Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Risk factors and complications of COVID-19

| Risk factor | Number of studies | Total sample size | Association with covid severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 142 | 59’476 | Yes |

| Hypertension | 140 | 58’808 | Yes |

| Malignancy | 94 | 48’488 | Yes |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 71 | 16’124 | Yes |

| Chronic liver disease | 56 | 27’924 | Yes |

| COPD | 50 | 32’173 | Yes |

| Chronic kidney disease | 43 | 20’103 | Yes |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 37 | 25’016 | Yes |

| Coronary heart disease | 33 | 16’525 | Yes |

| Respiratory disease | 31 | 7’552 | Yes |

| Chronic lung disease | 31 | 3’702 | Yes |

| Chronic heart disease | 9 | 3’583 | Yes |

| Autoimmune disease | 7 | 2’372 | Yes |

| Renal insufficiency | 6 | 2’997 | Yes |

| Stroke | 5 | 1’616 | Yes |

| Cerebral infarction | 4 | 2’647 | Yes |

| Fatty liver | 4 | 992 | Yes |

| Arrhythmia | 4 | 781 | Yes |

| Cardiac insufficiency | 2 | 1’912 | Yes |

| Genital system diseases | 2 | 546 | Yes |

| Kidney failure | 2 | 294 | Yes |

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 1 | 3’044 | Yes |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 1 | 3’044 | Yes |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 660 | Yes |

| Aorta sclerosis | 1 | 140 | No |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 | 112 | No |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 | 1’073 | No |

| Heart failure | 1 | 172 | No |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 1 | 1’767 | No |

| Asthma | 3 | 5’359 | No |

| Chronic bronchitis | 2 | 2’525 | No |

| Tuberculosis | 7 | 4’125 | No |

| Nephritis | 1 | 3’044 | No |

| Gallbladder disease | 3 | 779 | No |

| Hepatitis B | 6 | 3’307 | No |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 6 | 4’764 | No |

| Peptic ulcer | 1 | 145 | No |

| Gout | 1 | 134 | No |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7 | 4’131 | No |

| Hyperuricemia | 1 | 172 | No |

| Thyroid disease | 5 | 1’125 | No |

| Cirrhosis | 3 | 5’134 | No |

| Prostatitis | 1 | 3’044 | No |

| Gynecological disease | 1 | 238 | No |

| HIV infection | 7 | 1’099 | No |

| Nervous system disease | 5 | 2’203 | No |

| Rheumatism | 2 | 273 | No |

| Urinary system disease | 2 | 1’075 | No |

| Urolithiasis | 1 | 140 | No |

| Blood system diseases | 3 | 965 | No |

| Bone disease | 1 | 238 | No |

2. COVID-19-induced sepsis, immunotherapies, and antiviral treatments

| Mechanism | Drug family | Drugs | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | Systemic glucocorticoids | Dexamethasone, Prednisone, Hydrocortisone, Methylprednisolone | Recommended for certain hospitalized patients |

| Anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies | Tocilizumab, Sarulimab | Recommended for certain hospitalized patients | |

| Anti-IL-6 antibody | Siltuximab | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials | |

| IL-1 receptor antagonists | Anakinra, Canakinumab | Anakinra received an FDA EUA for certain hospitalized patients.Canakinumab is not recommended | |

| JAK/STAT inhibitors | Baricitinib, Tofacitinib, Ruxolitinib | Baricitinib and Tofacitinib recommended for certain hospitalized patients.Ruxolitinib under investigation in clinical trials | |

| GM-CSF inhibitors | Lenzilumab, Mavrilimumab, Namilumab, Otilimab, Gimsilumab | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials | |

| TNF-alpha inhibitor | XPro1595, CERC-002, Infliximab, Adalimumab | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials | |

| Immune stimulants | Programmed death ligand pathway inhibitors | Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials |

| IL-7 | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials | ||

| IFN-γ | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials | ||

| NKG2D-ACE2 CAR-NK cells | Not recommended. Under investigation in clinical trials |

| EarlySepsis | EarlyCOVID-19 | LateSepsis | LateCOVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 increase | +++ | + | +++ | |

| Lymphopenia | + | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Nosocomial infections | +++ | +++ |

