1. Introduction

Hydrogels can be used as artificial extracellular matrices in tissue engineering in development of scaffolds for biomimetic three-dimensional cell culture. The importance and challenges of design and development of hydrogels that mimic the mechanical and biological properties of the native extracellular matrix has been reviewed [

1,

2].

The design of hydrogels with tunable physiochemical and biological properties and their potential applications in regenerative medicine were discussed by researchers from Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2014 [

3].

The function and properties of hydrogels containing matrix-like molecules, hydrogels containing decellularized matrix, hydrogels derived from decellularized matrix, and decellularized tissues as reimplantable matrix hydrogels also have been discussed [

4].

Poor mechanical strength is mentioned as one of the major limitations mainly in application for tissue engineering [

5]. The attempts to improve mechanical properties can lead to the risks of age-related diseases initiation as a result of tissue stiffening. The aim is to attract attention to not yet published potential risks of extracellular matrix stiffening by entrapped rigid particles leading to initiation and accelerated progress of cancers, cardiovascular and some other age-related diseases The risks of initiation and progress of severe age-related diseases associated with incorporation into ECM rigid particles with related increase of elasticity modulus can be suggested to be taken into consideration.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Cardiac tissue engineering

Application of hydrogels in repair and regeneration of damaged hearts has been discussed [

6,

7,

8].

Researchers at University of Colorado Boulder discussed three-dimensional encapsulation of adult mouse cardiomyocytes in hydrogels with tunable stiffness [

6]. Morphology and function of cardiomyocytes depends on the mechanical properties of their microenvironment. The authors used photo-clickable thiol-ene poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels for three-dimensional cell culture of adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Stiffness of PEG hydrogels can be tuned to mimic microenvironments of cells and cells function is dependent on the PEG hydrogel stiffness.

Injectable conductive carbon and metal-based nanocomposite hydrogels for cardiac tissue engineering has been reviewed [

8]. It would be beneficial in the nearest future to study in more detail and quantatively the role and impact of nanoparticles rigidity, especially in mechanical moduli improvement, in cardiac tissue engineering.

UV-crosslinkable gold nanorod (GNR)-incorporated gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hybrid conductive hydrogels were investigated by researchers at Arizona State University for engineering cardiac tissue constructs [

9]. Cardiac patches with superior electrical and mechanical properties have been suggested to be developed using nanoengineered GelMA-GNR hybrid hydrogels.

Applications of photopolymerized hydrogels in tissue engineering also has been reviewed [

10].

Although already in 1997 it was reported that fibroblasts and epithelial cells on flexible substrates showed reduced spreading compared with cells on rigid substrates [

11] the recently published review [

12] stated that cell-matrix interaction “remains in its infancy, and the detailed molecular mechanisms are still elusive regarding scaffold-modulated tissue regeneration”. Injectable biodegradable hydrogels composed of gelatin-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid conjugate with tunable mechanical stiffness for the stimulation of neurogenesic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in 3D culture have been described and it was observed that the rate of human mesenchymal stem cells proliferation increased with decreasing the hydrogel stiffness. Modulation of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis in a tunable hyaluronic acid hydrogel microenvironment was reported [

13]. Silk hydrogels with variable stiffness and growth factor have been reported in study of human mesenchymal stem cells cultures [

14].

At first it was discovered that cellular processes depend on the substrate stiffness. But it was also concluded that cell mechanosensing is regulated by substrate strain energy rather than stiffness [

15]. It was demonstrated that hydrogels can properly mimic extracellular matrix (ECM) [

16].

2.2. Multi-layer polyelectrolyte complex hydrogels and bioprinting

Multi-layered hydrogels prepared using layer-by-layer self-assembly can be used for biomedical applications [

17].

3D printing of hydrogels, design and emerging biomedical applications has been presented in very detailed review [

18]. Laser printing (stereolithography, two-photon polymerization), extrusion printing (3D plotting, direct ink writing), inkjet printing, 3D bioprinting, 4D printing and 4D bioprinting have been mentioned in this review. Hydrogel-forming polymers that have been described include biopolymers, synthetic polymers, polymer blends, nanocomposites, functional polymers, and cell-laden systems. Biomedical applications in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, cancer research,

in vitro disease modeling, high-throughput drug screening, and surgical preparation have been discussed.

Three-dimensional (3D) printing of hydrogel composite systems such as particle-reinforced hydrogel composites, fiber-reinforced hydrogel composites, and anisotropic filler-reinforced hydrogel composites have been reviewed [

19]. It would be beneficial to explain in more detail the role of fillers in above mentioned hydrogel composites.

2.3. Residual internal stresses

The residual tensile and compressive stresses arise near filler particles in polymer composites [

20]. Due to mechanotransduction such mechanical stresses arise similarly in ECM and can be transmitted onto cytoskeleton tension with the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway and changing gene expression. The presence of soft component at small concentrations in rigid matrix resulted in development of compressive stress due to difference in thermal expansion coefficients and lead to maximum on the dependence of elasticity modulus on filler concentration. Temperature changes result in changes of residual stresses values and reinforcement values. The migration of low molecular weight molecules with higher thermal expansion coefficient to interfaces can increase ECM stiffness due to the development of compressive residual stresses.

The stresses and properties of composite gel consisting of poly(vinyl alcohol (PVA) matrix filled with poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) microgel particles have been reported [

21]. The swelling of the PAA particles was limited by the tensile stress developing in the PVA matrix. The maximum tensile stress was found to increase with the stiffness of the PVA matrix, and to decrease with increasing crosslink density of the PAA.

It can be suggested that stresses in ECM due to mechanotransduction can be translocated to cells and make changes in important cellular processes.

Cells respond to mechanical microenvironment cues via Rho signaling [

22]. Rho GTPase is closely related to tumorigenesis, invasion and metastasis. Rho subfamily is involved in the formation of tensile fibers and focal adhesion complexes (FACs). Rho signaling pathway plays an important role in the development of cancer, and it is also expected to treat cancer by developing inhibitors of the Rho signaling pathway [

23].

2.4. Viscoelastic hydrogels

The group of authors from Stanford University, Harvard University, The University of Queensland, and University of Pennsylvania discussed the effect of ECM viscoelasticity in hydrogels on cellular behavior [

24].

Viscoelastic hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation have been developed, and stress relaxation has been shown to regulate cell differentiation, spreading, and proliferation [

25]. Faster relaxation in alginate-PEG hydrogels was associated with increased spreading and proliferation of fibroblasts, and enhanced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). It can be taken into consideration that stress relaxation is related with the residual stresses [

20].

It has been reported that stress relaxation of semi-flexible chain segments in hydrogels from the polyelectrolyte complexation of sodium hyaluronate (HA) and chitosan increases with increasing temperature and salt concentration [

26].

The stiffness of multilayer stent nanocoatings depends on their hydration degree and plays important role in prevention of protein adsorption and platelet adhesion [

27].

