Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

22 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

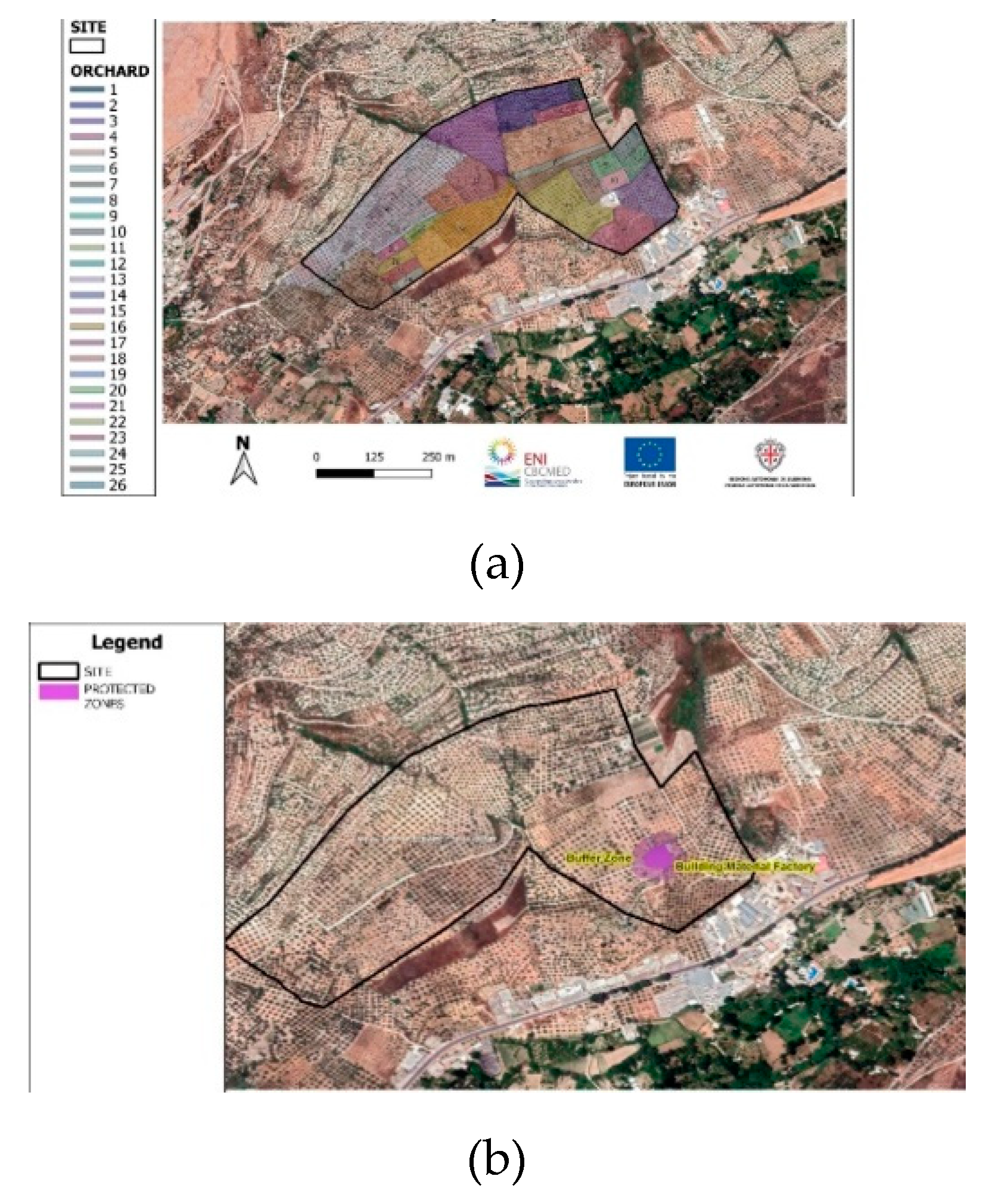

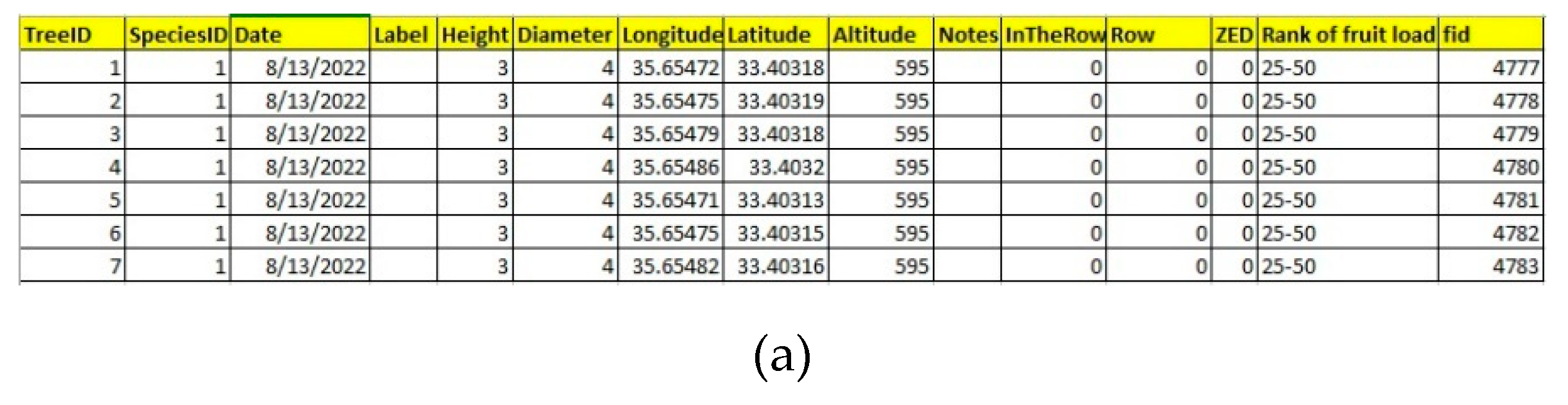

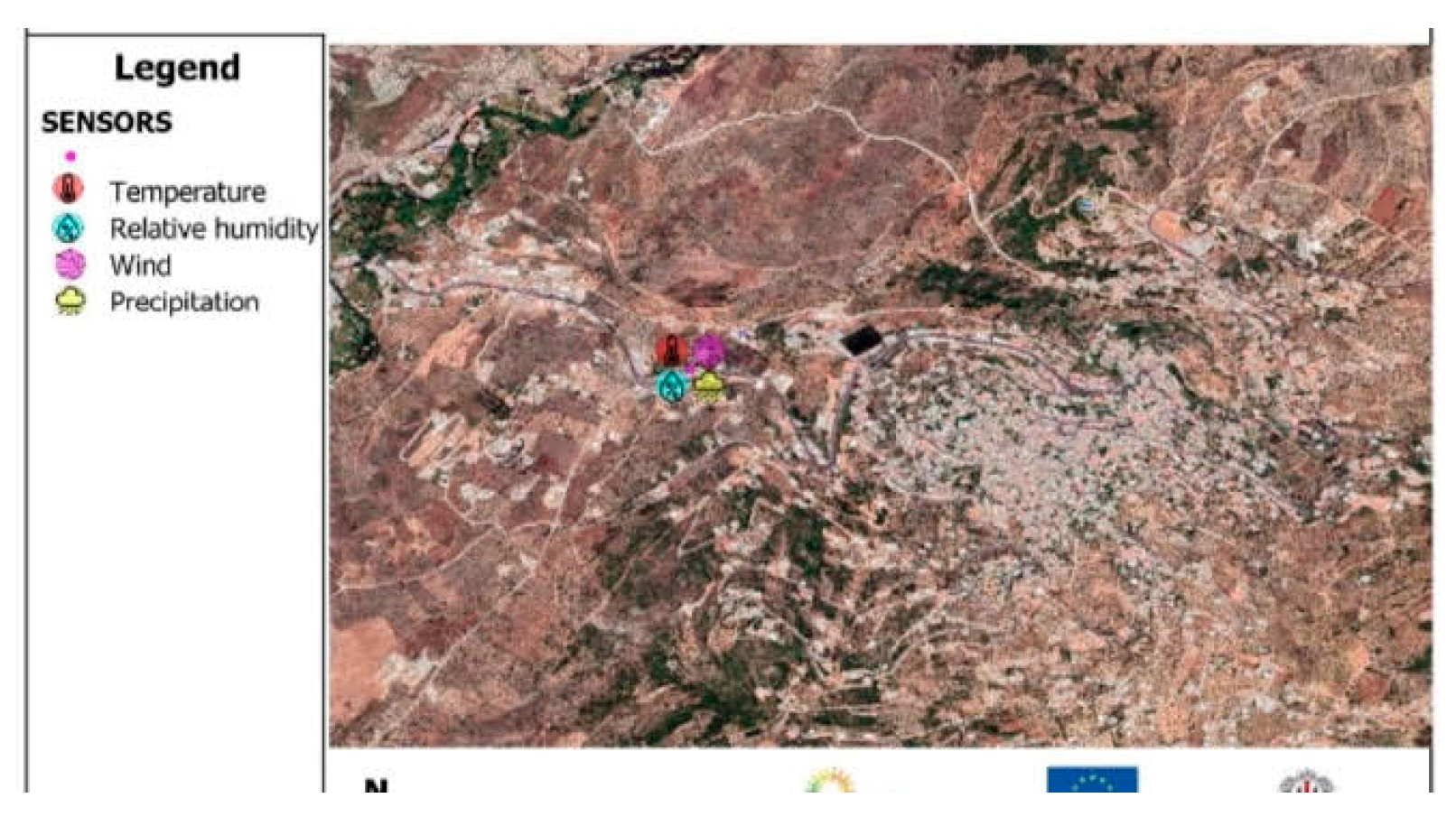

2.1. Experimental Site

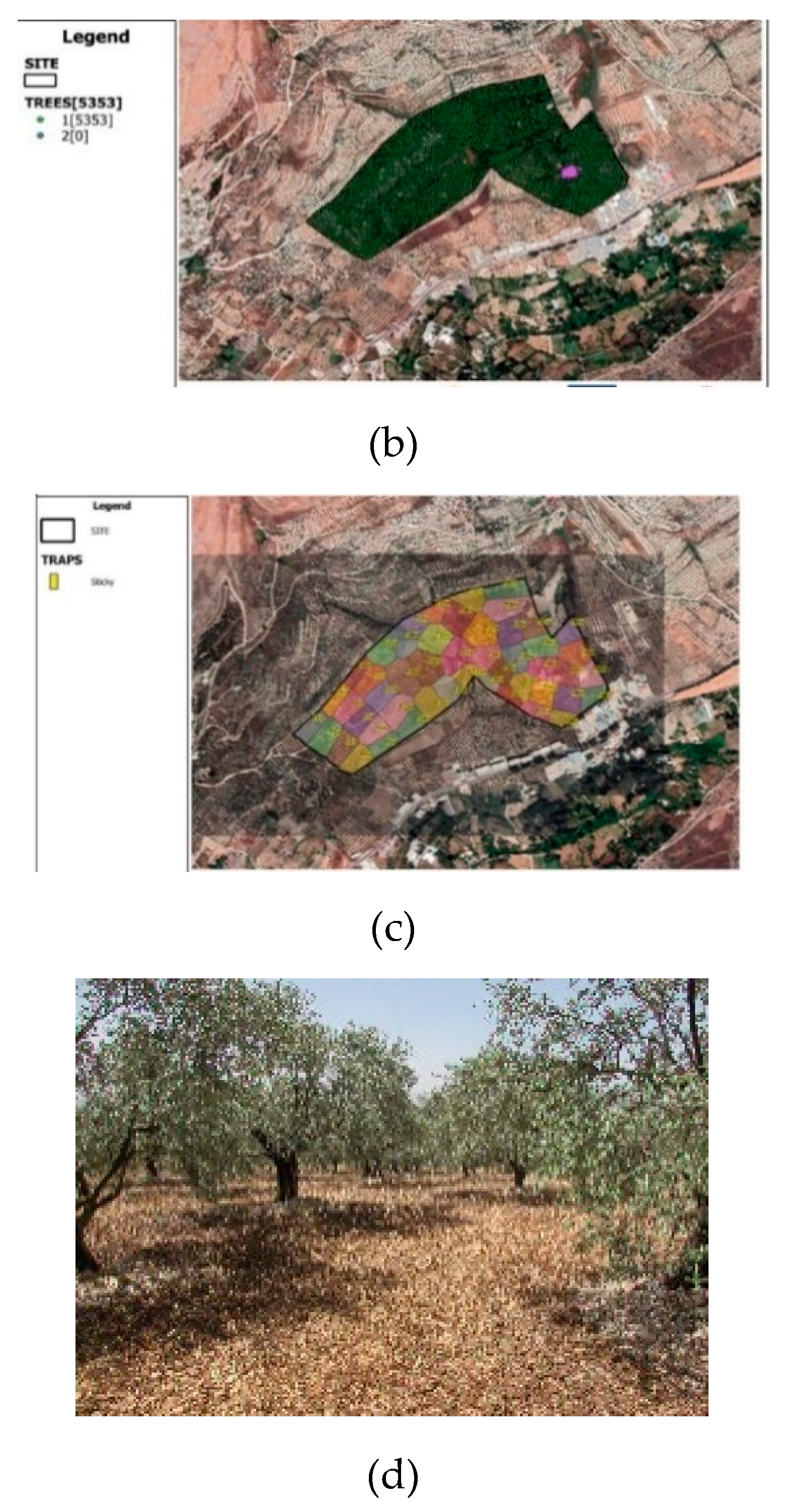

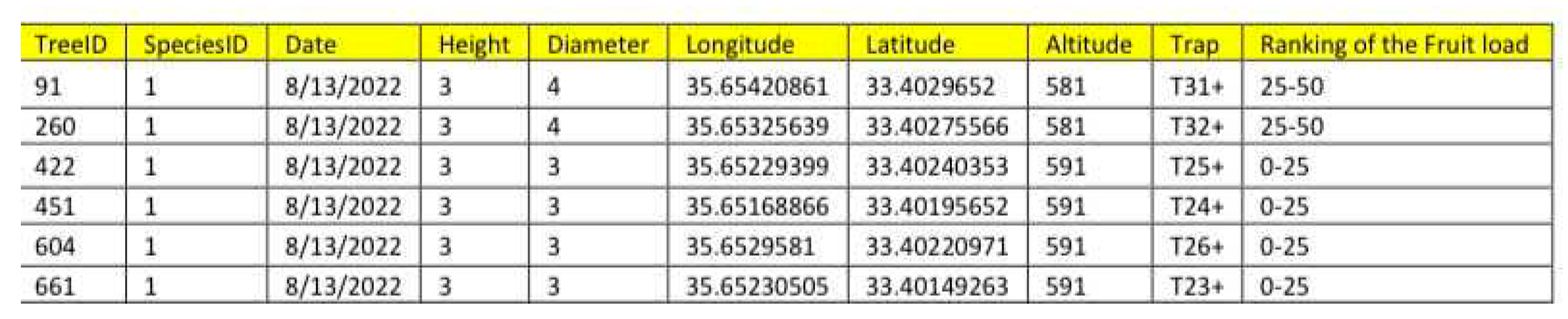

2.2. Trees and practices

2.3. Trap Installation

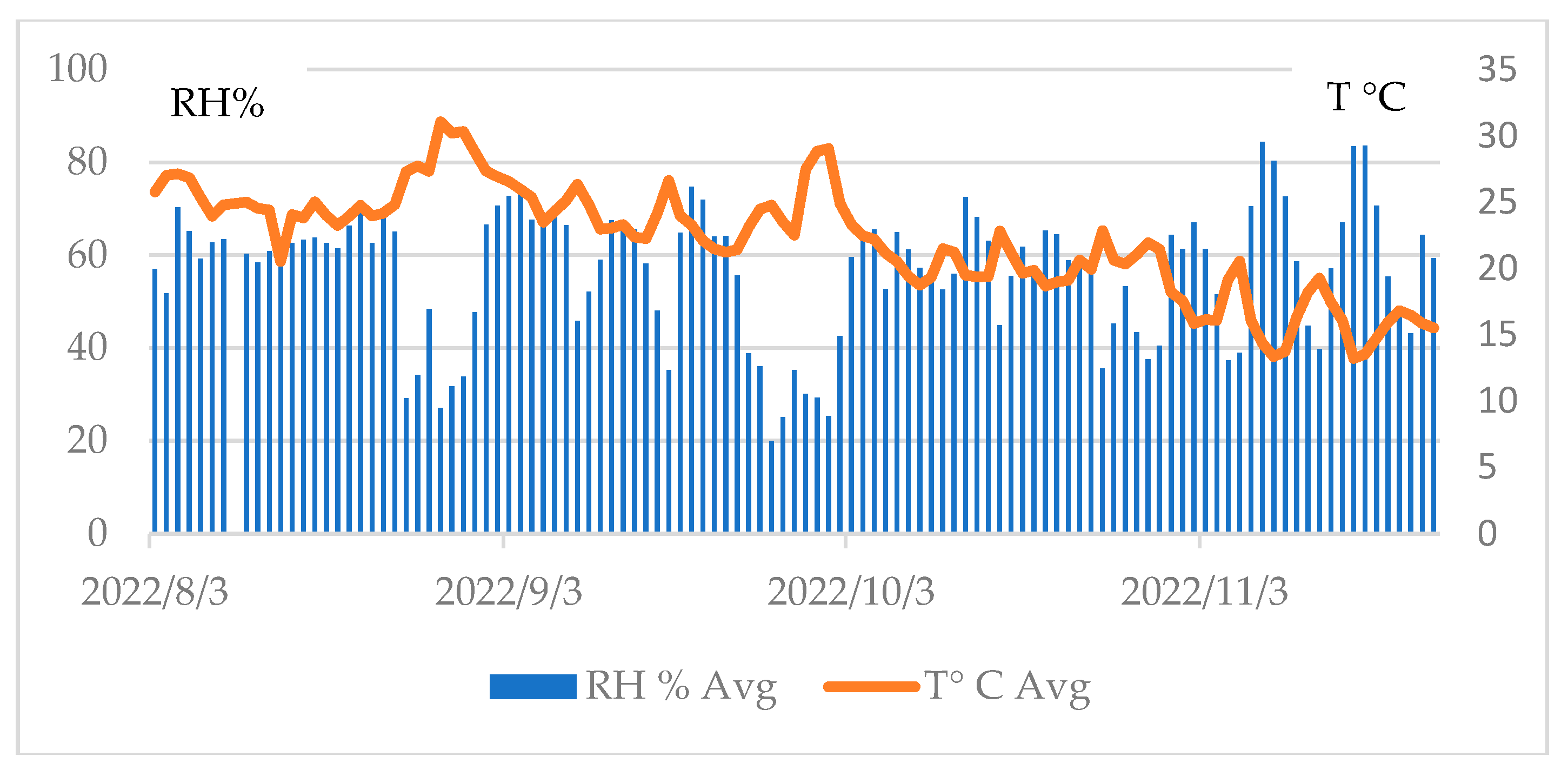

2.4. Meteorological Data Monitoring

2.5. Parameters Studied to Take Decision for Spraying

2.5.1. Pest Captures

2.5.2. BBCH Value

2.5.3. Rate of Fruit Infestation, RFI

2.6. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

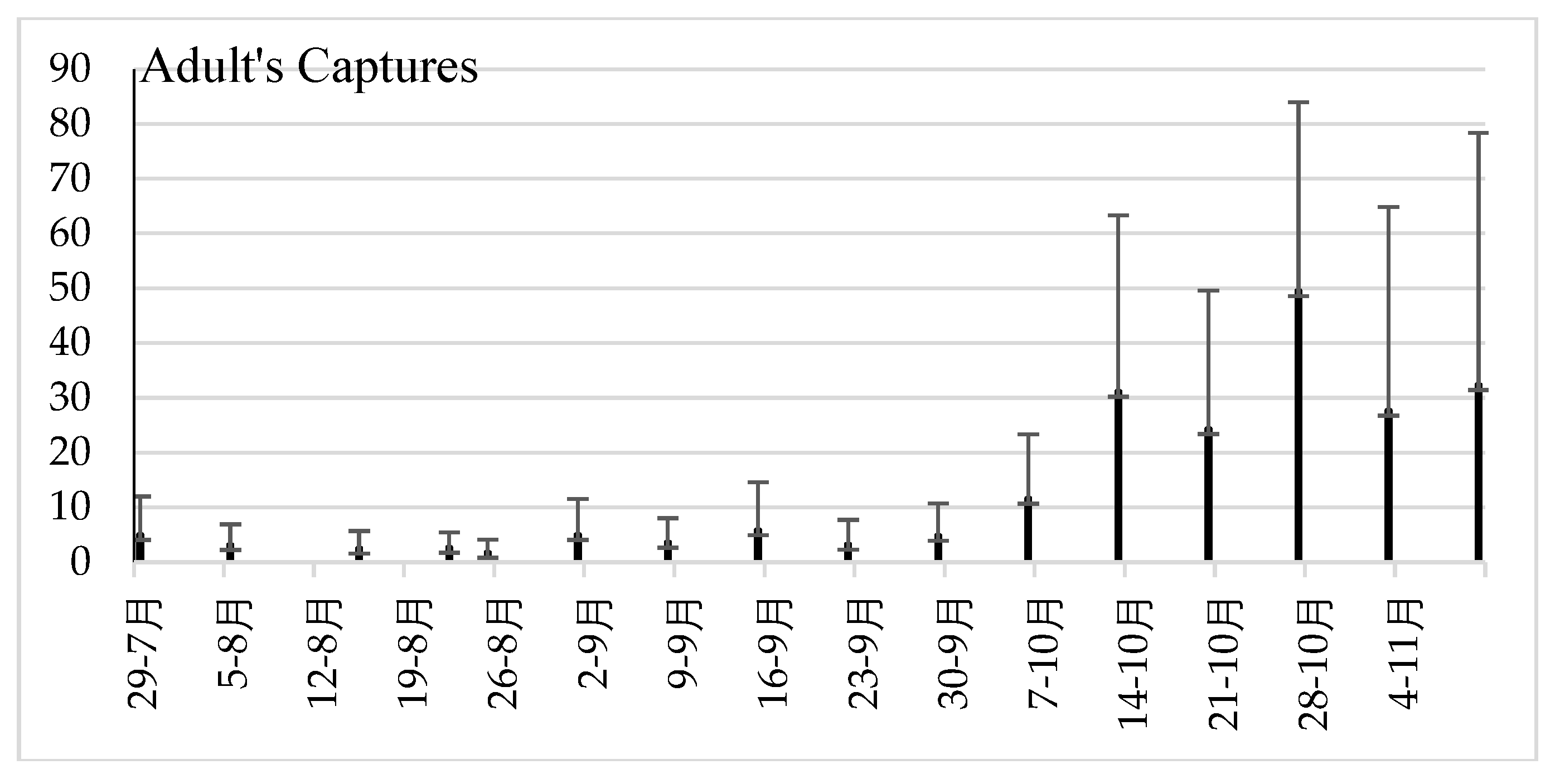

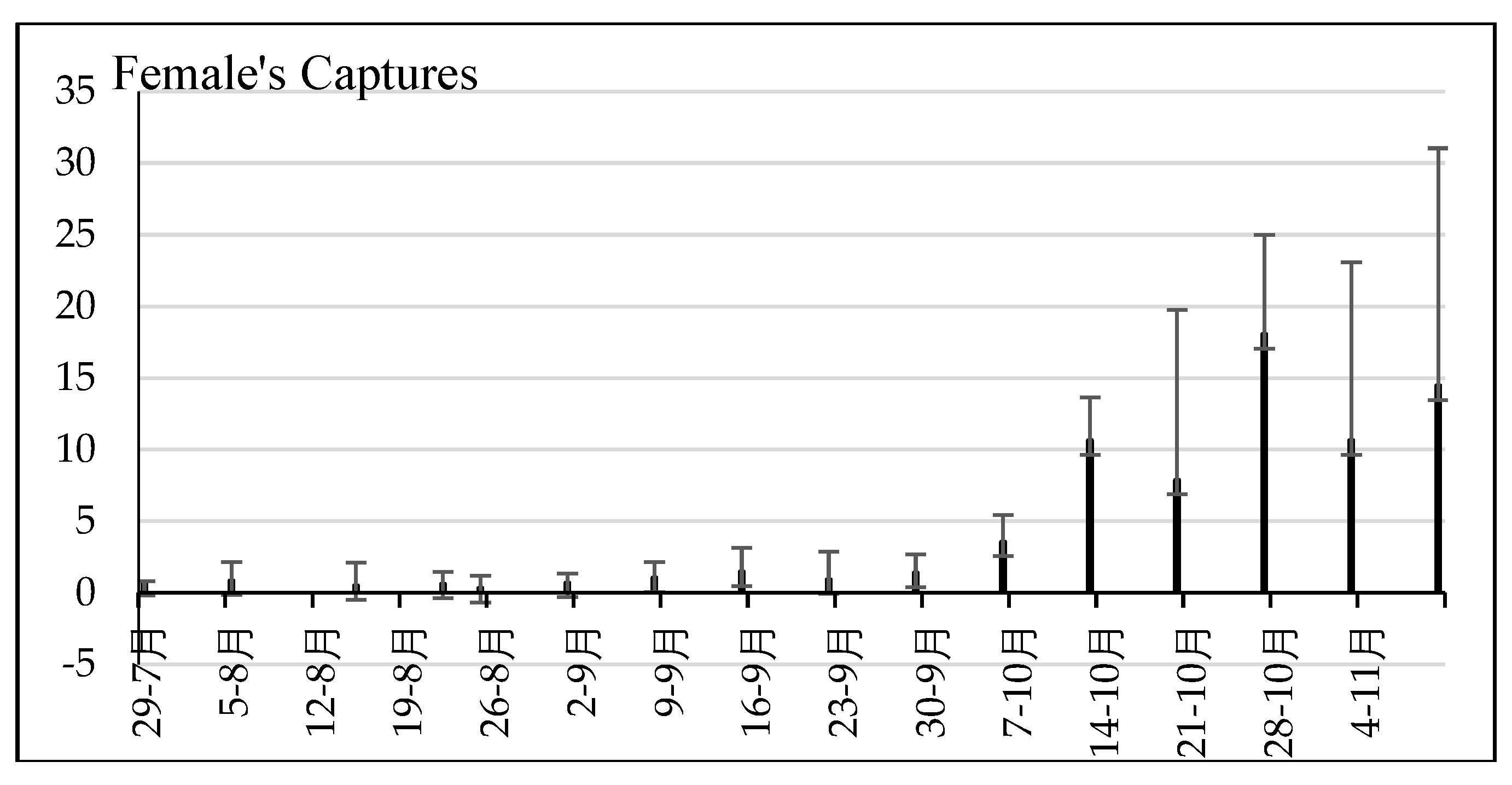

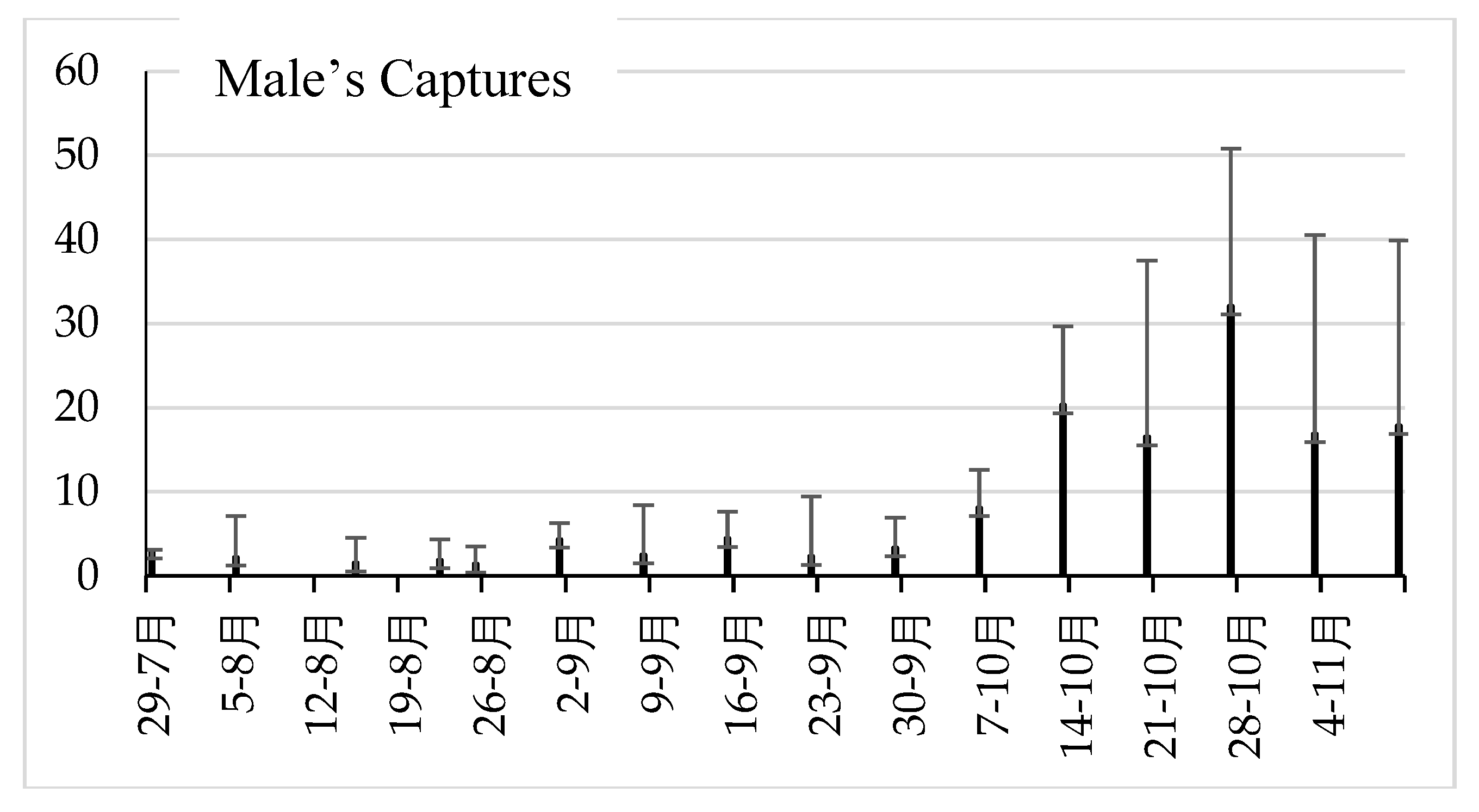

3.1. Monitoring of the Adults

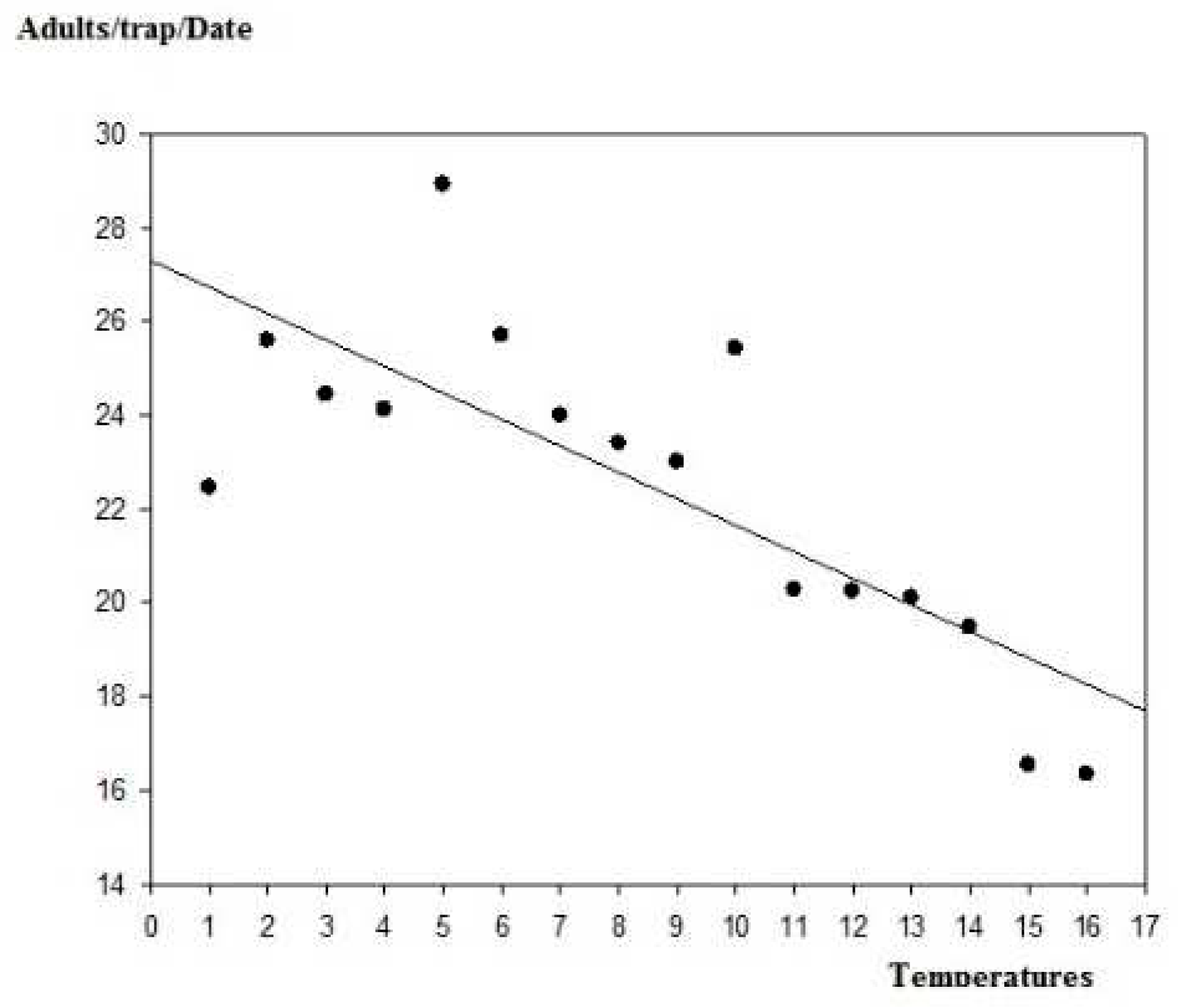

