Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background/Rationale

1.2. Objectives

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Ethics Approval

3.3. Setting

3.4. Participants

3.5. Variables

3.6. Data sources/Measurement

3.7. Bias

3.8. Study Size

3.9. Quantitative Variables

3.10. Statistical Methods

4. Results

4.1. Summary of the Characteristics of the Patients with a First Admission 2013-2021 Admitted to the Four Acute Care Hospitals in Calgary

4.2. Numbers of Patient Admissions to the Four Acute care Calgary Hospitals 2013-2021

4.3. Numbers of Admissions, Readmissions, Length of Stay, and Death in Hospital and in the Next Six Months

4.4. Principal Diagnoses for Admissions 1 through 39, and also Annually for Each Year 2013-2021

4.5. The numbers of Medications Pre-Admission and on Discharge for all Admissions

4.6. Class and Numbers of Medications Prescribed: All Admissions 2013-2021

4.7. Costs of Admissions 2013-2021 Measured by Resource Intensity Weighting

4.8. Correlations with Readmissions and Mortality 2013-2021

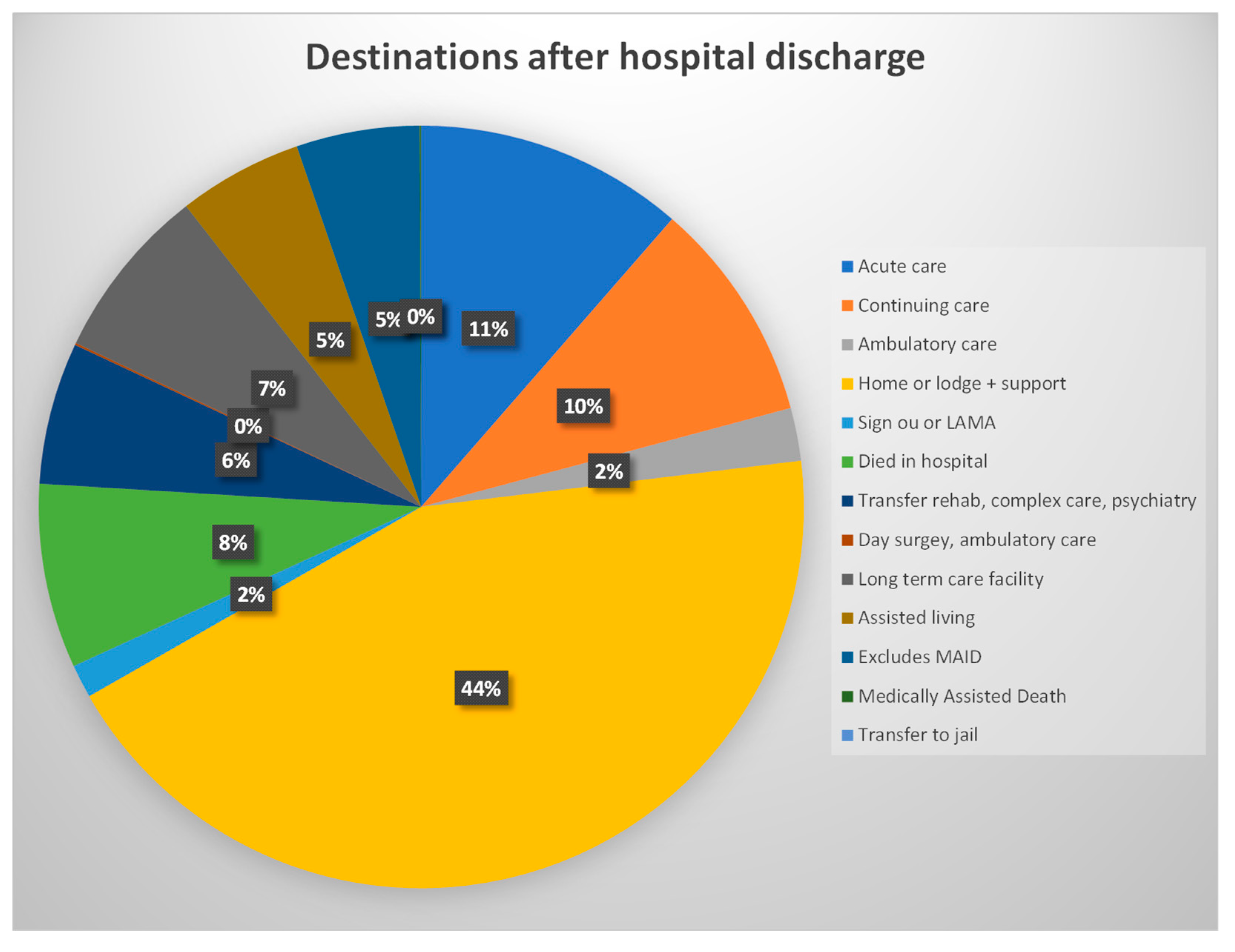

4.9. Destination after Discharge from the Four Calgary Acute Care Hospitals 2013-20221

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Results

5.2. Admission Costs

5.3. Previous Studies of Interventions to Reduce PIMs, PPOs and Admission Costs

5.4. Strengths

5.5. Weaknesses

5.5. Generalisability

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomas, R.E.; Thomas, B.C. A Systematic Review of Studies of the STOPP/START 2015 and American Geriatric Society Beers 2015 Criteria in Patients >= 65 Years. Current Aging Science. 2019, 12, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Byrne, S.; O’Connor, M.M.; Ryan, C.; Gallagher, P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inapprpriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015, 44, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Geng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Hesketh, T. Effectiveness of integrating primary healthcare n aftercare for older patients after discharge from tertiary hospitals – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and Ageing 2022, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visade, F.; Babykina, G.; Lamer, A.; Defebvre, M.-M.; Verloop, D.; Ficheur, G.; Genin, M.; Puisieux, F.; Beuscart, J.-F. Importance of previous hospital stays on the risk of hospital re-admission in older adults: a real-life analysis of the PAERPA study population. Age & Ageing. 50, 141-146. [CrossRef]

- Visade FBabykina, G.; Puisieux, F.; Bloch, F.; Charpentier, A.; Delecluse, C.; Loggia, G.; Lescure, P.; Attier-Żmudka, J.; Gaxatte, C.; Deschasse, G.; Beuscart, J.-B. Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission and Death After Discharge of Older Adults from Acute Geriatric Units: Taking the Rank of Admission into Account. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2021, 16, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornette, P.; Swine CMalhomme, B.; Gillet, J.-B.; Meert, P.; D’Hoore, W. Early evaluation of the risk of functional decline following hospitalization of older patients: development of a predictive tool. European Journal of Public Health. 2006, 16, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.; Kerse, N. Medical readmissions amongst older New Zealanders: a descriptive analysis. N Z Med J 2012, 125, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kutz, A.; Gut, L.; Ebrahimi, F.; Wagner, U.; Schuetz, P.; Mueller, B. Association of the Swiss diagnosis-related group reimbursement system, with length of stay, mortality, and readmission rates in hospitalized adult patients. JAMA Network Open 2019, 2, e188332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaguru, V.; Han, W.; Kim, T.H.; Shin, J.; Lee, S.G. LACE Index to Predict the High Risk of 30-Day Readmission: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.K.; Meyer, G.; Uhrenfeldt, L. Risk factors for acute care hospital readmission in older persons in Western countries: a systematic review. JBI Database Of Systematic Reviews And Implementation Reports. 