1. Introduction

A combined sewer system is a sewage infrastructure that collects and conveys both domestic sewage and stormwater runoff in a single-pipe system. This practice was common in older towns and urban areas before developing separate sewage systems. In a combined sewer system, the same pipe carries all residential, commercial, and industrial sewage as well as rainwater from streets, roofs, and other impermeable surfaces during rain. Combined Sewer Systems (CSS) were designed over 150 years ago to convey wastewater and stormwater directly into waterways. Due to blockages or high stormwater flow, wastewater is frequently still directed to the original body of water. It is called a combined sewer overflow or CSO. The operation of CSOs sometimes prevents houses and businesses from flooding [

1].

In 2023, about 700 municipalities in the US have CSOs [

2,

3]. 9,348 CSO outfalls are identified and regulated by National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits [

3]. Combined sewer systems are found in 32 states (including the District of Columbia) and nine EPA Regions. CSO communities are regionally concentrated in older communities in the Northeast and Great Lakes regions.

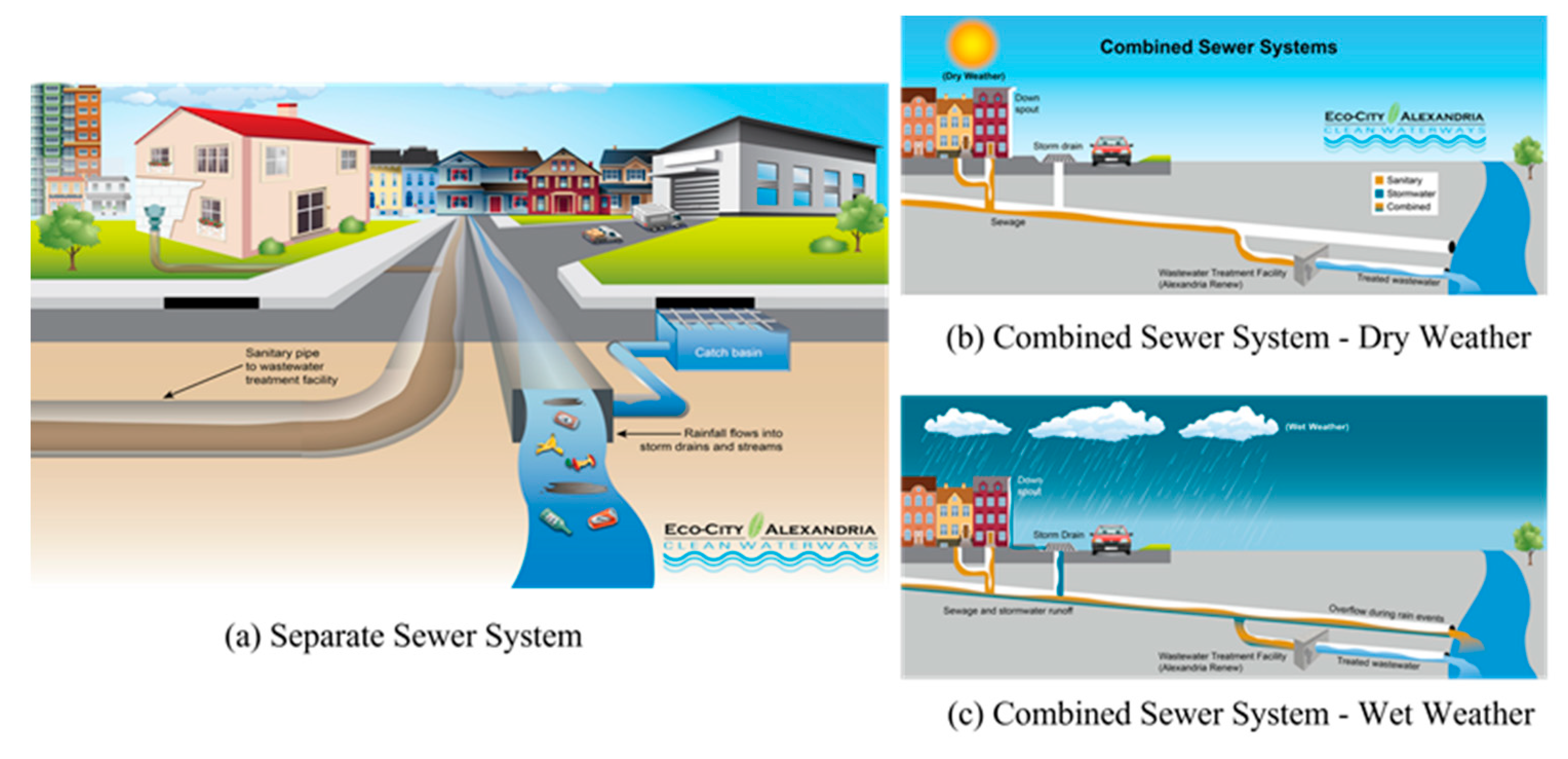

Figure 1 shows a typical CSS compared to a separate sewer system (SSS). Separate sewer systems have two separate pipes. One pipe carries stormwater (rainwater) from storm drains to local streams. Pollution and trash in stormwater flow to local waterbodies with little or no treatment. A second pipe carries sanitary sewage to the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). When it rains in a combined sewer system, stormwater flows into the same pipe and mixes with raw sewage. In dry weather, all sewage flows to the WWTP. The combined volume of stormwater is significant, particularly during periods of heavy rainfall. For instance, in Alexandar City, Virginia, USA, there can be nine times more stormwater than raw sewage when it rains [

4]. Subsequently, the stormwater can overwhelm the CSS. When this happens, the mixture may overflow into local streams through one of the four permitted combined sewer outfalls in Alexander. Permitted outfalls are located throughout the system to act as relief points during wet weather. These outfalls discharge untreated or partially treated stormwater and wastewater into nearby waterbodies. The volume of stormwater and wastewater entering the system can exceed its capacity to treat and manage the water. To prevent backups and flooding, these permitted outfalls provide a controlled release mechanism. EPA estimates that over 850 billion gallons of untreated wastewater and stormwater are released as CSO each year from over 750 cities in the US [

3].

Similar to the US, many countries’ existing sewer networks are not designed to handle the collective stormwater and wastewater separately during stormy periods [

1]. Because of this capacity limit, overflows frequently occur. CSOs have hazardous consequences to surface waters, both health-related and economic risks, if they are not adequately controlled [

5,

6,

7,

8]. According to the EPA report to Congress in 2004, CSOs and sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs) cause high levels of E. Coli bacteria, leading to harmful algal blooms and between 3500 – 5500 gastrointestinal illnesses yearly [

3]. It can also have high economic impacts when recreational areas have to be shut down or avoided.

Due to the extreme costs of preventing these overflows, many cities did not confront these problems until the late 20th century. In 1994, brought on by violations of the Clean Water Act, the EPA issued the CSO Control Policy. Through the use of the NPDES permitting program, cities were mandated to immediately reduce and plan to eliminate CSOs or face significant fines. As a result, cities had to present Long-term Control Plans (LTCP) to prevent CSOs.

Moreover, ongoing climate variability and climate changes may cause intensified precipitation events in some areas, which may also lead to frequent CSOs [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Minimizing CSOs in urban areas is an essential task for many municipal councils [

8]. Many methods to control CSOs as part of their LTCP fulfill a commitment to the EPA to lessen the amount of wastewater that ends up in rivers and streams. The manageable methods accepted by the EPA are separation, green infrastructure, and gray infrastructure. These approaches can be classified into structural and non-structural measures. The structural measures in controlling CSOs, such as underground tunnels to store combined sewer flows on stormy days, are physical construction. Otherwise, Non-structural measures utilize knowledge and experiences to develop various policies and control approaches to reduce the CSOs in existing sewer networks [

8]. The financial capabilities and disturbances to the habitants have limited the structural measures in minimizing the CSOs [

8,

12]. Therefore, non-structural measures, such as real-time monitoring, modeling, data processing and analytics, and artificial intelligence/machine learning, providing dynamic feedback and optimization, are a higher priority today [

8,

13]. For instance, new research and declining costs in wireless sensor technology have allowed for an alternative solution using wireless flow and level sensors to monitor and manipulate stormwater flow. It is reported that real-time control plays a significant role in sewer network control [

8].

