1. Introduction

Currently, the world population need the increasing amount of dietary meat that promote the dynamic development of a new branch of poultry farming, namely quail farming, as the source of eggs and quail meat. The meat of the bird is of delicate consistency, juiciness, and aroma [

1]. The poultry shows high egg productivity and rapid precocity. Females start laying eggs at the age of 35 – 40 days giving up to 250 – 280 eggs per year. Moreover, the feed consumption per 1 kg of egg quantity is of 2.8 – 3.1 kg, and the weight of the eggs laid by one female for a year 24-fold excesses the body weight of the female, whereas in the best chicken breeds this ratio is 1:8 [

2]. The egg trend in the quail farming has been most popular in Japan and in the countries of The Far East where the quail eggs are mainly used for medical and dietary nutrition [

3]. But in the countries of Europe, the meat direction of the quail farming is the most developed. Both quail meat and eggs are produced in the USA [

4]. The products of this industry in some countries are used not only for food but also as raw materials in the perfume industry to prepare high-quality creams, shampoos, and some other cosmetic products [

5].

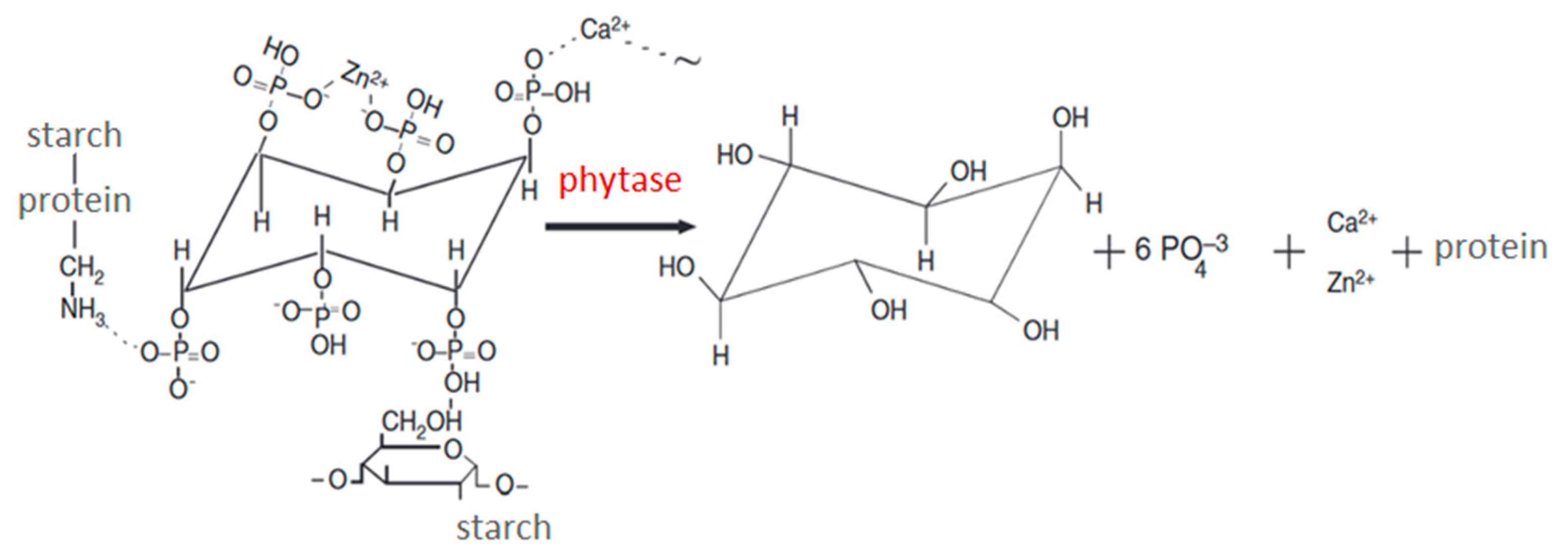

Successful cost-effective breeding of quails is possible only if the production supposes to provide the conditions for the biological features of the poultry, the latest development in the field of feeding and poultry keeping technology [6-9]. Obtaining high productivity of the poultry including the quails needs applying the balanced feed with phosphorus as an important component. In the cells of all living organisms, there are both forms of phosphorus, namely ortho- and pyrophosphates and moreover the phosphorus is present in the composition of phosphoproteins, phospholipids, nucleic acids, hexosophosphates, etc. In the vertebrates, phosphorus, along with calcium, is part of bone tissue. The main form of organic phosphorus in the plant feed for the poultry is myo-inositol hexakisphosphoric or phytic acid being a derivative of myo-inositol, a cyclic alcohol phosphorylated by all 6 hydroxyl groups (

Figure 1) [10, 11]. The negatively charged phosphoric acid residues in the phytic acid molecule form the salts (phytates) with cations of iron, zinc, calcium, magnesium, and some other elements, and also react with proteins, starch, and lipids to form insoluble conglomerates (

Figure 1). In the plants, most of the phosphorus is represented by insoluble phytates present most of phosphorus, Ca

2+, and Mg

2+. Grains of cereals, sunflower seeds, cotton, pumpkin, and legumes are the richest sources of phytates containing more than 60% of total phosphorus [

12]. Phytates are also found in tubers and some other plant organs.

Both phytate phosphorus and mio-inositol get available for assimilation only if being eliminated under phytase action. The grains of cereals and legumes, seeds of oilseeds forming the basis of feed give 60-88% of the total phosphorus. Because of the absence of phytases in the digestive system of monogastric animals they can’t assimilate the most of the phosphorus in the plant feeds. In its turn, the phosphorus lack causes the evident disorders in the formation of the animal skeleton. Upon the limited amount of available phosphorus in the feed the content of phytic phosphorus increases, which is assimilated by the adult poultry by 50%, and is by young ones only by 30 % [

13]. Recently, more and more attention has been paid to the use of various phytase preparations in the poultry industry [

14]. Thus, there are some data that up to 90% of the mixed feed for the poultry are enriched with phytases, the enzyme preparations eliminating indigestible phytate-containing complexes [15-17] The use of those is provided not only by the effect on the phytate complex of the plant feed but also by a decrease in the inorganic phosphates, as well as by a decrease in the phosphorus excretion with the faeces into the environment [18, 19]. The use of the feed additives containing phytases in the poultry and animal husbandry permits to effectively reduce the specific feed consumption spent per a unit of production, which means the reduction of the wastes generated, thereby increasing the profitability of agricultural production.

Phytase catalyzes the phytate hydrolysis (myo-inositol 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate) (

Figure 1), which is the main form of the phosphorus depot in the plants and is not assimilated by monogastric animals because of the lack of the sufficient phytase production in the gastrointestinal tract [

20]. The current market offers a wide range of phytase preparations mainly based on phytases of microbial origin of class A (PhyA) and class C (PhyС) [21, 22]. However, while passing through the chyme of the poultry the enzyme significantly reduces due to acid denaturation and proteolysis. The technology of phytase encapsulation in the yeast-producing cells as microcontainers can essentially decrease the loss of the enzyme and facilitate its thermal stability. Extremophilic yeast

Yarrowia lipolytica is a promising object of modern biotechnology, in particular, for the production of encapsulated phytase owing also to the full sequence of its genome and the availability of special tools to creating highly effective strains-producers of recombinant proteins [23-25].

In our previous studies [

26] we assayed the phytase activity of the

Y. lipolytica Po1f pUV3-Op transformant producing intracellular (encapsulated) phytase from

Obsumbacterium proteus (OPP) based on the pUVLT2 vector with the mitochondrial porin promoter

VDAC (

Voltage

Dependent

Anion

Channel). When cultured under alkaline conditions (pH 8.0), close to the pH in the intestine of the poultry the VDAC promoter as the pUV3-Op genetic construct part in the

Y. lipolytica Po1f pUV3-Op transformant was induced, it was accompanied by an increase in phytase activity. The results obtained during the cultivation of the transformant

pUV3-Op-2 in the fermenter confirmed a high activity of extracellular phytase upon assimilating of phytate-containing substrates. The high stability of the intracellular phytase of the transformant

Y. lipolytica pUV3-Oр for heat treatment when using a spray dryer was also noted [

27]. In addition, we have received encouraging results from testing a phytase supplement based on transformed yeast in broiler chickens [

28].

