Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

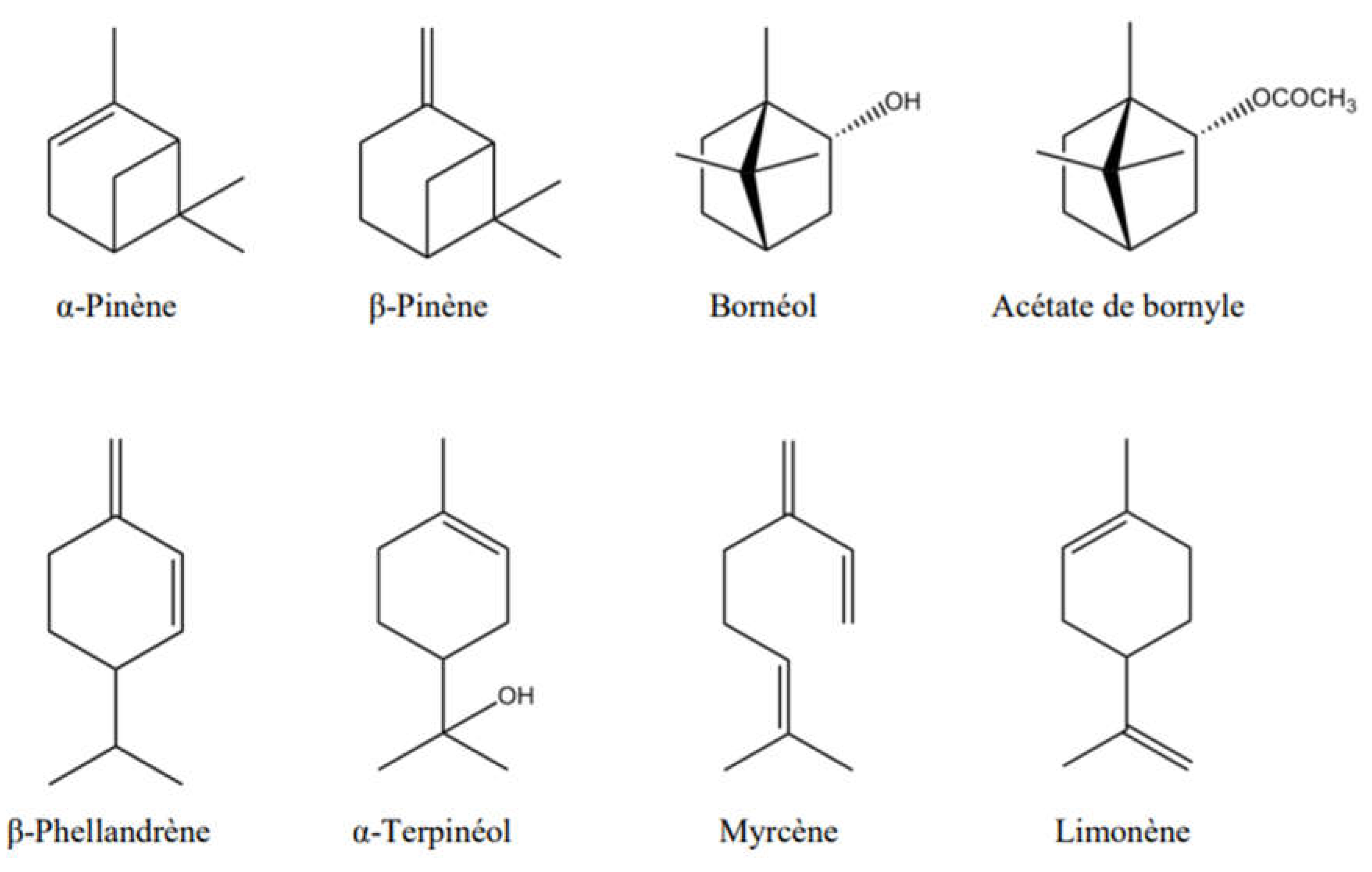

2. A brief description of Terpenes

3. Recent advances in Biotransformation of terpenes: study case of limonene and alpha pinene

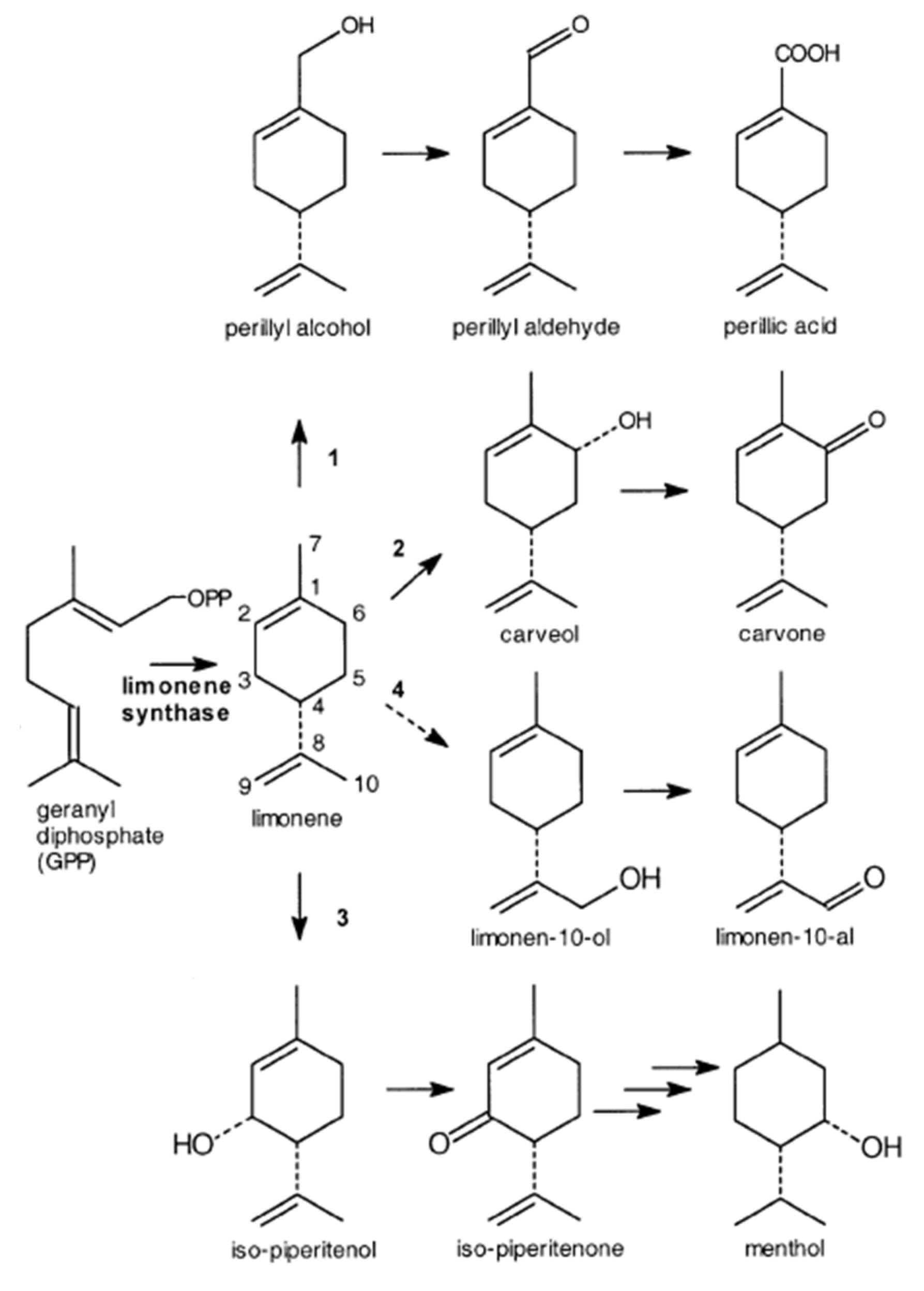

4. Limonene Biotransformation

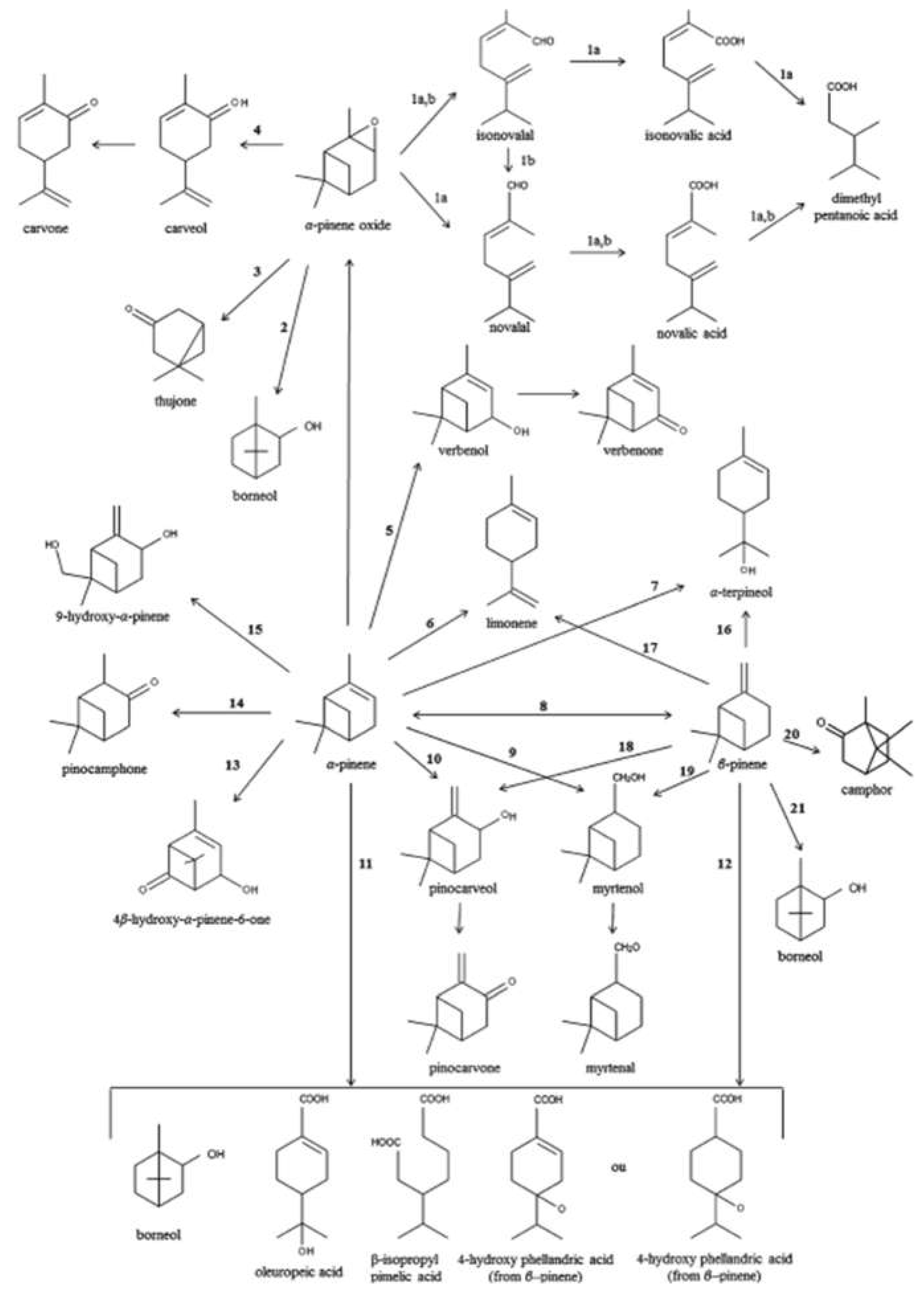

5. Biotransformation of α-Pinene

6. Avenues and approaches for improving the biotransformation of limonene and alpha pinene

6.1. Application of solid-state fermentation for biotransformation from filamentous fungi

6.2. Selection of Microorganisms

6.3. Pathways Production and Biotransformation of Terpenes

6.3.1. Bicyclic Monoterpenes

6.3.2. Monocyclic Monoterpenes

6.4. Improvements in physical pretreatment of wood and citrus residues

6.4.1. Pretreatment and conditioning

6.4.2. Thermal Pretreatment

6.4.3. Chemical Pretreatment

6.4.4. Biological Pre-Treatments

6.4.5. Extrusion

7. Existing Technology for Terpenes Extraction

7.1. Steam Distillation

7.2. Solvent Extractions

7.3. New Extraction Methods

7.3.1. Microwave-Assisted Extraction

7.3.2. CO2 Extraction or Supercritical Fluid Extraction

7.3.3. Subcritical Water Extraction

8. Conclusion

References

- Astani, A.; Reichling, J.; Schnitzler, P. Comparative study on the antiviral activity of selected monoterpenes derived from essential oils. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives 2010, 24, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.; Guerreiro, C.; Belo, I. Generation of flavors and fragrances through biotransformation and de novo synthesis. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2018, 11, 2217–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, Y. Biotechnology for the production of essential oils, flavours and volatile isolates. A review. Flavour and fragrance journal 2010, 25, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vespermann, K.A.; Paulino, B.N.; Barcelos, M.C.; Pessôa, M.G.; Pastore, G.M.; Molina, G. Biotransformation of α-and β-pinene into flavor compounds. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2017, 101, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicas, J.L.; Dionisio, A.P.; Pastore, G.M. Bio-oxidation of terpenes: an approach for the flavor industry. Chemical reviews 2009, 109, 4518–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, G.; Pessôa, M.G.; Bicas, J.L.; Fontanille, P.; Larroche, C.; Pastore, G.M. Optimization of limonene biotransformation for the production of bulk amounts of α-terpineol. Bioresource technology 2019, 294, 122180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessôa, M.G.; Vespermann, K.A.; Paulino, B.N.; Barcelos, M.C.; Pastore, G.M.; Molina, G. Newly isolated microorganisms with potential application in biotechnology. Biotechnology advances 2019, 37, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francezon, N.; Stevanovic, T. Chemical composition of essential oil and hydrosol from Picea mariana bark residue. BioResources 2017, 12, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Ke, Y.; Yu, R.; Yue, Y.; Amanullah, S.; Jahangir, M.M.; Fan, Y. Volatile terpenoids: multiple functions, biosynthesis, modulation and manipulation by genetic engineering. Planta 2017, 246, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tholl, D.; Bohlmann, J.; Pichersky, E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: a mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. The Plant Journal 2011, 66, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, P.S.; Zerbe, P. Terpene synthases as metabolic gatekeepers in the evolution of plant terpenoid chemical diversity. Frontiers in plant science 2019, 10, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadj Saadoun, J.; Bertani, G.; Levante, A.; Vezzosi, F.; Ricci, A.; Bernini, V.; Lazzi, C. Fermentation of agri-food waste: A promising route for the production of aroma compounds. Foods 