1. Introduction

Rabies is viral zoonotic but vaccine-preventable disease continue to claims many lives, particularly in sub-Sahara Africa where the disease has become endemic [

1,

2]. It is a highly fatal Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) that affects all mammals [

3] with most human cases from bites from domestic dogs [

4,

5]. The use of vaccines led to the elimination of rabies in most European nations [

2].

The World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Global Alliance for Rabies Control (GARC) have established “United Against Rabies”, as a global collaborative program that is working towards achieving the goal of “zero human rabies deaths by 2030” [

3,

8,

9]. The program to eliminate rabies is managed by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), acting through the Veterinary Services Division (VSD). While the management of high risk and exposed individuals with Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) respectively is performed by the GHS, the control of the disease is through the vaccination of dogs and control of dog populations by the VSD. The relatively higher cost of PEP (

$ 40 -

$ 50) [

9] as compared to the cost of dog vaccines (

$ 5 -

$ 7) in Ghana as of July 2023 makes mass vaccination of dogs an effective and relatively sustainable strategy in rabies prevention and control especially in third world countries [

9].

Rabies, both Africa I and Africa II lineages, is enzootic in Ghana [

1] with the domestic dog being the main vector [

10]. The lack of reliable data and systematic analysis of available data continues to keep rabies as a neglected disease in Ghana [

9,

11]. In most cases, laboratory confirmations were carried out in suspected dog but not in human victims; where diagnosis was based on symptoms, signs, and history of dog bite [

9]. The cessation of the free annual canine vaccination in 1997 has resulted, albeit being underreported, in a sturdy rise in laboratory confirmed rabies cases both in humans and animals. This study provides data on the occurrence of rabies in human and dogs and relates the results to the vaccination status of the dogs. This will help provide relevant data to inform policy and decision on the re-adoption of yearly nationwide mass dog vaccinations in Ghana.

2. Materials and Methods

Study location

The study was conducted at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH) and the Accra Veterinary Laboratory (AVL) in the Veterinary Services Directorate (VSD) in Accra. KBTH is located at Guggisberg Avenue and has, among other facilities, an advanced laboratory unit for histopathology. AVL is located at Ring Road East, La and has, among other facilities, an advanced laboratory for the diagnosis of viruses, pathogens of interest to veterinary and other zoonotic agents.

Study population

All dogs, irrespective of their breed, health, or vaccination status, were considered for this study. Other mammals, including cats, were excluded from the study. This is because most rabid cases in Ghana are of and from dogs.

The minimum sample size required for this study was calculated using

at a 95 % confidence interval, a precision (m) of 0.05 and an estimated prevalence of 91.5 % [

12]. A total of 100 dogs instead of the minimum of 73 samples was used for the study.

Sample collection and procedures

A total of 50 brain samples were obtained from the heads of suspected rabid dogs submitted to AVL for diagnosis and confirmation of rabies. These specimens were collected from September 2020 – December 2020. The hippocampus was extracted, and about 90% of it stored together with the rest of the brain in 10% formalin in leak-proof containers for histopathology. The remaining 10% of the hippocampus were stored in cryovials and kept at (-80℃) for RNA extraction. Saliva samples from 50 quarantined suspected rabid dogs were also stored in cryovials containing 500ul of Viral Transport Medium (VTM) and kept at (-80℃). Detailed information corresponding to each case was recorded.

Sample analysis

All biological samples were analysed for the rabies virus in a Biosafety Security Level three (BSLIII) laboratory at AVL. Histopathology of the brain tissue was conducted at the KBTH.

Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

PCR master mix, containing Primers (RabPyro F, 61.4nmol, RabPyro R1, 66.1nmol, RabPyro R2, 100.8nmol and RabPyro R3, 97.7nmol) from Microsynth company, PCR buffer 5X, dNTPs mix 10mmol, RNase Inhibitor, OneStep RT-PCR enzyme mix and RNase free water, was prepared. The master mix was then vortexed and 22.5ul were aliquoted into 0.2ml PCR tubes. 2.5ul of each of the RNA templates was transfered into each tube.

The samples were placed in the thermal cycler with the following cycling conditions: Pre-PCR (50 ℃, 30 min; 95 ℃, 15 min), 45 Cycles (94 ℃, 30 s; 52 ℃, 30 s; 72 ℃, 40 s) and Holding temperatures (72 ℃, 5 min; 4 ℃, infinity) for the cDNA synthesis. The samples were then stored at - 80 ℃ until they were ready for the gel electrophoresis.

