1. Introduction

Asthma and bronchiectasis are often partners in a complex relationship although a clear causal relationship between the two entities is not well established. It is still unclear whether asthma can be a consequence of bronchiectasis or rather, bronchiectasis is an underlying cause of asthma, but when this liaison starts it has important clinical implications in terms of more frequent exacerbations, chronic infections, increased disease severity and related healthcare costs, and, finally, poor quality of life (QoL).

Bronchiectasis is present in 18-80% of patients affected by severe asthma [

1,

2,

3,

4], whereas asthma is apparently less frequent in patients with bronchiectasis and, according to the European bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC) this association can reach 30.5% when “self-reported” [

5,

7].

Both asthma and bronchiectasis are complex and heterogeneous diseases in terms of clinical manifestations and outcomes and deserve deep investigations for phenotyping and appropriate target therapy. The combination of these conditions compounds the clinical picture and requires a more in-depth analysis for an appropriate management.

While patients with bronchiectasis often self-report asthma, patients with severe asthma (SA) seldom know to have bronchiectasis [

8]. Despite the presence of symptoms that can lead to suspect bronchiectasis, such as recurrent exacerbations with pathogenic isolates from sputum, few times SA subjects undergo diagnostic tests for bronchiectasis.

Over the last few years, the importance of bronchiectasis in SA has been recognized and several case series have already been reported. For instance, a total of 696 patients from the Severe Asthma Network in Italy (SANI) registry were reviewed for co-presence of bronchiectasis and SA and the diagnosis of bronchiectasis was confirmed in 108 (15.5%, BE+) [

9].

Many studies have shown that the association of bronchiectasis and SA frequently occurs in older, non-atopic asthmatic subjects with more severe airway obstruction and higher rates of chronic expectoration and infection [

8]. Most of those patients exhibit low IgG, likely in consequence of chronic corticosteroid therapy or because of an unknown immune deficit [

8].

An increased awareness of the existence of a large group of severe asthmatics with bronchiectasis has resulted in a greater attention especially in specialized centers, and particularly in those dedicated to SA.

The aim of this study is to make a real-life overview of diagnostic workout in some SA centers scattered throughout the Italian territory in order to describe the level of attention given to investigation of bronchiectasis across these centers.

We compared 8 SA centers in terms of diagnostic and monitoring approaches to the study of SA and bronchiectasis at the time of enrollment (T0), at 6-month (T1), and 12- month follow -up visits (T2).

2. Materials and Methods

Population

92 patients, already diagnosed with non-CF and non-ASBA bronchiectasis, were enrolled retrospectively from 8 SA centers scattered throughout the Italian territory. Only patients with asthma and bronchiectasis diagnosed on chest CT were selected and patients with asthma without bronchiectasis were not included in the retrospective study. The SA centers of Siena, Bari, Foggia, Ferrara, Catania, Palermo, Naples, Milano, Rome and Reggio Emilia participated in this study.

Methods: All centers received a database fille out with clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic data of their patients at baseline (T0), after 6 (T1) and 12 months from enrolment (T2). From the different centers, clinical Features, comorbidities and chronic respiratory therapy were collected (Tab. N.1). Furthermore, each center reported diagnostic evaluations for both asthma and for bronchiectasis such as questionnaires of disease control, quality of life and prognostic scores performed at baseline, 6 months (T1) and 12 months (T2) of follow-up (Tab. 2).

In particular, anthropometric data, past clinical history and comorbidities, functional data (global lung function and bronchodilator reversibility testing), imaging tests (High Resolution Computed Tomography-HRCT), microbiological exams (sputum and broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) cultures), eatiological tests for bronchiectasis (alfa 1 antiTrypsine (A1AT) dosage, ciliary motility test, autoimmunity), endotyping tests for asthma (total IgE, Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide 50(FENO 50), Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide 350 (FENO 350), complete blood count (CBC), induced sputum cellularity, nasal cytology)) and questionnaires for asthma symptoms and quality of life (QoL) and Bronchiectasis (ASTHMA: Asthma Control Test (ACT) [

10], Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) [

11], Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) [

12], Test of the Adherence to Inhalers (TAI) [

13]; BRONCHIECTASIS: Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI) score[

14] and FACED [

15] (an acronym for Exacerbations, FEV1, Age, chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa bronchial infection Colonization, radiological Extension, and Dyspnoea) score) were collected.

This study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the “Riuniti” Hospital of Foggia (Institutional Review Board approval number 17/CE/2014), and all recruited patients gave their written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Nominal and dichotomous variables were expressed as %. Nominal variables were compared with Chi-square test and Mantel-Haenszel test. Significance levels of p <0.050 were assumed for all analyses. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 23 software.

3. Results

The median age of our study population was 58.8 ± 12.1 years. There were slightly more females than males (51.9%vs. 48.1%) and 70.4% of patients were nonsmokers.