2021, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenda, S.; Illner, S.; Mell, A.; Kragl, U. Industrial biotechnology—the future of green chemistry? Green Chemistry 2011, 13, 3007–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.R.; Molina, G.; Dionísio, A.P.; Maróstica Junior, M.R.; Pastore, G.M. The use of endophytes to obtain bioactive compounds and their application in biotransformation process. Biotechnology research international 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Felipe, L.; de Oliveira, A.M.; Bicas, J.L. Bioaromas–perspectives for sustainable development. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2017, 62, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Schempp, F.M.; Drummond, L.; Buchhaupt, M.; Schrader, J. Microbial cell factories for the production of terpenoid flavor and fragrance compounds. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2017, 66, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Vishvakarma, R.; Gautam, K.; Vimal, A.; Gaur, V.K.; Farooqui, A.; Varjani, S.; Younis, K. Valorization of citrus peel waste for the sustainable production of value-added products. Bioresource Technology 2022, 351, 127064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.J.; Beserra, F.P.; Souza, M.; Totti, B.; Rozza, A. Limonene: Aroma of innovation in health and disease. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2018, 283, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maróstica Júnior, M.R.; Pastore, G.M. Biotransformação de limoneno: uma revisão das principais rotas metabólicas. Química Nova 2007, 30, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, V.; Mancini, G.; Ruggeri, B.; Fino, D. Citrus waste as feedstock for bio-based products recovery: Review on limonene case study and energy valorization. Bioresource Technology 2016, 214, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Lomeli-Rodriguez, M.; Cara, P.D.; Lopez-Sanchez, J.A.; Pagliaro, M. Limonene: a versatile chemical of the