1. Introduction

Rabies is a neglected zoonotic and fatal disease of warm-blooded vertebrates including humans. The disease (rabies) remains the most significant public and veterinary health problem considering that at least 59 000 humans succumb to the disease annually particularly in the resource-limited developing countries of Asia and Africa (14). The causative agent of the disease is a member of the Lyssavirus genus, currently composed of 17 confirmed viral species (41). The prototype species is Lyssavirus rabies, and the rest are known as rabies-related viruses. Within the genus, there are two unclassified lyssaviruses, the Kotalahti bat lyssavirus (KBLV) isolated from a Brandt’s bat (Myotis brandtii) in Finland (29) and Matlo bat lyssavirus from a Natal long-fingered bat (Miniopterus natalensis) (5), and both await ratification by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). All known lyssaviruses have been isolated from bat species except MOKV and IKOV, a once off isolation from an African civet (Civettictis civetta) in Tanzania (1, 23). There are currently six documented Lyssavirus species identified and confirmed from terrestrial and chiropteran host species in Africa and these include the classical Lyssavirus rabies (RABV), Lyssavirus lagos (LBV), Lyssavirus mokola (MOKV), Lyssavirus duvenhage (DUVV), Lyssavirus shimoni (SHIBV) and Lyssavirus ikoma (IKOV) (41).

Rabies virus is distributed globally with the exception of some nation islands such as New Zealand, Marshal Islands and/or Papua New Guinea (42). The aetiologic agent of this fatal zoonotic disease is a highly neurotropic virus that has a wide host range including terrestrial mammals and several bat species (1). In southern Africa, classical RABV occurs as two distinct variants maintained in Carnivora and Herpestidae families, and these are referred to as the canid and mongoose RABV biotypes respectively (19, 28, 40). The canid RABV biotype is maintained and transmitted primarily by domestic (dogs) and wildlife carnivore species such as black-backed jackal species (Canis mesomelas), bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis) and aardwolf (Proteles cristatus), whereas the mongoose RABV biotype is maintained and transmitted by members of the Herpestidae family, especially the yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata). The mongoose rabies biotype comprises 5 phylogenetic groups associated with specific geographic areas in Zimbabwe and South Africa (28, 38), with the dominant one overlying the highveld plateau of the Free State province in South Africa. Molecular clock analysis estimated the mongoose RABV variant to be approximately 200 years old, and the estimation agrees with historical description of rabies in South African mongoose populations dating back to the early 1800s (38). Apart from the maintenance host species, canid, and mongoose RABV infections are reported in several domestic and wildlife species, with the animal species serving as dead-end hosts (30, 33).

The Lyssavirus mokola (MOKV) was first isolated in the late 1960s from organ pools of shrews (Crocidura flavescens manni) in the Mokola forest in Nigeria (17, 36). Thereafter, two additional cases were reported from two girls, a 3.5-year-old in 1968, and a 6-year-old in 1971, both from Nigeria (9, 10). In both these MOKV human cases, the clinical symptoms were atypical for classical Lyssavirus rabies infection (10). These are the only known MOKV infections associated with humans in lyssavirus history. Further MOKV isolations were made from a shrew (Crocidura sp.) in 1978, Cameroun (20), from a rodent (Lophuromys sikapusi) in 1981, Central African Republic (35) and Ethiopia in 1989 from a cat (Feline catus) (25). In Zimbabwe, the MOKV isolations were made between 1981 and 1984 in the south-west regions of the country from 6 cats and 1 dog previously vaccinated against rabies (11, 12) and later in 1993 from a domestic cat (3). In South Africa, MOKV was first isolated in 1970 from a domestic cat (vaccinated) in KwaZulu Natal (KZN) province (26) and subsequent isolations were from the KZN (n=7), Eastern Cape (EC) (n=5) as well as from the Mpumalanga (MP) (n=2) Provinces (6, 27, 31, 32, 39). The majority of MOKVs in South Africa were recovered from domestic cats with the exception of a single case in a domestic dog from MP Province. To date, all MOKV infections have been reported from the African continent, which might suggest that this is a lyssavirus unique to the continent. However, little is known about the epidemiology of this African lyssavirus despite that there are at least 30 confirmed MOKV isolations, the majority originating from southern Africa. Furthermore, the problem of MOKV ecology is compounded by an unknown reservoir host species and limited surveillance throughout the African continent, as most lyssaviruses confirmed during rabies diagnostics are never further characterized into viral species.

