Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

0. Introduction

1. Technologies for Electrical Energy Storage Systems

1.1. Electrical Energy Storage (EES)Definition

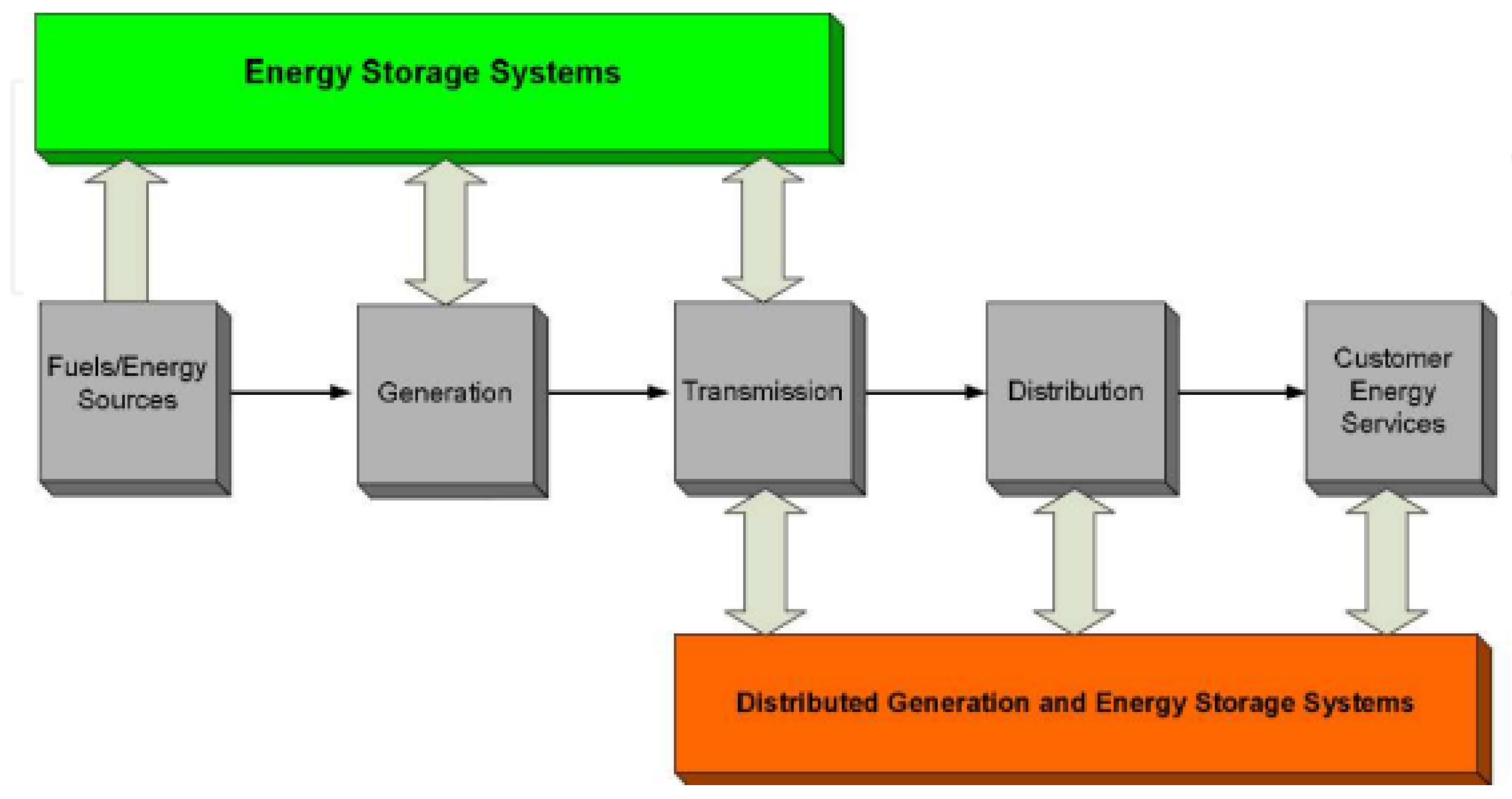

1.2. Principal Role of Energy Storage Systems

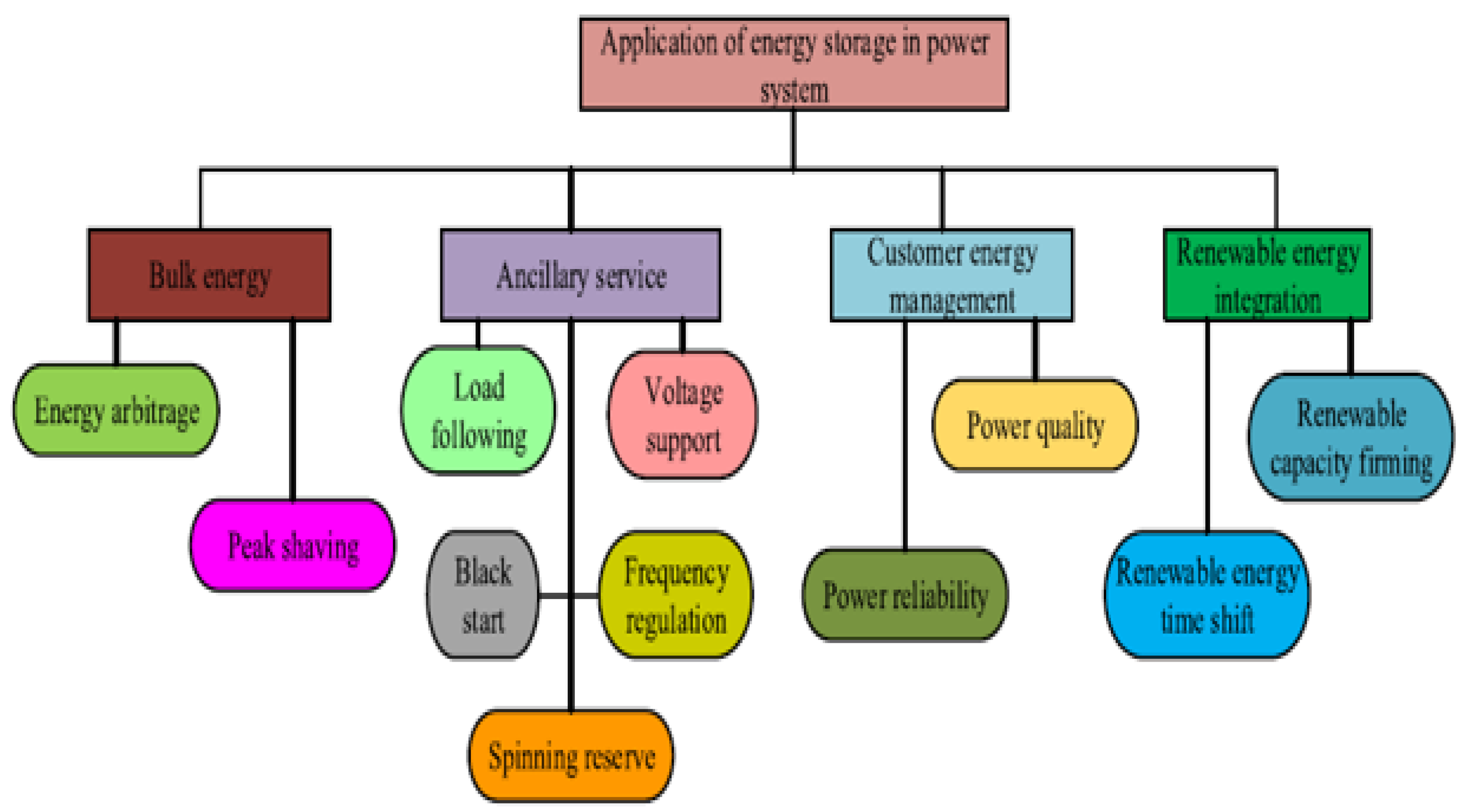

2. Energy Storage Systems Applications and Technical Advantages

- Peak load management and demand response programs.

- Making use of renewable energy sources and reducing their erratic output.

- Offering additional services like voltage stabilization and frequency regulation.

- Microgrids and local energy systems.

- Grid stability and reliability enhancement.

- Backup power and uninterruptible power supply (UPS).

- Management of energy based on time-of-use and energy arbitrage.

- Charging infrastructure for electric vehicles and services for vehicle-to-grid (V2G) interactions.

- Power quality improvement and mitigation of voltage sags and swells.

- Electrification of remote and off-grid areas.

