Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

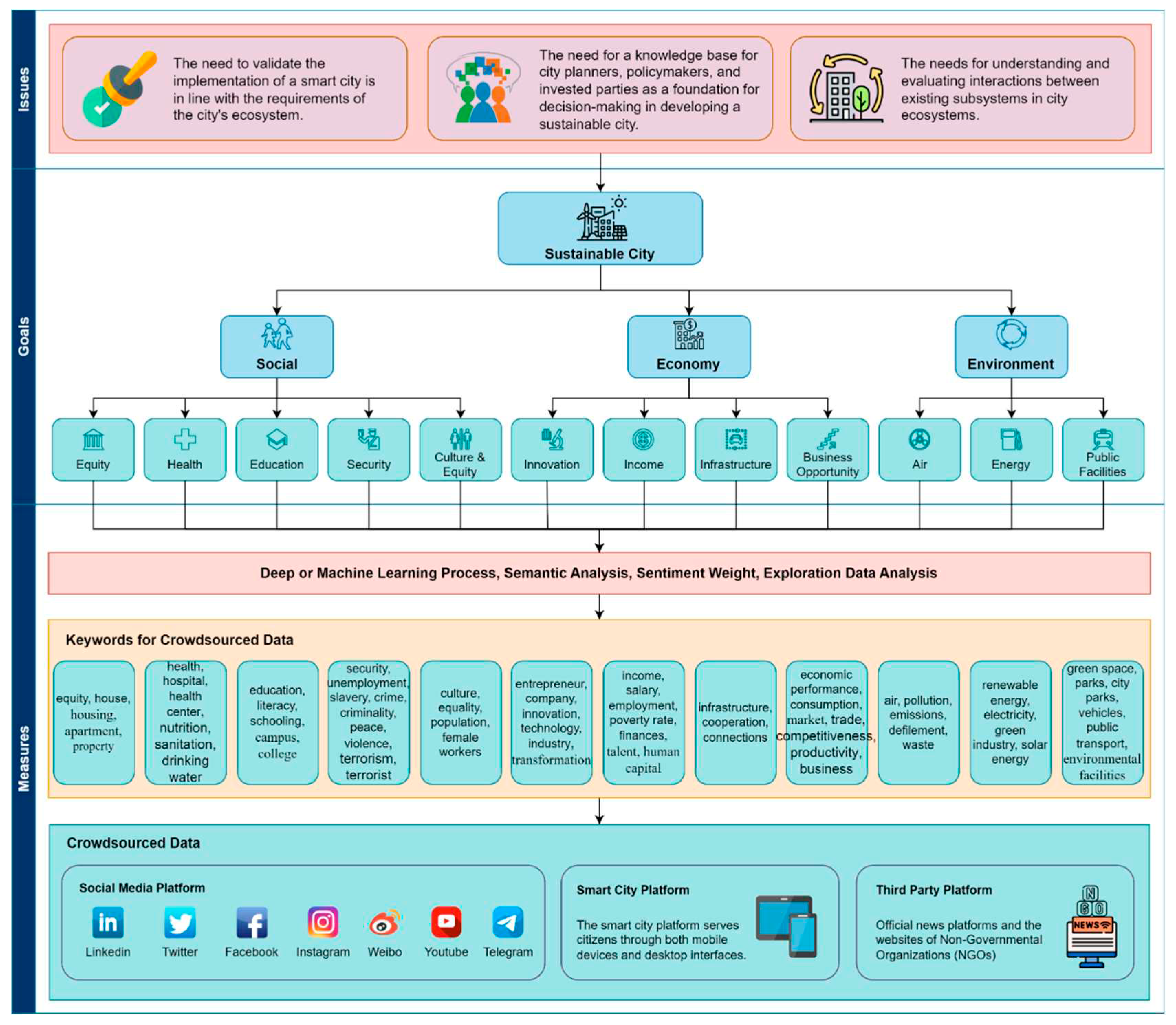

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Significance of Study

2.2. Smart City Assessment

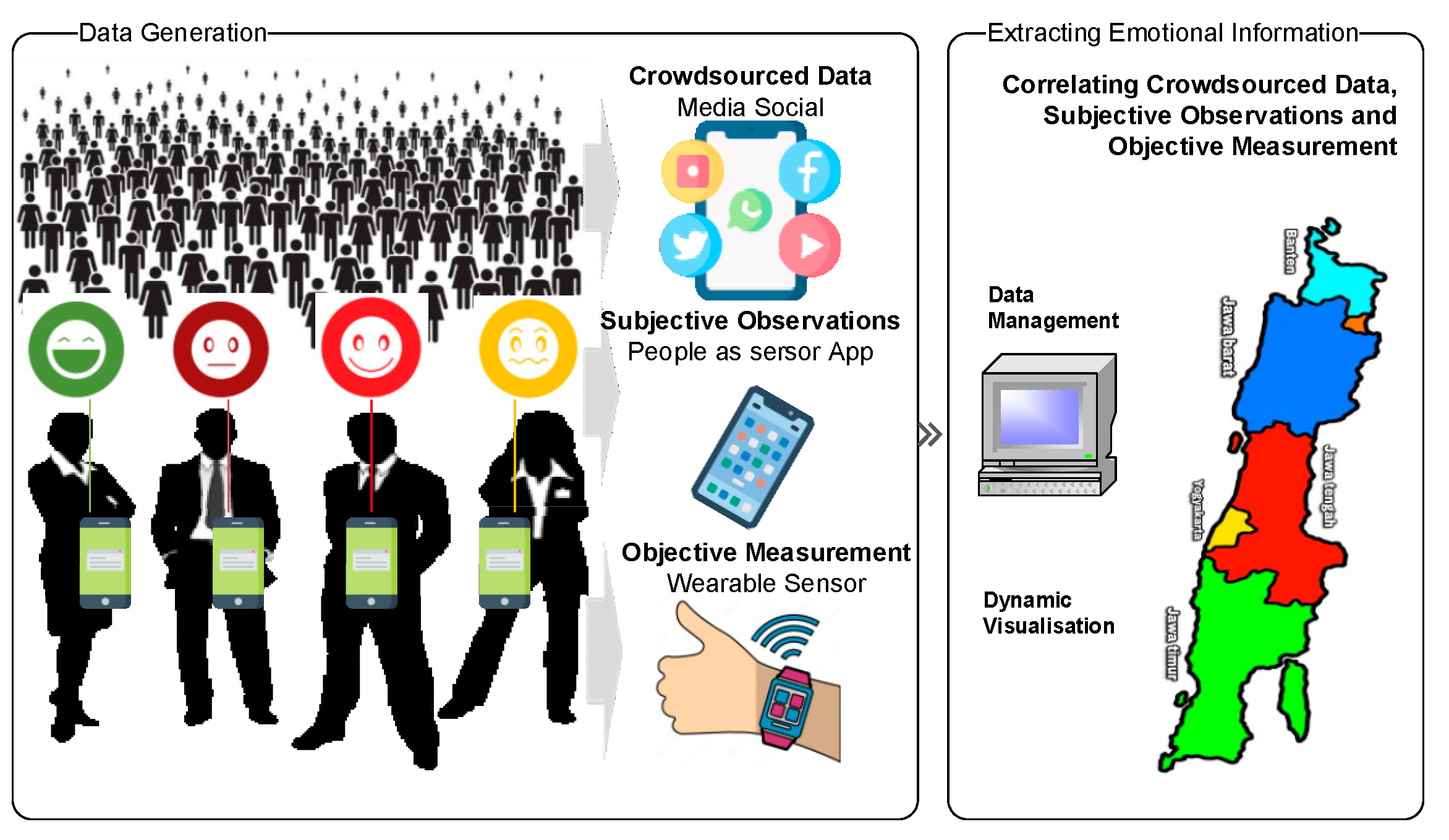

2.3. Crowdsourced Data

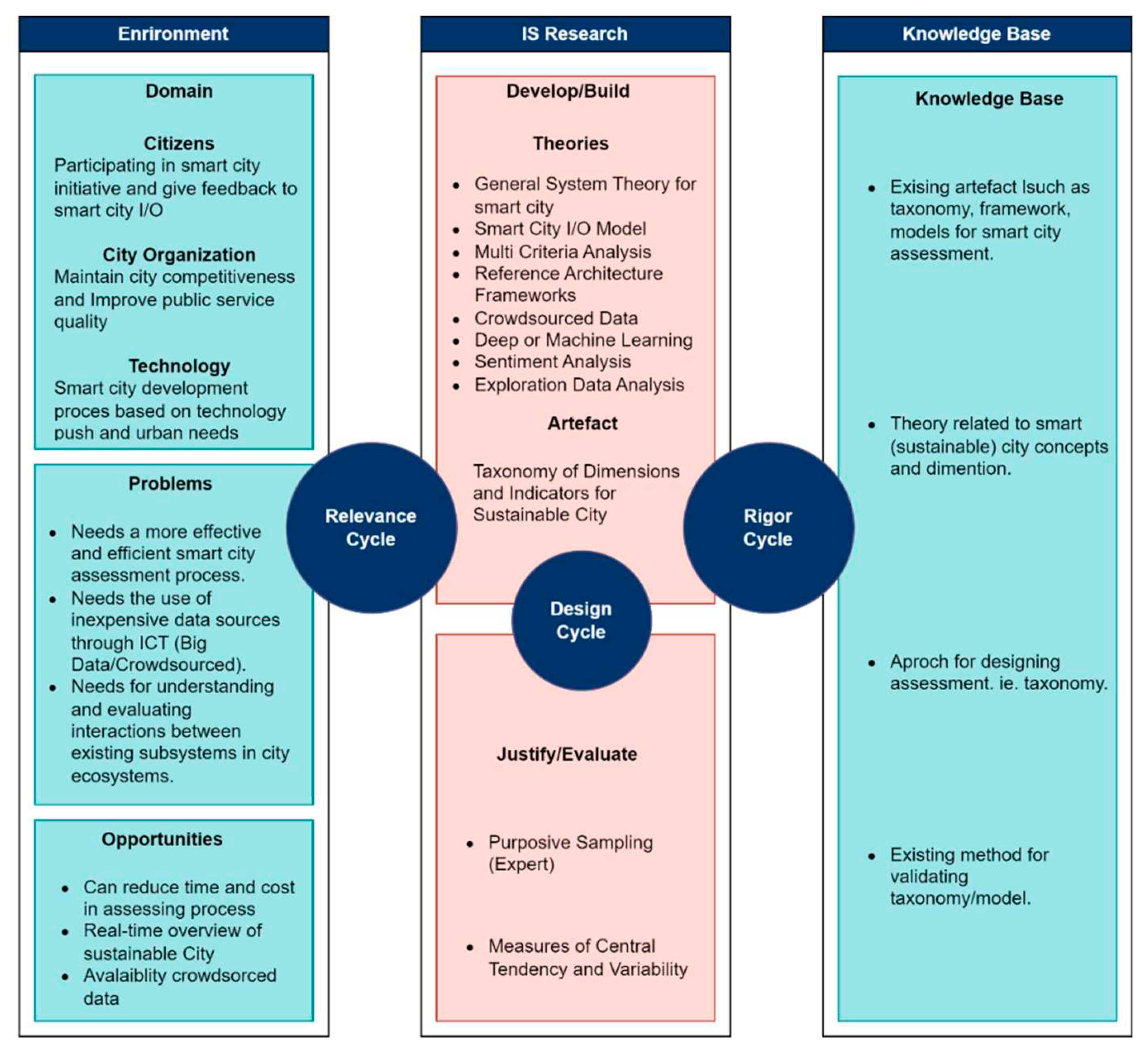

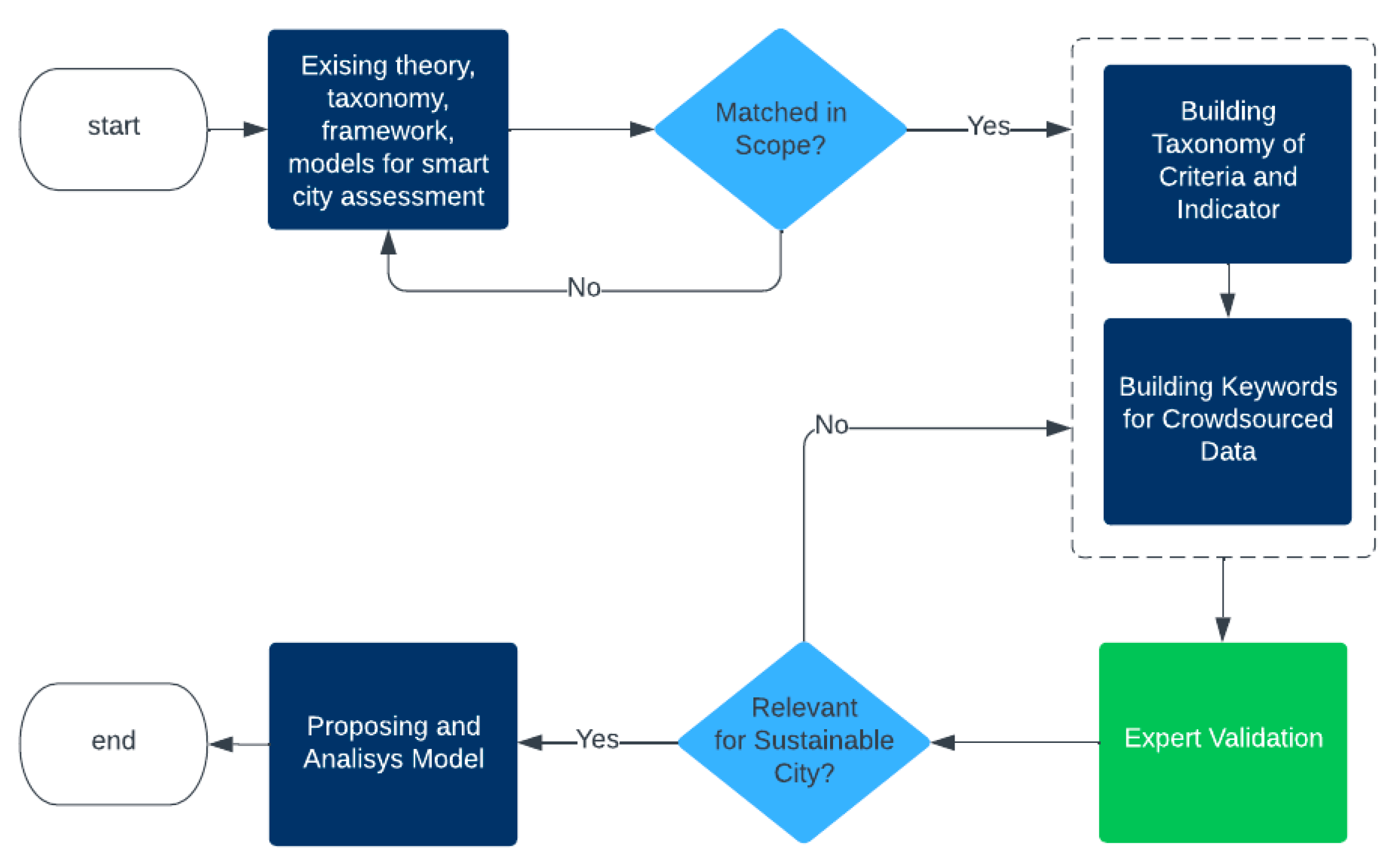

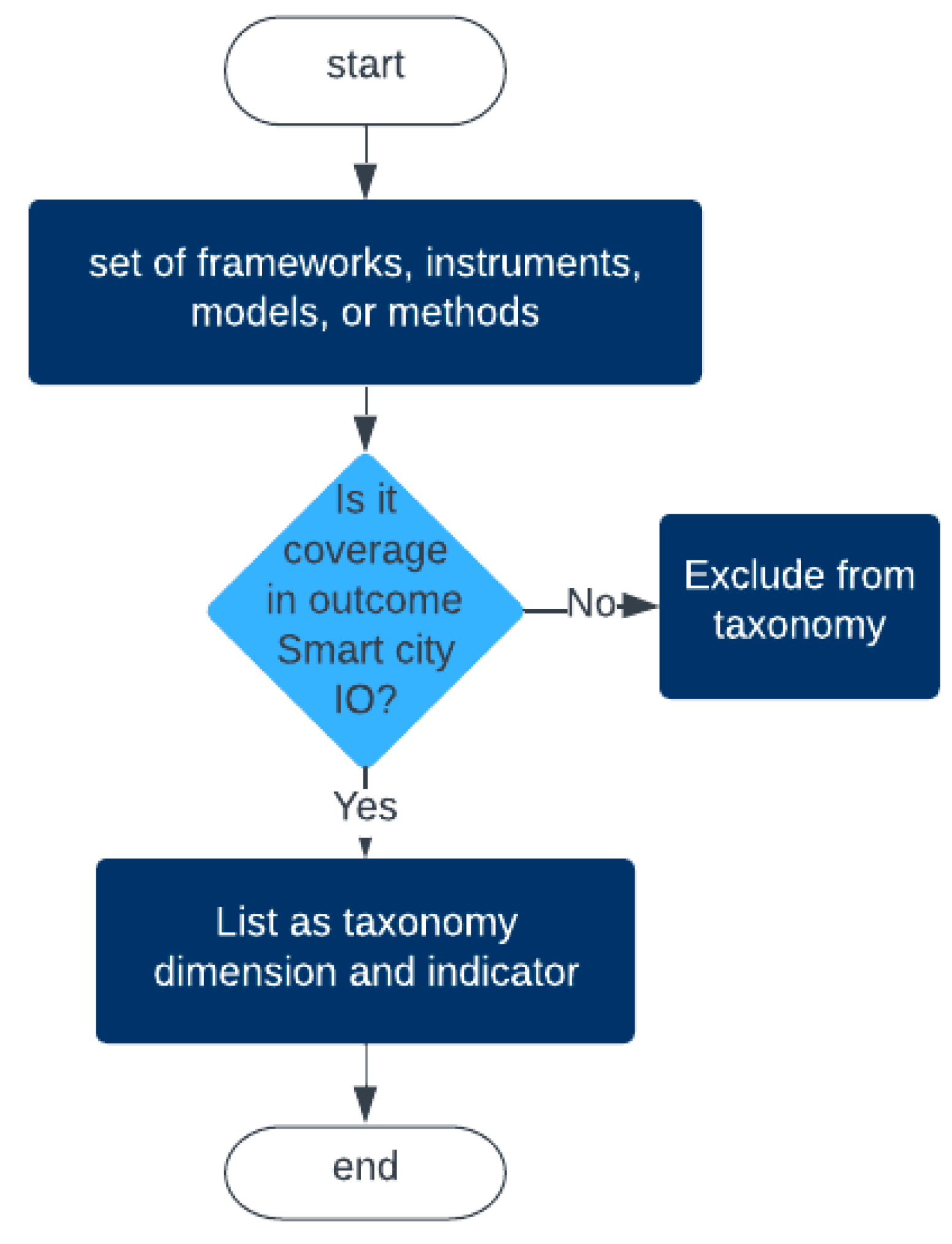

3. Methods

4. Results

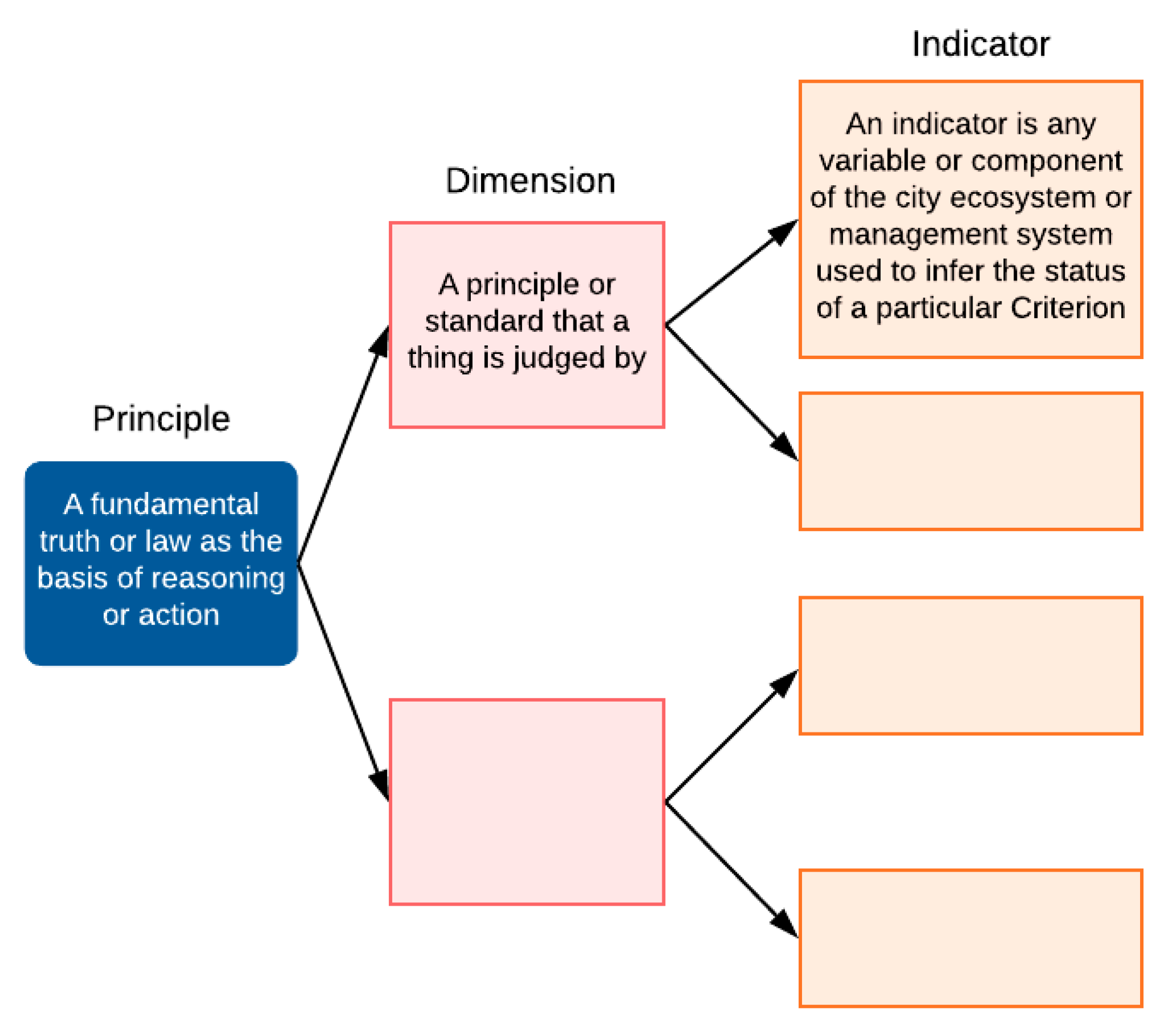

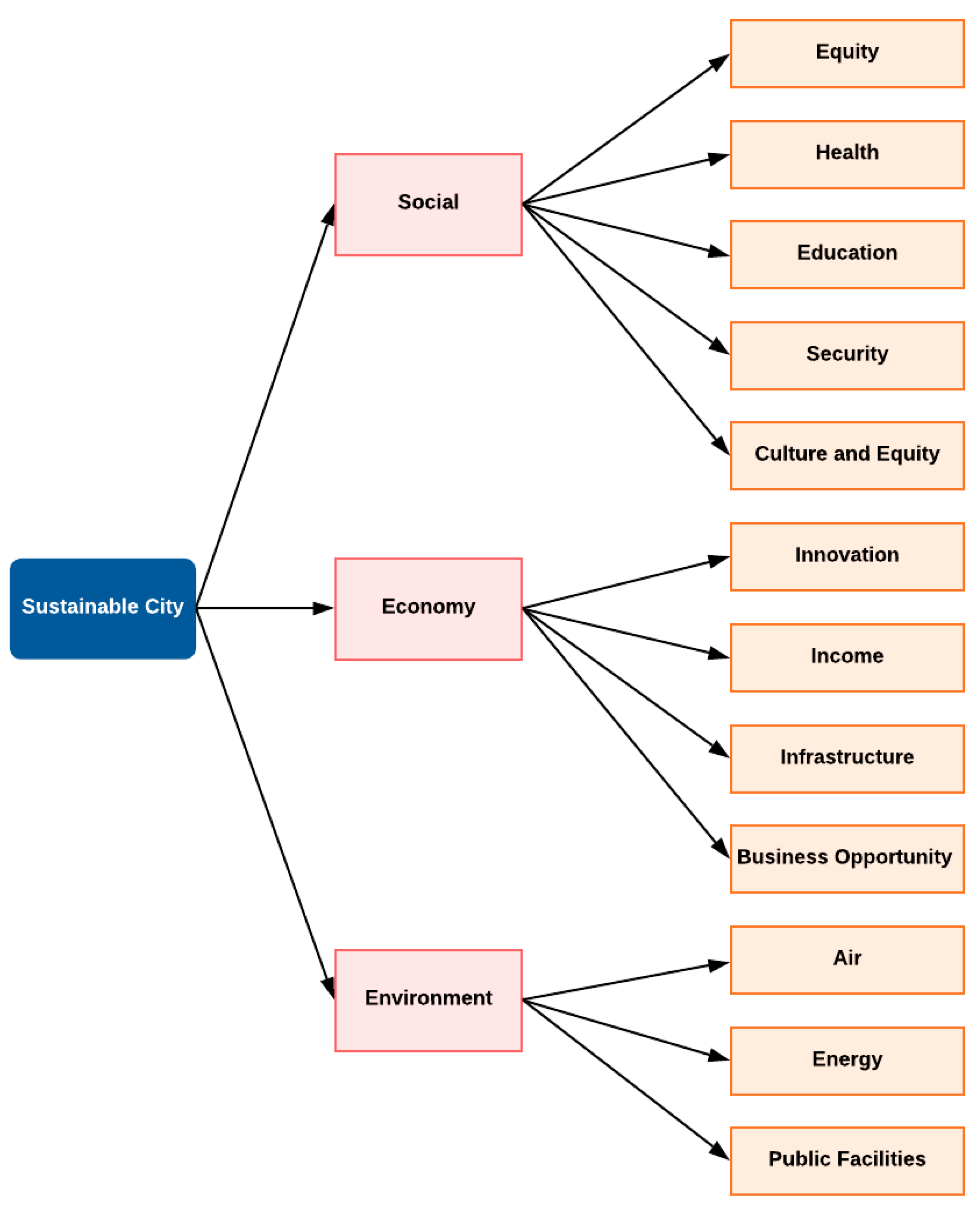

4.1. Taxonomy of Dimensions and Indicators

| No | Ref | Number of Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | Economy | Environemt | ||