Globally, the occurrence of rabies in domestic cats (Felis catus) is less commonly reported than the domesticated dog (13). Currently there is no evidence to indicate that domestic cats and African wild cats (Felis lybica) are involved as natural host species of lyssaviruses in South Africa or elsewhere and only serve as dead-end or incidental hosts. The current rabies vaccines do not confer protection against MOKV infection as shown by incidental evidence of the fatal infections of domestic cats that were previously vaccinated against RABV (12, 27, 31, 32, 39). It is plausible that with frequent contact between domestic cats and their respective owners may pose a potential risk of infection to humans. In this manuscript, we report on a retrospective molecular characterization of lyssaviruses recovered from domestic and African wild cats leading to the identification of a new MOKV, the first one to be reported from Eswatini.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses

A cohort of 51 lyssaviruses obtained from domestic and African wild cats and confirmed to be lyssavirus positive between 2010 and 2020 were selected from the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) rabies reference laboratory repository of the Agricultural Research Council-Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute (ARC-OVI) (Pretoria, South Africa) [

7]. The variety of suspected rabies cases were submitted by state veterinarians to the diagnostic laboratory for rabies confirmation as part of the national rabies surveillance programme. The epidemiological information of the specimens is shown in

Table S1.

2.2. Total RNA extraction, RT-PCR, and sequencing

Total viral RNAs were extracted from the original brain infected tissues using Tri-Reagent (Sigma Aldrich, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was stored at -80oC until required. A reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using the 001Lys (annealing at position 1-14 based on the Pasteur Virus genome sequence) and 550B (annealing at position 647-666) primer set targeting the partial nucleoprotein (N) gene of the viral genome (22). In brief, for the cDNA synthesis of the partial N gene, 5 µg of total RNA and 20 pmol of the forward primer (001Lys) were incubated at 70°C for 5 min. The reaction mixture was immediately cooled on ice and the RNA was reverse transcribed at 50°C for 60 min in a 20 μL-volume containing 200 U Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA), 1X First-strand buffer, 10 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) (Invitrogen, USA) and 40 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega, USA). The reaction mixture was deactivated at 85oC for 5 min. Thereafter, polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in a total volume of 50 μL containing 1X PCR reaction buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM of each dNTP, 5 μL of cDNA, 1.25 U of Takara Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Japan) and 40 pmol of each of the forward and reverse primers (Inqaba Biotech, Pretoria, South Africa) and amplified as previously described (22). The PCR products were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels and subsequently purified using the PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified PCR amplicons were sequenced using both the 001Lys and 550B primers as in the PCR reactions with the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 sequencing reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) on an ABI 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA) at Inqaba Biotech (Hatfield, Pretoria, South Africa).

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

The nucleotide sequences were edited, and consensus sequences assembled using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version X (MEGA X) (37). The edited nucleotide sequences of the partial N gene were aligned using ClustalW algorithm of MEGA X and the phylogenetic trees reconstructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (34). The topology of the reconstructed phylogenetic tree was validated with a 1000 bootstrap replicates (15) and 70% was considered as the cut-off value supporting a phylogenetic grouping.

3. Results

All the selected viruses were successfully amplified and yielded an expected amplicon of approximately 680 bp in size (data not shown). The partial N-gene nucleotide sequences of the 51 samples were established and after the analyses, a lyssavirus sample (467/11) was confirmed to be a Lyssavirus mokola (MOKV) (

Table S1). Given this new identification, all known and previously characterized MOKV isolates were included for additional and more comprehensive phylogenetic analyses (

