Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

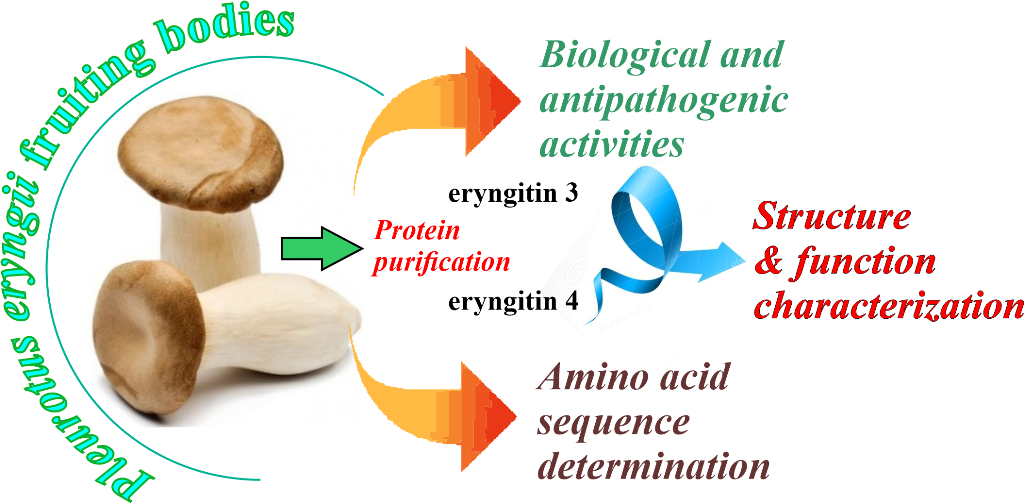

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Purification of eryngitin 3 and 4

