Submitted:

08 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

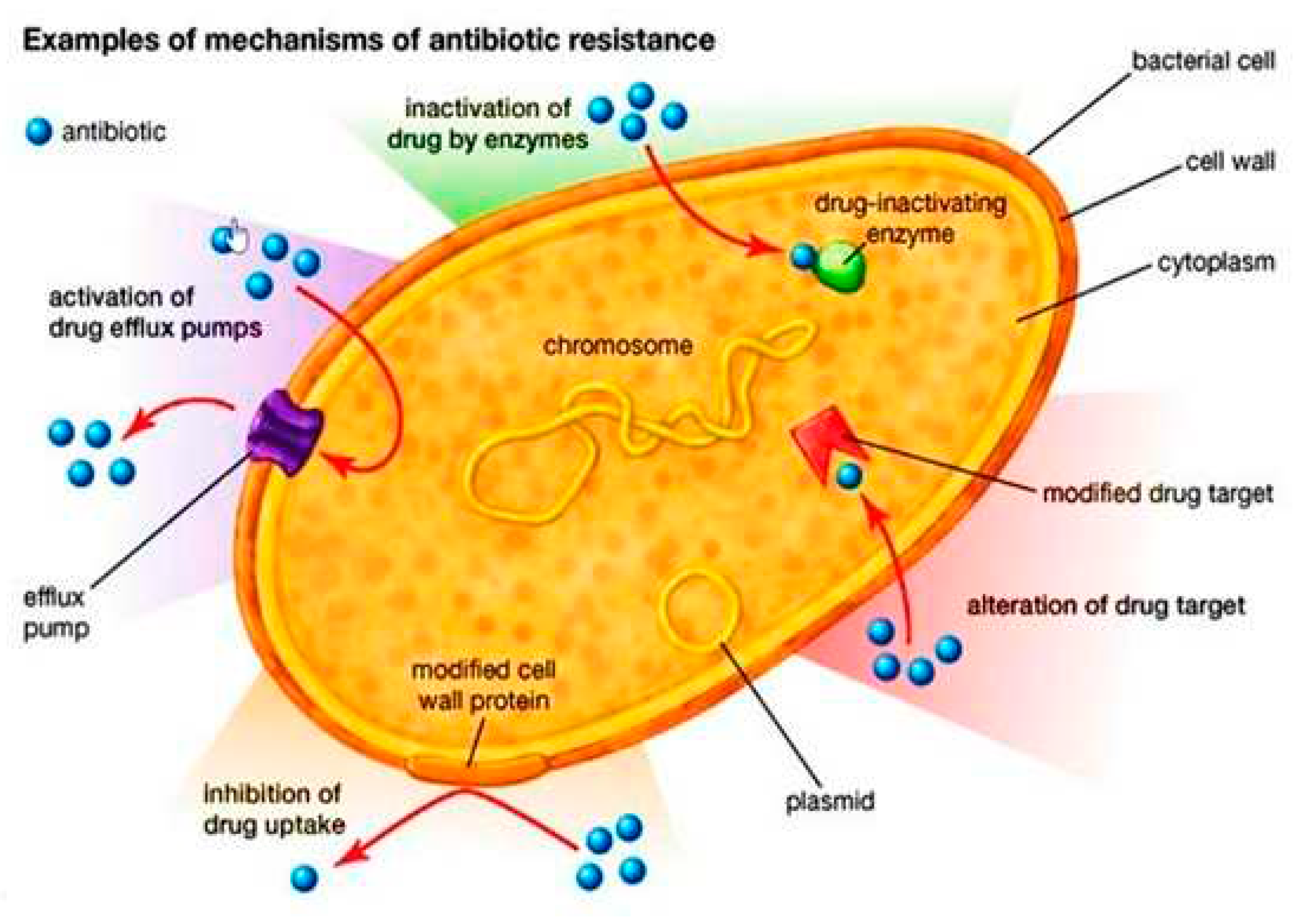

1. Introduction

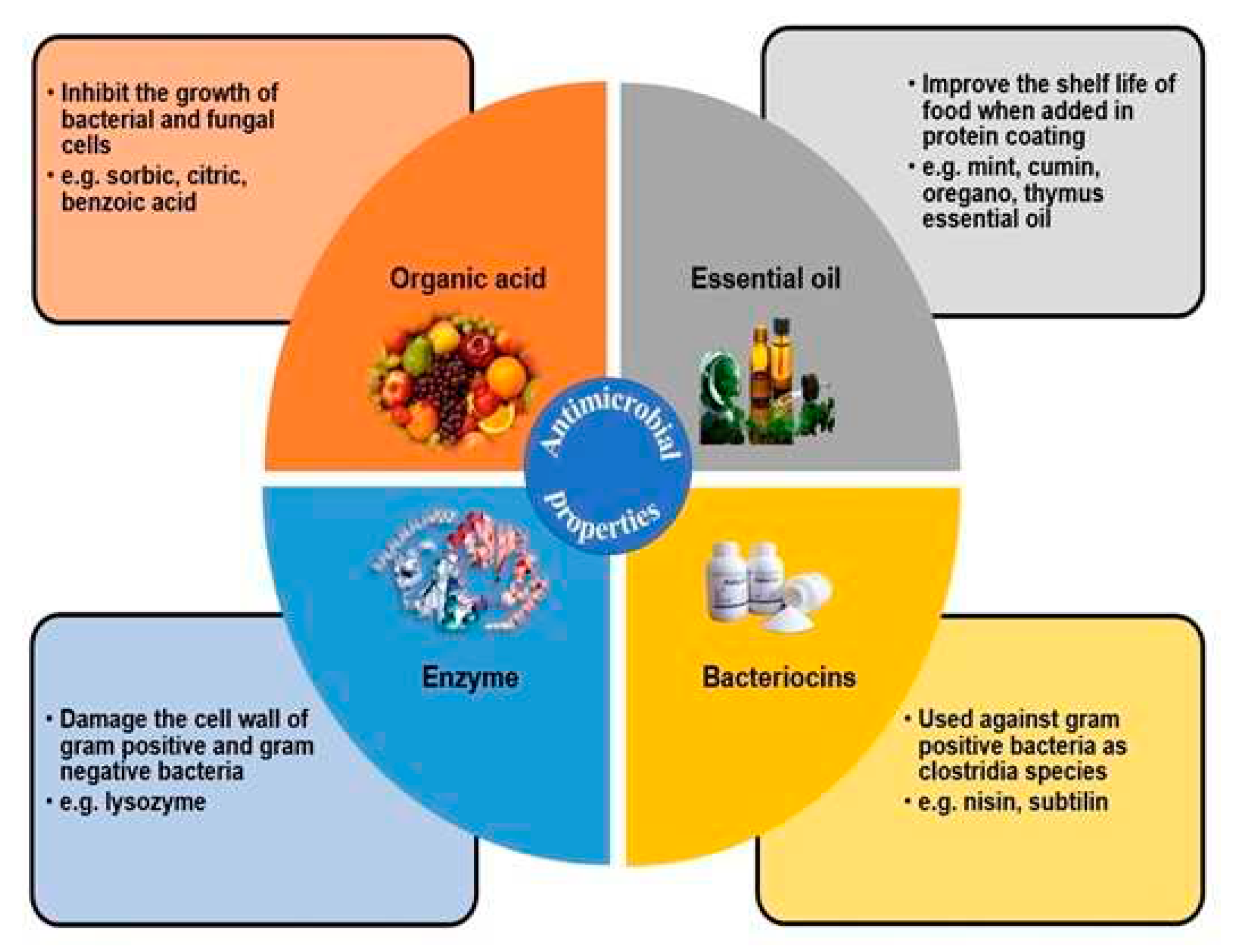

2. Antimicrobial Agents

2.1. Enzyme

2.2. The organic acids and salts

2.3. Bacteriocins

2.4. Natural extracts

2.5. Essential oils