Seventy-five percent of patients had family history of asthma and 69.1% of them were atopic. Most patients exhibited bilateral bronchiectasis in 79.5% and mono-lateral bronchiectasis in the remaining cases. Comorbidities were described in 88.9% of cases, being the most common rhinitis and nasal polyposis but gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was also very common (42%), followed by autoimmune diseases (14.6%), acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) sensitivity (12.2%), vasculitis (9.8%), and urticaria (9.8%) (see

Table 1).

All patients were on chronic therapy with LABA (Long-acting beta-adrenoceptor agonists) – ICS (Inhaled Corticosteroids) combination. Regarding inhaled corticosteroids, 56.6% of patients were on a moderate dose while the remaining 43.4% on a high dose. In addition, 72.5% of patients were on oral corticosteroids, 69.1% on long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), 33.8% on antileukotrienes, and 26.8% on mucolytics (N-acetylcysteine (NAC), carbocysteine).

Additionally, all patients were receiving biological therapy: 26 (32.1%) were given omalizumab, 31 (38.3%) mepolizumab, and 24 (29.6%) on benralizumab.

About 10% of patients performed regular physiotherapy and some with the help of cough assist device or incentive spirometer (1.2% each). Overall, the compliance to drug therapy was of 73.2%.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT OVER THE STUDY PERIOD (T0, T1, T2)

Table 2 reports the diagnostic tools used for the study of asthma and bronchiectasis at time T0, T1 and T2.

LUNG FUNCTION TESTS. Forced spirometry was performed in all patients at baseline (T0) but less at 6 and 12 months; similarly, Bronchodilator Reversibility Testing was done in most patients at baseline but usually not repeated over follow-up. Only a minority of patients underwent total lung capacity (TLC) and Diffusion (DLCO) tests.

RADIOLOGY. High-resolution computerized lungs of the lungs was performed in all patients at T0 time (100% at first visit and <5% at 6 and 12 months) showing bilateral bronchiectasis in almost 80% of cases (n, 73) and monolateral bronchiectasis in the remaining cases. Additionally, a minority of patients also underwent conventional chest X-ray at first visit (28.4%) or at follow-up (7-11% at 6 -12 months).

MICROBIOLOGY. Only a minority of patients performed a microbiological investigation of respiratory samples at baseline, being sputum cultured in less than 29.6% of cases and bronchoalveolar lavage cultured in only 10 patients; the same tests were only anecdotic at follow-up. When performed, the respiratory cultures were positive (Pseudomonas Aeruginosa or Haemophilus Influenzae )in 37% of cases at T0 and in 40% at T1.

ASTHMA ASSESSMENT (ENDOTYPING). At baseline 81.5% of patients underwent total IgE test, 63% complete blood count (CBC), 35.8% FENO50, 8.6% FENO350, 2.5% induced sputum, 28.4% nasal cytology. At follow-up (T1 and T2) only a minority of patients repeated these asthma-related tests, except for FeNO50% that was repeated in a similar percentage of cases over the study period (35-40%, overall). 10 patients underwent BAL.

ASTHMA SCORES. At baseline ACT score was performed in over 90% of cases and it was repeated in 68% and 62% of cases at T1 and T2. Both ACQ and AQLQ scores were used in a minority of cases at all time points. Compliance to therapy was assessed in the vast majority of patients (>80%) during the study.

BRONCHIECTASIS ASSESSMENT. At baseline less than 3% of all patients underwent ciliary motility test for primary ciliary dyskinesia and only 17.3% of all patients underwent AAT dosage to investigate a potential AAT deficit. About 20% of all patients were tested for autoimmune markers, being ANA and ANCA positive in 7.4%. None of the patients did any specific diagnostic test for bronchiectasis during follow-up.

BRONCHIECTASIS SCORES. Specific prognostic scores were used only in a minority of cases at baseline, being BSI used in 37% and FACED in 10% of patients, respectively. Less than 10% of patients repeated the assessment of prognostic scores at follow-up.

