Submitted:

22 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

Aim

Eligibility criteria

Data extraction and management

Outcomes

Statistical analysis plan

Results

Meta-analysis

Prevalence of Multimorbidity Cohort

Gender differences

Rural-Urban differences

Difference between smokers and non-smokers

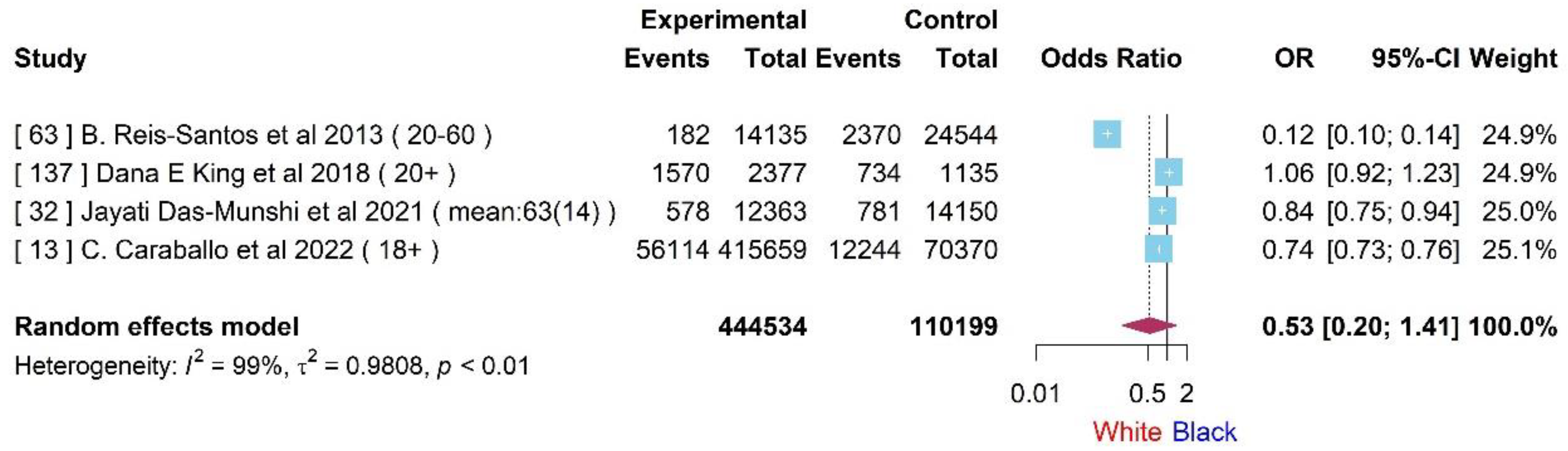

Differences between black and white patients

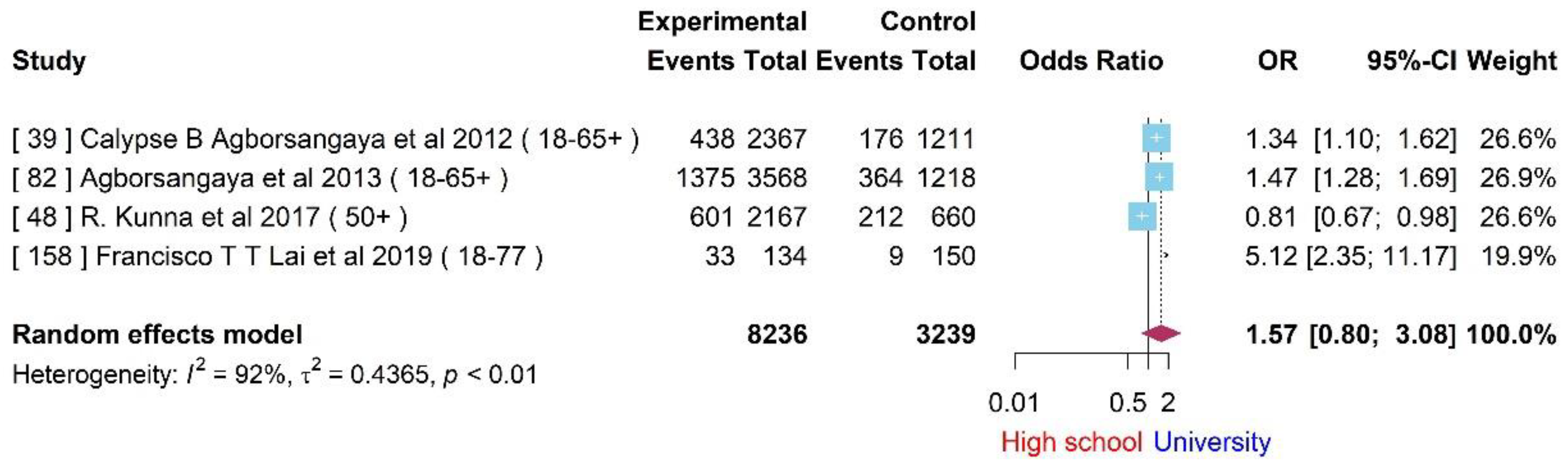

Differences in educational status

Difference among patients that consume alcohol

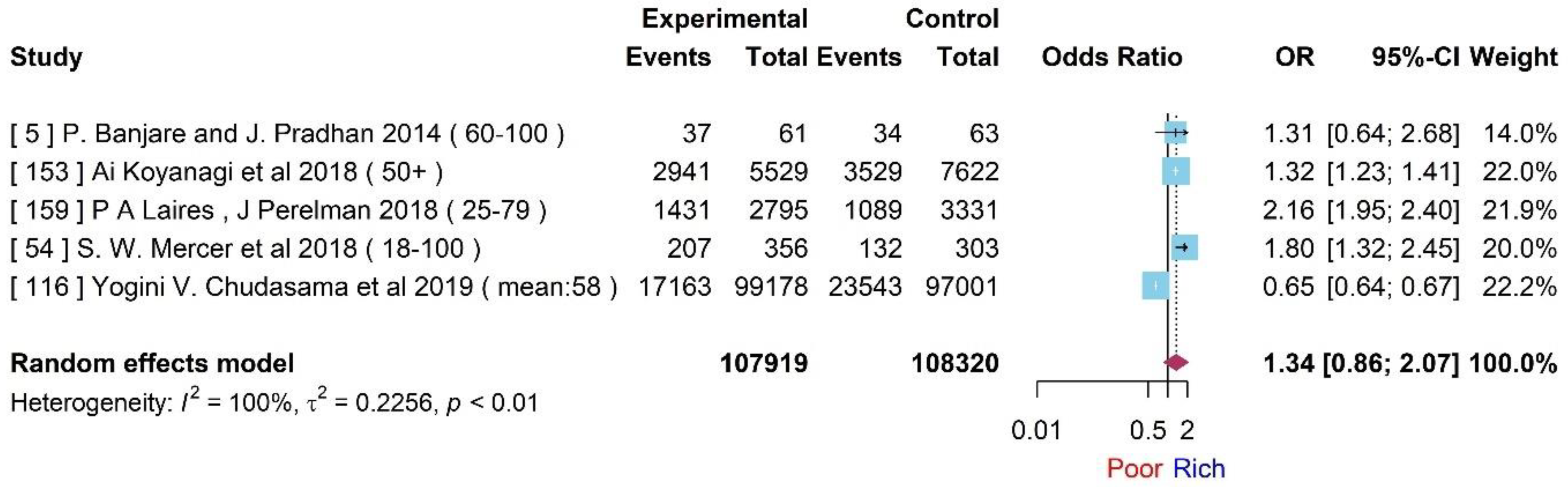

Socioeconomical status

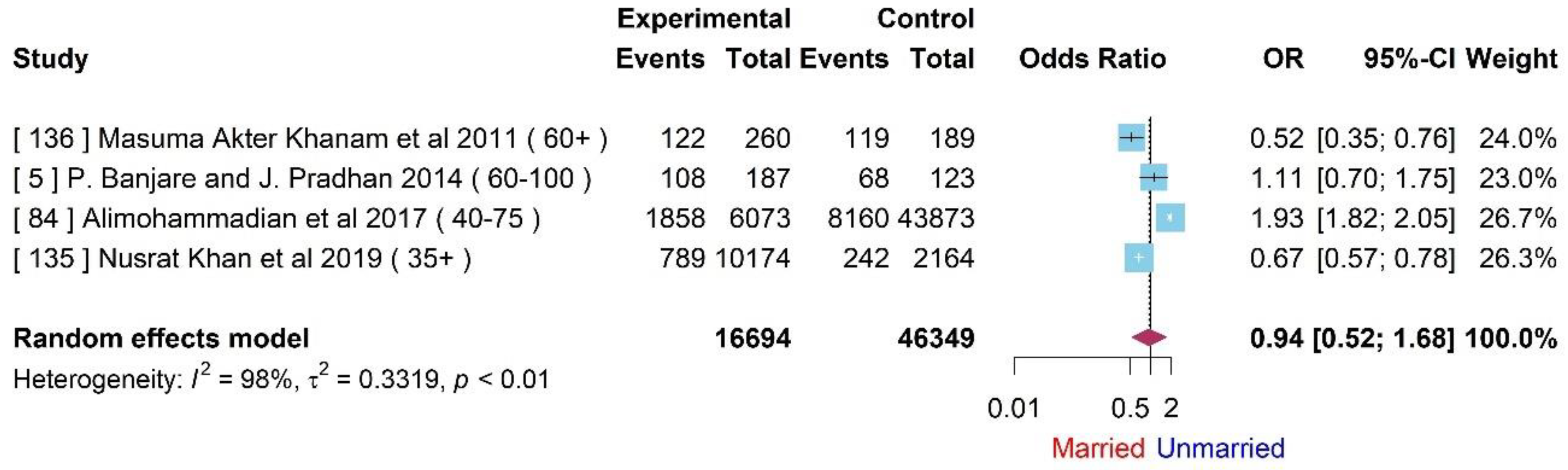

Difference between married and non-married

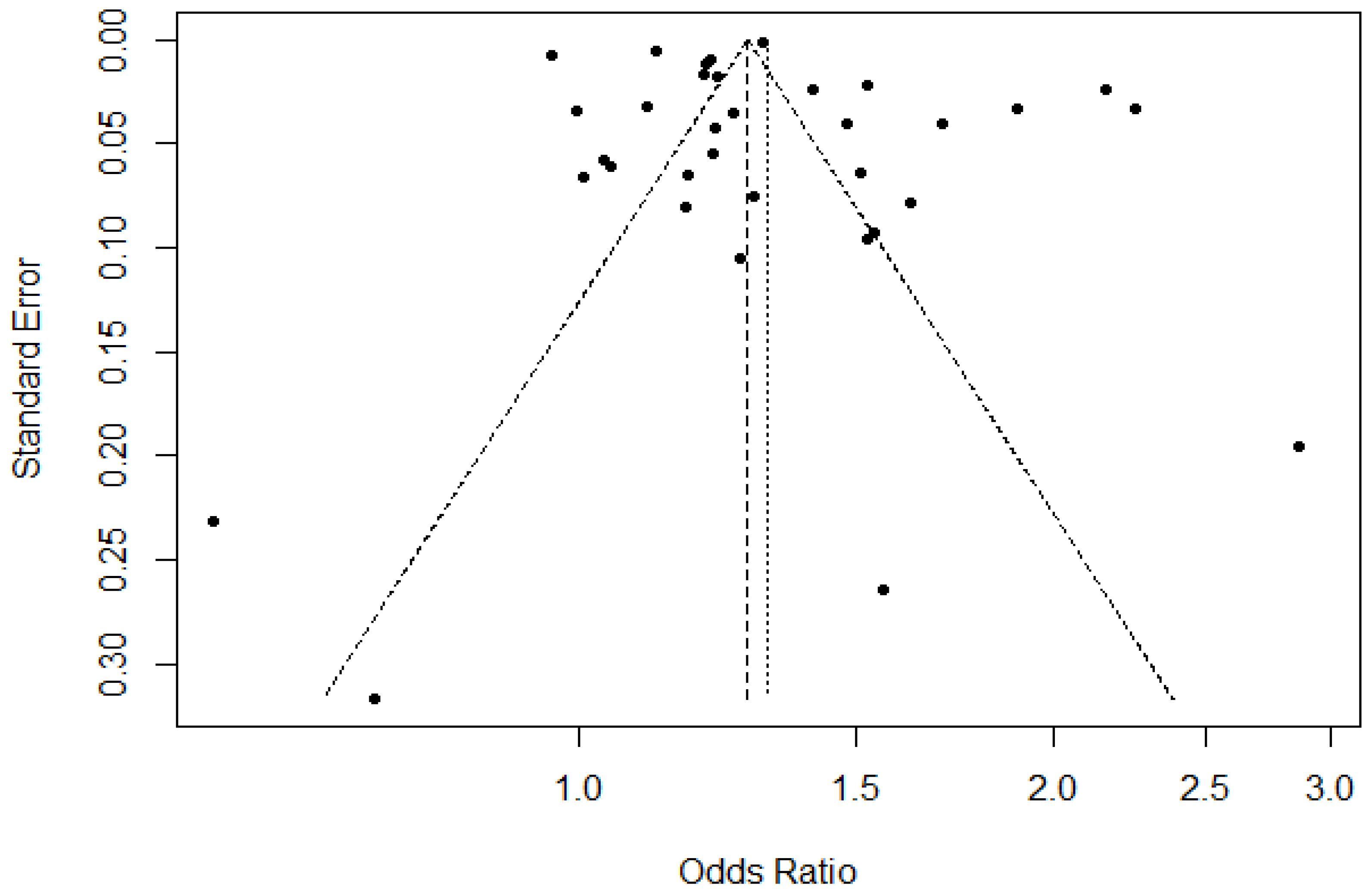

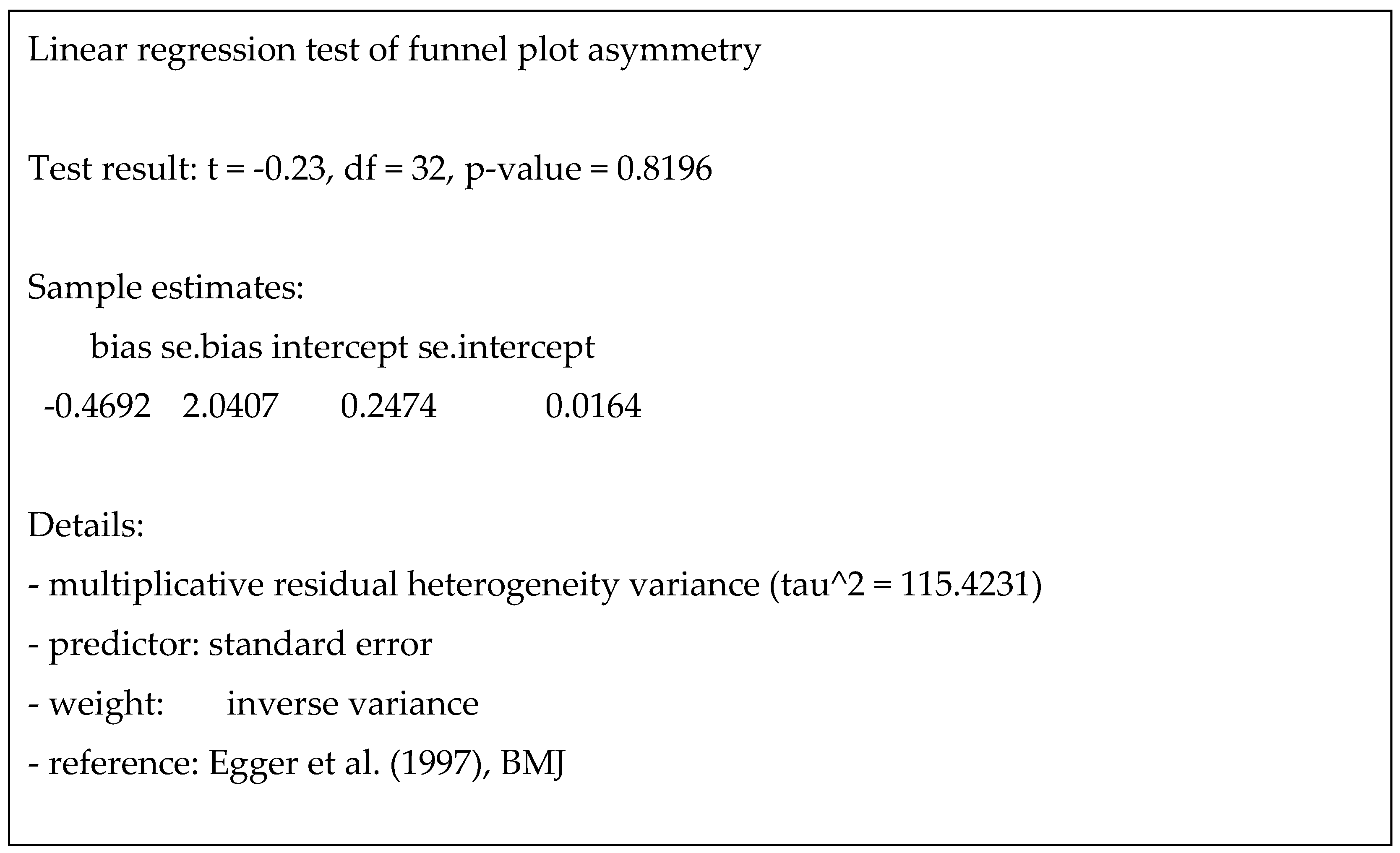

Publication Bias

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Consent for publication

References

- Murray CJL, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015, 386, 2145–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Manceau B, et al. The European general practice research network presents a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine and long term care, following a systematic review of relevant literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013, 14, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social Conditions As Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior.

- Sum, G.; Hone, T.; Atun, R.; Millett, C.; Suhrcke, M.; Mahal, A.; Koh, G.C.-H.; Lee, J.T. Multimorbidity and out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000505. [Google Scholar]

- Makovski, T.T.; Schmitz, S.; Zeegers, M.P.; Stranges, S.; van den Akker, M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 53, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Wu, C.; Odden, M.C.; Kim, D.H. Multimorbidity Patterns, Frailty, and Survival in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai FTT, Guthrie B, Wong SY, et al. Sex-specific intergenerational trends in morbidity burden and multimorbidity status in Hong Kong community: an age-period-cohort analysis of repeated population pen. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Uijen A, van de Lisdonk E. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008, 14, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen H, Manolova G, Daskalopoulou C, Vitoratou S, Prince M, Prina AM. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.

- J Comorb. 2019;9:2235042X1987093. [CrossRef]

- Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras ME, Almirall J, Maddocks H. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med. 2012, 10, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacken MAJB, Opstelten W, Vossen I, et al. Increased multimorbidity in patients in general practice in the period 2003–2009. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2011, 155, A3109. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, D.L.B. , Oliveras-Fabregas, A., Minobes-Molina, E. et al. Trends of multimorbidity in 15 European countries: a population-based study in community-dwelling adults aged 50 and over. BMC Public Health 21, 76 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Padhi A, Wei T, et al. Community prevalence and dyad disease pattern of multimorbidity in China and India: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2022, 7, e008880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados-Torres A, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Hancco-Saavedra J, Poblador-Plou B, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 254–266 https://doi org/101016/jjclinepi201309021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016, 71, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, Lewis C, Fahey T, Smith SM. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury SR, Chandra Das D, Sunna TC, Beyene J, Hossain A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 1018. [CrossRef]

- Zielinski A , Halling A . Association between age, gender and multimorbidity level and receiving home health care: a population-based Swedish study. BMC Res Notes.

- United Nations and Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World population ageing, 2019 highlights, NewYork, 2020.

