Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

28 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The samples and datasets

2.2. Probe identification

2.3. Sensitivity, specificity, and sample classification in TCGA data

2.4. Blood sample simulations

2.5. Calculation of positive predictive value

2.6. PCR assay and sequencing

| ZNF154 | |

| Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| 5’-GGTTTTTATTTTAGGTTTGA-3’ | 5’-AAATCTATAAAAACTACATTACCTAAAATACTCTA-3’ |

| Genomic position | Amplicon size (incl. primers) |

| Chr19: 58220404-58220705 (+ strand) | 302 bp (20 CpGs) |

| TLX1 | |

| Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| 5’-TTTTTAGTTTAGGTTTTATGGGGTAG-3’ | 5’-AAAACCATAACTTCCTTTATAACCC-3’ |

| Genomic position | Amplicon size (incl. primers) |

| Chr10: 102894992-102895165 (+ strand) | 174 bp (13 CpGs) |

| GALR1 | |

| Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| 5’-GGGAGTTTTTTTTGTAGGAGT-3’ | 5’-AAAACACTAAAATCCCCTTCC-3’ |

| Genomic position | Amplicon size (incl. primers) |

| Chr18: 74961979-74962242 (+ strand) | 264 bp (27 CpGs) |

- -

- Forward adapter: 5′-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′,

- -

- Reverse adapter: 5′-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′.

