Submitted:

22 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

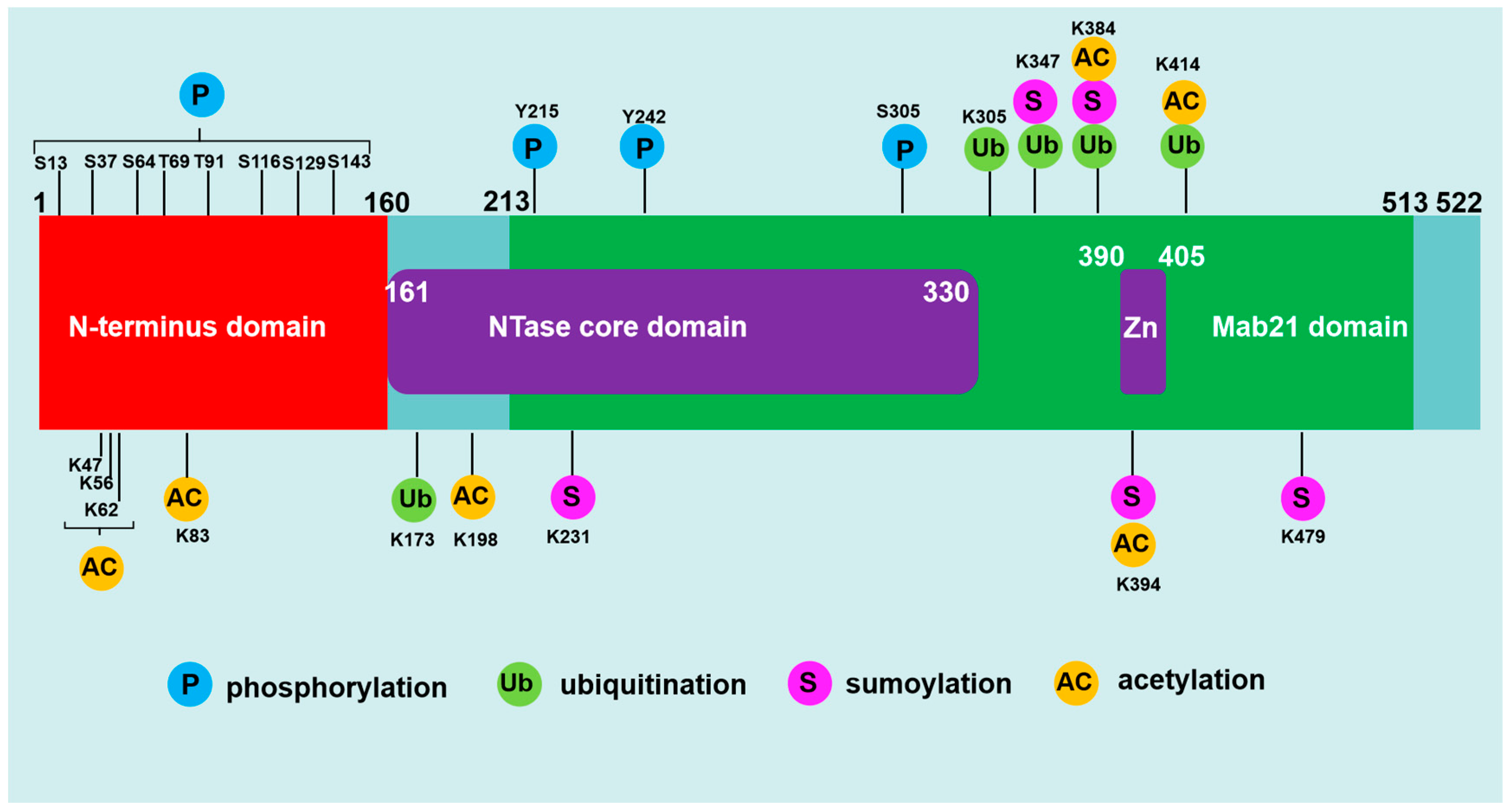

2. Structural Domains and Modification Sites of cGAS

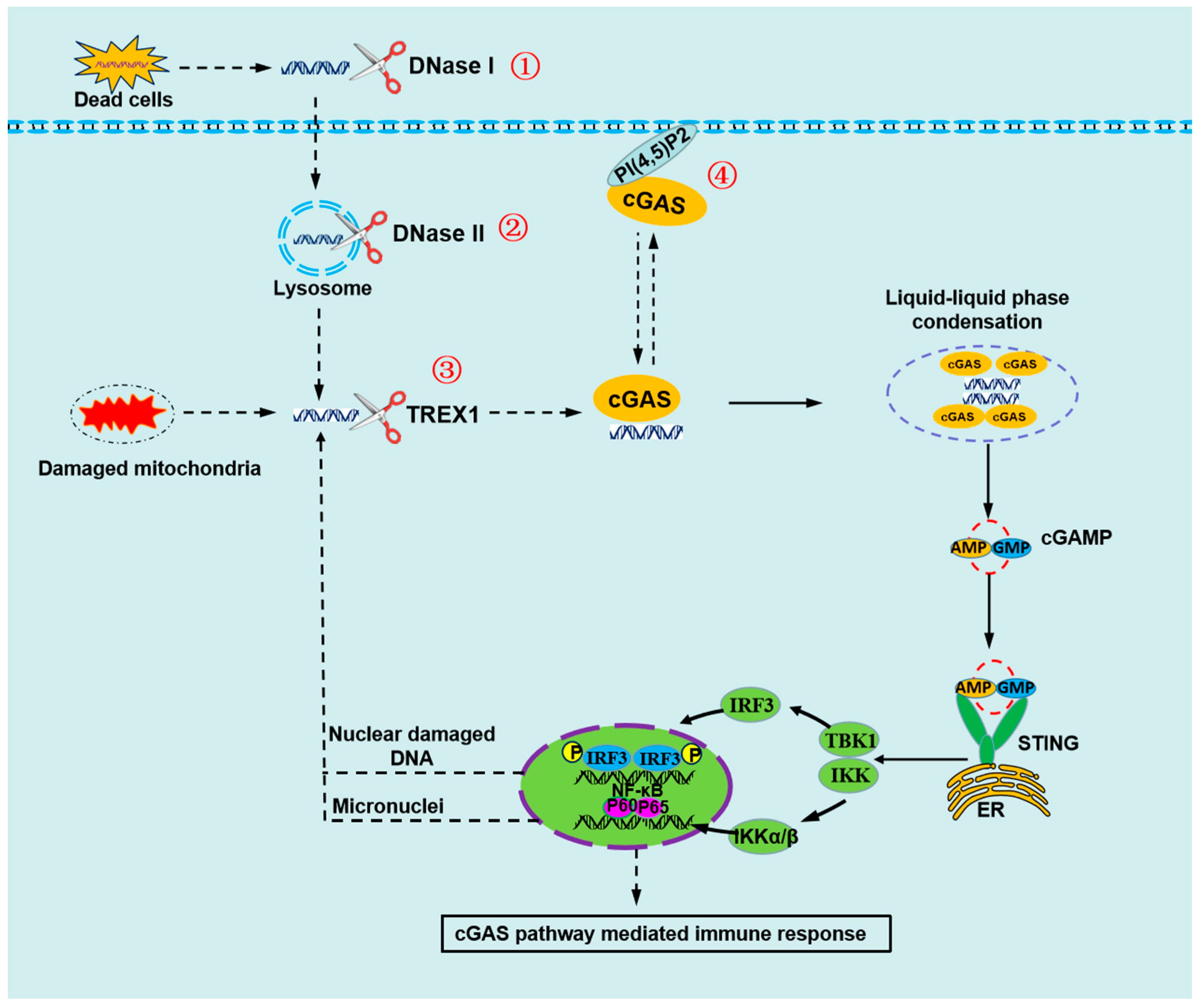

3. How is the cGAS Activated

3.1. DNA-Induced Conformational Changes in cGAS Lead to Its Activation

3.2. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation Can Enhance the Activation of cGAS