- Gu J, Chao J, Chen W, et al. Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life among the community-dwelling elderly: a longitudinal study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018, 74, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahoumian TA, Phillips BR, Backus LI. Cigarette smoking, reduction and quit attempts: prevalence among veterans with coronary heart disease. Prev Chronic Dis 2016, 13, E41. [Google Scholar]

- Newson JT, Huguet N, Ramage-Morin PL, et al. Health behaviour changes after diagnosis of chronic illness among Canadians aged 50 or older. Health Rep 2012, 23, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Chen M, Si L. Multimorbidity and catastrophic health expenditure among patients with diabetes in China: a nationwide population-based study. BMJ Glob Health. 2022, 7, e007714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 26. Han BH, Moore AA, Sherman SE, Palamar JJ. Prevalence and correlates of binge drinking among older adults with multimorbidity. Drug Alcohol Depend. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, S. , Roderick, P.J., Kowal, P. et al. Multimorbidity and the inequalities of global ageing: a cross-sectional study of 28 countries using the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathirana TI, Jackson CA. Socioeconomic status and multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2018, 42, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puth MT, Weckbecker K, Schmid M, Münster E. Prevalence of multimorbidity in Germany: impact of age and educational level in a cross-sectional study on 19,294 adults. BMC Public Health. 2017, 17, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Li D, Mishra SR, Lim C, Dai X, Chen S, Xu X. Association between marital relationship and multimorbidity in middle-aged adults: a longitudinal study across the US, UK, Europe, and China. Maturitas. 2022, 155, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. N. Anushree, Prem Shankar Mishra,Prevalence of multi-morbidities among older adults in India: Evidence from national Sample Survey organization, 2017–2018, Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 2022, 15, 101025, ISSN 2213–3984. [CrossRef]

- Arias-de la Torre J, Vilagut G, Ronaldson A, Serrano-Blanco A, Martín V, Peters M, Valderas JM, Dregan A, Alonso J. Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2021, 6, e729–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse P, van der Wielen N, Banda PC, Channon AA. The impact of multi-morbidity on disability among older adults in South Africa: do hypertension and socio-demographic characteristics matter? Int J Equity Health. 2017, 16, 62, PMID: 28388911; PMCID: PMC5385014. [CrossRef]

- Banjare P, Pradhan J. Socio-economic inequalities in the prevalence of multi-morbidity among the rural elderly in Bargarh District of Odisha (India). PLoS One. 2014, 9, e97832, PMID: 24902041; PMCID: PMC4046974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, H. Q. , Kingston, A., Lourida, I., Robinson, L., Corner, L., Brayne, C. E.,... & Jagger, C. The contribution of multiple long-term conditions to widening inequalities in disability-free life expectancy over two decades: Longitudinal analysis of two cohorts using the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies. EClinicalMedicine, 2021, 39.

- Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardes, G. M. , Saulo, H., Santos, J. L. F., da Cruz Teixeira, D. S., de Oliveira Duarte, Y. A., & de Andrade, F. B. Effect of education and multimorbidity on mortality among older adults: findings from the health, well-being and ageing cohort study (SABE). Public Health 2021, 201, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquera A, Gulliford M, Dodhia H, Ledwaba-Chapman L, Durbaba S, Soley-Bori M, Fox-Rushby J, Ashworth M, Wang Y. Identifying longitudinal clusters of multimorbidity in an urban setting: A population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 1000; PMID: 34557797; PMCID: PMC8454750. [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Vázquez, E. , Fernández-Niño, J. A., & Astudillo-Garcia, C. I. Self-rated health, multimorbidity and depression in Mexican older adults: Proposal and evaluation of a simple conceptual model. Biomedica 2017, 37, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, J. E. , Hays, R., McDonagh, S. T., Bower, P., Pitchforth, E., Richards, S. H., & Campbell, J. L. Involving older people with multimorbidity in decision-making about their primary healthcare: a Cochrane systematic review of interventions (abridged). Patient Education and Counseling, 2020, 103, 2078–2094. [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo, C. , Herrin, J., Mahajan, S., Massey, D., Lu, Y., Ndumele, C. D.,... & Krumholz, H. M. Temporal trends in racial and ethnic disparities in multimorbidity prevalence in the United States, 1999-2018. The American Journal of Medicine, 2022, 135, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Carrilero, N. , Dalmau-Bueno, A., & García-Altés, A. (2020). Comorbidity patterns and socioeconomic inequalities in children under 15 with medical complexity: a population-based study. BMC pediatrics, 20, 1-10.

- Charlton, J. , Rudisill, C., Bhattarai, N., & Gulliford, M. Impact of deprivation on occurrence, outcomes and health care costs of people with multiple morbidity. Journal of health services research & policy, 2013, 18, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, S. , Srivastava, S., Kumar, P., & Patel, R. Decomposing urban-rural differences in multimorbidity among older adults in India: a study based on LASI data. BMC Public Health, 2022, 22, 502. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, G. K. K. , Chan, S. M., Chan, Y. H., Yip, T. C. F., Ma, H. M., Wong, G. L. H.,... & Woo, J. Differential impacts of multimorbidity on COVID-19 severity across the socioeconomic ladder in Hong Kong: a syndemic perspective. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2021, 18, 8168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper SA, McLean G, Guthrie B, McConnachie A, Mercer S, Sullivan F, Morrison J. Multiple physical and mental health comorbidity in adults with intellectual disabilities: population-based cross-sectional analysis. BMC Fam Pract. PMID: 26310664; PMCID: PMC4551707. [CrossRef]

- Corrao G, Rea F, Carle F, Di Martino M, De Palma R, Francesconi P, Lepore V, Merlino L, Scondotto S, Garau D, Spazzafumo L, Montagano G, Clagnan E, Martini N; working group “Monitoring and assessing care pathways (MAP)” of the Italian Ministry of Health. Measuring multimorbidity inequality across Italy through the multisource comorbidity score: a nationwide study. Eur J Public Health. 2020, 30, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, Â. K. , Bertoldi, A. D., Fontanella, A. T., Ramos, L. R., Arrais, P. S. D., Luiza, V. L.,... & Nunes, B. P. Does socioeconomic inequality occur in the multimorbidity among Brazilian adults? Revista de Saúde Pública, 2020, 54, 138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Araujo, M. E. A. , Silva, M. T., Galvao, T. F., Nunes, B. P., & Pereira, M. G. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Amazon Region of Brazil and associated determinants: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 2018, 8, e023398. [Google Scholar]

- Diderichsen, F. , Bender, A. M., Lyth, A. C., Andersen, I., Pedersen, J., & Bjørner, J. B. Mediating role of multimorbidity in inequality in mortality: a register study on the Danish population. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2022, 76, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- González-Chica, D. A. , Hill, C. L., Gill, T. K., Hay, P., Haag, D., & Stocks, N. Individual diseases or clustering of health conditions? Association between multiple chronic diseases and health-related quality of life in adults. Health and quality of life outcomes, 2017, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, R. M. , & Andrade, F. C. D. Healthy life-expectancy and multimorbidity among older adults: Do inequality and poverty matter? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2020, 90, 104157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halonen, P. , Raitanen, J., Jämsen, E., Enroth, L., & Jylhä, M. Chronic conditions and multimorbidity in population aged 90 years and over: associations with mortality and long-term care admission. Age and Ageing, 2019, 48, 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Hamiduzzaman, M. , Torres, S., Fletcher, A., Islam, M. R., Siddiquee, N. A., & Greenhill, J. Aging, care and dependency in multimorbidity: how do relationships affect older Bangladeshi women’s use of homecare and health services? Journal of Women & Aging, 2022, 34, 731–744. [Google Scholar]

- Alshamsan, R. , Lee, J. T., Rana, S., Areabi, H., & Millett, C. Comparative health system performance in six middle-income countries: cross-sectional analysis using World Health Organization study of global ageing and health. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2017, 110, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuan, V. , Denaxas, S., Patalay, P., Nitsch, D., Mathur, R., Gonzalez-Izquierdo, A.,... & Zwierzyna, M. Identifying and visualising multimorbidity and comorbidity patterns in patients in the English National Health Service: a population-based study. The Lancet Digital Health, 2023, 5, e16–e27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, N. , Doran, T., Prady, S. L., & Taylor, J. Closing the mortality gap for severe mental illness: are we going in the right direction? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2017, 211, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drake, R. E. , Essock, S. M., Shaner, A., Carey, K. B., Minkoff, K., Kola, L.,... & Rickards, L. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric services, 2001, 52, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, E. , Bakhai, C., Kar, P., Weaver, A., Bradley, D., Ismail, H.,... & Valabhji, J. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology, 2020, 8, 813–822. [Google Scholar]

- Ronaldson, A. , de la Torre, J. A., Prina, M., Armstrong, D., Das-Munshi, J., Hatch, S.,... & Dregan, A. Associations between physical multimorbidity patterns and common mental health disorders in middle-aged adults: A prospective analysis using data from the UK Biobank. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe,.

- Steed, L. , Lankester, J., Barnard, M., Earle, K., Hurel, S., & Newman, S. Evaluation of the UCL diabetes self-management programme (UCL-DSMP): a randomized controlled trial. Journal of health psychology, 2005, 10, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Divo, M. J. , Casanova, C., Marin, J. M., Pinto-Plata, V. M., De-Torres, J. P., Zulueta, J. J.,... & Celli, B. R. COPD comorbidities network. European Respiratory Journal, 2015, 46, 640–650. [Google Scholar]

- Wijlaars LPMM, Hardelid P, Guttmann A, Gilbert R. Emergency admissions and long-term conditions during transition from paediatric to adult care: a cross-sectional study using Hospital Episode Statistics data. BMJ Open. 2018, 8, e021015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, A. , Fleming, K., Kypridemos, C., Pearson-Stuttard, J., & O’Flaherty, M. Multimorbidity: the case for prevention. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2021, 75, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Head, A. , Fleming, K., Kypridemos, C., Schofield, P., Pearson-Stuttard, J., & O'Flaherty, M. Inequalities in incident and prevalent multimorbidity in England, 2004–2019: a population-based, descriptive study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 2021, 2, e489–e497. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. A. , Huxley, R. R., & Al Mamun, A. Multimorbidity prevalence and pattern in Indonesian adults: an exploratory study using national survey data. BMJ open, 2015, 5, e009810. [Google Scholar]