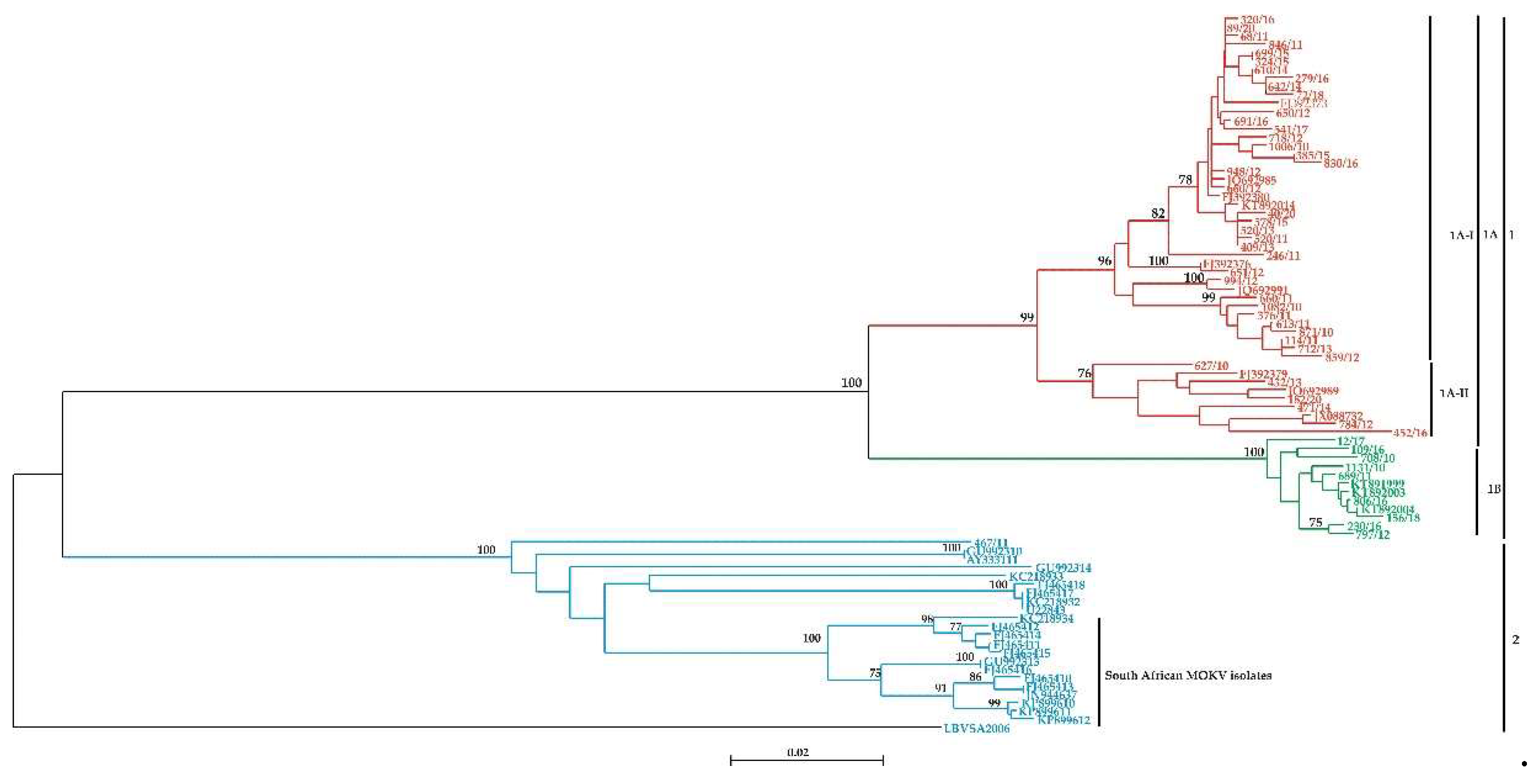

Table S2). The phylogenetic analysis revealed two distinct clusters 1 and 2, supported by a bootstrap value of 100% (

Figure 1). The results further revealed that the viral isolates from cluster 1 belonged to Lyssavirus rabies (RABV), whilst viral isolates in cluster 2 all belonged to Lyssavirus mokola (MOKV) (

Figure 1). Cluster 1 could be further subdivided into two sub-clusters, shown as 1A and 1B, with bootstrap value of 100% (

Figure 1). It was found that the viral isolates in sub-cluster 1A belong to mongoose RABV variant whereas viral isolates from sub-cluster 1B belongs to the canid RABV variant. Sub-cluster 1A could be further delineated into 2 subgroups 1A (I and II) with bootstrap values of 99% (

