1. Introduction

Pharmacological giants are in search of new molecules as an alternative source of therapeutic drugs [

1]. Natural compounds possess various biological activities and have been applied for a long time to pharmaceutical area. Indeed, unlike conventional synthetic drugs that only modulate single targets, naturel molecules are often characterized as multi-component and multi-functional to treat diseases, which might be more effective due to possible synergistic actions [

2]. Recently, marine algae have considered as a new source for bioactive compounds [

3]. Polysaccharides are the most macromolecules produced by algae [

4,

5]. Similar to that of polynucleotides and proteins, polysaccharides play key roles in life activities such as, fertilization, signal recognition, cell communication and adhesion, blood clotting, pathogenesis prevention, and system development [

6,

7,

8]. Recently, pharmacological reports shown that polysaccharides isolated from algae have a various pharmacological activities, including immunomodulation, antitumor, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacities [7-8]. The biological capacities of polysaccharides are probably related with the presence and positions of sulfate groups. The macromolecules have different levels of spatial organizations, including primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures. Their primary structures can affect the various properties of polysaccharides, like their water-solubility, gel viscosity and biological functions [

9]. Functional polysaccharides could prevent the oxidative stress proveked by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Generally, ROS amounts generated by cellular metabolism can be scavenged by the endogenous antioxidant system [

10]. However, excessive environmental stresses, like ultraviolet irradiation and toxic chemicals, such as pesticides, can cause an abnormal ROS production, which leads to oxidative stress.

Tebuconazole (TBZ) is an effective fungicide used for the control of mildew and rust on wheat, barley, rice, fruits and vegetables [

11]. A long-term, it was one kind of toxicant for the marine organisms as it might induce an adverse effect on the aquatic environment [

12]. Animals were sensitive to the influence of TBZ because they were able to uptake and retain xenobiotic from circumstance via active or passive processes. TBZ has been proved that it could provoke adrenal gland hypertrophy in chronic dog studies and teratogenic effects in mice. Sancho et al. [

13] showed that short-term exposure to TBZ induced physiological impairment and endocrine reproduction perturbation in male zebrafish. Additionally, TBZ is deemed to cause hepatic and reproductive damage by inducing lipid peroxidation, decreasing of antioxidant enzymes activities and release of free radicals [

12,

13].

To date, no investigation has been carried out on biological activities of polysaccharides obtained from A. corallinum. The present study attempts to view the bioactivities of ACPs and investigate their application in fields of pharmacology via its effects on the hepatic system and lipidimic profile of TBZ-treated rats. Identification of ACPs in vitro is necessary to better effectively understand its structural and functional properties and antioxidant potential. Furthermore, the binding affinities and molecular interactions of ACPs with TyrRS from S. aureus (1JIJ), human peroxiredoxin (1HD2), and Acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT, 1WL4) were assessed using computational modeling.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Extraction yield and physicochemical analysis of ACPs

The yield and chemical analysis of polysaccharides isolated from the alga

Alsidium corallinum are reported in

Table 1.

ACPs extraction yield was measured based on the wet weight of

A. corallinum powder. The yield percent of ACPs (20.93%) is better than the yields previously reported for polysaccharides from several other algae, including

Gelidium crinale (2.6 %),

Sargassum swartzii (11%);

Chaetomorpha linum (16%) [

14,

15,

16]. The yield is though similar to that of polysaccharides isolated from fenugreek [

17].

Polysaccharides are polar macromolecules easy to dissolve in water because they can replace water-water interactions by water-solute interactions. According to Chen et al [

14], polysaccharides extraction yield is influenced by algal species, period of collect and extraction parameters. Moreover, the pH presented a 6.2±03. Ktari et al. [

18] reported that pH of fenugreek polysaccharides solution at 37 ◦C is 6.4. ACPs has relatively low levels of moisture (2.96±0.09%) and ash (3.00±0.08%).

The quantitative estimation of ACPs showed a major contribution of carbohydrates and lesser amount of uronic acid and proteins. Proteins are part of cell walls structure and are associated closely with polysaccharides. It has been considered as potential contaminants of polysaccharides [

19]. After depigmentation and extraction of ACPs, we tried to denature proteins and eliminate the majority of lipids and that’s why we have acquired relatively low levels of proteins (3%) compared to other work done on the other polysaccharides [

8], which suggests the efficiency of the extraction method. In fact, amounts of proteins depend mostly on the method of extraction and deproteination processes. Fleury and Lahaye [

20] indicated that precipitation of proteins during extraction at 100°C contributed probably to their indigestibility. The homogeneity of the polysaccharide was confirmed by elemental microanalyses, which showed a protein content of 3% of protein residues. The ACPs protein contents were similar to those from endodermis of shaddock [

21]. Our results indicate that the procedure used to extracted and isolate ACPs was suitable to yield a compound free of undesired molecules which could interfere in the subsequent experiments.

Moreoever, the results presented in

Table 1 revealed that ACPs had relatively high carbohydrates levels (66.06%).

On the other hand, the uronic acid content of ACPs (11.03%) was similar to those obtained by polysaccharides extracted from

Sargassum vulgare (brown alga) [

22]. It may, therefore, be concluded that the marine origin, the seasonal periods, conditions and extraction method are determining factors for the variations of all these contents.

2.2. Spectroscopic analysis of ACPs

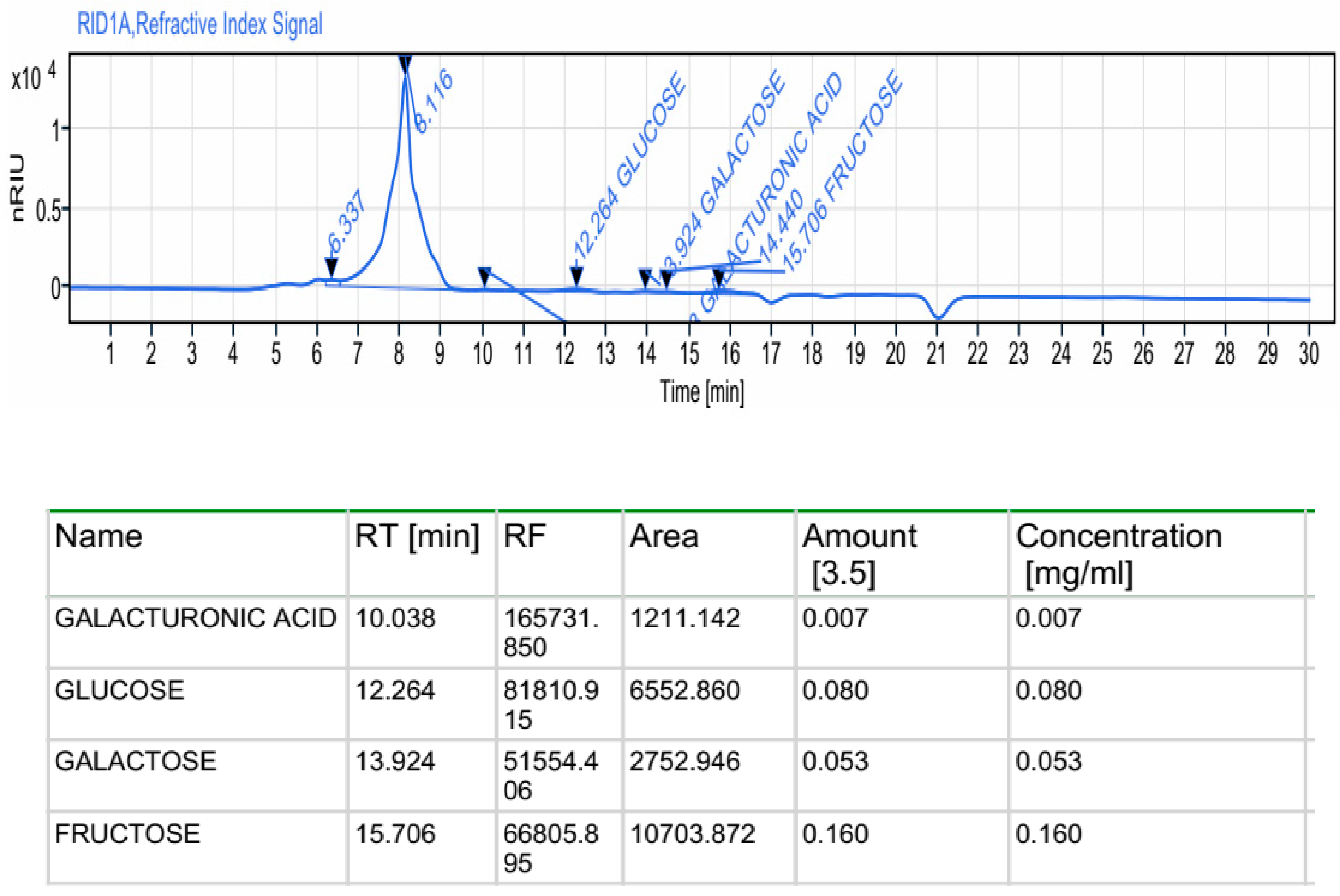

2.2.1. Monosaccharides by HPLC- FID

Various analytical methods and techniques are applied to evaluate the structure of the polysaccharide fragments. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) has been widely used to identify the constituent monosaccharides and molar ratios. HPLC analysis indicated heterogeneous composition, in which galacturonic acid, glucose, galactose and fructose are the major monosaccharide units at retention times of 10.038, 12.264, 13.924 and 15.607 min respectively, according to the elution time a of monosaccharide standards (

Figure 1).

Previous data regarding polysaccharides extracted from macroalgae also revealed heterogeneous compositions of monosaccharides [

23,

24]

. Robic et al. [

25] have reported that the sugar contents can be attributed to the species, the collect period, the sample extraction conditions.

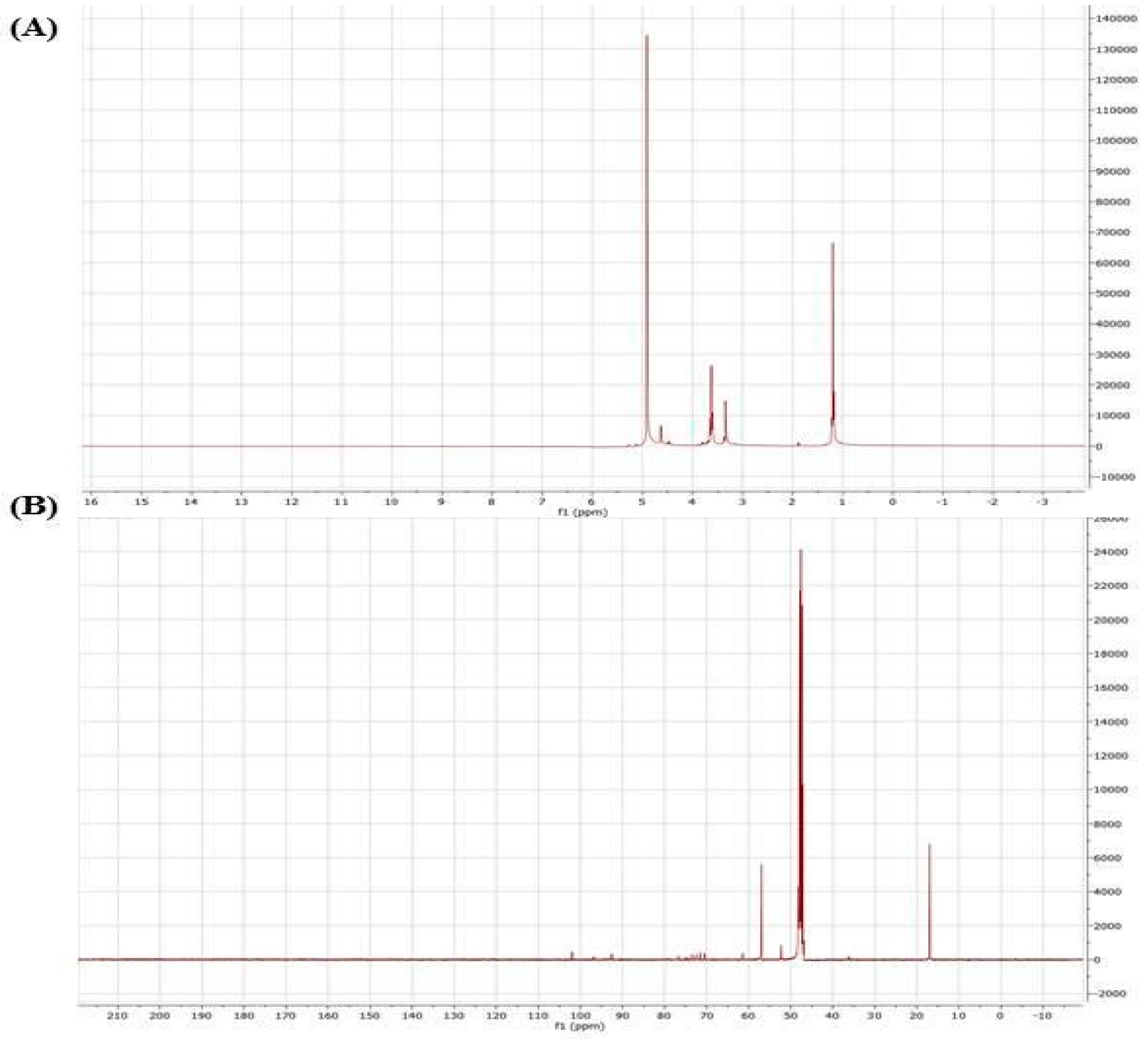

2.2.2. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

A powerful tool for the structural elucidation of polysaccharides is NMR spectroscopy, which can provide structural characteristics like monosaccharide components, anomeric configurations, sulfations linkages and positions of branching [

26]. Nuclear magnetic resonance is the only method that has the potential for full structural characterization of carbohydrates. This technique is seen as a screening test to determine the possible industrial value of raw extracts obtained from unexploited red algae [

27]. Complete structural elucidation requires the full assignment of both the

1H and

13C NMR spectra. To further determine the sequential residue linkage of ACPs, the NMR data of ACPs were performed as shown in

Figure 2 (in liquid and solid state NMR). In

Figure 3A, the anomeric proton signals (δ1; 3.2; 3.5 and 5 ppm) and the anomeric carbon signal (δ 19, 49 and 58 ppm) were matched. The

1H NMR spectrum of the ACPs exhibited a set of wide and intense signals (3.0–4.0 ppm) due to CH2-O and CH-O groups of sugars. It also showed signals between 3.2 and 3.5 ppm associated with anomeric protons. Other signals more intense (5 ppm) related with the intense signal of the solvent and are due to the anomeric protons [

27].