2.5. Hydrogel nanocomposites

It has been reported in article published by researchers from University of Cambridge that hydrogels resemble the ECM and can support cell proliferation when they are used as tissue engineering scaffolds and that nanofibers improve both mechanical properties and biofunctionality of hydrogels [

28].

But it is still must be taken into consideration that nanofibers localized in ECM can increase viscosity and stiffness due to the presence of rigid surfaces at interfaces of heterogeneous matrix and initiate through mechanotransduction harmful processes in cells related with initiation of severe age-related diseases. So the functionality improvement must be confirmed in additional studies.

For example, recently a novel organic-mineral nanofiber/hydrogel of chitosan-polyethylene oxide (CS-PEO)/nanoclay-alginate (NC-ALG) was prepared and effects of nanoclay particles on the mineralization and biocompatibility of the scaffold were investigated and authors concluded that CS-PEO/ALG scaffolds is suitable for bone tissue regeneration because it enhances bone-like apatite formation [

29]. But the potential influence of nanoclay particles on signaling pathways and gene expression due to stiffness increase has not been discussed in detail though it can be expected that particles incorporated in ECM play essential role in regulation of cellular processes especially in soft tissues.

The interaction between ECM and nanoparticles has been discussed [

30].

Extracellular matrix stiffness regulates the induction of malignant phenotypes in mammary epithelium. Reserchers at Stanford University confirmed that cells sense the stiffness of their surrounding ECM by Rho-mediated contraction of the actin-myosin cytoskeleton [

31].

A stiffness-tunable graphene oxide/polyacrylamide composite scaffold was fabricated to investigate the effect of substrate stiffness on cytoskeleton assembly and specific gene expression during cell growth by researchers at Tsinghua University, China [

32]. Cells sense ECM and translate mechanical stresses into biochemical signals activating diverse signaling pathways or changing intracellular calcium concentration. The cellular functions such as migration, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis are modulated by mechanotransduction. It was suggested that defects in mechanotransduction are able to cause diverse diseases including cancer progression and metastasis [

33]. Not only mechanotransduction defects but a number of other causes such as increased tissue stiffness, increased crosslinking by glycation end products, increased collagen content, dehydration, release of bound water molecules can initiate cancer and a number of age-relate diseases.

2.6. Effect of water

Dehydration and glycation, crosslinking, redistribution of bound water molecules, entropy driven release of tightly bound water molecules are the processes leading to ECM stiffening [

27,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Enhanced mobility of intracellular water for cancer cells vs non-malignant cells using quasi-elastic neutron scattering (QENS) was reported [

39]. So the binding energy of water molecules to biomacromolecules decreases in cancer cells and it is possible to suggest that decrease of binding energy results in transformation of healthy cell into cancer cell. The role of water binding energy in initiation of various diseases was reviewed [

35,

36,

37].

Water response to the anticancer drug cisplatin was investigated using neutron scattering spectroscopy performed at the ISIS Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source of the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the low-energy OSIRIS high-flux indirect-geometry time-of-flight spectrometer and intracellular water mobility reduction was observed [

40]. So it can be suggested that application of cisplatin increases water binding energy.

It has been concluded that normal-to-malignant transformation is a poorly understood process associated with and dependent on the dynamical behavior of water, two different water populations have been considered: “one displaying bulk-like dynamics (extracellular and intracellular/cytoplasmic) and another with constrained flexibility (extracellular/interstitial and intracellular/hydration layers)” [

41].

It has been shown in vivo that at low magnetic fields tumor cells display much longer proton T

1 values compared with the values shown by healthy cells and it has been found that the elongation of T

1 can be associated with the tumor aggressiveness [

42]. Elongation of T

1 can be related with transformation of tightly bound water into slightly bound water. So it can be suggested that release of tightly bound water can increase the risk of cancer initiation.

It was shown that not only bulk but also nanoscale properties of collagen fibrils play a significant role in determining cell phenotype. Collagen fibrils can be dehydrated, and smooth muscle cells spread and proliferate extensively when seeded on these dehydrated fibrils, which are mechanically stiffer if compared with fully hydrated fibrils. The authors suggested that nanoscale rigidity of collagen fibrils can cause these cells to assume a proliferative phenotype [

43].

