1. Introduction

1.1. The Need for a Smart Urban Environment

During the last decade, the citizens’ needs, challenges and lifestyle have been diversifying, transforming and evolving the urban environment. Over the decades, the municipal authorities are faced with increasingly complex problems and challenges, extending to areas such as public transportation and services, health care, the environment, energy, and national, individual, and cyber security. During its transformation phase, resources gradually decreased, its management capacity undermined and the natural resource management mechanisms and action planning and decision-making reshaped [

1,

2].

Urbanization led progressively to the abandonment of rural areas and the accumulation of large numbers of residents in large urban centres. According to the United Nations research, currently the urban population exceeds 3 billion, accumulating over 70% of the world's population in megacities [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] and covering only 2% of the Earth's surface [

9]. This affected the relationship of the citizen and public governance and stress the value of functions and processes aligned with the daily activities of organizations and habitants. The modern urban areas utilized information and communication technologies (ICT) as the appropriate tools for facing emerging challenges.

Advancements and cutting-edge technologies are encountered as a force for change, affecting economically, socially and politically all the components of an urban environment. Particularly, ICT ignited a technological revolution influencing all sectors of the global and urban economy [

10,

11], responding to the emerging needs of urban habitants and significantly affecting the public governance at all levels of policy and management.

While the urban ecosystem is being "digitalized", the role of the municipality and its local authorities could not remain unaffected. The overall management of the services and the available human and financial capital concern horizontally all the sectors. Local Authorities can gradually support decentralized administration, activate citizens and save resources while providing integrated and rapid services.Traditionally, cities operational model is usually characterized by low connectivity and efficiency and the absence of the ability to carry out horizontal innovation between systems. This model is changing, and the upgraded operating model offers high accessibility and degree of interaction between the different sectors and participants [

12]. Thus, the conditions formed lead to the creation of interactive channels, allowing the entry and promotion of innovation from multiple sources. It has acquired a more substantial and active role, leading to: (1) directly and indirectly effects of investments and quality of life, (2) formulation of partnerships and (3) variety of roles depending on its goals and strategy.

Today, a third generation of smart cities is emerging that tries to improve the aforementioned mismatch. Instead of an approach through technological providers (Smart City 1.0), or a model driven by the coexistence of technology and man in the city (Smart City 2.0), a new model of "co-creation" appears, in which society and citizens are co-creators (Smart City 3.0). In "smart city 3.0", the governance, regulations, policies, technological solutions and developments and society – citizens and organizations – interact, exchange data, and actively participate to improve urban initiatives and processes on a daily basis [

13,

14]. Now, the inhabitants play an essential role in the development and operation of the urban ecosystem while given the possibility to use open tools and methods for the overall management of the city.

According to the analysis of the literature, an urban ecosystem is distinguished in three main dimensions (1) technological, (2) institutional and (3) social human [

15]. The impact of ICT in all these dimensions expanded on six main axes: (1) Smart economy, (2) smart mobility, (3) smart environment, (4) smart people, (5) smart living, and (6) smart governance [

16,

17]. Specifically, the field of smart economy can be studied at the global, national, regional or city level. At the urban level, the main structural feature is cities [

18] and this is where the role of a smart city is emerging.

