Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

05 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

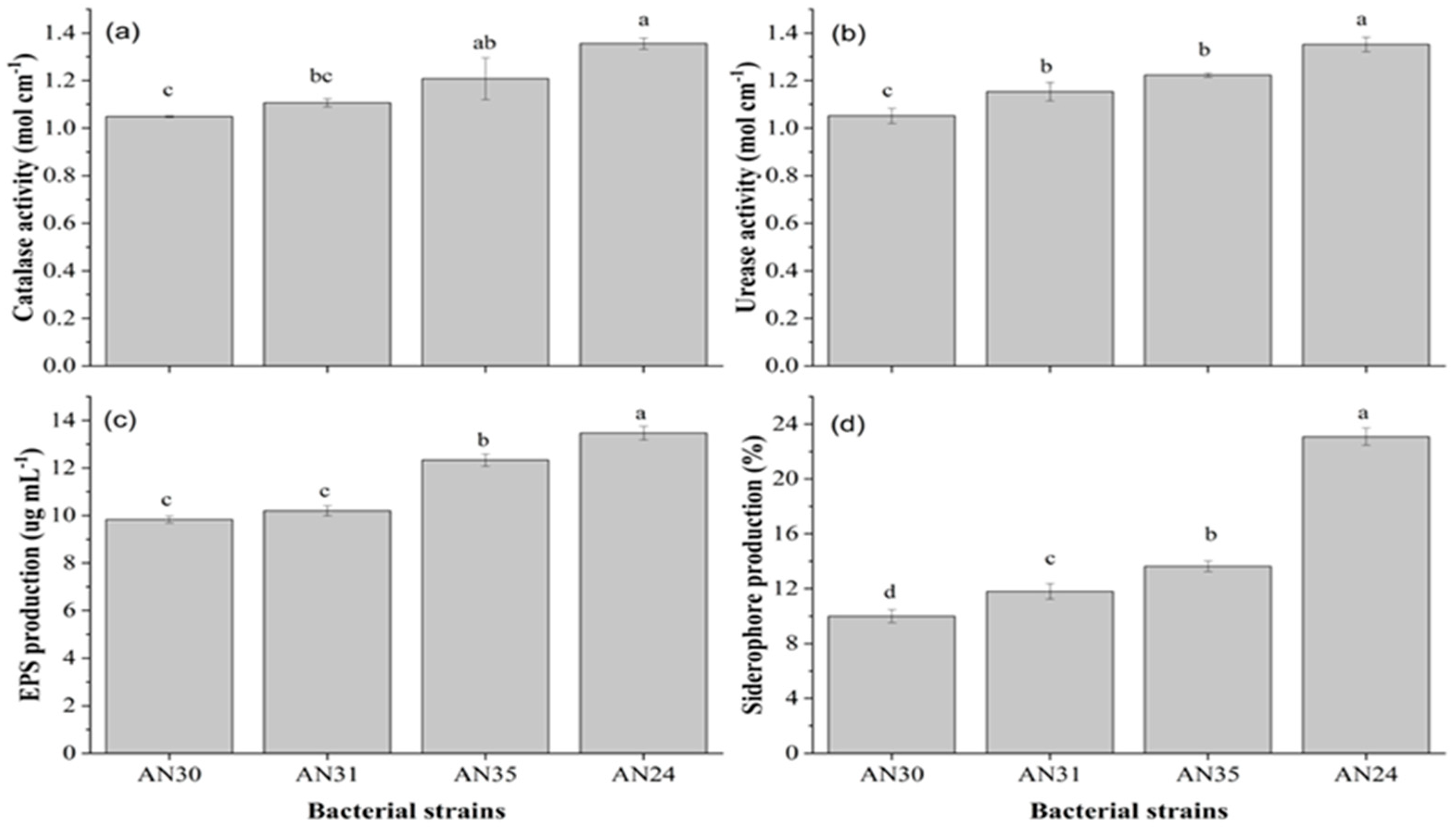

2.1. Biochemical characterization of Bacillus strains

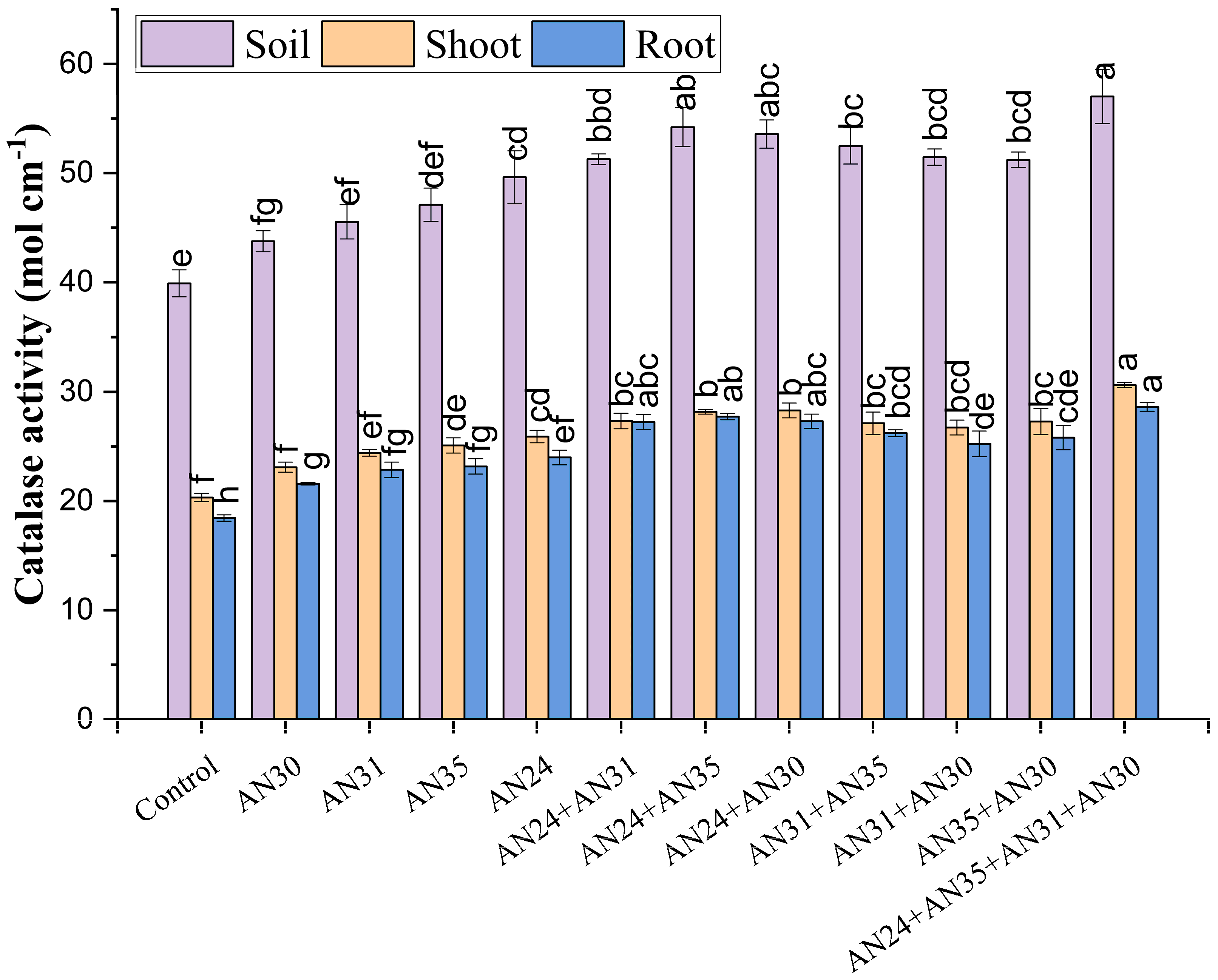

2.2. Effect of catalase-producing Bacillus strains to improve catalase activity in soil and plant

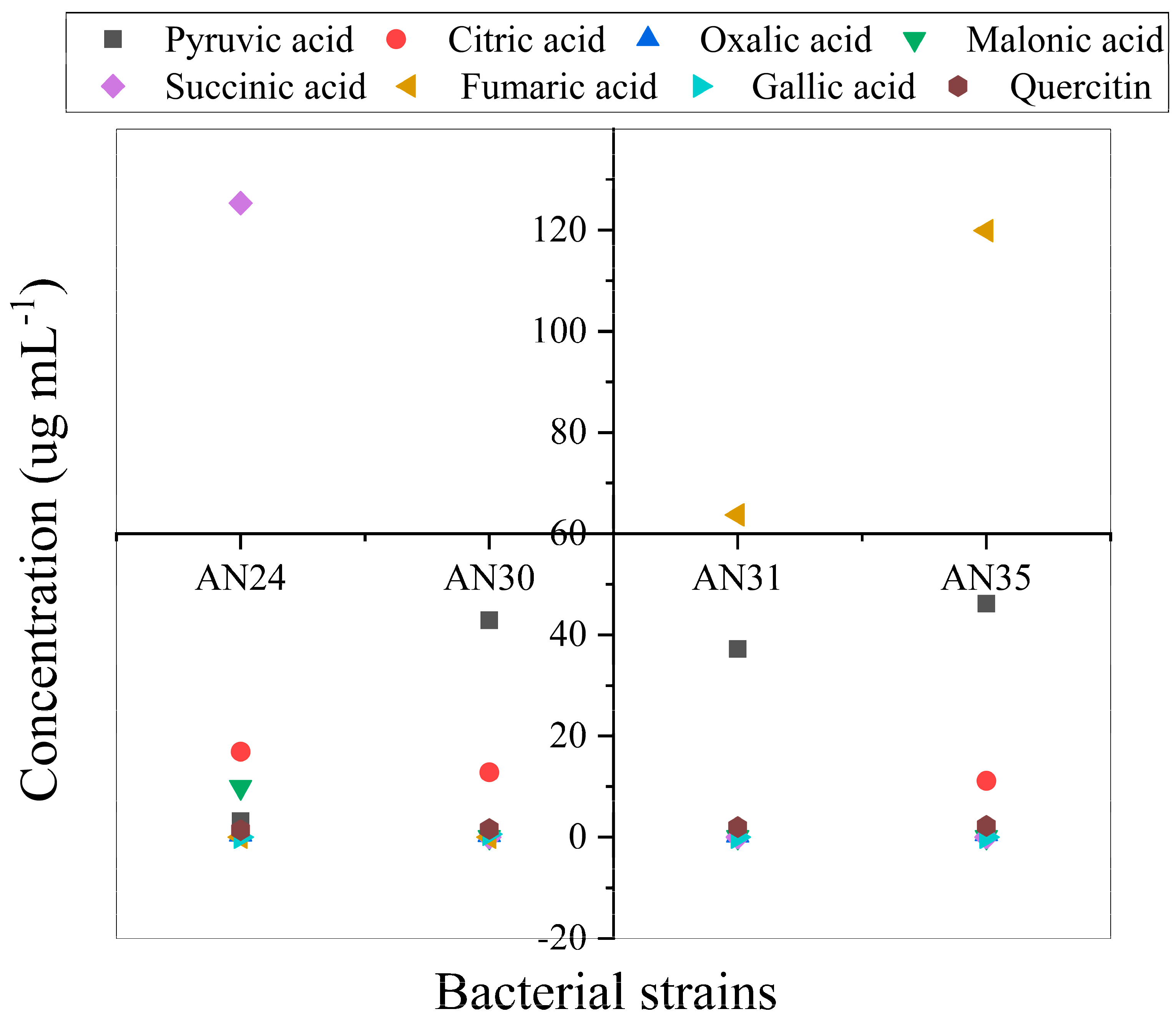

2.3. Organic acid determination in bacterial culture