bioeconomy. Chemical Communications 2014, 50, 15288–15296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, I.; Muthukumar, K.; Arunagiri, A. A review on the potential of citrus waste for D-Limonene, pectin, and bioethanol production. International Journal of Green Energy 2017, 14, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Sinha, M.; Cho, M.H. Citrus waste derived nutra-/pharmaceuticals for health benefits: Current trends and future perspectives. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 40, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Pahmeyer, M.J.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. Extraction and purification of d-limonene from orange peel wastes: Recent advances. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 177, 114484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongedijk, E.; Cankar, K.; Buchhaupt, M.; Schrader, J.; Bouwmeester, H.; Beekwilder, J. Biotechnological production of limonene in microorganisms. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2016, 100, 2927–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badee, A.; Helmy, S.A.; Morsy, N.F. Utilisation of orange peel in the production of α-terpineol by Penicillium digitatum (NRRL 1202). Food Chemistry 2011, 126, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, G.; Pinheiro, D.M.; Pimentel, M.R.; dos Ssanros, R.; Pastore, G.M. Monoterpene bioconversion for the production of aroma compounds by fungi isolated from Brazilian fruits. Food Science and Biotechnology 2013, 22, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Bhowal, J. Bioconversion of Mandarin Orange Peels by Aspergillus oryzae and Penicillium sp. Proceedings of Advances in Bioprocess Engineering and Technology: Select Proceedings ICABET 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Duetz, W.A.; Fjällman, A.H.; Ren, S.; Jourdat, C.; Witholt, B. Biotransformation of D-limonene to (+) trans-carveol by toluene-grown Rhodococcus opacus PWD4 cells. Applied and environmental microbiology 2001, 67, 2829–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, M.; Steuer, C. α-Pinene: A never-ending story. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimkhani, M.M.; Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Maham, M.; Jamshidi, A.; Kharazmi, M.S.; Dehnad, D.; Jafari, S.M. Extraction and purification of α-pinene; a comprehensive review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trytek, M.; Jędrzejewski, K.; Fiedurek, J. Bioconversion of α-pinene by a novel cold-adapted fungus Chrysosporium pannorum. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2015, 42, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, T.; De, B.; Bhattacharyya, D. Microbial oxidation of-pinene to (+)-a-terpineol by Candida tropicalis. 1999.

- Rottava, I.; Cortina, P.F.; Zanella, C.A.; Cansian, R.L.; Toniazzo, G.; Treichel, H.; Antunes, O.A.; Oestreicher, E.G.; de Oliveira, D. Microbial oxidation of (-)-α-pinene to verbenol production by newly isolated strains. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2010, 162, 2221–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadh, P.K.; Duhan, S.; Duhan, J.S. Agro-industrial wastes and their utilization using solid state fermentation: a review. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 2018, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafetto, L. Application of solid-state fermentation by microbial biotechnology for bioprocessing of agro-industrial wastes from 1970 to 2020: A review and bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bier, M.C.J.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Soccol, C.R. Biotransformation of limonene by an endophytic fungus using synthetic and orange residue-based media. Fungal biology 2017, 121, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baser, K.H.C.; Buchbauer, G. Handbook of essential oils: science, technology, and applications; CRC press: 2015.

