Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

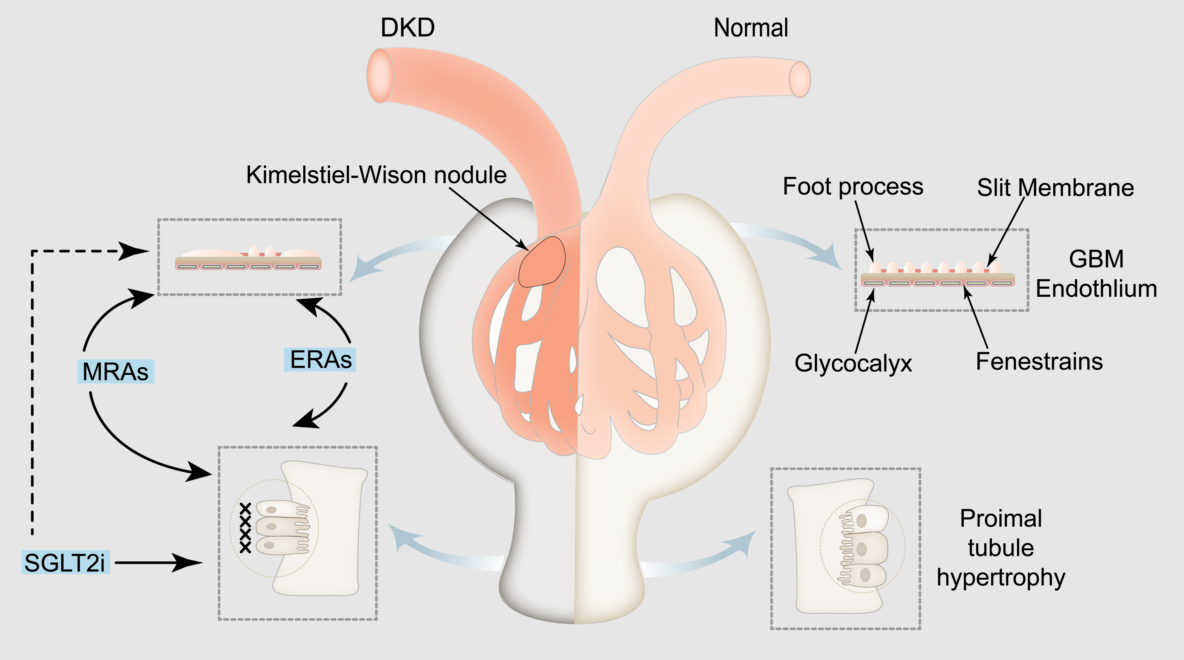

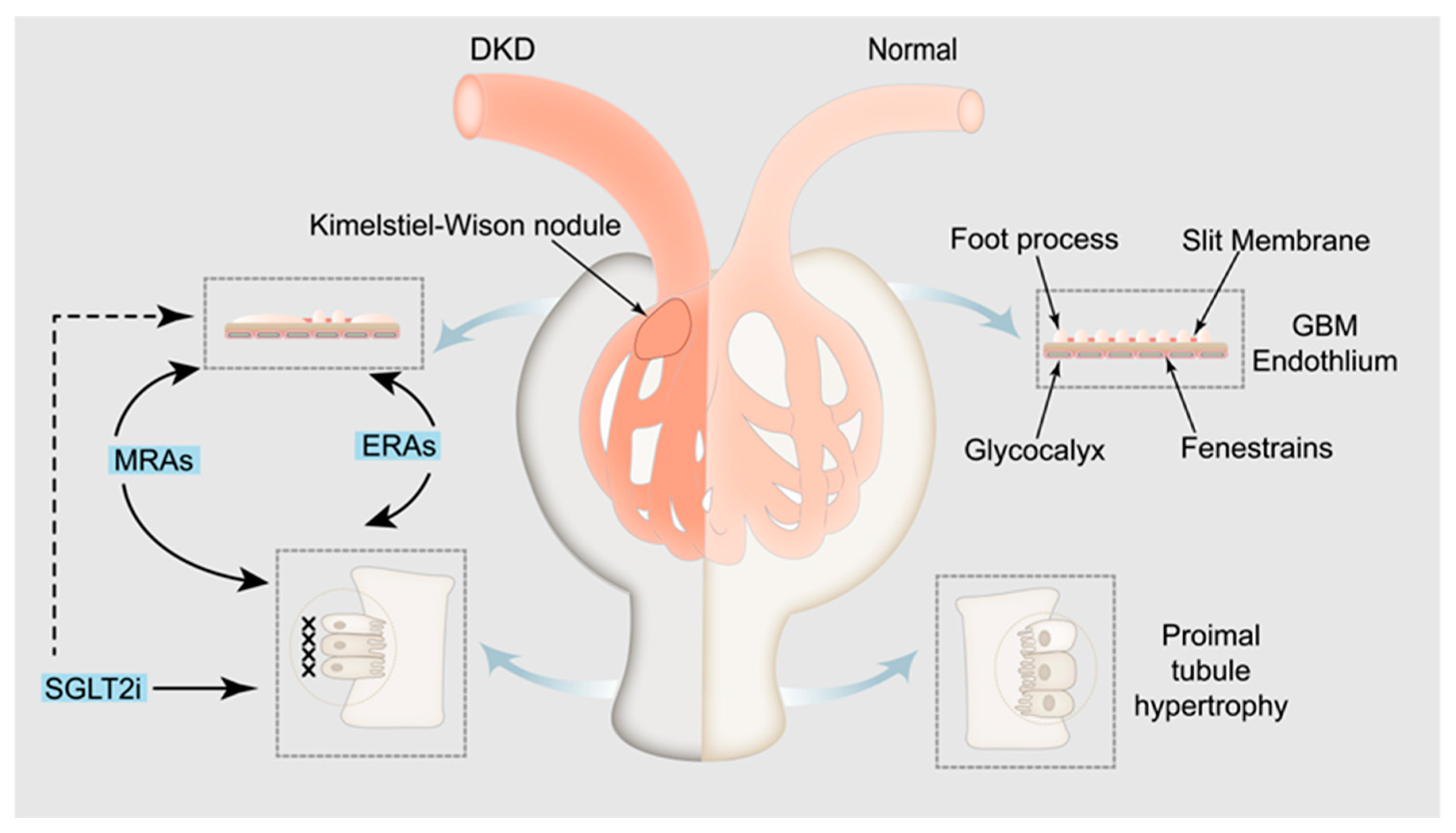

2. Pathophysiological mechanism of albuminuria in DKD

3. Role of albuminuria in the diagnosis and prognosis of DKD

4. Timing of control of albuminuria in patients with DKD

5. Treatment progress and mechanism of albuminuria in patients with DKD

5.1. SGLT2 i

5.2. MRAs

5.3. ERAs

5.4. Chinese patent medicine

5.4.1. Keluoxin capsule

5.4.2. Huangkui capsule

5.4.3. Tripterygium glycosides

5.4.4. Other Chinese patent medicine

5.5. Targeted precision therapy

6. Polydrug therapy for proteinuria in patients with T2DKD

7. Conclusion and prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y. C.; Chang, Y. H.; Yang, S. Y.; Wu, K. D.; Chu, T. S. Update of pathophysiology and management of diabetic kidney disease. J Formos Med Assoc 2018, 117, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFronzo, R. A.; Reeves, W. B.; Awad, A. S. Pathophysiology of diabetic kidney disease: impact of SGLT2 inhibitors. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021, 17, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, K. L.; Garimella, P. S.; Hicks, C. W.; Kalra, P. A.; Kelly, D. M.; Martens, S.; Matsushita, K.; Sarafidis, P.; Sood, M. M.; Herzog, C. A.; Cheung, M.; Jadoul, M.; Winkelmayer, W. C.; Reinecke, H. Central and peripheral arterial diseases in chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2021, 100, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyman, S. N.; Raz, I.; Dwyer, J. P.; Weinberg Sibony, R.; Lewis, J. B.; Abassi, Z. Diabetic Proteinuria Revisited: Updated Physiologic Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Hishikawa, A.; Hashiguchi, A.; Nakamichi, R.; Sugita-Nishimura, E.; Yoshida-Hama, E.; Azegami, T.; Nakayama, T.; Itoh, H. Significance of podocyte DNA damage and glomerular DNA methylation in CKD patients with proteinuria. Hypertens Res 2023, 46, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dai, W.; Liu, Z.; He, L. Renal Proximal Tubular Cells: A New Site for Targeted Delivery Therapy of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, N.; Han, H.; Li, X. Role of ion channels in the mechanism of proteinuria (Review). Exp Ther Med 2023, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Bohnert, B. N.; Grahammer, F.; Artunc, F. Rodent models to study sodium retention in experimental nephrotic syndrome. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2022, 235, e13844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Alshehri, M.; Desale, S.; Wilcox, C. The Effect of Amiloride on Proteinuria in Patients with Proteinuric Kidney Disease. Am J Nephrol 2021, 52, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, J.; Ruilope, L. M. Investigational calcium channel blockers for the treatment of hypertension. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2016, 25, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Castonguay, P.; Sidhom, E. H.; Clark, A. R.; Dvela-Levitt, M.; Kim, S.; Sieber, J.; Wieder, N.; Jung, J. Y.; Andreeva, S.; Reichardt, J.; Dubois, F.; Hoffmann, S. C.; Basgen, J. M.; Montesinos, M. S.; Weins, A.; Johnson, A. C.; Lander, E. S.; Garrett, M. R.; Hopkins, C. R.; Greka, A. A small-molecule inhibitor of TRPC5 ion channels suppresses progressive kidney disease in animal models. Science 2017, 358, 1332–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, G.; Wang, L.; Spurney, R. F. TRPC Channels in Proteinuric Kidney Diseases. Cells 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Yi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Pollock, C. A.; Chen, X. M. The KCa3.1 blocker TRAM34 reverses renal damage in a mouse model of established diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualdani, R.; Seghers, F.; Yerna, X.; Schakman, O.; Tajeddine, N.; Achouri, Y.; Tissir, F.; Devuyst, O.; Gailly, P. Mechanical activation of TRPV4 channels controls albumin reabsorption by proximal tubule cells. Sci Signal 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, T. J.; Pusch, M. CLC Chloride Channels and Transporters: Structure, Function, Physiology, and Disease. Physiol Rev 2018, 98, 1493–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, A.; Aziz, Q.; Li, Y.; Specterman, M. ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channels and Their Physiological and Pathophysiological Roles. Compr Physiol 2018, 8, 1463–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, M. H.; Volpini, R. A.; de Bragança, A. C.; Campos, R.; Canale, D.; Sanches, T. R.; Andrade, L.; Seguro, A. C. N-acetylcysteine attenuates renal alterations induced by senescence in the rat. Exp Gerontol 2013, 48, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrassy, K. M. Comments on 'KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease'. Kidney Int 2013, 84, 622–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, B.; Jiao, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, W.; Guo, W.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Can the Artificial Intelligence System for Urine Microalbuminuria Detection Monitor the Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease in the Clinical Laboratory? Diabetes Care 2022, 45, e136–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C. P.; Lott, E. H.; Lu, J. L.; Malakauskas, S. M.; Ma, J. Z.; Molnar, M. Z.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Outcomes associated with microalbuminuria: effect modification by chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 61, 1626–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velde, M.; Matsushita, K.; Coresh, J.; Astor, B. C.; Woodward, M.; Levey, A.; de Jong, P.; Gansevoort, R. T.; van der Velde, M.; Matsushita, K.; Coresh, J.; Astor, B. C.; Woodward, M.; Levey, A. S.; de Jong, P. E.; Gansevoort, R. T.; Levey, A.; El-Nahas, M.; Eckardt, K. U.; Kasiske, B. L.; Ninomiya, T.; Chalmers, J.; Macmahon, S.; Tonelli, M.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Sacks, F.; Curhan, G.; Collins, A. J.; Li, S.; Chen, S. C.; Hawaii Cohort, K. P.; Lee, B. J.; Ishani, A.; Neaton, J.; Svendsen, K.; Mann, J. F.; Yusuf, S.; Teo, K. K.; Gao, P.; Nelson, R. G.; Knowler, W. C.; Bilo, H. J.; Joosten, H.; Kleefstra, N.; Groenier, K. H.; Auguste, P.; Veldhuis, K.; Wang, Y.; Camarata, L.; Thomas, B.; Manley, T. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 2011, 79, 1341-52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addendum. 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022;45(Suppl. 1): S175-S184. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2182-2184.

