1. Introduction

Health and Wellness is one of the Sustainable Development Goals that according to the 2016-2030 agenda The United Nations Organization approved to ensure a healthy life and promote the well-being of all at all ages for the construction of prosperous societies. In this sense and within the purposes that Higher Education Institutions have is to activate processes of intervention promotion in groups of vulnerability with the purpose of contributing to society with plans and interventions to improve each human process that generates a healthy life allowing to decrease physical and psychological diseases that increase higher rates of inequalities. One of the age groups that are within the group of vulnerability in the development of Health and Wellness are people over 65 years old. Both in Latin America and in European countries, studies have been conducted to observe psychological well-being at this stage of life (Bukov et al., 2002; Schwingel et al., 2009) and especially analyzing the role of social interaction in gerontological centers (Ferrand et al., 2014; Van Willingen, 2000).According to studies, it can be indicated that group dynamics can contribute to the development of psychological mechanisms that activate thoughts based on the contribution we give to the group and what we receive from it (Rubio L. et al., 2016). It is also suggested that for adults to carry out an optimal aging process they must remain active in their social relationships (Ferrand et al., 2014; La Guardia et al., 2000).

The United Nations General Assembly named the period 2021-2030 as the "Decade of Healthy Aging" from this the WHO leads shared mechanisms with various actors such as professionals, academia, media and governments to undertake efforts for actions that can promote longer and concerted lives (World Health Organizational , 2022). Prior to this, in 2017 the United Nations Organization registered approximately 962 million people over 60 years of age. According to studies, it is projected that in 2050 this figure will double to 2.1 billion and in 2100 it will triple to 3.1 billion (United Nation, 2017).

Globally, the aging rate has become an indicator of demographic structure by age. In the Latin American region, Chile is the most aged country, with 61 older adults for every 100 people under 15 years of age. The least aged country is Bolivia with 22 older adults for every 100 people under 15 years of age. In Ecuador, 7% of its inhabitants are over 65 years old, but by 2025 it will exceed 10%, which will place it among the countries with an aging population (INEC, 2017). In this sense Ecuador ranks fourth in Latin America with the highest level of aging. This result could indicate that life expectancy is increasing at the same time that the number of births is decreasing (Inclusión, 2019).

The Decade of Healthy Aging aims to mitigate the effects of aging on the older adult population. Since this age group is considered as an age group that presents high vulnerability indexes characterized by indicators of loneliness, cognitive and physical deterioration (Sentandreu-Mañó et al., 2022; Palomo-Vélez et al., 2020). In addition, stress, such as depression can cause disease or worsen it as it has been shown that high stress index can cause problems in the immune system (Dávila Hernándeza y González González, 2016).

On the contrary, positive emotions can cause well-being, the feeling of joy can generate improvement in certain pathologies or avoid them in adulthood (Alexander et al., 2021); In this sense the theories of perceived isolation, the need for social connection is an intensely rooted human particularity that has developed from different neural, hormonal and genetic mechanisms directly related to the social bond, the companionship that is crucial to ensure survival in life (Santini et al., 2020).

Social connection can generate positive emotions but as people advance in age, they may experience the physical absence of family and friends in various areas of life thus reducing social interaction (Charles y Cartensen, 2010) these experiences can produce loneliness which is considered a major health problem (Freedman y Nicolle, 2020) loneliness, in the older adult, can become a negative factor that impacts all dimensions of psychological well-being; but even more, loneliness, becomes a predictive component in difficulties in autonomy and pleasure (Sancho et al., 2022). On the other hand, socialization may increase with age (Cornwell et al., 2008), likewise socialization promotes active and healthy aging (Turcotte et al., 2018). Social Participation is related to significant associations with self-rated health and life satisfaction regardless of variables such as gender, age and socioeconomic status (Dawson-Townsend, 2019).

Different studies indicate that psychological well-being has yielded in recent years considerable theoretical and empirical development; (Sharifian y Grühn, 2018) as satisfaction with body and mind favors in older people an active attitude in everyday life and a sense of feeling needed (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn y Kotter Grühn, 2008; Borglin et al., 2005). As older adults perceive their lives as meaningful and purposeful they develop greater longevity (Tymoszuk et al., 2020), better physical and mental health, as well as higher social engagement (Jia R.-x. et al., 2019); among other prse suggests people "should adopt physical activity and exercise to alleviate the negative impact of aging on their cognitive function" (Jia et al., 2019).

Berk's (2001) research has shown that humor produces psychological and physiological effects similar to aerobic exercise, likewise he mentions in the study by Law et al., (2018) that laughter has similar effects. In addition, an indicator of well-being is physical activity, which becomes a component that is associated with levels of resilience, greater positive affect and less depressive symptomatology (Ejiri et al., 2021; Carriedo et al., 2020). These components derived from self-esteem can become a predictor of subjective well-being (Zamarrón Cassinello, 2006). Research finds that active and healthy lifestyles increase life satisfaction (Kudo et al., 2007) and that life satisfaction is linked to a better perception of cognitive function (Rudolf et al., 2000; Okumiya et al., 1999 ),The confluence of these factors may favor a positive image of aging, which is associated with greater longevity and independence (Fernandez, 2003).

Social interaction and group activity provide life satisfaction to the elderly (García et al., 1996) (Villar et al., 2006) Social interaction can contribute to the development of psychological mechanisms that activate thoughts based on the contribution we give to the group and what is received from it (Rubio et al., 2016). Likewise, it is proposed that for adults to carry out an optimal aging process they must remain active in their social (Ferrada y Zavala, 2014); (La Guardia et al., 2000). According to (Wen Ku et al., 2016) physical activity has been widely established as a contribution to health and physical function.

Activity theory indicates that it is essential for older people to be active in social relationships to maintain good health (Engestrom, 2008) within the three dimensions of health is psychological well-being (Dixon y DIxon, 1984) participation in social activities correlate positively with psychological well-being (Fu et al., 2018) loneliness and social isolation are risk factors for psychological well-being (Shankar et al., 2015). Both in Latin America and elsewhere in the world, studies have been conducted to observe psychological well-being at this stage of life (Chang et al., 2020; Schwingel et al., 2009; Bukov et al., 2002) especially analyzing the role of social interaction in gerontological centers (Ferrand et al., 2014; Van Willingen, 2000). Psychological well-being is viewed as a result of social interaction or participation in activities such as music, thogeater (Tymoszuk et al., 2020) quality of life and psychological well-being increase as a result of physical activity and social integration (Clare et al., 2016). "Making' things accumulates more social contacts than looking at or listening to things. Making things refers to productivity and involves action and creativity and is often directed toward a certain end." Social capital and cognitive reserve are important factors in coping with declining cognitive abilities to maintain well-being in old age (Ihle et al., 2020).

Ryff (1989) operationalized a model of eudaimonic well-being composed of 6 dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relationships with other people, autonomy, mastery of the environment, purpose in life and personal growth. For their part, Vera Villarroel et al. (2012) observed, in a sample of 1,646 Latin American subjects between 18 and 90 years of age, that Ryff's original theoretical model is the one that best fit in all age groups. Also in older people, Tomás, Meléndez and Navarro (2009) showed that the 5- and 6-factor models showed very similar fit indices, so it would be problematic to choose one or the other (Didino et al., 2019). Over the years, the well-being construct has a broader approach, not only objective but also subjective, so there are reasons to analyze well-being in older adults. According to the study by Espinoza et al., (2018) suggests applying the Ryff scale to the older adult population in order to have a better understanding about the psychological well-being over the suggested population.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate psychological well-being in older adults participating in social interaction groups during the intervention period to determine longitudinally if there are significant differences at each time. In addition, to analyze whether the levels of psychological well-being are different between people over 65 years of age who attend the social interaction groups and those who do not attend. The study will allow us to establish an approximation to important indicators of psychological well-being in the study samples. The study questions have been posed as follows:

- H1: If older adults attend group dynamics programs, then they will improve their levels of psychological well-being over time.

