To evaluate the performance of the four probability distributions of the interevent time presented in

Section 2 we examine two sequences of earthquakes related to two strong seismic crises that occurred in central Italy in the last decades: the L’Aquila (

) earthquake in 2009 and the Amatrice (

) - Norcia (

) earthquakes in 2016. These earthquakes have been associated with two composite seismogenic sources of the Database of Individual Seismogenic Sources (DISS, version 3.2.1) [

18] that can have the potential for earthquakes of up to

. Both the data sequences analyzed in this study are drawn from the Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (

Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia; INGV) web services: Italian Seismological Instrumental and Parametric Database (ISIDe) working group (2016), version 1.0, accessible at

http://cnt.rm.ingv.it/en/iside [

19], in which the size of the events is expressed in different units of magnitude, as local magnitude

, duration magnitude

, and moment magnitude

. We have therefore applied the orthogonal regression relationships:

and

[

20] to convert

and

to

so as to construct homogenous data sets. The spatial extension of the areas under examination is established by taking into account the empirical relationship between magnitude and rupture length

-

- by Wells and Coppersmith [

21].

4.1. L’Aquila Sequence

On April 6, 2009 (01:13:40 UTC), a

shock was recorded with epicenter at latitude 42.342, longitude 13.380 near L’Aquila, the capital of the Abruzzo region in central Italy. Consistently with the criteria set out above we choose the rectangular area centered on the epicenter, of latitude size (41.8, 43.0) degrees and longitude size (12.8, 13.8) degrees as study area, and we analyze the temporal period from April 7, 2005 to the end of July 2009 taking

as the magnitude threshold in order to guarantee the completeness of the data set with the exception of, at most, a few hours after the main shock when temporary partial incompleteness can be observed due to the well-known difficulty in recording all of the events at the beginning of the aftershock sequence, and especially those of low magnitude [

22]. The main shock was preceded by a

foreshock on March 30, 2009 [

23], and was followed by an aftershock sequence which lasted more than a year, the strongest of which of

occurred on April 7, 2009 [

24].

Overall we have 2725 events, that is

interevent times through which we construct

temporal windows, each of 100 consecutive observations, shifting at each new event. To observe how the temporal distribution changes we fit the four probability models (

Section 2) to the data set associated with each time window, and then compare the pairwise differences of their posterior marginal log-likelihoods with the value

of the Jeffreys scale that indicates strong evidence in favor of the first model. In the case of the exponential probability density:

, we adopt the conjugate Gamma(2,1) distribution as prior distribution of the

parameter so that the expected seismic rate is about 2 (time in days). For the other three probability models under examination

Table 1 reports the parameters of the prior distributions and the

coefficients used in the proposal distributions of the MH algorithm to obtain suitable acceptance rates.

