Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

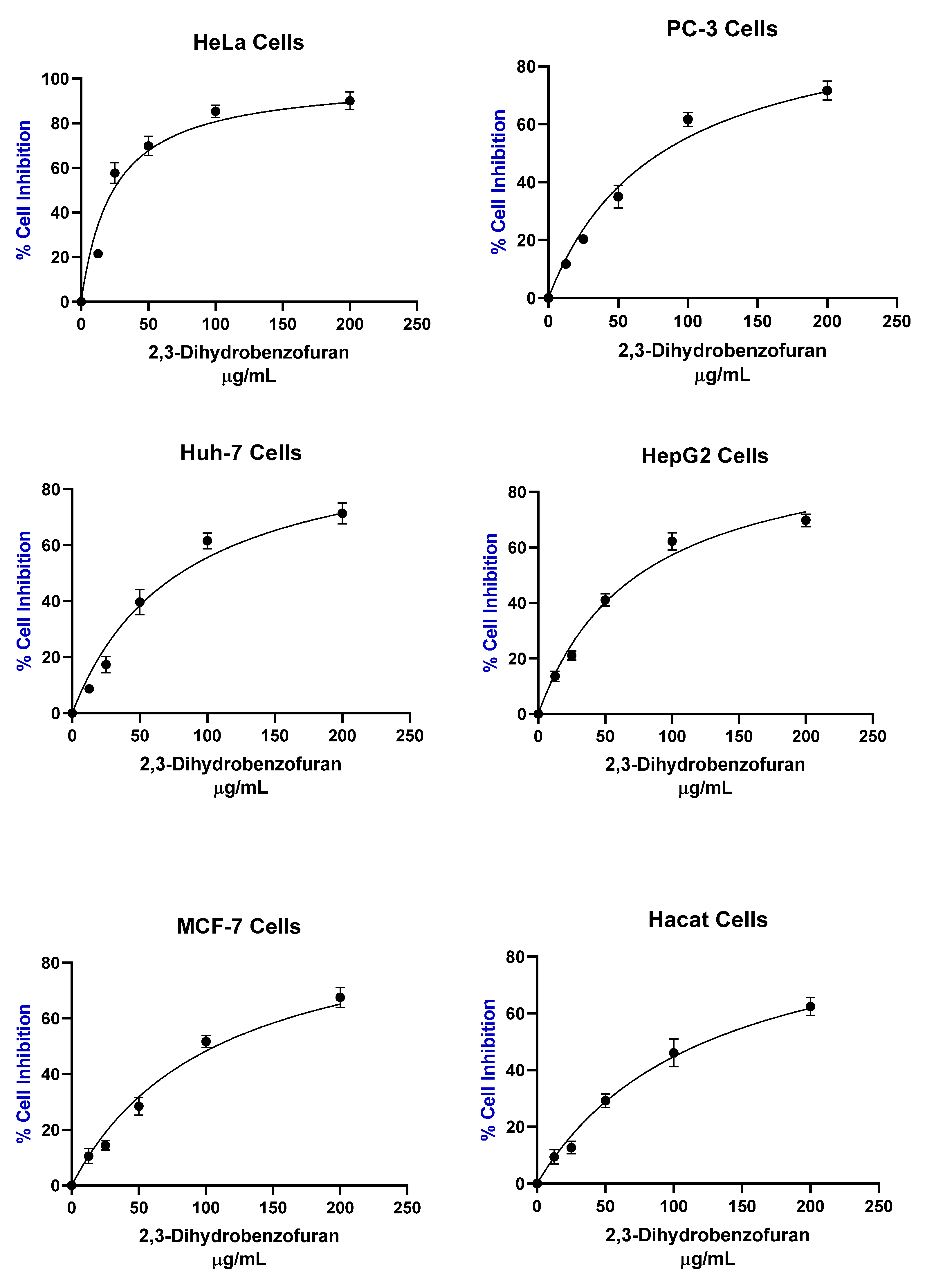

2.1. Cytotoxic evaluation of extracts

| Cellular line | IC50 µg/mL |

|---|---|

| HeLa | 23.86 ± 2.5 |

| PC-3 | 80.3 ± 4.6 |

| Huh-7 | 79.9 ± 3.78 |

| HepG2 | 74.62 ± 2.02 |

| MCF7 | 107.2 ± 1.52 |

| Hacat | 123.5 ± 15.17 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant material from the wild plant

