1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized the medical-scientific field in just a few years, allowing for significant changes and integration of diagnostic, therapeutic and patient care pathways [

1]. Although at first it was mainly represented by the development of Machine Learning (ML) models [

2], further advances such as Deep Learning (DL) with, among others, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) soon came to the fore [

3]. A branch of AI includes conversational artificial intelligence, which has experienced unprecedented development in recent years, with numerous models and platforms developed to enable machines to understand and respond to natural language input [

4]. In more detail, a chatbot is an item of software that simulates and develops human conversations (spoken or written), allowing users to interact with digital devices as though they were speaking with real people [

5]. Chatbot might be as basic as a programme that responds to a single enquiry or as complex as a digital assistant that learns and develops as it gathers and elaborates information to provide more and higher levels of personalization [

6]. The chatbots designed specifically for activities (declarational) are ‘

single-purpose’ softwares that focus on carrying out a certain function; regulated responses to user requests are generated using Natural Language Process (NLP) and very little machine learning [

7]. The interactions with these chatbots are quite particular and structured, and they are best suited for assistance and service functions like frequently asked and consolidated questions. Common questions can be managed by activity-specific chatbots, such as inquiries about working hours or straightforward transactions that don't involve many variables. Even while they employ NLP in a way that allows users to experiment with it easily, their capabilities are still somewhat limited. These are the most popular chatbots right now [

7]. Virtual assistants, also known as digital assistants or data-driven predictive (conversational) chatbots, are significantly more advanced, interactive, and customized than task-specific chatbots. These chatbots use ML, NLP and context awareness to learn. They employ data analysis and predictive intelligence to offer customization based on user profiles and past user behaviour. Digital assistants can gradually learn a user's preferences, make suggestions, and even foresee needs. They can start talks in addition to monitoring data and rules. Predictive chatbots that focus on the needs of the user and are data-driven include Apple's Siri and Amazon's Alexa [

8].

A clear example of such an approach is Chat GPT, an acronym for Generative Pretrained Transformer, a powerful and versatile natural language processing (or Natural Language Processing) tool that uses advanced machine learning algorithms to generate human-like responses within a conversation (

https://chat.openai.com). Released on 30 November 2022 by OpenAI, Chat GPT was trained until the end of 2021 on more than 300 billion words, with the ability to respond on a huge variety of topics and with the ability to learn from its human interlocutor [

9]. Released on 30 November 2022 by OpenAI (San Francisco, CA), Chat GPT was trained until the end of 2021 on more than 300 billion words, with the ability to respond on a huge variety of topics and with the ability to learn from its human interlocutor [