3.2. Adult Abundance

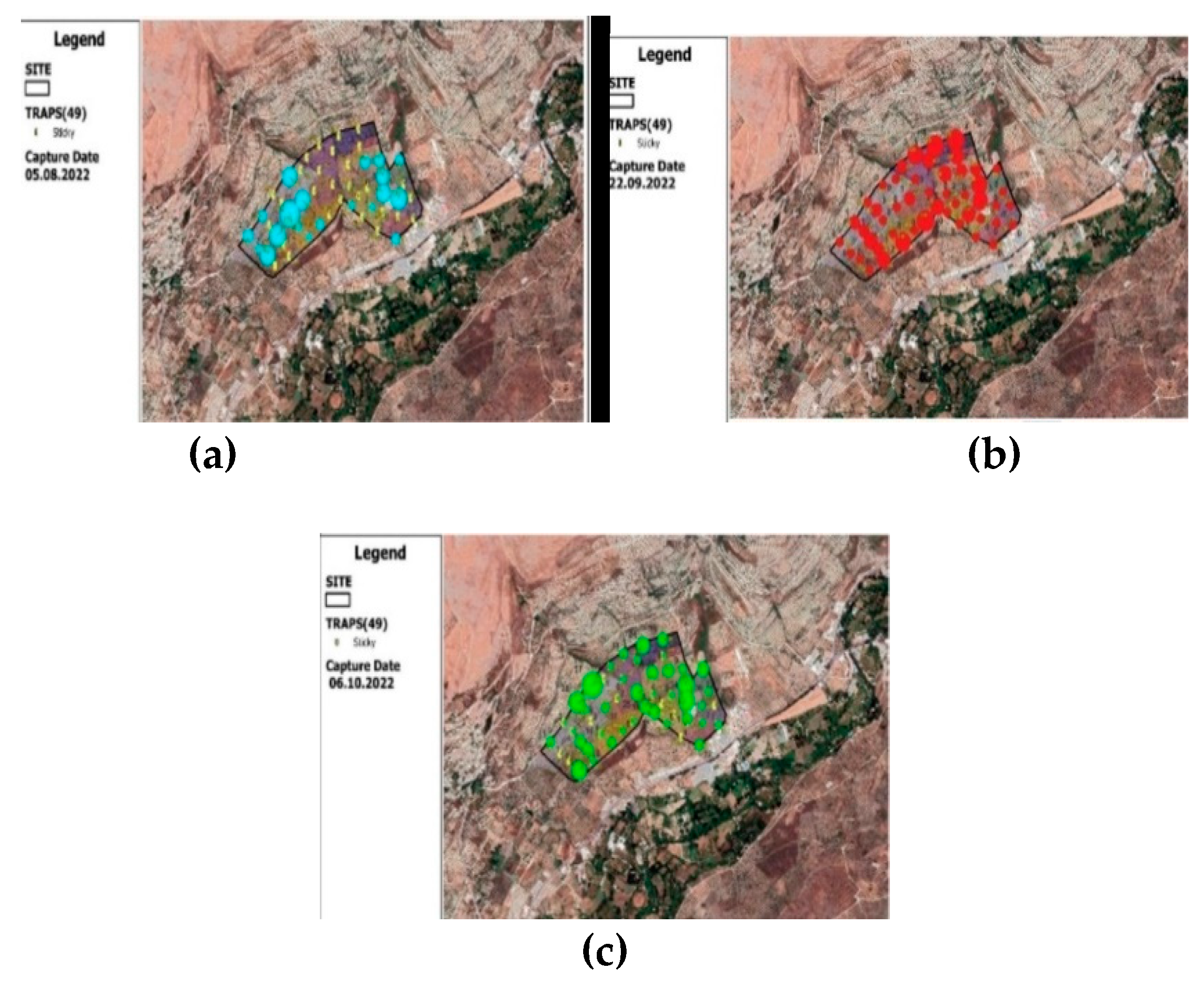

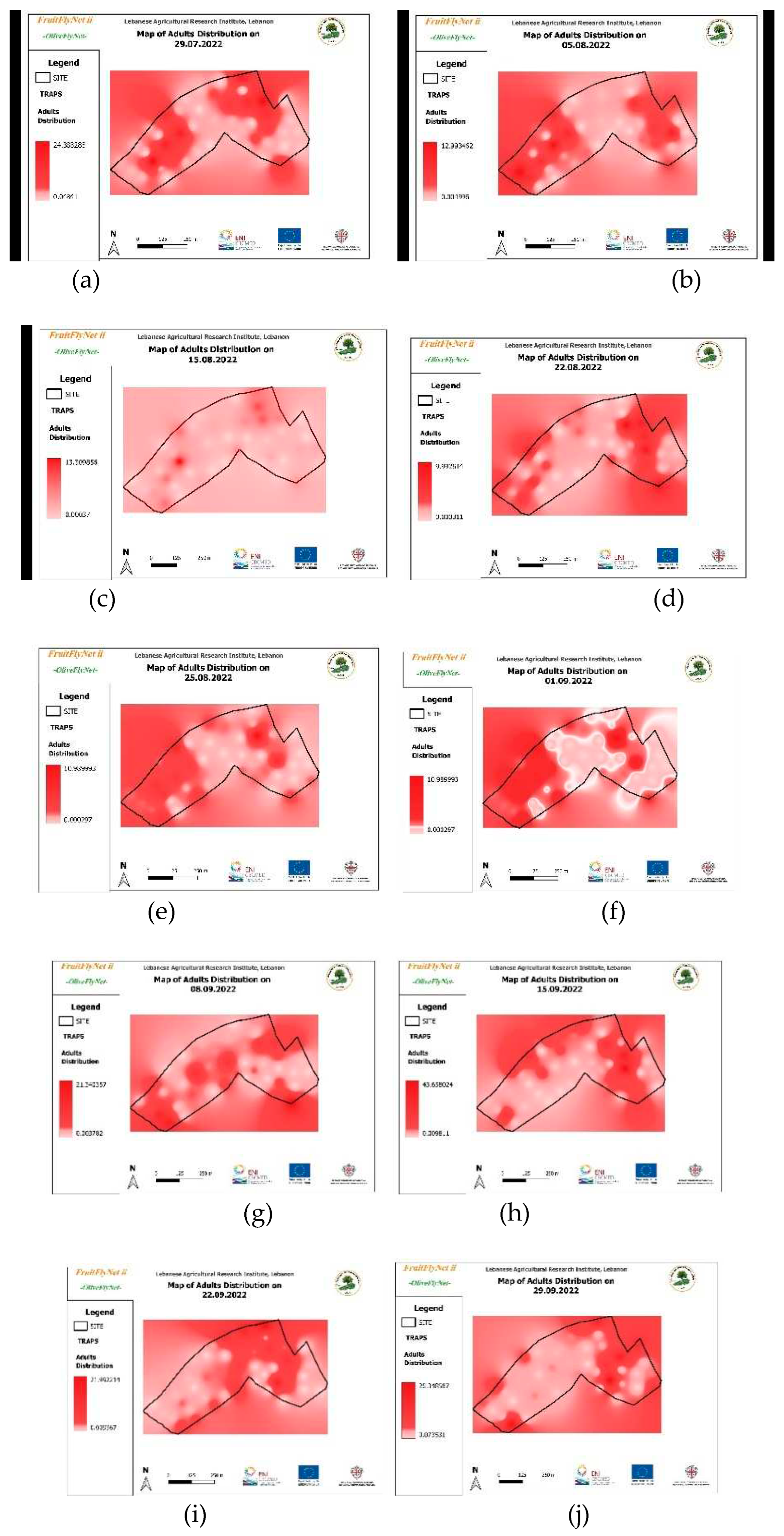

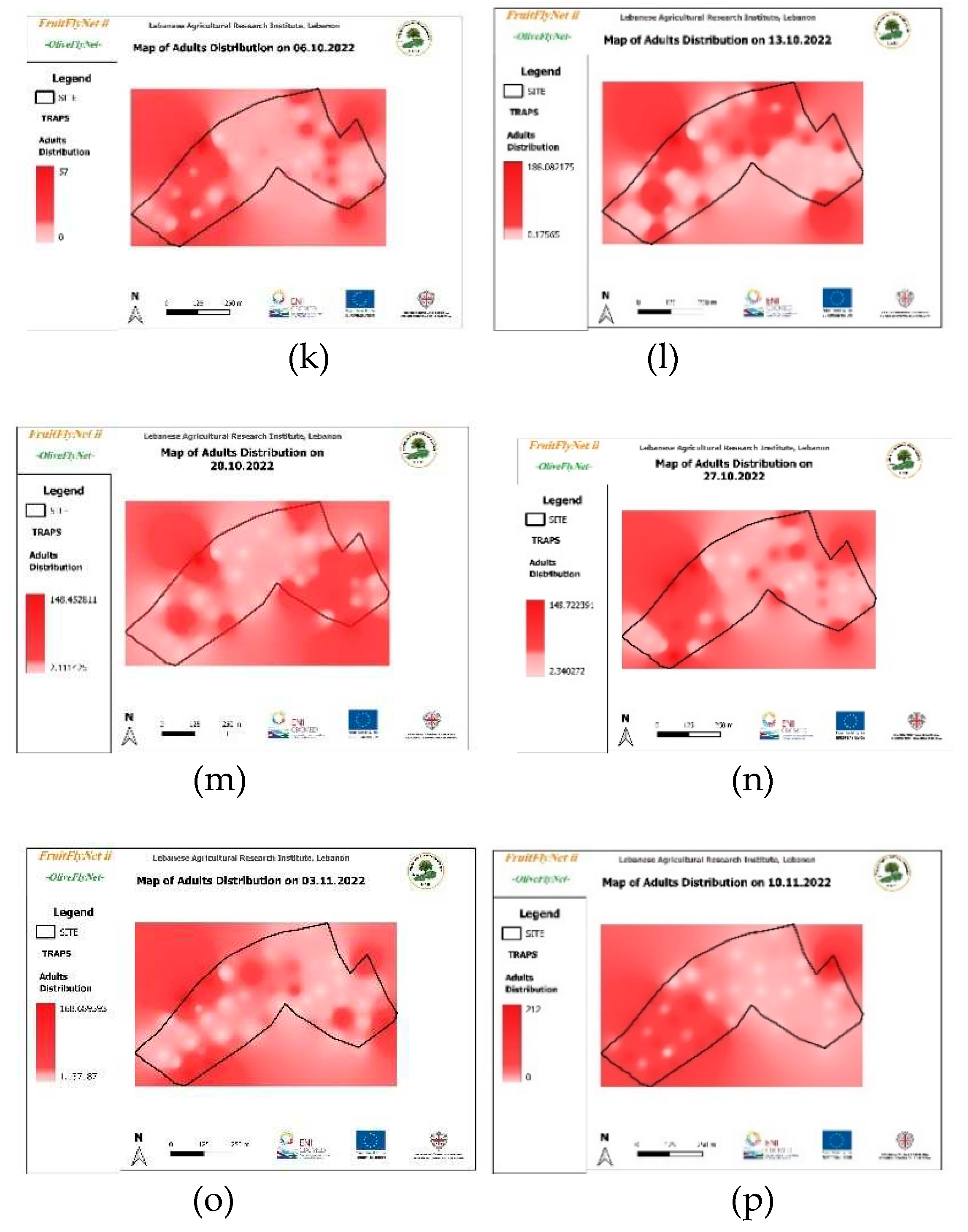

3.3. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Bactrocera oleae Adults

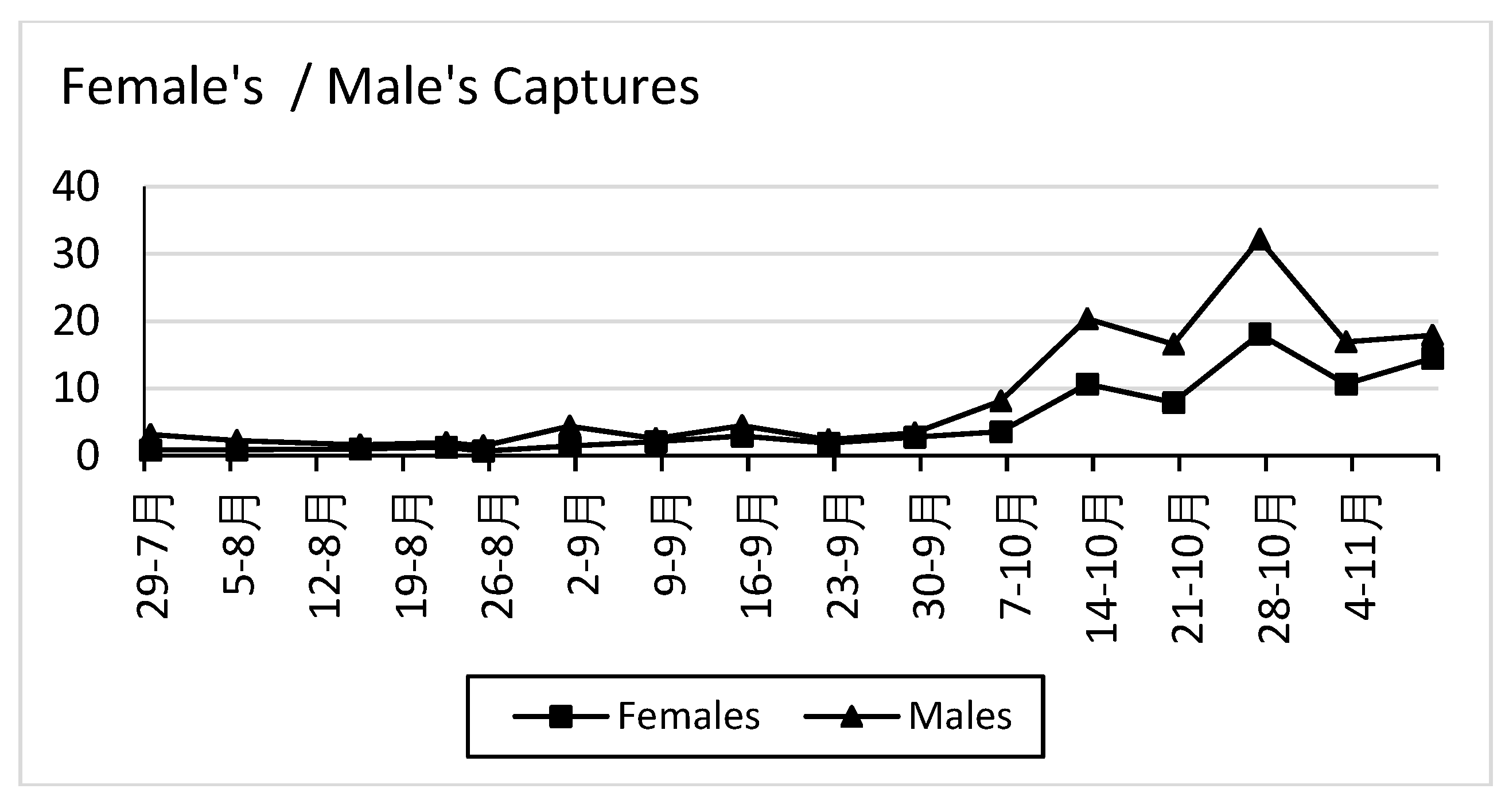

3.4. Sex Ratio

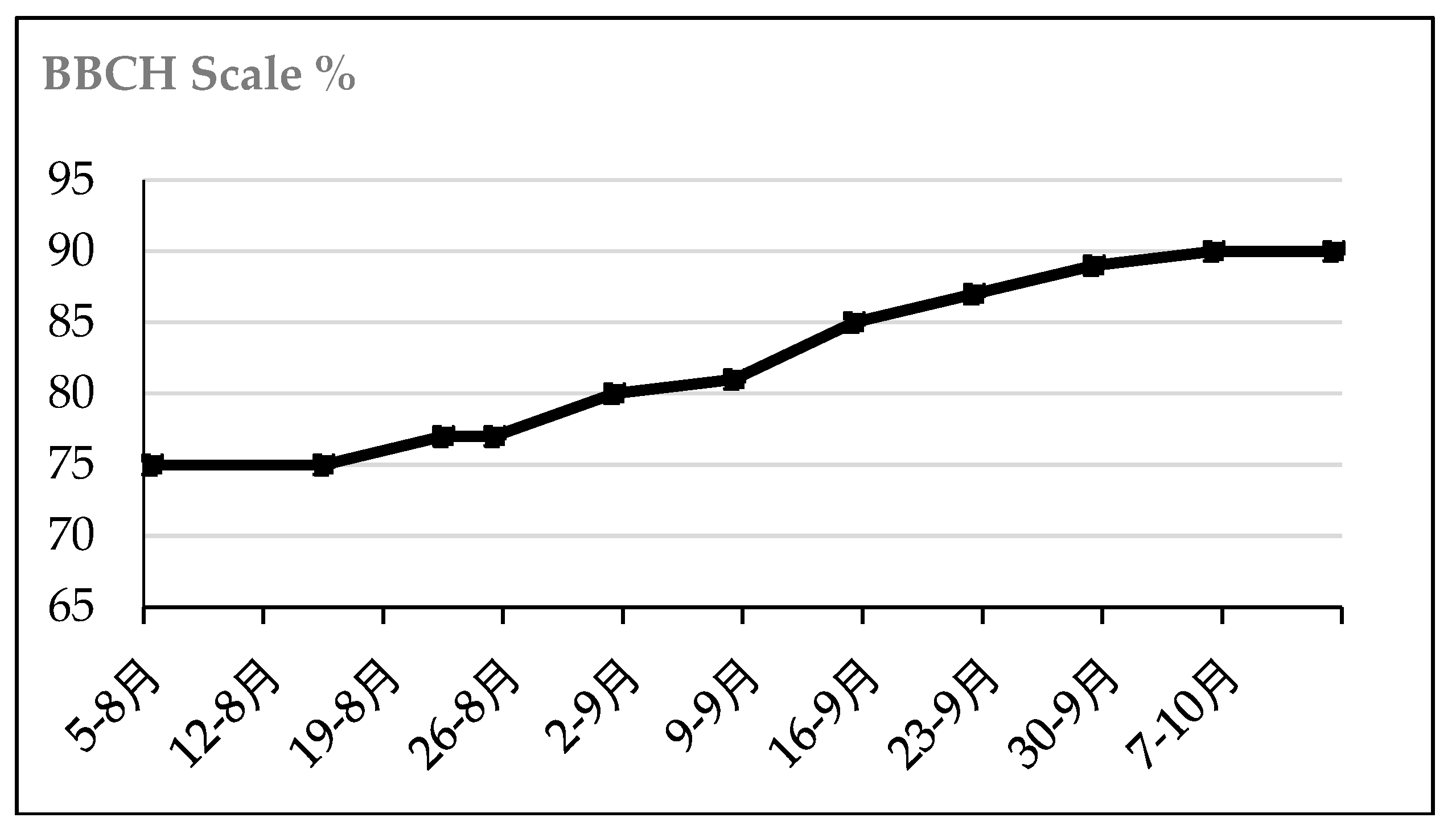

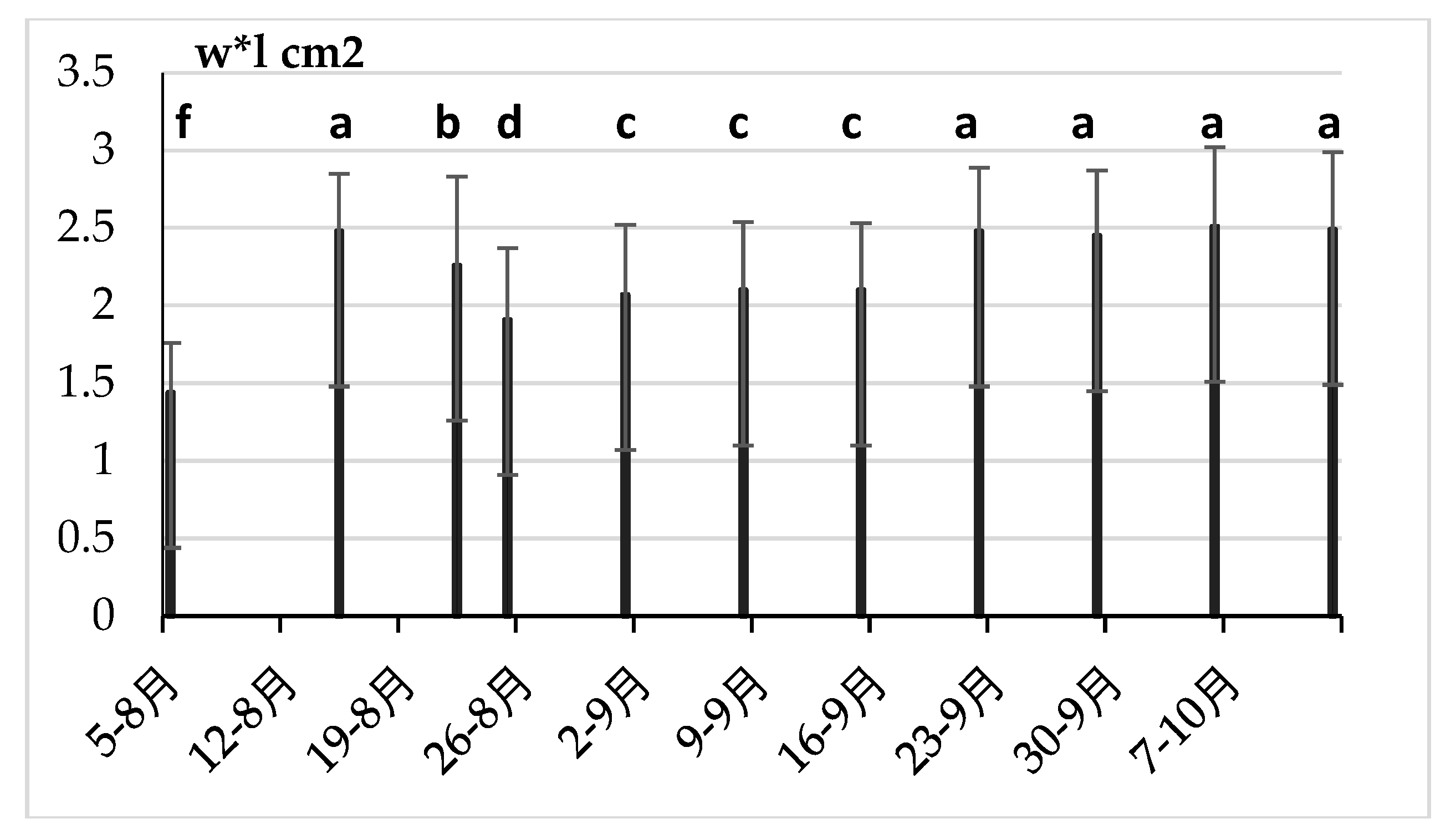

3.5. BBCH and fruit Dimensions

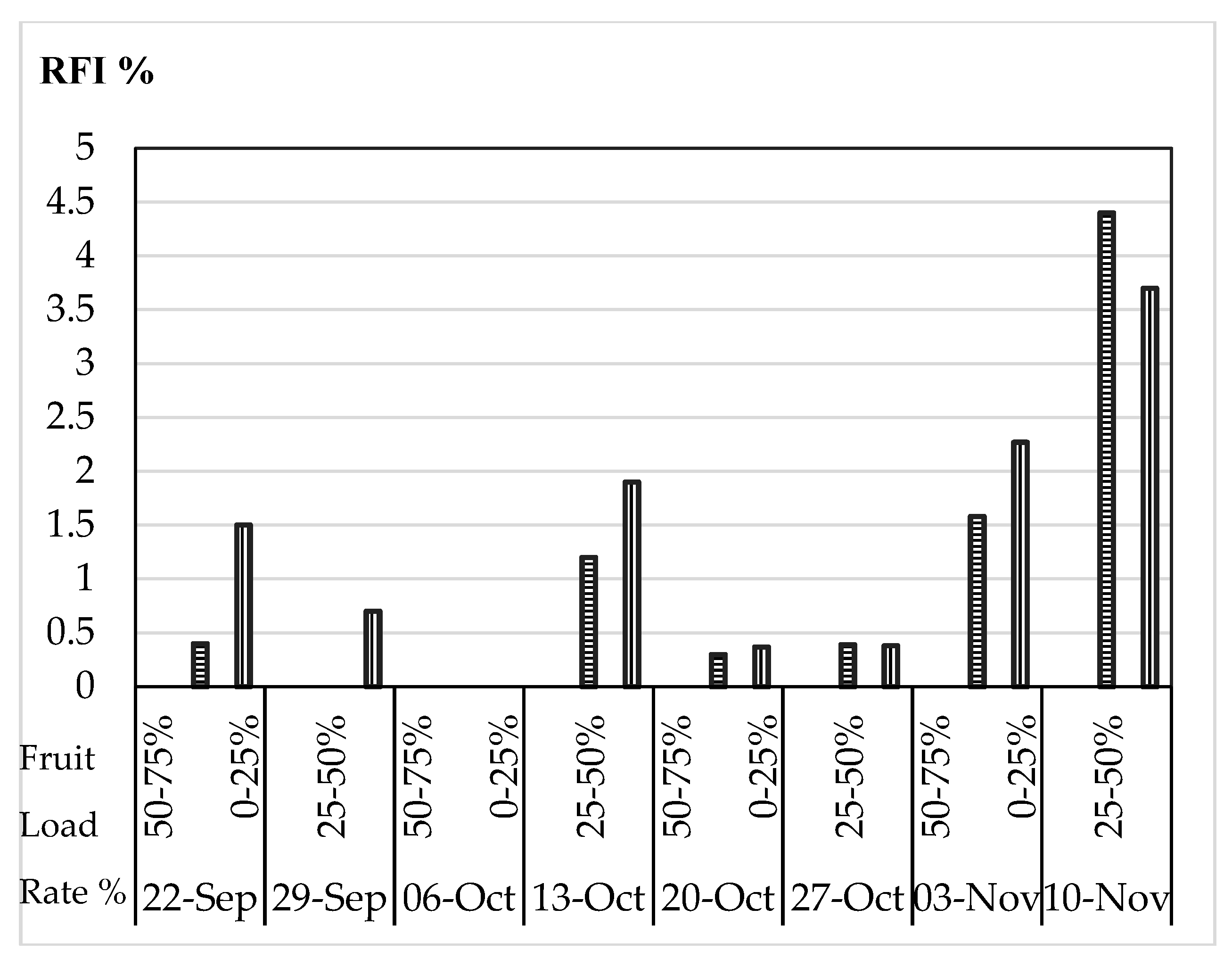

3.6. Fruit Infestation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Abdel Kader El-hajj, Nabil Nemer, SamerHajj Chhadeh, Faten Dandashi, Hiyam Yosef, Mouhammed Nasrallah, Mayssaa Houssein,Vera Talj, Mahmoud Haris, Zinnet Moussa. Status, Distribution and Parasitism Rate of Olive Fruit Fly (Bactrocera oleae.Rossi) Natural Enemies in Lebanon. Journal of Agricultural Studies 2018, ISNN 2166-0379, Vol. 6, No1. [CrossRef]