Figure 1). Sub-cluster 1A-I consists of viral isolates exclusively from the Free State and North-West, Mpumalanga and Northern Cape Provinces whereas subcluster 1A-II consists of viral isolates (n=9) from the Free State and Northern Cape Provinces respectively (

Figure 1). Interestingly, viral isolates within the subgrouping 1A-I clustered according to their geographic locations of the Free State and North-West Provinces with a bootstrap of 78% respectively (TableS1). The data revealed that viral isolates in sub-cluster 1A were very closely related, with a 96% nucleotide sequence similarity, whereas sub-cluster 1B had 99% nucleotide sequence identity. In contrast, the data showed that viral isolates in sub-clusters 1A and 1B had 87% nucleotide sequence identity suggesting that the two clusters belong to distinct RABV variants (

Figure 1).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the newly identified MOKV isolate (467/11) did not cluster with any of the previously identified MOKV lineages (

Figure 1) but is part of a distinct and independent lineage. The phylogenetic data further demonstrated that MOKV isolates from South Africa were part of a compact geographic cluster, statistically supported by a bootstrap value of 100% (

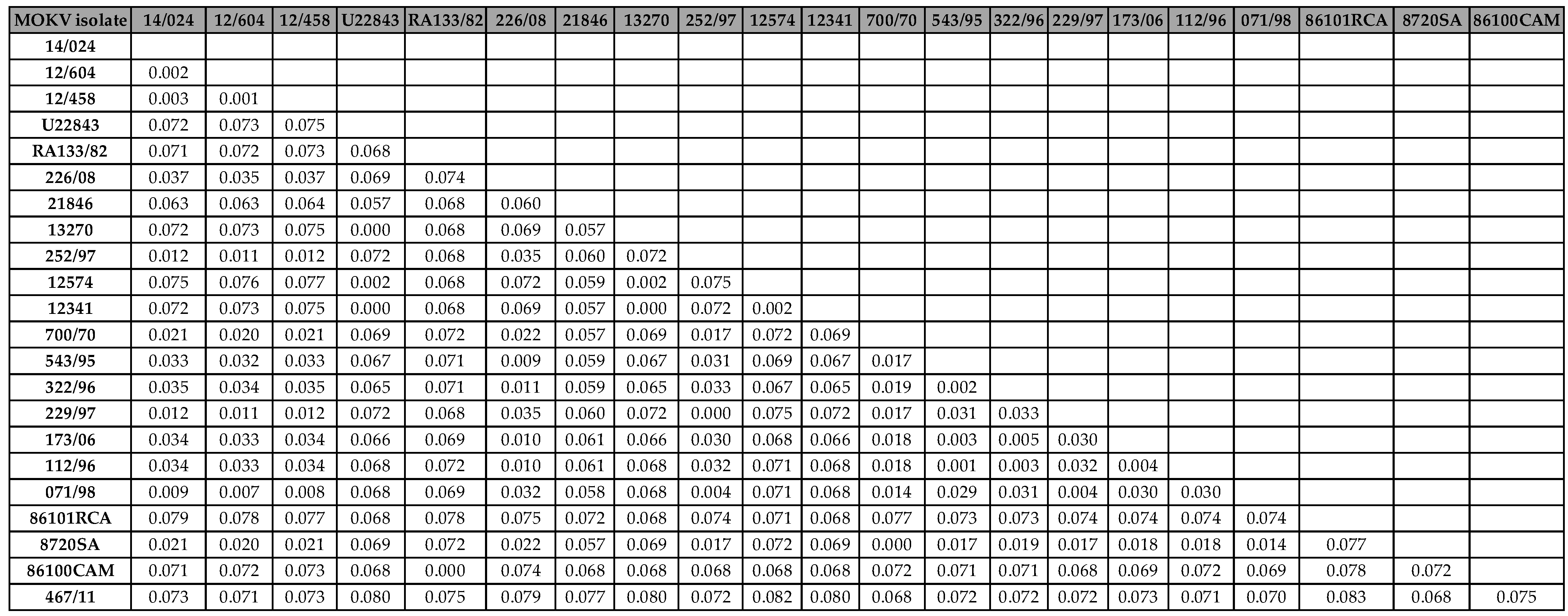

Figure 1). Furthermore, the South African MOKV isolates conformed to two different sub-clusters with a strong bootstrap support value of 100% demonstrating a strong geographical determinant of the isolates from KwaZulu Natal (KZN) and Eastern Cape (EC) Provinces. The pairwise (P) distance comparisons between different MOKV isolates were performed on the highly conserved N gene region under study and the pairwise matrix is shown (

