1. Introduction

Syndactyly, derived from the Greek words “syn” (meaning “together”) and “dactyly” (meaning “digits”), ranks among the most prevalent congenital malformations affecting the extremities [

1,

2,

3]. It arises due to a developmental separation failure (webbing) during embryological limb formation, resulting in the fusion of the digits. This condition frequently affects the ring and middle fingers. The incidence of syndactyly is estimated to be approximately one occurrence per 2,500 children, with a higher prevalence among boys and individuals of Caucasian ethnicity. Mothers aged 40 years or older face an increased risk of giving birth to an offspring with congenital limb deformities compared to mothers below 30. Predominantly a genetic disease, however, contributing factors such as maternal smoking, lower nutritional or socio-economic status and increased meat and egg consumption during pregnancy have also been identified [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

From a clinical perspective, the malformation may manifest as the fusion of soft tissue or bones, leading to the fusion of the fingers characterised as complete or incomplete. This fusion may encompass the phalanges and may also extend to the carpal/tarsal bones, It could even reach the metacarpal’s or metatarsal’s level, and rarely it may extend to the distal end of the forearm or lower leg [

1,

2,

3]. The malformation can be further categorised as simple, complex and complicated. It can exhibit symmetry or asymmetry and may affect one side (unilateral) or both sides (bilateral), affecting the right, left or both sides and feet, hands, or both. This condition may present as an isolated malformation (non-syndromic) or as a characteristic feature of hundreds of recognised syndromes. The classification system for non-syndromic syndactyly, initially proposed by Temtamy and McKusick is based on the phenotypic appearance. This classification was extended by Malik et al. in 2012. Currently, non-syndromic syndactyly is classified into nine primary types by the Temtamy and McKusick classification, which are further divided into subtypes [

2,

3,

4]. Non-syndromic syndactyly is predominantly isolated, but it can occur together with other disorders or malformations such as synostosis, acro-syndactyly, cleft hand, clinodactyly, synonychia or polydactyly. On the other hand, syndromic syndactyly can be observed in specific conditions like Apert Syndrome, Poland’s Syndrome, Pfeiffer Syndrome and numerous others [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Diagnosing the condition relies primarily on patient history and physical examination. Notably, the deformity may be apparent at birth or even detectable on ultrasound images during fetal development. Treatment typically necessitates surgical intervention, as potential benefits outweigh the associated risks. However, surgery is contraindicated in cases of mild syndactyly where functionality is preserved, complex syndactyly with risk of functional deterioration due to surgery, or medical conditions that interfere with the surgical approach. Careful consideration of the specific situation is essential to determine appropriate therapy [

1,

4,

7].

The surgery is ideally performed at around 12 months of age to allow for uninterrupted growth and minimise the risks of postoperative complications. Reconstruction should be concluded before the child reaches school age [

1,

7,

8,

9]. The specific surgical approach varies based on the classification of the malformation and its individual features. Careful consideration and comprehensive assessment of the condition will guide the selection of the most appropriate surgical technique. Similar flaps are employed in both simple and complete syndactyly cases, including the use of rectangular, triangular, omega and multilobed flaps. Other methods such as Z-plasty, four-flap Z-plasty, double-opposing Z-plasty, Cronin’s technique, Sharma’s method, or the “open-finger” method can also be utilized[

1,

7]. However, it is important to note that the “open-finger” method has raised concerns due to the potential for secondary cicatrix formation, scar contracture and hypertrophic scarring, leading to controversies regarding its application [

3,

7]. Surgical release procedures utilising skin grafting encompass a variety of methods such as the M-V flap, reverse W-M flap, Flatt technique, dorsal omega flap, or the combination of V-Y and rectangular flaps [

1,

7,

8]. Alternatively, operational methods designed to mitigate the need for grafts include trilobed flap, three-square flap, reverse-triangular flap, open finger technique, V-M plasty, end of skin graft, or the modified bell-bottom flap [

1,

7]. Each technique has its advantages and limitations, with selection based on the case’s specifics and the surgeon’s expertise. In complex cases, surgical planning may involve the utilisation of multiple approaches, potentially necessitating several surgeries and the implementation of multiple flaps, which carry a higher risk for complications. During surgery, a significant emphasis should be placed on meticulously assessing the patient's neurovascular structures. The course of these structures is often unpredictable, unlike the normal anatomical structure. The amount of osseous involvement directly correlates with the extent of neurovascular involvement and the associated risk of injury[

1,

7]. Simple cases are resolved by surgery with improvement in hand function, resulting in digits that are freely movable. The correction of complex syndactyly often carries the risk of reoperation, contractures and scarring, potentially leading to loss of function. Intraoperative complications, namely neurovascular injury, mandate immediate and diligent care to prevent loss of the affected appendage and minimise any negative functional consequences. Postoperative complications that may arise include infections, graft maceration or failure, wound dehiscence (separation of wound edges), web creep (recurrence of webbing due to growth), scar hypertrophy, nail deformities, and joint contractures [

1,

7,

8,

10].

