1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which started at the end of 2019, had a swift impact on the world. With the pandemic announced globally in March 2020, the COVID-19 epidemic, which altered the course of our lives, also had negative effects on education. As in every field, it caused disruptions of health systems and education at all levels. The leading causes of disruption were travel restrictions due to lockdowns (81.7%) and legal closure of services (65.4%) [

1]. Online education was among the solution options for students of all levels. The World Health Organization Authorities have published the need for information and communication technologies such as telehealth or mobile phone applications that can provide valid data and better evidence on the use of routine and innovative forms to reduce the effects of the pandemic on service interruptions [

2].

Before the pandemic, our experience with telemedicine in outpatient clinics was insufficient for the evaluation of neurological patients. The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Telemedicine Working Group planned to first model a tele-neurology curriculum for neurology residents in 2017 [

3]. In a pilot study conducted for neurology residents in the pre-pandemic period, it was shown that neurology residents; knowledge of basic telemedicine topics increased significantly, with limited theoretical and practical telemedicine training [

4]. While the efforts of neurologists related to telemedicine progressed slowly before the pandemic, mandatory changes emerged in patient profiles, working conditions, and training curricula with the COVID-19 pandemic. Education and specialization trainings in medical faculties continued with the online system. In fact, accessibility has increased with the online holding of various meetings in trainings on specific topics after specialization. It was relatively easy for many different disciplines to come together.

Migraine is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, especially in women younger than 50 years old. One-year prevalence of migraine in women is 18%, and one-year prevalence in men is 6% [

5]. In our country, the population-based 1-year prevalence study was diagnosed with two types of primary headache in the general population, 43.4%, 14.6% (8.5% in men and 24.6% in women) were diagnosed with definite migraine and pure tension- type headache at 5.1% (5.7% in men and 4.5% in women) [

6]. Epidemiological data in our country are similar to those of world data. Careful history taking and physical examination are the key for the diagnosis. Testing is usually not required. Treatment is based on non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Pharmacological interventions are to treat the headache and to prevent it.

In order to support education in our country, a program under the leadership of Global Migraine and Pain Society was prepared for the evaluation of painful patients in the pandemic. Online meetings were held every week between January 2021 and December 2022. Online meetings were launched with two invited speakers with two moderators in neurology and algology (pain physicians). These meetings had a case discussion and question-and-answer section which was held interactively. Online meetings were open and free for all physicians and medical students. With this survey, we had two main purposes:

1-To get information on approaches of neurology and algology physicians during evaluation of the patient with headache,

2-To evaluate the effect of these online meetings held on every week on the education and practical approaches of these physicians.

2. Materials and Methods

A questionnaire comprising three chapters and 27 questions was developed for the purpose of this study. Neurology and Algology physicians were contacted through social media and email addresses, and volunteers were invited to participate by answering the questionnaire. The questionnaire was sent to the relevant physicians, and reminders were sent as necessary. This survey was approved by the local ethical committee (ethical number: 17.05.2022-888854).

The questionnaire consisted of three main sections. The first section comprised questions related to demographic information. The second section consisted of multiple-choice questions about a patient with a headache, covering diagnosis, examination methods, and treatment options. The third section consisted of questions about whether the volunteers attended online meetings on a weekly basis (Supplementary material-1; English translation of study survey)

The data obtained in the study were analyzed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for Windows 22.0 program. Descriptive statistical methods, including number, percentage, average, and standard deviation values, were used to evaluate the data. The differences between the proportions of categorical variables in independent groups were analyzed using the Ki-square and Fisher Exact tests.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible Survey