H01: If older adults do not attend group dynamics programs, then they will not improve their levels of psychological well-being over time.

- H2: There are significant differences between the psychological well-being of the group of older adults who attend group dynamics programs with respect to the group that does not attend.

- H02: There are no significant differences between the psychological well-being of the group of older adults who attend group dynamics programs with respect to the group that does not attend.

Are there sociodemographic variables associated with social interaction components? We expect to identify significant differences associated with the variables gender, age, place of residence, and level of education.

Participants

The participants were older adult beneficiaries of public and private day care programs, belonging to Institutions with Community Liaison Agreements with a Higher Education Study Center in the central area of the Ecuadorian Littoral. The participants were older adult beneficiaries of public and private day care programs, belonging to Institutions with Community Liaison Agreements with a Higher Education Study Center in the central area of the Ecuadorian Littoral. He study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ap-proved by the Higher Collegiate Body of the State University of Milagro according to the guide-lines of the code of ethics (269-PROY). Once the project was approved, the gerontological care centers were approached to sign the informed consent forms of each of the participants who decided to participate in the study.

The data for this study were collected at three time points with a six-month interval: Time 1 (T1) N=204 (women n=97; men n= 107), Time 2 (T2) N= 161 (women n=74; men n= 87), Time 3 (T3) N= 143 (women n=72; men n= 71). The sample inclusion criteria were: 1. People over 65 years of age; 2. People who frequently attended the group dynamics program; 3.

Table 1.

Distribution of sample.

Table 1.

Distribution of sample.

| Groups |

Gropus |

Sex |

|

|

|

| Intervention group |

Grupo con intervenvion |

H |

% |

M |

% |

Total |

% |

| Groups I |

Grupo I |

107 |

52 |

97 |

47 |

204 |

100 |

| Groups II |

Grupo II |

87 |

54 |

74 |

46 |

161 |

100 |

| Groups III |

Grupo III |

72 |

50 |

71 |

50 |

143 |

100 |

| Groups without intervention |

Grupo sin intervencion |

89 |

56 |

71 |

44 |

160 |

100 |

| Total |

Total |

|

|

|

|

668 |

100 |

2. Materials and Methods

The application of psychometric tests is carried out during the intervention time of activities with older adults, which were established three times a week with the participants of the daytime modality (modality that consists of older adults attending the activities during the day and then returning to their homes) of each of the gerontological centers.

T1 (n=204): Before starting with the planned activities, a screening is performed by applying the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) in order to evaluate the cognitive area of the older adult and exclude the participation of those who present cognitive impairment. Afterwards, the first data collection is performed, applying the Psychological Well-Being scale to those who do not present cognitive impairment and who wish to participate voluntarily in the research.

T2(n=161): Before starting with the planned activities, the second data collection is performed, applying the Psychological Well-Being scale to the participants. In addition, a data collection of the application of the Psychological Well-being scale to (n=161) who do not attend the planned activities is performed.

T3: Before starting with the planned activities, the third data collection was carried out by applying the Psychological Well-being scale to the participants.

The participants who complied with the three indicators were a total of 89 people, 49.4% male, 50.6% female with a distribution between the urban sector 53% and rural 36%. The data were analyzed with the statistical package SPSS 27 and the Statis Analysis program for the results of the factor analysis in the course of the intervention time.

RYFF'S PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING (Scales of psychological wellbeing-reduced), the instrument contains 39 items and evaluates six dimensions (Ryff C. , 1989) I I. Self-acceptance (6 Items, e.g. "When I review my life history, I am happy with how things have turned out"), II. Positive relationships (6 Items, e.g. "I know I can trust my friends, and they know they can trust me"), III. Autonomy (8 Items, e.g., "I am not afraid to express my opinions, even when they are opposite to the opinions of most people"), IV. Mastery of the environment (6 Items, e.g." In general, I feel that I am responsible for the situation in which I live") V. Personal growth (7 Items, e.g., "For me, life has been a continuous process of study, change and growth"), VI. Purpose in life (6 Items, e.g., "I am clear about the direction and purpose of my life"). Participants responded using a Likert-type response format with scores from 1 (total disagreement) to 5 (total agreement), considering that the higher the score obtained, the higher the degree of psychological well-being and vice versa. (Dierendonck, 2005) (Freire et al., 2017)

In the analysis of different studies since Ryff's publication (

Table 2), the Spanish adaptation of the scale, the study of the psychometric properties of the scale in Chilean university students and in our study (

Table 3) we found the results of the internal consistency of the Psychological Well-being scale: Self-acceptance α= 0. 52; Positive Relationships α= 0.56; Environmental Mastery α= 0.49; Personal Growth α= 0.40; Autonomy α= 0.37; Purpose in life α= 0.33 33 (Ryff y Keyes, 1995); Self-acceptance α= 0.83; Positive Relationships α= 0.81; Environmental Mastery α= 0.71; Personal Growth α= 0.68; Autonomy α= 0.73; Purpose in life α= 0. 83 (Díaz et al., 2006); Self-acceptance α= 0.79; Positive Relationships α= 0.75; Mastery of the environment α= 0.62; Personal Growth α= 0.78; Autonomy α= 0.67; Purpose in life α= 0.54 (Véliz Burgos, 2012).

Statistic of Psychological Well-Being over time. Longitudinal Analysis

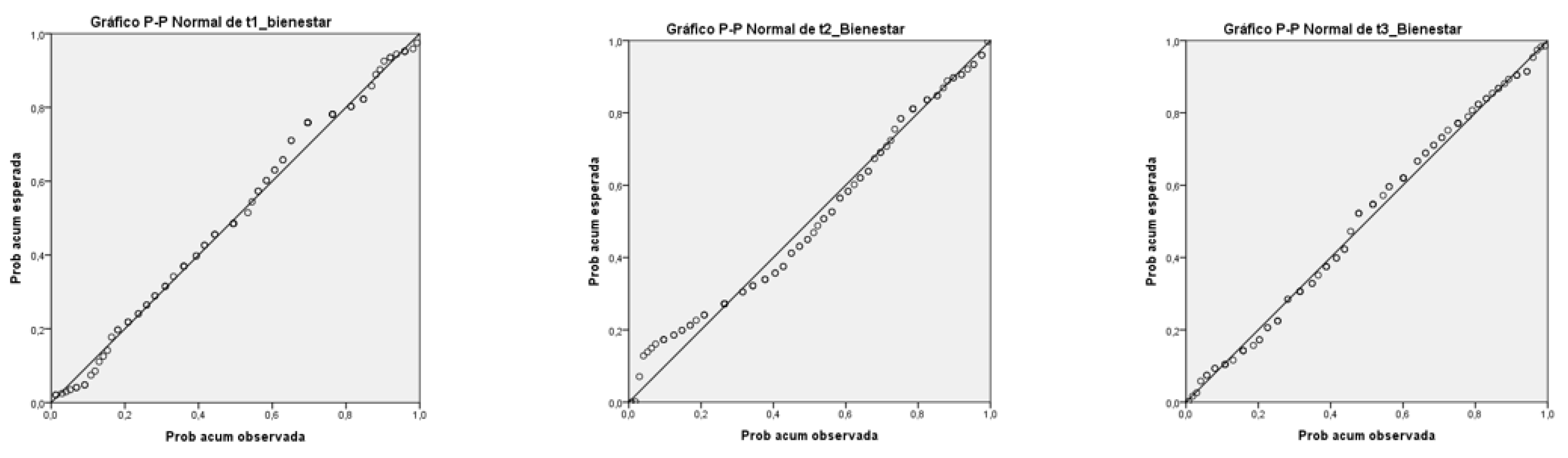

The data were run in the SPSS Program, for the repeated measures Anova analysis the data were run to confirm or reject the criteria of normality and homoscedasticity between the measures of the total score of the Psychological Well-Being Scale of the participants in the three times. According to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (

Table 4) and the P-P Plots analysis (

Figure 1) of the Psychological Well-Being total score measures at T1 and T2 do not meet the criteria of normality; therefore, a Friedman test is performed. The test presented a p < 0.005 showing that there is a significant difference in the scores in the three measurement times.