2.4. Plant growth promotion by the application of catalase-producing Bacillus strains

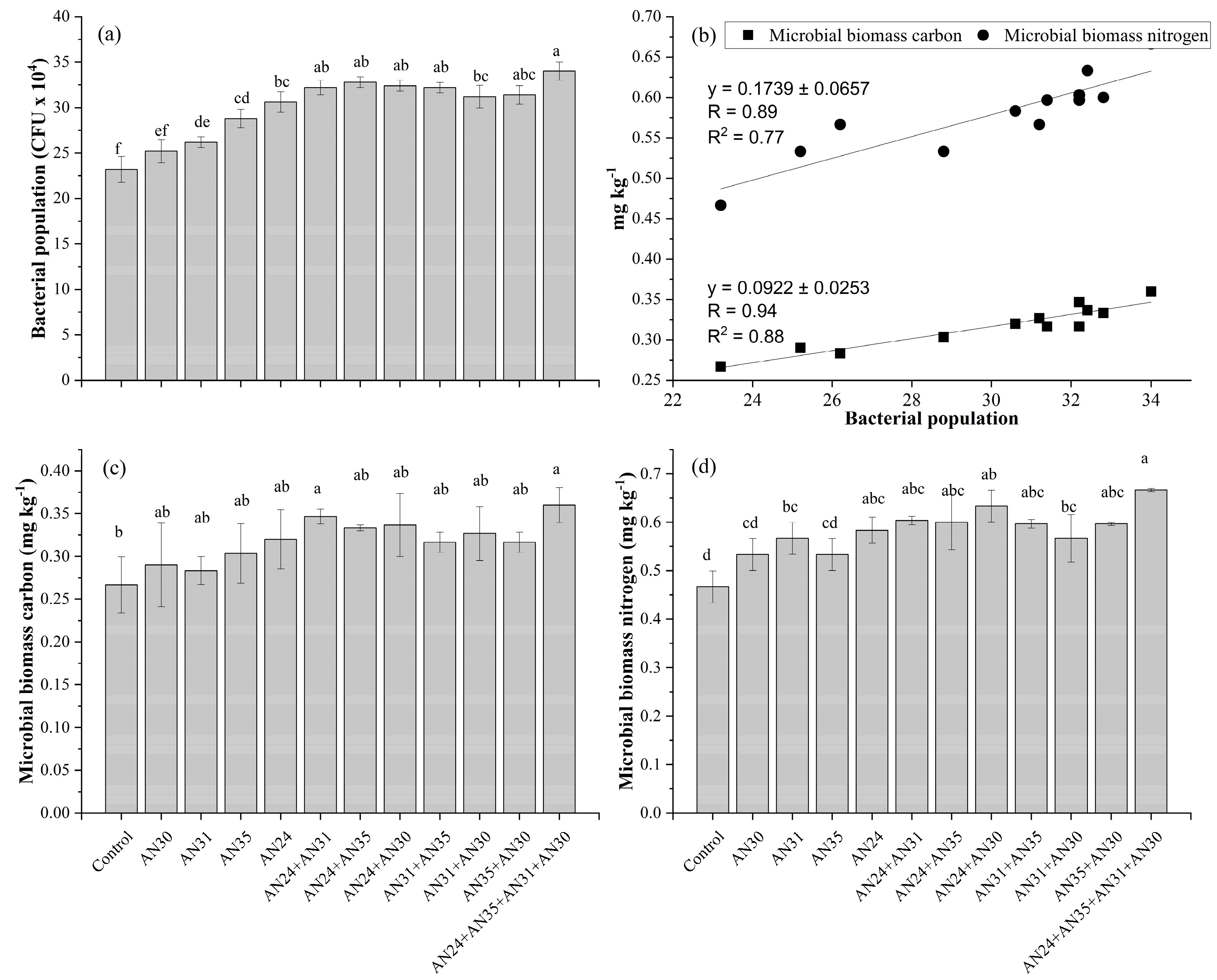

2.5. Effect of Bacillus strains with catalase activity on soil biological properties

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Quantitative characterization of Bacillus strains:

4.2. Biochemical quantification of strains

4.3. Determination of organic acids

4.4. In vitro rice growth promotion characterization of catalase producing Bacillus strains

4.5. Postharvest soil analysis

4.6. Statistical analysis:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thangaraj, B.; Solomon, P.R. Immobilization of lipases–A review. Part I. Enzyme Immobilization. Chem. Bio. Eng. Reviews. 2019, 6, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age- Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, http. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C. Redox regulated peroxisome homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simanjuntak, E.; Zulham. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and free radical. Jurnal Keperawatan dan Fisioterapi (JKF) 2020, 2, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Chaudhary, N.; Singh, N. K. Role of soluble sugars in metabolism and sensing under abiotic stress. Springer, Cham Plant Grow Regul. 2021, 305-334.