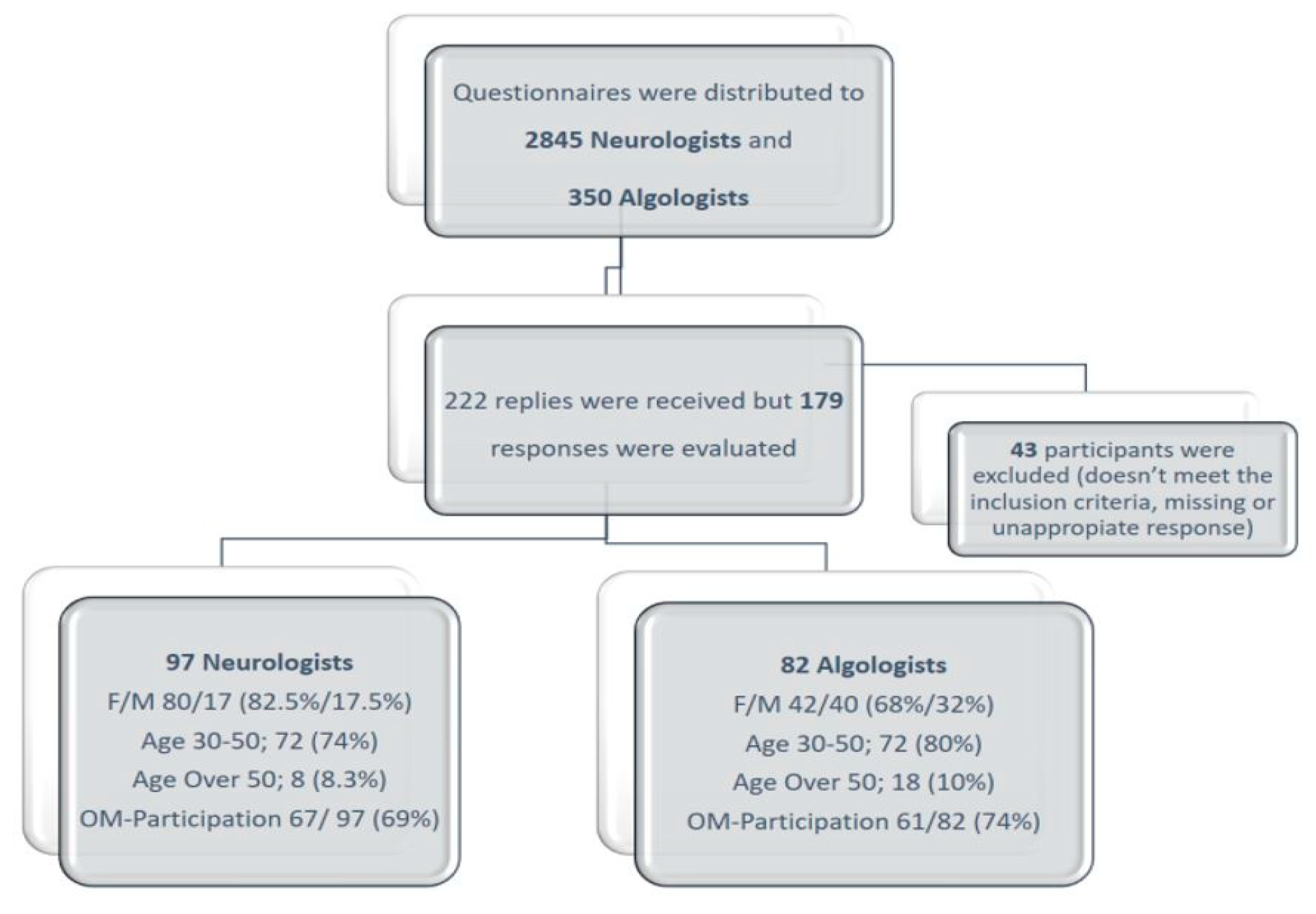

Eighty-two Algologists (42 females and 40 males) and 97 Neurologists (80 females and 17 males) completed the survey (

Figure 1). Most of the participants in the Algology Group (AG) were in the age range of 31-40 years (58.5%). However, the Neurology Group consisted of more senior participants (41.5% aged >40 years). While 92.7% of the AG participants were working in university hospitals, 61.9% of the NG participants worked in university hospitals, and 38.1% worked in state hospitals. Eighty percent of those who attended our meetings lived in big cities, and academicians represented 76% of the attendees.