The

13C NMR spectrum of ACPs in a solid state presented broad signals limiting its resolution. It showed, among others, a very intense signal at 50 ppm enveloping certainly several peaks related to osidic CH2-O and CH-O groups. Less intense signal appearing between 15.0 and 18.7 ppm could be assigned to the axial methyl resonates in sugars [

28]. In addition, other monosaccharides such as glucose, galacturonic acid and glucuronic acid also exist in ACPs but in minor amounts which were difficult to detect after methylation.

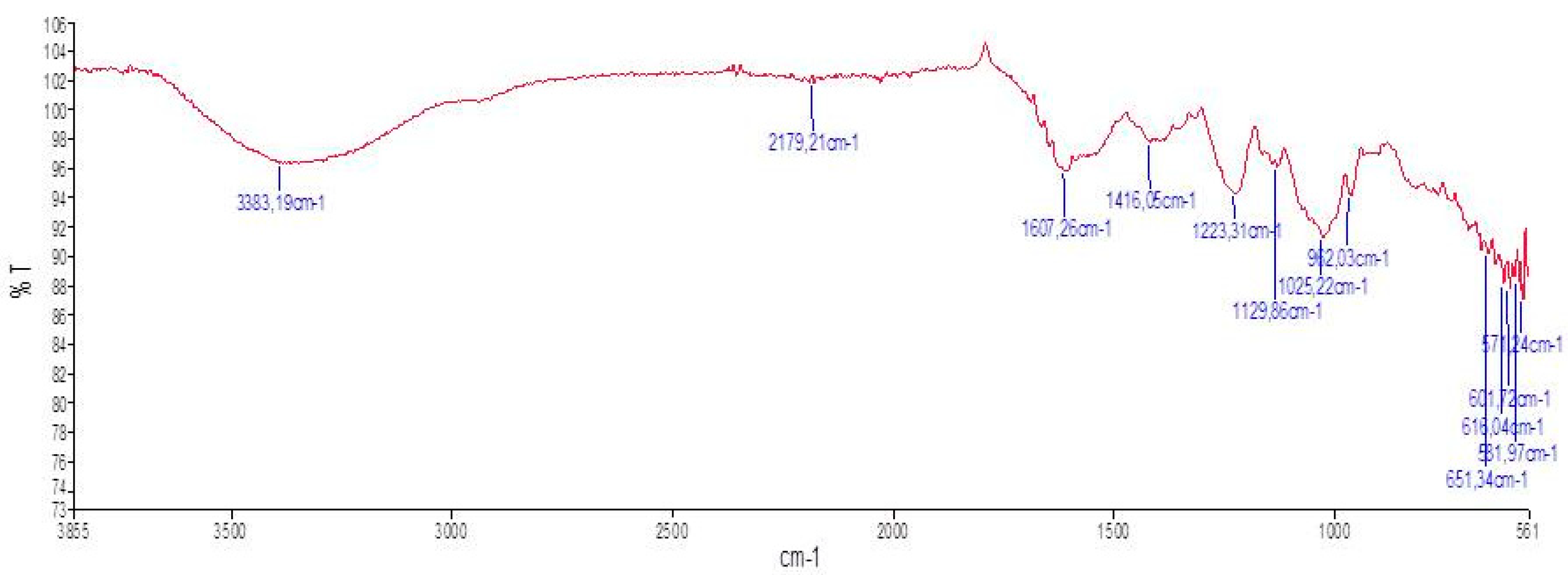

2.2.3. Infra-red spectroscopic analysis

Infra-red spectroscopic analysis is a technique of measurement whereby spectra are collected based on the coherence of a radioactive source, using space domain or time domain measurements of the electromagnetic radiation or other type of radiation. FT-IR spectroscopy is used to investigate the vibrations of molecules and polar bonds between the different atoms. The FT-IR absorption bands were assigned according to previous observations in literatures to identify the chemical nature and useful structural groups [

29]. The spectra obtained from the wave number 500–4000 cm

-1 give some inside information of the tested compounds; therefore, the method is popular in identifying vibrational structure of the materials [

30]. The FT-IR spectrum of ACPs is shown in

Figure 3, in which different absorption bands emerged following wave numbers. The FT-IR spectrum of ACPs displayed typical signals of polysaccharides. ACPs showed bands at 3383.19; 2179.21; 1607.26; 1426.06; 1223.31; 1129.88; 1025.22 and 962.03 cm

-1. The broad band at 3383.19 cm

−1 was due to the stretching vibration of O-H and N-H. Bands in the region of 2179 cm

−1 represented the C-H stretching and bending vibration. The absorption peak at 1607 cm

−1 was ascribed to C-O stretching vibration which was the characterization of uronic acid. The band at 1223 cm

−1 was assigned to O=S=O stretching vibration of sulfate esters [

31]. The adjacent peaks at 1129 cm

−1, and 1025 cm

−1 indicated the C-O-C and C-O-H stretching vibration, which demonstrated the presence of pyranose ring [

32]. The peak at 962 cm

−1 was from the C-O-C vibration, suggesting that the presence of sulfate group was mainly at C-3 position [

33]. Based on the FT-IR spectrum it could be anticipated that the ACPs of may be predominantly acidic in nature (

Figure 3).

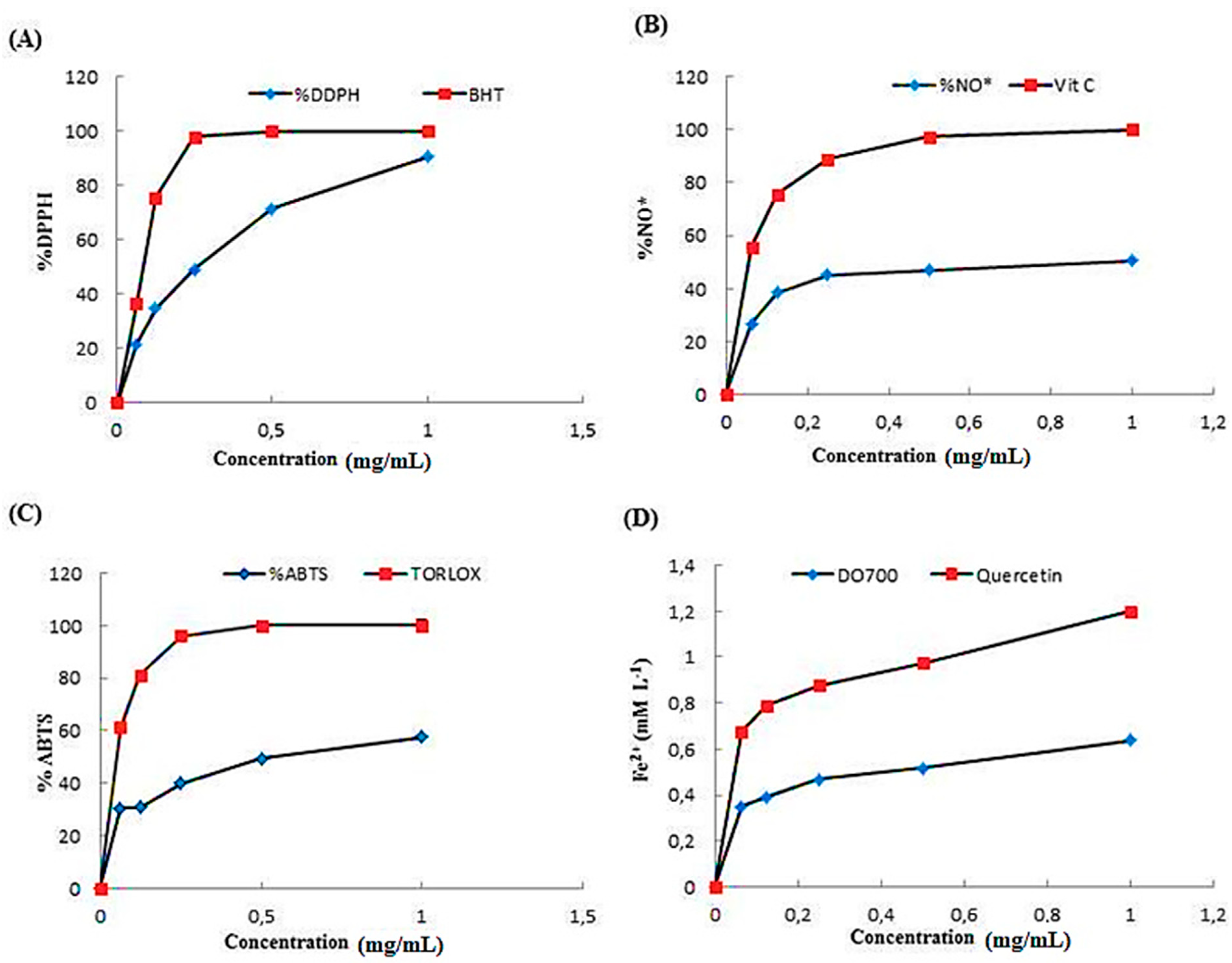

2.3. In vitro biological activities of ACPs

Antioxidant activities of ACPs have been determined by various methods such as DPPH radical scavenging, ABTS radical scavenging, ferric reducing antioxidant power and nitric oxide scavenging assays.

2.3.1. Effect of ACPs on DPPH scavenging activity

DPPH is an accurate, convenient and quick method analyzes the free radical scavenging ability of natural compounds in contrast to some other methods [

33].

The antioxidant competence of a compound can be obtained by DPPH assays. DPPH is a synthetic free radical which can be effectively, scavenged by antioxidants [

33]. It has been used for rapid evaluation of the antioxidant ability of plant extracts. The DPPH scavenging activities of ACPs were presented in

Figure 4A. Results clearly indicated that ACPs exhibited high antioxidant activity against DPPH under a concentration dependent approach. A maximum DPPH scavenging activity of ACPs at a concentration of 1 mg/ml with a percentage inhibition of 80% was observed whereas, BHT showed a maximum percentage inhibition of 100% at 0.25 mg/ml. Our results are in similar to previous work by Khaskheli et al. [

34], who reported the positive correlation between the DPPH scavenging activity and sample concentrations. The effects of ACPs on DPPH radical scavenging is thought to be due to their hydrogen donating ability and to the presence of sulfate group [

35]. Furthermore, it has been reported that antioxidant activities of polysaccharides were in relation with their sulfation degree, uronic acid content, molecular weight and glycosidic linkage [

36].

2.3.2. Scavenging effect of ACPs on nitric oxide radical

ACPs showed maximum nitric oxide scavenging activity at 1 mg/ml with an inhibition of 40%. Vitamin C showed a maximum nitric oxide scavenging (100%) at 0.5 mg/ml (

Figure 4B). Nitric Oxide (NO) is a diffusible free radical, which plays impotant role as an effector molecule in diverse biological systems such as antioxidant, antitumor and antimicrobial activities [

37]. According to Kim et al. [

22], the polysaccharides obtained from

Sargassum fulvellum, are more potent NO scavenger than synthetic antioxidants including α–tocophorol and BHA.

2.3.3. ABTS radical scavenging activity of ACPs

ABTS radical scavenging activity is an exceptional method for testing the antioxidant activity of hydrogen-donating and chain-breaking antioxidants [

38]. The total antioxidant ability of ACPs was measured by means of scavenging a protonated radical ABTS and compared with Trolox standard. The present study results showed that ACPs reacted on ABTS radicals at different concentrations ranging from 0 to 1 mg/ml, respectively (

Figure 4C).