- Agborsangaya, C.B. , Lau, D., Lahtinen, M. et al. Multimorbidity prevalence and patterns across socioeconomic determinants: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 12, 201 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Jackson CA, Jones M, Tooth L, Mishra GD, Byles J, Dobson A. Multimorbidity patterns are differentially associated with functional ability and decline in a longitudinal cohort of older women. Age Ageing. 2015, 44, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantsch, A. G. , Alves, R. F. S., & Faerstein, E. Educational inequality in Rio de Janeiro and its impact on multimorbidity: evidence from the Pró-Saúde study. A cross-sectional analysis. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 2018, 136, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jerliu, N. , Toçi, E., Burazeri, G., Ramadani, N., & Brand, H. Prevalence and socioeconomic correlates of chronic morbidity among elderly people in Kosovo: a population-based survey. BMC geriatrics, 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M. C. , Crilly, M., Black, C., Prescott, G. J., & Mercer, S. W. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. European journal of public health, 2019, 29, 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- McQueenie, R. , Foster, H. M., Jani, B. D., Katikireddi, S. V., Sattar, N., Pell, J. P.,... & Nicholl, B. I. Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and COVID-19 infection within the UK Biobank cohort. PloS one, 2020, 15, e0238091. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, T. , Hohmann, C., Standl, M., Wijga, A. H., Gehring, U., Melén, E.,... & Roll, S. The sex-shift in single disease and multimorbid asthma and rhinitis during puberty-a study by MeDALL. Allergy, 2018, 73, 602–614. [Google Scholar]

- Khanolkar, A. R. , Chaturvedi, N., Kuan, V., Davis, D., Hughes, A., Richards, M.,... & Patalay, P. Socioeconomic inequalities in prevalence and development of multimorbidity across adulthood: a longitudinal analysis of the MRC 1946 national survey of health and development in the UK. PLoS medicine, 2021, 18, e1003775. [Google Scholar]

- Knies, G. , & Kumari, M. Multimorbidity is associated with the income, education, employment and health domains of area-level deprivation in adult residents in the UK. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12, 7280. [Google Scholar]

- Kunna, R. , San Sebastian, M., & Stewart Williams, J. Measurement and decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in single and multimorbidity in older adults in China and Ghana: results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). International journal for equity in health, 2017, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, R. N. , & Lai, M. S. The influence of socio-economic status and multimorbidity patterns on healthcare costs: a six-year follow-up under a universal healthcare system. International journal for equity in health, 2013, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mondor, L. , Maxwell, C. J., Hogan, D. B., Bronskill, S. E., Gruneir, A., Lane, N. E., & Wodchis, W. P. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilization among home care clients with dementia in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective analysis of a population-based cohort. PLoS medicine, 2017, 14, e1002249. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, K. D. , Mercer, S. W., Wyke, S., Grieve, E., Guthrie, B., Watt, G., & Fenwick, E. A. Double trouble: the impact of multimorbidity and deprivation on preference-weighted health related quality of life a cross sectional analysis of the Scottish Health Survey. International journal for equity in health, 2013, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. , Wang, Y., Hou, L., Zuo, Z., Zhang, N., & Wei, A. Multimorbidity patterns in old adults and their associated multi-layered factors: a cross-sectional study. BMC geriatrics, 2021, 21, 372. [Google Scholar]

- McQueenie, R. , Foster, H. M., Jani, B. D., Katikireddi, S. V., Sattar, N., Pell, J. P.,... & Nicholl, B. I. Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and COVID-19 infection within the UK Biobank cohort. PloS one, 2020, 15, e0238091. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M. C. , Crilly, M., Black, C., Prescott, G. J., & Mercer, S. W. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. European journal of public health, 2019, 29, 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mondor, L. , Cohen, D., Khan, A. I., & Wodchis, W. P. Income inequalities in multimorbidity prevalence in Ontario, Canada: a decomposition analysis of linked survey and health administrative data. International journal for equity in health, 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Niksic, M. , Redondo-Sanchez, D., Chang, Y. L., Rodriguez-Barranco, M., Exposito-Hernandez, J., Marcos-Gragera, R.,... & Luque-Fernandez, M. A. The role of multimorbidity in short-term mortality of lung cancer patients in Spain: a population-based cohort study. BMC cancer, 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, B. P. , Flores, T. R., Mielke, G. I., Thumé, E., & Facchini, L. A. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 2016, 67, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. , Chhetri, J. K., Chang, Y., Zheng, Z., Ma, L., & Chan, P. Intrinsic capacity vs. multimorbidity: a function-centered construct predicts disability better than a disease-based approach in a community-dwelling older population cohort. Frontiers in medicine, 2021, 8, 753295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orueta, J. F. , Nuño-Solinís, R., García-Alvarez, A., & Alonso-Morán, E. Prevalence of multimorbidity according to the deprivation level among the elderly in the Basque Country. BMC Public Health, 2013, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. J. , Perera, B., Henley, W., Angus-Leppan, H., Sawhney, I., Watkins, L.,... & Shankar, R. Epilepsy related multimorbidity, polypharmacy and risks in adults with intellectual disabilities: a national study. Journal of Neurology, 2022, 269, 2750–2760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. I. , Azcoaga-Lorenzo, A., Agrawal, U., Kennedy, J. I., Fagbamigbe, A. F., Hope, H.,... & McCowan, C. Epidemiology of pre-existing multimorbidity in pregnant women in the UK in 2018: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 2022, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Reis-Santos, B. , Gomes, T. , Macedo, L. R., Horta, B. L., Riley, L. W., & Maciel, E. L. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among tuberculosis patients in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. International journal for equity in health, 2013, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- ROMANA, G. Q. , KISLAYA, I., SALVADOR, M. R., GONÇALVES, S. C., NUNES, B., & DIAS, C. Multimorbidity in Portugal: Results from The First National Health Examination Survey Multimorbilidade em Portugal: Dados do Primeiro Inquérito Nacional de Saúde com Exame Físico.

- Ryan, B. L. , Bray Jenkyn, K., Shariff, S. Z., Allen, B., Glazier, R. H., Zwarenstein, M.,... & Stewart, M. Beyond the grey tsunami: a cross-sectional population-based study of multimorbidity in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 2018, 109, 845–854. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, L. , Green, M., Rowe, F., Ben-Shlomo, Y., & Morrissey, K. Social determinants of multimorbidity and multiple functional limitations among the ageing population of England, 2019, 2002–2015. SSM-population health, 8, 100413.

- Singh-Manoux, A. , Fayosse, A., Sabia, S., Tabak, A., Shipley, M., Dugravot, A., & Kivimäki, M. Clinical, socioeconomic, and behavioural factors at age 50 years and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity and mortality: a cohort study. PLoS medicine, 2018, 15, e1002571. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. J. , McLean, G., Martin, D., Martin, J. L., Guthrie, B., Gunn, J., & Mercer, S. W. Depression and multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study of 1,751,841 patients in primary care. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 2014, 75, 4205. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. J. , Belot, A. , Quartagno, M., Luque Fernandez, M. A., Bonaventure, A., Gachau, S.,... & Njagi, E. N. Excess mortality by multimorbidity, socioeconomic, and healthcare factors, amongst patients diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell or follicular lymphoma in England. Cancers, 2021, 13, 5805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Zon, S. K. , Reijneveld, S. A., Galaurchi, A., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Almansa, J., & Bültmann, U. Multimorbidity and the transition out of full-time paid employment: a longitudinal analysis of the health and retirement study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 2020, 75, 705–715. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliadis, H. M. , Gontijo Guerra, S., Berbiche, D., & Pitrou, I. E. (2021). The factors associated with 3-year mortality stratified by physical and mental multimorbidity and area of residence deprivation in primary care community-living older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 33(7-8), 545-556.

- Violan, C. , Foguet-Boreu, Q., Flores-Mateo, G., Salisbury, C., Blom, J., Freitag, M.,... & Valderas, J. M. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PloS one, 2014, 9, e102149. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H. , Xu, X., Hu, J., Zhao, Z., Si, Z., Wang, X.,... & Li, X. (2023). Association between exposure to Occupational hazard factors and multimorbidity in steelworkers: A Cross-Sectional Study.

- Zhao, Y. , Atun, R., Oldenburg, B., McPake, B., Tang, S., Mercer, S. W.,... & Lee, J. T. Physical multimorbidity, health service use, and catastrophic health expenditure by socioeconomic groups in China: an analysis of population-based panel data. The Lancet Global Health, 2020, 8, e840–e849. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. H. , Wang, J. J., Lawson, K. D., Wong, S. Y., Wong, M. C., Li, F. J.,... & Mercer, S. W. Relationships of multimorbidity and income with hospital admissions in 3 health care systems. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2015, 13, 164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, S. , Van den Akker, M., Hajema, K. J., van Ingen, A. V., Metsemakers, J. F. M., Verhey, F. R. J., & Van Boxtel, M. P. J. Multimorbidity and its relation to subjective memory complaints in a large general population of older adults. International psychogeriatrics, 2011, 23, 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, S. , Van den Akker, M., Tan, F. E. S., Verhey, F. R. J., Metsemakers, J. F. M., & Van Boxtel, M. P. J. Influence of multimorbidity on cognition in a normal aging population: a 12-year follow-up in the Maastricht Aging Study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 2011, 26, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, S. , van den Akker, M. , Bosma, H., Tan, F., Verhey, F., Metsemakers, J., & van Boxtel, M. The effect of multimorbidity on health related functioning: temporary or persistent? Results from a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of psychosomatic research, 2012, 73, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Abizanda, P. , Romero, L. , Sanchez-Jurado, P. M., Martinez-Reig, M., Alfonso-Silguero, S. A., & Rodriguez-Manas, L. Age, frailty, disability, institutionalization, multimorbidity or comorbidity. Which are the main targets in older adults?. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 2014, 18, 622–627. [Google Scholar]

- Agborsangaya, C. B. , Lau, D. , Lahtinen, M., Cooke, T., & Johnson, J. A. Health-related quality of life and healthcare utilization in multimorbidity: results of a cross-sectional survey. Quality of life Research, 2013, 22, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agborsangaya, C. B. , Lau, D. , Lahtinen, M., Cooke, T., & Johnson, J. A. Health-related quality of life and healthcare utilization in multimorbidity: results of a cross-sectional survey. Quality of life Research, 2013, 22, 791–799. [Google Scholar]

- Agborsangaya, C. B. , Ngwakongnwi, E. , Lahtinen, M., Cooke, T., & Johnson, J. A. Multimorbidity prevalence in the general population: the role of obesity in chronic disease clustering. BMC Public Health, 2013, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, S. , Wensink, M. , Ahrenfeldt, L. J., Christensen, K., & Lindahl-Jacobsen, R. Age-specific cancer rates: a bird's-eye view on progress. Annals of Epidemiology, 2020, 48, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alimohammadian, M. , Majidi, A. , Yaseri, M., Ahmadi, B., Islami, F., Derakhshan, M.,... & Malekzadeh, R. Multimorbidity as an important issue among women: results of a gender difference investigation in a large population-based cross-sectional study in West Asia. BMJ open, 2017, 7, e013548. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, J. , Sellaro, R. , & Ries Merikangas, K. Multimorbidity of psychiatric disorders as an indicator of clinical severity. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 2002, 252, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, S. , Wensink, M. , Ahrenfeldt, L. J., Christensen, K., & Lindahl-Jacobsen, R. Age-specific cancer rates: a bird's-eye view on progress. Annals of Epidemiology, 2020, 48, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gausi, B. , Berkowitz, N. , Jacob, N., & Oni, T. Treatment outcomes among adults with HIV/non-communicable disease multimorbidity attending integrated care clubs in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS research and therapy, 2021, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M. L. Peer Reviewed: Differences Between Younger and Older US Adults With Multiple Chronic Conditions. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2017, 14.