This study is aimed at performing the experiments on the quails using the new encapsulated phytase additives based on the recombinant producer of Y. lipolytica Po1f pUV3-Op in the poultry diets and evaluating the effect of the additives on the productivity of young and adult quails.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Bird Husbandry

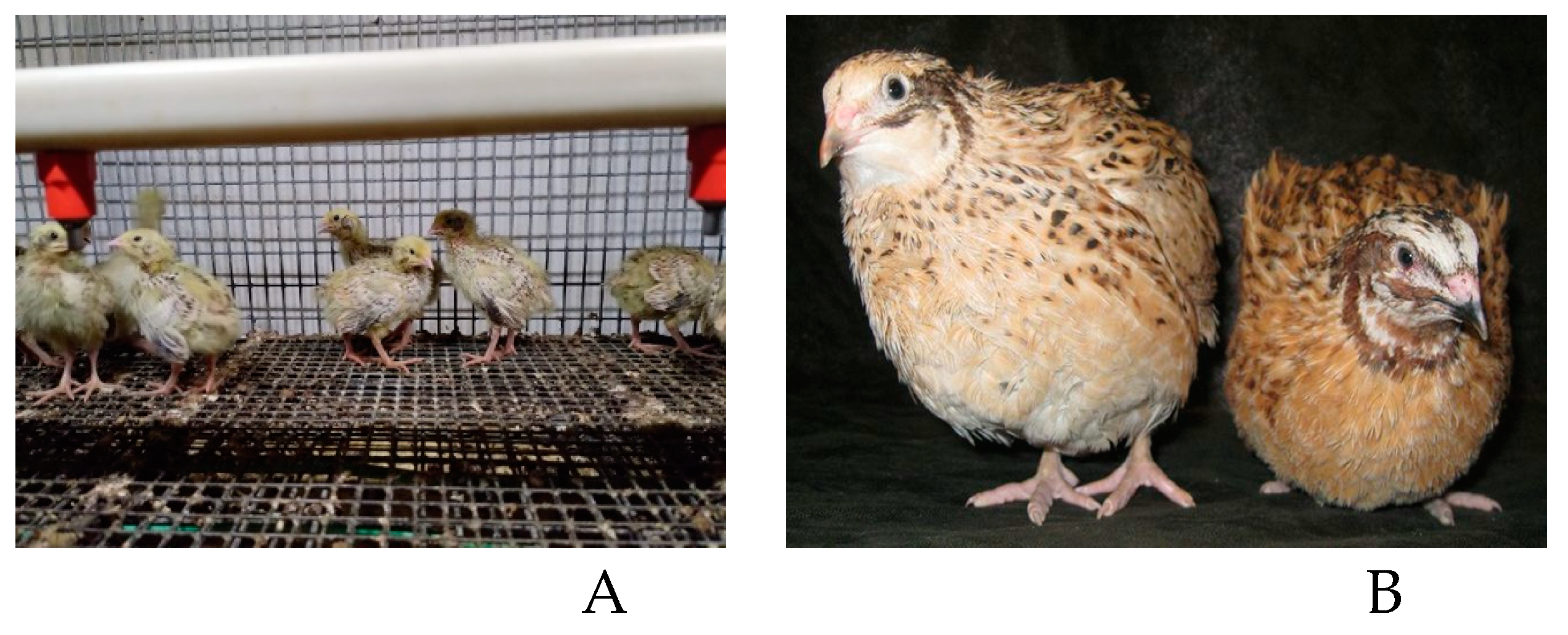

The research was performed in the Russian Research and Technological Poultry Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences using the Manchurian golden quail (

Coturnix japonica) (

Figure 2) breed listed in the International Register of Quail Breeds and Lines. It is a very productive breed with good egg production of rather large size. In the experiments the males and females were raised in the common cell batteries for young animals up to 42 days. 42-day old quails were separated into males and females and transferred to the cage batteries for adult birds where they were kept until 60-day age with a sex ratio of 1:4 (male: female). The humidity was maintained at 65±5% during the whole experiment while the indoor temperature varied: it was 30°C for the first week, in the second one it was 28°C, in the third one it decreased up to 26 – 25°C, in the fourth and further ones it was 23 – 22°C.

The experimental protocol was approved at the assembly of the Local Ethics Committee of The Federal Research Center “Fundamental Bases of Biotechnology” of Russian Academy of Sciences (Protocol No. 22/1 dated from 09.07.2022). In total, 150 one-day-old Manchurian golden quail were cooped into battery cages (25 heads in each colony cage for 42 days, and then they were reared in mixed-sex groups in pens, 20/1394 cm2). 42-day old quails were separated into males and females and transferred to the cage batteries for adult birds where they were kept until 60-day age with a sex ratio of 1:4 (male: female). The experiment was performed in the Russian Research and Technological Poultry Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences and kept at a temperature of 30°C for the first week, then it gradually decreased up to 22-23°C by the fourth week. The experiment was performed at humidity of 65±5% using a 12 h photoperiod. The quails had ad libitum access to water. A bird bath per nine heads was provided. The sex of the birds was not distinguished at the moment.

Feeds were prepared from vegetable raw materials (corn, wheat, soybean meal, full-fat soybeans, sunflower meal, vitamin premix with the addition of synthetic feed amino acids of lysine, methionine, and threonine, but without raw materials of animal origin). For the first 28 days, the quails were fed using a starter diet (

Table S1). The basic feed was used in a crushed form; in the experimental groups, the additives were supplied as powder. Then, each quail was weighed, and the experimental groups of 25 heads each were assembled using the method of analogous pairs. Furthermore, the experiment was performed for 60 days. Every group had ad libitum access to feed. The diet was supplied in excess twice a day to control consumption, and each feed provision was weighed. Be-fore supplying a fresh feed provision, the remaining residue was weighed again, and the amount was subtracted from the initial weight of the feed to determine the feed consump-tion and calculate the FCR.

2.2. Dietary Plan

In the experiments the pilot batches of feed additive containing microencapsulated

O. proteus phytase and commercial Ladozym proxy phytase from

Aspergillus ficuum, with an activity of 5000 FYT/g, were used to study the efficiency of feeds with a total phosphorus of ~0.6% (available phosphorus 0.31-0.33%). The feed included: 1) the first diet of food for quail from the first day of life up to 4- week age; 2) the second diet of feed for the quails of 5 to 6 weeks of age; 3) the third diet for adult quails of the initial egg-laying period of 42 to 60 days of life. The feed was prepared using vegetable raw materials (corn, wheat, soy meal, full-fat soy, sunflower cake, vitamin premix with some synthetic feed amino acids of lysine, methionine, and threonine) No animal raw materials were used. The total phosphorus in the three types of feed was 0.6 g per kg of feed while the available phosphorus reached 0.35–0.45% g per kg of feed that was 20-25% lower than those recommended for the quails. The feed for the three periods is in

Tables S1-S3.

In the experiment, six groups of one-day old quails were formed with 25 heads in each differing in the types of feed:

Control group 1 got the feed with total phosphorus of 0.8% (0.45% of available phosphorus) without any additives;

Control group 2 got the feed with a total phosphorus of 0.6% (0.35% of available phosphorus) without any additives;

Experimental group 3 got the feed containing total phosphorus of 0.6% (0.35% of available phosphorus) supplied with the microencapsulated O. proteus phytase at a dose of 500 FYT per a kg of feed;

Experimental group 4 got the feed containing total phosphorus content of 0.8% (0.45% of available phosphorus) supplied with the microencapsulated O. proteus phytase at a dose of 500 FYT per kg of feed;

Experimental group 5 got the feed containing a total phosphorus content of 0.8% (0.45% of available phosphorus) supplied with the commercial phytase Ladozim proxy from A. ficuum at a dose of 4500 FYT per a kg of feed;

Experimental group 6 got the feed containing a total phosphorus content of 0.6% (0.35% of available phosphorus) supplied with the commercial phytase Ladozim proxy from A. ficuum at a dose of 4500 FYT per a kg of feed.