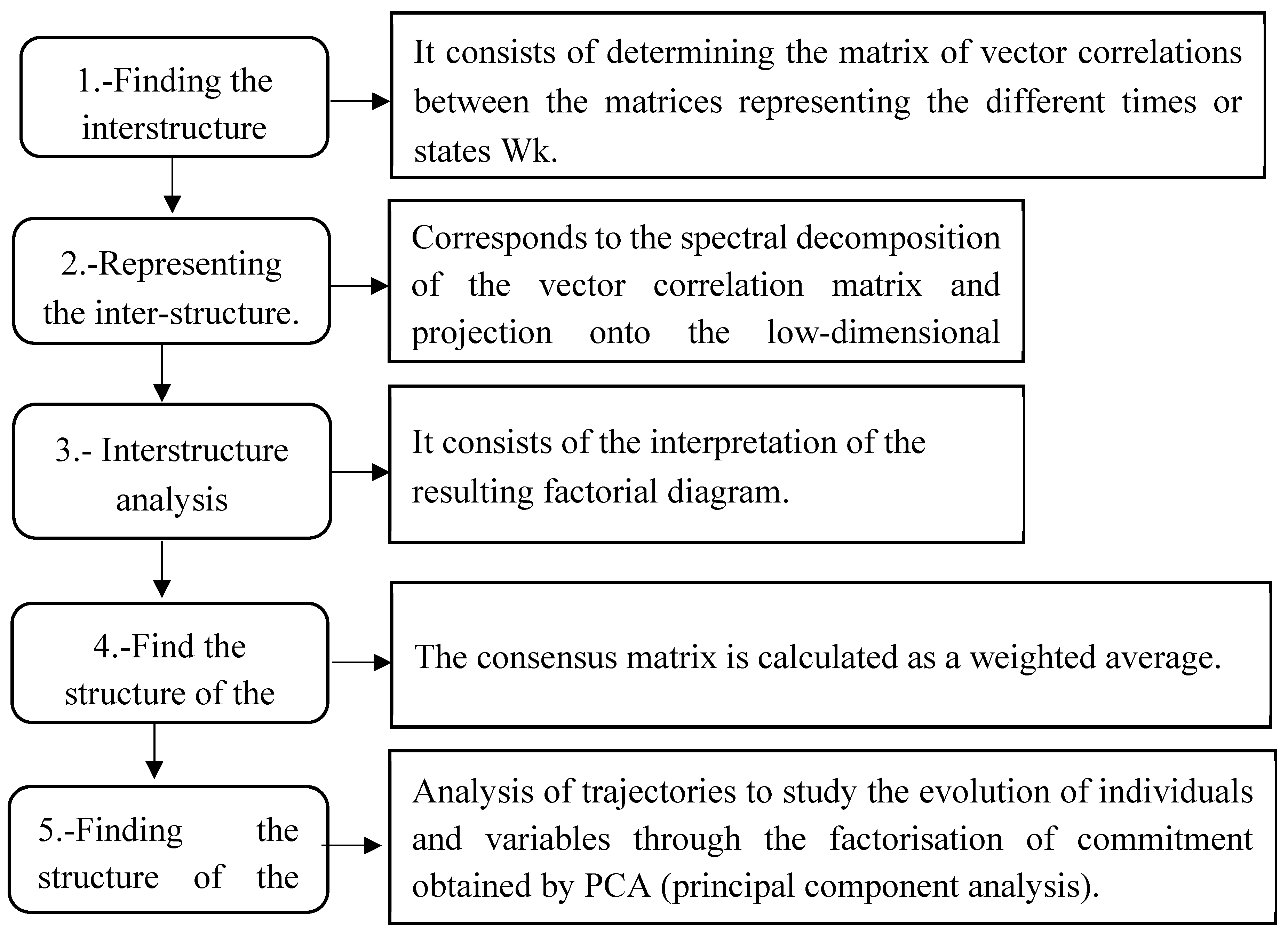

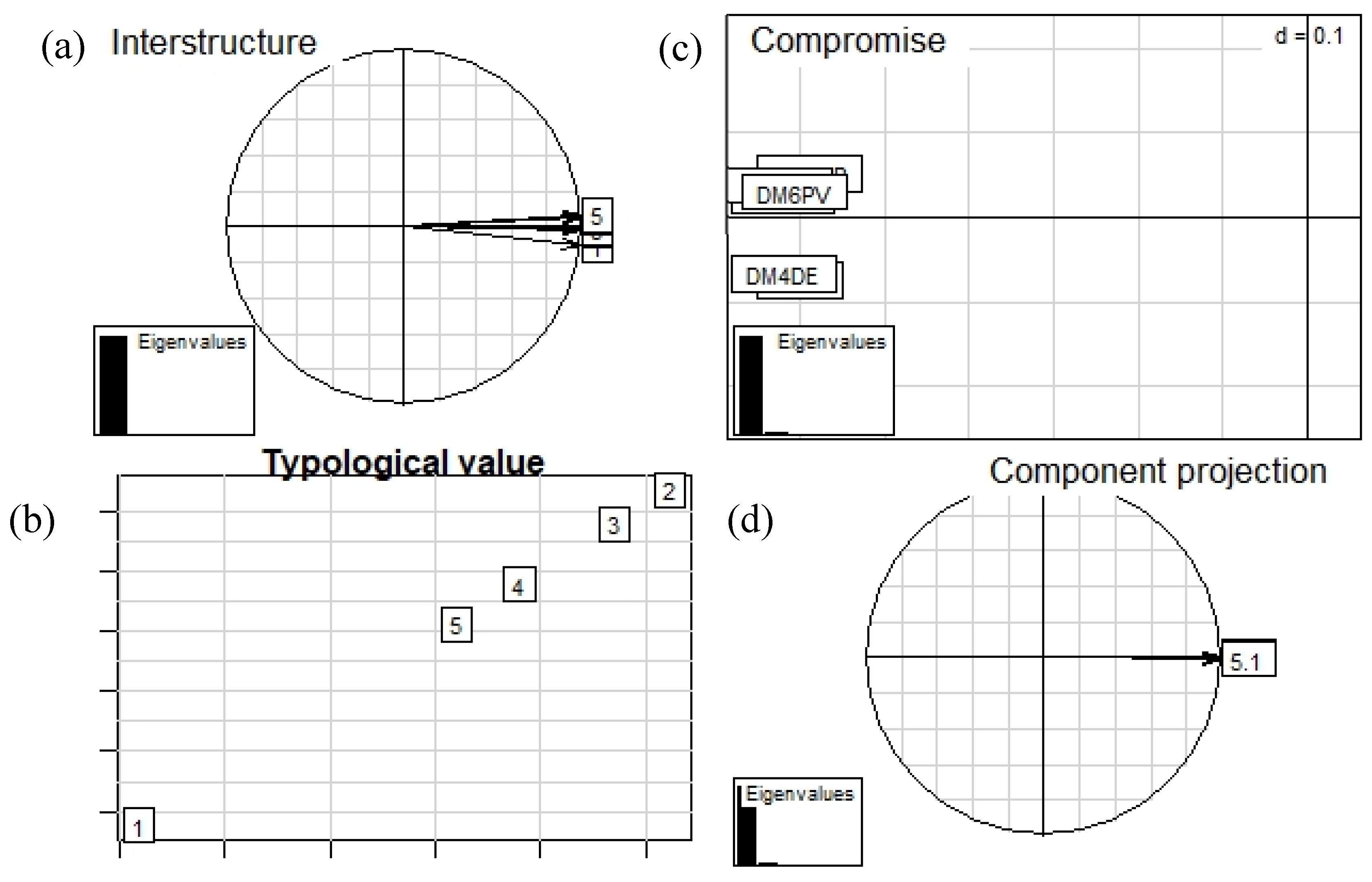

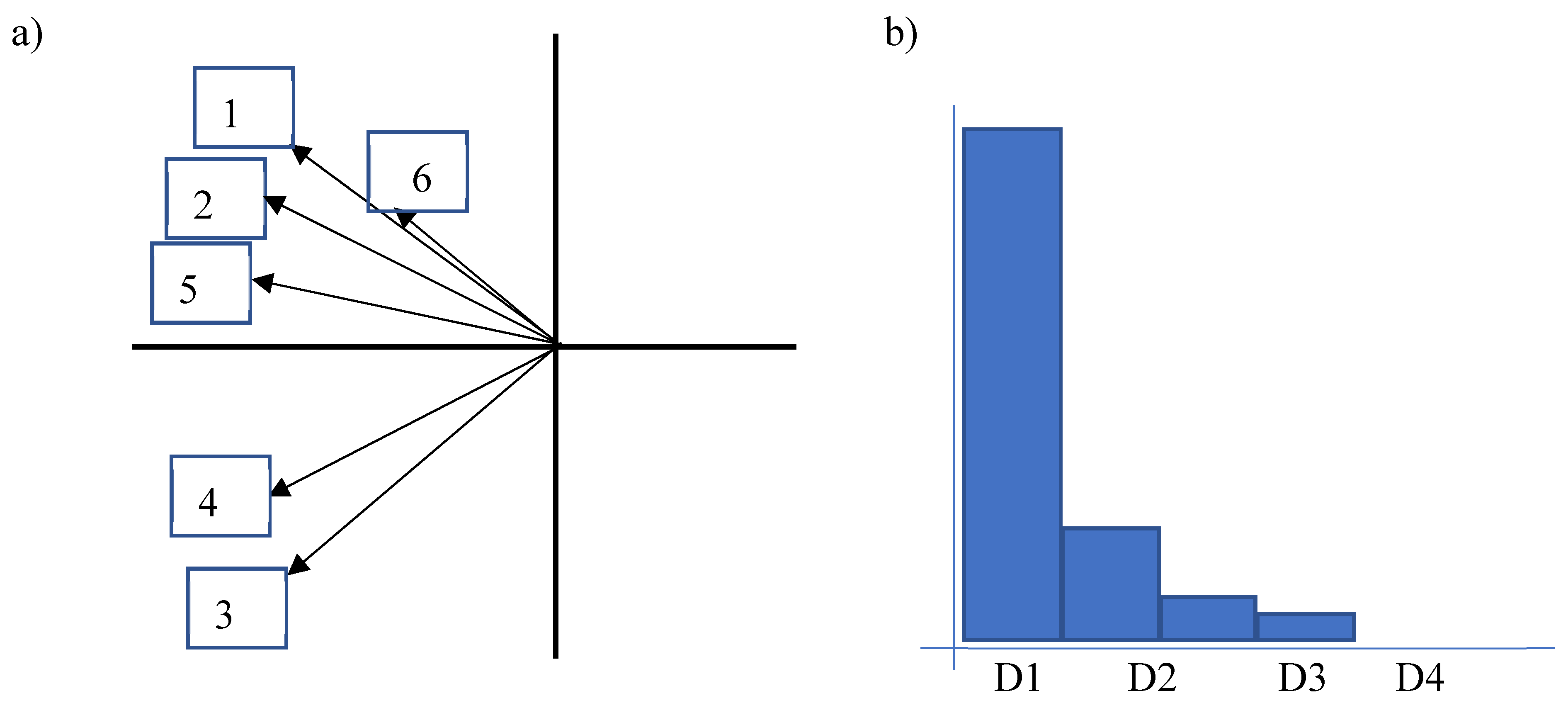

The statis method (Estructuration de Tableaux A Trois de la Statisque) is part of the multivariate analysis procedures for structuring three-way statistical tables, allowing to analyze the evolution of the data through the creation of a common reference system of N dimensions called axes of commitment, where different sets of individuals sharing the same variables in different times or states, emphasizing the positions of the individuals, represented in the rows of the different data sets or k matrices, where k corresponds to each time or state, therefore, they are constituted in the axes of commitment (Lavit et al., 1994; Lavit C. , 1988; Hermier des Plantes, 1976). Additionally, a Biplot (Gabriel, 1971) on the commitment structure was used, using the Ade4 package (Dray y Dufour, 2007) of the R software (R Core Team, 2015).

Configuration (operator/object)

W= XtXtT

W: Matrix of scalar products between individuals

Xt: Table at t state or time

XtT: Transposed t state or time table

Figure 2.

Stages in the development of the Statis Method.

Figure 2.

Stages in the development of the Statis Method.