- Johnson, L. A.; Hug, L. A. Distribution of reactive oxygen species defense mechanisms across domain bacteria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 140, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Stress-triggered redox signaling: What’s in pROSpect? Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Tiwari, A.; Ghosh, P.; Arora, K.; Sharma, S. Enhanced lignin degradation of paddy straw and pine needle biomass by combinatorial approach of chemical treatment and fungal enzymes for pulp making. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 368, 128314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. H. Xenobiotic Metabolic Enzymes: Bioactivation and Antioxidant Defense, Cham: Switzerland, Springer, 2020; pp. 221-234.

- Ighodaro, O. M.; Akinloye, O. A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade, A.O.; Mabinya, L.V.; Okoh, A.I.; Nwdo, U.U. Studies on peroxidase production and detection of Sporotrichum thermophile-like catalase-peroxidase gene in a Bacillus species isolated from Hogsback Forest reserve, South Africa. Heliyon 2019, 5, e03012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluter, U.; Bouvier, J.W.; Guerreiro, R.; Malisic, M.; Kontny, C.; Westhoff, P.; Weber, A. P. M. Brassicaceae display diverse photorespiratory carbon recapturing mechanisms. Bio Rxiv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhut, M.; Roell, M.S.; Weber, A. P. Mechanistic understanding of photorespiration paves the way to a new green revolution. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernie, A. R.; Bauwe, H. Wasteful, essential, evolutionary stepping stone? The multiple personalities of the photorespir-atory pathway. The Plant J. 2020, 102, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C. P.; Filippis, D. L.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. M.; Ozturk, V.; Altay, M.; Lao, T. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: a review. Bot. Rev. 2021, 87, 421–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, F. A. Photorespiration in the context of Rubisco biochemistry, CO2 diffusion and metabolism. Plant J. 2020, 101, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Hu, H.; Fan, B.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Z. Biosynthesis and roles of salicylic acid in balancing stress response and growth in plants. Inter. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.R.; Mukta, R.H.; Islam, M.A.; Hud, A.N. Insight into Citric Acid-Induced Chromium Detoxification in Rice (Oryza Sativa. L). Int. J. Phytoremediation 2019, 21, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahjib, U.A.M.; Zahan, M. I.; Karim, M. M.; Imran, S.; Hunter, C. T.; Islam, M. S.; Murata, Y. Citric acid-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D. K; Kasotia, A; Jain, S; Vaishany, A; Kumari, S; Sharma, K.P; Varma, A. Bacterial-mediated tolerance and resistance to plants under abiotic and biotic stresses. J. Plant Grow Regul. 2016, 35, 276–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Khan, F.; Cao, W.; Wu, L.; Geng, M. Seed priming alters the production and detoxifcation of reactive oxygen intermediates in rice seedlings grown under sub-optimal temperature and nutrient supply. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 439 https://doi org/103389/fpls201600439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibián, M. E.; Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Mejía, A.; Barrios, G. J. Penicillin and cephalosporin biosyntheses are also regulated by reactive oxygen species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1773–1783 http://. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, I.; Yoshida, S.; Hiraga, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Kimura, Y.; Oda, K. Biodegradation of PET. Current status and application aspects. Acs Catal. 2019, 9, 4089–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Siani, R.; Sharma, J.C. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and their biological properties for soil enrichment and growth promotion. J. Plant Nutr. 2021, 45, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.; Khadka, R.; Doni, F.; Uphoff, N. Benefits to plant health and productivity from enhancing plant microbial symbionts. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 610065 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, B. M.; Ahmed A., E.; Ibrahim, H.M. Isolation & identification of catalase producing Bacillus spp: A comparative study. Int. J. Adv Res. 2017, 4, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Philibert, T.; Rao, Z.; Yang, T.; Zhou, J.; Huang, G.; Irene, K.; Samuel, N. Heterologous expression and characterization of a new heme-catalase in Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 43, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B. O.; Bai, Z.; Bao, L.; Xue, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y. Bacillus subtilis biofertilizer mitigating agricultural ammonia emission and shifting soil nitrogen cycling microbiomes. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbu, P.; Kang, C. H.; Shin, Y.J.; So, J.S. Formations of calcium carbonate minerals by bacteria and its multiple applications. Springer plus 2016, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.A; Pan, B.; Qin, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lichtfouse, E.; Usman, M.; Wang, C. A review on sustainable ferrate oxidation: Reaction chemistry, mechanisms and applications to eliminate micro pollutant (pharmaceuticals) in wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 290, 117957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcillo, R.; Manzanera, M. The Effects of Plant-Associated Bacterial Exopolysaccharides on Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Metabolites 2021, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, I.; Ahmad, M.; Hussain, A.; Jamil, M. Potential of zinc solubilizing Bacillus strains to improve rice growth under axenic conditions. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 57, 1057–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz, M.Z.; Barrya, K.M.; Bakera, A.L.; Nicholsb, D.S.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Britza, M.L. Production of lactic and acetic acids by Bacillus sp. ZM20 and Bacillus cereus following exposure to zinc oxide: A possible mechanism for Zn solubilization. Rhizosphere 2019, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmusk, S.; Behers, L.; Muthoni, J.; Muraya, A.; Aronsson, A.C. 2017. Perspectives and challenges of microbial application for crop improvement Front. Plant. Sci. 2017, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Singh, B.K. Plamt-microbiome interactions: from community to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbial. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Q.; Lu, X.B.; Li, Z.H.; Tian, C.Y.; Song, J. The role of root-associated microbes in growth stimulation of plants under saline conditions. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 3471–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.; Li, J.; Chen, J.I.; Wang, G.; Mayes, M.A.; Dzantor, K.E.; Hui, D.; Luo, Y. Soil extracellular enzyme activities, soil carbon and nitrogen storage under nitrogen fertilization: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 101, pp.32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Zahir, Z.A.; Ditta, A.; Tahir, M.U.; Ahmad, M.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Hayat, K.; Hussain, S. Production and implication of bio-activated organic fertilizer enriched with zinc-solubilizing bacteria to boost up maize (Zea mays L.) production and biofortification under two cropping seasons. Agronomy 2020, 10, 39 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashe, N.S.; Mupambwa, H.A.; Green, E.; Mnkeni, P.N.S. Inoculation of fy ash amended vermicompost with phosphate solubilizing bacteria (Pseudomonas fuorescens) and its infuence on vermi-degradation, nutrient release and biological activity. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 14–22 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Bushra, Hussain, A. ; Dar, A.; Ahmad, M.; Wang, X.; Brtnicky, M.; Mustafa, A. Combined Use of Novel Endophytic and Rhizobacterial Strains Upregulates Antioxidant Enzyme Systems and Mineral Accumulation in Wheat. Agronomy 2022, 12, 551 https:// doiorg/103390/agronomy12030551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers. R. F.; Sizer, I. W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem. 1952, 195, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, G.; Roots, I. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent formation and breakdown of hydrogen peroxide during mixed function oxidation reactions in liver microsomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophy. 1975, 171, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, M.B.; Weaver, T. J.; Williams, B.C.; Crawford, R. L. Urease activity of ureolytic bacteria isolation from six soils in which calcite was precipitated by indigenous bacteria, Geomicrobiol. J. 2012, 29, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccino, J.G.; Sherman, N. Microbiology. Laboratory manual (8th edition,) Pearson. ISBN. 2002; Volume 13, 978-0805325782.

- Schwyn, B.; Neilands, J.B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 160, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, S.M. Iron acquisition in microbial pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 1993, 1, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Hasnain, S.; Berge, O.; Mahmood, T. Inoculating wheat seedlings with exopolysaccharide-producing bacteria restricts sodium uptake and stimulates plant growth under salt stress. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2004, 40, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsat, N.; Weerapreeyakul, N.; Siriamornpun, S. Change in the phenolic acids and antioxidant activity in Thai rice husk at fie growth stages during grain development. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4566–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, G. Studies on Lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. Bacteriol. 1952, 62, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollum II, A.G. Cultural methods for soil microorganisms. In: Methods of Soil Analysis: Chemical and Microbial Properties. A.L. Page, R.H. Miller and D.R. Keeney (Eds.), ASA and SSSA Publ. Madison, WI, USA. 1982; pp. 718-802.