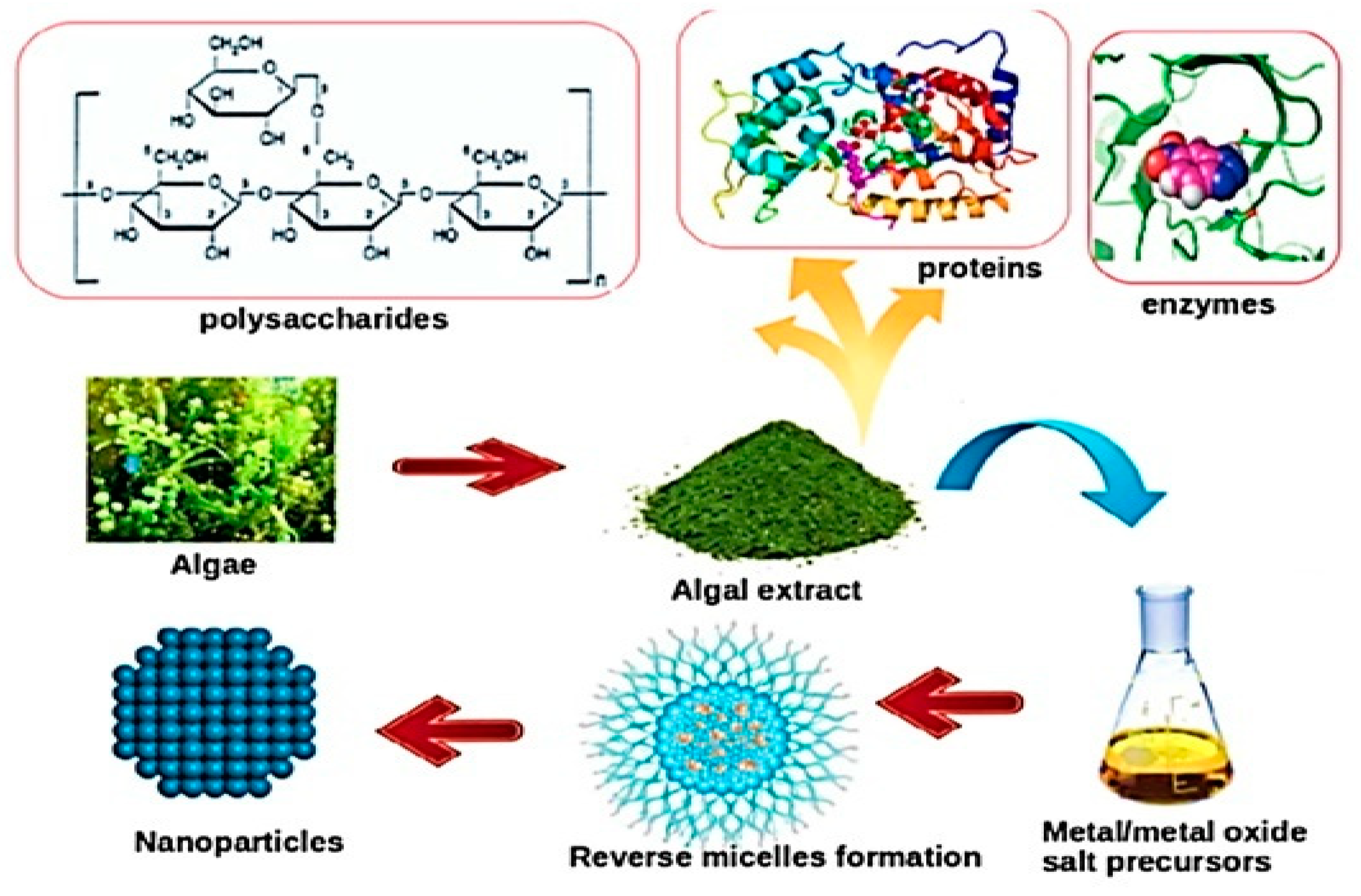

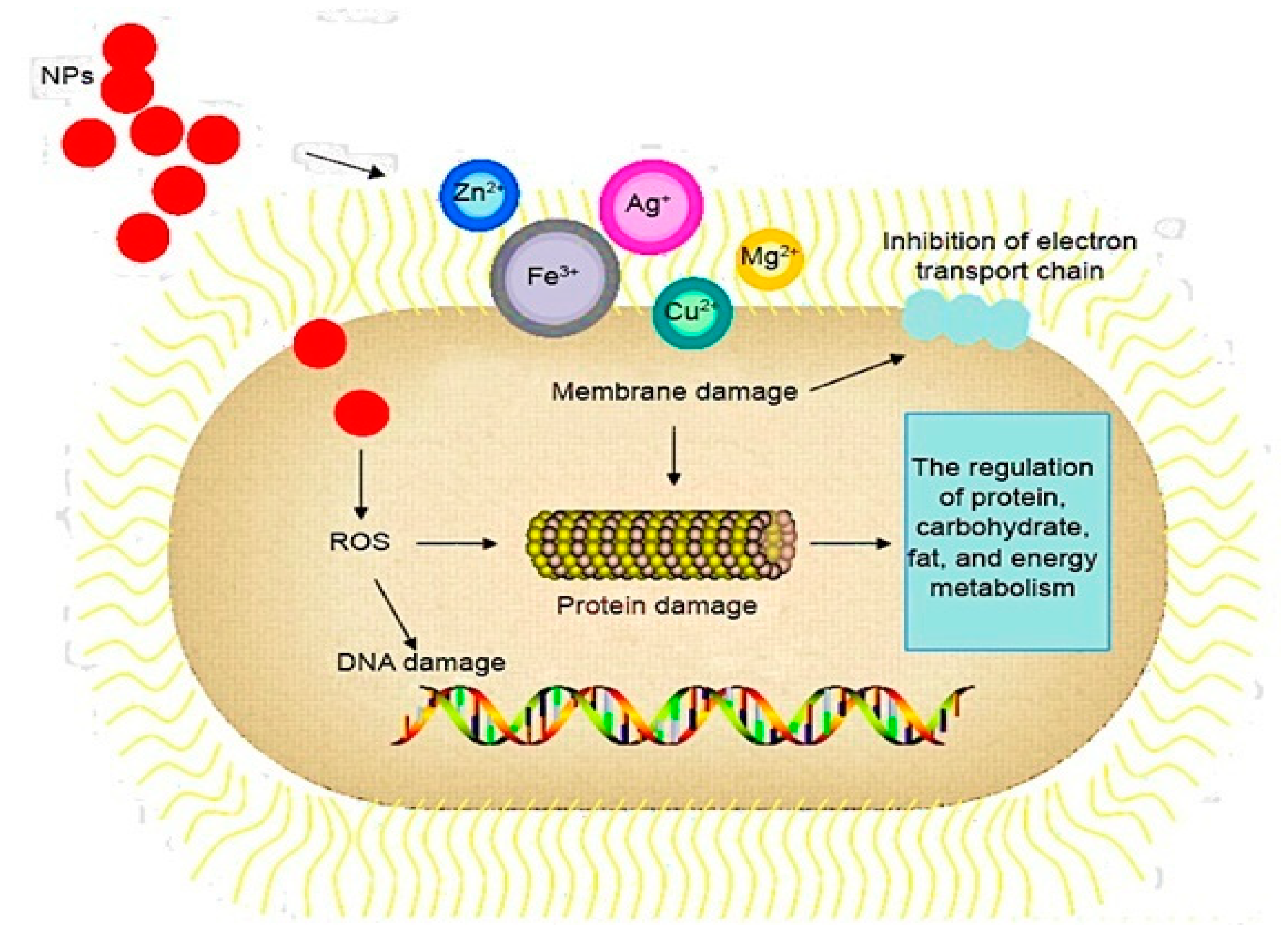

2.6. The metal nanoparticles

2.7. Bacteriophages

| Metal Nanoparticle | Packaging Material | Food product | Antimicrobial Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Silver (Ag) nanoparticle (NP) Ag NP’s |

Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) nanofibers | Culture media | The PAA-silver nanofibers achieved Zones of growth inhibition of C. albicans fungi and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcusaureus (MRSA) bacteria indicating their antimicrobial activity against both fungi and bacteria | [104] |

| Agar hydrogel | Latte cheese | Ag-based nanoparticle packaging system inhibited the growth of Pseudomonas spp. | [105] | |

| Polystyrene (PS) matrix | Culture media | The PS/Ag nanocomposites exhibred antimicrobial effect against gram pozitive, gram negative, yeast and fungal test microbe | [106] | |

| Chitosans/montmorillonite nanocomposite films | Culture media | The nanocomposite-AgNPs films inhibited the growth of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. | [107] | |

| Carboxymethyl Chitosan | Culture media | The prepared antibacterial membranes were effective and killed all bacteria | [108] | |

| Silver (Ag) nanoparticle+ quercetin | PVC-based film | Culture media | PVC based films containing silver nanoparticle and quercetin confirmed to be higly effective in inhibiting bacterial growth of food pathogens (L. monocytogenes, E. coli,S. Typhimurium) | [109] |

| Gold nanoparticles (AuNP’s) | Poly(vinyl) alcohol (PVA) crosslinked composite films | Banana | Banana shelf life has improved with PVA-glyoxal-AuNPs composite film | [110] |

| Silver nanoparticles (Ag-NP) and gold nanoparticles (Au-NP) | Chitosan nanocomposite films (CS) | Culture media | The prepared films were good antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aspergillus niger, Candida albicans | [111] |

| Titanium dioxide (TiO2) | Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) coated with alumina and titanium dioxide, hollow calcined titanium dioxide nanospheres (CSTiO2) | Culture media | Developed CSTiO2 hollow nanospheres exhibited higher antibacterial capacity against resistant E. coli strains, than S. aureus strains. when compared to commercial TiO2 nanoparticles, CSTiO2 nanospheres exhibited superior performance. In addition, the positive effect of UV irradiation on the antimicrobial activity was demonstrated. | [112] |

| TiO2–ZnO nanoparticle | Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) films | Fresh calf minced meat | ZnO-coated LDPE film and TiO2 coated LDPE film showed an excellent antibacterial effect on E. coli. But Mixed TiO2/ZnO-coatedLDPE films are not suitable option to inhibit E. coligrowth. | [113] |

| Ag + organoclay NPs | Starch from yellow dent corn | Culture media | Bio-nanocomposite films was significantly inhibited the growth of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. | [83] |

| Ag+TiO2 + Attapulgite +SiO2 NP’s | Polyethylene (PE) based nanocomposite master batch | Rice | Nano packaging material was exhibrit antimicrobial effects and maintained low O2 and high CO2 content in the packages. The packages inhibited the growth of molds and the production of fatty acids and reduced the oxidation of fats and proteins. | [114] |

| Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs | Starch-PVA composite films | Culture media | ZnO NPs were showed promising activity against S. typhimurium. | [7] |

| Olive flounder bone gelatin (OBG) | Spinach | OBG–ZnO film was showed antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes inoculated on spinach without affecting the quality of spinach, such as vitamin C content and color. | [115] | |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Culture media | decreased in E. coli growth by 3.14 log for 0.5% ZnO loading in the PLA coating layer | [116] | |

| Silver (Ag)-Cupper(Cu ) NP | Polylactide with cinnamon essentiol oil | Chicken meat | PLA composite films showed strong antimicrobial activity againstSalmonella Typhimurium, Campylobacter jejuni and Listeria monocytogenes on contaminated chicken meat samplesduring 21 days at 4 ° | [117] |

| MgO NP’s | Carboxymethyl (CM)-Chitosan CS | Culture media | CM-CS/MgO nanocomposite films exhibited antimicrobialactivity against L. monocytogenes and Shewanella baltica | [118] |

| Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) | Potato starch film | Culture media | The SeNPs/potato starch nanofilm inhibited growth of Salmonella Typhimurium and E. coli,slightly inhibited B. cereus, but no inhibition occurred with L. innocua. | [119] |

| Silica nanoparticles (SiO2) | Poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) | Culture media | The antibacterial activity of PHBV/SiO2 (2.0%) nanocomposites,94.7% growth inhibition for E. coli and 92% for S. aureus | [120] |

| Aluminu+ doped zincoxide (AZO) | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Culture media | Great antibacterial activity against E. coli | [121] |

| Zinc oxide−silver nanocomposites (ZnO−Ag NCs). | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)-chitosan (PHBV-CS) | Culture media | The nanocomposites PHBV/Ag–ZnO (10%) showed great antimicrobial activity potent against S. aureus and E. coli if compared with nanocomposites Ag-ZnO 5%, 3% and 1% | [122] |

3. The Antimicrobial Packaging Methods

3.1. Adding sachets or pads containing antimicrobial agents to packages

3.2. Addition of antimicrobial agents directly into the polymer

3.3. The coating of antimicrobial agent on polymer surface

3.4. Addition of the antimicrobial agent to the polymers

3.5. The natural antimicrobial polymer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Dainelli, D.; Gontard, N.; Spyropoulos, D.; Zondervan-van den Beuken, E.; Tobback, P. Active and intelligent food packaging: legal aspects and safety concerns. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2008, 19, S103–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.; Kochhar, A. Active packaging in food ındustry: A review. IOSR J. Environ. Sci., Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014, 8, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divsalar, E.; Tajik, H.; Moradi, M.; Forough, M.; Lotfi, M.; Kuswandi, B. Characterization of cellulosic paper coated with chitosan-zinc oxide nanocomposite containing nisin and its application in packaging of UF cheese. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 109, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, H.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Peressini, D. Physical, mechanical, and antibacterial characteristics of bio-nanocomposite films loaded with Ag-modified SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles. J Food Sci. 2020, 85, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L. Moisture-triggered release of self-produced ClO2 gas from microcapsule antibacterial film system. J Mater Sci. 2018, 53, 12704–12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintsis, T. Foodborne pathogens. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 529–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumar, A.; Heera, K.V.; Sumi, T.S.; Joseph, M.; Mathew, S.; Praveen, G.; Nair, I.C.; Krishnankutty, R.E. Starch-PVA composite films with zinc-oxide nanoparticles and phytochemicals as intelligent pH sensing wraps for food packaging application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019, 136, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, G.; Demirci, C.; Özpınar, H. Proporties and synthesis of biosilver nanofilms for antimicrobial food packaging. Polymers. 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G.; Çelik, B.Y. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial bio-nano films for food packaging. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2019, 54, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrucka, R. Antimicrobial packaging with natural compunds: A review. Logforum. 2016, 12, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Sillard, C.; Naceur Belgacem, M.; Bras, J. Nisin anchored cellulose nanofibers for long term antimicrobial active food packaging. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 12422–12430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril, R.; Nerín, C.; Silva, F. Encapsulation systems for antimicrobial food packaging components: An update. Molecules. 2020, 25, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaneghah, A.M.; Hashemi, S.M.B.; Es, I.; Fracassetti, D.; Limbo, S. Efficacy of antimicrobial agents for food contact applications: Biological activity, incorporation into packaging, and assessment methods: A review. J Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasour, M.S.; Ehsani, A.; Mehryar, L.; Naghibi, S.S. Chitosan coating incorporated with the lactoperoxidase system: An active edible coating for fish preservation. J Sci Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo-Martínez, M.M.; Tello-Solís, S.R.; García-Sánchez, M.A.; Ponce-Alquicira, E. Antimicrobial activity and hydrophobicity of edible whey protein ısolate films formulated with nisin and/or glucose oxidase. J Food Sci. 2013, 78, M560–M566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsuwan, J.; Rattanapanone, N.; Pongsirikul, I. Development of active chitosan films incorporating potassium sorbate or vanillin to extend the shelf life of butter cake. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2014, 50, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, J.U. Design of bio-based materials derived from food industry wastes. Intern doctorate thesis. Chem Engin and Envir Engin. Univ Basque Country (Spain). 2020.