2.3. Preparing Feed Additives by Cultivation of the Yeast Strain

The preparation of bioadditives was carried out as described in [

28] with some modifications. The

Y. lipolytica strain was raised on a complete solid medium of the following composition (g/L): yeast extract—10, Bacto Peptone—20, glucose—20, and Bacto agar—20 at 28°C for 48 h. Then, the biomass was washed out with sterile water and used as an inoculum. The yeast was raised in batches of 100 mL in the medium (g/L): Mg

2SO

4—0.5, (NH

4)

2SO

4—0.3, KH

2PO

4—2.0, K

2HPO

4—0.5, NaCl—0.1, and CaCl

2—0.05), with different substrates. The substrate from the waste was prepared as it was described in [

28].

The inoculation medium had the following composition (g/L): yeast extract—10, Bacto Peptone—20, fat of the chicken intestine—5, and sophexyl antifoam—0.35 mL/L, at pH 6.1; it was prepared and sterilized in a 3-litre fermenter for an hour (Miniforce Infors AG CH-4103 Bottmingen («INFORS HT», Switzerland) equipped with controlled рН и рО2, at 28°C for 21 h at a rotation of 350 rpm and aeration of 3 L/min

The culture medium pH and the partial pressure of oxygen were monitored using a sterilizable Clark-type oxygen sensor with a quick response. The final cultivation was performed in a 10-litre fermenter with a working volume of 7.5 litres (LabMakelaa, Baar, Switzerland). The medium contained yeast extract (Difco, Leeuwarden, The Nether-lands)—10 g/L; Bacto Peptone (Difco, Leeuwarden, Netherlands)—20 g/L; and chicken fat—5 g/L. The defatted chicken intestine paste was sterilized for 40 min at 120°C. The ini-tial pH of the cultivation medium was 5.5. The fermentation was performed at 28°C for 72 h at a rotation of 350 rpm with a sterile air input of 3 L/min. The antifoam solution was prepared using 150 mL sophexyl in 500 mL distilled water and sterilized for 40 min at 120°C. The cultivation medium pH was monitored, and the concentration of dissolved oxygen was measured using the Clark-type electrode with a glass-reinforced TEFLON membrane (Sea&Sun Technology, Trappenkamp, Germany).

The cell pellets and insoluble residue of the medium were concentrated using flow separation. The biomass was dried using spray drying at 75°C, with 1 L of the concen-trated suspension per hour (Buchi Mini Spray Dryer B-290, Switzerland). The resulting powder was weighed and assayed for phytase activity.

2.4. Assay of Phytase Activity

The phytase activity in the feed additives was assayed with a colorimetric method to assess the phosphate ion, which is released from phytate as described before [

27]. A ten-milligram aliquot of the ground additive was placed into an Eppendorf tube. The sample was mixed with 50 mg of 0.3 mm glass beads and 500 mL of 250 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.5; then the mixture was kept in an ice-cold bath for 10 min. The swollen cells were homogenised using triple stirring with a vortex for 2 min each. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min. The suspensions obtained were diluted in a 250 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and 5 µL aliquots of dilutions 1, 2, and 4 were put into the wells of a flat-bottom immunological plate (Nunc Low-Sorb, Roskilde, Denmark). The medium contained 100 µL of substrate mix (5.1 mM sodium phytate in the same buffer). The plate was closed to prevent exsiccation and exposed at 37°C for an hour. Then, 50 µL of Fiske & Subbarow reagent was applied to each well, and the plate was incubated at a room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance at 415 nm was assayed using a Uniplan plate spectrophotometer (Pikon, Moscow, Russia). The phytase unit was calculated as the amount of the enzyme, which releases 1 _mol of phosphate ions per minute in those conditions.

2.5. Sample Collection and Processing

To determine the quality of the meat and internal organs of the bird, the slaughter of some 42-day old quails was performed. Three hen-quails and three cock-quails were selected from each group. There was performed an anatomical dressing of the poultry where the average weight of the carcasses, the slaughter yield, the yield of the main parts of the carcasses including the main internal organs were assayed.

2.6. Assay of Egg Production

The intensity level of egg laying is the main feature of the egg productivity of the poultry. This indicator was assayed using the ratio of the number of eggs laid for a certain period to the number of laying hens for the same period.

2.7. Assay of the Experimental Diets and the Chicken Faeces Composition

All the samples used for element assay were dried at 60°C until they reached constant weight. Then, 10 g samples were ground in a porcelain mortar, and 0.5 g of sample was picked up for assay. The chemical compositions of the feeds for the experimental groups and the chicken faeces were assayed at Dokuchaev Soil Science Institute of the RAS using the method of energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence EDXRF (Thermo scientific,Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) analysis with the Respect instrument (Tolokonnikov Plant LLC, Moscow, Russia) as it was described in [

29].

2.8. Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR)

The FCR was calculated as described in [

30].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The standard error of the mean (SEM) was calculated as described in [

31]. All the data collected were analyzed using STATISTICA 10 (2011) (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA,

www.statsoft.com, accessed on 15 September 2022. All the data were presented as group mean values± standard deviation (mean± SD), continuous data were compared using ANOVA, and frequency data were compared using a chi-square test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Animals get phosphorus from plant feeds mainly as hardly soluble phytates. In monogastric animals, including poultry, the only source of phytases for releasing phosphate groups from phytates are plant phytases coming from feed and their own intestinal microflora. Phytases are enzymes of the phosphatase class that catalyze the cleavage of phytic acid to inorganic phosphate [

32]. They are reported to strengthen bones and facilitate the the efficiency of animal nutrition [33-35]. Phytase dietary supplements improve intestinal health by reducing the secretion of the gastrointestinal tract, which leads to the increased productivity and energy used [

36]. However, because of various reasons (low activity of phytases in feedstocks, a decrease in their activity during heat treatment and feed storage, the difference in the pH optimum of the enzyme and the acidity of the gastrointestinal tract), the assimilation of phytates in the tract exceeds no more than 10%, and the remaining need for phosphorus should be substituted by mineral additives [

37]. Most of the phytates from animal feed are not digested and excreted into the external environment with faeces. Phytic acid binds cations so its high level in the diet, for example in the grain-based feeds could cause a deficiency of some elements, namely calcium, iron, zinc, etc. and reduce their assimilation. [

38]. The main trend in solving the problem is to decrease the introduction of mineral additives and to apply the phytases for providing the animals in phosphorus from phytates [39-41].

Currently, phytases from Escherichia coli of the PhyC class, formerly manufactured under the brand name of Quantum and Quantum Blue by Vista AG are the main type of feed phytases used in the poultry farming. They have replaced the PhyA class phytases from deuteromycete fungi (Natuphos (BASF), Ronozyme HiPhos (DSM NP), Phyzyme XP (Danisco Animal Nutrition), which before dominated in the market of the poultry enzymes. The instability of microbial enzymes at an acidic pH (~1) in the poultry stomach is an evident disadvantage of phytase technologies. Moreover, the optimum pH of the phytase of classes PhyA (~2.2 and ~5.2) and PhyC (~5.5) does not coincide with the pH of the poultry gastrointestinal tract where phytate hydrolysis undergoes: duodenal department (6.4-6.6), the small intestine department (6.5-7.0) and the colon (6.5-7,5) [

42]. It proves that the residual phosphorus in the excreta, even upon using the phytases is from 40 to 60% of their original level in the feed. The application of either phytases with a pH optimum within 6.0-7.5 or the encapsulation of phytases in the microcontainers which are stable in the stomach of the poultry, but can dissolve in the duodenum should significantly increase the efficiency of phytases.

