Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

28 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

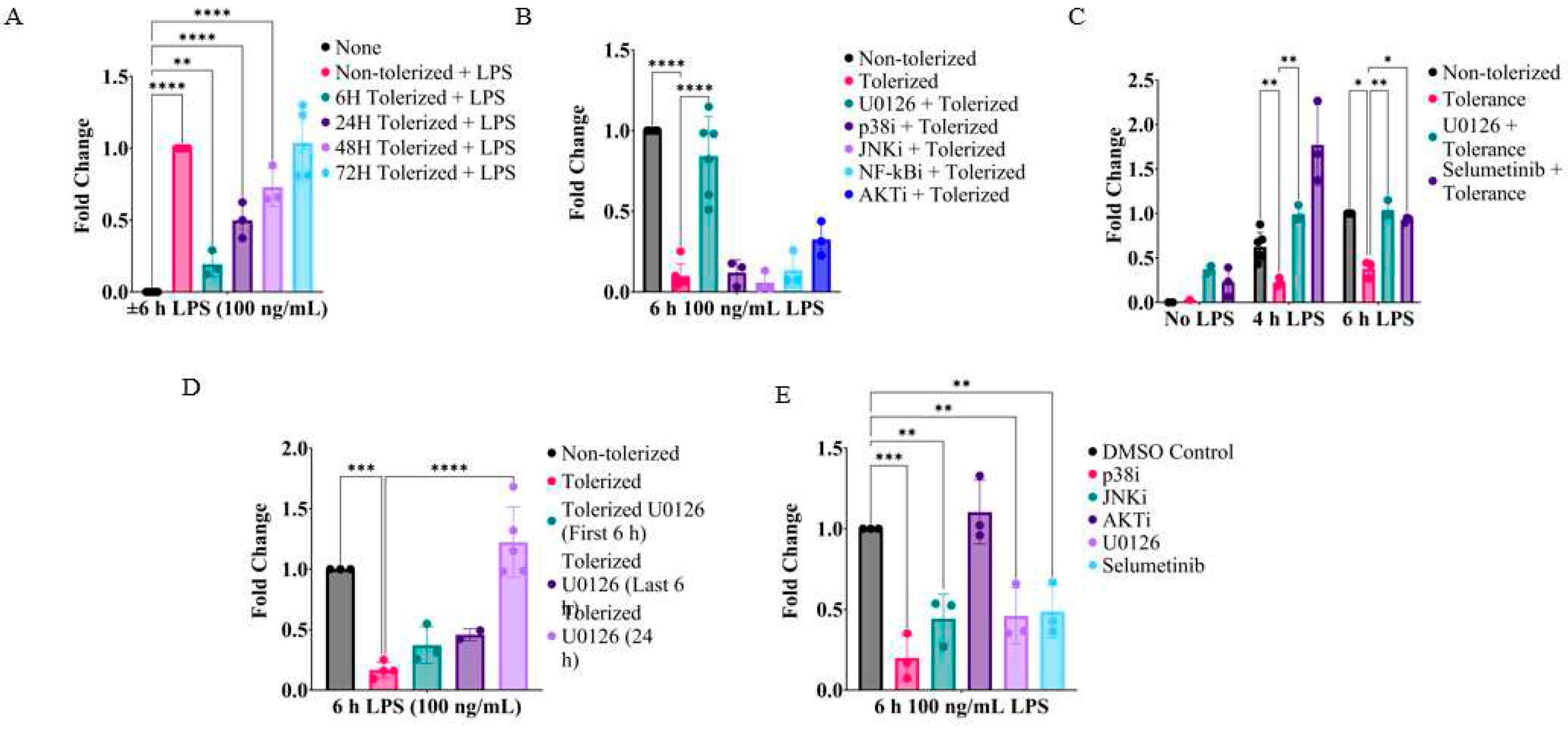

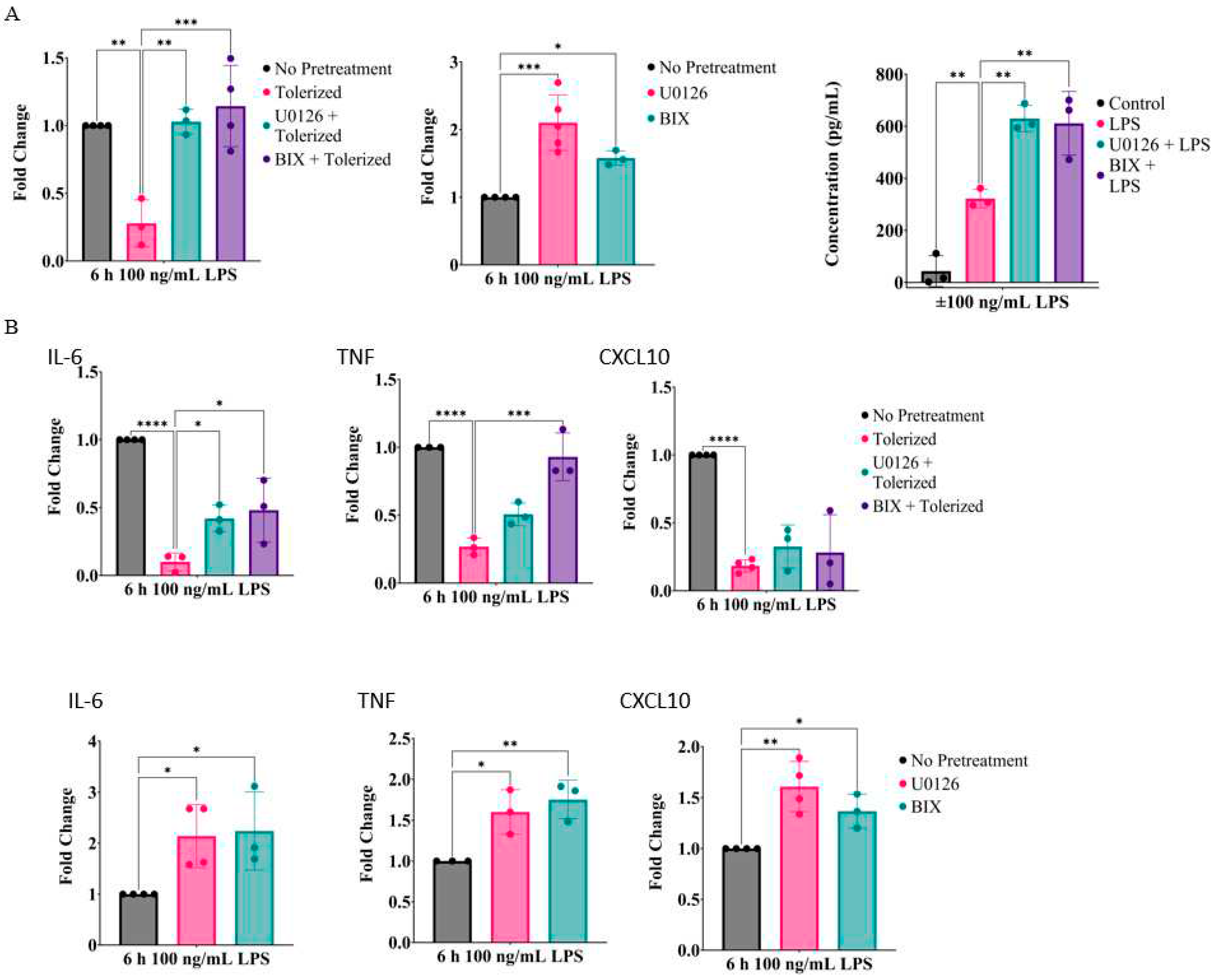

2.1. Inhibition of MEK1/2 enhances IL-1β expression in LPS-tolerized RAW264.7 macrophages

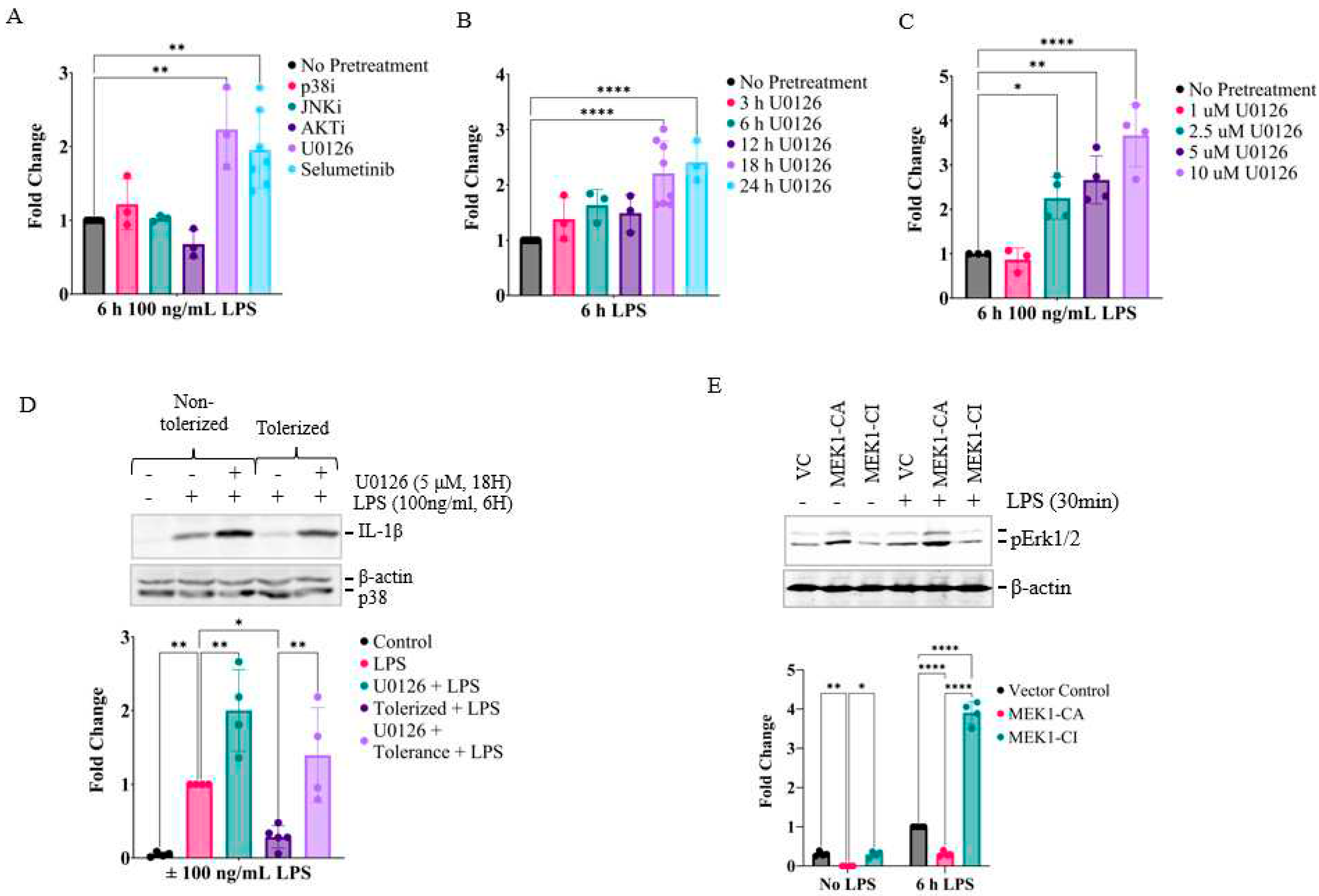

2.2. Prolonged inhibition of the MEK1/2-ERKs signaling axis primes RAW26.47 cells to LPS-induced IL-1β expression

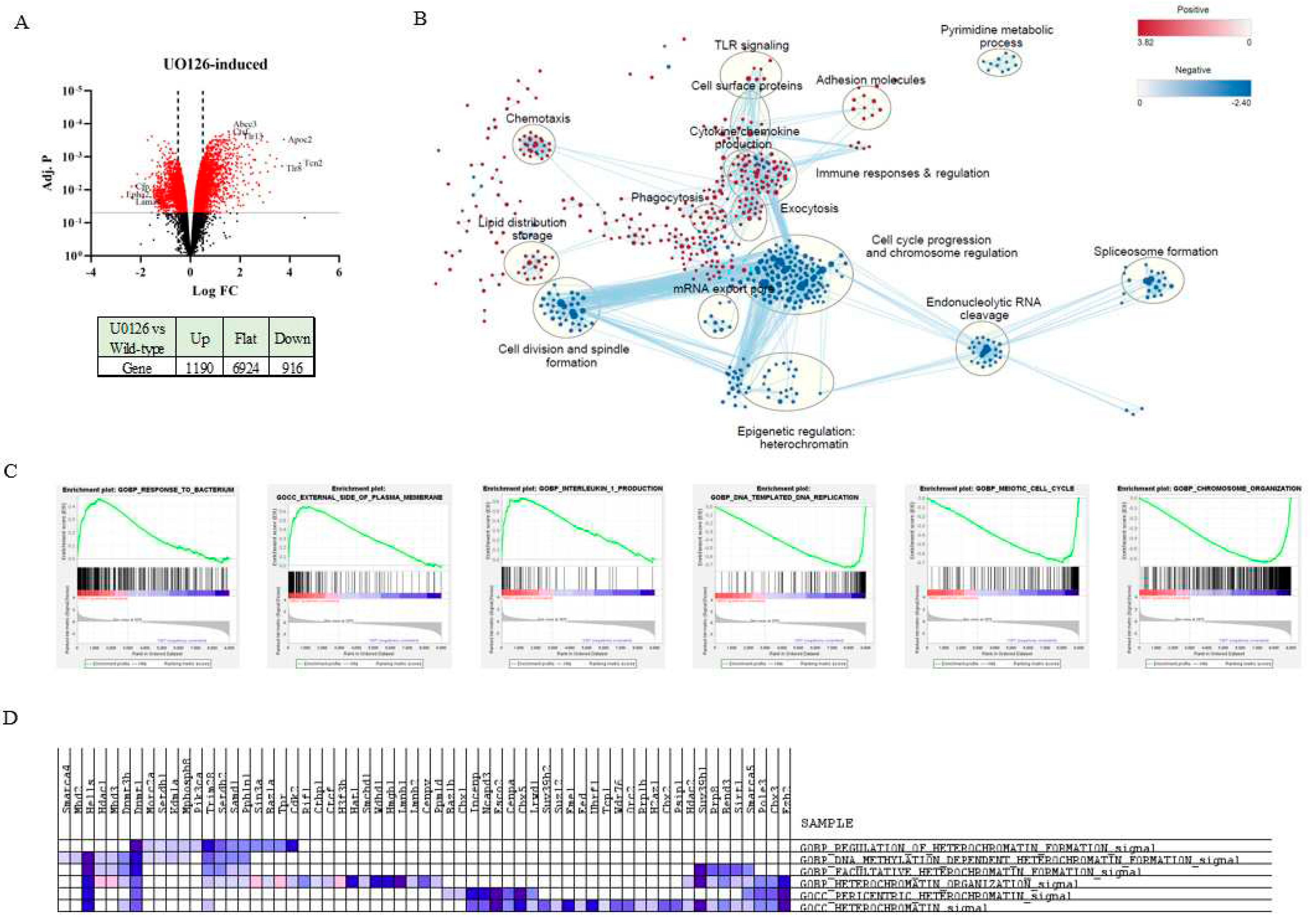

2.3. Prolonged inhibition of MEK1/2 enhances the expression of genes involved in the immune response and cytokine production but suppresses genes involved in cell cycle progression and heterochromatin formation

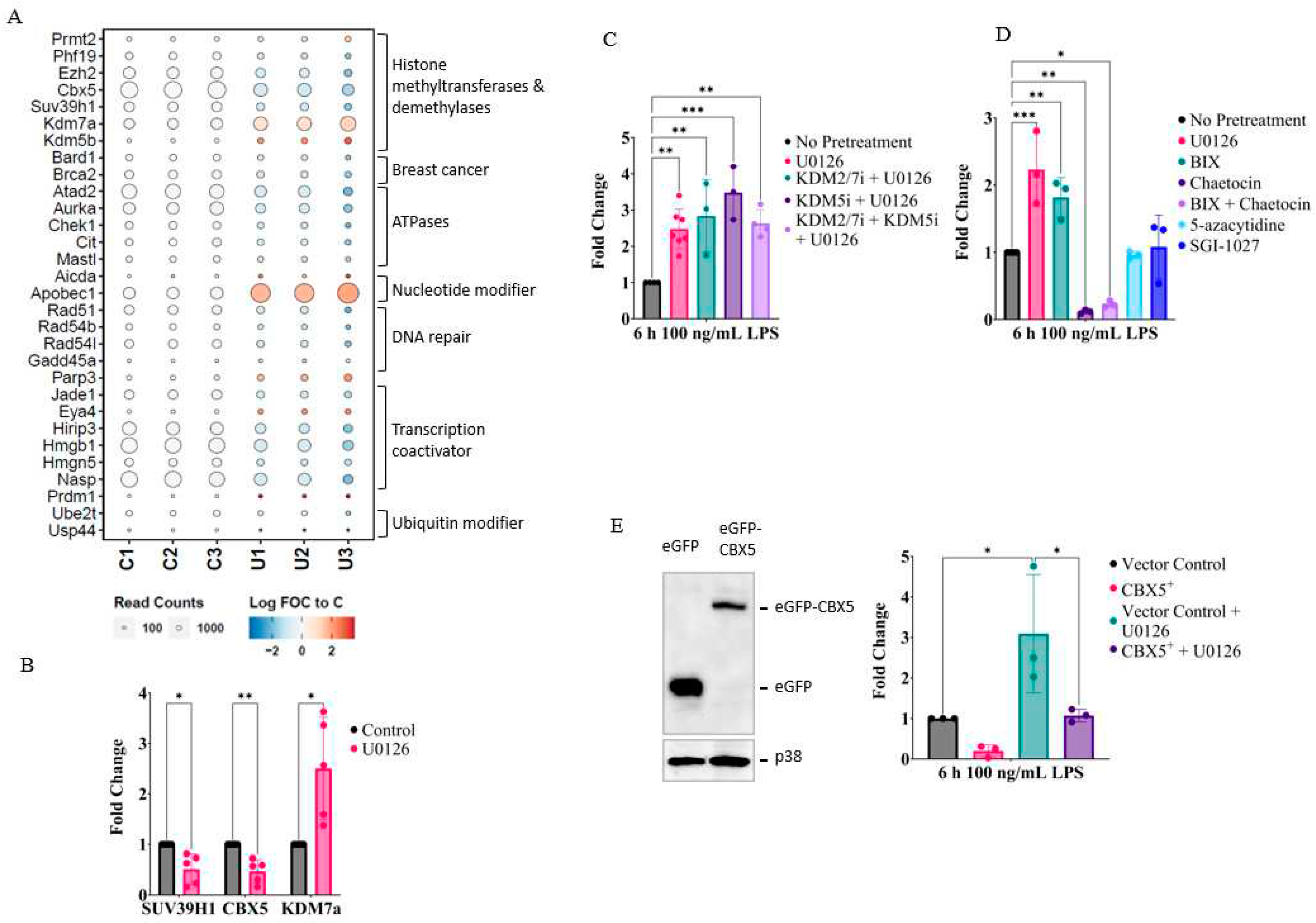

2.4. MEK1/2 inhibition regulates the expression of genes that promote histone H3K9 demethylation

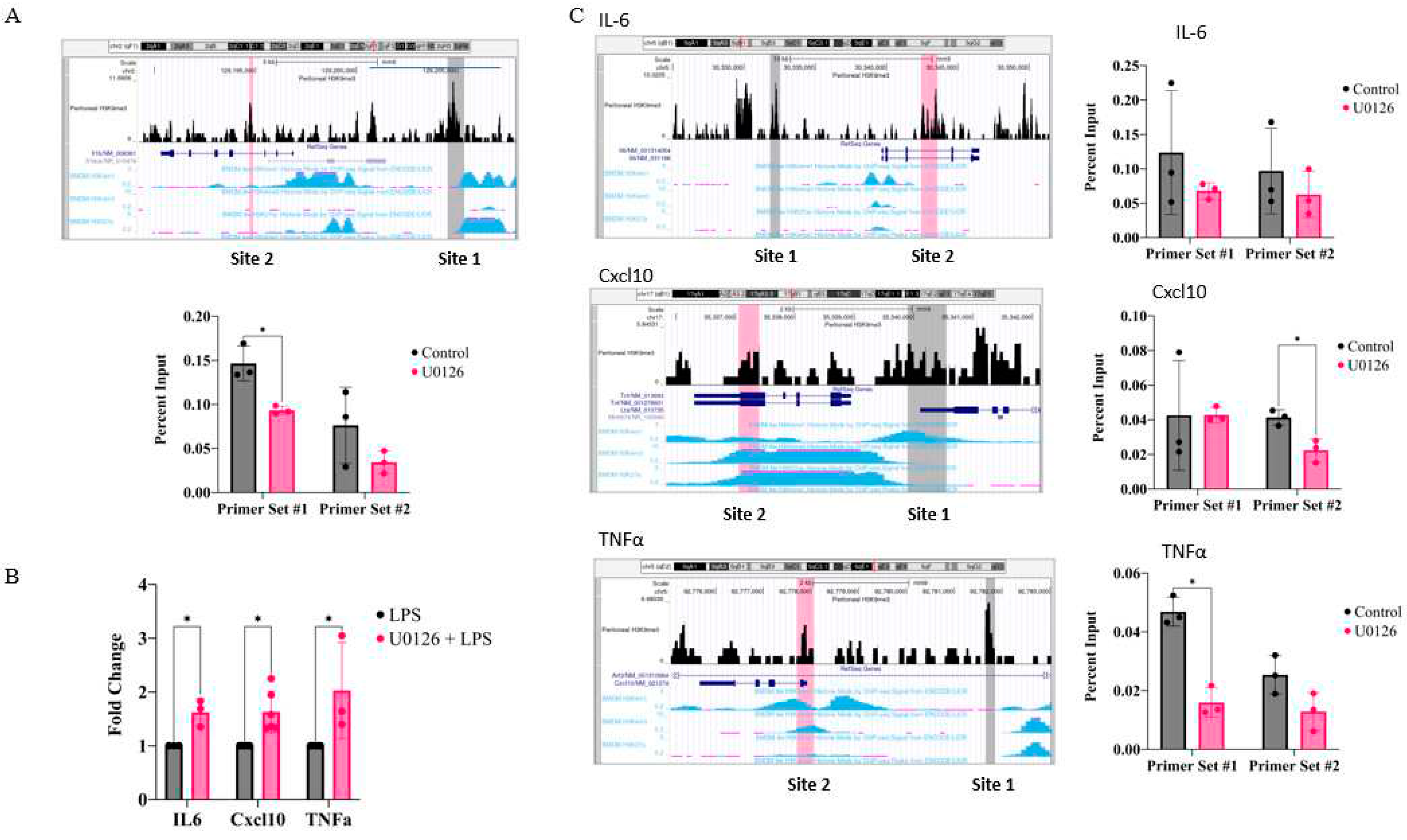

2.5. Inhibition of MEK1/2 decreases H3K9 trimethylation in the genomic region of the IL-1β, CXCL10, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α

2.6. Inhibition of the MEK1/2-ERK signaling axis primes IL-1β and other inflammatory cytokines in primary bone marrow-derived macrophages

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bleriot, C.; Chakarov, S.; Ginhoux, F. Determinants of resident tissue macrophage identity and function. Immunity 2020, 52, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stothers, C.L.; Burelbach, K.R.; Owen, A.M.; Patil, N.K.; McBride, M.A.; Bohannon, J.K.; Luan, L.; Hernandez, A.; Patil, T.K.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Beta-glucan induces distinct and protective innate immune memory in differentiated macrophages. J Immunol 2021, 207, 2785–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novakovic, B.; Habibi, E.; Wang, S.Y.; Arts, R.J.W.; Davar, R.; Megchelenbrink, W.; Kim, B.; Kuznetsova, T.; Kox, M.; Zwaag, J.; et al. Beta-glucan reverses the epigenetic state of lps-induced immunological tolerance. Cell 2016, 167, 1354–1368.e1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, S.H.; Evans, G.F.; Snyder, Y.M.; Roeder, W.D. Endotoxin-macrophage interaction: Post-translational regulation of tumor necrosis factor expression. J Immunol 1989, 143, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, F.; Akashi, S.; Sakao, Y.; Sato, S.; Kawai, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakanishi, K.; Kimoto, M.; Miyake, K.; Takeda, K.; et al. Cutting edge: Endotoxin tolerance in mouse peritoneal macrophages correlates with down-regulation of surface toll-like receptor 4 expression. J Immunol 2000, 164, 3476–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, D.L.; Turer, E.E.; Lee, E.G.; Ahmad, R.C.; Wheeler, M.T.; Tsui, C.; Hurley, P.; Chien, M.; Chai, S.; Hitotsumatsu, O.; et al. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme a20 is required for termination of toll-like receptor responses. Nat Immunol 2004, 5, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Hernandez, L.D.; Galan, J.E.; Janeway, C.A., Jr.; Medzhitov, R.; Flavell, R.A. Irak-m is a negative regulator of toll-like receptor signaling. Cell 2002, 110, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, R.J.; Ruan, Q.; Palmer, S.; Hilliard, B.; Chen, Y.H. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor signaling by nf-kappab p50 ubiquitination blockade. Science 2007, 317, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, J.J.; Ghosh, S. Molecular mechanisms of innate memory and tolerance to lps. J Leukoc Biol 2017, 101, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mages, J.; Dietrich, H.; Lang, R. A genome-wide analysis of lps tolerance in macrophages. Immunobiology 2007, 212, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.L.; Hargreaves, D.C.; Medzhitov, R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by tlr-induced chromatin modifications. Nature 2007, 447, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, A. Innate immune memory in macrophages. Newborn (Clarksville) 2023, 2, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Alvarez, B.; Baragano Raneros, A.; Ortega, F.; Lopez-Larrea, C. Epigenetic modulation of the immune function: A potential target for tolerance. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarmasz, J.S.; Stirton, H.; Davie, J.R.; Del Bigio, M.R. DNA methylation and histone post-translational modification stability in post-mortem brain tissue. Clin Epigenetics 2019, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Epigenetic regulation of macrophages: From homeostasis maintenance to host defense. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gazzar, M.; Yoza, B.K.; Hu, J.Y.; Cousart, S.L.; McCall, C.E. Epigenetic silencing of tumor necrosis factor alpha during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 26857–26864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gazzar, M.; Yoza, B.K.; Chen, X.; Hu, J.; Hawkins, G.A.; McCall, C.E. G9a and hp1 couple histone and DNA methylation to tnfalpha transcription silencing during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 32198–32208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.; Li, L.; McCall, C.E.; Yoza, B.K. Endotoxin tolerance disrupts chromatin remodeling and nf-kappab transactivation at the il-1beta promoter. J Immunol 2005, 175, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Maekawa, T.; Zhu, Y.; Renard-Guillet, C.; Chatton, B.; Inoue, K.; Uchiyama, T.; Ishibashi, K.; Yamada, T.; Ohno, N.; et al. The transcription factor atf7 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced epigenetic changes in macrophages involved in innate immunological memory. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poltorak, A.; He, X.; Smirnova, I.; Liu, M.Y.; Van Huffel, C.; Du, X.; Birdwell, D.; Alejos, E.; Silva, M.; Galanos, C.; et al. Defective lps signaling in c3h/hej and c57bl/10sccr mice: Mutations in tlr4 gene. Science 1998, 282, 2085–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoebe, K.; Du, X.; Georgel, P.; Janssen, E.; Tabeta, K.; Kim, S.O.; Goode, J.; Lin, P.; Mann, N.; Mudd, S.; et al. Identification of lps2 as a key transducer of myd88-independent tir signalling. Nature 2003, 424, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akira, S. Toll-like receptors: Lessons from knockout mice. Biochem Soc Trans 2000, 28, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, A.P.; Koblansky, A.A.; Ghosh, S. Recognition and signaling by toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2006, 22, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troutman, T.D.; Hu, W.; Fulenchek, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Kurosaki, T.; Bazan, J.F.; Pasare, C. Role for b-cell adapter for pi3k (bcap) as a signaling adapter linking toll-like receptors (tlrs) to serine/threonine kinases pi3k/akt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshet, Y.; Seger, R. The map kinase signaling cascades: A system of hundreds of components regulates a diverse array of physiological functions. Methods Mol Biol 2010, 661, 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, K.A.; Kagan, J.C. Toll-like receptors and the control of immunity. Cell 2020, 180, 1044–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R.; Horng, T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol 2009, 9, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostareck, D.H.; Ostareck-Lederer, A. Rna-binding proteins in the control of lps-induced macrophage response. Front Genet 2019, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strniskova, M.; Barancik, M.; Ravingerova, T. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and their role in regulation of cellular processes. Gen Physiol Biophys 2002, 21, 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Vergadi, E.; Ieronymaki, E.; Lyroni, K.; Vaporidi, K.; Tsatsanis, C. Akt signaling pathway in macrophage activation and m1/m2 polarization. J Immunol 2017, 198, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimand, J.; Isserlin, R.; Voisin, V.; Kucera, M.; Tannus-Lopes, C.; Rostamianfar, A.; Wadi, L.; Meyer, M.; Wong, J.; Xu, C.; et al. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:Profiler, gsea, cytoscape and enrichmentmap. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 482–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Johnson, L.M.