| Drug | Brand name | FDAEUA | EMA CMA | Rescinded-revised by FDA/EMA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antivirals | Hydroxychloroquine sulfateChloroquine phosphate | Several | Ma 2020 | Jun 2020 | |

| Remdesivir | Veklury | May 2020 | Jun 2020 | ||

| Nirmatrelvir/ Ritonavir | Paxlovid | Dec 2021 | Jan 2022 | ||

| Molnupiravir | Lagevrio | Dec 2021 | |||

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2-antibodies | Convalescent plasma | Aug 2020 | |||

| Bamlanivimab | Nov 2020 | Mar 2021 | Jan 2022/Nov 2021 | ||

| Casirivimab/Imdevimab | Regn-cov2 | Nov 2020 | Feb 2021 | Jan 2022 | |

| Etesevimab | Dec 2021 | Mar 2021 | Jan 2022/Nov 2021 | ||

| Tixagevimab/Cilgavimab | Evusheld | Dec 2021 | Mar 2022 | ||

| Sotrovimab | Xevudy | Jan 2022 | May 2021 | ||

| Regdanvimab | Regkirona | Nov 2021 |

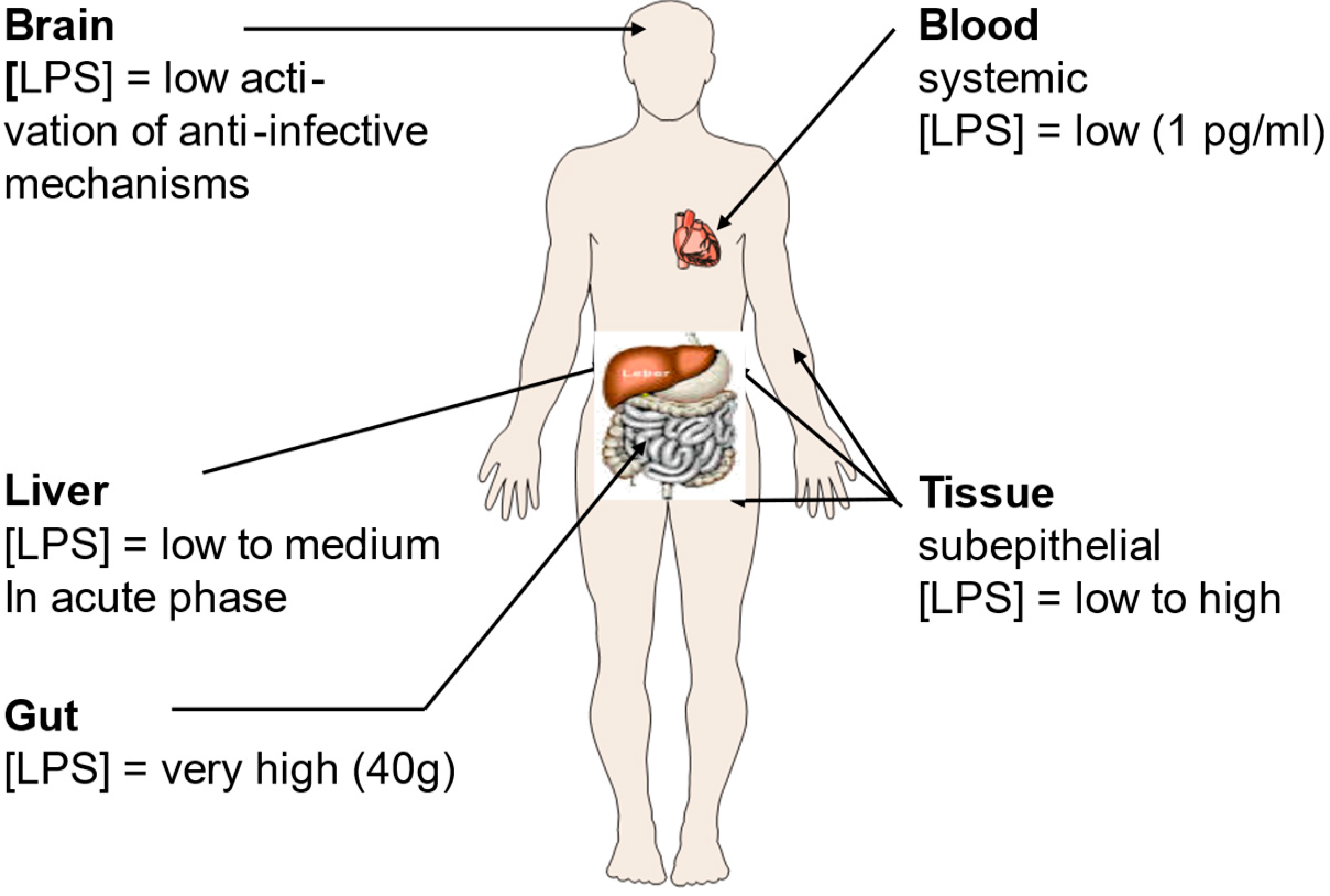

3. Bacterial coinfections and the relationship between LPS and SARS-CoV-2

4. Influence of SARS-CoV-2 on the coagulation system

5. Long COVID-19 syndrome

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crespi BJ: Evolutionary and genetic insights for clinical psychology. Clin Psychol Rev 2020, 78:101857. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Appl B, Kafferlein E, Loffler T, Jahn-Henninger H, Gutensohn W, Nores JR, McCullough K, Passlick B, Labeta MO et al: The antibody MY4 recognizes CD14 on porcine monocytes and macrophages. Scand J Immunol 1994, 40(5):509-514. [CrossRef]

- Gallo CG, Fiorino S, Posabella G, Antonacci D, Tropeano A, Pausini E, Pausini C, Guarniero T, Hong W, Giampieri E et al: COVID-19, what could sepsis, severe acute pancreatitis, gender differences, and aging teach us? Cytokine 2021, 148:155628. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Peng Y, Wu X, Pang B, Yang F, Zheng W, Liu C, Zhang J: Comorbidities and complications of COVID-19 associated with disease severity, progression, and mortality in China with centralized isolation and hospitalization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2022, 10:923485. [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom B, Frithiof