1.2. The Research Axis of the Paper

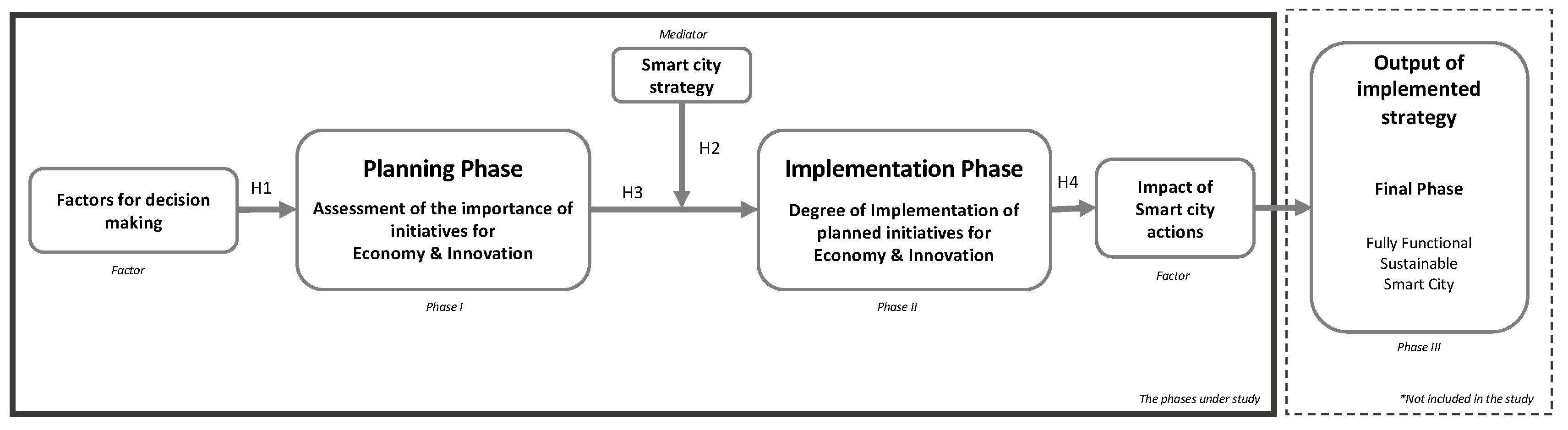

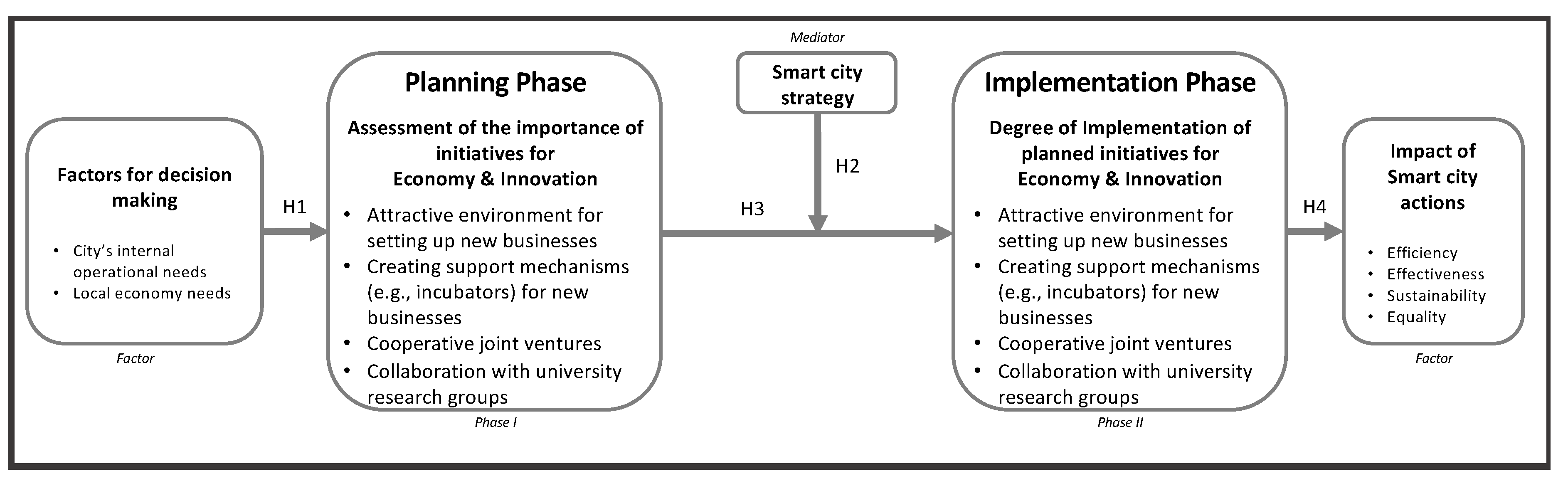

Consequently, the aim of the paper is to study the role of planning a strategy and implementing its actions relating to the economy and innovation in a smart city (

Figure 1). It tries to identify the impact of different factors during the design and execution of a strategy. The factors may relate to the needs of the society and the municipality.

The paper starts with the summary of the theory and the hypotheses supporting the purpose of the research. Then, the method and the dataset used are presented, followed by the results and their discussion. Finally, the paper concludes with the general output of the research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

The development of the urban ecosystem is accompanied by the upgrading of (1) urban infrastructure, (2) the daily functions of citizens, (3) the development of technologies and (4) the evolution of civilization [

19]. However, for there to be substantial growth, the city needs to implement a sustainable strategy through the development of new technologies [

19] and to shape a dynamic urban ecosystem, which encourages the collaboration of different organizations, policy makers, local governments and citizens [

20]. The mechanism for creating business opportunities is multidimensional and complex with continuous interactions, supports the development of a supportive environment and encourages innovative entrepreneurship [

21]. Therefore, the opportunity for companies and citizens to take risks, innovate, offer advanced solutions that are environmentally friendly, contribute to solving social problems and help create local employment opportunities [

22,

23,

24].