Gel electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis was performed1 using a 1.5% TAE agarose gel (agarose BP160-500, Molecular Biology Grade; Low EEO/Multipurpose, Fisher Scientific: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Belgium) stained with ethidium bromide (Japan and Gel Red Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (10,000x), USA). The amplicons were visualized under UV transillumination after electrophoresis at 100 volts for 30 minutes with a 100bp DNA ladder as the molecular weight marker (BioLabs, New England). The software Logger Pro 3.16.1 Demo was used to determine the migration and fragment sizes of each sample.

Histopathology

The study adopted a blind evaluation [

13] in the histologic examinations where the statuses (suspected positivity/negativity) of the brain tissues were not disclosed to the pathologists. Each tissue was prepared in a duplicate with one slide stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and the other stained Golgi silver nitrate stain. The negative and positive cases were made based on the observation of Negri bodies on H &E stains and distortion in the axons and ganglions in the pyramidal neurons on Golgi silver nitrate stains.

3. Results

Positivity

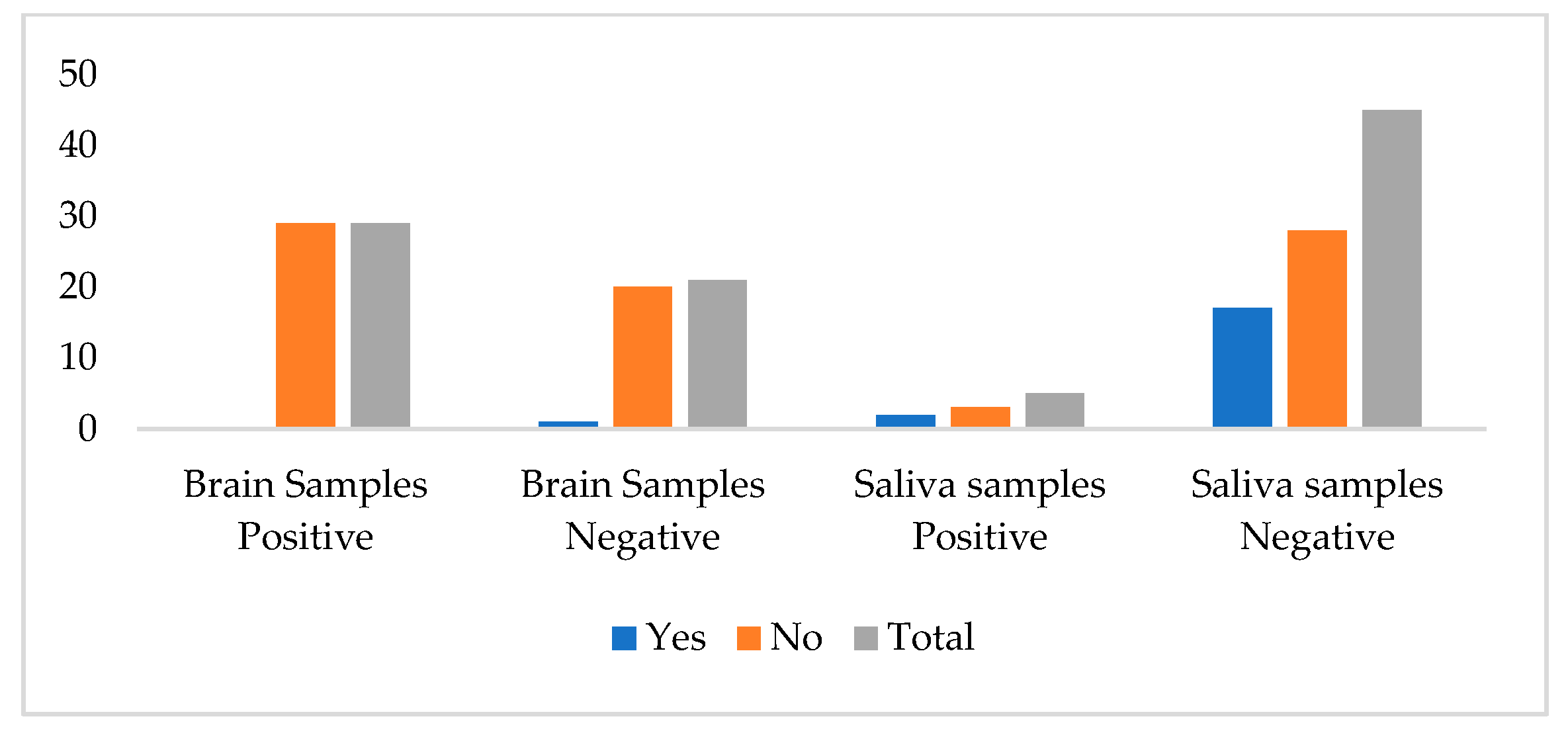

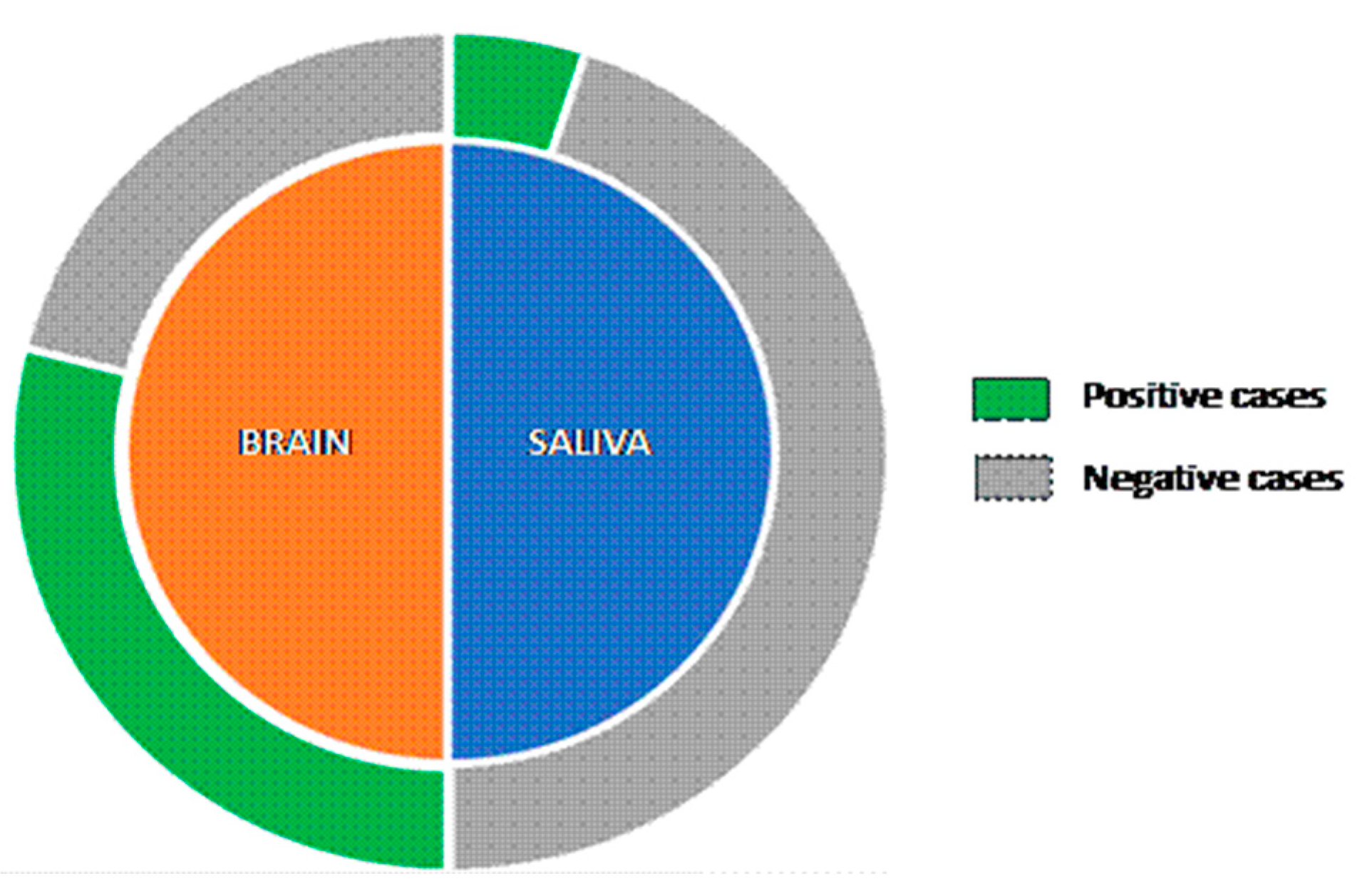

An overall RABV positivity of 34 % was observed in all samples (

Figure 1). Sample specific prevalence revealed a 58 % and 10 % positivity for brain and saliva samples respectively (

Figure 2). All dogs that tested positive for rabies after the examination of their saliva were euthanised.