3.3. Divalent Cations Substantially Promote the Activity of cGAS

4. How Does cGAS Avoid to Sense Self-DNA under Normal Conditions?

4.1. Self-DNA Is Cleared by the DNases

4.2. Plasma Membrane Localization of cGAS Prevents Recognition of self-DNA

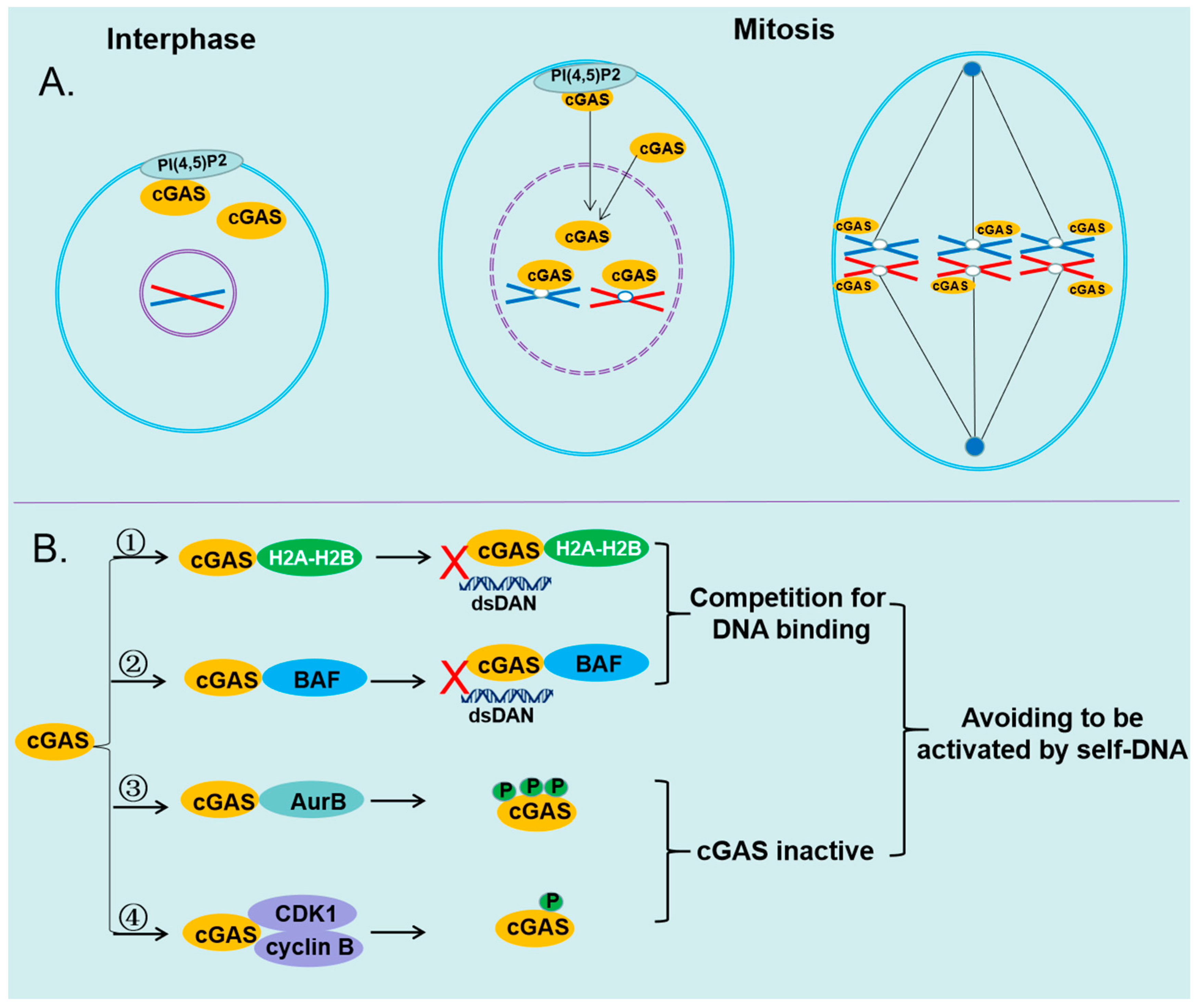

4.3. Binding to Histones Prevents cGAS from Sensing Self-DNA during Mitosis

4.4. Binding to Barrier-to-Autointegration Factor 1 Restricts cGAS to Sense self-DNA during Mitosis

4.5. The Activity of cGAS Is Suppressed via Phosphorylation during Mitosis

5. Consequences of Self-DNA Induced cGAS Activation

5.1. Activation of cGAS by Self-DNA Can Cause Autoimmune Diseases

5.2. Activation of cGAS by Self-DNA Is a Double-Edged Sword in Cancer

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Ablasser, A.; Chen, Z.J.J. cGAS in action: Expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science 2019, 363, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civril, F.; Deimling, T.; Mann, C.C.D.; Ablasser, A.; Moldt, M.; Witte, G.; Hornung, V.; Hopfner, K.P. Structural mechanism of cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS. Nature 2013, 498, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.L.; Liu, A.J.; Xia, N.W.; Chen, N.H.; Meurens, F.; Zhu, J.Z. How the Innate Immune DNA Sensing cGAS-STING Pathway Is Involved in Apoptosis. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.X.; Villagomes, D.; Zhao, H.C.; Zhu, M. cGAS in nucleus: The link between immune response and DNA damage repair. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R.B. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Immunology 2020, 20, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata-Garrido, J.; Frizzi, L.; Nguyen, T.; He, X.Y.; Chang-Marchand, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Reisacher, C.; Casafont, I.; Arbibe, L. HP1 gamma Prevents Activation of the cGAS/STING Pathway by Preserving Nuclear Envelope and Genomic Integrity in Colon Adenocarcinoma Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadio, R.; Piperno, G.M.; Benvenuti, F. Self-DNA Sensing by cGAS-STING and TLR9 in Autoimmunity: Is the Cytoskeleton in Control? Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopfner, K.P.; Hornung, V. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS-STING signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2020, 21, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttinger, S.; Laurell, E.; Kutay, U. Orchestrating nuclear envelope disassembly and reassembly during mitosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2009, 10, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, R.E.; Leitch, A.; Jackson, A.P. Nucleic acid-mediated inflammatory diseases. Bioessays 2008, 30, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Liu, P.D. Cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS: regulation, function, and human diseases. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Joshi, J.C.; Mehta, D. Regulation of cGAS Activity and Downstream Signaling. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.L.; Liu, F. Nuclear cGAS: sequestration and beyond. Protein & cell 2022, 13, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.M.; Wu, F.H.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Siedow, J.N.; Zhang, W.G.; Pei, Z.M. Molecular evolutionary and structural analysis of the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS and STING. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 8243–8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.K.; Li, S.T. Role of Post-Translational Modifications of cGAS in Innate Immunity. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Huang, T.Z.; Chen, Z.J.J. Phosphorylation and Chromatin Tethering Prevent cGAS activation During Mitosis. Journal of immunology 2021, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Yu, H.S.; Zheng, X.; Peng, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.H.; Qu, B.; Shen, N. , et al. SENP7 Potentiates cGAS Activation by Relieving SUMO-Mediated Inhibition of Cytosolic DNA Sensing. Plos Pathogens 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, L.Y.; Hong, Z.; Lv, Z.S.; Mao, Z.M.; Tang, Y.J.; Kong, X.F.; Li, S.L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, H. , et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF185 facilitates the cGAS-mediated innate immune response. Plos Pathogens 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.K.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.Y.; Lu, J.; Bao, S.W.; Shen, Q.; Wang, X.C.; Liu, Y.W.; Zhang, W. E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: The Operators of the Ubiquitin Code That Regulates the RLR and cGAS-STING Pathways. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.M.; Yang, Q.; Xie, X.Q.; Liao, C.Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, T.T.; Yin, L.; Shu, H.B. Sumoylation Promotes the Stability of the DNA Sensor cGAS and the Adaptor STING to Regulate the Kinetics of Response to DNA Virus. Immunity 2016, 45, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Huang, Y.J.; He, X.H.; Zhao, M.; Wang, X.Z.; Liu, Z.S.; Xue, W.; Cai, H.; Zhan, X.Y.; Huang, S.Y. , et al. Acetylation Blocks cGAS Activity and Inhibits Self-DNA-Induced Autoimmunity. Cell 2019, 176, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.M.; Lin, H.; Yi, X.M.; Guo, W.; Hu, M.M.; Shu, H.B. KAT5 acetylates cGAS to promote innate immune response to DNA virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 21568–21575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, Q.M.; Volkman, H.E.; Gray, E.E.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Cambier, S.; Bera, A.K.; Sankaran, B.; Johnson, M.R.; Bick, M.J.; Kang, A.L. , et al. Computational design of constitutively active cGAS. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2023, 30, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzner, A.M.; Schlee, M.; Bartok, E. The many faces of cGAS: how cGAS activation is controlled in the cytosol, the nucleus, and during mitosis. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.D.C.; Hornung, V. Molecular mechanisms of nonself nucleic acid recognition by the innate immune system. European journal of immunology 2021, 51, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.W.; Bai, X.C.; Chen, Z.J.J. Structures and Mechanisms in the cGAS-STING Innate Immunity Pathway. Immunity 2020, 53, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Mo, J.L.; Zhu, T.; Zhuo, W.; Yi, Y.N.; Hu, S.; Yin, J.Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, H.H.; Liu, Z.Q. Comprehensive elaboration of the cGAS-STING signaling axis in cancer development and immunotherapy. Molecular cancer 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, C.G.; Dao, T.P.; Ujma, J.; Castaneda, C.; Beveridge, R. Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry Unveils Global Protein Conformations in Response to Conditions that Promote and Reverse Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 12541–12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; McAtee, C.K.; Su, X.L. Phase separation in immune signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology 2022, 22, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.J.; Chen, Z.J.J. DNA-induced liquid phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling. Science 2018, 361, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.M.; Shu, H.B. Innate Immune Response to Cytoplasmic DNA: Mechanisms and Diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 2020, 38, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Mohr, L.; Maciejowski, J.; Kranzusch, P.J. cGAS phase separation inhibits TREX1-mediated DNA degradation and enhances cytosolic DNA sensing. Molecular cell 2021, 81, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Shu, C.; Yi, G.H.; Chaton, C.T.; Shelton, C.L.; Diao, J.S.; Zuo, X.B.; Kao, C.C.; Herr, A.B.; Li, P.W. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is Activated by Double-Stranded DNA-Induced Oligomerization. Immunity 2013, 39, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Chen, Z.J. DNA-induced liquid phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling. Science 2018, 361, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitic, N.; Miraula, M.; Selleck, C.; Hadler, K.S.; Uribe, E.; Pedroso, M.M.; Schenk, G. Catalytic Mechanisms of Metallohydrolases Containing Two Metal Ions. Adv Protein Chem Str 2014, 97, 49–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, Z.X.; Wang, B.; Guan, Y.K.; Su, X.D.; Jiang, Z.F. Mn2+ Directly Activates cGAS and Structural Analysis Suggests Mn2+ Induces a Noncanonical Catalytic Synthesis of 2 ‘ 3 ‘-cGAMP. Cell Rep 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.S.; Yan, Z.Z.; Zhu, D.Y.; Xu, H.Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H.H.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, B.Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. CD-NTase family member MB21D2 promotes cGAS-mediated antiviral and antitumor immunity. Cell death and differentiation 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenberg, J.M.; Kamynina, M.; Sorokin, M.; Zolotovskaia, M.; Koroleva, E.; Kremenchutckaya, K.; Gudkov, A.; Buzdin, A.; Borisov, N. The Role of the Metabolism of Zinc and Manganese Ions in Human Cancerogenesis. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.G.; Guan, Y.K.; Lv, M.Z.; Zhang, R.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wei, X.M.; Du, X.X.; Yang, J.; Li, T.; Wan, Y. , et al. Manganese Increases the Sensitivity of the cGAS-STING Pathway for Double-Stranded DNA and Is Required for the Host Defense against DNA Viruses. Immunity 2018, 48, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.H.; Serrano, T.P.O.; Davis, J.; Prigge, A.D.; Ridge, K.M. The cGAS-STING pathway: The role of self-DNA sensing in inflammatory lung disease. Faseb Journal 2020, 34, 13156–13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, R.; Arai, T.; Kijima, M.; Sato, S.; Miura, S.; Yuasa, M.; Kitamura, D.; Mizuta, R. DNase, DNase I and caspase-activated DNase cooperate to degrade dead cells. Genes Cells 2016, 21, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anindya, R. Cytoplasmic DNA in cancer cells: Several pathways that potentially limit DNase2 and TREX1 activities. Bba-Mol Cell Res 2022, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, S.R.; Hemphill, W.O.; Hudson, T.; Perrino, F.W. TREX1-Apex predator of cytosolic DNA metabolism. DNA Repair 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, N.Y.; Wei, J.J.; Xu, S.; Du, H.K.; Huang, M.H.; Zhang, S.T.; Ye, W.W.; Sun, L.J.; Chen, Q. cGAS activation causes lupus-like autoimmune disorders in a TREX1 mutant mouse model. J Autoimmun 2019, 100, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.M.S.; Luciani, M.; Gatto, F.; Abou Alezz, M.; Beghe, C.; Della Volpe, L.; Migliara, A.; Valsoni, S.; Genua, M.; Dzieciatkowska, M. , et al. DNA damage contributes to neurotoxic inflammation in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome astrocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2022, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.W.; Ying, S.C.; Xu, X.; Wu, D. TREX1 cytosolic DNA degradation correlates with autoimmune disease and cancer immunity. Clin Exp Immunol 2023, 211, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.X.; Li, T.; Li, X.D.