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Patel, D.J. DNA methylation pathways and their crosstalk with histone methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligresti, G.; Caporarello, N.; Meridew, J.A.; Jones, D.L.; Tan, Q.; Choi, K.M.; Haak, A.J.; Aravamudhan, A.; Roden, A.C.; Prakash, Y.S.; et al. Cbx5/g9a/h3k9me-mediated gene repression is essential to fibroblast activation during lung fibrosis. JCI Insight 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijnen, A.J.; Bagheri, L.; Badreldin, A.A.; Larson, A.N.; Dudakovic, A.; Thaler, R.; Paradise, C.R.; Wu, Z. Biological functions of chromobox (cbx) proteins in stem cell self-renewal, lineage-commitment, cancer and development. Bone 2021, 143, 115659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissenberg, J.C.; Elgin, S.C. Hp1a: A structural chromosomal protein regulating transcription. Trends Genet 2014, 30, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, B.S. Pretreatment of low-dose and super-low-dose lps on the production of in vitro lps-induced inflammatory mediators. Toxicol Res 2018, 34, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Maitra, U.; Morris, M.; Li, L. Molecular mechanism responsible for the priming of macrophage activation. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 3897–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, U.; Deng, H.; Glaros, T.; Baker, B.; Capelluto, D.G.; Li, Z.; Li, L. Molecular mechanisms responsible for the selective and low-grade induction of proinflammatory mediators in murine macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 2012, 189, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.; Ifrim, D.C.; Saeed, S.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; de Jong, D.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; et al. Bacille calmette-guerin induces nod2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 17537–17542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintin, J.; Saeed, S.; Martens, J.H.A.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Ifrim, D.C.; Logie, C.; Jacobs, L.; Jansen, T.; Kullberg, B.J.; Wijmenga, C.; et al. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Quintin, J.; Kerstens, H.H.; Rao, N.A.; Aghajanirefah, A.; Matarese, F.; Cheng, S.C.; Ratter, J.; Berentsen, K.; van der Ent, M.A.; et al. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science 2014, 345, 1251086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkering, S.; Quintin, J.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 34, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findeisen, H.M.; Voges, V.C.; Braun, L.C.; Sonnenberg, J.; Schwarz, D.; Korner, H.; Reinecke, H.; Sohrabi, Y. Lxralpha regulates oxldl-induced trained immunity in macrophages. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Boonmee, A.; Benjaskulluecha, S.; Kueanjinda, P.; Wongprom, B.; Pattarakankul, T.; Palaga, T. The chemotherapeutic drug carboplatin affects macrophage responses to lps and lps tolerance via epigenetic modifications. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Dominguez-Andres, J.; Barreiro, L.B.; Chavakis, T.; Divangahi, M.; Fuchs, E.; Joosten, L.A.B.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; Mhlanga, M.M.; Mulder, W.J.M.; et al. Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, H.G.; Joosten, I.; Allebes, W.A.; van der Meer, A.; Hilbrands, L.B.; Baas, M.; Spierings, E.; Hack, C.E.; van Reekum, F.; van Zuilen, A.D.; et al. The procare consortium: Toward an improved allocation strategy for kidney allografts. Transpl Immunol 2014, 31, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padeken, J.; Methot, S.P.; Gasser, S.M. Establishment of h3k9-methylated heterochromatin and its functions in tissue differentiation and maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.; Horowitz, S.; Trievel, R.C. Structure and function of histone h3 lysine 9 methyltransferases and demethylases. Chembiochem 2011, 12, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, A.S.; Davis, F.M.; denDekker, A.; Joshi, A.D.; Schaller, M.A.; Bermick, J.; Xing, X.; Burant, C.F.; Obi, A.T.; Nysz, D.; et al. The histone methyltransferase setdb2 modulates macrophage phenotype and uric acid production in diabetic wound repair. Immunity 2019, 51, 258–271.e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachiya, R.; Shiihashi, T.; Shirakawa, I.; Iwasaki, Y.; Matsumura, Y.; Oishi, Y.; Nakayama, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Manabe, I.; Ochi, K.; et al. The h3k9 methyltransferase setdb1 regulates tlr4-mediated inflammatory responses in macrophages. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 28845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausendschon, M.; Dehne, N.; Brune, B. Hypoxia causes epigenetic gene regulation in macrophages by attenuating jumonji histone demethylase activity. Cytokine 2011, 53, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccani, S.; Natoli, G. Dynamic changes in histone h3 lys 9 methylation occurring at tightly regulated inducible inflammatory genes. Genes Dev 2002, 16, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, J.; Bai, J.; Pu, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Ruan, B. Suv39h1 protects from myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetic rats. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014, 33, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.T.; Wu, S.M.; Ho, S.C.; Chuang, H.