- Cao, J.; Ji, D.; Wang, C. Interaction between earthworms and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the degradation of oxytetracycline in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liang, J.H.; He, Y.Y.; Hu, Q.J.; Yu, S. Effect of land use on soil enzyme activities at karst area in Nanchuan, Chongqing Southwest China. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Shoot length (cm) | Root length (cm) | Dry weight (g seedling-1) | Root surface area (cm2) | Root diameter (mm) | Root volume (cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 6.5 ± 0.08f | 4.3 ± 0.12f | 0.51 ± 0.01f | 9.8 ± 0.06d | 0.53 ± 0.03e | 0.37 ± 0.09c |

| AN30 | 7.1 ± 0.18e | 4.9 ± 0.11e | 0.59 ± 0.02de | 10.1 ± 0.15d | 0.57 ± 0.03de | 0.39 ± 0.05ac |

| AN31 | 7.9 ± 0.16de | 5.2 ± 0.16de | 0.61 ± 0.01de | 10.9 ± 0.06cd | 0.60 ± 0.06de | 0.40 ± 0.06bc |

| AN35 | 8.0 ± 0.32de | 5.5 ± 0.10de | 0.58 ± 0.01e | 11.3 ± 0.25cd | 0.63 ± 0.03cde | 0.43 ± 0.03ac |

| AN24 | 8.3 ± 0.23cd | 5.7 ± 0.05cd | 0.64 ± 0.01cd | 11.8 ± 0.09bc | 0.63 ± 0.03cde | 0.44 ± 0.04ac |

| AN24+AN31 | 8.8 ± 0.09b | 6.1 ± 0.10b | 0.67 ± 0.03bc | 12.5 ± 0.83b | 0.77 ± 0.03abc | 0.48 ± 0.02ac |

| AN24+AN35 | 8.8 ± 0.16b | 6.1 ± 0.16b | 0.71 ± 0.01b | 12.4 ± 0.27b | 0.67 ± 0.03cde | 0.47 ± 0.03ac |

| AN24+AN30 | 8.7 ± 0.05bc | 5.8 ± 0.09bc | 0.68 ± 0.00bc | 12.3 ± 0.24b | 0.80 ± 0.06ab | 0.47 ± 0.03ac |

| AN31+AN35 | 8.5 ± 0.09bc | 5.8 ± 0.09bc | 0.68 ± 0.01bc | 12.0 ± 0.94bc | 0.63 ± 0.03de | 0.47 ± 0.03ac |

| AN31+AN30 | 8.8 ± 0.08bc | 5.9 ± 0.08bc | 0.66 ± 0.03bc | 11.9 ± 0.73bc | 0.70 ± 0.06bcd | 0.51 ± 0.01ab |

| AN35+AN30 | 8.4 ± 0.16bc | 5.8 ± 0.09bc | 0.67 ± 0.02bc | 12.0 ± 0.58bc | 0.70 ± 0.06bcd | 0.47 ± 0.03ac |

| AN24+AN35+AN31+AN30 | 9.4 ± 0.26a | 6.6 ± 0.10a | 0.80 ± 0.02a | 13.0 ± 0.25a | 0.87 ± 0.12a | 0.54 ± 0.07a |

| LSD (p≤0.05) | 0.5161 | 0.3056 | 0.0562 | 1.3950 | 0.1589 | 0.1317 |

| Analysis | Unit | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Textural class | Sandy Loam | |

| ECe | dS m-1 | 1.59 ± 0.0233 |

| pH | 7.91 ± 0.0581 | |

| Saturation percentage | % | 31.73 ± 0.2333 |

| Organic matter | % | 0.58 ± 0.0088 |

| Phosphorus | mg kg-1 | 3.02 ± 0.0722 |

| Potassium | mg kg-1 | 75.50 ± 1.0408 |

| Nitrogen | % | 0.03 ± 0.0006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).