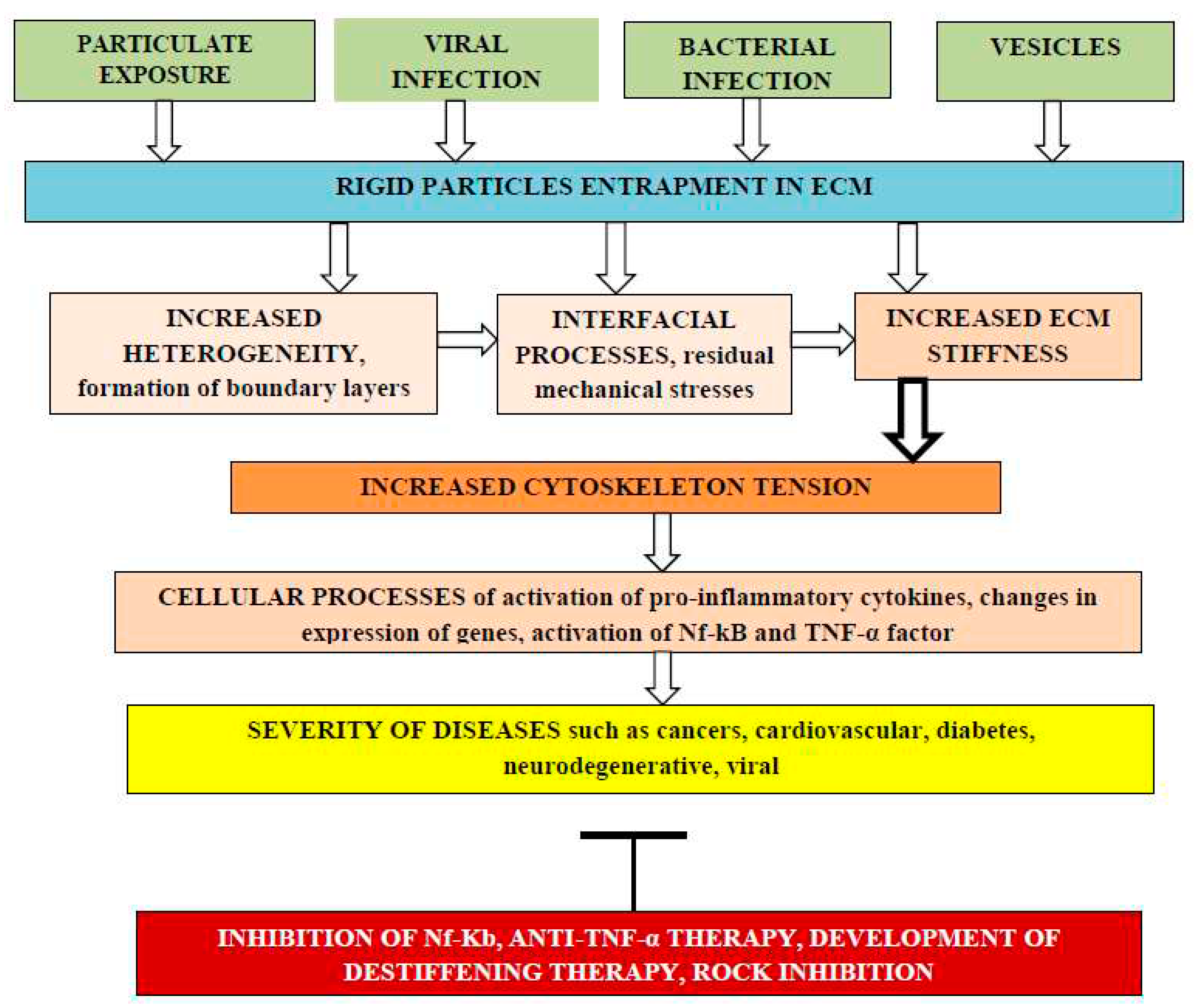

2.7. ECM stiffness and cancer

Cellular biochemical processes depend on ECM mechanical stiffness. Entrapment of rigid particles can enhance ECM stiffness due to interfacial changes near rigid surfaces and cause various diseases including initiation and progress of different cancers,

Figure 1.

Cancer development and progression can be associated with remodeling of the ECM. Layer-by-layer coating terminated by hyaluronic acid on calcium carbonate nanoparticles can be applied for targeting breast cancer cells. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is known as a ligand of tumor-associated receptor CD44 [

44]. The coating slows down release of the encapsulated model drug. The authors concluded that future studies should focus on understanding the role of different HA receptors in nanoparticles accumulation in the extracellular matrix.

Cells are regulating the structure and performance of ECM, for example cells secret biomolecules that diffuse in the ECM creating temporally and spatially controlled gradients which play important role in inflammation and cancer [

45]. HA is a main component of the ECM. In breast cancer accumulation of low molecular weight HA and formation of local gradients plays an important role in cancer development. Cellular response to gradients of HA oligomers can improve the understanding of HA-associated carcinogenesis. The soluble low molecular weight HA promotes the directional migration of cells. HA is partially immobilized by interactions with ECM components. Hydrogel HA gradients have been developed to screen the cell behavior. HA gradients were developed by a two-step procedure: i) diffusional deposition of colloidal gold nanoparticles to obtain a gradient and ii) immobilization of end-on-thiolated hyaluronan on this gradient. The gradient in HA content is concomitant with alterations in hydrogel mechanical properties, and it is not at present clear whether the cell response is triggered by HA-activated signaling pathways or mechanosensing. HA gradients by surface immobilization of end-on thiolated HA (4.8 kDa) on gold gradients formed via diffusional deposition of colloidal nanoparticles has been reported [

46].

The hydrogels with various stiffness have been designed and influence on the morphology of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their differentiation has been studied [

47]. Artificial ECM for applications of tumorigenesis research has been reviewed [

48].

It has been shown that time-dependent stiffness of methacrylated hyaluronic acid hydrogels can be dynamically modulated from “normal” (<150 Pascals) to “malignant” (>3,000 Pascals) during investigation of cultured mammary epithelial cells (MECs) in order to mimic and understand breast cancer development [

49]. It has been found that MECs begin to lose epithelial characteristics and gain mesenchymal morphology upon matrix stiffening.

It has been reported in 2022 that 3D bioprinted GelMA-nanoclay hydrogels induce colorectal cancer stem cells through activating wnt/beta-catenin signaling [

50] and that extracellular matrix stiffness dictates Wnt expression through integrin pathway [

51] in 2016 by researchers at Tsinghua University and Lanzhou University, China jointly with University of California at San Diego, USA. The joint analysis of both articles allows coming to conclusion that nanoclay particles increase ECM stiffness resulting in wnt/beta-catenin signaling activation and induce colorectal cancer stem cells. So ECM destiffening could be beneficial input into fighting various cancers.

Researchers at University of Illinois, Chicago, USA investigated the culture of epithelial ovarian cancer cells on three-dimensional collagen I gels and in 2013 reported that matrix rigidity activates Wnt signaling through down-regulation of Wnt signaling inhibitor dickkopf-1 protein. Inverse relationship between dickkopf-1 and membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase was observed in human epithelial ovarian cancer specimens [

52].

Inhibition of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in colon cancer cells by the most active vitamin D metabolite, 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) has been reported. It has been suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 distinctly regulates two genes encoding the extracellular Wnt inhibitors DICKKOPF-1 (DKK-1) and DICKKOPF-4 (DKK-4). 1,25(OH)2D3 increases the expression of DKK-1 which acts as a tumor suppressor in human colon cancer cells and represses DKK-4 transcription up-regulated in colorectal tumors increasing cell migration and invasion [

53,

54].

Wnt signaling in brain tumors has been analyzed in the recent review [

55].

3D hydrogel breast cancer models have been described for studying the effects of hypoxia on epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Hypoxia enhanced breast cancer cell migration, and expression of lysyl oxidase (LOX), which drives the crosslinking of collagen and elastin [

56].

The advantages of 3D hydrogel cancer models and drawbacks of 2D cancer models have been described [

56]. In 2D models cells adhere to a flat surface with only a part of the cells’ surface in direct contact with substrate and lack intercellular contacts. Cells grown on the 2D stiff surface compared with cells localized in 3D environment demonstrate different response to biophysical cues, exhibit different cytokine secretion capacity and cell response to anti-cancer drugs [

57,

58]. It was demonstrated that MCF-7 cancer cells cultured in the 3D model had reduced sensitivity to doxorubicin in comparison with cells cultured in 2D condition [

58]. IL-8 expression was increased in human oral squamous cell carcinoma in 3D environments but not in 2D monolayers [

59].

Increased ECM stiffness promotes nuclear localization of YAP and TAZ and upregulation of their target genes ([

60]. YAP/TAZ is essential for cancer initiation or growth [

61].

2.7.2. Polyphenols decrease ECM stiffness

The effect of polyphenols on microbiome has been reviewed [

62]. Polyphenols can inhibit NF-κB and TNF-α, which lead to the increase of tissue stiffness and permeability [

63]. At least one aromatic ring with a hydroxyl group attached to it was mentioned as a common feature for polyphenols [

64]. The polymers with such chemical structure can be also recommended to be used as matrix plasticizers.

The beneficial health effect of polyphenols can be explained by their potential destiffening of ECM due to plasticizing effect that has been earlier demonstrated on edible polymer films [

65]. Essential decrease of Young’s modulus was reported when gallic acid, p-hydroxy benzoic acid, and ferulic acid have been used as plasticizers, but the lack of any considerable plasticizing effect for flavon was observed.