- Birck, C.; Degoutin, S.; Maton, M.; Neut, C.; Bria, M.; Moreau, M.; Fricoteaux, F.; Miri, V.; Bacquet, M. Antimicrobial citric acid/poly (vinyl alcohol) crosslinked films: Effect of cyclodextrin and sodium benzoate on the antimicrobial activity. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016, 68, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Feng, S.; Ahmed, S.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y. Effect of potassium sorbate and ultrasonic treatment on the properties of fish scale collagen /polyvinyl alcohol composite. Molecules. 2019, 24, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño-Garza, M.Z.; García, S.; del Socorro Flores-González, M.; Arévalo-Niño, K. Edible active coatings based on pectin,pullulan, and chitosan increase quality and shelf life of strawberries (Fragaria ananassa). J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, M1823–M1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peighambardoust, S.H.; Fasihnia, S.H.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Lorenzo, J.M. Active Polypropylene-Based Films Incorporating Combined Antioxidants and Antimicrobials: Preparation and Characterization. Foods 2021, 10, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Jin, J.; Yang, W.; Xie, Y. Development and antilisterial activity of PE-based biological preservative films incorporating plantaricin BM-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2017, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, P.; Mombrú, Á.W.; Mombrú, D.; Castro, A.; Villanueva, J.P.; Pardo, H.; Rufo, C. Physico-chemical and antilisterial properties of nisin-incorporated chitosan/carboxymethyl chitosan films. Carbohyd Polym. 2019, 219, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T. Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in skim milk and liquid egg white by antimicrobial bottle coating with polylactic acid and nisin. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, M83–M88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meira, S.M.M.; Zehetmeyer, G.; Scheibel, J.M.; Werner, J.O.; Brandelli, A. Starch-halloysite nanocomposites containing nisin: Characterization and inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in soft cheese. LWT 2016, 68, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiros, P.S.; Sant’Anna, V.; Barbosa, M.S.; Brandelli, A.; Franco, B.D.G.M. Effect of liposome-encapsulated nisin and bacteriocinlike substance P34 on Listeria monocytogenes growth in Minas frescal cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 156, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.-K.; Han, E.J.; Han, K.J.; Paik, H.-D. Antimicrobial effect of Bacteriocin KU24 produced by Lactococcus lactis KU24 against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Food. Sci. 2013, 78, M465–M469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseppi, A.; Pilati, F.; Marini, M.; Toselli, M.; de Niederhäusern, S.; Guerrieri, E.; Messi, P.; Sabia, C.; Manicardi, G.; Anacarso, I.; et al. Anti-listerial activity of a polymeric film coated with hybrid coatings doped with Enterocin 416K1 for use as bioactive food packaging. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 123, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.; De, L.; Funck, G.D.; Dannenberg, G.S.; Cruxen, C.E.S.; Halal, S.L.M.E.; Dias, A.R.G.; Fiorentini, Â.M.; Silva, W.P.D. Bacteriocin-like substances of Lactobacillus curvatus P99, Characterization and application in biodegradable films for control of Listeria monocytogenes in cheese. Food Microbiol. 2017, 63, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degli Esposti, M.; Toselli, M.; Sabia, C.; Messi, P.; De Niederhäusern, S.; Bondi, M.; Iseppi, R. Effectiveness of polymeric coated films containing bacteriocin-producer living bacteria for Listeria monocytogenes control under simulated cold chain break. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xie, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H. Development and application of an active plastic multilayer film by coating a plantaricin bm-1 for chilled meat preservation. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Massani, M.; Fernandez, M.R.; Ariosti, A.; Eisenberg, P.; Vignolo, G. Development and characterization of an active polyethylene film containing Lactobacillus curvatus CRL705 bacteriocins. Food Addit. Contam. Part A. 2008, 25, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasour, M.S.; Ehsani, A.; Mehryar, L.; Naghibi, S.S. Chitosan coating incorporated with the lactoperoxidase system: An active edible coating for fish preservation. J Sci Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lan, W. Fabrication of antibacterial chitosan-PVA blended film using electrospray technique for food packaging applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 107, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugatti, V.; Vertuccio, L.; Viscusi, G.; Gorrasi, G. Antimicrobial membranes of bio-based pa 11 and hnts filled with lysozyme obtained by an electrospinning process. J Nanomater. 2018, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Xu, H.; Xue, Y.; Huang, R.; Deng, H.; Pan, S. Layer-by-layer immobilization of lysozyme–chitosan–organic rectorite composites on electrospun nanofibrous mats for pork preservation. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, J. Binary grafted chitosan film: Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial activity and prospects for food packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 115, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, F.; Kahraman, M.V. Preparation and characterization of hybrid cationic hydroxyethyl cellulose/sodium alginate polyelectrolyte antimicrobial films. Polym Adv Technol. 2018, 29, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasti, T.; Dixit, S.; Hiremani, V.D.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P.; Vootla, S.K.; Mudigoudra, B.S. Chitosan/pullulan-based films incorporated with clove essential oil loaded chitosan-ZnO hybrid nanoparticles for active food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Dutta, P.K. Chitosan based ZnO nanoparticles loaded gallic-acid films for active food packaging. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Marques, A.; Milho, C.; Costa, M.J.; Pastrana, L.M.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Sillankorva, S.M. Bacteriophage ϕIBB-PF7A loaded on sodium alginate-based films to prevent microbial meat spoilage. Int J Food Microbiol. 2019, 291, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarillas, L.; Lightbourn-Rojas, L.; Angulo-Gaxiola, A.K.; Basilio Heredia, J.; González-Robles, A.; León-Félix, J. The antibacterial effect of chitosan-based edible coating incorporated with a lytic bacteriophage against Escherichia coli O157, H7 on the surface of tomatoes. J Food Saf. 2018, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjadi, S.; Emaminia, S.; Heyat Davudian, S.; Pourmohammad, S.; Hamishehkar, H.; Roufegarinejad, L. Preparation and characterization of gelatin-based nanocomposite containing chitosan nanofiber and ZnO nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2019, 216, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Chi, H.; Lin, L.; Lan, T.; Han, P.; Chen, H.; Qin, Y. Development of antimicrobial packaging film made from poly (lactic acid) incorporating titanium dioxide and silver nanoparticles. Molecules. 2017, 22, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Wang, L.F.; Rhim, J.W. Preparation and properties of carbohydrate-based composite films incorporated with CuO nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2017, 169, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Nerín, C.; Batlle, R. New cinnamon-based active paper packaging against Rhizopusstolonifer food spoilage. J Agric Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6364–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Liao, X.; Cui, H. Cold plasma treated thyme essential oil/silk fibroin nanofibers against Salmonella Typhimurium in poultry meat. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2019, 21, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleva, P.; Bartošová, L.; Mácalová, D.; Zálešáková, L.; Sedlaríková, J.; Janalíková, M. biofilm formation reduction by eugenol and thymol on biodegradable food packaging material. Foods 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, S.; Warner, R.D.; Fang, Z. Effect of oregano essential oil and resveratrol nanoemulsion loaded pectin edible coating on the preservation of pork loin in modified atmosphere packaging. Food Control 2020, 114, 107226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Ficai, A.; Trusca, R.-D.; Ilie, C.-I.; Oprea, O.-C.; Andronescu, E. Innovative antimicrobial chitosan/ ZnO/AgNPs/Citronella essential oil nanocomposite-Potential coating for grapes. Foods 2020, 9, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardjoum, N.; Chibani, N.; Shankar, S.; Fadhel, Y.B.; Djidjelli, H.; Lacroix, M. Development of antimicrobial films based on poly(lactic acid) incorporated with Thymus vulgaris essential oil and ethanolic extract of Mediterranean propolis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.F.; Rhim, J.W. Preparation and application of agar/alginate/collagen ternary blend functional food packaging films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015, 80, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Kan, J.; Jin, C. Effect of gallic acid grafted chitosan film packaging on the postharvest quality of white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Postharvest Biol Technol. 2019, 147, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H. Postharvest chitosan-g-salicylic acid application alleviates chilling injury and preserves cucumber fruit quality during cold storage. Food Chem. 2015, 174, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Pompa, S.; Rojas-Molina, R.; Aguilera-Carbó, A.F.; Saenz-Galindo, A.; de La Garza, H.; Jasso-Cantú, D.; Aguilar, C.N. Edible film based on candelilla wax to improve the shelf life and quality of avocado. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Yong, H.; Zong, S.; Jin, C.; Liu, J. Effect of ferulic acid-grafted-chitosan coating on the quality of pork during refrigerated storage. Foods 2021, 10, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Curcumin incorporated poly(butyleneadipate-co-terephthalate) film with improved water vapor barrier and antioxidant properties. Materials 2020, 13, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Quesada, A.C.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A. Antimicrobial properties and release of cinnamaldehyde in bilayer films based on polylactic acid (PLA) and starch. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 73, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzare, M.; Moniri, R.; Azar, H.H.; Mehrasbi, M.R. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial interactions between resveratrol and eugenol in carboxymethyl cellulose biodegradable film. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.R.; da Silva, A.F.; Amaral, V.C.; Ribeiro, A.B.; de Abreu Filho, B.A.; Mikcha, J.M. Application of edible coating with starch and carvacrol in minimally processed pumpkin. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaah, C.; Li, J.; Lee, J.; Pascall, M.A. Antimicrobial activity of chitosan-based films enriched with green tea extracts on murine norovirus, Escherichia coli, and Listeria innocua. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 3941924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amankwaah, C.; Li, J.; Lee, J.; Pascall, M.A. Development of antiviral and bacteriostatic chitosan-based food packaging material with grape seed extract for murine norovirus, Escherichia coli and Listeria innocua control. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6174–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliarulo, C.; Sansone, F.; Moccia, S.; Russo, G.L.; Aquino, R.P.; Salvatore, P.; Di Stasio, M.; Volpe, M.G. Preservation of strawberries with an antifungal edible coating using peony extracts in chitosan. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2016, 9, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yue, J.; Gong, X.; Qian, B.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, Y. Blueberry leaf extracts incorporated chitosan coatings for preserving postharvest quality of fresh blueberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 92, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Guerra, H.E.; Castillo-Yañez, F.J.; Montaño-Cota, E.A.; Ruíz-Cruz, S.; Márquez-Ríos, E.; Canizales-Rodríguez, F.; Torres-Arreola, W.; Montoya-Camacho, N.; Ocaño-Higuera, V.M. Protective effect of an edible tomato plant extract/chitosan coating on the quality and shelf life of Sierra fish fillets. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 2436045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, A.; Bowers, J.W.J.; Bauermeister, L.J.; Singh, M.; Huang, T.S.; Mckee, S.R. Effect of salts of organic acids on Listeria monocytogenes, shelf life, meat quality, and consumer acceptability of beef frankfurters. J Food Sci. 2014, 79, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jideani, V.A.; Vogt, K. Antimicrobial packaging for extending the shelf life of bread: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016, 56, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcano, M.; De, J.; Jahn, R.C.; Scherer, C.D.; Wigmann, É.F.; Moraes, V.M.; Garcia, M.V.; Mallmann, C.A.; Copetti, M.V. Susceptibility of Aspergillus spp. to acetic and sorbic acids based on pH and effect of sub-inhibitory doses of sorbic acid on ochratoxin A production. Food Res Int. 2016, 81, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Du, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Effects of sorbic acid-chitosan microcapsules as antimicrobial agent on the properties of ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer film for food packaging. J Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woraprayote, W.; Pumpuang, L.; Tosukhowong, A.; Roytrakul, S.; Perez, R.H.; Zendo, T.; Sonomoto, K.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W. Two putatively novel bacteriocins active against Gram-negative food borne pathogens produced by Weissella hellenica BCC 7293. Food Control. 2015, 55, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Tufail, T.; Ahmad, A. Use of natural antimicrobial agents: A safe preservation approach. Active Antimicrobial Food Packaging. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baysal, G.; Kasapbası, E.E.; Yavuz, N.; Hür, Z.; Genç, K.; Genç, M. Determination of theoretical calculations by DFT method and investigation of antioxidant, antimicrobial properties of olive leaf extracts from different regions. J Food Sci Technol. 2021, 58, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manso, S.; Becerril, R.; Nerín, C.; Gómez-Lus, R. Influence of pH and temperature variations on vapor phase action of an antifungal food packaging against five mold strains. Food Control. 2015, 47, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jia, J.; Duan, S.; Zhou, X.; Xiang, A.; Lian, Z.; Ge, F. Zein/MCM-41 nanocomposite film incorporated with cinnamon essential oil loaded by modified supercritical CO2 impregnation for long-term antibacterial packaging. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, H.J.; Song, K. Bin. Production and characterisation of skate skin gelatin films incorporated with thyme essential oil and their application in chicken tenderloin packaging. Int J Food Sci. 2016, 51, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Tahergorabi, R. Impact of sweet potato starch-based nanocomposite films activated with thyme essential oil on the shelf-life of baby spinach leaves. Foods. 2017, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, J.V.; Rawles, S.D.; Xiong, Y.L.; Newman, M.C.; Thompson, K.R.; Webster, C.D. Listeria monocytogenes is inhibited on fillets of cold-smoked sunshine bass, Morone chrysops × Morone saxatilis, with an edible corn zein-based coating incorporated with lemongrass essential oil or nisin. J World Aquac Soc. 2019, 50, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacı, D.; Iorio, G.; Sozbilen, G.S.; Alkan, D.; Trabattoni, S.; Pucillo, F.; Farris, S.; Yemenicioğlu, A. Development of flexible antimicrobial zein coatings with essential oils for the inhibition of critical pathogens on the surface of whole fruits: Test of coatings on inoculated melons. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2019, 20, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G.; Olcay, H.S.; Günneç, Ç. Encapsulation and antibacterial studies of goji berry and garlic extract in the biodegradable chitosan. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.; Slay, B.; Knackstedt, M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Antimicrobial activity of metal and metal-oxide based nanoparticles. Adv Ther. 2018, 1, 1700033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G.; Aydın, H.; Uzan, S.; Hoşgören, H. Investigation of Antimicrobial Properties of QASs+ (Novel Synthesis). Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018, 12, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G. In Vıtro Cytotoxıcıty Analysıs And Synthesıs Of Bıocıdal Allıcın/Mt/Mma/Peg/Poss Nanocomposıtes For The Food Packagıng. Journal of Food. 2020, 45, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G.; Doğan, F. Investigation and preparation of biodegradable starch-based nanofilms for potential use of curcumin and garlic in food packaging applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2020, 31, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; Soares, N.; De, F. F.; Teófilo, R.F.; Coimbra, J.S.; Dos, R.; Vitor, D.M.; Batista, R.A.; Ferreira, S.O.; De Andrade, N.J.; et al. Physical-mechanical and antimicrobial properties of nanocomposite films with pediocin and ZnO nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2013, 94, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tayyar, N.A.; Youssef, A.M.; Al-hindi, R. Antimicrobial food packaging based on sustainable bio-based materials for reducing foodborne pathogens: A review. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Y.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Karkaj, S.Z. Development of antibacterial carboxymethyl cellulose-based nanobiocomposite films containing various metallic nanoparticles for food packaging applications. J Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2537–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bbosa, G.; Mwebaza, N.; Odda, J.; Kyegombe, D.B. Antibiotics/antibacterial drug use, their marketing and promotion during the post-antibiotic golden age and their role in emergence of bacterial resistance. Health 2014, 6, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Namratha, K.; Ilyas, S.; Hezam, A.; Mathur, S.; Byrappa, K. Smart fortified PHBV-CS biopolymer with ZnO-Ag nanocomposites for enhanced shelf life of food packaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019, 11, 48309–48320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnuvarthanan, M.; Rajeswari, N. Preparation and characterization of carrageenan/silver nanoparticles/Laponite nanocomposite coating on oxygen plasma surface modified polypropylene for food packaging. J Food Sci Technol. 2019, 56, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, A.; Anany, H.; Hakeem, M.; Aguis, L.; Avdjian, A.C.; Bouget, M.; Atashi, A.; Brovko, L.; Rochefort, D.; Griffiths, M.W. Development of prototypes of bioactive packaging materials based on immobilized bacteriophages for control of growth of bacterial pathogens in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016, 217, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Niu, Y.D.; Nan, Y.; Stanford, K.; Holley, R.; McAllister, T.; Narváez-Bravo, C. SalmoFreshTM effectiveness in controlling Salmonella on romaine lettuce, mung bean sprouts and seeds. Int J Food Microbiol. 2019, 305, 108250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerin, C.; Silva, F.; Manso, S.; Becerril, R. The downside of antimicrobial packaging: Migration of packaging elements into food. Antimicrobial Food Packaging. 