3.1. Case story question analysis

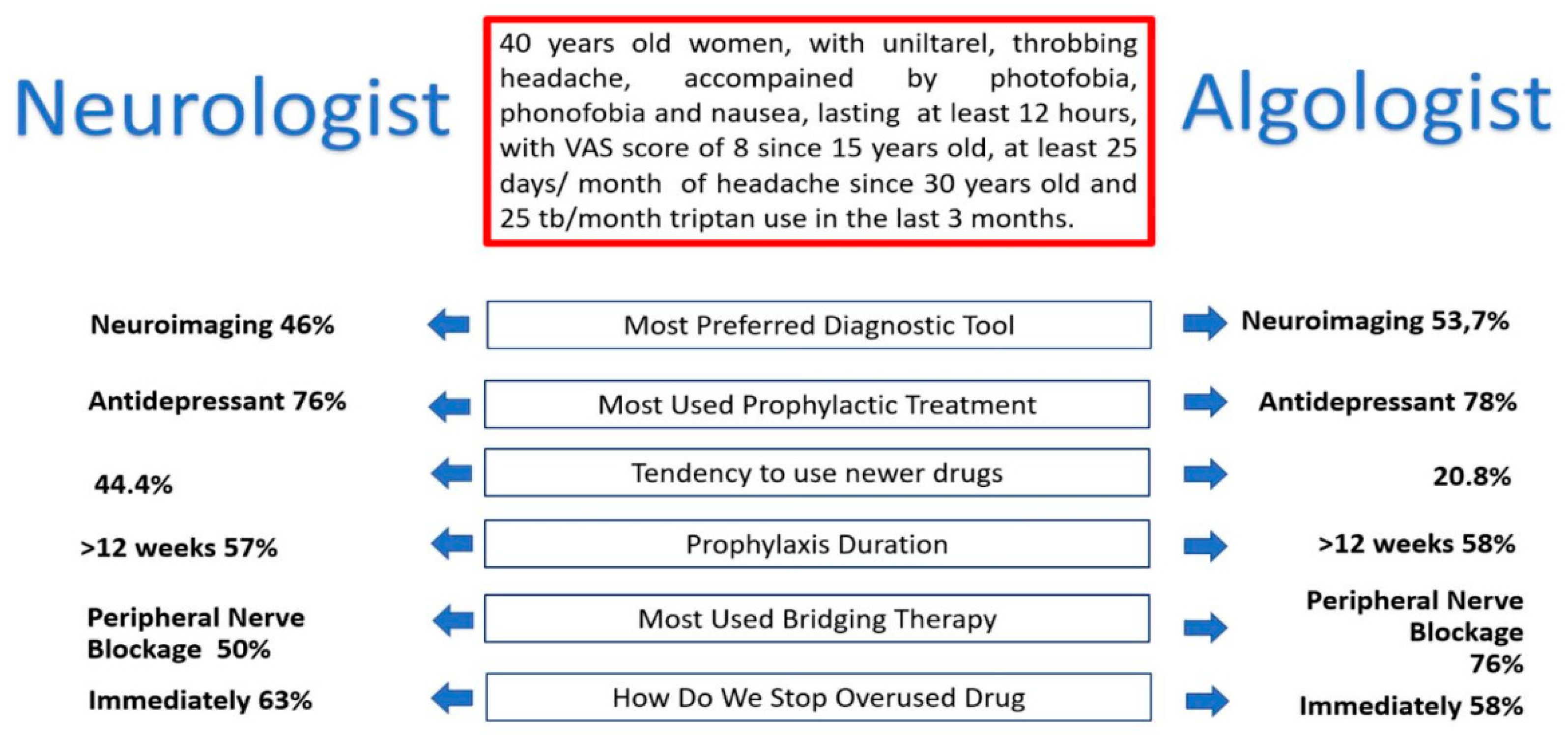

According to the ICHD-3 classification, the presented case had two diagnoses: 1) Migraine, and 2) Medication Overuse Headache. The most common response to the case was migraine (65%), followed by medication overuse headache (34%). This trend was reversed for the second pre-diagnosis. It was observed that both the Algology Group (AG) and the Neurology Group (NG) had a consensus on the preliminary diagnosis. Moreover, the groups gave similar responses to questions about the headache patient (

Figure 2).

The difference in response between diagnostic and differential diagnostic possibilities was not significant.

