Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Synthetic methods of MOFs

2.1. Hydrothermal technique

2.2. Solvothermal method

2.3. Sol-gel

2.4. Other methods

3. MOFs for dye-sensitized solar cells

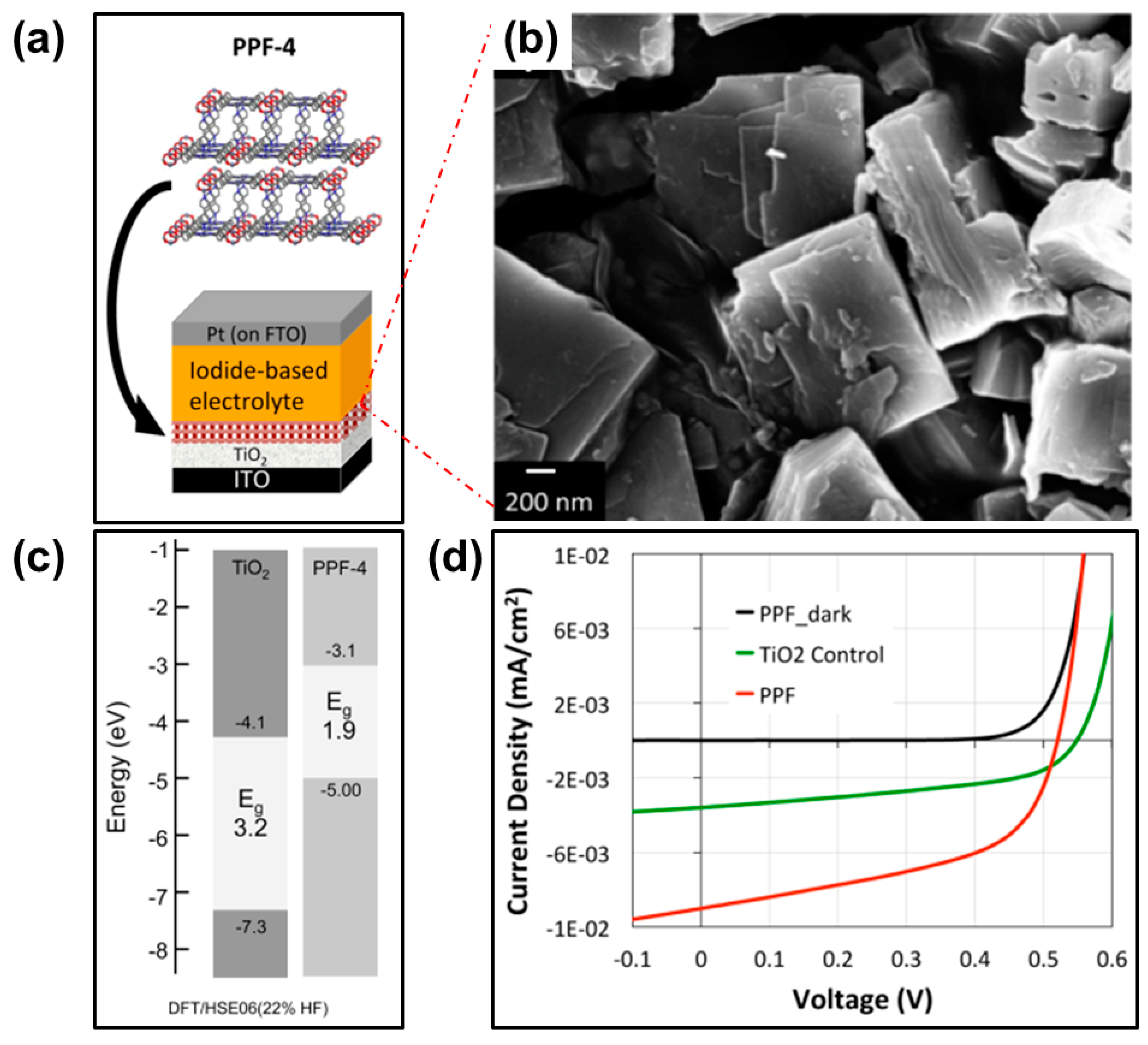

3.1. MOFs as photoanodes

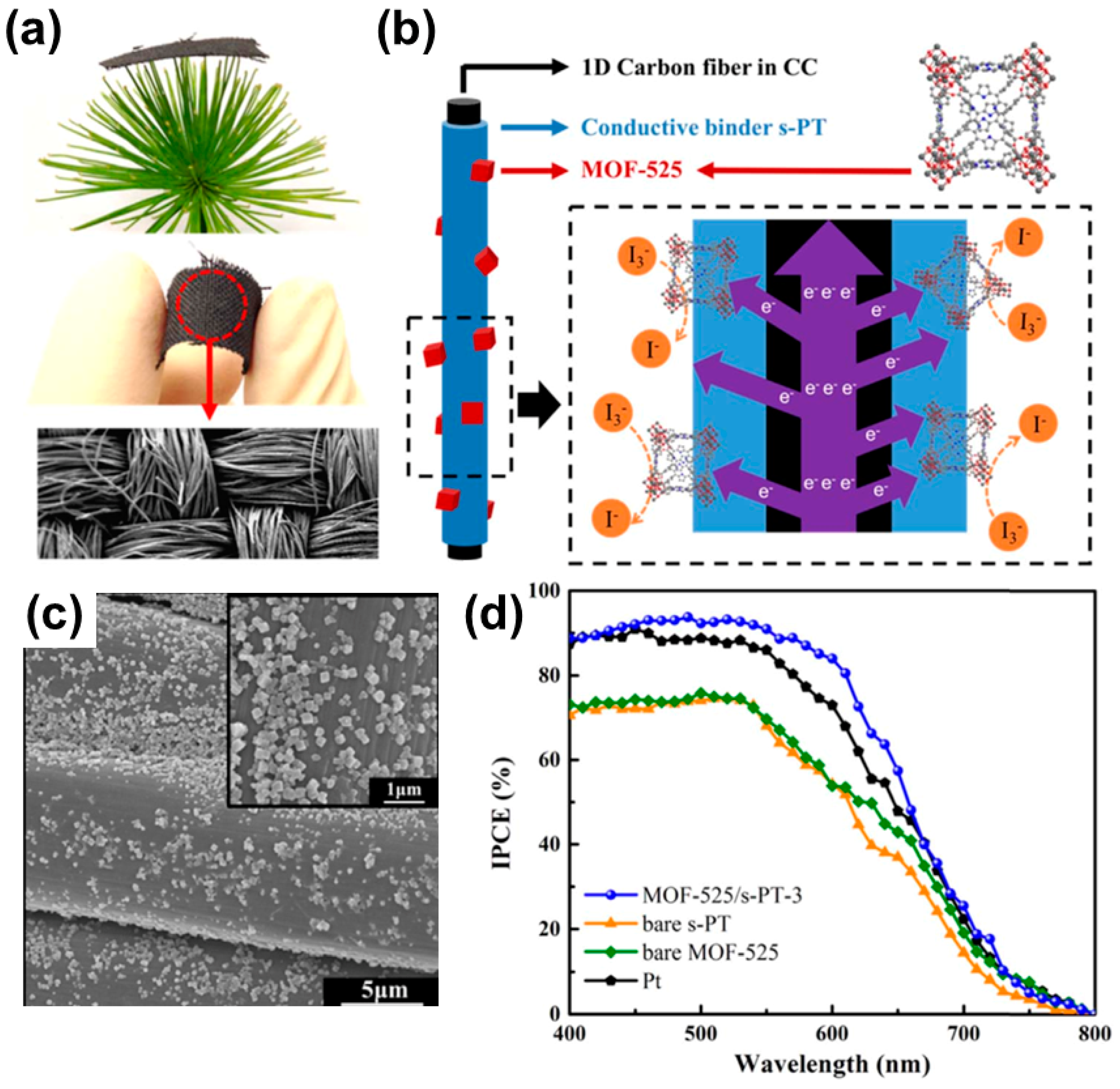

3.2. MOFs as counter electrodes

4. MOFs for perovskite solar cells

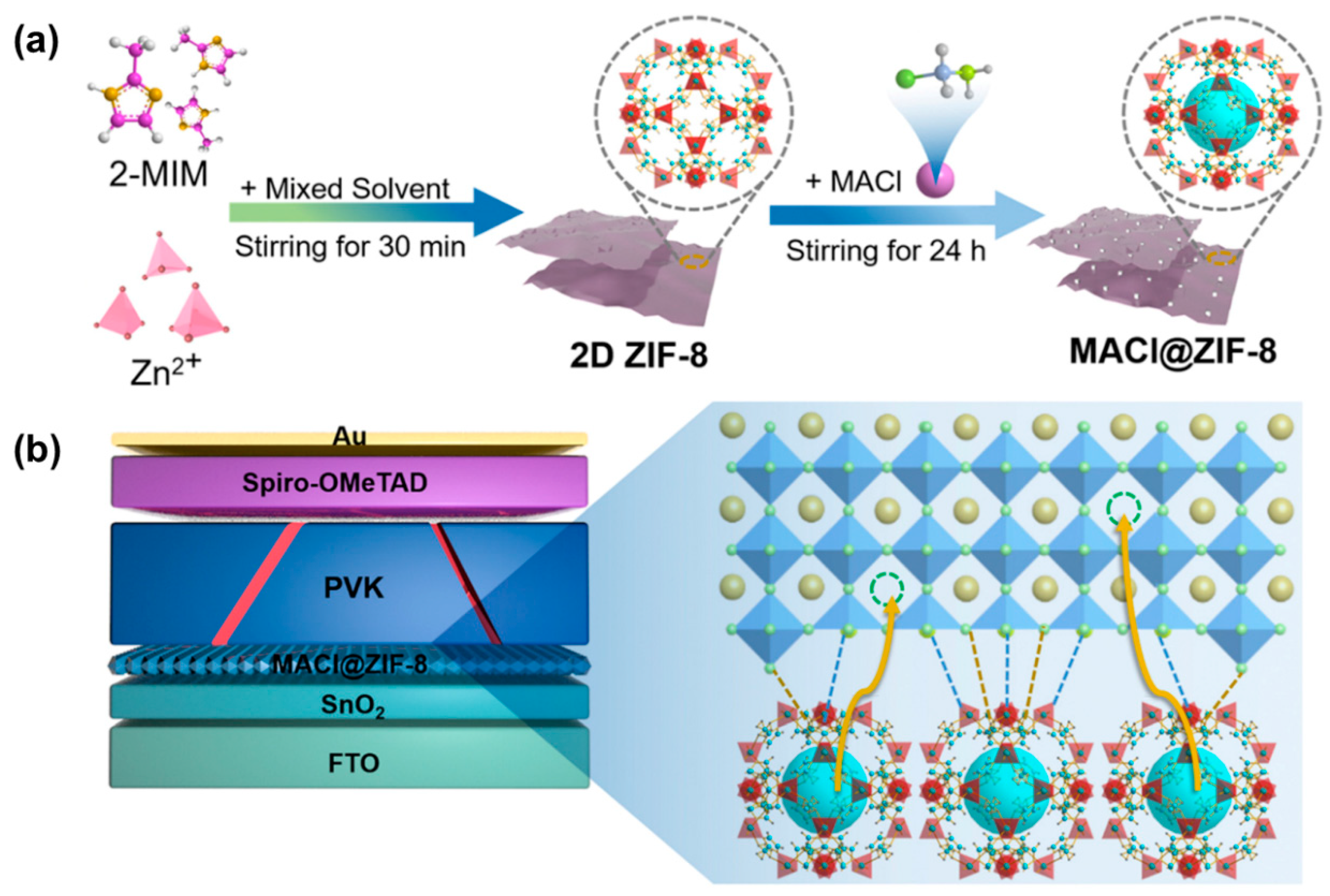

4.1. MOFs as interfacial layers (IL)