| 1 | Smart Sustainable City Indicators [7,8] | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 | Sustainable Development Indicators [8] | 11 | 3 | 6 |

| 3 | Smart City Index Master [8,14] | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | Lisbon ranking for smart sustainable cities [9] | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 5 | Smart city performance indeks [10] | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 6 | IESE Cities in Motion Index 2018 [11] | 13 | 8 | 11 |

| 7 | ITU-T Y.4903/L.1603 [12,57] | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| 8 | Sustainability Perspectives Indicators [13] | 11 | 5 | 13 |

| 9 | Dimensions of the smart city Vienna UT [15] | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| 10 | Characteristics Smart City [16] | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 | Criteria set for evaluating smart cities [17] | 0 | 5 | 7 |

| 12 | China smart city performance [18] | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 13 | Sustainable development of communities [19] | 0 | 5 | 7 |

| 14 | Assess effectiveness of the smart transport [20] | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 15 | Smart City Dimension [21] | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| 16 | City Sustainability Assessment [22] | 12 | 7 | 5 |

| 17 | Smart Sustainable Cities [58] | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| 18 | Global Power City Index 2018 [59] | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| 19 | ITU-T Y.4901/L.1601 [5,60,57] | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| 20 | ITU-T Y.4902/L.1602 [5,57,61] | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Total of Indicators | 80 | 95 | 112 | |