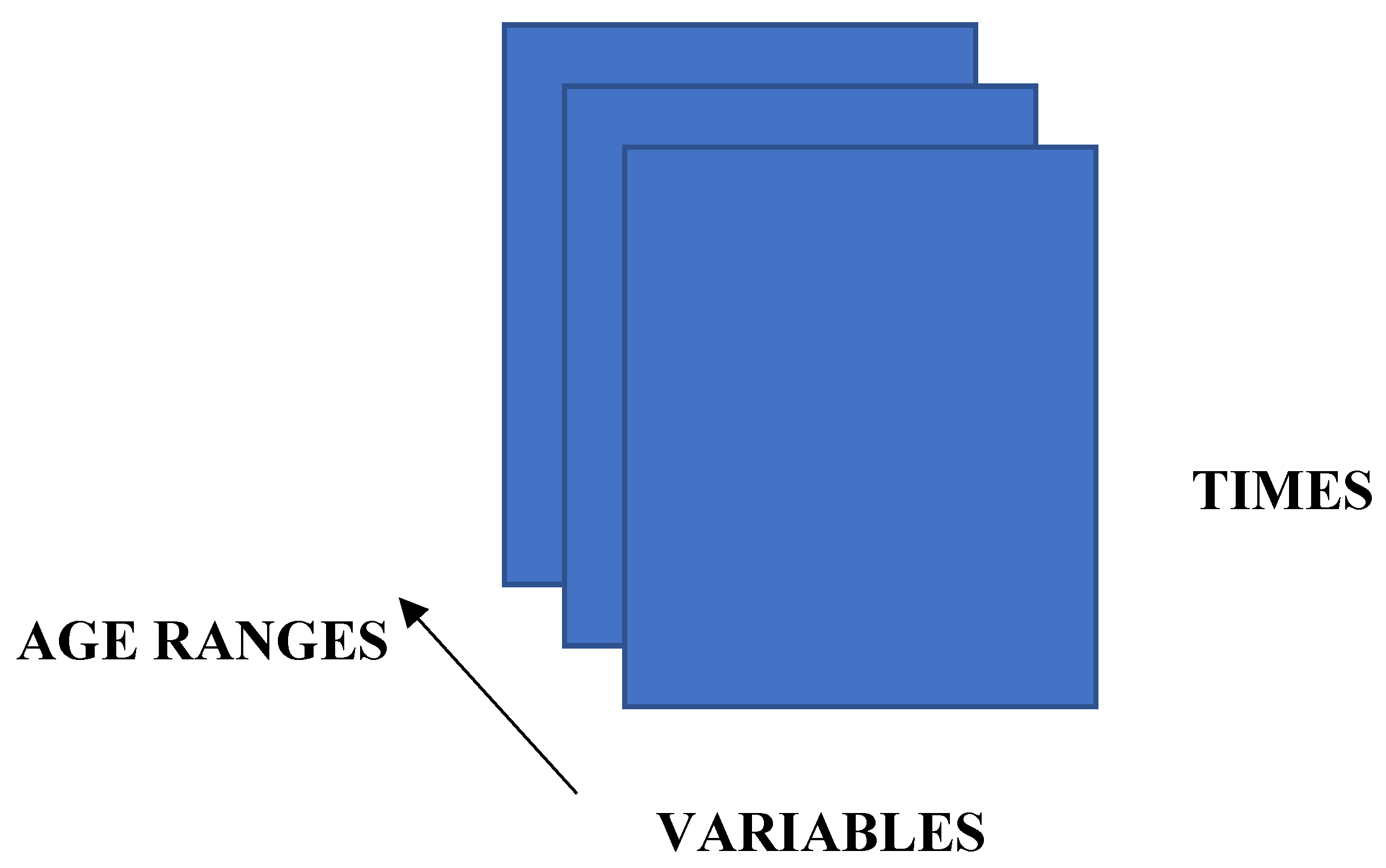

From the analysis of the data, 5 matrices were obtained, each one corresponding to the age ranges detailed in

Table 5.

The dimension of each matrix corresponds to the different times represented in rows and the 39 variables of the measurement instrument

Figure 3.

Table 6.

Vector correlation matrixes.

Table 6.

Vector correlation matrixes.

| Age range |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 1 |

1 |

0,9257673 |

0,9090922 |

0,8940826 |

0,9230575 |

| 2 |

0,9257673 |

1 |

0,9886795 |

0,9683517 |

0,9686277 |

| 3 |

0,9090922 |

0,9886795 |

1 |

0,9639016 |

0,967889 |

| 4 |

0,8940826 |

0,9683517 |

0,9639016 |

1 |

0,9572349 |

| 5 |

0,9230575 |

0,9686277 |

0,967889 |

0,9572349 |

1 |

Table 7.

Values specific to the commitment criteria.

Table 7.

Values specific to the commitment criteria.

| Age range |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

| 1 |

0,950222 |

0,309351 |

-0,0298 |

| 2 |

0,991824 |

-0,05189 |

0,047751 |

| 3 |

0,987444 |

-0,09224 |

0,088318 |

| 4 |

0,977991 |

-0,1299 |

-0,16305 |

| 5 |

0,984681 |

-0,02476 |

0,054028 |

In

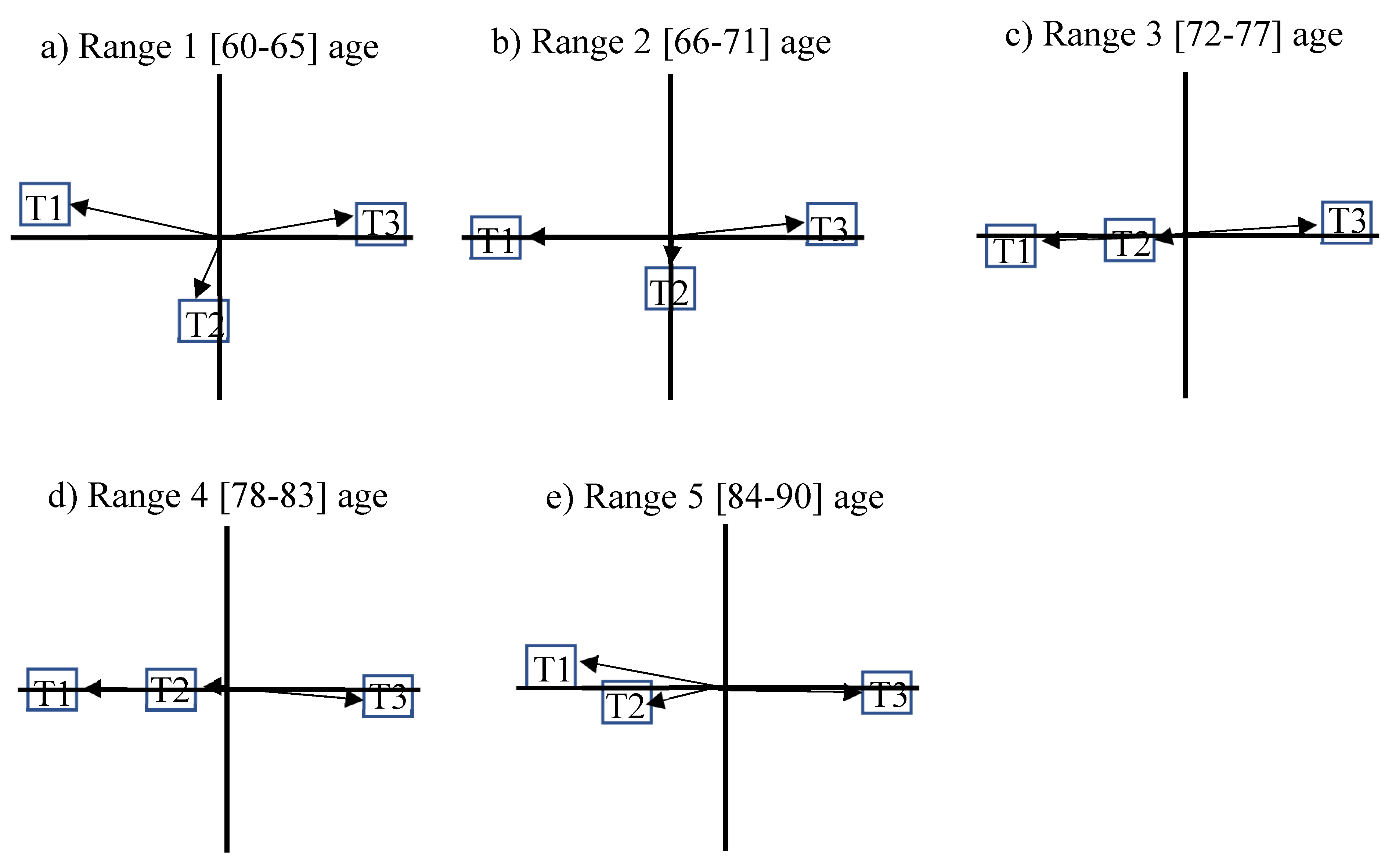

Figure 4 - (a) Range 1 [60-65] years, it is observed that the criteria in the 3 times are different, also in time 1 the criterion is contrary to time 3, specifically in the dimensions of self-acceptance, mastery of the environment and purpose in life where their perception expresses that they agree in time 1 and for time 3 their criterion is neutral. In grafic 2 - (b) Range 2 [66-71] years it is observed that the criteria are similar in the 3 times, except in the dimension of self-acceptance the criterion at time 0 is neutral and for time 2 they agree. In grafic 2 - (c) Range 3 [72-77] years, it is observed that the criteria are similar in the 3 times, specifically in times 1 and 2 in the dimensions of positive relationships, autonomy, mastery of the environment and personal growth. For the dimension of purpose in life, the criteria change from time 1, which was neutral, and for time 2 they are in agreement. In grafic 2 - (d) Range 4 [78-83] years, it is observed that the criteria at time 1 and time 3 are opposite, specifically in the dimensions of positive relationships, mastery of the environment and purpose in life, where their criteria at time 1 is neutral and for time 2 is in agreement.