2. Objective and Scope of Study

This study investigates the benefits and shortcomings of conventional methods (i.e., separation, green infrastructure, and gray infrastructure) and wireless sensor technology as real-time control by using information gained from EPA reports and local public works sources. Much of this data, including annual overflow and system effectiveness, was obtained by the cities’ use of EPA’s Storm Water Management Modeling (SWMM) software. We selected two cities: Richmond, Virginia and South Bend, Indiana, to investigate CSO problems. Two cities have had similar problems, including average rainfall, overflows, and treatment plant capacity. South Bend is taking a more modern approach, using inexpensive wireless sensor technology to enhance modeling efforts, increase capacity in the existing structures, and better prepare for storm events. Whereas Richmond is focused on traditional methods using primarily gray and green infrastructure improvements, along with monitoring and modeling. After learning from the investigation of two cities, this study aims to use available SWMM data to suggest the best path to effective management for CSO issues in Richmond, VA.

3. Conventional Methods

The primary objective of the city’s CSO prevention strategy in the conventional CSS revolves around efficiently redirecting a substantial portion of both stormwater and wastewater to the WWTP during the peak periods of wastewater daily usage and annual stormwater cycles. To understand these complex systems, cities rely on standardized modeling tools such as the SWMM to gain insight into stormwater and wastewater inflows. These sophisticated models allow municipalities to assess handling capacity and predict potential flooding. SWMM leverages geographic and sewage system data to effectively measure and predict the impact of storm events on the entire system. SWMM data suggests that the solution to preventing CSOs is creating or allowing for more capacity within the system or lowering the flow of stormwater that enters the system. SWMM data has also allowed the research of the following three major categories for controlling CSOs: total separation of the wastewater system, green infrastructure, and gray infrastructure.

The first approach is to increase the system’s capacity by creating new infrastructure or allowing for expansion. This approach aims to reduce the potential for flooding during peak periods by accommodating larger volumes of water. A second way to control CSOs is through the implementation of green infrastructure. It entails integrating green elements such as permeable surfaces, rain gardens, and green roofs. These practices promote natural rainwater absorption, minimizing strain on the sewer system and reducing overflow. The third category entails building gray infrastructure consisting of conventional engineered solutions such as storage tanks, tunnels, and cisterns. These structures effectively manage stormwater and wastewater, mitigating the risk of combined sewer overflow. SWMM’s capabilities allow cities to thoroughly investigate and evaluate these three control strategies. Understanding the potential benefits and limitations of complete segregation, green infrastructure, and gray infrastructure can help cities develop comprehensive CSO prevention plans and move toward more sustainable and resilient urban environments.

3.1. Separation

Sewer separation can be accomplished by installing a new stormwater or sanitary sewer alongside the existing sewer. The main factors determining the use after separating the existing lines are the economics, capacity, conditions, and arrangement of the combined sewer pipe. EPA’s SWMM is used worldwide for planning, analysis, and design related to stormwater runoff, combined and sanitary sewers, and other drainage systems [

14].

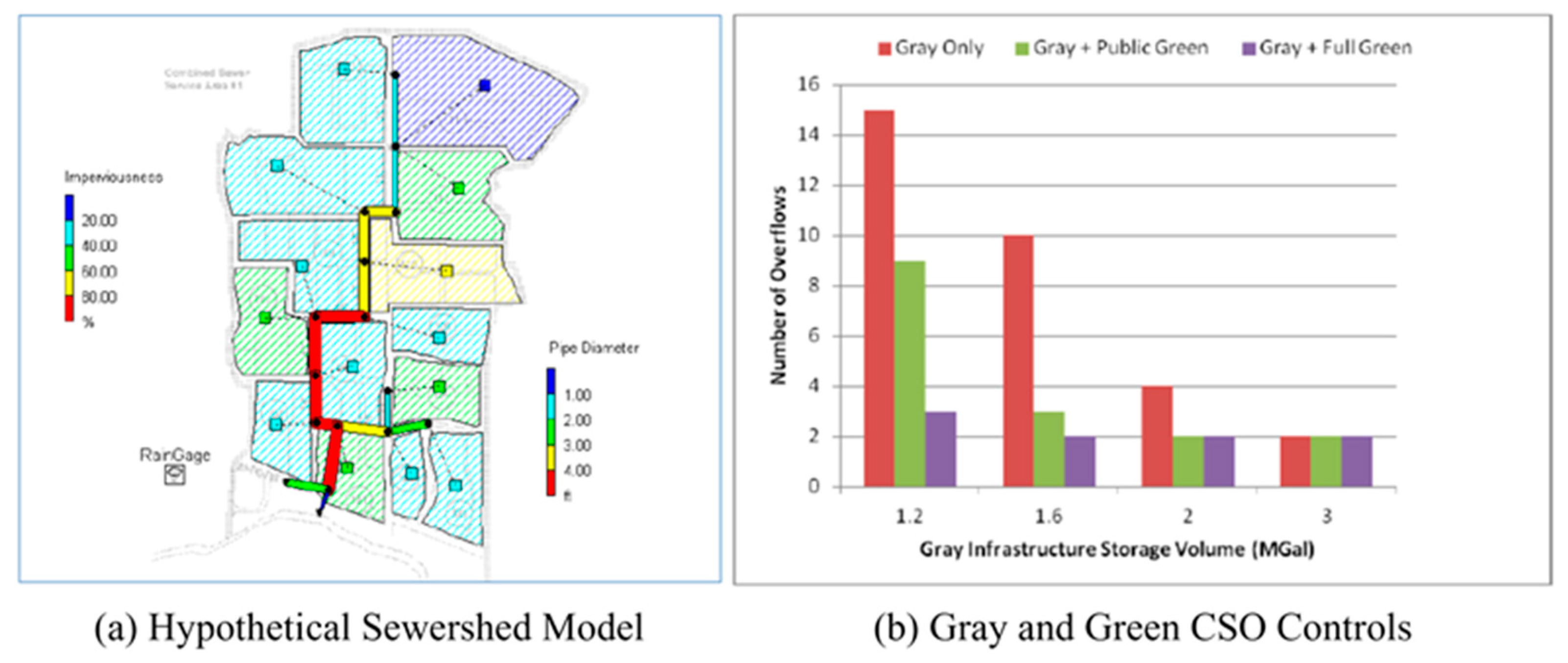

Figure 2 shows a graph developed by the EPA [

15] using various SWMM data as to how various combinations of increased gray infrastructure storage capacity and green methods impact CSOs. The EPA [

14] developed a hypothetical case study to illustrate how a community might use Hydrologic and Hydraulic (H&H) modeling, as shown in

Figure 2(a). Hydrologic indicates where rainwater goes and how much will flow into the sewer network, while hydraulics indicates the volume and velocity of flow in the sewer network. Based on H&H modeling. One can estimate the CSS’s performance and resultant CSO event frequencies and discharge volumes similar to one depicted in

Figure 2(b).

Figure 2(a) also shows a map of a hypothetical CSS that covers a 500-acre service area. From the results of

Figure 2, the city might determine that adding 1.6 million gallons of underground storage along with a robust green infrastructure plan is more cost-effective than simply adding 3 million gallons of underground storage with the same results.