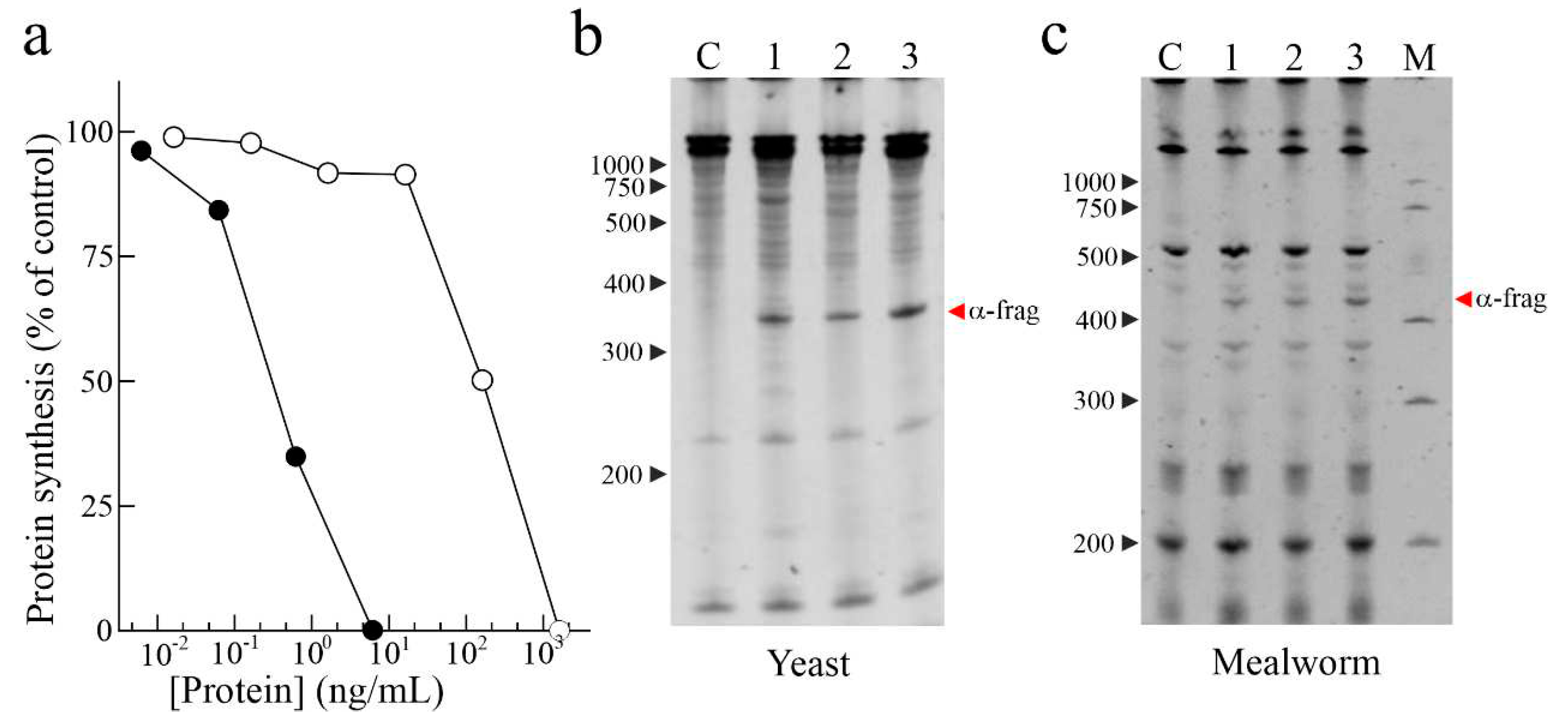

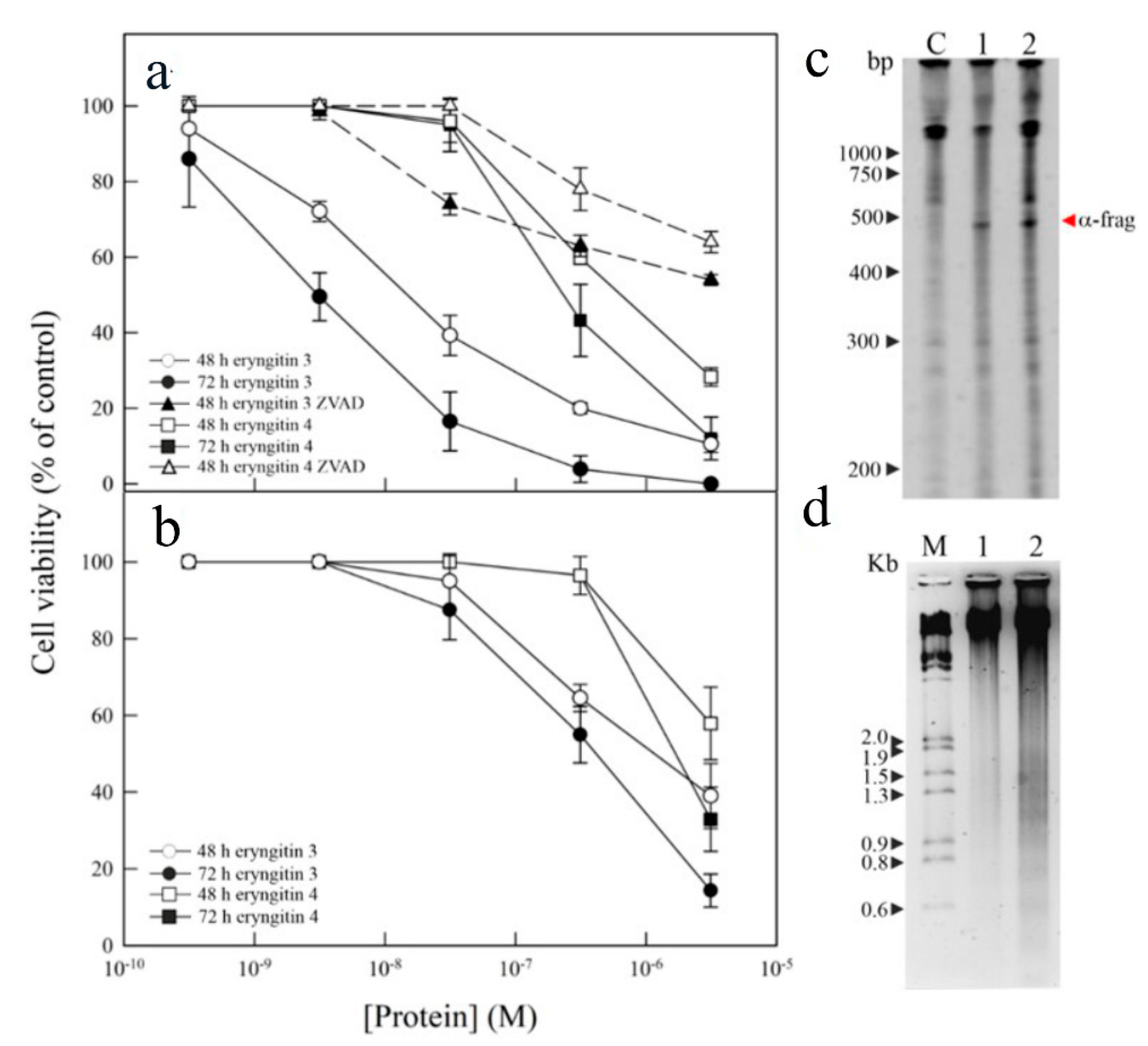

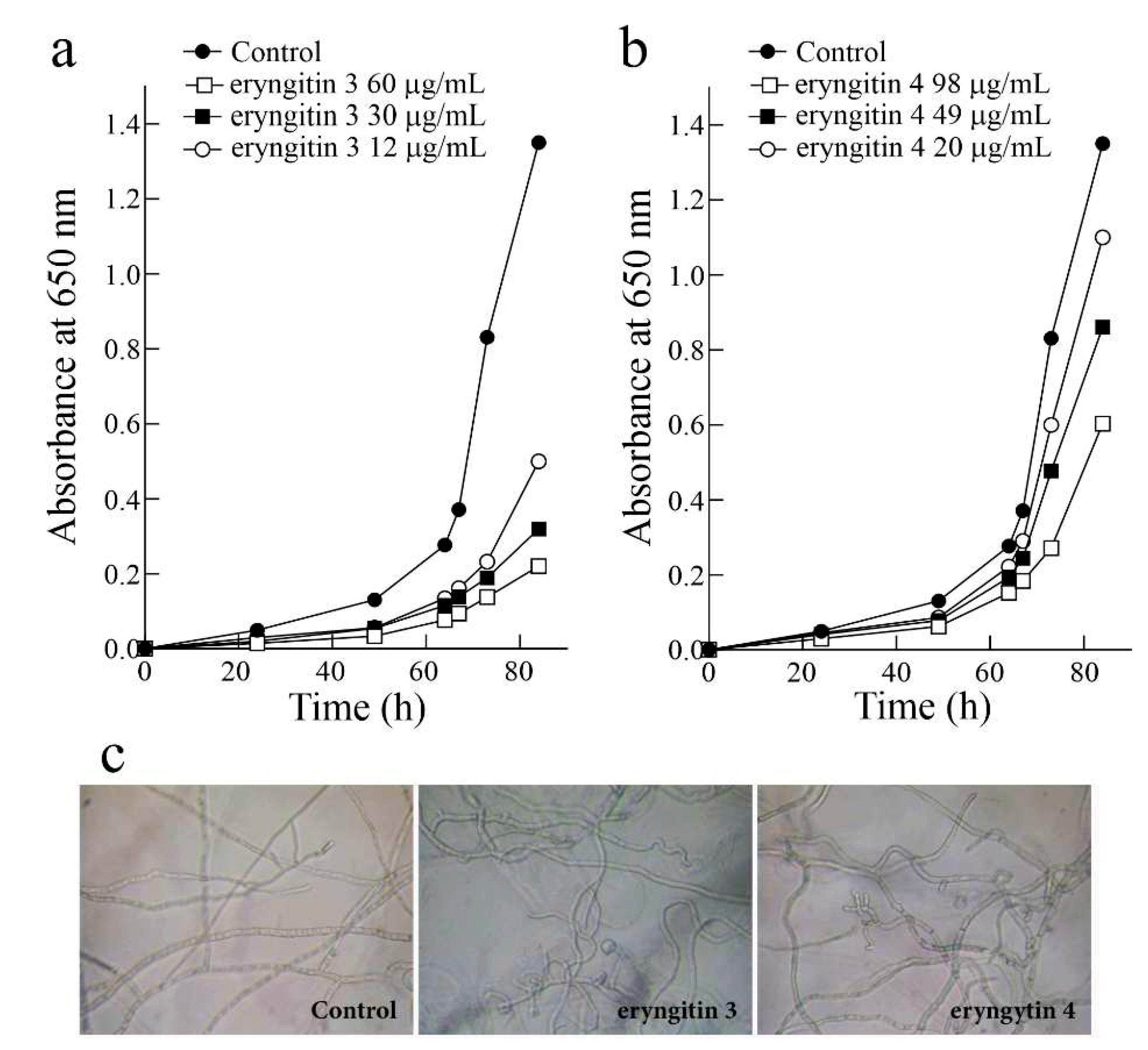

2.2. Assessment of biological and antipathogenic activities of eryngitin 3 and 4

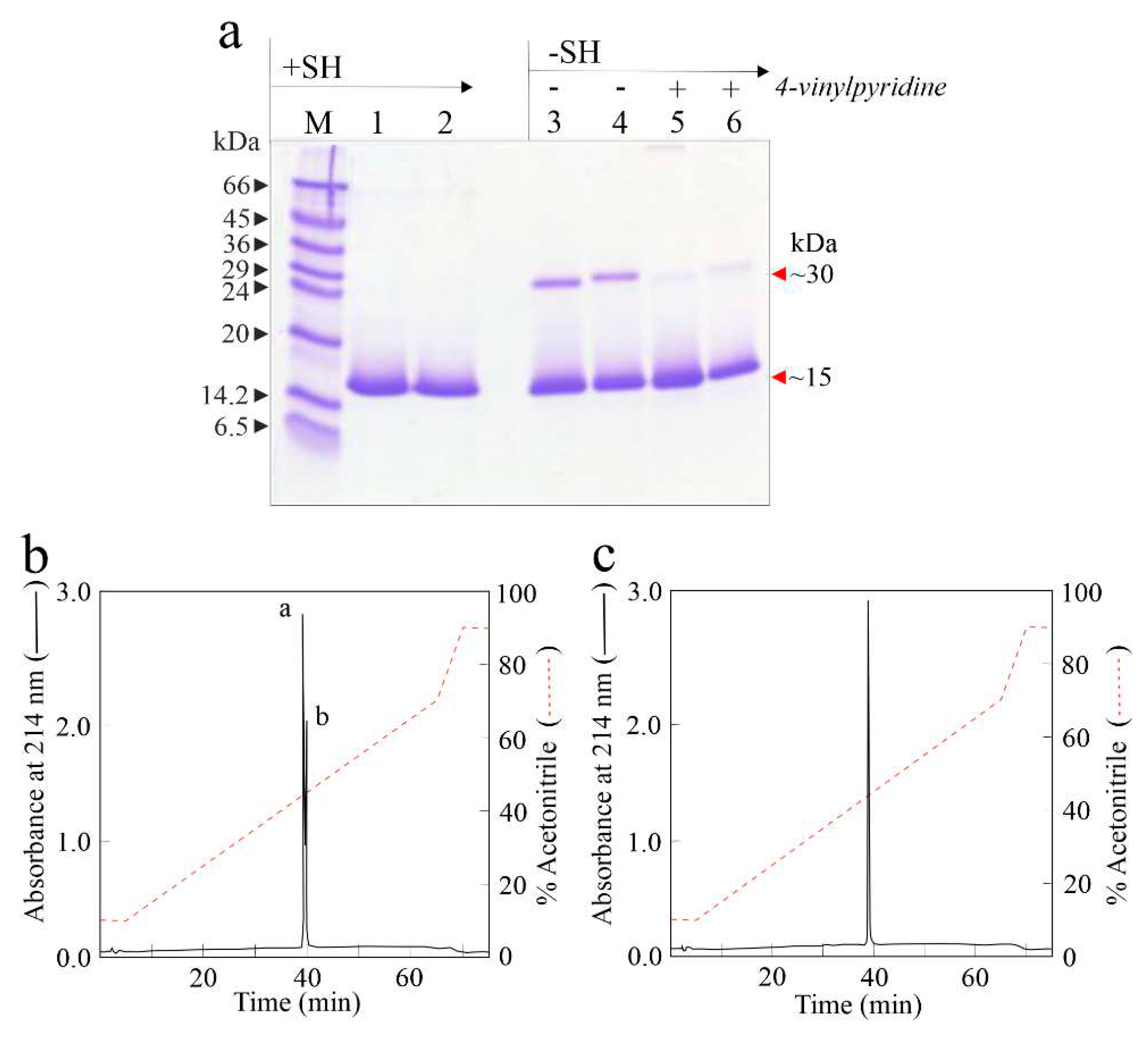

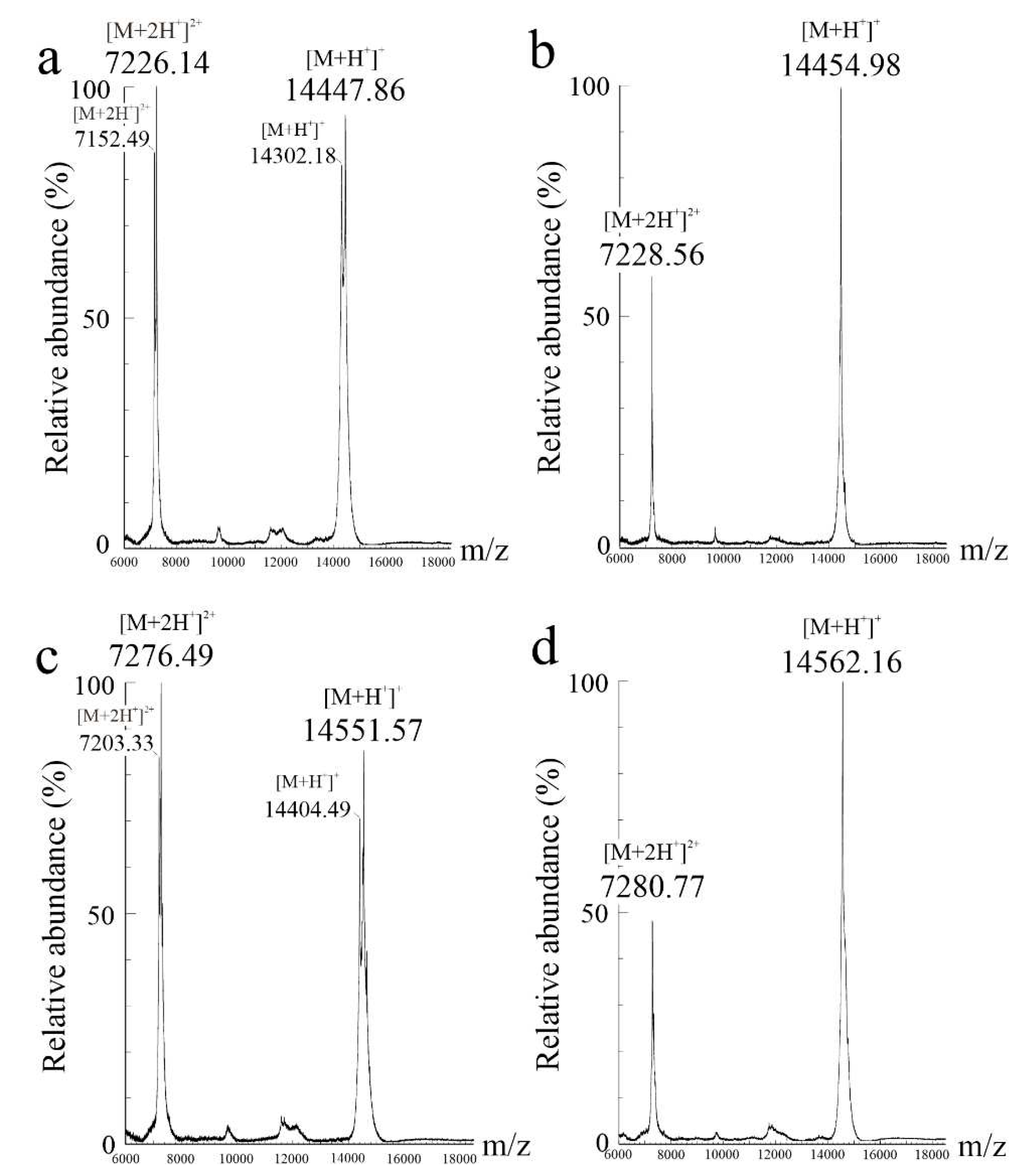

2.3. Relative molecular masses of eryngitin 3 and 4 with and without alkylation

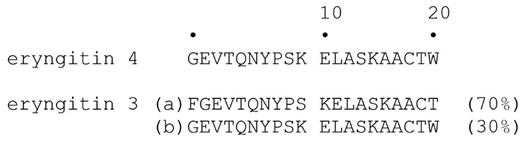

2.4. N-terminal amino acid determination and search in fungal data base genome

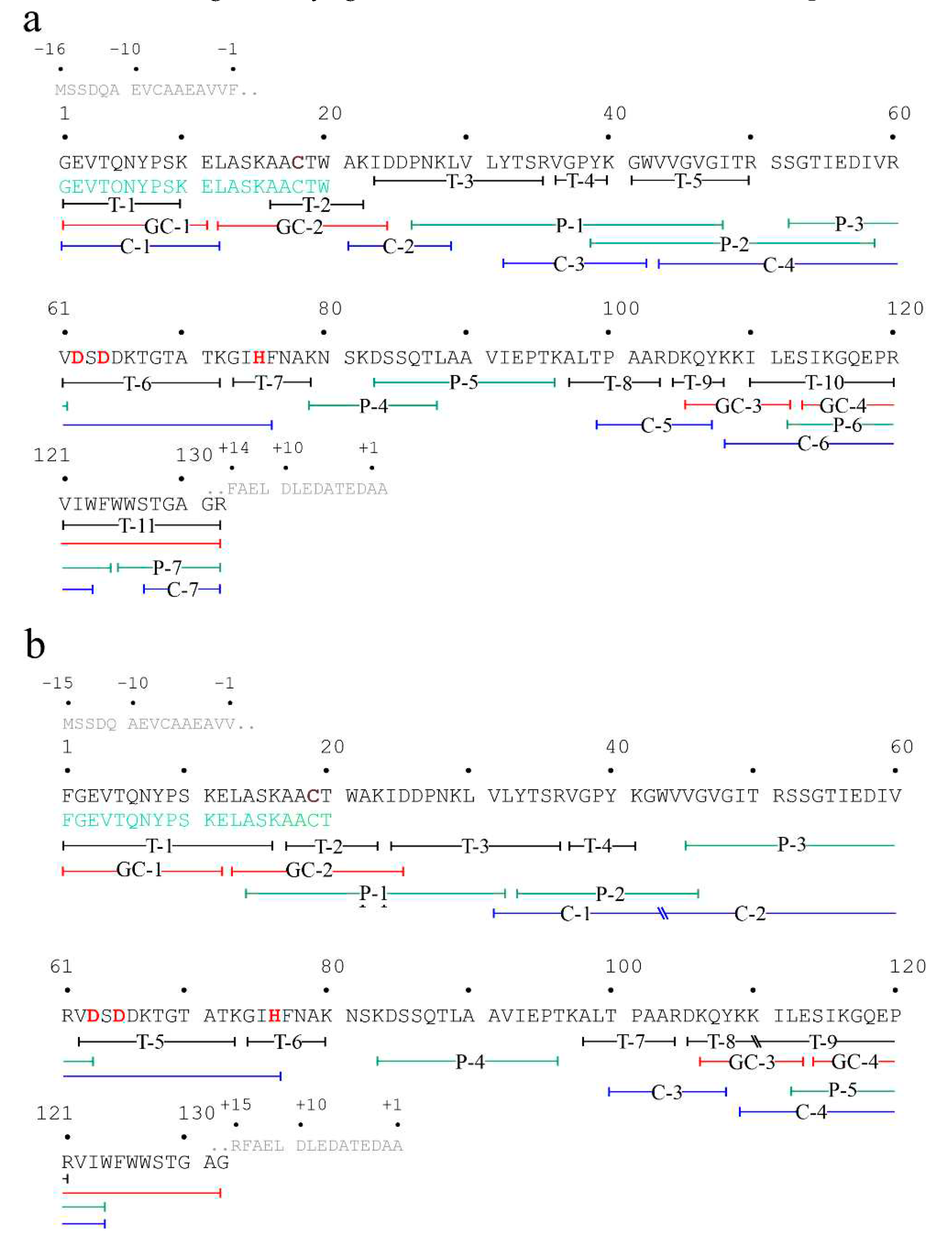

2.5. Determination of eryngitin 4 amino acid sequence

2.6. Determination of eryngitin 3 amino acid sequence

2.7. Features of eryngitin 3 and 4 gene

2.8. Sequence comparison between eryngitin 3 and 4 and other well-characterized RL-Ps

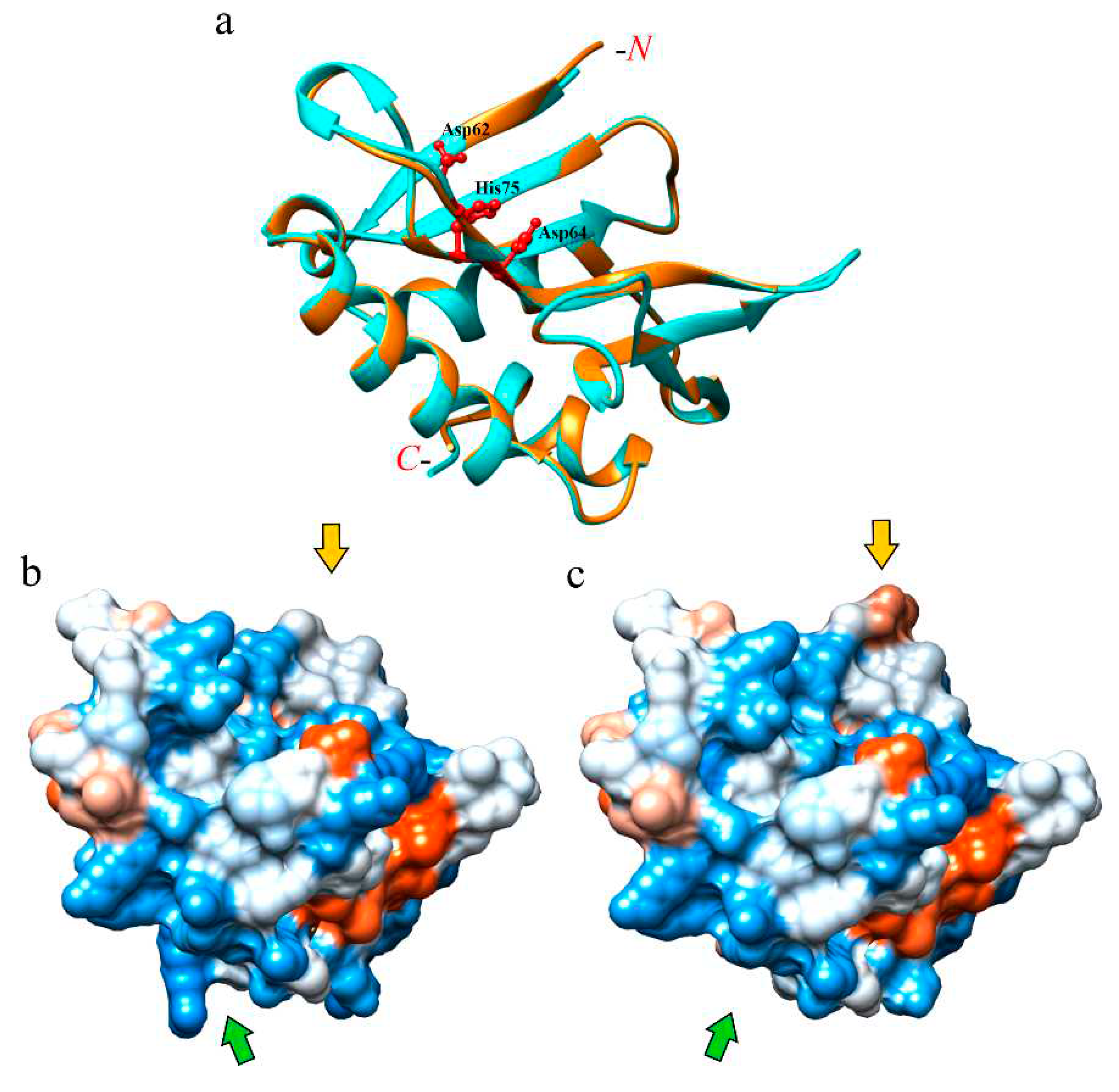

2.9. Modeling the 3D structure of eryngitin 4 and 3

3. Conclusions

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and reagents

4.2. Proteins purification

4.3. Analytical procedures

4.4. Assays of cell-free protein synthesis