3.2. Plant material from callus cultures

3.3. Obtaining organic extracts

3.4. Antiproliferative assay

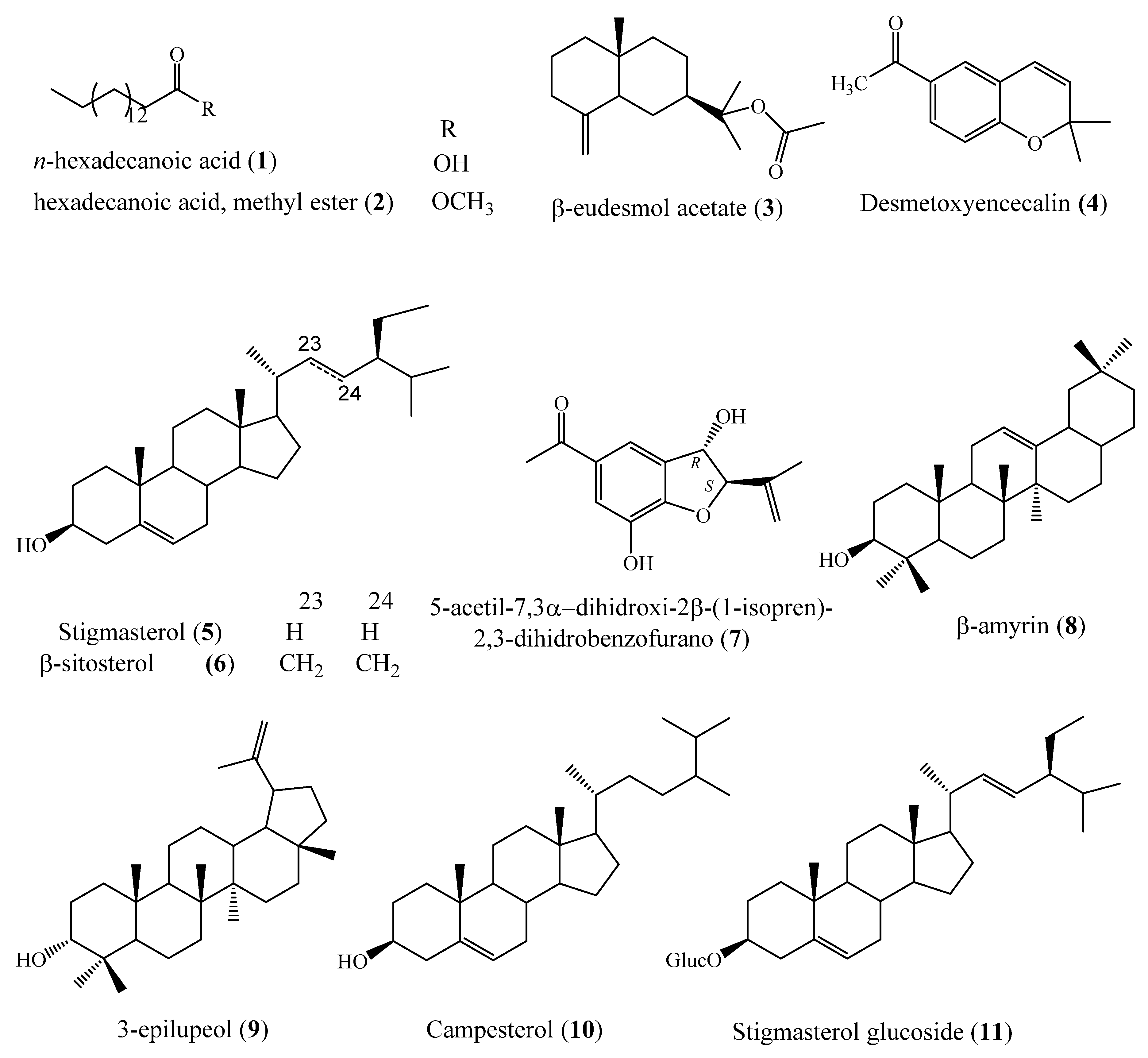

3.5. Purification of active compounds active ethyl acetate extract (Callus culture)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Argueta, A.; Cano, L.; Rodarte, M. Atlas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana, Tomo 1-3; Instituto Nacional Indigenista: Mexico, City, 1994, p. 1786.

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Rojas, G.; Navarro, V.; Herrera-Arellano, A.; Zamilpa-Alvarez, A.; Tortoriello, J. Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract from Ageratina pichinchensis on patients with tinea pedis: An explorative pilot study controlled with ketaconazole. Planta Medica 2006, 72, 1257-1261.

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Román-Ramos, R.; Zamilpa, A.; Jiménez-Ferrer, J.E.; Rojas-Bribiesca, G.; Tortoriello, J. Clinical trial to compare the effectiveness of two concentrations of the Ageratina pichinchensis extract in the topical treatment of onychomycosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 74-78. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Zamilpa, A.; González-Cortazar, M.; Alonso-Cortes, D.; Jiménez-Ferrer, E.; Aguilar-Santamaría, L.; Tortoriello, J. Pharmacological and chemical study to identify wound-healing active compounds in Ageratina pichinchensis. Planta Medica 2013, 79, 622-627. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Zamilpa, A.; Jiménez-Ferrer, J.E.; Rojas-Bribiesca, G.; Román-Ramos, R.; Tortoriello, J. Double-blind clinical trial for evaluating the effectiveness and tolerability of Ageratina pichinchensis extract on patients with mild to moderate onychomycosis. A comparative study with ciclopirox. Planta Medica 2008, 78, 1430-1435. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Zamilpa-Álvarez, A.; Ramos-Mora, A.; Alonso-Cortés, D.; Jiménez-Ferrer, J.E.; Huerta-Reyes, M.E.; Tortoriello, J. Effect on the wound healing process and in vitro cell proliferation by the medicinal mexican plant Ageratina pichinchensis. Planta Medica 2011, 77, 979-983. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Guadarrama B.; Navarro V.; León-Rivera I.; Ríos MY. Active compounds against tinea pedis dermatophytes from Ageratina pichinchensis var. bustamenta. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 23, 1559-1565. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramos, M.; Alvarez, L.; Romero-Estrada, A.; Bernabé-Antonio, A.; Marquina-Bahena, S.; Cruz-Sosa, F. Establishment of a cell suspension culture of Ageratina pichinchensis (Kunth) for the improved production of anti-inflammatory compounds. Plants 2020, 9, 1398. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramos, M.; Marquina-Bahena, S.; Alvarez, L.; Bernabé-Antonio, B.; Cabañas-García, E.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Cruz-Sosa, F. Obtaining 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran and 3-epilupeol from Ageratina pichinchensis (Kunth) R. King & Ho. Rob. Cell cultures grown in shake flasks under photoperiod and darkness, and its scale-up to an airlift bioreactor for enhanced production. Molecules 2023, 28, 578. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramos, M.; Marquina-Bahena, S.; Romero-Estrada, A.; Bernabé-Antonio, A.; Cruz-Sosa, F.; González-Christen, J.; Acevedo-Fernández, J.J.; Perea-Arango, I.; Alvarez, L. Establishment and phytochemical analysis of a callus culture from Ageratina pichinchensis (Asteraceae) and its anti-inflammatory activity. Molecules 2018, 23, 1258. [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/es/news/item/04-02-2020-who-outlines-steps-to-save-7-million-lives-from-cancer.