- Amaral, T. L. M. , Amaral, C. D. A., Lima, N. S. D., Herculano, P. V., Prado, P. R. D., & Monteiro, G. T. R. Multimorbidity, depression and quality of life among elderly people assisted in the Family Health Strategy in Senador Guiomard, Acre, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 2018, 23, 3077–3084. [Google Scholar]

- An, K. O. , & Kim, J. Association of sarcopenia and obesity with multimorbidity in Korean adults: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2016, 17, 960–e1. [Google Scholar]

- An, K. O. , & Kim, J. Association of sarcopenia and obesity with multimorbidity in Korean adults: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2016, 17, 960–e1. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, T. , Arnold-Reed, D. E., Popescu, A., Soliman, B., Bulsara, M. K., Fine, H.,... & Moorhead, R. G. Multimorbidity in patients attending 2 Australian primary care practices. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2013, 11, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Arokiasamy, P. , Uttamacharya, U., Jain, K., Biritwum, R. B., Yawson, A. E., Wu, F.,... & Kowal, P. The impact of multimorbidity on adult physical and mental health in low-and middle-income countries: what does the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) reveal? BMC medicine, 2015, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnige, J. , Braspenning, J., Schellevis, F., Stirbu-Wagner, I., Westert, G., & Korevaar, J. The prevalence of disease clusters in older adults with multiple chronic diseases–a systematic literature review. PloS one, 2013, 8, e79641. [Google Scholar]

- Zemedikun, D. T. , Gray, L. J., Khunti, K., Davies, M. J., & Dhalwani, N. N. (2018, July). Patterns of multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults: an analysis of the UK biobank data. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 93, No. 7, pp. 857–866). Elsevier.

- Mounce, L. T. , Campbell, J. L., Henley, W. E., Arreal, M. C. T., Porter, I., & Valderas, J. M. Predicting incident multimorbidity. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2018, 16, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A. W. , Price, K. , Gill, T. K., Adams, R., Pilkington, R., Carrangis, N.,... & Wilson, D. Multimorbidity-not just an older person's issue. Results from an Australian biomedical study. BMC public health, 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort, D. , Koyanagi, A., Ward, P. B., Veronese, N., Carvalho, A. F., Solmi, M.,... & Stubbs, B. Perceived stress and its relationship with chronic medical conditions and multimorbidity among 229,293 community-dwelling adults in 44 low-and middle-income countries. American journal of epidemiology, 2017, 186, 979–989. [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort, D. , Koyanagi, A., Ward, P. B., Rosenbaum, S., Schuch, F. B., Mugisha, J.,... & Stubbs, B. (2017). Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity and physical activity across 46 low-and middle-income countries. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14, 1-13.

- Aubert, C. E. , Schnipper, J. L., Roumet, M., Marques-Vidal, P., Stirnemann, J., Auerbach, A. D.,... & Donzé, J. Best definitions of multimorbidity to identify patients with high health care resource utilization. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 2020, 4, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Autenrieth, C. S. , Kirchberger, I., Heier, M., Zimmermann, A. K., Peters, A., Döring, A., & Thorand, B. Physical activity is inversely associated with multimorbidity in elderly men: results from the KORA-Age Augsburg Study. Preventive medicine, 2013, 57, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bähler, C. , Huber, C. A., Brüngger, B., & Reich, O. Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: a claims data based observational study. BMC health services research, 2015, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort, D. , Koyanagi, A. , Ward, P. B., Veronese, N., Carvalho, A. F., Solmi, M.,... & Stubbs, B. Perceived stress and its relationship with chronic medical conditions and multimorbidity among 229,293 community-dwelling adults in 44 low-and middle-income countries. American journal of epidemiology, 2017, 186, 979–989. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, S. , Inderjeeth, C., & Raymond, W. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index scores do not influence Functional Independence Measure score gains in older rehabilitation patients. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 2016, 35, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biswas, T. , Townsend, N., Islam, M. S., Islam, M. R., Gupta, R. D., Das, S. K., & Al Mamun, A. Association between socioeconomic status and prevalence of non-communicable diseases risk factors and comorbidities in Bangladesh: findings from a nationwide cross-sectional survey. BMJ open, 2019, 9, e025538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, A. , Hann, M., Howells, K., Panagioti, M., Sidaway, M., Reeves, D., & Bower, P. Patient activation in older people with long-term conditions and multimorbidity: correlates and change in a cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Services Research, 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, C. B. , Deng, L. ( 34, 2390–2396. [PubMed]

- Stewart, M. , Fortin, M., Britt, H. C., Harrison, C. M., & Maddocks, H. L. Comparisons of multi-morbidity in family practice—issues and biases. Family Practice, 2013, 30, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Broeiro-Gonçalves, P. , Nogueira, P. , & Aguiar, P. Multimorbidity and disease severity by age groups, in inpatients: cross-sectional study. Portuguese Journal of Public Health, 2019, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig, K. , Leff, B., Kent, D., Dy, S., Brunnhuber, K., Burgers, J. S.,... & Boyd, C. M. A framework for crafting clinical practice guidelines that are relevant to the care and management of people with multimorbidity. Journal of general internal medicine, 2014, 29, 670–679. [Google Scholar]

- Buurman, B. M. , Frenkel, W. J., Abu-Hanna, A., Parlevliet, J. L., & de Rooij, S. E. Acute and chronic diseases as part of multimorbidity in acutely hospitalized older patients. European journal of internal medicine, 2016, 27, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Larrañaga, A. , Vetrano, D. L., Onder, G., Gimeno-Feliu, L. A., Coscollar-Santaliestra, C., Carfí, A.,... & Fratiglioni, L. Assessing and measuring chronic multimorbidity in the older population: a proposal for its operationalization. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2017, 72, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Canevelli, M. , Raganato, R., Remiddi, F., Quarata, F., Valletta, M., Bruno, G., & Cesari, M. Counting deficits or diseases? the agreement between frailty and multimorbidity in subjects with cognitive disturbances. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 2020, 32, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, A. M. , Sauver, J. L. S., Gerber, Y., Manemann, S. M., Boyd, C. M., Dunlay, S. M.,... & Roger, V. L. Multimorbidity in heart failure: a community perspective. The American journal of medicine, 2015, 128, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. , Cheng, M., Zhuang, Y., & Broad, J. B. Multimorbidity among middle-aged and older persons in urban China: Prevalence, characteristics and health service utilization. Geriatrics & gerontology international, 2018, 18, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, N. M. , Ng, Y. S., Chu, T. K., & Lau, P. Factors affecting prescription of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with established cardiovascular disease/chronic kidney disease in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. BMC Primary Care, 2022, 23, 317. [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama, Y. V. , Khunti, K. K., Zaccardi, F., Rowlands, A. V., Yates, T., Gillies, C. L.,... & Dhalwani, N. N. Physical activity, multimorbidity, and life expectancy: a UK Biobank longitudinal study. BMC medicine, 2019, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cimarras-Otal, C. , Calderón-Larrañaga, A., Poblador-Plou, B., González-Rubio, F., Gimeno-Feliu, L. A., Arjol-Serrano, J. L., & Prados-Torres, A. Association between physical activity, multimorbidity, self-rated health and functional limitation in the Spanish population. BMC public health, 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. Y. , Choi, E. P. H., Wan, E. Y. F., & Lam, C. L. K. Health-related quality of life mediates associations between multi-morbidity and depressive symptoms in Chinese primary care patients. Family practice, 2016, 33, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S. , & Agrawal, P. K. Association between body mass index and prevalence of multimorbidity in low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. International journal of medicine and public health, 2016, 6, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, J. M. , Ayton, D. R., Densley, K., Pallant, J. F., Chondros, P., Herrman, H. E., & Dowrick, C. F. The association between chronic illness, multimorbidity and depressive symptoms in an Australian primary care cohort. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 2012, 47, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, H. Y. , Kim, T. H., Sheen, Y. H., Lee, S. W., An, J., Kim, M. A.,... & Yon, D. K. Serum heavy metal levels are associated with asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, allergic multimorbidity, and airflow obstruction. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, 2019, 7, 2912–2915. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon, P. , Nicholl, B. I., Jani, B. D., Lee, D., McQueenie, R., & Mair, F. S. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. The Lancet Public Health, 2018, 3, e323–e332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jantsch, A. G. , Alves, R. F. S., & Faerstein, E. Educational inequality in Rio de Janeiro and its impact on multimorbidity: evidence from the Pró-Saúde study. A cross-sectional analysis. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 2018, 136, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jovic, D. , Vukovic, D. , & Marinkovic, J. Prevalence and patterns of multi-morbidity in Serbian adults: a cross-sectional study. PloS one, 2016, 11, e0148646. [Google Scholar]

- Juul-Larsen, H. G. , Christensen, L. D., Bandholm, T., Andersen, O., Kallemose, T., Jørgensen, L. M., & Petersen, J. (2020). Patterns of multimorbidity and differences in healthcare utilization and complexity among acutely hospitalized medical patients (≥ 65 Years)–a latent class approach. Clinical epidemiology, 245-259.