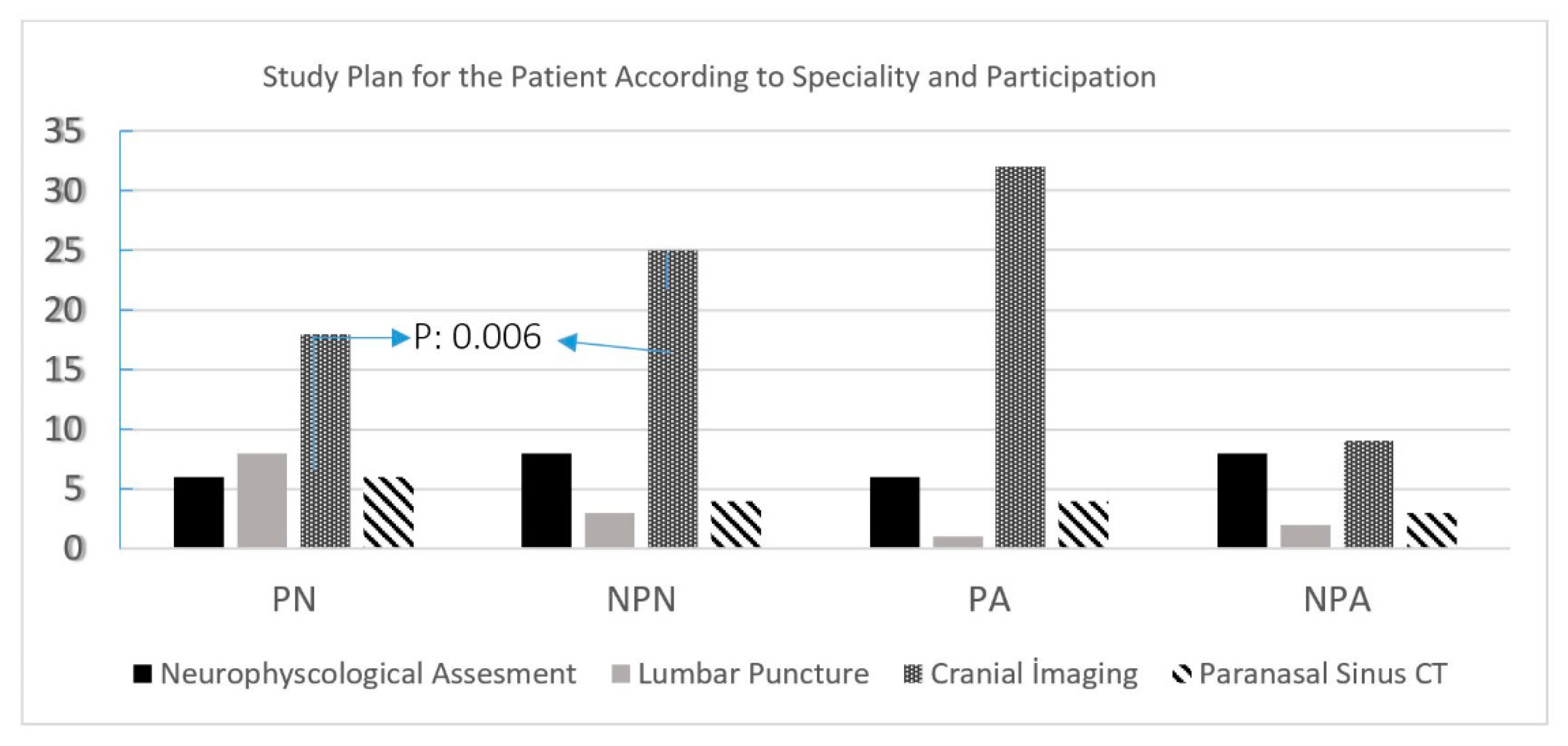

When the examination methods were compared in the two groups, the NG thought that the diagnosis was made by the history, while the AG believed further investigations should be performed on the patient (

Figure 3).

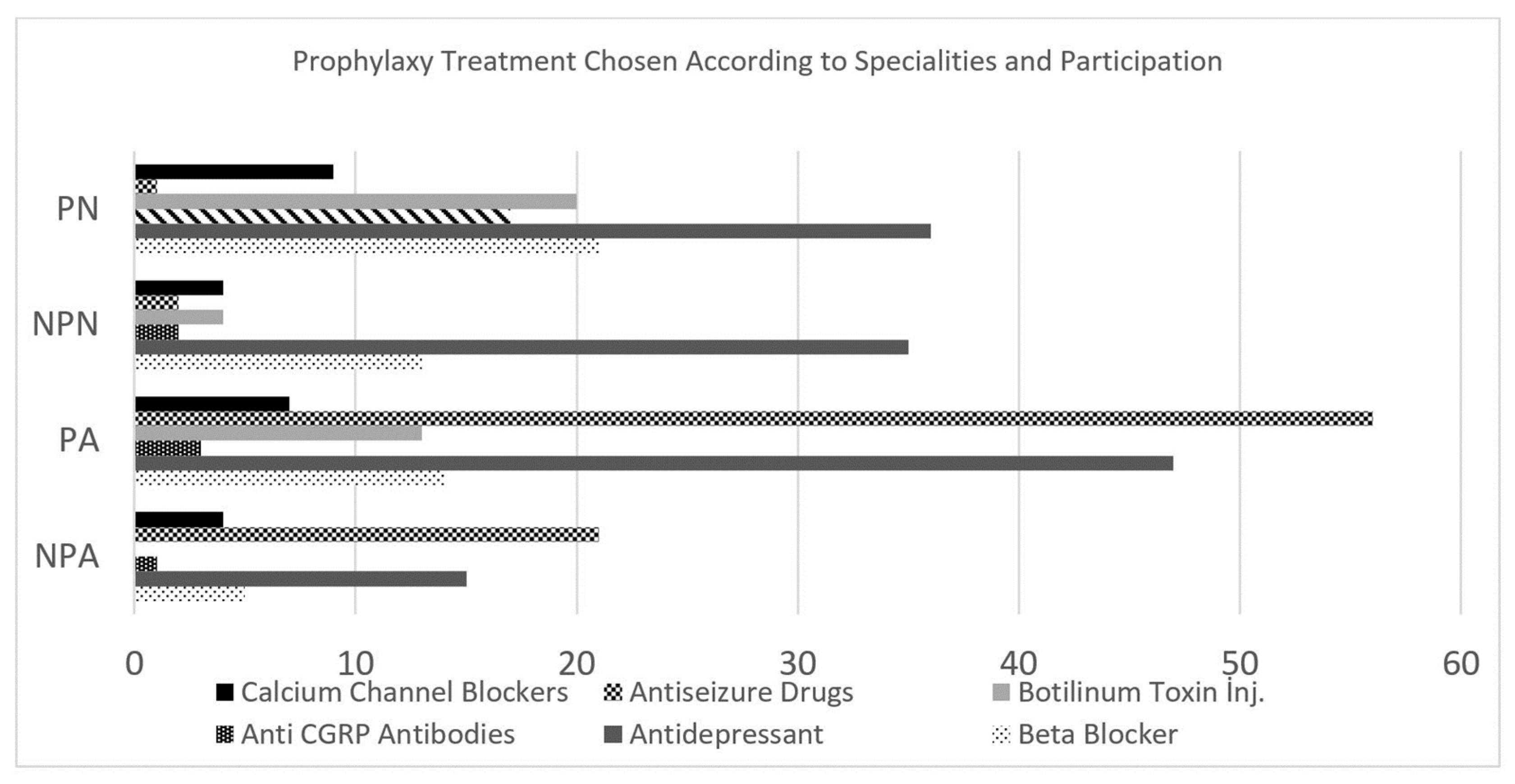

AG and NG agreed on the application of prophylaxis to the patient in questions in the treatment category. Classical prophylactic agents with scientifically proven efficacy (beta- blockers, anti-depressants, calcium channel blockers, anti-epileptics) were accepted in both groups. In addition, botulinum toxin administration, which is relatively new compared to conventional prophylactic agents, was established in both groups (

Figure 4).