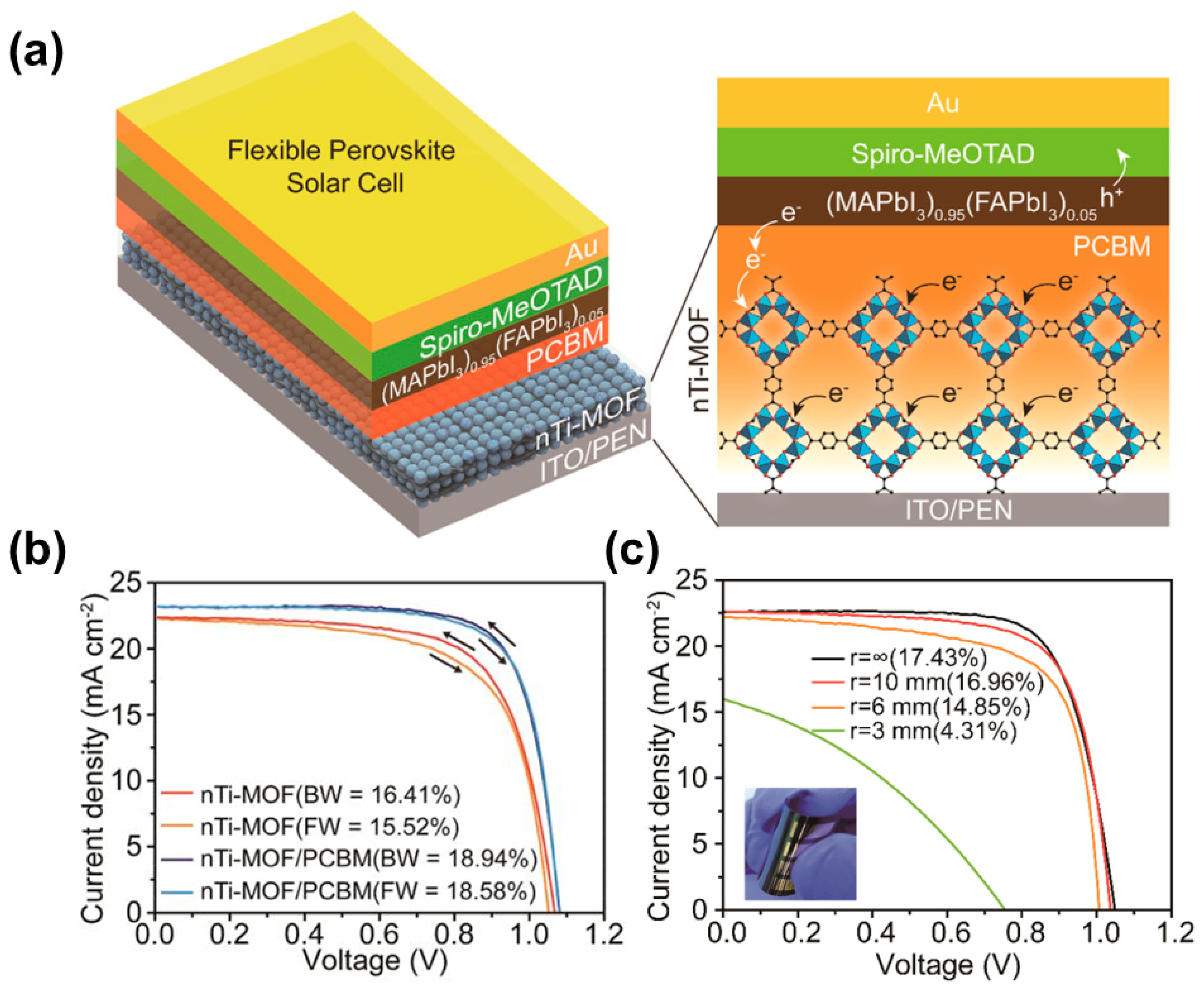

4.2. MOFs as charge transfer layers

5. Conclusion and outlook

- (1)

- The durability of solar cells is a critical factor in evaluating industrial application possibilities. Future research should periodically examine the applications of MOFs in PSCs under extreme conditions, e.g. high humidity.

- (2)

- Poor electron conductivity is one of the most significant barriers to MOF utilization in solar cells. This might be enhanced by rationally designing and manufacturing novelty kinds of MOFs. Combination MOFs with highly conductive materials or the development of conductive MOFs provide possible solutions for increasing the electrical conductivity of MOFs, allowing for their use in solar cells.

- (3)

- Metal compounds originating from MOFs are a novel selection that can potentially increase solar cell efficiency. Although these compounds lose the natural features of MOFs, their charge transport behavior may be enhanced. Furthermore, these materials often preserve adequate porosity and have a large surface area, implying a wide range of solar applications.

- (4)

- A thorough knowledge of the links between MOFs' architectures, characteristics, and solar cell efficiency is required. This may allow for the development of more expected MOFs for photovoltaic utilization. Further research into the uses of 2-dimensional MOFs could provide potential results in solar cells.