The method used for total prevention of CSOs is the complete separation of the sewer system. For example, the Department of Public Works in Grand Rapids, MI, eventually used this method to solve its CSO problem. Grand Rapids is the second-largest city in the state of Michigan and serves as the county seat of Kent County. At the 2020 Census, the city had a population of 198,917, just under 200,000. [

16]. The city finished converting its combined sewers to separate ones in 2015. During the 1960s, 59 points in the city were identified where raw or partially treated sewage could overflow into a nearby waterbody (the Grand River). 12.6 billion gallons of raw, untreated sewage flowed into the Grand River in 1969. The city spent

$2.7 million on wastewater treatment in 1991 and a

$1.2 million underground storage facility in 2015. They were able to lower CSOs from 12 billion gallons in the 1970s to zero CSO events in 2014. The separation started in 1991 and cost the city

$400 million [

17]. The most significant hurdle for separation is the financial means to construct such a system with limited financial sources. Over 700 cities in the US affected by CSOs have populations of less than 10,000 people [

3]. The costs associated with separation projects are overwhelming and unfeasible for small cities and such cities as Detroit with larger populations and decreasing budgets. One of the largest sewer separation projects is underway in London. It will prevent untreated sewage from the existing Victorian sewer network designed to serve 4 million people [

18]. The Thames Tideway Tunnel is a super sewer to serve 16 million people by 2160. This project will be completed approximately 16 miles (25km) and 25 ft (7.5 m) in diameter in 2025 [

19] and cost

$4.5 billion (£ 3.5 billion) [

20].

3.2. Green Infrastructure

According to the EPA, green methods, as an inexpensive solution, should be included in any CSO reduction plan. Stormwater drainage is achieved through the pervious roads and parking lots, creating green spaces, rain gardens, and bioswales. Retention can be achieved with green roofs, retention ponds, flood plains, and planter trenches. Municipalities using this method often make a call to action in their communities to enact green methods around homes and businesses. They also typically incentivize businesses to use green site plans by creating award programs, lowering permitting fees, taxes, stormwater fees, and offering grants [

21]. Green infrastructure adds value to improving communities by adding green space and beautifying public areas, which is not applied to most gray infrastructure improvements. However, it requires matching public interest and government aspirations for a healthy environment, critical to adequate environmental protection and sustainability. When the two elements work together, they create a more potent force for positive change through green infrastructure. These low costs and added benefits are why the city of Philadelphia focuses 70 percent of its LTCP efforts to curtail CSOs with a 1.7-billion-dollar green infrastructure initiative, including all these methods [

22]. SWMM data suggests a limiting control of CSOs and that green infrastructure cannot be the only method used [

14]. The goal of Green City, Clean Waters is to increase green stormwater infrastructure in Philadelphia to make it a significant portion of the EPA mandated goal to reduce the amount of polluted stormwater overflows discharging into the creeks, streams, and rivers in and around the city by 85% by 2035 [

23]. In most cities, green infrastructure is a secondary or tertiary part of the LTCP.

3.3. Gray Infrastructure

Gray infrastructure for stormwater management refers to a network of water retention and purification infrastructure (such as pipes, ditches, swales, culverts, and retention ponds) meant to slow the flow of stormwater during rain events to prevent flooding and reduce the amount of pollutants entering waterways [

24]. Gray infrastructure improvements are often preferred because they provide a traditional and engineered system with reliability, proven technology, immediate impact, and regulatory compliance. The objective of gray infrastructure in CSOS is to create more storage in the system on the way to the WWTP or to increase the treatment plant’s capacity. Due to the age of combined sewer systems, CSOs are exacerbated by cracked, damaged and improperly fitted pipes. The inflow of water at poor connections or infiltration into pipes through cracks can substantially add to flow during a storm event. Another concern with old pipes is that the internal smoothness changes with scouring and scale buildup over time. These pipes can be replaced or lined with a smoother material that lessens the diameter but increases flow. Through the repairs and maintenance of deteriorated pipes, the capacity of the sewer system can be improved. Further capacity can be gained by increasing the sizes of pipes, especially the interceptors that run perpendicular to CSO outfalls. Adding capacity can also be achieved by adding retention basins or underground storage. One example is the highly ambitious

$3.8 billion Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) project in Chicago. The TARP, also known as “Deep Tunnel,” is a system of deep, large diameter tunnels and vast reservoirs designed to reduce flooding and improve water quality in Chicago area waterways. It protects Lake Michigan from pollution caused by sewer overflows [

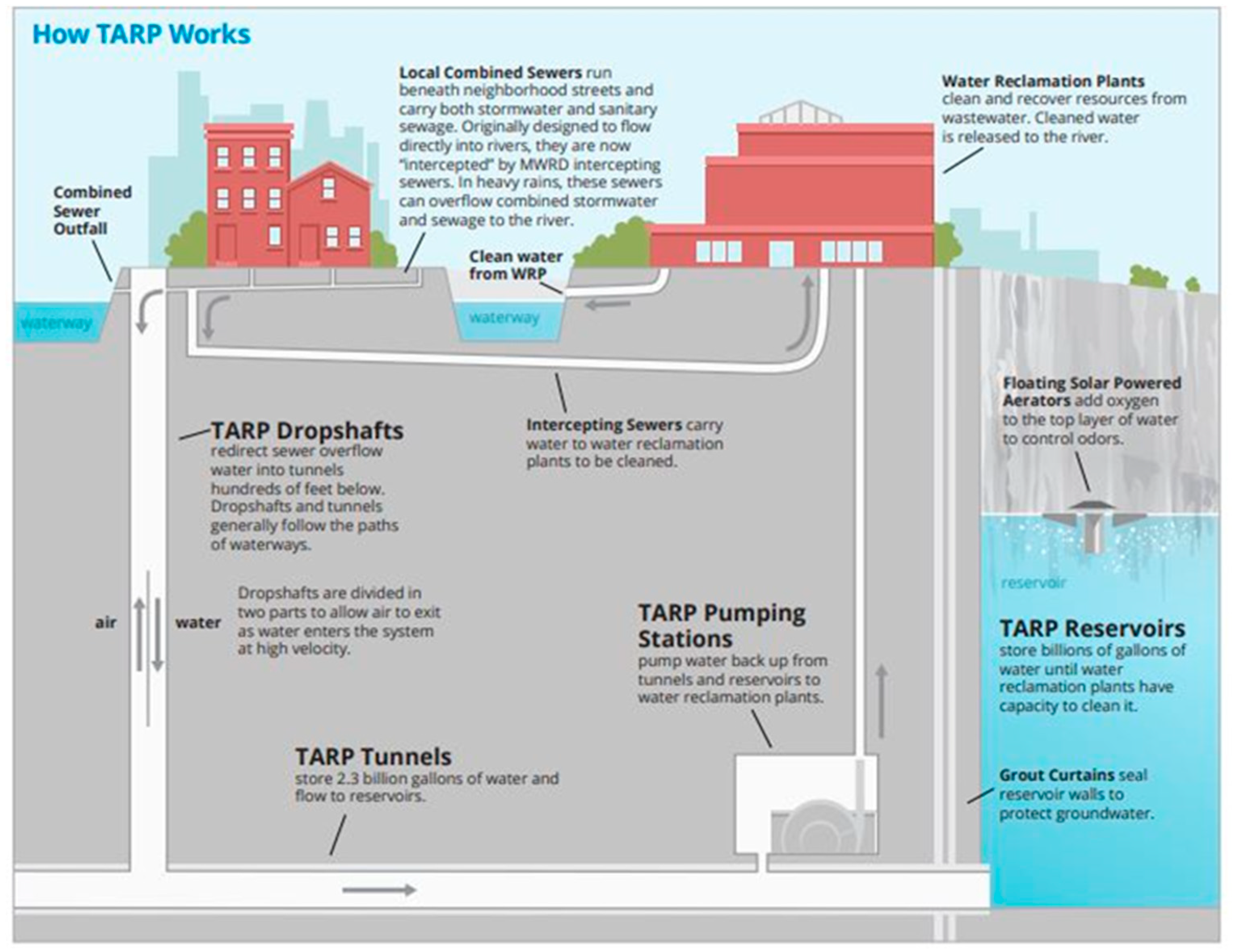

25]. Large underground tunnels have added 2.3 billion gallons of extra capacity to the system, with 110 miles of length completed in 2006. Since the tunnels became operational, CSOs have been reduced from an average of 100 days per year to 50 days. Three reservoirs with a 15.15 billion gallon capacity will be completed by 2029. CSOs will be eliminated in their service area after completion of TARP.