2.7. EpiClass procedure to assess marker performance in plasma samples

3. Results

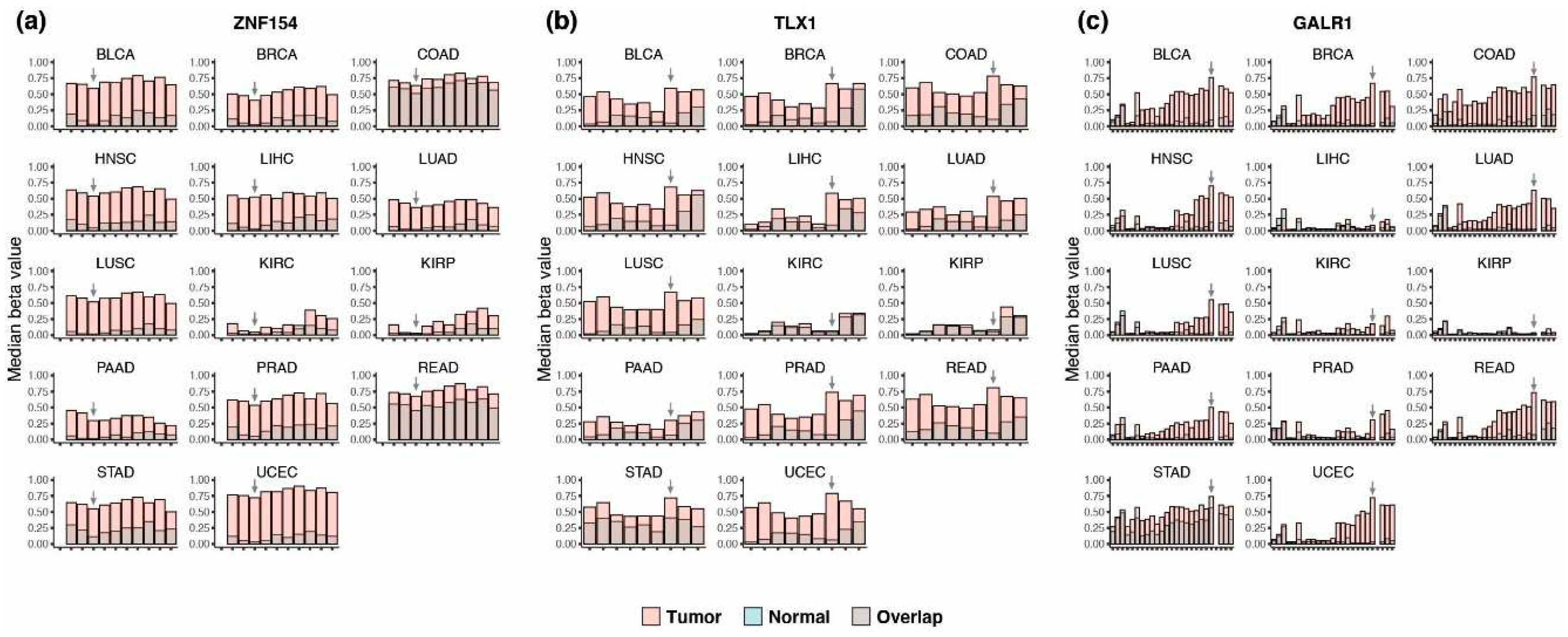

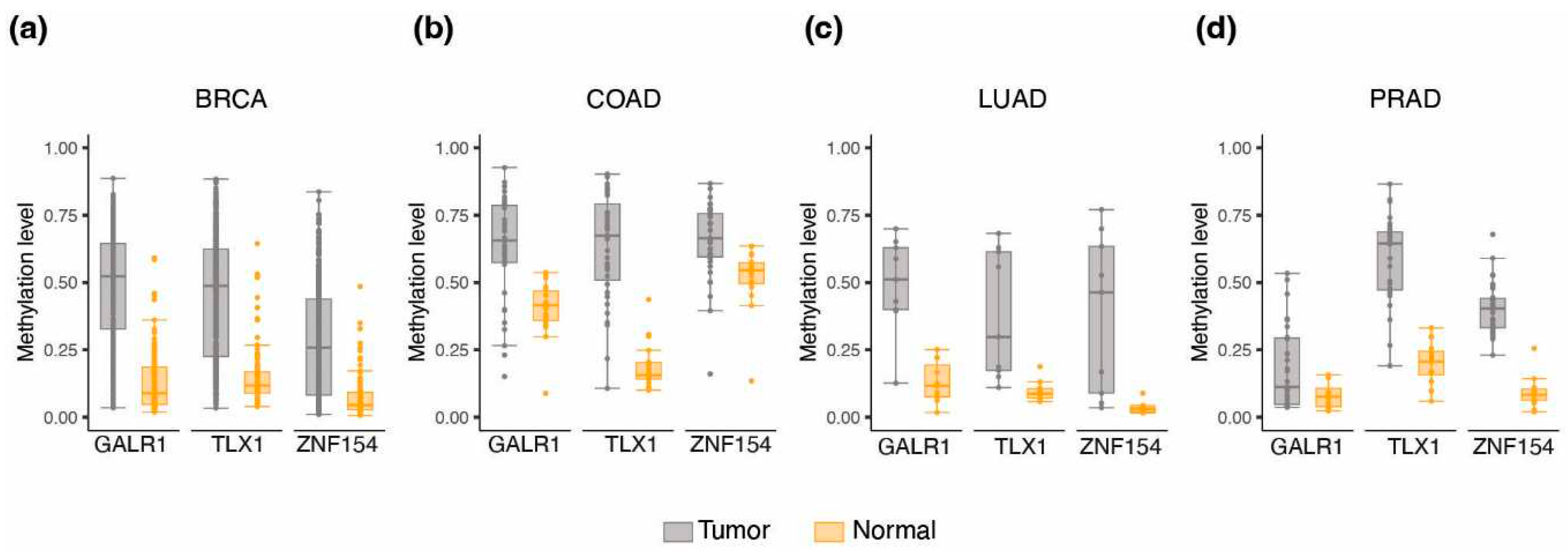

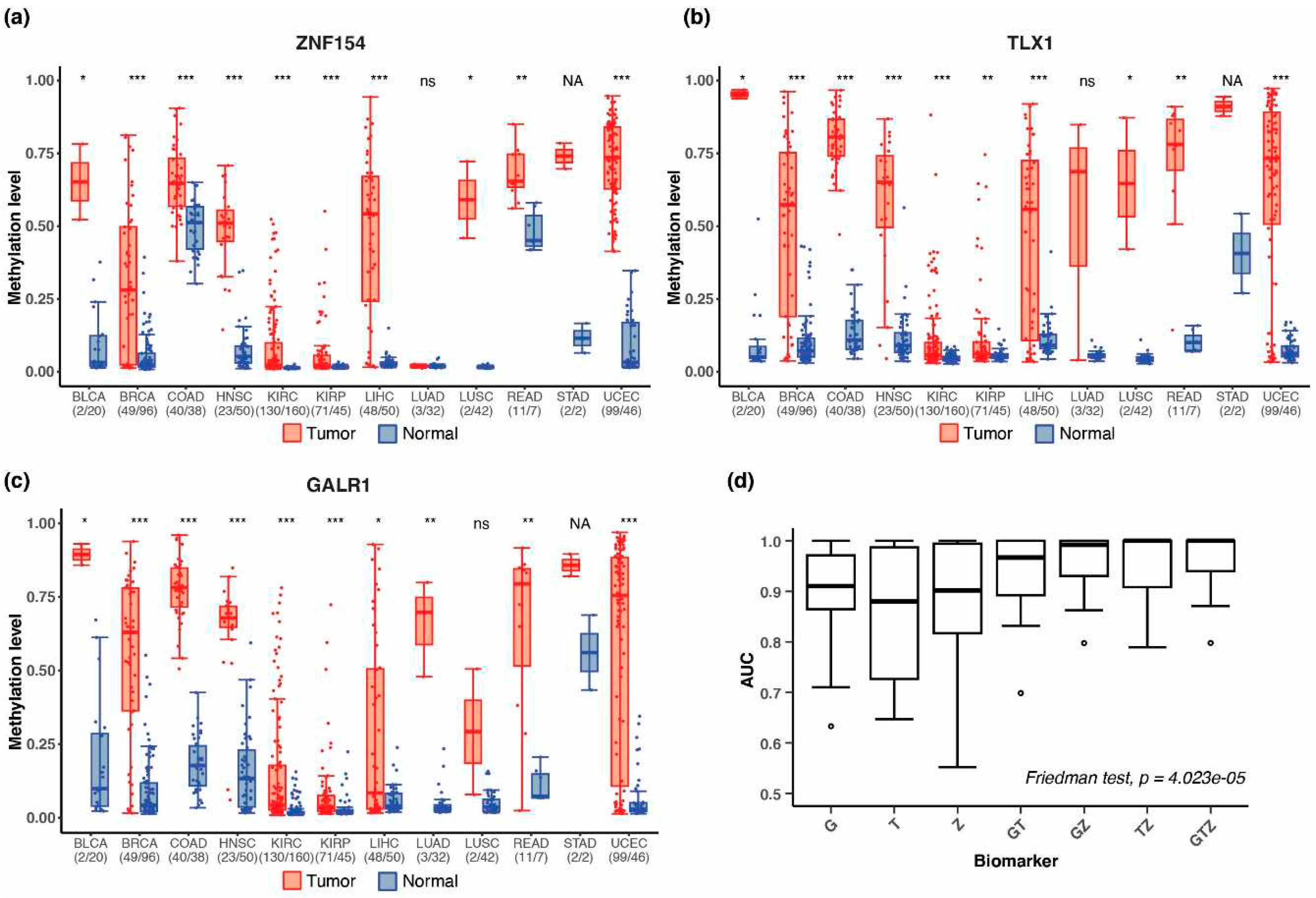

3.1. Discovery of multi-cancer methylation biomarkers in TCGA data

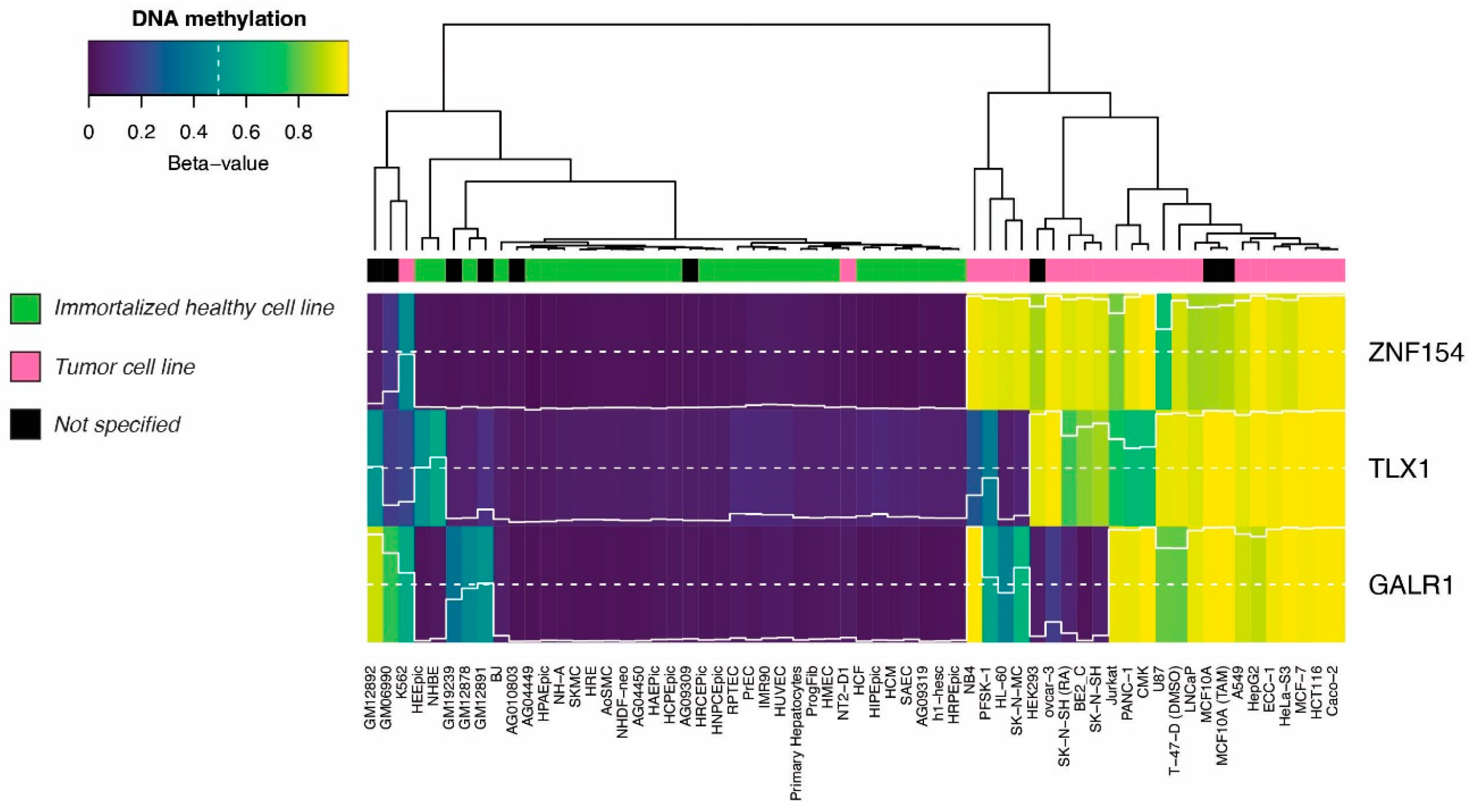

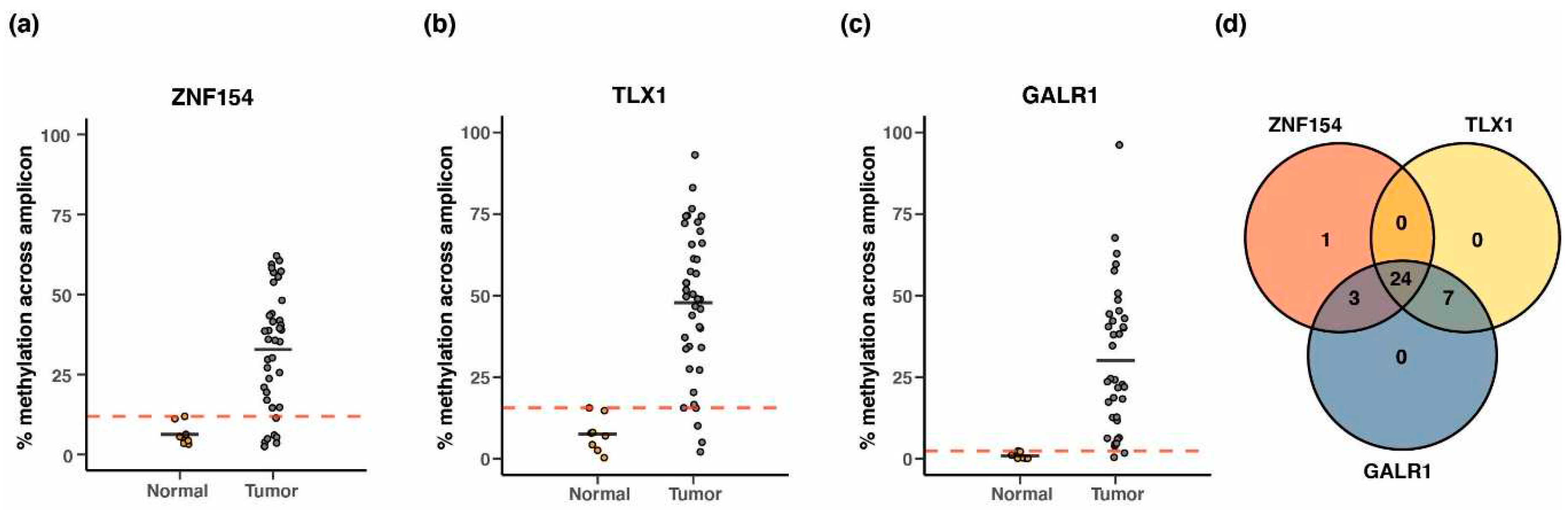

3.2. Methylation at TLX1, GALR1, and ZNF154 in tumor and normal karyotype cell lines