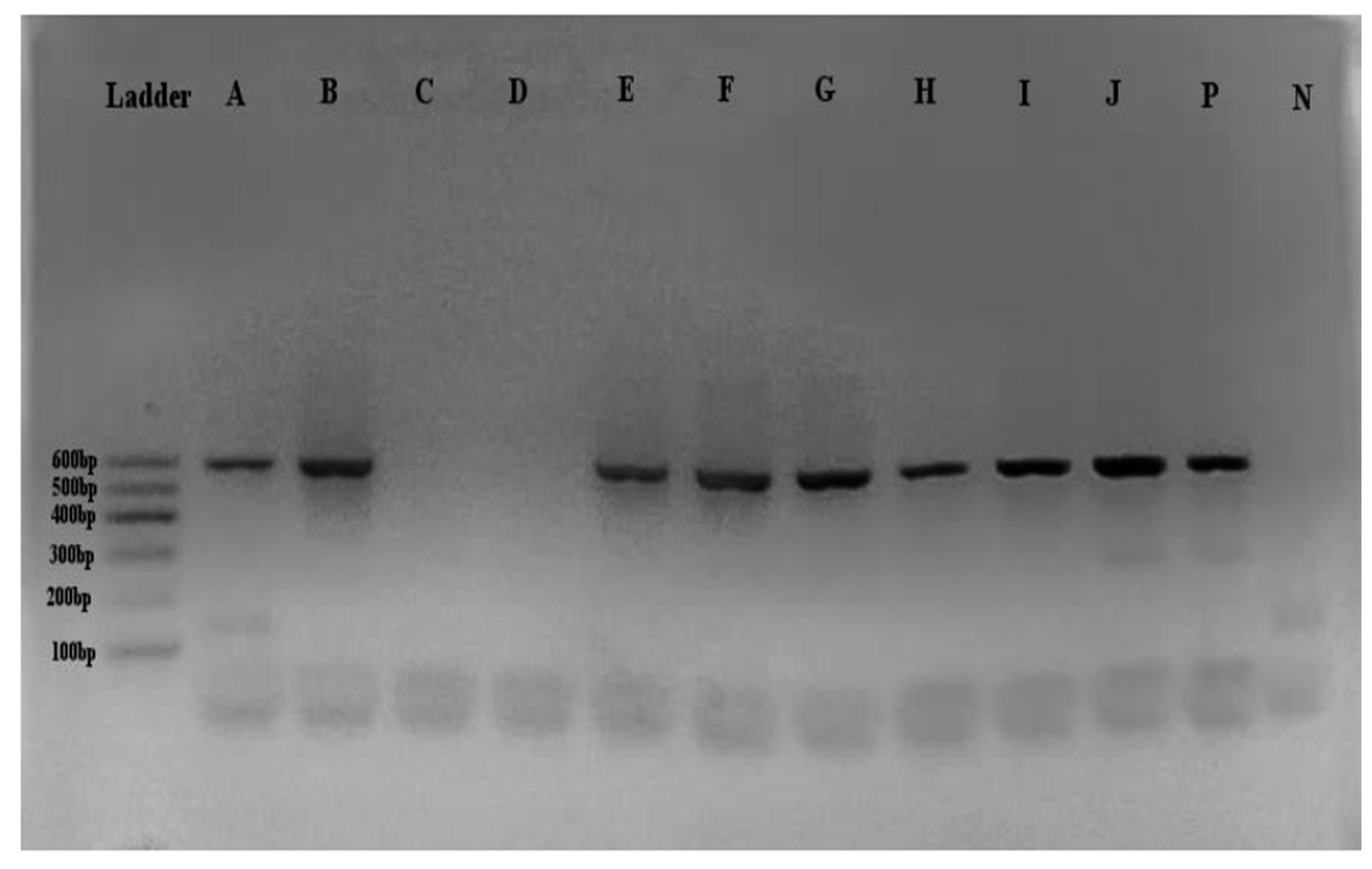

Positive samples showed a 600bp band on gel electrophoresis. There was a significant association between DNA migration to DNA fragment in the brain (p =0.0001) and saliva samples (p = 0.001).