4.2. Keywords of Crowdsourced Data

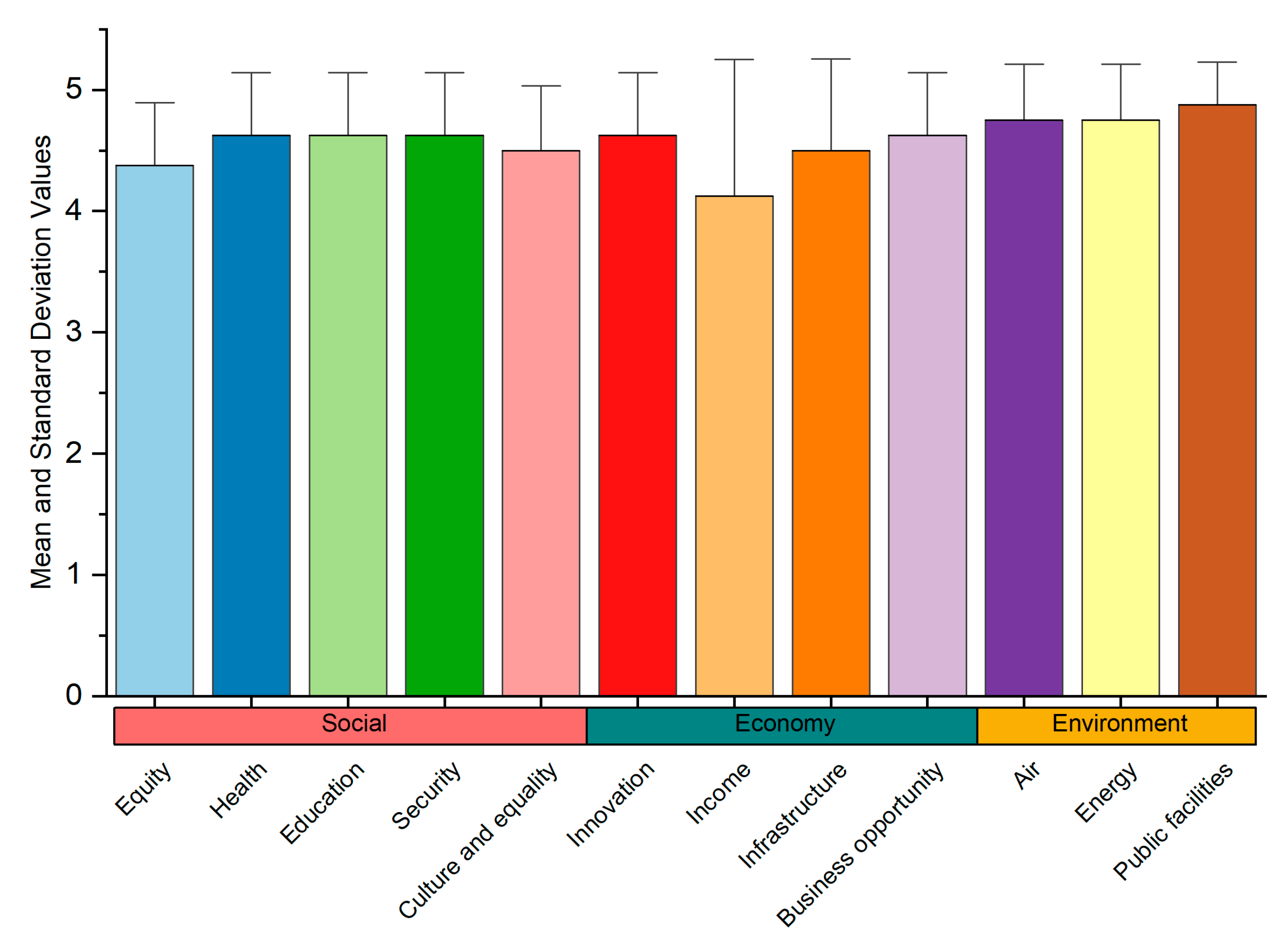

4.3. Experts Validation

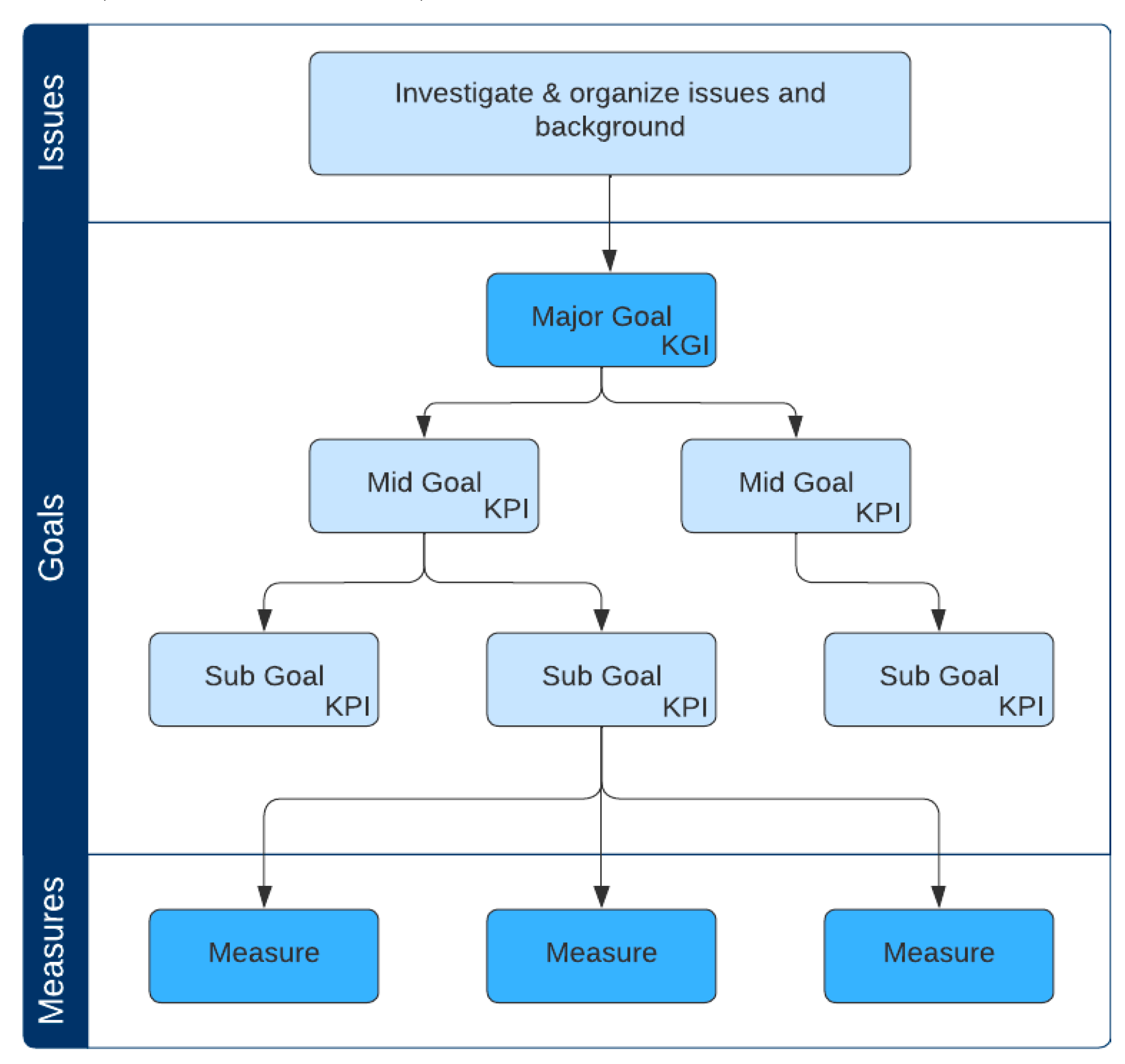

4.4. Sustainable City Assessment Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. Kourtzanidis, K. Angelakoglou, V. Apostolopoulos, P. Giourka, and N. Nikolopoulos, “Assessing impact, performance and sustainability potential of smart city projects: Towards a case agnostic evaluation framework,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 13, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Y. Bayar, H. Guven, H. Badem, and E. Soylu Sengor, “National Smart Cities Strategy and Action Plan: the Turkey’s Smart Cities Approach,” Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci., vol. XLIV-4/W3-, no. October, pp. 129–135, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Lom, “Smart city model based on systems theory,” Int. J. Inf. Manage., vol. 56, no. February 2019, p. 102092, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Aslam, K. Aurangzeb, M. Alhussein, and N. Javaid, “Multiscale modeling in smart cities: A survey on applications, current trends, and challenges,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 78, no. November 2021, p. 103517, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Patrão, P. Moura, and A. T. de Almeida, “Review of Smart City Assessment Tools,” Smart Cities, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1117–1132, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahvenniemi, A. Huovila, I. Pinto-Seppä, and M. Airaksinen, “What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities?,” Cities, vol. 60, pp. 234–245, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Hass, F. Brunvoll, and H. Hoie, “Overview of Sustainable Development Indicators used by National and International Agencies,” OECD Stat. Work. Pap., 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. Pira, “A novel taxonomy of smart sustainable city indicators,” Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Akande, P. Cabral, P. Gomes, and S. Casteleyn, “The Lisbon ranking for smart sustainable cities in Europe,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 44, no. August, pp. 475–487, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Yigitcanlar, K. Degirmenci, L. Butler, and K. C. Desouza, “What are the key factors affecting smart city transformation readiness ? Evidence from Australian cities,” Cities, vol. 120, no. August, p. 103434, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Berrone and J. E. Ricart, IESE Cities in Motion Index 2018, 2018th ed. Barcelona: IESE Business School’s, 2018. [CrossRef]

- ITU-T, “Key performance indicators for smart sustainable cities to assess the achievement of sustainable development goals,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-Y.4903.

- A. J. Benites and A. F. Simões, “Assessing the urban sustainable development strategy: An application of a smart city services sustainability taxonomy,” Ecol. Indic., vol. 127, p. 107734, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Cohen, “Smart city index master indicators survey. Smart cities council.” 2022. [Online]. Available: http://smartcitiescouncil.com/resources/smart-city-index-master-indicators-survey.

- G. Koca, O. Egilmez, and O. Akcakaya, “Evaluation of the smart city: Applying the dematel technique,” Telemat. Informatics, vol. 62, no. June, p. 101625, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Purnomo, Meyliana, and H. Prabowo, “Smart city indicators: A systematic literature review,” J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 161–164, 2016.