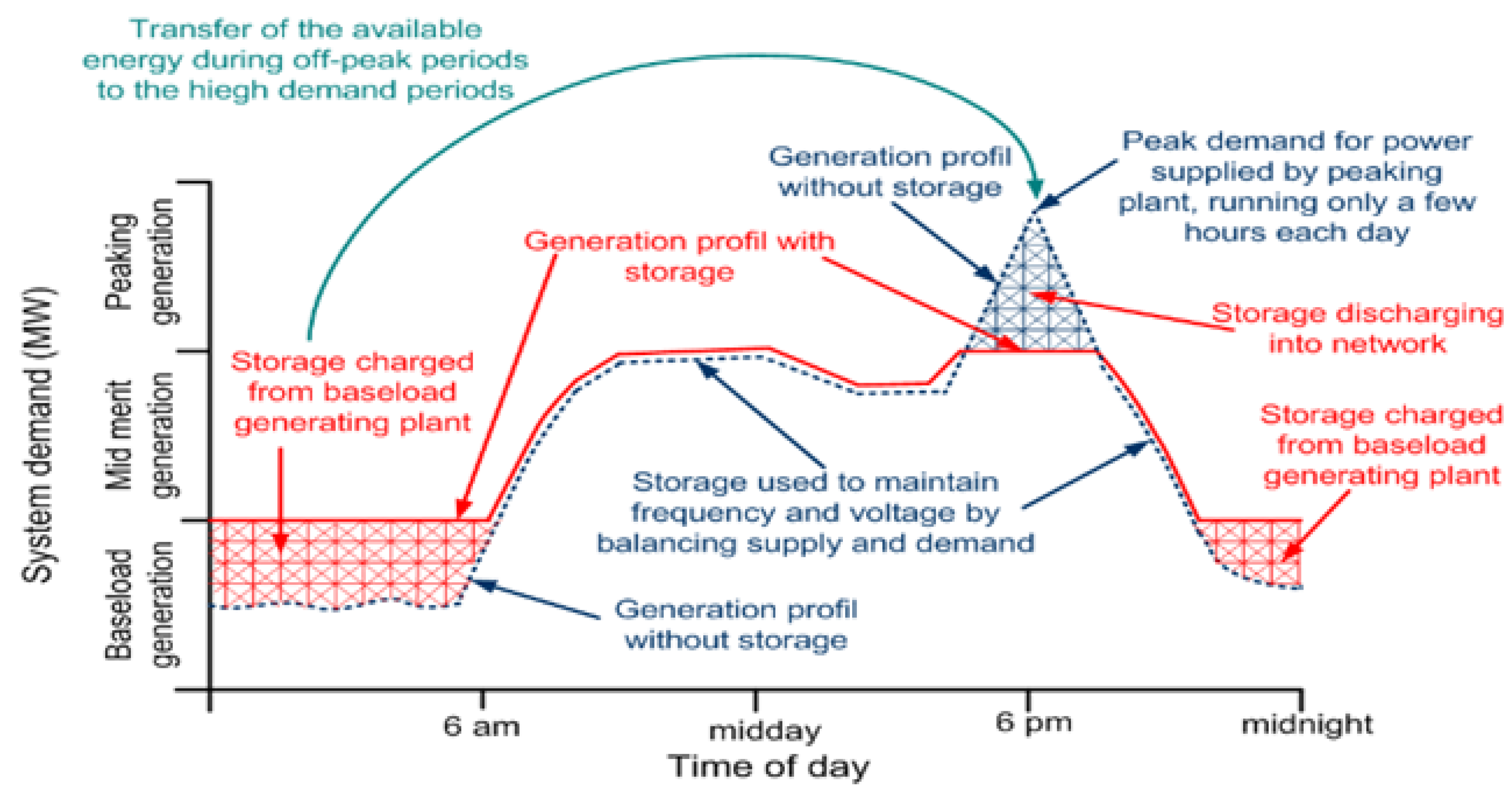

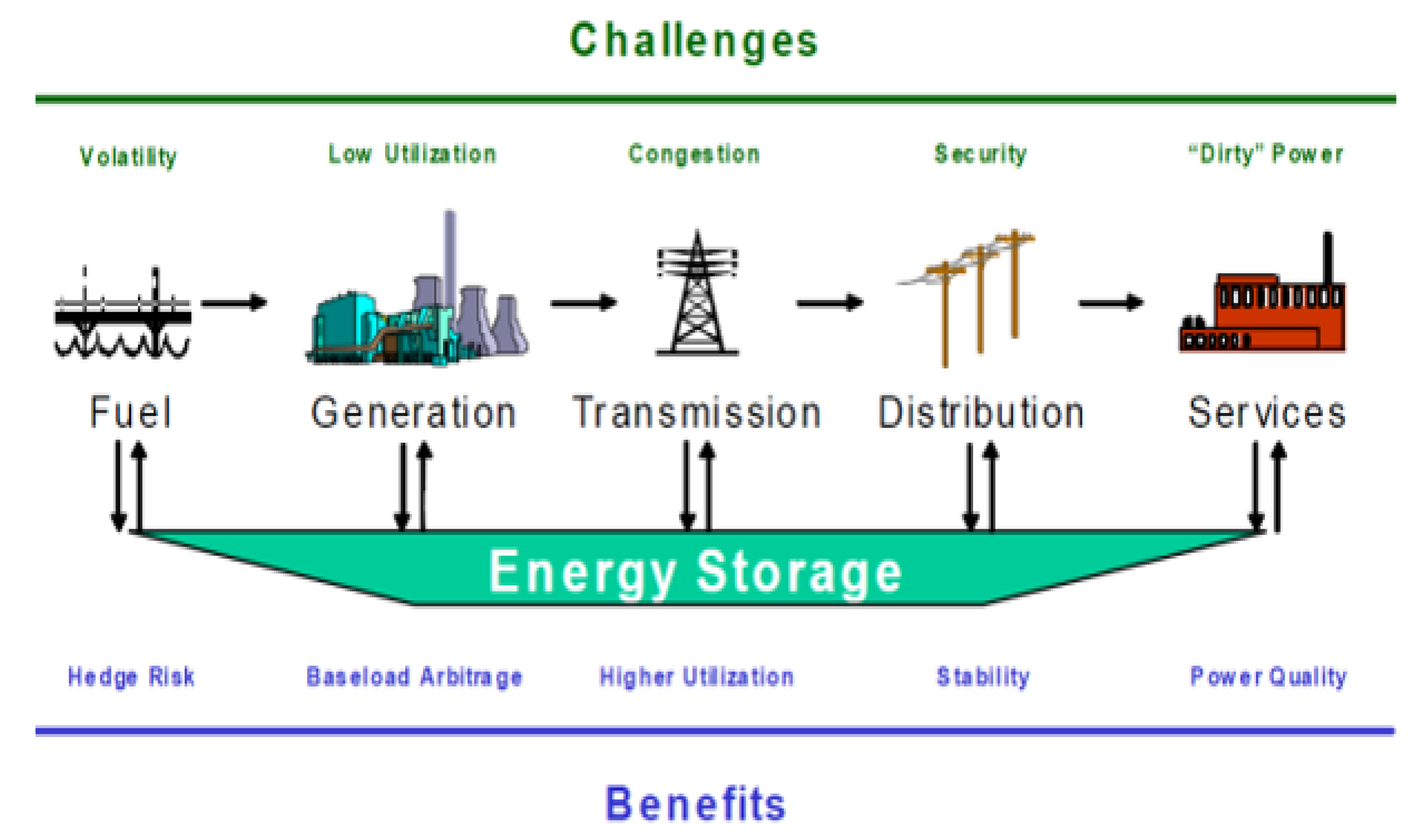

2.1. Generation

- Commodity Storage: In this use, excess energy produced during off-peak times, such the night, is stored for use during the day’s high demand hours.By arbitrating the output price between these two periods, it enables more efficient load factor control for the generation, transmission, and distribution networks, leading to cost savings [29].

- Contingency Service: Contingency reserves are a form of power capacity that can be deployed to meet customer demand in the event of a power facility going offline. Spinning reserves are immediately available, while long-term and non-spinning reserves can be used in as little as 10 minutes.Spinning reserve denotes the generation capacity available to produce active power within a specific timeframe, which hasn’t been allocated for energy production yet. [44].

- Area Control: This application involves preventing unplanned power transfers between different utility systems, maintaining the stability and reliability of the overall grid.

- Grid Frequency Support: In order to prevent sudden imbalances between load and generation and to keep the system’s standard 60Hz/50Hz (cycles per second) In both standard and non-standard grid arrangements, the frequency is in a condition of equilibrium, actual power must be supplied to the electrical distribution grid. Electrical equipment owned by consumers as well as generators may be harmed by abrupt and significant changes in electrical load.

- Black-Start:Black-start capability is the ability of an entity to autonomously commence startup procedures,initiate the transmission system, and aid in the commencement and synchronization of other facilities with the grid. This capability is crucial in restoring power to the grid after a complete blackout or system-wide shut down.

2.2. Distribution and transmission system

- System Stability: This refers to the capability of maintaining synchronous operation among all system components on a transmission line, preventing a collapse or disruption of the entire power system.

- Angular Stability of the Grid: In order to maintain stable and controlled grid functioning, power oscillations brought on by sudden occurrences are reduced through the addition and consumption of active power.

- Grid Voltage Support: In order to keep voltage levels across all power lines within a reasonable range, the electrical distribution system needs to be powered. By achieving a balance between the quantity of actual energy and the level of reactive power generated by generators, the voltage profile of the grid is controlled and stabilized. [45].

- Deferral of Assets: This application centers on postponing the necessity for extra transmission infrastructure by complementing the existing transmission setup. Energy storage systems can potentially increase the effectiveness of current transmission facilities, saving money that would otherwise be needed for capital investments in the construction of new infrastructure that might go unutilized for extended periods of time [44].

2.3. Electrical Energy Management

- Energy Management (Load Leveling / Peak Shaving): Load leveling involves the reorganization of specific loads to reduce electricity demand or store surplus energy when demand is low, subsequently harnessing it during hours of high demand. Peak shaving, on the other hand, comprises cutting back on electricity use during busy times or switching to off-peak hours. Customers can control their energy consumption using these methods, especially to lower time-of-use (demand) charges.

- Unbalanced Load Compensation: Employing four-wire inverters and introducing or absorbing power independently in each phase to supply energy to unbalanced loads enables the correction of unbalanced load conditions. This approach helps maintain balanced operation and supply adequate power to all phases.

- Enhancement of Power Quality: Power quality pertains to variations in voltage, current, and waveform characteristics. Harmonics, power factor, transients, flicker, voltage sags and swells, and voltage spikes can all impact power quality. Distributed Energy Storage Systems (DESS) can adeptly tackle these issues, furnishing customers with dependable electrical service without introducing additional fluctuations or disturbances to the electrical waveform [44].

- Power Reliability: Power reliability is measured by the percentage or ratio of interruptions in the delivery of electric power, which may include instances where power exceeds the threshold, not just complete power outages. DESS can enhance power reliability by providing uninterrupted power supply (UPS) capabilities to "ride-through" power disruptions. When coupled with energy management storage, it enables remote power operations and ensures a reliable power supply [43]. These applications demonstrate how energy storage systems contribute to effective energy management, enhance power quality, and improve the reliability of electrical power supply. They enable load balancing, compensate for unbalanced loads, mitigate power quality issues, and provide backup power during disruptions, thereby ensuring a stable and uninterrupted power supply for consumers.

2.4. Financial benefits of EESS in Power Systems

- Reducing Costs or Boosting Revenue via Bulk Energy Arbitrage: Energy storage makes it possible to purchase electricity at a low cost when there is a drop in demand, allowing for later use or sale when electricity prices are high. This practice results in either cost reductions or increased revenue.

- Cost Avoidance or Revenue Enhancement through Central Generation Capacity: Energy storage can counteract the requirement for new generation capacity by supplying extra power during peak demand intervals. This effectively circumvents the expenses linked to constructing new generation facilities or leasing capacity from the market for wholesale electricity.

- A reduction in costs or an increase in revenue from supplementary services: Energy storage systems have the capability to offer ancillary services like spinning reserve and load following, contributing to the preservation of stability and dependability within the regional grid.

- Cost Avoidance or Revenue Enhancement through Transmission Access/Congestion Mitigation: Energy storage has the potential to improve the efficiency of the Transmission and Distribution (T&D) system by augmenting energy transfer capabilities and stabilizing voltage levels, thereby avoiding transmission access or congestion charges.

- Reduced Demand Charges: Energy storage has the capacity to diminish an end-user’s dependency on the grid when peak demand occurs, resulting in decreased demand charges on their electricity invoices.

- Diminished Financial Impact from Reliability Issues: Energy storage alleviates financial losses linked to power interruptions, especially for commercial and industrial clients that encounter noteworthy economic setbacks during periods of downtime.

- Diminished Financial Impact from Power Quality Issues: Energy storage curtails financial losses arising from power quality irregularities that disrupt loads or damage electrical equipment. By using energy storage, the negative effects of such anomalies can be avoided.

- Enhanced Revenue from Renewable Energy Sources: Energy storage facilitates the temporal adjustment of energy produced by renewable sources. Surplus energy can be stored when demand is low and subsequently utilized when demand aligns with elevated renewable generation output.