Time 1 has a strong relationship with time 2 specifically in the dimensions of positive relationships and personal growth maintaining its neutral criterion. grafic 2 - (e) Range 5 [84-90] years, it is observed that the criteria in time 1 and time 2 have a strong relationship, specifically in the dimensions of self-acceptance, positive relationships and personal growth, where they maintain their neutral criterion. Time 1 has a different criterion than time 3, specifically in the dimensions of personal growth and purpose in life.

Infrastructure analysis

Vector correlation structure results

The projection in the Euclidean space

Figure 5 of the vector correlation structure of the tables is optimal and the first two principal components explain more than 95% of the total variability; in addition 2 groups are observed, the first one formed by the dimensions Self Acceptance DM1AA, Positive Relationships DM2RP, Personal Growth DM5CP and Purpose in Life DM6PV, the second group is formed by the dimensions of Autonomy DM3A and Mastery of the Environment DM4DE. The conformation of commitment is strongly represented by ranges 3 of ages 66-71 years and range 2 of ages 72-77 years

Figure 3 - (b).

Table 8.

Group activity and psychological well-being.

Table 8.

Group activity and psychological well-being.

| |

Prueba Chi-Cuadrado |

Valor |

df |

Significación asintótica (bilateral) |

| Actividad Grupal y Bienestar Psicológico |

Chi-cuadrado de Pearson

Razón de verosimilitud

Asociación lineal por lineal |

48,073a

55,325

46,337 |

3

3

1 |

0,000

0,000

0,000 |

| Actividad Grupal y Relaciones Positivas |

Chi-cuadrado de Pearson

Razón de verosimilitud

Asociación lineal por lineal |

7,737a

7,830

4,673 |

2

2

1 |

0,021

0,020

0,031 |

| Actividad Grupal y Crecimiento Personal |

Chi-cuadrado de Pearson

Razón de verosimilitud

Asociación lineal por lineal |

54,220a

57,826

53,782 |

2

2

1 |

0,000

0,000

0,000 |

Analysis of sociodemographic variables and their relationship with social interaction.

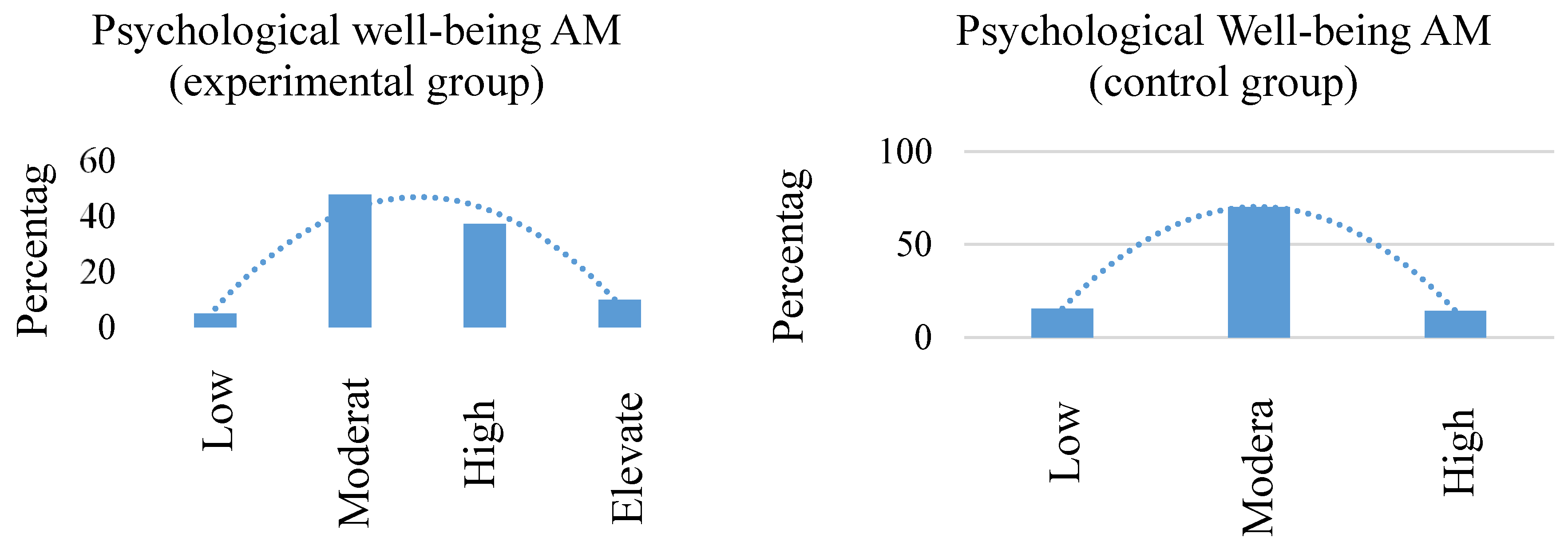

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis between Attendance and Non-Attendance groups at Intervention. Nota. Escala General – Bienestar Psicológico (t (320) = -1,93; p = 0,054).

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis between Attendance and Non-Attendance groups at Intervention. Nota. Escala General – Bienestar Psicológico (t (320) = -1,93; p = 0,054).

Discussion

According to what has been stated as an important purpose of Higher Education Institutions, as an instance of training professionals and commitment to the community to extend knowledge as part of the implementation of strategies of the Sustainable Development Goals such as Health and Well-being; Well-being that includes both physical and psychological health of all people, with greater emphasis on those who are within the group of vulnerability; For this reason, the results of a program of Community Intervention with Older Adults are shown. In this intervention, an analysis proposal was made with the main objective of evaluating the psychological well-being of older adults participating in the social interaction groups during the intervention period. According to the first analysis of the global result of Psychological Well-being in the course of the intervention time, a significant difference is observed between the three measurement times, observing a progressive longitudinal increase in the results of psychological well-being of the people who were participating in the entire intervention process thus confirming what studies indicate about the need for companionship and social bonding to mitigate the characteristics of advancing age and ensure full life. (Cornwell et al., 2008; Turcotte et al., 2018; Santini, et al.,2020).

In the analysis of the age factor and the dimensions of psychological well-being over time, differences are observed in the dimensions of self-acceptance, mastery of the environment and purpose in life, where a slight decrease is observed, which is similar to what Palomo-Vélez et al.,2020 indicates, that as the years go by, human beings tend to decrease in these areas. In the age range 66 to 71 years, similarities are observed in the results between the three periods, but an increase in the dimension of self-acceptance, an indicator that according to studies is strengthened in the process of social interaction and well-being (Tymoszuk et al., 2020).

As the participants increase in age range, it is observed that the purpose of life dimension increases, as indicated by different authors in their studies, that the greater the social bond, the greater the commitment and sense of feeling needed (Borglin, Edberg and Rahm 2005; Kleinspehn, Kotter and Smith 2008). Likewise, older participants who have been active since before the study and during the intervention process, presented better levels in the dimensions of personal growth and life purpose, these results are similar to studies (Carriedo et al., 2020; Ejiri et al., 2021) where older adults present greater positive affect and a decrease in depressive symptoms.