4.5. Ribonucleolytic activity on yeast and mealworm ribosomes

4.6. Cell viability assays

4.7. RNA extraction from HeLa cells

4.8. DNA fragmentation analysis

4.9. Antifungal activity

4.10. Reduction and S-pyridylethylation

4.11. Automatic N-terminal Edman degradation

4.12. Protein digestion for MALDI-ToF analysis

4.13. MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry analyses

4.14. Sequence analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landi, N.; Pacifico, S.; Ragucci, S.; Iglesias, R.; Piccolella, S.; Amici, A.; Di Giuseppe, A.M.A.; Di Maro, A. Purification, characterization and cytotoxicity assessment of Ageritin: The first ribotoxin from the basidiomycete mushroom Agrocybe aegerita. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragucci, S.; Landi, N.; Russo, R.; Valletta, M.; Pedone, P.V.; Chambery, A.; Di Maro, A. Ageritin from Pioppino Mushroom: The Prototype of Ribotoxin-Like Proteins, a Novel Family of Specific Ribonucleases in Edible Mushrooms. Toxins (Basel) 2021, 13, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Huber, P.W.; Wool, I.G. The ribonuclease activity of the cytotoxin alpha-sarcin. The characteristics of the enzymatic activity of alpha-sarcin with ribosomes and ribonucleic acids as substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 2662–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, N.; Ragucci, S.; Culurciello, R.; Russo, R.; Valletta, M.; Pedone, P.V.; Pizzo, E.; Di Maro, A. Ribotoxin-like proteins from Boletus edulis: structural properties, cytotoxicity and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragucci, S.; Hussain, H.Z.F.; Bosso, A.; Landi, N.; Clemente, A.; Pedone, P.V.; Pizzo, E.; Di Maro, A. Isolation, Characterization, and Biocompatibility of Bisporitin, a Ribotoxin-like Protein from White Button Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Biomolecules 2023, 13, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, N.; Ragucci, S.; Russo, R.; Valletta, M.; Pizzo, E.; Ferreras, J.M.; Di Maro, A. The ribotoxin-like protein Ostreatin from Pleurotus ostreatus fruiting bodies: Confirmation of a novel ribonuclease