COMPARISON ACROSS THE CENTERS

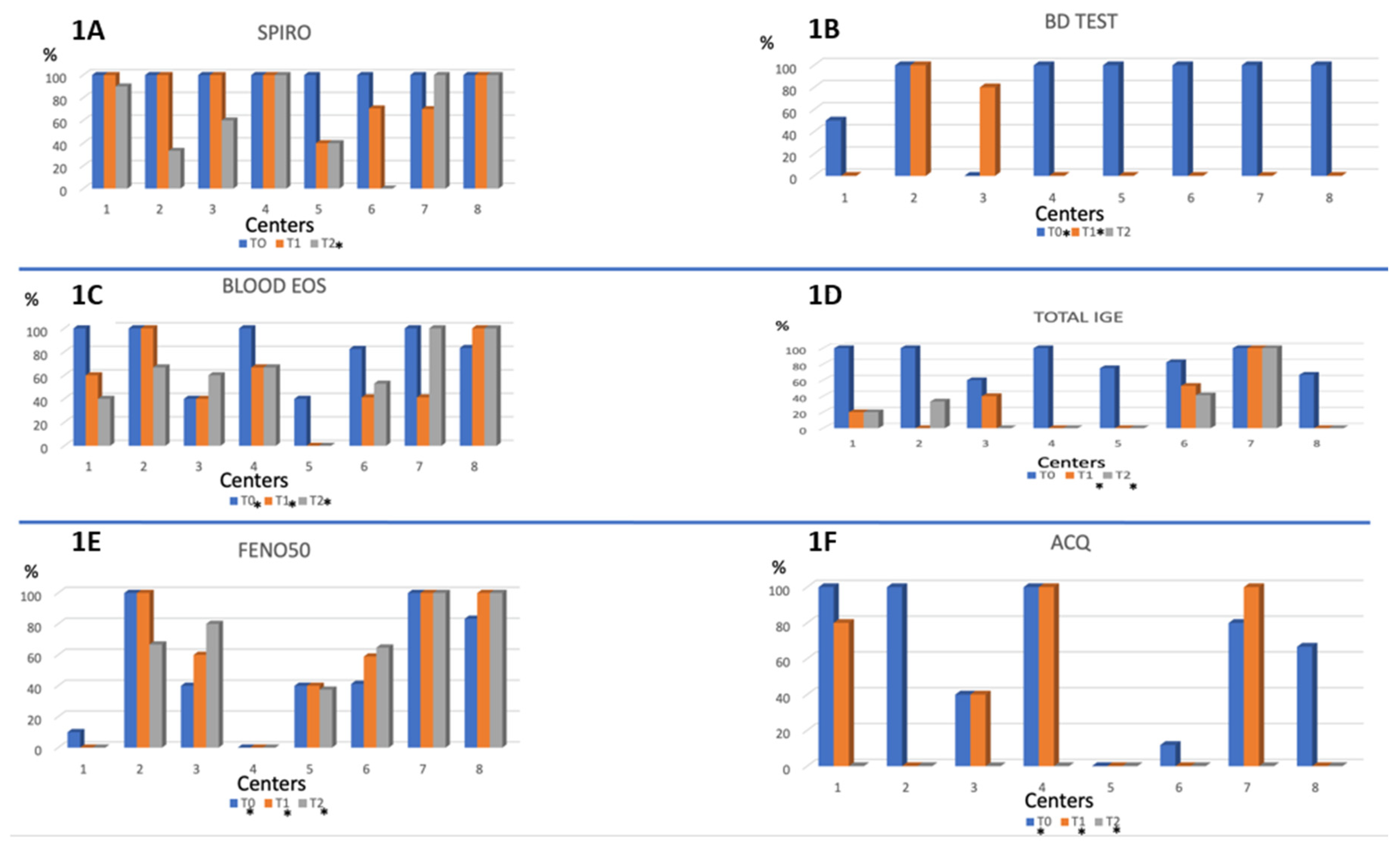

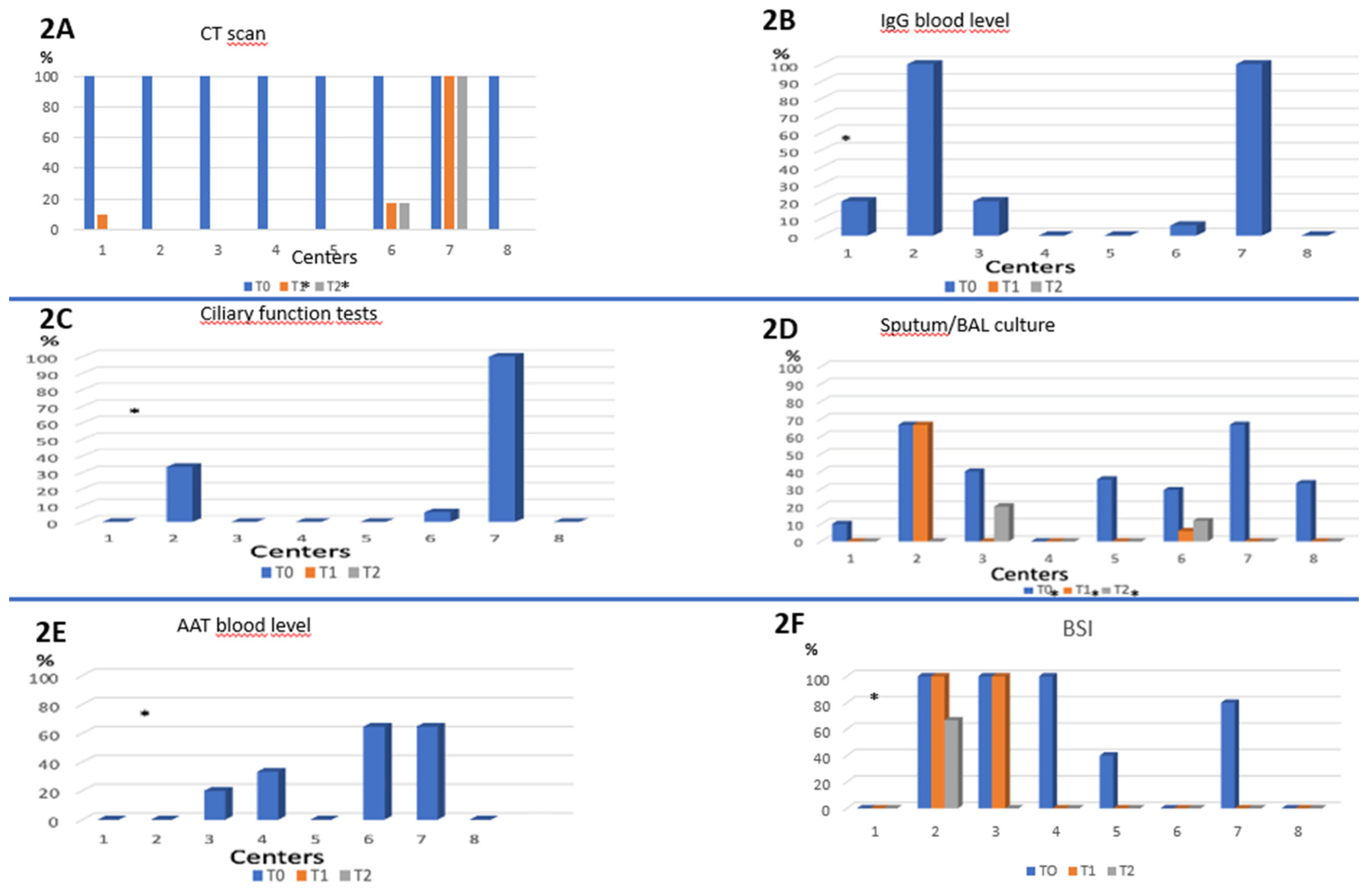

At each time point, the different centers were compared in terms of performance of the different diagnostic tools, as shown in the Figure 2 and 3. Overall, a heterogeneous diagnostic approach emerges across the Centers under study.

With regards to asthma assessment, clearly most centers perform a complete evaluation at baseline including spirometry (100% of cases), bronchodilatation test (50 to 100%) blood eosinophils (40 to 100%) and IgE levels (60 to 100%), and, in a more variable proportion FENO50 (0 to 100%) and ACQ questionnaire (0 to 100%) (

Figure 1).

Very differently, the assessment of Bronchiectasis was extremely heterogeneous and incomplete in most cases (

Figure 2). At baseline CT scan was performed in all centers as per inclusion in the study. IgG blood level and ciliary function were performed in only 2 out of 8 centers (100% of patients) while AAT blood level was performed sporadically only 4 centers. Similarly, a huge variability was detected in the performance of sputum culture across different centers (range 0 to 66.7%). Furthermore, when performed, the sputum culture was positive at T0 in 37% of cases (Figure n.2) and remained positive in 40% of cases at 6-month visit, suggesting potential chronic infections and/or inadequate treatment.

Follow-up visits (T1 and T2) did not include any further evaluation specific to bronchiectasis disease.

Figure 1 Asthma evaluation tests across centers (T0, T1, T2).

Figure 1.

Performance of the different tests or questionnaire for asthma evaluation across the different centers participating in the study. 1A: Spirometry; 1B: Bronchodilator test; 1C: blood eosinophil count; 1D: blood level of Total IgE; 1E: FeNO50; 1F: ACQ. Abbreviations: BD test: bronchodilator reversibility test; FeNO: exhaled nitric oxide; ACQ: Asthma control questionnaire; Spiro: spirometry; Blood eos: blood eosinophilia. *= Presence of statistically significant difference between the different centers at a particular time T (T0 and/or T1 and/or T2).