- R. M. Kimiya and S. A. Torabi, “Ranking cities based on their smartness level using MADM methods,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 72, no. May, p. 103030, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Shen, Z. Huang, S. Wai, S. Liao, and Y. Lou, “A holistic evaluation of smart city performance in the context of China,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 200, no. November, pp. 667–679, 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Fernandez-anez, G. Velazquez, and F. Perez-prada, “Smart City Projects Assessment Matrix: Connecting Challenges and Actions in the Mediterranean Region,” J. Urban Technol., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 1–25, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Gutman and P. Vorontsova, “Issues of Development of Smart Transport Assessment Indicators,” 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Al Sharif and S. Pokharel, “Smart City Dimensions and Associated Risks: Review of literature,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 77, no. February, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, P. Yi, W. Li, and C. Gong, “Assessment of city sustainability from the perspective of multi-source data-driven,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 70, no. January, p. 102918, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharifi, “A critical review of selected smart city assessment tools and indicator sets,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 233, no. 1 October 2019, pp. 1269–1283, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharifi, “A typology of smart city assessment tools and indicator sets,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 53, no. May, pp. 1–15, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharifi, “A global dataset on tools, frameworks, and indicator sets for smart city assessment,” Data Br., vol. 29, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Dawodu, A. Cheshmehzangi, A. Sharifi, and J. Oladejo, “Neighborhood sustainability assessment tools : Research trends and forecast for the built environment,” Sustain. Futur., vol. 4, no. January, p. 100064, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, X. Li, X. Zhou, and T. Yang, “City Intelligence Quotient Evaluation System Using Crowdsourced Social Media Data : A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta Region , China,” Int. J. Geo-Information, vol. 10, no. 702, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Neirotti, A. De Marco, A. C. Cagliano, G. Mangano, and F. Scorrano, “Current trends in smart city initiatives: Some stylised facts,” Cities, vol. 38, pp. 25–36, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Rochet and F. P. de Villechenon, “System Architecture As A Means To Build An Extended Administration : The Case of Smart Cities,” Puyricard, France, 2014.

- P. B. Checkland and M. G. Haynes, “Varieties of systems thinking: The case of soft systems methodology,” Manag. Control Theory, vol. 3, no. January, pp. 151–159, 1994.

- N. Noori, T. Hoppe, and M. de Jong, “Classifying pathways for smart city development: Comparing design, governance and implementation in Amsterdam, Barcelona, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Garau and V. M. Pavan, “Evaluating urban quality: Indicators and assessment tools for smart sustainable cities,” Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 575, 2018.

- V. Fernandez-Anez, J. M. Fernández-Güell, and R. Giffinger, “Smart City implementation and discourses: An integrated conceptual model. The case of Vienna,” Cities, vol. 78, pp. 4–16, 2018.

- A. K. Debnath, H. C. Chin, M. M. Haque, and B. Yuen, “A methodological framework for benchmarking smart transport cities,” Cities, vol. 37, pp. 47–56, 2014.

- A. Mohan, G. Dubey, F. Ahmed, and A. Sidhu, “Smart Cities Index: A Tool for Evaluating Cities,” Indian School of Business: Hyderabad. Indian School of Business-Hyderabad, 2020.

- A. S. Caird, L. Hudson, and G. Kortuem, “A tale of evaluation and reporting in UK smart cities,” Open Univ. Milt. Keynes, 2016.

- R. Giffinger, G. Haindlmaier, and H. Kramar, “The role of rankings in growing city competition,” Urban Res. Pract., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 299–312, 2010.

- A. Akande, P. Cabral, and S. Casteleyn, “Assessing the gap between technology and the environmental sustainability of European cities,” Inf. Syst. Front., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 581–604, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Crooks et al., “Crowdsourcing urban form and function,” Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci., vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 720–741, 2015. 0.1080/13658816.2014.977905.