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.Z.; Wight-Carter, M.; Chen, Z.J. Activation of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase by self-DNA causes autoimmune diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 112, E5699–E5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, K.C.; Coronas-Serna, J.M.; Zhou, W.; Ernandes, M.J.; Cao, A.; Kranzusch, P.J.; Kagan, J.C. Phosphoinositide Interactions Position cGAS at the Plasma Membrane to Ensure Efficient Distinction between Self- and Viral DNA. Cell 2019, 176, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablasser, A.; Hur, S. Regulation of cGAS- and RLR-mediated immunity to nucleic acids. Nature immunology 2020, 21, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.K.; Song, K.; Hao, W.Z.; Li, J.; Wang, L.Y.; Li, S.T. Nuclear soluble cGAS senses double-stranded DNA virus infection. Communications biology 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischnewski, M.; Ablasser, A. Interplay of cGAS with chromatin. Trends Biochem Sci 2021, 46, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierhut, C.; Yamaguchi, N.; Paredes, M.; Luo, J.D.; Carroll, T.; Funabiki, H. The Cytoplasmic DNA Sensor cGAS Promotes Mitotic Cell Death. Cell 2019, 178, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.F.; Han, X.A.; Fan, X.Y.; Xu, R.M.; Zhang, X.Z. Structural basis for nucleosome-mediated inhibition of cGAS activity. Cell research 2020, 30, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guey, B.; Wischnewski, M.; Decout, A.; Makasheva, K.; Kaynak, M.; Sakar, M.S.; Fierz, B.; Ablasser, A. BAF restricts cGAS on nuclear DNA to prevent innate immune activation. Science 2020, 369, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamin, A.; Wiebe, M.S. Barrier to Autointegration Factor (BANF1): interwoven roles in nuclear structure, genome integrity, innate immunity, stress responses and progeria. Current opinion in cell biology 2015, 34, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.M.; Ronning, D.R.; Ghirlando, R.; Craigie, R.; Dyda, F. Structural basis for DNA bridging by barrier-to-autointegration factor. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005, 12, 935–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, G.; Ni, G.X.; Zhang, Z.G.; Li, Q.; Cano, P.; Dittmer, D.P.; Damania, B. Barrier-to-autointegration factor 1 promotes gammaherpesvirus reactivation from latency. Nature communications 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Hu, M.M.; Bian, L.J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Shu, H.B. Phosphorylation of cGAS by CDK1 impairs self-DNA sensing in mitosis. Cell Discov 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navegantes, K.C.; Gomes, R.D.; Pereira, P.A.T.; Czaikoski, P.G.; Azevedo, C.H.M.; Monteiro, M.C. Immune modulation of some autoimmune diseases: the critical role of macrophages and neutrophils in the innate and adaptive immunity. J Transl Med 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benmerzoug, S.; Ryffel, B.; Togbe, D.; Quesniaux, V.F.J. Self-DNA Sensing in Lung Inflammatory Diseases. Trends in immunology 2019, 40, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonduti, D.; Fazzi, E.; Badolato, R.; Orcesi, S. Novel and emerging treatments for Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immu 2020, 16, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokatayev, V.; Hasin, N.; Chon, H.; Cerritelli, S.M.; Sakhuja, K.; Ward, J.M.; Morris, H.D.; Yan, N.; Crouch, R.J. RNase H2 catalytic core Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome-related mutant invokes cGAS-STING innate immune-sensing pathway in mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2016, 213, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.E.; Treuting, P.M.; Woodward, J.J.; Stetson, D.B. Cutting Edge: cGAS Is Required for Lethal Autoimmune Disease in the Trex1-Deficient Mouse Model of Aicardi-Goutieres Syndrome. Journal of immunology 2015, 195, 1939–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, M.K. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: risks, mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Park, J.; Takamatsu, H.; Konaka, H.; Aoki, W.; Aburaya, S.; Ueda, M.; Nishide, M.; Koyama, S.; Hayama, Y. , et al. Apoptosis-derived membrane vesicles drive the cGAS-STING pathway and enhance type I IFN production in systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2018, 77, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.D.; Shang, M.J.; Han, Y.X.; Liu, J.Y.; Liu, J.W.; Kong, S.H.; Hou, J.Y.; Huang, B.Q.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y. EZH2-CCF-cGAS Axis Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Chang, Y.T.; Hong, Z.Y.; Lin, C.S. Targeting DNA Damage Response and Immune Checkpoint for Anticancer Therapy. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guscott, M.; Saha, A.; Maharaj, J.; McClelland, S.E. The multifaceted role of micronuclei in tumour progression: A whole organism perspective. Int J Biochem Cell B 2022, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Liu, D.S.; Wang, X.N.; Guo, Z.; Sun, H.A.; Song, Y.F.; Wang, D.G. DNA Damage and Activation of cGAS/ STING Pathway Induce Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, S.; Li, M.H.; Chen, Z.J.J. Old dogs, new trick: classic cancer therapies activate cGAS. Cell research 2020, 30, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, L.T.; Chen, L.Y. Role of the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer development and oncotherapeutic approaches. Embo Rep 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decout, A.; Katz, J.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Ablasser, A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Immunology 2021, 21, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhoum, S.F.; Ngo, B.; Laughney, A.M.; Cavallo, J.A.; Murphy, C.J.; Ly, P.; Shah, P.; Sriram, R.K.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Taunk, N.K. , et al. Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response. Nature 2018, 553, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhoum, S.; Ngo, B.; Bakhoum, A.; Cavallo-Fleming, J.A.; Murphy, C.W.; Powell, S.N.; Cantley, L. Chromosomal Instability Drives Metastasis Through a Cytosolic DNA Response. Int J Radiat Oncol 2018, 102, S118–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.Q.; Zhong, X.Y.; Meng, X.; Li, S.T.; Qian, X.Y.; Lu, H.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.J.; Ye, Z.J. , et al. Mitochondria-localized cGAS suppresses ferroptosis to promote cancer progression. Cell research 2023, 33, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Boire, A.; Jin, X.; Valiente, M.; Er, E.E.; Lopez-Soto, A.; Jacob, L.S.; Patwa, R.; Shah, H.; Xu, K. , et al. Carcinoma-astrocyte gap junctions promote brain metastasis by cGAMP transfer (vol 533, pg 493, 2016). Nature 2017, 544, 124–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlorn, B.L.; Gamez, E.R.; Li, S.Z.; Campos, S.K. Attenuation of cGAS/STING activity during mitosis. Life Sci Alliance 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.P.; Wang, F.; Cao, Y.J.; Dang, Y.F.; Ge, B.X. The multifaceted functions of cGAS. J Mol Cell Biol 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).