3. Energy storage system economic and technical characteristics

3.1. Energy Capacity :

3.2. Power Capacity :

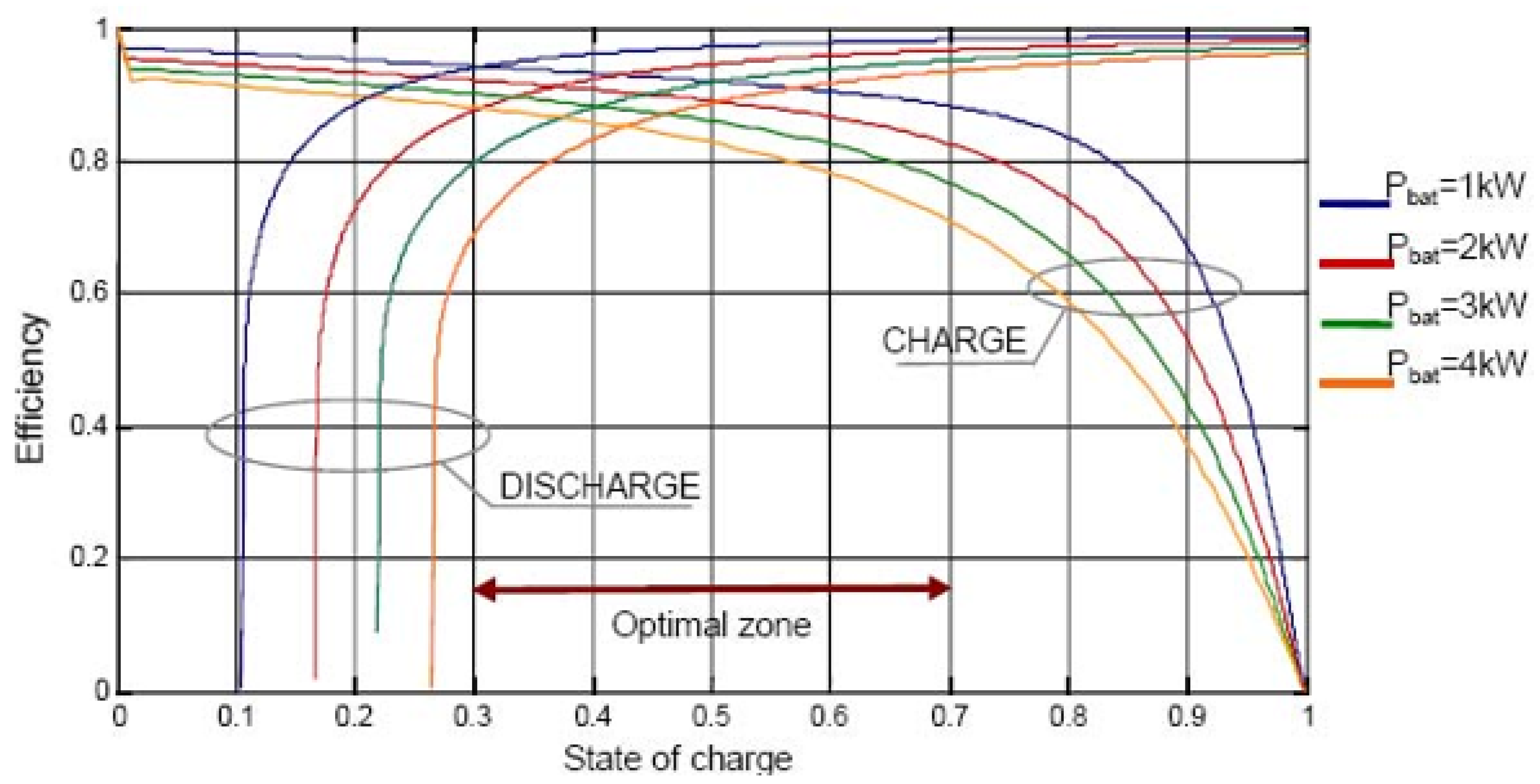

3.3. Efficiency

3.4. Time Response

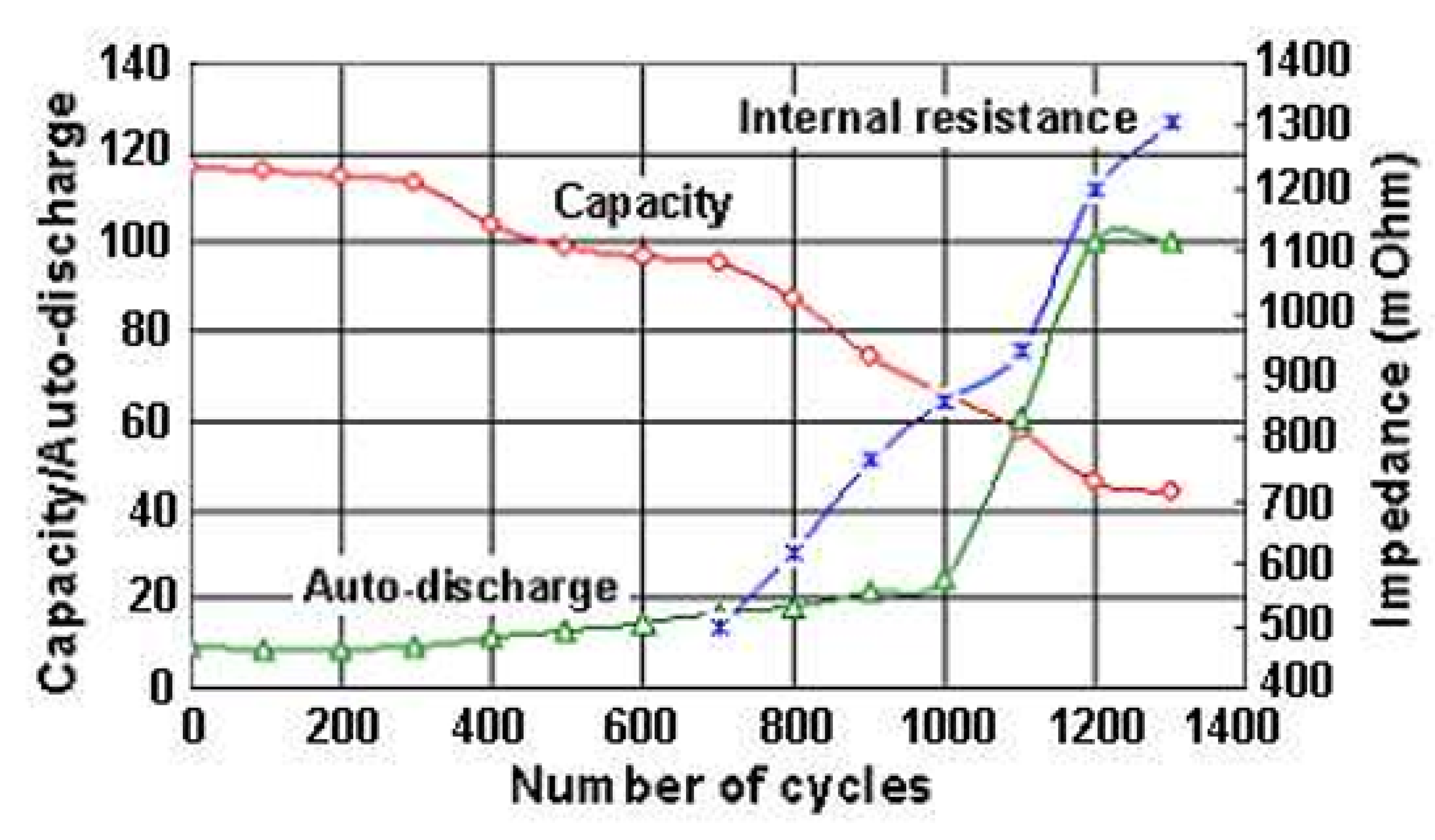

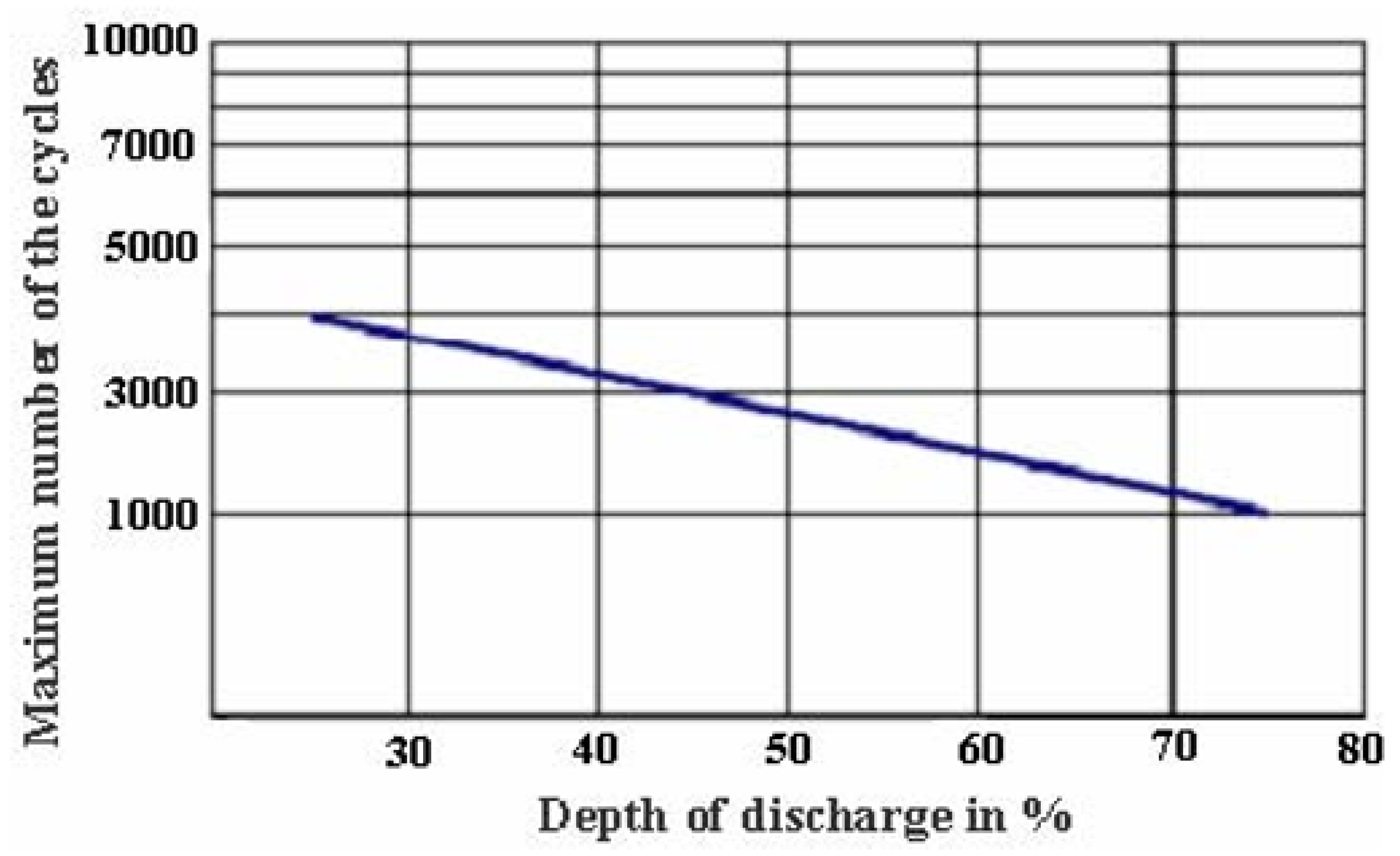

3.5. Life Cycle

3.6. Self-Discharge Rate

3.7. Lifetime and Maintenance Requirements

3.8. Energy Storage Operating Cost

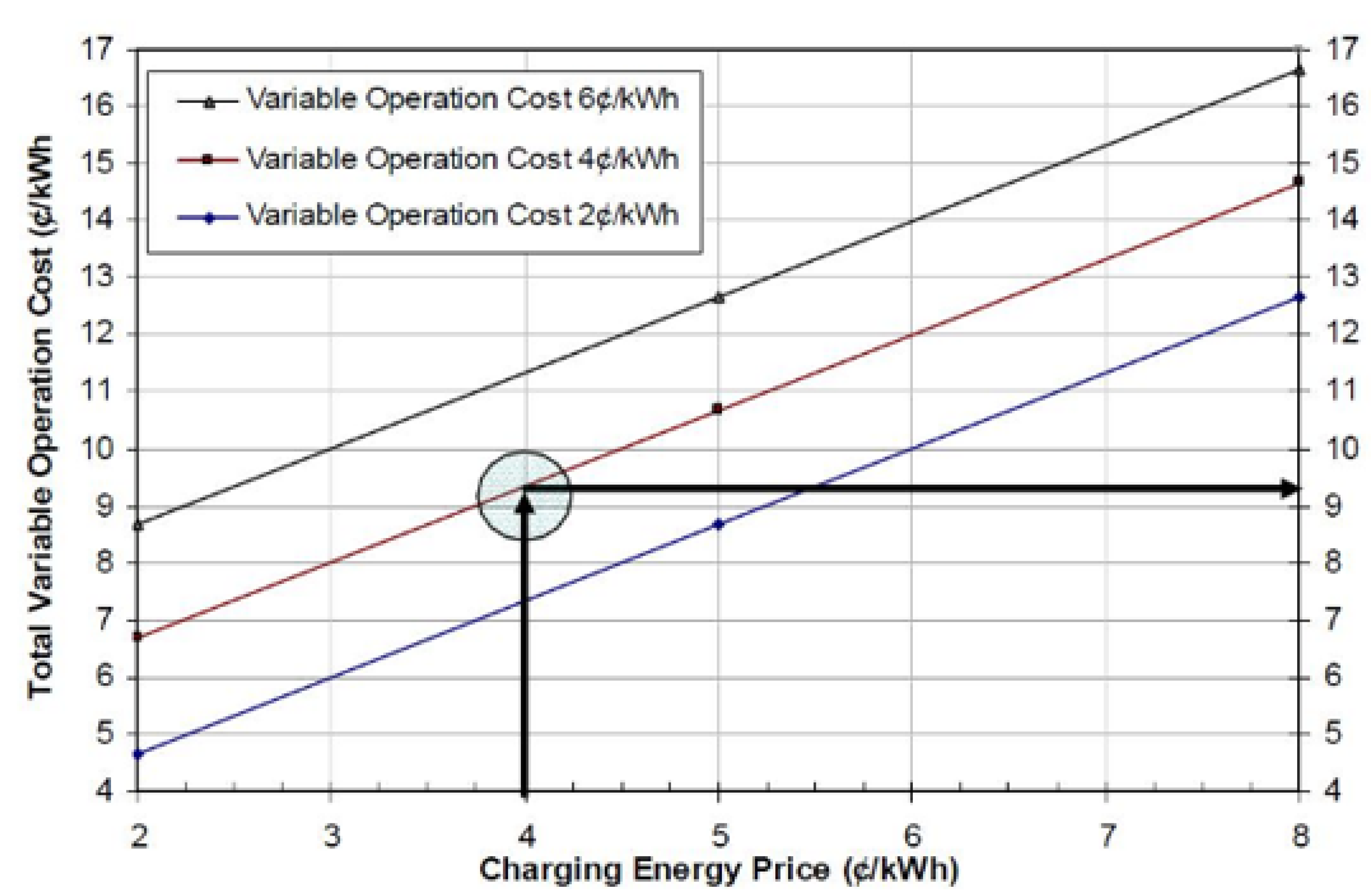

- Energy-related costs associated with charging: The storage system encompass all expenses related to purchasing energy for the purpose of charging, including compensating for energy losses during the round trip.To exemplify, let’s ponder an instance: if a storage system boasts an efficiency of 75% and the rate for energy utilized during charging is 4¢/kWh, the cumulative energy expense for the facility would equate to 5.33¢/kWh. This accounts for the energy input required for charging the storage system and factors in the efficiency losses during the energy transfer process.