Table 1). The nucleotide sequence divergence values between the recently identified MOKV isolate from the Kingdom of Eswatini (467/11) and the historical Mokola viruses ranged from 6.8% and 8.3% (91.7% and 93.2% nucleotide sequence identity), with the highest divergence value of 8.3% observed between 467/11 (Eswatini) and 86101RCA (Central African Republican) (

Table 1). The nucleotide sequence divergence between MOKV Eswatini and MOKV isolates from South Africa was 7.2% and 8.1% with Zimbabwean MOKV isolates on average (

Table 1). Further, the nucleotide difference with Cameroon and Ethiopia isolates was 7.5% on average respectively. It was apparent that the MOKV from the Kingdom of Eswatini was more closely related to the isolates from South Africa with 93% sequence similarity on average than any other isolates (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

Rabies in domestic cats is a potential public health concern given the association of this domestic carnivore with not only Lyssavirus mokola (MOKV) (18) but also with canid and mongoose RABV variants, which are known to be zoonotic in South Africa (13). This is the first study aimed to retrospectively characterize rabies positive cases identified from domestic and African wild cats to understand the involvement of these species in the epidemiology of lyssaviruses in South Africa. A previous study though demonstrated that despite close contact of humans with domestic cats, less than 3% of human rabies cases in the 36-year period were associated with exposure to these animals (13). Interestingly, the study showed that the majority of the cats were infected with Lyssavirus rabies (RABV), i.e., both canid and mongoose RABV variants, as well as a single case of Lyssavirus mokola isolate. These findings suggest the interaction of domestic and wild cats with maintenance hosts for both the canid and mongoose rabies variants in nature. Surprisingly, the RABV isolates included in the phylogenetic analysis indicated that majority of rabies cases in cats were associated with the mongoose RABV variant rather than the canid RABV variant. This could be attributed to several factors suggesting that some of the rabies cases occurred mostly in the farming communities across the country where the mongoose RABV variant is predominant or common. The domestic cats could have been in contact with the natural host species of Lyssavirus mokola outdoors where they probably interact. Similarly, in the United States of America (USA), the number of domestic cat rabies cases are often greatest in the states where raccoon rabies virus (RRV) is endemic (21). With the continued rabies outbreaks in domestic dogs and their close association with the domestic cats thereof, it would be expected that the most rabies cases would be of the canid RABV variant. A similar phenomenon has been reported in the USA were an overwhelming proportion of rabid cats (99%) in the New York State were infected with (RRV) as opposed to a bat rabies variant (4). In contrast to South Africa, canine rabies has been eliminated in the USA, and sylvatic (wildlife) rabies is a significant challenge with cats being the most reported animal for rabies among domestic species (8). The data presented here do not support whether the domestic cats or African wild cats are involved in the rabies epidemiological cycles in South Africa or only serve as dead-end hosts. In other retrospective studies, it was shown that 94% of the viruses isolated from the domestic cats in KwaZulu Natal, were of canid RABV variant, which is the most prevalent variant of RABV in this region of South Africa (6). The RABV sequences determined in this study indicate a continued and persistent rabies epidemiological cycle in domestic dogs and wildlife species, which spill-over to other animal species. Undeniably, the households or communities with indoor/outdoor cats that are not vaccinated are at an increased risk of rabies exposure. This is despite that vaccination of dogs and cats is compulsory in the Republic of South Africa according to the Animal Diseases Act #35 of 1984.

