1. Backgrounds

Cyclic neutropenia is a rare hematological disorder characterized by periodic fluctuations in blood neutrophil counts, with a 21-day turnover frequency [1-3].

Neutrophils are white blood cells (WBC) involved in immune defense. They play a crucial role in ingestion and killing of microorganisms, destruction of intra-cellular pathogens, and degradation of proteins such as immunoglobulin and coagulation factors. The alteration of their functions determines immunodeficiency and consequent development of recurrent infections [1, 4-6].

The genetic basis of the disease has been evaluated and established in molecular biology. Cyclic neutropenia is inherited as an autosomal-dominant mutation of the gene for neutrophil elastase (ELANE) with full penetrance but different severities of manifestation [1, 2, 4, 7].

Clinical presentation ranges from mild to severe forms of the disease, with an absolute neutrophil count < 0.2 x 109/L for a period of 3–5 days, recurrent fever, painful mouth ulcers, gingivitis, and bacterial infections such as sinusitis, otitis, pharyngitis and cellulitis [1, 3, 8]. Young patients can also manifest periodontitis and alveolar bone loss. Pneumonia, perianal abscesses, impaired fertility, septic shock, and bone necrosis represent rare manifestations of the disease. Symptoms usually become less severe and less frequent after adolescence [1-3, 9].

Due to heterogeneous symptoms in children, diagnosis of cyclic neutropenia represents a challenge for physicians, usually requiring a multidisciplinary approach for the diagnostic work-up and treatment [1, 4].

Effective and safe therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) has revolutionized the management of the disease. It consists in daily or alternate daily subcutaneous injection, which can reduce the duration of neutropenia and the turnover of the cells [1, 2, 6, 8].

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that affects the gastrointestinal tract. The incidence of CD is increasing worldwide [10-12]. Symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, weight loss and malnutrition. Extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) are frequently reported, affecting up to 40% of patients [10, 13, 14].

Endoscopy and imaging techniques, such as bowel ultrasound, small bowel magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomographic (CT) enterography, are the diagnostic tools used for the diagnosis and management of CD [

10].

The focus of IBD treatment has changed in recent years with the introduction of biological therapies, moving from the treatment of symptoms to "deep remission" [10, 11, 15-17].

These chronic diseases affect young people and, due to their relapsing/remitting course, the presence of EIMs and the necessity of surgery, have an important impact on the quality of life and the development of disabilities [16, 18].

The association between CD and cyclic neutropenia is rarely reported in the literature. Their differential diagnosis may be very complex, since they are both chronic diseases with aspecific symptoms that affect young people.

Here, we describe two clinical cases of young men diagnosed with CD. They underwent surgery because of complicated CD. After surgery, they were diagnosed with cyclic neutropenia, and they both started G-CSF with benefits.

2. Case Report 1

In 2020, a 31-year-old patient presented with chronic diarrhea and right low quadrant pain, which were associated with recurrent mouth ulcers; he mentioned that he had been suffering from recurrent otitis since childhood. Abdominal ultrasound was performed and the result seemed normal. Therapy with antibiotics and probiotics was prescribed but there was no improvement in clinical symptoms. In 2021, he reported to our Gastroenterological Department with worsening abdominal pain and fever (up to 39° C). Physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness and guarding in the right lower quadrant. Bowel ultrasound was performed, which showed increased bowel wall thickness of the ileum and the presence of a peri-ileal phlegmon. The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) scan and ileo-colonoscopy which showed that he had penetrating ileal CD.

Laboratory tests gave the following results: WBC 2500 x103/UL (neutrophils 39%) and C-reactive protein 45 mg/L.; this data was interpreted as a consequence of a gram-negative septic process.

Still in 2021, the patient underwent ileo-colic resection with temporary ileostomy.