- Zhao, L.-Q.; Sun, Z.-H.; Zheng, P.; He, J.-Y. Biotransformation of isoeugenol to vanillin by Bacillus fusiformis CGMCC1347 with the addition of resin HD-8. Process Biochemistry 2006, 41, 1673–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, D.; Ma, C.; Lin, S.; Song, L.; Deng, Z.; Maomy, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, B.; Xu, P. Biotransformation of isoeugenol to vanillin by a newly isolated Bacillus pumilus strain: identification of major metabolites. Journal of biotechnology 2007, 130, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallage, N.J.; Møller, B.L. Vanillin–bioconversion and bioengineering of the most popular plant flavor and its de novo biosynthesis in the vanilla orchid. Molecular plant 2015, 8, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, E.J.; Lin, G.-M.; Voigt, C.A.; Clardy, J. Bacterial terpene biosynthesis: challenges and opportunities for pathway engineering. Beilstein journal of organic chemistry 2019, 15, 2889–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmulla, R.; Harder, J. Microbial monoterpene transformations—a review. Frontiers in microbiology 2014, 5, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Day, D. Bacterial metabolism of α-and β-pinene and related monoterpenes by Pseudomonas sp. strain PIN. Process Biochemistry 2002, 37, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.; Felipe, L.d.O.; Bicas, J.L. Production, properties, and applications of α-terpineol. Food and bioprocess technology 2020, 13, 1261–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbor, V.B.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Berlin, A.; Levin, D.B. Biomass pretreatment: fundamentals toward application. Biotechnology advances 2011, 29, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischer, B.; Vendruscolo, R.G.; Wagner, R.; Menezes, C.R.; Barin, C.S.; Giacomelli, S.R.; Budel, J.M.; Barin, J.S. Effect of grinding method on the analysis of essential oil from Baccharis articulata (Lam.) Pers. Chemical Papers 2017, 71, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douville, J.; David, J.; Lemieux, K.M.; Gaudreau, L.; Ramotar, D. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae phosphatase activator RRD1 is required to modulate gene expression in response to rapamycin exposure. Genetics 2006, 172, 1369–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinprecht, L.; Pánek, M. Ultrasonic technique for evaluation of bio-defects in wood: Part 1–Influence of the position, extent and degree of internal artificial rots. International Wood Products Journal 2012, 3, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JUNG, C.G. Voies de traitements de déchets solides: valorisation matière et énergie. Bull. Sci. Inst. Natl. Conserv. Nat 2013, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Senneca, O.; Cerciello, F.; Russo, C.; Wütscher, A.; Muhler, M.; Apicella, B. Thermal treatment of lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose in nitrogen and carbon dioxide. Fuel 2020, 271, 117656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Ilyas, R.A.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Rani, M.S.A.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Shazleen, S.S. Chemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for the production of bioproducts: an overview. Applied Science and Engineering Progress 2021, 14, 588–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloutassi, N.; Louaste, B.; Boudine, L.; Remmal, A. Hydrolyse physico-chimique et biologique de la biomasse ligno-cellulosique pour la production de bio-éthanol de deuxième génération. Nature & Technology 2014, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Eloutassi, N.; Louaste, B.; Boudine, L.; Remmal, A. Valorisation de la biomasse lignocellulosique pour la production de bioéthanol de deuxième génération. Journal of Renewable Energies 2014, 17, 600–609. [Google Scholar]