Clinodactily refers to the congenital curvature of a digit beyond the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint. When the angular deviation is within physiological limits, typically fewer than 5 to 10 degrees, it is considered a normal variation [

11,

12]. However, if the coronal angulation exceeds 10 degrees, it is classified as a pathological deformity. This curvature seen in clinodactyly is primarily attributed to the abnormal triangular or trapezoidal shape of one or more phalanges, leading to the misalignment of the interphalangeal joint(s) involved [

11,

12]. This malformation causes the affected finger to exhibit an asymmetric longitudinal growth, yielding the curved appearance of the finger. Clinodactyly can occur as syndromic, familial (inherited) or sporadic (occurring by chance). Classified by Burke and Flatt into four groups: (1) familial, (2) other congenital anomaly, (3) due to epiphyseal injury (4) due to triphalangeal thumb. This classification is sufficient to diagnose and find the origin of the malformation; however, it is not suitable for choosing the appropriate treatment option [

11,

13,

14]. Cooney’s classification system differentiates between simple and complex clinodactyly and takes into account the curvature (deviation in degrees) and the involvement of surrounding tissues [

12,

15,

16]. The most recent classification, expanded by Ali et al. is based on the severity of angular deviation. Composed of four groups, with the first group involving physiological curvature up to 5 degrees. The second group is mild curvature with a 5-10-degree deviation, while the third group includes 15-30-degree deformities and the fourth group includes patients with severe curvature greater than 30 degrees [

11,

12,

16,

17]. It most commonly affects the middle phalanx of the fifth digit, as well as the proximal phalanx of the first and second fingers. The aetiology of this condition is still not fully understood. The condition commonly affects males, frequently bilaterally, and has an occurrence rate ranging from 2-19% [

11,

12,

17,

18]. The malformation has been linked to numerous syndromic anomalies, namely, Klinefelter syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Fanconi anaemia, Cenani-Lenz syndactyly, Turner syndrome, and is found in approximately 25% of children with Down syndrome [

11]. The association with multiple syndromes highlights the diverse range of conditions where clinodactyly may be observed as a feature. The abnormal growth is attributed to the peculiar configuration of the proximal portion of the phalanx’s epiphyseal growth plate. This abnormal configuration contributes to the curvature of the finger during growth. In this condition, the epiphyseal plate takes on a C-shaped appearance, yielding incomplete or restricted growth on one side of the phalanx. The presence of a delta phalanx occurs when there is early and complete ossification of the physeal plate, leading to disrupted or restricted growth of the affected digit. In some cases, traumatic injuries of the plate can result in an acquired case of clinodactyly [

11,

12,

17,

19].

Diagnosis is based on a comprehensive physical exam and a detailed review of the patient’s history, which helps differentiate between the congenital or traumatic origins of the deformity [

17]. A thorough evaluation should encompass range of motion testing to assess and document the impact on grasp and pinch functions. On radiographs, a C-shaped physis might be present along with the delta phalanx formation, providing insights into the underlying structural abnormalities [

9,

11,

12,

15,

19].

Splinting of the affected digit is generally not recommended and has been shown to be ineffective as a treatment option [

12,

16,

19]. In the majority of cases, conservative management through observation is preferred; surgery for cosmetic purposes is typically discouraged due to the associated complications, such as scarring and reduced joint mobility. Surgical intervention becomes necessary in instances of severe angulation and shortening, especially if the thumb or the radial digits are involved. Such cases could significantly interfere with the hand’s grasp and punch function, justifying the need for surgical correction. The operative technique for clinodactyly is referred to as corrective osteotomy, which is ideally performed at a skeletally mature age to minimise the risk of physeal injury and excessive or inadequate correction [