However, the newest preventive treatment method, CGRP-antagonists, was used more frequently in the NG than in the AG. Both groups agreed about the abrupt discontinuation of drugs and initiation of bridge therapy in the treatment of the patient with medication overuse headache. While agents such as steroids, anti-epileptics, and magnesium were used at a similar rate in both groups, AG preferred peripheral nerve blockade more than NG.

3.3. Telehealth education program feedbacks

The participants reported that online meetings were reflected in their daily practices at the rate of 48%. More than 1/3 of the participants (35%) stated that they benefited partially.

When the effect of online meetings for AG and NG is evaluated; in both groups, it was seen that those who attended the training and those who did not mark similar choices in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis options. However, changes in the examination methods and treatment options of those who attended the online meetings in both AG and NG were remarkable. It was observed that those who did not attend online meetings marked unnecessary examination methods.

In the questions evaluating the treatment options, it was seen that the participants of the online meetings evaluated more up-to-date treatment options such as CGRP antagonists and Botulinum toxin. It was observed that those who did not attend online meetings in both AG and NG preferred relatively more conventional methods (such as antidepressants and Mg) in treatment.

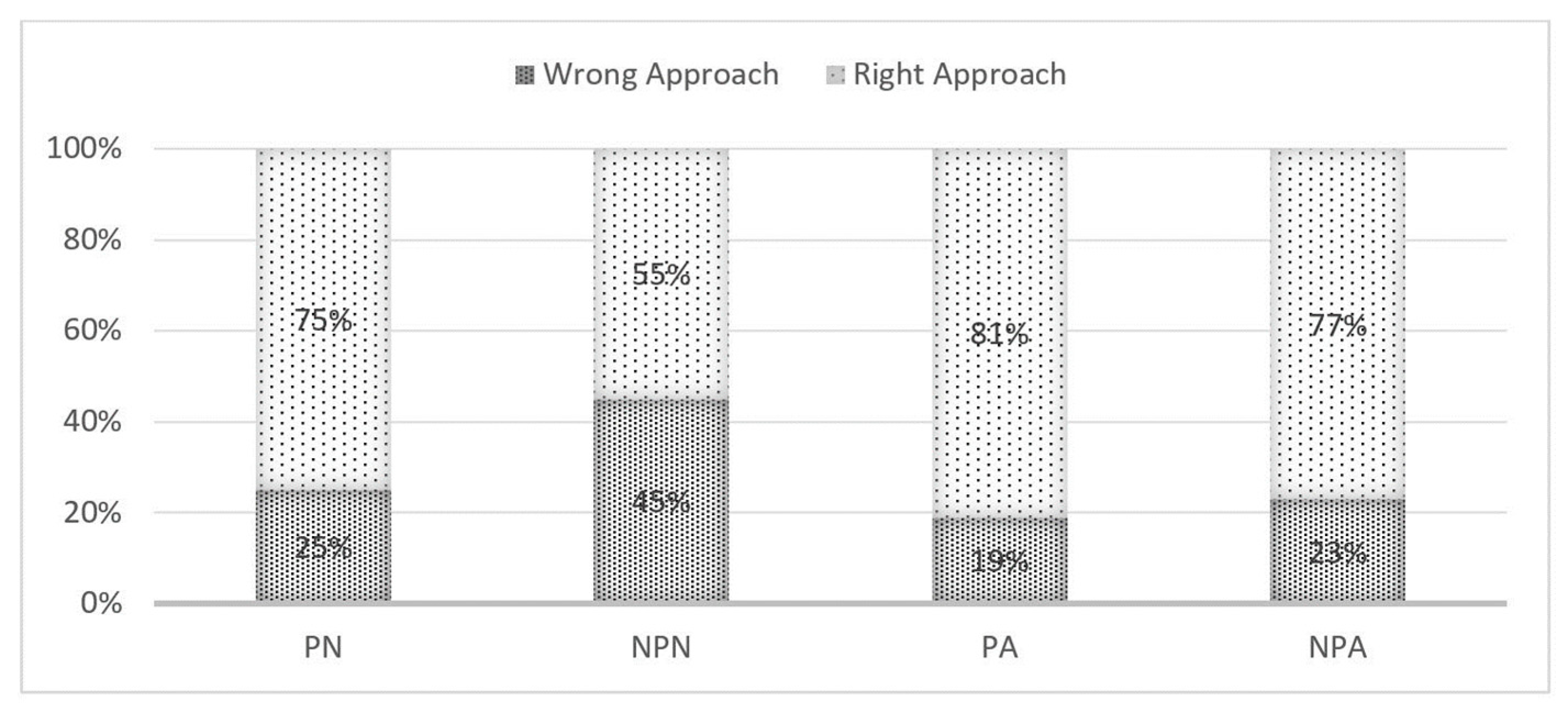

When the answers given to all questions were evaluated, the rate of correct approach to the questions differed between those who attended the online meetings and those who did not. Those who gave the highest percentage of correct answers were the group of algologists who attended online meetings (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The study aimed to investigate how online meetings affect the practices of physicians under pandemic conditions, and the data obtained showed that Algology and Neurology physicians evaluated patients with headaches similarly. However, members of both groups who reported participating in the online meetings differed from those who did not attend, in their approach to the patient, examination methods, and treatment options. Participants in online meetings used a more accurate review methodology and preferred current treatment options as effective. We found no significant differences in the approaches of AG and NG to patients with headache. The results of the survey revealed that 82 Algologists and 97 Neurologists participated in the study, with the majority of the AG participants in the age range of 31-40 years, while the NG consisted of more senior participants aged over 40 years. The AG had more participants working in university hospitals, while the NG had a mix of university and state hospital workers. The study also found that online meetings had a positive impact on the participants; daily practice, with 48% reporting a reflection of online meetings in their daily practices.

It is worth noting that 80% of meeting attendees live in big cities, suggesting their need for scientific meetings due to encountering a wide variety of patients. Surprisingly, 76% of academicians still attended these meetings, indicating a continuous effort to improve despite their advanced level. Most participants (81%) were aged 31-50, with only 10% over the age of fifty. The most dynamic group in pain medicine was found to be between the ages of 31-40, with female physicians comprising 68% of the participants and providing the dynamism in the group. In neurology, this percentage reaches 80%, indicating a need for psycho-social investigation to determine the origins of this feature.

