Submitted:

24 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Functional Annotation of DEGs

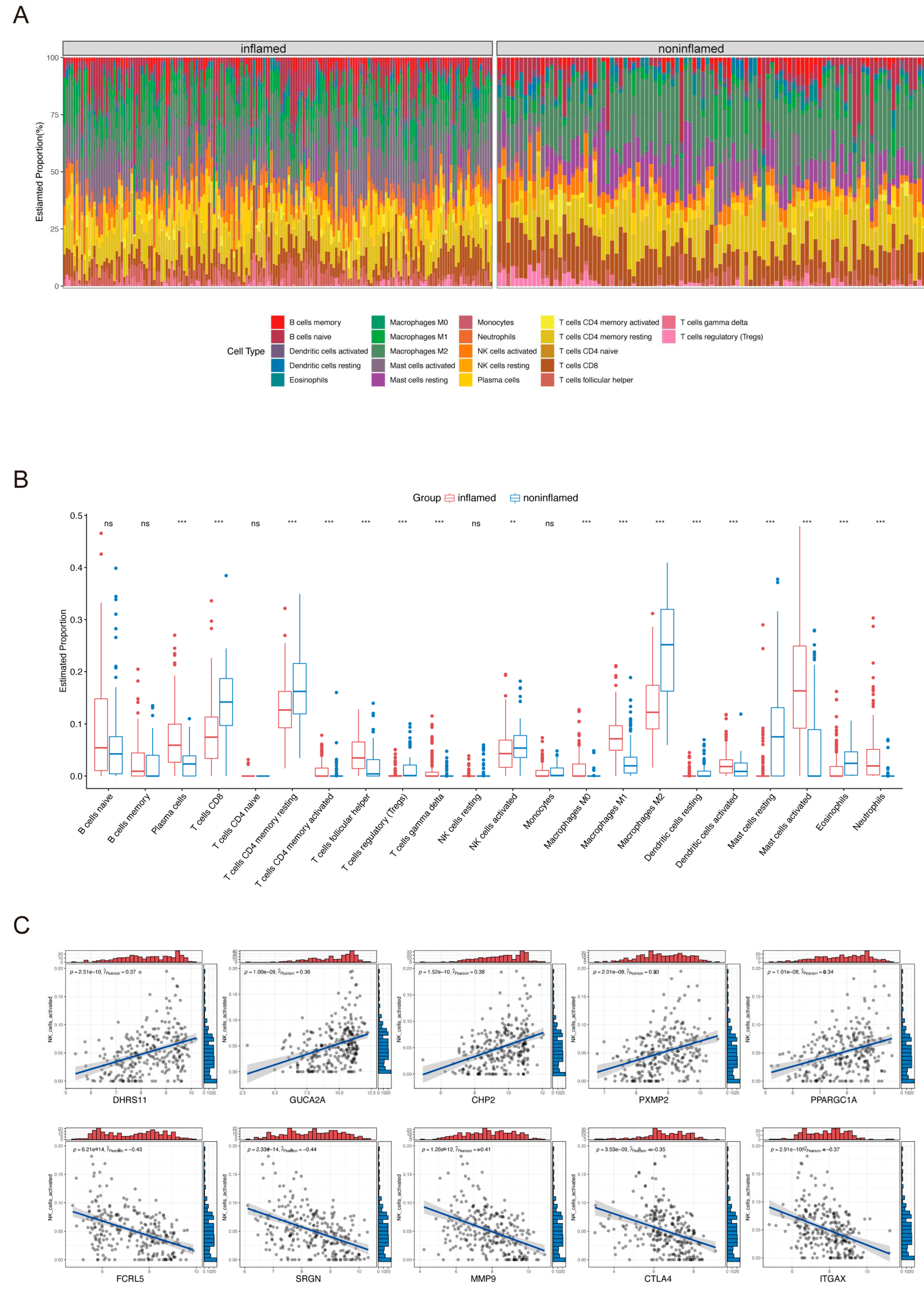

2.2. Immune Cell Infiltration in UC Tissues and Identification of ANAGs