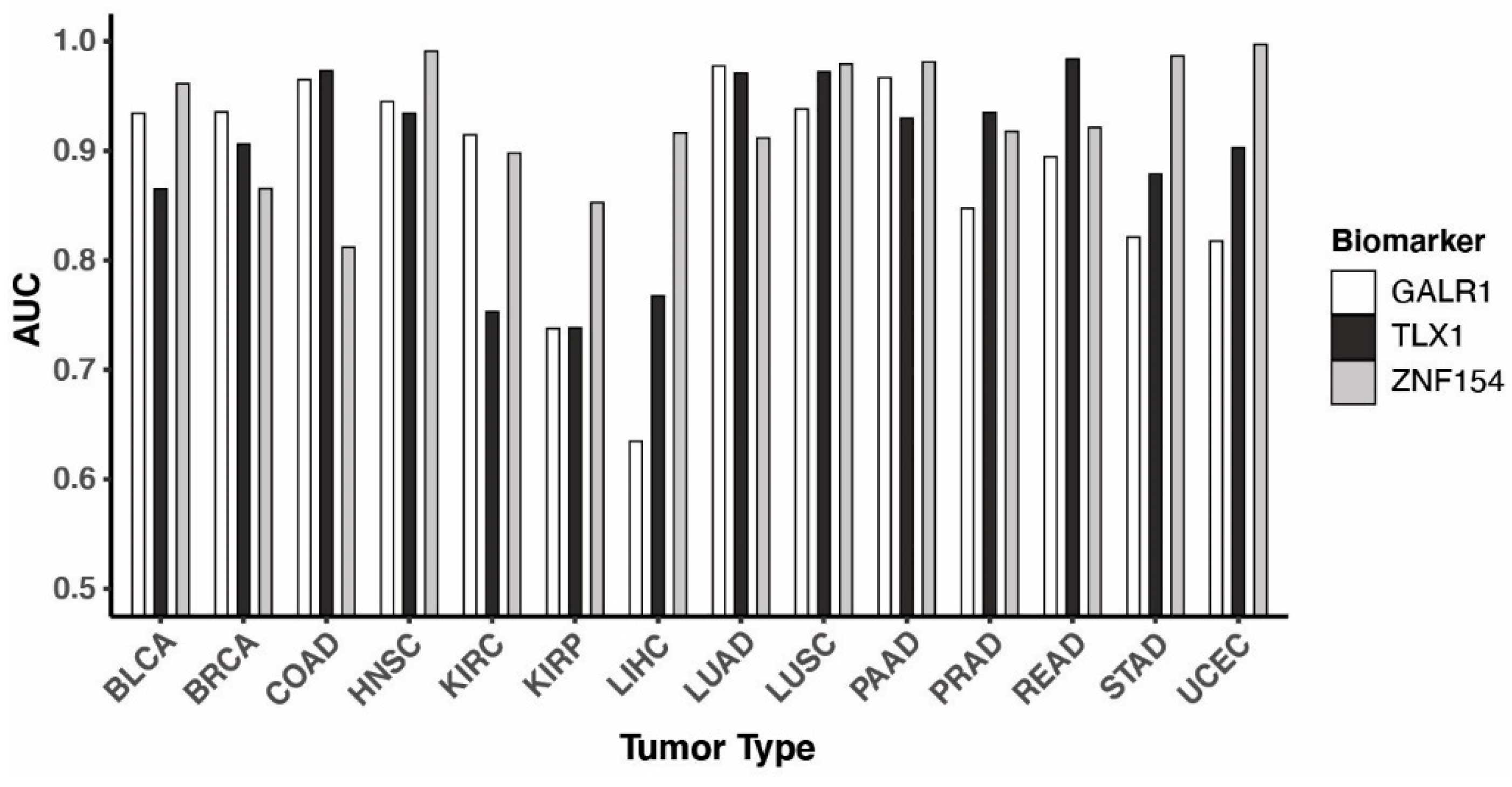

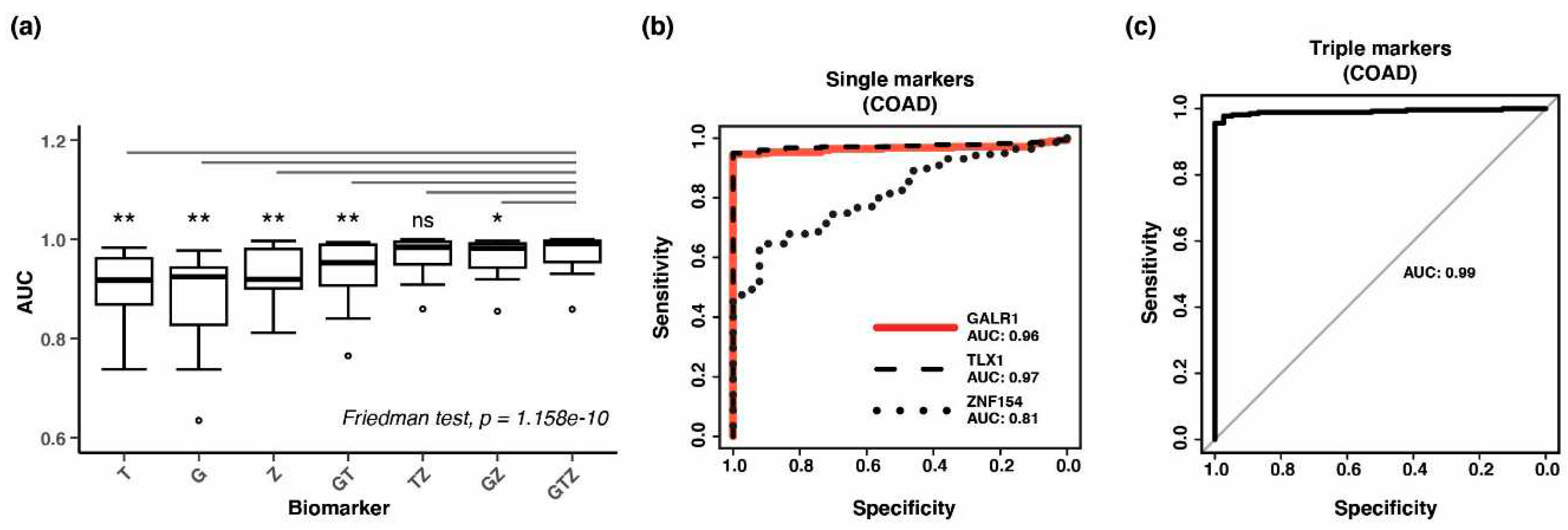

3.3. Performance of the three biomarkers individually

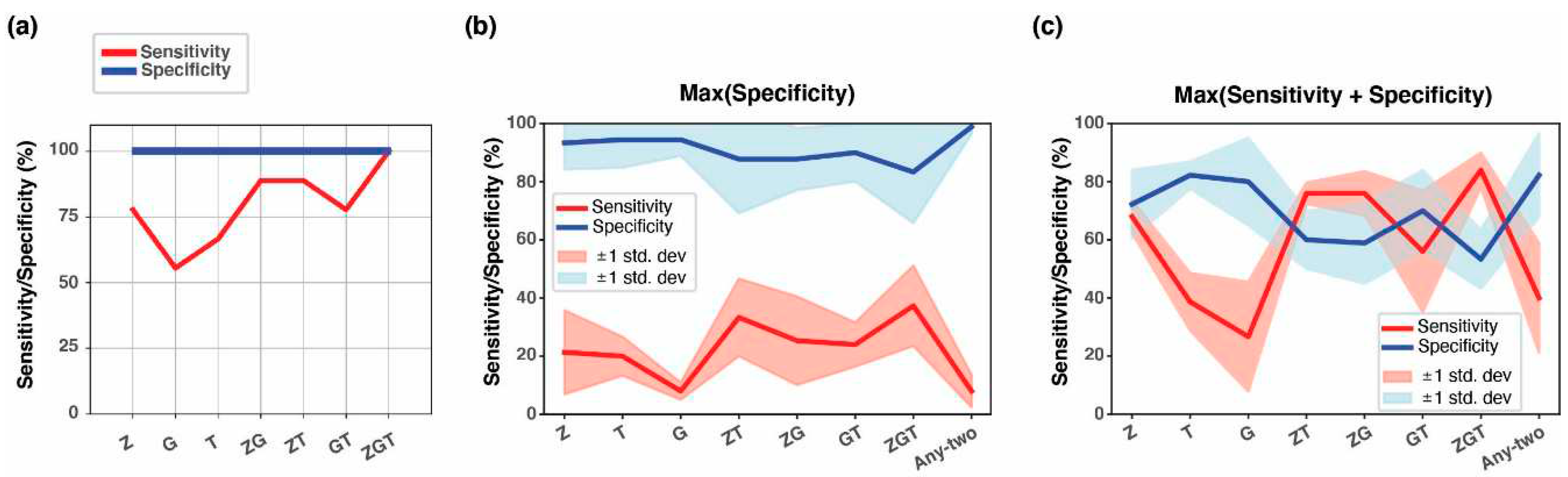

3.4. Combining methylation biomarkers into multi-marker assays

3.5. Validation of three-marker combination in independent tumor datasets

3.6. Methylation at TLX1, GALR1, and ZNF154 in early tumorigenesis