Although demographic characteristics differed, there was no significant variation in patients; diagnoses and differential diagnoses between two groups. However, the AG exhibited a broader range of examination techniques in their examination planning. Treatment and follow-up options did not differ significantly between the two groups. Both groups correctly answered diagnosis and differential diagnosis questions regardless of whether they participated in online meetings or not. However, those who attended online meetings showed significant changes in their examination methods and treatment options, whereas those who did not participate tended to use unnecessary examination methods. Participants in online meetings preferred more up-to-date treatment options, such as CGRP antagonists and Botulinum toxin, in both groups.

The pandemic has necessitated changes in education worldwide, including the incorporation of virtual lessons into traditional education models. These virtual lessons offer several advantages, including the opportunity for students and educators to attend elective courses virtually from different cities worldwide, facilitating the sharing of knowledge, skills, and confidence at all levels. Furthermore, faculty members have been able to transfer their clinical expertise to the virtual platform, gaining experience with virtual teaching models [

7]. Singh et al. conducted a survey on the use of e-learning methods in nursing and medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. The study highlights the challenges faced by educators in delivering effective online education, such as lack of resources, technical difficulties, and student engagement. The findings can inform the development of strategies to address these challenges and improve online learning experiences [

8]. Huang et al. evaluated the impact of an online adult headache guideline on headache referrals to the neurology clinic. The study found that the guideline led to a significant reduction in referrals, suggesting that online resources can be an effective tool for improving healthcare practices [

9].

In the another study by Nguyen et al. investigated the current behaviors and impact of clinician education on migraine screening in primary eye care practice. The results of the study show that education on migraine screening led to improved clinician knowledge and increased screening rates, indicating that targeted education can improve healthcare practices [

10]. Our study confirms that physicians who participated in online meetings for two years to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on education and keep up with current literature were able to utilize the latest information regarding treatment options, especially when evaluating patients with headaches.

Telemedicine-online meetings for headaches may become an integral part of the hybrid system for patients and physicians [

11]. Russo et al. analyzed the readability of online headache and migraine information. The study found that most online resources were written at a level that exceeded the recommended reading level for the general population. The authors suggest that efforts should be made to improve the accessibility of online health information for patients with lower literacy levels [

12]. Katsuki et al. conducted a school-based online survey on the prevalence of chronic headache, migraine, and medication-overuse headache among children and adolescents in Japan. The study provides valuable information on the epidemiology of headache disorders in this population, which can inform the development of targeted interventions and treatments [

13].

In addition, online education programs and their timing are candidates to be included in our daily work and will probably be integrated into our education system [

14]. On the other hand, Michaeli et al. conducted a survey across nine countries to assess the impact of the COVID- 19 pandemic on medical education and mental health. The study found that medical students and residents experienced significant stress and anxiety due to the pandemic, which highlights the importance of addressing mental health issues among healthcare professionals [

15].

Overall, these studies highlight the importance of education and resources in improving healthcare practices and patient outcomes, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online resources and education can be effective tools for improving healthcare practices, but they must be designed and implemented effectively to ensure their effectiveness.