ABTS radical was scavenged at maximum concentration of 1 mg/ml with percentage inhibition of 58% by ACPs whereas Trolox showed 100% at 0.25 mg/ml. The scavenging ability of ACPs on ABTS free radicals demonstrated that the activities of every sample increased as the concentration increased. A positive correlation has demonstrated between sulfate content and ABTS activity in polysaccharides fractions extracted from a brown seaweed

Laminaria japonica [

39].

2.3.4. Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

The FRAP assay could estimate the capacity of antioxidants to reduce Fe

3+-Fe

2+ by providing an electron. It has been signaled the direct correlation between reducing powers and antioxidant activities of bioactive compounds. In the present study, the capacity of ACPs to reduce Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ was determined. As indicated in

Figure 4D, the reducing activity of ACPs and quercetin increased with increasing concentration. At the concentration of 1 mg mL

-1, the FRAP value of ACPs was 0.6 mM L

-1, which was weaker than that of quercetin (1.2 mM L

-1). According to previous study, the polysaccharides of

Fucusve siculosus have demonstrated its antioxidant capacity using the FRAP assay [

35].

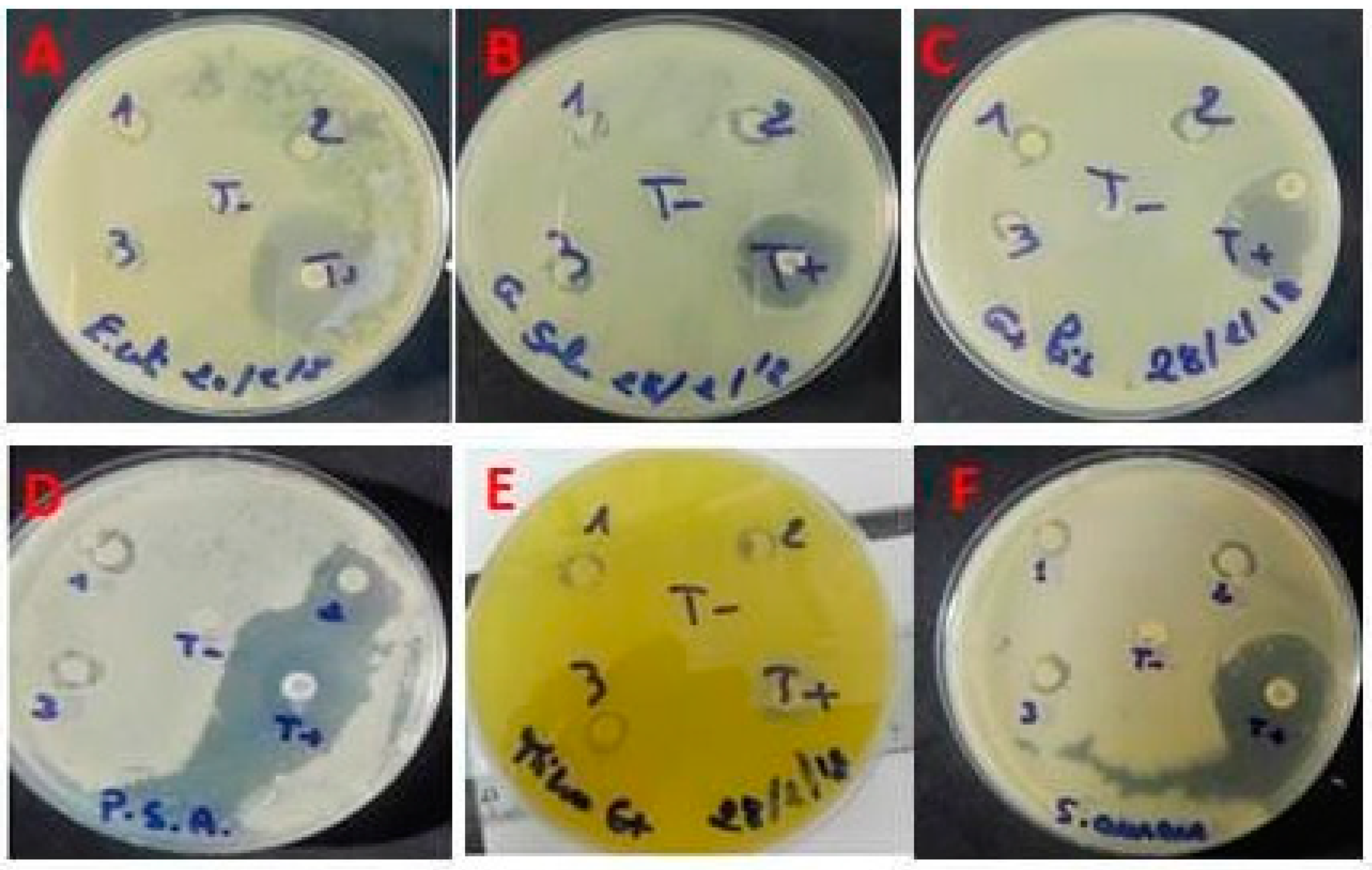

2.3.5. Antimicrobial activity of ACPs

Antimicrobial resistance may be acquired by genetic mutation in bacteria making them resistant to the effect of one or more antimicrobial agents. The rising of antibiotic resistance remain a significant concern for pathogenic bacteria infections [

40]. There have been reports on the antimicrobial ability of seaweeds [

41]. Here, the new polysaccharides from

Alsidium corallinum was evaluated for its antimicrobial potential against six Gram (+) and Gram (-) by the disc diffusion method. The results reveal that the polysaccharides studied exert a considerable antibacterial effect on all the strains used with inhibition zones of 8 mm and 10 mm respectively, compared to the standard antimicrobial agent, ampicillin. Depending on the extent of the inhibition zone (

Figure 5), we can classify ACPs in one of the following categories: Sensitive, Intermediate, or Resistant. CMB corresponds to the lowest concentration of the extract capable of killing 99.9% of bacteria contained in the starting inoculum. The results show that the values of CMI and CMB agree with those of the inhibition diameters. ACPs induced an important zone of inhibition exhibiting the lowest values of MIC on the corresponding strains (

E. coli,

S.enterica,

P. aeruginosa,

M.lutus,

L.invanovii, and

S. aureus).

Consequently, we compared the MIC and CMB of ACPs on the strains tested, the ACPs fractions show a bactericidal effect since the MIC/CMB ratios for all the target test strains of Gram

- and Gram

+ is equal to 1 and / or 2 (

Table 2). Our results support previous funding that Gram (+) bacteria are more sensitive to marine polysaccharides extracts than Gram (-) bacteria [

42].

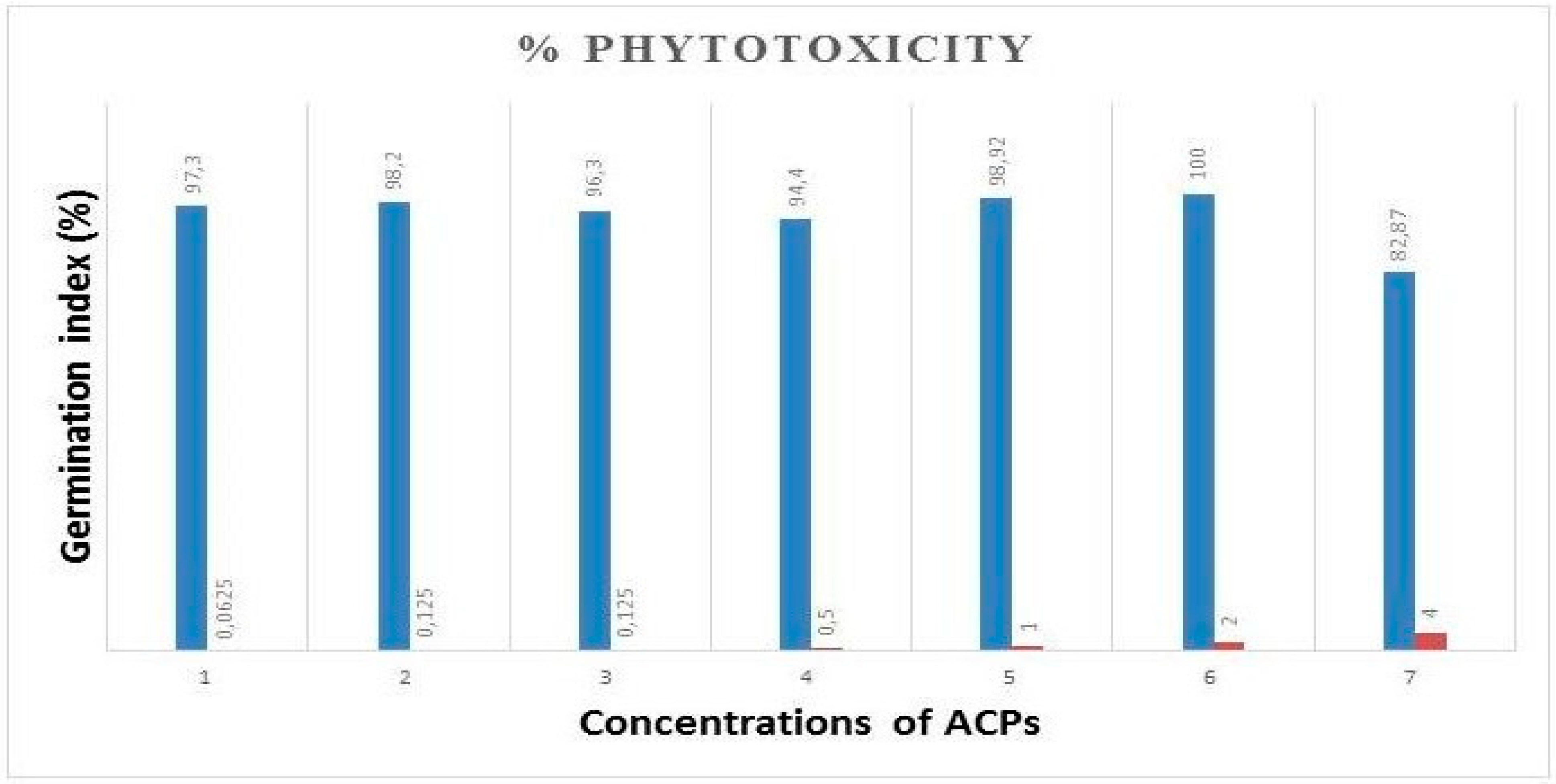

2.4. Phytotoxicity essay of ACPs

As shown in

Figure 6, ACPs phytotoxicity was determined in different concentrations (1; 0.5; 0.25; 0.125; 0.0625 mg/ml) against cress seeds. Our results have shown that seeds germination percent ≥ 80% with the different concentrations of ACPs which confirms that polysaccharides from

Alsidium corallinum are not phytotoxic [

43].

2.5. In vivo biological activities of ACPs

2.5.1. Effect of ACPs on toxicity markers in hepatic tissue

Liver is an extremely important organ responsible for drugs and toxic chemical metabolisms. It is frequently damaged by nearly all toxic chemicals and its damage is considered one of the global health problems [

44]. Lipid peroxidation represents one of the frequent reactions resulting from free radicals ‘attack on biological structures. Extensive lipid peroxidation in cellular membranes caused disturbances of structural integrity, a decrease of membrane potential, an increase of permeability to ions, and a loss of fluidity [

45].

Table 3 represents the level of MDA in the liver tissue homogenate of rats treated by TBZ and ACPs. The TBZ-treated rats exhibited significant increase of hepatic MDA concentration as compared to control group (

Table 3). An elevation of lipid peroxidation, in animals treated with pesticide has been previously reported [

46]. Lipid peroxidation can damage the hepatocytes membrane by accumulation of ROS. Cellular capacity to produce ROS has been generally evaluated by determining H2O2 levels release by mitochondrial respiration. TBZ generated hepatic oxygen radical production through the increase of H2O2 radical levels. Moreover, the increase of free radicals generation can also lead to protein modifications [

47]. Locckie et al have reported that AOPPs can reflect an excess of free radical generation, confirming the protein oxidation.

In our study, ROS, probably generated by TBZ treatment, induced a rise of AOPPs in the liver of adult rats. An abnormal rise in lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation was reduced with ACPs administration, due to their antioxidant ability, emphasized through in vitro experiments [

48]. Thus, the natural polysaccharides can act as a defensive mechanism for antioxidant status in liver tissue and can prevent the uncontrolled formation of ROS and/or directly scavenging the free radicals.