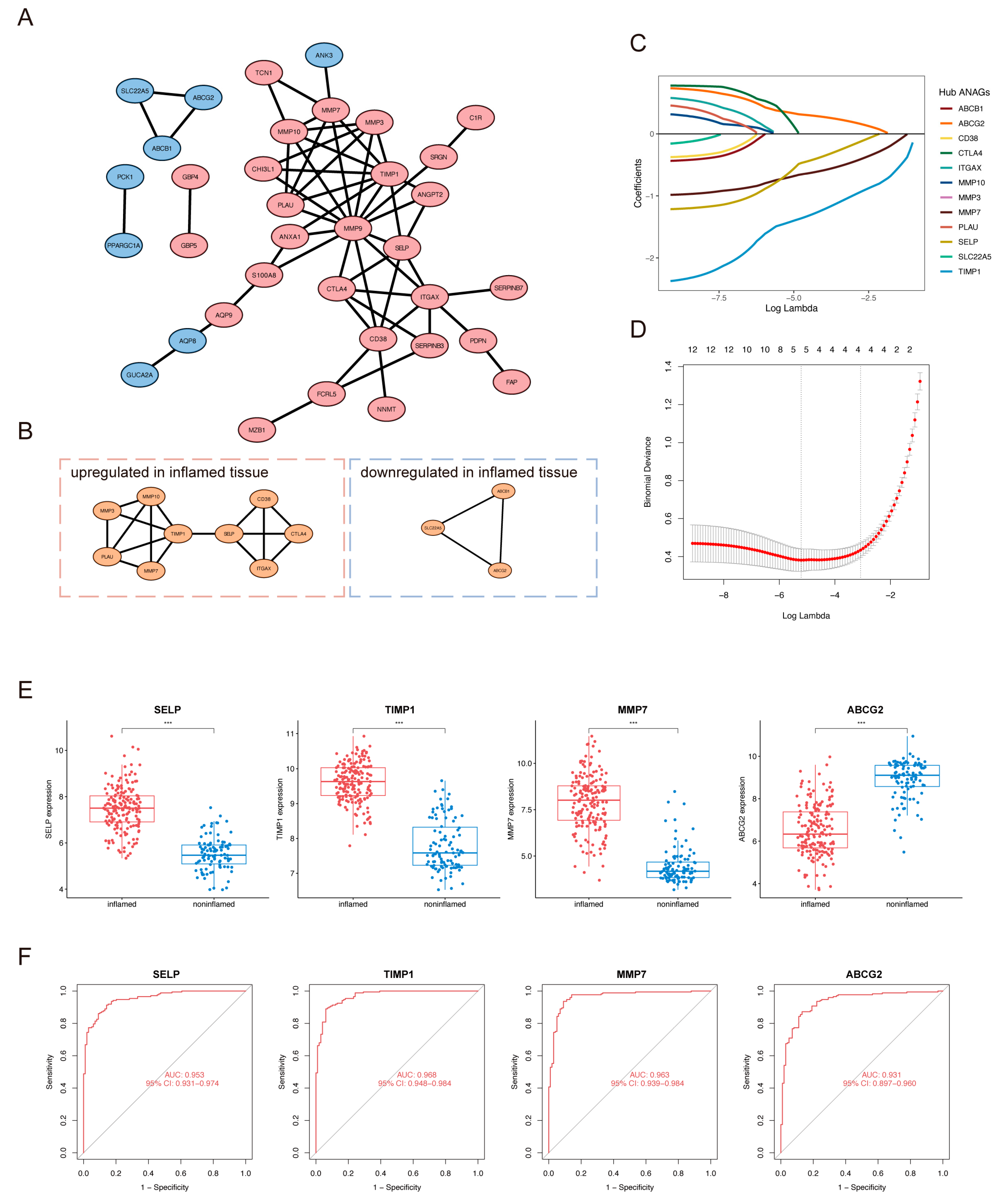

2.3. Identification of Hub ANAGs and Generation of ANAG Score

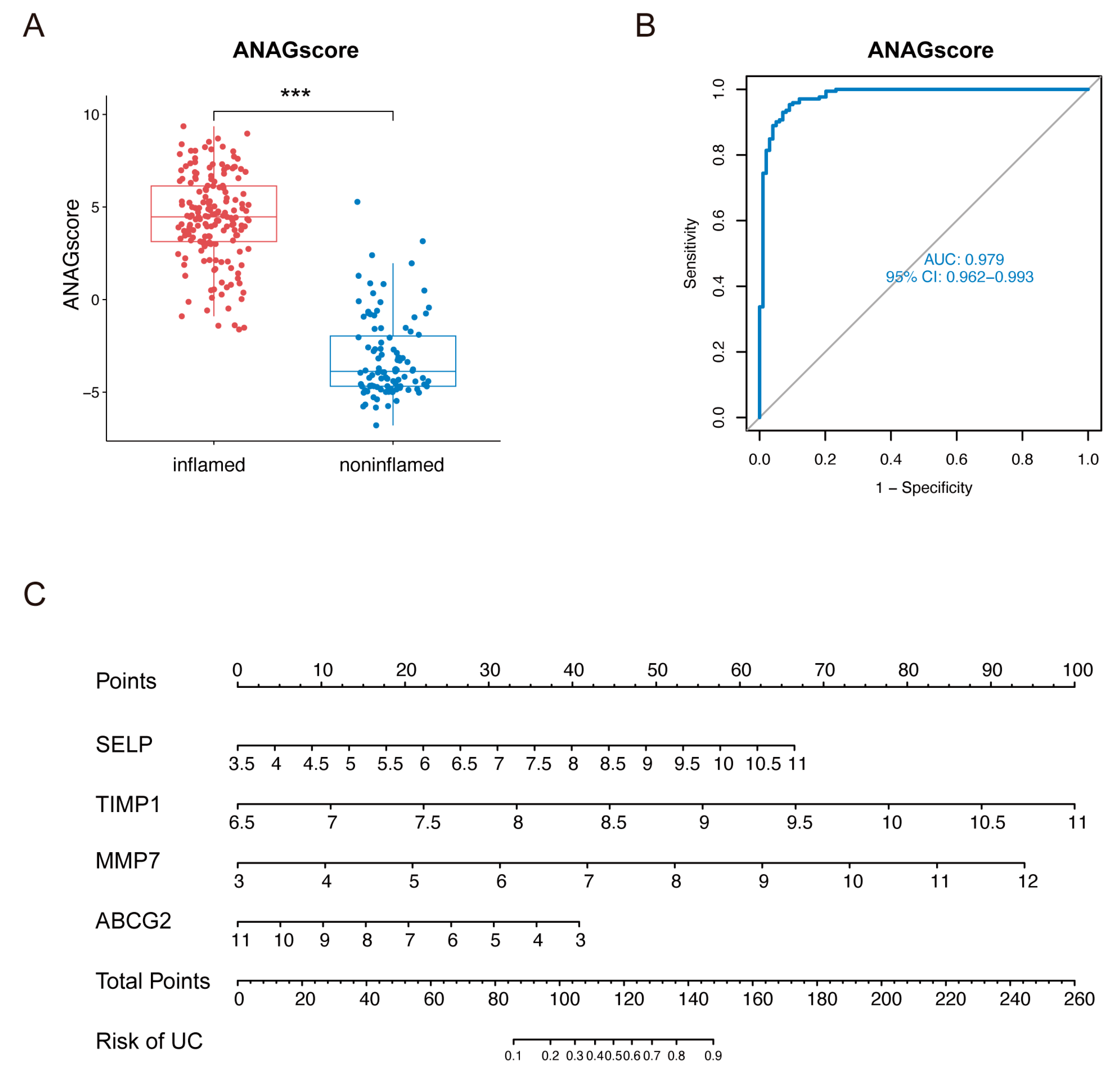

2.4. Diagnostic Value of the ANAG Score

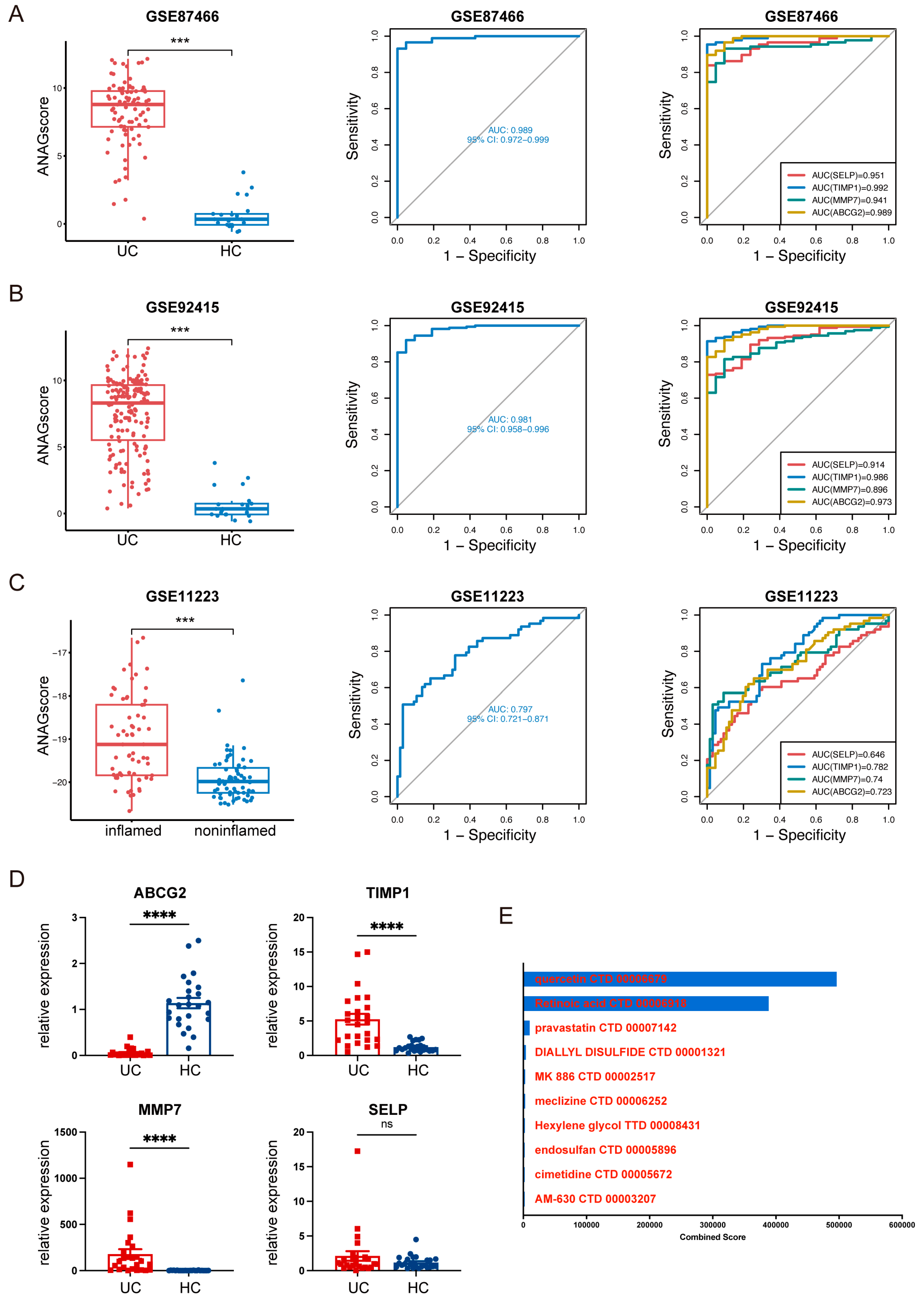

2.5. Validation of ANAGs, ANAG Score, and Prediction of Drugs

2.6. ScRNA-Seq Analysis Evaluated Gene Expression and Cell Scores Based on the ANAGs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Public Data Collection

4.2. Screening of DEGs

4.3. Immune Infiltration Analysis

4.4. Screening of Activated NK-Associated Genes (ANAGs)

4.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.6. Identification of Hub ANAGs