Before in our studies, using the phytase from

O. proteus (the Enterobacteriaceae family), a technology for microencapsulation of phytase inside the cells of the

Y. lipolytica extremophilic yeast was proposed. The encapsulation had success if the secretory systems were blocked upon designing the producer. There was some drop in the target enzyme yield per a unit of the medium, on average, from 15,000-40,000 FYT/l in a secretory producer based on the same yeast species to 1,000-1,500 FYT/l. However, it significantly improved the technological features of the producer since it needn’t concentration and drying of the enzyme preparation that reduces the energy costs by 10-50 times and makes the technology completely waste-free [

26]. An essential increase in the phytase stability in the stomach of the animal was the maim result. In the experiments using mice we observed significantly higher weight gain at a dose of encapsulated enzyme 100 FYT per a kg of feed than upon using the commercial water-soluble phytase from

A. ficuum at a dose of 3,000 FYT per a kg of feed [

43].

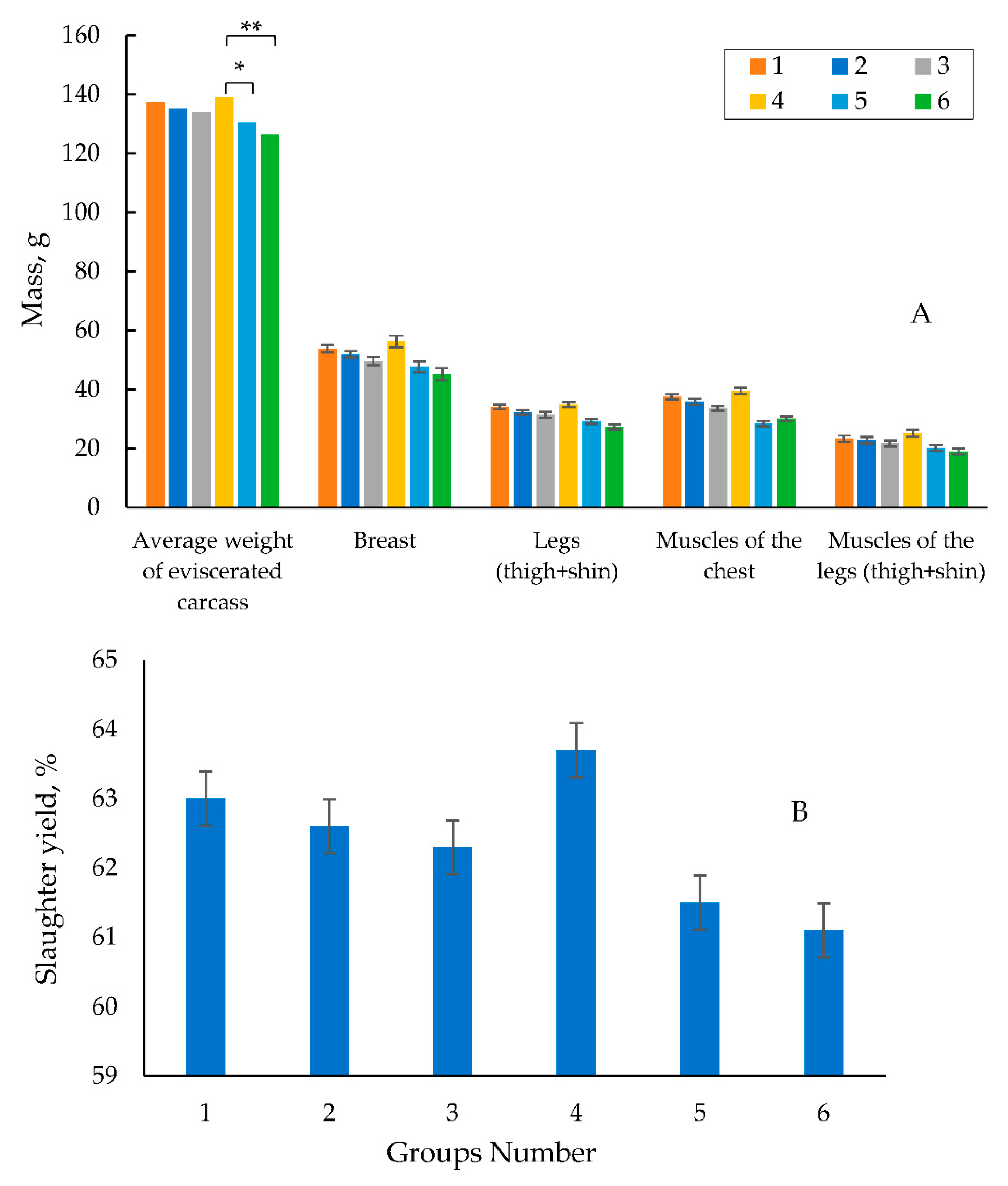

Upon performing the present study on assay of the effect of microencapsulated phytase applied as a feed supplement on the weight gain of the quails, it proved that the highest average live weight of 218.1 g, of the 42-day old quails was obtained in experimental group 4, using a diet with the microencapsulated

O. proteus phytases based on

Y. lipolytica yeast at a dose of 500 FYT per a kg of feed and the total phosphorus of 0.8% (0.45% of available phosphorus). The average live weight of the quails in experimental group 4 was 0.2 and 1.2% higher than that in control groups 1 and 2 (without phytase) respectively, and was higher by 3.3 and 5.5% compared to that in experimental groups 5 and 6, using the diet with the commercial water-soluble phytase from

A. ficuum, respectively (

Table 1). The highest average daily gain in live weight of the young quails up to 42 days of life was noted in experimental group 4 where it amounted to 5.0 g (

Table 1). Moreover, FCR in groups 3 and 4 decreased compared to that in control groups 1 and 2 by 1% and 2.01%, respectively (

Table 2). However, FCR increased by more than 2% for groups 5 and 6 using the feed with the commercial phytase. It should also be noted that in group 4 using microencapsulated

O. proteus phytase, the highest slaughter yield, pectoral muscle, thigh, and leg weight were observed in the poultry both at the age of 42 days (

Figure 4) and 60 days (

Figure 6). The data indicate that the encapsulated phytase showed higher efficiency on the productivity of the quails than extracellular phytase from

A. ficuum, belonging to the class of water-soluble phytases of the PhyA and PhyC. In the paper by [

44] the authors studied the efficacy of the phytase-containing supplement of Agrofit in the feeds for the meat quails. They found that feeding phytase in the amount of 75 g/t of the feed (~330 FYT per a kg of feed) increased the average daily gain in live weight of the quails by 4.8%, increased the percent alive by 1.5% and improved the feed conversion by 12.2%. The enzyme preparation of Agrofit ("Agroferment", Russia) contains the enzyme phytase with an activity of at least 5000 units/g (the producer of

Penicillium canescens PhPl-33 BKM F-3867D) and according to its features it can belong to class A phytases. A comparative analysis of the productivity of the experimental groups used by the authors and the results obtained in our experiments showed that under the similar feeding conditions (0.4-0.45% of available phosphorus, 500 FYT a kg of feed), we got the similar productivity of 1.2% versus 1.3% stated in the paper and the comparable feed costs (3.73-3.71 kg per 1 kg of live weight gain). However, it should be noted that unlike the composition of the feed used by the authors (fish flour, 7.98%, and meat and bone flour, 5.26%), the feed in our experiments contained no animal products and the phytase preparation we applied caused 100% percent alive of the quail population unlike those in the paper (97.5%). Thus, we have practically confirmed that the encapsulated phytase from

O. proteus applied to the quail feed, is highly effective even compared to the commercial preparations.

It should be noted that there are some studies in the world references [35, 45] where various aspects of the phytase effect on the morphological and biochemical features of the quails, the properties of their eggs and meat were assayed. However, there are no comparative data on the effect of water-soluble phytases on the productivity of the quails, which makes it difficult to compare the data obtained in our experiments to the results of other authors. In the study by [

46] it was shown that the introduction of 500-2500 FYT per a kg feed (Ronozyme P, Roche Corporate Headquarters, Basel, Switzerland), along with xylanase, released the transportation stress in Japanese quails (

Coturnix Coturnix japonica). In the paper by [

47] the positive role of phytase (Natuphos E 10000, BASF, Brazil) in the concentration of 300 FTU/kg of feed in daily weight gain of the quails fed without animal components, phosphorus deficient by 65%, was proved. The authors concluded that phytase itself suppresses the negative effects of moderate phosphorus restriction in the cultivation of Japanese quails, but doesn’t cope with it upon strict phosphorus restriction. In another study, Japanese quails were fed with the diets containing 500 and 1000 FTU ru-1 phytases, and the best results were obtained in FCR [

48]. Moreover, in the paper by [

45], using the quails, there were no positive effects of the phytase (Natuphos 500) at a dose of 1000 phytase units (FTU) per a kg of the feed on the poultry productivity. Ravindran et al. [

49] supposed that such difference between the effects obtained using the diets with a high phytase concentration may be due to some factors, including the source of phytase, ingredients, dietary features in each study using the poultry.