The study conducted by the researchers provides valuable insights into the differences in approaches to patients with headache by Algologists and Neurologists. It also highlights the importance of online meetings in updating the knowledge of healthcare professionals and improving their daily practice. The results of the study are consistent with previous research on the benefits of online education in healthcare. For instance, a systematic review by Li et al. found that online education improved healthcare professionals; knowledge, skill, and attitudes [

16]. Similarly, a study by Samuel et al. found that online education improved the clinical performance of healthcare professionals [

17]. On the other hand, the meta-analysis conducted by Kyaw et al. revealed that VR-based interventions were associated with significant improvements in clinical performance and skills development. The use of VR technology in health professions education was found to enhance learners; practical skills, clinical reasoning abilities, and procedural competency. Authors are also further support to the growing body of evidence on the benefits of online education, specifically in the context of virtual reality. It highlights the potential of VR as a valuable tool for enhancing healthcare education and training, providing immersive and interactive learning experiences that can bridge the gap between theory and practice [

18]. Overall, the results of the study suggest that online education is an effective way to update the knowledge of healthcare professionals and improve patient outcomes.

Case-based online education is a widely used approach in medical education that has been shown to improve clinical reasoning and decision-making skills among medical students and healthcare professionals [

19]. According to this study, case-based learning has been found to be effective in improving critical thinking skills and retaining information in medical students [

20]. Another study found that case-based learning in medical education leads to better clinical performance and more efficient problem-solving skills [

21]. In the context of telemedicine, case-based learning can be particularly useful in preparing healthcare professionals for providing remote patient care. A study found that case-based learning was an effective approach for teaching healthcare professionals about telemedicine technologies and their practical applications in patient care [

22]. It is worth noting that our case-based weekly online education model does not have any relevant industrial sponsorship, which indicates its impartiality and independence in delivering educational content to students and healthcare professionals. The absence of any sponsorship also highlights the importance of providing unbiased education to ensure that students and healthcare professionals receive comprehensive and accurate information in their learning and professional development. Our results revealed clear effect on the education on both disciplines and positive feedback. Overall, case-based online education provides an interactive and engaging learning experience that can help students and healthcare professionals develop their clinical reasoning and decision-making skills, which are critical in both medical and telemedicine settings.

The study has important implications for medical education and telehealth. The findings suggest that case-based online education can be an effective approach for improving the clinical reasoning and decision-making skills of healthcare professionals. The study also highlights the importance of telehealth education programs in preparing healthcare professionals for providing remote patient care. The results of this study suggest that telehealth education programs can be an effective way to improve healthcare professionals; knowledge and understanding of telemedicine technologies and their practical applications in patient care. Additionally, the study provides valuable insights into the differences in diagnosis and treatment approaches between Algology and Neurology physicians, and how case-based online education can be used to bridge these differences and promote best practices. Overall, the study’s findings can be used to inform the development of more effective medical education and telehealth programs that can improve patient care and outcomes.

Our results indicate that the online education program had a positive impact on the approach and decision-making process of physicians towards headache patients. The study also highlights the importance of evidence-based online education programs in keeping physicians up-to-date with the latest developments in their field. It is important to note that this study had some limitations, such as the limited sample size of physicians and the focus on a specific issue like headache. Therefore, further research is needed to evaluate the effect of online education programs in different fields of expertise and on a larger scale.

However, it is noteworthy that a specific issue such as headache was addressed, and two scientific fields, Neurology and Algology, were evaluated. Another limitation is that physicians may have had limited expression due to the survey study’s nature. Nonetheless, the multiple-choice survey questions and the option to select more than one answer were implemented to mitigate this constraint, as with all survey studies.

Regardless of the pandemic, online education has become an integral part of the modern education system. This cross-sectional study reveals that physicians who participated in online education followed a different and up-to-date approach in their management of patients with headaches, which is a specific issue. It is crucial that telemedicine applications are based on sound and evidence-based scientific principles and used safely. Furthermore, the results of our study indicate differences between neurologists and algologists who participated in online meetings versus those who did not. To our knowledge study is the first to assess the perspectives of two disciplines in the field of headache using a questionnaire, and it also investigated the impact of online education on groups. The results are promising, particularly for the two-year programs. Further studies evaluating the impact of online meetings in various subjects and fields of expertise will provide more clarity on the effectiveness and potential drawbacks of this relatively new education model. In conclusion, our study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a telehealth education program for Algologists and Neurologists in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with headaches. The results showed that both groups had a consensus on the preliminary diagnosis of the presented case, with migraine being the most common diagnosis. The participants also agreed on the application of prophylaxis, with classical prophylactic agents being accepted by both groups. However, the use of newer preventive treatment methods such as CGRP-antagonists was more frequent in the NG. The telehealth education program was found to have a positive impact on the participants; daily practices, with those who attended the online meetings showing remarkable changes in their examination methods and treatment options. Overall, this study highlights the importance of telehealth education programs in improving healthcare professionals; knowledge and practices, especially in the era of digital healthcare.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, E.K.O., M.S., A.Ö.; methodology, E.K.O., H.Ç., O.B.; formal analysis, E.K.O., H.Ç., İ.K., A.Ö.; investigation, E.K.O., H.Ç., İ.K., A.Ö., O.B., S.Ö., G.K.T., M.S; resources, E.K.O., H.Ç., A.Ö.; data curation, E.K.O., İ.K., A. Ö.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K.O., H.Ç., İ.K.; writing—review and editing, E.K.O., H.Ç., İ.K., A.Ö., O.B., S.Ö., G.K.T., M.S; supervision, A.Ö., S.Ö., G.K.T., M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Istanbul (protocol code 888854, date of approval 17.05.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the participants, as well as to the members of GMPS, Ethiccon, and the Doctor Club, for their invaluable support in conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Garcia-Azorin D, Seeher KM, Newton CR, et al. Disruptions of neurological services, its causes and mitigation strategies during COVID-19: a global review. J Neurol 2021; 268: 3947-3960. 20210522. [CrossRef]