- Plant Operation Labor: Depending on the circumstances, labor may be necessary for the operation of a storage plant. While variable labor costs are dependent on the frequency and length of storage usage, fixed labor costs are incurred regardless of the level of storage consumption. While variable labor costs rise proportionately to the level of storage use, fixed labor costs stay constant. Smaller or distributed systems are frequently built for autonomous operation, needing little or no labor,as opposed to larger storage facilities or combined storage capacity. Due to the wide range of possible labor costs associated with different storage types and system sizes, no specific value is assigned to this criterion [47].

- Maintenance Expenses for the Facility: Plant maintenance costs encompass expenditures for scheduled, anticipated, and unexpected repairs and substitutions of machinery, structures, premises, and infrastructure. While variable maintenance expenses correlate with the frequency and extent of storage system utilization, fixed maintenance costs remain consistent irrespective of the degree of storage usage [54].

- Replacement Cost: When a storage system’s estimated lifespan predicts that some parts or subsystems will degrade, a "replacement cost" becomes important. In such cases, a "sinking fund" is established to gather monies for potential replacements in the future. Each unit of energy produced by the storage facility is given a portion of the replacement cost, which is thought of as a variable expense.

- The comprehensive variable operational cost of a storage system encompasses relevant non-energy-related variable operating expenditures, such as labor for plant management, plant energy expenditures (such as charging energy), variable maintenance costs, and replacement costs. The cost-effectiveness of storage is notably impacted by fluctuating operational expenses, which are especially important for applications with heavy demand and numerous charge-discharge cycles.Storage systems should, in ideal circumstances, operate with elevated or exceptionally high efficiency and relatively minimal variable operating expenses. Otherwise, the charges linked to charging and discharging the storage might surpass the advantages. This could pose a substantial obstacle for specific storage types and value propositions. Take, for instance, the illustration presented in Figure 8, showcasing a storage system with a 75% efficiency and an operational cost that is not tied to energy at 4¢/kWh.

3.9. Safety and Environmental Impact

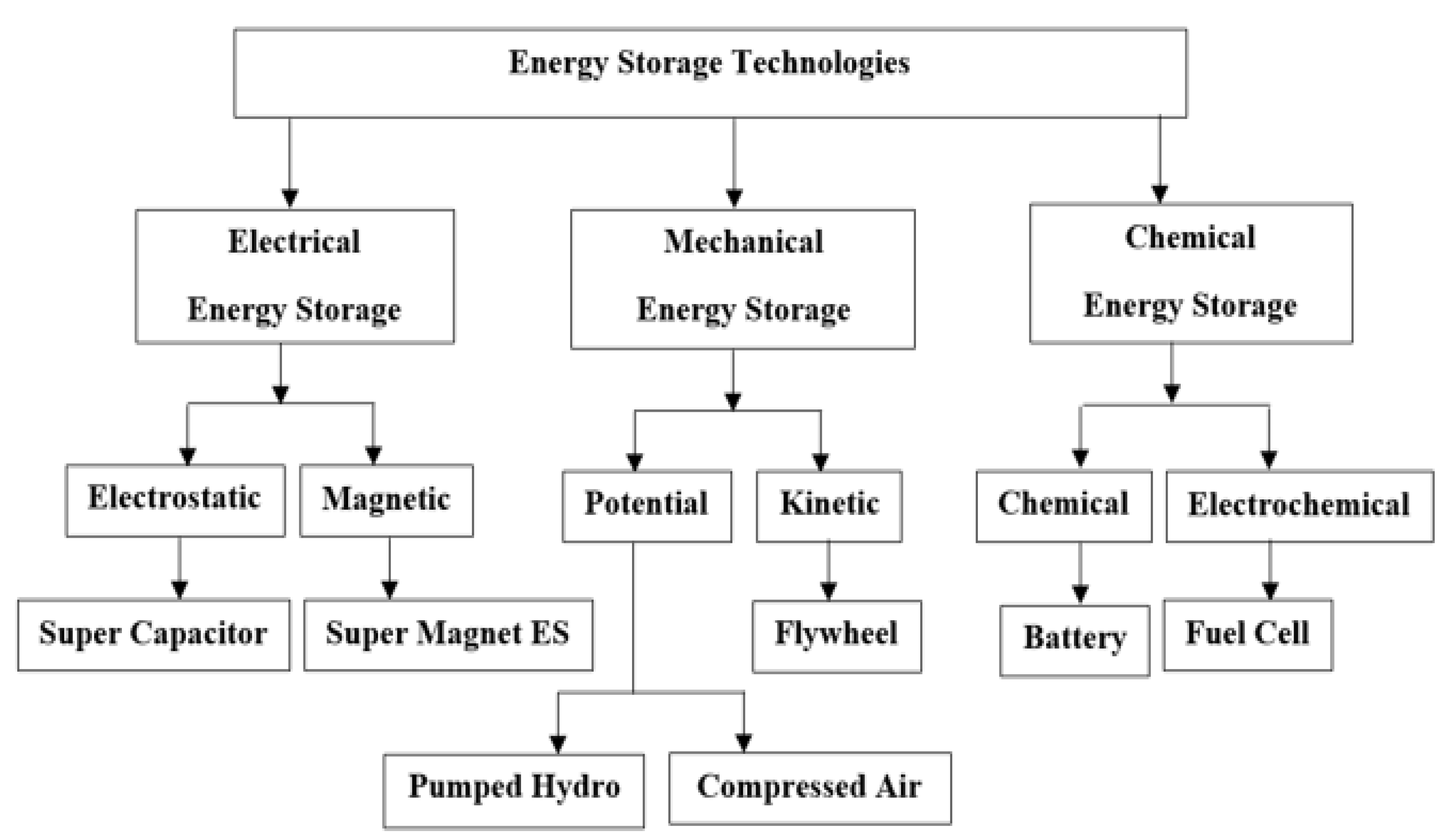

3.10. Classifications of Energy Storage Systems

- Electrical Energy Storage System:(i) Electrostatic Energy Storage System: This category employs capacitors and supercapacitors to create charge separation for the storage of electrical energy.(ii) Magnetic/Current Energy Storage: Within this class, superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES) utilizes high-capacity superconducting magnets and harnesses magnetic fields for energy storage.