2.5.2. Effect of ACPs on antioxidant statute in liver tissue

In vivo antioxidant capacities of ACPs were further confirmed by determining the antioxidant statute in TBZ-induced toxicity. Among the antioxidant enzymes, GSH-Px and SOD, are the first line defenses against oxidative stress injury and ROS generation [

75]. Antioxidant enzyme activities in experimental animals are given in

Table 3. TBZ treatment significantly reduced (p<0.05) the antioxidant defense of the adult rats compared to controls. It is probable that the reduction in the antioxidant enzyme activities is the principal factor in lipid peroxidation damages [

49]. A decrease of SOD and GSH-Px is due to the generation of ROS, leading to deleterious effects such as loss of integrity and function of cell membranes [

46]. Consistent with the earlier study, decreased hepatic SOD and GSH-Px activities was shown in the TBZ-administered rats [

50]. While TBZ +ACPs and ACPs groups showed a significant increase (p <0.05) in antioxidant activities when compared to TBZ group. Therefore, increase of GSH-Px and SOD activities might be devoted to the antioxidant ability of ACPs

in vitro. Zhang et al. [

51] have shown an increase in antioxidant defense in ageing mice on supplementation with polysaccharides fraction from

Porphyra haitanesis. In addition,

Astragalus polysaccharides exhibited hepatoprotective effect due to their capacity to scavenging free radicals, to reduce oxidative stress and inhibit lipid peroxidation [

52]. Earlier reports have shown that the mechanism involved in the antioxidant activity is the ability of a molecule to donate a hydrogen atom to a radical, with the propensity of hydrogen donation being a critical factor. Thus, hydrogen atom donors have the ability to terminate chain reactions by converting free radicals to more stable products. It has been hypothesized that the antioxidant capacity of polysaccharides is related to its molecular weight and chemical composition [

53].

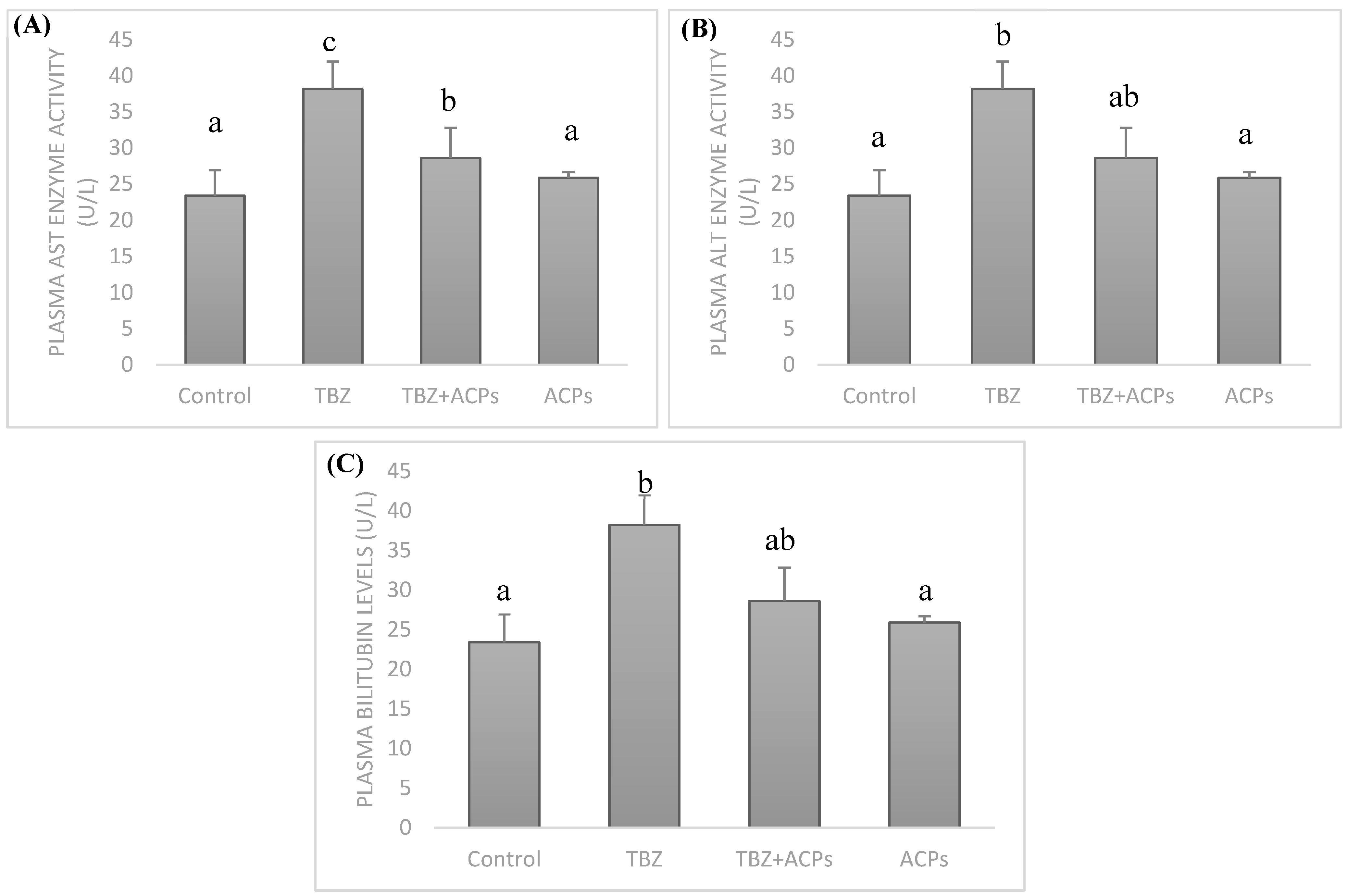

2.5.3. Effect of ACPs on hepatotoxicity

The toxicological studies of TBZ have been conducted by measuring plasma AST and ALT enzyme activities and bilirubin levels. The increased levels of these enzymes are indicators of liver damages. These are the most frequently indicators of necrosis of hepatic cells. AST are presented in both cytosol and mitochondria of a wide variety of tissues like skeletal muscle, heart, brain, liver and kidney. ALT is localized in the cytosol of hepatocytes. While, Bilirubin is present in bile and formed as a by-product during the breakdown of old red blood cells in liver [

54]. Common biochemical markers of liver damages are the increase of ALT, AST and bilirubin activities in the blood [

55]. TBZ resulted in increased of plasma AST and ALT activities and bilirubin levels (

Figure 7). Interestingly, the rats supplemented with ACPs reduced the abnormal changes significantly, and recovered the activities of these enzymes to a normal levels, displaying a meaningful result that the supplementation of ACPs has a protective effect against hepatotoxicity produced by TBZ and could ameliorate the liver injury in TBZ-treated rats, showing its potential to maintain the normal functional status of the liver, as reported by Lekshmi and co-workers in 2019 [

56] using the edible marine alga

Padina tetrastromatica. Results are expressed as mean of three experiments ± SD. The number of determinations was n = 3. a,b,c In the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

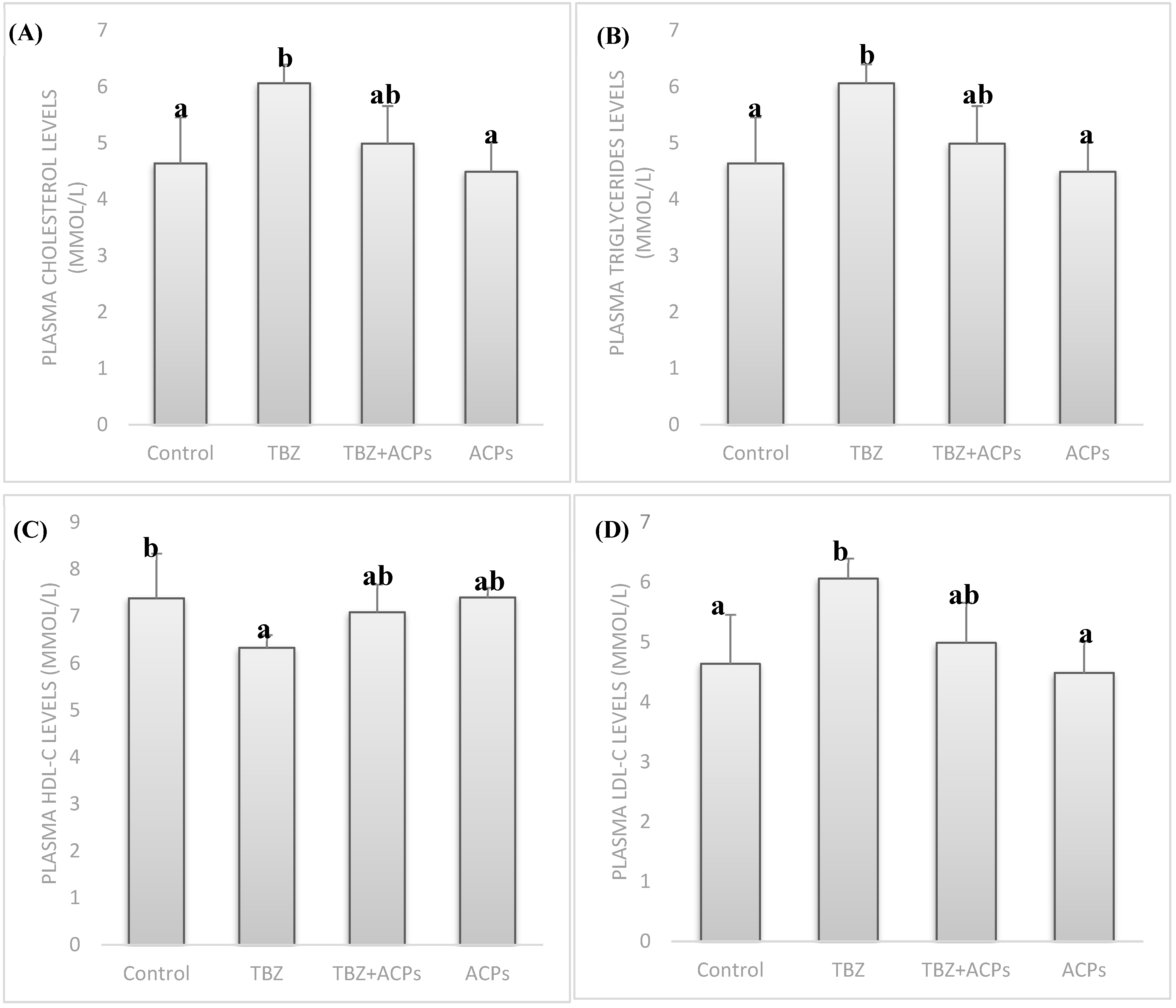

2.5.4. Effect of ACPs on plasma lipid levels

In the present study, the indicators of lipid metabolism were examined. After treatment for 4 weeks, the levels of TC, TG and LDL-C in plasma of TBZ-treated group were significantly higher than that of control group. The HDL-C value in TBZ model group significantly lowered. There was a positive correlation between plasma triacylglycerol and total cholesterol levels and free radicals generation [

54]. One of the harms of TBZ is the accumulation of liver fat due to the metabolism disorders of blood lipid, which resulted in the weakening of the detoxification ability of the liver. However, all TC, TG and LDL-C levels were significantly decreased by ACPs supplementation (

Figure 8), while the HDL-C value increased significantly. All the levels recovered to a similar levels of control group, indicating ACPs can be a promising alternative remedies for reducing plasma lipid levels. The results may be associated with it potential protection effect to hepatic cells by gearing up the detoxification machinery. It is believed that polysaccharides have shown anti-lipid effect in experimental research [

57]. However, some chemical groups may play a key role in the polysaccharides activities. Sulfate is one of these, which has been closely associated to antioxidant activity [

58]. Taken together, the results of the present study indicate that ACPs ameliorates TBZ induced hyperlipidemia. With previous studies result polysaccharides may be beneficial against hyperlipidemia and maybe a suitable alternative hypolipidemic source for humans. These polymers were shown to have significant preventive effects on the elevation of cholesterol and triglycerides in plasma and liver tissue.