The assay of the composition of the experimental feed diets and the excreta of the quails for phosphorus amount showed that on the 28th day of the experiment the level of residual phosphorus in groups 3 and 4 (feed with the microencapsulated

O. proteus phytase at a dose of 500 FYT a kg of feed) decreased compared to that in control group 1 by 10% and 7%, respectively. While in group 5 using the commercial phytase Ladozim proxy from

A. ficuum (PhyA) at an abundant dose of 4500 FYT a kg of feed, the phosphorus level even increased by 9.5% (

Table 7). By the forty second day of the experiment the phosphorus level in the excreta of group 4 decreased by 0.8%, while in group 5 that increased by 7.7%. The similar data were obtained by us before in the experiments on broiler chickens [

28]. The application of the encapsulated phytase almost halved the residual phosphorus in the excreta compared to those in both control groups, which could be a key argument in favor of the high efficiency of the encapsulated phytase in the intestinal tract of broilers unlike the free enzyme. Along with the phosphorus release the encapsulated enzyme at a high dose (500 FYT a kg of feed) significantly reduced the residual content of valuable macro- and microelements, namely Mg, K, Ca, Zn, and Cu [

28]. Taken together, these data indicate a high degree of assimilation of phytate-containing products in the presence of encapsulated phytase by the quails and broiler chickens compared as to the control as to the commercial phytase preparation of the PhyA class.

At the second stage of the experiment, we first assayed the quail egg production and demonstrated that the highest one was obtained in experimental group 4, where it reached 86.8% (

Table 5) exceeding those in 1,2,5, and 6 by 9.7, 13.2%, 11.8, and 9.0%, respectively (

Table 5). The positive effects of the phytase on egg production and egg properties are well known for laying hens. So, Lim et al. [

50] showed that the application of the microbial phytase at a dose of 300 FTU a kg of feed can improve the egg production, reduce the percent of broken and soft eggs, and phosphorus excretion. Furthermore, the effects of phytase supplement depended much on the level of Ca and non-phytate phosphorus. The interaction between the level of the phytase and non-phytate phosphorus showed that phytase increased the egg production in the chickens with a diet containing 0.25% phosphorus, but not in the chickens using a diet with 0.15% non-phytate phosphorus and 4.0% Ca. Casartelli et al [

51] assayed the effect of phytase (0 and 100 FTU/kg) in diets including various sources of phosphorus and calcium (Ca and sodium phosphate, microgranulated di-Ca phosphate and triple superphosphate). They showed that the application of the phytase significantly affected the egg production traits.

Reports of the effects of the phytase on the egg production are very few. There is some information of an important influence of the ratio of Ca and P concentrations in the feed on the egg production of Japanese egg quails [

52]. We tried to perform the experiment according to the factorial scheme. The experiment was an entirely randomized design, where 2.68% Ca and 0.38% P were considered as the optimal concentrations. It can be assumed that the high degree of digestibility of Ca and P, which are provided upon applying the encapsulated phytase

O. proteus (

Table 7), could favorably affect not only the weight gain of the poultry and the feed conversion, but also the egg production.

Figure 1.

Scheme of phytate cleavage in the phytase reaction.

Figure 1.

Scheme of phytate cleavage in the phytase reaction.

Figure 2.

The quails of the Manchurian golden breed. A – chicks; B – the adult birds.

Figure 2.

The quails of the Manchurian golden breed. A – chicks; B – the adult birds.

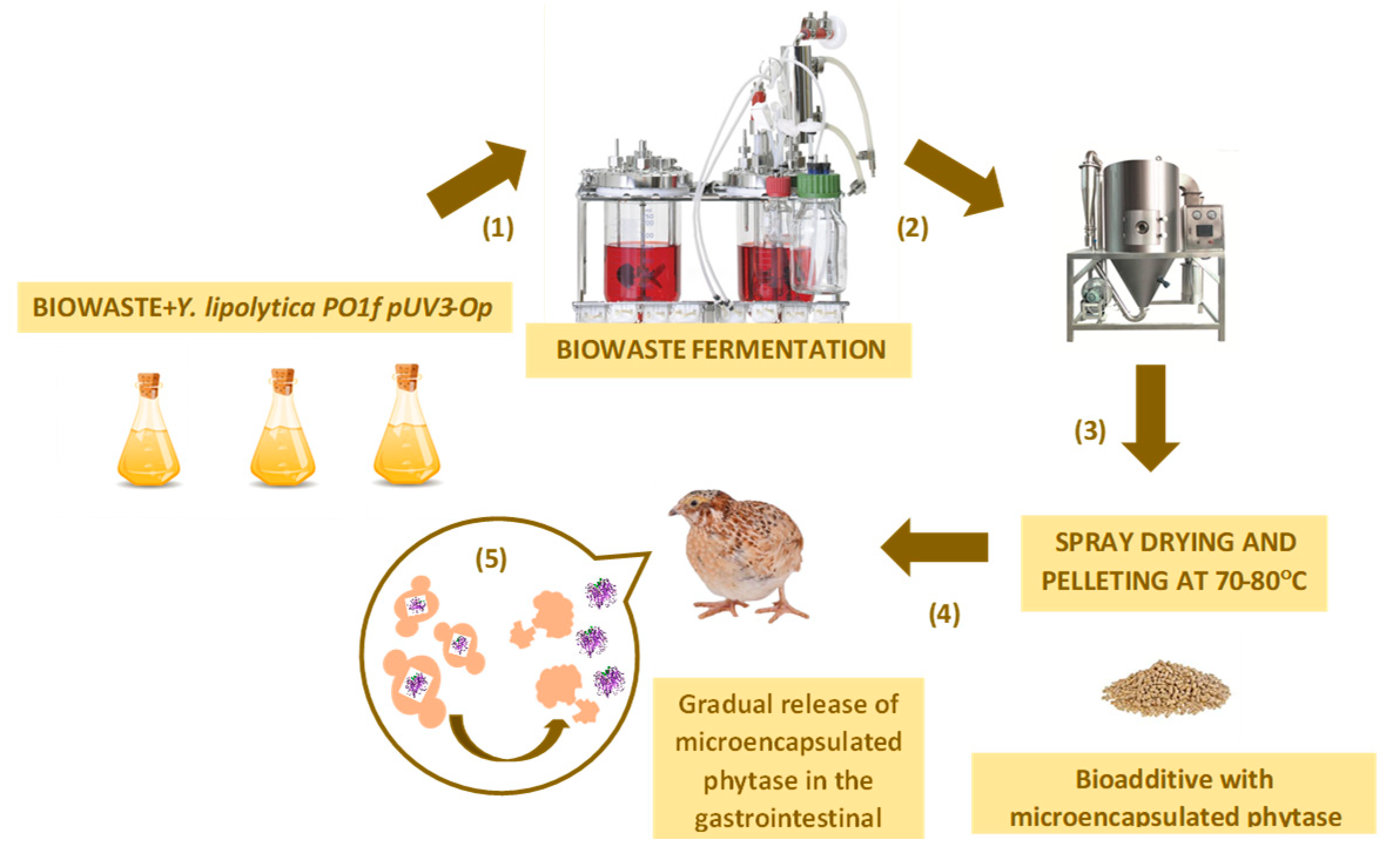

Figure 3.