- Juul-Larsen, H. G. , Christensen, L. D., Bandholm, T., Andersen, O., Kallemose, T., Jørgensen, L. M., & Petersen, J. (2020). Patterns of multimorbidity and differences in healthcare utilization and complexity among acutely hospitalized medical patients (≥ 65 Years)–a latent class approach. Clinical epidemiology, 245-259.

- Fortin, M. , Bravo, G. , Hudon, C., Vanasse, A., & Lapointe, L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2005, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ie, K. , Felton, M. , Springer, S., Wilson, S. A., & Albert, S. M. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy in family medicine residency practices. Journal of Pharmacy Technology, 2017, 33, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki, T. , Kobayashi, E. , Fukaya, T., Takahashi, Y., Shinkai, S., & Liang, J. Association of physical performance and self-rated health with multimorbidity among older adults: results from a nationwide survey in Japan. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2019, 84, 103904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A. , de Heer, H. D., & Bea, J. W. Initiating exercise interventions to promote wellness in cancer patients and survivors. Oncology (Williston Park, NY), 2017, 31, 711. [Google Scholar]

- Demirchyan, A. , Khachadourian, V., Armenian, H. K., & Petrosyan, V. (2013). Short and long term determinants of incident multimorbidity in a cohort of 1988 earthquake survivors in Armenia. International journal for equity in health, 12, 1-8.

- Fabbri, E. , Zoli, M. , Gonzalez-Freire, M., Salive, M. E., Studenski, S. A., & Ferrucci, L. Aging and multimorbidity: new tasks, priorities, and frontiers for integrated gerontological and clinical research. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2015, 16, 640–647. [Google Scholar]

- Blay, S. L. , Fillenbaum, G. G., & Peluso, E. T. Differential characteristics of young and midlife adult users of psychotherapy, psychotropic medications, or both: information from a population representative sample in São Paulo, Brazil. BMC psychiatry, 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. , & Song, Y. M. The association between submarine service and multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study of Korean naval personnel. BMJ open, 2017, 7, e017776. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C. , Britt, H. , Miller, G., & Henderson, J. Examining different measures of multimorbidity, using a large prospective cross-sectional study in Australian general practice. BMJ open, 2014, 4, e004694. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. , Rahman, M. , Mitra, D., & Afsana, K. Prevalence of multimorbidity among Bangladeshi adult population: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 2019, 9, e030886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khanam, M. A. , Streatfield, P. K., Kabir, Z. N., Qiu, C., Cornelius, C., & Wahlin, Å. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among elderly people in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Journal of health, population, and nutrition, 2011, 29, 406. [Google Scholar]

- King, D. E. , Xiang, J. , & Pilkerton, C. S. Multimorbidity trends in United States adults, 1988–2014. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 2018, 31, 503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, K. , Lim, E. , Davis, J., & Chen, J. J. Racial-ethnic disparities in self-reported health status among US adults adjusted for sociodemographics and multimorbidities, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. Ethnicity & health, 2020, 25, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gaulin, M. , Simard, M. , Candas, B., Lesage, A., & Sirois, C. Combined impacts of multimorbidity and mental disorders on frequent emergency department visits: a retrospective cohort study in Quebec, Canada. CMAJ, 2019, 191, E724–E732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Larrañaga, A. , Vetrano, D. L., Onder, G., Gimeno-Feliu, L. A., Coscollar-Santaliestra, C., Carfí, A.,... & Fratiglioni, L. Assessing and measuring chronic multimorbidity in the older population: a proposal for its operationalization. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2017, 72, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Dhalwani, N. N. , Zaccardi, F. , O’Donovan, G., Carter, P., Hamer, M., Yates, T., & Khunti, K. Association between lifestyle factors and the incidence of multimorbidity in an older English population. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2017, 72, 528–534. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, S. , Herzig, L. , N’Goran, A. A., Déruaz-Luyet, A., & Haller, D. M. Prevalence of multimorbidity in general practice: a cross-sectional study within the Swiss Sentinel Surveillance System (Sentinella). BMJ open, 2018, 8, e019616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M. , Bravo, G. , Hudon, C., Vanasse, A., & Lapointe, L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2005, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galenkamp, H. , Gagliardi, C. , Principi, A., Golinowska, S., Moreira, A., Schmidt, A. E.,... & Deeg, D. J. Predictors of social leisure activities in older Europeans with and without multimorbidity. European Journal of Ageing, 2016, 13, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gawron, L. M. , Sanders, J. N., Sward, K., Poursaid, A. E., Simmons, R., & Turok, D. K. Multi-morbidity and highly effective contraception in reproductive-age women in the US Intermountain West: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2020, 35, 637–642. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, R. R. , Hojeij, S. , Elzein, K., Chaaban, J., & Seyfert, K. Associations between life conditions and multi-morbidity in marginalized populations: the case of Palestinian refugees. The European Journal of Public Health, 2014, 24, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrison, C. , Britt, H. , Miller, G., & Henderson, J. Examining different measures of multimorbidity, using a large prospective cross-sectional study in Australian general practice. BMJ open, 2014, 4, e004694. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, S. (2017). Prevalence, correlates, and time trends of multiple chronic conditions among Israeli adults: estimates from the Israeli National Health Interview Survey, 2014–2015. Preventing chronic disease, 14.

- Miller, J. L. , Thylén, I. , Elayi, S. C., Etaee, F., Fleming, S., Czarapata, M. M.,... & Moser, D. K. Multi-morbidity burden, psychological distress, and quality of life in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients: results from a nationwide study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 2019, 120, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernández, B. , Reilly, R. B., & Kenny, R. A. Investigation of multimorbidity and prevalent disease combinations in older Irish adults using network analysis and association rules. Scientific reports, 2019, 9, 14567. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C. Y. H. , Tay, S. H., McIntyre, R. S., Ho, R., Tam, W. W., & Ho, C. S. Elucidating a bidirectional association between rheumatoid arthritis and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders, 2022, 311, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, A. , Robinson, L., Booth, H., Knapp, M., Jagger, C., & Modem Project. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age and ageing, 2018, 47, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garin, N. , Koyanagi, A., Chatterji, S., Tyrovolas, S., Olaya, B., Leonardi, M.,... & Haro, J. M. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2016, 71, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsman, D. M. , Deeg, D. J., & Stalman, W. A. Comorbidity of somatic chronic diseases and decline in physical functioning: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 2004, 57, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, K. , König, H. H., & Hajek, A. The association of multimorbidity, loneliness, social exclusion and network size: findings from the population-based German Ageing Survey. BMC Public Health, 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, K. , König, H. H., & Hajek, A. The longitudinal association of multimorbidity on loneliness and network size: Findings from a population-based study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 2019, 34, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai, F. T. , Ma, T. W., & Hou, W. K. Multimorbidity is associated with more subsequent depressive symptoms in three months: a prospective study of community-dwelling adults in Hong Kong. International psychogeriatrics, 2019, 31, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F. T. , Wong, S. Y., Yip, B. H., Guthrie, B., Mercer, S. W., Chung, R. Y.,... & Yeoh, E. K. Multimorbidity in middle age predicts more subsequent hospital admissions than in older age: a nine-year retrospective cohort study of 121,188 discharged in-patients. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2019, 61, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laires, P. A. , & Perelman, J. The current and projected burden of multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study in a Southern Europe population. European journal of ageing, 2019, 16, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lang, K. , Alexander, I. M., Simon, J., Sussman, M., Lin, I., Menzin, J.,... & Hsu, M. A. The impact of multimorbidity on quality of life among midlife women: findings from a US nationally representative survey. Journal of Women's Health, 2015, 24, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le Cossec, C. , Perrine, A. L., Beltzer, N., Fuhrman, C., & Carcaillon-Bentata, L. Pre-frailty, frailty, and multimorbidity: prevalences and associated characteristics from two French national surveys. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 2016, 20, 860–869. [Google Scholar]

- Vogeli, C. , Shields, A. E., Lee, T. A., Gibson, T. B., Marder, W. D., Weiss, K. B., & Blumenthal, D. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. Journal of general internal medicine, 2007, 22, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. W. , Lee, W. J., Lin, M. H., Peng, L. N., Loh, C. H., Chen, L. K., & Lu, C. C. Quality of life among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: function matters more than multimorbidity. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 2021, 95, 104423. [Google Scholar]

- Lujic, S. , Randall, D. A., Simpson, J. M., Falster, M. O., & Jorm, L. R. Interaction effects of multimorbidity and frailty on adverse health outcomes in elderly hospitalised patients. Scientific reports, 2022, 12, 14139. [Google Scholar]

- Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F. , Anastasiadou, D., Codagnone, C., Nuño-Solinís, R., & Garcia-Zapirain Soto, M. B. Electronic health use in the European Union and the effect of multimorbidity: cross-sectional survey. Journal of medical Internet research, 2018, 20, e165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Authors | Year | Study Type | Country | Sample Size | Mean Age | Age Range | Meta-analysis Inclusion Y/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S. Afshar et al [34] |

2015 | Cross-sectional |

Myanmar | 125404 | 72 | N | |

| 2 | K. N. Anushree and P. S. Mishra [35] | 2022 | India |

42756 | 60-100 | N | ||

| 3 | J. Arias-de la Torre et al [36] | 2021 | Observational cohort study |

UK | 34776 | 20-50 | Y | |

| 4 | J. E. O. Ataguba [37] | 2013 | South Africa |

26.80 | N | |||

| 5 | P. Banjare and J. Pradhan [38] | 2014 | India |

310 | 60-100 | Y | ||

| 6 | H. Q. Bennett et al [39] | 2021 | UK | 15431 | 75.6 | N | ||

| 7 | Marjan van den Akker et al [40] | 1998 | Longitudinal |

Netherlands |

60857 | 25-100 | Y |

|

| 8 | Jennifer L Wolff et al [41] | 2002 | Cross sectional |

USA | 1 217 103 | 75.4 | 65-100 | Y |

| 9 | G. M. Bernardes et al [42] | 2021 | Cohort study. |

Brazil |

1768 | 67.5 | 60-100 | Y |

| 10 | A. Bisquera et al [43] | 2021 | Retrospective cohort |

UK |

826936 | 42·4 | 18-80 | Y |

| 11 | E. Bustos-Vazquez et al [44] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study |