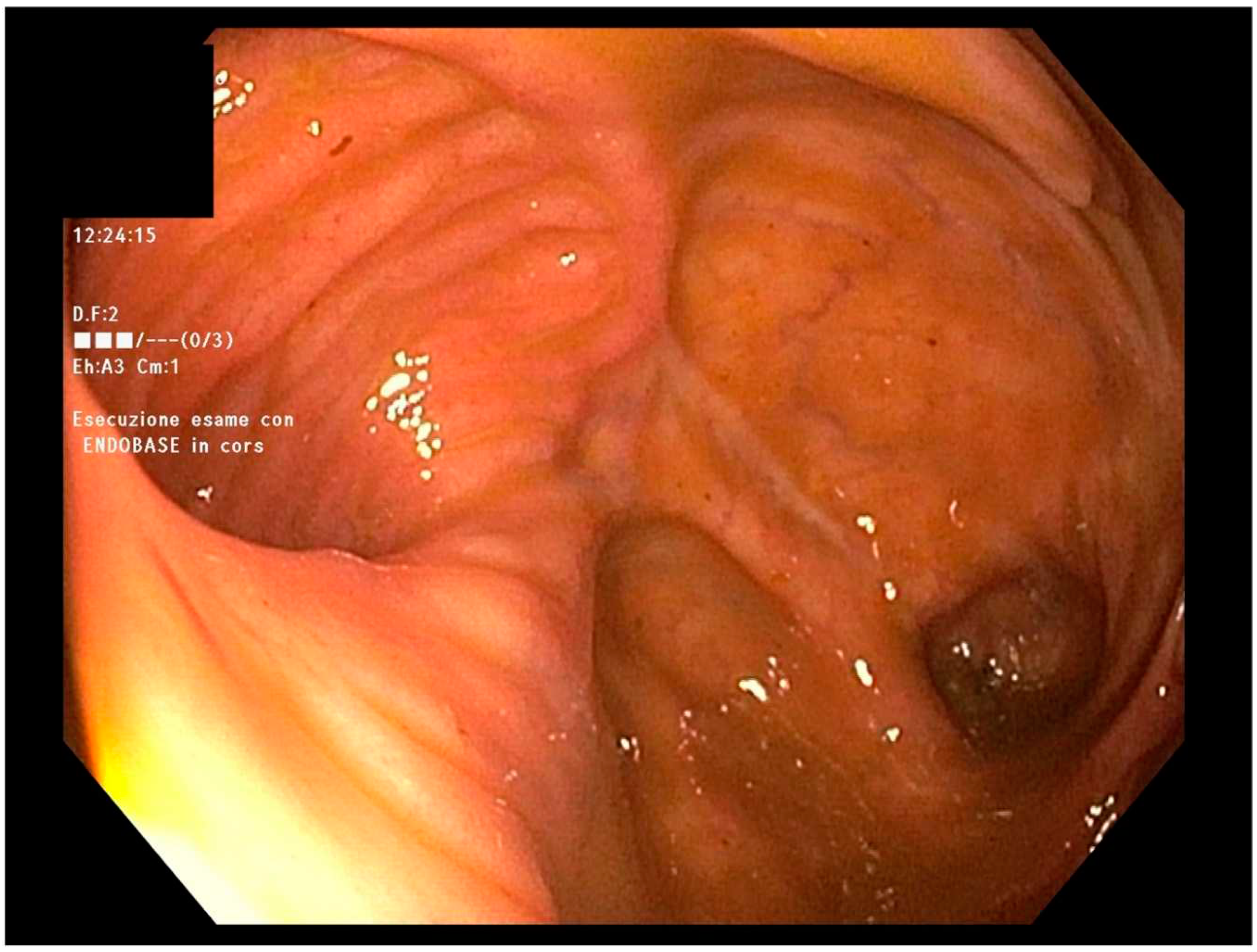

In April 2022, endoscopic evaluation was performed (

Figure 1), with evidence of regular ileo-colic anastomosis and mild mucosal erythema of the left colon.