Scheme of the experiment for testing bioadditives on experimental animals (1) Production of the yeast biomass using the fermentation of the waste as the substrate (temperature - 28°C; at a rotation of 350 rpm; pH 5.5, at pH of 5.5 and 8 0). (2) Drying the product using a spray dryer (Mini Spray Dryer B-290, BÜCHI) at 70°C. (3) Grinding and granulation of the biomass; (4) the preparation of feed mixtures based on the recombinant Y. lipolytica PO1f (pUV3-Op) tranformant. (5) The analysis of the efficacy of the encapsulated phytase in the Y. lipolytica PO1f (pUV3-Op) transformant for increasing the phosphorus bioavailability and reducing anti-nutritional phytate activity of plant feed using the model of quails compared to the commercial phytase efficacy.

Figure 3.

Scheme of the experiment for testing bioadditives on experimental animals (1) Production of the yeast biomass using the fermentation of the waste as the substrate (temperature - 28°C; at a rotation of 350 rpm; pH 5.5, at pH of 5.5 and 8 0). (2) Drying the product using a spray dryer (Mini Spray Dryer B-290, BÜCHI) at 70°C. (3) Grinding and granulation of the biomass; (4) the preparation of feed mixtures based on the recombinant Y. lipolytica PO1f (pUV3-Op) tranformant. (5) The analysis of the efficacy of the encapsulated phytase in the Y. lipolytica PO1f (pUV3-Op) transformant for increasing the phosphorus bioavailability and reducing anti-nutritional phytate activity of plant feed using the model of quails compared to the commercial phytase efficacy.

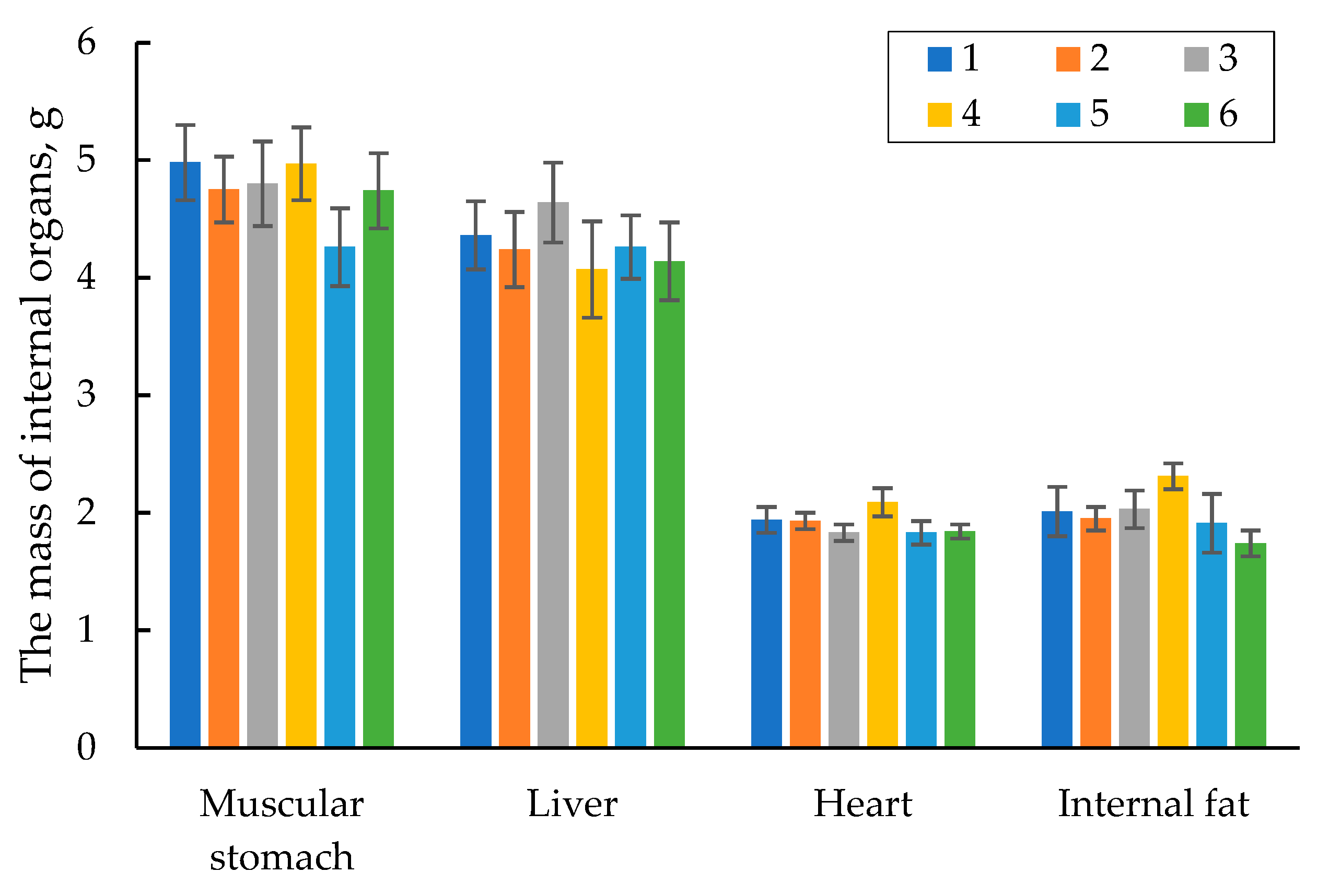

Figure 4.

Meat qualities (A) and Slaughter yield (B) of 42-day old quails. *- the difference in the mass of the gutted carcass of the experimental group 4 is reliable in relation to the experimental group 5 at p≤0.05; **- the difference in the mass of the gutted carcass of the experimental group 4 is reliable in relation to the experimental group 6 at p≤0.001.

Figure 4.

Meat qualities (A) and Slaughter yield (B) of 42-day old quails. *- the difference in the mass of the gutted carcass of the experimental group 4 is reliable in relation to the experimental group 5 at p≤0.05; **- the difference in the mass of the gutted carcass of the experimental group 4 is reliable in relation to the experimental group 6 at p≤0.001.

Figure 5.

The mass of internal organs of quails at 42 days.

Figure 5.

The mass of internal organs of quails at 42 days.