- F. Nardi, A. Carapelli, R. Dallai, G.K. Roderick, F. Frati. Population structure and colonization history of the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae (Diptera, Tephritidae). Mol. Ecol., 2005, 14, pp. 2729-2738.

- L. Ponti, Q.A. Cossu, A.P. Gutierrez. Climate warming effects on the Olea europaea - Bactrocera oleae system in Mediterranean islands: sardinia as an example. Glob. Chang. Biol., 2009, 15, pp. 2874 – 2884.

- N.E. Zygouridis, A.A. Augustinos, F.G. Zalom, K.D. Mathiopoulos. Analysis of olive fly invasion in California based on microsatellite markers. Heredity (Edinb), 2009, 102, pp. 402-412.

- Daniela MARCHINI, Ruggero PETACCHI, Susanna MARCHI. Bactrocera oleae reproductive biology: new evidence on wintering wild populations in olive groves of Tuscany (Italy), Bulletin of Insectology 2017, 70 (1): 121-128, ISSN 1721-8861. 1.

- Zalom F., G. , Van Steenwyk R. A., and Burrack H. J. Olive fruit fly. Pest Notes, University of California, publication, 2009, 74112, 4 p.

- G. Caruso, A. Loni, A. Raspi, R. Gucci, B. Bagnoli. Olive fruit fly effects on free acidity and peroxides value of olive oil. Acta Hortic. 1057, 281-286. In VII International Symposium on Olive Growing. Ed., F. Vita Serman, P. Searles, M. Torres, 2014. ISBN 978-94-62610-47-7. [CrossRef]

- Manousis Thanasis and Moore N. F. Control of Dacus oleae, a major pest of olives. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 1987, 8 (01). [CrossRef]

- Mazomenos, B. E. , Pantazi-Mazomenou, A., & Stefanou, D. Attract and kill of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae in Greece as a part of an integrated control system. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin, 2002, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel Bueno, A. and Jones, 0. Alternative methods for controlling the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae, involving semiochemicals. Bulletin OILB/SROP, 2002, Vol. 25, No9, 147-155pp.

- Neuenschwander, P., Michelakis, S. Determination of the lower thermal thresholds and day-degree requirements for eggs and larvae of Dacus oleae (Gmel.) (Diptera: Tephritidae) under field conditions in Crete, Greece. Bul.Soc. Ent. Suisse, 1979-a, 52: 57-74pp.

- Raspi, A., Canale, A., Loni, A. Presence of mature eggs in olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae (Diptera Tephritidae), at different constant photoperiods and at two temperatures. Bulletin of Insectology, 2005, 58 (2): 125.

- Broufas, G. D., Pappas, M. L., Koveos, D. S. Effect of relative humidity on longevity, ovarian maturation, and egg production in the olive fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 2009, 102 (1): 70-75pp.

- Rizzo, R., Caleca, V. Resistance to the attack of Bactrocera oleae (Gmelin) of some Sicilian olive cultivars. In Proceedings of Olivebioteq 2006, Second International Seminar “Biotechnology and quality of olive tree products around the Mediterranean Basin” November 5th–10th, Mazara del Vallo, Marsala, Italy, 2006, 2: 291-298pp.

- Mraicha, F., Ksantini, M., Zouch, O., Ayadi, M., Sayadi, S., Bouaziz, M. Effect of olive fruit fly infestation on the quality of olive oil from Chemlali cultivar during ripening. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2010, 48 (11): 3235-3241pp.

- Kapaun, T., Nadel, H., Headrick, D., Vredevoe, L. Biology and parasitism rates of Pteromalus nr. myopitae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), a newly discovered parasitoid of olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae) in coastal California. Biological control, 2010, 53 (1): 76-85.

- Cardenas, M.; Ruano, F.; Garcia, P.; Pascual, F.; Campos, M. Impact of agricultural management on spider populations in the canopy of olive trees. Biol. Control, 2006, 38, 188–195.

- Nobre, T.; Gomes, L.; Rei, F.T. A Re-Evaluation of Olive Fruit Fly Organophosphate-Resistant Ace Alleles in Iberia, and Field Testing Population Effects after in-Practice Dimethoate Use. Insects, 2019, 10, 232.

- Petacchi, R.; Rizzi, I.; Guidotti, D. The ‘lure and kill’ technique in Bactrocera oleae (Gmel.) control: Effectiveness indices and suitability of the technique in area-wide experimental trials. Int. J. Pest Manag., 2003, 49, 305–311.