4.7. Generation and Validation of the ANAG Score

4.8. Clinical Specimens

4.9. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

4.10. Potential Therapeutic Drug Prediction

4.11. ScRNA-Seq Data Processing

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ungaro, R.; Mehandru, S.; Allen, P. B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Colombel, J.-F. Ulcerative Colitis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1756–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Siegmund, B.; Le Berre, C.; Wei, S. C.; Ferrante, M.; Shen, B.; Bernstein, C. N.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Hibi, T. Ulcerative Colitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2020, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burisch, J.; Ungaro, R.; Vind, I.; Prosberg, M. V.; Bendtsen, F.; Colombel, J. F.; Vester-Andersen, M. K. Proximal Disease Extension in Patients with Limited Ulcerative Colitis: A Danish Populationbased Inception Cohort. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, A. W.; Mela, C. M.; Lindsay, J. O.; Gazzard, B. G.; Goodier, M. R. Increased Proportion of CD16+ NK Cells in the Colonic Lamina Propria of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients, but Not after Azathioprine Treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S. C.; Plamondon, S.; Al-Hassi, H. O.; English, N.; Gellatly, N.; Kamm, M. A.; Knight, S. C.; Stagg, A. J. A Novel Population of Human CD56+ Human Leucocyte Antigen D-Related (HLA-DR+) Colonic Lamina Propria Cells Is Associated with Inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis: ORIGINAL ARTICLE. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 158, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulthess, J.; Meresse, B.; Ramiro-Puig, E.; Montcuquet, N.; Darche, S.; Bègue, B.; Ruemmele, F.; Combadière, C.; Di Santo, J. P.; Buzoni-Gatel, D.; Cerf-Bensussan, N. Interleukin-15-Dependent NKp46 + Innate Lymphoid Cells Control Intestinal Inflammation by Recruiting Inflammatory Monocytes. Immunity 2012, 37, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamoto, M.; Ueno, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Onitake, T.; Hanaoka, R.; Yoshioka, K.; Hatakeyama, T.; Chayama, K. Selective Decrease in Colonic CD56 + T and CD161 + T Cells in the Inflamed Mucosa of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L. J.; Murphy, C. T.; Quinlan, A.; Hurley, G.; Shanahan, F.; Nally, K.; Melgar, S. Natural Killer Cells Protect Mice from DSS-Induced Colitis by Regulating Neutrophil Function via the NKG2A Receptor. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, A.; Aslani, S.; Mostafaei, S.; Rezaei, N.; Mahmoudi, M. The Role of Killer-Cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR) Genes in Susceptibility to Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 67, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yadav, P. K.; Chen, C. Potential Role of NK Cells in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, A.; Benelli, R.; Venè, R.; Costa, D.; Ferrari, N.; Tosetti, F.; Zocchi, M. R. Human Gut-Associated Natural Killer Cells in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D. C.; Edgar, R. S.; Ahmad, T.; Cummings, J. R. F.; Jewell, D. P.; Trowsdale, J.; Young, N. T. Killer Ig-like Receptor (KIR) Genotype and HLA Ligand Combinations in Ulcerative Colitis Susceptibility. Genes Immun. 2006, 7, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Peng, P. L.; Lin, X.; Chang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, R.; Nie, J. Y.; Dong, W. G.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J. Regulatory Role of NKG2D+ NK Cells in Intestinal Lamina Propria by Secreting Double-Edged Th1 Cytokines in Ulcerative Colitis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 98945–98952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusung, S.; McGovern, D.; Lin, L.; Hommes, D.; Lagishetty, V.; Braun, J. NK Cells Are Biologic and Biochemical Targets of 6-Mercaptopurine in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 175, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestweber, D.; Blanks, J. E. Mechanisms That Regulate the Function of the Selectins and Their Ligands. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furie, B.; Furie, B. C. Role of Platelet P-Selectin and Microparticle PSGL-1 in Thrombus Formation. Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Geng, J. G. P-Selectin Mediates Adhesion of Leukocytes, Platelets, and Cancer Cells in Inflammation, Thrombosis, and Cancer Growth and Metastasis. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz). 2006, 54, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, W. E.; Wilson, R. W.; Ballantyne, C. M.; Beaudet, A. L. Molecular Cloning and Analysis of in Vivo Expression of Murine P-Selectin. Blood 1992, 80, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, A.; Isenmann, S.; Vestweber, D. Cloning of the Mouse Endothelial Selectins. Expression of Both E- and P- Selectin Is Inducible by Tumor Necrosis Factor α. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 15176–15183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahne, M.; Jäger, U.; Isenmann, S.; Hallmann, R.; Vestweber, D. Five Tumor Necrosis Factor-Inducible Cell Adhesion Mechanisms on the Surface of Mouse Endothelioma Cells Mediate the Binding of Leukocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 121, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrisian, L. M. The Matrix-Degrading Metalloproteinases. BioEssays 1992, 14, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marônek, M.; Marafini, I.; Gardlík, R.; Link, R.; Troncone, E.; Monteleone, G. Metalloproteinases in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, K.; Hattori, Y.; Umenishi, F.; Yasumitsu, H.; Umeda, M. Purification and Characterization of Extracellular Matrix-Degrading Metalloproteinase, Matrin (Pump-1), Secreted from Human Rectal Carcinoma Cell Line. Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 7758–7764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C. L.; Matrisian, L. M. Matrilysin: An Epithelial Matrix Metalloproteinase with Potentially Novel Functions. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1996, 28, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, T.; Roderfeld, M.; Halwe, J. M.; Tschuschner, A.; Roeb, E.; Graf, J. Cellular Sources of MMP-7, MMP-13 and MMP-28 in Ulcerative Colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkitalo, L.; Kolho, K. L.; Karikoski, R.; Anthoni, H.; Saarialho-Kere, U. Expression Profiles of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Colonic Inflammation Related to Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Lampe, B.; Barthel, B.; Riecken, E. O.; Coupland, S. E.; Rosewicz, S. Differential Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Tissue Inhibitors in Colon Mucosa of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut 2000, 47, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Radomski, M. W. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Intestinal Inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiercinska-Drapalo, A.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Flisiak, R.; Prokopowicz, D. Plasma Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 as Biomarkers of Ulcerative Colitis Activity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 9, 2843–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, M. J. W.; Mieremet-Ooms, M. A. C.; van Hogezand, R. A.; Lamers, C. B. H. W.; Hommes, D. W.; Verspaget, H. W. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase, Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Single Nucleotide Gene Polymorphisms in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 2960–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, M. J.; Mieremet-Ooms, M. A. C.; Sier, C. F. M.; van Hogezand, R. A.; Lamers, C. B. H. W.; Hommes, D. W.; Verspaget, H. W. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Tissue Inhibitors as Prognostic Indicators for Diagnostic and Surgical Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapsoritakis, A. N.; Kapsoritaki, A. I.; Davidi, I. P.; Lotis, V. D.; Manolakis, A. C.; Mylonis, P. I.; Theodoridou, A. T.; Germenis, A. E.; Potamianos, S. P. Imbalance of Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases (TIMP) - 1 and - 4 Serum Levels, in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusano, K.; Miyaura, C.; Inada, M.; Tamura, T.; Ito, A.; Nagase, H.; Kamoi, K.; Suda, T. Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-2, -3, -9, and -13) by Interleukin-1 and Interleukin-6 in Mouse Calvaria: Association of MMP Induction with Bone Resorption*. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarén, P.; Welgus, H. G.; Kovanen, P. T. TNF-Alpha and IL-1beta Selectively Induce Expression of 92-KDa Gelatinase by Human Macrophages. J. Immunol. 1996, 157, 4159–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, G.; Reynolds, J. J.; Werb, Z. Biosynthesis of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases by Human Fibroblasts in Culture. Stimulation by 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol 13-Acetate and Interleukin 1 in Parallel with Collagenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 3079–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotz, M.; Guerne, P. A. Interleukin-6 Induces the Synthesis of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-1/Erythroid Potentiating Activity (TIMP-1/EPA). J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavek, P.; Merino, G.; Wagenaar, E.; Bolscher, E.; Novotna, M.; Jonker, J. W.; Schinkel, A. H. Human Breast Cancer Resistance Protein : Interactions with Steroid Drugs, Hormones, the Dietary Carcinogen Transport of Cimetidine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 312, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J. W.; Buitelaar, M.; Wagenaar, E.; Van der Valk, M. A.; Scheffer, G. L.; Scheper, R. J.; Plösch, T.; Kuipers, F.; Oude Elferink, R. P. J.; Rosing, H.; Beijnen, J. H.; Schinkel, A. H. The Breast Cancer Resistance Protein Protects against a Major Chlorophyll-Derived Dietary Phototoxin and Protoporphyria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 15649–15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herwaarden, A. E.; Jonker, J. W.; Wagenaar, E.; Brinkhuis, R. F.; Schellens, J. H. M.; Beijnen, J. H.; Schinkel, A. H. The Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) Restricts Exposure to the Dietary Carcinogen 2-Amino-1-Methyl-6-Phenylimidazo[4,5-b]Pyridine. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 6447–6452. [Google Scholar]