R, Larsson IM, Strandberg G, Lipcsey M, Hultstrom M: A comparison of impact of comorbidities and demographics on 60-day mortality in ICU patients with COVID-19, sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Sci Rep 2022, 12(1):15703. [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS et al: Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature medicine 2021, 27(4):601-615. [CrossRef]

- Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, Kastritis E, Sergentanis TN, Politou M, Psaltopoulou T, Gerotziafas G, Dimopoulos MA: Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol 2020, 95(7):834-847. [CrossRef]

- Drake TM, Riad AM, Fairfield CJ, Egan C, Knight SR, Pius R, Hardwick HE, Norman L, Shaw CA, McLean KA et al: Characterisation of in-hospital complications associated with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK: a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet 2021, 398(10296):223-237. [CrossRef]

- Shappell C, Rhee C, Klompas M: Update on Sepsis Epidemiology in the Era of COVID-19. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2023, 44(1):173-184. [CrossRef]

- Cavaillon JM: During Sepsis and COVID-19, the Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Responses Are Concomitant. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kostakis I, Smith GB, Prytherch D, Meredith P, Price C, Chauhan A, Portsmouth Academic ConsortIum For Investigating C: The performance of the National Early Warning Score and National Early Warning Score 2 in hospitalised patients infected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Resuscitation 2021, 159:150-157. [CrossRef]

- Lalueza A, Lora-Tamayo J, Maestro-de la Calle G, Folgueira D, Arrieta E, de Miguel-Campo B, Diaz-Simon R, Lora D, de la Calle C, Mancheno-Losa M et al: A predictive score at admission for respiratory failure among hospitalized patients with confirmed 2019 Coronavirus Disease: a simple tool for a complex problem. Intern Emerg Med 2022, 17(2):515-524. [CrossRef]

- Herminghaus A, Osuchowski MF: How sepsis parallels and differs from COVID-19. EBioMedicine 2022, 86:104355.