In the analysis of group activity and psychological well-being (

Table 9), the chi-square test statistics indicate an asymptotic level of significance (.000 < 0.05) with regard to group activity and psychological well-being, and therefore, in accordance with the hypothesis proposed, the null hypothesis (H01) is rejected and, consequently, the alternative hypothesis (H1) is accepted. The latter indicates that if older adults attend group dynamics programs, then their levels of psychological well-being will improve over time. Specifically, positive relationships (.021), which refers to establishing quality relationships with others, and personal growth (.000), which emphasizes personal development, improved.

It is important to show the comparative analysis of psychological well-being with respect to group 1 that attends the intervention process and group 2 that does not attend the intervention process, with a confidence level (p = 0.05); as long as the p-value is equal to or less than 0.05 (p = 0.054), there is a statistically significant difference. Thus, the alternative hypothesis (H2) is accepted, which establishes that there are significant differences between the psychological well-being of the group of older adults who attend group dynamics programs with respect to the group that does not attend. Specifically, it is observed that group 1 presents high percentages of psychological well-being compared to group 2.

Another important data that was analyzed in the process of variables contributing to Psychological Well-being is that which represents the statistics of the chi-square test with respect to the sociodemographic variables and social interaction, obtaining an asymptotic significance level (0.328 > 0.05; 0.276 > 0.05; 0.145 > 0.05) with respect to place of residence and level of study with social interaction, so the null hypothesis (H08) is accepted, which states that there is no significant relationship between sociodemographic variables and social interaction in older adults.

Conclusions

According to the results of the study it is concluded that the participation in group dynamics of people in the aging process improves the dimensions of Psychological Well-being, likewise that the comparative between the groups of analysis indicates that there are differences between the results of group 1 and group 2. That in this study the sociodemographic variables are not determinant in the process of improvement or decrease of psychological well-being, that age does present variations in the results but that these are attenuated or improved when social activity is frequent and sustained.

That gerontological centers should maintain agreements with institutions of higher education to continue strengthening in a reciprocal manner the benefits of social interaction in intergenerational encounters where participants of different ages are part of the social and generational heritage. This promotes active aging and the inclusion of the elderly in daily life activities.

The limitations of the study are not having inquired about the quality of sleep, in addition to not having sampled different groups of socioeconomic levels or participants with higher levels of education. Another limitation is that we did not have the perception of the young people who participated in the study intervention for the description of the changes they observed in the older adults during the intervention time, which would have enriched the data obtained from each application of the Psychological Well-Being instrument.

According to the results, it can be indicated that future research could investigate retrospective variables that could contribute to protective elements of Psychological Well-being such as family functionality, decision making, emotional intelligence and personality that would contribute even more to strengthen intervention plans in the promotion of active aging to better generate Health and Well-being. In addition, retrospective variables could provide us with early indicators of depression that could accelerate cognitive decline and decrease quality of life and psychological well-being.

Author Contributions

R.L.E and C.L.G : Methodology: R.L.E and B.A ; Software: R.L.E and C.L.G : Writing, review, editing R.L.E , C.L.G and B.A. Supervision C.L.G and B.A.g Formal analysis: : R.L.E. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Higher Collegiate Body of the State University of Milagro according to the guidelines of the code of ethics (269-PROY). Date of approval: 16 August 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The submitted study data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the students of Psychology who participated in the project of intervention in older adults, to the authorities of the gerontological centres who opened their doors for the realization of the study. To the Department of Liaison and the Department of Statistical Study Centre of the State University of Milagro.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, R., Aragón, O. R., Bookwala, J., Cherbuin, N., Gatt, J. M., Kahrilas, I.,... Richter, H. (2021). The neuroscience of positive emotions and affect: Implications for cultivating happiness and wellbeing. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 121, 220-249. [CrossRef]

- Berk, R. (2001). The active ingredients in humor: Psychophysiological benefits and risks for older adults. Educational Gerontology, 27, 323-339. [CrossRef]

- Borglin, G., Edberg, A. K., & Hallberg, R. (2005). The Experience of Quality of Life among Older People. Journal of Aging Studies, 19, 201-220. [CrossRef]

- Bukov, A., Maas, I., & Lampert, T. (2002). Social participation in very old age: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from BASE. Berlin Aging Study. Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci., 57(6), 510 - 517. Obtenido de PMID: 12426433. [CrossRef]

- Carriedo, A., Cecchini, J.-e., Fernandez-Rio, J., & Méndez-Giménez, A. (2020). COVID-19, Bienestar Psicológico y Niveles de Actividad Física en Adultos Mayores Durante el Confinamiento Naciona en España. Am J of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(11), 1146-1155. [CrossRef]

- Chang, P., Wei Tsou, C., & Shan Lic, Y. (2020). La influencia de los factores de vías verdad urbanas en el bienestar psicológico de los adultos mayores: un estudio de caso de Taichun, Taiwán. Silvicultura urbana y ecologización urbana, 49, 126606. [CrossRef]

- Charles, S., & Cartensen, L. (2010). Envejecimiento social y emocional. Revista Anual de Psicología, 383-409. [CrossRef]

- Clare, G., Geldenhuys, G., & Gott, M. (2016). Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health and Social Care in the Community. [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, B., Laumann, E., & Schumm, L. (2008). La conexión social de los adultos mayores: un perfil nacional. American Sociological Review, 73(2), 185-203. [CrossRef]

- Dávila Hernándeza, A., & González González, R. (2016). Sinomedical study of the pathophysiology of depression. Revista Internacional de Acupuntura, 10(1), 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Townsend, K. (2019). Patrones de participación social y sus asociaciones con la salud y el bienestar de adultos mayores. SSM-Salud de la Población, 8, 100424. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C., & Dierendonck, D. (2006). Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema, 18(3), 572-577.

- Didino, D., Pinheiro-Chaga, P., Wood, G., & Knops, A. (2019). Response: Commentary: The Developmental Trajectory of the Operational Momentum Effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dierendonck, D. (2005). The construct validity of Ryff`s Scales of Psychological Well-Being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 629-643.

- Dixon, J., & DIxon, J. (1984). Un modelo evolutivo de salud y viabilidad. Avances en Enfermería Ciencia, 1-18.

- Dray, S., & Dufour, A. B. (2007). The ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software, 22(4). [CrossRef]

- Ejiri, m., Kawai, H., Kera, T., Ihara, K., Fujiwara, Y., Watanabe, Y.,... Obuchi, S. (2021). El ejercicio como entrategia de afrontamiento y su impacto en el bienestar psicológoco de los adultos mayores que viven en la comunidad japonesa durante la pandemia de COVID-19 un estudio longitudinal. Psicología del Deporte y el Ejercicio, 57, 102054. [CrossRef]

- Engestrom, Y. (2008). Teoría de la actividad enriquecedora sin atajos. Interact with Computers, 20(2), 256-259. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J. A., Meyer, J. P., Anderson, B. K., Vaters, C., & Politis, C. (2018). Evidence for a Bifactor Structure of the Scales of Psychological Well-Being Using Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Well-Being Assessment, 2(1), 21–40. [CrossRef]

- Ferrada, L., & Zavala, M. (2014). Bienestar Psicológico: Adultos Mayores Activos a través del voluntariado. CIENCIA Y ENFERMERIA, 123-130.

- Ferrand, C., Martinent, G., & Durmaz, N. (2014). Psychological need satisfaction and well-being in adults aged 80 years and older living in residential homes: Using a self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Aging Studies, 104-111. [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A., & Nicolle, J. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness: the new geriatric giants: Approach for primary care. Canadian Family Physician, 176-182.