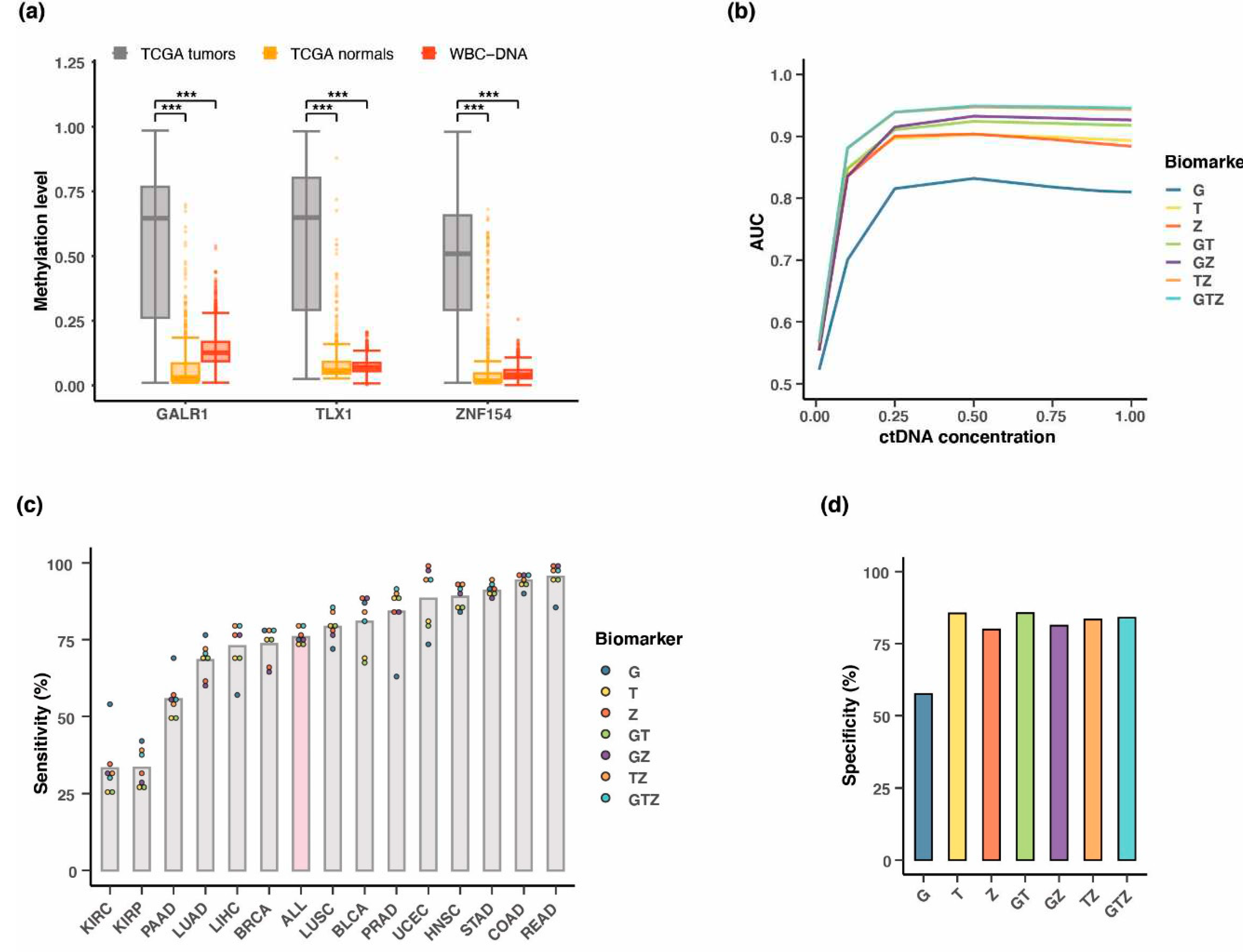

3.7. Testing multi-cancer assay performance in simulated blood samples

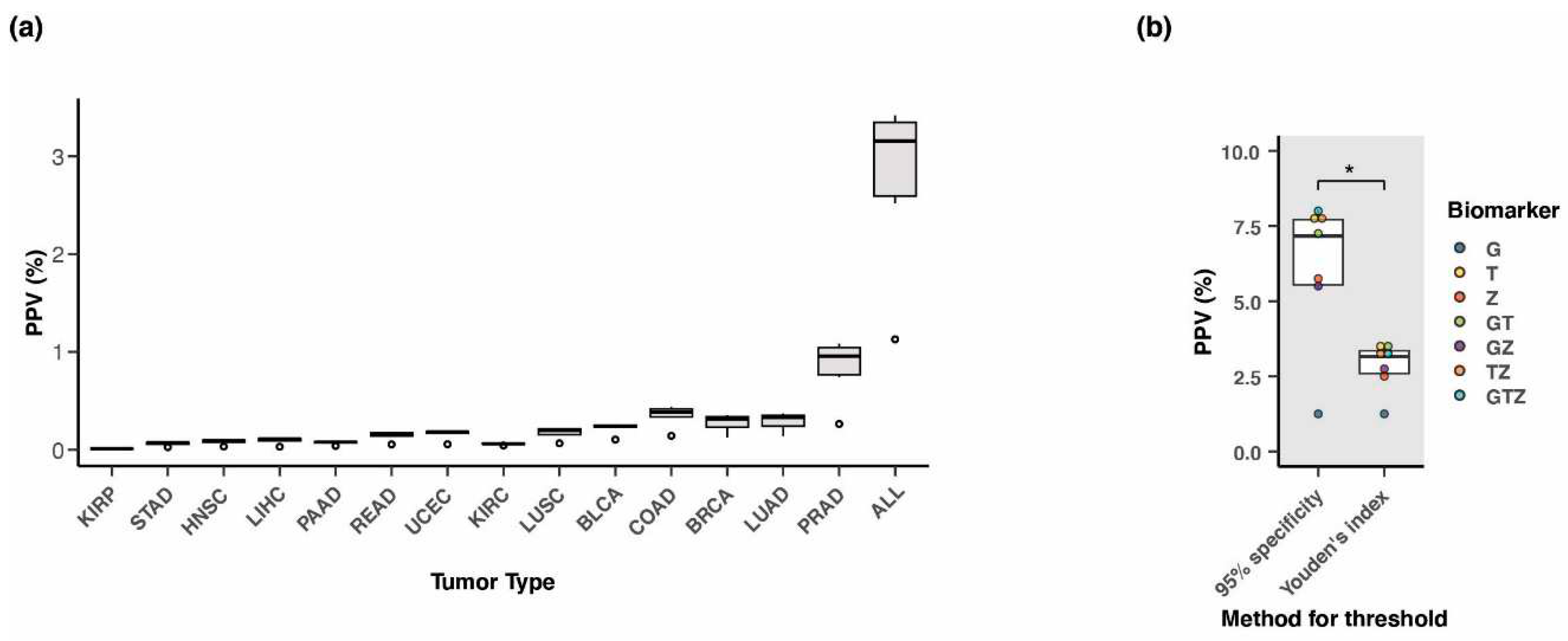

3.8. Positive predictive value of the three-marker combination

3.9. Performance of three-marker combination in cancer tissue

3.10. Testing of the three biomarkers in patient plasma using whole genome bisulfite sequencing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, R.C.; Haynes, K.; Du, S.; Barron, J.; Katz, A.J. Association of Cancer Screening Deficit in the United States With the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Oncol 2021, 7, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, D.C.; Sahin, T.K.; Yildirim, H.C.; Cesmeci, E.; Incesu, F.G.G.; Tahillioglu, Y.; Ucgul, E.; Aksun, M.S.; Gurbuz, S.C.; Aktepe, O.H.; et al. Newly diagnosed cancer and the COVID-19 pandemic: tumour stage migration and higher early mortality. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland-Frei. Cancer Medicine, 6th edition; Donald W Kufe, M., Raphael E Pollock, M., PhD, , Ralph R Weichselbaum, M., Robert C Bast, J., MD, T, ed S Gansler, M., MBA, , James F Holland, M., ScD , Emil Frei, I., MD, Eds. BC Decker: Hamilton (ON), 2003.