Figure 3 shows how TARP works. The tunnel system captures the “first flush,” the highest pollutant-loaded combined sewer flow. The reservoirs have gone a step further and collected more CSO volume. Many cities are adding similar elements on a smaller scale. SWMM data has shown that gray infrastructure can be a stand-alone method or work in conjunction with green infrastructure [

14].

4. Smart Sewerage Control

These days, many utilities are applying advanced technology and data analysis to traditional sewage systems. In addition to the physical construction of the sewer system, technological integration plays a significant role in improving the efficiency, safety, and sustainability of wastewater and stormwater management. Typical smart technologies for utility include sensor networks, data analytics and Artificial Intelligence, water leak detection, flood detection, and remote monitoring and control. A smart sewage system with these features can become a component of a smart city by integrating with other city infrastructures and services.

In adverse weather conditions, an emerging control method may be able to control CSOs as situations change within the system. Wireless-enabled sensors, such as weirs, gates, pumps, and valves, are strategically placed in the wastewater system. The primary goal of using wireless-enabled sensors and smart control systems in wastewater management is to optimize the use of available capacity by strategically moving wastewater within the system. The system can effectively manage the flow of wastewater, prevent overloading in certain areas, and make the best use of the existing infrastructure. During storm events, certain parts of the CSS can become overwhelmed due to the sudden increase in water flow, leading to CSOs where untreated or partially treated wastewater is discharged into the environment to prevent flooding. However, other areas within the system may have spare capacity and can handle additional flow without causing overflows. By leveraging wireless-enabled sensors, smart control can identify these areas with available capacity. This technology solves the problem by redistributing flow in pipes close to capacity and directing them to other pipes with free space. Simplify integrated sewage systems and enable more sophisticated real-time monitoring capabilities.

The technology consists of sensors that collect and relay information, repeaters that fill distant gaps across the grid, and gateways that share information with a database and process information. The wireless sensors are designed to be placed under sewer holes. A smart control device is made up of three portions: 1) sensors, 2) repeaters, and gateways. The sensors consist of several components: a mote, which is a small and economical computer approximately the size of a quarter, a time-keeping chip, an 8-megabyte storage chip, a battery pack, a radio with an inverted antenna, and the option to incorporate up to four sensor probes. The two probes measure the water level and flow rate. The repeaters are hard-wired, similar to the sensors but contain no sensor probes. The gateways are wired and sit above street level. They contain a small, Linux-based computer, a cellular modem, a 900 MHz radio, and an interface to control parts of the sewer. The gateway uses a Cloud Based Network to transmit all information to a control center where public works can monitor it. The information is also shared between the gateways and is used to control the actuators to use the system’s capacity optimally. The wired actuators operate the weirs, gates, pumps, and valves. The gateways operate under multiple control algorithms. One control uses a switching algorithm that opens and closes a valve as capacity is reached. Another algorithm allows sensors to begin to compute for capacity in which the pipes with the lowest capacity are able to collect more wastewater. If one or more pipes have more flow capacity, valves will be activated to shut, allowing fuller pipes to drain while others fill close to capacity. With another algorithm using weather forecasting schemes, the amount of runoff needed to be collected is anticipated, and the system makes room early in the process [

26].

4. Case Study of South Bend, Indiana

In South Bend, Indiana, there are 36 outfalls, and the city processes a daily volume of 48 to 77 million gallons of water [

27]. The average yearly rainfall in this region is 38 inches [

28]. From 1990 to 2004, South Bend experienced an average of 2 billion gallons of CSOs and invested

$87 million in CSO infrastructure. In 2004, the city submitted its LTCP to the EPA to address this issue. The plan involved separating some CSO outfalls, upgrading the WWTP, and installing nine underground storage tanks across the city. In 2008, the City of South Bend embarked on a transformative initiative known as the CSOnet project. This project proved highly successful, prompting the city to update its long-term control plan to incorporate the CSOnet system. CSOnet is a cutting-edge real-time decision support system, granting the City of South Bend a profound understanding of its sewer system while providing greater control and optimization capabilities. With CSOnet in place, the city can now effectively minimize sewer overflows into the river and fully maximize the capacity of its existing infrastructure, a significant environmental achievement. In 2017, Phase I of South Bend’s LTCP was completed, which involved several critical tasks. The plan included separating numerous sewers, strategically installing throttle valves at various outfalls, and integrating an impressive network of 150 sensors and 12 actuators. These sensors and actuators effectively control nine pumps and three weirs, adding sophisticated management and efficiency to the city’s sewer system. Phase I costs exceeded

$150 million, but the CSOnet improvements cost only

$6 million.

CSOnet brings three significant benefits to the city’s sewerage management system. Above all, the entire integrated sewage network can be monitored in real-time. This continuous monitoring allows any potential problem or anomaly to be immediately detected and addressed. Second, CSOnet optimizes water flow at CSO outlets to ensure these outlets operate at peak efficiency, reducing the risk of sewage overflow and minimizing environmental impact. Third, the system is proactive by strategically draining clean reservoirs and reservoirs prior to expected heavy rainfall events. This preemptive measure creates additional capacity within the system, mitigating the risk of overloading the sewerage infrastructure during heavy rains. To achieve this, it collects data from an extensive network of 150 sensors that forward the information to 17 gateways. Data is transferred to a central database using cloud-based technology. This database allows data to be collected and shared in real-time. The city leverages IBM’s Intelligent Operations Center software, along with supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) information and the city’s geographic information system (GIS), to visualize and understand data. Integrating these technologies creates a comprehensive interface that gives public works departments a real-time view of the entire pipe network. Within this geospatial representation, public works teams can easily access important information such as current pipe levels, watershed levels, remaining storage capacity in basins, and CSO occurrences. Enhanced situational awareness allows cities to proactively manage their sewage systems and respond effectively to urgent problems or incidents.

Numerous improvements could come from these observations. Many dry weather CSOs and backflow often originate from blockages in a pipe. These blockages can appear due to the intrusion of tree roots or the accumulation of debris. The financial impact of dry CSOs is significant, given their unpermitted status and associated substantial fines. Additionally, the repercussions extend to property damage, incurring multimillion-dollar city costs annually. Overtime data can help provide a comprehensive understanding of expected flow in pipes under normal and peak conditions. If a pipe exceeds established normal levels, a city can effectively establish a proactive maintenance protocol to prevent overflow and backup by dispatching staff to rectify blockages. This preventive maintenance system is essential instead of fixing pipes after overflows and backups. In particular, South Bend’s implementation of this approach has had remarkable results. The system helped the utility eliminate critical dry CSOs, which occurred an average of 27 times per year, by isolating maintenance issues in the first year of operation [

29].

Another critical benefit is inflow and infiltration (I/I) management. I/I can be identified through the events of higher-than-anticipated flows during storms or heavy rains. The final advantage encompasses the utilization of collected data for system operation, such as SWMM or analogous modeling tools. These applications facilitate a more profound understanding of the system dynamics and deficiencies in capacity. This data-driven insight empowers municipalities to judiciously allocate resources toward critical gray infrastructure investments (Smith et al., 2019).