18]. Various methods could be employed, including reverse wedge osteotomy, opening or closing wedge osteotomy, and epiphyseal bracket resection and fat grafting. In open wedge osteotomy, bone grafting is typically performed, enabling the preservation or even an increase of the length of the digit. In contrast, closed wedge osteotomy often results in some degree of shortening [

16,

20]. Mild soft tissue deficits that are created can be managed with “Z”-plasty. In contrast, severe soft tissue defects might demand advancement or rotational flaps for adequate coverage and optimal wound healing. “Vikcer’s physiolysis”, also known as epiphyseal bracket resection and fat grafting, is an alternative method of treatment that can be employed in patients with open growth plates. During this procedure, the cartilaginous or osseous bracket of the short end of the digit is surgically resected and interposed, and the resulting void is filled with fat tissue [

18,

21]. Indeed, the process of longitudinal growth over the course of one to two years is expected to correct the angulation. This approach has demonstrated its effectiveness in comparison to osteotomy, particularly when dealing with deformities that are less than 55 degrees [

11,

18]. Complications include growth arrest, skin deficits, scarring, stiffness, over or under-correction, and the risk of infection [

11,

18,

20].

3. Discussion

Numerous flap designs have been employed in the correction of cutaneous syndactyly, either with or without the use of skin grafts. Methods without skin grafting, such as the three-square flap, trilobed flap, reverse triangular V-Y flap, dorsal V-Y metacarpal flap, dancing-girl flap, open finger technique, V-M plasty, end-of-skin graft, or the modified bell-bottom flap is advised in cases of incomplete and simple syndactyly [

1,

7,

10].

Surgical correction of more complex cases includes the Flatt technique, the dorsal omega flap, the M-V flap, the reverse W-M flap, and the combination of the V-Y and rectangular flap with full-thickness grafts. These can be obtained from various areas, such as the groin (frequently at the region of the anterior superior iliac spine), the dorsal or lateral thigh, the medial upper arm, the distal wrist, or the dorsal metacarpal region [