Mexico |

8874 | 60-100 | N | |

| 12 | J. Butterworth et al [45] | 2020 | Cluster randomized controlled feasibility trial |

N | ||||

| 13 | C. Caraballo et al [46] | 2022 | Cross-sectional |

USA | 596355 | 48.4 | 18-80 | Y |

| 14 | N. Carrilero et al [47] | 2020 | Cross-sectional |

Spain | 1189325 | 0-14 | N | |

| 15 | J. Charlton et al [48] | 2013 | Cohort study |

England. |

282887 | 55-100 | Y | |

| 16 | S. Chauhan et al [49] | 2022 | Cross-sectional |

India |

31 373 | 60-100 | N | |

| 17 | G. K. K. Chung et al[50] | 2021 | China | 3074 | 48.5 | 18-100 | Y | |

| 18 | S. A. Cooper et al [51] | 2015 | Cross-sectional analysis |

Scotland | 1424378 | 43.1 48.0 | 18-100 | Y |

| 19 | G. Corrao et al [52] | 2020 | A nationwide study | Italy | N | |||

| 20 | A. K. Costa et al [53] | 2020 | Cross-sectional |

Brazil |

23329 | 37.9 | 0-100 | Y |

| 21 | C. D. Costa et al [54] | 2018 | Cross-sectional |

Brazil |

1451 | 60-100 | Y | |

| 22 | F. Diderichsen et al [55] | 2021 | N | |||||

| 23 | D. A. González-Chica et al [56] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study |

Australian | 2912 | 48.9 | N | |

| 24 | R. M. Guimaraes et al [57] | 2020 | Cross-sectional |

Brazil | 60-100 | N | ||

| 25 | P. Halonen et al [58] | 2019 | Cross-sectional |

Finland | 2862 | 91 | 90-107 | Y |

| 26 | M. Hamiduzzaman et al [59] | 2021 | Qualitative study |

Bangladesh | 22 | 72 | N | |

| 27 | Riyadh Alshamsan et al [60] | 2011 | Cross-sectional study |

UK | 6690 | N | ||

| 28 | Rohini Mathur et al [61] | 2018 | Observational cohort study |

99648 | 25-85 | N | ||

| 29 | Stephanie L. Prady et al [62] | 2016 | Cross sectional |

UK | 2234 | 26.8 | N | |

| 30 | SARAH A. AFUWAPE et al [63] | 2006 | Retrospective cohort |

UK | 213 | 37 | N | |

| 31 | Emma Barron et al [64] | 2020 | Cross sectional |

UK | 61414470 | 40.9 | N | |

| 32 | Jayati Das-Munshi et al [65] | 2021 | Longitudinal study | England |

56770 | 63 | Y | |

| 33 | Kenneth A. Earle et al[64] | 2001 | Retrospective case note review |

UK | 45 | 66 | N | |

| 34 | Rebecca Pinto et al[65] | 2010 | Cross-sectional study |

England |

1090 | 46.8 | 16-74 | N |

| 35 | Linda Petronella Martina Maria Wijlaars et al [66] | 2018 | Cross-sectional study |

England |

763 199 | 10月24日 | N | |

| 36 | A. Head et al[67] | 2021 | Descriptive epidemiology |

England |

1.000.000 | 46 | N | |

| 37 | A. Head et al[68] | 2021 | Descriptive study |

England |

991 243 | 18-81 | Y | |

| 38 | M. A. Hussain et al[69] | 2015 | Cross-sectional study |

Indonesia |

9438 | 40-100 | Y | |

| 39 | Calypse B Agborsangaya et al [70] | 2012 | Cross-sectional survey | Canada |

5010 | 46.7 | 18-80 | Y |

| 40 | C. A. Jackson et al[71] | 2016 | Longitudinal Study |

Australian |

4896 | 49.5 | N | |

| 41 | A. G. Jantsch et al[72] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Brazil |

3092 | 41.3 | 24-69 | Y |

| 42 | N. Jerliu et al [73] | 2013 | Cross-sectional | Kosovo |

1890 | 73.4 | 65-100 | Y |

| 43 | M. C. Johnston et al [74] | 2019 | Prospective cohort study | Scotland |

12 150 | 48 | Y |

|

| 44 | S. V. Katikireddi et al [75] | 2017 | Cohort study |

Scotland |

12743 | N | ||

| 45 | T. Keller et al [76] | 2018 | Cohort study |

the Netherlands, , Sweden, Denmark, and German | 19 013 | N | ||

| 46 | A. R. Khanolkar et al[77] | 2021 | Cohort study |

3723 | N | |||

| 47 | G. Knies et al[78] | 2022 | Longitudinal, nationally representative study | UK | 28523 | 16-100 | Y | |

| 48 | R. Kunna et al [79] | 2017 | China and Ghana |

15864 | 18-100 | Y | ||

| 49 | R. N. Kuo et al [80] | 2013 | Longitudinal study |

Taiwan | 959990 | N | ||

| 50 | N. E. Lane et al [81] | 2015 | Retrospective cohort |

Canada | 1518939 | 75.5 | N | |

| 51 | K. D. Lawson et al [82] | 2013 | Cross-sectional |

Scotland | 7054 | N | ||

| 52 | J. Lu et al [83] | 2021 | Cross-sectional |

China | 7480 | 70.79 | 60-100 | Y |

| 53 | R. McQueenie et al [84] | 2019 | National retrospective |

Scotland |

824374 | N | ||

| 54 | S. W. Mercer et al [85] | 2018 | Secondary cross-sectional |

UK | 659 | 51.2 | 18-100 | Y |

| 55 | L. Mondor et al [86] | 2018 | Cross-sectional |

Canada |

113627 | 18-100 | Y | |

| 56 | C. R. Nielsen et al [87] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Austria, Germany, Sweden,Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Switzerland,Belgium, Czech Republic, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Estonia andIsrael |

63842 | 50-100 | Y | |

| 57 | M. Niksic et al [88] | 2021 | Cohort study |

Spain | 1259 | 68.4 | 18-100 | Y |

| 58 | B. P. Nunes et al [89] | 2020 | Cross-sectional |

Brazil | 9412 | 50-100 | Y | |

| 59 | Z. Or et al [90] | 2021 | The analysis is based on patient-level linked routine data sources onhealth care |

Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States |

56364 | 65-90 | N | |

| 60 | J. F. Orueta et al [91] | 2013 | Cross-sectional |

Basque Country |

452698 | N | ||

| 61 | B. Perera et al [92] | 2020 | Anecdotal analysis |

UK | N | |||

| 62 | S. Reilly et al [93] | 2015 | Retrospective cohort |

UK | 346 551 | N | ||

| 63 | B. Reis-Santos et al [94] | 2013 | Cross-sectional | Brazil |

39881 | 20-60 | Y | |

| 64 | G. Q. Romana et al [95] | 2020 | Cross-sectional,observational, epidemiological |

Portugal |

4911 | N | ||

| 65 | B. L. Ryan et al [96] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Canada |

13581191 | 39.6 | 0-105 | Y |

| 66 | L. Singer et al [97] | 2019 | Longitudinal Study |

England |

7,130( | 66(10.9) | 50-100 | N |

| 67 | A. Singh-Manoux et al [98] | 2018 | Cohort study |

UK | 8270 | 50.2 | N | |

| 68 | D. J. Smith et al [99] | 2013 | Cross sectional | UK |

1751841 | 54.5 | Y | |

| 69 | M. J. Smith et al [100] | 2021 | Multilevel cohort study |

England |

45414 | N | ||

| 70 | S. K. R. van Zon et al [101] | 2020 | Longitudinal cohort |

US | 10719 | 53.8 | 50-64 | Y |

| 71 | H. M. Vasiliadis et al [102] | 2021 | Longitudinal cohort |

Canada |

1570 | N | ||

| 72 | C. Violan et al [103] | 2014 | Cross-sectional |

Spain | 1356761 | 47.4 | 19-100 | Y |

| 73 | X. L. Xu et al [104] | 2018 | Cohort study |

Australia |

11914 | 47.7 | 45-50 | Y |

| 74 | Y. Zhao et al [105] | 2020 | Population-based, panel data analysis | China | 11 817 | 62 | 50-100 | Y |

| 75 | Z. Zhou et al [106] | 2021 | A two-stage cluster sampling method | China |

64, 395 | 60 | 5-98 | Y |

| 76 | Aarts et al [107] | 2012 | Cohort study |

Netherlands |

1184 | 55.4 | 24-81 | Y |

| 77 | Aarts et al [108] | 2011 | Cross-sectional |

Netherlands |

15188 | 70 | 55-90 | N |

| 78 | Aarts et al [109] | 2011 | Prospective study |

Netherlands |

1763 | 55.4 | 24-81 | Y |

| 79 | Abizanda et al [110] | 2014 | Cohort study |

Spain | 842 | 78.6 | 70-100 | N |

| 80 | Agborsangaya et al [111] | 2012 | Cross-sectional |

Canada |

4752 | 47.7 | 18-90 | Y |

| 81 | Agborsangaya et al [112] | 2013 | Cross-sectional |

Canada | 4946 | 46.6 | 18-85 | Y |

| 82 | Agborsangaya et al [113] | 2013 | Canada |

4752 | 47.7 | 18-100 | Y |

|

| 83 | Ahrenfeldt et al [114] | 2019 | Cohort Study |

Europe |

49946 | 66.25 | N | |

| 84 | Alimohammadian et al [115] | 2017 | Cohort Study | Iran |

49946 | 40-75 | Y | |

| 85 | Angst et al [116] | 2002 | Prospective cohort |

Switzerland |

591 | N | ||

| 86 | Linda Juel Ahrenfeldt et al [117] | 2019 | Cross-sectional |

Europe |

244258 | 66.25 | N | |

| 87 | Ayesha A Appa et al [118] | 2014 | Multiethnic cross-sectional cohort |

USA | 1997 | 60.2 | Y | |

| 88 | Mary L Adams et al [119] | 2017 | USA | 400000 | N | |||

| 89 | Thatiana Lameira Maciel Amaral 1 [120] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Brazil |