- Smith, R.A.; Andrews, K.S.; Brooks, D.; Fedewa, S.A.; Manassaram-Baptiste, D.; Saslow, D.; Wender, R.C. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2019, 69, 184–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, U.S.P.S.T.; Krist, A.H.; Davidson, K.W.; Mangione, C.M.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; Davis, E.M.; Donahue, K.E.; Doubeni, C.A.; et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021, 325, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhail, S.; Johnson, S.; Greenberg, D.; Peake, M.; Rous, B. Stage at diagnosis and early mortality from cancer in England. Br J Cancer 2015, 112 Suppl 1, S108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, S.J.; King, J.B.; German, R.R.; Richardson, L.C.; Plescia, M. Surveillance of screening-detected cancers (colon and rectum, breast, and cervix) - United States, 2004-2006. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002) 2010, 59, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Loud, J.T.; Murphy, J. Cancer Screening and Early Detection in the 21(st) Century. Seminars in oncology nursing 2017, 33, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J. Diagnosing cancer early is vital, new figures show. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2016, 353, i3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabieres, C.; Pantel, K. Liquid Biopsy: From Discovery to Clinical Application. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.H.; Tokheim, C.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Sengupta, S.; Bertrand, D.; Weerasinghe, A.; Colaprico, A.; Wendl, M.C.; Kim, J.; Reardon, B.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 2018, 173, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, I.R.; Takahashi, K.; Futreal, P.A.; Chin, L. Emerging patterns of somatic mutations in cancer. Nature reviews. Genetics 2013, 14, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, Y.M. Pan-cancer analysis of somatic mutations and transcriptomes reveals common functional gene clusters shared by multiple cancer types. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Ulrich, B.C.; Supplee, J.; Kuang, Y.; Lizotte, P.H.; Feeney, N.B.; Guibert, N.M.; Awad, M.M.; Wong, K.K.; Janne, P.A.; et al. False-Positive Plasma Genotyping Due to Clonal Hematopoiesis. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2018, 24, 4437–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shames, D.S.; Girard, L.; Gao, B.; Sato, M.; Lewis, C.M.; Shivapurkar, N.; Jiang, A.; Perou, C.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Pollack, J.R.; et al. A genome-wide screen for promoter methylation in lung cancer identifies novel methylation markers for multiple malignancies. PLoS medicine 2006, 3, e486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, P.; Jensen, T.; Oshiro, M.M.; Watts, G.S.; Kim, C.J.; Futscher, B.W. Agglomerative epigenetic aberrations are a common event in human breast cancer. Cancer research 2008, 68, 8616–8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyn, H.; Esteller, M. DNA methylation profiling in the clinic: applications and challenges. Nature reviews. Genetics 2012, 13, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, A.P.; Ohlsson, R.; Henikoff, S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nature reviews. Genetics 2006, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Vega, F.; Gotea, V.; Petrykowska, H.M.; Margolin, G.; Krivak, T.C.; DeLoia, J.A.; Bell, D.W.; Elnitski, L. Recurrent patterns of DNA methylation in the ZNF154, CASP8, and VHL promoters across a wide spectrum of human solid epithelial tumors and cancer cell lines. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, G.; Petrykowska, H.M.; Jameel, N.; Bell, D.W.; Young, A.C.; Elnitski, L. Robust Detection of DNA Hypermethylation of ZNF154 as a Pan-Cancer Locus with in Silico Modeling for Blood-Based Diagnostic Development. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD 2016, 18, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.F.; Petrykowska, H.M.; Elnitski, L. Assessing ZNF154 methylation in patient plasma as a multicancer marker in liquid biopsies from colon, liver, ovarian and pancreatic cancer patients. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.F.; Pisanic Ii, T.R.; Margolin, G.; Petrykowska, H.M.; Athamanolap, P.; Goncearenco, A.; Osei-Tutu, A.; Annunziata, C.M.; Wang, T.H.; Elnitski, L. Leveraging locus-specific epigenetic heterogeneity to improve the performance of blood-based DNA methylation biomarkers. Clinical epigenetics 2020, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Marabita, F.; Lechner, M.; Bartlett, T.; Tegner, J.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Beck, S. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013, 29, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehne, B.; Drong, A.W.; Loh, M.; Zhang, W.; Scott, W.R.; Tan, S.T.; Afzal, U.; Scott, J.; Jarvelin, M.R.; Elliott, P.; et al. A coherent approach for analysis of the Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip improves data quality and performance in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome biology 2015, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terunuma, A.; Putluri, N.; Mishra, P.; Mathé, E.A.; Dorsey, T.H.; Yi, M.; Wallace, T.A.; Issaq, H.J.; Zhou, M.; Killian, J.K.; et al. MYC-driven accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate is associated with breast cancer prognosis. The Journal of clinical investigation 2014, 124, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsham, M.J.; Chitale, D.; Chen, K.M.; Datta, I.; Divine, G. Cell signaling events differentiate ER-negative subtypes from ER-positive breast cancer. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England) 2015, 32, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Jones, A.; Fasching, P.A.; Ruebner, M.; Beckmann, M.W.; Widschwendter, M.; Teschendorff, A.E. The integrative epigenomic-transcriptomic landscape of ER positive breast cancer. Clinical epigenetics 2015, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timp, W.; Bravo, H.C.; McDonald, O.G.; Goggins, M.; Umbricht, C.; Zeiger, M.; Feinberg, A.P.; Irizarry, R.A. Large hypomethylated blocks as a universal defining epigenetic alteration in human solid tumors. Genome medicine 2014, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Schenkel, L.C.; Ainsworth, P.; Lin, H.; Rodenhiser, D.I.; Cutz, J.C.; Sadikovic, B. Genomic DNA Methylation-Derived Algorithm Enables Accurate Detection of Malignant Prostate Tissues. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Li, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Park, S.; Lee, G.; Grimes, B.; Krysan, K.; Yu, M.; Wang, W.; et al. CancerLocator: non-invasive cancer diagnosis and tissue-of-origin prediction using methylation profiles of cell-free DNA. Genome biology 2017, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, Q.; Kang, S.; Same, M.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, C.C.; Matsuoka, L.; Sher, L.; Wong, W.H.; et al. CancerDetector: ultrasensitive and non-invasive cancer detection at the resolution of individual reads using cell-free DNA methylation sequencing data. Nucleic acids research 2018, 46, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.C.; Jiang, P.; Chan, C.W.; Sun, K.; Wong, J.; Hui, E.P.; Chan, S.L.; Chan, W.C.; Hui, D.S.; Ng, S.S.; et al. Noninvasive detection of cancer-associated genome-wide hypomethylation and copy number aberrations by plasma DNA bisulfite sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 18761–18768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzer, E.; Auinger, L.; Speicher, M.R. Cell-Free DNA and Apoptosis: How Dead Cells Inform About the Living. Trends Mol Med 2020, 26, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F.; Andrews, S.R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2011, 27, 1571–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, E.P. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P.W.; Damjanov, I.; Simon, D.; Banting, G.S.; Carlin, C.; Dracopoli, N.C.; Føgh, J. Pluripotent embryonal carcinoma clones derived from the human teratocarcinoma cell line Tera-2. Differentiation in vivo and in vitro. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 1984, 50, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Jiang, P.; Chan, K.C.; Wong, J.; Cheng, Y.K.; Liang, R.H.; Chan, W.K.; Ma, E.S.; Chan, S.L.; Cheng, S.H.; et al. Plasma DNA tissue mapping by genome-wide methylation sequencing for noninvasive prenatal, cancer, and transplantation assessments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 112, E5503–E5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underhill, H.R.; Kitzman, J.O.; Hellwig, S.; Welker, N.C.; Daza, R.; Baker, D.N.; Gligorich, K.M.; Rostomily, R.C.; Bronner, M.P.; Shendure, J. Fragment Length of Circulating Tumor DNA. PLoS genetics 2016, 12, e1006162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzer, E.; Haque, I.S.; Roberts, C.E.S.; Speicher, M.R. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nature reviews. Genetics 2019, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, M.; Singh, S.; Singh, P.; Chauhan, P.; Zaidi, M.A. Tumor markers: A diagnostic tool. National journal of maxillofacial surgery 2016, 7, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Gonzalez, A.; Cunquero Tomas, A.J.; Calabuig Farinas, S.; Ferrero, M.; Mirda, D.; Sirera, R.; Jantus-Lewintre, E.; Camps, C. A profile on cobas(R) EGFR Mutation Test v2 as companion diagnostic for first-line treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2020, 20, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighl, N.B.; Page, R.D.; Raymond, V.M.; Daniel, D.B.; Divers, S.G.; Reckamp, K.L.; Villalona-Calero, M.A.; Dix, D.; Odegaard, J.I.; Lanman, R.B.; et al. Clinical Utility of Comprehensive Cell-free DNA Analysis to Identify Genomic Biomarkers in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2019, 25, 4691–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, R.; Li, M.; Hughes, J.; Delfosse, D.; Skoletsky, J.; Ma, P.; Meng, W.; Dewal, N.; Milbury, C.; Clark, T.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne Liquid CDx, a novel 324-Gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PloS one 2020, 15, e0237802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Oxnard, G.R.; Klein, E.A.; Swanton, C.; Seiden, M.V.; Consortium, C. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.D.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Thoburn, C.; Afsari, B.; Danilova, L.; Douville, C.; Javed, A.A.; Wong, F.; Mattox, A.; et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2018, 359, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phallen, J.; Sausen, M.; Adleff, V.; Leal, A.; Hruban, C.; White, J.; Anagnostou, V.; Fiksel, J.; Cristiano, S.; Papp, E.; et al. Direct detection of early-stage cancers using circulating tumor DNA. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durinck, K.; Van Loocke, W.; Van der Meulen, J.; Van de Walle, I.; Ongenaert, M.; Rondou, P.; Wallaert, A.; de Bock, C.E.; Van Roy, N.; Poppe, B.; et al. Characterization of the genome-wide TLX1 binding profile in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2015, 29, 2317–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, K.; Ueda, Y.; Kanazawa, T.; Misawa, Y.; Jang, I.; Brenner, J.C.; Ogawa, T.; Takebayashi, S.; Grenman, R.A.; Herman, J.G.; et al. Epigenetic inactivation of galanin receptor 1 in head and neck cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2008, 14, 7604–7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shu, P.; Wang, S.; Song, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, C.; Ran, L. ZNF154 is a promising diagnosis biomarker and predicts biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer. Gene 2018, 675, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, T.; Modin, C.; Castano, F.M.; Lamy, P.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Hansen, L.L.; Wiuf, C.; Borre, M.; Dyrskjøt, L.; Orntoft, T.F. Comprehensive genome methylation analysis in bladder cancer: identification and validation of novel methylated genes and application of these as urinary tumor markers. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2011, 17, 5582–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, S.A.; Bashir, M.U.; Yaqinuddin, A. Utility of DNA methylation markers for diagnosing cancer. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2010, 8, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissa, D.; Robles, A.I. Methylation analyses in liquid biopsy. Translational lung cancer research 2016, 5, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsey, J.H.; Silvestro, A.; Barrett, J.C.; Bramlett, K.; Chudova, D.; Deras, I.; Dickey, J.; Hicks, J.; Johann, D.J.; Leary, R.; et al. Generic Protocols for the Analytical Validation of Next-Generation Sequencing-Based ctDNA Assays: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the BloodPAC's Analytical Variables Working Group. Clinical chemistry 2020, 66, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, T.F.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Levin, T.R.; Lavin, P.; Lidgard, G.P.; Ahlquist, D.A.; Berger, B.M. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberle, D.R.; DeMello, S.; Berg, C.D.; Black, W.C.; Brewer, B.; Church, T.R.; Clingan, K.L.; Duan, F.; Fagerstrom, R.M.; Gareen, I.F.; et al. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.A.; Richards, D.; Cohn, A.; Tummala, M.; Lapham, R.; Cosgrove, D.; Chung, G.; Clement, J.; Gao, J.; Hunkapiller, N.; et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, F.; Li, M.; Dressman, D.; He, Y.; Shen, D.; Szabo, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Goodman, S.N.; David, K.A.; Juhl, H.; et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 16368–16373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahr, S.; Hentze, H.; Englisch, S.; Hardt, D.; Fackelmayer, F.O.; Hesch, R.D.; Knippers, R. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer research 2001, 61, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fleischhacker, M.; Schmidt, B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer--a survey. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2007, 1775, 181–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitzer, E.; Ulz, P.; Geigl, J.B. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer. Clinical chemistry 2015, 61, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredno, J.; Lipson, J.; Venn, O.; Aravanis, A.M.; Jamshidi, A. Clinical correlates of circulating cell-free DNA tumor fraction. PloS one 2021, 16, e0256436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlquist, D.A. Universal cancer screening: revolutionary, rational, and realizable. NPJ Precis Oncol 2018, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tumor type1 | #Tumor samples2 | #Normal samples2 | Threshold3 | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLCA | 201 | 20 | 0.93 | 90.5% | 95.0% | 0.967 |