1,

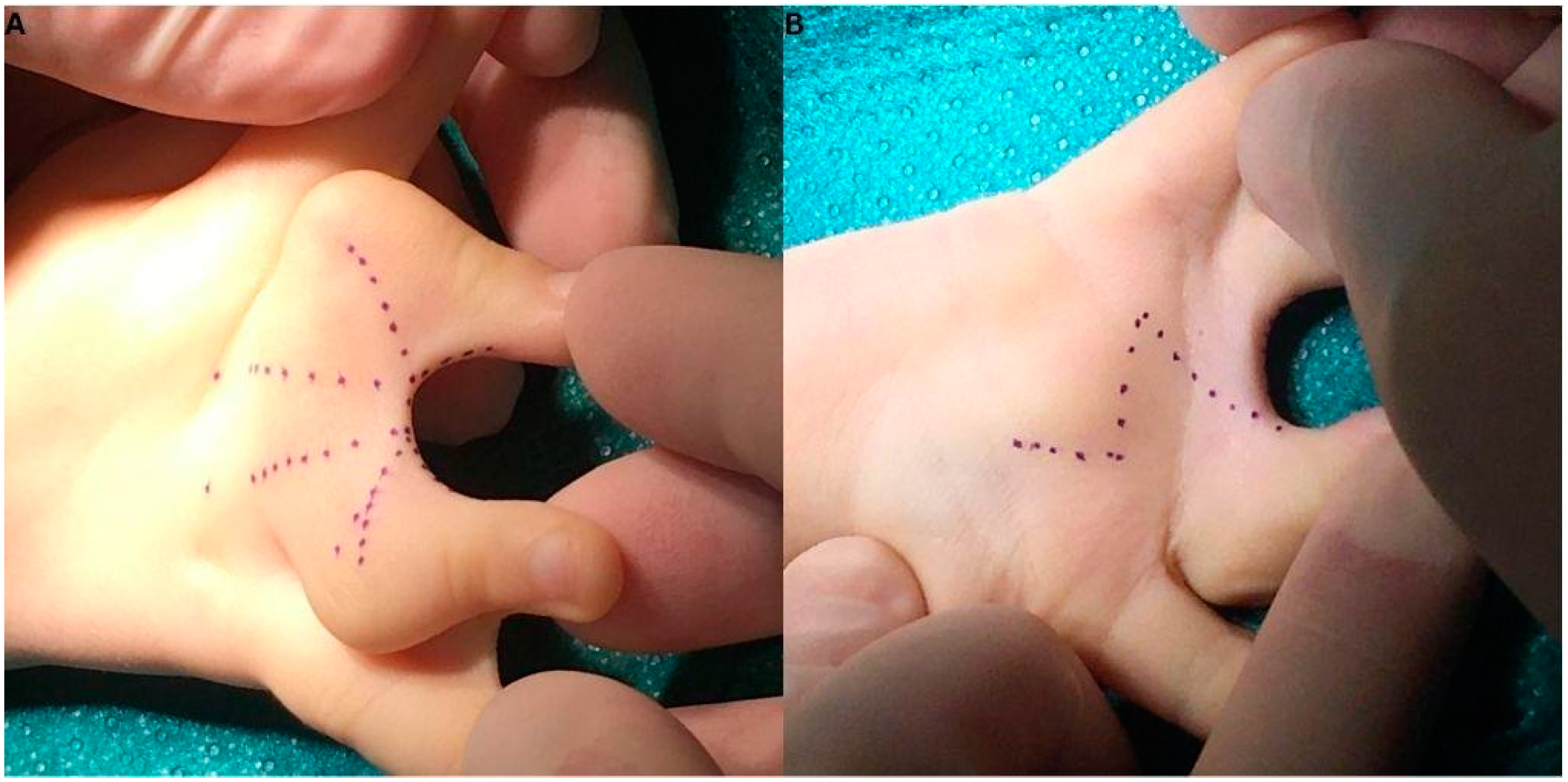

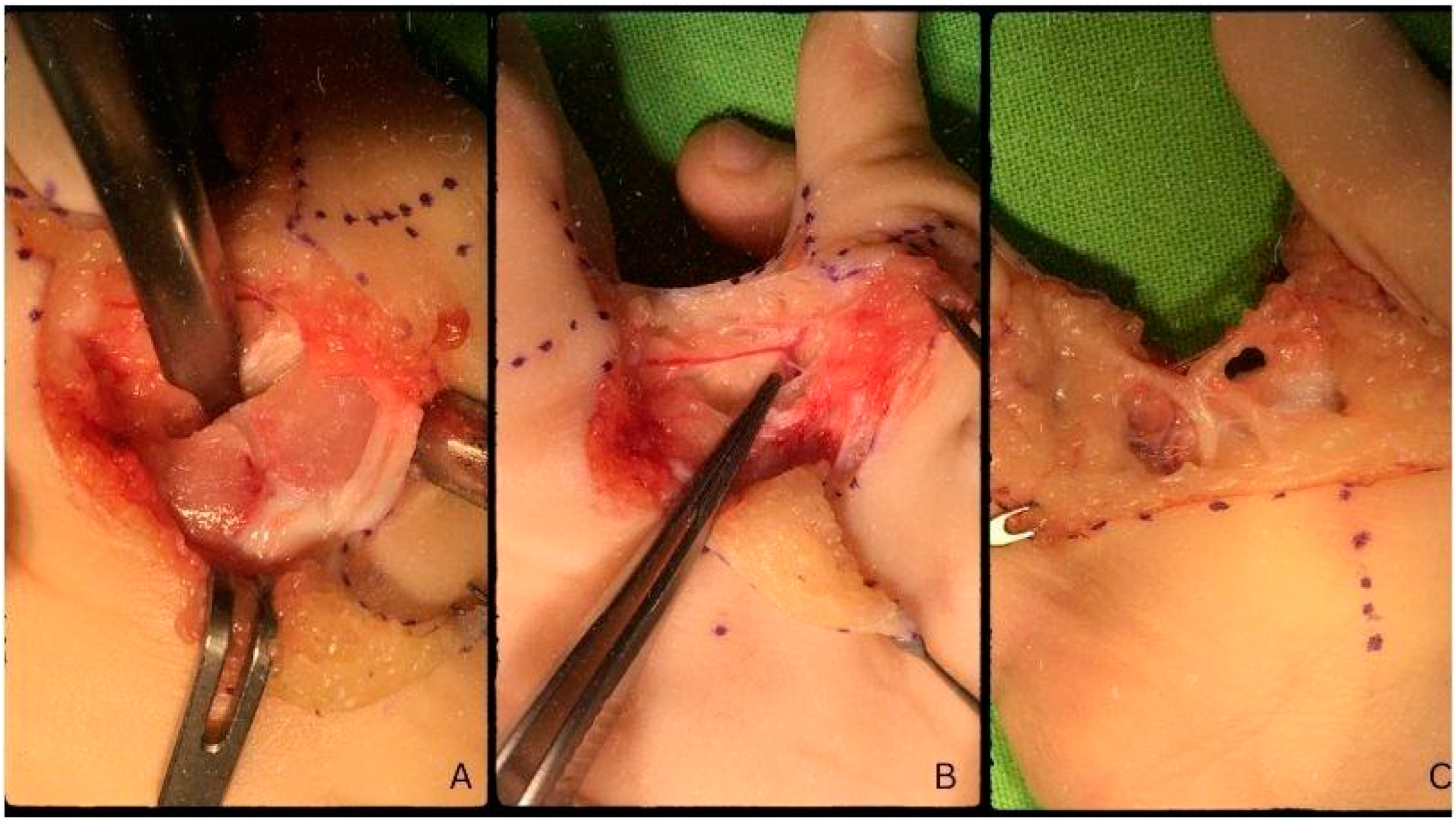

7]. In our case, we applied an individually made dorsal flap design to correct the III and IV. fingers syndactyly. This approach entailed a palmar incision line resembling that of a Z-plasty and a dorsal flap, composed of two bilobed triangular flaps on each side with a dorsal rectangular flap in the middle, collectively forming a shape resembling a W (Figure X). For the correction of the component responsible for the IV and V. finger’s involvement, two trapezoid flaps were used, which were also individually tailored for this patient during surgical planning. These approaches enabled the surgeons to operate without the need for skin grafting from additional donor sites.

Complications of surgical correction include web creep, graft failure or maceration, infection, joint contractures and scar hypertrophy [

1]. Factors that play a role in the formation of web creep after surgery include complex syndactyly, wound dehiscence, secondary healing due to graft failure, the use of split-thickness skin graft, and poor flap design. Graft failure or maceration is often associated with active children and improper immobilisation and, if substantial, requires a secondary grafting procedure. Joint contractures which are due to contracture of scars on the palmar aspect of the interphalangeal joints can be corrected by Z-plasty or skin grafting[

1,

7,

8].

Clinodactyly, as mentioned, can be corrected by open or closed wedge osteotomy, reverse wedge osteotomy, and by Vicker’s physiolysis [

11,

12,

18]. All methods have their advantages and disadvantages; however, in this case, we applied closed wedge osteotomy. This is due to the fact that the base of the fingers was fused forming a synchondrosis. As there was a single metacarpal connecting to both proximal phalanges, the removal of a wedge was necessary for achieving proper positioning. Both reverse wedge and open wedge methods were unfit for this particular case as the open wedge technique would have required a more aggressive operative approach, while reverse wedge osteotomy was deemed unfit as it would have required two wedges in order to turn both fingers appropriately. These would've required more extensive open surgery and hence, would've led to more scar formation. Complications include loss of motion, recurrence of deformity, infection, nonunion, or joint stiffness [

11,

16,

17].