264 | 60-100 | Y | |

| 90 | Keun Ok An et al [121] | 2016 | Cross-sectional |

South Korea |

10118 | 54.8 | N | |

| 91 | Diane Arnold-Reed et al [122] | 2018 | Retrospective cohort study |

Australia |

4285 | 38.2 | 18-90 | Y |

| 92 | Perianayagam Arokiasamy et al [123] | 2015 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, South |

42236 | 18-100 | Y | ||

| 93 | Judith Sinnige et al [124] | 2015 | Netherlands |

120480 | 66.9 | 55-80 | Y | |

| 94 | Dawit T Zemedikun et al [125] | 2018 | Cluster analysis |

UK | 502643 | 58 | 40-69 | Y |

| 95 | Luke T A Mounce et al [126] | 2018 | Cohort | UK |

4564 | 50-100 | Y | |

| 96 | Anne W Taylor et al [127] | 2010 | logistic regression |

Australia |

3206 | 20-80 | Y | |

| 97 | Davy Vancampfort et al [128] | 2019 | Cross-sectional |

Multiple continents |

34129 | 62.4 | N | |

| 98 | Davy Vancampfort et al [129] | 2018 | Cross-sectional study |

Multiple continents |

14585 | 72.6 | 65-100 | Y |

| 99 | Carole E Aubert et al [130] | 2016 | Cross-sectional |

Switzerland |

1002 | 63.5 | 50-80 | Y |

| 100 | Christine S Autenrieth et al [131] | 2013 | Cross-sectional |

Germany |

1007 | 75.7 | 65-94 | Y |

| 101 | Caroline Bähler et al [132] | 2015 | Observational study | Switzerland |

229493 | 74.9 | 65-100 | Y |

| 102 | Davy Vancampfort et al [133] | 2017 | Cross-sectional |

44 low and middle income countries |

194431 | 38.3 | N | |

| 103 | Sarah Bernard et al [134] | 2016 | Prospective cohort |

Australia |

306 | 81.8 | 65-105 | Y |

| 104 | Tuhin Biswas et al [135] | 2019 | Cross-sectional |

Bangladesh |

8763 | 35-100 | N | |

| 105 | Amy Blakemore et al [136] | 2016 | Prospective cohort design |

UK | 4377 | 75 | N | |

| 106 | Bowling C B et al [137] | 2019 | Cross-sectional |

USA | 4217 | 56.7 | 50-64 | Y |

| 107 | Helena C Britt et al [138] | 2021 | Secondary analysis of data from a sub studyof the BEACH (Bettering the Evaluation AndCare of Health) |

Australia |

9156 | N | ||

| 108 | Paula Broeiro-Gonçalves et al [139] | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Portugal | 800376 | 59.8 | N | |

| 109 | Jako S Burgers et al [140] | 2010 | France, Germany, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, New Zealand,UK, USA | 8973 | N | |||

| 110 | Bianca M Buurman et al [141] | 2016 | Prospective cohort | The Netherlands | 639 | 78.2 | N | |

| 111 | Amaia Calderón-Larrañaga et al [142] | 2017 | Sweden | 3363 | 74.6 | N | ||

| 112 | Marco Canevelli et al [143] | 2020 | Italy | 185 | 75.1 | N | ||

| 113 | Alanna M. Chamberlain et al [144] | 2020 | USA | 198941 | N | |||

| 114 | He Chen et al [145] | 2018 | China | 30774 | N | |||

| 115 | Tsun-kit Chu et al [146] | 2018 | Retrospective cross-sectional study | China | 382 | N | ||

| 116 | Yogini V. Chudasama et al [139] | 2019 | Longitudinal study | UK |

491939 | 58 | 18-100 | Y |

| 117 | Cristina Cimarras-Otal et al [147] | 2014 | Cross-sectional | Spain | 22190 | N | ||

| 118 | Weng Yee Chin et al [148] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | China | 9259 | 48 | 18-100 | Y |

| 119 | Sutapa Agrawal et al [149] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | India, China, Russia, Mexico,South Africa, Ghana | 40166 | 57.8 | N | |

| 120 | Jane M Gunn et al [150] | 2012 | Cross-sectional | Australia | 6864 | 50.89 | 18-76 | Y |

| 121 | Han MA et al [151] | 2013 | Cross-sectional | USA | 159 | 76 | Y | |

| 122 | Peter Hanlon et al [152] | 2018 | Prospective, population-based cohort study | UK | 493737 | 37-73 | N | |

| 123 | Adelson Guaraci Jantsch et al [153] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 3092 | 42 | N | |

| 124 | D Jovic 1, J Marinkovic 2, D Vukovic 3 [154] | 2016 | Secondary data analysis | Serbia |

13103 | 49.4 | 20-100 | Y |

| 125 | Helle Gybel Juul-Larsen et al [155] | 2020 | Longitudinal prospective cohort | Denmark | 369 | N | ||

| 126 | Catherine Hudon et al [156] | 2008 | Secondary analysis | Canada | 16782 | N | ||

| 127 | Kenya Ie et al [157] | 2017 | A cross-sectional | USA | 1084 | N | ||

| 128 | Tatsuro Ishizaki et al [158] | 2019 | Japan |

2525 | 76.9 | 60-100 | Y | |

| 129 | Hendrik Dirk de Heer et al [159] | 2013 | A stratified, two-stage, randomized, cross-sectional health survey | Mexico | 1002 | 47.72 | 18-100 | Y |

| 130 | Anahit Demirchyan et al [160] | 2013 | Armenia | 721 | 58.8 | N | ||

| 131 | Elisa Fabbri et al [161] | 2015 | Cross-sectionally | Italy | 695 | 72.3 | 60-95 | Y |

| 132 | G G Fillenbaum et al [162] | 2000 | Longitudinalstudy | USA | 4034 | 73.44 | 64-100 | Y |

| 133 | Jihun Kang et al [163] | 2017 | Cross sectional | South Korea | 590 | 32.2 | 20-80 | Y |

| 134 | Christopher Harrison et al [164] | 2014 | Cross sectional | Australia | 8707 | 20-89 | Y | |

| 135 | Nusrat Khan et al [165] | 2019 | Cross sectional | Bangladesh |

12 338 | 58.6 (SD ±9.2) years | 35-100 | Y |

| 136 | Masuma Akter Khanam et al [166] | 2011 | Cross sectional | Bangladesh |

452 | 60-100 | Y | |

| 137 | Dana E King et al [167] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | USA |

57303 | 20-100 | Y | |

| 138 | Krupa Gandhi et al [168] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | USA | 9499 | 20-80 | Y | |

| 139 | Myles Gaulin et al [169] | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | Canada | 5 316 832 | 51.2 ± 17.93 | N | |

| 140 | Debora Rizzuto et al [170] | 2017 | Population-based cohort study. | Sweden | 1099 | 78-100 | Y | |

| 141 | Nafeesa N Dhalwani et al [171] | 2017 | Longitudinal Study | UK |

5476 | 61 | 50-100 | Y |

| 142 | Sophie Excoffier et al [172] | 2018 | Longitudinal Study | UK | 56.5 (20.5 | N | ||

| 143 | Martin Fortin et al [173] | 2014 | Cross sectional | Canada | 1196 | 57.8 | 45-80 | Y |

| 144 | Henrike Galenkamp et al [174] | 2011 | Longitudinal Study | The Netherlands | 2046 | 69.2 | N | |

| 145 | Lori M Gawron et al [175] | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | USA | 741612 | N | ||

| 146 | Rima R. Habib et al [176] | 2014 | Cross-sectional | Lebanon | 2501 | 46.6 | N | |

| 147 | Christopher Harrison et al [175] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Australia | 8707 | N | ||

| 148 | Samah Hayek et al [176] | 2017 | Australia | 8707 | N | |||

| 149 | Debra E Henninger et al [177] | 2012 | Cross-sectional | USA | 3212 | 76 | 68-100 | Y |

| 150 | Belinda Hernández et al [178] | 2019 | Ireland | 6101 | N | |||

| 151 | Cyrus Sh Ho et al [179] | 2014 | Cross-sectional and longitudinal | Singapore | 1844 | 66.15 | N | |

| 152 | Andrew Kingston et al [180] | 2018 | Dynamic microsimulation model | 9723900 | N | |||

| 153 | Ai Koyanagi et al [181] | 2018 | Cross-sectional, | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, andSouth Africa |

32715 | 62.1 | 50-100 | Y |

| 154 | Didi M W Kriegsman et al [182] | 2004 | Longitudinal design | Netherlands | 2489 | 69.2 | 55-85 | Y |

| 155 | Kaja Kristensen et al [183] | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Germany | 7604 | 64.37 | 40-80 | Y |

| 156 | Kaja Kristensen et al [184] | 2019 | Longitudinal | Germany | 19605 | 63.47 | 40-80 | Y |

| 157 | Francisco T T Lai et al [185] | 2019 | Sex-specific age-period-cohort analysis with repeated cross-sectional surveys. | Hong Kong (SAR of China | 69 636 | N | ||

| 158 | Francisco T T Lai et al [186] | 2019 | Prospective | Hong Kong (SAR of China |

300 | 18-77 | Y | |

| 159 | P A Laires, J Perelman [187] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Portugal |

15196 | 25-79 | Y | |

| 160 | Kathleen Lang et al [188] | 2015 | Cross-sectional, | USA | 3058 | 53.4 | 40-64 | Y |

| 161 | C Le Cossec et al [189] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | France | 15325 | 70 | N | |

| 162 | Todd A Lee et al [190] | 2007 | Cohort study | USA | 741847 | N | ||

| 163 | Wei-Ju Lee et al [191] | 2018 | Taiwan |

20898 | 65-100 | Y | ||

| 164 | Sanja Lujic et al [192] | 2017 | cohort study | Australia | 90352 | 70.2 | 45-80 | Y |

| 165 | Francisco Lupiáñez-Villanueva et al [193] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 14 European countries | 14000 | N |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).