Results are expressed as mean of three experiments ± SD. The number of determinations was n = 3. a,b,c In the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

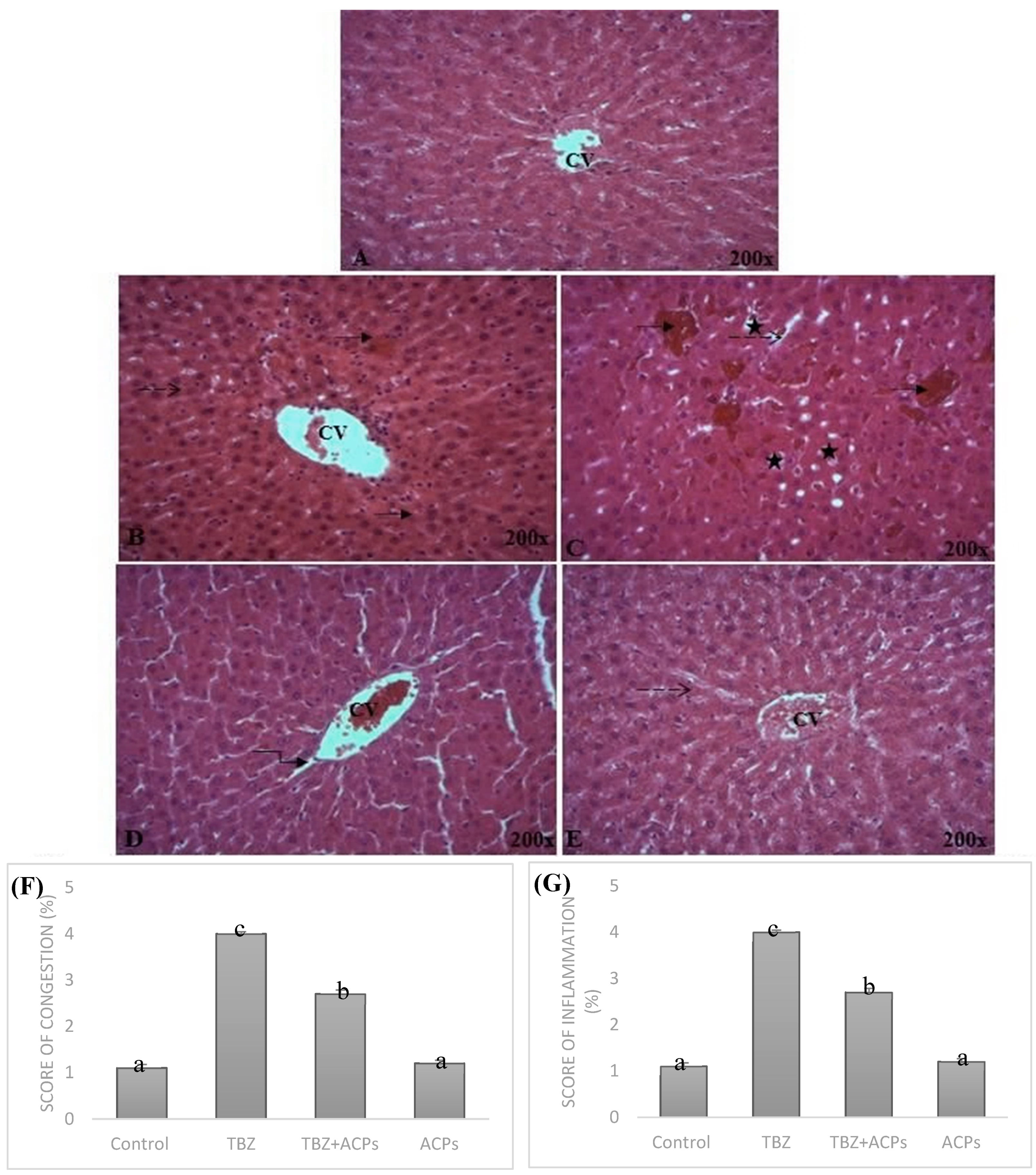

2.5.5. Histopathological analysis of liver tissue

Representative views of liver sections are presents in

Figure 9. As shown in tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, the liver tissues of normal rats exhibited the normal cellular structure with neatly liver lobule, cords and clear structure of portal area (

Figure 9A). Compared with sections from livers in the control group, TBZ presented morphological tissue degeneration including, intense cellular degeneration, sinusoidal dilatation and severe inflammatory infiltration of hepatocytes with vascular congestion (

Figure 9B). In addition, administration of TBZ caused focal area of hepatic necrosis completely replaced by leucocytic cells infiltration and focal hepatic hemorrhage (

Figure 9C). Compared to TBZ-treated rats, oral administration of ACPs improved the hepatic architecture; as compared to TBZ group and it apparently showing the regeneration of liver parenchyma (

Figure 9D, E). ACPs rats showed clearly less ballooning degenerative, less loose, less necrotic and less inflammatory cell infiltration (

Figure 9E). The histological results were consistent with biochemical data, which further confirmed the hepatoprotective effect of ACPs.

Different superscript letters (a,b,c) in the same row indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

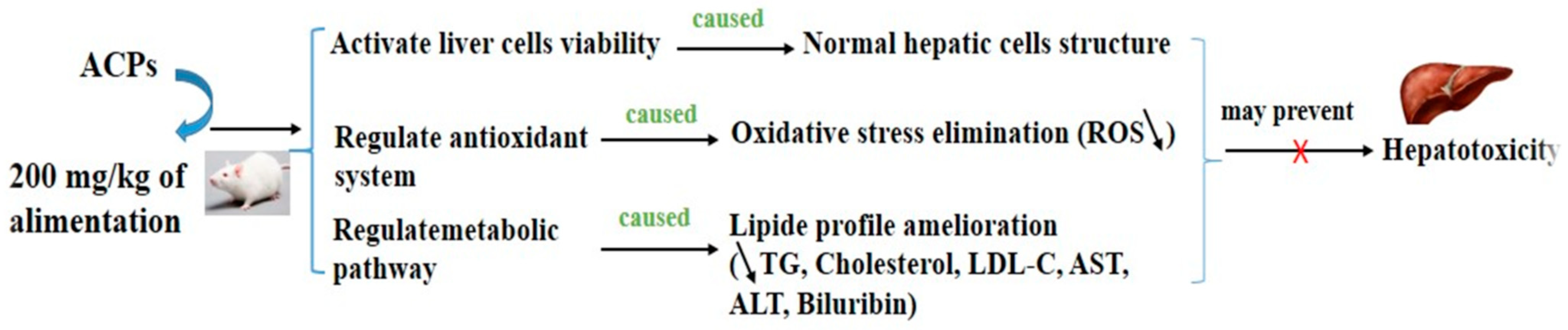

We summarized the current findings regarding the polysaccharides derived from the red macroalga

Alsidium corallinum with hepatoprotective activity and describe the underlying mechanisms (

Figure 10). In general, the possible mechanisms of action by which polysaccharides exert their hepatoprotective activity are mainly divided into the following three directions. (1) ACPs activate the viability of hepatocyte cells by directly activating the protein responsible in cell differentiation. (2) ACPs can ameliorate the hepatic and serum index through oxidative stress response pathways by activation of antioxidant system. (3) ACPs can balance the lipid profile by amelioration of reverse transport of cholesterol and improvement of the anti-atherogenic metabolic pathway.

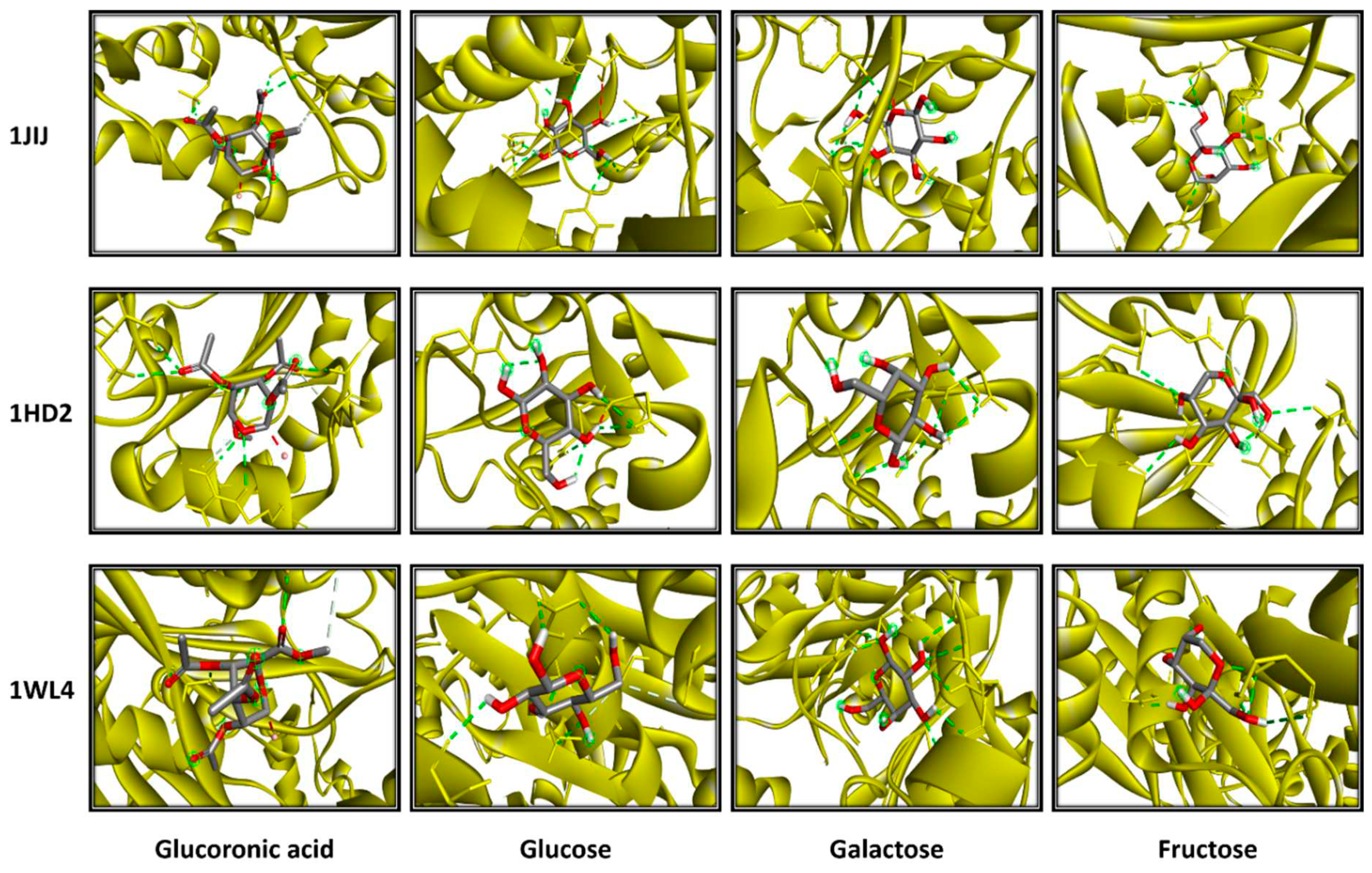

The computational study exhibited that

A. corallinum monosaccharides had various affinities to each of the targeted receptors (

Table 4). Previous studies reported that variation in affinities is due to the chemical composition and geometry of the studied ligands [

59,

60]. Interestingly, all

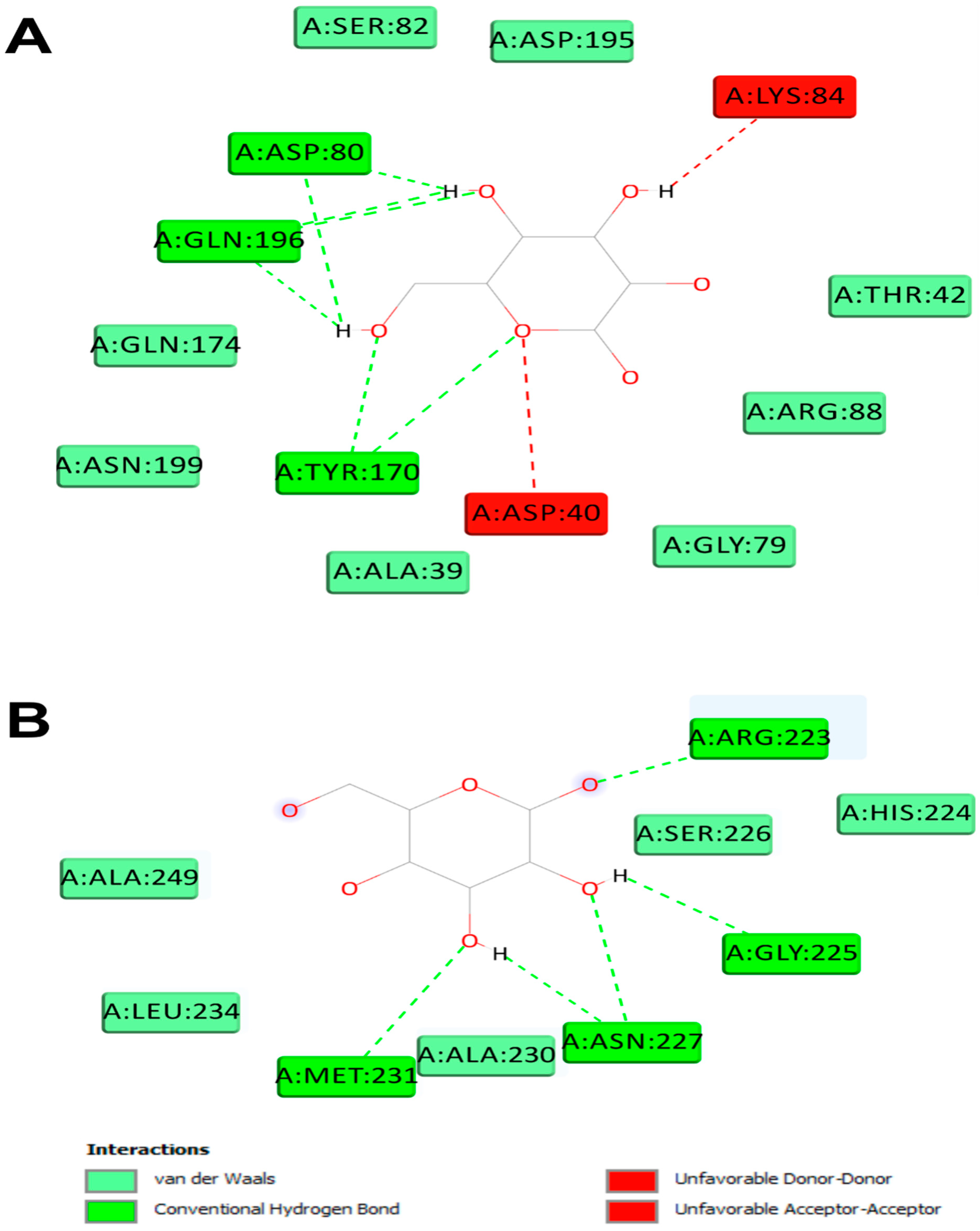

A. corallium monosaccjharides possessed negative binding scores, which might contribute to their biological activities. These binding affinities varied between −5.8 and −7.1 kcal/mol for 1JIJ, between −5.1 and −5.4 kcal/mol for 1HD2, and between −4.9 and −5.2 kcal/mol for 1WL4. The best binding scores was predicted to galactose then to glucose while complexed to the TyrRS from S. aureus receptor, which may contribute to their highest biological activities, specifically the antimicrobial effect (

