Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

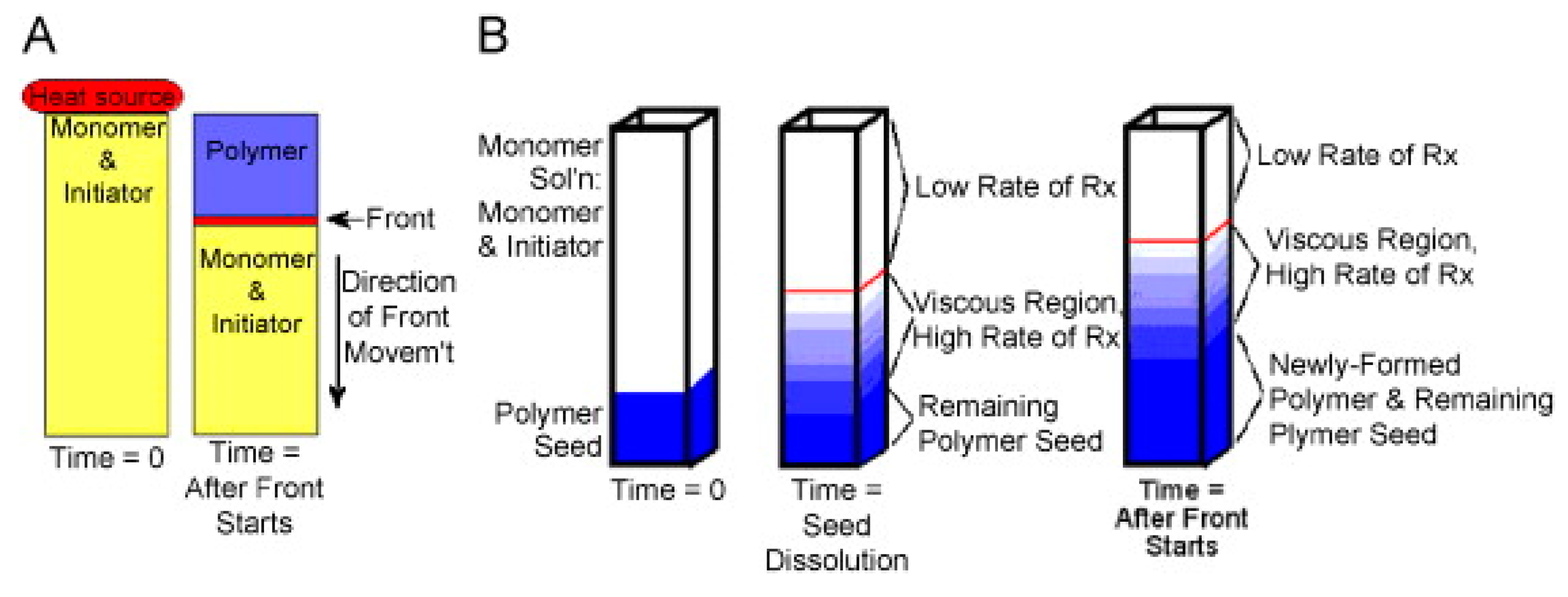

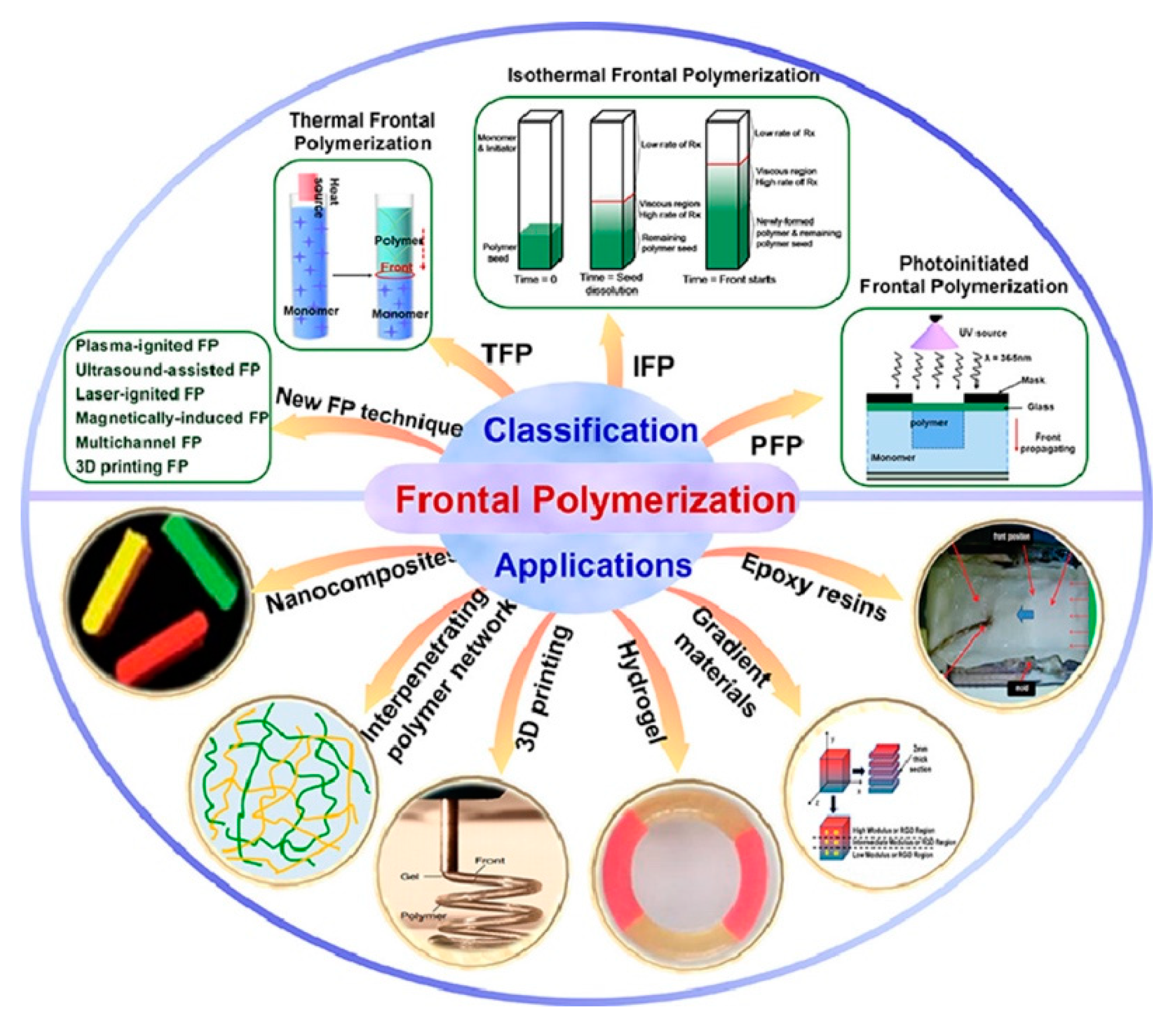

2. Fundamentals of the frontal polymerization technique

2.1. Definitions

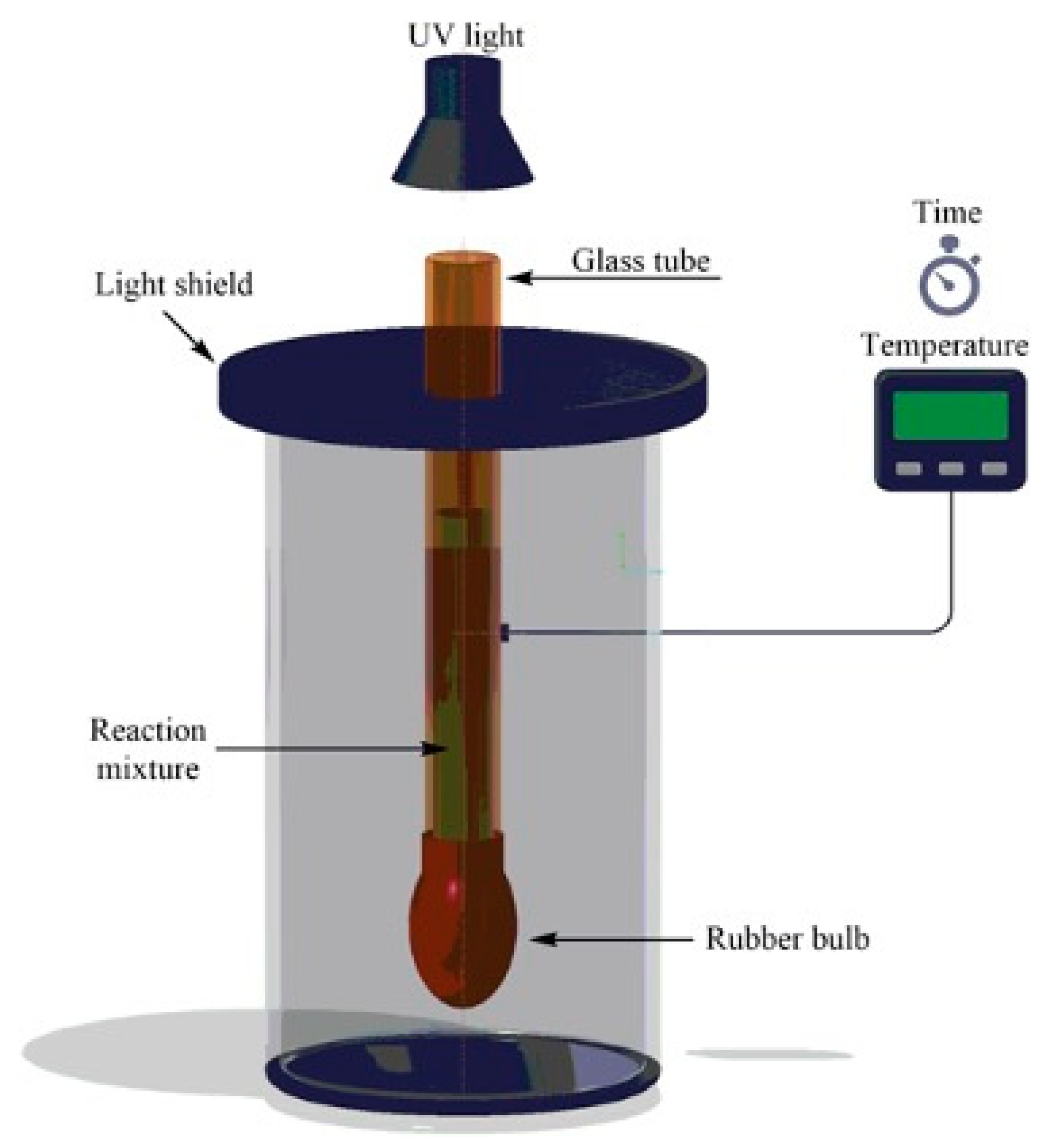

2.2. Reactor characteristics

2.3. Direction of front propagation and stirring

2.4. Fingering

2.5. Monomers

2.6. Mechanisms, reaction kinetics, initiators and catalysts

2.7. Solvents

2.8. Viscosity

2.9. Composites

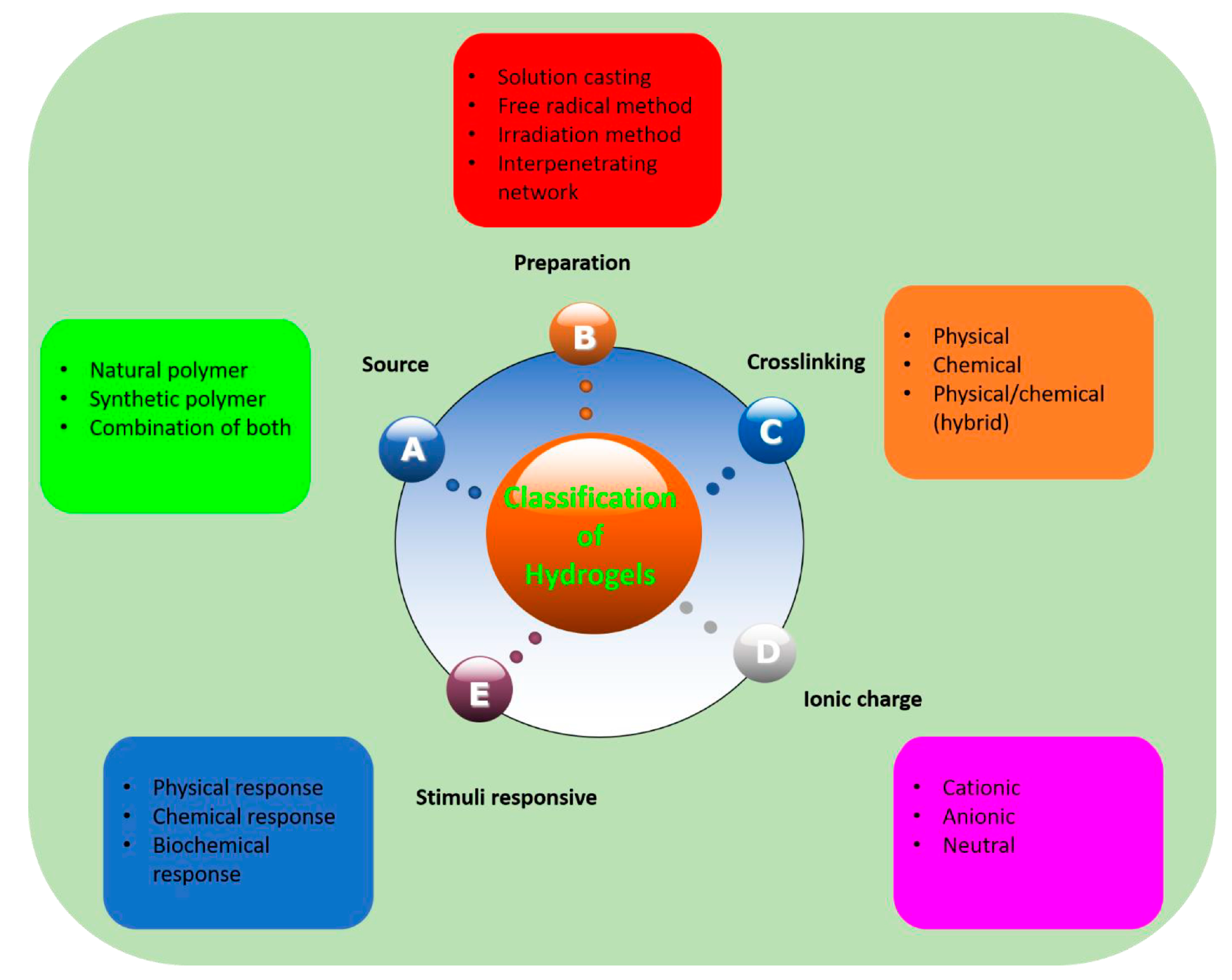

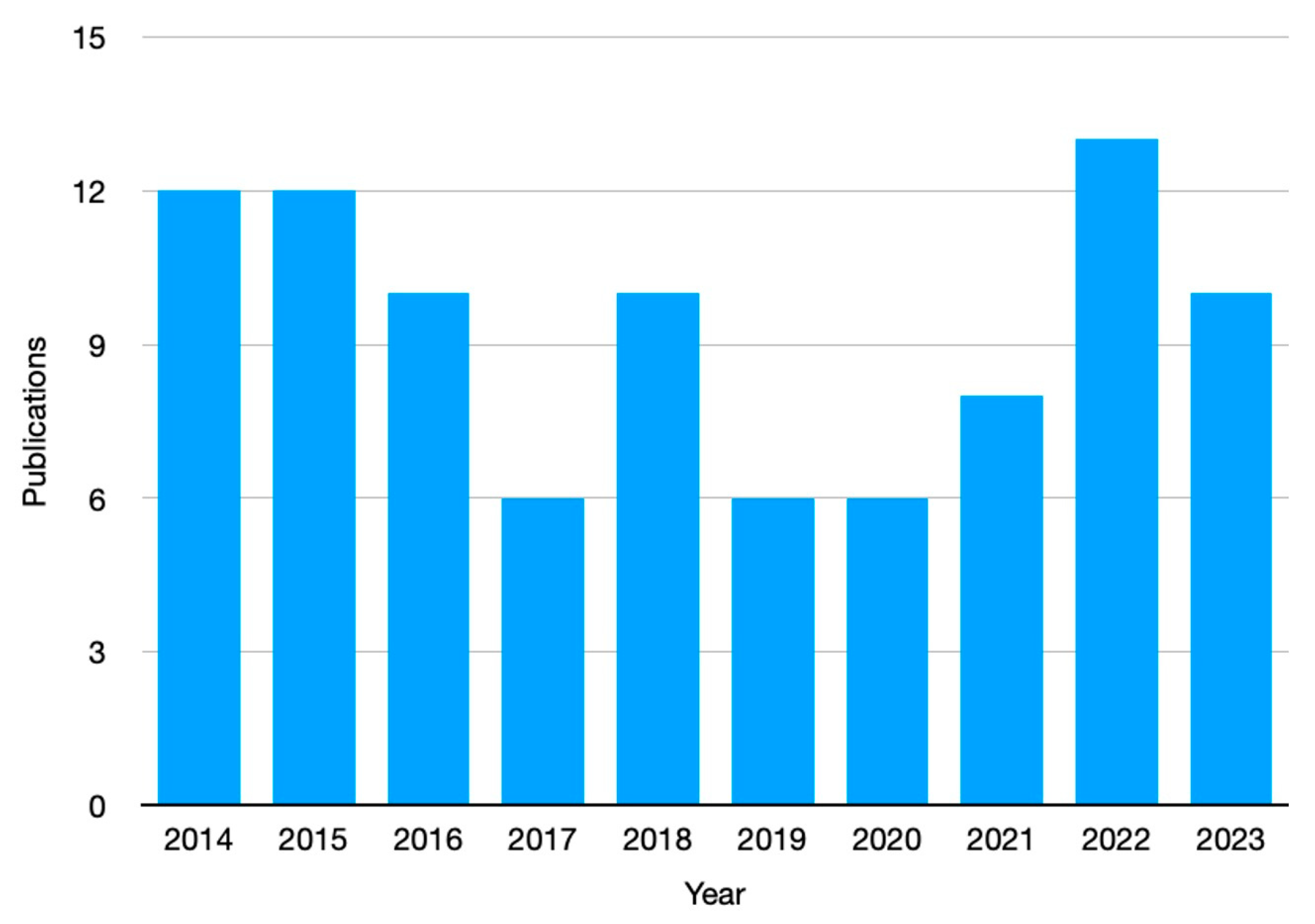

3. Hydrogels obtained by frontal polymerization

3.1. Monomers

3.2. Solvents

3.3. Initiators

3.4. Front temperature and material characteristics

4. Applications of frontally polymerized hydrogels

4.1. Biomedical applications

4.2. Drug delivery

4.3. Self-healing

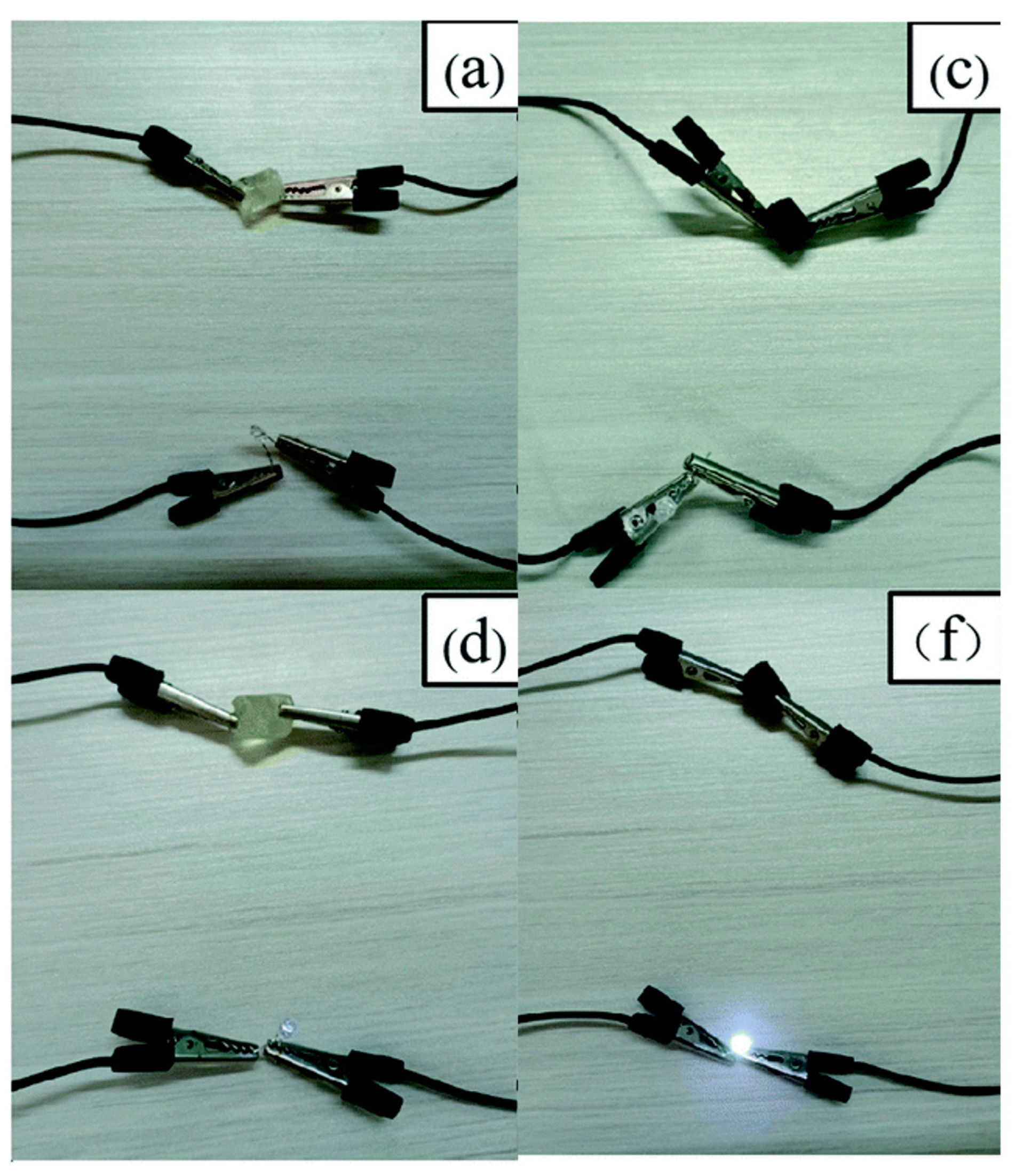

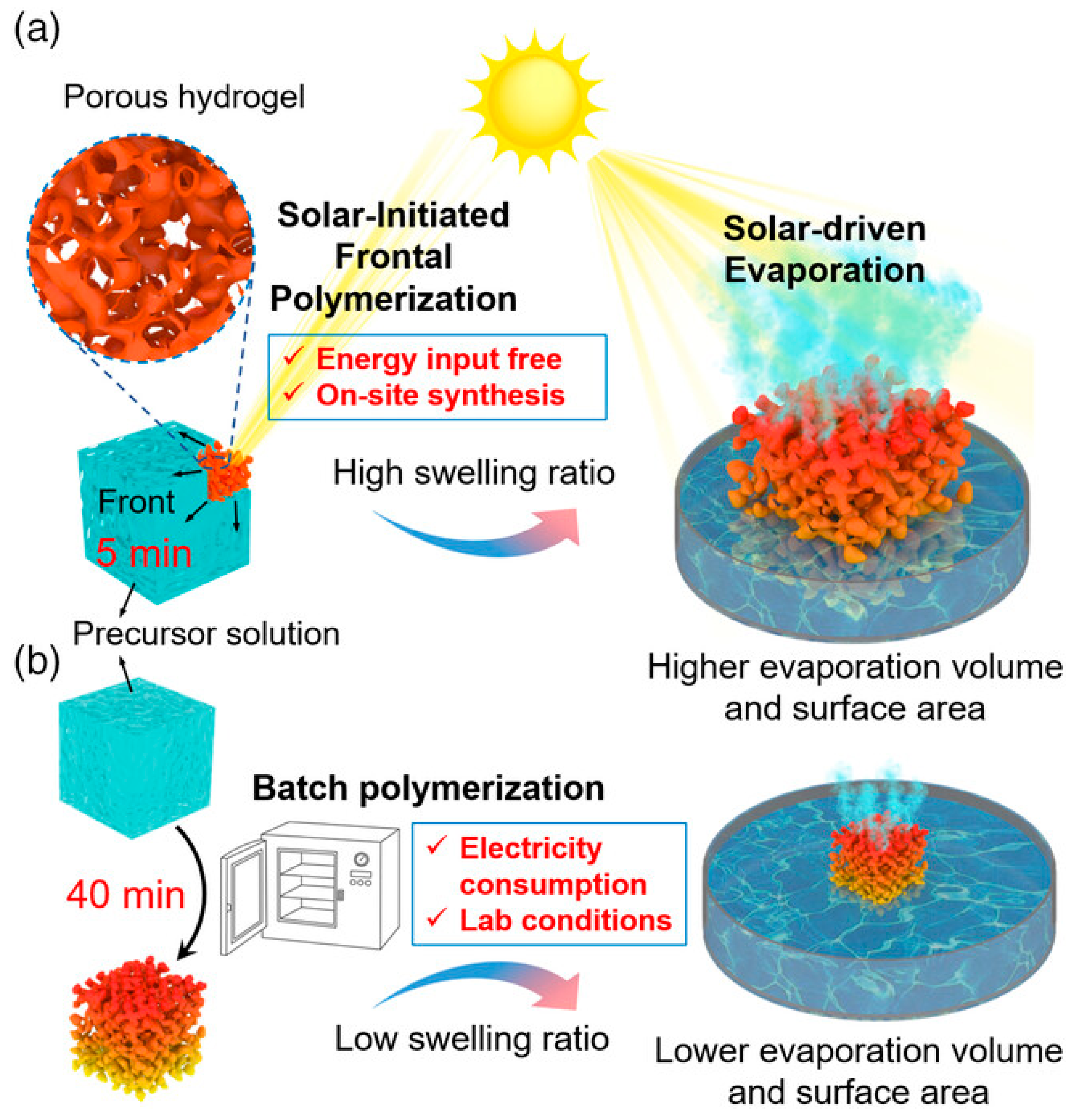

4.4. Other applications: electrically conductive and photothermic hydrogels

5. Conclusions and perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wichterle, O.; Lím, D. Hydrophilic Gels for Biological Use. Nature 1960, 185, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, S.; Grosskopf, A. K.; Lopez Hernandez, H.; Chan, D.; Yu, A. C.; Stapleton, L. M.; Appel, E. A. Translational Applications of Hydrogels. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11385–11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Inda, M. E.; Lai, Y.; Lu, T. K.; Zhao, X. Engineered Living Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, S.; Hina, M.; Iqbal, J.; Rajpar, A. H.; Mujtaba, M. A.; Alghamdi, N. A.; Wageh, S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S. Fundamental Concepts of Hydrogels: Synthesis, Properties, and Their Applications. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhi, C. Hydrogel Electrolytes for Flexible Aqueous Energy Storage Devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, H.; Ng, P. F.; Chow, L.; Fei, B. Recent Advances of Hydrogel Electrolytes in Flexible Energy Storage Devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 2043–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davtyan, S. P.; Tonoyan, A. O. The Frontal Polymerization Method in High Technology Applications. Rev. J. Chem. 2019, 9, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shen, H.