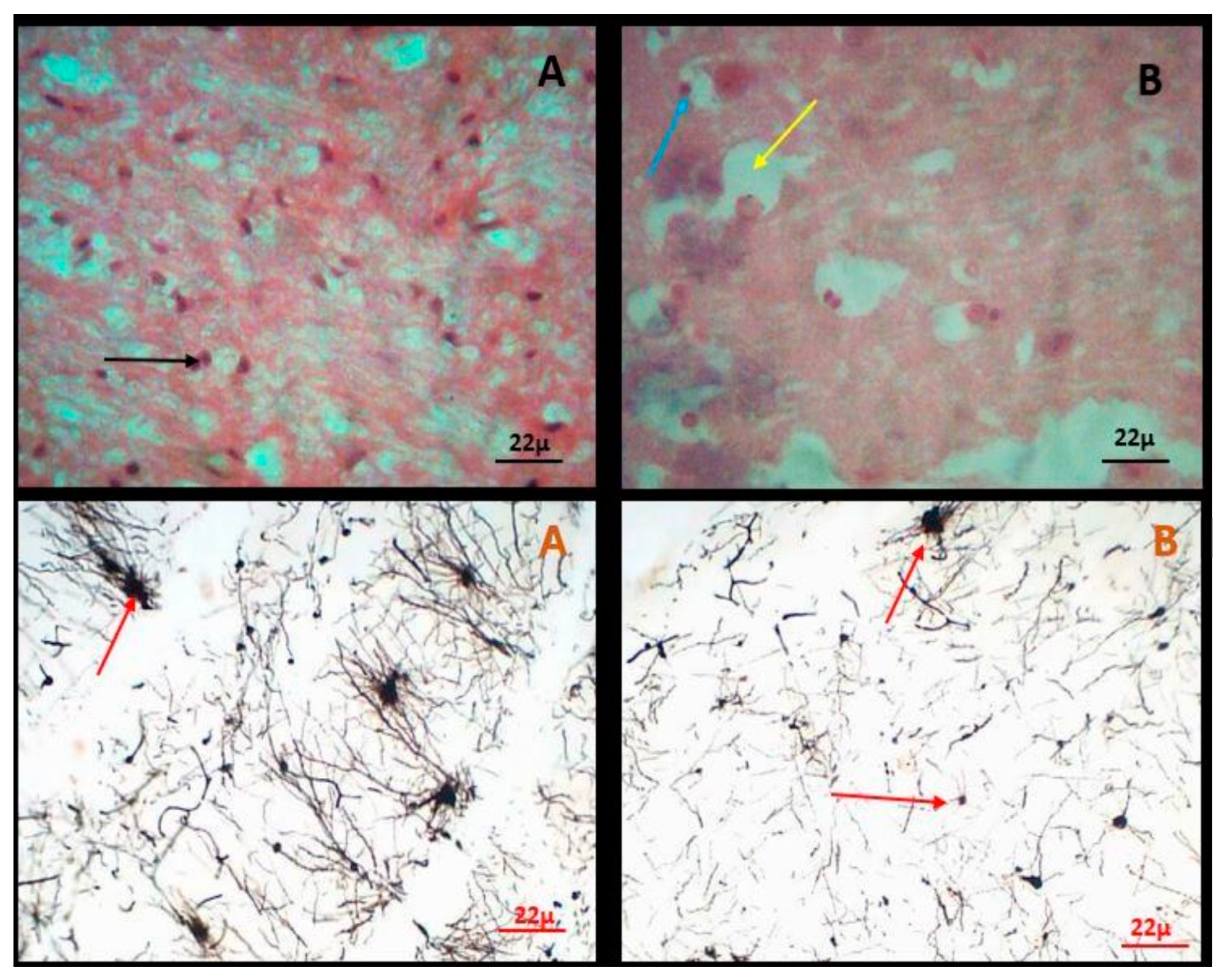

All brain samples that tested positive to RABV (visualized on the gel after RT-PCR) also tested positive after histopathological observations. That is, 58 % of the hippocampus tissues were positive. A sample was considered positive if Negri bodies and distortion of the axons and dendrites of the pyramidal neurons were observed in the brain tissue after staining with H&E and Golgi silver nitrate stain respectively.

Figure 3.

Ethidium bromide-stained gel after cDNA synthesis of RABV using PCR. [A-J] Sample, [P] positive control, [N] Non-Template Control (NTC) of RNAse free water. The products A-J obtained after cDNA synthesis clearly showed a fragment size of 600bp.

Figure 3.

Ethidium bromide-stained gel after cDNA synthesis of RABV using PCR. [A-J] Sample, [P] positive control, [N] Non-Template Control (NTC) of RNAse free water. The products A-J obtained after cDNA synthesis clearly showed a fragment size of 600bp.

Figure 4.

Brain histomorphology in healthy and suspected rabid dogs. [A] is an H&E stain section of intact neurons (arrow) at the cerebral cortex from a healthy dog. [B] is an H&E stain section from a rabid dog showing neuronal necrosis (yellow arrow) and dense eosinophilic Negri bodies in the cerebral cortex (blue arrow). [A1] is a Golgi silver nitrate stain from a healthy dog showing aggregation of cell bodies of intact pyramidal neurons (red arrow). [B1] is a Golgi silver-nitrate stain from a rabid dog showing distortions of cell bodies in pyramidal neurons (red arrows).

Figure 4.