- Levey, A. S.; Cattran, D.; Friedman, A.; Miller, W. G.; Sedor, J.; Tuttle, K.; Kasiske, B.; Hostetter, T. Proteinuria as a surrogate outcome in CKD: report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 2009, 54, 205–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, N.; Wu, B. T.; Yang, Y. W.; Huang, Z. H.; Feng, J. F. Re-understanding and focusing on normoalbuminuric diabetic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1077929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, M.; Shimizu, M.; Yamanouchi, M.; Toyama, T.; Hara, A.; Furuichi, K.; Wada, T. Trajectories of kidney function in diabetes: a clinicopathological update. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021, 17, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Marco, L.; Puchades, M. J.; Escudero-Saiz, V.; Giménez-Civera, E.; Terradez, L.; Moscardó, A.; Carbonell-Asins, J. A.; Pérez-Bernat, E.; Torregrosa, I.; Moncho, F.; Navarro, J.; Górriz, J. L. Renal Histologic Findings in Necropsies of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. J Diabetes Res 2022, 2022, 3893853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Qu, X.; Zhu, P.; Wo, F.; Xu, X.; Jin, J.; He, Q.; Wu, J. Integration of metabolomics and peptidomics reveals distinct molecular landscape of human diabetic kidney disease. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3188–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. A.; Simpson, K.; Lo Cicero, M.; Newbury, L. J.; Nicholas, P.; Fraser, D. J.; Caiger, N.; Redman, J. E.; Bowen, T. Detection of urinary microRNA biomarkers using diazo sulfonamide-modified screen printed carbon electrodes. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 18832–18839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B. M.; Cooper, M. E.; de Zeeuw, D.; Keane, W. F.; Mitch, W. E.; Parving, H. H.; Remuzzi, G.; Snapinn, S. M.; Zhang, Z.; Shahinfar, S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001, 345, 861–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, N. A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V. R.; Bannuru, R. R.; Brown, F. M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B. S.; Hilliard, M. E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E. L.; Kahan, S.; Khunti, K.; Leon, J.; Lyons, S. K.; Perry, M. L.; Prahalad, P.; Pratley, R. E.; Seley, J. J.; Stanton, R. C.; Gabbay, R. A.; on behalf of the American Diabetes, A., 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46 (Suppl 1), S191-s202.

- KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2022, 102, S1–s127. [CrossRef]