The antiplasticizing effect of tannic acid incorporated into films from sorghum kafirin was observed with reduced elongation, but increased tensile strength and Young’s modulus. The antiplasticizing effect could be due to increased number of hydroxyl groups tightly binding within the matrix [

66].

The films containing phenolic compounds have also antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.

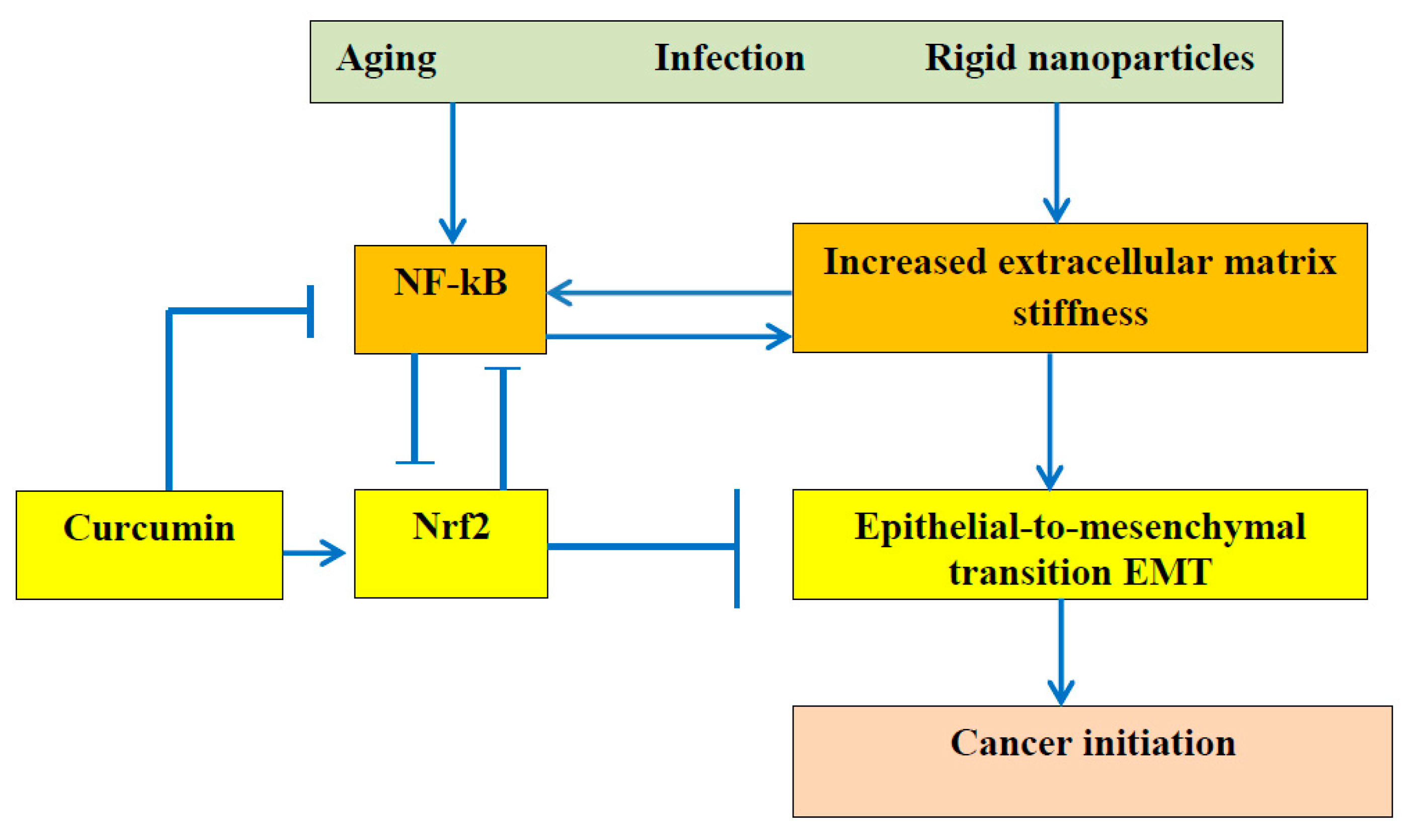

Curcumin upregulates Nrf2 nuclear translocation [

67,

68]. Activation of Nrf2 by curcumin can inhibit activation of tissue stiffness, inflammatory cytokines expression, and NF-kB pathway [

69,

70].

Dietary polyphenols can decrease arterial stiffness [

62] and it was reported that curcumin downregulates the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 [

71]. So the joint consideration of those two articles allows arriving to the conclusion that ECM destiffening downregulates expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and it has been recently reported that matrix stiffness exacerbates the pro-inflammatory responses of vascular smooth muscle cell [

72].

Resveratrol and quercetin inhibit NF-kB pathway [

64]. The beneficial role of Nrf2 in cancer treatment has been reported [

69,

73,

74,

75].

It has been reported that Nrf2 downregulation contributes to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in

Helicobacter pylori-infected cells [

76]. The authors believe that obtained “results could pave the way for new therapeutic strategies using Nrf2 modulators to reduce gastric carcinogenesis associated with

H. pylori infection”.

Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with oxidative stress. It is important to take into consideration that infection leads to an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) resulting in gastric carcinogenesis.

The relationship between the ECM stiffness and EMT is presented in

Figure 2.

It can be suggested that any infection particles entrapped into ECM could initiate EMT and cancer as a result of changes of ECM stiffness. Commonly the decrease of Nrf2 with increased oxidative stress can be associated with activation of NF-kB pathway with enhanced inflammation [

38].

It was found that infected tissues are softer than uninfected ones and has been explained at least partially by cell cytoskeleton remodeling [

77]. Researchers from Medical University of Bialystok consider that the “molecular mechanism of gastric cancer development related to

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection has not been fully understood, and further studies are still needed”.

2.7.3. Chitosan and chitosan oligosaccharides

Injectable

in situ chitosan hydrogels in cancer treatment have been reviewed [

78]. It is generally believed that cancers may result from the interaction between healthy cells and carcinogens such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation; chemical carcinogens such as asbestos and tobacco smoke; biological carcinogens such as infections by virus and contamination of food by mycotoxins. The authors considered that external agents cause genetic alterations resulting in mutations, and thereby perturbing normal cell function. But the effect of above mentioned agents on ECM must also be taken into consideration.