-X.; Liu, C.; Wang, C.-F.; Zhu, L.; Chen, S. Advances in Frontal Polymerization Strategy: From Fundamentals to Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 127, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslick, B. A.; Hemmer, J.; Groce, B. R.; Stawiasz, K. J.; Geubelle, P. H.; Malucelli, G.; Mariani, A.; Moore, J. S.; Pojman, J. A.; Sottos, N. R. Frontal Polymerizations: From Chemical Perspectives to Macroscopic Properties and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 3237–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Fiori, S.; Bidali, S.; Alzari, V.; Malucelli, G. Frontal Polymerization of Diurethane Diacrylates. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 3344–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illescas, J.; Ortíz-Palacios, J.; Esquivel-Guzmán, J.; Ramirez-Fuentes, Y. S.; Rivera, E.; Morales-Saavedra, O. G.; Rodríguez-Rosales, A. A.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Scognamillo, S.; Mariani, A. Preparation and Optical Characterization of Two Photoactive Poly(Bisphenol a Ethoxylate Diacrylate) Copolymers Containing Designed Amino-Nitro-Substituted Azobenzene Units, Obtained via Classical and Frontal Polymerization, Using Novel Ionic Liquids as In. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 1906–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.-D.; Liu, X.; Pang, Q.-Q.; Huang, Y.-P.; Liu, Z.-S. Rapid Preparation of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer by Frontal Polymerization. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 3205–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, T.; Fazende, K.; Jee, E.; Wu, Q.; Pojman, J. A. Cure-on-demand Wood Adhesive Based on the Frontal Polymerization of Acrylates. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, app.44064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I. D.; Yourdkhani, M.; Centellas, P. J.; Aw, J. E.; Ivanoff, D. G.; Goli, E.; Lloyd, E. M.; Dean, L. M.; Sottos, N. R.; Geubelle, P. H.; Moore, J. S.; White, S. R. Rapid Energy-Efficient Manufacturing of Polymers and Composites via Frontal Polymerization. Nature 2018, 557, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L. L.; Massey, K. N.; Meyer, E. R.; McPherson, J. R.; Hanna, J. S. New Insight into Isothermal Frontal Polymerization Models: Wiener’s Method to Determine the Diffusion Coefficients for High Molecular-Weight Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) with Neat Methyl Methacrylate. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2008, 46, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojman, J. A. Frontal Polymerization. In Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference; Elsevier, 2012; pp. 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojman, J. A.; Ilyashenko, V. M.; Khan, A. M. Free-Radical Frontal Polymerization: Self-Propagating Thermal Reaction Waves. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1996, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, G.; Garbey, M.; Ilyashenko, V. M.; Pojman, J. A.; Solovyov, S. E.; Taik, A.; Volpert, V. A. Effect of Convection on a Propagating Front with a Solid Product: Comparison of Theory and Experiments. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojman, J. A.; Craven, R.; Khan, A.; West, W. Convective Instabilities in Traveling Fronts of Addition Polymerization. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 7466–7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Nuvoli, D.; Alzari, V.; Pini, M. Phosphonium-Based Ionic Liquids as a New Class of Radical Initiators and Their Use in Gas-Free Frontal Polymerization. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5191–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, S.; Mariani, A.; Ricco, L.; Russo, S. First Synthesis of a Polyurethane by Frontal Polymerization. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 2674–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Bidali, S.; Fiori, S.; Malucelli, G.; Sanna, E. Synthesis and Characterization of a Polyurethane Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. E-Polym. 