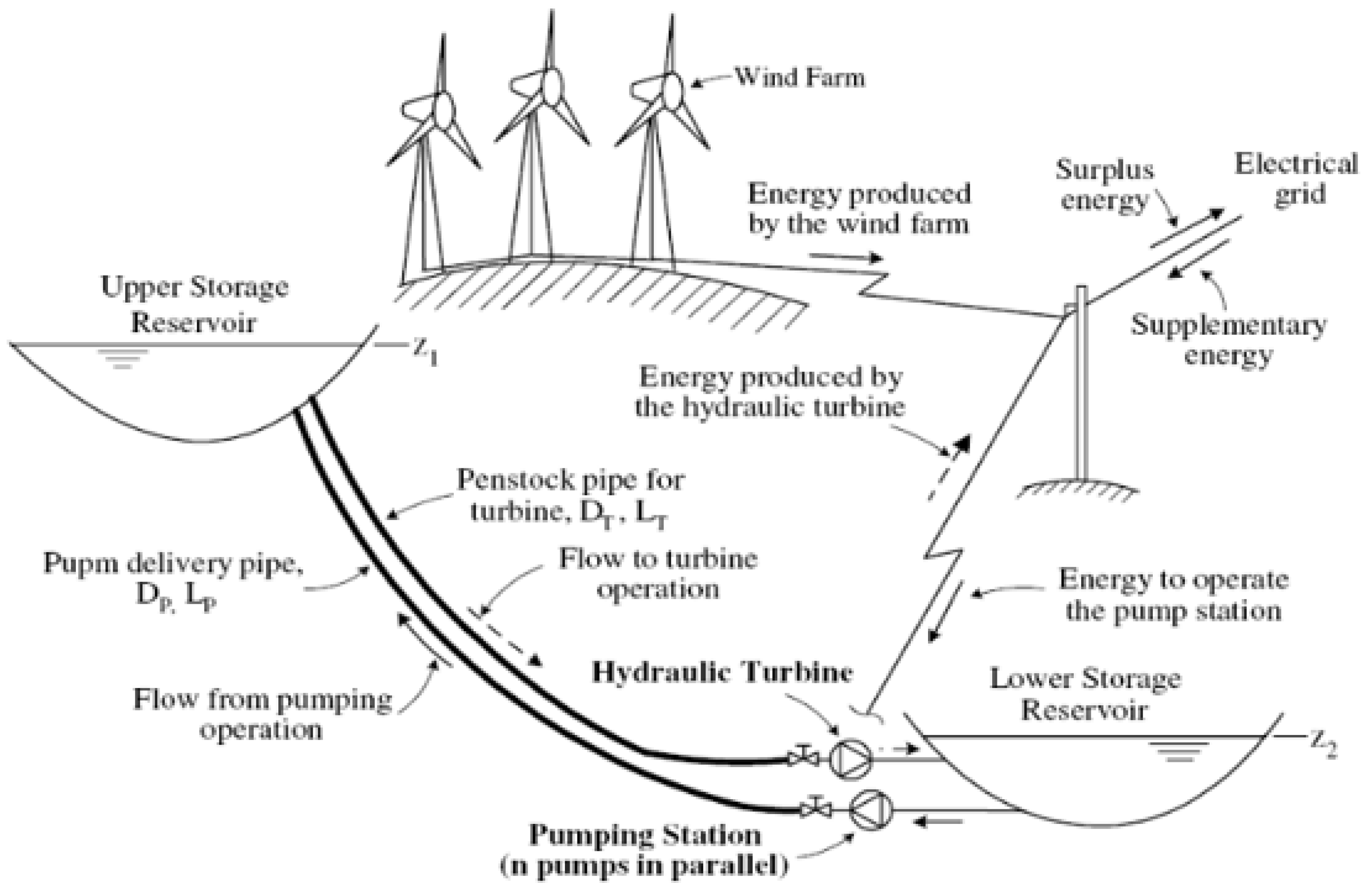

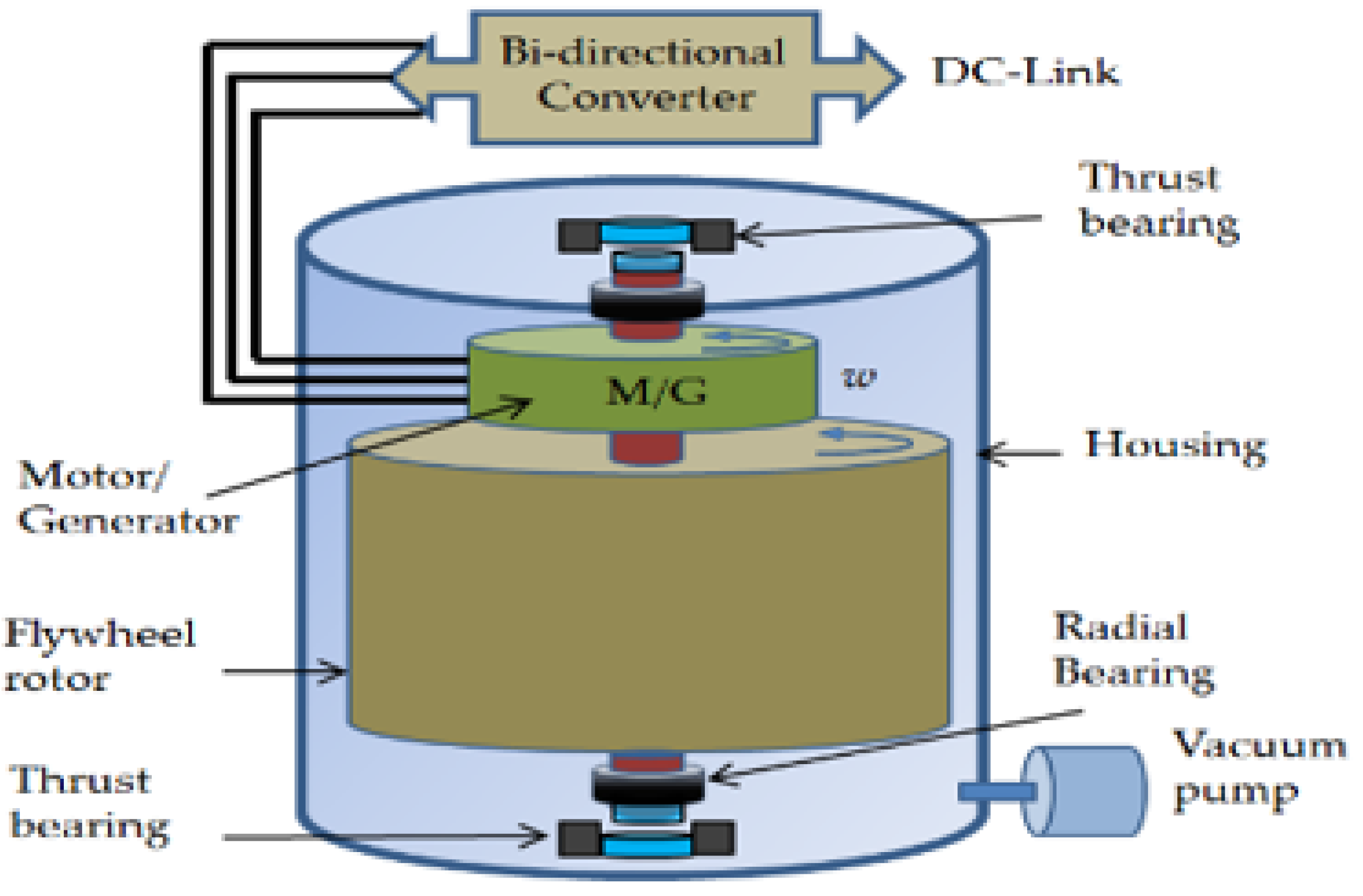

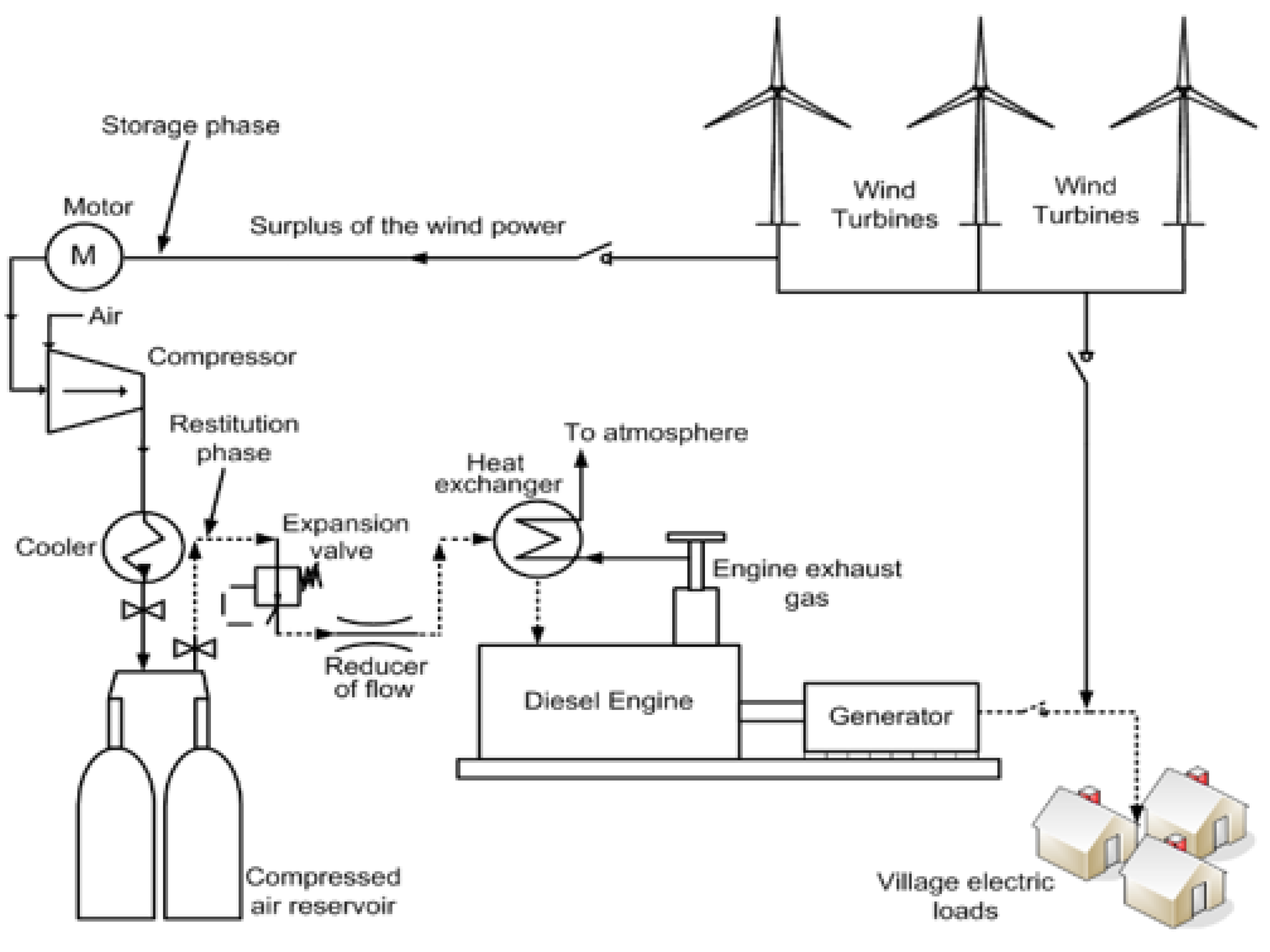

- Mechanical Energy Storage Systems: (i) Kinetic Energy Storage: This category encompasses flywheels, which accumulate energy by spinning a substantial rotor at elevated velocities, capitalizing on rotational kinetic energy. (ii) Potential Energy Storage Systems: Within this group, Pumped Hydro Energy Storage (PHES) and Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES) systems leverage gravitational potential energy and compressed air, respectively, to amass and release energy.

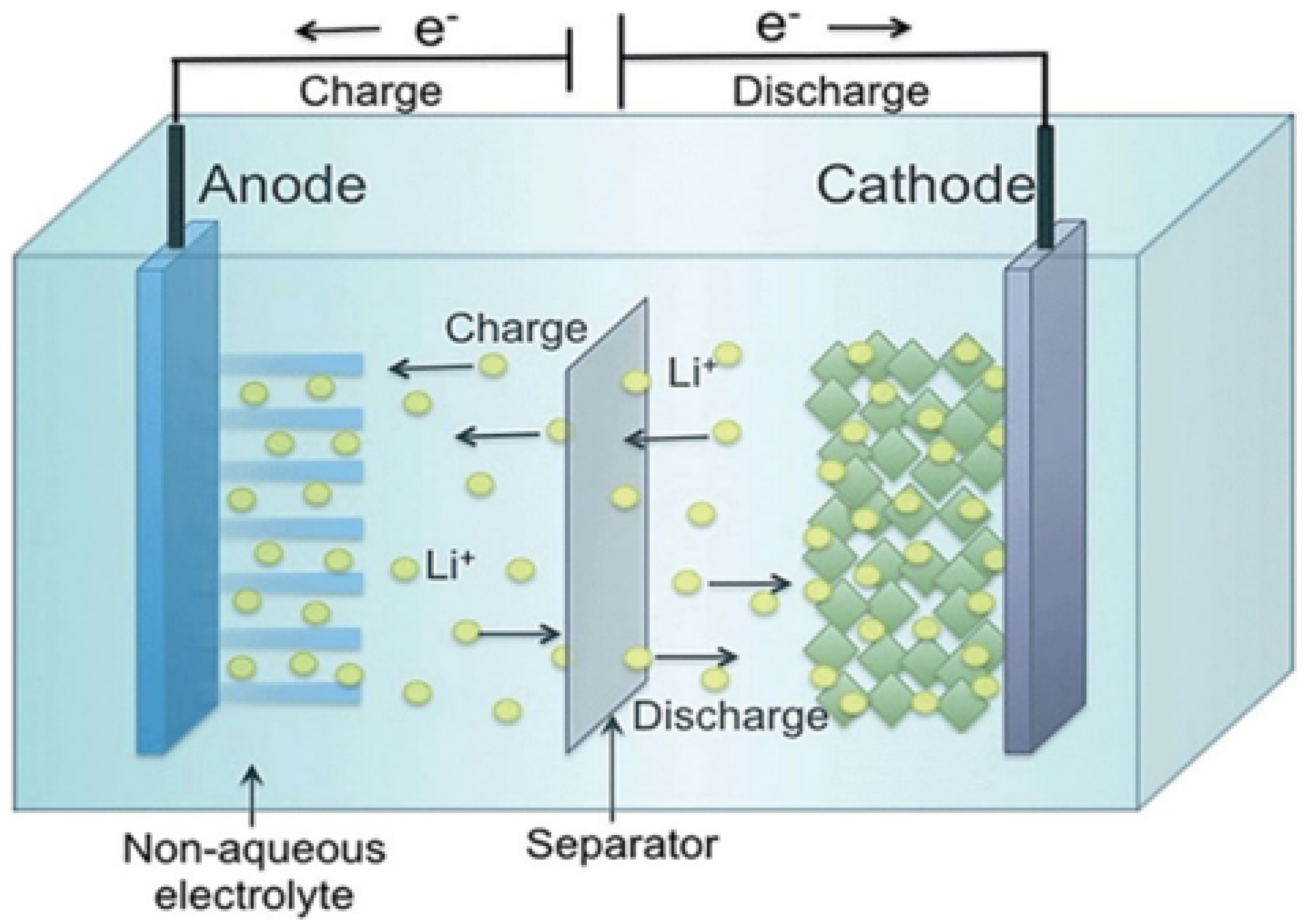

- Chemical Energy Storage Systems: (i) Electrochemical Energy Storage: This category encompasses the utilization of chemical reactions for energy storage in flow-cell batteries such as zinc bromine and vanadium redox systems, as well as conventional batteries such as lead-acid, nickel-metal hydride, and lithium-ion batteries. (ii) Chemical Energy Storage: In this category, Metal-Air Batteries and fuel cells like Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (MCFCs) save energy in the form of chemical molecules that can later be converted back into electricity. (iii) Thermochemical Energy Storage: This category encompasses a range of technologies like solar hydrogen, solar metal, solar ammonia dissociation-recombination, and solar methane dissociation-recombination. These technologies store energy through chemical reactions that are fueled by heat.

- Thermal Energy Storage Systems: (i) Low-Temperature Energy Storage: Cryogenic energy storage systems and aquiferous cold energy storage leverage lower temperatures to store and release energy. (ii) High-Temperature Energy Storage: Thermal energy can be stored for future use using sensible heat systems like steam or hot water accumulators, materials like graphite, hot rocks, and concrete, as well as latent heat systems employing phase transition materials.