Brain histomorphology in healthy and suspected rabid dogs. [A] is an H&E stain section of intact neurons (arrow) at the cerebral cortex from a healthy dog. [B] is an H&E stain section from a rabid dog showing neuronal necrosis (yellow arrow) and dense eosinophilic Negri bodies in the cerebral cortex (blue arrow). [A1] is a Golgi silver nitrate stain from a healthy dog showing aggregation of cell bodies of intact pyramidal neurons (red arrow). [B1] is a Golgi silver-nitrate stain from a rabid dog showing distortions of cell bodies in pyramidal neurons (red arrows).

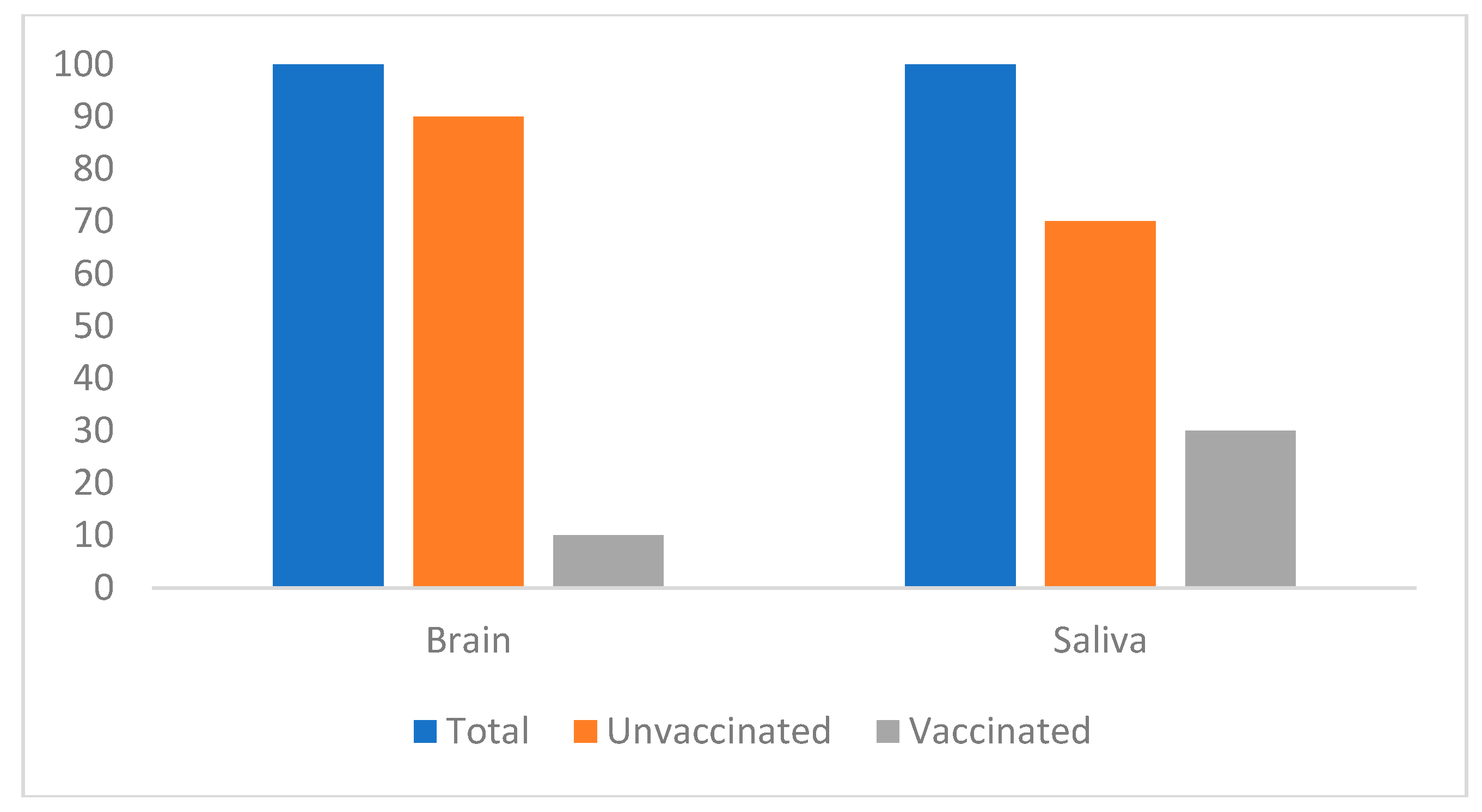

Only 2% of all dogs were vaccinated and positive for rabies while 32 % of the samples were unvaccinated and positive for rabies. In terms of the type of samples, all brain tissues positive for rabies were from unvaccinated dogs. 4 % and 6 % of the saliva samples positive for rabies were from vaccinated and unvaccinated dogs respectively.

In all, 56.7 % (17/30) of all dogs that were attacked by stray dogs tested positive for rabies. One of the dogs that tested positive for rabies had been vaccinated 5 weeks after it was bitten by a stray dog. Also, five dogs (from the brain samples) that tested positive for rabies had bitten seven humans before the dogs were killed.

Figure 5.

Sample specific positivity with respect to vaccination status.

Figure 5.

Sample specific positivity with respect to vaccination status.

4. Discussion

The case positivity for the study was 34 %. Varied positivity rates have been reported all over the country. These include 91.4 % and 83.3 % in Cape Coast and Ledzokuku Krowor from 2005 to 2011 [

12], 91.5 % in Greater Accra Region between 2006 and 2011 [

14], about 17.6 % in 2014 and 3.3 % in 2016 in Techiman [

15] and 2.1 % in dogs slaughtered for meat in Ghana in 2021 [

16]. The diverse range of positive shows the enzootic nature of the disease in Ghana.

The observed positivity rate is also an indication of the ability of veterinarians in Ghana to correctly diagnose rabies. Clinical diagnosis is heavily dependent on the observed signs. Given the endemicity of rabies in Ghana and that none of the clinicians performed a rapid test prior to recommendation of euthanasia, mandatory four months quarantine period or laboratory test, the value realised is encouraging. That, more than 50 % of the brain samples and 10 % of saliva samples tested positive give credence to this position. It shows the precautions with which dogs are recommended for euthanasia by veterinarians in Ghana. That notwithstanding, at most 42 % (21/50 of brain samples) of dogs were wrongly diagnosed as rabid and euthanized emphasizing the need for an enhanced access to prompt rabies diagnosis in Ghana. For instance, rapid test kits can be used as a second layer of precaution in the diagnosis of canine rabies and the decision to euthanise suspected rabid dogs.

About 10% of rabies vaccine naïve dogs are incapable of mounting adequate immunity after receiving primary anti-rabies vaccination [

2]. This is a major cause of vaccine failure. Other causes of vaccine failure include improper maintenance of cold chain and administration of the vaccine at the wrong time including after exposure to the virus. Therefore, the proportion of dogs that tested positive for rabies that were vaccinated (5.9 %: n=2/34) in this study was ideal. While the failure of the vaccine in one of the cases can be attributed to the wrong time in administering the vaccine, the other case can be safely considered as a result of the inability of the dog to mount adequate immunity prior to exposure of the RABV. Regardless, veterinarians are encouraged to ensure proper maintenance of cold chain facilities and timing in administering the anti-rabies vaccines. Another suggested alternative to ensure the elimination of vaccine failure is the adoption of repeated vaccination [

2]. That is, instead of giving a single dose at 3 months and repeating yearly for puppies, veterinarians can consider two separate doses at 10 weeks and 12 weeks followed by yearly doses. The same approach can be considered for rabies vaccine naïve adult dogs. This method can especially be adopted in situations where the client can afford or there are ways of checking the rabies titre after administration of the first dose.

The major risk factors include absence of vaccination, increased dog bite cases [

17] or exposure to stray dogs. Vaccination of dogs has been suggested to be a major intervention that ensures the elimination of RABV. However, since the truncation of the annual free anti-rabies vaccination of dogs by the government of Ghana, the vaccination coverage in the country has been progressively decreasing to less than 40 % [

12,

14,

15]. This might be the situation of vaccination of dogs in Ghana against RABV. Ironically, there is evidence to suggest an appreciably higher knowledge about rabies which does not translate into vaccination [

18]. Therefore, that a third of the samples were vaccinated was expected. However, this is far below the estimated 70 % dog vaccination needed to achieve elimination of rabies in most areas including Ghana [

8]. That the vaccination coverage bubbles around 25 % in most areas in Ghana questions the ability of the country to achieve the ‘zero by 30’ goal.

The exposure of dogs and people to stray animals, usually either unvaccinated or with unknown vaccination statuses, is one main route of transmission of the lyssavirus [

14]. That more than half of the third of dogs that got exposed to stray dogs tested positive for rabies is a confirmation of this fact. The reports on rabid dogs biting people, while they were not investigated is suggestive of the dangers of rabies in humans. It has been established that it is common for rabid dogs to attack mostly youthful males [

5,

14,

15] and their owners. That is, people close to the dog or in the community are the ones likely to be bitten by a rabid dog. It is therefore imperative to ensure all domesticated and some stray/community dogs be vaccinated, and the population of stray/community dogs controlled. The effectiveness of the latter approach has been explored [

12].

The one health approach provides a palpable way to ‘achieving zero by 30’ [

8,

19]. It will involve the empowering of both the VSD and GHS in handling RABV both in animals and humans respectively. This should be backed by stakeholders at both agencies, non-governmental and governmental organisations [

5]. For instance, the reinstitution of the annual free anti-rabies campaigns should be considered a national policy. Furthermore, PEP must be made available for exposed individuals or at-risk individuals [

15] including veterinarians, hunters, pet owners and breeders. They should also introduce systems that ensure compliance to receiving of all 5 doses of PEP [

17] being used in Ghana. Additionally, advancement in surveillance [

2,

14], being it active process or passive [

20], can be useful in the control and elimination of rabies. That is, current technologies and reporting systems can be used in the reportage of suspected and confirmed cases of both human and animal rabies. An increase in education of the public [

5], veterinarians and physicians [

19] on rabies, vaccinations and how to approach stray or community dogs can be performed. Finally, while control of stray dog population can be achieved by mass euthanasia, increasing awareness of animal welfare and rights suggests this method might not be appropriate; inhumane and unethical [l7]. Instead, other methods such as neutering and/or mass vaccination of stray/community dogs can better control the population of these dogs and reduce the odds of them being vectors of rabies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O. and D.A.; methodology, T.O.; formal analysis, R.K.A.; investigation, T.O, D.A, P.T.A, D.B.; resources, T.O.; data curation, R.K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T. O, D.A and R.K.A.; writing—review and editing, B.E, W.T, S.A.M.J, R.K.A and T.O.; visualization, R.K.A.; supervision, T.O, G.B.D; project administration, T.O, G.B.D; funding acquisition, T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by the Accra Veterinary Laboratory.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval (ECC-20170085) for this cross-sectional study was granted by the Baldwin University College Ethical Committee on September 14, 2020. The brain tissues and saliva swabs were collected at Accra Veterinary Laboratory (AVL). Additional written and verbal consents were obtained from pet owners.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all owners of the dogs involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [T.O; RKA], upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eze, U.U.; et al. Molecular detection of rabies lyssaviruses from dogs in southeastern Nigeria: Evidence of transboundary transmission of rabies in west Africa. Viruses 2020, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; et al. Rabies – Epidemiology, pathogenesis, public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control: A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2017, 37, 212–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, K.; et al. Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, A.; et al. The status of rabies in Ethiopia: A retrospective record review. Ethiop. J. Heal. Dev. 2010, 24, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngugi, J.N.; Maza, A.K.; Omolo, O.J.; Obonyo, M. Epidemiology and surveillance of human animal-bite injuries and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis, in selected counties in Kenya, 2011-2016. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, G. Historical note. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hiby, E.; Tasker, L. Qualitative Evaluation of the Five-Year ‘Red Collar’ Campaign to End Inhumane Culling of Dogs as a Method of Rabies Control. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrheim, D.N.; Blumberg, L. Rabies-what is necessary to achieve ‘zero by 30’? Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 111, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, B.Y.; et al. Dog bites and rabies in the Eastern Region of Ghana in 2013-2015: A call for a one-health approach. J. Trop. Med. 2018, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayman, D.T.S.; et al. Evolutionary history of rabies in Ghana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.C.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of canine vaccination to prevent human rabies in rural Tanzania. NIH 2014, 160, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suu-Ire, R.D.; et al. Socio-demography, and rabies situation in the Cape Coast and Ledzokuku-Krowor Municipalities of Ghana. Pan African Med. J. One Heal. 2020, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, M.A. How Valuable is Blind Evaluation in Histopathologic Examinations in Conjunction with Animal Toxicity Studies? Toxicol. Pathol. 1979, 7, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilary Lopes, P. Canine Rabies Outbreaks, Vaccination Coverage, and Transmission in Humans: Greater Accra Region, Ghana- A Retrospective Study-2006-2011. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punguyire, D.T.; Osei-Tutu, A., Aleser; Letsa, T. Level and pattern of human rabies and dog bites in techiman municipality in the middle belt of Ghana: A six-year retrospective records review. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasiame, W.; et al. Rabies virus in slaughtered dogs for meat consumption in Ghana: A potential risk for rabies transmission. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e71–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodki, P.; Katikar, M.; Kulkarni, P. Dog bite and antirabies vaccination: What the anaesthesiologist needs to know. Indian J. Anaesth. 2021, 65, 632–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awuni, B.; et al. Dog Owners’ Knowledge about Rabies and Other Factors That Influence Canine Anti-Rabies Vaccination in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyasulu, P.S.; et al. Rabies mortality and morbidity associated with animal bites in Africa: A case for integrated rabies disease surveillance, prevention, and control: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.A. Molecular Method to Diagnosis of some Strongylide Nematode of goats in Nyala Area South Darfur State- Sudan. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2017, 10, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).