Figure 1.

Performance of the different tests or questionnaire for asthma evaluation across the different centers participating in the study. 1A: Spirometry; 1B: Bronchodilator test; 1C: blood eosinophil count; 1D: blood level of Total IgE; 1E: FeNO50; 1F: ACQ. Abbreviations: BD test: bronchodilator reversibility test; FeNO: exhaled nitric oxide; ACQ: Asthma control questionnaire; Spiro: spirometry; Blood eos: blood eosinophilia. *= Presence of statistically significant difference between the different centers at a particular time T (T0 and/or T1 and/or T2).

Figure 2 Bronchiectasis evaluation tests across centers (T0, T1, T2).

Figure 2.

Performance of the different tests or questionnaire for evaluation of bronchiectasis across the different centers participating in the study. 2A: CT scan; 2B: IgG blood level; 2C: ciliary function tests; 2D: Sputum/BAL culture; 2E: execution of AAT blood level; 2F: execution of the BSI questionnaire. Abbreviations: CT scan: computed tomography scan; BAL: Broncho-Alveolar Lavage; AAT: : α₁antitrypsine; BSI: Bronchiectasis Severity Index. *=Presence of statistically significant difference between the different centers in that particular time period T (T0 and / or T1 and / or T2).

Figure 2.

Performance of the different tests or questionnaire for evaluation of bronchiectasis across the different centers participating in the study. 2A: CT scan; 2B: IgG blood level; 2C: ciliary function tests; 2D: Sputum/BAL culture; 2E: execution of AAT blood level; 2F: execution of the BSI questionnaire. Abbreviations: CT scan: computed tomography scan; BAL: Broncho-Alveolar Lavage; AAT: : α₁antitrypsine; BSI: Bronchiectasis Severity Index. *=Presence of statistically significant difference between the different centers in that particular time period T (T0 and / or T1 and / or T2).