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778-798. [CrossRef]

- Rayan, A.; Raiyn, J.; Falah, M. Nature is the best source of anticancer drugs: Indexing natural products for their anticancer bioactivity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187925. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elias, N.; Farag, M.A.; Chen, L.; Saeed, A.; Hegazy, M.-E.F.; Moustafa, M.S.; El-Wahed, A.A.; Al-Mousawi, S.M.; Musharraf, S.G.; Chang, F.-R.; Iwasaki, A.; Suenaga, K.; Alajlani, M.; Göransson, U.; El-Seedi, H.R. Marine natural products: A source of novel anticancer drugs. Marine drugs 2019, 17, 491. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.-L.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Wei, W.-L.; Wu, S.-F.; Guo, D.-A. Traditional chinese medicine (TCM) as a source of new anticancer drugs. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 9, 1618-1633. [CrossRef]

- Obenauf, A.C. Mechanism-based combination therapies for metastatic cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eadd0887. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Mechanism of synergistic effect of chemotherapy and immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Immunol Immun 2011, 60, 419-423. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Parihar, L.; Parihar, P. Review on cancer and anticancer properties of some medicinal plants. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 1818-1835.

- Howat, S.; Park, B.; Oh, I.S.; Jin, Y.-W.; Lee, E.-K.; Loake, G.J. Paclitaxel: Biosynthesis, production and future prospects. N. Biotechnol. 2014, 31, 242-245. [CrossRef]

- Yan-Hua, Y.; Jia-Wang, M.; Xiao-Li, T. Research progress on the source, production, and anti-cancer mechanisms of paclitaxel. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 890-897. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Vincristine and vinblastine: A review. Int. J. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 23-30.

- Gezici, S.; Şekeroĝlu, N. Current perspectives in the application of medicinal plants against cancer: Novel therapeutic agents. Anti-cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 101-111.

- Tungmunnithum, D.; Thongboonyou, A.; Pholboon, A.; Yangsabai, A. Flavonoids and other compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: An overview. Medicines 2018, 5, 93. [CrossRef]

- Teiten, M.-H.; Gaascht, F.; Dicato, M.; Diederich, M. Anticancer bioactivity of compounds from medicinal plants used in European medieval traditions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, BCP-11728. [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, P.; Quispe, C.; Sharma, E.; Bahukhandi, A.; Sati, P.; Attri, D.C.; Szopa, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Docea, A.O.; Mardere, I.; Calina, D.; Cho, W.C. Anticancer potential of alkaloids: A key emphasis to colchicine, vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine, vinorelbine and vincamine. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 206. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Gandhi, A.; Fimognari, C.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bishayee, A. Alkaloids for cancer prevention and therapy: Current progress and future perspectives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172472. [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, Y.O.A.; Subramaniam, B.; Nyamathulla, S.; Shamsuddin, N.; Arshad, N.M.; Mun, K.S.; Awang, K.; Nagoor, N.H. Natural products for cancer therapy: A review of their mechanism of actions and toxicity in the past decade. J. Trop. Med. 2022, 5794350. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Parihar, L.; Parihar, P. Review on cancer and anticancer properties of some medicinal plants. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 1818-1835.