- Motte, J.-C. Digestion anaérobie par voie sèche de résidus lignocellulosiques: Etude dynamique des relations entre paramètres de procédés, caractéristiques du substrat et écosystème microbien. Montpellier II 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Verma, P. An overview of key pretreatment processes employed for bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels and value added products. 3 Biotech 2013, 3, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Rehmann, L. Extrusion pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: a review. International journal of molecular sciences 2014, 15, 18967–18984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, A.; Manzanares, P.; Ballesteros, M. Extrusion as a pretreatment for lignocellulosic biomass: Fundamentals and applications. Renewable energy 2017, 114, 1427–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, D.; Koffi, E.; Ndao, A.; Peterson, E.C.; Rodrigue, D.; Adjallé, K. An Overview of Extrusion as a Pretreatment Method of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Energies 2022, 15, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djerrari, A. Influence du mode d'extraction et des conditions de conservation sur la composition des huiles essentielles de thym et de basilic. Montpellier 2, 1986.

- Cassel, E.; Vargas, R.; Martinez, N.; Lorenzo, D.; Dellacassa, E. Steam distillation modeling for essential oil extraction process. Industrial crops and products 2009, 29, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOUKHATEM, M.N.; FERHAT, A.; KAMELI, A. Méthodes d’extraction et de distillation des huiles essentielles: revue de littérature. Une 2019, 3, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Nutrizio, M.; Jambrak, A.R.; Munekata, P.E.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. A review of sustainable and intensified techniques for extraction of food and natural products. Green Chemistry 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-H.; Yusoff, R.; Ngoh, G.-C.; Kung, F.W.-L. Microwave-assisted extractions of active ingredients from plants. Journal of Chromatography A 2011, 1218, 6213–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornari, T.; Vicente, G.; Vázquez, E.; García-Risco, M.R.; Reglero, G. Isolation of essential oil from different plants and herbs by supercritical fluid extraction. Journal of Chromatography A 2012, 1250, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, M.; Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M.; Pourmortazavi, S.M.; Wysokowski, M.; Jesionowski, T.; Ehrlich, H.; Mirsadeghi, S. Supercritical fluid extraction of essential oils. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 118, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kayan, B.; Bozer, N.; Pate, B.; Baker, C.; Gizir, A.M. Terpene degradation and extraction from basil and oregano leaves using subcritical water. Journal of Chromatography A 2007, 1152, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinatoru, M. An overview of the ultrasonically assisted extraction of bioactive principles from herbs. Ultrasonics sonochemistry 2001, 8, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Q. Comparisons of microwave-assisted extraction, simultaneous distillation-solvent extraction, Soxhlet extraction and ultrasound probe for polycyclic musks in sediments: recovery, repeatability, matrix effects and bioavailability. Chromatographia 2011, 74, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, M.-E. Extraction Sans Solvant Assistée par Micro-ondes Conception et Application à l'extraction des huiles essentielles. Université de la Réunion, 2005.

| Essence | Parameters | Monoterpenes | Oxygenated monoterpenes | Sesquiterpenes | Esters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balsam fir | Concentration | 84.9% | 1.3% | 0.6% | 9.1% |

| major compound | α-Pinene | ||||

| β-pinene | α-Tepeniol | β-caraphyllene | Bornyl acetate | ||

| Limonene | |||||

| Black spruce | Concentration | 63.5% | 2.6% | β-caraphyllene | Bornyl acetate |

| major compound | α-Pinene | ||||

| β-pinene | α-tepeniol | ||||

| ϒ-3-carene | 1,8-cineole | ||||

| Jack pine | Concentration | 85.9% | 2.7% | 0.2% | 8.2% |

| major compound | α -pinene | α-tepeniol | α-tepeniol | Bornyl acetate | |

| camphene | 1,8-cineole | 1,8-cineole | |||

| Citrus terpenes | major compounds | Limonene 95% | |||

| α -pinene 2.5% | |||||

| camphene 2% | |||||

| β-myrcene 0.5% |

| MONOCYCLIC TERPENE SUBSTRATE | BIOTRANSFORMATION PRODUCT | EXAMPLE OF BIOCATALYST | CHEMICAL NAME | ODOUR | APPLICATION | REFERENCE |

| LIMONENE | α -Terpineol |

Pseudomonas fluorescens | p-Menth-1-en-8-ol | lilac | Antioxidant activity, Anti-inflammatory activity, Antimicrobial activity: Activity against A.niger, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Cytostatic and cytocidal effects towards Goetrichum citri-aurantii |