2016, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Kanchi, S.; Bisetty, K. Biogenic synthesis of nanoparticles: A review. Arab J Chem. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: Present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1227–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan Tas, B.; Sehit, E.; Erdinc Tas, C.; Unal, S.; Cebeci, F.C.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Unal, H. Carvacrol loaded halloysite coatings for antimicrobial food packaging applications. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2018, 20, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Pang, C.; Deng, W.; Xu, C.; Wang, X. Multifunctional chitosan-based coating with liposomes containing laurel essential oils and nanosilver for pork preservation. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Lee, S. Encapsulation of phytoncide in nanofibers by emulsion electrospinning and their antimicrobial assessment. Fibers Polym. 2018, 19, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, E.S.; Galhoum, G.F.; Mohamed, E.N. Curcumin loaded nanoemulsions/pectin coatings for refrigerated chicken fillets. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 83, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G.; Olcay, H.S.; Keresteci, B.; Özpınar, H. The antioxidant and antibacterial properties of chitosan encapsulated with the bee pollen and the apple cider vinegar. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2022, 33, 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, G.; Olcay, H.S.; Günneç, Ç. Encapsulation and antibacterial studies of goji berry and garlic extract in the biodegradable chitosan. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, E.; Keresteci, B.; Günneç, C.; Baysal, G. Encapsulation applications and production techniques in the food industry. J. Nutr. Health Sci. 2020, 7, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Bai, M.; Lin, L. Plasma-treated poly (ethylene oxide) nanofibers containing tea tree oil/beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complex for antibacterial packaging. Carbohydr Polym. 2018, 179, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Ramakanth, D.; Akhila, K.; Gaikwad, K.K. Edible films and coatings for food packaging applications: A review. Environ Chem Lett. 2022, 20, 875–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofidfar, M.; Kim, E.S.; Larkin, E.L.; Long, L.; Jennings, W.D.; Ahadian, S.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Wnek, G.E. Antimicrobial activity of silver containing crosslinked poly(acrylic acid) fibers. Micromachines. 2019, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incoronato, A.L.; Conte, A.; Buonocore, G.G.; Del Nobile, M.A. Agar hydrogel with silver nanoparticles to prolong the shelf life of Fior di Latte cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, A.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S. preparation of polystyrene nanocomposites based on silver nanoparticles using marine bacterium for packaging. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2013, 52, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.S.; Gonzaga, V.A.M.; Poli, A.L.; Schmitt, C.C. Photochemical synthesis of silver nanoparticles on chitosans/montmorillonite nanocomposite films and antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 171, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jiang, S.; Jia, W.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Cao, X.; Shen, X.; Yao, Z. Novel silver-modified carboxymethyl chitosan antibacterial membranes using environment-friendly polymers. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, L.R.; Pérezb, L.M.; del, V.; Soazo, M.; Machado, F. Evaluation of the antimicrobial, antioxidant and physicochemical properties of Poly(Vinyl chloride) films containing quercetin and silver nanoparticles. LWT 2019, 101, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Teoh, Y.L.; Ong, K.M.; Rafflisman Zaidi, N.S.; Mah, S.-K. Poly(vinyl) alcohol crosslinked composite packaging film containing gold nanoparticles on shelf life extension of banana. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; El-Sayed, S.M. Chitosan nanocomposite films based on Ag-NP and Au-NP biosynthesis by Bacillus subtilis as packaging materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 69, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Dicastillo, C.L.; Patiño, C.; Galotto, M.J.; Vásquez-Martínez, Y.; Torrent, C.; Alburquenque, D.; Pereira, A.; Escrig, J. Novel hollow titanium dioxide nanospheres with antimicrobial activity against resistant bacteria. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcous, A.; Rasouli, S.; Ardestani, F. Low-density polyethylene films loaded by titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles as a new active packaging system against Escherichia coli O157, H7 in fresh calf minced meat. Packag Technol Sci. 2017, 30, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hu, Q.; Mugambi Mariga, A.; Cao, C.; Yang, W. Effect of nano packaging on preservation quality of Nanjing 9108 rice variety at high temperature and humidity. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beak, S.; Kim, H.; Song, K.B. Characterization of an olive flounder bone gelatin-zinc oxide nanocomposite film and evaluation of ıts potential application in spinach packaging. J Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2643–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hortal, M.; Jordá-Beneyto, M.; Rosa, E.; Lara-Lledo, M.; Lorente, I. ZnO-PLA nanocomposite coated paper for antimicrobial packaging application. LWT 2017, 78, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Arfat, Y.A.; Bher, A.; Mulla, M.; Jacob, H.; Auras, R. Active chicken meat packaging based on polylactide films and bimetallic Ag–Cu nanoparticles and essential oil. J Food Sci. 2018, 83, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cen, C.; Chen, J.; Fu, L. MgO/Carboxymethyl chitosan nanocomposite improves thermal stability, waterproof and antibacterial performance for food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndwandwe, B.K.; Malinga, S.P.; Kayitesi, E.; Dlamini, B.C. Selenium nanoparticles–enhanced potato starch film for active food packaging application. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 57, 6512–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, N.; Das, N. Fabrication and characterization of biodegradable PHBV/SiO2 nanocomposite for thermo-mechanical and antibacterial applications in food packaging. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 14, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerini, D.; Tammaro, L.; Di Benedetto, F.; Vigliotta, G.; Capodieci, L.; Terzi, R.; Rizzo, A. Aluminum-doped zinc oxide coatings on polylactic acid films for antimicrobial food packaging. Thin Solid Film. 2018, 645, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Namratha, K.; Ilyas, S.; Hezam, A.; Mathur, S.; Byrappa, K. Smart fortified PHB-CS biopolymer with ZnO-Ag nanocomposites for enhanced shelf life of food packaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 48309–48320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayana, B.; Turhan, K.N. Gida AmbalajlamasinAnti̇mi̇krobi̇yel MaddeİçerYeni̇lebi̇li̇rFi̇lmler/ Kaplamalar Ve Uygulamalari Edible Films/Coatings Containing Antimicrobial Agent and Their Applications in Food Packaging. Review. 2010, 35, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H.S.; Bang, J.; Kim, H.; Beuchat, L.R.; Cho, S.Y.; Ryu, J.H. Development of an antimicrobial sachet containing encapsulated allyl isothiocyanate to inactivate Escherichia coli O157, H7 on spinach leaves. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012, 159, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrimonti, C.; White, J.C.; Tonetti, S.; Marmiroli, N. Antimicrobial activity of cellulosic pads amended with emulsions of essential oils of oregano, thyme and cinnamon against microorganisms in minced beef meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2019, 305, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.S.; Carvalho, S.G.; Bertoli, L.D.; Villanova, J.C.O.; Pinheiro, P.F.; Dos Santos, D.C.M.; Yoshida, M.I.; De Freitas, J.C.C.; Cipriano, D.F.; Bernardes, P.C. β-Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes with essential oils: Obtention, characterization, antimicrobial activity and potential application for food preservative sachets. Food Res Int. 2019, 119, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppakul, P.; Miltz, J.; Sonneveld, K.; Bigger, S.W. Active packaging technologies with an emphasis on antimicrobial packaging and its applications. J Food Sci. 2003, 68, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, B.; Chu, J.; Zhang, P. Silica in situ enhanced PVA/chitosan biodegradable films for food packages. Carbohydr Polym. 2018, 184, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, S.A.; Singh, J.; Rafiq, S.; Ashraf, U.; Dar, B.N.; Nayik, G.A. A comprehensive review on antimicrobial packaging and its use in food packaging. Curr Nutr Food Sci. 2018, 14, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilon, L.; Spricigo, P.C.; Miranda, M.; De Moura, M.R.; Assis, O.B.G.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Ferreira, M.D. Chitosan nanoparticle coatings reduce microbial growth on fresh-cut apples while not affecting quality attributes. Int J Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabifarkhani, N.; Sharifani, M.; Garmakhany, A.D.; Moghadam, E.G.; Shakeri, A. Effect of nano-composite and thyme oil (tymus vulgaris L) coating on fruit quality of sweet cherry (Takdaneh Cv) during storage period. Food Sci Nutr. 2015, 3, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surwade, S.A.; Chand, K. Antimicrobial food packaging : An overview. European J Biotechnol Biosci. 2017, 2, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Conte, A.; Buonocore, G.G.; Sinigaglia, M.; Lopez, L.C.; Favia, P.; D’Agostino, R.; Del Nobile, M.A. Antimicrobial activity of immobilized lysozyme on plasma-treated polyethylene films. J Food Prot. 2008, 1, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