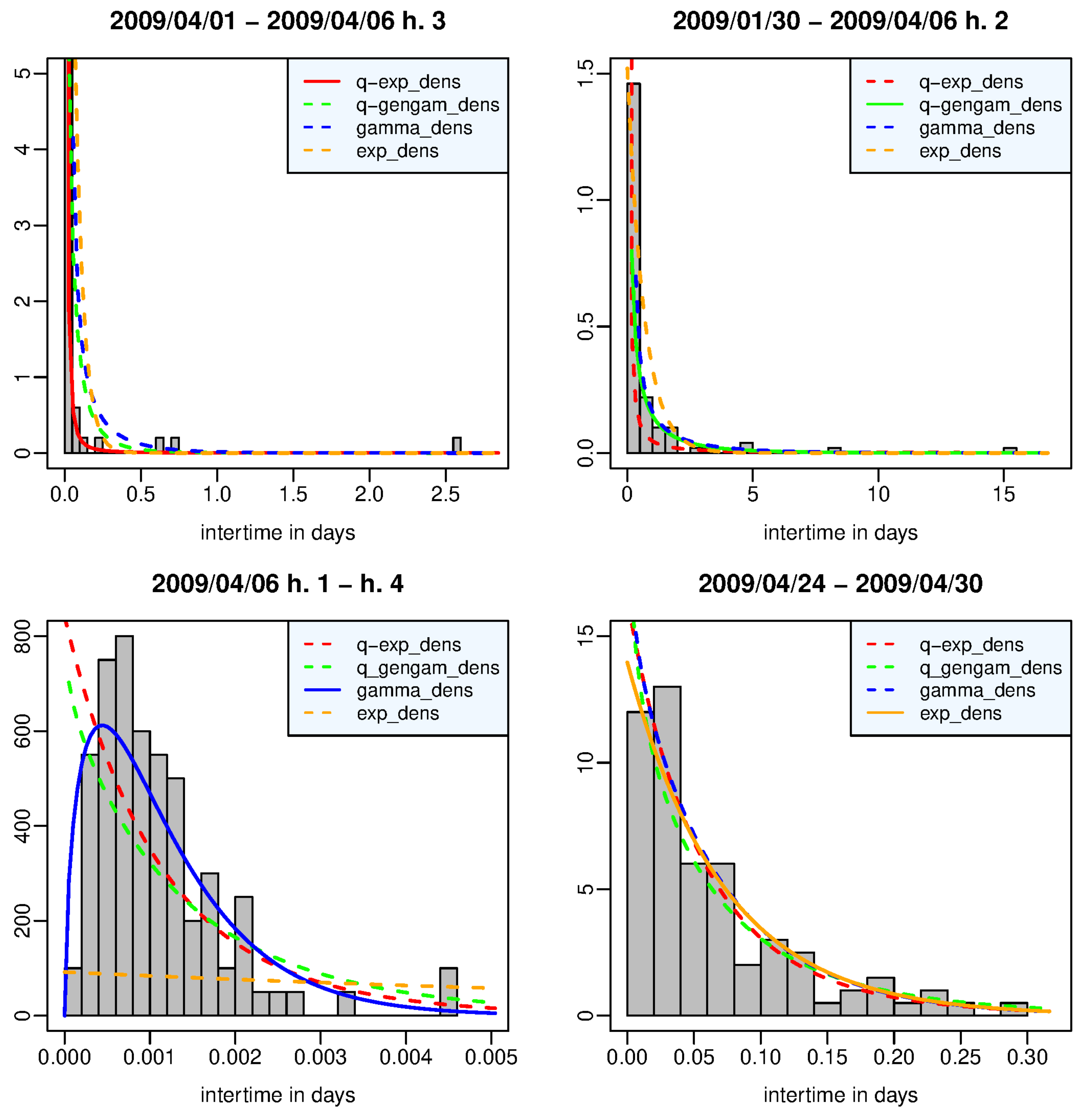

Figure 1 shows the estimated density functions and the histogram of the interevent times belonging to the time window in which each density function, represented by a solid line, provides respectively the best fit to the data; in particular, a) the window in the left top panel refers to the events that occurred from April 1, 2009 up to two hours after the main shock, 90% of which are aftershocks; the

q-exponential density function has both its largest posterior marginal likelihood and the maximum difference from the second best density function (

q-generalized gamma); b) right top panel: the window contains the events from January 30, 2009 to 1 hour after the main shock; the

q-generalized gamma density function is the best model but it is worth no more than a mere mention for the evidence shown by its fit to the data with respect to the second best density (gamma); c) left bottom panel: the window is all made up of aftershocks that occurred in the first three hours after the main shock; the gamma density function is the best model and it has decisive strength of the evidence against the second best model (

q-exponential); d) right bottom panel: the window covers the period from April 24 to April 30, 2009; there is no more than a barely worth mentioning evidence in favor of the exponential density against the

q-exponential and gamma density functions. We note that the heavy-tailed

q-exponential distribution describes best the data set with the mass most concentrated on the left and skewned to the right, whereas the gamma density fits well the unimodal histogram associated with the aftershock set immediately following the main shock. The relative lack of very short interevent times is probably related to the temporary incompleteness of the catalog in that period.