2017, 15, 454–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanièce, I; Couturier, P. ; Dramé, M.; Gavazzi, G.; Lehman S.; Jolly D. et al. Incidence and main factors associated with early unplanned hospital readmission among French medical inpatients aged 75 and over admitted through emergency units. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espallargues, M.; Philp, I.; Seymour, D.G.; Campbell, S.E.; Primrose, W.; Arino, S. Measuring case-mix and outcome for older people in acute hospital care across Europe: the development and potential of the ACMEplus instrument. QJM 2008, 101, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute of Health Information. Resource Indicators: DAD Resource Intensity Weights And Expected Length Of Stay. https://www.cihi.ca/en/resource-indicators-dad-resource-intensity-weights-and-expected-length-of-stay0. Canadian Institute of Health Information https://www.cihi.ca/en/indicators/cost-of-a-standard-hospital-stay (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Canadian Institute of Health Information Available online:. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/resource-indicators-dad-resource-intensity-weights-and-expected-length-of-stay (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Leppin, A.L.; Gionfriddo, M.R.; Kessler, M.; Brito, J.P.; Mair, F.S.; Gallacher, K. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014, 174, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, A.M.; Valentijn, P.P.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Araujo de Carvalho, I. Elements of integrated care approaches for older people: a review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2018, 7, e021194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foot, H.; Scott, I.; Sturman, N.; Whitty, J.A.; Rixon, K.; Connelly, L.; Williams, I.; Freeman, C. Impact of pharmacist and physician collaborations in primary care on reducing readmission to hospital: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in social & administrative pharmacy 2022, 18, 2922–2943. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy, I.; Robinson, K.; O’Connor, M.; Conneely, M.; Ryan, D.; Steed, F.; Carey, L.; Leahy, A.; Shanahan, E.; Quinn, C.; Galvin, R. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care on functional decline, clinical and process outcomes among hospitalised older adults with acute medical complaints: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age & Ageing. 51, S1, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, W.N.; Ho, M.J.; Bullers, K.; Klocksieben, F.; Kumar, A. Association of pharmacist counseling with adherence, 30-day readmission, and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAPhA. 2021, 61, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaudin, P.; Boyer, L.; Esteve, M.-E.; Bertault-Peres, P.; Auquier, P.; Honore, D. Do pharmacist-led medication reviews in hospitals help reduce hospital readmissions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 1660–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbietti, P.; Di Stefano, G.; Moresi, R.; Cassetta, L.; Di Rosa, M.; Fimognari, F.; Bambara, V.; Ruotolo, G.; Castagna, A.; Ruberto, C.; Lattanzio, F.; Corsonello, A. Impact of potentially inappropriate medications and polypharmacy on 3-month readmission among older patients discharged from acute care hospital: a prospective study. Aging Clin Exp Res. [CrossRef]