- Stasi A, Franzin R, Fiorentino M, Squiccimarro E, Castellano G, Gesualdo L: Multifaced Roles of HDL in Sepsis and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Renal Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(11). [CrossRef]

- Coudereau R, Waeckel L, Cour M, Rimmele T, Pescarmona R, Fabri A, Jallades L, Yonis H, Gossez M, Lukaszewicz AC et al: Emergence of immunosuppressive LOX-1+ PMN-MDSC in septic shock and severe COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Leukoc Biol 2022, 111(2):489-496. [CrossRef]

- Stasi A, Castellano G, Ranieri E, Infante B, Stallone G, Gesualdo L, Netti GS: SARS-CoV-2 and Viral Sepsis: Immune Dysfunction and Implications in Kidney Failure. J Clin Med 2020, 9(12). [CrossRef]

- Dong X, Wang C, Liu X, Gao W, Bai X, Li Z: Lessons Learned Comparing Immune System Alterations of Bacterial Sepsis and SARS-CoV-2 Sepsis. Front Immunol 2020, 11:598404. [CrossRef]

- Gorski A, Borysowski J, Miedzybrodzki R: Sepsis, Phages, and COVID-19. Pathogens 2020, 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Limmer A, Engler A, Kattner S, Gregorius J, Pattberg KT, Schulz R, Schwab J, Roth J, Vogl T, Krawczyk A et al: Patients with SARS-CoV-2-Induced Viral Sepsis Simultaneously Show Immune Activation, Impaired Immune Function and a Procoagulatory Disease State. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Plocque A, Mitri C, Lefevre C, Tabary O, Touqui L, Philippart F: Should We Interfere with the Interleukin-6 Receptor During COVID-19: What Do We Know So Far? Drugs 2023, 83(1):1-36. [CrossRef]

- Remy KE, Mazer M, Striker DA, Ellebedy AH, Walton AH, Unsinger J, Blood TM, Mudd PA, Yi DJ, Mannion DA et al: Severe immunosuppression and not a cytokine storm characterizes COVID-19 infections. JCI Insight 2020, 5(17).

- Chousterman BG, Swirski FK, Weber GF: Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol 2017, 39(5):517-528. [CrossRef]

- Tang H, Qin S, Li Z, Gao W, Tang M, Dong X: Early immune system alterations in patients with septic shock. Front Immunol 2023, 14:1126874. [CrossRef]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ: Failure of treatments based on the cytokine storm theory of sepsis: time for a novel approach. Immunotherapy 2013, 5(3):207-209. [CrossRef]

- Fortier ME, Kent S, Ashdown H, Poole S, Boksa P, Luheshi GN: The viral mimic, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid, induces fever in rats via an interleukin-1-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2004, 287(4):R759-766. [CrossRef]

- Gu T, Zhao S, Jin G, Song M, Zhi Y, Zhao R, Ma F, Zheng Y, Wang K, Liu H et al: Cytokine Signature Induced by SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein in a Mouse Model. Front Immunol 2020, 11:621441. [CrossRef]

- Allaouchiche B: Immunotherapies for COVID-19: Restoring the immunity could be the priority. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2020, 39(3):385. [CrossRef]

- Gallo RL, Huttner KM: Antimicrobial peptides: an emerging concept in cutaneous biology. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 1998, 111(5):739-743. [CrossRef]

- Perlin DS, Neil GA, Anderson C, Zafir-Lavie I, Raines S, Ware CF, Wilkins HJ: Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of human anti-LIGHT monoclonal antibody in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Journal of clinical investigation 2022, 132(3). [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Hu K, Li Y, Lu C, Ling K, Cai C, Wang W, Ye D: Targeting TNF-alpha for COVID-19: Recent Advanced and Controversies. Front Public Health 2022, 10:833967. [CrossRef]

- Pau AK, Aberg J, Baker J, Belperio PS, Coopersmith C, Crew P, Grund B, Gulick RM, Harrison C, Kim A et al: Convalescent Plasma for the Treatment of COVID-19: Perspectives of the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Ann Intern Med 2021, 174(1):93-95. [CrossRef]

- Remy KE, Brakenridge SC, Francois B, Daix T, Deutschman CS, Monneret G, Jeannet R, Laterre PF, Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL: Immunotherapies for COVID-19: lessons learned from sepsis. Lancet Respir Med 2020, 8(10):946-949. [CrossRef]

- Islam H, Chamberlain TC, Mui AL, Little JP: Elevated Interleukin-10 Levels in COVID-19: Potentiation of Pro-Inflammatory Responses or Impaired Anti-Inflammatory Action? Front Immunol 2021, 12:677008. [CrossRef]