References

- Wang, P.; Teng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Bao, W.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, H. Review on the synergistic effect between metal–organic frameworks and gas hydrates for CH4 storage and CO2 separation applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 167, 112807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jung, H.S.; Lee, J.W.; Kang, Y.T. Review on applications of metal–organic frameworks for CO2 capture and the performance enhancement mechanisms. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 162, 112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsaei, M.; Akhbari, K.; White, J. Modulating Carbon Dioxide Storage by Facile Synthesis of Nanoporous Pillared-Layered Metal–Organic Framework with Different Synthetic Routes. Inorganic Chemistry 2022, 61, 3893–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.; Zhao, J.; Xue, Y.; Yang, R.; Pang, H. Synergistic effect of Co/Ni bimetallic metal–organic nanostructures for enhanced electrochemical energy storage. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 628, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Hussain, I.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, W. Strategies for improving the photocatalytic performance of metal-organic frameworks for CO2 reduction: A review. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2023, 125, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Ajiwokewu, B.; Bankole, A.A.; Ismail, O.; Al-Amodi, H.; Kumar, N. MOF based composites with engineering aspects and morphological developments for photocatalytic CO2 reduction and hydrogen production: A comprehensive review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 109408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Yu, H.; Shi, J.; Li, B.; Wu, L.; Wang, M. Dislocated Bilayer MOF Enables High-Selectivity Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to CO. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2209814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Barman, S.; Rahimi, F.A.; Biswas, S.; Nath, S.; Maji, T.K. Developing post-modified Ce-MOF as a photocatalyst: A detail mechanistic insight into CO2 reduction toward selective C2 product formation. Energy & Environmental Science 2023, 16, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-J.; Jiang, Z.-W.; Hsu, S.-W. Investigation of the Performance of Heterogeneous MOF-Silver Nanocube Nanocomposites as CO2 Reduction Photocatalysts by In Situ Raman Spectroscopy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15, 6716–6725. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, H.R.; Hanif, A.; Keshavarz, A.; Shang, J.; Iglauer, S. CO2, CH4, and H2 Adsorption Performance of the Metal–Organic Framework HKUST-1 by Modified Synthesis Strategies. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 7260–7267. [Google Scholar]