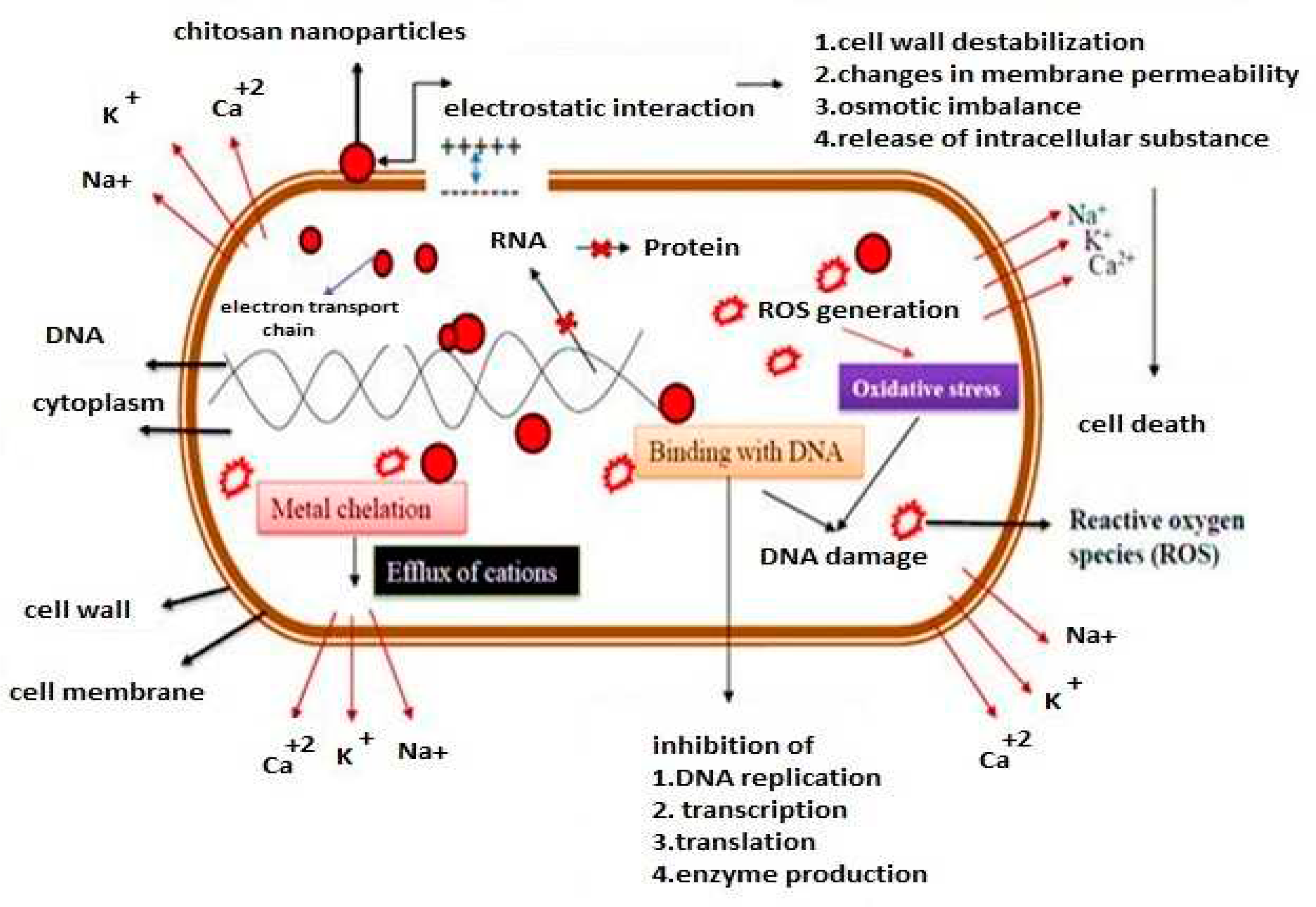

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Kim, K.D.; Chun, S.C. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles: A review. Processes. 2020, 8, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reesha, K.V.; Satyen Kumar, P.; Bindu, J.; Varghese, T.O. Development and characterization of an LDPE/chitosan composite antimicrobial film for chilled fish storage. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015, 79, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Vincent, E. J.; Prevost, N.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.Y. Physico- and bio-activities of nanoscale regenerated cellulose nonwoven immobilized with lysozyme. Mater Sci Eng. 2018, 91, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkoun, M.; Daigle, F.; Heuzey, M.C.; Ajji, A. Mechanism of action of electrospun chitosan-based nanofibers against meat spoilage and pathogenic bacteria. Molecules. 2017, 22, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Bhartiya, P.; Singh, A.; Dutta, P.K. Preparation, physicochemical and biological evaluation of quercetin based chitosan-gelatin film for food packaging. Carbohydr Polym. 2020, 227, 115348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, J.M.F.; Luchese, C.L.; Tessaro, I.C. Impact of acid type for chitosan dissolution on the characteristics and biodegradability of cornstarch/chitosan based films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019, 138, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, T.; Langroodi, A.M. Chitosan coatings incorporated with propolis extract and Zataria multiflora Boiss oil for active packaging of chicken breast meat. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019, 141, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antimicrobial Class | Antimicrobial Agent | Packaging Material | Main Microorganisms | Food | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic acid | Potassium sorbate -vanillin | Chitosan films | mould | Butter cake | [16] |