- Dalinghaus M, Willem J, Gratama C, Koers JH, Gerding AM, Zijlstra WG, Kuipers JR: Left ventricular oxygen and substrate uptake in chronically hypoxemic lambs. Pediatric research 1993, 34(4):471-477. [CrossRef]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X et al: Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395(10229):1054-1062. [CrossRef]

- Davitt E, Davitt C, Mazer MB, Areti SS, Hotchkiss RS, Remy KE: COVID-19 disease and immune dysregulation. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2022, 35(3):101401. [CrossRef]

- Riva G, Nasillo V, Tagliafico E, Trenti T, Comoli P, Luppi M: COVID-19: more than a cytokine storm. Crit Care 2020, 24(1):549.

- Gartenhaus RB, Wang P, Hoffmann P: Induction of the WAF1/CIP1 protein and apoptosis in human T-cell leukemia virus type I-transformed lymphocytes after treatment with adriamycin by using a p53-independent pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1996, 93(1):265-268. [CrossRef]

- Dueck R, Schroeder JP, Parker HR, Rathbun M, Smolen K: Carotid artery exteriorization for percutaneous catheterization in sheep and dogs. Am J Vet Res 1982, 43(5):898-901.

- Mayor S: Intensive immunosuppression reduces deaths in covid-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome, study finds. Bmj 2020, 370:m2935. [CrossRef]

- Zheng HY, Zhang M, Yang CX, Zhang N, Wang XC, Yang XP, Dong XQ, Zheng YT: Elevated exhaustion levels and reduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe progression in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17(5):541-543. [CrossRef]

- Daix T, Mathonnet A, Brakenridge S, Dequin PF, Mira JP, Berbille F, Morre M, Jeannet R, Blood T, Unsinger J et al: Intravenously administered interleukin-7 to reverse lymphopenia in patients with septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care 2023, 13(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Francois B, Jeannet R, Daix T, Walton AH, Shotwell MS, Unsinger J, Monneret G, Rimmele T, Blood T, Morre M et al: Interleukin-7 restores lymphocytes in septic shock: the IRIS-7 randomized clinical trial. JCI Insight 2018, 3(5).

- Lai CC, Wang CY, Hsueh PR: Co-infections among patients with COVID-19: The need for combination therapy with non-anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents? J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020, 53(4):505-512. [CrossRef]

- Elnagdy S, AlKhazindar M: The Potential of Antimicrobial Peptides as an Antiviral Therapy against COVID-19. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2020, 3(4):780-782. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Meng X, Zhang F, Xiang Y, Wang J: The in vitro antiviral activity of lactoferrin against common human coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by targeting the heparan sulfate co-receptor. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021, 10(1):317-330. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg K, Jrgens G, Mller M, Fukuoka S, Koch MHJ: Biophysical characterization of lipopolysaccharide and lipid A inactivation by lactoferrin. BiolChem 2001, 382:1215-1225. [CrossRef]

- Barcena-Varela S, Martinez-de-Tejada G, Martin L, Schuerholz T, Gil-Royo AG, Fukuoka S, Goldmann T, Droemann D, Correa W, Gutsmann T et al: Coupling killing to neutralization: combined therapy with ceftriaxone/Pep19-2.5 counteracts sepsis in rabbits. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49(6):e345. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg K, Andra J, Garidel P, Gutsmann T: Peptide-based treatment of sepsis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 90(3):799-808. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg K, Schromm AB, Weindl G, Heinbockel L, Correa W, Mauss K, Martinez de Tejada G, Garidel P: An update on endotoxin neutralization strategies in Gram-negative bacterial infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2021, 19(4):495-517. [CrossRef]

- utsmann T, Razquin-Olazaran I, Kowalski I, Kaconis Y, Howe J, Bartels R, Hornef M, Schurholz T, Rossle M, Sanchez-Gomez S et al: New antiseptic peptides to protect against endotoxin-mediated shock. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54(9):3817-3824. [CrossRef]

- Kaconis Y, Kowalski I, Howe J, Brauser A, Richter W, Razquin-Olazaran I, Inigo-Pestana M, Garidel P, Rossle M, Martinez de Tejada G et al: Biophysical mechanisms of endotoxin neutralization by cationic amphiphilic peptides. Biophys J 2011, 100(11):2652-2661.