Table 4,

Figure 11). Galactose established good molecular interactions with the targeted receptors that showed 5 or 7 conventioal H-bonds supported with a network of carbon H-bonds, hydrophobic and/or electrostatic bonds, which significantly contribute to the stability of the complexes [

59,

62]. These molecular interactions included several key residues. In fact, it involved Gln196 (tree times), Tyr170 (twice), and once to each of Asp80, Asp80, for 1JIJ, and Asp77 (three times), Arg124 (twice) and Asn76,for 2XCT, and Asn227 (three times), Arg223 (twice), and once to each of Met231 and Gly225 for 1WL4 (

Figure 11;

Figure 12).

The studied monosaccharides were also deeply embedded in the pocket region of 1JIJ, 1HD2 and 1WL4 receptors at distance that reach 1.771 Å only between glucoronic acid and Ser87:HG of the Acyl-CoA:cholestrol acyltransferase. Overall, the calculated binding energies, the molecular interactions and the deep embedding of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides confirm that the potential antibacterial, antioxidant and hypolipidemic effects are thermodynamically possible. These effects have already been approaved by the in vitro approaches and the in vivo results on TBZ-intoxicated rats. Our results also confirm the promising antimicrobial and antioxidant effects of the medicinal plants and the natural-derived compounds including algae [59,62, 63,64]. These effects may also include the acceptable bioavailability and the pharmacokinetic properties of the algal monosaccharides, which had been previously reported.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Source of alga-derived polysaccharides

The marine red algae Alsidium corallinum was collected from the coast of Sfax, Tunisia. The voucher specimen of this specie was deposited and identified in the herbarium of the Biology Laboratory, at Faculty of Sciences of Sfax. Alga was rinsed with tap water followed by deionized water. Next, it was dried and ground before starting the extraction.

3.2. Extraction of sulfated polysaccharides (ACPs)

ACPs were extracted according to Liu and Chen’s method [

65] . Briefly,

A. corallinum powder was pre-extracted with ethanol (90%) to remove pigments. The dry residue was extracted twice with deionized water at 70◦C along with stirring over 6 h. Extract was combined and filtered and filtrate was subsequently evaporated under vacuum. The concentrated liquid was precipitated with ethanol during 24 h at 4 ◦C and then centrifuged during 15 min. The obtained precipitate was re-dissolved in double distilled water. The water phase was dialyzed at 4 ◦C against distilled water for 48 h. The dialysate was concentrated through rotary evaporation to obtain ACPs. The latter were stored at-20 ◦C for additional use.

3.3. Extraction yield and physicochemical analysis of ACPs

Yield of ACPs was expressed as percentage (%) of the mass (g) of polysaccharides against the mass (g) of A. corallinum powder.

pH of ACPs (1% solution at 25 ◦C) was measured using a pH meter with complete immerging of the glass electrode into the solution.

The moisture and ash contents were determined at 105 and 550 ◦C, according to the AOAC standard methods 930.15 and 942.05, respectively [

66].

Content of proteins was estimated by the method of Bradford [

67]. Absorbance was measured by spectrophotometer (595 nm). Protein levels were determined from a standard curve plotted using bovine serum albumin as reference protein. All tests were carried in triplicate.

Uronic acid amounts were determined by Blumenkrantz and Asbœ-Hansen’s method [

68]. The Absorbance was determined with a spectrophotometer (520 nm). Uronic acid amount was determined using a standard curve of glucuronic acid.

Carbohydrate amounts were determined by the method of Masuko [

69]. Carbohydrates contents were measured by spectrophotometer at 490 nm. The result was estimated from a standard curve using glucose as reference sugar.

3.4. Spectroscopic analysis

3.4.1. Monosaccharide analysis by HPLC-FID

The HPLC-FID assay was performed as described by Bayar et al. [

70]. Monosaccharide composition was analyzed using a Sugar KS-800 column with a mobile phase of 0.001 M NaOH, flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and column temperature of 60 ◦C. Fructose, arabinose, Glucose, gluconic acid, sucrose, mannose, xylose and galactose were used as standard.

3.4.2. Fourier Transmission-Infra Red (FT-IR) spectral analysis

FT-IR spectrum of ACPs was determined on a Nicolet FT-IR spectrometer equipped with horizontal attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory. The internal crystal reflection was made from zincselenide and had a 45◦ angle of incidence to the IR beam. The measurement was between 4000 and 500 cm−1. The transmission spectra of the samples were recorded by using the KBr pellets.

3.4.3. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

NMR spectrum of ACPs was obtained using an Avance DPX-500 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) at 500 MHz and 50°C with acetone as the internal standard. The sample concentration was 10 mg of polysaccharides/mL of D2O for 1H and 13C.

3.5. In vitro biological activities of ACPs

3.5.1. DPPH radical-scavenging assay

The DPPH of ACPs was performed according to the method described by Bersuder et al [

71]. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm, using a UV visible spectrophotometer. DPPH activity (I %) was calculated according to the equation:

Where: Abs control is the absorbance of the control reaction;

Abs sample is the absorbance of ACPs with the DPPH solution.

3.5.2. ABTS radical scavenging assay

The ABTS was assayed according to Miller et al method [

72]. This method is applicable to hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants. Concentration of ABTS was measured by spectrophotometer at 690 nm. The percentage inhibition of ACPs was calculated and compared with Trolox (6 hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) used as standard.

3.5.3. Ferric reducing activity power (FRAP)

The ability of the ACPs to reduce iron (III) was determined using the method of Fawole et al. [

73] with some modification. The resulting solution was measured at 700 nm. The reducing power was in related to the absorbance of the reaction mixture. Vitamin C was used as positive standard.

The reducing power was calculated according to the equation:

3.5.4. Nitric oxide radical scavenging activity

Nitric oxide radical scavenging activity of ACPs was determined using the method described by of Marcocci et al [

74]. The resulting solution was measured at 700 nm. Result was calculated by the following formula:

3.5.5. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial activity

3.5.5.1. Microbial strains and growth conditions

ACPs were assessed against a panel of microorganisms including six bacterial strain: Gram- negative: Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Gram-positive: Micrococcus luteus, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Staphylococcus aureus. All the strains tested were obtained from the Microbiology laboratory, Faculty of Science of Sfax, Tunisia.

3.5.5.2. Disk diffusion method

For the purpose of the antimicrobial activity, the disk diffusion method was employed according to Nilsson et al. [

75]. Antibacterial activity was estimated by measuring the diameters of the inhibition zones against the test organisms and compared to ampicillin and cycloheximid (10 µg per disk) as the positive control against bacteria and yeast, and against fungi, respectively. The accurate inhibition zone of any dimension surrounding the paper disk was measured by sliding caliper. This test was conducted in triplicate.

3.5.5.3. Microdilution method

A broth microdilution method was used to resolve the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) [

76]. The ampicillin was used as positive control against bacteria. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of the extract at which the microorganism does not reveal evident growth. The microorganism growth was estimated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Whereas, the MBC expresses the lowest level of antimicrobial agent of the tested extract that results in microbial death. Each test was performed in three replicates.

3.6. ACPs phytotoxicity analysis

The phytotoxicity of the polysaccharides obtained from

A. corallinum was evaluated by methods of Zucconi and Monaco [

77] using the seed germination technique. Throughout the assay, control included only distilled water sterile. The length of seedling growths was measured as mm. The phytotoxicity of our polysaccharides was evaluated by percentage of germination index (GI %).

3.7. In vivo antioxidant activities of ACPs

3.7.1. Animal diet and tissue preparation

Aged rats (180±20g, n=40) were divided in four groups; received either no treatment (control group), 100 mg/kg body weight of TBZ by intraperitoneal injection (TBZ group), TBZ and 200 mg/kg of alimentation ACPs, or 200 mg/kg of diet ACPs. After 30 days of treatment, all animals were sacrificed. Liver tissue was divided into two parts: One part for the determination of oxidative stress markers, and the other part for the histological study. Blood was collected into heparinized tubes and centrifuged at 2200 xg for 10 min. The plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until biochemical analysis. The experimental procedures of animals were performed according to the Natural Health Institute of Health Guidelines for Animal Care approved by the Institute Ethical Committee Guidelines Council of European Communities [

78] and the use of laboratory animals of our institution.2.7.2. Liver protein quantification

According to Lowry et al. [

79] , liver protein contents were measured with bovine serum albumin as standard.

3.7.3. Determination of oxidative stress markers

The amount of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the liver tissue was determined according to the Draper and Hadley method [

80]. The result was expressed as µmol malondialdehyde /mg protein.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) test was performed using the ferrous ion oxidation xylenol orange method [

81]. H2O2 contents in the liver was measured at 560 nm in a spectrophotometer and expressed as μmol/mg protein.

Advanced oxidation protein products (AOPPs) concentrations were analyzed using the methodused by Witko et al [

82]. The level of AOPPs in liver tissue was calculated using an extinction coefficient of 261 mM

-1 cm

-1 and expressed as nmol/mg protein.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme activity was assayed using the method of Beauchamp and Fridovich [

83]. Result was expressed as units/mg protein.

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) enzyme activity was assayed according to the method described by Flohe and Gunzler [

84]. The results were expressed as nmol glutathione oxidized/min/mg protein.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels were estimated by Ellman [

85] and modified by Jollow et al. [

86]. The absorbance was recorded at 412 nm after 10 min. Total GSH content was expressed as nmol/mg of protein.

3.7.4. Biochemical index measurements

Plasma aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities, and bilirubin levels, which are considered to be the biochemical markers of hepatic damage, were assayed according to the standard procedures using the commercially kits purchased from Biomaghreb (Ariana, Tunisia, Ref: 20043; 20047 and 20102).

3.7.5. Lipid profile in plasma

Total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides levels were determined using kits obtained from Biomaghreb (Tunisia, Ref: 20111, 20113 and 20131 respectively). The low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) fraction was determined using the Friedewald equations:

[LDL-cholesterol] = Total cholesterol - [(Triglyceride/5) + HDL-cholesterol].

3.7.6. Histological examination

The liver collected from each group was randomly selected for light microscopy. Samples were fixed in formalin solution and embedded in paraffin. It was then sectioned and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. All sections of liver tissue were evaluated for the degree of injury.

3.8. Computational Analysis and Interactions Assay

The four monosaccharides in

Alsidium corallinum, which had been identified were used in the computational stud to decipher their molecular interactions and confirm their potential antioxidant, antimicrobial and hypolipidemic effects. The chemical structure of these monosaccharides were collected from pubchem website. The 3D crystal structure of TyrRS from

Staphelococcus aureus (1JIJ), human peroxiredoxin (1HD2), and Acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT, 1WL4) were obtained from the RCSB PDB. The studied monosaccharides and three targeted receptors were prepared, processed for minimization then saved in pdbqt format [

59,

60]. They have been subjected to a CHARMm force field as previously reported after targeting the grid box by selecting some key residues within the pocket region [59-62]. The reasons behind the selection of these receptors are the huge responsibility of hospital-acquired infections by

S. aureus, the key role to reduce hydrogen peroxide and alkyl hydroperoxides using equivalents, and the key involvement in fatty acid metabolism.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiences and statistical analyses were made in triplicate. All results are expressed as the mean±standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 17.0 statistical package for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). A two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was performed to compare treatment and control groups. Statistical significance was set at p=0.05.