- Freire, C., Ferradás, M., Núñez, C., & Valle, A. (2017). Estructura factorial de las Escalas de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff en estudiantes universitarios. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 10, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Fu, F., Liang, Y., An, Y., & Zhao, F. (2018). Autoeficacia y bienestar psicológico de los residentes de hogares de ancianos en China: el papel mediador del compromiso social. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 28(2), 128 -140. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, K. R. (1971). The biplot graphic display of matrices with application to principal component analysis. Biometrika, 58, 453–467. [CrossRef]

- García, M. C., Torio, J., Sánchez, M. A., & San Juan, M. (1996). Evaluation of a communty experience of social interaction and promotion of exercise and leisure time: Subjetive impact and participent’ ssatisfaction. Aten Primaria, 19(9), 18-26.

- Hermier des Plantes, H. (1976). Structuration des tableaux à trois indices de la statistique. Université des Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc.

- Ihle, A., Oris, M., Sauter, J., Spini, D., Rimmele, U., Maurer, J., & Kliegel, M. (2020). The relation of low cognitive abilities to low well-being in old age is attenuated in individual with greater cognitive reserve and greater social capital accumuted over the life course. Aging & Mental Health, 24(3), 387-394. [CrossRef]

- Inclusión, M. d.-C. (2019). Informe Mensual de Gestión MIESS. Obtenido de https://info.inclusion.gob.ec › 2020-inf-pam-usrint.

- Jia, R.-x., Liang, J. h., & Xu, Y. Q. (2019). Effects of physical activity and exercise on the cognitive function of patients with Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr, 19(181). [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.-x., Liang, J.-h., Xu, Y., & Wang, Y.-q. (2019). Effects of physical activity and exercise on the cognitive function of patients with Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics.. [CrossRef]

- Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A., & Kotter Grühn, D. (2008). Self-perceptions of aging: do subjective age and satisfaction with aging change during old age? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 63(6), 377–385. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, H., Izumo, Y., Kodama, H., Watanabe, M., Hatakeyama, R., Fukuoka, Y.,... Sasaki, H. (2007). Life satisfaction in older people. Geriatr Gerontol, 7, 15–20. [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J., Ryan, R., Couchman, C., & Deci, E. (2000). Within-Person Variation in Security of Attachment: A Self-Determination Theory Peerspective on Attachment, Need Fulfillment, and Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(3), 367-384. [CrossRef]

- Lavit, C. (1988). Analyse conjointe de tableux quantitatifs. Paris: Masson.

- Lavit, C., Escoufier, Y., & Sabatier,, R. (1994). The ACT (STATIS method). Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 18, 97-119. doi:1016/0167-9473(94)90134-1.

- Law, M. M., Broadbent, E. A., & Sollers, J. J. (2018). A comparison of the cardiovascular effects of simulated and spontaneous laughter. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 37, 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, J. C., Navarro, E., Oliver, A., & Tomás, J. M. (2009). La satisfacción vital en los mayores. Factores sociodemografico. Boletín de Psicología(95), 29-42. Obtenido de https://www.uv.es/seoane/boletin/previos/N95-2.pdf.

- Okumiya, K., Matsubayashi, K., Wada, T., Fujisawa, M., & Osaki, Y. (1999 ). A U-shaped association between home systolic blood pressure and four-year mortality in community-dwelling older men. J Am Geriatr Soc, 7(12), 1415–1421. [CrossRef]

- Palomo-Vélez, G., García, F., Arauna, D., Muñoz-Mendoza, C., Fuentes, E., & Palomo, I. (2020). Efectos del estado de fragilidad en la felicidad y la satisfacción con la vida: el papel mediador de la salud autopercibida. Revista Latinoaméricana de Psicología, 52, 95-103. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2015). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Viena. Obtenido de https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rubio, L., Dumitrache, C. G., Cordón-Pozo, E., & Rubio Herrera, R. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI) in older people. anales de psicología, 32(2), 355-365. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L., Dumitrache, C., & Rubio-Herrera, R. (2016). Realización de actividades y extraversión como variables predictoras. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 51(2), 75-81. [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, W. H., Ponds, M. P., Van Boxtel, J., & Jellem Jolles. (2000). Age Related Changes in subjetive cognitive functioning. Educational Gerontology, 26(1), 67-81. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Pesonality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C., & Keyes, C. (1995). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727. [CrossRef]

- Sancho, P., Sentandreu-Mañó, T., Fernández, I., & Tomás, J. (2022). El impacto de la soledad y la fragilidad en el bienestar de los mayores europeos. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 86-93. [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., York Cornwell, E., Koyanagi, A., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C.,... Koushede, V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Salud Pública, El. [CrossRef]

- Schwingel, A., Niti, M., Tang, C., & Ng, T. (2009). Continued work employment and volunteerism and mental well-being of older adults: Singapore longitudinal ageing studies. Age Ageing, 531-7. [CrossRef]

- Sentandreu-Mañó, T., Badenes-Ribera, L., Fernández, I., Oliver, A., Burks, D., & Tomás, J. (2022). La fragilidad en la vejez como marcador directo de calidad de vida y salud: diferencia de género. Investigación de Inidacadores sociales, 160, 429-443. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A., Bjorn Rafnsson, S., & Steptoe, A. (2015). Longitudinal associations between social connections and subjective wellbeing in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychology y Health, 30(6), 686-698. [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, N., & Grühn, D. (2018). The Differential Impact of Social Participation and Social Support on Psychological Well-Being: Evidence From the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. European Journal of Psychology of Education. [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, P.-L., Transportista, A., Roy, V., & Levasseur, M. (2018). Terapeutas ocupacionales, contribuciones para fomentar la participación social de los adultos mayores: una revisión de alcance. Revista Británica de Terapia Ocupacional, 81(8), 427-449. [CrossRef]

- Tymoszuk, U., Perkins, R., Spiro, N., William, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Longitudinal Associations Between Short-Term, Repeated, and Sustained Arts Engagement and Well-Being Outcomes in Older Adults. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciencies, 75(7), 1609 - 1619. [CrossRef]

- United Nation. (2017). World Population Prospects. 2-46. New York.

- Van Willingen, M. (2000). Differential Benefits of Volunteering Across the Life Course. Journal of Gerontology: SOCIAL SCIENCES, s308-s318. [CrossRef]

- Véliz Burgos, A. (2012). PROPIEDADES PSICOMÉTRICAS DE LA ESCALA DE BIENESTAR PSICOLÓGICO Y SU ESTRUCTURA FACTORIAL EN UNIVERSITARIOS CHILENOS. PSICOPERSPECTIVAS, 11(2), 143-163. [CrossRef]

- Vera Villarroel, P., Urzúa M, A., Silva, J. R., Pavez, P., & Celis Atenas, K. (2012). Ryff Scale of Well-Being: Factorial Structure of Theoretical Modelsin Different Age Groups. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 26(1), 106-112. Obtenido de https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/188/18826165012.pdf.

- Villar, F., Triadó, C., Solé, C., & Osuna, J. (2006). Patrones de actividad cotidiana en personas mayores: ¿es lo que dicen hacer lo que desearían hacer? Psicothema, 18(1), 149-155. Obtenido de https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72718123.pdf.

- Wen Ku, P., Fox, K. R., Liao, Y., Sun, W. J., & Chen, L.-J. (2016). Prospective associations of objectively assessed physical activity. Springer International Publishing Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organizational. (2022). World Health Organizational. Obtenido de World Health Organizational : https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20Decade%20of,communities%20in%20which%20they%20live.

- Zamarrón Cassinello, M. D. (2006). El bienestar subjetivo en la vejez. Revista: Informes Portal Mayores(52).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).