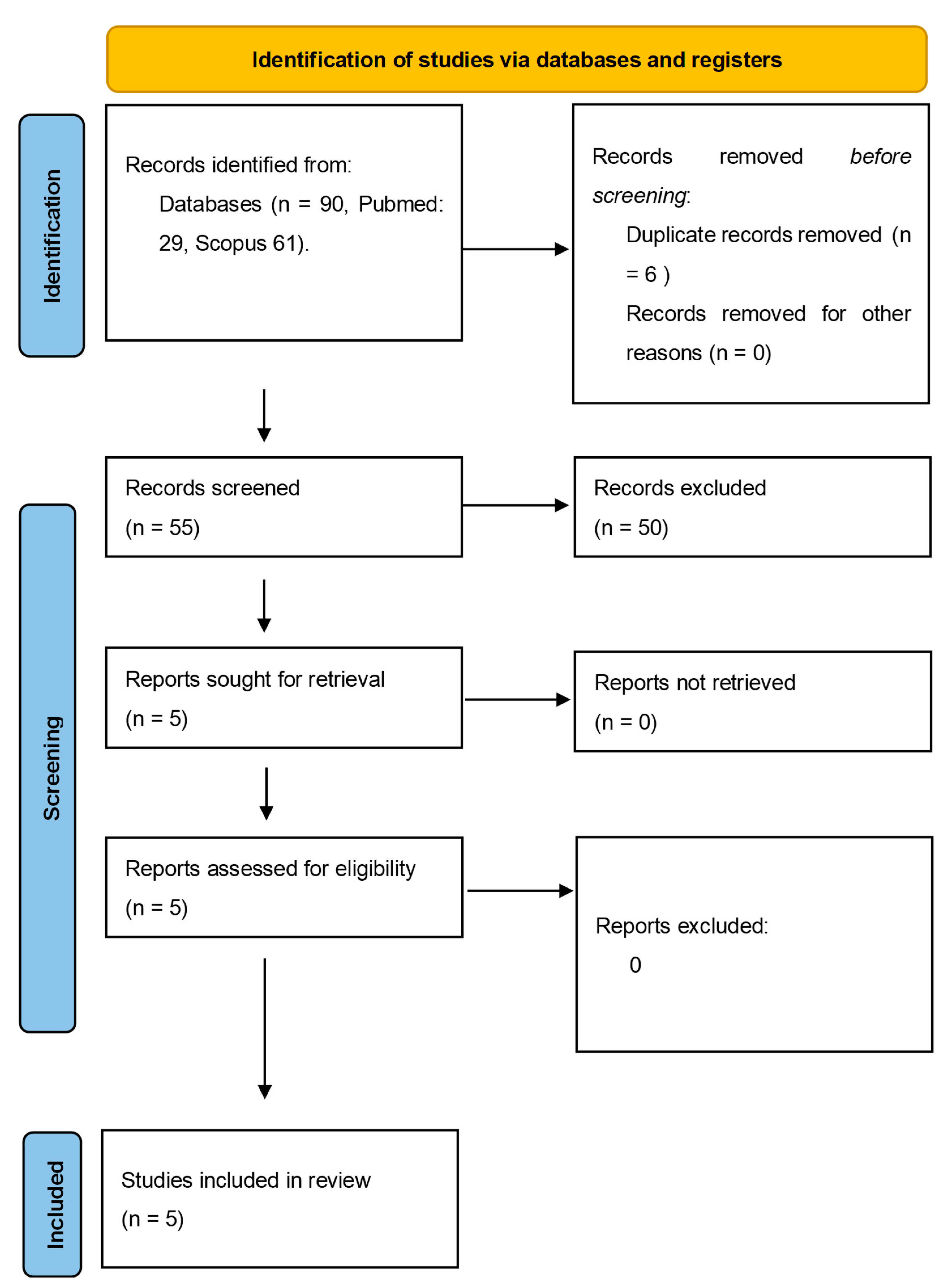

9]. In the first few months after its official launch, many papers were published in the purely informatic field, but, as the weeks went by, the medical-scientific field was also interested, with a particular interest in education, research and simulation of clinical pictures of patients, as well as applications in hygiene and public health, clinical medicine, oncology and surgery. In this narrative review, however, we focus on the potential use of Chat GPT in Pathological Anatomy, discuss the fields of application studied so far and try to outline future perspectives, with particular regard to present limitations.

4. Discussion

The application of AI to medicine has significantly co-assisted the physician's therapeutic decision-making processes, not replacing, but complementing and enhancing the indispensable figure of the human [

10]. The advent of Chat GPT has further enabled a breakthrough in Large Language Models (LLM) that enable the simulation of a real conversation on a wide variety of topics, including medical-scientific notions [

11]. If in the early months the field of application was mostly restricted to clinical medicine, in recent times a number of papers have studied, tested and commented on the applicability of Chat GPT in the field of human pathology, making it possible to outline its real usefulness and current limitations.

The article by Sinha et al. [

12] describes a study conducted on ChatGPT's ability to resolve complex rationality problems in the area of human pathology. Based on the clear finding that AI is used to analyze medical images, such as histopathologic slides, in order to identify and diagnose diseases with high precision, the authors take a cautious approach to the fact that NLP algorithms are used to analyze the relationships between pathologies, extract relevant information, and aid in disease diagnosis. The goal of the study was to assess ChatGPT's ability to address high-level rational questions in the field of pathology. 100 questions that were randomly chosen from a bank of inquiries regarding diseases and divided into 11 different systems of pathology were used. Experts have evaluated the responses provided by ChatGPT using both a scale of 0 to 5 and the tassonomy SOLE to assess the depth of understanding demonstrated in the responses.

The outcomes have shown that the responses provided by ChatGPT achieve a reasonable level of rationality, with a score similar to four on five. This means that the AI is capable of correctly responding to high-level inquiries requiring in-depth knowledge of the subject. The report also highlights the limitations of AI in diagnosing disease. Although it is possible to recognize schemes and categorize data, a true understanding of the underlying significance and context of the information is lacking. L'AI is unable to make logical judgements or evaluative decisions because it lacks the ability to comprehend personal values and judgements. Therefore, it is suggested that careful consideration should be given to the use of AI in medical education, with the goal of assisting human judgement rather than replacing it.

There are some limitations to the study, including the subjective nature of the evaluation procedure and the selection of particular questions from a single bank of data. The authors suggest that in order to obtain results that are more generally applicable, future studies may be conducted on a larger sample size and by a variety of institutions.