- van Herwaarden, A. E.; Wagenaar, E.; Karnekamp, B.; Merino, G.; Jonker, J. W.; Schinkel, A. H. Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) Reduces Systemic Exposure of the Dietary Carcinogens Aflatoxin B1, IQ and Trp-P-1 but Also Mediates Their Secretion into Breast Milk. Carcinogenesis 2006, 27, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, B.; Seidel, A.; Lampen, A. Identification of BCRP as Transporter of Benzo[a]Pyrene Conjugates Metabolically Formed in Caco-2 Cells and Its Induction by Ah-Receptor Agonists. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J. W.; Merino, G.; Musters, S.; Van Herwaarden, A. E.; Bolscher, E.; Wagenaar, E.; Mesman, E.; Dale, T. C.; Schinkel, A. H. The Breast Cancer Resistance Protein BCRP (ABCG2) Concentrates Drugs and Carcinogenic Xenotoxins into Milk. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedveld, P.; Zelcer, N.; Pluim, D.; Sönmezer, Ö.; Tibben, M. M.; Beijnen, J. H.; Schinkel, A. H.; Van Tellingen, O.; Borst, P.; Schellens, J. H. M. Mechanism of the Pharmacokinetic Interaction between Methotrexate and Benzimidazoles: Potential Role for Breast Cancer Resistance Protein in Clinical Drug-Drug Interactions. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5804–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, J. W.; Smit, J. W.; Brinkhuis, R. F.; Maliepaard, M.; Beijnen, J. H.; Schellens, J. H. M.; Schinkel, A. H. Role of Breast Cancer Resistance Protein in the Bioavailability and Fetal Penetration of Topotecan. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, G.; Jonker, J. W.; Wagenaar, E.; Van Herwaarden, A. E.; Schinkel, A. H. The Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP/ABCG2) Affects Pharmacokinetics, Hepatobiliary Excretion, and Milk Secretion of the Antibiotic Nitrofurantoin. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaher, H.; Khan, A. A.; Palandra, J.; Brayman, T. G.; Yu, L.; Ware, J. A. Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) Is a Major Determinant of Sulfasalazine Absorption and Elimination in the Mouse. Mol. Pharm. 2006, 3, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuring, J. J.; Peppelenbosch, M. P.; Kuipers, E. J.; Van Der Woude, C. J.; De Haar, C. Impeded Protein Folding and Function in Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, R.; De Coppet, P.; Daly, K.; Bourreille, A.; Cuff, M.; Bonnet, C.; Mosnier, J. F.; Galmiche, J. P.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.; Segain, J. P. Down-Regulation of the Monocarboxylate Transporter 1 Is Involved in Butyrate Deficiency During Intestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 1916–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, H.; Hruz, P.; Zimmermann, C.; Straumann, A.; Terracciano, L.; Hammann, F.; Lehmann, F.; Beglinger, C.; Drewe, J. Breast Cancer Resistance Protein and P-Glycoprotein Expression in Patients with Newly Diagnosed and Therapy-Refractory Ulcerative Colitis Compared with Healthy Controls. Digestion 2008, 78, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, R.; Blachier, F.; Darcy-Vrillon, B.; De Coppet, P.; Bourreille, A.; Segain, J. P. Butyrate Utilization by the Colonic Mucosa in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Transport Deficiency. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuring, J. J.; De Haar, C.; Koelewijn, C. L.; Kuipers, E. J.; Peppelenbosch, M. P.; Van Der Woude, C. J. Absence of ABCG2-Mediated Mucosal Detoxification in Patients with Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Due to Impeded Protein Folding. Biochem. J. 2012, 441, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Picón, E.; Dotti, I.; Corraliza, A. M.; Mayorgas, A.; Esteller, M.; Perales, J. C.; Ricart, E.; Masamunt, M. C.; Carrasco, A.; Tristán, E.; Esteve, M.; Salas, A. Intestinal Inflammation Modulates the Epithelial Response to Butyrate in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englund, G.; Jacobson, A.; Rorsman, F.; Artursson, P.; Kindmark, A.; Rönnblom, A. Efflux Transporters in Ulcerative Colitis: Decreased Expression of BCRP (ABCG2) and Pgp (ABCB1). Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 13, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V. K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B. L.; Gillette, M. A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S. L.; Golub, T. R.; Lander, E. S.; Mesirov, J. P. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindea, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Waldner, M.; Obenauf, A. C.; Angell, H.; Fredriksen, T.; Lafontaine, L.; Berger, A.; Bruneval, P.; Fridman, W. H.; Becker, C.; Pagès, F.; Speicher, M. R.; Trajanoski, Z.; Galon, J. Ô. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Intratumoral Immune Cells Reveal the Immune Landscape in Human Cancer. Immunity 2013, 39, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A. M.; Steen, C. B.; Liu, C. L.; Gentles, A. J.; Chaudhuri, A. A.; Scherer, F.; Khodadoust, M. S.; Esfahani, M. S.; Luca, B. A.; Steiner, D.; Diehn, M.; Alizadeh, A. A. Determining Cell Type Abundance and Expression from Bulk Tissues with Digital Cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L. G.; Han, Y.; He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes among Gene Clusters. Omi. A J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A. L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N. T.; Morris, J. H.; Bork, P.; Jensen, L. J.; Von Mering, C. STRING V11: Protein-Protein Association Networks with Increased Coverage, Supporting Functional Discovery in Genome-Wide Experimental Datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N. S.; Wang, J. T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accession | Platform | Organism | Sample Type & Number | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE107499 | GPL15207 Array | Homo sapiens | 75 UC inflamed colon | Training |