- Caruso, I.; Giorgino, F. SGLT-2 inhibitors as cardio-renal protective agents. Metabolism 2022, 127, 154937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskiet, M. H. A.; Wheeler, D. C.; Heerspink, H. J. L. New pharmacological strategies for protecting kidney function in type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019, 7, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaze, A. D.; Zhuo, M.; Kim, S. C.; Patorno, E.; Paik, J. M. Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular, kidney, and safety outcomes among patients with diabetic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forst, T.; Mathieu, C.; Giorgino, F.; Wheeler, D. C.; Papanas, N.; Schmieder, R. E.; Halabi, A.; Schnell, O.; Streckbein, M.; Tuttle, K. R. New strategies to improve clinical outcomes for diabetic kidney disease. BMC Med 2022, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Xu, J.; Zhou, S.; Xue, C.; Chen, Z.; Mao, Z. Influence of SGLT2i and RAASi and Their Combination on Risk of Hyperkalemia in DKD: A Network Meta-Analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2023, 18, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górriz, J. L.; Navarro-González, J. F.; Ortiz, A.; Vergara, A.; Nuñez, J.; Jacobs-Cachá, C.; Martínez-Castelao, A.; Soler, M. J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition: towards an indication to treat diabetic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020, 35 (Suppl 1), i13–i23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S. C.; Tendal, B.; Mustafa, R. A.; Vandvik, P. O.; Li, S.; Hao, Q.; Tunnicliffe, D.; Ruospo, M.; Natale, P.; Saglimbene, V.; Nicolucci, A.; Johnson, D. W.; Tonelli, M.; Rossi, M. C.; Badve, S. V.; Cho, Y.; Nadeau-Fredette, A. C.; Burke, M.; Faruque, L. I.; Lloyd, A.; Ahmad, N.; Liu, Y.; Tiv, S.; Millard, T.; Gagliardi, L.; Kolanu, N.; Barmanray, R. D.; McMorrow, R.; Raygoza Cortez, A. K.; White, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Rodríguez, A. F.; González-Colmenero, A. D.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Sutanto, S.; Solis, R. C.; Díaz González-Colmenero, F.; Rodriguez-Gutierrez, R.; Walsh, M.; Guyatt, G.; Strippoli, G. F. M. Sodium-glucose cotransporter protein-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Bmj 2021, 372, m4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E. D.; Bakris, G. L.; Rodbard, H. W.; Tuttle, K. R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetic kidney disease: A review of their kidney and heart protection. Am J Prev Cardiol 2023, 14, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotera, R.; Casarella, A.; Longhitano, E.; Bolignano, D.; Andreucci, M.; De Sarro, G.; Cernaro, V.; Russo, E.; Coppolino, G. Antiproteinuric effect of DPP-IV inhibitors in diabetic and non-diabetic kidney diseases. Pharmacol Res 2020, 159, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, P.; Baeres, F. M. M.; Bakris, G.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Gislum, M.; Gough, S. C. L.; Idorn, T.; Lawson, J.; Mahaffey, K. W.; Mann, J. F. E.; Mersebach, H.; Perkovic, V.; Tuttle, K.; Pratley, R. The rationale, design and baseline data of FLOW, a kidney outcomes trial with once-weekly semaglutide in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Albarrán, O.; Morales, C.; Pérez-Maraver, M.; Aparicio-Sánchez, J. J.; Simó, R. Review of SGLT2i for the Treatment of Renal Complications: Experience in Patients with and Without T2D. Diabetes Ther 2022, 13 (Suppl 1), 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiang, H.; Lu, Y.; Wu, T.; Ji, G. New progress in drugs treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 141, 111918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R. E.; Rao, P. S. S.; Churchwell, M. D.; Lewis, S. J. Novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2020, 29, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, A. M.; Knudsen, S. T.; Cooper, M. E. Diabetic nephropathy: an insight into molecular mechanisms and emerging therapies. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2019, 23, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogot-Levin, A.; Hinden, L.; Riahi, Y.; Israeli, T.; Tirosh, B.; Cerasi, E.; Mizrachi, E. B.; Tam, J.; Mosenzon, O.; Leibowitz, G. Proximal Tubule mTORC1 Is a Central Player in the Pathophysiology of Diabetic Nephropathy and Its Correction by SGLT2 Inhibitors. Cell Rep 2020, 32, 107954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. H.; Kim, N. H. Renoprotective Mechanism of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors: Focusing on Renal Hemodynamics. Diabetes Metab J 2022, 46, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, T.; Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Di Martino, A.; Albanese, G.; Di Salvo, J.; Epifani, R.; Marfella, R.; Docimo, G.; Lettieri, M.; Sardu, C.; Sasso, F. C. An Overview of the Cardiorenal Protective Mechanisms of SGLT2 Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, T. Signaling Pathways of Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Kidney Disease and the Effect of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durcan, E.; Ozkan, S.; Saygi, H. I.; Dincer, M. T.; Korkmaz, O. P.; Sahin, S.; Karaca, C.; Sulu, C.; Bakir, A.; Ozkaya, H. M.; Trabulus, S.; Guzel, E.; Seyahi, N.; Gonen, M. S. Effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on patients with diabetic kidney disease: A preliminary study on the basis of podocyturia. J Diabetes 2022, 14, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Xie, M.; Liu, H. Dapagliflozin delays renal fibrosis in diabetic kidney disease by inhibiting YAP/TAZ activation. Life Sci 2023, 322, 121671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dia, B.; Alkhansa, S.; Njeim, R.; Al Moussawi, S.; Farhat, T.; Haddad, A.; Riachi, M. E.; Nawfal, R.; Azar, W. S.; Eid, A. A. SGLT2 Inhibitor-Dapagliflozin Attenuates Diabetes-Induced Renal Injury by Regulating Inflammation through a CYP4A/20-HETE Signaling Mechanism. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, P.; Caramori, M. L.; Chan, J. C. N.; Heerspink, H. J. L.; Hurst, C.; Khunti, K.; Liew, A.; Michos, E. D.; Navaneethan, S. D.; Olowu, W. A.; Sadusky, T.; Tandon, N.; Tuttle, K. R.; Wanner, C.; Wilkens, K. G.; Zoungas, S.; Craig, J. C.; Tunnicliffe, D. J.; Tonelli, M. A.; Cheung, M.; Earley, A.; de Boer, I. H. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: an update based on rapidly emerging new evidence. Kidney Int 2022, 102, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, P.; Filippatos, G.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S. D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L. M.; Chan, J. C. N.; Kooy, A.; McCafferty, K.; Schernthaner, G.; Wanner, C.; Joseph, A.; Scheerer, M. F.; Scott, C.; Bakris, G. L. Finerenone in Predominantly Advanced CKD and Type 2 Diabetes With or Without Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitor Therapy. Kidney Int Rep 2022, 7, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, R. Finerenone: a new mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist to beat chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2022, 31, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KDIGO 2020 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2020, 98, S1–s115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Kolkhof, P.; Bakris, G.; Bauersachs, J.; Haller, H.; Wada, T.; Zannad, F. Steroidal and non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal medicine. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera-Chimal, J.; Jaisser, F.; Anders, H. J. The mineralocorticoid receptor in chronic kidney disease. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 3152–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Chimal, J.; Lima-Posada, I.; Bakris, G. L.; Jaisser, F. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in diabetic kidney disease - mechanistic and therapeutic effects. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Juanatey, J. R.; Górriz, J. L.; Ortiz, A.; Valle, A.; Soler, M. J.; Facila, L. Cardiorenal benefits of finerenone: protecting kidney and heart. Ann Med 2023, 55, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Ghanim, H.; Arora, P. Improving the residual risk of renal and cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic kidney disease: A review of pathophysiology, mechanisms, and evidence from recent trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2022, 24, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, P. Therapeutic perspective: evolving evidence of nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in diabetic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2023, 324, E531–e541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. L.; Lee, S. E.; Kim, N. H. Renal Protection of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist, Finerenone, in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2023, 38, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, R.; Xu, L.; Che, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, B. Cardiovascular-renal protective effect and molecular mechanism of finerenone in type 2 diabetic mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1125693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Ferro, C. J.; Balafa, O.; Burnier, M.; Ekart, R.; Halimi, J. M.; Kreutz, R.; Mark, P. B.; Persu, A.; Rossignol, P.; Ruilope, L. M.; Schmieder, R. E.; Valdivielso, J. M.; Del Vecchio, L.; Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Sarafidis, P. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists for nephroprotection and cardioprotection in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023, 38, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G. L.; Agarwal, R.; Chan, J. C.; Cooper, M. E.; Gansevoort, R. T.; Haller, H.; Remuzzi, G.; Rossing, P.; Schmieder, R. E.; Nowack, C.; Kolkhof, P.; Joseph, A.; Pieper, A.; Kimmeskamp-Kirschbaum, N.; Ruilope, L. M. Effect of Finerenone on Albuminuria in Patients With Diabetic Nephropathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2015, 314, 884–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Anker, S. D.; Bakris, G.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Rossing, P.; Ruilope, L.; Gebel, M.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Joseph, A. Investigating new treatment opportunities for patients with chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes: the role of finerenone. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022, 37, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H. J. L.; Jongs, N.; Neuen, B. L.; Schloemer, P.; Vaduganathan, M.; Inker, L. A.; Fletcher, R. A.; Wheeler, D. C.; Bakris, G.; Greene, T.; Chertow, G. M.; Perkovic, V. Effects of newer kidney protective agents on kidney endpoints provide implications for future clinical trials. Kidney Int 2023, 104, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H. J. L.; Parving, H. H.; Andress, D. L.; Bakris, G.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Hou, F. F.; Kitzman, D. W.; Kohan, D.; Makino, H.; McMurray, J. J. V.; Melnick, J. Z.; Miller, M. G.; Pergola, P. E.; Perkovic, V.; Tobe, S.; Yi, T.; Wigderson, M.; de Zeeuw, D. Atrasentan and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (SONAR): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, D.; Coll, B.; Andress, D.; Brennan, J. J.; Tang, H.; Houser, M.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Kohan, D.; Lambers Heerspink, H. J.; Makino, H.; Perkovic, V.; Pritchett, Y.; Remuzzi, G.; Tobe, S. W.; Toto, R.; Viberti, G.; Parving, H. H. The endothelin antagonist atrasentan lowers residual albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 25, 1083–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Fernandez-Prado, R.; Górriz, J. L.; Martinez-Castelao, A.; Navarro-González, J. F.; Porrini, E.; Soler, M. J.; Ortiz, A. Canagliflozin and Renal Events in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation and Study of Diabetic Nephropathy with Atrasentan: what was learned about the treatment of diabetic kidney disease with canagliflozin and atrasentan? Clin Kidney J 2019, 12, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H. J. L.; Xie, D.; Bakris, G.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Hou, F. F.; Kitzman, D. W.; Kohan, D.; Makino, H.; McMurray, J. J. V.; Perkovic, V.; Rossing, P.; Parving, H. H.; de Zeeuw, D. Early Response in Albuminuria and Long-Term Kidney Protection during Treatment with an Endothelin Receptor Antagonist: A Prespecified Analysis from the SONAR Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021, 32, 2900–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Qiao, C. Research progress on the role of ET-1 in diabetic kidney disease. J Cell Physiol 2023, 238, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Díaz, I.; Martos, N.; Llorens-Cebrià, C.; Álvarez, F. J.; Bedard, P. W.; Vergara, A.; Jacobs-Cachá, C.; Soler, M. J. Endothelin Receptor Antagonists in Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohan, D. E.; Barton, M. Endothelin and endothelin antagonists in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2014, 86, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeijer, J. D.; Kohan, D. E.; Webb, D. J.; Dhaun, N.; Heerspink, H. J. L. Endothelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of diabetic and nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2021, 30, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garsen, M.; Lenoir, O.; Rops, A. L.; Dijkman, H. B.; Willemsen, B.; van Kuppevelt, T. H.; Rabelink, T. J.; Berden, J. H.; Tharaux, P. L.; van der Vlag, J. Endothelin-1 Induces Proteinuria by Heparanase-Mediated Disruption of the Glomerular Glycocalyx. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016, 27, 3545–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, S. J. Diabetic nephropathy: Atrasentan stabilizes the endothelial glycocalyx. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinina, J.; Rippe, A.; Öberg, C. M. Sustained, delayed, and small increments in glomerular permeability to macromolecules during systemic ET-1 infusion mediated via the ETA receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 316, F1173–f1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanshan, C.; Huiru, C.; Hanbing, Y.; Xiaoxiao, L. Clinical study on Keluoxin Capsules combined with benazepril in treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Drugs & Clinic 2020, 35, 1763–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Xianhong, H.; Lei, L.; Xiaoya, C.; Yang, H. Protective effect of Keluoxin capsule on the renal tubules in patients with early diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Nephrol 2014, 14, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Qianqin, C.; Tao, H. Effect of keluoxin capsule combined with losartan potassium on elderly diabetic nephropathy and its effect on proteinuria. International Journal of Urology and Nephrology 2022, 42, 691–694. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine, C. A. o. I.; Medicine, C. A. o. C.; Association, C. M., Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Diabetic Kidney Disease with Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine https://www.cacm.org.cn/2023/05/31/23420/Preprint. In 2023.