Chitosan-based hydrogels possess the required good biocompatibility, mucosal adhesion, and hemostatic activity with potential for application in tissue engineering and drug delivery [

79]. The fact that extracellular pH values in tumors are lower than in healthy tissues (pH = 7.4) [

80] can be used in drug delivery systems. Injectable chitosan-chondroitin sulfate hydrogel embedding kartogenin loaded microspheres as an ultrasound-triggered drug delivery system for cartilage tissue engineering has been designed and fabricated. It was observed that the hydrogel/microspheres’ compressive elastic modulus was greatly enhanced, which is in author’ opinion good for cartilage healing [

81]. Though it would be beneficial to take into consideration the potential increased risks of inflammation and oxidative stress. Stiff ECM increases intracellular reactive oxygen species and activates oxidative stress.

2.7.4. Anti-TNF-α and anti-NF-κB therapies’

Anti-TNF-α therapy decreases ECM stiffness and can be used in the treatment of age-related diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [

38,

63,

82]. The nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway is involved in inflammation through the regulation of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules expression. A number of anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic drugs, such as glucocorticoids, aspirin, sodium salicylate, sulfosalazine, and gold compounds, have been mentioned as inhibitors of NF-κB activation [

83]. Nutrients such as Omega 3 and Vitamin D, can decrease NF-kB activation [

84].

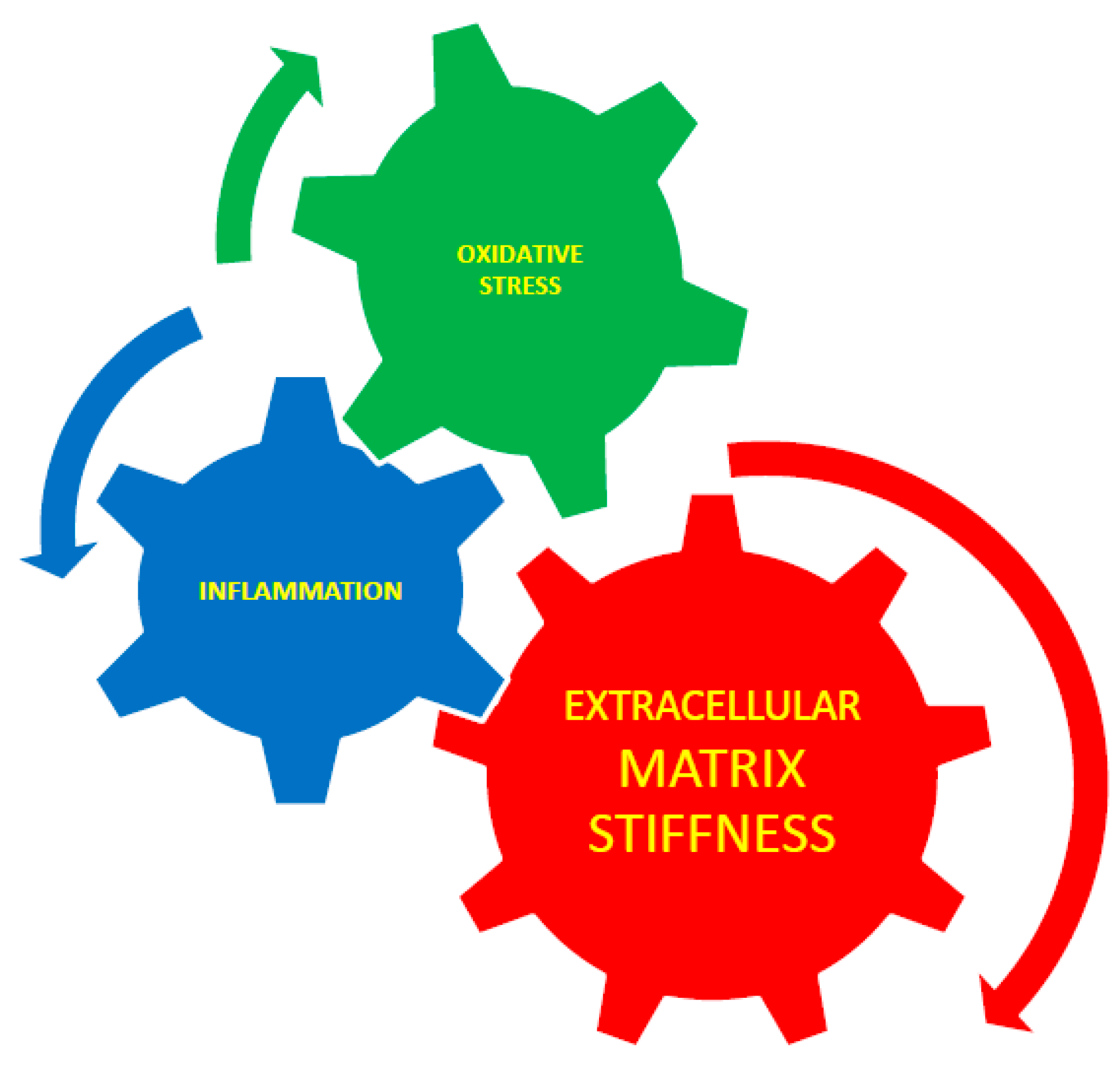

2.8. Equivalence of ECM stiffness, oxidative stress, and inflammation

NF-kB is identified as one of the main inflammatory pathways.

Human dermal fibroblasts seeded on soft matrix demonstrated high oxidative stress resistance, due to high expression of Nrf2 [

85].

It has been reported that oxidative stress initiates arterial stiffness [

86] and that stiffness can initiate oxidative stress [

87]. So it can be suggested that oxidative stress and tissue stiffening do not relate to two processes separately but to the two different aspects of the united process measured using different methods. Interaction between extracellular matrix stiffness, inflammation, and oxidative stress is presented schematically at

Figure 3. As a third aspect an inflammation can be joined to such united process because it was suggested that oxidative stress, arterial stiffness jointly lead to the development of diabetes.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) decrease arterial stiffness [

88]. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in inhibition of arterial stiffness was discussed. Excessive stimulation of angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptors leads to oxidative stress and vascular inflammation. RAAS inhibition decreases arterial stiffness [

89]. The effects of two RAAS inhibitors (quinapril and aliskiren) and 2 beta-blockers (atenolol and nebivolol) on arterial stiffness, measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV), have been reported [

90]. PWV were decreased by all agents after 2 weeks, and continued to decrease till 10 weeks in patients on quinapril, aliskiren, and nebivolol but did not change in patients taking atenolol. Angiotensin receptor blockades (ARBs) reduce arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV) [

91].

3. Conclusions and future perspective

Nanoclay particles increase ECM stiffness resulting in wnt/beta-catenin signaling activation and induce colorectal cancer stem cells.

Wnt signaling-targeting drugs are still not clinically available. Additional efforts will be needed to demonstrate the real clinical impact of Wnt inhibition in various tumors.

The function and effect of particulate and fiber fillers in particle-reinforced hydrogel composites, fiber-reinforced hydrogel composites, and anisotropic filler-reinforced hydrogel composites can be investigated in more detail in the nearest future.