- Counter, D.; Millar, J.W.T.; McLay, J.S. Hospital Readmissions, Mortality and Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing: A Retrospective Study of Older Adults Discharged From Hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.E. Improving the Care of Older Patients by Decreasing Potentially Inappropriate Medications, Potential Medication Omissions, and Serious Drug Events Using Pharmacogenomic Data about Variability in Metabolizing Many Medications by Seniors. Geriatrics 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.E. Optimising Seniors’ Metabolism of Medications and Avoiding Adverse Drug Events Using Data on How Metabolism by Their P450 Enzymes Varies with Ancestry and Drug–Drug and Drug–Drug–Gene Interactions. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2020, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Both Genders | Female | Male | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 129443 (100%) | 64621(49.92%) | 64822(50.08%) | |

| Age group at first admission | ||||

| 65-69 | 45244(27.39%) | 20500(15.84%) | 24744 (19.12%) | |

| 70-74 | 26042(20.09) | 12409 (9.59%) | 13633(10.53%) | |

| 75-79 | 21526((17.78%) | 10750(8.30%) | 10766 (8.32%) | |

| 80-84 | 18125(16.11%) | 9647 (7.45%) | 8478 (6.55%) | |

| 85-89 | 12138(11.93%) | 7027(5.43%) | 5111(3.95%) | |

| 90+ | 6368 (6.68%) | 4288 (3.31%) | 2080(1.61%) | |

| Total Visits 285201 | ||||

| For entire data set | ||||

| Median Age | 76 | 77 | 75 | |

| IQR (Age) | 13 | 14 | 13 | |

| Medicines upon admission | ||||

| Median | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| IQR | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Maximum | 24 | 23 | 24 | |

| Medicines upon discharge | ||||

| Median | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| IQR | 7 | 7 | 6 | |