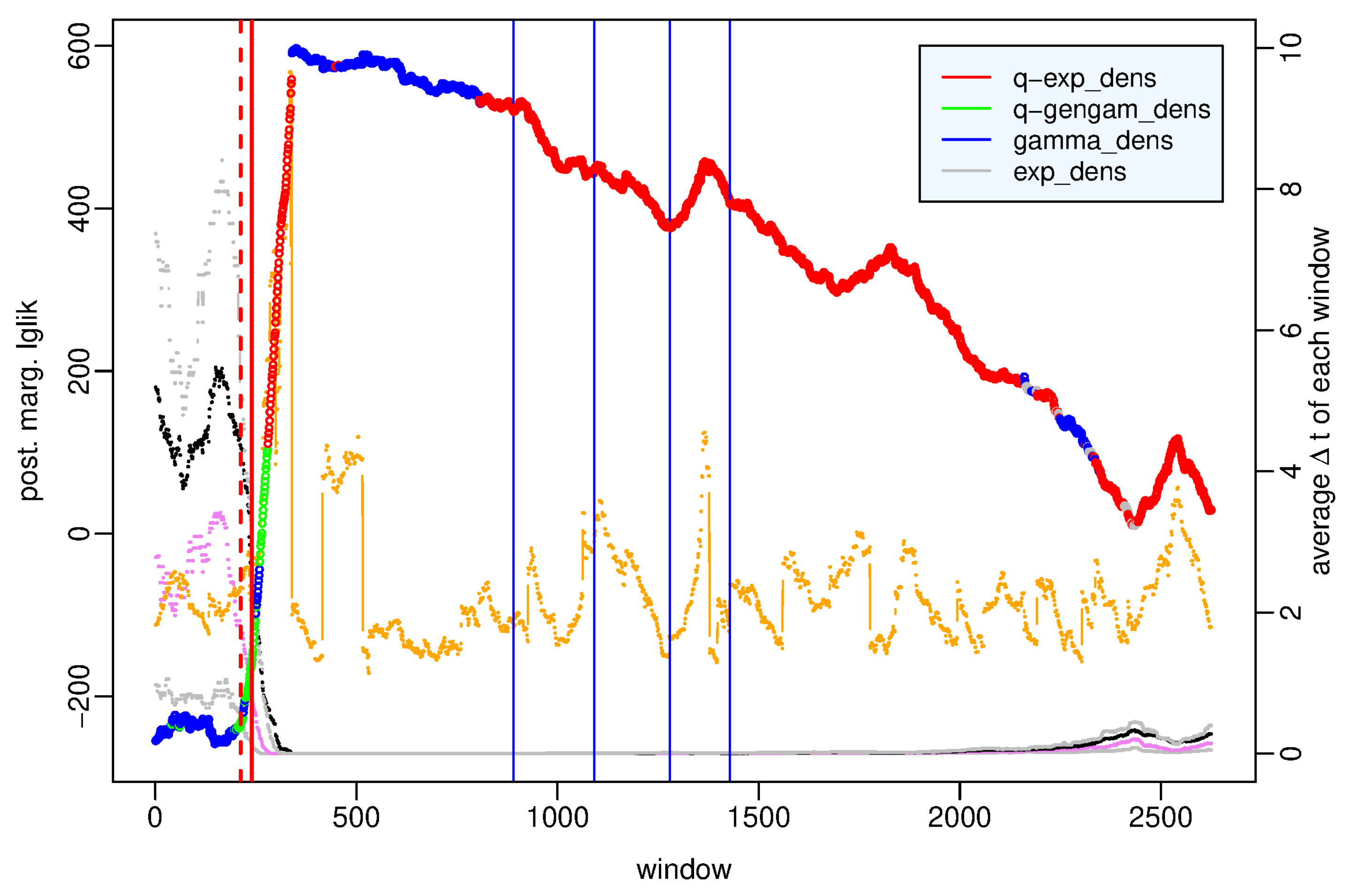

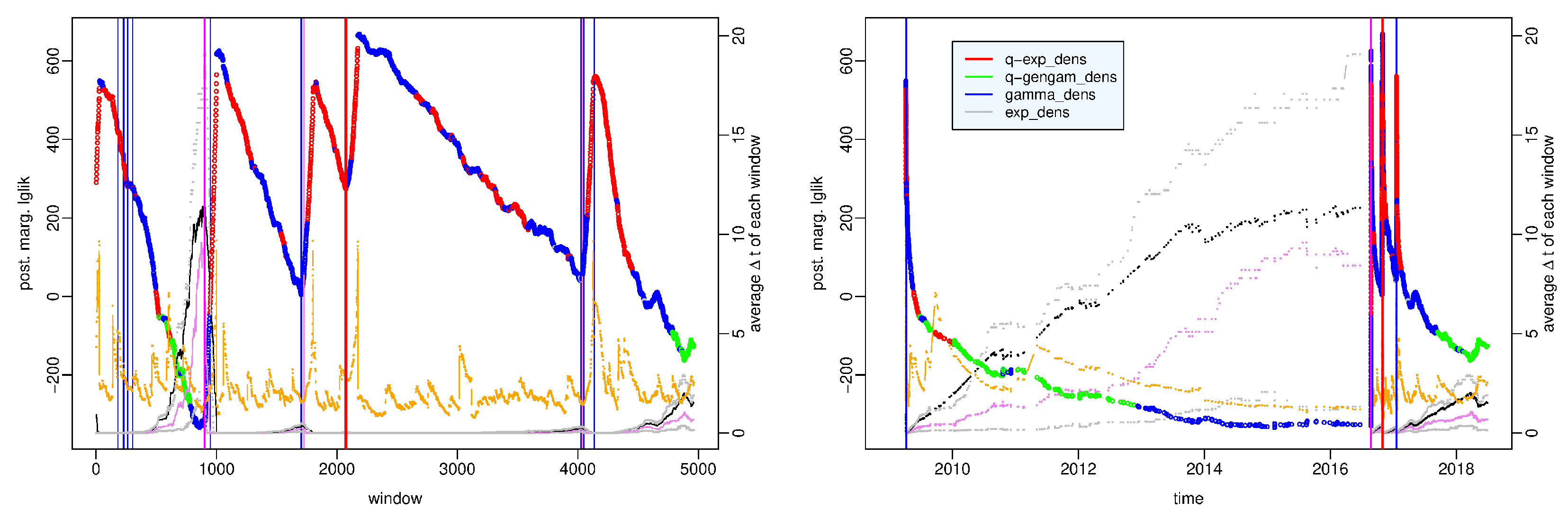

Figure 2 shows the largest value among the posterior marginal likelihoods of the four probability models at each time window; different colors highlight how the probability distribution that fits best the observations varies over time. To understand the motivations of these changes we analyze the characteristics of each data set by showing some of their statistical summaries such as first and third quartiles, median, mean and skewness. We remind that skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of the probability distribution. When it is positive, as in our cases, the right tail is longer and the mean is larger than the median; more precisely, the larger the skewness is, the more left-leaning the distribution is, that is, the more the observed intertimes are concentrated around short values; viceversa smaller skewness corresponds to more homogeneously distributed data in which the median is closer to (to the left of) the mean.

The time windows are divided as follows: in 1745 (66%) the

q-exponential distribution represents the best model, in 68 (2.6%) the

q-generalized gamma distribution, in 760 (29%) the gamma distribution, and in 52 (2%) the exponential distribution. We point out that the strength of the evidence in favor of the best distribution with respect to the second best model is strong just in about half of the time windows; in particular, as for the

q-exponential and the gamma distribution in 828 and 334 windows respectively, concentrated in the hours after the main shock, whereas as for the

q-generalized gamma and the exponential distribution in no window. Moreover we note that the difference among all of the four models is not particularly significant in 143 (∼ 5%, approximately from the 2300-th to 2450-th window) time windows mainly concentrated between May and June 2009; we address this issue in more detail in the

Supplementary Material. For brevity we will say hereinafter that the models are

interchangeable when the difference between their posterior marginal log-likelihoods does not exceed the threshold

.

We examine the characteristic features of each probability model; the q-exponential distribution shows very strong evidence with respect to the other distributions (the q-generalized gamma is the second best model) in the time windows over the main shock, that is, which include some pre-main shock event and some aftershock and during the aftershock sequence, in particular from the end of June. The gamma distribution exceeds the other distributions on the day of the main shock - April 6, 2009 - and is the second best model early in the aftershock sequence, often interchangeable with the best q-exponential model. Substantially the exponential distribution outperforms the other distributions with slight evidence only in a few time windows in May-June 2009.