- Sohn KM, Lee SG, Kim HJ, Cheon S, Jeong H, Lee J, Kim IS, Silwal P, Kim YJ, Paik S et al: COVID-19 Patients Upregulate Toll-like Receptor 4-mediated Inflammatory Signaling That Mimics Bacterial Sepsis. J Korean Med Sci 2020, 35(38):e343. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei R, Goodarzi P, Asadi M, Soltani A, Aljanabi HAA, Jeda AS, Dashtbin S, Jalalifar S, Mohammadzadeh R, Teimoori A et al: Bacterial co-infections with SARS-CoV-2. IUBMB Life 2020, 72(10):2097-2111. [CrossRef]

- Conti G, Amadori F, Bordanzi A, Majorana A, Bardellini E: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pediatric Dentistry: Insights from an Italian Cross-Sectional Survey. Dent J (Basel) 2023, 11(6). [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X et al: Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395(10223):497-506. [CrossRef]

- Rietschel ET, Brade H, Holst O, Brade L, Muller-Loennies S, Mamat U, Zahringer U, Beckmann F, Seydel U, Brandenburg K et al: Bacterial endotoxin: Chemical constitution, biological recognition, host response, and immunological detoxification. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1996, 216:39-81. [CrossRef]

- Martinez de Tejada G, Heinbockel L, Ferrer-Espada R, Heine H, Alexander C, Barcena-Varela S, Goldmann T, Correa W, Wiesmuller KH, Gisch N et al: Lipoproteins/peptides are sepsis-inducing toxins from bacteria that can be neutralized by synthetic anti-endotoxin peptides. Sci Rep 2015, 5:14292. [CrossRef]

- Wilson JG, Simpson LJ, Ferreira AM, Rustagi A, Roque J, Asuni A, Ranganath T, Grant PM, Subramanian A, Rosenberg-Hasson Y et al: Cytokine profile in plasma of severe COVID-19 does not differ from ARDS and sepsis. JCI Insight 2020, 5(17).

- Luderitz O, Galanos C, Rietschel ET: Endotoxins of Gram-negative bacteria. Pharmacol Ther 1981, 15(3):383-402.

- Mohammad S, Al Zoubi S, Collotta D, Krieg N, Wissuwa B, Ferreira Alves G, Purvis GSD, Norata GD, Baragetti A, Catapano AL et al: A Synthetic Peptide Designed to Neutralize Lipopolysaccharides Attenuates Metaflammation and Diet-Induced Metabolic Derangements in Mice. Front Immunol 2021, 12:701275. [CrossRef]

- Munford RS: Endotoxin(s) and the liver. Gastroenterology 1978, 75(3):532-535.

- Petruk G, Puthia M, Petrlova J, Samsudin F, Stromdahl AC, Cerps S, Uller L, Kjellstrom S, Bond PJ, Schmidtchen AA: SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and boosts proinflammatory activity. J Mol Cell Biol 2020, 12(12):916-932. [CrossRef]

- Andra J, Gutsmann T, Garidel P, Brandenburg K: Mechanisms of endotoxin neutralization by synthetic cationic compounds. J Endotoxin Res 2006, 12(5):261-277.

- Teixeira PC, Dorneles GP, Santana Filho PC, da Silva IM, Schipper LL, Postiga IAL, Neves CAM, Rodrigues Junior LC, Peres A, Souto JT et al: Increased LPS levels coexist with systemic inflammation and result in monocyte activation in severe COVID-19 patients. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 100:108125. [CrossRef]

- Fan C, Wu Y, Rui X, Yang Y, Ling C, Liu S, Liu S, Wang Y: Animal models for COVID-19: advances, gaps and perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7(1):220. [CrossRef]

- Hong W, Yang J, Bi Z, He C, Lei H, Yu W, Yang Y, Fan C, Lu S, Peng X et al: A mouse model for SARS-CoV-2-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Puthia M, Tanner L, Petruk G, Schmidtchen A: Experimental Model of Pulmonary Inflammation Induced by SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Endotoxin. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2022, 5(3):141-148. [CrossRef]

- Tobias PS, Soldau K, Gegner JA, Mintz D, Ulevitch RJ: Lipopolysaccharide binding protein-mediated complexation of lipopolysaccharide with soluble CD14. J Biol Chem 1995, 270(18):10482-10488. [CrossRef]

- Schumann RR, Latz E: Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. ChemImmunol 2000, 74:42-60.