It appears that the Lyssavirus mokola (MOKV) is exclusively endemic to Africa albeit that only 30 sporadic cases have been reported since its discovery more than 50 years ago with the majority of these cases identified from South Africa (6, 18). The single or sporadic cases identified so far could be attributed to the fact that the maintenance host species of MOKV is still unknown and these cases may represent cross-species transmission or spill-over events into the domestic cats or other animal species. The newly identified MOKV case reported here, provides yet further confirmation that MOKV epidemiological cycles are well established on the African continent and underreported. The male cat in question (467/11) apparently resided in Phophanyane Falls, near Piggs Peak (Eswatini) and was referred for treatment for an undisclosed ailment across the border in Mpumalanga province (South Africa). The cat had no vaccination history nor human bite contact, and yet a positive rabies test was confirmed. Therefore, the lack of detection and isolation of rabies-related viruses such as MOKV is testimony to the non-existence of appropriate surveillance tools and limited diagnostic capabilities such as typing of lyssaviruses using monoclonal antibody panels, and/or genetic sequencing, which are crucial in the differentiation of lyssaviruses, in general. Antigenic and genetic typing of lyssaviruses allows us to distinguish trends of disease dissemination and infer source of infection, as antigenic rabies variants are associated with different rabies cycles and species of terrestrial carnivores in the region.

The p-distance analysis data indicated that the new MOKV isolate from the Eswatini displayed a nucleotide sequence variation of 7.2% and 8.1% on average at a nucleotide level with previous characterized isolates from South Africa and Zimbabwe respectively. It appears that overall, all MOKV isolates included for analysis demonstrated a pattern of clustering underpinned by their geographic locality of origin, similar to observations from previous studies (6, 18). The reservoir host of MOKV is still unknown and remains purely speculative, although bat species cannot be ruled out. The cross-species transmission or spillover of MOKV infection into animals such as domestic cats and dogs lead to dead-end infections. Previous studies suggested that the reservoir host for Lyssavirus mokola might be a carnivore species that interacts with the domestic cats, but there is a little or no evidence to support this notion (18, 39). A recent study found a high seropositivity of 87,80% to MOKV from bushveld gerbils (Gerbilliscus leucogaster) rodent, which could suggest a potential rodent reservoir (24), or simply exposure to a pathogen that cross-reacts with Lyssavirus mokola. There is no active surveillance for MOKV on the continent and subsequently the epidemiology of this rabies-related virus remains obscure. Lyssaviruses have a strong association with bats and MOKV and Lyssavirus Ikoma (IKOV) are the two exceptions among all the other members of the genus (41).

This study was able to contribute some insights on the involvement of domestic and wild cats in the rabies epidemiological cycles in South Africa. Human rabies cases associated with domestic cat exposures in South Africa are rare and only less than 3% of human rabies cases in the last 36-years period were recorded (13). Further, the study demonstrated that 37% (n=3) of human rabies cases were associated with the mongoose RABV variant, whereas the majority, 63% (n=5) were due to the canid RABV variant (13). The close association between humans with domestic cats and the lack of protection with the current inactivated vaccines (11, 12, 18) lend support to undertake more research into the epidemiology and ecology aspects of MOKV, as well as the reservoir host species. Cats have a typical characteristic of forming large colonies of feral cats where intense intra and interspecific relationships occur, thus increasing the chances of contact with wild animals infected by the Lyssavirus rabies resulting in transmitting infection it to other members in the colony (2). Therefore, eliminating dog rabies would not completely remove the risk of rabies in domestic cats, since the transmission of mongoose RABV variant has been demonstrated here. Since domestic cats have a keen hunting characteristic, they have a potential to transmit the lyssaviruses to domestic animals such as domestic dogs in regions with low rabies vaccination coverage and due to the proximity to humans, rabies can then be easily transmitted to humans. Therefore, continuous rabies vaccination of domestic cats remains key even after the elimination of dog rabies as the spillover related to a sylvatic rabies cycle will continue to occur.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Number of viral isolates used in the study.; Table S2: Number of Lyssavirus mokola included in the analysis.

Author Contributions

K.T.: processed the samples and reviewed the manuscript. E.N.: conceptualize, formal analysis and writing-original draft preparation, writing-reviewed and editing of the manuscript. B.P.: performed data analysis and writing-reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.K.: provided the test sample and reviewed the manuscript. C.S.: conceptualized the project, project administration, and writing-reviewed and editing of the manuscript, supervision of the student. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Rabies Diagnostic Project (P10000045) of the ARC-OVR and was partly funded by European Virus Archive global (EVAg), a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, grant number 871029.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequence data generated in this study can be found on Genbank.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Christine Lotter and Ms. Debrah Mohale are acknowledged for their technical and administrative support. Dr Antionette van Schalkwyk for critically reviewing the manuscript. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Badrane, H.; Tordo, N. Host Switching in Lyssavirus History from the Chiroptera to the Carnivora Orders. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 8096–8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, P. L. (2007). The human-cat relationship. In: Rochlitz, I. The welfare of cats. Springer, pp. 47-91.