- Isikgor, F.H.; Zhumagali, S.T.; Merino, L.V.; De Bastiani, M.; McCulloch, I.; De Wolf, S. Molecular engineering of contact interfaces for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Nature Reviews Materials 2023, 8, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bati, A.S.; Zhong, Y.L.; Burn, P.L.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Shaw, P.E.; Batmunkh, M. Next-generation applications for integrated perovskite solar cells. Communications Materials 2023, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.; Hossain, M.K.; Pandey, R.; Madan, J.; Samajdar, D.; Rahman, M.F.; Ansari, M.Z.; Amami, M. Perovskite solar cells with dual light absorber layers for performance efficiency exceeding 30%. Energy & Fuels 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J. A critical review of research progress for metal alloy materials in hydrogen evolution and oxygen evolution reaction. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 11302–11320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra, N.; Agrawal, P.; Pathak, S.; Saini, R.; Sharma, S. Hydrothermally synthesized MoSe2/ZnO composite with enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huang, L.-a.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Shen, S.; Zhong, W.; Pan, J. Phosphorus-modified cobalt single-atom catalysts loaded on crosslinked carbon nanosheets for efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 3550–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, W.; Liao, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Comprehensive overview of polyoxometalates for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2023, 482, 215058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, K.H. Adjusting oxygen vacancies in perovskite LaCoO3 by electrochemical activation to enhance the hydrogen evolution reaction activity in alkaline condition. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2023, 76, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, F.; Feng, L. Recent Advances in Co-Based Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Small 2023, 2302866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Gondal, M.; Hassan, M.; Khan, A.; Surrati, A.; Almessiere, M. Exceptional co-catalysts free SrTiO3 perovskite coupled CdSe nanohybrid catalyst by green pulsed laser ablation for electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2022, 11, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Uddin, A. Progress in stability of organic solar cells. Advanced Science 2020, 7, 1903259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.; Wang, J.-L. Machine learning for high performance organic solar cells: current scenario and future prospects. Energy & environmental science 2021, 14, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Jinnai, S.; Ie, Y. Nonfullerene acceptors for P3HT-based organic solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2021, 9, 18857–18886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, G.; Yu, L.; Li, R.; Peng, Q. P3HT-based polymer solar cells with 8.25% efficiency enabled by a matched molecular acceptor and smart green-solvent processing technology. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1906045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosekar, I.C.; Patil, G.C. Review on performance analysis of P3HT: PCBM-based bulk heterojunction organic solar cells. Semiconductor Science and Technology 2021, 36, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Do, H.H.; Van Nguyen, T.; Singh, P.; Raizada, P.; Sharma, A.; Sana, S.S.; Grace, A.N.; Shokouhimehr, M.; Ahn, S.H. Perovskite oxide-based photocatalysts for solar-driven hydrogen production: Progress and perspectives. Solar Energy 2020, 211, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labed, M.; Sengouga, N.; Meftah, A.; Meftah, A.; Rim, Y.S. Study on the improvement of the open-circuit voltage of NiOx/Si heterojunction solar cell. Optical Materials 2021, 120, 111453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Park, I.J.; Lee, M.G.; Kwon, K.C.; Hong, S.-P.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.A.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, C.; Moon, C.W. Water splitting exceeding 17% solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency using solution-processed Ni-based electrocatalysts and perovskite/Si tandem solar cell. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11, 33835–33843. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Walter, D.; Wu, Y.; Fong, K.C.; Jacobs, D.A.; Duong, T.; Peng, J.; Weber, K.; White, T.P.; Catchpole, K.R. Monolithic perovskite/Si tandem solar cells: pathways to over 30% efficiency. Advanced energy materials 2020, 10, 1902840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.U.; Jung, E.D.; Noh, Y.W.; Seo, S.K.; Choi, Y.; Park, H.; Song, M.H.; Choi, K.J. Strategy for large-scale monolithic Perovskite/Silicon tandem solar cell: A review of recent progress. EcoMat 2021, 3, e12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, P.; Peng, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Surve, S.; Lu, T.; Bui, A.D.; Li, N.; Liang, W. 27.6% Perovskite/c-Si Tandem Solar Cells Using Industrial Fabricated TOPCon Device. Advanced Energy Materials 2022, 12, 2200821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yang, Z.; Jia, Q.; Ball, R.J.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, Y. Emerging applications of metal-organic frameworks and derivatives in solar cells: Recent advances and challenges. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2023, 152, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueh, C.-C.; Chen, C.-I.; Su, Y.-A.; Konnerth, H.; Gu, Y.-J.; Kung, C.-W.; Wu, K.C.-W. Harnessing MOF materials in photovoltaic devices: recent advances, challenges, and perspectives. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7, 17079–17095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.Y.; Do, H.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Metal-organic framework materials for perovskite solar cells. Polymers 2020, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, H.H.; Cho, J.H.; Han, S.M.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Metal–Organic-Framework-and MXene-Based Taste Sensors and Glucose Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, H.H.; Tekalgne, M.A.; Tran, V.A.; Van Le, Q.; Cho, J.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. MOF-derived Co/Co3O4/C hollow structural composite as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Fuel 2022, 329, 125468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.H.; Nguyen, T.H.C.; Van Nguyen, T.; Xia, C.; Nguyen, D.L.T.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Metal-organic-framework based catalyst for hydrogen production: Progress and perspectives. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 37552–37568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.H.; Tekalgne, M.A.; Le, Q.V.; Cho, J.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Hollow Ni/NiO/C composite derived from metal-organic frameworks as a high-efficiency electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Convergence 2023, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.H.; Kim, H.; Hong, C.S. MOF-74 type variants for CO2 capture. Materials Chemistry Frontiers 2021, 5, 5172–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, R.B.