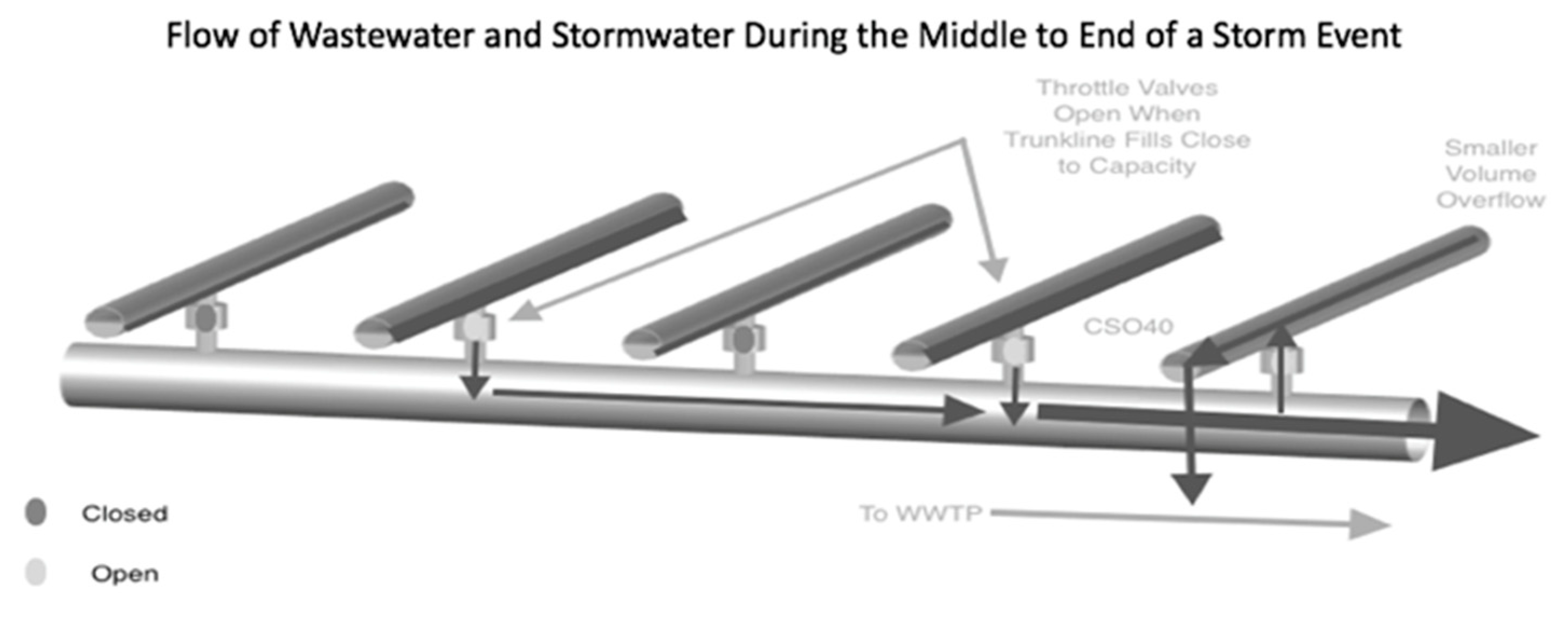

In South Bend, various sensors form the efforts to prevent CSOs at outfalls along the St. Joseph River. These outfalls are outfitted with weirs that impede the entry of wastewater into the river. Instead, the wastewater is rerouted into a throttle line intricately linked to an interceptor leading to the wastewater treatment plant. In the case of moderate rainfalls, an interesting observation emerged. Some outfalls remained free of overflow while others experienced it. This discrepancy suggested that the interceptor had not yet reached its maximum capacity. The potential solution was to arrest the flow of stormwater at the main lines of non-overflowing outfalls. This approach would generate additional capacity within the interceptor, facilitating faster drainage for those trunk lines that were indeed overflowing.

Considering this notion, a series of valves were introduced to each throttle line strategically positioned between the trunk line and the interceptor. The functioning of these valves was regulated by a competitive algorithm, granting them the ability to open and close in response to conditions. In the midst of a storm event, the throttle valves associated with trunk lines at full capacity are allowed to release their contents into the interceptor via controlled openings controlled by the CSOnet system. Meanwhile, the other throttle valves remain shut until each corresponding trunk line attains a predetermined parameter, signaling the valve to “compete” for access to the interceptor. This setup fosters a dynamic allocation of resources, optimizing the utilization of the interceptor and effectively managing CSOs during varying storm conditions.

Figure 3 shows how the algorithm would operate during a storm event. This algorithm also relies on real-time data but focuses on dynamically adjusting the flow rates and storage volumes of different parts of the sewer network to prevent overflows. It uses predictive models to anticipate CSOs and make adjustments accordingly. The dynamic control strategy relies on continuously gathering feedback from each time step [

8].

The last significant benefit of CSOnet is creating storage for stormwater before a storm event happens. A high stormwater flow event can be anticipated in accordance with weather prediction algorithms. It can trigger CSOnet to dynamically activate pumps to drain retention basins into the river before the storm occurs. Less stormwater gets into the sewer system by allowing more space for stormwater.

Since the implementation of CSOnet in 2008, along with the other Phase I CSO infrastructure improvements, CSOs have dropped from 2.1 billion gallons in 2008 to 458 million gallons in 2014. Phase 1 was completed in 2017. The Smart Sewer System provides data for various parameters, including flow, depth, velocity, and weir/gate control valve position. The system also contains smart moving valves that direct flow in the sewer and control stormwater basin levels. SWMM data suggests that CSOnet has removed over 75% of the annual CSO volume and prevented more than 1,500 million gallons of combined sewage from entering the St. Joseph River yearly [

27].

4. Smart Swerage Control Application

Many cities are still conveyed rainwater and wastewater in the same pipe network. A CSO occurs when excess rain overloads these pipes, and dirty water flows into the river. As federal regulation requires, many cities are upgrading their sewer system to end this practice and improve local water quality to establish an LTCP. Rapid economic development, massive population growth, and global climate change generate tremendous pressure on infrastructure planning and development as a part of the LTCP. The LTCP encompasses the complicated strategic process in assessments and analysis, budgeting and financing, design and engineering, regulatory approvals, and construction and implementation for the functioning of a society or community. It also faces challenges such as funding limitations, bureaucratic hurdles, environmental concerns, and ensuring equitable distribution of benefits. Therefore, fully maximizing the capacity of the existing infrastructure with smart control is considered a cost-effective and straightforward solution to reduce peak runoff and CSOs.

Richmond, VA, focuses on traditional methods using primarily grey and green infrastructure improvements, monitoring, and modeling. Research suggests that by combining current efforts with wireless sensor technology, Richmond can better meet its LTCP goals to prevent CSOs by inexpensively enhancing monitoring, dynamically controlling stormwater flow, and making more informed decisions on infrastructure improvements.