| BRCA | 676 | 96 | 0.90 | 90.5% | 95.8% | 0.979 |

| COAD | 274 | 38 | 0.84 | 96.7% | 100% | 0.992 |

| HNSC | 426 | 50 | 0.80 | 98.6% | 98.0% | 0.996 |

| KIRC | 296 | 160 | 0.65 | 82.4% | 95.6% | 0.931 |

| KIRP | 156 | 45 | 0.70 | 73.7% | 84.4% | 0.859 |

| LIHC | 151 | 50 | 0.43 | 92.1% | 98.0% | 0.950 |

| LUAD | 437 | 32 | 0.98 | 97.3% | 100% | 0.999 |

| LUSC | 359 | 42 | 0.64 | 99.2% | 100% | 0.996 |

| PAAD | 65 | 9 | 0.58 | 98.5% | 100% | 0.991 |

| PRAD | 248 | 49 | 0.82 | 90.3% | 91.8% | 0.941 |

| READ | 96 | 7 | 0.50 | 100% | 100% | 1.000 |

| STAD | 260 | 2 | 0.50 | 100% | 100% | 1.000 |

| UCEC | 405 | 46 | 0.79 | 99.0% | 100% | 0.997 |

| Tumor type1 | Dataset | #Tumor samples | #Normal samples | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA | GSE37754, GSE66695, GSE69914 | 449 | 149 | 79.5% | 94.0% |

| COAD | GSE53051 | 35 | 18 | 94.3% | 83.3% |

| LUAD | GSE53051 | 9 | 11 | 100% | 73% |

| PRAD | GSE112047 | 31 | 16 | 90.3% | 100.0% |

| Tumor type1 | Dataset | # Tumor samples | #Normal samples | Sensitivity2 | Specificity2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUAD | [30,31] | 9 | 4 | 100% | 100% |

| LIHC | [31,32] | 30 | 36 | 37.3% | 83.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).