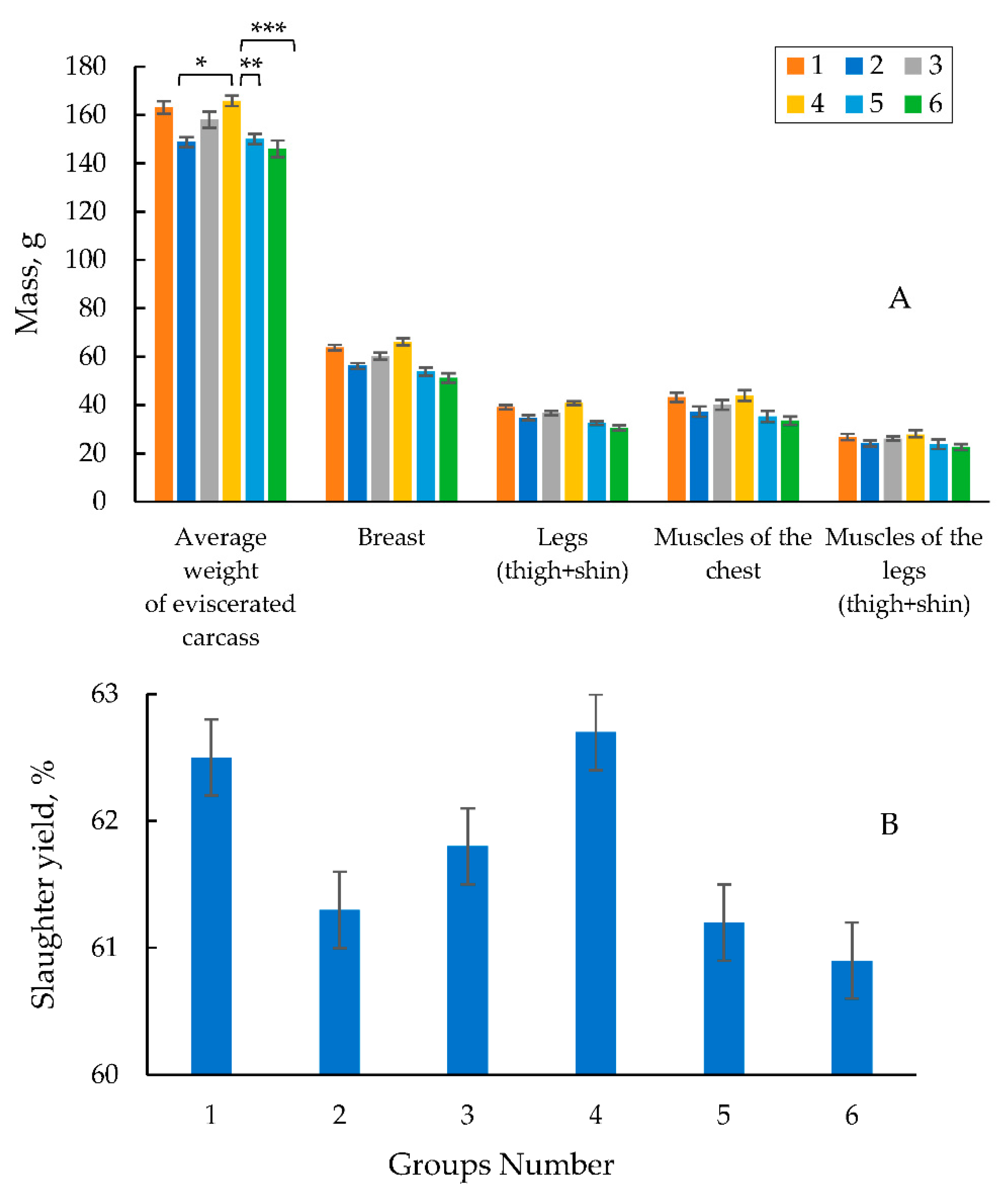

Figure 6.

Meat qualities (A) and Slaughter yield (B) of 60-day old quails. *,**, ***- the difference in weight of the eviscerated carcass in experimental group 4 is significant in relation to the control group 2 and experimental groups 5 and 6 at p≤0.001.

Figure 6.

Meat qualities (A) and Slaughter yield (B) of 60-day old quails. *,**, ***- the difference in weight of the eviscerated carcass in experimental group 4 is significant in relation to the control group 2 and experimental groups 5 and 6 at p≤0.001.

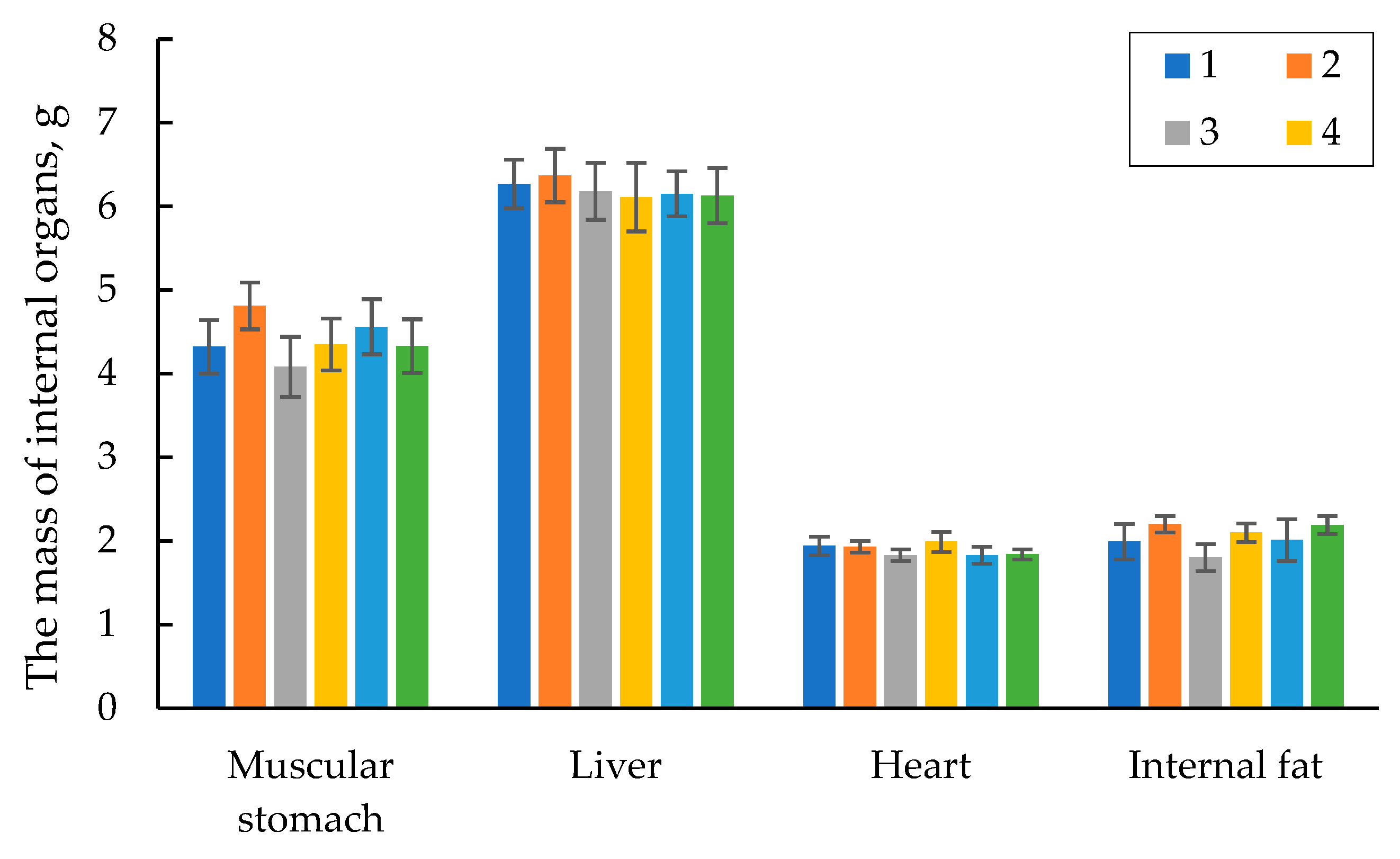

Figure 7.

The mass of internal organs of quails at 60 days.

Figure 7.

The mass of internal organs of quails at 60 days.

Table 1.

Body weight of the quails at different age, from 1 to 42 days of life, g (M ±m).

Table 1.