4.1. Application to City of Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia, has faced tremendous challenges with combined overflows. According to US Census Bureau 2020, Richmond has a population of over 226,000 and an area of 62.5 square miles [

16]. Richmond receives an average of 43 inches of rain annually [

30]. Parts of Richmond’s first sewer system are over 150 years old and were designed as a CSS that services 18.8 square miles [

31]. Richmond began addressing CSO problems back in the 1970s. Richmond had 31 CSO outfalls along the James River or its tributaries, especially Shockoe Creek and Gillies Creek [

32,

33]. Richmond has implemented green infrastructure (i.e., rain gardens, green roofs, rain barrels and cisterns, and permeable pavement) and gray infrastructure. Gray infrastructure projects improve water quality, including replacing combined sewer pipes with separated pipes for wastewater and stormwater, building storage facilities to hold excess water, and increasing the capacity of the Wastewater Treatment Plant. In its LTCP, Richmond’s central strategy involved the construction of an extensive storage mechanism designed to capture the influx of stormwater blended with untreated sewage following rainfall [

31,

34]. According to the General Assembly Report [

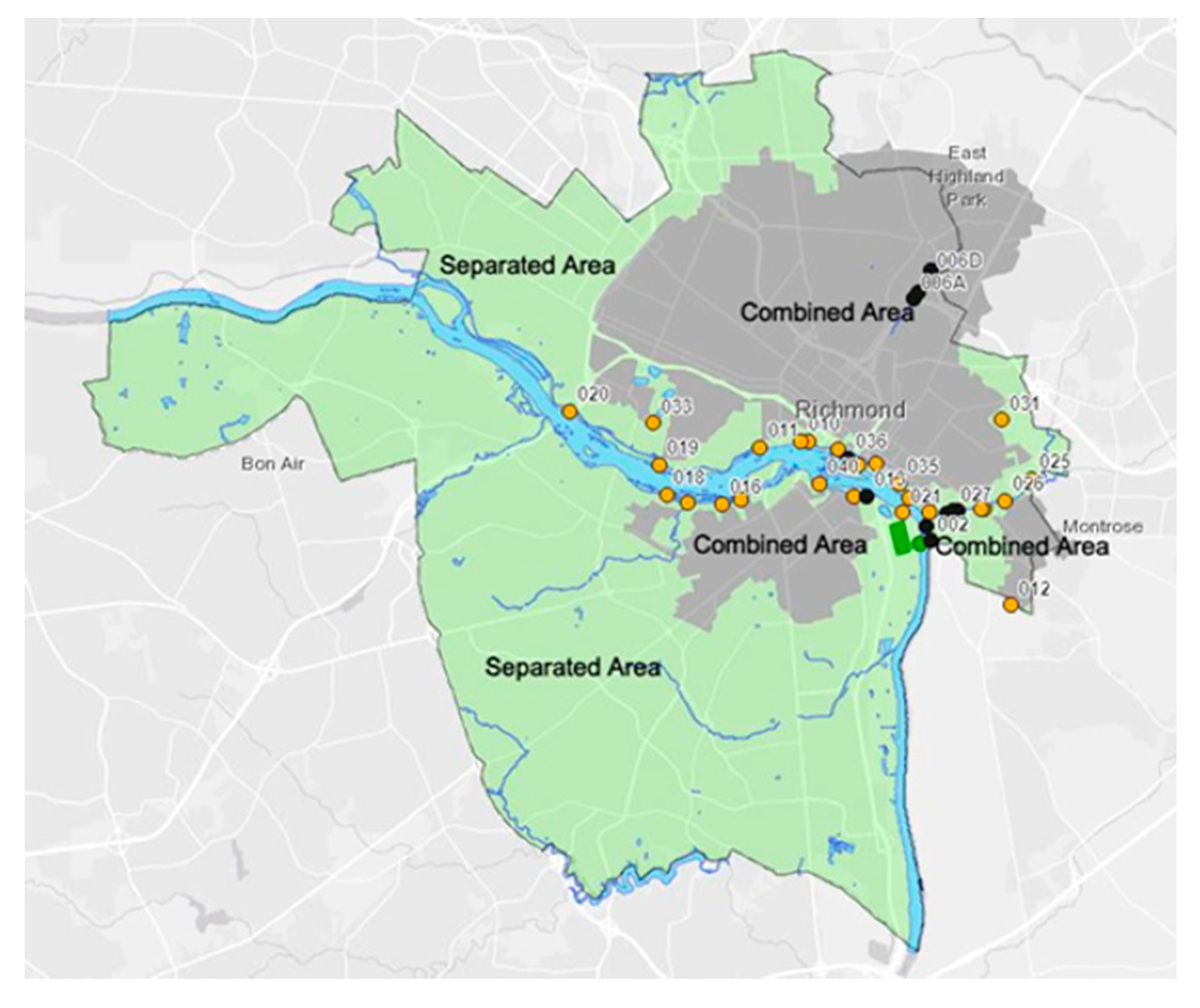

35], Richmond’s CSS area covers 19 square miles and includes 25 combined sewer outfalls, as shown in

Figure 4. Approximately 32% of the city’s land area is within the combined sewer area, with 52% of the city’s population. In

Figure 4, 7 black dots indicate closed outfalls from 31 active outfalls with investments in grey and green infrastructures and RVA Clean Water Plan for monitoring and modeling.

CSS improvements from 1970 to 2022, the Shockoe Retention Basin completed in 1983 with a 50-million-gallon connection to the main combined sewer line. The basin can divert water by weirs just before the WWTP, contributing to minimal overflow at 10 CSO outfalls. Another major storage improvement implementation was adding an underground storage tunnel deep within an underlying granite layer. The Hampton-McCloy Tunnel, completed in 2003, stores 7 million gallons and has helped significantly lower CSOs in 3 outfalls near an important recreational area. After completing Phase 2 from 1988 to 2002, Richmond could capture 85% of CSO. The WWTP has been increased to treat 75 million dry flow gallons or 140 million gallons of storm flow per day with Phase 3 [

36].

Richmond has placed importance on monitoring and modeling the sewer and stormwater systems. These methods include mapping the CSO areas, reviewing documents to show pipe lengths, material, and diameter, taking water samples, and monitoring CSO flow. The city’s efforts have improved the CSO capture rate to approximately 91%. This means that CSO flowing into the James River has been reduced by more than 3 billion gallons yearly [

35].

Richmond mapped out a three-phase plan in the LTCP plan to the EPA. Currently, phases I and II are complete, including the Shockoe Basin and the Hampton-McCloy tunnel. In Phase III, many implementations are planned, such as increasing storage capacity, upgrading the wastewater treatment plant, installing green infrastructure, and educating the public and planning for the future. The CSO infrastructure improvement plan includes increasing wet weather treatment capacity to 300 million gallons per day, disconnecting two outfalls, increasing the interceptor line in the lower Gillies Area, replacement of a regulator and adding a million gallons of storage at a problematic outfall, adding 15 million gallons of storage to the Shockoe basin, and chlorine disinfection at another problematic outfall. Phase III green infrastructure plans include creating 18 acres of impervious surfaces. It can be done by improving 6 acres of public utility property, 2 acres of city-owned vacant properties, and 2 acres of public parks, and installing 24 tree boxes of 8 acres total drained to the Combined Sewer System area [

37]. Data collected from SWMM shows a ten-million-gallon annual drop in CSOs from all the green infrastructure implementations and a drop from 1.67 billion gallons to 228 million gallons from the gray infrastructure improvements.

4.2. Cost Comparison with SWMM

EPA’s SWMM is used for planning, analysis, and design related to stormwater runoff, combined and sanitary sewers, and other drainage systems. It can be used to evaluate gray infrastructure stormwater control strategies, such as pipes and storm drains, and create cost-effective green/gray hybrid stormwater controls [

14]. SWMM data can identify the number of gallons of CSOs that various methods can forestall. By dividing these figures by projected expenses, it becomes possible to determine the cost incurred per million gallons of yearly CSOs.

Table 1 shows a substantially lower cost for the city of South Bend’s Wireless Sensor method than Richmond’s gray and green methods or Grand Rapid’s total separation.

4.3. The Benefit of Integrating Wireless Technology in Richmond, VA

Richmond has implemented diverse strategies to mitigate CSOs, aiming to manage the intricate interplay between human activities, rainfalls, snow melts, inflow and infiltration, pipe obstructions, floods, river currents, and evolving weather patterns. Despite investing significant amounts, exceeding hundreds of millions of dollars, into initiatives like green infrastructure, sewer upkeep, facility upgrades, and expansive subterranean reservoirs, the city finds a static solution for CSOs. It is considered a passive system in which all components are set in place to control dynamic forces. While the system works well on most days, it still does not entirely stop the millions of gallons of CSOs that occur on many days. Richmond’s CSOs only happened 94 days in 2022, adding up to 262 billion gallons [

36]. Designers of the static system have to overcompensate to allow the system to handle the higher peaks of the SWMM hydrographs.