- Iannotta,N., Belfiore,T., Noce M.E., Scalercio,S.,&Vizzarri,V. Comparison between attract and kill devices for B.oleae in an organic olive orchard: preliminary data. ISHS Acta horticulturae, 2010, 873.

- Abdul-Jalil Hamdan, Mohammad I. Al qurna. The Seasonal Flight Activity of the Olive Fruit Fly Bactrocera oleae (Gmelin) (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Central Highlands of West-Bank, Palestine. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2017, Volume 13, No.2, 457-464pp.

- Rizzo, R.; Lo Verde, G.; Sinacori, M.; Maggi, F.; Cappellacci, L.; Petrelli, R.; Vittori, S.; Morshedloo, M.R.; Fofie, N.; Benelli, G. Developing green insecticides to manage olive fruit flies? Ingestion toxicity of four essential oils in protein baits on Bactrocera oleae. Ind. Crop. Prod., 2020, 143, 111884.

- Meier, U. BBCH-Monograph. Growth Stages of Plants—Entwicklungsstadien von Pflanzen—Estadios de las Plantas—Développement des Plantes. Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1997, pp. 94–95.

- Sanz-Cortes, F.; Martinez-Calvo, J.; Badenes, M.L.; Bleiholder, H.; Hack, H.; Llacer, G.; Meier, U. Phenological growth stages of olive trees (Olea europaea). Ann. Appl. Biol., 2002, 140, 151–157.

- Arianna Di Paola, Maria Vincenza Chiriaco, Francesco Di Paola, and Giovanni Nieddu. A Phenological Model for Olive (Olea europaea L. var europaea) Growing in Italy. Plants, 2021, 10, 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10061115, 15 p.

- Kyriaki VARIKOU, Nikos GARANTONAKIS, Athanasia BIROURAKI, 2014. Response of olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae to various attractant combinations, in orchards of Crete. Bulletin of Insectology, 2014, 67 (1): 109-114, 2014. ISSN 1721-8861.

- Lavee, S. Alternate bearing in olive initiated by abiotic induction leading to biotic responses. Adv. Hort. Sci., 2015, 29(4): 213-219.

- Víctor Beyá-Marshall and Thomas Fichet, 2017. Effect of crop load on the phenological, vegetative and reproductive behavior of the ‘Frantoio’ olive tree (Olea europaea L.). In Cien. Inv. Agr. 2017, 44(1):43-53.

- Wecchsler Tahel, Bakhshian Ortal, Engelen C. Dag Arnon, Ben-Ari Giora and Samach Alon. Determining Reproductive Parameters, which Contribute to Variation in Yield of Olive Trees from Different Cultivars, Irrigation Regimes, Age and Location. Plants, 2022, 11 (18), 2414 . [CrossRef]

- Miguel Ángel Miranda, Carlos Barceló, Ferran Valdés, José Francisco Feliu, David Nestel, Nikolaos Papadopoulos, Andrea Sciarretta, Maurici Ruiz and Bartomeu Alorda. Developing and Implementation of Decision Support System (DSS) for the Control of Olive Fruit Fly, Bactrocera oleae, in Mediterranean Olive Orchards. Agronomy, 2019, 9, pp. 620-643. [CrossRef]

- SigmaPlot 12.3 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). SigmaPlot graphing software from Systat Software.

- Ordano, M.; Engelhard, I.; Rempoulakis, P.; Nemny-Lavy, E.; Blum, M.; Yasin, S.; Lensky, I.; Papadopoulos, N. and Nestel, D. Olive Fruit Fly (Bactrocera oleae) Population Dynamics in the Eastern Mediterranean: Influence of Exogenous Uncertainty on a Monophagous Frugivorous Insect. Plos one, 2015, 10(5): 1-18.

- Murat HELVACI, Mehmet AKTAŞ, Özge ÖZDEN. Occurrence, damage, and population dynamics of the olive fruit fly (Bactrocera oleae Gmelin) in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2018, 42: 453-458. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Kahime, K.; Chemseddine, M. and Boumezzough, A. Study of the Population Dynamics of the Olive Fly, Bactrocera oleae Rossi. (Diptera, Tephritidae) in the Region of Essaouira. Open Journal of Ecology, 2015, 5: 174-186. 1: 5.

- Achouche A., Abbassi F., Benzahra A., Djazouli Z. Study of population dynamics of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae (Diptera, Tephritidae); (rossi, 1790) in the Mezghenna area. Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2019, 9 (3) pp. 309-314.

- Abd El-Salam, A.M.E.; Salem, S.A.; El-Kholy, M.Y.; Abdel-Rahman, R.S. and Abdel-Raheem, M. A. Role of the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae (rossi) traps in integrated pest management on olive trees under climatic change conditions in egypt. Plant Archives, 2019, Vol. 19, Supplement 2, pp. 457-461.

- Gonçalves, F. M. , Rodrigues, M. C., Pereira, J. A., Thistlewood, H., & Torres, L. M. Natural mortality of immature stages of Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae) in traditional olive groves from north-eastern Portugal. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2012, 22, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, S. , Guidotti, D., Ricciolini, M., & Petacchi, R. Towards understanding temporal and spatial dynamics of Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) infestations using decade-long agrometeorological time series. International Journal of Biometeorology, 2016, 60, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ant, T. , Koukidou, M., Rempoulakis, P., Gong, H.-F., Economopoulos, A., Vontas, J., & Alphey, L. Control of the olive fruit fly using genetics-enhanced sterile insect technique. BMC Biology, 2012, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, S. , Bellocchi, G., & Pucci, C. IPM trials on attract-and-kill mixtures against the olive fly Bactrocera oleae (Diptera Tephritidae). Bulletin of Insectology, 2004, 57, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zervas, G. Reproductive physiology of Dacus oleae (GMELIN) Diptera Tephritidae. Comparison of wild and laboratory reared flies. In Geoponika, 1982. https://agris.fao.org.

- Katsoyannos, B. I. , & Kouloussis, N. A. Captures of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae on spheres of different colours. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2001, 100, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R., Virgilio, C., & Alberto, L. Relation of fruit color, elongation, hardness, and volume to the infestation of olive cultivars by the olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2012, 145, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Enrique Quesada-Moraga, Cándido Santiago-Álvarez, Salvador Cubero-González, Germán Casado-Mármol, Alfonso Ariza-Fernández, Meelad Yousef. Field evaluation of the susceptibility of mill and table olive varieties to egg-laying of olive fly. Journal of Applied Entomology, 2018, 142, pp.765–774.

- Zouros, E., & Krimbas, C. B. Frequency of female digamy in a natural population of the olive fruit fly Dacus oleae as found using enzyme polymorphism. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 1970, 13, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Merle Preu, Johannes L. Frieß, Broder Breckling and Winfried Schröder. Chapter: Case Study 1: Olive Fruit Fly (Bactrocera oleae). In Book: Gene Drives at tipping points. Precautionary technology assessement and governance of new approaches to genetically modify animal and plant populations. Ed., A. Von Gleich and W. Schroder; Publisher: Springer Open, Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland, 2019, pp. 79-102. [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M. , Pucci, C., & Montanan, G. E. Dacus oleae (Gmel.) ovipositing in olive drupes (Diptera, Tephrytidae). Journal of Applied Entomology 1986, 101, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümusay, B. , Ozilbey, U., Ertem, G., & Oktar, V. Studies on the susceptibility of some important table and oil olive cultivars of Aegean Region to olive fly (Dacus oleae Gmel.) in Turkey. Acta Horticulturae 1990, 286, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, P. , Michelakis, S., Holloway, P., & Berchtol, W. Factors affecting the susceptibility of fruits of different olive varieties to attack by Dacus oleae (Gmel.) (Dipt., Tephritidae). Journal of Applied Entomology 2009, 100, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicenik Devarenne A, Vossen PM. Monitoring and organic control of olive fruit fly. In: Vossen PM (ed.). Organic Olive Production Manual, 2007, UC ANR Pub 3505. Oakland, CA. p 47–51.

- Fletcher, B. S. , & Economopoulos, A. P. Dispersal of normal and irradiated laboratory strains and wild strains of the olive fly Dacus oleae in an olive grove. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 1976, 20, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Broumas, T. , Haniotakis, G., Liaropoulos, C., Tomazou, T., & Ragoussis, N. The efficacy of an improved form of the mass-trapping method, for the control of the olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae (Gmelin) (Dipt., Tephritidae): Pilot-scale feasibility studies. Journal of Applied Entomology, 2002, 126, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A. M. , & Jones, O. T. Alternative methods for controlling the olive fly Bactrocera oleae involving semiochemicals. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin, 2002, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

| Dates | 29-Jul | 5-Aug | 15-Aug | 22-Aug | 25-Aug | 1-Sep | 8-Sep | 15-Sep |

| Sex Ratio | 0.2:1 | 0.41:1 | 0.64:1 | 0.42:1 | 0.47:1 | 0.32:1 | 0.89:1 | 0.65:1 |

| Dates | 22-Sep | 29-Sep | 6-Oct | 13-Oct | 20-Oct | 27-Oct | 3-Nov | 10-Nov |

| Sex Ratio | 0.78:1 | 0.82:1 | 0.44:1 | 0.53:1 | 0.48:1 | 0.56:1 | 0.64:1 | 0.83:1 |

| Fruit Load Rate | Width | Length | Size |

| 50-75% | 1.11±0.11 | 1.78±0.24 | 1.98±0.36 b |

| 25-50% | 1.21±0.17 | 1.98±0.21 | 2.4±0.52 a |

| 0-25% | 1.18±0.2 | 1.97±0.24 | 2.34±0.57 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).