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Villarreal, M.L.; Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.; Dominguez, F.; Garcia-Carranca, A. Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: Pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 133, 945-972. [CrossRef]

- Soto, K.M.; Pérez, B.J.J.; Mendoza, L.M.L.; Apátiga-Castro, M.; López-Romero, J.M.; Mendoza, S.; Manzano-Ramírez, A. Antioxidants in traditional Mexicans medicine and their applications as antitumor treatments. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 482. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Islas-Garduño, A.L, Zamilpa, A.; Tortoriello J. Effectiveness of Ageratina pichinchensis extract in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis. A randomized, double-blind, and controlled pilot study. Phytotherapy Res. 2017, 31, 885-890. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Shen, M.; Jianhua, X.S.J. Phytosterols suppress phagocytosis and inhibit inflammatory mediators responses in RAW 264.7 macrophages and the correlation with their structure. Foods 2019, 8, 582. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.M.; Matloub, A.A.; Aboutabl, M.E.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Mohamed, S.M. Assessment of anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant activities of Cajanus cajan L. seeds cultivated in Egypt and its phytochemical composition. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 8, 1380-1391. [CrossRef]

- Kargutkar, S.; Brijesh, S. Anti-inflammatory evaluation and characterization of leaf extract of Ananas comosus. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 469-477. [CrossRef]

- Parvu, A.E.; Parvu, M.; Vlase, L.; Miclea, P.; Mot, A.C.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R. Anti-inflammatory effects of Allium schoenoprasum L. leaves. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 2, 309-315.

- Koshak, A.E.; Adballah, H.M.; Esmat, A.; Rateb, M.E. Anti-inflammatory activity and chemical characterization of Opuntia ficus-indica seed oil cultivated in Saudi Arabia. Arab J Sci Eng 2020, 45, 4571-4578. [CrossRef]

- Arpana, V.; Dileep, K.V.; Mandal, P.K.; Karthe, P.; Sadasivan, C.; Haridas, M. Anti-inflammatory property of n-hexadecanoic acid: Structural evidence and kinetic assessment. Chem Biol Drug Des 2012, 80, 434-439. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, I.M.; Korinek, M.; El-Shazly, M.; Wetterauer, B.; El-Beshbishy, H.A.; Hwang, T.-L.; Chen, B.-H.; Chang, F.-R.; Wink, M.; Singab, A.N.B.; Youseff, F.S. Anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-hyperglycemic activity of Chasmanthe aethiopica leaf extract and its profiling using LC/MS and GLC/MS. Plants 2021, 10, 1118. [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.-F.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Su, Y.-C.; Lin, I.-F.; Yang, S.-S.; Chen, Y.-M.; Chao, L.K. Study on the antiinflammatory activity of methanol extract from seagrass Zostera japonica. J. Agric. Food Chem 2006, 54, 306-311. [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.R.; Abdullah, N.; Ahmad, S.; Ismail, I.S.; Zakaria, M.P. Elucidation of in-vitro anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds isolated from Jatropha curcas L. plant root. Complementary Altern Med 2015, 15, 11. [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Fereydouni, N.; Rahimi, V.B.; Askari, N.; Sahebkar, A.H.; Rahmanian-Devin, P.; Samzadeh-Kermani, A. β-amyrin, the cannabinoid receptors agonist, abrogates mice brain microglial cells inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide/interferon-γ and regulates Mφ1/Mφ2 balances. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 438-446. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.; Mathew, L.E.; Vijayalakshmi, N.R.; Helen, A. Anti-inflammatory potential of β-amyrin, a triterpenoid isolated from Costus igneus. Inflammopharmacol 2014, 22, 373-385. [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.Y.; Chuan, T.T.; Siow, P.T.; Awang, K.; Mohd, N.H; Azlan, N.M.; Kartini, A. Cytotoxic, antibacterial and antioxidant activity of triterpenoids from Kopsia singapurensis Ridl. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2014, 6, 815-822.