family expressed in basidiomycetes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, N.; Grundner, M.; Ragucci, S.; Pavšič, M.; Mravinec, M.; Pedone, P.V.; Sepčić, K.; Di Maro, A. Characterization and cytotoxic activity of ribotoxin-like proteins from the edible mushroom Pleurotus eryngii. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, R. A review on nutritional advantages of edible mushrooms and its industrialization development situation in protein meat analogues. J. Future Foods 2023, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; García-Ortega, L.; Moreira, M.; Ragucci, S.; Landi, N.; Di Maro, A.; Berisio, R. Binding and enzymatic properties of Ageritin, a fungal ribotoxin with novel zinc-dependent function. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 136, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyrov, A.; Azevedo, S.; Herzog, R.; Vogt, E.; Arzt, S.; Lüthy, P.; Müller, P.; Rühl, M.; Hennicke, F.; Künzler, M. Heterologous Production and Functional Characterization of Ageritin, a Novel Type of Ribotoxin Highly Expressed during Fruiting of the Edible Mushroom Agrocybe aegerita. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01549–e01519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampitella, E.; Landi, N.; Oliva, R.; Ragucci, S.; Petraccone, L.; Berisio, R.; Di Maro, A.; Del Vecchio, P. Conformational stability of ageritin, a metal binding ribotoxin-like protein of fungal origin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, M.C.; Möller, W. Structure and function of the acidic ribosomal stalk proteins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2002, 3, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, S.; Kumar, V.; Ero, R.; Gao, Y.-G. Structure of EF-G–ribosome complex in a pretranslocation state. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirpe, F. Ribosome-inactivating proteins: from toxins to useful proteins. Toxicon 2013, 67, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, P.; Szajwaj, M.; Horbowicz-Drożdżal, P.; Tchórzewski, M. How Ricin Damages the Ribosome. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.; Wiels, J. Shiga Toxins as Antitumor Tools. Toxins (Basel) 2021, 13, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.J.; Davis, S.A.; Tumer, N.E.; Li, X.P. Structural basis for the interaction of Shiga toxin 2a with a C-terminal peptide of ribosomal P stalk proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15588–15596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacadena, J.; Alvarez-García, E.; Carreras-Sangrà, N.; Herrero-Galán, E.; Alegre-Cebollada, J.; García-Ortega, L.; Oñaderra, M.; Gavilanes, J.G.; Martínez del Pozo, A. Fungal ribotoxins: molecular dissection of a family of natural killers. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 31, 212–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Galán, E.; García, E.; Carreras-Sangrà, N.; Lacadena, J.; Alegre-Cebollada, J.; Martínez-del-Pozo, A.; Oñaderra, M.; Gavilanes, J. Fungal ribotoxins: structure, function and evolution. In Microbial Toxins: Current Research and Future Trends., Proft, T., Ed. Caister Academic Press,: Norfolk, UK, 2009; pp. 167–187.