- Y. Long and L. Liu, “Transformations of urban studies and planning in the big/open data era: a review,” Int. J. Image Data Fusion, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 295–308, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Niu and E. A. Silva, “Crowdsourced Data Mining for Urban Activity: Review of Data Sources, Applications, and Methods,” J. Urban Plan. Dev., vol. 146, no. 2, p. 04020007, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Havinga, P. W. Bogaart, L. Hein, and D. Tuia, “Defining and spatially modelling cultural ecosystem services using crowdsourced data,” Ecosyst. Serv., vol. 43, no. March, p. 101091, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. vom Brocke, A. Hevner, and A. Maedche, “Introduction to Design Science Research,” Cases, no. September, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. T. March and V. C. Storey, “Design science in the information systems discipline: An introduction to the special issue on design science research,” MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst., vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 725–730, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Hevner and S. Chatterjee, Design Research in Information Systems. London: Springer, 2010.

- N. Ahmad, D. Berg, and G. R. Simons, “The integration of analytical hierarchy process and data envelopment analysis in a multi-criteria decision-making problem,” Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 263–276, 2006. [CrossRef]

- . N. Noori, M. de Jong, M. Janssen, D. Schraven, and T. Hoppe, “Input-Output Modeling for Smart City Development,” J. Urban Technol., vol. 28, no. 1–2, pp. 71–92, 2020. [CrossRef]

- . G. A. Mendoza, P. Macoun, R. Prabhu, D. Sukadri, H. Purnomo, and H. Hartanto, Guidelines for Applying Multi-Criteria Analysis to the Assessment of Criteria and Indicators. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 1999. [CrossRef]

- A. Saihi, M. Ben-Daya, and R. As’ad, “An Investigation of Sustainable Maintenance Performance Indicators: Identification, Expert Validation and Portfolio of Future Research,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, no. November, pp. 124259–124276, 2022. [CrossRef]

- . Day and M. Bobeva, “A generic toolkit for the successful management of delphi studies,” Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 103–116, 2005.

- R. Helmy et al., “ESPACOMP Medication Adherence Reporting Guidelines (EMERGE): A reactive-Delphi study protocol,” BMJ Open, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1–7, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Nordin, B. M. Deros, D. A. Wahab, and M. N. A. Rahman, “Validation of lean manufacturing implementation framework using delphi technique,” J. Teknol. (Sciences Eng., vol. 59, no. SUPPL.2, pp. 1–6, 2012.

- Government Japan, Smart City Reference Architecture White Paper Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program, vol. March. Government Japan, 2020.

- P. James, M. Holden, M. Lewin, and L. Neilson, “Managing metropolises by negotiating urban growth,” in Institutional and social innovation for sustainable urban development, Routledge, 2013, pp. 233–248.

- J. Liu et al., “Analysis of sustainability of Chinese cities based on network big data of city rankings,” Ecol. Indic., vol. 133, no. October, p. 108374, 2021. [CrossRef]

- U. Ependi, A. F. Rochim, and A. Wibowo, “Smart City Assessment for Sustainable City Development on Smart Governance: A Systematic Literature Review,” 2022 Int. Conf. Decis. Aid Sci. Appl. DASA 2022, pp. 1088–1097, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Huovila, P. Bosch, and M. Airaksinen, “Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for Smart sustainable cities: What indicators and standards to use and when?,” Cities, vol. 89, no. January, pp. 141–153, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, P. S. W. Fong, S. Dai, and Y. Li, “Towards sustainable smart cities: An empirical comparative assessment and development pattern optimization in China,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 215, pp. 730–743, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Takenaka and H. Ichikawa, “Global Power City Index 2018,” London, New York, Toko, Paris, Singapore, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://mori-m-foundation.or.jp/pdf/GPCI2018_summary.pdf.

- ITU-T, “Key Performance Indicators Related to The Use of Information and Communication Technology In Smart Sustainable Cities,” 2016.

- ITU-T, “Key performance indicators related to the sustainability impacts of information and communication technology in smart sustainable cities,” 2016.

- C.-L. Goi, “The impact of technological innovation on building a sustainable city,” Int. J. Qual. Innov., vol. 3, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ş. Y. Balaman, “Sustainability Issues in Biomass-Based Production Chains,” Decis. Biomass-Based Prod. Chain., pp. 77–112, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Del Río Castro, M. C. González Fernández, and Á. Uruburu Colsa, “Unleashing the convergence amid digitalization and sustainability towards pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A holistic review,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 280, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. P. Bithas and M. Christofakis, “Environmentally sustainable cities. Critical review and operational conditions,” Sustain. Dev., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 177–189, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tomor, A. Meijer, A. Michels, and S. Geertman, “Smart Governance For Sustainable Cities: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review,” J. Urban Technol., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 3–27, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Castelnovo, G. Misuraca, and A. Savoldelli, “Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making,” Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev., vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 724–739, 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Webster and C. Leleux, “Smart governance: Opportunities for technologically-mediated citizen co-production,” Inf. Polity, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 95–110, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Tan and A. Taeihagh, “Smart city governance in developing countries: A systematic literature review,” sustainability, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 899, 2020.

- G. Viale Pereira, M. A. Cunha, T. J. Lampoltshammer, P. Parycek, and M. G. Testa, “Increasing collaboration and participation in smart city governance: a cross-case analysis of smart city initiatives,” Inf. Technol. Dev., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 526–553, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Joia and A. Kuhl, “Smart city for development: A conceptual model for developing countries,” in International conference on social implications of computers in developing countries, 2019, pp. 203–214.

- M.J. Nikki Han and M. J. Kim, “A critical review of the smart city in relation to citizen adoption towards sustainable smart living,” Habitat Int., vol. 108, no. January, p. 102312, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Chang and M. K. Smith, “Residents’ Quality of Life in Smart Cities: A Systematic Literature Review,” Land, vol. 12, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, W. Widodo, and H. Amani, “Indicators to measure a smart education: An Indonesian perspective,” Proc. Int. Conf. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag., vol. 2018-March, pp. 3486–3495, 2018.

- B. D. Tampubolon, A. B. Mulyono, F. Isharyadi, E. H. Purwanto, W. C. Anggundari, and Gensly, “Indicator Analysis Of Smart City Standard Sni ISO 37122 Plays A Role In The Covid-19 Pandemic,” Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. - ISPRS Arch., vol. 46, no. 4/W5-2021, pp. 523–528, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Šulyová and J. Vodák, “The impact of cultural aspects on building the smart city approach: Managing diversity in Europe (London), North America (New York) and Asia (Singapore),” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 22, pp. 1–11, 2020. 0.3390/su12229463.

- M. Duygan, M. Fischer, R. Pärli, and K. Ingold, “Where do Smart Cities grow? The spatial and socio-economic configurations of smart city development,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 77, no. April 2021, 2022. 0.1016/j.scs.2021.103578.