Accumulation of rigid particles, such as nanofillers for polymer composites, particulate matter from air pollution, exosomes, viruses, bacteria and other increases ECM stiffness and initiates related diseases.

The risks related with ECM increased stiffness as a result of rigid nanoparticles incorporation must be studied in more detail.

Vitamins that have an antioxidant function, such as vitamin A, C and E are expected also to decrease ECM stiffness.

Heterogeneous structure of ECM leads to the development of the internal residual stresses in ECM.

The relationship between external mechanical stresses and internal cellular stresses and mechanism of mechanical stresses transmission from ECM to cells is still elusive.

The role of various water populations in normal and malignant tissue must be further investigated using modern physical methods.

The essential advancement from mechanobiology to mechanomedicine can be expected in the nearest future. The links, correlations, and interaction between inflammation, oxidative stress and tissue stiffness must be further investigated in detail.

References

- Peppas, N.A.; Hilt, J.Z.; Khademhosseini, A.; Langer, R. Hydrogels in biology and medicine: From molecular principles to bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaharwar, A.K.; Peppas, N.A.; Khademhosseini, A. Nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014, 111, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annabi, N.; Tamayol, A.; Uquillas, J.A.; Akbari, M.; Bertassoni, L.E.; Cha, C.; Camci-Unal, G.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Peppas, N.A.; Khademhosseini, A. 25th anniversary article: Rational design and applications of hydrogels in regenerative medicine. Adv Mater 2014, 26, 85–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbari, E.; Leijten, J.; Xu, Q.; Khademhosseini, A. The matrix reloaded:The evolution of regenerative hydrogels. Materials Today, 2016, 19, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F. ; Zhao, X-J. ; Jia, S-R.; Bai, H.; Zhong, C. Nanocomposite hydrogels as multifunctional systems for biomedical applications: Current state and perspectives, Composites Part B: Engineering, 2020, 200, 108208. [Google Scholar]

- Camci-Unal, G.; Annabi, N.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Liao, R.; Khademhosseini, A. Hydrogels for cardiac tissue engineering. NPG Asia Materials, 2014, 6, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocini, C.; Walker, C.J; Anseth, K. S.; Leinwand,L.A. Three-dimensional encapsulation of adult mouse cardiomyocytes in hydrogels with tunable stiffness, Progr Biophys Mol Biol, 2020, 154, 71–79.

- Pournemati, B.; Tabesh, H.; Jenabi, A.; Aghdam, R.M.; Rezayan, A.H.; Poorkhalil, A.; Tafti, S.H.A.; Mottaghy, K. Injectable conductive nanocomposite hydrogels for cardiac tissue engineering: Focusing on carbon and metal-based nanostructures. Eur. Polym. J., 2022, 174, 111336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaei, A.; Saini, H.; Christenson, W.; Sullivan, R.T.; Ros, R.; Nikkhah, M. Gold nanorod-incorporated gelatin-based conductive hydrogels for engineering cardiac tissue constructs. Acta Biomaterialia 2016, 41, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; West, J.L. Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials, 2002, 23, 4307–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelham Jr, R. J.; Wang, Y. L. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. PNAS, 1997, 94, 13661–13665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, B.; Xu, Q.; Liu, W. An overview of substrate stiffness guided cellular response and its applications in tissue regeneration. Bioactive Materials 2022, 15, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, W.S.; Lim, T.C.; Kurisawa, M.; Spector, M. Modulation of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis in a tunable hyaluronic acid hydrogel microenvironment. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3835–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floren, M.; Bonani, W.; Dharmarajan, A.; Motta, A. , Migliaresi, C.; Tan, W. Human mesenchymal stem cells cultured on silk hydrogels with variable stiffness and growth factor differentiate into mature smooth muscle cell phenotype. Acta Biomaterialia, 2016, 31, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzetta, V.; Fusco, S.; Netti, P.A. Cell mechanosensing is regulated by substrate strain energy rather than stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 22004–22013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbitt, M.W.; Kristi, S. Anseth, K.S. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 103, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ding, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Xie, H.; Gu, Z. Multi-layered hydrogels for biomedical applications. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- inhua Li, Chengtie Wu, Paul K. Chu, Michael Gelinsky, 3D printing of hydrogels: Rational design strategies and emerging biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng: R: Reports 2020, 140, 100543.

- Jang, T.-S.; Jung, H.-D.; Pan, H.M.; Han, W.T.; Chen, S.; Song, J. 3D printing of hydrogel composite systems: Recent advances in technology for tissue engineering. Int J Bioprint 2018, 4, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerch, G. M.; Irgen, L. A. Stiffness of composites based on polypropylene and low-density polyethylene. Mech Comp Mater 1989, 25, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horkay, F.; Bassera, P.J. Hydrogel composite mimics biological tissues. Soft Matter, 2022, 18, 4414–4426. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, N.; Xiao, C.; Shu, Q.; Cheng, B.; Wang, Z.; Xue, R.; Wen, Z.; Wang, J.; Shi, H.; Fan, D.; Liu, N.; Xu, F. Cell response to mechanical microenvironment cues via Rho signaling: From mechanobiology to mechanomedicine. Acta Biomater. 2023, 159, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y. Approaches of targeting Rho GTPases in cancer drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 991–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, O.; Cooper-White, J.; Janmey, P.A.; Mooney, D.J.; Shenoy, V.B. Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature 2020, 584, 535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S.; Stowers, R.; Lou, J.; Xia, Y.; Chaudhuri, O. Varying PEG density to control stress relaxation in alginate-PEG hydrogels for 3D cell culture studies. Biomaterials 2019, 200, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Jin, X.; Jiang, C.; Yin, P.; Tang, L.; Sun, T. Dynamic behavior of tough polyelectrolyte complex hydrogels from chitosan and sodium hyaluronate, Carbohydr. Polym, 2022, 288, 119403. [Google Scholar]

- Kerch, G.; Chausson, M.; Gautier, S.; Meri, R. M.; Zicans, J.; Jakobsons, E.; Joner, M. Heparin-like polyelectrolyte multilayer coatings based on fungal sulfated chitosan decrease platelet adhesion due to the increased hydration and reduced stiffness. Biomater. Tissue Technol, 2017, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, A.L.; Offeddu, G.S.; Oyen, M.L. Nanofibrous hydrogel composites as mechanically robust tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends in Biotechnology 2014, 32, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hakimi, F.; Jafari, H.; Hashemikia, S.; Shabani, S.; Ramazani, A. Chitosan-polyethylene oxide/clay-alginate nanofiber hydrogel scaffold for bone tissue engineering: Preparation, physical characterization, and biomimetic mineralization. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 233, 123453. [Google Scholar]