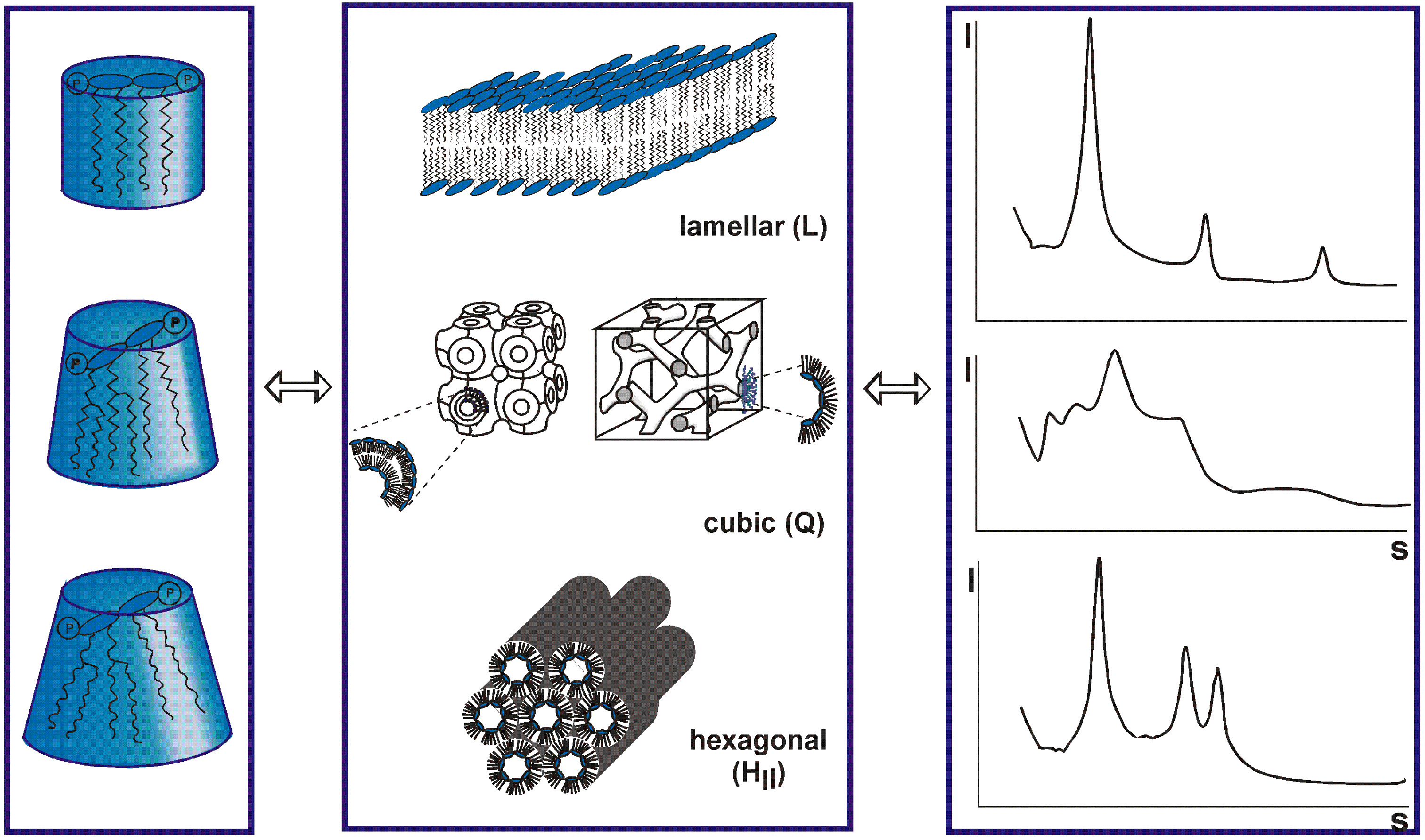

- Richter W, Vogel V, Howe J, Steiniger F, Brauser A, Koch MH, Roessle M, Gutsmann T, Garidel P, Mantele W et al: Morphology, size distribution, and aggregate structure of lipopolysaccharide and lipid A dispersions from enterobacterial origin. Innate Immun 2011, 17(5):427-438. [CrossRef]