On outpatient visit, the patient referred well-being. After undergoing laboratory tests, leukopenia was found to be still present (WBC: 1.93 x 103/UL; neutrophils: 40%). One month later, his WBC count was found to be stable at 2.100 x 103/UL (neutrophils: 37%).

The patient had not used any medications, toxins or alcohol. There was no family history of neutropenia.

So, a hematological evaluation was required for suspected CD-like ileitis in patients with “cyclic neutropenia”. The hematologist at our hospital confirmed the diagnosis. Additional tests, such as the detention of ELANE mutation, were not performed. G-CSF was started, leading to normalization of blood cell counts and alleviation of intestinal symptoms.

In November 2022, he underwent surgery for reversal of ileostomy; laboratory tests were in range. Blood routine tests gave a WBC count of 7.33 x 103/UL.

At the time of writing, the patient is well and still undergoing therapy with G-CSF, without any recurrence of neutropenia or endoscopic and clinical signs of ileitis or Crohn’s disease.

Figure 1.

The normal anastomotic picture at endoscopy.

Figure 1.

The normal anastomotic picture at endoscopy.

3. Case report 2

In 2017, a 25-year-old patient, with a history of recurrent pharyngitis and oral aphthosis since adolescence, presented with abdominal pain and diarrhea. Ileo-colonoscopy with biopsies and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) were performed, and a diagnosis of ileo-colic Crohn’s disease (CD) was made. He started therapy with mesalamine and a cycle of steroids, with partial clinical benefits.

In 2019, after clinical recurrence of the disease, ileo-colonoscopy and MRE were performed again, which showed the presence of stenosing ileo-colic CD. Histological examination of colic specimens confirmed active CD. No surgical evaluation was made.

In these two years, laboratory tests showed persistence of neutropenia (WBC ranged from 1.900 x 103 UI/L to 2.900 x103 UI/L; neutrophils ranged from 30% to 49%). A hematological consultant suggested undergoing a bone marrow biopsy, and the results appeared normal.