| 44 UC noninflamed colon | ||||

| GSE179285 | GPL6480 Array | Homo sapiens | 23 UC inflamed colon | Training |

| 32 UC noninflamed colon | ||||

| 168 CD | ||||

| 31 Healthy control | ||||

| GSE59071 | GPL6244 Array | Homo sapiens | 74 UC inflamed colon | Training |

| 23 UC noninflamed colon | ||||

| 8 CD | ||||

| 11 Healthy control | ||||

| GSE11223 | GPL1708 Array | Homo sapiens | 63 UC inflamed colon | Validation |

| 66 UC noninflamed colon | ||||

| GSE87466 | GPL13158 Array | Homo sapiens | 87 UC | Validation |

| 21 Healthy control | ||||

| GSE92415 | GPL13158 Array | Homo sapiens | 162 UC | Validation |

| 21 Healthy control |

| Gene | Sequences |

|---|---|

| ACTB | ACAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCC (Forward) |

| GATATCATCATCCATGGTGAGCTGG (Reverse) | |

| SELP | ACTGCCAGAATCGCTACACAG (Forward) |

| CACCCATGTCCATGTCTTATTGT (Reverse) | |

| TIMP1 | CTTCTGCAATTCCGACCTCGT (Forward) |

| ACGCTGGTATAAGGTGGTCTG (Reverse) | |

| MMP7 | GAGTGAGCTACAGTGGGAACA (Forward) |

| CTATGACGCGGGAGTTTAACAT (Reverse) | |

| ABCG2 | ACGAACGGATTAACAGGGTCA (Forward) |

| CTCCAGACACACCACGGAT (Reverse) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).