- Engin, A.B.; Nikitovic, D.; Neagu, M.; Henrich-Noack, P.; Docea, A.O.; Shtilman, M.I.; Golokhvast, K.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Mechanistic understanding of nanoparticles’ interactions with extracellular matrix: the cell and immune system. Part Fibre Toxicol 2017, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, O.; Koshy, S.T.; Branco da Cunha, C.; Shin, J.-W.; Verbeke, C.; Allison, K.H.; Mooney, D.J. Extracellular matrix stiffness and composition jointly regulate the induction of malignant phenotypes in mammary epithelium. Nat Mater. 2014, 13, 970–978. [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, K.; Deng, R.; Ren, X.; Wu, C.; Li, J. Tunable stiffness of graphene oxide/polyacrylamide composite scaffolds regulates cytoskeleton assembly. Chem Sci. 2018, 9, 6516–6522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaalouk, D.E.; Lammerding, J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kerch, G.; Glonin, A.; Zicans, J.; Meri, R.M. A DSC study of the effect of bread making methods on bound water content and redistribution in chitosan enriched bread. J Therm Anal Calorim 2012, 108, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerch, G. Distribution of tightly and loosely bound water in biological macromolecules and age-related diseases. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 118 Pt A, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerch, G. Polymer hydration and stiffness at biointerfaces and related cellular processes. Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kerch, G. Role of changes in state of bound water and tissue stiffness in development of age-related diseases. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerch, G. Tissue integrity and COVID-19. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.P.M.; Batista de Carvalho, A.L.M.; Mamede, A.P.; Dopplapudi, A.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E. Role of intracellular water in the normal-to-cancer transition in human cells-insights from quasi-elastic neutron scattering. Struct Dyn. 2020, 7, 054701. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, M.P.; Batista de Carvalho, A.L.; Sakai, V.G.; Hatter, L.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A. Intracellular water - an overlooked drug target? Cisplatin impact in cancer cells probed by neutrons. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2017, 19, 2702–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, M. P. M.; Santos, I. P.; Batista de Carvalho, A. L. M.; Mamede, A. P.; Martins, C. B.; Figueiredo, P.; Sarter, M.; García Sakai, V.; Batista de Carvalho, L. A. E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2022, 24, 15406–15415. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, M.R.; Baroni, S.; Pezzana, S.; Ferrante, G.; Geninatti Crich, S.; Aime, S. Evidence for the role of intracellular water lifetime as a tumour biomarker obtained by in vivo field-cycling relaxometry. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018, 57, 7468–7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, D.P.; Shaw, G.A.; Elliott, J.T.; Bhadriraju, K.; Meuse, C.; Chung, K.-H.; Plant, A.L. The stiffness of collagen fibrils influences vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, F.R; da Costa, D.S.; Reis, R.L.; Alves, N.M.; Pashkuleva, I.; Costa, R.R. Layer-by-layer coated calcium carbonate nanoparticles for targeting breast cancer cells. Biomater Adv. 2023, 153, 213563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan,T. M.; Folch, A. Biomolecular gradients in cell culture systems. Lab. Chip, 2008, 8, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.M.; da Costa, D.S.; Reis, R.L.; Pashkuleva, I. Influence of hyaluronan density on the behavior of breast cancer cells with different CD44 expression. Adv. Healthc. Mater., 2022, 11, e2101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Tan, B.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y. Jinfeng Liao. A review on the design of hydrogels with different stiffness and their effects on tissue repair. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 817391. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R-Z. ; Liu, X-Q. Biophysical cues of in vitro biomaterials-based artificial extracellular matrix guide cancer cell plasticity, Materials Today Bio 2023, 19, 100607.

- Ondeck, M.G.; Kumar, A.; Placone, J.K.; Plunkett, C.M.; Matte, B.F.; Wong, K.C.; Fattet, L.; Yang, J.; Engler, A.J. Dynamically stiffened matrix promotes malignant transformation of mammary epithelial cells via collective mechanical signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2019, 116, 3502–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Wang, Z.X.; Hu, Q.F.; Luo, H.; Lu, B.C.; Gao, Y.H.; Qiao, Z.; Zhou, Y.S.; Fang, Y.C.; Gu, J.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, Z. 3D bioprinted GelMA-nanoclay hydrogels induce colorectal cancer stem cells through activating wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Small, 2022, 18, e2200364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Chien, S.; Yang, C. Extracellular matrix stiffness dictates Wnt expression through integrin pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbolina, M.V.; Liu, Y.; Gurle, H.; Kim, M.; Kajdacsy-Balla, A.A.; Rooper, L.; Shepard, J.; Weiss, M.; Shea, L.D.; Penzes, P.; Ravosa, M.J.; Stack, M.S. Matrix rigidity activates Wnt signaling through down-regulation of Dickkopf-1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288, 288,141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendás-Franco, N.; García, J.M.; Peña, C.; Valle, N.; Pálmer, H.G.; Heinäniemi, M.; Carlberg, C.; Jiménez, B.; Bonilla, F.; Muñoz, A.; González-Sancho, J.M. DICKKOPF-4 is induced by TCF/beta-catenin and upregulated in human colon cancer, promotes tumour cell invasion and angiogenesis and is repressed by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Oncogene, 2008, 27, 4467–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendás-Franco, N.; Aguilera, O.; Pereira, F.; González-Sancho, J.M.; Muñoz, A. Vitamin D and Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in colon cancer: role and regulation of DICKKOPF genes. Anticancer Res. 2008, 28, 2613–2623. [Google Scholar]