2003, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamillo, S.; Gioffredi, E.; Piccinini, M.; Lazzari, M.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Sanna, R.; Piga, D.; Malucelli, G.; Mariani, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanocomposites of Thermoplastic Polyurethane with Both Graphene and Graphene Nanoribbon Fillers. Polymer 2012, 53, 4019–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Bidali, S.; Fiori, S.; Sangermano, M.; Malucelli, G.; Bongiovanni, R.; Priola, A. UV-Ignited Frontal Polymerization of an Epoxy Resin. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 2066–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Bidali, S.; Caria, G.; Monticelli, O.; Russo, S.; Kenny, J. M. Synthesis and Characterization of Epoxy Resin-Montmorillonite Nanocomposites Obtained by Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamillo, S.; Bounds, C.; Thakuri, S.; Mariani, A.; Wu, Q.; Pojman, J. A. Frontal Cationic Curing of Epoxy Resins in the Presence of Defoaming or Expanding Compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Fiori, S.; Chekanov, Y.; Pojman, J. A. Frontal Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Dicyclopentadiene. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 6539–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiu, A.; Sanna, D.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Mariani, A. Advances in the Frontal Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Dicyclopentadiene. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 2776–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masere, J.; Chekanov, Y.; Warren, J. R.; Stewart, F. D.; Al-Kaysi, R.; Rasmussen, J. K.; Pojman, J. A. Gas-Free Initiators for High-Temperature Free-Radical Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 3984–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Sanna, D.; Ruiu, A.; Mariani, A. Effect of Limonene on the Frontal Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Dicyclopentadiene. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Scognamillo, S.; Piccinini, M.; Gioffredi, E.; Malucelli, G.; Marceddu, S.; Sechi, M.; Sanna, V.; Mariani, A. Graphene-Containing Thermoresponsive Nanocomposite Hydrogels of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Sanna, R.; Scognamillo, S.; Piccinini, M.; Kenny, J. M.; Malucelli, G.; Mariani, A. In Situ Production of High Filler Content Graphene-Based Polymer Nanocomposites by Reactive Processing. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, S.; Tullier, M.; Morejon-Garcia, C.; Guidry, J.; Runnoe, E.; Pojman, J. A. The Effect of Acrylate Functionality on Frontal Polymerization Velocity and Temperature. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2019, 57, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, G.; Cozzani, M.; Di Lisa, D.; Pastorino, L.; Mariani, A.; Monticelli, O. Mechanically-Reinforced Biocompatible Hydrogels Based on Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) and Star-Shaped Polycaprolactones. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 195, 112239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, G.; Maddalena, L.; Fina, A.; Cavallo, D.; Müller, A. J.; Caputo, M. R.; Mariani, A.; Monticelli, O. On Novel Hydrogels Based on Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Acrylate) and Polycaprolactone with Improved Mechanical Properties Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 171, 111226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuvoli, L.; Sanna, D.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Sanna, V.; Malfatti, L.; Mariani, A. Double Responsive Copolymer Hydrogels Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 2166–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuvoli, D.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, L.; Rassu, M.; Sanna, D.; Mariani, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(2-Hydroxyethylacrylate)/β-Cyclodextrin Hydrogels Obtained by Frontal Polymerization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 150, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