4. Discussion

The association between asthma and bronchiectasis has recently attracted increasing interest probably because bronchiectasis is one of the comorbidities with major impact on asthma severity and a real clinical challenge. The latest document of Global initiative for Asthma [

16], states that the primary goal for achieving control of asthmatic patients is based on identification and management of comorbidities, including bronchiectasis [

17]. For this reason, we described for the first time how pulmonologists from eight Italian Centers for severe asthma, use to manage patients affected by severe asthma and bronchiectasis.

The main results of the present study are the following:1) In severe asthma patients the presence of bilateral bronchiectasis is common; 2) Despite this, the assessment of bronchiectasis is extremely poor or heterogeneous; 3) unlike for asthma, follow-up of bronchiectasis is extremely poor.

The presence of bronchiectasis in patients with severe asthma has already been described by different authors worldwide. From an epidemiological point of view this association has been described in 35.2% [

18] to 67.5% of all cases of severe asthma [

4]. According to the “Severe Asthma Network Italy” (SANI) Registry 15.5% of severe asthmatic patients have a clinical-radiological diagnosis of bronchiectasis, a percentage that climbs to 25–40% in other case series [

19,

20]. In other words, at least one third of the patients with severe asthma have bronchiectasis and the coexistence of the two conditions clearly has significant clinical implications that result in a high social and economic burden in terms of health care. Moreover, if unrecognized, this coexistence is likely to result in therapeutic failure and worsening of symptoms with more frequent or more severe exacerbations, a greater disease progression and higher healthcare costs [

21]. In our study only SA patients with known bronchiectasis were included and a prevalence of bronchiectasis in the overall population of patients from these centers cannot be estimated but 80% of them had bilateral bronchiectasis indicating broad extension of the disease and a considerable potential impact. Assuming the prevalence rate of 15 to 40% of bronchiectasis in SA patients as reported elsewhere, it is likely that a considerable number of patients with SA might have not diagnosed of bronchiectasis due to lack of suspicion yet.

Additionally, despite the clear presence of bronchiectasis at CT scan most centers did not perform a complete aetiological investigation in these patients. A reason for this could be the lack of knowledge or awareness of the clinical relevance of this workflow among asthma experts. In fact, some patients could have underlying conditions that require a specific intervention: this is the case of immunodeficiencies or primary ciliary dyskinesia or cystic fibrosis that could easily have clinical and functional manifestations of asthma. A specific therapy, such as IgG replacement or CFTR modulators, can eventually drastically improve outcomes and prognosis of these patients. It is for this reason that all the current guidelines [

6] for bronchiectasis suggest completing the aetiological investigation of bronchiectasis, but it is likely that the spread of these recommendations is still insufficient among physicians not expert in the field of respiratory infections and bronchiectasis.

Another potential reason for not performing a complete investigation of bronchiectasis is the general belief that these bronchial alterations are a natural consequence of prolonged airways inflammation due to asthma. However today there is no evidence to support this hypothesis. In fact, bronchiectasis resulting from respiratory infections (such as pneumonia or NTM) or other etiologies such as immunodeficiencies or CF or PCD could facilitate bronchial hyper-responsiveness and development of asthma in some cases such as in presence of atopy. Boyton et al. suggested that the cyclical presence of inflammation, infection and/or antibiotic therapy in patients with bronchiectasis could disrupt the fragile balance of the lung microbial ecosystem, creating a dysfunctional microbiota. This would cause excessive activation of the Natural Killer cells, creating a high level of bacterial lung infection [

22]. The presence of a pro-inflammatory background caused by bronchiectasis could lead to serious problems to control asthma.

On the other hand, severe asthma could lead to airways damage including the development of bronchiectasis. Crimi et al. [

23], suggest the existence of a direct causal link between the 2 diseases mediated by mucus and inflammation. These authors hypothesize that in presence of stagnant mucus, pathogens at small airways level and a lower activity of phagocytosis, as usally described in asthmatic patients, bronchiectasis could develop through a vicious circle like the ‘Cole’ one but characterized by eosinophilic inflammation as primum movens for bronchial remodeling [

24,

25].

Ideally future long-term longitudinal studies will be able to demonstrate if these hypotheses are valid or not but at the present time, we should possibly consider both possibilities as plausible although clinical implications in term of prevention of disease progression are not clear. While follow-up of asthma is well characterized in all patients and similarly across the different centers in the study, the follow-up of bronchiectasis is extremely poor.