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Chan, Y.F.; Kuo, L.W.; Feng, P.H.; Liu, W.T.; Chen, K.Y.; et al. Suv39h1 reduction is implicated in abnormal inflammation in copd. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 46667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.F.; Zhang, R.; Li, T.T.; Chen, M.Y.; Li, L.X.; Lu, J.X.; Jia, W.P. High glucose increases the expression of inflammatory cytokine genes in macrophages through h3k9 methyltransferase mechanism. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2016, 36, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, W.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Lu, J.; Chen, H. Chaetocin attenuates gout in mice through inhibiting hif-1alpha and nlrp3 inflammasome-dependent il-1beta secretion in macrophages. Arch Biochem Biophys 2019, 670, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaib, H.; Nebbioso, A.; Prebet, T.; Castellano, R.; Garbit, S.; Restouin, A.; Vey, N.; Altucci, L.; Collette, Y. Anti-leukemia activity of chaetocin via death receptor-dependent apoptosis and dual modulation of the histone methyl-transferase suv39h1. Leukemia 2012, 26, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, Y.; Ishitani, T.; Nakayama, K.I. Kdm7 is a dual demethylase for histone h3 lys 9 and lys 27 and functions in brain development. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.D.; Li, J.; Wong, J. Relationship between histone h3 lysine 9 methylation, transcription repression, and heterochromatin protein 1 recruitment. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25, 2525–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covian, C.; Fernandez-Fierro, A.; Retamal-Diaz, A.; Diaz, F.E.; Vasquez, A.E.; Lay, M.K.; Riedel, C.A.; Gonzalez, P.A.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Bcg-induced cross-protection and development of trained immunity: Implication for vaccine design. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, S.T.; Groh, L.; Thiem, K.; Bekkering, S.; Li, Y.; Matzaraki, V.; van der Heijden, C.; van Puffelen, J.H.; Lachmandas, E.; Jansen, T.; et al. Rewiring of glucose metabolism defines trained immunity induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Mol Med (Berl) 2020, 98, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, Y.; Lagache, S.M.M.; Schnack, L.; Godfrey, R.; Kahles, F.; Bruemmer, D.; Waltenberger, J.; Findeisen, H.M. Mtor-dependent oxidative stress regulates oxldl-induced trained innate immunity in human monocytes. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.J.W.; Carvalho, A.; La Rocca, C.; Palma, C.; Rodrigues, F.; Silvestre, R.; Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Lachmandas, E.; Goncalves, L.G.; Belinha, A.; et al. Immunometabolic pathways in bcg-induced trained immunity. Cell Rep 2016, 17, 2562–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.C.; Quintin, J.; Cramer, R.A.; Shepardson, K.M.; Saeed, S.; Kumar, V.