- Mueller M, Lindner B, Kusumoto S, Fukase K, Schromm AB, Seydel U: Aggregates are the biologically active units of endotoxin. J Biol Chem 2004, 279(25):26307-26313. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg K, Schromm AB, Gutsmann T: Endotoxins: relationship between structure, function, and activity. Subcell Biochem 2010, 53:53-67. [CrossRef]

- Schromm AB, Brandenburg K, Loppnow H, Moran AP, Koch MH, Rietschel ET, Seydel U: Biological activities of lipopolysaccharides are determined by the shape of their lipid A portion. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS 2000, 267(7):2008-2013. [CrossRef]

- Gutsmann T, Howe J, Zahringer U, Garidel P, Schromm AB, Koch MH, Fujimoto Y, Fukase K, Moriyon I, Martinez-de-Tejada G et al: Structural prerequisites for endotoxic activity in the Limulus test as compared to cytokine production in mononuclear cells. Innate Immun 2010, 16(1):39-47. [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili JN: Thermodynamic principles of self-assembly. In: Intermolecular & Surface Forces. vol. 2. London, San Diego, New York, Boston, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto: Academic Press Ltd.; 1991: 341-365.

- Brandenburg K, Wiese A: Endotoxins: relationships between structure, function, and activity. CurrTopMedChem 2004, 4(11):1127-1146. [CrossRef]

- Andra J, Garidel P, Majerle A, Jerala R, Ridge R, Paus E, Novitsky T, Koch MH, Brandenburg K: Biophysical characterization of the interaction of Limulus polyphemus endotoxin neutralizing protein with lipopolysaccharide. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS 2004, 271(10):2037-2046. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg K: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy characterization of the lamellar and nonlamellar structures of free lipid A and Re lipopolysaccharides from Salmonella minnesota and Escherichia coli Biophys J 1993, 64:1215-1231.

- Howe J, Andra J, Conde R, Iriarte M, Garidel P, Koch MH, Gutsmann T, Moriyon I, Brandenburg K: Thermodynamic analysis of the lipopolysaccharide-dependent resistance of gram-negative bacteria against polymyxin B. Biophys J 2007, 92(8):2796-2805.

- Brandenburg K, David A, Howe J, Koch MH, Andra J, Garidel P: Temperature dependence of the binding of endotoxins to the polycationic peptides polymyxin B and its nonapeptide. Biophys J 2005, 88(3):1845-1858. [CrossRef]

- Garidel P, Brandenburg, K.: understanding of polymyxin B applications in bacteraemia/sepsis therapy prevention: Clinical, pharmaceutical, structural and mechanistic aspects. Anti-Infective Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 8(4):18. [CrossRef]

- Petrlova J, Samsudin F, Bond PJ, Schmidtchen A: SARS-CoV-2 spike protein aggregation is triggered by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. FEBS Lett 2022, 596(19):2566-2575. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Liao B, Cheng L, Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Hu T, Li J, Zhou X, Ren B: The microbial coinfection in COVID-19. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2020, 104(18):7777-7785. [CrossRef]

- Miesbach W, Makris M: COVID-19: Coagulopathy, Risk of Thrombosis, and the Rationale for Anticoagulation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2020, 26:1076029620938149. [CrossRef]

- Hadid T, Kafri Z, Al-Katib A: Coagulation and anticoagulation in COVID-19. Blood Rev 2021, 47:100761. [CrossRef]

- Jose RJ, Williams A, Manuel A, Brown JS, Chambers RC: Targeting coagulation activation in severe COVID-19 pneumonia: lessons from bacterial pneumonia and sepsis. Eur Respir Rev 2020, 29(157). [CrossRef]

- Szabo S, Zayachkivska O, Hussain A, Muller V: What is really ’Long COVID’? Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31(2):551-557.

- Natarajan A, Shetty A, Delanerolle G, Zeng Y, Zhang Y, Raymont V, Rathod S, Halabi S, Elliot K, Shi JQ et al: A systematic review and meta-analysis of long COVID symptoms. Syst Rev 2023, 12(1):88. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).