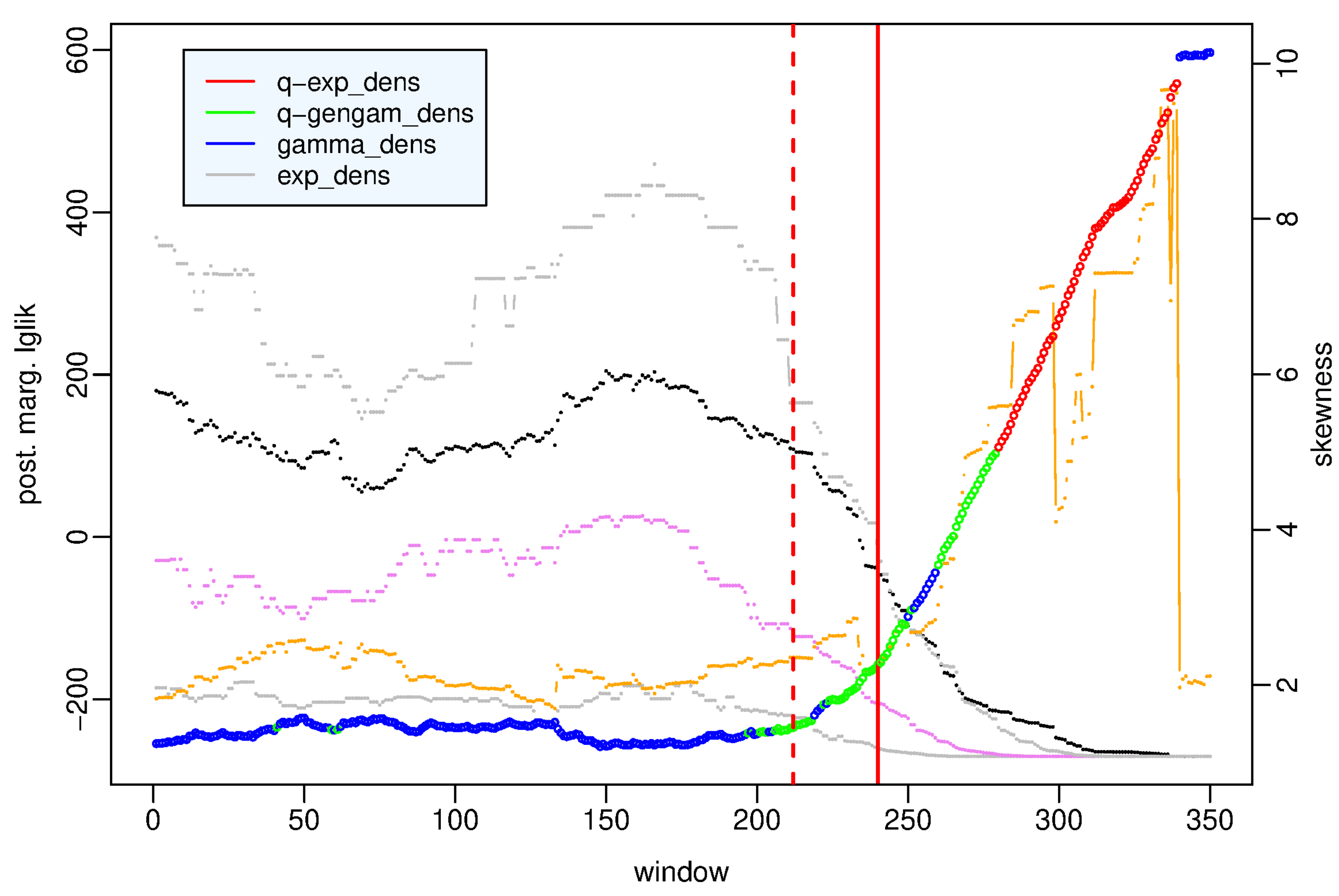

To better understand what happens before the main shock, in

Figure 3 we zoom on the first 350 time windows covering the period from 2005/04/07 to 2009/04/06 h. 4. The

q-generalized gamma distribution is the best model in the period from March 12, 2009 to April 6, 2009, a hour after the main shock; that is, the period that we can denote as preparatory phase in the seismic crisis because it includes the foreshock occurred on March 30, 2009 and denoted by a red dotted line in

Figure 3. In this period the

q-generalized gamma distribution is interchangeable with the gamma distribution but exceeds with strong evidence the other distributions. The role exchanges in the preceding period of background activity between April 2005 and March 2009, in which the gamma distribution is the best model, interchangeable with the

q-generalized gamma distribution and exceeding with strong evidence the other distributions (see the

Supplementary Material).

As for the statistical summaries we note that the preparatory phase is characterized by a constant decrease in the mean and in the median of the data sets approximately from the beginning of 2009, while overall the skewness increases up to April 2, 2009 and then decreases. This means that the interevent times get shorter between January and March 2009; obviously the minimum values of the mean and median are observed during the aftershock sequence.

4.2. Amatrice-Norcia Sequence

In 2016-2017 the junction area of the three regions Lazio. Marche, and Umbria in central Italy was hit by a complex sequence of destructive seismic events; on August 24, 2016 (01:36:32 UTC, latitude 42.698, longitude 13.234), an earthquake of

shook the city of Amatrice and caused about 300 fatalities. This shock, initially considered the main shock, later proved to be the foreshock of the

strongest shock that struck the city of Norcia on October 30, 2016 (06:40:17 UTC, latitude 42.830, longitude 13.109). The aftershock sequence lasted roughly up to July 2017 [

24] and recorded four

earthquakes on January 18, 2017. We consider 5062 events (

interevent times) which fall in the rectangular area of latitude size (42.3, 43.2) degrees and longitude size (12.7, 13.5) degrees and which span the temporal period from January 2014 to June 2018 taking

as the magnitude threshold in order to guarantee the completeness of the data set apart the first hours following the main shock on October 30, 2016.

We investigate the behavior of the four probability distributions, given in

Section 2, in

data sets, each of which obtained by shifting at each new event a time window constituted of 100 consecutive waiting times. First we evaluate the posterior marginal log-likelihood of each distribution in every time window by applying the MH algorithm to estimate the posterior distribution of the model parameters;

Table 1 shows the parameters of the prior distributions and the

coefficients used in the proposal distributions of the MH algorithm to obtain suitable acceptance rates. Comparing the pairwise differences between the four posterior marginal log-likelihoods with the value

of the Jeffreys scale we obtain the probability distribution with the best performance in each time window and the strength of its evidence with respect to the other distributions.

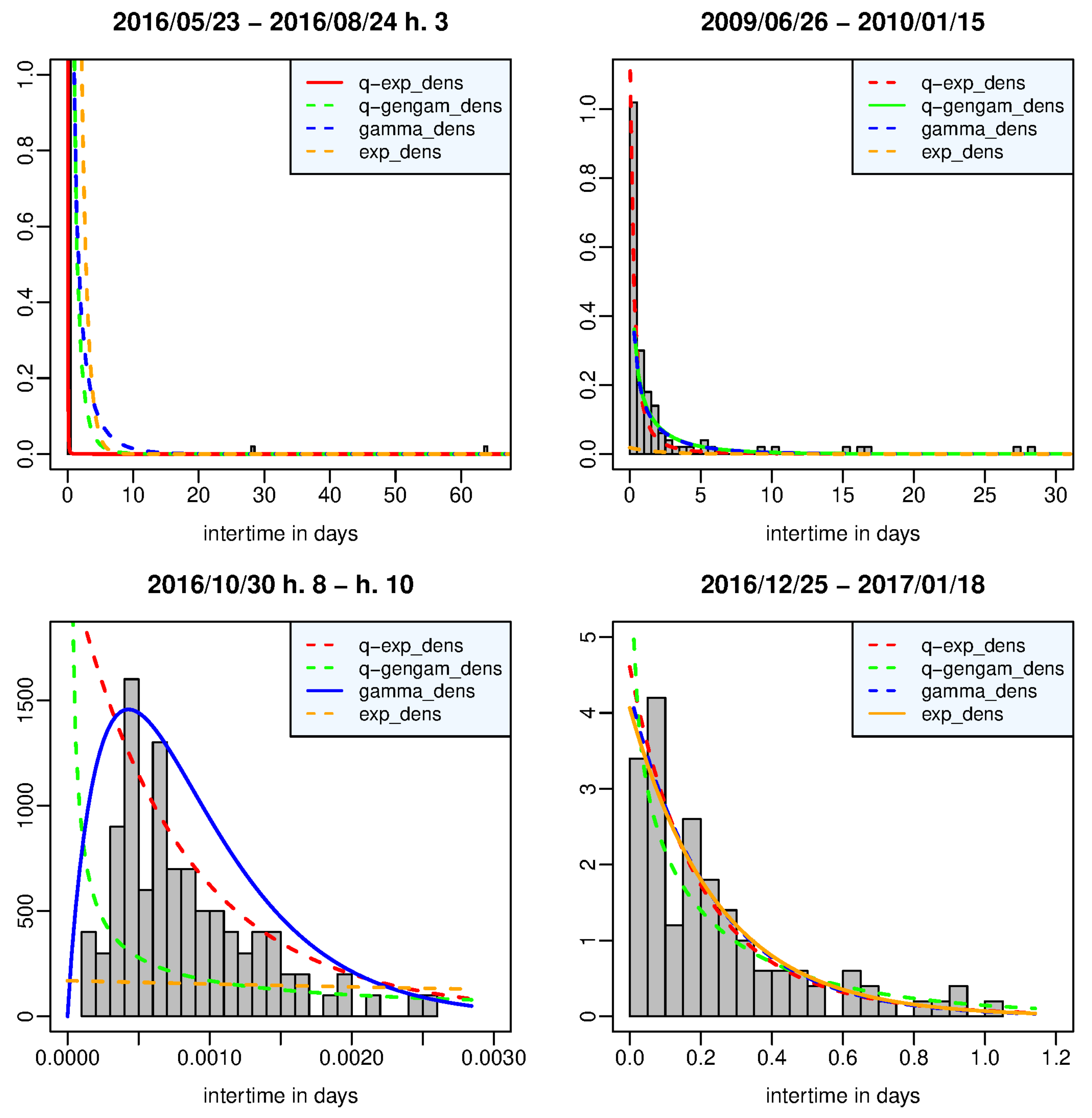

Figure 4 shows the estimated density functions and the histogram of the interevent times belonging to the time window in which each density function, represented by a solid line, provides respectively the best fit to the data, that is, it has its largest posterior marginal likelihood and the maximum difference from the likelihood of the second best density function. In particular, a) the left top panel refers to the time window which includes the first 98 aftershocks covering the two hours following the Amatrice shock which was preceded by two waiting times of approximately 28 and 63 days; the data set is therefore very right-skewned with long right tail, it is best described by the