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Martens, J.H.; Rao, N.A.; Aghajanirefah, A.; et al. Mtor- and hif-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science 2014, 345, 1250684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanucchi, S.; Dominguez-Andres, J.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G.; Mhlanga, M.M. The intersection of epigenetics and metabolism in trained immunity. Immunity 2021, 54, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubrey, J.A.; Steelman, L.S.; Chappell, W.H.; Abrams, S.L.; Franklin, R.A.; Montalto, G.; Cervello, M.; Libra, M.; Candido, S.; Malaponte, G.; et al. Ras/raf/mek/erk and pi3k/pten/akt/mtor cascade inhibitors: How mutations can result in therapy resistance and how to overcome resistance. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 1068–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.D.; Ng, D.; Pelech, S.L.; Kim, S.O. Critical role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling pathway in recovery from anthrax lethal toxin-induced cell cycle arrest and mek cleavage in macrophages. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 36230–36239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.H.; Sharrocks, A.D.; Whitmarsh, A.J. Map kinase signalling cascades and transcriptional regulation. Gene 2013, 513, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Pelaez, M.; Fumagalli, S.; Sanz, C.; Herrero, C.; Guerra, S.; Fernandez, M.; Alemany, S. Cot/tpl2-mkk1/2-erk1/2 controls mtorc1-mediated mrna translation in toll-like receptor-activated macrophages. Mol Biol Cell 2012, 23, 2982–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherle, P.A.; Jones, E.A.; Favata, M.F.; Daulerio, A.J.; Covington, M.B.; Nurnberg, S.A.; Magolda, R.L.; Trzaskos, J.M. Inhibition of map kinase kinase prevents cytokine and prostaglandin e2 production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated monocytes. J Immunol 1998, 161, 5681–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.M.; Navarro-Puche, A.; Casar, B.; Crespo, P.; Andres, V. Fast regulation of ap-1 activity through interaction of lamin a/c, erk1/2, and c-fos at the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol 2008, 183, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, G.P.; Ballare, C.; Nacht, A.S.; Clausell, J.; Subtil-Rodriguez, A.; Quiles, I.; Jordan, A.; Beato, M. Induction of progesterone target genes requires activation of erk and msk kinases and phosphorylation of histone h3. Mol Cell 2006, 24, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobic, B.; Perez-Cadahia, B.; Yu, J.; Kung, S.K.; Davie, J.R. Promoter chromatin remodeling of immediate-early genes is mediated through h3 phosphorylation at either serine 28 or 10 by the msk1 multi-protein complex. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, 3196–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, S.; Matsuura, M.; Hirai, Y. Regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-12 production by activation of repressor element ga-12 through hyperactivation of the erk pathway. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2006, 13, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Xie, Z.; Onishi, A.; Yu, X.; Jiang, L.; Lin, J.; Rho, H.S.; Woodard, C.; Wang, H.; Jeong, J.S.; et al. Profiling the human protein-DNA interactome reveals erk2 as a transcriptional repressor of interferon signaling. Cell 2009, 139, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Iorio, C.; Yan, K.; Yang, H.; Takeshita, S.; Kang, S.; Neel, B.G.; Yang, W. A erk/rsk-mediated negative feedback loop regulates m-csf-evoked pi3k/akt activation in macrophages. FASEB J 2018, 32, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Goncalves, R.; Mosser, D.M. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol 2008, 14, 14 11 11–14 11 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, M.; Chari, S.; Dunn, M.J.; Sorokin, A. Biphasic activation of p21ras by endothelin-1 sequentially activates the erk cascade and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. EMBO J 1997, 16, 6439–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.O.; Sheikh, H.I.; Ha, S.D.; Martins, A.; Reid, G. G-csf-mediated inhibition of jnk is a key mechanism for lactobacillus rhamnosus-induced suppression of tnf production in macrophages. Cell Microbiol 2006, 8, 1958–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.D.; Lewin, N.; Li, S.S.C.; Kim, S.O. Hdac8 activates akt through upregulating plcb1 and suppressing desc1 expression in mek1/2 inhibition-resistant cells. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. Featurecounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for rna-seq data with deseq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for rna-seq read counts. Genome Biol 2014, 15, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otasek, D.; Morris, J.H.; Boucas, J.; Pico, A.R.; Demchak, B. Cytoscape automation: Empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Brouwer, C. Pathview: An r/bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1830–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.D.; Cho, W.; DeKoter, R.P.; Kim, S.O. The transcription factor pu.1 mediates enhancer-promoter looping that is required for il-1beta erna and mrna transcription in mouse melanoma and macrophage cell lines. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 17487–17500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).