- Bingham, J.; Javangwe, S.; Sabeta, C.T.; Wandeler, A.I.; Nel, L.H. Report of isolations of unusual lyssaviruses (rabies and Mokola virus) identified retrospectively from Zimbabwe. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2001, 72, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunt, S.; Solomon, H.; Brown, K.; Davis, A. Feline and Canine Rabies in New York State, USA. Viruses 2021, 13, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coertse, J.; Grobler, C.S.; Sabeta, C.T.; Seamark, E.C.; Kearney, T.; Paweska, J.T.; Markotter, W. Lyssaviruses in Insectivorous Bats, South Africa, 2003–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 3056–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coertse, J.; Markotter, W.; le Roux, K.; Stewart, D.; Sabeta, C.T.; Nel, L.H. New isolations of the rabies-related Mokola virus from South Africa. BMC Veter- Res. 2016, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.J. , Abelseth, M.K., Atansiu, P. (1996). The fluorescent antibody test. In: Meslin, F.C., Kaplan, M.M., Koprowski, H., editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; pp. 88-95.

- Dyer, J.L.; Yager, P.; Orciari, L.; Greenberg, L.; Wallace, R.; Hanlon, C.A.; Blanton, J.D. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2013. J. Am. Veter- Med Assoc. 2014, 245, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Familusi, J.B.; Moore, D.L. Isolation of a rabies related virus from the cerebrospinal fluid of a child with 'aseptic meningitis'. Afr. J. Med Sci. 1972, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Familusi, J.B. , Osunkoya, B.O., Moore, D.L., Kemp, G.E., Fabiyi, A. (1972). A fatal human infection with Mokola virus. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 21:959-63.

- Foggin, C. Atypical rabies virus in cats and a dog in Zimbabwe. Veter- Rec. 1982, 110, 338–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foggin, C.M. (1988). Rabies and rabies-related viruses in Zimbabwe: Historical, virological, and ecological aspects, PhD thesis. Harare: University of Zimbabwe.

- Grobbelaar, A.A. , Blumberg, L.H., Dermaux-Msimang, V., Le Roux, C.A., Moolla, N., Paweska, J.T. et al. (2020). ‘Human rabies associated with domestic cat exposures in South Africa, 1983–2018’, Journal of the South African Veterinary Association, 91(0), a2036.

- Hampson, K. , Coudeville, L., Lembo, T., Sambo, M., Kieffer, A., Attlan, M., Barrat, J., Blanton, J. D., Briggs, D. J., Cleaveland, S., et al. (2015). Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLOS Neglected Tropical Disease, 9: e0003709.

- Hillis, D.M. , Bull, J.J. (1993). An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Systematic biology, 42(2): 182-192.

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W5–W9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, G.E. , Causey, O.R., Moore, D.L., Odelola, A., Fabiyi, A. (1972). Mokola virus: Further studies on IbAn 27377, a new rabies-related etiological agent of zoonosis in Nigeria. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 21:356-9.

- Markotter, W.; Kgaladi, J.; Nel, L.H.; Marston, D.; Wright, N.; Coertse, J.; Müller, T.F.; Sabeta, C.T.; Fooks, A.R.; Freuling, C.M. Diversity and Epidemiology of Mokola Virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2511. [Google Scholar]