4. Technology descriptions for energy storage

4.1. Pumped Hydro Storage Systems (PHSS)

4.2. Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESS)

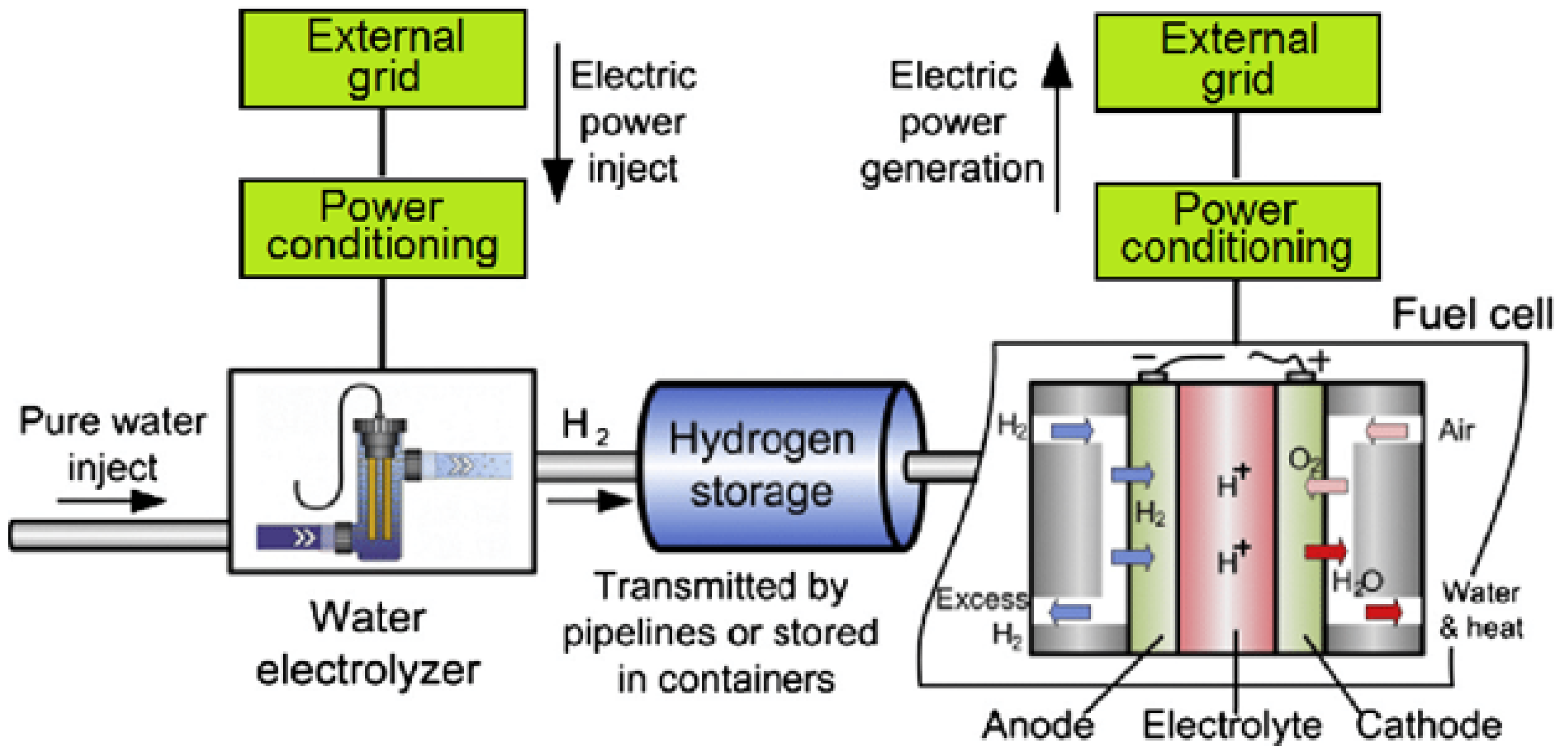

4.3. Fuel cells-Hydrogen energy storage Systems (HESS)

4.4. Thermal energy storage System (TESS)

4.5. Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage Systems (SMESS)

4.6. Supercapacitors Energy Storage System (SESS)

4.7. Batteries Energy Storage System

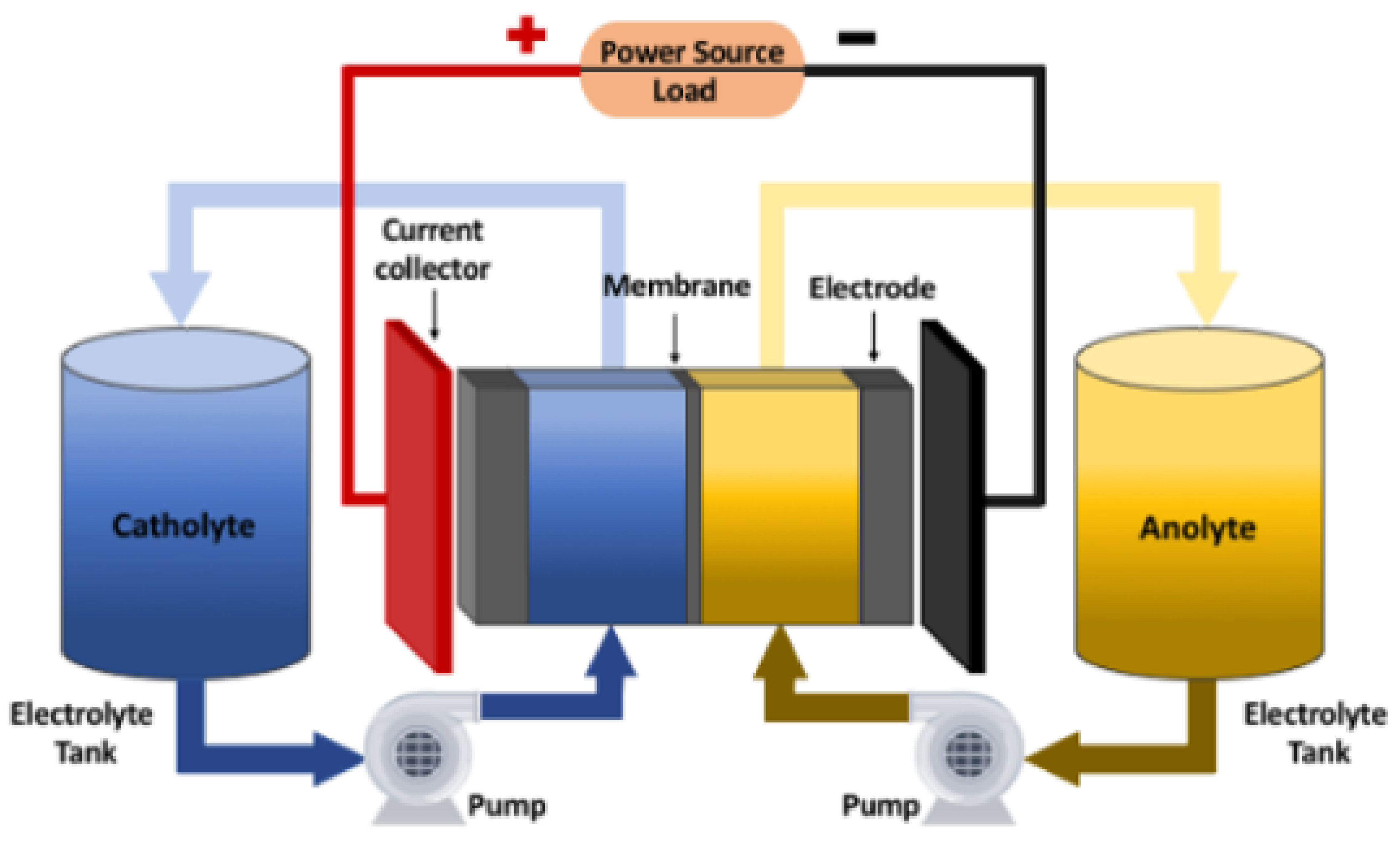

4.8. Flow Batteries Energy Storage System (FBESS)

- Energy capacity and High power .

- Quick recharging by electrolyte replacement.

- Simple electrolyte replacement promotes long life.

- Complete discharge ability.

- The use of non-toxic substances.

- Operation at low temperatures.

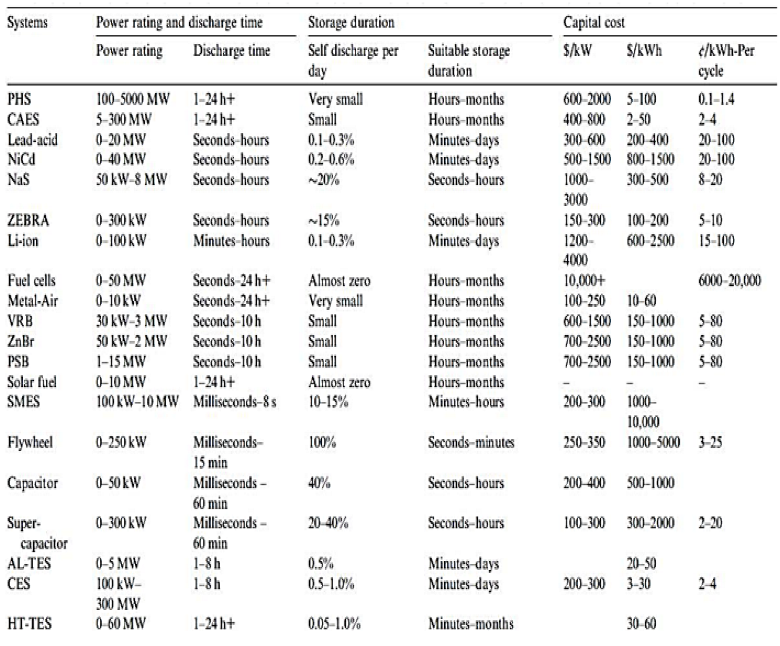

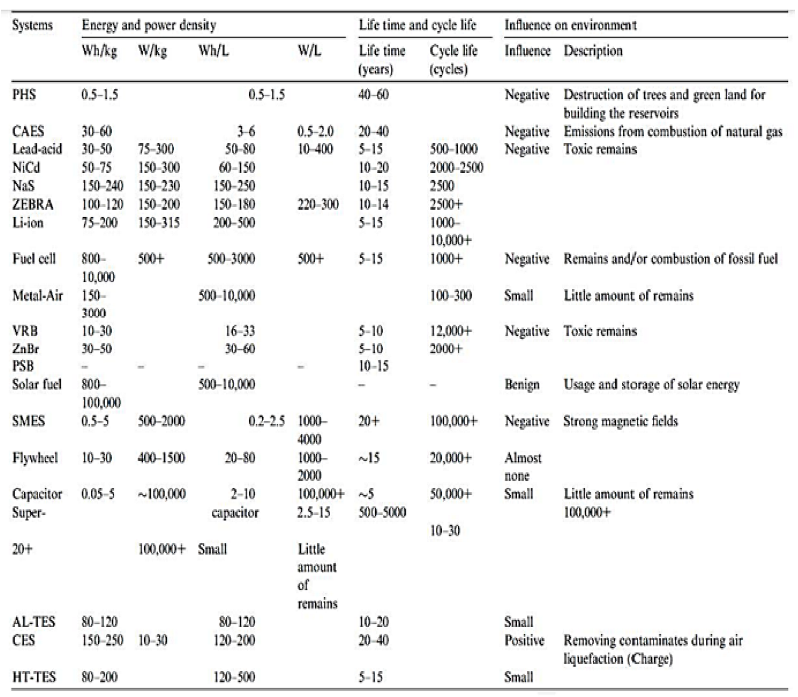

5. Comparison and Evaluation of the Energy Storage Technologies

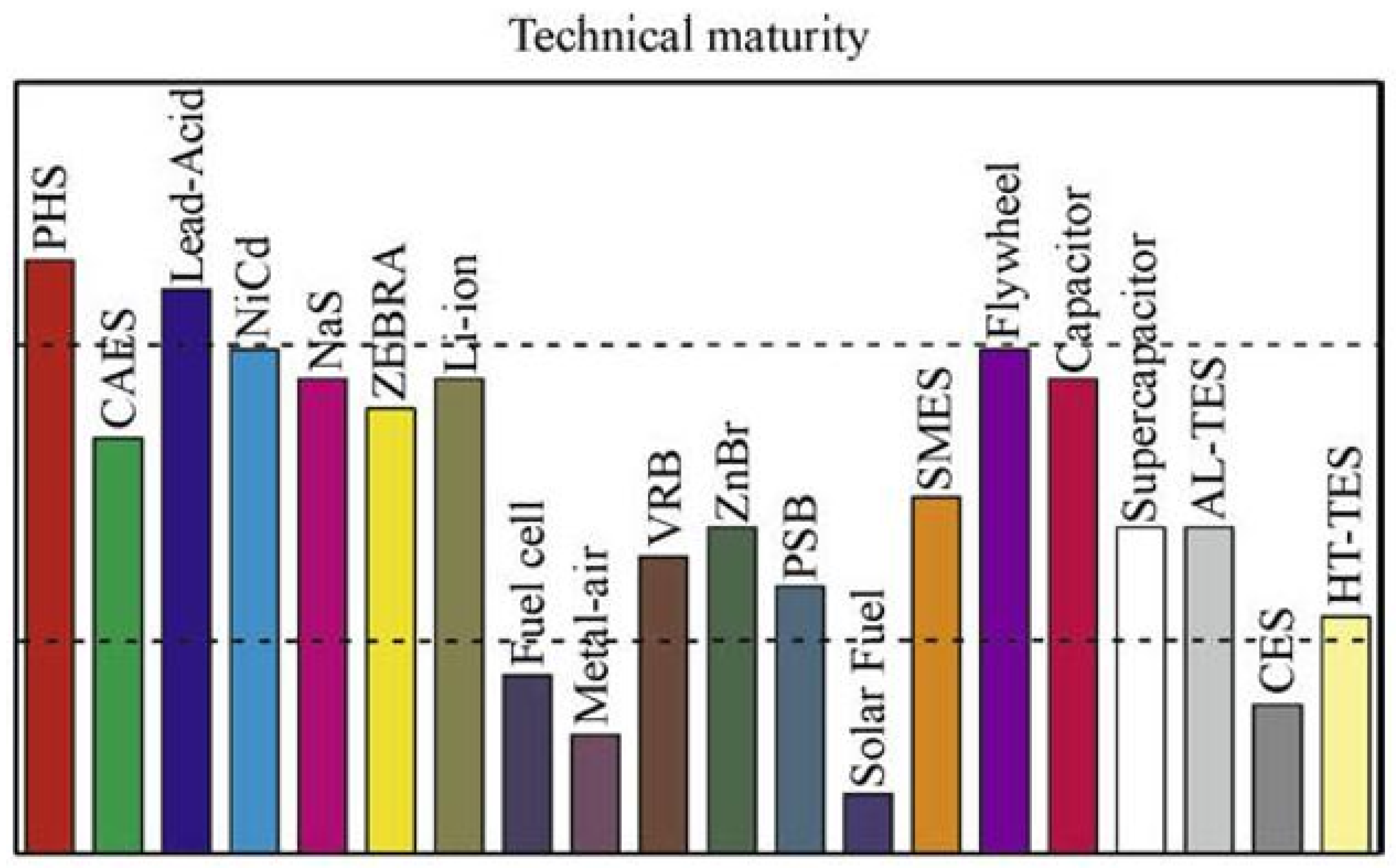

5.1. Technical Proficiency

- Advanced technologies: Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS) and lead-acid batteries fall into this category as they have been in use for over a century. These technologies have a proven track record and are widely deployed.