- Mishra, T.; Arya, R.K.; Meena, S.; Joshi, P.; Pal, M.; Meena, B.; Upreti, D.K.; Rana, T.S.; Datta, D. Isolation, characterization and anticancer potential of cytotoxic triterpenes from Betula utilis bark. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159430. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.A.H.; Pinto, L.M.S.; Cunha, G.M.A.; Chaves, M.H.; Santos, F.A.; Rao, V.S. Anti-inflammatory effect of α, β-amyrin, a pentacyclic triterpene from Protium heptaphyllum in rat model acute periodontitis. Inflammopharmacology 2008, 16, 48-52. [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.M.; Nascimiento, A.M.; Lenz, D.; Scherer, R.; Meyrelles, S.S.; Boëchat, A.P.; Andrade, T.U.; Endringer, D.C. Triterpenes from the Protium heptaphyllum resin-chemical composition and cytotoxicity. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2014, 24, 399-407. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, T.B.C.; Costa, C.O.D.; Galvão, A.F.C.; Bomfim, L.M.; Rodrigues, A.C.B.C.; Mota, M.C.S.; Dantas, A.A.; dos Santos, T.R.; Soares, M.B.P.; Bezerra, D.P. Cytotoxic potential of selected medicinal plants in northeast Brazil. Complement Altern Med 2016, 16:199. [CrossRef]

- Okoye, N.N.; Ajaghaku, D.L.; Okeke, H.N.; Ilodigwe, E.E.; Nworu, C.S.; Okoye, F.B.C. Beta-amyrin and Alpha-amyrin acetate isolated from the stem bark of Alstonia boonei display profund anti-inflammatory activity. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 1478-1486. [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.M.; Morais, T.C.; Tomé, A.R.; Brito, G.A.C.; Chaves, M.H.; Rao, V.S.; Santos, F.A. Anti-inflammatory effect of α, β-amyrin, a triterpene from Protium heptaphyllum, on cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in mice. Inflammation Research 2011, 60, 673-681. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.O.; Oliveira, Y.I.S.; Adjafre, B.L.; de Moraes, M.E.A.; Aragão, G.F. Pharmacological effects of the isomeric mixture of alpha and beta amyrin from Protium heptaphyllum: A literature review. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 4-12. [CrossRef]

- Ambati, G. G.; Yadav, K.; Maurya, R.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Bishnoi, M.; Jachak, S. M. Evaluation of the in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of Gymnosporia montana (Roth). Benth leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115539. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.K.; de Olivera, H.L.; Melo, U.Z.; Mariano, F.C.M.; de Araujo, A.C.C.F.; Gonçalves, J.E.; Laverde, Jr.A.; Barion, R.M.; Linde, G.A.; Cristiani, G.Z. Antioxidant activity of α, and β-amyrin isolated from Myrcianthes pungens leaves. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 12, 1777-1781. [CrossRef]

- Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D.; Anh, L.H. α-amyrin and β-amyrin isolated from Celastrus hindsii leaves and their antioxidant, anti-xanthine oxidase, and anti-tyrosinase potentials. Molecules 2021, 26, 7248. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Estrada, A.; Maldonado-Magaña, A.; González-Christen, J.; Marquina, B.S.; Garduño-Ramírez, M.L.; Rodríguez-López, V.; Alvarez, L. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of six pentacyclic triterpenes isolated from the Mexican copal resin of Bursera copallifera. Complement Altern Med 2016, 16, 422. [CrossRef]

- Blancas, J.; Abad-Fitz, I.; Beltrán-Rodríguez, L.; Cristians, S.; Rangel-Landa, S.; Casas, A.; Torres-García, I.; Sierra-Huelsz, J.A. Chemistry, biological activities, and uses of copal resin (Bursera spp.) in Mexico. In: Murthy, H.N. (eds.) Gums, Resins and Latexes of Plant Origin 2022, (pp. 1-14), Reference Series in Phytochemistry Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monroy, M.B.; León-Rivera, I.; Llanos-Romero, R.E.; García-Bores, A. M.; Guevara-Fefer, P. Cytotoxic activity and triterpenes content of nine Mexican species of Bursera. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 4881-4885. [CrossRef]