- A King, A.; Meredith, C.D.; Thomson, G.R. Canid and viverrid rabies viruses in South Africa. Onderstepoort J. Veter- Res. 1993, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gonidec, G.; Rickenbach, A.; Robin, Y.; Heme, G. [Isolation of a strain of Mokola virus in Cameroon (author's transl)]. Ann. de Microbiol. 1978, 129, 245–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Monroe, B.P.; Cleaton, J.M.; Orciari, L.A.; Gigante, C.M.; Kirby, J.D.; Chipman, R.B.; Fehlner-Gardiner, C.; Cedillo, V.G.; Petersen, B.W.; et al. Public Veterinary Medicine: Public Health: Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2018. J. Am. Veter- Med Assoc. 2020, 256, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markotter, W.; Kuzmin, I.; Rupprecht, C.; Randles, J.; Sabeta, C.; Wandeler, A.; Nel, L. Isolation of Lagos Bat Virus from Water Mongoose. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1913–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, D.A.; Horton, D.L.; Ngeleja, C.; Hampson, K.; McElhinney, L.M.; Banyard, A.C.; Haydon, D.; Cleaveland, S.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Bigambo, M.; et al. Ikoma lyssavirus, highly divergent novel lyssavirus in an African civet. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, W.C.; Coertse, J.; Kearney, T.; Keith, M.; Swanepoel, L.H.; Markotter, W. Surveillance of the rabies-related lyssavirus, Mokola in non-volant small mammals in South Africa. Onderstepoort J. Veter- Res. 2021, 88, 13–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebatsion, T.; Cox, J.H.; Frost, J.W. Isolation and Characterization of 115 Street Rabies Virus Isolates from Ethiopia by Using Monoclonal Antibodies: Identification of 2 Isolates as Mokola and Lagos Bat Viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 166, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, C.D.; Nel, L.; Von Teichman, B.F. Further isolation of Mokola virus in South Africa. Veter- Rec. 1996, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, L.H. , Jacobs, J., Jafta, J., von Teichman, B., Bingham, J. (2000). New cases of Mokola virus in South Africa. Virus Genes, 20: 103-106.

- Nel, L.; Sabeta, C.; von Teichman, B.; Jaftha, J.; Rupprecht, C.; Bingham, J. Mongoose rabies in southern Africa: a re-evaluation based on molecular epidemiology. Virus Res. 2005, 109, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokireki, T.; Tammiranta, N.; Kokkonen, U.-M.; Kantala, T.; Gadd, T. Tentative novel lyssavirus in a bat in Finland. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoepe, C.E.; Sabeta, C.; Nel, L. The spread of canine rabies into Free State province of South Africa: A molecular epidemiological characterization. Virus Res. 2009, 142, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeta, C.T.; Markotter, W.; Mohale, D.K.; Shumba, W.; Wandeler, A.I.; Nel, L.H. Mokola Virus in Domestic Mammals, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1371–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeta, C.; Blumberg, L.; Miyen, J.; Mohale, D.; Shumba, W.; Wandeler, A. Mokola virus involved in a human contact (South Africa). FEMS Immunol. Med Microbiol. 2010, 58, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeta, C.T.; van Rensburg, D.J.; Phahladira, B.; Mohale, D.; Harrison-White, R.F.; Esterhuyzen, C.; Williams, J.H. Rabies of canid biotype in wild dog (Lycaon pictus) and spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) in Madikwe Game Reserve, South Africa in 2014–2015: Diagnosis, possible origins and implications for control. J. South Afr. Veter- Assoc. 2018, 89, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing evolutionary trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluzzo, J.-F.; Rollin, P.; Dauguet, C.; Digoutte, J.-P.; Georges, A.-J.; Sureau, P. Premier isolement du virus Mokola à partir d'un rongeur (Lophuromys sikapusi). Ann. de l'Institut Pasteur / Virol. 1984, 135, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shope, R.E.; Murphy, F.A.; Harrison, A.K.; Causey, O.R.; Kemp, G.E.; Simpson, D.I.H.; Moore, D.L. Two African Viruses Serologically and Morphologically Related to Rabies Virus. J. Virol. 1970, 6, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, N.; Markotter, W.; Nel, L. Evolutionary history of African mongoose rabies. Virus Res. 2010, 150, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Teichman, B.; De Koker, W.; Bosch, S.; Bishop, G.; Meredith, C.; Bingham, J. Mokola virus infection : description of recent South African cases and a review of the virus epidemiology : case report. J. South Afr. Veter- Assoc. 1998, 69, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Teichman, B.F.; Thomson, G.R.; Meredith, C.D.; Nel, L.H. Molecular epidemiology of rabies virus in South Africa: evidence for two distinct virus groups. J. Gen. Virol. 1995, 76, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, P.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Mushegian, A.R.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dutilh, B.E.; García, M.L.; Hendrickson, R.C.; et al. Recent changes to virus taxonomy ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2022). Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 2429–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Neglected tropical diseases: rabies. https://www.who.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).