q-exponential density function which outperforms the other distributions with decisive evidence; b) right top panel: the

q-generalized gamma distribution is the best model in the time window from June 26, 2009 to January 15, 2010 which includes the final part of the L’Aquila aftershock sequence; c) left bottom panel: the time window includes the aftershocks that occurred between h. 8 and h. 10 of the occurrence day of the Norcia main shock (October 30, 2016, 06:40:17 UTC); the gamma density function shows a decisive strength of evidence against the other probability distributions by adapting very well to the unimodal histogram of the interevent times which are probably missing the shorter ones due to the temporary incompleteness of the catalog after the strongest event; d) right bottom panel: the exponential distribution is interchangeable with the gamma and

q-exponential distribution in the time window from December 25, 2016 to January 18, 2017 when the first of the four

events occurs at Capitignano.

Figure 5 shows the value of the largest posterior marginal log-likelihood in each time window and the different colors indicate to which probability model this value corresponds; the

x axis represents the window number in the left panel and the time in the right panel. First and third quartiles, median, mean and skewness of each data set are shown to highlight how the distribution of the observations changes over time. The time windows are divided as follows: in 1825 (36.8%) the

q-exponential distribution represents the best model, in 360 (7.3%) the

q-generalized gamma distribution, in 2748 (55.4%) the gamma distribution, and in 29 (0.6%) the exponential distribution. The strength of the evidence in favor of the best distribution with respect to the second best model is strong or decisive just in about a third of the time windows, in which the outperforming distribution is especially

q-exponential or gamma; in particular, as for the

q-exponential, the

q-generalized gamma and the gamma distribution in 613, 12 and 1025 windows respectively, essentially concentrated in the hours after the strongest shocks, whereas as for the exponential distribution in no window. The

Supplementary Material provides a detailed visualisation of the time windows in which the strength of evidence in favor of a probability model is particularly significant and those in which it is not.

Let’s take a more thorough look at the behavior of the various distributions. The

q-exponential distribution is significantly the best model essentially in the first hours following the strongest earthquakes: from h. 5 to h. 8 of the day of occurrence of the L’Aquila earthquake (2009/04/06), from h. 2 to h. 3 of the day of occurrence of the Amatrice earthquake (2016/08/24), in the time windows including the first aftershocks of the Norcia earthquake (2016/10/30), and in the days of occurrence of the

shocks on January 18 and 19, 2017; in the other time windows in which it has the largest log-likelihood, always during the aftershock sequences, it is interchangeable with the gamma distribution (see the

Supplementary Material). The

q-generalized gamma distribution characterizes the periods from January 2010 to November 2012 and from September 2017 to the end of our study; the difference from the other distributions has strong evidence only in January 2010, while in the other time windows the

q-generalized gamma density is interchangeable with the gamma density (see the

Supplementary Material).

The gamma distribution has the largest value of the posterior marginal log-likelihood in most of the time windows - in almost half of them with strong or decisive evidence - and precisely in those that cover both part of the aftershock sequences (in particular the windows including the first forty aftershocks following the Amatrice shock and the first hours after the Norcia main shock) and the quiescence period from December 2012 to August 2016; in some of the first ones the gamma model is interchangeable with the

q-exponential model, while in the second ones it is interchangeable with the

q-generalized gamma model (see the

Supplementary Material).