In fact, great attention was directed to inflammation as attested by the broad use of systemic inflammatory markers (CRP, WCC and ESR) and FENO at all time points; in contrast the investigation of potential bronchial infections was insufficient. The performance of sputum culture across the centers was indeed lower than expected, extremely heterogeneous and discontinuous over follow-up. The presence of potential pathogenic microorganisms is very common in asthma patients with usual productive cough and mucopurulent sputum [

4,

26]. In particular, the repeated isolation of Haemophilus influenzae, and, even worse, of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can attest the presence of chronic bronchial infection and worse clinical outcomes. In fact, more exacerbations, lower lung function, worse quality of life and life expectancy can be expected in respiratory patients with this kind of infections [

27,

28,

29]. Unfortunately, there is no consensus definition of association between asthma and bronchiectasis yet and therefore no clear therapeutic recommendations have been provided. Possibly this is the main reason of insufficient microbiological investigation in asthma patients. In addition, the use of inhaled antibiotics, recommended in some bronchiectasis patients, cannot be easily adopted in SA patients, due to usual patient’ intolerance.

More in general, the best therapeutic management of asthma patients with bronchiectasis is still to be elucidated; for instance, the high doses of inhaled corticosteroids required for the management of severe asthma, are theoretically associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory infections [

1] and conceptually associated with asthma exacerbation, thus creating a real vicious circle. So, stopping the use of oral corticosteroids is a priority in patients with asthma and bronchiectasis, especially in the more critically ill patients with severe asthma, anticipating, where possible, the stp up with biologicals. This approach become more interesting today in the light of the identification of super-responders to biologicals that, according to the definition of Upham et al., are astmatics that can reach an exceptional levels of asthma control until a more ambitious remission of the disease [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Often, those super responders patients, present other comorbidities TH2 as well as nasal poliposis or bronchiectasis that need to be taken in consideration in the clusterization of asthmatic patients that is crucial to make precision medicine [

34]

However, if phenotyping of asthma is considered fundamental for appropriate therapy, as demonstrated by the large use of specific tests questionnaires and biologic treatments in these patients, relatively poor knowledge is available in bronchiectasis; in fact, almost none of the patients received appropriate therapy or follow-up for bronchiectasis. Only in the last 2 years research has approached more seriously the biological characterization of inflammation in bronchiectasis. Indeed, Chalmers et al. have just published a manuscript certifying the existence of about 20% of bronchiectasis patients with eosinophilic inflammation that could benefit from specific drugs [

35]. Similarly, different drugs are being tested to contrast excessive neutrophilic inflammation [

36].

In summary, despite the increasing scientific interest in this topic, the present study confirms that there is no adequate diagnostic flowchart and management of bronchiectasis in patients with asthma. Moreover, no consensus does exist today on the most appropriate clinical approach and, in clinical practice the management of asthma associated with bronchiectasis is highly heterogeneous. For all these reasons we consider that further efforts are required to improve awareness of the role of bronchiectasis in asthma and to achieve consensus and evidence-based recommendations for this challenging clinical entity.

Author Contributions

All authors are responsible for all content of the manuscript. All were involved in acquisition, analysis, and/or interpretation of the data presented in the manuscript, as well as critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved submission of the final version of the manuscript, and all agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the submitted work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the “Riuniti” Hospital of Foggia (Institutional Review Board approval number 17/CE/2014), and all recruited patients gave their written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Claudia Crimi, Sebastian Ferri, and Nunzio Crimi: “Bronchiectasis and asthma: a dangerous liaison?” Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, Vol 19, Num. 1, Febbraio 2019.

- Park JW, Hong YK, Kim CW et al. : “High-resolution computed tomography in patients with bronchial asthma: correlation with clinical features, pulmonary functions and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1997;7:186–192.

- Paganin F, Seneterre E, Chanez P, et al. : “ Computed tomography of the lungs in asthma: influence of disease severity and etiology” Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:110–114. [CrossRef]

- Dimakou K, Gousiou A, Toumbis M, et al. “Investigation of bronchiectasis in severe uncontrolled asthma”. Clin Respir J 2018; 12:1212–1218). 1: Clin Respir J 2018; 12.

- Polverino E, Paggiaro P, Aliberti S, et al.: “Self-reported asthma as a co-morbidity of bronchiectasis in the EMBARC registry” Abstract Book - Second World Bronchiectasis Conference Milan, 6-8 July 2017. www.worldbronchiectasis-conference.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/AbstractBook_WEB.pdf. Date last accessed: July 22, 2018. 8 July.

- Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700629. [CrossRef]

- Porsbjerg C, Menzies-Gow A. : “ Co-morbidities in severe asthma: clinical impact and management”. Respirology 2017; 22: 651–661.

- Eva Polverino, Katerina Dimakou, John Hurst et al. “The overlap between bronchiectasis and chronic airway diseases: state of the art and future directions” European Respiratory Journal 2018 52: 1800328.

- Heffler, “Clinical features associated with a doctor-diagnosis of bronchiectasis in the Severe Asthma Network in Italy (SANI) registry” Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine, Manuscript ID ERRX-2020-ST-0102.R1.