- Choi, A.K.; Wong, E.C.; Lee, K.M.; Wong, K.B. Structures of eukaryotic ribosomal stalk proteins and its complex with trichosanthin, and their implications in recruiting ribosome-inactivating proteins to the ribosomes. Toxins (Basel) 2015, 7, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citores, L.; Ragucci, S.; Ferreras, J.M.; Di Maro, A.; Iglesias, R. Ageritin, a Ribotoxin from Poplar Mushroom (Agrocybe aegerita) with Defensive and Antiproliferative Activities. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragucci, S.; Landi, N.; Russo, R.; Valletta, M.; Citores, L.; Iglesias, R.; Pedone, P.V.; Pizzo, E.; Di Maro, A. Effect of an additional N-terminal methionyl residue on enzymatic and antifungal activities of Ageritin purified from Agrocybe aegerita fruiting bodies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, N.; Ragucci, S.; Russo, R.; Pedone, P.V.; Chambery, A.; Di Maro, A. Structural insights into nucleotide and protein sequence of Ageritin: a novel prototype of fungal ribotoxin. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2019, 165, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivo, I.; Ragucci, S.; D'Incecco, P.; Landi, N.; Russo, R.; Faoro, F.; Pedone, P.V.; Di Maro, A. Gene Organization, Expression, and Localization of Ribotoxin-Like Protein Ageritin in Fruiting Body and Mycelium of Agrocybe aegerita. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7158–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, R.; Citores, L.; Ragucci, S.; Russo, R.; Di Maro, A.; Ferreras, J.M. Biological and antipathogenic activities of ribosome-inactivating proteins from Phytolacca dioica L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citores, L.; Iglesias, R.; Ragucci, S.; Di Maro, A.; Ferreras, J.M. Antifungal Activity of α-Sarcin against Penicillium digitatum: Proposal of a New Role for Fungal Ribotoxins. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sui, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Wang, Q. Biological control of postharvest fungal decays in citrus: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Application of the S-pyridylethylation reaction to the elucidation of the structures and functions of proteins. J. Protein Chem. 2001, 20, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, I.V.; Nikitin, R.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Ohm, R.; Otillar, R.; Riley, R.; Salamov, A.; Zhao, X.; Korzeniewski, F. , et al. MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D699–D704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maro, A.; Chambery, A.; Carafa, V.; Costantini, S.; Colonna, G.; Parente, A. Structural characterization and comparative modeling of PD-Ls 1-3, type 1 ribosome-inactivating proteins from summer leaves of Phytolacca dioica L. Biochimie 2009, 91, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Dueñas, F.J.; Barrasa, J.M.; Sánchez-García, M.; Camarero, S.; Miyauchi, S.; Serrano, A.; Linde, D.; Babiker, R.; Drula, E.; Ayuso-Fernández, I. , et al. Genomic Analysis Enlightens Agaricales Lifestyle Evolution and Increasing Peroxidase Diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G. A Brief History of Protein Sorting Prediction. Protein J. 2019, 38, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupfer, D.M.; Drabenstot, S.D.; Buchanan, K.L.; Lai, H.; Zhu, H.; Dyer, D.W.; Roe, B.A.; Murphy, J.W. Introns and splicing elements of five diverse fungi. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, V.; Biasini, M.; Barbato, A.; Schwede, T. lDDT: a local superposition-free score for comparing protein structures and models using distance difference tests. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2722–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, P.K. Enzymes: An integrated view of structure, dynamics and function. Microb. Cell Fact. 2006, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumer, N.E.; Li, X.P. Interaction of ricin and Shiga toxins with ribosomes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 357, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, A.J.; Bolewska-Pedyczak, E.; Jarvik, N.; Chen, G.; Sidhu, S.S.; Gariépy, J. Charged and hydrophobic surfaces on the a chain of shiga-like toxin 1 recognize the C-terminal domain of ribosomal stalk proteins. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cañadillas, J.M.; Santoro, J.; Campos-Olivas, R.; Lacadena, J.; Martínez del Pozo, A.; Gavilanes, J.G.; Rico, M.; Bruix, M. The highly refined solution structure of the cytotoxic ribonuclease alpha-sarcin reveals the structural requirements for substrate recognition and ribonucleolytic activity. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 299, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.W.; Mak, A.N.; Wong, K.B.; Shaw, P.C. Structures and Ribosomal Interaction of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins. Molecules 2016, 21, 1588–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlünzen, F.; Wilson, D.N.; Tian, P.; Harms, J.M.; McInnes, S.J.; Hansen, H.A.; Albrecht, R.; Buerger, J.; Wilbanks, S.M.; Fucini, P. The binding mode of the trigger factor on the ribosome: implications for protein folding and SRP interaction. Structure 2005, 13, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, M.; Kothe, U.; Schlünzen, F.; Fischer, N.; Harms, J.M.; Tonevitsky, A.G.; Stark, H.; Rodnina, M.V.; Wahl, M.C. Structural basis for the function of the ribosomal L7/12 stalk in factor binding and GTPase activation. Cell 2005, 121, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljas, A.; Sanyal, S. The enigmatic ribosomal stalk. Q Rev. Biophys. 2018, 51, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, R.; Russo, R.; Landi, N.; Valletta, M.; Chambery, A.; Di Maro, A.; Bolognesi, A.; Ferreras, J.M.; Citores, L. Structure and Biological Properties of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins and Lectins from Elder (Sambucus nigra L.) Leaves. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, R.; Citores, L.; Ferreras, J.M. Ribosomal RNA N-glycosylase Activity Assay of Ribosome-inactivating Proteins. Bio Protoc. 2017, 7, e2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citores, L.; Ragucci, S.; Russo, R.; Gay, C.C.; Chambery, A.; Di Maro, A.; Iglesias, R.; Ferreras, J.M. Structural and functional characterization of the cytotoxic protein ledodin, an atypical ribosome-inactivating protein from shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes). Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maro, A.; Ferranti, P.; Mastronicola, M.; Polito, L.; Bolognesi, A.; Stirpe, F.; Malorni, A.; Parente, A. Reliable sequence determination of ribosome- inactivating proteins by combining electrospray mass spectrometry and Edman degradation. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 36, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, B. ; Springer-Verlag Springer Science & Business Media, 2012; pp. 335.

- Walker, V.; Taylor, W.H. Ovalbumin digestion by human pepsins 1, 3 and 5. Biochem. J. 1978, 176, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A. , et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera -a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).