An example is shown in a cost versus benefit study to determine the value of increasing the interceptor size in Richmond’s Gillies Creek area. It was determined through SWMM that it would cost

$300 million for storage that would only be at full capacity once every five years based on 5-year storm models. Preparedness for a five-year storm is not even in the scope of an EPA control policy. At this gray infrastructure level, costs increase exponentially for small percentage gains. In static systems, achieving 100 percent control is almost impossible [

38]. Richmond’s LTCP only plans a 92% reduction in CSOs [

36].

Integrating wireless sensors into Richmond’s LTCP could bring substantial advantages. The city’s efforts to manage CSOs have hinged on activities like monitoring, data collection, and modeling. Enhancing to manage CSOs is possible through the utilization of real-time monitoring, effectively harnessing Richmond’s existing SCADA and GIS capabilities in conjunction with the technology. By incorporating monitoring, the reduction of Infiltration and Inflow (I/I), obstructions, and dry weather CSOs can be accomplished. Furthermore, optimizing the system to ensure that only stormwater enters through drains could augment its capacity significantly.

A pivotal strategy involves optimizing the city’s sewer infrastructure. Leveraging data collection, Richmond can gain invaluable insights into identifying pipes requiring lining or replacement. Richmond has many CSO locations that can improve by controlling flow and creating more capacity. With the strategic integration of wireless sensors and pumps, the flow redirection from problematic CSO outlets to the nearby dual 7-foot diameter interceptors is feasible. Notably, The majority of CSOs are occurring at the outfalls that drain to smaller interceptors. These areas can improve highly effectively by adding actuated valves and an added throttle line similar to South Bend.

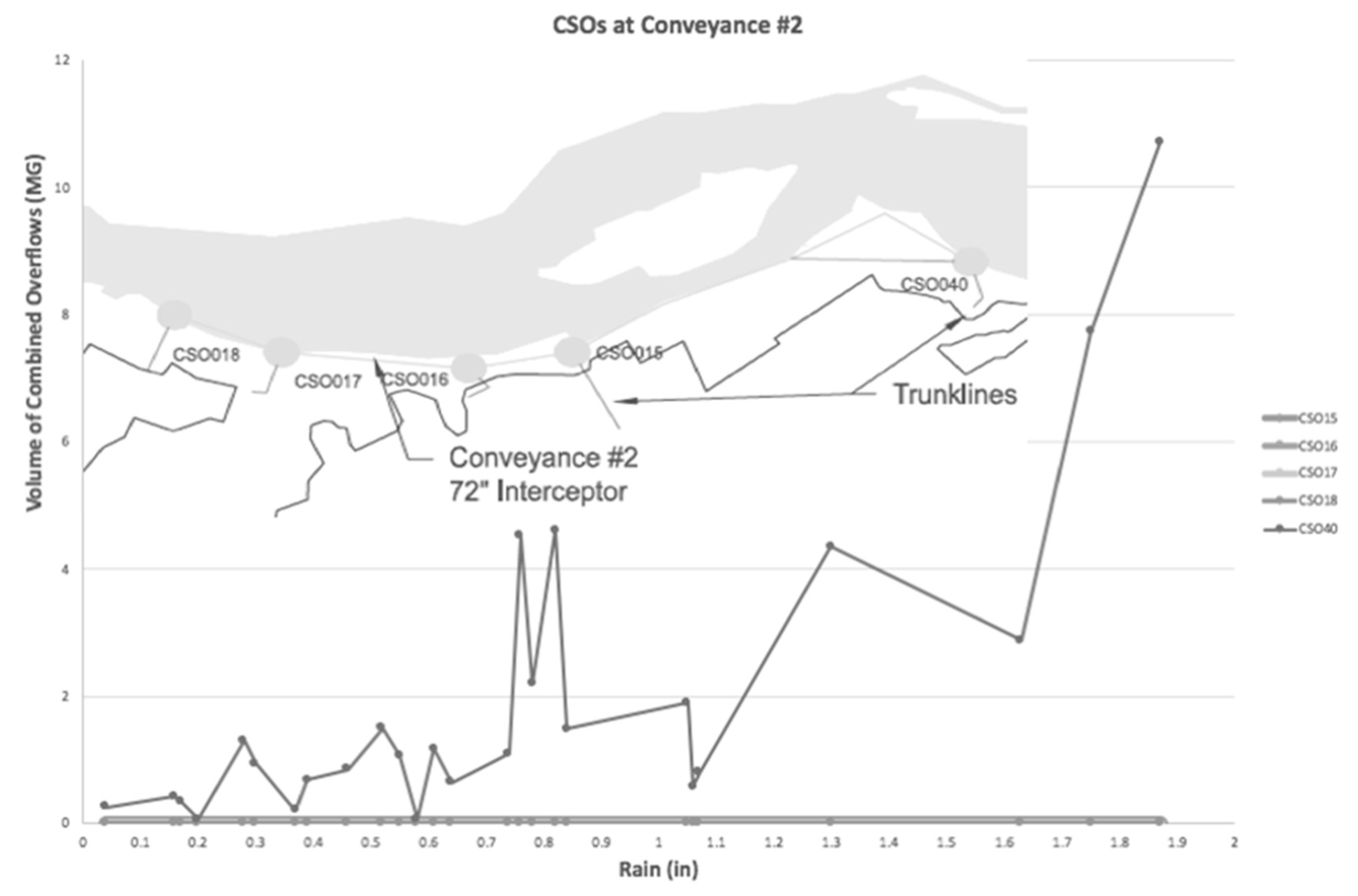

Using SWMM of CSO data gathered between July 2017 to June 2018, as documented in Richmond’s CSO Monthly Reports, a striking resemblance emerges between Richmond and South Bend’s predicament. CSOs are happening at some trunk line outfalls sharing an interceptor but not at others. It can be observed in

Figure 5.

Both cities experience CSOs at specific trunk line outfalls that share an interceptor, while other points in the network remain unaffected. The correlation underscores the potential for Richmond to adapt successful strategies from South Bend to ameliorate its CSO challenges. Only the outfall “CSO40” at the end of the interceptor has CSOs during rainfalls of less than 2 inches. Controlling flow in the Gillies Creek area can also help Richmond lower the cost of the $300 interceptor as part of Phase III of the LTCP.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Numerous municipalities are actively addressing the EPA’s requirements for controlling CSOs, employing diverse strategies to bring CSO levels within acceptable limits. While separation has demonstrated the most successful CSO control, financial constraints render this option unfeasible for many urban centers. As a result, most cities are compelled to manage CSOs through augmentations or adaptations to their existing infrastructure. Predominantly, these efforts have leaned heavily on the SWMM, employing a foundational stormwater flow as a baseline for predicting CSO changes. It informs the city on how and where implementations should be made. Nonetheless, this static system yields a somewhat rigid framework designed to support combined stormwater and wastewater flow during high peak flow events. This methodology guides municipalities in pinpointing strategic implementation areas to reinforce the system’s capacity for handling peak flow scenarios. Integrating gray and green infrastructure has yielded modest successes, albeit at a considerable cost escalation, as the pursuit of more significant percentage gains continues.

In this circumstance, wireless technology emerges as a dynamic solution to address the intricacies of these intricate and turbulent systems. The capacity for real-time monitoring introduces a level of seamlessness in data collection, fostering the creation of more precise models. The consequential benefit is enhanced decision-making for future projects. Real-time modeling has exhibited remarkable efficacy in curbing unauthorized dry CSOs and promptly identifying system deficiencies. Wireless sensor technology has effectively averted CSOs by leveraging existing infrastructure at a fraction of the cost of alternative methods.

South Bend’s case serves as a testament to the cost-effective potential of this technology in CSO control. Nevertheless, it becomes evident that wireless sensor technology alone is not a comprehensive solution. The optimal CSO reduction is achieved by its integration with other control methods. Similarly, Richmond, a comparable municipality, can benefit substantially from this technology. Abundant untapped capacity resides within their current infrastructure, fortified by a robust commitment to ongoing data collection. The real-time monitoring potential can significantly enhance modeling accuracy, leading to well-informed decisions regarding gray and green infrastructure enhancements.

Richmond’s earnest endeavors in CSO management, approaching the halfway mark of their goal, are poised to evolve further as they embark on Phase III of their LTCP. The analysis of SWMM data signals the potential for more effective CSO control through the assimilation of wireless sensor technology. This approach, in essence, could serve as a transformative leap in their ongoing CSO mitigation journey.EPA’s SWMM is used for planning.

References

- W. Zhao, T. H. Beach, and Y. Rezgui, “Automated Model Construction for Combined Sewer Overflow Prediction Based on Efficient LASSO Algorithm,” IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst., vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 1254–1269, 2019. [CrossRef]

- United States Government Accountability Office, “CLEAN WATER ACT EPA Should Track Control of Combined Sewer Overflows and Water Quality Improvements.” Jan. 2023.

- US EPA, “Report to Congress on Impacts and Control of Combined Sewer Overflows and Sanitary Sewer Overflows.” 2004.

- City of Alexandar, “Types of Sewer Systems,” City of Alexandria, VA. https://www.alexandriava.gov/sewers/types-of-sewer-systems (accessed Jul. 25, 2023).

- C. Brokamp, A. F. Beck, L. Muglia, and P. Ryan, “Combined sewer overflow events and childhood emergency department visits: A case-crossover study,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 607–608, pp. 1180–1187, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jalliffier-Verne et al., “Cumulative effects of fecal contamination from combined sewer overflows: Management for source water protection,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 174, pp. 62–70, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A.-S. Madoux-Humery et al., “The effects of combined sewer overflow events on riverine sources of drinking water,” Water Res., vol. 92, pp. 218–227, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- U. Rathnayake and A. H. M. F. Anwar, “Dynamic control of urban sewer systems to reduce combined sewer overflows and their adverse impacts,” J. Hydrol., vol. 579, p. 124150, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Dirckx, H. Korving, J. Bessembinder, and M. Weemaes, “How climate proof is real-time control with regard to combined sewer overflows?,” Urban Water J., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 544–551, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M.-È. Jean, S. Duchesne, G. Pelletier, and M. Pleau, “Selection of rainfall information as input data for the design of combined sewer overflow solutions,” J. Hydrol., vol. 565, pp. 559–569, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Tavakol-Davani, S. J. Burian, J. Devkota, and D. Apul, “Performance and Cost-Based Comparison of Green and Gray Infrastructure to Control Combined Sewer Overflows,” J. Sustain. Water Built Environ., vol. 2, no. 2, p. 04015009, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, N. Martinez, G. Lindholm, and H. Ratnaweera, “Manage Sewer In-Line Storage Control Using Hydraulic Model and Recurrent Neural Network,” Water Resour. Manag., vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 2079–2098, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zimmer Andrea, Schmidt Arthur, Ostfeld Avi, and Minsker Barbara, “Reducing Combined Sewer Overflows through Model Predictive Control and Capital Investment,” J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag., vol. 144, no. 2, p. 04017091, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- US EPA, “Greening CSO Plans: Planning and Modeling Green Infrastructure for Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Control.” Mar. 2014.

- US EPA, “Storm Water Management Model (SWMM),” May 21, 2014. https://www.epa.gov/water-research/storm-water-management-model-swmm (accessed Jul. 28, 2023).

- US Census Bureau, “2020 Census,” Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/2020census (accessed Jul. 28, 2023).

- City of Grand Rapids, “Wastewater Treatment.” https://www.grandrapidsmi.gov/Government/Departments/Environmental-Services/Wastewater-Treatment (accessed Jul. 28, 2023).

- Tideway, “Reconnecting London with the River Thames,” Tideway. https://www.tideway.london/ (accessed Aug. 23, 2023).

- Tideway, “The Tunnel,” Tideway. https://www.tideway.london/the-tunnel/ (accessed Jul. 29, 2023).

- R. Butler, “Thames Tideway ‘super-sewer’ cost rises to £4.5bn,” Construction Wave, Apr. 26, 2023. https://constructionwave.co.uk/2023/04/26/thames-tideway-super-sewer-cost-rises-to-4-5bn/ (accessed Jul. 29, 2023).

- US EPA, “Clean Watersheds Needs Survey 2012 Report to Congress,” 2012.

- “Philadelphia Water Department.” https://water.phila.gov/ (accessed Jul. 29, 2023).

- “PennFuture | Home.” https://www.pennfuture.org/ (accessed Jul. 29, 2023).

- “Stormwater Management – Gray Infrastructure.” https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/eslm/stormwater-management-gray-infrastructure (accessed Jul. 29, 2023).

- Metropolitan Water Reclamation and District of Greater Chicago, “Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago.” https://mwrd.org/tunnel-and-reservoir-plan-tarp (accessed Jul. 29, 2023).

- L. Montestruque and M. D. Lemmon, “Globally Coordinated Distributed Storm Water Management System,” in Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Cyber-Physical Systems for Smart Water Networks, in CySWater’15. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015. [CrossRef]

- City of South Bend, “Public Works,” South Bend, Indiana, May 14, 2018. https://southbendin.gov/department/public-works/ (accessed Aug. 04, 2023).

- WorldClimate, “South Bend, Indiana Climate - 46601 Weather, Average Rainfall, and Temperatures,” WorldClimate. http://www.worldclimate.com/climate/us/indiana/south-bend (accessed Aug. 04, 2023).

- B. Kerkez et al., “Smarter Stormwater Systems,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 50, no. 14, pp. 7267–7273, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- WorldClimate, “Richmond, Virginia Climate - 23274 Weather, Average Rainfall, and Temperatures.” http://www.worldclimate.com/climate/us/virginia/richmond (accessed Aug. 16, 2023).

- City of Richmond, “Combined Sewer System – RVAH2O.” https://rvah2o.org/combined-sewer-system/ (accessed Aug. 16, 2023).

- R. C. Steidel, R. Stone, L. Liang, E. J. Cronin, and F. E. Maisch, “Downtown Shall not Flood again,” Proc. Water Environ. Fed., vol. 2006, no. 9, pp. 3769–3795, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- US EPA, “Report to Congress Implementation and Enforcement of the Combined Sewer Overflow Control Policy.” Dec. 2001.

- C. Grymes, “Combined Sewer Overflow (CS0) in Richmond,” VirginiaPlace.org. http://www.virginiaplaces.org/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed Aug. 17, 2023).

- City of Richmond, “Richmond Combined Sewer Overflow Outfall Progress Report (2022).” City of Richmond 2022 General Assembly Report, Nov. 2022.

- City of Richmond Public Utilities, “Efforts to Manage the City’s Combined Sewer System | Richmond.” https://www.rva.gov/public-utilities/news/efforts-manage-citys-combined-sewer-system (accessed Aug. 18, 2023).

- Richmond Department of Public Services, “2017 RVA Clean Water Plan.” Sep. 2017.

- T. Smith, J. Ahn, and Y. Jung, “The Use of Smart Wireless Technology for the Effective Management of Combined Sewer Overflows in Richmond, Virginia,” presented at the 55th ASC Annual International Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).