- Society, C. D. Guideline for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China (2020 edition). Chin J Diabetes Mellitus 2021, 13, 315–409. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, A.; Romero, R.; Bayés, B.; Lopez, D.; Bonet, J. Is there a need for changes in renal biopsy criteria in proteinuria in type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2002, 58, 149–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenhua, Z. Efficacy and safety of Keluoxin capsule in combination with Western medicine for diabetic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 13, 1052852. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; Libo, T.; Hao, L.; Housheng, K.; Wei, L.; Yin, L.; Yanming, X.; Xin, C. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of Keluoxin capsule combined with chemical medicine in the treatment of diabetic kidney disease. China Pharmacy 2022, 33, 2124–2128. [Google Scholar]

- E, P., The impact of hyperfiltration on the diabetic kidney. Diabetes & metabolism 2015, 41, 5-17.

- Chunxue, Z.; Tianshu, G.; Fengnuan, Z.; Yiwen, L. Effect of Keluoxin Capsule on Early Hyperfiltration in Diabetic Kidney Disease Rats Based on Tubuloglomerular Feedback Mechanism. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 2023, 43, 822–830. [Google Scholar]

- L, L.; Q, N.; XM, L.; al, e. Study on Mechanism of Protection of Renal Structure and Function by Tangweikang Capsule in Diabetic Rats. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae 2000, 6, 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Wang, S.; Leng, X.; Yao, P.; Li, C.; Zheng, Y. Combining network pharmacology and in vitro and in vivo experiments to study the mechanism of Keluoxin in the treatment of radiation nephropathy†. J Radiat Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, A. H.; Zhang, B.; Ge, N.; Wang, X. J. Chinmedomics Strategy for Elucidating the Pharmacological Effects and Discovering Bioactive Compounds From Keluoxin Against Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 728256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huimin, Z.; Jiahui, X.; Qingguang, C.; Hao, L. Study on active ingredients and molecular mechanism of keluoxin in treatment of diabetic kidney disease based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. World Clinical Drugs 2023, 44, 468–476. [Google Scholar]

- XM, Y.; Q, Z.; XK, H.; Y, G.; Q, C., Effect of Keluoxin on Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response in the Kidney of Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy Rats Model. World Science and Technology-Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2023, 25, 1177-1185.