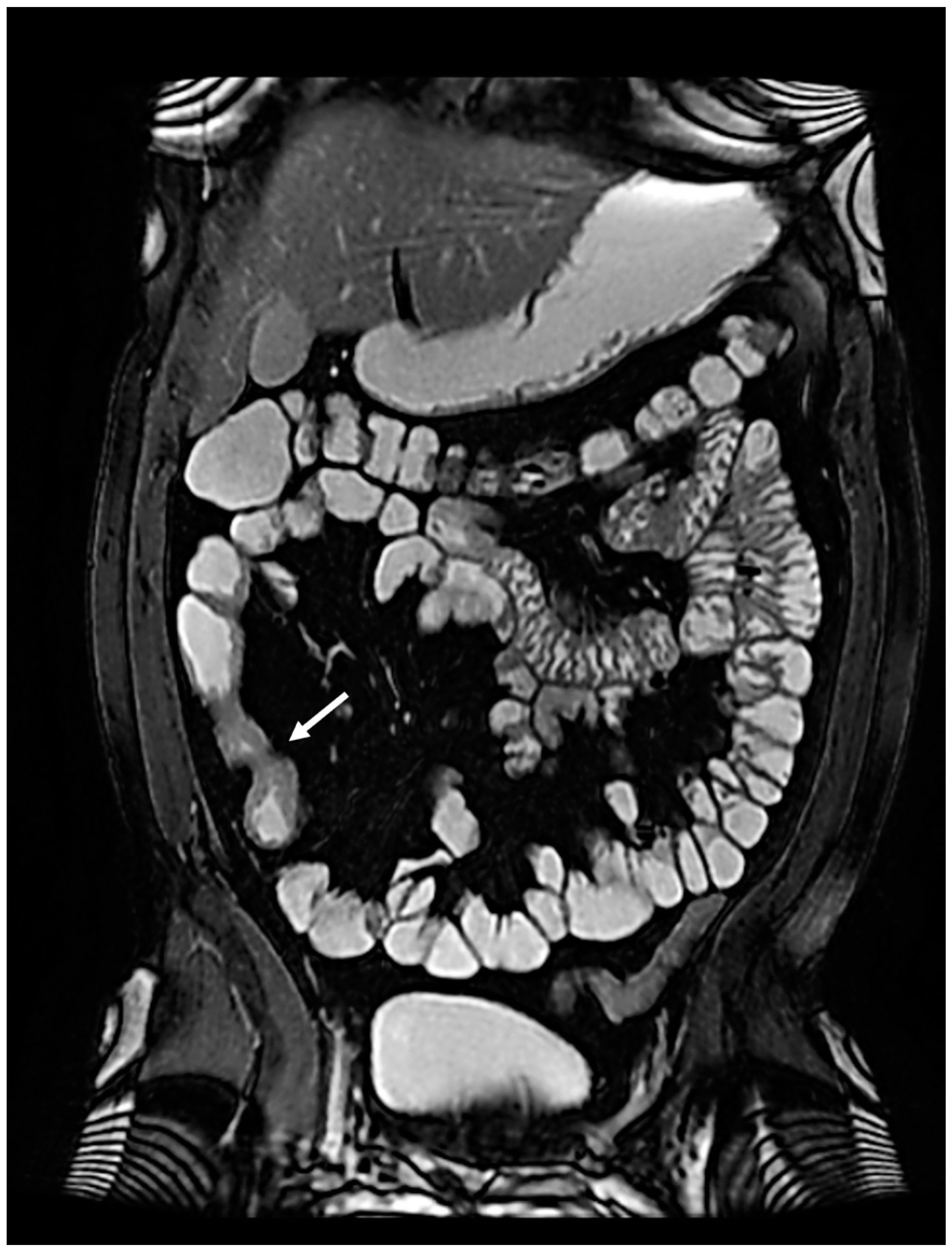

In January 2022, the patient complained of worsening abdominal pain localized in the right low quadrant, so ileo-colonoscopy and MRE were performed again, confirming the presence of stenosis of the terminal ileum and ascending colon (

Figure 2).

In December 2022, the patient reported to our Gastroenterological Department; bowel ultrasound was performed, showing bowel thickening in the ileum, caecum, and ascending colon, with the presence of an ileal-mesenteric fistula.

In January 2023, he underwent ileo-colic resection at our Surgical Department. After surgery, WBC remained stable between 2.43 x 103/UL to 2.85 x 103/UL with associated evidence of neutropenia.

After hematological consultation, the diagnosis changed from CD to cyclic neutropenia, and therapy with G-CSF was started, with rapid normalization of WBC. As at the time of writing this report, his condition is still stable without any intestinal symptoms, and no endoscopic sign of inflammation is evident at the site of ileo-colic anastomosis.

Figure 2.

The suspected stenosing Crohn’s disease at MRE (arrow).

Figure 2.

The suspected stenosing Crohn’s disease at MRE (arrow).

4. Narrative review and discussion

Neutrophil cells are the most represented sub-population of leukocytes, constituting the first line of the innate immune system, which is implicated in the release of inflammatory chemical mediators such as leukotrienes, prostaglandins, proteases and free radicals. They can ingest and kill microorganisms, destroy intracellular pathogens, and degrade proteins such as immunoglobulins and coagulation factors [1, 4-6].

In the general population, the blood neutrophil count ranges from 2.0 x 10

9/L to 7.0 x 10

9/L, deriving from the hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) that differentiate into myeloid progenitor cells, which in turn differentiate into granulocyte–monocyte, and then into neutrophils

[2, 3]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) represents the main factor involved in the proliferation and maturation of neutrophils from bone marrow [

3].