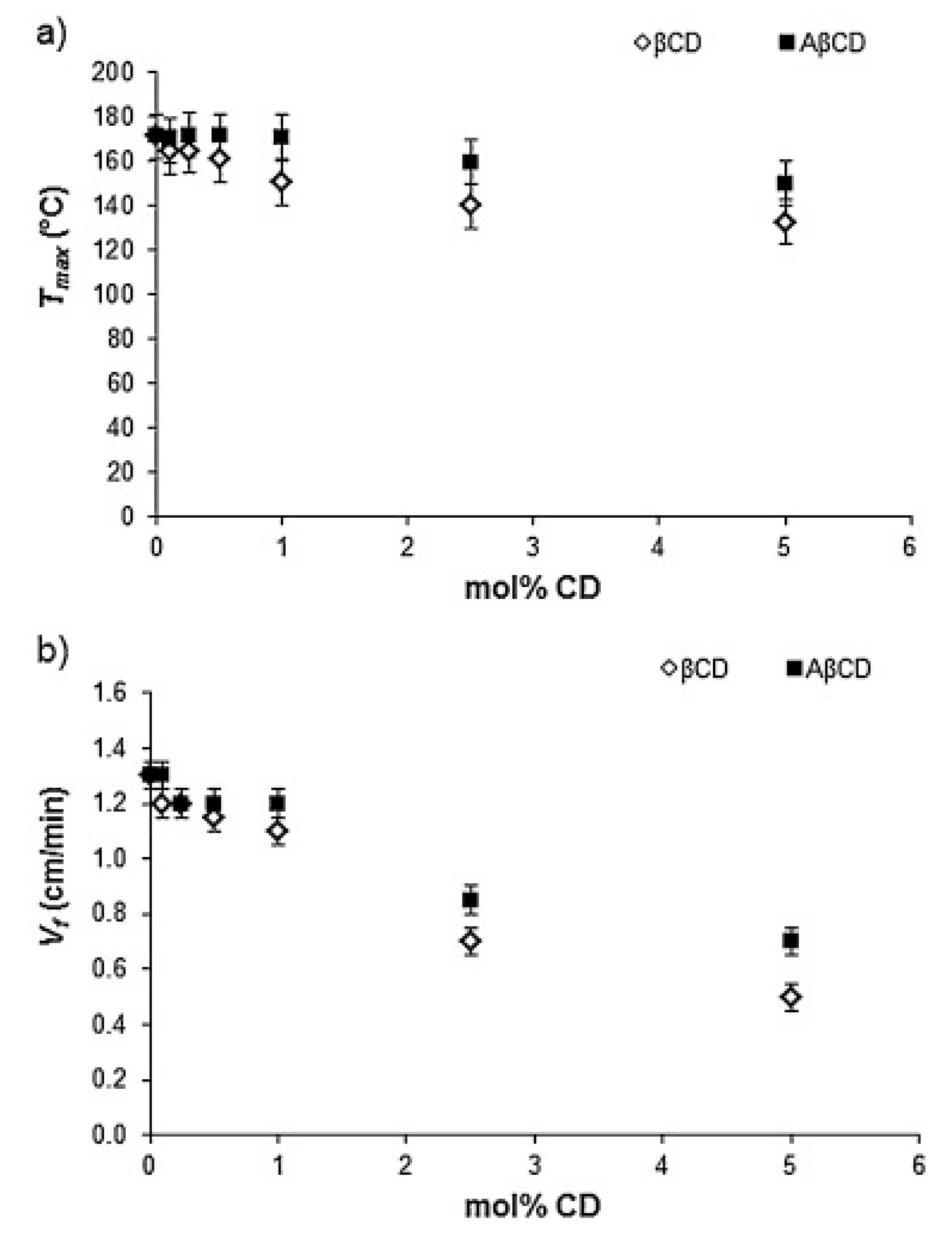

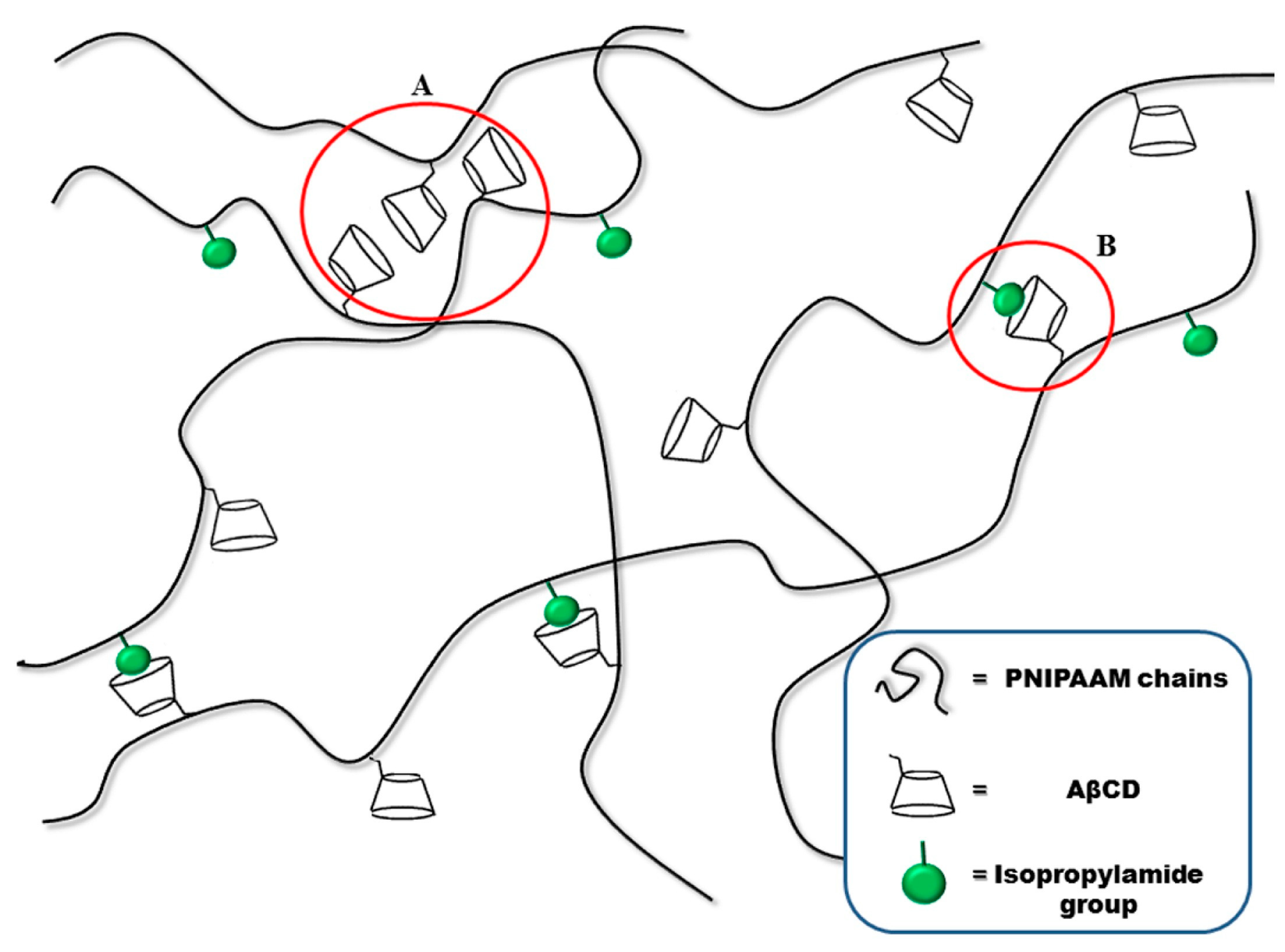

- Sanna, D.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Nuvoli, L.; Rassu, M.; Sanna, V.; Mariani, A. β-Cyclodextrin-Based Supramolecular Poly( N -Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogels Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, S.; Xia, Z.; Yan, Q.-Z. Preparation of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)/Montmorillonite Composite Hydrogel by Frontal Polymerization. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2017, 295, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassu, M.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Nuvoli, L.; Sanna, D.; Sanna, V.; Malucelli, G.; Mariani, A. Semi-Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Methyl Cellulose and Polyacrylamide Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. L.; Abbott, A. P.; Ryder, K. S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C. J.; Tu, W.-C.; Levers, O.; Bröhl, A.; Hallett, J. P. Green and Sustainable Solvents in Chemical Processes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 747–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