- Mike Thomas , Stephen Kay, James Pike, Angela Williams, Jacqueline R Carranza Rosenzweig, Elizabeth V Hillyer, David Price. The Asthma Control Test (ACT) as a predictor of GINA guideline-defined asthma control: analysis of a multinational cross-sectional survey. Prim Care Respir J . 2009 Mar;18(1):41-9. [CrossRef]

- Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(4):902-907. [CrossRef]

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 1992;47(2):76-83. [CrossRef]

- Vicente Plaza, Concepción Fernández-Rodríguez, Carlos Melero, Borja G. Cosío, Luís Manuel Entrenas, Luis Pérez de Llano, Fernando Gutiérrez-Pereyra, Eduard Tarragona Rosa Palomino, MSc and Antolín López-Viña, on behalf of the TAI Study Group. Validation of the ‘Test of the Adherence to Inhalers’ (TAI) for Asthma and COPD Patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2016 Apr 1; 29(2): 142–152. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, et al. The bronchiectasis severity index. An international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 576–585. [CrossRef]

- Martınez M, Gracia J, Vendrell M, Giron R, Maiz L, Carrillo D, et al. Multidimensional approach to BQNFQ the FACED score. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1357-67.

- “Diagnosis and management of difficult-to-treat and severe asthma”, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention 2019; Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org.GINA 2019.

- Israel E, Reddel HK. “Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults”. N Engl JMed 2017; 377:965–976. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Nam Jin K, Cho SH, et al. “Severe asthma phenotypes classified by site of airway involvement and remodeling via chest CT scan”. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2018; 28:312–320. 3: J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2018; 28, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bisaccioni C, Aun MV, Cajuela E, et al. “Comorbidities in severe asthma: frequency of rhinitis, nasal polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, vocal cord dysfunction and bronchiectasis”. Clinics 2009; 64: 769–73.

- Gupta S, Siddiqui S, Haldar P, Raj JV et al. “Qualitative analysis of high-resolution CT scans in severe asthma”. Chest 2009;136: 1521–8. [CrossRef]

- Coman I, Pola-Bibian B, Barranco P, et al. Bronchiectasis in severe asthma: clinical features and outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 120:409–413. 4: Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 120.

- R J Boyton, C J Reynolds, K J Quigley et al. : “Immune mechanisms and the impact of the disrupted lung microbiome in chronic bacterial lung infection and bronchiectasis”, Clin Exp Immunol. 2013 Feb; 171(2): 117–123.). [CrossRef]

- Crimi C., Ferri S., Campisi R., Crimi N. The Link between Asthma and Bronchiectasis: State of the Art. Respiration 2020;99:463–476. [CrossRef]

- Liang Z, Zhang Q, Thomas CM, Chana KK, Gibeon D, Barnes PJ, et al. Impaired macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria in severe asthma. Respir Res. 2014 Jun;15(1):72. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Illing R, Hui CK, Downey K, Carr D, Stearn M, et al. Bacteria in sputum of stable severe asthma and increased airway wall thickness. Respir Res. 2012 Apr;13(1):35. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Galo A, Olveira C, Fernández de Rota-Garcia L. et al. Factors associated with bronchiectasis in patients with uncontrolled asthma; the NOPES score: a study in 398 patients. Respir Res. 2018 Mar;19(1):43.

- Araújo D, Shteinberg M, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, Hill AT, Fardon TC, Obradovic D, Stone G, Trautmann M, Davis A, Dimakou K, Polverino E, De Soyza A, McDonnell MJ, Chalmers. The independent contribution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection to long-term clinical outcomes in bronchiectasis. JD.Eur Respir J. 2018 Jan 31;51(2):1701953. [CrossRef]

- McDonnell MJ, Jary HR, Perry A, MacFarlane JG, Hester KL, Small T, Molyneux C, Perry JD, Walton KE, De Soyza A. Non cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: A longitudinal retrospective observational cohort study of Pseudomonas persistence and resistance. Respir Med. 2015 Jun;109(6):716-26. Epub 2014 Aug 29. [CrossRef]

- M R Loebinger , A U Wells, D M Hansell, N Chinyanganya, A Devaraj, M Meister, R Wilson. Mortality in bronchiectasis: a long-term study assessing the factors influencing survival. Eur Respir J. 2009 Oct;34(4):843-9. Epub 2009 Apr 8. [CrossRef]

- Upham JW, Le Lievre C, Jackson DJ, Masoli M, Wechsler ME, Price DB, et al. Defining a severe asthma super-responder: findings from a Delphi process. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9:3997-4004. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh JE, d’Ancona G, Elstad M, Green L, Fernandes M, Thomson L, et al. Real-world effectiveness and the characteristics of a "super-responder" to mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest 2020;158:491-500. [CrossRef]

- Bagnasco D, Brussino L, Bonavia M, Calzolari E, Caminati M, Caruso C, D'Amato M, De Ferrari L, Di Marco F, Imeri G, Di Bona D, Gilardenghi A, Guida G, Lombardi C, Milanese M, Nicolini A, Riccio AM, Rolla G, Santus P, Senna G, Passalacqua G. Efficacy of Benralizumab in severe asthma in real life and focus on nasal polyposis. Respir Med. 2020 Sep;171:106080. Epub 2020 Jul 3. [CrossRef]