- Yang, X.; Han, X.; Wen, Q.; Qiu, X.; Deng, H.; Chen, Q. Protective Effect of Keluoxin against Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 2 Diabetic Mellitus Models. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021, 2021, 8455709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Ye, C.; Bayliss, G.; Zhuang, S. New Insights Into the Effects of Individual Chinese Herbal Medicines on Chronic Kidney Disease. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 774414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Li, R.; Zhou, P.; Li, N.; Xu, W.; Zhou, X.; Yan, Q.; Yu, J. Huobahuagen tablet improves renal function in diabetic kidney disease: a real-world retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1166880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Tostivint, I.; Xu, L.; Huang, J.; Gambotti, L.; Boffa, J. J.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Sun, Z.; Chen, X.; Liou-Schischmanoff, A.; Baumelou, A.; Ma, T.; Lu, G.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Piéroni, L.; Liu, B.; Qin, X.; He, W.; Wang, Y.; Gu, H. F.; Sun, W. Efficacy of Combined Abelmoschus manihot and Irbesartan for Reduction of Albuminuria in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Parallel Controlled Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, e113–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L. I.; Ping, X.; Wei, S.; Jing, Z.; Qiong, L.; Lianyi, G.; Yao, Z.; Kun, G. Effects of the Huangkui capsule on chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Tradit Chin Med 2023, 43, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Han, S.; Chai, C. Huangkui capsule alleviates doxorubicin-induced proteinuria via protecting against podocyte damage and inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 306, 116150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Tao, Y.; Tang, H.; Wu, C.; Fei, J.; Ge, H.; Gu, H. F.; Wu, J. Abelmoschus Manihot ameliorates the levels of circulating metabolites in diabetic nephropathy by modulating gut microbiota in non-obese diabetes mice. Microb Biotechnol 2023, 16, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L. Y.; Yun, S.; Tang, H. T.; Xu, Z. X. Huangkui capsule in combination with metformin ameliorates diabetic nephropathy via the Klotho/TGF-β1/p38MAPK signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 281, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Ma, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Tu, Y.; Huang, L.; Long, Y.; Wang, W.; Yee, H.; Wan, Z.; Tang, R.; Tang, H.; Wan, Y. Huangkui capsule alleviates renal tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and TLR4/NF-κB signaling. Phytomedicine 2019, 57, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. E.; Yu, P.; Wei, W.; Chen, X. Q. Efficacy of combined angiotensin II receptor blocker with tripterygium glycosides on diabetic nephropathy: A protocol for meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e25991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, C.; Zhao, Y. Wang, L.; Gao, J., Efficacy of tripterygium glycosides combined with ARB on diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Biosci Rep 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Li, K.; Ma, T.; Jiang, H.; Wang, F.; Huang, M.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, Y., Therapeutic Effect and Safety of Tripterygium Glycosides Combined With Western Medicine on Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Ther 2022, 44, 246-256.e10.