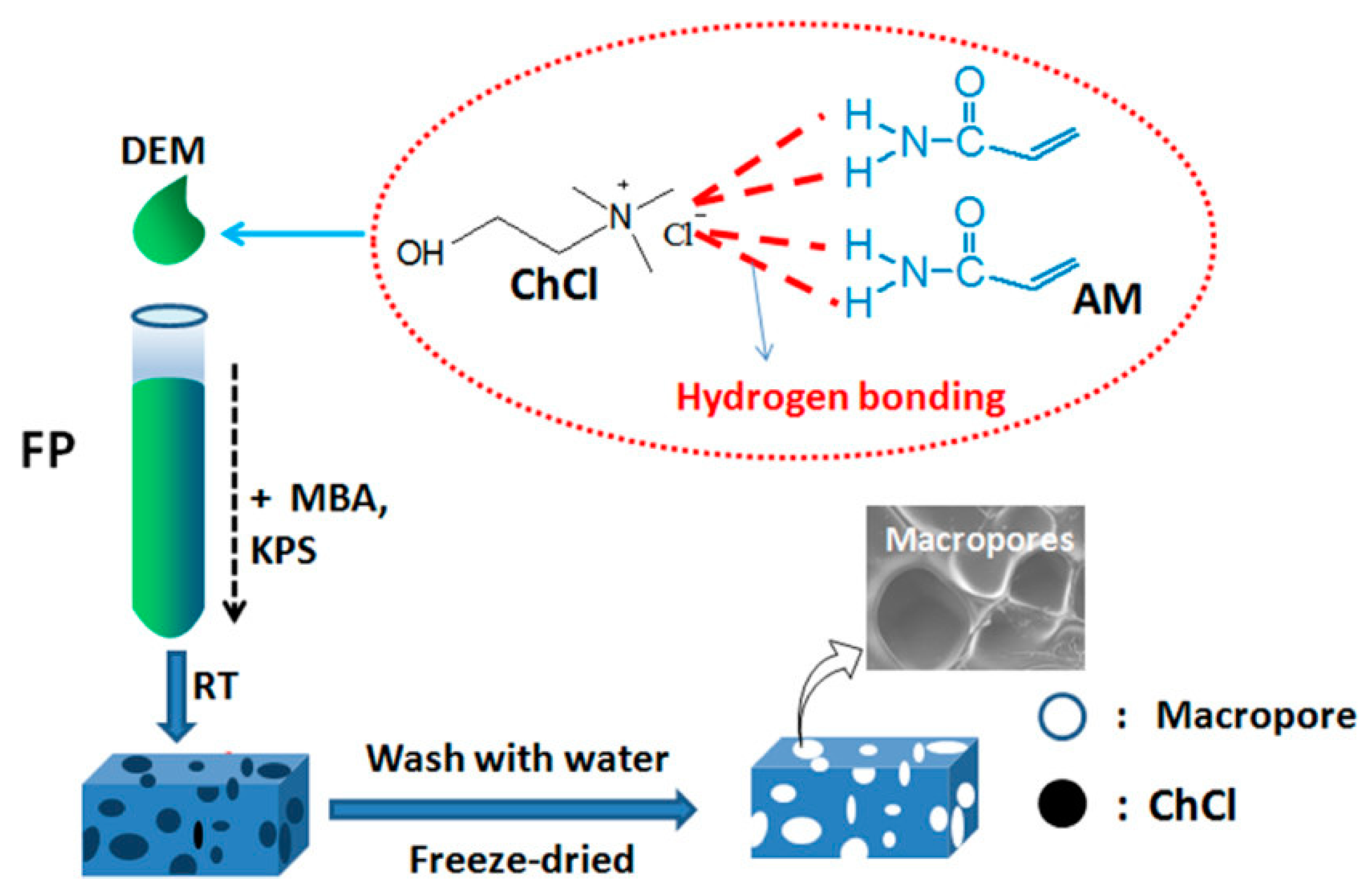

- Jiang, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Yan, S.; Tao, M.; Wen, P. Facile and Green Preparation of Superfast Responsive Macroporous Polyacrylamide Hydrogels by Frontal Polymerization of Polymerizable Deep Eutectic Monomers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

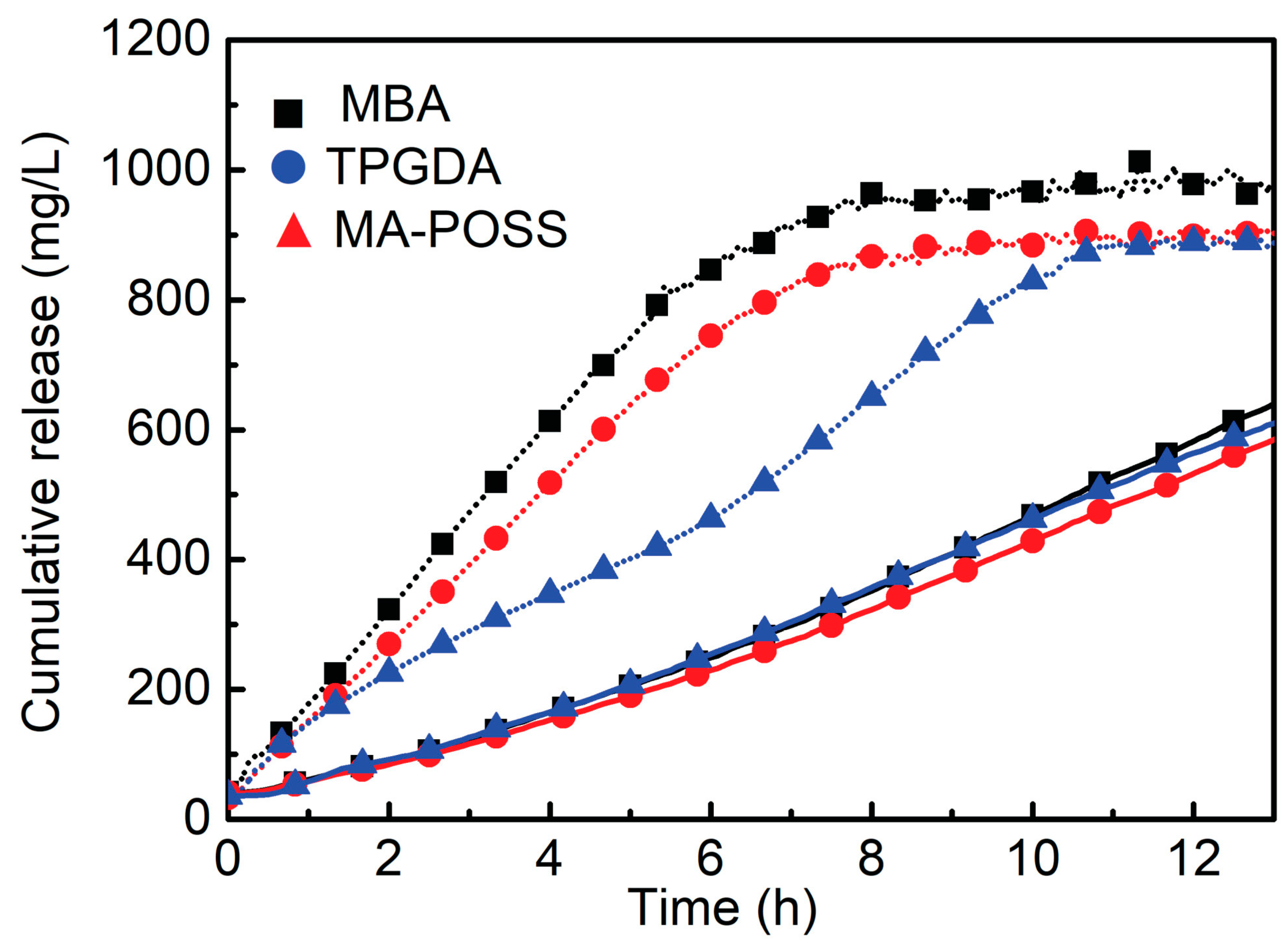

- Gavini, E.; Mariani, A.; Rassu, G.; Bidali, S.; Spada, G.; Bonferoni, M. C.; Giunchedi, P. Frontal Polymerization as a New Method for Developing Drug Controlled Release Systems (DCRS) Based on Polyacrylamide. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-L.; Yao, H.-F.; Li, X.-Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.-P.; Liu, Z.-S. PH/Temperature-Sensitive Hydrogel-Based Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (HydroMIPs) for Drug Delivery by Frontal Polymerization. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 94038–94047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, X.; Yan, Q. Frontal Polymerization and Characterization of Interpenetrating Polymer Networks Composed of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) and Polyvinylpyrrolidone. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Nuvoli, L.; Sanna, D.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Rassu, M.; Malucelli, G. Semi-Interpenetrating Polymer Networks Based on Crosslinked Poly( N -Isopropyl Acrylamide) and Methylcellulose Prepared by Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2018, 56, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Cui, Y. Preparation and Performance of Thermosensitive Poly( N -isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogels by Frontal Photopolymerization. Polym. Int. 2019, 68, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortenberry, D. I.; Pojman, J. A. Solvent-Free Synthesis of Polyacrylamide by Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