In the paper by Sorin V. et al [

13], the authors discuss how ChatGPT 3.5 can also operate within the molecular tumour board, not only starting from histopathological/diagnostic data, but also integrating other key components such as genetic, molecular, response and/or prediction of treatment response and prognosis data. Ten consecutive cases of women with breast cancer were considered and an attempt was made to assess how consistent the recommendations provided by the chatbot were with those of the tumour board. The results showed that ChatGPT's clinical recommendations were in line with those of the oncology committee in 70% of the cases, with concise clinical case summaries and explained and reasoned conclusions. However, the lowest scores (which were given by the second reviewer) were for the clinical recommendations of the chatbot, suggesting that deciding on clinical treatment from pathological/molecular data is highly challenging, requiring medical understanding and experience in the field. Furthermore, it was curious to note that ChatGPT never mentioned the role of medical radiologists, suggesting the importance (and consequent risk of bias) that incomplete training may influence the performance, and thus the responses, of the chatbot.

In another recent paper by Naik H.R. et al [

14], the authors described the case of a 58-year-old woman with bilateral synchronous breast cancer (s-BBC) who underwent bilateral mastectomy, sentinel lymph node biopsy (BLS), axillary lymphadenectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemo/hormonotherapy. The particularity of the paper was related to the so-called 'hallucination phenomenon', i.e. a clear and confident response from ChatGPT but which is not real. One of the authors of the paper (Dr. Gurda), when asking the chatbot about s-BBC, noted that although the answer was plausible, the reference provided did not exist, although there were articles with similar information and authors.

This aspect is well addressed by the paper by Metze K. et al [

15] who conducted a study to assess the ability of ChatGPT to contribute to a review on Chagas disease, focusing on the role of individual researchers. Therefore, 50 names of researchers with at least 4 publications on Chagas disease were selected from Clarivate's Web of Sciences (WoS) database and for each researcher, the chatbot was asked to provide conceptual contributions related to the study of the disease. The answers were checked by two observers against the literature, and incorrect information was removed. The percentage of correct words in the text generated by ChatGPT was calculated and the literature references were classified into three categories: completely correct, minor errors and major errors.

The results showed that the average percentage of correct words in the text generated by ChatGPT was 59.4%, but the variation was wide, ranging from 10.0% to 100.0%. A positive correlation was observed between the percentage of correct words and the number of indexed publications of each author of interest, as well as with the number of citations and the author's H-index. However, the percentage of correct references was very low, averaging 7.07%, and both minor and major errors were found in the references.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that ChatGPT is still not a reliable source of literature review, especially in more specific areas with a relatively low number of publications, as there are still accuracy and misinformation issues to be addressed, especially in the field of medicine.

Yamin Ma [

16], in a paper of July 2023, discusses the application of ChatGPT in the context of gastrointestinal pathology, hypothesizing three possible applications for ChatGPT: 1) Ability to summarize patient records: ChatGPT could be integrated into the patent table to summarize patients' previous clinical information, helping pathologists better understand patients' current health status and saving time before case reviews.

2) Incorporation into digital pathology: ChatGPT could improve the interpretation of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems in gastrointestinal pathology. It would enable pathologists to ask specific questions on digitized images and obtain knowledge-based answers associated with diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis.

3) Role in education and research: ChatGPT could be used for health education, offering scientific explanations associated with medical terms in pathology. However, attention should be paid to the quality of the training data to avoid biased content and inaccurate information. The use of ChatGPT in research also requires caution as it may be insufficient or misleading.

Finally, the paper emphasizes that while recognizing the potential of ChatGPT, it is important to proceed with caution when using artificial intelligence-based technologies such as ChatGPT in gastrointestinal pathology. The aim should be to integrate such language models in a regulated and appropriate manner, exploiting their advantages to improve the quality of healthcare without replacing human expertise and without ignoring expert consultation in particular cases.

From what has been discussed so far and bearing in mind a paper published five days ago [

17], it would appear that at present, the use of ChatGPT in pathology is still in its early stages. In particular, with regard to ChatGPT version 3.5, it seems clear that the amount of data on which the algorithm has been trained plays a key role in its ability to provide correct answers to certain prompts. In particular, several papers have warned of the risk of possible bias and transparency issues [

18,

19] and of damage resulting from inaccurate or outright incorrect content [

20,

21,

22,

23]. One of the most problematic phenomena is hallucination, as ChatGPT seems, at present, to produce correct scientific content but not to direct the content itself to a real source/reference. Therefore, its use in pathology and, more generally, in scientific research must necessarily take these limitations into account [

24].

Moreover, projecting to a future in which systems may become more performant, the integration with clinical, genetic, anamnestic, morphological and immunohistochemical data, which have always characterised the pathologist's life, will always have to be screened by medical experience and knowledge, areas in which ChatGPT struggles most.