Neutropenia is a condition defined as a decrease in the neutrophil count below 2.0 x 109/L; severe neutropenia is characterized by neutrophil counts less than 0.5 x 109/L, leading to elevated susceptibility to infections [1, 2].

Cyclic neutropenia is a rare, benign hematological condition affecting one in a million persons in the general population. It is characterized by periodic fluctuations in neutrophil counts, with a 21-day periodicity. Alteration of the neutrophil level leads to immunodeficiency and consequent development of recurrent infections [1-3].

In recent years, research in molecular biology has to the understanding of the genetic basis of the disease. It is inherited as autosomal-dominant mutation of the gene for neutrophil elastase (ELANE), with full penetrance but different severities of manifestations [1, 2, 4]. Elastase is one of the four serine proteases found in neutrophil granules. Its defect determines the cessation of myelocyte maturation. The mutation can be found in all familiar members affected by cyclic neutropenia, with no differences according to sex, and is not detectable in unaffected familiar members [3, 4].

Linkage analysis has shown that the alteration of the ELANE gene (also referred to as ELA2, HLE or NE) is localized in the chromosome 19p13.3, in the exon 4 or 5 of the gene, or at the junction of exon 4 and intron 4, determining aberrant function with alteration in the development of the myeloid precursor, with cell loss and neutropenia [1, 3, 4, 8].

Heterozygous mutation of the gene determines the onset of cyclic neutropenia, a mild to moderate form of the disease, as well as severe neutropenia, which is life-threatening [

3].

Sporadic cases can occur in patients with so-called acquired neutropenia, with late onset of the disease [

2].

The pathophysiological mechanism is attributable to an intrinsic defect in the hematopoietic stem cells, leading to cyclic oscillation in the maturation of neutrophils with a pause at the promyelocyte or myelocyte stage [

3]. According to a mathematical model proposed by Mackey, oscillation in count cells is the consequence of impaired hematopoiesis in acquired neutrophilia

[1, 19].

Clinical presentation can vary from mild to severe form, including recurrent severe neutropenia with evidence of absolute neutrophil count <0.2 x 109/L for 3–5 days, recurrent fever, oral mucosal ulcers, gingivitis, and recurrent bacterial infections such as sinusitis, otitis, pharyngitis, and cellulitis [1, 3, 8].

Opportunistic infections may also occur as dermatological infections. Young patients can also manifest swollen lymph nodes, periodontitis and alveolar bone loss. Pneumonia, perianal abscesses, and impaired fertility affecting women but not men are rarely present [

2]. Women showed and higher rate of abortions and 50% of their children inherit cyclic neutropenia. Septic shock, peritonitis and bone necrosis represent the more serious but rare manifestations of the disease

[2, 3, 9]. Symptoms usually become less severe and less frequent after adolescence and therapy with antibiotics is frequently required. Cyclic neutropenia is not associated with increased risk of malignancy or conversion to leukemia

[2, 3].

Diagnosis in children may be a challenge for physicians due to non-specificity of symptoms and may require a multidisciplinary approach involving a hematologist, a gastroenterologist, an infectious disease specialist, a geneticist, a radiologist, and a dentist [

4].

A proper diagnostic flowchart includes the evaluation of familiar history, clinical symptoms and oncological markers, blood counts, bone biopsy, X-ray, ultrasound, and computerized tomography (CT). A DNA study may be used to confirm the diagnostic suspicion [

4].

Regarding laboratory tests, blood counts should be obtained 3 days a week for 6 weeks, with demonstration of counts below 0.2 x 10

9/L [

2].

A diagnostic dilemma for the physician is represented by differential diagnosis of several conditions, such as infectious disorders, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Bechet’s disease, Mediterranean fever syndrome and other hereditary disorders, but also by the use of drugs as well as chemotherapy [2, 4].

Different therapeutic approaches were tried in the past, including splenectomy, androgens, steroids and lithium, without any success [

6].