| Citric acid and chitosan | Fish gelatin/chitosan | Escherichia coli | / | [17] | |

| SodiumbenzoateCitric acid | Poly(vinylalcohol) | S. aureus, E. coli, Candida albicans | / | [18] | |

| Potassium sorbate | Fish collagen- polyvinil alchol | E. coli, S. aureus | / | [19] | |

| Sodium benzoate andpotassium sorbate | Edible active coatings (EACs) | microbial growth (total aerobic counts, molds, yeasts) | Strawberry | [20] | |

| Sorbic acid butylated hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene | polypropylene (PP) films | inhibited gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria growth. | / | [21] | |

| Bacteriocin | Plantaricin BM-1 | PE, LDPE, HDPE | L.monocytogenes | / | [22] |

| Nisin | Chitosan-carboxymethylchitosan | L.monocytogenes | / | [23] | |

| Nisin | PLA | L.monocytogenes | Skim milk and liquid egg white | [24] | |

| Nisin | Starch/halloysite nanocomposite films | L.monocytogenes | Minas frescal cheese | [25] | |

| Nisin and bacteriocin-likesubstance (BLS) P34 | Encapsulated in soybean phosphatidylcholine (PC-1) and PC-1-cholesterol (7, 3) liposomes | L.monocytogenes | Minas frescal cheese | [26] | |

| Bacteriocin KU24 | S.aureus | / | [27] | ||

| Enterocin 416K1 | Low-density polyethylene) (LDPE) film | significant decrease in L.monocytogenes | Frankfurters | [28] | |

| Bacteriocin-likesubstances | Starch | L. monocytogene | Cheese | [29] | |

| Bacteriocin-producerliving bacteria | Poly(ethyleneterephthalate) -polyvinylalcohol (PVOH) | L. monocytogenes | Precooked chicken fillets | [30] | |

| Plantaricin BM-1 | polyethylene terephthalate/polyvinylidene chloride, polypropylene (PPR) film | L.monocytogenes | meat | [31] | |

| Lactocin 705 and lactocin AL705 | Polyethylene-based film | L, plantarum CRL691 L, innocua 7 | / | [32] | |

| Enzymes | Lactoperoxidase | Chitosan | Shewanella putrefaciensPseudomonas fluorescensPsychrotrophs | Rainbow trout | [33] |

| Lysozyme | Nonwovencellulose+ graphene oxide | Micrococcus lysodeikticus | / | [34] | |

| Lysozyme | Polyamide11+halloysitenanotubes | Pseudomonas spp. | Chicken slices | [35] | |

| Lysozyme-chitosan-organic rectorite- sodium alginate | Electrospun Cellulose Acetate | Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus | Pork | [36] | |

| Biopolymers | Chitosan | Acrylonitrile-acrylamidegrafted chitosan | E. coli, S.aureus, P. aeruginosa | Apple andguava | [37] |

| Chitosan | Hydroxyethylcellulose+sodium alginate | E. coli, S. aureus | / | [38] | |

| Chitosan-ZnO hybrid nanoparticles with clove essential oil | Chitosan/pullulan (CS/PL) nanocomposite films | Pseudomonas aeruginosa,S. aureus, E. coli | Checken meat | [39] | |

| Chitosan (Ch) + zinc oxide nanoparticles | Gallic acid films | B. subtilis E. coli | / | [40] | |

| Bacteriophage | Bacteriophage (φIBB-PF7A) | Alginate | P. fluorescens | Chicken fillets | [41] |

| Bacteriophage (vB_EcoMH2W) | Chitosan | E. coli | Tomatoes | [42] | |

| Metal Nanoparticle (NP) | Zinc oxide (ZnO) | Gelatin-chitosan | S. aureus and E. coli | ChickenCheese | [43] |

| Titanyum oxide (TiO2) +Ag | Polylactic acid (PLA) | E. coli,Listeria monocytogenes. | / | [44] | |

| Cupper oxide (CuO) | Carbohydrate biopolymer | Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes | / | [45] | |

| Essansial oil and natural extracts | Cinnamon essential oil | Active paper | Rhizopusstolonifer | Sliced bread | [46] |

| Thyme | Silk fibroin electrospun fibres | Salmonella Typhimurium | chicken meat | [47] | |

| Thymol and eugenol | Biodegradable polymer films: poly (lactic acid), poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and poly (butylene succinate) | E. coli, S. aureus,Bacillus tequilensis, B, subtilis and B. pumilis, | / | [48] | |

| Oregano essential oil (OEO) | Resveratrol (RES) nanoemulsion loaded edible pectin coating | inhibiting microbial growth | fresh pork loin | [49] | |

| Citronella essential oil (CEO) | Chitosan + with ZnO and Ag nanoparticles | S. aureus, E. coliC. albicans | / | [50] | |

| Thymus vulgaris essential oil+ ethanolic extractMediterranean propolis | Polylactic acid (PLA) film | S. aureus andPenicillium spCandida E. coli | / | [51] | |

| Grape fruit seedextract | Agar/alginate/collagenhydrogel films | L. monocytogenes, E coli. | Potatoes | [52] | |

| Gallic acid, chitosan | Gallicacid/graftedchitosan films | / | Agaricusbisporus | [53] | |

| Salicylic acid (SA) | Chitosan films | CS-SA coating inhibited chilling injury and increased the antioxidant enzyme activities | Cucumber | [54] | |

| Ellagic acid | Candelilla wax matrix | significant reduction of C.gloesporioides and extended shlef life | Avocado | [55] | |

| Ferulic acid | Chitosan films | lower total counts, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, | Pork | [56] | |

| Curcumin | Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) films | E. coliL.monocytogenes | / | [57] | |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Polylactic acid and starch films | E. coli and L. inocua | / | [58] | |

| Resveratrol and eugenol | Carboxymethyl cellulose films | L.monocytogenesS. aureus, E. coliS.Enteritidis, | / | [59] | |

| Carvacrol | Cassava starch | E. coli, S.Typhimurium Aeromonas, S. aureus | Pumpkin | [60] | |

| Green tea extract | Chitosan film | L. inocua andE. coli K12 | / | [61] | |

| Grape seed extract | Edible coatings and films based on Chitosan film | L. inocua E. coli K12 | / | [62] | |

| Peonyextracts (Paeonia rockii) dispersed in chitosan | Polysaccharide gels | Antifungal activity and extended shelflife,16 days | Strawberries | [63] | |

| Blueberry(Vaccinium spp.) fruit and leaf extracts | Chitosan coatings | S. aureus,L.monocytogenes S. Typhimurium E. coli, | fresh blueberries | [64] | |

| Tomato plant extract | Edible Chitosan coatings | reduced the mesophyll count during 15 days | Sierra fishfillets | [65] | |

| Others | Sulphurnanoparticles | Chitosan film | L.monocytogenes, E. coli | / | [66] |

| Chlorine dioxide | Polylactic acid (PLA) films | S. aureus, E. coli | / | [5] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).