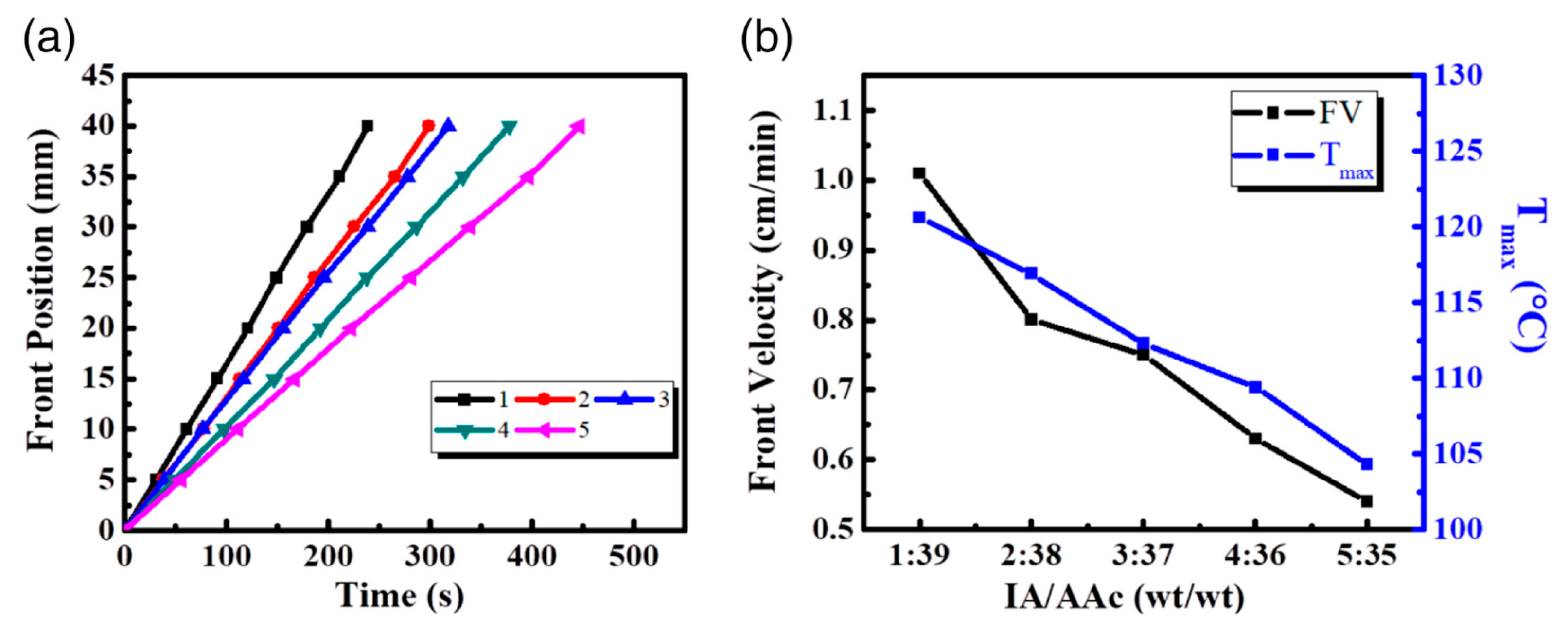

- Irfan, M.; Du, X.; Xu, X. R.; Shen, R. Q.; Chen, S.; Xiao, J. J. Synthesis and Characterization of PH-sensitive Poly(IA- Co -AAc- Co -AAm) Hydrogels via Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2019, 57, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Serrano, R. D.; Ugone, V.; Porcu, P.; Vonlanthen, M.; Sorroza-Martínez, K.; Cuétara-Guadarrama, F.; Illescas, J.; Zhu, X.-X.; Rivera, E. Novel Porphyrin-Containing Hydrogels Obtained by Frontal Polymerization: Synthesis, Characterization and Optical Properties. Polymer 2022, 247, 124785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qin, H.; Ma, M.; Xu, X.; Zhou, M.; Hao, W.; Hu, Z. Preparation of Novel β-CD/P(AA- Co -AM) Hydrogels by Frontal Polymerization. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 5667–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaiszik, B. J.; Kramer, S. L. B.; Olugebefola, S. C.; Moore, J. S.; Sottos, N. R.; White, S. R. Self-Healing Polymers and Composites. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2010, 40, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Han, Z.; Li, Q.; He, J.; Wang, Q. Self-Healing Polymers for Electronics and Energy Devices. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 558–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsch, P.; Diba, M.; Mooney, D. J.; Leeuwenburgh, S. C. G. Self-Healing Injectable Hydrogels for Tissue Regeneration. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 834–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebian, S.; Mehrali, M.; Taebnia, N.; Pennisi, C. P.; Kadumudi, F. B.; Foroughi, J.; Hasany, M.; Nikkhah, M.; Akbari, M.; Orive, G.; Dolatshahi-Pirouz, A. Self-Healing Hydrogels: The Next Paradigm Shift in Tissue Engineering? Adv. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Mao, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, G.; Shen, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, S. Rapid Synthesis of Biocompatible Bilayer Hydrogels via Frontal Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 2784–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Dai, C.; Weng, G. Fast Healing of Covalently Cross-Linked Polymeric Hydrogels by Interfacially Ignited Fast Gelation. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, A.; Hao, W.; Liu, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y. Preparation of SA/P(U-AM-ChCl) Composite Hydrogels by Frontal Polymerization and Its Performance Study. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 11530–11536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhou, M.; Cheng, M.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Xie, X. Rapid Preparation of ZnO Nanocomposite Hydrogels by Frontal Polymerization of a Ternary DES and Performance Study. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 12871–12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, B.; Wu, A.; Qin, H.; Xu, X.; Yan, S. Rapid Preparation of Liquid-free, Antifreeze, Stretchable, and Ion-conductive Eutectic Gels with Good Compression Resistance and Self-healing Properties by Frontal Polymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhou, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Hao, W.; Wu, A. Preparation and Properties of β-CD /P( AM- co -AA ) Composite Hydrogel by Frontal Polymerization of Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvent. Polym. Int. 2023, 72, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, H.-X.; Wang, C.-F.; Chen, S. Rapid Preparation of Superabsorbent Self-Healing Hydrogels by Frontal Polymerization. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Yan, S. Starch as a Reinforcement Agent for Poly(Ionic Liquid) Hydrogels from Deep Eutectic Solvent via Frontal Polymerization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 263, 117996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, P. Rapid Preparation of N-CNTs/P(AA- Co -AM) Composite Hydrogel via Frontal Polymerization and Its Mechanical and Conductive Properties. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 19022–19028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Xie, A.-Q.; Mao, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, S. Solar-Initiated Frontal Polymerization of Photothermic Hydrogels with High Swelling Properties for Efficient Water Evaporation. Sol. RRL 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chechilo, N. M.; Khvilivitskii, R. J.; Enikolopyan, N. S. On the Phenomenon of Polymerization Reaction Spreading. Dokl. Akad. Nauk 1972, 204, 1180–1181. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).