4. Conclusion

The polysaccharides from Alsiduim corallinum contained a relatively high percentage of uronic acid, carbohydrates, sulfate and sugar group contents, which were thought to correlate with higher antioxidant and antimicrobial abilities. It exhibited protective effects against TBZ-induced toxicity by reducing ROS production. All these findings indicated that ACPs could be a potential natural resource in the development of dietary supplements to inhibit pesticides-induced toxicity. Both finding scores and molecular interactions of A. corallinum polysaccharides may explain the experimental in vitro findings on some selected bacteria and in vivo results on TBZ-intoxicated rats, which may result on the antioxidant, antimicrobial and hypolipidemic activities. Further studies are required to clarify the mechanism of action of red-algae polysaccharides on liver cells, to determine the composition and bioavailability of red-algae polysaccharides present in different algal sources and to probe the clinical availability of these compounds in the form of algal foods, food supplements, and regulated therapeutics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S. White kristian thygesen, joseph S, Alpert and harvey D. White on behalf of the joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF task force for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart. J. 2007, 28, 2525–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, E.G.; Escrig, A.J.; Ruperez, P. Dietary fibre and physicochemical properties of several edible seaweeds from northwestern Spanish coast. Food. Res. Int. 2010, 43, 2289–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Lee, O.H.; Lee, B.Y. Fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide, inhibits adipogenesis through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Life. Sci. 2010, 86, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhamandas, J.H.; Wie, M.B.; Harris, K.; MacTavish, D.; Kar, S. Marine Nutraceuticals: Prospects and Perspectives. Eur. J. Neur. 2005, 21, 2649–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehila, T.S.; Margalit, B.; Dorit, M.; Shlomo, G.; Shoshana, A. Antioxidant activity of the polysaccharide of the red microalga Porphyridium sp. J. App. Phycol. 2005, 17, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, S.M. Structure and antitumour activity of fucoidan isolated from sporophyll of Korean brown seaweed Undaria pinnatifida. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Kim, K.N.; Lee, S.H. Anti-inflammatory activity of polysaccharide purified from AMG-assistant extract of Ecklonia cava in LPS stimulated RAW macrophages. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, C.M.; Alves, M.G.C.F.; Will, L.S. A sulfated polysaccharide, fucans, isolated from brown algae Sargassum vulgare with anticoagulant, antithrombotic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Carbohyd. Polym. 2013, 91, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkova, T.A.; Kozlova, L.V.; Mikshina, P.V. Spatial structure of plant cell wall polysaccharides and its functional significance. Biochemistry. 2013, 78, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, S.; Schmitz, G. Plasmalogens the neglected regulatory and scavenging lipid species. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2011, 164, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, D.B.; Bao, W. Goetz, liver and testis of rats to characterize the toxicity of triazole fungicides. Toxicol. App. Pharmacol. 2006, 215, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Zhu, W.; LIU, D. Stereo selective Degradation of Tebuconazole in Rat Liver Microsomes. Chirality. 2012, 24, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho, E.; Villarroel, M.J.; Andreu, E.; Ferrando, M.D. Disturbances in energy metabolism of Daphnia magna after exposure to tebuconazole. Chemosphere. 2009, 74, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.S.; Vilela-Silva, A.; -C. E.S.; Valente, A.-P.; Mourao, P.A.S. A 2-sulfated, 3- linked α-l-galactan is an anticoagulant polysaccharide. Carbohydr. Res. 2002, 337, 2231–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, G.M.; Jose, M.G. In Vitro Antioxidant Properties of Edible Marine Algae. 2016.

- Hamzaoui, A.; Ghariani, M.; Sallem, I. Extraction characterization and biological properties of polysaccharide derived from green seaweed “Chaetomorpha linum” and its potential application in Tunisian beef sausages. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2020, 148, 1156–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ktari, N.; Feki, A.; Trabelsi, I. Triki, M. Structure, functional and antioxidant properties in Tunisian beef sausage of a novel polysaccharide from Trigonella foenum-graecum seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2017, 98, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ktari, N.; Trabelsi, I.; Bardaa, S. effects in rat cutaneous wound healing of a novel polysaccharide from fenugreek (Trigonella foenum- graecum) seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, H.; Han, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang. Structural characterization and immunostimulatory activity of a novel polysaccharide from green alga Caulerpa racemosa var peltata. Int. J. Biol. Macrom. 2019, 134, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, N.; Lahaye, M. Chemical and physico-chemical characterisation of fibres from Laminaria digitata (kombu breton): A physiological approach. J. Sci. Food. Acgr. 1991, 55, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xu, Sh.; Chen, L. Chemical composition and bioactivities of a water-soluble polysaccharide from the endodermis of shaddock. Int. J. Biol. Macrom. 2012, 51, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.A.; Kim, K.N. Antioxidative and antimicrobial activities of Sargassum muticum extracts, J Korean Soc. Food. Sci. Nut. 2007, 36, 663–669. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Kim, S.M. Characterization and immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides extracted from green alga Chlorella ellipsoidea. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammed, A.; Irwandi, J.; Senay, S.; Azura, A.; Zahangir, A. Chemical structure of sulfated polysaccharides from brown seaweed (Turbinaria turbinata). Int. J. Food. Prop. 2017, 20, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Robic, A.; Gaillard, C.D.; Sassi, J.F.O.; Lerat, Y.; Lahaye, M. Ultrastructureof ulvan: a polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biopolymers, 2009, 91, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, V.F.; Knutsen, S.H.; Usov, A.I.; Rollema, H.S.; Cerezo, A.S. 1H and 13C high resolution NMR spectroscopy of carrageenans: application in research and industry. Trends. Food. Sci. Technol. 2002, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Phyo, P.; Wang, T.; Xiao, C.; Anderson, C.T.; Hong, M. Effects of pectin molecular weight changes on the structure, dynamics, and polysaccharide interactions of primary cell walls of Arabidopsis thaliana: Insights from solid-state NMR. Biomacromolecules. 2017, 18, 2937–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, L.M. Chemical structural and chain conformational characterization of some bioactive polysaccharides isolated from natural sources. Carbohyd. Polymers. 2009, 76, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, M.S.; Oehninger, S.; Barnett, T.; Williams, R.L.; Clark, G.F. A revised structure for fucoidan may explain some of its biological activities. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 29, 21770–21776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Wu, F.J.; Du, L.; Li, G.Y.; Takahashi, K.; Xue, Y. Effects of polysaccharides from abalone (Haliotis discus hannai Ino) on HepG2 cell proliferation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 66, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichen, F.; Karoud, W.; Sila, A. Extraction, characterization and antimicrobial activity of sulfated polysaccharides from fish skins. Int. J. Biol. Macrom. 2015, 75, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, S.; Nie, S.; Yu, Q.; Xie, M. Reviews on mechanisms of in vitro antioxidant activity of polysaccharides. Ox. Med. Cell. Long. 2016, 5692852. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, L.P.; Shui, G. An Investigation of Antioxidant Capacity of Fruits in Singapore Markets. Food. Chem. 2002, 76, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskheli, M.; Arain, M.A.; Chaudhry, S.; Soomro, A.H.; Qureshi, T.A. PhysicoChemical Quality of Camel Milk. J. AGR. SOC. SCI. 2005, 1813–2235/2005/01–2–164–166.

- Ruperez, P.; Ahrazem, O.; Leal, J.A. Potential antioxidant capacity of sulfated polysaccharides from the edible marine brown seaweed Fucusve siculosus. J. Agr. Food. Chem. 2002, 50, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huimin, Q.; Tingting, Z.; Quanbin, Z.; Zhien, L.; Zengqin, Z.; Ronge, X. Antioxidant activity of different molecular weight sulfated polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa Kjellm (Chlorophyta). J. App. Phycol. 2005, 17, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.E.; Riedl, K.M.; Jones, G.A. High molecular weight plant phenolics (tannins) as biological antioxidants. J. Ag. Food. Chem. 1998, 46, 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.S.; Huang, G.J.; Lin, Y.H. Chang, Bot. Stud. 2008, 49, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Zh.; Li, Z. Antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide fractions extracted from Laminaria japonica/ Int. J. Biol. Macrom. 2008, 42, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, A.; Hamann, M. Marine compounds with anthelmintic, antibacterial, anticoagulant, antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antiplatelet, antiprotozoal, antituberculosis, and antiviral activities; affecting the cardiovascular, immune and nervous systems and other miscellaneous mechanisms of action. J. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2005, 140, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewsrithong, J.K.; Intarak, T.; Longpol, V.; Chairgulprasert, S.; Prasertsongsakun, C.; Chotimakorn, T.; Ohshima. Antibacterial activity and bioactive compounds of some brown algae from Thailand, In The Proceedings of JSPS-NRCT International Symposium Joint Seminar. 2007, 608-613.

- Belhaj, D.; Frikha, D.; Athmouni, K. ox-Behnken design for extraction optimization of crude polysaccharides from Tunisian Phormidium versicolor cyanobacteria (NCC 466): partial characterization, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Int. J. Biol. Mac. 2017, 06, 046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaj, D.; Elloumi, N.; Jerbi, B. Effects of sewage sludge fertilizer on heavy metal accumulation and consequent responses of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) Environ. Sci. Pol. Res. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bissell, M. Chronic liver injury, TGF-β, and cancer. Experim. Mol. Med. 2001, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, V.; Valle, C.; Chavez-Tapia, N.; Uribe, M.; Mendez-Sanchez, N. Role of Oxidative Stress and Molecular Changes in Liver Fibrosis: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 4850–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Saad, H.; Kharrat, N.; Krayem, N. Biological properties of Alsidium corallinum and its potential protective effects against damage caused by potassium bromate in the mouse liver. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2015, 23, 3809–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locckie, L.Z.; Meerman, J.H.N.; Commander, J.N.M.; Vermeulen, N.P.E. Biomarkers of free radical damage: application in experimental animals and in human. Free. Rad. Biol. Med. 26, 202–226. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, D. Antioxidant activities of different fractions of polysaccharide purified from Gynostemma pentaphyllum Makino. Carbohyd. Poly. 2007, 68, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Saad, H.; Driss, D.; Ellouz-Chaabouni, S. Vanillin mitigates potassium bromate-induced molecular, biochemical and histopathological changes in the kidney of adult mice. Chem. Biol. Inter. 2016, 252, 102–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knebe, C.; Neeb, J.; Zahn, E.F. Propiconazole, Tebuconazole, and Their Mixture on the Receptors CAR and PXR in Human Liver Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 163, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, N.; Zhou, G.; Lu, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z. In vivo antioxidant activity of polysaccharide fraction from Porphyra haitanesis (Rhodephyta) in aging mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2003, 48, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, X.; Ma, X.; Liu, L. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity in vitro of polysaccharides from angelica and astragalus. Carboh. Polym. 2016, 137, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, M.; Qi, T.; Zhao, Q. Antioxidant activity of different molecular weight sulfated polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa Kjellm (Chlorophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2005, 17, 527e 534527–34. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, L.; Fan, Y.; Yan, P.; Li, S.; Zhou, X. The effect of boletus polysaccharides on diabetic hepatopathy in rats. Chem. Biol. Inter. 2019, 308, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, T. Metabonomic profiling in study hepatoprotective effect of polysaccharides from Flammulina velutipes on carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury rats using GC–MS. Int. J. biol. Macromol. 2017, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmi, V.S.; Arun, A.R.; Muraleedhara, K.G. Sulfated polysaccharides from the edible marine algae Padina tetrastromatica attenuates isoproterenol-induced oxidative damage via activation of PI3K/ Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway - An in vitro and in vivo approach. Chem. Biol. Inter. 2019, 308, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L. In vivo protective effect of Porphyra yezoensispolysaccharide against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 49, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, N.; Liu, X. The structure of a sulfated galactan from Porphyra haitanensis and its in vivo antioxidant activity. Carbohyd. Res. 2004.339, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Badraoui, R.; Saoudi, M.; Hamadou, W.S.; Elkahoui, S.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Alam, J.A. Antiviral effects of Artemisinin and its derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Computational evidences and interactions with ACE2 allelic variants. Pharmaceuticals. 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akacha, A.; Badraoui, R.; Rebai, T.; Zourgui, L. Effect of Opuntia ficus indica extract on methotrexate-induced testicular injury: A biochemical, docking and histological study. J. Biomol. Str. Dynam. 2022, 40, 4341–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmouni, F.; Badraoui, R.; Ben-Nasr, H.; Bardakci, F.; Elkahoui, S. Pharmacokinetics and therapeutic potential of Teucrium polium against liver damage associated hepatotoxicity and oxidative injury in rats: computational, biochemical and histological studies. Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhadhbi, N.; Issaoui, N.; Hamadou, W.S.; Alam, J.M.; Elhadi, A.S; Adnan, M. Physico-Chemical Properties, Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and In-Vitro Pharmacological Study of a Cobalt (II) Complex Based on 2-Aminopyridine. Chemistry. Select 2022, 7, e202103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshidi, M.; Badraoui, R.; Adnan, M.; Patel, M.; Alotaibi, A.; Saeed, M. Phytochemical profiling, antibacterial, and antibiofilm activities of Sargassum sp.(brown algae) from the Red Sea: ADMET prediction and molecular docking analysis. Algal. Res. 2023, 69, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumi, E.; Ahmad, I.; Bouali, N.; Patel, H.; Ghannay, S.; ALrashidi, A.A. Thymus musilii Velen. Methanolic Extract: In Vitro and In Silico Screening of Its Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anti-Quorum Sensing, Antibiofilm, and Anticancer Activities. Life 2022, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Jin, C.; Tong, Z. Optimization extraction, characterization and antioxidant activities of pectic polysaccharide from tangerine peels. Carbohyd. Polymers. 2016, 136, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, W. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18. ed, AOAC, International, Gaithersburg, Md, 2005.