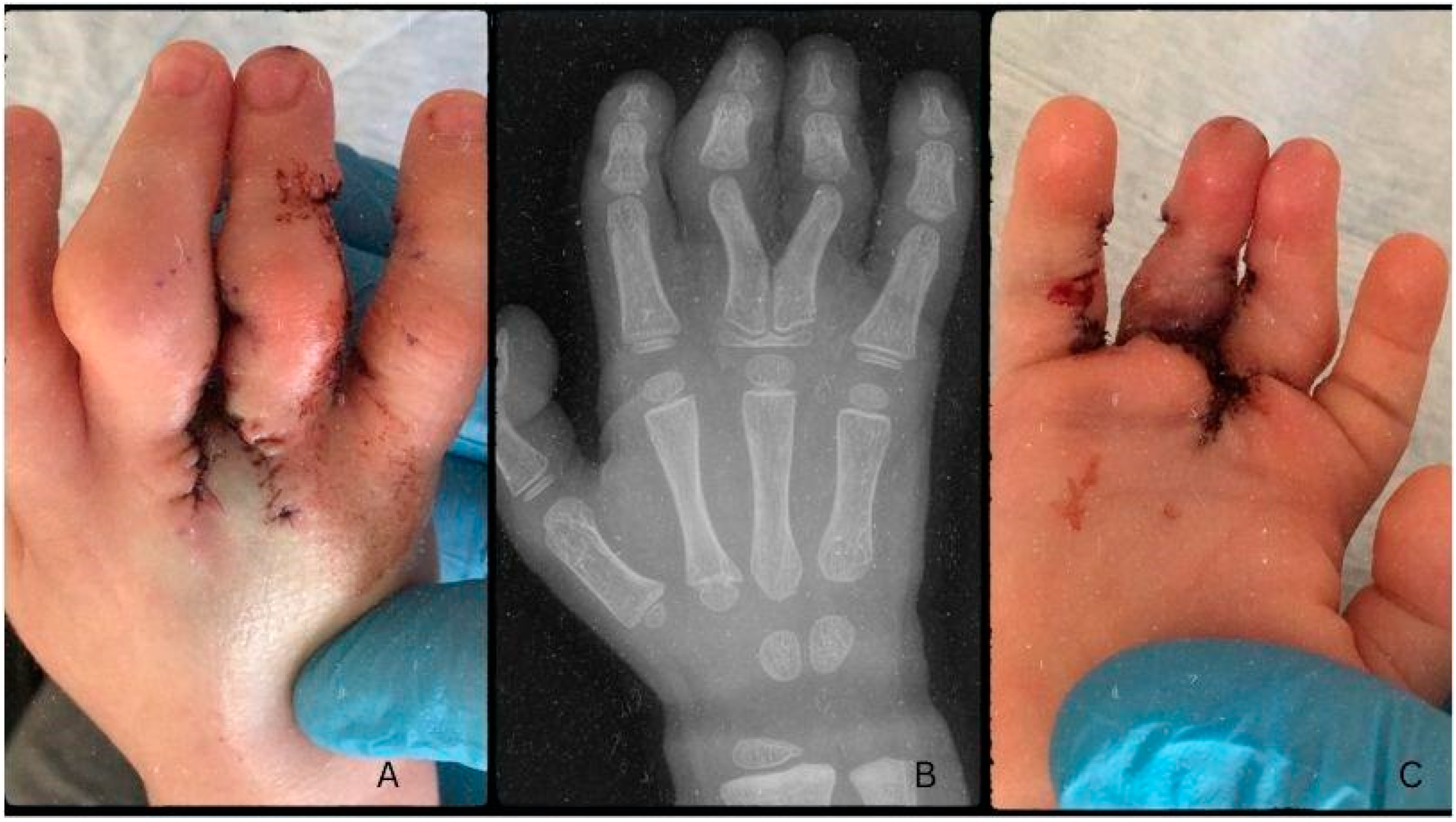

The osteotomy was performed at the phalangeal base; the synchondrosis was released, deepened and rotated to achieve the proper positioning of the fingers. The unlikely location of the curvature called for a unique approach to preserve the functionality of the III. and IV. finger. As the base of the digits fused, forming a synchondrosis on top of a common metacarpal, their orientation at the joint mandated careful repositioning to avoid loss of function or loss in the range of motion. By removing the wedge-shaped fragment from the fused joints, encompassing a bit of the metaphysis, we enable the rotation of the base of the digits into the appropriate position. The digits were fixed following the osteotomy with 2/0 absorbable (Vicryl®) thread in their final position. This was achieved by threading the suture line around the bone subperiosteally and utilising it to turn and fixate the fingers in an ideal position. The dorsal flaps were closed on the interdigital space for adequate coverage after repositioning. Interrupted and continuous intercutaneous sutures were applied for wound closure with 6/0 absorbable (Vicryl®) thread for best results. We cut and realigned the base of the fingers so that the growth plates were not affected to preserve the lengthening of the fingers during the growth period.

The patient was aged three at the time of the surgery and two years post-op; the child presents good functionality without complications or scarring. The growth of the fingers is symmetrical, and the deformity did not reoccur during growth. There were no signs of web creep affecting either the III. and IV. or the IV. and V. interdigital space.

Figure X:

The syndactyly affecting the ring and little finger was released by designing an island flap in the form of two trapezoid shapes. The release was successful and besides the soft tissue deficit, that was created during the first incisions which formed the flaps, the operation was unremarkable. The approximately 2x0.5 cm defect was closed by the use of a skin graft which was obtained from the excess skin of the V. finger’s flap. We decided on the local graft instead of a rotational flap as the turning of the lobe would’ve placed the skin under tension in a way not suitable for healing. To avoid this, we utilised the excess skin and grafted a piece onto the IV. finger’s inner side, facing the interdigital space.

Figure Y: