Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

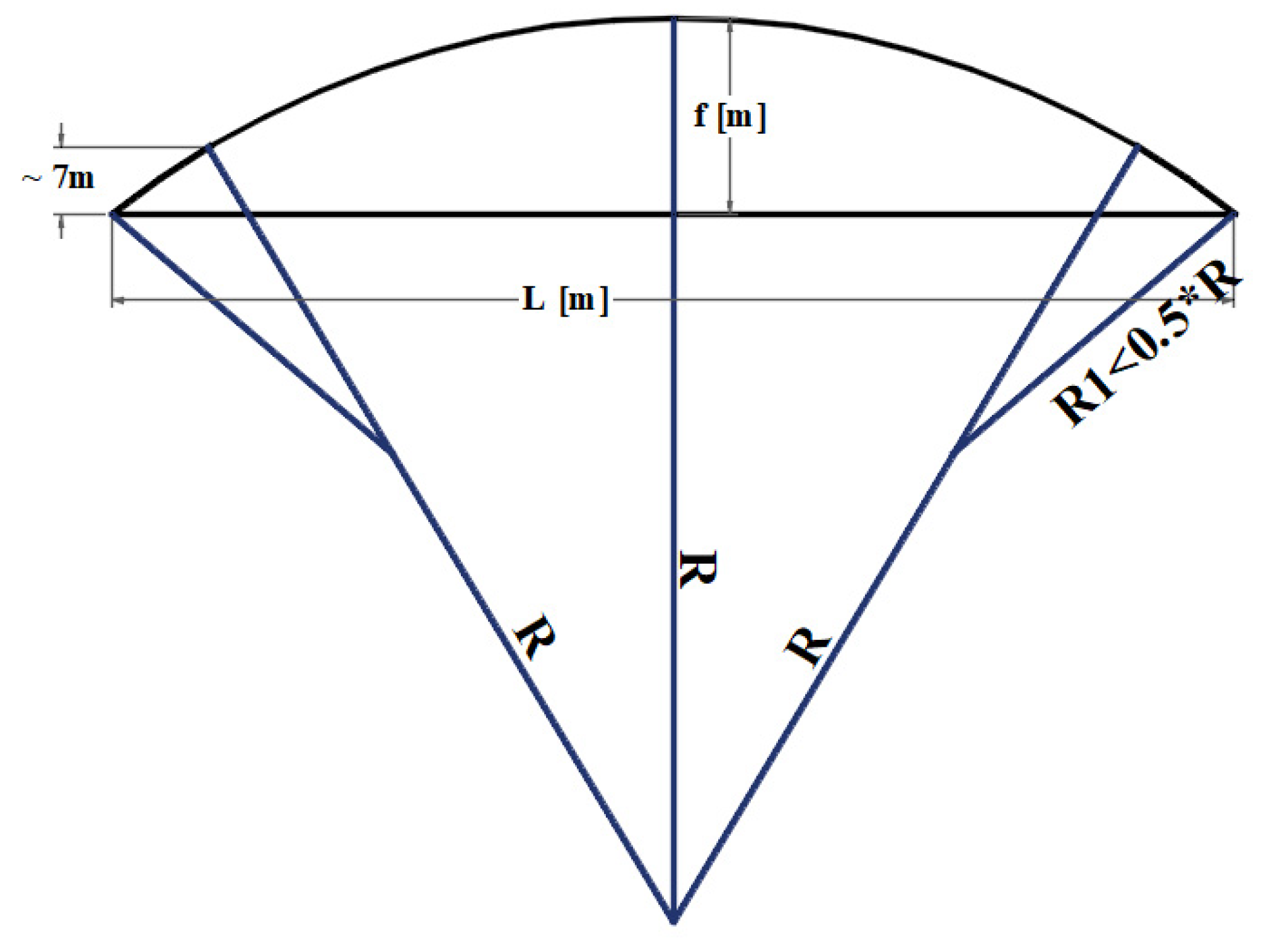

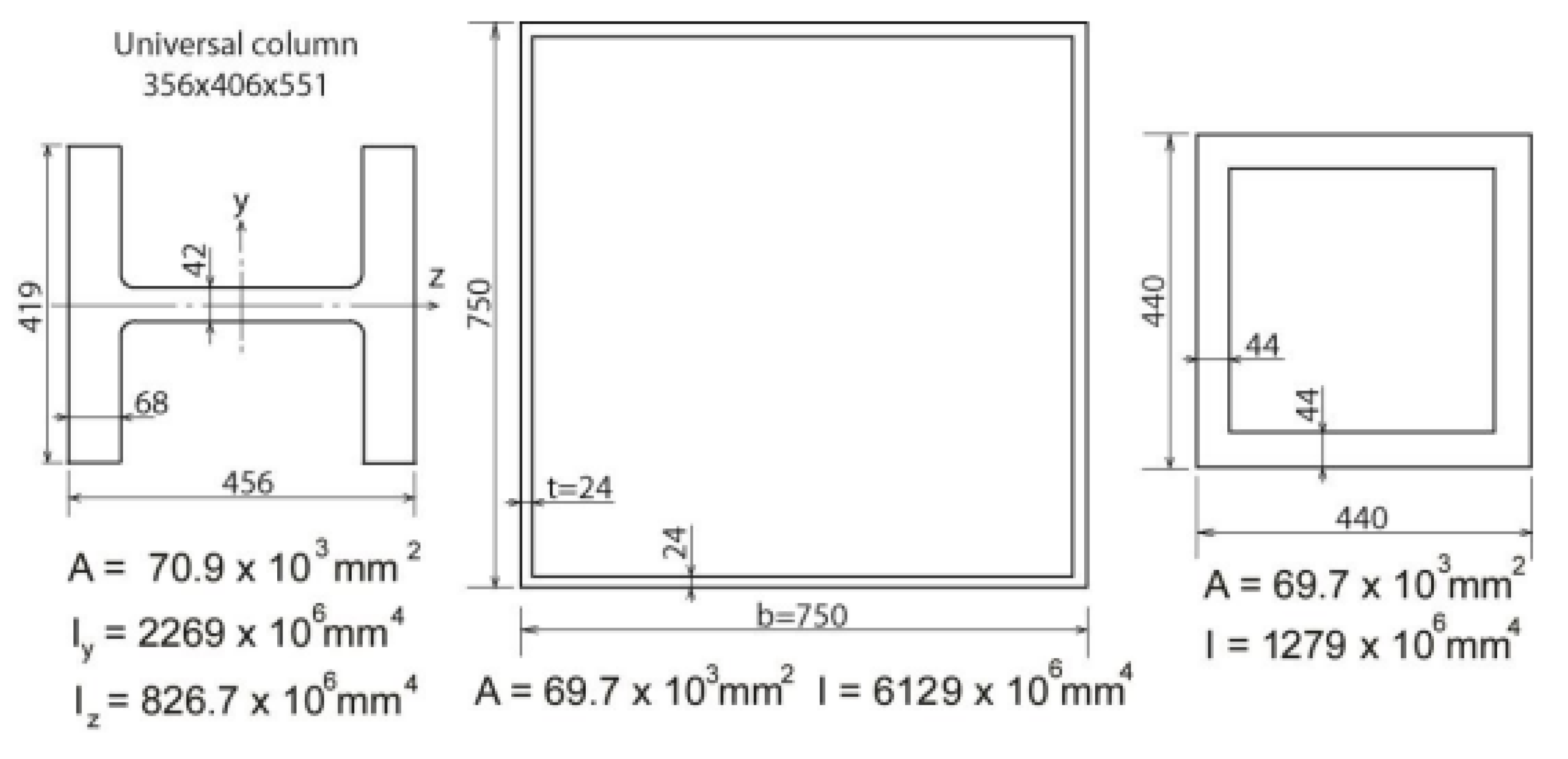

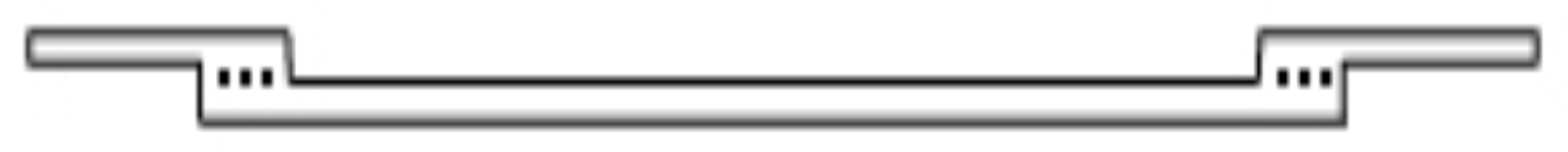

2. Per Tveit vision and conception of the Network Arch Bridge

3. Network Arch Bridges of different structural systems around the world

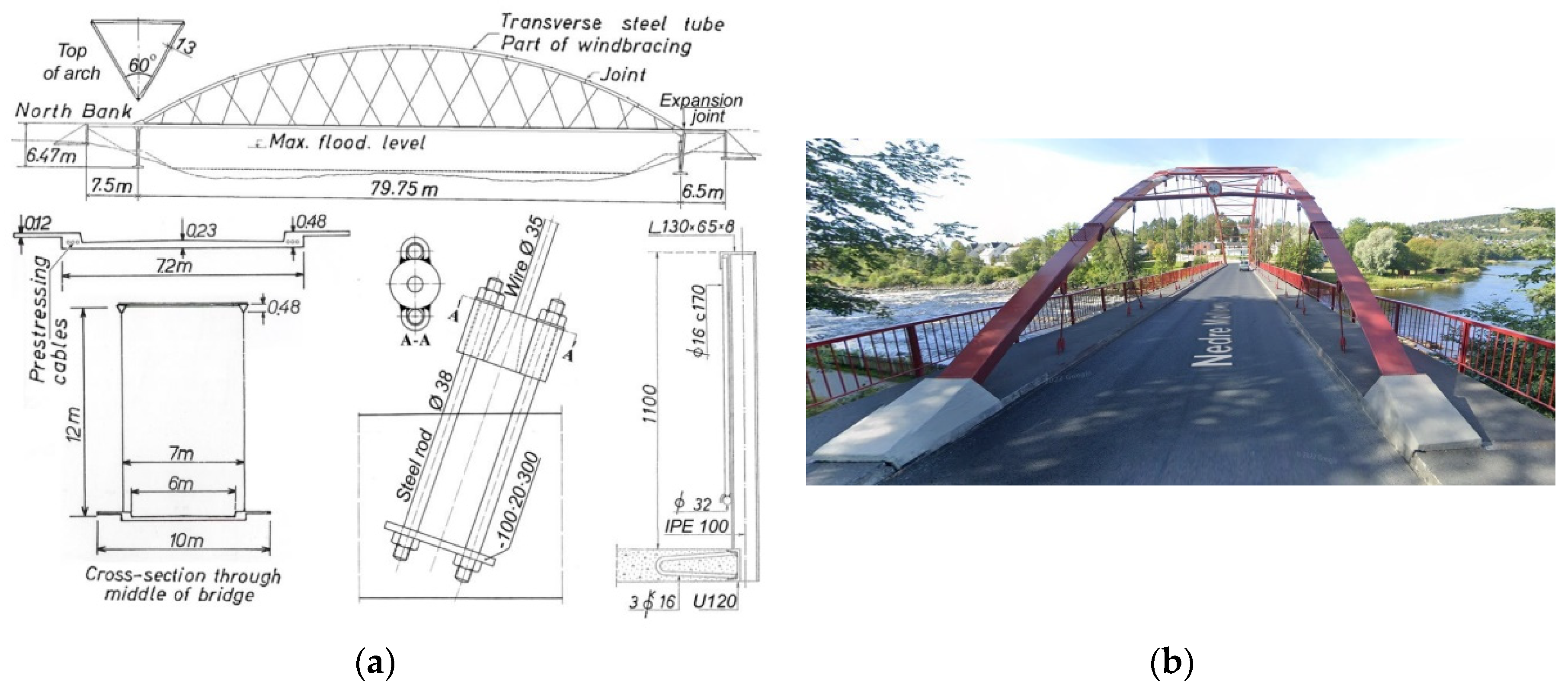

3.1. The Network Arch at Steinkjer

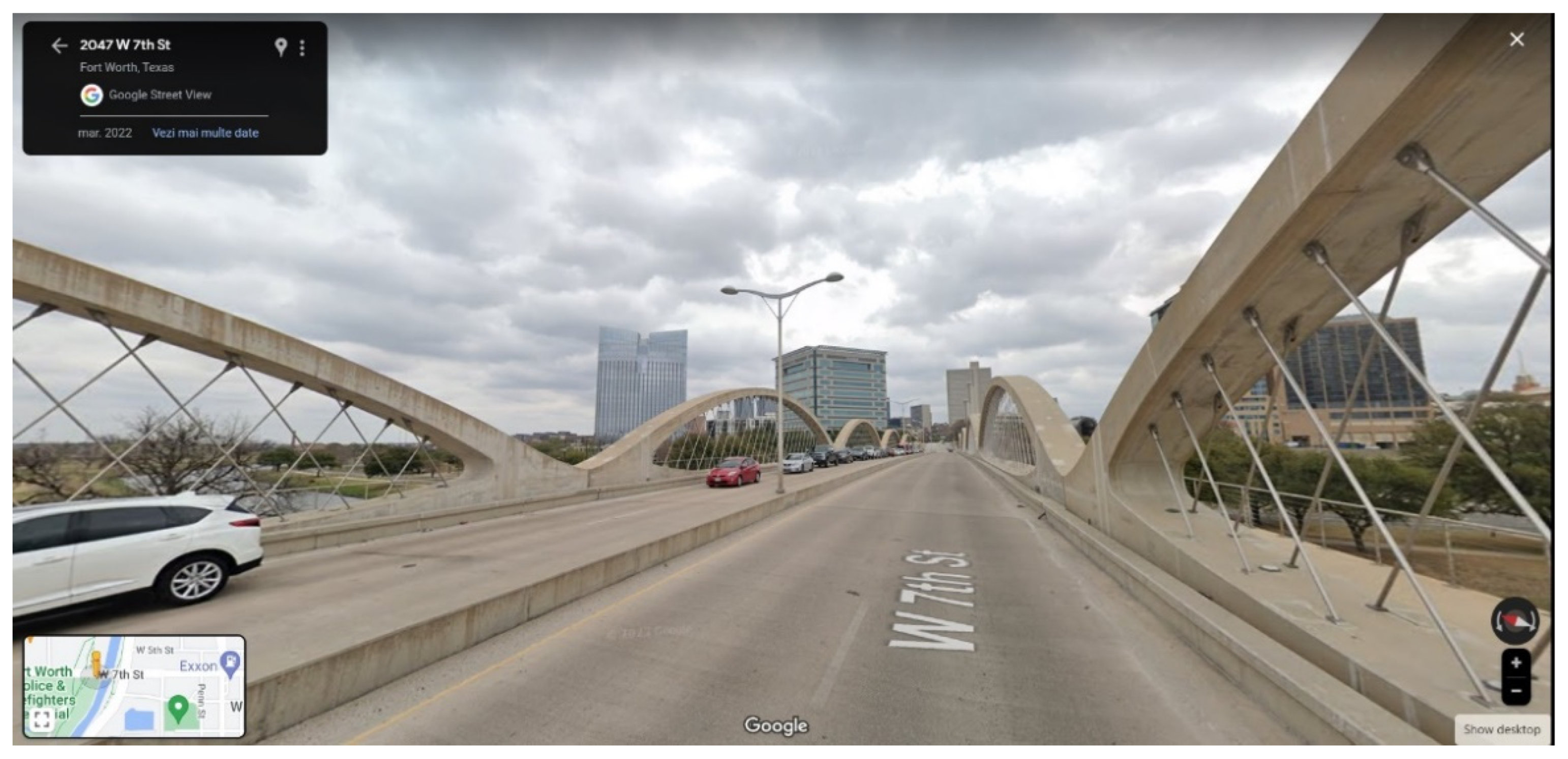

3.2. The West Seven Street Bridge, Forth Worth, Texas

3.3. Troja Bridge in Prague

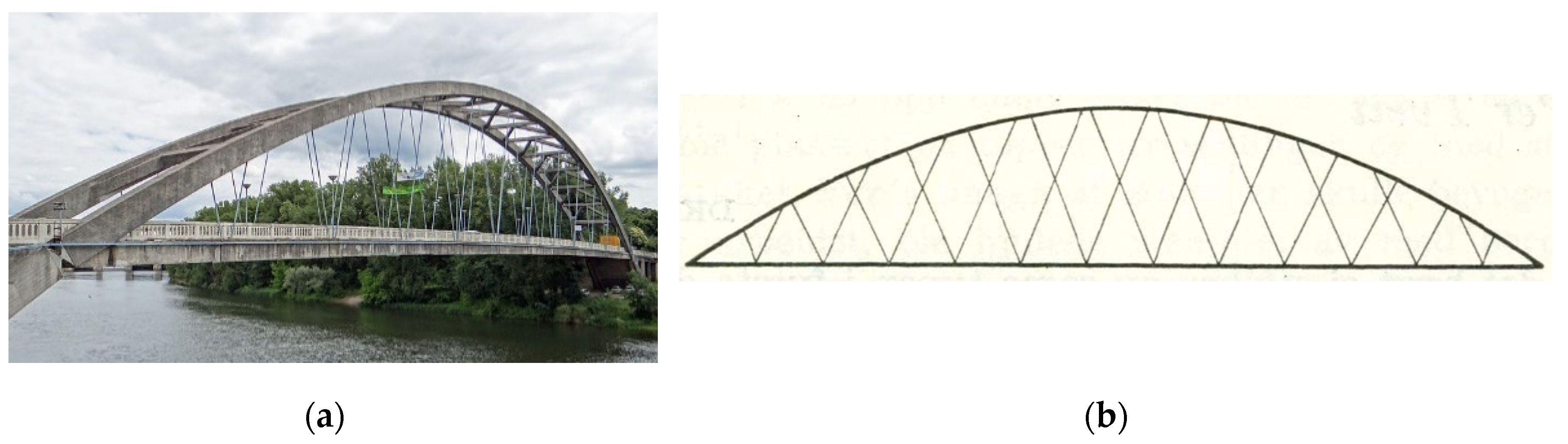

3.4. Sixth Street Viaduct

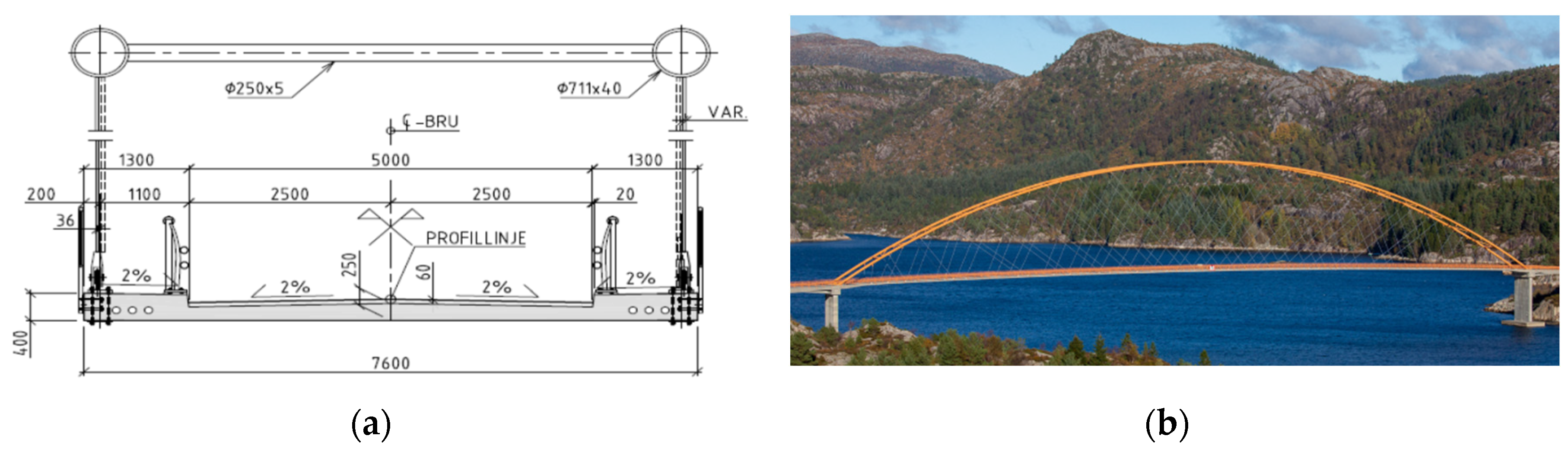

3.5. Brandanger Bridge

3.6. Palma del Rio Bridge

3.7. Deba River Bridge

3.8. Stuttgart Stadtbahn Bridge

3.9. Zezelj Bridge (Novi Sad Bridge)

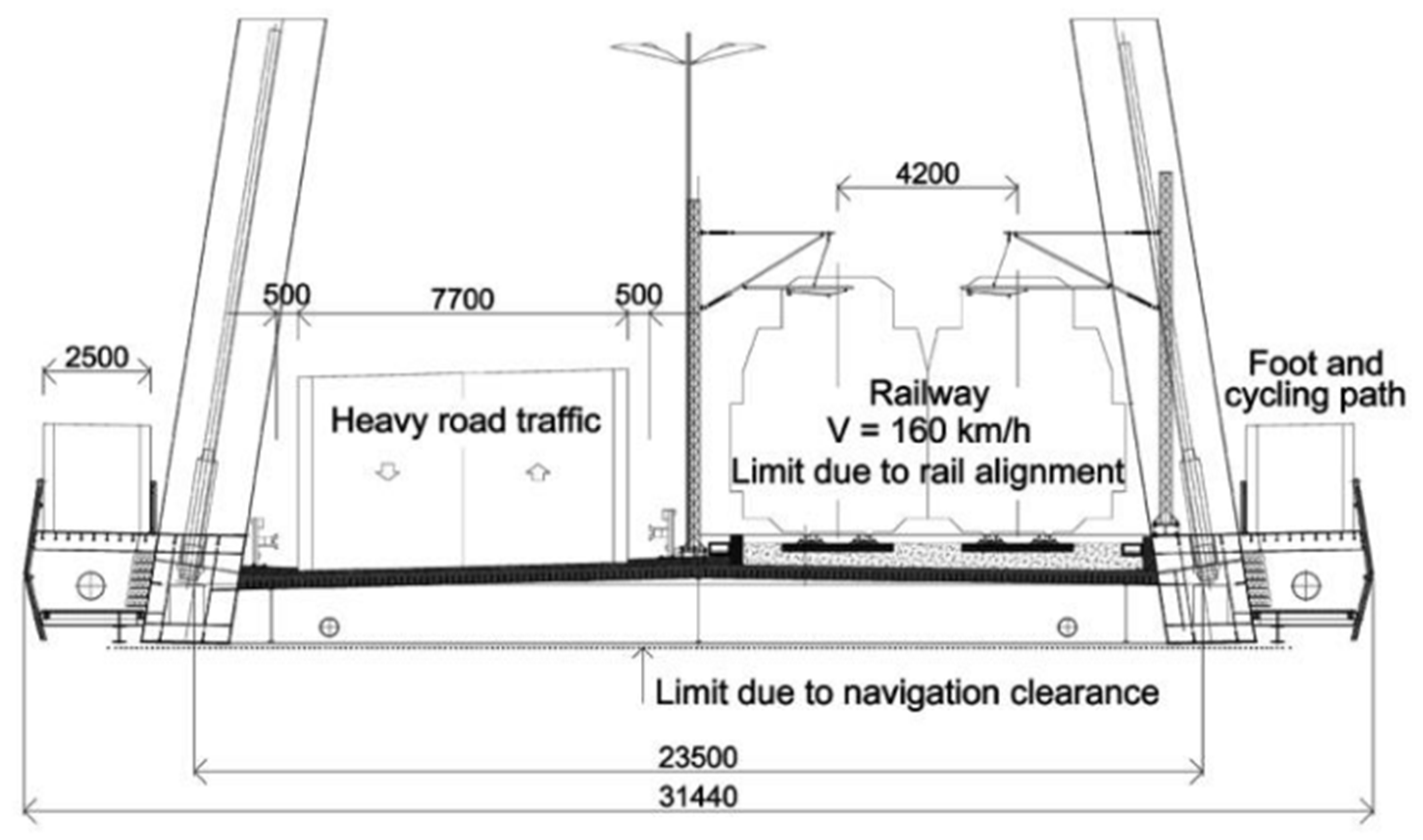

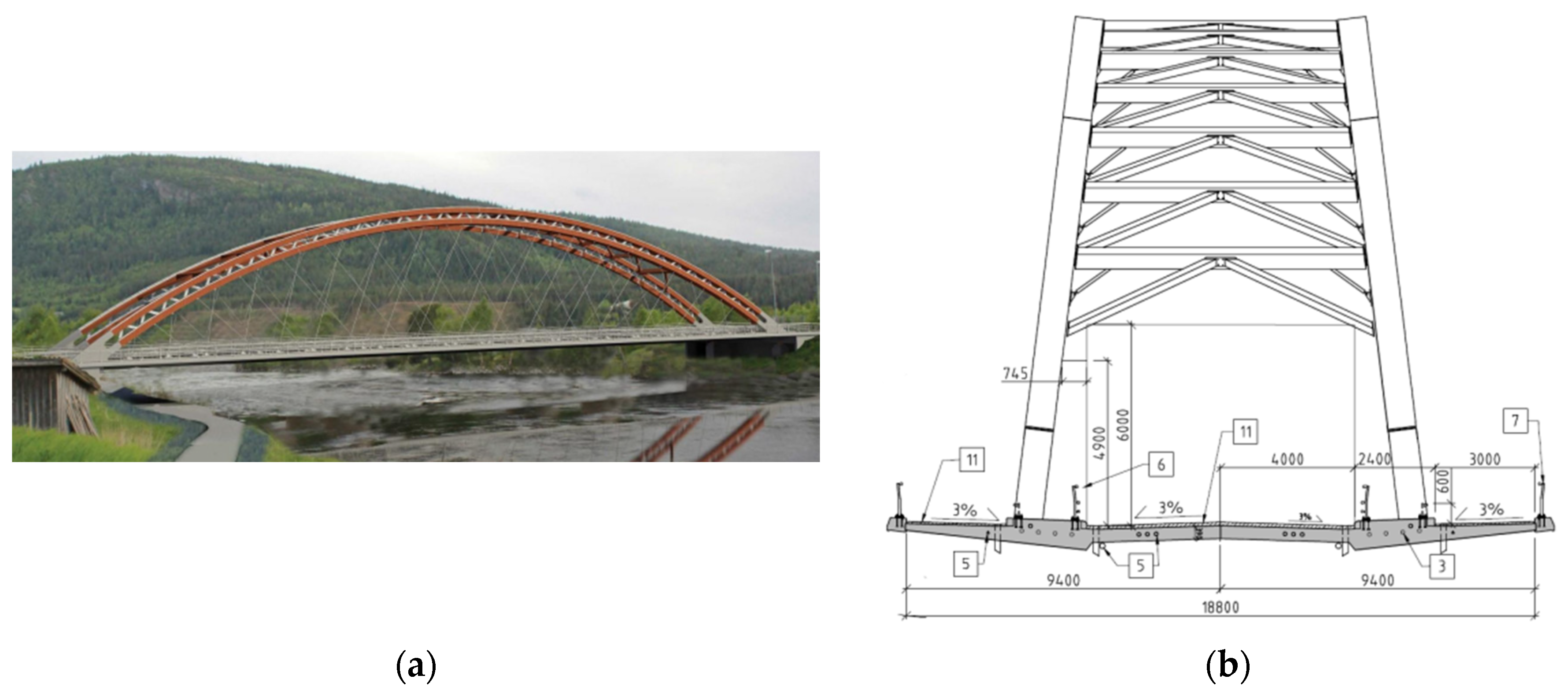

3.10. Steien Bridge

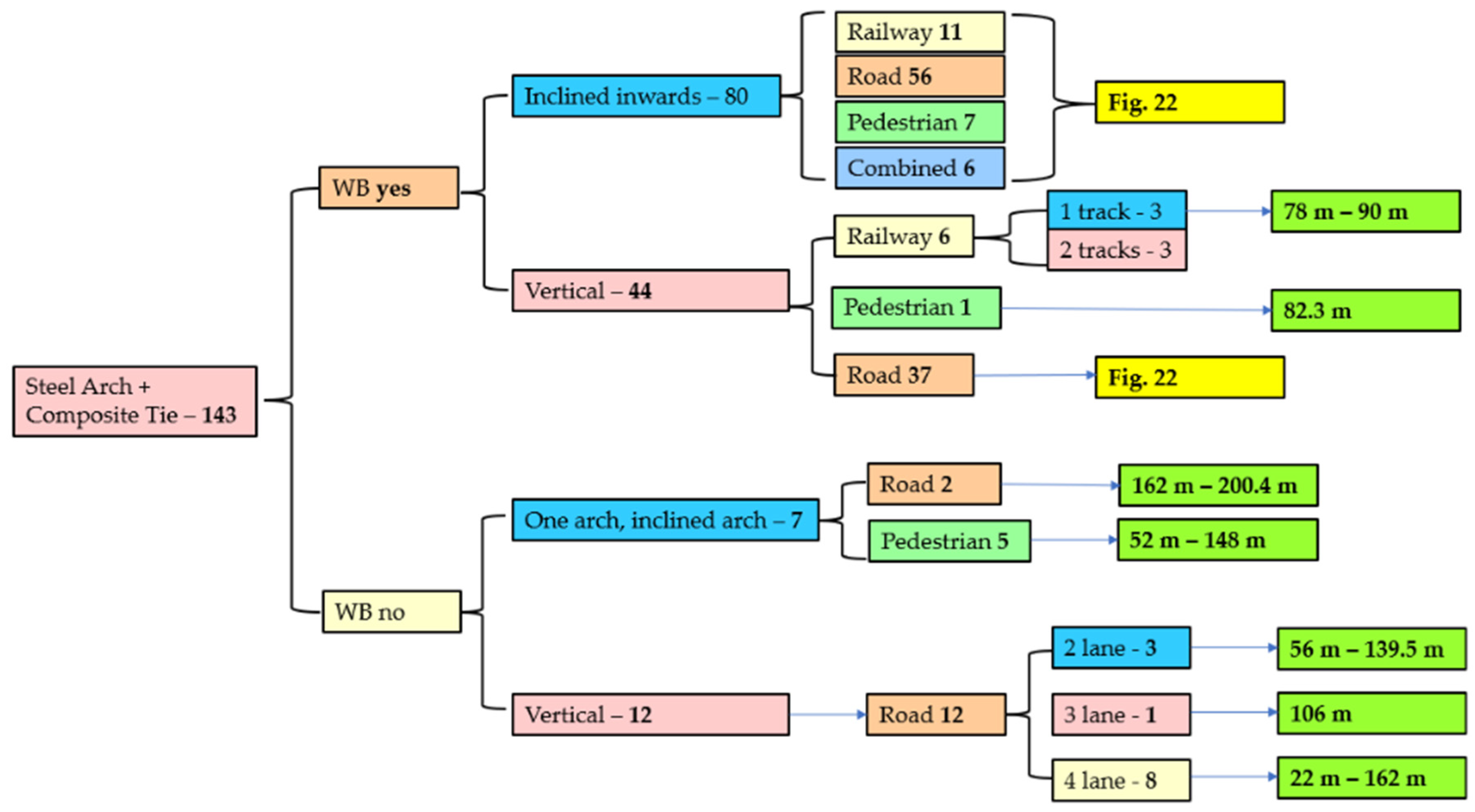

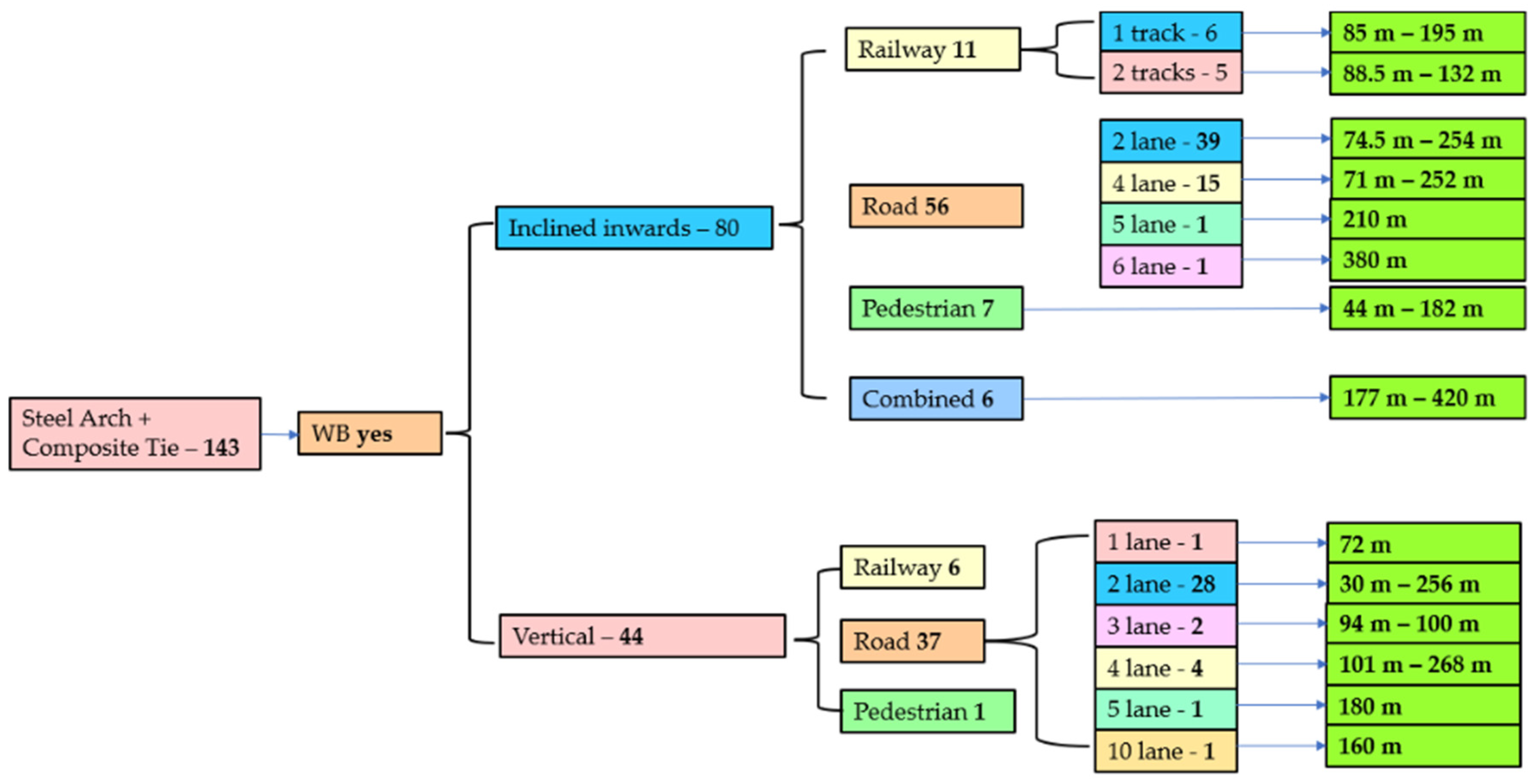

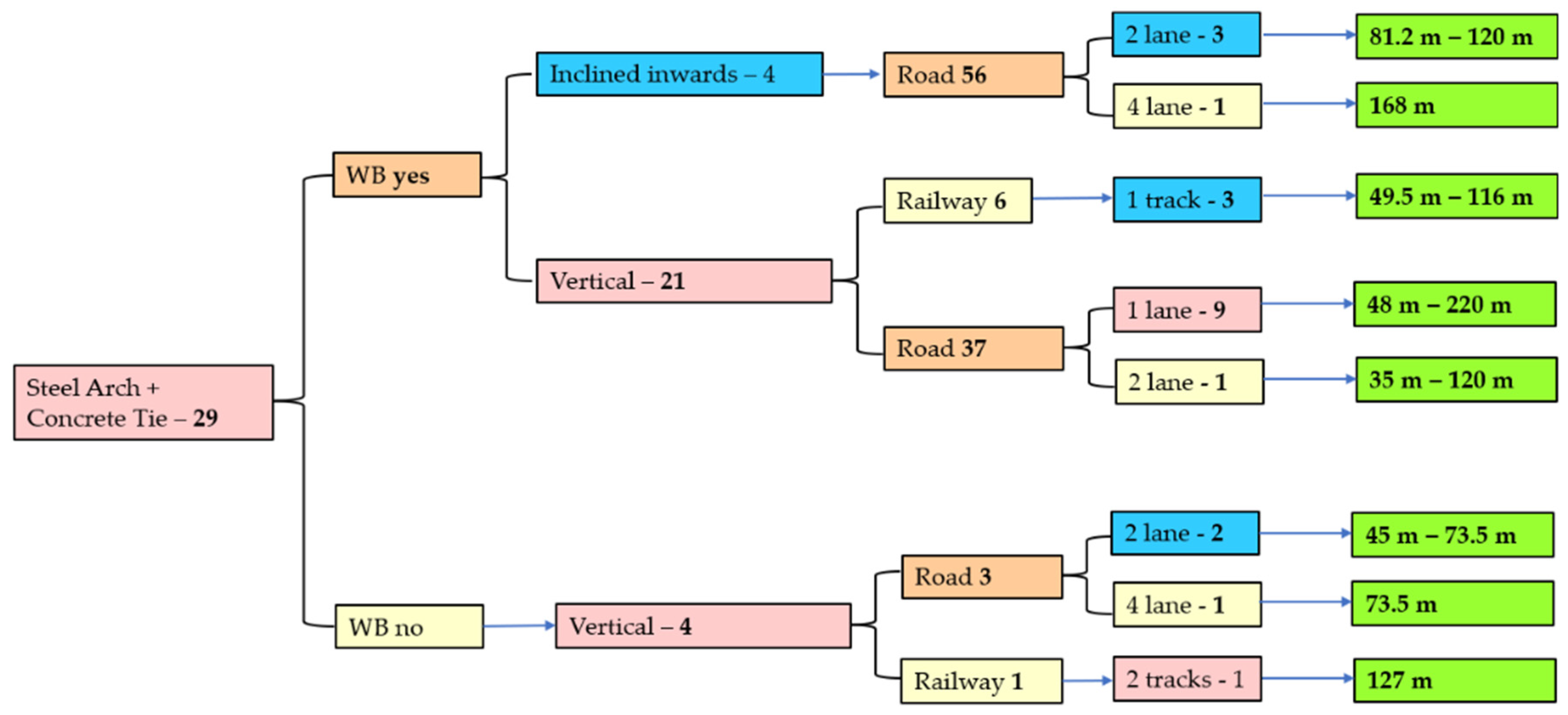

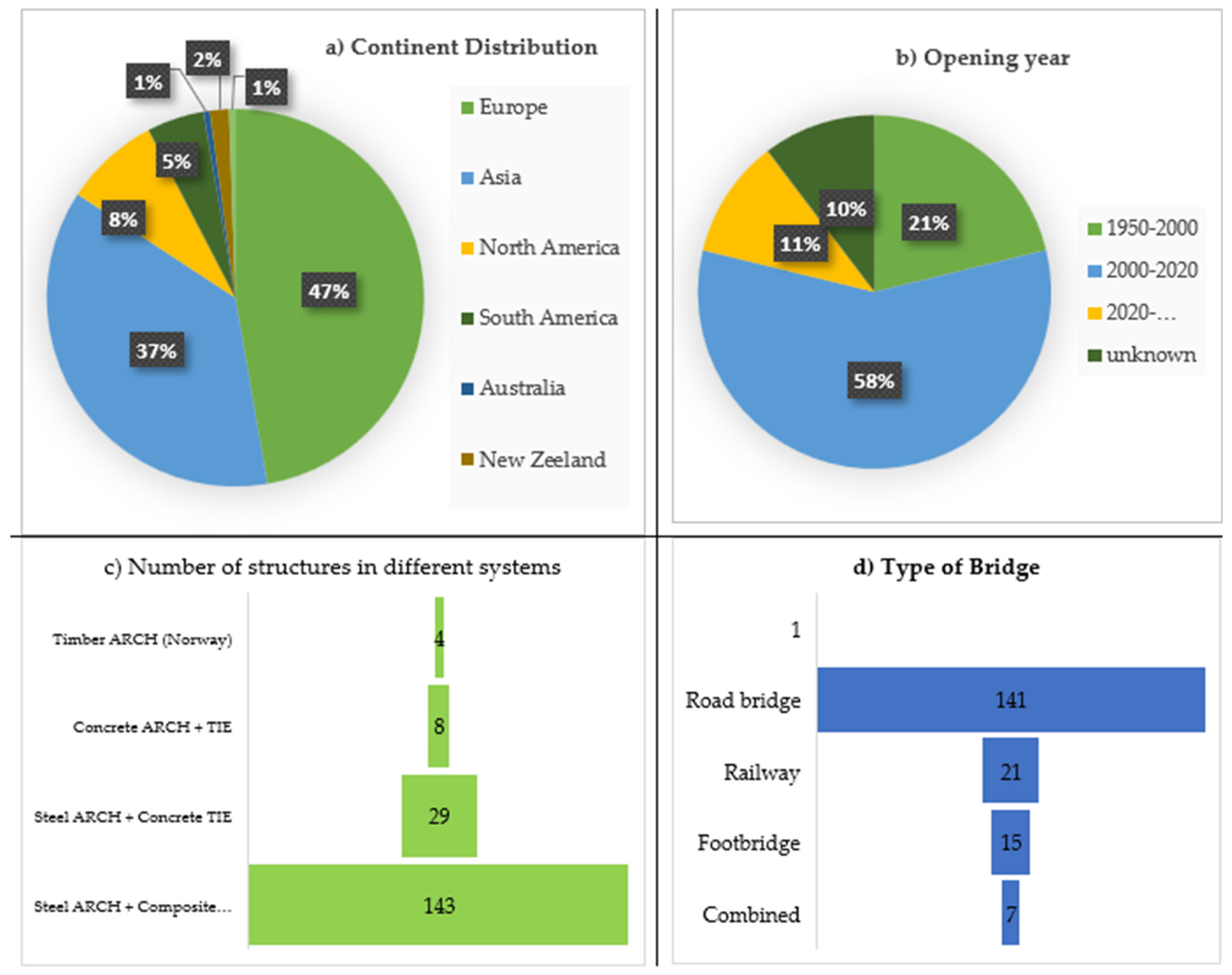

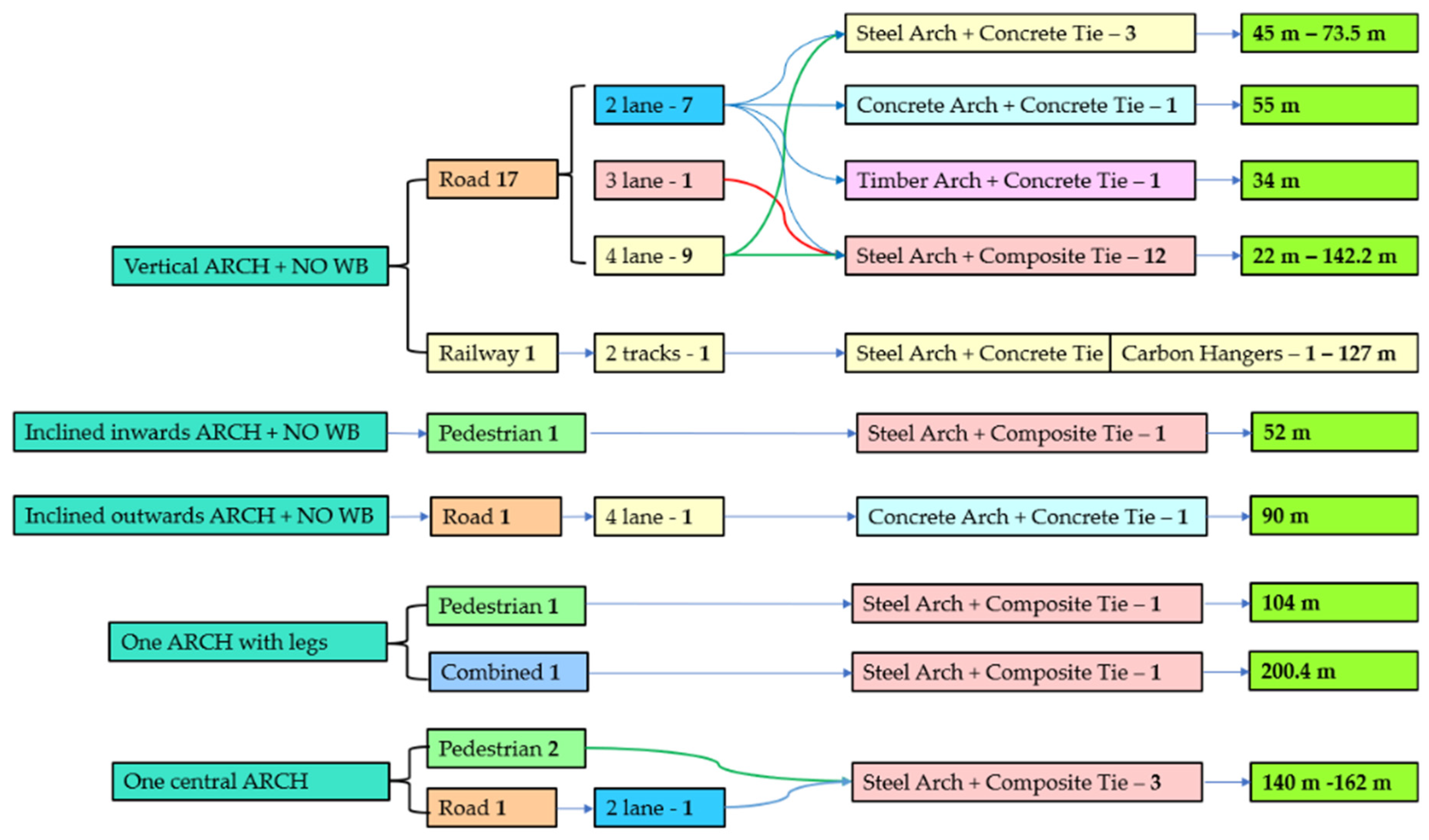

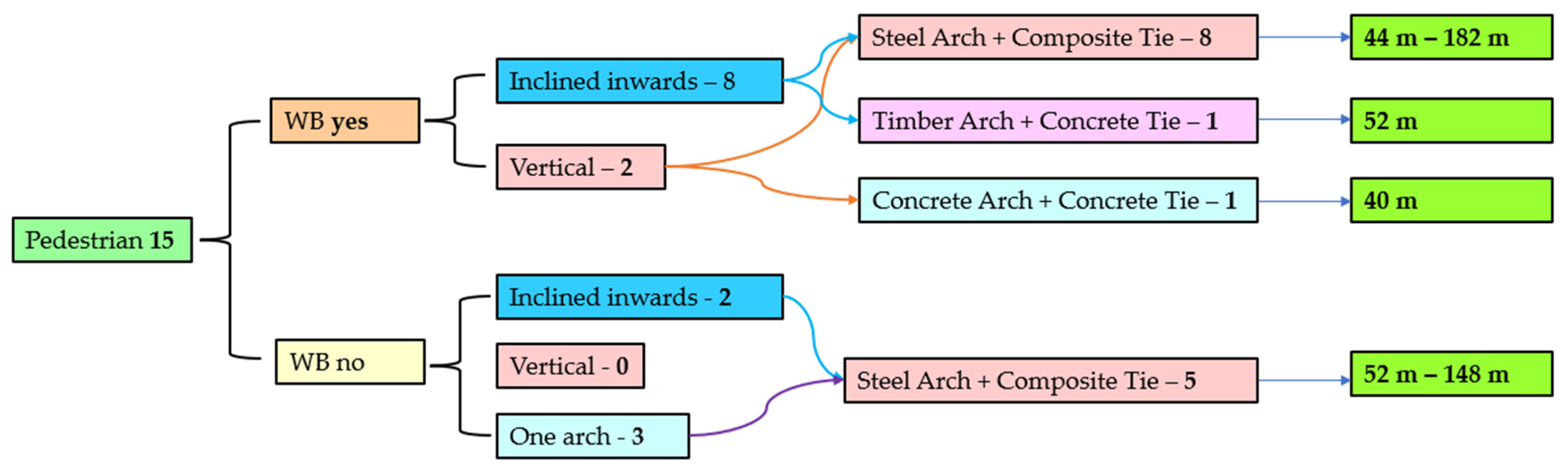

3.11. Network Arch Bridges in numbers

4. Research on Network Arch Bridges

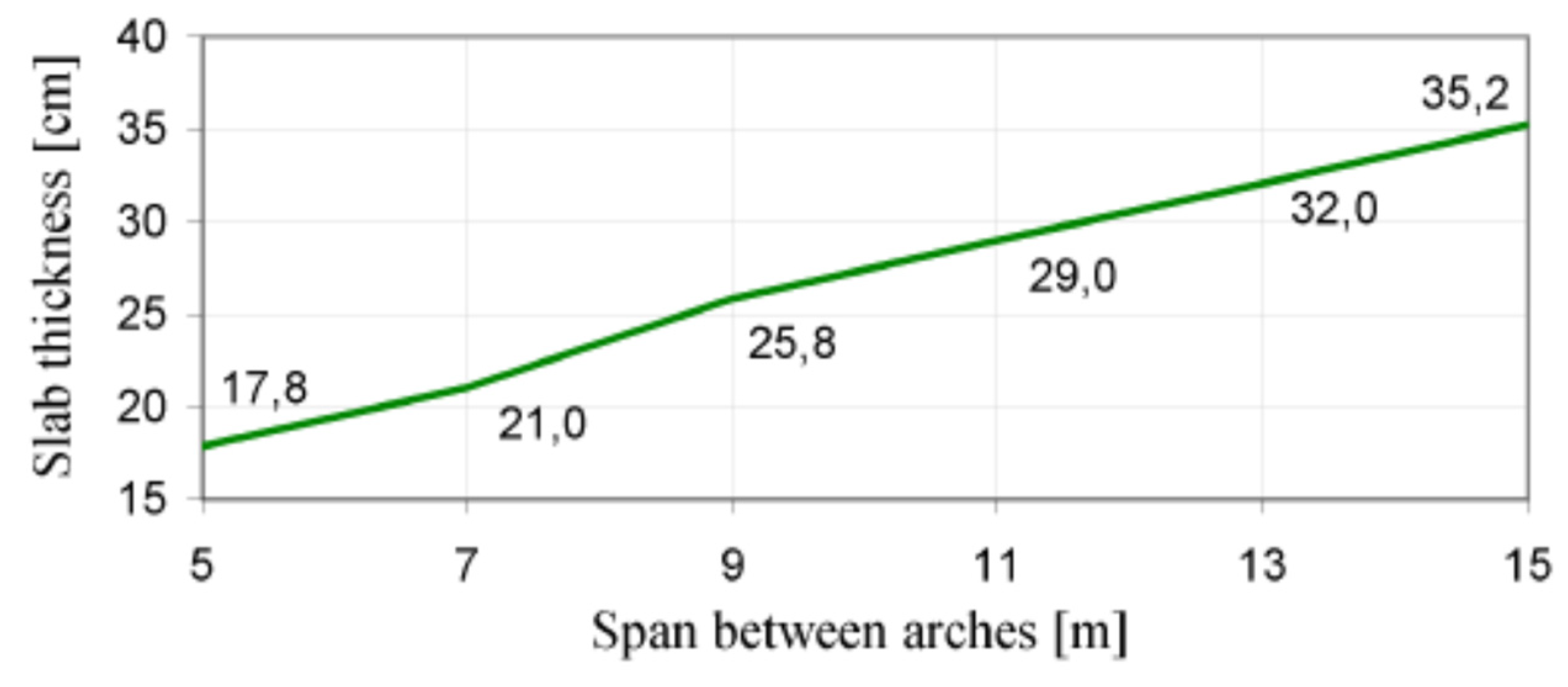

4.1. Network Arch Bridges in Timber

4.2. Netowrk Arch Footbridge

4.3. Stability analysis

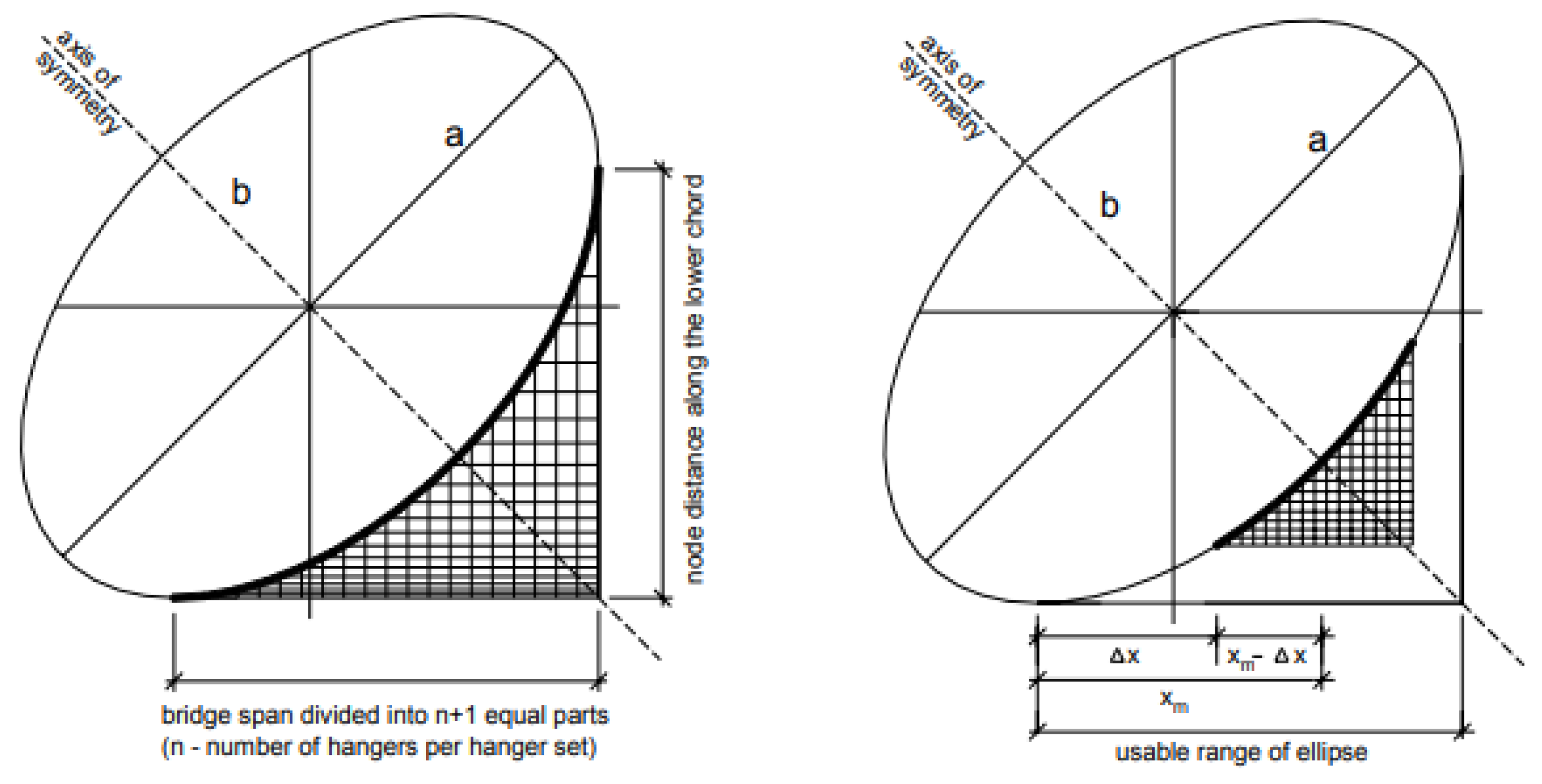

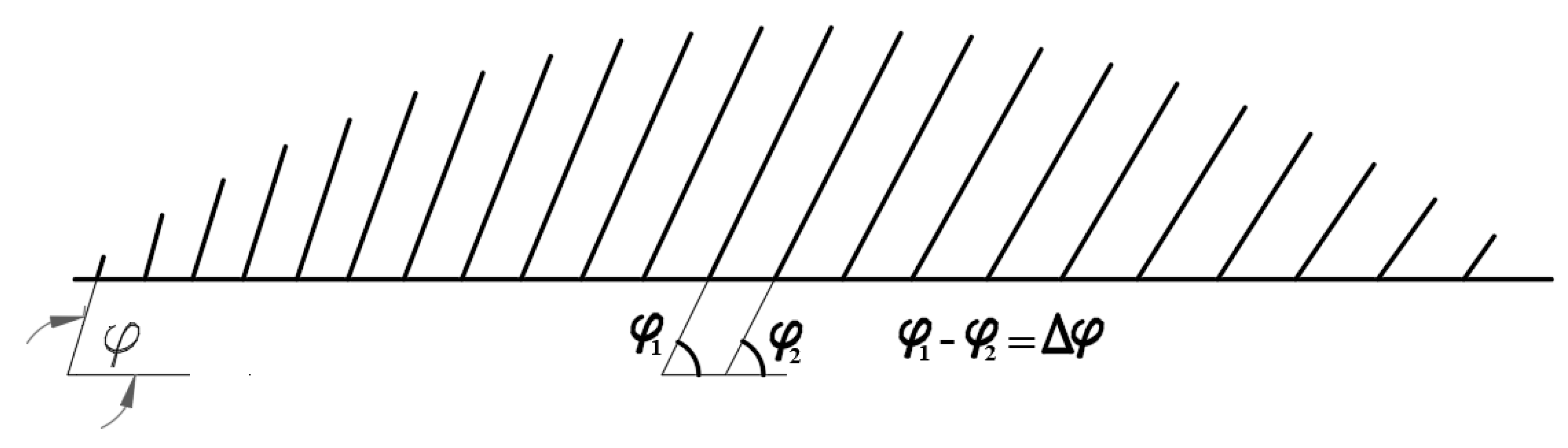

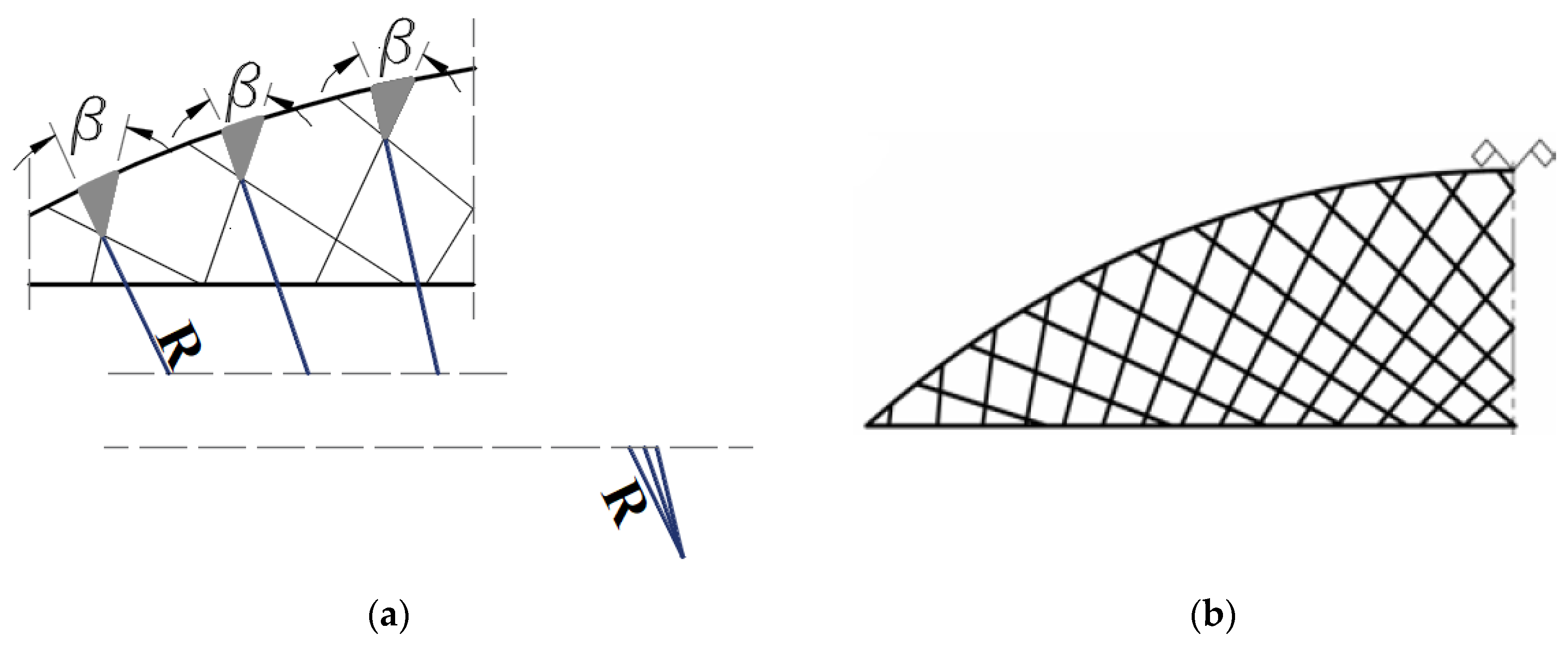

4.4. Hanger arrangement

4.5. Other research about the Network Arch Bridge

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tveit P., dr. ing. Docent Emeritus, Agder University, Grimstad, Norway. About the Network Arch. Personal communication, Second edition January 2011.