- Organization, WH. The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological and substance use services: results of a rapid assessment.2020.

- Govindarajan R, Anderson ER, Hesselbrock RR, et al. Developing an outline for teleneurology curriculum: AAN Telemedicine Work Group recommendations. Neurology 2017; 89: 951-959. 20170802. [CrossRef]

- Afshari M, Witek NP and Galifianakis NB. Education Research: An experiential outpatient teleneurology curriculum for residents. Neurology 2019; 93: 170-175. [CrossRef]

- Ashina M, Buse DC, Ashina H, et al. Migraine: integrated approaches to clinical management and emerging treatments. Lancet 2021; 397: 1505-1518. 20210325. [CrossRef]

- Ertas M, Baykan B, Orhan EK, et al. One-year prevalence and the impact of migraine and tension-type headache in Turkey: a nationwide home-based study in adults. J Headache Pain 2012; 13: 147-157. 20120114. [CrossRef]

- Gummerson CE, Lo BD, Porosnicu Rodriguez KA, et al. Broadening learning communities during COVID-19: developing a curricular framework for telemedicine education in neurology. BMC Med Educ 2021; 21: 549. 20211029. [CrossRef]

- Singh HK, Joshi A, Malepati RN, et al. A survey of E-learning methods in nursing and medical education during COVID-19 pandemic in India. Nurse Educ Today 2021; 99: 104796. 20210206. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Bourke D and Ranta A. The impact of an online adult headache guideline on headache referrals to the neurology clinic. Intern Med J 2021; 51: 1251-1254. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen BN, Singh S, Downie LE, et al. Migraine Screening in Primary Eye Care Practice: Current Behaviors and the Impact of Clinician Education. Headache 2020; 60: 1817-1829. 20200807. [CrossRef]

- Spina E, Tedeschi G, Russo A, et al. Telemedicine application to headache: a critical review. Neurol Sci 2022; 43: 3795-3801. 20220124. [CrossRef]

- Russo A, Lavorgna L, Silvestro M, et al. Readability Analysis of Online Headache and Migraine Information. Headache 2020; 60: 1317-1324. 20200528. [CrossRef]

- Katsuki M, Matsumori Y, Kawahara J, et al. School-based online survey on chronic headache, migraine, and medication-overuse headache prevalence among children and adolescents in Japanese one city - Itoigawa Benizuwaigani study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2023; 226: 107610. 20230120. [CrossRef]

- Muller KI, Alstadhaug KB and Bekkelund SI. Acceptability, Feasibility, and Cost of Telemedicine for Nonacute Headaches: A Randomized Study Comparing Video and Traditional Consultations. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e140. 20160530. [CrossRef]

- Michaeli D, Keough G, Perez-Dominguez F, et al. Medical education and mental health during COVID-19: a survey across 9 countries. Int J Med Educ 2022; 13: 35-46. 20220226. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Gillies R, He M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to online medical and nursing education during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives from international students from low- and middle- income countries and their teaching staff. Hum Resour Health 2021; 19: 64. 20210512. [CrossRef]

- Samuel A, Cervero RM, Durning SJ, et al. Effect of Continuing Professional Development on Health Professionals' Performance and Patient Outcomes: A Scoping Review of Knowledge Syntheses. Acad Med 2021; 96: 913-923. [CrossRef]

- Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki P, et al. Virtual Reality for Health Professions Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e12959. 20190122. [CrossRef]

- Alkhasawneh IM, Mrayyan MT, Docherty C, et al. Problem-based learning (PBL): assessing Students; learning preferences using VARK. Nurse Educ Today 2008; 28: 572-579. 20071105. [CrossRef]

- Orban K, Ekelin M, Edgren G, et al. Monitoring progression of clinical reasoning skills during health sciences education using the case method - a qualitative observational study. BMC Med Educ 2017; 17: 158. 20170911. [CrossRef]

- Morris C, Scott RE and Mars M. WhatsApp in Clinical Practice-The Challenges of Record Keeping and Storage. A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18 20211220. [CrossRef]

- Mars M and Scott, RE. WhatsApp in Clinical Practice: A Literature Review. Stud Health Technol Inform 2016; 231: 82-90.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).