO data to estimate

. Such measurements give us a direct estimate of

(as first demonstrated by [

19,

20]) so they have the advantage over SNIa that we only need to do a first order derivative, to estimate

q or

:

As an illustration we use

measurements presented in Table 2 in [

21]. This compilation of

is shown as red points with

errorbars in the left panel

Figure 2. The compilation include values from the clustering of galaxies (

) and Ly-alpha forest in QSO (

). The combination of two separated redshift ranges allows for a very good measurement of

at the intermediate redshift (

), where we found (see above) the discrepancies in SNIa for

q and

model comparison. This provides a very good contraint on cosmic acceleration, indenpend of possible calibration errors in

or sampling errors. This is something that we can not yet do with the current SNIa data, but will be very interesting to see in the near future with upcoming data. We fit a quadratic polynomial to the radial BAO data:

We have checked that the results presented here are very similar if we use a cubic polynomial. We find

,

and

(in units of Km/s/Mpc) with strong covariance between the errors (the cross-correlation coefficient between

and

is

). The value of

is in good agreement with the Planck CMB fit ([

8]) but in some tension with the SNIa local calibration:

(see [

22]). This corresponds to either a local calibration problem (in SNIa, in radial BAO or in both) or a tension in the

CDM model at different times or distances (see e.g. [

23]). We ignore this normalization problem here and just focus on the evolution

to measure cosmic acceleration

q or

(which are fairly independent of

).

In the right panel of

Figure 2 we show (as shaded regions) the measurements for

given by combining Eq.

15 and Eq.

17 with Eq.

16. The measurements clearly favour models with large negative cosmic event acceleration

, which supports our interpretation of

as a friction term.

Comparing left and right panels in

Figure 2 we see that both

q and

are rougthly consistent with models with

( or

) in good concordance with

in the upper left panel of

Figure 2.

Even when the underlying model for

q and

is the same, note how the measured

q and

data have different tensions with the model predictions as a function of redshift. In particular, the radial BAO and SNIa data sets show inconsistencies among them for

q around

. This is a well known tension (see e.g. Fig.17 in [

24]). This tension disappears when we use the corresponding estimates for

. Data is more consistent with the

estimation.

One would expect that a perfect realizations of the LCDM model in Eq.

2 would produce consistent results in both

q and

. But deviations from LCDM and systematic effects can produce tensions in data, specially if we use a parametrization, like

q, which refers to events we never observe. The

q and

parametrization of acceleration are more general than the particular LCDM model and the fact that data prefers

is an important indication. Data lives in the light-cone, which corresponds to

rather than

q. At

the difference between a light-cone and space-like separations is very significant and any discrepancies in the data or model will show more pronounced in the

q modeling.

We conclude that the data shows some tensions with LCDM predictions (as indicated by q) but confirms that cosmic expansion is clearly decelerating (as indicated by ) so that events are trapped inside an Event Horizon ().

6. Discussion & Conclusion

We have shown here that the measured

term, which is usually interpreted as causing cosmic acceleration (see §

Section 2), results in a faster cosmic deceleration of events (than that caused by gravity alone, see §

Section 3). This explains the origin of the Event Horizon (EH, see §

Section 4) that results from an expansion dominated by

. It points in the direction that

is not a new form of vacuum energy ([

10,

11,

12]) but a boundary or surface term in the field equations.

The EH measured in our cosmic expansion behaves like the interior of a Schwarzschild Black Hole (BH) and is identical to it if we assume that the space outside

is approximately empty (see [

16]). We can also conjecture from this, that the interior dynamics of the Schwarzschild BH radius,

, could also have a similar

surface term

, as part of its field equations, at least for expanding interior BH solutions. The

term becomes the actual mechanism that prevents anything from escaping the BH interior (see [

25]).

The Event Horizon

measured with

(i.e. Eq.

10, which is equivalent to the presence of

) also tell us that there is a finite mass

trapped within

. If we assume that the space outside

is approximately empty, such

provides is in fact the explanation for the observed

and therefore for

:

, as in the Schwarzschild BH (see [

26]).

That is fixed by the total mass of our universe is in good agreement with the physical interpretation presented here that corresponds to a friction (attractive) force that decelerates cosmic events. In the Appendix we elaborate in this idea and revisit the Newtonian limit to show that corresponds to an additional (attractive) Hooke’s term to the inverse square gravitational law.