- Tveit P., dr. ing. Docent Emeritus, Agder University, Grimstad, Norway. The Network Arch. Bits of Manuscipt in March 2014 after Lectures in 50+ Countries. Personal communication, 2014.

- Map of Network Arch Bridges. Available online: URL (accessed on 24.08.2023).

- Nielsen, O.F. Foranderlige Systemer med anvendelse på buer med skraatstilledeHængestenger, (Discontinuous systems used on arches with inclined hangers). PhD Thesis, Gad Copenhagen, 1930, in Danish.

- Tveit P,. How to design economical network arches. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 471, 052078. [CrossRef]

- Larsse R.M., Jakobsen K.A., Brandangersundet Bru – verdens slankeste?, Nyheter om Stalbyggnad nr. 3, 2006, Innehall, pp. 37-40, in German.

- Teich S., Wendelin S., Vergleichsrechnung einer Netzwerkbogenbrückeunter Einsatz des Europäischen Normenkonzeptes., Diplomarbeit, Technische Universitat Dresden, 21 August 2001, in German.

- Steinmann U., Berechnung und Konstruktion einer stahlernen Eisenbahn-Stabbogenbrucke mit Netzwerkhangern, Diplmarbeit, Technische Universitat Dresden, in cooperation with Agder University College in Grimstad, Norway, September 2002, in German.

- Brunn B., Schanack F., Calculation of a double track railway network arch bridge applying the European standards. Master Thesis, Dresden University of Technology, Germany, defended in Grimstad, Norway, August 2003.

- Teich S., Beitrag zur Optimierung von Netzwerkbogenbrucken. Contribution to Optimizing Network Arch Bridges. PhD Thesis, Dresden, 2012, in German.

- Niklison A.J., Statical Analysis of Network Arch Bridges, Master Thesis, Stuttgart, 2010.

- Varennes M., Design of a single-track railway network arch bridge, Maser thesis, Stockholm, 2011.

- Rack M., Entwurf einer kombinierten Strassen-Eisenbahn-Netzwerkbogenbrucke, Diploma thesis, Dresden and Grimstad, 2003, in German.

- Da Costa B.N., Design and Analysis of a Network Arch Bridge, Tecnico Lisboa, Lisbon, Master Thesis, October 2013.

- Tveit P., Graduation thesis on arch bridges with inclined hangers, Technical University of Norway, Trondheim, September 1955.

- Tveit P., Arch bridges with inclined intersecting hangers. PhD. Thesis, Technical University of Norway, Trondheim, 1959, in Norwegian.

- Tveit P., Systematic Thesis on Network Arches 2014. Personal communication. Available online: URL http://home.uia.no/pert. Accessed at 21.07.2023.

- Yousefpour H., Helwig T.A., Bayrak O. Construction stresses in the world’s first precast concrete network arch bridge. PCI Journal, 2015, vol 60 (5), pp. 30-47. [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour H., Gallardo J.M., Helwig T.A., Bayrak O. Innovative precast, prestressed concrete network arches: Elastic response during construction. Structural concrete 2017, Vol 18, pp. 768-780. [CrossRef]

- Janata, V., Gregor, D., Sasek, L., Nehasil, P., Wangler, T., New Troja Bridge in Prague – Structural Solution of Steel Parts. Procedia Engineering 2012, Vol. 40, pp 159-164. [CrossRef]

- Tveit, P.; Construction of the Troja Bridge in Prague. Personal communication. Available online: https://home.uia.no/pert/data/Troja_bridge.pdf (accessed on 13th of June 2023).

- Gregor, D., Janata, v., Sasek, L., Nehasil, P., Broz, R. New Troja Bridge – Concept and Structural Analysis of Steel Parts, Procedia Engineering 2012, Vol. 40, pp 131-136. [CrossRef]

- Larssen R.M., Jakobsen S.E., Brandangersundet Bridge – A slender and light network arch, Taller, Longer, Lighter, IABSE-IASS-2011 London Symposium Report.

- Ronnquist, A., Naess, A. System reliability analysis of slender Network Arch Bridges. In Proceedings of the Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Kos Island, Greece, 12-14 June 2013.

- Ronnquist, A., Naess, A. Global Buckling Reliability Analysis of Slender Network Arch Bridges: An Application of Monte Carlo-Based Estimation by Optimized Fitting, In: Gardoni, P. (eds) Risk and Reliability Analysis: Theory and Applications. Springer Series in Reliability Engineering, 2017, Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Millanes, F M., Ortega, M., Carnerero, A. Palma del Rio Arch Bridge, Cordoba, Spain. Technical Report in Structural Engineering International, 2010, Vol. 3, pp. 338-342. [CrossRef]

- Millanes, F., Ortega, M., Carnerero, Project of two metal arch bridges with tubular elements and network suspension system, steel bridges: Advanced solutions & technologies. In 7th International Conference on Steel Bridges Proceedings, Guimaraes, Portugal, 4-6 June 2008.

- Mato, F. M., Cornejo, M. O., Agromayor, D. M., Perez, P. S. The use and development of the Network Suspension System for Steel Bowstring Arches, Proceedings of the IVth Congresso de Construçao Metálica e Mista (cmm-associaçao Portuguesa de Construçao Metálica e Mista), Lisbon, Portugal, 2008, II-97/106.

- Mato, F. M., Cornejo, M. O., Sanchez, J. N. Design and Construction of Composite Tubular Arches with Network Suspension System: Recent Undertakings and Trends. Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 2011, Vol 5 (30), pp. 191-214. [CrossRef]

- World’s first Network Arch Bridge with CFRP hangers. https://www.compositesworld.com/news/german-railway-bridge-suspended-on-cfrp-hangers. Accessed online at 27.07.2023.

- Haspel, L. Bauen mit Zuggliedern aus Carbon in Proceedings 14. 14. Fachtagung Baustatik – Baupraxis, Stuttgart, 8-9.05.2021.

- Haspel, L. Netzwerkbogenbrücken mit Hängern aus Carbon. Stahlbau, 2019, Vol. 8, Heft 2, S 153-159. [CrossRef]

- Keil, A., Haspel, L. Stadtbahnbrucke - built innovation: an integral supported network arch with CFRP hangers. Bautechnik, 2021, Vol. 98, H. 2, S. 149–158. [CrossRef]

- Haspel, L. Carbon network arch - lessons from the first use of carbon network cables. Stahlbau, 2022, Vol. 91 ,H. 2, S. 84–94. [CrossRef]

- Meier, U.O., Winistorfer, A. U., Haspel, a. World’s first large bridge fully relying on carbon fiber reinforced polymer hangers. SAMPE Conference, The Future Composite Footprint, Amsterdam, 30.09-01.10.2020.

- German Civil Engineer Award, 2022. URL:https://www.sbp.de/en/news/stadtbahnbruecke-in-stuttgart-erhaelt-deutschen-ingenieurbaupreis-2022. Accessed online at 27.07.2023.

- Bojovic, A., Mora Munoz, A., Markovic, Z., Aleksic, D., Pavlovic, M., Spremic, A. Railway Road Bridge in Novi Sad – Design and Erection. 37th IABSE Symposium Madrid, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Bojovic, A., Mora, Markovic, Z., Pavlovic, M., Novakovic, N., Spremic, M. Railway Road Bridge in Novi Sad. Steel Tied network arches across the Danube. IOP Conference Series: Material Science and Engineering, 2018, 419 (11), 0120032. [CrossRef]

- SHM system of the Zezelj (Novi Sad) Bridge. URL: https://www.hbkworld.com/en/knowledge/resource-center/case-studies/2023/bridge-monitoring-an-example-from-hbm#!ref_www.hbm.com. Accessed online at 28.07.2023.

- Veie, J., Bjertnaes, M., Stensby, T. A. New dimensions in bridge construction in Norway. Internationales Holzbau-Forum IHF, 2015.

- Veie, J., Abrahamsen, R. B. Steien Network Arch. International Conference on Timber Bridges, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2013.

- Zhou, W., Senior Eng., Chen, L., Professional Senior Eng., Shao, C., Chief Eng., Wu, X., Senior Eng. A Long-span Network Arch Birdge for Road and Rail Traffic, Structural Engineering International, 2022, 32 (2), 211-215. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y., Li, Y., Huang, M., Zhao, L., Chen, J., Min Xie, Y. Conceptual design of long span steel-UHPC composite network arch bridge. Engineering Structures, 2023, Elsevier, Vol. 277, 115-434. [CrossRef]

- Steere, P., Wu, Y. Design and construction of the Providence River Bridge. 25th Annual International Bridge Conference Engineers’ Society of Western Pennsylvania Pittsburgh, 2.06 – 4.06, 2008.

- Bell, K., Wollebaek, L. Large, mechanically joined glulam arches. The 8th World Conference on Timber Engineering WCTE 2004, Lahti, Finland, 14.06-17.06.2004.

- Wollebaek, L., Bell, K. Stability of glulam arches. The 8th World Conference on Timber Engineering WCTE 2004, Lahti, Finland, 14.06-17.06.2004.

- Nylander, E. A feasibility study of a network arch bridge with glulam arches. Master Thesis, Rapport TVBK-5211, ISSN 0349-4969, Lund University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malo, K.S., Ostrycharczyk, A., Barli, R., Hakvag, I. On development of network arch bridges in timber. International Conference on Timber Bridges, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2013.

- Ostrycharczyk, A.V. Network arch timber bridges with light timber deck on transverse crossbeams. PhD thesis. Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, November 2017.

- Ostrycharczyk, A.V., Malo, K.A. Comparison of network patterns suitable for timber bridges with crossbeams. Proceedings of ICTB, 3rd International Conference on Timber Bridges, Skelleftea, Sweden, 26.06-29.06.2017.