- Li, Y.; Miao, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dou, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Han, D. Efficacy and Safety of Tripterygium Glycoside in the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on the Duration of Medication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 656621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Deng, P.; Dong, C.; Lu, R.; Si, G.; Yang, T. Quality of Evidence Supporting the Role of Tripterygium Glycosides for the Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 1647–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S. L.; Lin, W.; Pan, R. H.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. F. Tripterygium glycoside tablet attenuates renal function impairment in diabetic nephropathy mice by regulating triglyceride metabolism. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022, 221, 115028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, C.; Ren, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X. Niaoduqing alleviates podocyte injury in high glucose model via regulating multiple targets and AGE/RAGE pathway: Network pharmacology and experimental validation. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1047184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Shang, Z.; Song, S.; Xu, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, G.; Yang, H. Adverse reactions of Niaoduqing granules: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine 2023, 109, 154535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Tang, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Tang, Y. Effects of Uremic Clearance Granules on p38 MAPK/NF-κB Signaling Pathway, Microbial and Metabolic Profiles in End-Stage Renal Disease Rats Receiving Peritoneal Dialysis. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 2529–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, D.; He, W.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, S.; He, Q.; Jin, J. Yi-Shen-Hua-Shi granules inhibit diabetic nephropathy by ameliorating podocyte injury induced by macrophage-derived exosomes. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 962606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Shen, Z.; Cui, T.; Ai, S. S.; Gao, R. R.; Liu, Y.; Sui, G. Y.; Hu, H. Z.; Li, W. Yi-Shen-Hua-Shi granule ameliorates diabetic kidney disease by the "gut-kidney axis". J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 307, 116257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, G. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Jinshuibao Combined With ACEI/ARB in the Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Ren Nutr 2020, 30, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, C.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Q. Efficacy of Jinshuibao as an adjuvant treatment for chronic renal failure in China: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e34575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yan, D.; Lan, Q.; Fang, J.; Ding, Z.; Guan, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yan, L.; Nie, H. Efficacy and Safety of Jinshuibao Capsule in Diabetic Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Comput Math Methods Med 2022, 2022, 9671768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Chang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, M.; Mi, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Liao, X. The effects of Ophiocordyceps sinensis combined with ACEI/ARB on diabetic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine 2023, 108, 154531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X.; Li, M.; Yu, M.; Ping, F. Bailing capsule (Cordyceps sinensis) ameliorates renal triglyceride accumulation through the PPARα pathway in diabetic rats. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 915592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, K.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X. Effects of Bailing capsule on diabetic nephropathy based on UPLC-MS urine metabolomics. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 35969–35975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, H.; Han, S. Economic evaluation of bailing capsules for patients with diabetic nephropathy in China. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1175310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Ma, J.; Leng, T.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, T.; Liu, Q.; Shen, T. Advances in oxidative stress in pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease and efficacy of TCM intervention. Ren Fail 2023, 45, 2146512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Huang, M.; Jiang, J.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Meng, R.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Panax notoginseng preparations as adjuvant therapy for diabetic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharm Biol 2020, 58, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Q.; Chen, Q.; Xue, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. Network pharmacology combined with metabolomics to study the mechanism of Shenyan Kangfu Tablets in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 270, 113817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ren, D.; Wu, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, T. Shenyan Kangfu tablet alleviates diabetic kidney disease through attenuating inflammation and modulating the gut microbiota. J Nat Med 2021, 75, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Zhao, K.; Huang, Q.; Tang, S.; Chen, K.; Xie, C.; Zhang, C.; Gan, W. A randomized controlled clinical trial study protocol of Liuwei Dihuang pills in the adjuvant treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e21137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gao, L.; Deng, R.; Peng, Y.; Wu, S.; Lu, J.; Liu, X. Huangqi-Danshen decoction reshapes renal glucose metabolism profiles that delays chronic kidney disease progression. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 164, 114989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wang, C.; Bai, D.; Chen, N.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J. Perspectives of international multi-center clinical trials on traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1195364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Miao, R.; Yu, T.; Wei, R.; Tian, F.; Huang, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhao, L. Comparative effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and sodium glucose cotransporter inhibitors in patients with diabetic kidney disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res 2022, 177, 106111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Dai, W.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, L. Targeted drug delivery strategy: a bridge to the therapy of diabetic kidney disease. Drug Deliv 2023, 30, 2160518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raval, N.; Jogi, H.; Gondaliya, P.; Kalia, K.; Tekade, R. K. Method and its Composition for encapsulation, stabilization, and delivery of siRNA in Anionic polymeric nanoplex: An In vitro- In vivo Assessment. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 16047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, G.; Al-Trad, B.; Hamdan, S.; Aljabali, A.; Al-Zoubi, M.; Bataineh, N.; Qar, J.; Tambuwala, M. M. Gold nanoparticles attenuate albuminuria by inhibiting podocyte injury in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2020, 10, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Xu, H. L.; Chen, P. P.; Zheng, L.; Huang, Q.; Sheng, W. S.; Zhuang, Y. D.; Jiao, L. Z.; Chi, T. T.; ZhuGe, D. L.; Liu, J. J.; Zhao, Y. Z.; Lan, L. Combination of coenzyme Q10-loaded liposomes with ultrasound targeted microbubbles destruction (UTMD) for early theranostics of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Pharm 2017, 528, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, J.; Maumus-Robert, S.; Bezin, J. Polypharmacy: A general review of definitions, descriptions and determinants. Therapie 2020, 75, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards of medical care in diabetes--2014. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (Suppl 1), S14–80. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, I. H.; Khunti, K.; Sadusky, T.; Tuttle, K. R.; Neumiller, J. J.; Rhee, C. M.; Rosas, S. E.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G. Diabetes management in chronic kidney disease: a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2022, 102, 974–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes and CKD: 2012 Update. Am J Kidney Dis 2012, 60, 850–86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steuber, T. D.; Lee, J.; Holloway, A.; Andrus, M. R. Nondihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers for the Treatment of Proteinuria: A Review of the Literature. Ann Pharmacother 2019, 53, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M. A.; Bakris, G. L.; Jamerson, K.; Weir, M.; Kjeldsen, S. E.; Devereux, R. B.; Velazquez, E. J.; Dahlöf, B.; Kelly, R. Y.; Hua, T. A.; Hester, A.; Pitt, B. Cardiovascular events during differing hypertension therapies in patients with diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010, 56, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D. S. H. Combine and Conquer: With Type 2 Diabetes Polypharmacy Is Essential Not Only to Achieve Glycemic Control but Also to Treat the Comorbidities and Stabilize or Slow the Advancement of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res 2022, 2022, 7787732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. S. H.; Goncalves, E. Diabetogenic effects of cardioprotective drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021, 23, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperidou, A.; Sarafidis, P.; Boutou, A.; Thomopoulos, C.; Loutradis, C.; Alexandrou, M. E.; Tsapas, A.; Karagiannis, A. The effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on albuminuria and proteinuria in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2019, 37, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Anker, S. D.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Rossing, P.; Ruilope, L. M.; Boletis, J.; Toto, R.; Umpierrez, G. E.; Wanner, C.; Wada, T.; Scott, C.; Joseph, A.; Ogbaa, I.; Roberts, L.; Scheerer, M. F.; Bakris, G. L. Effects of canagliflozin versus finerenone on cardiorenal outcomes: exploratory post hoc analyses from FIDELIO-DKD compared to reported CREDENCE results. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022, 37, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, J. In A new approach to kidney protection in patients with type 2 diabetes, EASD Meeting, Munich, Germany, 2021; Munich, Germany, 2021.

- Stuart, D.; Peterson, C. S.; Hu, C.; Revelo, M. P.; Huang, Y.; Kohan, D. E.; Ramkumar, N. Lack of renoprotective effects of targeting the endothelin A receptor and (or) sodium glucose transporter 2 in a mouse model of Type 2 diabetic kidney disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2022, 100, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batu Demir, D.; Cooper, M. E. New strategies to tackle diabetic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2016, 25, 348–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drugs | Therapeutic Mechanisms for Albuminuria in DKD | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SGLT-2 Inhibitors |

|

1. [33,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] 2. [2,49,50] 3. [51,52] |

| Nonsteroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists | Instead of aldosterone and MR, leading to a proinflammatory and fibrosis of gene expression. | [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] |

| Endothelin Receptor Antagonists | It binds to ET-1 to protect the glomerular filtration barrier and reverse glomerular hyperfiltration ang improve renal fibrosis. | [77,78,79] |

| Keluoxin Capsule |

|

1. [88,89,90] 2. [91,92,93,94] 3. [95] |

| Huangkui Capsule |

|

1. [100] 2. [101] 3. [102,103] |

| Tripterygium Glycosides | It can promote the decomposition of renal triglyceride and improve the damaged renal function. | [109] |

| Niaoduqing granule |

|

1. [110] 2. [112] |

| Yishen Huashi granule |

|

1. [113] 2. [114] |

| Cordyceps sinensis preparation |

|

1. [119] 2. [120] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).