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenkrantz, N.; Asboe-Hansen, G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal. Biochem. 1973, 54, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuko, T.; Minami, A.; Iwasaki, N.; Majima, T.; Nishimura, S.I.; Lee, Y.C. Carbohydrate analysis by a phenol–sulfuric acid method in microplate format. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 339, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, N.; Kriaa, M.; Kammoun, R. Extraction and characterization of three polysaccharides extracted from Opuntia ficus indica cladodes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuder, P.; Hole, M.; Smith, G. Antioxidants from a heated histidine-glucose model system. I: investigation of the antioxidant role of histidine and isolation of antioxidants by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 1998, 75, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.J.; Rice-Evans, C.; Davies, M.J. A new method for measuring antioxidant activity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1993, 21, 95S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawole, O.A.; Opara, U.L.; Theron, K.I. Chemical and phytochemical properties and antioxidant activities of three pomegranate cultivars grown in South Africa. Food. Biop. Tec. 2012, 5, 2934–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcocci, L.; Maguire, J.J.; Droylefaix, M.T.; Packer, L. The nitric oxide-scavenging properties of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. Biochem. Biop. Res. Commun. 1994, 201, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson-Ehle, P.; Carlstrom, S.; Belfrage, P. Rapid effects on lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue of humans after carbohydrate and lipid intake: Time course and relation to plasma glycerol, triglyceride, and insulin levels. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1975, 35, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassole, I.; Ouattara, A.; Nebie, R. Chemical composition and antibacterial activities of the essential oils of Lippia chevalieri and Lippia multiflora from Burkina Faso. Phytochemistry 62, 209–212. [CrossRef]

- Zucconi, F.A.; Monaco, M. Phytotoxins during the stabilization of organic matter. In: Gasser J.K. R. (Editor), Composting of Agricultural and other Wastes, Elsevier Applied Science Publication, New York, NY, U.S.A 1985, 73- 86.

- Council of European Communities Council Directive 86/609/EEC of 24 November, on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes. Off.J. Eur. Commun. 1986, 358, 1–18.

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, L.A.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Chem. Biol. 1951, 193, 65–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, H.H. , Hadley, M., Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid peroxidation. Methods. Enzymol. 1990, 186, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, P.; Wolff, S.P. A discontinuous method for catalase determination at near physiological concentrations of H2O2 and its application to the study of H2O2 fluxes within cells. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 1996, 31, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witko, V.; Nguyen, A.T.; Descamps-Latscha, B. Microtiter plate assay for phagocyte-derived taurine chloramines. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 1992, 6, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: improve assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohe, L.; Gunzler, W.A. Assays of glutathione peroxidase. Methods. Enzymol. 1984, 105, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophysic. 1959, 82, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jollow, D.J.; Mitchell, J.R.; Zampaglione, N.; Gillete, J.R. Bromobenzene induced liver necrosis: protective role of glutathione and evidence for 3,4 bromobenzeneoxide as the hepatotoxic intermediate. Pharmacology. 1974, 11, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Monosaccharides composition of ACPs performed by HPLC-FID.

Figure 1.

Monosaccharides composition of ACPs performed by HPLC-FID.

Figure 2.

(A) 1H NMR and Solid state 13C NMR spectra of ACPs.

Figure 2.

(A) 1H NMR and Solid state 13C NMR spectra of ACPs.

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectra of ACPs.

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectra of ACPs.

Figure 4.

(A) DPPH radical-scavenging activity of ACPs; (B) Metal ion-chelating activity of ACPs; (C) Reducing power activity of ACPs; (D) Ferric reducing antioxidant power of ACPs.

Figure 4.

(A) DPPH radical-scavenging activity of ACPs; (B) Metal ion-chelating activity of ACPs; (C) Reducing power activity of ACPs; (D) Ferric reducing antioxidant power of ACPs.

Figure 5.

Diffusion test on agar. A: E. coli, B: S. enterica, C: L. invanovii, D: P. aeruginosa, E: M. luteus and F: S. aureus.

Figure 5.

Diffusion test on agar. A: E. coli, B: S. enterica, C: L. invanovii, D: P. aeruginosa, E: M. luteus and F: S. aureus.

Figure 6.

Effects of ACPs on the seed germination (%).

Figure 6.

Effects of ACPs on the seed germination (%).

Figure 7.

Effects of ACPs on liver function enzymes. (A) plasma AST activity, (B) plasma ALT activity, and (C) plasma bilirubin levels.

Figure 7.

Effects of ACPs on liver function enzymes. (A) plasma AST activity, (B) plasma ALT activity, and (C) plasma bilirubin levels.

Figure 8.

Effects of ACPs on plasma lipide profile. (A) Total cholesterol levels, (B) triglyceride levels, (C) HDL-C levels, and (D) LDL-C levels.

Figure 8.

Effects of ACPs on plasma lipide profile. (A) Total cholesterol levels, (B) triglyceride levels, (C) HDL-C levels, and (D) LDL-C levels.

Figure 9.

Light microscopic photographs of liver’s paraffin section stained with H&E taken at 200x magnifications. (A) Control; (B,C) TBZ; (D) TBZ+ACPs; (E) ACPs, (F,G) Histological NAS scores of liver tissue.

Figure 9.

Light microscopic photographs of liver’s paraffin section stained with H&E taken at 200x magnifications. (A) Control; (B,C) TBZ; (D) TBZ+ACPs; (E) ACPs, (F,G) Histological NAS scores of liver tissue.

Figure 10.

A proposed schematic diagram illustrating the protective mechanism of ACPs against TBZ hepatotoxicity.

Figure 10.

A proposed schematic diagram illustrating the protective mechanism of ACPs against TBZ hepatotoxicity.

Figure 11.

3D photographs of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides complexed with the ribbon structure of 1JIJ, 1HD2 and 1WL4 receptors.

Figure 11.

3D photographs of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides complexed with the ribbon structure of 1JIJ, 1HD2 and 1WL4 receptors.

Figure 12.

2D diagram of interactions of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides. (A) Diagram of interaction of galactose with 1JIJ, which possessed the best binding score (–7.1 kcal/mol). (B) Diagram of interaction of galactose with 1WL4, which established the highest number of conventional H-bonds (n = 7).

Figure 12.

2D diagram of interactions of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides. (A) Diagram of interaction of galactose with 1JIJ, which possessed the best binding score (–7.1 kcal/mol). (B) Diagram of interaction of galactose with 1WL4, which established the highest number of conventional H-bonds (n = 7).

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of ACPs.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of ACPs.

| Parameters |

ACPs |

| Yield (%) |

12.63±1.39 |

| pH |

6.20±0.20 |

| Moisture (%) |

2.96±0.09 |

| Ash (%) |

3.00±0.08 |

| Proteins (%) |

1.94±0.07 |

| Uronic acid (%) |

12.06±1.74 |

| Carbohydrates (%) |

66.06±4.69 |

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of ACPs.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of ACPs.

| Microorganisms |

DD (mm) ACPs |

DD (10μg /disque) |

MIC (µg/mL) |

MBC (µg/mL) |

R |

| E. coli |

9.66± 0.50 |

28 |

100 |

50 |

2 |

| S.enterica |

9.33± 0.70 |

21 |

100 |

100 |

1 |

| P. aeruginosa |

9.55± 1.00 |

39 |

100 |

100 |

1 |

| M. luteus |

9.66± 0.50 |

15 |

100 |

100 |

1 |

| L. invanovii |

9.00± 1.00 |

25 |

100 |

100 |

1 |

| S. aureus |

10.66 ± 0.10 |

23 |

50 |

100 |

2 |

Table 3.

Effect of ACPs on toxicity markers in hepatic tissue of TBZ treated rats.

Table 3.

Effect of ACPs on toxicity markers in hepatic tissue of TBZ treated rats.

| Parameters and treatments |

Control |

TBZ |

TBZ + ACPs |

ACPs |

| MDA (µmol of MDA/mg protein) |

90.86±16.47a

|

187.24±6.10c |

148.79±11.54b

|

114.82±15.83a

|

|

H2O2 (µmol/mg protein) |

0.07±0.01 |

0.12±0.01c

|

0.09±0.03b

|

0.08±0.02a

|

| AOPPs (nmol/mg protein) |

0.59±0.07a |

0.86±0.08b

|

0.77±0.06b

|

0.63±0.1a

|

| GPx (nmol GSH/ min/mg protein) |

6.11±1.13b

|

3.60±0.59a |

4.65±0.97ab

|

5. 64±0.39 b |

| SOD (units/mg protein) |

23.34±4.22b

|

12.76±4.17b

|

18.43±2.11b

|

25.62±2.62b

|

| GSH (nmol/mg protein) |

20.35±4.65b

|

11.383.13b

|

14.35±3.54b

|

18.08±2.56b

|

Table 4.

Binding affinity, conventional hydrogen bonds and interacting residues of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides complexed with 1JIJ, 1HD2 and 1WL4 receptors.

Table 4.

Binding affinity, conventional hydrogen bonds and interacting residues of Alsidium corallinum monosaccharides complexed with 1JIJ, 1HD2 and 1WL4 receptors.

| Monosaccharide (Ligand) |

Intermolecular interactions |

| Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) |

No.

H-Bond |

Closest Interacting

Residues (Distance, Å) |

Closest Interacting Residue |

| TyrRS from S. aureus (1JIJ) |

| Glucoronic acid |

–5.8 |

4 |

Lys226 (2.155), Lys226 (2.112), Gly233 (2.446), Lys234 (2.721), Lys234 (3.468) |

Lys226:HZ3 |

| Glucose |

–7.0 |

8 |

Asn124 (2.835), Gln174 (2.131), Asp80 (2.449), Gln196 (2.745), Asp40 (2.216), Tyr36 (2.241), Gln190 (2.511), Asp177 (1.898) |

Asp177:OD1 |

| Galactose |

–7.1 |

7 |

Tyr170 (2.845), Tyr170 (2.678), Gln196 (2.478), Asp80 (2.185), Gln196 (2.197), Asp80 (2.039), Gln196 (2.565) |

Asp80:OD2 |

| Fructose |

–6.6 |

5 |

Asp80 (2.752), Gln196 (2.824), Thr75 (2.171), Tyr170 (2.402), Tyr36 (2.647) |

Tyr75:OG1 |

| Human peroxiredoxin (1HD2) |

| Glucoronic acid |

–5.3 |

6 |

Asn21 (2.581), Asn21 (2.362), Arg86 (3.037), Arg86 (2.250), Gly92 (2.173), Leu96 (2.735), Gly82 (3.541), Glu91 (3.550) |

Gly92:HN |

| Glucose |

–5.4 |

4 |

Asn76 (2.064), Asn122 (2.303), Asp77 (2.368), Asp77 (2.432) |

Asn76:HD21 |

| Galactose |

–5.1 |

5 |

Asn76 (2.077), Asp77 (2.309), Arg124 (2.861), Arg124 (2.431), Asp77 (2.579), Asp77(2.488) |

Asn76:HD21 |

| Fructose |

–5.3 |

5 |

Gly17 (3.034), Gly92 (2.823), Val94 (2.584), Thr81 (2.738), Leu96 (2.998), Glu16 (3.557) |

Val94:O |

| Acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT, 1WL4) |

| Glucoronic acid |

–5.2 |

3 |

Asn68 (2.254), Ser87 (2.125), Ser87 (1.771), Gly66 (3.694) |

Ser87:HG |

| Glucose |

–4.9 |

5 |

Thr36 (2.454), Asp32 (2.429), Asp32 (2.495), Asp32 (2.468), Leu206 (2.527), Ser35 (3.564), Gly76 (3.650) |

Asp32:OD1 |

| Galactose |

–4.9 |

7 |

Arg223 (2.284), Arg223 (2.036), Asn227 (2.563), Asn227 (2.688), Met231 (2.864), Asn227 (2.369), Gly225 (2.553) |

Arg223:HH21 |

| Fructose |

–4.9 |

5 |

Ser208 (1.870), Ser208 (2.117), Ser208 (1.880), Ser208 (3.072), Asp32 (1.916) |

Ser208:HN |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).