- Akramov, D.Kh.; Mamadalieva, N.Z.; Porzel, A.; Hussain, H.; Dube, M.; Akhmedov, A.; Altyar, A.E.; Ashour, M.L.; Wessjohann, L.A. Sugar containing compounds and biological activities of Lagochilus setulosus. Molecules 2021, 6, 1755. [CrossRef]

- Maiyo, F.; Moodley, R.; Singh, M. Phytochemistry, cytotoxic and apoptosis studies of B-sitosteol-3-O-glucoside and B-amyrin from Prunus africana. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2016, 13, 105-112. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, R.F.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Yamada, K.; Ahmed, S.A. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory compounds from Red Sea Grass Thalassodendron ciliatum. Med Chem Res 2018, 27, 1238-1244. [CrossRef]

- Oyetunde-Joshua, F.; Moodley, R.; Cheniah, H.; Khan, R. Phytochemical and Biological studies of Helichrysum acutatum DC. A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy 2022, 14, 603-609.

- Rashed, K.N.; Ćiriĉ, A.; Glamoĉlija, J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Sokoviĉ, M. Identification of the bioactive constituents and the antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of different fractions from Cestrum nocturnum L. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 11, 273-279.

- Ezzat, M.I.; Ezzat, S.M.; El, D.K.S.; El, F.A.M. In vitro evaluation of cytotoxic activity of the ethanol extract and isolated compounds from the corms of Liatris spicata (L.) wild on HepG2. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 11, 1325-1328. [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, G.M.; Abreu, V.G.D.C.; Martins, D.A.D.A.; Aparecida, T.J.A.; Fontoura, H.D.S.; Carmona, C.D.; Piló-Veloso, D.; Alcântara, A.F.D.C. Anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities of steroids and triterpenes isolates from aerial parts of Justicia acumintissima (Acanthaceae). Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 75-81.

- Saleeb, M.; Mojica, S.; Eriksson, A.U.; Andersson, C.D.; Gylfe, A.; Elofsson M. Natural product inspired library synthesis - Identification of 2,3-diarylbenzofuran and 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran based inhibitors of Chlamydia trachomatis. Eur J Med Chem. 2018,143, 1077-1089. [CrossRef]

- Khanam H.; Shamsuzzaman. Bioactive Benzofuran derivatives: A review. Eur J Med Chem. 2015, 97, 483-504. [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.; Harmalkar, D.S.; Xu, X.; Jang, K.; Lee K. Bioactive benzofuran derivatives: Moracins A-Z in medicinal chemistry. Eur J Med Chem. 2015, 90, 379-393. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky R.; Schmid C.; Brun R. An “in vitro selectivity index” for evaluation of cytotoxicity of antitrypanosomal compounds. In Vitro Toxicol. 1996, 9, 315–324.

- Badisa R.B.; Darling-Reed S.F.; Joseph P.; Cooperwood J.S.; Latinwo L.M.; Goodman C.B. Selective cytotoxic activities of two novel synthetic drugs on human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 2993–2996.

- Boukamp P.; Petrussevska R.T.; Breitkreutz D.; Hornung J.; Markham A.; Fusenig N.E. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988, 3, 761-771. [CrossRef]

| Cellular Line | Wild Plant Leaves | Wild Plant Stems | Callus Cultures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAE (µg/mL) | ME (µg/mL) | EAE (µg/mL) | ME (µg/mL) | EAE (µg/mL) | ME (µg/mL) | Paclitaxel (nM)* |

|

| HeLa | 161±4.9 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 94.79±2.0 | 150.9±7.5 | 20±1.2 |

| PC-3 | 188.6±10.1 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 121.2±9.2 | 168.6±4.5 | 15±2 |

| Huh-7 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 132.8±8.5 | >200 | 25±3 |

| HepG2 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 122.9±2.5 | >200 | 10±1.5 |

| MCF-7 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 191.3±6.4 | >200 | 22±4 |

| Hacat | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 114.7±15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).