At the same time, the use of modern technologies enabled the collection and distribution of data and knowledge to provide efficient and sustainable public services [

20]. By allowing access to data, local governments encourage the formation of innovative businesses with social and economic value [

25]. Given the potential, companies are investing huge resources in smart city initiatives, which promote innovative technologies, support the efficiency of Municipalities and create new business opportunities [

26,

27].

2.1. Innovation in Smart Cities

Innovation has a catalyst role in the development of a smart city. For an urban environment, innovation is the mechanism for economic development and digital transformation. Through innovation, local authorities and actors can deal with emerging urban problems [

28]. By taking advantage of ICT developments, the implementation of plans, ideas and visions is achieved, while improving public functions and the quality of life [

29].

Beyond the development and use of technology, innovation can revolutionize the applied policy and management practices to align with the city’s needs [

30]. Through innovation, an organization can adapt to market changes and technological developments, seize emerging opportunities and successfully endure financial problems, i.e., recessions [

31]. However, the new conditions call on local authorities to differentiate themselves from their established practices and promote innovation in public actions [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Therefore, innovation retains an important role in the economic growth of an urban environment.

2.2. The Economy from the Smart City Point of View

An urban ecosystem can act as a driver for the development of innovation. Meanwhile, another economic factor, competitiveness, is inextricably linked to the development of the country and society [

36]. Based on the literature, the future city's development is directly linked to the ICT funding. Technologies illustrate a catalytic impact for leading the digital transformation of the urban ecosystem and the economic development on a local, national and global level. Therefore, the integration of ICT in the economic activities of city’s private and public entities transform the urban economy into a "smart economy". This transformation includes factors such as competitiveness, entrepreneurship, brands, innovation, productivity, market flexibility work and the integration of the activities of local organizations into the national and global market [

37].

The smart economy is one of the key features of the smart city and is a central element of the economic, social and cultural development of the urban ecosystem [

38]. It is directly linked to the national development. For the purposes of this paper, the smart economy treats ICTs as a driver of growth, which contribute to the characteristics of existing and new economic sectors of an urban area and is connected to characteristics relating to (1) attractive environment for setting up new businesses, (2) creating support mechanisms (i.e., incubators) an incubator for new businesses, (3) cooperative joint ventures, and (4) collaboration with university research groups. Therefore, the smart city economy is considered "smart" and through competition, cooperation and clustering of economic units and activities stimulating innovation.

2.3. Factors Impacting the Decision-Making Process

As the global economy evolves and adapts to the technological progress and the evolution of society, smart economy is intertwined with the development of ICT and smart cities. During the industrial age the development of the economy was based more on the linear connections between industries, such as value chains, a company's physical assets, and metrics such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). On the contrary, the digital age is characterized by networks or sets of sub-networks, fundamental to market rules and mechanisms [

39]. Also, it is distinguished by specialization at individual level, adaptation to mass changes, horizontal exploitation of ICT, the constant exchange of information between different disciplines and actors and the creation of an environment to support innovative ideas [

40].

Through ICT, new businesses are created with: (1) new innovative products, (2) possibility of working from home, (3) smart infrastructure, (4) better access to public documents, (5) improved connectivity of different organizations in public and private sector, (6) ability to work faster and more seamlessly and (7) products/services tailored to their customers' needs [

40]. Therefore, local authorities try via the technological developments to solve critical challenges, to integrate heterogeneous Big Data, strengthen the cognitive level of employees, and increase the possibility of exploiting innovation. All of these, allowing organizations to solve emerging problems [

40].

Therefore, during the planning of actions relating to enhancing the economy and innovation, a municipality needs to focus on the city’s needs.

H1: The city’s needs impact positively and significantly the planning phase of a strategy focusing on the smart economy and innovation.

2.4. Smart City Strategy

In the literature, there is a considerable interest in identifying various resources and factors (i.e., approaches, initiatives, projects, and policy aspects), to exploring and mapping the potentials of smart cities across different urban sectors [

15,

41,

42]. Cities allocate diverse technological, financial, and human resources by implementing "smart" actions that prioritize the city's requirements leading to digital transformation [

14]. Therefore, integrating technological advancements into policy and decision-making processes at an urban level is crucial [

43]. The importance of this integration dwells from the significance of actions (e.g., project, strategy, or isolated actions) to comply with the city's urban planning and policy framework, thus emphasizing the importance of tailor-made strategies beneficial to the urban ecosystem [

44]. Hence, a municipality needs a well-organized smart city strategy oriented on the economy and innovation in order to be able to execute initiatives focusing on creating an attractive environment for setting up new businesses, incubators or other support mechanisms for new businesses, supporting cooperative joint ventures, and helping form collaborations or urban actors with universities and research centres (H2).

H2. The assessment of planning actions in a strategy relating to initiatives focusing on economy and innovation has a significant and positive effect on the degree of implementing relevant actions and projects.

Formulating a smart sustainable city strategy requires policymakers to understand and consider the uncertainties of a municipality's social, financial, and cultural environment and the needs of all interested parties[

41,

45,

46,

47]. These strategies should gradually take into account the city's governance, economy, environmental issues, and stakeholder agendas and include initiatives which support innovation, investment and partnerships between different sectors and stakeholders [

48,

49].

Based on the finding from the literature, municipalities with a well-structured plan for their smart city projects are better positioned to carry out their anticipated initiatives. The impact is noteworthy particularly when the projects encompass e-government, e-services, city planning, education, finance, and resource management [

14]. An analytical and structured framework can work as a guided roadmap for urban planners, enabling effective development of a smart city agenda [

50,

51]. The value of a well-structured strategy is observed when its absence or lack creates significant obstacles to transforming an urban area into a smart one [

52,

53]. Therefore, crafting and implementing tailor-made strategies and personalized approaches in Greek municipalities can stimulate multiple factors that facilitate and support the community's smooth transition to the next era of digital transformation [

14]. An even greater interest is located in the relationship between the existence of a well-organized plan and the implementation phase of anticipated smart city project focusing on the economy and innovation (H3).

H3. The existence of a well-organized strategy affects indirectly positively and significantly the implementation phase of the anticipated smart city projects related to the economy and innovation.

2.5. How Smart Cities Help the Urban Environment

Cities, as functional systems of physical objects and citizens, consume resources and services and offer economic, social, cultural and environmental services to satisfy the needs of their habitants [

54]. The dynamics of cities have greatly permeated all aspects of society and greatly influenced the development of the economy [

55]. They favour creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship and highlight the need to develop an entrepreneurial ecosystem, with an emphasis on the economy and entrepreneurial opportunities [

68].

The economy based exclusively on the traditional form of industry is being transformed into a digital economy, i.e., the smart economy. The smart economy leverages ICT to stimulate innovation through competition, cooperation and clustering of economic units and activities. Everyone’s role and ability to influence has changed dramatically. End-users have acquired an increased role; their views and society's values influence the decision-making process in both the private and public sectors. The demands of society and the ever-growing needs of cities have created a new reality.

A healthy digital business ecosystem is expected to deliver economic growth, environmental sustainability and social progress [

54]. Subsequently, the city’s business ecosystem contributes growth, sustainability and quality of life. Meanwhile, the continued upward trajectory of the ICT industry highlights the dynamics of digital transformation and its ability to generate multiply benefits for the economy and society [

56]. The economic results of smart city initiatives affect the overall economic picture of a country through the formation of new start-ups, job creation, workforce development and the overall improvement of productivity, agencies and the country as a whole [

37]. Therefore, it is important to study the benefits, such as efficiency, effectiveness, sustainability, and equality, of executing initiatives on relating to the smart economy (H4).

H4: The implementation of actions relating to the economy and innovation in a smart city has a positive and significant impact on the creation benefiting the urban environment and creating value to the urban ecosystem.

3. Data and Research Method

3.1. Research Framework

The formation of a smart city consists of three phases: phase I involves assessing the importance of smart city initiatives during the planning phase; phase II focuses on the implementation of planned initiatives; and phase III is the fully functional smart city or smart city 3.0. To form the conceptual framework, the paper focuses on the actions relating to the smart economy and innovation during the first two aforementioned phases, which set the foundations for a smart city. It examines the relationship between the assessment level of importance during the planning phase and the degree of implementation of initiatives relating to the economy and innovation. The factors assessing the impact of importance and degree of implementation are: (1) attractive environment for setting up new businesses (e.g., start-ups, spin-offs, spin-outs), (2) creating support mechanisms (i.e., incubators) for new businesses, (3) cooperative joint ventures, and (4) collaboration with teams from a university or research groups.

The hypotheses are based on the relationships and impact between the selected phases and their factors (

Figure 2). They are evaluated through an empirical model, which includes factors for decision making, smart city strategy, and impact of smart city factors. The currently implemented smart city strategy is investigated to determine its influence amongst the phases I and II, as mediator. Complementary, the research takes into account the needs of the urban environment that impact the planning (phase I) and implementation phase of the initiatives (phase II), relating to enhancing the economy and innovation: (1) the city’s internal operational needs, and (2) the local economy needs.

3.2. Data Specifications and Processing

Data originates from field research carried out from November 2018 to April 2019 via a structured questionnaire. It focused on three main aspects of a Greek municipality: (i) the technological and digital particularities, (ii) the features of a smart city strategy planned and implemented during the past years and (iii) the characteristics of the formulated partnerships with the city's public authorities. The final sample corresponds to over 70% of the Greek municipalities and population [252 Municipalities across all 13 administrative regions of Greece (NUTS II level)]. The data and its characteristics are published in the Data in Brief [

57].

Based on the proposed hypotheses and research model, the appropriate indicators were selected to form the suitable variables to measure and assess the research model and its main components. Therefore, the crucial factors that influence the strategic planning and implementation of smart city projects may be identified. Summarizing, all the measurement properties of the observed indicators and their constructs, including their description, the descriptive statistics [mean and standard deviation (S.D.)] and outer variance inflation factor (VIF)(max=5) [

58], are presented in the

Table 1. All the indicators are measured in a Likert scale from 1 (low) to 5 (max), apart from the smart city strategy, which is from 1 (no existing strategy) to 4 (complete strategy for smart cities). All indicators are grouped according to their conceptual relevance and validated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Based on the nature of the model, all latent variables meeting the approved statistical criteria for inclusion are classified as reflective [

59,

60].

3.3. Research Method

Based on the conceptual model and the data characteristics, the research method applied for investigating the variables' conceptual relationships is the Partial Least Square - Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), using the SmartPLS 4.0 [

61]. This method is preferred for the prediction and theory development [

59,

62,

63], in contrast to the other method the Covariance Based - Structural Equation Modelling (CB-SEM). The criteria of our choice are the nature of research and the characteristics of the data.

4. Model Verification and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Verification

The first step involves formulating the measurement model and evaluating the reliability and validity of the relationships between the observed variables and their corresponding latent variables [

64]. The loading of each construct range from 0.811 to 0.946 (p<0.001). The criteria to evaluate the measurement model and test the construct reliability and validity of the four reflective latent variables are the Cronbach's Alpha (CA), the Dijkstra-Henseler's rho (ρ

A), the Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with all having a lower threshold value of 0.700 (

Table 2). All four criteria exceed the threshold values ensuring construct reliability and convergent validity [

64,

65,

66,

67]. Additionally, the constructs show a clear conceptual distinction, as the measurement model's discriminant validity is acceptable (higher threshold: criteria HTMT < 0.850) [

68] (

Table A1)(

Appendix A).

4.2. Structural Model Verification

After assessing the measurement model, we evaluated the structural model's ability to predict the concept under investigation [

64]. The results are presented in

Table 3. Our findings show the model's ability to predict the latent constructs [

59] and no significant multicollinearity problems [

69,

70]. Additionally, the paper evaluated the mediating effect of the smart city strategy, as a factor that support the implementation of smart city initiatives relating to economy and innovation. To comprehend the impact of the mediation effect, we present the direct and indirect effects of the paths in

Table A2 (

Appendix A). Based on the analysis, the direct effects of the "

Smart city strategy" are statistically significant for all its paths.

4. Discussion

All the compulsory conditions are met for the structured models, thus resulting to the examination of the research's hypotheses (

Table 4). According to the analysis conducted, all the initial hypotheses are confirmed.

The findings in this paper are aligned with previous presented work, indicating that the existence of a smart city strategy can have a significant impact on implementing the relevant actions. Also, it is important to have a plan of initiatives that are aligned with the needs of the municipality and the business environment.

In this effort, the role of local government and stakeholders in planning, resources, financing and sustainability of actions is important. Finding and activating mechanisms, such as encouraging and engaging investors to create business initiatives and citizens to capitalize on and accept these initiatives, is a delicate balance to ensure economic and social sustainability. Their role is more important than it may seem. In that perspective, a supportive urban environment offers many business perspectives and cultivates an entrepreneurial spirit, both at individual and collective level.

Today, smart cities are presented as the solution for managing the urban phenomenon, waste, and resources. Despite their increasing growth, there is a climate of doubt about the intentions of business initiatives regarding technological development [

71,

72]. More specifically, although the smart city is about a commonly accepted fast-growing market, it is not clear how sustainable revenues and values are created. This discourages private sector entry without public support. However, since most cities are developed by public initiatives, the participation of the private sector with individual resources is an important factor. Therefore, a municipality needs to create the appropriate settings to help the private sector to take initiatives towards a more sustainable future.

At the same time, the role of the citizen has also changed, who acquires an active position and, as a driver of innovation, contributes to the creation of value [

73]. The habitants needs to take initiatives and participate in the different projects taking place in their municipality.

Potential future directions would be useful to include other economic factors that impact the capabilities of a municipality, like population, GDP, registered public and private entities etc. Also, if this can be applied at a European level, could include more diverse types of cities and could set the foundations for a roadmap to assist local authorities to form a tailor-made strategy to their need. This can be helpful to the smaller cities to attract more habitants and investment.

In summary, the dynamics of smart cities, the smart economy and the possibilities of ICT are putting a constant pressure on organizations at all levels to change. Even though the focus of an organization is profit, the new state of the urban environment forces organizations to focus on the value creation and public service delivery. This approach can unlock previous barriers, focusing on the needs of organizations and customers, and displaying a capability to adapt to changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Georgios Siokas; methodology, Georgios Siokas; formal analysis, Georgios Siokas; writing—original draft preparation, Georgios Siokas; writing—review and editing, Aggelos Tsakanikas; supervision, Aggelos Tsakanikas; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Discriminant validity by HTMT and Pearson correlation1.

Table A1.

Discriminant validity by HTMT and Pearson correlation1.

| |

Constructs |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 1 |

Assessment of Importance [P] |

|

0.564** |

0.389** |

0.250** |

0.204** |

| 2 |

Degree of Implementation [I] |

0.625 |

|

0.393** |

0.206** |

0.303** |

| 3 |

Factors for decision making |

0.433 |

0.445 |

|

0.303** |

0.450** |

| 4 |

Impact of smart city actions |

0.265 |

0.220 |

0.340 |

|

0.163** |

| 5 |

Smart city strategy |

0.213 |

0.322 |

0.481 |

0.171 |

|

Table A2.

Indirect and direct effect of the relationship of the variables (the t-values are shown in the parentheses).

Table A2.

Indirect and direct effect of the relationship of the variables (the t-values are shown in the parentheses).

| No. |

Relationships |

Direct |

Indirect |

| 1 |

Assessment of Importance -> Degree of Implementation |

0.524 (10.900)*** |

0.040 (2.425)** |

| 2 |

Assessment of Importance -> Impact |

|

0.116 (3.267)*** |

| 3 |

Assessment of Importance -> Smart city strategy |

0.204 (3.702)*** |

|

| 4 |

Decision Factors -> Assessment of Importance |

0.389 (6.944)*** |

|

| 5 |

Decision Factors -> Degree of Implementation |

|

0.219 (5.342)*** |

| 6 |

Decision Factors -> Impact |

|

0.045 (2.821)*** |

| 7 |

Decision Factors -> Smart city strategy |

|

0.080 (2.751)*** |

| 8 |

Degree of Implementation -> Impact |

0.206 (3.478)*** |

|

| 9 |

Smart city strategy -> Degree of Implementation |

0.196 (3.386)*** |

|

| 10 |

Smart city strategy -> Impact |

|

0.040 (2.195)** |

References

- Khan, Z.; Anjum, A.; Soomro, K.; Tahir, M.A. Towards Cloud Based Big Data Analytics for Smart Future Cities. Journal of Cloud Computing 2015, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakderi, C.; Komninos, N.; Tsarchopoulos, P. Smart Cities and Cloud Computing: Lessons from the STORM CLOUDS Experiment. Journal of Smart Cities 2016, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations Available online:. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Dameri, R.P.; Ricciardi, F. Smart City Intellectual Capital: An Emerging View of Territorial Systems Innovation Management. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2015, 16, 860–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habita Urban Indicators Guidelines – UN-Habitat; 2004.

- UNDP, U.N.D.P. Human Development Report 1991; New York, NY, 1991.

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D. Smart Cities: Issues and Challenges. In; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M., Eds.; Elsevier, 2019; p. 634 ISBN 9783540773405.

- Dhar, A. UN-HABITAT GLOBAL ACTIVITIES REPORT 2017; 2017.

- Kumar, T.M.V. E-Governance for Smart Cities; Vinod Kumar, T.M., Ed.; Advances in 21st Century Human Settlements; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2015; ISBN 978-981-287-286-9. [Google Scholar]

- Oladimeji, T.; Folayan, G. ICT and Its Impact on National Development In Nigeria : An Overview. Res Rev J Eng Technol 2018, 7, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Obiozor, W.E.; Ed, D. Identification of ICT for Development in Nigeria: Utilization, Literacy Efforts and Challenges. 2006, 1–18.

- BSI, S.P. BSI Standards Publication Smart City Concept Model – Guide to Establishing a Model for Data Interoperability. BSI 2014, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kamolov, S.; Kandalintseva, Y. The Study on the Readiness of Russian Municipalities for Implementation of the “Smart City” Concept. 2020, 392, 256–260. [CrossRef]

- Siokas, G.; Tsakanikas, A.; Siokas, E. Implementing Smart City Strategies in Greece: Appetite for Success. Cities 2021, 108, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Conceptualizing Smart City with Dimensions of Technology, People, and Institutions. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 2011, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, D.; Sahli, Y.; Berbaoui, B.; Maouedj, R. Towards Smart Cities: Challenges, Components, and Architectures; Springer International Publishing, 2020; Vol. 846; ISBN 9783030245139.

- European, C. European Smart Cities Available online:. Available online: http://www.smart-cities.eu/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. Dynamics of Internet Business Models. In Internet business models and strategies: text and cases; Afuah, A., Tucci, C.L., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 78–102. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, C.; Kraus, S.; Syrjä, P. The Smart City as an Opportunity for Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 2015, 7, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. The Making of the Urban Entrepreneur. Calif Manage Rev 2016, 59, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, R.K.R. Smart Cities and Entrepreneurship: An Agenda for Future Research. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2019, 149, 119763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L. Smart Cities from Scratch? A Socio-Technical Perspective. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2015, 8, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; del Bo, C.F. Smart Innovative Cities: The Impact of Smart City Policies on Urban Innovation. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2019, 142, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. The 3 Generations Of Smart Cities Available online:. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/3047795/the-3-generations-of-smart-cities (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Roden, S.; Nucciarelli, A.; Li, F.; Graham, G. Big Data and the Transformation of Operations Models: A Framework and a New Research Agenda. Production Planning & Control 2017, 28, 929–944. [Google Scholar]

- Berrone, P.; Ricart, J.E.; Carrasco, C. The Open Kimono: Toward a General Framework for Open Data Initiatives in Cities. Calif Manage Rev 2016, 59, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, R. Debt Crisis in Portugal Delays PlanIT Valley. Construction Research and Innovation 2011, 2, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, A. van; Teuben, H. Smart Cities – How Rapid Advances in Technology Are Reshaping Our Economy and Society; 2015.

- Harrison, C.; Eckman, B.; Hamilton, R.; Hartswick, P.; Kalagnanam, J.; Paraszczak, J.; Williams, P. Foundations for Smarter Cities. IBM J Res Dev 2010, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.J.; Kerr, S.J.; Bayon, V. The Development of the Virtual City: A User Centred Approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd European conference on disability, virtual reality and associated technologies (ECDVRAT 1998); Shakey, P., Rose, D., Lindström, J.-I., Eds. ICDVRAT. The University of Reading: Reading, UK, 1998; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Καλογήρου, Γ.; Τσακανίκας, Ά.; Σιώκας, Ε.; Παναγιωτόπουλος, Π.; Πρωτόγερου, A.; Μαυρωτάς, Γ. Oργάνωση Και Διοίκηση Επιχειρήσεων Για Μηχανικούς; Σύνδεσμος Ελληνικών Aκαδημαϊκών Βιβλιοθηκών - Εκδόσεις Κάλλιπος: Aθήνα, 2015; ISBN 9789606033803. [Google Scholar]

- OECD, O. for E.C. and D. The E-Government Imperative. OECD egovernment studies 2003, 203 p. [CrossRef]

- OECD Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance; OECD Studies on Water; OECD, 2015; Vol. 14; ISBN 9789264231115.

- OECD Public Procurement Recommendation - OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/ (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- OECD The Innovation Imperative in the Public Sector; 2015.

- Giffinger, R.; Haindlmaier, G.; Kramar, H. The Role of Rankings in Growing City Competition. Urban Res Pract 2010, 3, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Saxena, S.; Godbole, T. ; Shreya Developing Smart Cities: An Integrated Framework. Procedia Comput Sci 2016, 93, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod Kumar, T.M.; Dahiya, B. Smart Economy in Smart Cities; Vinod Kumar, T.M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 9789811016103.

- Echraghi, K. Using APIs to Gain Unfair Competitive Advantage in the Network Economy Available online:. Available online: https://medium.com/inside-gafanomics/using-apis-to-gain-unfair-competitive-advantage-in-the-network-economy-664e169c94b0 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Mitra, J. SMART Cities: Ecology, Technology, Entrepreneurship and Citizenship an Agenda.; University of Essex, 2017; pp. 1–47.

- Battarra, R.; Gargiulo, C.; Pappalardo, G.; Boiano, D.A.; Oliva, J.S. Planning in the Era of Information and Communication Technologies. Discussing the “Label: Smart” in South-European Cities with Environmental and Socio-Economic Challenges. Cities 2016, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, B.; Lewis, C. Sizing up People and Process: A Conceptual Lens for Thinking about Cybersecurity in Large and Small Enterprises. Journal of Cyber Policy 2017, 2, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Buys, L.; Ioppolo, G.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; da Costa, E.M.; Yun, J.H.J. Understanding ‘Smart Cities’: Intertwining Development Drivers with Desired Outcomes in a Multidimensional Framework. Cities 2018, 81, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhlandt, R.W.S. The Governance of Smart Cities: A Systematic Literature Review. Cities 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourabi, H.; Mellouli, S.; Bouslama, F. Modeling E-Government Business Processes: New Approaches to Transparent and Efficient Performance. Information Polity 2009, 14, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, J.; Parlikad, A.K. A Conceptual Framework for the Alignment of Infrastructure Assets to Citizen Requirements within a Smart Cities Framework. Cities 2019, 90, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; El-Zaart, A.; Adams, C. Smart Sustainable Cities Roadmap: Readiness for Transformation towards Urban Sustainability. Sustain Cities Soc 2018, 37, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding Smart Cities: An Integrative Framework. Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2012, 2289–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, P.; De Marco, A.; Cagliano, A.C.; Mangano, G.; Scorrano, F. Current Trends in Smart City Initiatives: Some Stylised Facts. Cities 2014, 38, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Rai, D.P. Developing a Sustainable Smart City Framework for Developing Economies: An Indian Context. Sustain Cities Soc 2019, 47, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Joss, S.; Schraven, D.; Zhan, C.; Weijnen, M. Sustainable-Smart-Resilient-Low Carbon-Eco-Knowledge Cities; Making Sense of a Multitude of Concepts Promoting Sustainable Urbanization. J Clean Prod 2015, 109, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desdemoustier, J.; Crutzen, N.; Giffinger, R. Municipalities’ Understanding of the Smart City Concept: An Exploratory Analysis in Belgium. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2019, 142, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Pardo, T.A.; Nam, T. Smarter as the New Urban Agenda: A Comprehensive View of the 21st Century City. Computer Law & Security Review 2016, 12, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, D. New Forms of Entrepreneurship and Innovation for Developing Smart Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya - BarcelonaTech, 2016.

- Sundararajan, A. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EITO, E.I.O.; ΣΕΠΕ, Σ.Ε.Π. & Ε.Ε. Έρέυνα Για Την Aγορά Τεχνολογιών Πληροφορικής & Επικοινωνιών 2019/ 2020; Σύνδεσμος Επιχειρήσεων Πληροφορικής & Επικοινωνιών Ελλάδας: Aθήνα, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siokas, G.; Tsakanikas, A. Questionnaire Dataset: The Greek Smart Cities - Municipalities Dataset. Data Brief 2021, 107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plann 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. European Business Review 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3 2015.

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. Advances in International Marketing 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Chin, W.W. A Comparison of Approaches for the Analysis of Interaction Effects between Latent Variables Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling 2010, 17, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: A Comparative Evaluation of Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling Methods. J Acad Mark Sci 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. Industrial Management and Data Systems 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structure Equation Models. J Acad Mark Sci 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration. British Journal of Management 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Testing Statistical Assumptions: Blue Book Series. Asheboro: Statistical Associate Publishing 2012, 12, 15, 16–20, 24, 31, 41–43, 44, 46–48, 50. 15.

- Anthopoulos, L.G.; Fitsilis, P. Understanding Smart City Business Models: A Comparison. WWW 2015 Companion - Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web 2015, 529–533. [CrossRef]

- Söderström, O.; Paasche, T.; Klauser, F. Smart Cities as Corporate Storytelling. City 2014, 18, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, E. Democratizing Innovation: The Evolving Phenomenon of User Innovation. International Journal of Innovation Science 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).