- Harvey ES, Langton D, Katelaris C, Stevens S, Farah CS, Gillman A, et al. Mepolizumab effectiveness and identification of super-responders in severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2020;55:1902420. [CrossRef]

- Rupani H, Hew M. Super-Responders to Severe Asthma Treatments: Defining a New Paradigm. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 Nov;9(11):4005-4006. [CrossRef]

- Shoemark A, Shteinberg M, De Soyza A, Haworth CS, Richardson H, Gao Y, Perea L, Dicker AJ, Goeminne PC, Cant E, Polverino E, Altenburg J, Keir HR, Loebinger MR, Blasi F, Welte T, Sibila O, Aliberti S, Chalmers. Characterization of Eosinophilic Bronchiectasis: A European Multicohort Study. JD.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Apr 15;205(8):894-902. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James D Chalmers , Charles S Haworth , Mark L Metersky , Michael R Loebinger , Francesco Blasi , Oriol Sibila , Anne E O'Donnell , Eugene J Sullivan , Kevin C Mange , Carlos Fernandez Jun Zou , Charles L Daley. Phase 2 Trial of the DPP-1 Inhibitor Brensocatib in Bronchiectasis WILLOW Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 26;383(22):2127-2137. Epub 2020 Sep 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Clinical features, comorbidities and chronic respiratory therapy.

Table 1.

Clinical features, comorbidities and chronic respiratory therapy.

| Clinical Features |

|---|

| Female |

51.9% |

| Former smoker |

22.2% |

| Current smoker |

7.4% |

| Family History of Asthma |

75% |

| Atopy |

69.1% |

| Bilateral Bronchiectasis |

79.5% |

| Chronic bronchial Infection by P. Aeruginosa |

2.4% |

| NMT colonization |

0.0% |

| TBC |

0.0% |

| Comorbidities (88.9% of all patients) |

| Rhinitis |

63.1% |

| Nasal polyposis |

61.7% |

| Rhinosinusitis |

50.0% |

| GERD |

42.0% |

| Autoimmune disease |

14.6% |

| ASA intolerance |

12.2% |

| Vasculitis |

9.8% |

| Urticaria |

9.8% |

| OSAS |

7.3% |

| Dermatitis |

7.3% |

| Cystis Fibrosis |

0.0% |

| Infertility |

0.0% |

| Home Therapy |

| ICS-LABA |

100% |

| LAMA |

72.5% |

| OCS |

69.1% |

| Moderate dose ICS |

56.6% |

| High dose ICS |

43.4% |

| Anti-LTRE |

33.8% |

| Mucolytics |

26.8% |

| Omalizumab |

32.1 % |

| Mepolizumab |

38.3% |

| Benralizumab |

29.6 % |

Table 2.

Diagnostic evaluations and questionnaires of disease control, quality of life and prognostic scores performed at baseline, 6 months (T1) and 12 months (T2) of follow-up.

Table 2.

Diagnostic evaluations and questionnaires of disease control, quality of life and prognostic scores performed at baseline, 6 months (T1) and 12 months (T2) of follow-up.

| LUNF FUNCTION TESTS |

|---|

| |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

| Spirometry % |

100.0 |

64.2 |

43.0 |

| Bronchodilator Reversibility Testing % |

64.3 |

17.1 |

0.0 |

| TLC % |

16.7 |

21.0 |

0.0 |

| DLCO % |

16.0 |

13.6 |

8.9 |

| RADIOLOGY |

|

|

|

| Chest X-ray % |

28.4 |

7.4 |

11.1 |

| Chest CT scan % |

100.0 |

4.9 |

3.7 |

| MICROBIOLOGY |

|

|

|

| Sputum culture, % |

29.6 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

| BAL culture, % |

11.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| LABORATORY DIAGNOSTICS |

|

|

|

| Hemochrome % |

63.0 |

27.2 |

27.2 |

| Blood eosinophilia % |

63.0 |

27.2 |

27.2 |

| Sputum eosinophilia % |

2.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Total IgE % |

81.5 |

16.0 |

12.3 |

| Nasal cytology % |

28.4 |

0.0 |

2.5 |

| ESR % |

8.6 |

8.6 |

0.0 |

| CRP % |

50.6 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

| ANA, ANCA % |

20.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| FRACTIONAL EXHALED NITRIC OXIDE (FENO) TEST |

|

|

|

| FeNO50 % |

35.8 |

39.5 |

39.5 |

| FeNO350 % |

8.6 |

16.0 |

9.9 |

| OTHER DIAGNOSTIC TOOLS |

|

|

|

| A1AT genotyping % |

17.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Ciliary motility test % |

2.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| QUESTIONNAIRES |

|

|

|

| ACT % |

90.1 |

67.9 |

61.7 |

| ACQ % |

28.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| AQLQ % |

21.0 |

19.8 |

25.9 |

| Compliance to therapy % |

96.3 |

97.6 |

82.5 |

| |

|

|

|

| BSI % |

37.0 |

11.0 |

8.6 |

| FACED score % |

9.9 |

0.0 |

7.4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).