| Readmission | 82524(28.93%) | 38953 (13.65%) | 43571 (15.27%) | |

| Mortality | 41479 (14.54%) | 19554 (6.85%) | 21925 (7.68%) | |

| Admission no |

Number of patients | Admission no |

Number of patients | Admission no |

Number of patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | ||||

| 1 | 64622 | 64821 | 129443 | 14 | 214 | 200 | 414 | 27 | 8 | 9 | 17 | |

| 2 | 31714 | 32727 | 64441 | 15 | 166 | 152 | 318 | 28 | 7 | 8 | 15 | |

| 3 | 17154 | 18052 | 35206 | 16 | 106 | 108 | 214 | 29 | 7 | 8 | 13 | |

| 4 | 9809 | 10545 | 20354 | 17 | 80 | 79 | 159 | 30 | 7 | 5 | 12 | |

| 5 | 5820 | 6451 | 12271 | 18 | 56 | 61 | 117 | 31 | 6 | 4 | 10 | |

| 6 | 3540 | 4037 | 7577 | 19 | 49 | 52 | 101 | 32 | 5 | 3 | 8 | |

| 7 | 2338 | 2577 | 4915 | 20 | 33 | 44 | 77 | 33 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| 8 | 1524 | 1726 | 3250 | 21 | 21 | 31 | 52 | 34 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| 9 | 1034 | 1131 | 2165 | 22 | 16 | 22 | 38 | 35 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 10 | 717 | 777 | 1494 | 23 | 13 | 17 | 30 | 36 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 11 | 534 | 551 | 1085 | 24 | 13 | 17 | 30 | 37 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 12 | 379 | 378 | 757 | 25 | 11 | 14 | 25 | 38 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 13 | 271 | 282 | 553 | 26 | 8 | 11 | 19 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| TOTAL | 140,293 | 144,908 | 285201 | |||||||||

| Admi ssion |

Patients | Mort ality in hospital |

% died in hospital | Read mitted within 6 months |

% read mitted within 6 months |

Died within 6 months | % died within 6 months | Average stay (days) | Relative risk of read mission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 129443 | 3919 | 3.03% | 28292 | 21.9% | 12144 | 9.4% | 9.8 | |

| 2 | 64441 | 2947 | 4.57% | 18157 | 28.2% | 9427 | 14.6% | 11.6 | 49.8% |

| 3 | 35206 | 2049 | 5.82% | 11585 | 32.9% | 6500 | 18.5% | 12.6 | 54.6% |

| 4 | 20354 | 1414 | 6.45% | 7576 | 37.2% | 4450 | 21.9% | 13.2 | 57.8% |

| 5 | 12271 | 885 | 7.21% | 4982 | 40.6% | 2948 | 24% | 13.8 | 60.3% |

| 6 | 7577 | 546 | 7.21% | 3422 | 45.2% | 1882 | 24.9% | 13 | 61.8% |

| 7-39 | 15909 | 1200 | 7.54% | 8510 | 53.5% | 4128 | 26% | 11.7 | 65-100% |

| Risk factor. | Readmission within 6 months | Mortality within 6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted ORs and 95%CIs | |||||||

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | ||

| Gender | 1.12 | 1.10-1.14 | <.001 | 1.10 | 1.08-1.12 | <.001 | |

| Age at admission | 1.01 | 1.01-1.01 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.07-1.07 | <.001 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.01 | 1.01-1.01 | <.001 | 1.19 | 1.18-1.19 | <.001 | |

| Post admission Rx number | 1.05 | 1.04-1.05 | <.001 | 1.19 | 1.18-1.19 | <.001 | |

| Total STOPP PIMs | 1.17 | 1.17-1.17 | <.001 | 1.04 | 1.03-1.04 | <.001 | |

| START Omissions not corrected | 1.58 | 1.55-1.61 | <.001 | 2.16 | 2.11-2.21 | <.001 | |

| START Omissions correctly prescribed | 1.50 | 1.47-1.52 | <.001 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | .189 | |

| AGS Beers PIMs | 1.11 | 1.1-1.12 | <.001 | 1.09 | 1.09-1.10 | <.001 | |

| Charlson Index | 1.09 | 1.08-1.09 | <.001 | 1.43 | 1.42-1.43 | <.001 | |

| ORs and 95%CIs adjusted for age at admission, gender (male) and comorbidities | |||||||

| Risk factor | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Post admission Rx number | 1.12 | 1.12-1.12 | <.001 | 1.04 | 1.04-1.05 | <.001 | |

| Total STOPP PIMs | 1.16 | 1.15-1.16 | <.001 | 0.99 | 0.96-1.00 | <.001 | |

| START Omissions not corrected | 1.39 | 1.35-1.42 | <.001 | 1.56 | 1.50-1.63 | <.001 | |

| START Omissions correctly prescribed | 1.26 | 1.23-1.30 | <.001 | 0.51 | 0.49-0.53 | <.001 | |

| AGS Beers PIMs | 1.11 | 1.11-1.11 | <.001 | 1.08 | 1.07-1.08 | <.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).