Body weight of the quails at different age, from 1 to 42 days of life, g (M ±m).

| Age of the poultry, days |

Groups Number |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 1 |

8.0±0.00 |

8.0±0.00 |

8.0±0.00 |

8.0±0.00 |

8.0±0.00 |

8.0±0.00 |

| 7 |

39.2±0.52 |

37.5±0.68 |

38.2±0.50 |

38.5±0.55 |

39.0±0.51 |

37.88±0.68 |

| 14 |

80.4±1.08 |

78.7±1.08 |

78.8±1.06 |

80.9±0.89 |

81.0±1.14 |

79.6±1.38 |

| 21 |

140.9±1.81 |

138.9±1.87 |

139.7±1.47 |

141.0±1.43 |

139.0±1.80 |

136.3±1.94 |

| 28 |

171.8±1.88 |

168.2±2.24 |

167.9±1.69 |

168.2±1.80 |

166.6±2.19 |

164.4±2.18 |

| 35 |

197.9±3.52 |

195.9±4.90 |

196.5±2.73 |

200.0±3.28 |

194.2±2.92 |

192.1±3.61 |

| 42 days: |

|

hens

roosters

average |

238.5±4.04194.7±4.73217.7±6.55 |

239.4±5.39

190.6±4.89

215.5±5.70 |

236.3±3.60

191.7±4.14

214.2±4.84 |

240.4±4.15

196.9±3.94**

218.1±5.54 |

233.9±6.96

189.0±4.23

211.2±5.36 |

235.6±6.09

180.3±3.18

206.8±6.42 |

| % to control 1 |

100 |

100 |

-1.6 |

+0.2 |

-3.0 |

-5.0 |

| % to control 2 |

100 |

100 |

-0.6 |

+1.2 |

-2.0 |

-4.0 |

Table 2.

Zootechnical features and FCR* of the 42-days old quails.

Table 2.

Zootechnical features and FCR* of the 42-days old quails.

| |

Groups Number |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Percent alive, % |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Average daily gain, g |

4.99±0.13 |

4.94±0.15 |

4.91±0.09 |

5.00±0.1 |

4.84±0.11 |

4.73±0.13 |

| Feed consumption per a head per a day, g |

19.66±0.8 |

19.71±0.7 |

19.43±0.8 |

19.59±0.9 |

19.66±0.8 |

19.33±0.9 |

| Feed consumption per a kg of live weight, kg |

3.75±0.3 |

3.80±0.2 |

3.77±0.4 |

3.73±0.3 |

3.87±0.2 |

3.89±0.1 |

| FCR* |

3.99 |

3.99 |

3.95 |

3.91 |

4.06 |

4.08 |

Table 3.

The yield of parts and muscles from the mass of the eviscerated carcass, %.

Table 3.

The yield of parts and muscles from the mass of the eviscerated carcass, %.

| |

Groups Number |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Yield of carcass parts:

breast

ham (thigh+shin) |

39.3±2.4

24.8±3.0 |

38.4±1.9

23.8±1.7 |

37.1±1.8

23.5±2.0 |

40.5±3.1

25.1±2.3 |

36.6±3.1

22.4±1.9 |

35.7±3.2

21.6±1.9 |

Yield of muscle parts:

breast (fillet)

legs (thigh+shin) |

27.3±1.9

17.0±1.2 |

26.5±1.7

16.9±1.2 |

25.3±1.7

16.2±1.3 |

28.4±1.8

18.1±1.3 |

24.2±1.9

15.5±1.4 |

23.8±1.8

15.1±1.4 |

Table 4.

Body weight of the 60-day old quails, g (M ±m).

Table 4.

Body weight of the 60-day old quails, g (M ±m).

| Groups Number |

Females |

Males |

Average live weight |

| 1 |

273.3 ± 5.78 |

211.5 ± 5.50 |

260.9 ± 9.48 |

| 2 |

251.3 ± 6.15 |

208.5 ± 2.50 |

242.7 ± 10.29 |

| 3 |

268.2 ± 6.80 |

206.5 ± 2.80 |

255.7 ± 9.92 |

| 4 |

276.3 ± 8.86*## |

218.4 ± 3.50*## |

264.7 ± 10.40* |

| 5 |

257.6 ± 6.34 |

196.5 ± 6.50 |

245.4 ± 9.48 |

| 6 |

249.1 ± 4.50 |

200.5 ± 4.50 |

239.4 ± 6.15 |

Table 5.

Zootechnical features of quails and FCR* from 42 to 60 days.

Table 5.

Zootechnical features of quails and FCR* from 42 to 60 days.

| |

Groups Number |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Percent alive, % |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Average daily gain, g |

2.4±0.2 |

1.51±0.1 |

2.31±0.1 |

2.59±0.2 |

1.90±0.2 |

1.81±0.2 |

| Feed consumption per 1 head per day, g |

33.49±2.3 |

33.02±2.4 |

31.95±2.4 |

32.82±2.3 |

33.15±2.4 |

32.75±2.1 |

| Feed expenses per average body weight, kg |

2.31±0.1 |

2.45±0.1 |

2.25±0.1 |

2.23±0.2 |

2.43±0.1 |

2.46±0.2 |

| Egg productivity, % |

77.1±4.8 |

73.6±4.6 |

77.8±4.7 |

86.8±4.9 |

75.0±4.5 |

77.8±4.6 |

| FCR* |

2.31 |

2.45 |

2.25 |

2.23 |

2.43 |

2.46 |

Table 6.

The output of the parts and muscles from the weight of the eviscerated carcass, %.

Table 6.

The output of the parts and muscles from the weight of the eviscerated carcass, %.

| |

Groups Number |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Yield of carcass parts:

breast

legs (thigh+shin) |

39.1±2.3

23.9±1.9 |

37.7±2.1

23.4±1.7 |

38.1±2.4

23.3±1.8 |

39.7±1.9

24.5±1.9 |

36.6±1.8

22.4±1.8 |

35.7±1.8

21.6±1.3 |

Muscle yield parts:

breast (fillet)

legs (thigh+shin) |

26.5±1.8

16.4±0.6 |

25.1±1.7

16.3±0.9 |

25.4±1.8

16.5±1.1 |

26.6±1.7

16.7±0.6 |

23.5±1.8

15.9±0.7 |

22.9±1.8

15.5±0.7 |

Table 7.

Chemical assay of macro- and microelements in the quail excreta.

Table 7.

Chemical assay of macro- and microelements in the quail excreta.

| Groups |

Macro-element amount,

% of dry weight |

Trace element amount, µg/g of dry weight |

| P |

Mg |

K |

Ca |

Zn |

Cu |

|

14days of the experiment

|

| 1 |

1.27 |

0.38 |

2.06 |

1.37 |

1148 |

92 |

| 3 |

0.96 |

0.36 |

2.05 |

1.01 |

1158 |

113 |

| 4 |

1.30 |

0.46 |

2.35 |

1.21 |

1071 |

89 |

| 5 |

1.24 |

0.39 |

2.19 |

1.04 |

1205 |

91 |

| 28 days of the experiment |

| 1 |

1.47 |

0.44 |

1.91 |

1.93 |

681 |

55 |

| 3 |

1.32 |

0.45 |

2.00 |

1.66 |

784 |

65 |

| 4 |

1.38 |

0.44 |

1.90 |

1.63 |

723 |

62 |

| 5 |

1.61 |

0.47 |

1.89 |

1.85 |

642 |

48 |

|

42days of the experiment

|

| 1 |

1.42 |

0.41 |

1.85 |

1.82 |

539 |

51 |

| 3 |

1.47 |

0.43 |

1.79 |

1.79 |

565 |

49 |

| 4 |

1.41 |

0.46 |

1.83 |

1.81 |

551 |

48 |

| 5 |

1.53 |

0.42 |

1.81 |

1.93 |

558 |

50 |

Table 8.

Chemical assay of macro- and microelements in the feed for the quails (start feed).

Table 8.

Chemical assay of macro- and microelements in the feed for the quails (start feed).

| Diets for the groups |

Macro-element amount, % of dry weight |

Trace element amount, µg/g of dry weight |

| P |

Mg |

K |

Ca |

Zn |

Cu |

| 1 |

0.71 |

0.23 |

1.31 |

1.05 |

373 |

41 |

| 2 |

0.61 |

0.28 |

1.27 |

1.37 |

366 |

64 |

| 3 |

0.73 |

0.24 |

1.40 |

1.42 |

448 |

49 |

| 4 |

0.69 |

0.21 |

1.30 |

0.93 |

246 |

30 |

| 5 |

0.73 |

0.22 |

1.34 |

1.16 |

340 |

42 |

| 6 |

0.58 |

0.22 |

1.39 |

0.90 |

320 |

41 |