The availability of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) has revolutionized the management and natural history of cyclic neutropenia [

8]. Administration of myeloid growth factor or G-CSF is currently the most efficacious therapy for cyclic neutropenia, with a good clinical response. It consists in daily or alternate daily subcutaneous injection and can regulate the proliferation, differentiation and maturation of the progenitor cells, reducing the duration of neutropenia and shortening the turnover of the cells form 21 days to 14 days

[2, 6]. The usual dose is 2–5 mg/kg/day and well tolerated by patients. Adverse events are dose-dependent and commonly represented by headaches, mild bone pain and osteoporosis. Development of myeloid leukemia is not considered a complication of the disease

[2, 6].

Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has been used as therapy for cyclic neutropenia, with less efficacy than G-CSF [

1].

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a transmural chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that affects the gastrointestinal tract, especially the terminal ileum and colon

[11, 12]. Clinical manifestations include diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, weight loss and anorexia. Extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) are also frequently reported, affecting up to 40% of patients [

10]. The etiopathogenesis of this IBD is still unclear, but the association with genetic and environmental factors has been demonstrated

[20-22]. The incidence is increasing worldwide with about 2.5 million people affected in Europe especially young adults

[23-25].

CD diagnosis is often challenging and requires the definition of location, extent, severity, and type of disease, as well as the exclusion of complications and EIMs. Endoscopy, imaging techniques (bowel ultrasound, small bowel MR or CT enterography) and non-invasive disease markers (for example: fecal calprotectin) are tools used for the diagnosis and evaluation of the remission/recurrence of the disease

[10, 14]. Since the advent of targeted biologic therapies, the therapeutic landscape of IBD has undergone a radical transformation with the goal to induce and maintain remission [

11]. A better understanding of the mucosal immune system and the genetics involved in the pathogenesis of IBD in recent decades has led to a more ambitious disease control strategy that can change the natural course of the pathology [

11]. The focus of IBD therapy, which includes conventional therapies and biological therapies, has moved from treatment of symptoms to "deep remission," including clinical and endoscopic–radiological remission

[10, 15-17].

The complexity of CD, the chronic relapsing course, the young age of most patients at diagnosis, the variability of therapeutic effects, the risk of adverse events, and the frequent need for surgery greatly impact the patient’s quality of life and tendency to develop a disability [16, 18]. According to one intriguing theory, judging by the impaired inflammatory response and altered role of macrophages in the removal of pathogens, IBD may be considered as a stage of a complex immunodeficiency [20, 22]. Rare cases of IBD with early onset are associated with a phagocyte immunodeficiency background, and some genes related to phagocyte function are linked to IBD. The development of an irregular inflammatory response has led to the consideration of IBD as a model disease in order to recognize factors that regulate the mucosal immune system [20, 22].

The association between CD and cyclic neutropenia is a very rare condition. Fata et al. described a case of a 40-year-old patient who, in 1985, was diagnosed with ileo-colic CD associated with cyclic neutropenia but not with any immunosuppressive therapy [

6]. From 1989 routine blood tests revealed the presence of neutropenia. Bone marrow aspirations and biopsies, at two different times, showed no form of alteration. In 1995, the patient had central catheter (used for parenteral nutrition) infection caused by

Staphylococcus aureus, which was treated with intravenous administration of vancomycin for 4 weeks and by removal of the catheter [

6]. Evidence of persistence of cyclic neutropenia with a 14-day turnover, despite CD remission, led to the adoption of G-CSF therapy, with resolution of the sepsis. An attempt to interrupt G-CSF therapy led to reduced neutrophil counts again, but the neutrophils increased in range when G-CSF was re-started [

6].

Lamport described another case of a woman affected by CD and associated neutropenia whose diagnosis became clear only when CD was in remission and the patient had stopped any therapy [

26].