- Manfreda, L.; Rampazzo, E.; Persano, L. Wnt signaling in brain tumors: A challenging therapeutic target. Biology (Basel). 2023, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Mirza, S.; Wu, S.; Zeng, J.; Shi, W.; Band, H.; Band, V.; Duan, B. 3D hydrogel breast cancer models for studying the effects of hypoxia on epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2018, 9, 32191–32203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, Y.; Mukohara, T.; Shimono, Y.; Funakosh, Y.; Chayahara, N.; Toyoda, M.; Kiyota, N.; Takao, S.; Kono, S.; Nakatsura, T.; Minami, H. Comparison of 2D- and 3D-culture models as drug-testing platforms in breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015, 33, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dit Faute, M.A.; Laurent, L.; Ploton, D.; Poupon, M.F.; Jardillier, J.C.; Bobichon, H. Distinctive alterations of invasiveness, drug resistance and cell-cell organization in 3D-cultures of MCF-7, a human breast cancer cell line, and its multidrug resistant variant. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002, 19, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelNero, P.; Lane, M.; Verbridge, S.S.; Kwee, B.; Kermani, P.; Hempstead, B.; Stroock, A.; Fischbach, C. 3D culture broadly regulates tumor cell hypoxia response and angiogenesis via pro-inflammatory pathways. Biomaterials 2015, 55, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Morsut, L.; Aragona, M.; Enzo, E.; Giulitti, S.; Cordenonsi, M.; Zanconato, F.; Le Digabel, J.; Forcato, M.; Bicciato, S.; Elvassore, N.; Piccolo, S. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 2011, 474, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanconato, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. YAP/TAZ at the roots of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016, 29, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruyne, T.; Steenput, B.; Roth, L.; De Meyer, G.R.Y.; dos Santos, C.N.; Valentová, K.; Dambrova, M.; Hermans, N. Dietary polyphenols targeting arterial stiffness: Interplay of contributing mechanisms and gut microbiome-related metabolism. Nutrients 2019, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerch, G. Severe COVID-19—A review of suggested mechanisms based on the role of extracellular matrix stiffness. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serino, A.; Salazar, G. Protective role of polyphenols against vascular inflammation, aging and cardiovascular disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcan, I.; Yemenicioğlu, A. Incorporating phenolic compounds opens a new perspective to use zein films as flexible bioactive packaging materials. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmambux, M. N.; Stading, M.; Taylor, J. R. N. Sorghum kafirin film property modification with hydrolysable and condensed tannins. J Cereal Sci 2004, 40, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Ahmadi, Z.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samarghandian, S. Curcumin activates the Nrf2 pathway and induces cellular protection against oxidative injury. Curr Mol Med 2020, 20, 20,116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Dou, W.; Zheng, Y.; Wen, Q.; Qin, M.; Wang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhang, R.; Lv, D.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S. Curcumin upregulates Nrf2 nuclear translocation and protects rat hepatic stellate cells against oxidative stress. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 1717–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Shoorei, H.; Bahroudi, Z.; Hussen, B.M.; Talebi, S.F.; Taheri, M.; Ayatollahi, S.A. Nrf2-related therapeutic effects of curcumin in different disorders. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerch, G. Role of extracellular matrix stiffness inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dis Dement 2022, 6, 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, N.; Khalid, S.H.; Khan, I.U.; Chauhdary, Z.; Mahmood, H.; Saleem, A.; Umair, M.; Asghar, S. Curcumin-Loaded bioactive polymer composite film of PVA/Gelatin/Tannic Acid downregulates the pro-inflammatory cytokines to expedite healing of full-thickness wounds. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 7575–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xie, S.; Li, N.; Zhang, T.; Yao, W.; Zhao, H.; Pang, W.; Han, L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J. Matrix stiffness exacerbates the proinflammatory responses of vascular smooth muscle cell through the DDR1-DNMT1 mechanotransduction axis. Bioactive Materials 2022, 17, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; He, L.-J.; Ye, H.-Z.; Liu, D.-F.; Zhu, Y.-B.; Miao, D.-D.; Zhang, S.-P.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Jia, Y.-W.; Shen, J.; et al. Nrf2 is a key factor in the reversal effect of curcumin on multidrug resistance in the HCT-8/5-Fu human colorectal cancer cell line. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 5409–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rao, J.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Z. Curcumin inhibits proliferation of breast cancer cells through Nrf2-mediated down-regulation of Fen1 expression. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 143, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barinda, A.J.; Arozal, W.; Sandhiutami, N.M.D.; Louisa, M.; Arfian, N.; Sandora, N.; Yusuf, M. Curcumin prevents epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-mediated ovarian cancer progression through NRF2/ETBR/ET-1 axis and preserves mitochondria biogenesis in kidney after cisplatin administration. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 12, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, S.; Seeneevassen, L.; Fratacci, A.; Rose, F.; Tiffon, C.; Sifré, E.; Haykal, M.M.; Moubarak, M.M.; Ducournau, A.; Bruhl, L. Nrf2 downregulation contributes to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in Helicobacter pylori-infected cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deptuła, P.; Suprewicz, L.; Daniluk, T.; Namiot, A.; Chmielewska, S.J.; Daniluk, U.; Lebensztejn, D.; Bucki, R. Nanomechanical hallmarks of Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatric patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, H.T.; Dass, C.R.; Dunstan, D.E. Injectable chitosan hydrogels for localised cancer therapy. J Control Release 2008, 126, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garshasbi, H.; Salehi, S.; Naghib, S.M.; Ghorbanzadeh, S.; Zhang, W. Stimuli-responsive injectable chitosan based hydrogels for controlled drug delivery systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1126774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.; Roca-Melendres, M. M.; Durán-Lara, E. F.; Rafael, D.; Schwartz, S. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels for cancer treatment: The role of pH, light, ionic strength and magnetic field. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1164–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F. Z.; Wang, H. F.; Guan, J.; Fu, J. N.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J. Y; Chen, Y.R.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.K. Y; Chen Y.R.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.K. Fabrication of injectable chitosan-chondroitin sulfate hydrogel embedding kartogenin loaded microspheres as an ultrasound-triggered drug delivery system for cartilage tissue engineering. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1487–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäki-Petäjä, K.M.; Hall, F.C.; Booth, A.D.; Wallace, S.M.; Yasmin; Bearcroft, P.W.; Harish, S.; Furlong, A.; McEniery, C.M.; Brown, J. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with increased aortic pulse-wave velocity, which is reduced by anti–tumor necrosis factor-α therapy. Circulation 2006, 114, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, S.S. NF-kappa B in rheumatoid arthritis: a pivotal regulator of inflammation, hyperplasia, and tissue destruction. Arthritis Res. 2001, 3, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilchovska, D.; Barrow, M. An overview of the NF-kB mechanism of pathophysiology in rheumatoid arthritis, investigation of the NF-kB ligand RANKL and related nutritional interventions. Autoimmunity Reviews 2021, 20, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X. (2018). Matrix stiffness regulates oxidative stress response of human dermal fibroblasts. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Available online: https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/handle/10220/46707.

- Zhou, R.H.; Vendrov, A.E.; Tchivilev, I.; Niu, X.L.; Molnar, K.C.; Rojas, M.; Carter, J.D.; Tong, H.; Stouffer, G.A.; Madamanchi, N.R.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in aortic stiffening with age: The role of smooth muscle cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, R.L.; Swaminathan, S.; Clyne, A.M. Stiff substrates enhance endothelial oxidative stress in response to protein kinase C activation. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2019, 2019, 6578492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, Y.; Khan, J.A.; Chetter, I. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors effect on arterial stiffness and wave reflections: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomised controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2012, 221, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.F.; Cunha, A.R.; Cunha, M.R.; Gismondi, R.A.; Oigman, W. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and its new components in arterial stiffness and vascular aging. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2018, 25, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumaras, C.; Tziomalos, K.; Stavrinou, E.; Katsiki, N.; Athyros, VG.; Mikhailidis, DP.; Karagiannis, A. Effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and beta-blockers on markers of arterial stiffness. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014, 8, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.H.; Lai, Y.H.; Hung, C.L.; Lee, P.Y.; Kuo, J.Y.; Yeh, H.I.; Hou, C.J.; Chien, K.L. Angiotensin receptor blockades effect on peripheral muscular and central aortic arterial stiffness: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and systematic review. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2014, 30, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).