Bicas et al 2011; |

| Carveol | Rhodococcus opacus; Rhodococcus erythropolis PWD8; Pleurotus sapidus; Aspergillus cellulosae M-77 |

p-Mentha-6,8-dien-2-ol | spearmint | Flavouring agent; food additive | Duetz et al. 2001 |

|

| Carvone | Rhodococcus opacus; Rhodococcus eythropolis PWD8; Penicilium digitarium; Pleurotus sapidus |

p-mentha-1(6),8-dien-2-one | Mint aroma | Flavouring agent: flavour chewing gum and mint candies, provide aromas in personal-care products, air fresheners, and aromatherapy oils | Duetz et al. 2001 | |

| Perillic acid or perillyl alcohol | Pseudomonas putida DSM 12264; Aspergillus cellulosae M-77; Mycobacterium sp. HXN-1500; |

(4R)-4-prop-1-en-2-ylcyclohexene-1-carboxylic acid |

Exhibit antimicrobial properties; Ingredients in cleaning products ;Mosquito repellent when applied to the skin |

Duetz et al. 2001 | ||

| BICYCLIC MONOTERPENE | ||||||

| α-PINENE | Verbenol | Aspergillus niger | 4,6,6-Trimethyl-bicyclo(3.1.1)hept-3-en-2-one | Balsamic aroma | used in fragrance formulation of soft drinks, soups used as important intermediates in cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries used as flavour in food, such as in meats, sausages and ice cream used as material to synthesise chemicals, such as citral |

Toniazzo et al. 2005 |

| Verbenone | 4,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-3-one | minty spicy aroma | Used for insect control particularly against beetles as Dendroctonus frontalis; Used also in perfumery, aromatherapy, herbal teas and herbal remedies. The L-isomer is used as a cough suppressant under the name of levoverbenone. Verbenone may also have had antimicrobial properties. |

| Extraction methods | Principle | Advantages and disadvantages | References |

| Steam distillation | The forest or agricultural residue is in direct contact with steam, which is then condensed. Recovery takes place in a separator, where the volatile molecules are dispersed in water. | Méthode très simple Very simple method No energy expenditure, |

Vinatoru, 2001; [68] |

| Solvent extraction | The volatile molecules are separated from the solvent by evaporation of the solvent at high temperatures. | Efficient, slow and costly method Requires high temperatures (degradation of some constituents of volatile molecules) |

Hu, 2011; [69] |

| Hydrodistillation | The residual material is submerged in water, which is then heated to boiling point. After passing through the cooler, the mixture is collected in an essencier. | Efficient, but slow method for 100 g (4h) High water consumption |

Lucchesi, 2005; [70] |

| Supercritical fluid extraction | Extraction requires a supercritical fluid (CO2 in the presence of an organic solvent). | Efficient, low-cost method No oxidative degradation of lipids |

Boukhatem 2011 |

| Ultrasonic extraction | Sound waves exert vibrations on plant cell walls, improving extraction. | Reduced extraction time | Zheng et al. 2014 |

| Microwave extraction | The residual material is heated from the inside out, increasing the water pressure inside the cells and causing the cells to burst and spill their contents into the outside environment. | Environmental efficiency Fast method Saves time, water and residual solvent |

chan et al. 2011 |

| Hydrodistillation combined with microwaves | For 100 g of plant material, this method requires power (1200 watts) and duration 15 min | Good yield, fast (75 min), low cost | Chemat, 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).