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Liang, B.; Yildirim, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Chen, B. Optimization of the pore structures of MOFs for record high hydrogen volumetric working capacity. Advanced materials 2020, 32, 1907995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, H.W.; Koo, S.-J.; Lee, D.; Cho, E.; Kim, Y.-K.; Shin, M.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, H.J.; Song, M. High efficiency and stable solid-state fiber dye-sensitized solar cells obtained using TiO2 photoanodes enhanced with metal organic frameworks. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2022, 67, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavian, R.; Mirzaei, M.; Alizadeh, H. Current status and future prospects of metal–organic frameworks at the interface of dye-sensitized solar cells. Dalton Transactions 2020, 49, 13936–13947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasubbu, V.; Kumar, P.R.; Mothi, E.M.; Karuppasamy, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Maiyalagan, T.; Shajan, X.S. Highly interconnected porous TiO2-Ni-MOF composite aerogel photoanodes for high power conversion efficiency in quasi-solid dye-sensitized solar cells. Applied Surface Science 2019, 496, 143646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Zhu, C.; Wang, H.; Han, Y.; Ma, S.; Niu, X.; Li, N.; Shi, C.; Qiu, Z.; Zhou, H. Synergistic effects of Eu-MOF on perovskite solar cells with improved stability. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhou, X.; Ge, C.; Lin, H.; Satapathi, S.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, H. Advance and prospect of metal-organic frameworks for perovskite photovoltaic devices. Organic Electronics 2022, 106, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llabrés i Xamena, F.X.; Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Applications for metal− organic frameworks (MOFs) as quantum dot semiconductors. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2007, 111, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Lim, I.; Shin, C.Y.; Patil, S.A.; Lee, W.; Shrestha, N.K.; Lee, J.K.; Han, S.-H. Facile interfacial charge transfer across hole doped cobalt-based MOFs/TiO2 nano-hybrids making MOFs light harvesting active layers in solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3, 22669–22676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerke, E.D.; Small, L.J.; Foster, M.E.; Wheeler, J.; Ullman, A.M.; Stavila, V.; Rodriguez, M.; Allendorf, M.D. MOF-sensitized solar cells enabled by a pillared porphyrin framework. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 4816–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pang, A.; Wang, C.; Wei, M. Metal–organic frameworks: promising materials for improving the open circuit voltage of dye-sensitized solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2011, 21, 17259–17264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Xiang, W.; Wang, T.; Gu, S.; Zhao, X. Enhance photovoltaic performance of tris (2, 2′-bipyridine) cobalt (II)/(III) based dye-sensitized solar cells via modifying TiO2 surface with metal-organic frameworks. Solar Energy 2017, 147, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Fu, L. Metal organic frameworks derived high-performance photoanodes for DSSCs. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 825, 154089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, W. ZIF-8 and three-dimensional graphene network assisted DSSCs with high performances. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2021, 296, 121992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.R.; Ramasubbu, V.; Shajan, X.S.; Mothi, E. Porphyrin-sensitized quasi-solid solar cells with MOF composited titania aerogel photoanodes. Materials Today Energy 2020, 18, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-Y.; Huang, Y.-J.; Li, C.-T.; Kung, C.-W.; Vittal, R.; Ho, K.-C. Metal-organic framework/sulfonated polythiophene on carbon cloth as a flexible counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Energy 2017, 32, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.S.; Xiang, W.; Amiinu, I.S.; Zhao, X. Zeolitic-imidazolate-framework (ZIF-8)/PEDOT: PSS composite counter electrode for low cost and efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 17303–17310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.-N.; Lin, J.T.; Li, C.-T. Electroactive and sustainable Cu-MoF/PEDOT composite electrocatalysts for multiple redox mediators and for high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 8435–8444. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.-B.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Chen, S.-M.; Gu, Z.-G.; Zhang, J. Epitaxial growth of highly transparent metal–porphyrin framework thin films for efficient bifacial dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 12, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, D.; Pang, A.; Li, Y.; Dou, J.; Wei, M. Metal–organic frameworks at interfaces of hybrid perovskite solar cells for enhanced photovoltaic properties. Chemical communications 2018, 54, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian-Yazdi, M.-R.; Gholampour, N.; Eslamian, M. Interface engineering by employing zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) as the only scaffold in the architecture of perovskite solar cells. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2020, 3, 3134–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Ding, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Rui, Y. Confinement of MACl guest in 2D ZIF-8 triggers interface and bulk passivation for efficient and UV-stable perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2023, 11, 6730–6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, U.; Jee, S.; Park, J.-S.; Han, I.K.; Lee, J.H.; Park, M.; Choi, K.M. Nanocrystalline titanium metal–organic frameworks for highly efficient and flexible perovskite solar cells. ACS nano 2018, 12, 4968–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.M.H.; Bark, C.W. Synthesis of cobalt-doped TiO2 based on metal–organic frameworks as an effective electron transport material in perovskite solar cells. ACS omega 2020, 5, 2280–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, V.A.G.; Martínez, W.O.H.; Redondo, F.; Guerrero, N.B.C.; Roncaroli, F.; Perez, M.D. Fe and Ti metal-organic frameworks: Towards tailored materials for photovoltaic applications. Applied Materials Today 2021, 22, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Jiang, A.; Xia, D.; Du, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, P.; Fan, R.; Yang, Y. Metal organic framework doped Spiro-OMeTAD with increased conductivity for improving perovskite solar cell performance. Solar Energy 2019, 188, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Gai, S.; Dong, Y.; Qiu, L.; Xia, D.; Fan, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, B. New insight into the Lewis basic sites in metal–organic framework-doped hole transport materials for efficient and stable Perovskite solar cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 5235–5244. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).