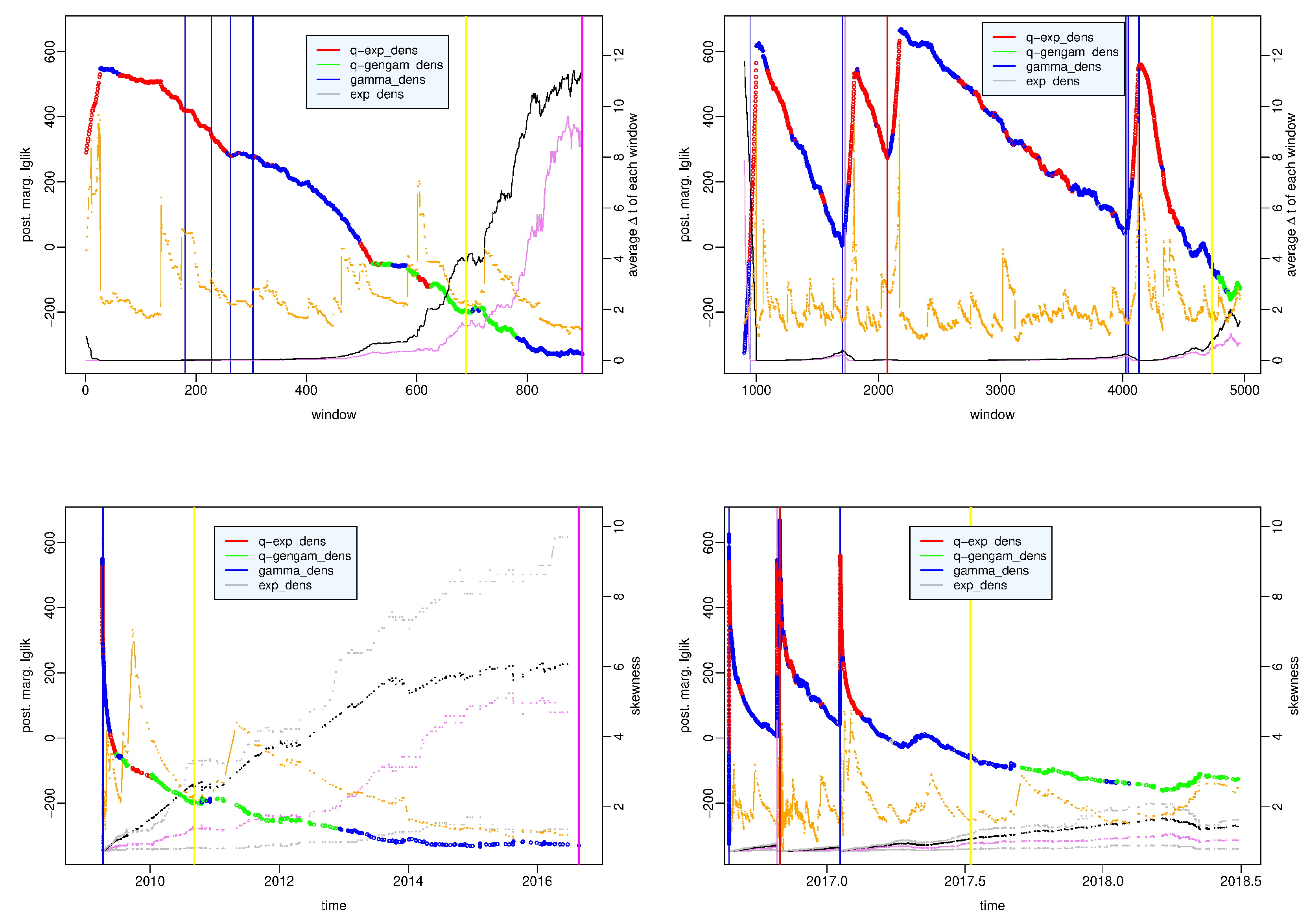

In

Figure 6 we distiguish the results obtained before the start of the Amatrice-Norcia seismic crisis (left panels) from those produced by the sequence of earthquakes following the Amatrice shock (right panels); the value of the largest posterior marginal log-likelihood is plotted versus the number of the time window in the top panels and versus time in the bottom panels. We note that the average interevent time and the likelihood are inversely correlated, i.e. the more the observed recurrence times are concentrated in short times, the greater the likelihood, or in other words the likelihood decreases as the seismic activity decreases. Furthermore, the gamma distribution is the best model in correspondence with the minimum values of likelihood: local minima before the shocks of greater magnitude and the absolute minimum reached on February 11, 2015. The years leading up to the onset of the Amatrice-Norcia seismic crisis are characterized by decreasing values of the log-likelihood and by the gamma distribution as the best model but with barely noteworthy evidence with respect to the

q-generalized gamma distribution which is the second best model; vice versa the

q-generalized gamma distribution is the best model and it is interchangeable with the gamma distribution in the years between the end of the L’Aquila aftershock sequence and the beginnig of 2013. Since 2009 the average interevent time has a constantly increasing trend which becomes almost flat starting from 2015 at the same time as the value of the median approaches that of the average.