- Developed technologies:Examples of developed technologies include Aquiferous Low-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage (Al-TES), High-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage (HT-TES), Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES), ZEBRA Li-ion, Flow Batteries, Sodium-Sulfur (NaS), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), and Nickel-Cadmium (NiCd). These systems are now commercially available and have experienced technological advances. To assure their dependability and competitiveness, the electrical sector and the market must still validate and test them further before they can be widely adopted, particularly in large-scale utility applications.

- Developing technologies: Categorized as emerging technologies are Fuel cells, Metal-Air batteries, Solar Fuel, and Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES). Although they are not yet commercially mature, ongoing research and development efforts show their technical feasibility and potential. These emerging technologies hold promise for industrial adoption in the near future, driven by factors such as energy costs and environmental considerations.

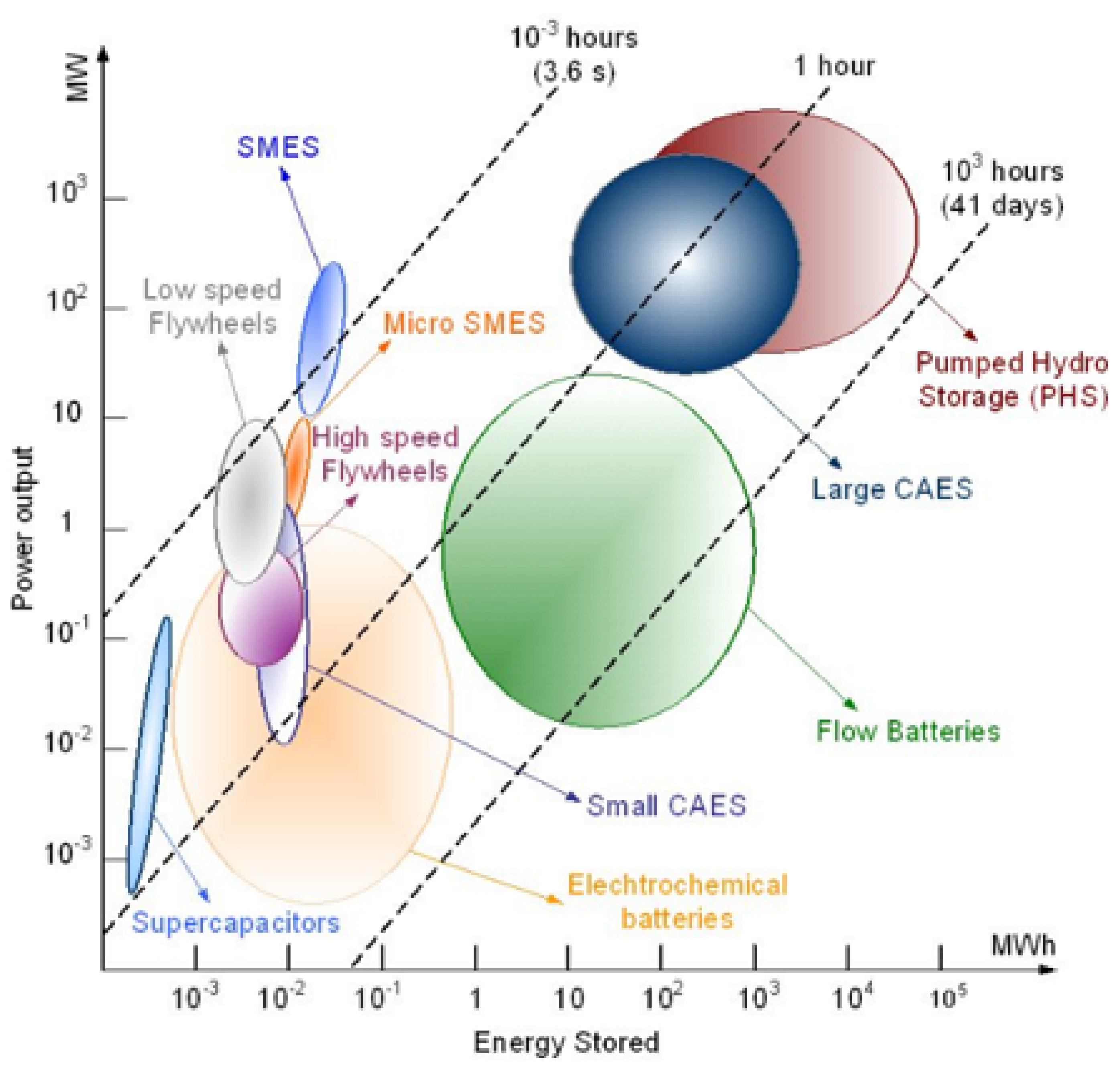

5.2. Discharge Time and Power Rating

- Energy management: In the realm of large-scale applications exceeding 100 MW, spanning hourly to daily output durations, compressed air energy storage (CAES), cryogenic energy storage (CES), and pumped hydro storage (PHS) stand as viable choices. These systems find utility in load leveling, ramping/load following, and spinning reserve scenarios within energy management. On the other hand, for medium-scale energy management with capacities ranging from 10 to 100 MW, options such as large batteries, flow batteries, fuel cells, CES, and Thermal Energy Storage (TES) hold relevance. [37].

- Power quality: Flywheels, batteries, Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES), capacitors, and supercapacitors exhibit rapid response times in the millisecond range, rendering them well-suited for applications necessitating power quality management. These applications include countering momentary voltage drops, resolving flicker-related concerns, and supplying short-duration Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) assistance. These technologies are typically employed for power ratings below 1 MW.

- Bridging power: Batteries, flow batteries, fuel cells, and Metal-Air cells showcase relatively swift response times (approximately 1 second) and can maintain power delivery for extended durations, rendering them apt choices for bridging power applications. These technologies are commonly used for power ratings ranging from 100 kW to 10 MW .

5.3. Duration of Storage

- Energy storage systems (EES) featuring minimal self-discharge rates, including Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), Fuel Cells, Metal-Air Cells, solar fuels, and flow batteries, are optimal choices for extended storage duration. These systems can effectively retain stored energy over extended durations.

- Energy storage systems (EES) characterized by moderate self-discharge rates, such as Lead-Acid, Nickel-Cadmium (NiCd), Lithium-Ion (Li-ion), Thermal Energy Storage (TES), and Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES), are well-matched for storage intervals ranging from a few days to several tens of days. While they exhibit higher self-discharge compared to the aforementioned systems, they still provide reasonable energy retention over moderate timeframes.

- EES systems with extremely high self-discharge ratios of 10–40% per day include sodium-sulfur (NaS), ZEBRA, superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES), capacitors, and supercapacitors. These systems work best with short cycles periods that last no longer than a few hours. NaS and ZEBRA have significant self-discharge ratios because of their high operating temperatures, which necessitate self-heating to maintain the effectiveness of the stored energy.

- Flywheels, however, will release all of the stored energy if the storage duration extends beyond approximately one day. Therefore, they are most effective for storage periods within tens of minutes, offering rapid discharge capabilities. The selection of an appropriate EES system depends on the desired storage period and the specific requirements of the application. Taking into account the self-discharge characteristics of the system is crucial to ensure efficient and effective energy storage.

|

5.4. Capital Cost

|

5.5. Cycle Efficiency

- Exceptionally high efficiency: SMES, flywheel, supercapacitor, and Li-ion battery demonstrate an exceptional cycle efficiency of more than 90%.

- High cycle efficiency: The cycle efficiencies of PHS, CAES, batteries (other than Li-ion), flow batteries, and conventional capacitors range from 60% to 90%. It is important to note that PHS, which involves pumping and releasing water, often has higher efficiency than CAES, which compresses and expands air. Gas is heated when it is compressed quickly, which raises its pressure and necessitates more energy for subsequent compression.

- Moderate to low efficiency: TESs, DMFCs, Metal-Air, solar fuel, hydrogen, and DMFCs (Direct Methanol Fuel Cell) exhibit moderate to low cycle efficiencies, falling below 60%. These systems primarily encounter substantial losses during the conversion from the commercial AC system to the storage system side. For instance, the power stored through hydrogen experiences a relatively lower round-trip energy efficiency (ranging between 20% and 50%) due to a combination of electrolyzer efficiency and the efficiency of reconversion back to electricity. It’s worth noting that a trade-off exists between capital cost and round-trip efficiency. A storage technology characterized by lower capital cost and round-trip efficiency could still present effective competition against a technology with higher capital cost and efficiency.

5.6. Power density

5.7. Lifetime and cycle life

6. Conclusion

- While an array of commercially accessible energy storage systems (EES) exists, there isn’t a singular system that meets all the criteria of an ideal EES, encompassing attributes like maturity, extended lifespan, cost-effectiveness, high density, superior efficiency, and eco-friendliness. Each EES finds its niche within a specific application domain. Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), large-scale batteries, flow batteries, fuel cells, solar fuels, Thermal Energy Storage (TES), and Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES) are well-suited for energy management applications. Flywheels, batteries, capacitors, and supercapacitors find better alignment with power quality and short-duration Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) needs. Batteries, flow batteries, fuel cells, and Metal-Air cells exhibit potential for bridging power applications.

- Certain energy storage technologies, such as Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS) and lead-acid batteries, have attained technical maturity. Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), Nickel-Cadmium (NiCd), Sodium-Sulfur (NaS), ZEBRA Li-ion, flow batteries, Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES), flywheels, capacitors, supercapacitors, Adiabatic Liquid Thermal Energy Storage (AL-TES), and High-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage (HT-TES) are both technically developed and commercially available. On the other hand, fuel cells, Metal-Air batteries, solar fuels, and Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES) are still in the developmental stages. Among the established technologies, CAES holds the advantage of having the lowest capital cost, while Metal-Air batteries have the potential to emerge as the most cost-effective among the recognized EES systems.

- Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES), flywheels, capacitors/supercapacitors, Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), batteries, and flow batteries showcase cycle efficiencies surpassing 60%. Conversely, fuel cells, Direct Methanol Fuel Cells (DMFC), Metal-Air batteries, solar fuels, Thermal Energy Storage (TES), and Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES) demonstrate lower efficiencies attributed to substantial losses during the conversion process from commercial AC to the stored energy state.

- Energy storage systems (EES) rooted in electrical technologies, like SMES, capacitors, and supercapacitors, boast extended cycle lifespans. Similarly, EES systems grounded in mechanical and thermal principles, encompassing Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), flywheels, Adiabatic Liquid Thermal Energy Storage (AL-TES), Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES), and High-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage (HT-TES), also exhibit prolonged cycle lives. Batteries, flow batteries, and fuel cells have comparatively lower cycle lives due to chemical deterioration over time. Currently, Metal-Air batteries have the shortest lifespan.