- Ostrycharczyk, A.V., Malo, K.A. Parametric study of radial hanger patterns for network arch timber bridges with a light deck on transverse crossbeams. Engineering Structures, 2017, 153, 491-502. [CrossRef]

- Ostrycharczyk, A.V., Malo, K.A. Parametric study on effects of load position on the stress distribution in network arch timber bridges with light timber decks on transverse crossbeams. Engineering Structures, 2018, 163, 112-121. [CrossRef]

- Ostrycharczyk, A.V., Malo, K.A. Network arch timber bridges with light timber decks and spoked configuration of hangers – parametric study. Engineering Structures, 2022, 253, 113-782. [CrossRef]

- Ostrycharczyk, A.V., Vaernes, A. Vala bridge – Timber network arch footbridge in Ringebu, Norway. Conference Proceedings. 4th International Conference on Timber Bridges ICTB 2021 Plus, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland, 9-12.05.2021.

- O’Born, R., Vertes, K., Pytten, G., Hortemo, L.O., Braendhagen, A. Life cycle assessment of an optimized network arch highway bridge utilizing timber. 10th Conference on the Bearing Capacity of Roads, Railways and Airfields, Athens, Greece, June 2017.

- Garcia, A.G. A parametric study of the static and dynamic performance of timber arch footbridges with different hanger configurations. Master thesis. KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2022.

- Mato, F.M., Rubio, L.M., Sanchez, J.N. Bowstring footbridges in the cycling ring road in Madrid. Presented at 3rd International Conference on Footbridges. Footbridge 2008 – Footbridges for Urban Renewal. Porto, Portugal, 133-134, 2-4.07.2008.

- Belevicius, R., Juozapaitis, A., Rusakevicius, D. Parameter Study on Weight Minimization of Network Arch Bridges. Periodica Polytechnica Civil Engineering, 2018, 62(1), pp.48-55. [CrossRef]

- Belevicius, R., Juozapaitis, A., Rusakevicius, D., Zilenaite, S. Parametric study on mass minimization of radial network arch pedestrian bridges. Engineering Structures, 2021, 237, 112-182. [CrossRef]

- Belevicius, R., Juozapaitis, A., Rusakevicius, D., Zilenaite, S. Optimal schemes of radial network arch pedestrian bridge: An extensive dataset of solutions under different conditions. Data in Brief, 2021, 36, 107-149. [CrossRef]

- Belevicius, R., Rusakevicius, D., Valentinavicius, S. Insights into Optimal Schemes of Radial Network Arch Pedestrian Bridge. Advances in Civil engineering, 2022, Hindawi, Aritcle ID 6951775, 12 pg. [CrossRef]

- Tan, YG., Yao, YB. Optimisation of hanger arrangement in pedestrian tied arch bridge with sparse hanger system. Advances in Structural Engineering, Vol 22 (12), 2594-2604, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schanack, F. Calculation of the critical in-plane buckling load of network arches. Bautechnik, 2009, 86 (5), pp 249-255. [CrossRef]

- Lonetti, P., Pascuzzo, A. A practical method for the Elastic Buckling Design of Network Arch Bridges. International Journal of Steel Structures, 2020, 20 (1), 311-329. [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, P., Tetougueni, C. D., Maiorana, E., Pellegrino, C. Post-buckling of network arch bridges subjected to vertical loads. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 2021, Vol 17 (7), 941-959, Taylor&Francis. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D., Lonetti, P., Pascuzzo, A. A numerical study on network arch bridges subjected to cable loss. International Journal of Bridge Engineering, 2018, 6 (2), pp. 41-59.

- Ammendolea D., Bruno, D., Greco, F., Lonetti, P., Pascuzzo, A. An investigation on the structural integrity of network arch bridges subjected to cable loss under the action of moving loads. Procedia Structural Integrity, 2020, 25, pp. 305-315. [CrossRef]

- Blonka, A., Skretkowicz, L. Nonlinear buckling analysis of network arch bridges. Studia Geotechnica et Mechanica, 2022, 44 (2), 123 – 137. [CrossRef]

- Schanack, F., Brunn, B. Generation of network arch hanger arrangement. Stahlbau, 2009, Vol. 78 (7), pp. 443-522. [CrossRef]

- An, L.h., Duy, D.M. Research on the hanger arrangement for the concrete filled steel tubular arch bridge with rod and roadway located under arch rib. Sustainable arch bridges, 3rd Chinese-Croatian Joint colloquium on Sustainable Arch Bridges, Zagreb, Croatia, 15-16.07.2011.

- Danciu, A.D., Gutiu, S.I., Moga, C. Bi-dimensional analysis of a 90 m arch with different hanger arrangements. In Nano, Bio and Green – Technologies for a sustainable future conference Proceedings, SGEM 2016, Vol. 2, pp. 477-484, Bulgaria, 2016.

- Vlad, M., Kollo, G., Marusceac, V. A modern approach to tied-arch bridge analysis and design. Acta tehnica Corviensis – Bulletin of Engineering, 2015, Tome VIII (4), pp. 33-37.

- Vlad, M. Study on concept and design of cable structures. PhD Thesis, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Cluj, Romania, 2019. In Romanian. [Google Scholar]

- Danciu, A.D., Gutiu, S.I., Moga, C, Bucerzan, M. Comparative Analysis between the Hanger Arrangement in an 80 m Network Arch Bridge with Circular Hollow cross-sections. In Lecture Notes in Networks and systems, 2022, Vol. 386, pp. 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Bayyavarapu, R., Talukdar, S., Lalthlamuana, R. Effect of rise to span ratio on the Behavior of a Steel Arch Bridge for different types of Hanger Arrangement. Steel and Aluminium Structures, 8th International Conference on Steel and Aluminium Structures (ICSAS), Hong Kong, 7-9.12.2016.

- Bruno, D., Lonetti, P., Pascuzzo, A. An optimization model for the design of network arch bridges. Computer and Structures, 2016, vol 170, pp 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N., Rana, S., Ahsan, R., Ghani, S. N. An Optimized Design of Network Arch Bridge Using Global Optimization Algorithm. Advances in Structural Engineering, 2016, Vol 17(2), pp. 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, B., Schanack, F., Marx, S. Asymmetric network arch bridges. Stahlbau, 2009, Vol 78(7), pp. 471-476. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.A., Casas, J.R. Bridge strengthening by conversion to network arch: design criteria and economic validation. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 2016, Vol 12 (10), pp. 1310-1322. [CrossRef]

- Gautier, P., Krontal, L. Experiences with Network arches for railway bridges. Stahlbau, 2010, Vol 79(3), pp. 199-208. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt-Herberger, K., Reinke, K.D. Reconstruction of the motorway bridge over the Havelkanal near Breselang, Germany. Stahlbau, 2012, Vol. 81 (2), pp. 91-U4. [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, D., Ochojski, W., Lorenc, W., Kozuch, M. Advanced solutions with hot-rolled sections for economical and durable bridges. Steel construction – design and research, Vol. 11 (3), pp. 196-204, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, T., Galewski, T., Topolewicz, K., Sek, R., Radziecki, A, Ochojski, W., Kozuch, M., Lorenc, W. Polish experience with network arch bridges using cold-bent HD sections. Steel construction – design and research, 2020, Vol. 13 (4), pp. 271-279. [CrossRef]

- Zanon, R., Matos, R., Rademacher, D., Lorenc, W. Network arch bridges with rolled sections: ideas for economic and durable detailing. 12th Conference on Steel and Composite Construction, Coimbra, Portugal, Ernst&Sons, pp. 106-116, 21-22.11.2019. [CrossRef]

- Heinlein, M., Einhauser, O. Network arch bridges for the OBB over the central marshalling yard at Vienna-Kledering, Austria – Structural and constructional design of the bridges. Stahlbau, 2013, Vol 82(5), pp. 334-339, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, B., Dorrer, G. Two network arch bridges: Connection between the existing railway lines Ostbahn and Flughafenschnellbahn in Vienna, Autrisa – Characteristics form the point of view of steel constructors. Stahlbau, Vol. 82(5), pp. 326-333. [CrossRef]

- Rusev, R., Foster, R., Abbott, T., Bistolas, A. River Irwell Crossing – UK’s First Network Arch Bridge. Structural Engineering International, 2019, Vol 29(2), pp. 309-314. [CrossRef]

- Brook, T., Gaby, P. Perry Bridge Network Arch – Elegance in Efficiency. Structural Engineering International, 2020, Vol 30(2), pp. 250-253. [CrossRef]

- Information on the Network Arch. Available online: https://home.uia.no/pert/index.php/Home (accessed on 25.08.2023).

| Bridge Name | Location | Opening | Type | Span [m] | Arch | Tie | Lateral buckling |

| Steien Bridge | Alvdal, Norway | 2016 | Road | 88.2 | Glulam, truss box | concrete | Arch Inclined inwards, WB |

| Våla Bridge | Ringube, Norway | 2020 | Pedestrian | 52 | Glulam, box | Concrete | Arch Inclined inwards, WB |

| Hellefossbrua | Etnedal, Norway | 2019 | Road | 70 | Glulam, box | Concrete | Arch Inclined inwards, WB |

| Prestmyra bru | Elverum, Norway | 2018 | Road | 34 | Glulam, box | Concrete | WB |

| Bridge Name | Location | Opening | Type | Traffic | Span [m] | Arch+Tie | Arches+WB |

| Steflinger River Bridge | Steflinger, Germany | 2015 | Road | 2 lane | 55 | Concrete | Vertical, no WB |

| Nervión Bridge | Bilbao, Spain | 2017 | Railway | 2 tracks | 80 | Concrete | Inclined inwards, WB |

| Bijuli Bazar Bridge | Kathmandu, Nepal | 2019 | Road | 2 lane | 52 | Concrete | Vertical, WB |

| Bijuli Bazar Bridge | Kathmandu, Nepal | 2019 | Road | 2 lane | 52 | Concrete | Vertical, WB |

| Rayar Bazar Bridge | Dacca, Bangladesh | 2015 | Pedestrian | Pedestrian | 40 | Concrete | Vertical, WB |

| Tsukani Bridge | Mitsuqi Dam, Japan | NA | Road | 2 lane | 151 | Concrete | Vertical, WB |

| W 7th Street Bridge | Dallas, USA | 2013 | Road | 2 lane | 6x50 | Concrete | Vertical, WB |

| Bent Bridge | San Josa, USA | 2011 | Pedestrian | Pedestrian | 82.3 | Concrete | Vertical, WB |

| Sixth Street Viaduct | Los Angeles, USA | 2022 | Road | 4 lane | 10x90 | Concrete | Inclined outwards, no WB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).