- Z. Chen and J. Cheng, “Economic Impact of Smart City Investment: Evidence from the Smart Columbus Projects,” J. Plan. Educ. Res., vol. 43, no. 4, p. 0739456X221129173, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Vishnivetskaya and E. Alexandrova, “‘Smart city’ concept. Implementation practice,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 497, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Komninos, C. Kakderi, A. Panori, and P. Tsarchopoulos, “Smart City Planning from an Evolutionary Perspective,” J. Urban Technol., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 3–20, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Kaginalkar, S. Kumar, P. Gargava, and D. Niyogi, “Stakeholder analysis for designing an urban air quality data governance ecosystem in smart cities,” Urban Clim., vol. 48, no. January, p. 101403, 2023. [CrossRef]

- 82. M. Y. Salman and H. Hasar, “Review on environmental aspects in smart city concept: Water, waste, air pollution and transportation smart applications using IoT techniques,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 94, no. December 2022, p. 104567, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. G. M. Almihat, M. T. E. Kahn, K. Aboalez, and A. M. Almaktoof, “Energy and Sustainable Development in Smart Cities: An Overview,” Smart Cities, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1389–1408, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Razmjoo, A. H. Gandomi, M. Pazhoohesh, S. Mirjalili, and M. Rezaei, “The key role of clean energy and technology in smart cities development,” Energy Strateg. Rev., vol. 44, no. August, p. 100943, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, “Research on Smart City Environment Design and Planning Based on Internet of Things,” J. Sensors, vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. O. Alshammari, “Smart City Public Transport Remodel Urban Biodiversity Management,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 1026, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Burlacu, R. G. Boboc, and E. V. Butilă, “Smart Cities and Transportation: Reviewing the Scientific Character of the Theories,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 13, 2022. 0.3390/su14138109.

| No | Position | Country | Expertise | Experince |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Associate Professor | Indonesia | Green it, e-government, smart cities, e-learning, and IT public services | 10-15 years |

| 2 | Professor | Indonesia | Computer vision, information systems, human factors, and smart cities. |

>20 years |

| 3 | Associate Professor | Indonesia | open government data, smart cities, network secuity, and digital forensics investigation. | 15-20 years |

| 4 | Associate Professor | Indonesia | open data government, smart cities, data mining, information system, and technology adoption. | 15-20 years |

| 5 | Associate Professor | Malaysia | user experience, human computer interaction, sustainability, and gerontechnology. | 5-10 years |

| 6 | Associate Professor | Malaysia | information system, project management, and sustainable governance. |

10-15 years |

| 7 | Professor | Indonesia | smart system platform and ecosystem, IT architecture and governance, and smart cities. | >20 years |

| 8 | Professor | Malaysia | IT governance, urban development, social media, data analytics, and fintech. |

>20 years |

| Indicators | Thema |

|---|---|

| Assets equity [7,8]. Housing [7,8,9,12,5,60,57,61,13,10] Social inclusion [9,12,5,60,57,61] Price of property [11] |

Equity |

| Health [7,8,9,11,12,5,60,57,61,13] Health Status [10] Hospitals [11] Mortality [11,13] Nutritional regime [13] Sanitation conditions [13] Drinking water [13] |

Health |

| Education [7,8,9,12,5,60,57,61] Educational level [13] Literacy [13] |

Education |

| Security [7,8,10] Population [7,8,13] Safety [9,12,5,60,57,61,10] Crime rate [11] Unemployment [11] Global Peace Indeks [11] Global Slavery Indeks [11] Government response to situations of slavery [11] Terrorism [11] Violence [13] |

Security |

| Culture [9,12,5,60,57,61] Female workers [11] Happiness indeks [11] Gender equality [13] |

Culture and Equality |

| Indicators | Thema |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship and innovation [7,8,14,15,16,17,9,18,12,57,5,60,61] Ability to transform [15] Innovation Industries [10] Innovative spirit [15,19,21] Innovative output [58] Entrepreneurial enterprises [58] |

Innovation |

| Availability of employment finding services [17] Employment [17,9,18,12,57,5,60,61] GDP estimate [11] GDP [11] GDP per capita [11,18] Labour Force Participation [10] Talent Pool [10] Human Capital [59] |

Income |

| Local and global connection [7,8,14,19] ICT Infrastructure [9,12,57,5,60,61] Physical infrastructure [9,12,57,5,60,61] Headquarters [11] Use of information and communication technologies [21] Global interconnectedness [58] |

Infrastructure |

| Productivity [7,8,14,15,16,9,11,19,10,58,12,57,5,60,61] Trade [9,12,57,5,60,61] Economic image and trademarks [15] Flexibility of labor market international embeddedness [15,19] Economic performance [13] Trading [13,9] Financial status [13] material consumption [13] Energy consumption [13] Economic Vitality and Planning [16] Online services made it easy to start a new business [17] E-commerce companies [17] Time required to start a business [11] Ease of starting a business [11] Motivation for early-stage entrepreneurial activity[11] Competitiveness [21] Socially responsible use of resources [21] Market size [59] Market Attractiveness [59] Business Environment [59] Ease of Doing Business [59] Public sector [12,57,5,60,61] |

Business Opportunity |

| Indicators | Theme |

|---|---|

| PM2.5 and PM10 [11] Pollution [15,11] Air quality [17,59,12,57,5,60,61,13] Availability and quality of apps for air pollution monitoring [17,16,19] Air pollution indeks [18] Volume of CO2 emissions [20,11] Pollution control [21] Quality of air and water [21,9,11,13,12,57,5,60,61] Monitoring emissions [21] Industrial wastewater [22] Industrial waste gas emissions [22] Industrial solid waste discharge [22,11] Discharge of hazardous waste [22] Natural Environment [59] Noise [9,12,57,5,60,61] |

Air |

| Recycling [17] Renewable energy production [17] Energy consumption [17] Energy management [21,16] Energy [9,10,12,57,5,60,61] Energy Efficiency [19] |

Energy |

| Attractivity of natural conditions [15] Sustainable resource management [15] Environmental protection [15] Basic sanitation quality [17] Smart building and renovation [19,10] Urban and Resource planning [19] Expenses for urban amenities [20] Green area per capita [18,13] Level of waste reuse and recycle [18] Improvements of waste discarding [21] House and facility management [21] Vehicle for city environmental [22,10] Environmental Quality/Sustainability [16,12,57,5,60,61] |

Public Facilities |

| Indicators | Keywords for Crowdsourced Data |

|---|---|

| Equity | equity, house, housing, apartment, property |

| Health | health, hospital, health center, nutrition, sanitation, drinking water |

| Education | education, literacy, schooling, campus, college |

| Security | security, unemployment, slavery, crime, criminality, peace, violence, terrorism, terrorist, terror |

| Culture and equality | culture, equality, population, female workers |

| Innovation | entrepreneur, company, innovation, technology, industry, transformation |

| Income | income, salary, employment, poverty rate, finances, talent, human capital |

| Infrastructure | infrastructure, cooperation, connections |

| Business opportunity | economic performance, consumption, market, trade, competitiveness, productivity, business |

| Air | air, pollution, emissions, defilement, waste |

| Energy | renewable energy, electricity, green industry, solar energy |

| Public facilities | green space, parks, city parks, vehicles, public transport, environmental facilities (equipment) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).