- Certain energy storage technologies, including Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), batteries, flow batteries, fuel cells, and Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES), may pose potential adverse environmental impacts due to factors like fossil fuel combustion, intense magnetic fields, landscape disruption, and the generation of toxic byproducts. Solar fuels and Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES) are generally regarded as more ecologically benign, although a thorough life-cycle analysis is imperative to establish definitive conclusions. In light of the insights gleaned from this study and a diligent assessment of the implications, the subsequent conclusions can be derived:

- Developing storage techniques requires improving and optimizing power electronics, which hold a pivotal role in transforming electricity into storable energy and vice versa.

- As renewable energy integration expands, it becomes imperative to examine the influence of various storage alternatives, especially decentralized ones, on network resilience, infrastructure, and the overall costs of energy production.

- Performing comprehensive system analyses that encompass storage, related electricity conversion, power electronics, and control systems will advance the optimization of approaches related to cost, efficiency, reliability, maintenance, as well as societal and environmental considerations, among other factors.

- Assessing the national significance of compressed gas storage methods holds importance.

- Allocating resources to research and development that integrates various storage methodologies with renewable energy sources will enhance overall system efficiency and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions originating from conventional gas-burning power plants.

- Evaluating the capabilities of high-temperature thermal storage systems, which provide notable benefits in power distribution, can facilitate their secure implementation in close proximity to power consumption regions.

- Progressing in the field of supercapacitors will result in their incorporation across a spectrum of applications.

- Creating cost-effective, durable flywheel storage systems will unleash their potential, especially in decentralized applications.

- A collaborative research and development (R&D) effort is required to accelerate the adoption and utilization of hydrogen-electrolyzer fuel-cell storage systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Smith, S.C.; Sen, P.; Kroposki, B. Advancement of energy storage devices and applications in electrical power system. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting-Conversion and Delivery of Electrical Energy in the 21st Century. IEEE, 2008, pp. 1–8.

- Salvarli, M.S.; Salvarli, H. For sustainable development: Future trends in renewable energy and enabling technologies. In Renewable energy-resources, challenges and applications; IntechOpen, 2020.

- Ghosh, P.; Emonts, B.; Janßen, H.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. Ten years of operational experience with a hydrogen-based renewable energy supply system. Solar Energy 2003, 75, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraftnät, S. Information om stödtjänster. Svenska Kraftnät 2020, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiq, A. Sizing and optimization of battery energy storage system for wind and solar power plant in a distribution grid: A case study on optimizing the size of the battery for peak shaving and ancillary services, 2021.

- Hamsic, N.; Schmelter, A.; Mohd, A.; Ortjohann, E.; Schultze, E.; Tuckey, A.; Zimmermann, J. Stabilising the grid voltage and frequency in isolated power systems using a flywheel energy storage system. In Proceedings of the The Great Wall World Renewable Energy Forum, 2006, number October, pp. 1–6. 1–6.

- Ibrahim, H.; Beguenane, R.; Merabet, A. Technical and financial benefits of electrical energy storage. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference. IEEE, 2012, pp. 86–91.

- McDowall, J.A. Status and outlook of the energy storage market. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting. IEEE, 2007, pp. 1–3.

- Baker, J.; Collinson, A. Electrical energy storage at the turn of the millennium. Power Engineering Journal 1999, 13, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgotra, N. Energy Storage in Power Applications. International Journal of Analysis of Electrical Machines 2017, 3, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ahearne, J. Storage of electric energy, Report on research and development of energy technologies. International Union of Pure and Applied Physics 2004, 76, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, D. A review of energy storage technologies: for the integration of fluctuating renewable energy 2010.

- Van Der Linden, S. The commercial world of energy storage: a review of operating facilities. 2003 1 st Annual Conference of the Energy Storage Council, Houston TX, 2003.

- Sobczyński, D.; Pawłowski, P. Energy storage systems for renewable energy sources. 2021 Selected Issues of Electrical Engineering and Electronics (WZEE), 2021; 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Walawalkar, R.; Apt, J.; Mancini, R. Economics of electric energy storage for energy arbitrage and regulation in New York. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2558–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cong, T.N.; Yang, W.; Tan, C.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Progress in electrical energy storage system: A critical review. Progress in natural science 2009, 19, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C.; Carta, J.A. Wind powered pumped hydro storage systems, a means of increasing the penetration of renewable energy in the Canary Islands. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2006, 10, 312–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyglakis, L.; Bintoudi, A.D.; Bezas, N.; Isaioglou, G.; Gkaidatzis, P.A.; Tryferidis, A.; Tzovaras, D.; Parcharidis, S. Energy Storage Systems in Residential Applications for Optimised Economic Operation: Design and Experimental Validation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–5.

- Najjar, Y.S.; Zaamout, M.S. Performance analysis of compressed air energy storage (CAES) plant for dry regions. Energy conversion and management 1998, 39, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, G.; Fang, M.; Wang, Q. A new compressed air energy storage refrigeration system. Energy Conversion and Management 2006, 47, 3408–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.; Spindler, W.; Grefe, G. Overview of battery power regulation and storage. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 1991, 6, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.J.; Andre, R.; Bessa, R.; Gouveia, C.; Araujo, A.; Guerra, F.; DamáSio, J.; Bravo, G.; Sumaili, J. Energy storage management for grid operation purposes. In Proceedings of the CIRED Workshop 2016. IET, 2016, pp. 1–4.

- Karpinski, A.; Makovetski, B.; Russell, S.; Serenyi, J.; Williams, D. Silver–zinc: status of technology and applications. Journal of Power Sources 1999, 80, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalk, S.G.; Miller, J.F. Key challenges and recent progress in batteries, fuel cells, and hydrogen storage for clean energy systems. Journal of Power Sources 2006, 159, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, O. Hydrogen-the flexible storage for electrical energy. Power Engineering Journal 1999, 13, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkert, W.J.; Jamet, F. Electric energy gun technology: status of the French-German-Netherlands programme. IEEE transactions on magnetics 1999, 35, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Cheng, K.W.E.; Sutanto, D. A study of the status and future of superconducting magnetic energy storage in power systems. Superconductor Science and Technology 2006, 19, R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. Bulk energy storage potential in the USA, current developments and future prospects. Energy 2006, 31, 3446–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A. Techno-economic analysis of different energy storage technologies. In Energy Storage-Technologies and Applications; IntechOpen, 2013.

- Carmen. Beacon Power Stephentown - flywheel energy storage system, US, 2021.

- Rosen, M. Second-law analysis of aquifer thermal energy storage systems. Energy 1999, 24, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ding, Y.; Peters, T.; Berger, F. Method of storing energy and a cryogenic energy storage system, 2016. US Patent App. 15/053,840.

- Xue, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Cui, C.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. Thermodynamic analysis of a novel liquid air energy storage system. Physics procedia 2015, 67, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Fernéndez, H.; Restrepo, M.; Arango-Manrique, A. A study on control strategies for aggregated community energy storage systems in medium voltage distribution networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 119321–119332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F.; Hussain, S.S.; Tiwari, P.K.; Goswami, A.K.; Ustun, T.S. Comparative review of energy storage systems, their roles, and impacts on future power systems. IEEE access 2018, 7, 4555–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, I.B. Recent advances in the US Department of Energy’s energy storage technology research and development programs for hybrid electric and electric vehicles. Journal of Power Sources 2002, 110, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storage, C.A.E.; Japan, O. Pumped Hydro Storage.

- Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A.; Younes, R.; Perron, J.; Basbous, T. Study of a hybrid wind-diesel system with compressed air energy storage. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Canada Electrical Power Conference. IEEE, 2007, pp. 320–325.

- Farhadi, M.; Mohammed, O. Energy storage systems for high power applications. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting. IEEE, 2015, pp. 1–7.

- Bari, R.T.B.; Rahman, T.; Punny, M.J.; Mian, M.M.; Faisal, F.; Nishat, M.M. Investigation of the Impact of AC Harmonics on Lead Acid Battery Degradation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE IAS Global Conference on Emerging Technologies (GlobConET). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A.; Perron, J. Solutions actuelles pour une meilleure gestion et intégration de la ressource éolienne 2008.

- Ratering-Schnitzler, B.; Harke, R.; Schroeder, M.; Stephanblome, T.; Kriegler, U. Voltage quality and reliability from electrical energy-storage systems. Journal of power sources 1997, 67, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walawalkar, R.; Apt, J. Market analysis of emerging electric energy storage systems. National Energy Technology Laboratory, 2008; 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rebours, Y.; Kirschen, D. What is spinning reserve. The University of Manchester 2005, 174.

- Wu, P.; Bucknall, R. Hybrid fuel cell and battery propulsion system modelling and multi-objective optimisation for a coastal ferry. International journal of hydrogen energy 2020, 45, 3193–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyer, J.M.; Corey, G.P.; Iannucci Jr, J.J. Energy storage benefits and market analysis handbook: a study for the DOE Energy Storage Systems Program. Technical report, Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), Albuquerque, NM, and Livermore, CA …, 2004.

- Eyer, J.; Corey, G. Energy storage for the electricity grid: Benefits and market potential assessment guide. Sandia National Laboratories 2010, 20, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Pan, J.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Guo, C.; Guo, Y. A review of energy storage system study. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2). IEEE, 2020, pp. 2858–2863.

- Eckroad, S.; Gyuk, I. EPRI-DOE handbook of energy storage for transmission & distribution applications. Electric Power Research Institute, Inc, 2003; 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenung, S.M.; Hassenzahl, W.V. Long-vs. short-term energy storage technologies analysis: a life-cycle cost study: a study for the DOE energy storage systems program. Technical report, Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), Albuquerque, NM, and Livermore, CA …, 2003.

- Gergaud, O. Modélisation énergétique et optimisation économique d’un système de production éolien et photovoltaïque couplé au réseau et associé à un accumulateur. PhD thesis, École normale supérieure de Cachan-ENS Cachan, 2002.

- Messenger, R.A.; Abtahi, A. Photovoltaic systems engineering; CRC press, 2018.

- Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A.; Perron, J. Energy storage systems—Characteristics and comparisons. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2008, 12, 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Hannan, M.A.; Ker, P.J.; Hussain, A.; Mansor, M.B.; Blaabjerg, F. Review of energy storage system technologies in microgrid applications: Issues and challenges. Ieee Access 2018, 6, 35143–35164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multon, B.; Ruer, J. Stocker l’électricité: oui, c’est indispensable et c’est possible. Pourquoi, où, comment? Publication ECRIN en contribution au débat national sur l’énergie, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Amiryar, M.E.; Pullen, K.R. A review of flywheel energy storage system technologies and their applications. Applied Sciences 2017, 7, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robyns, B.; Ansel, A.; Davigny, A.; Saudemont, C.; Cimuca, G. Contribution du stockage de l’énergie électrique à la participation aux services système des éoliennes 2005.

- Anzano, J.; Jaud, P.; Madet, D. Stockage de l’électricité dans le système de production électrique. Techniques de l’ingénieur, traité de Génie Électrique D 1989, 4030, 09. [Google Scholar]

- Coppez, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Chowdhury, S. South African renewable energy hybrid power system storage needs, challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1–9.

- Robin, G.; Ruellan, M.; Multon, B.; Ahmed, H.B.; Glorennec, P.Y. Solutions de stockage de l’énergie pour les systèmes de production intermittente d’électricité renouvelable. In Proceedings of the Colloque SeaTechWeek 2004 (Semaine Internat. des Technologies de la Mer), 2004, p. 9p.

- Chatrung, N. Battery energy storage system (bess) and development of grid scale bess in egat. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE PES GTD Grand International Conference and Exposition Asia (GTD Asia). IEEE, 2019, pp. 589–593.

- Faure, F. Suspension magnetique pour volant d’inertie. PhD thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble-INPG, 2003.

- Vazquez, S.; Lukic, S.M.; Galvan, E.; Franquelo, L.G.; Carrasco, J.M. Energy storage systems for transport and grid applications. IEEE Transactions on industrial electronics 2010, 57, 3881–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, N.; Venkatesh, B. Energy storage and power systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 25th IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE). IEEE, 2012, pp. 1–4.

- Clemente, A.; Costa-Castelló, R. Redox flow batteries: A literature review oriented to automatic control. Energies 2020, 13, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acp. The American Clean Power Association (ACP), 2023.

- Arfoa, A.A.; Almaita, E.; Alshkoor, S.; Shloul, M. Techno-Economic Feasibility Analysis of On-Grid Battery Energy Storage System: Almanara PV Power Plant Case Study. Jordan Journal of Electrical Engineering. All rights reserved-Volume 2022, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petinrin, J.; Shaaban, M. Implementation of energy storage in a future smart grid. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2013, 7, 273–279. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).