Dale et al. reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who had recurrent infections (otitis, pneumonia, and pharyngitis) in early childhood and was now diagnosed with cyclic neutropenia. Lithium therapy was started. Four months later, he complained of abdominal pain and chills. He was hospitalized and diagnosed with acute abdomen with septic shock complication. Urgent colectomy was performed, but unfortunately the child died few hours later. Autopsy revealed a necrotizing enterocolitis with

Clostridium perfringens infection [

27].

These cases in the literature show how cyclic neutropenia may manifest not only with mild recurrent infections but also with severe clinical conditions, such as sepsis or fatal enterocolitis, underlining the crucial role of proper diagnosis and treatment.

5. Conclusion

CD and cyclic neutropenia are two chronic diseases with a heterogeneous, often overlapping spectrum of symptoms that affect young adults. Their differential diagnosis is difficult. Only a few cases of association between CD and neutropenia are described in the literature, but the existence of conditions of undiagnosed cyclic neutropenia mimicking CD, as in our experience, is plausible. In this regard, a correct anamnestic collection aimed at evaluating the presence of recurrent and periodic infections, the evaluation of laboratory tests and instrumental examinations, and possible genetic analysis may lead to a proper diagnosis and correct therapeutic approach.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions

ADG: manuscript conception and design, data acquisition, writing & editing of the manuscript, tables and approval. AR: editing of the manuscript, critical review of the manuscript, revision, overall supervision and final approval. FC: critical review of the manuscript, revision, overall supervision and final approval. GL and FPT: performed surgery. NI; GC; NP; AT; OO: edited the manuscript and actively followed-up the patients. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

-

Dale DC, Bolyard AA, Aprikyan A. Cyclic neutropenia. Semin Hematol. 2002 Apr;39(2):89-94. doi: 10.1053/shem.2002.31917. PMID: 11957190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Dale DC, Welte K. Cyclic and chronic neutropenia. Cancer Treat Res. 2011;157:97-108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7073-2_6. PMID: 21052952. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Rydzynska Z, Pawlik B, Krzyzanowski D, Mlynarski W, Madzio J. Neutrophil Elastase Defects in Congenital Neutropenia. Front Immunol. 2021 Apr 22;12:653932. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.653932. PMID: 33968054; PMCID: PMC8100030. [CrossRef]

-

Zergham AS, Acharya U, Mukkamalla SKR. Cyclic Neutropenia. 2023 May 22. Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 32491328. [PubMed]

-

Higa A, Eto T, Nawa Y. Evaluation of the role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of acetic acid-induced colitis in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997 Jun;32(6):564-8. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025100. PMID: 9200288. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Fata F, Myers P, Addeo J, Grinberg M, Nawabi I, Cappell MS. Cyclic neutropenia in Crohn’s ileocolitis: efficacy of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997 Jun;24(4):253-6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199706000-00015. PMID: 9252852. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Aprikyan AA, Dale DC. Mutations in the neutrophil elastase gene in cyclic and congenital neutropenia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001 Oct;13(5):535-8. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00254-5. PMID: 11543999. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Chen X, Peng W, Zhang Z, Wu Y, Xu J, Zhou Y, Chen L. ELANE gene mutation-induced cyclic neutropenia manifesting as recurrent fever with oral mucosal ulcer: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Mar;97(10):e0031. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010031. PMID: 29517659; PMCID: PMC5882443. [CrossRef]

-

Lahlimi FE, Khalil K, Lahiaouni S, Tazi I. Neutropenic Enterocolitis Disclosing an Underlying Cyclic Neutropenia. Case Rep Pediatr. 2020 Dec 1;2020:8858764. doi: 10.1155/2020/8858764. PMID: 33343958; PMCID: PMC7725567. [CrossRef]

- Fernando Gomollón, Axel Dignass, Vito Annese, Herbert Tilg, Gert Van Assche, James O. Lindsay, Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet, Garret J. Cullen, Marco Daperno, Torsten Kucharzik, Florian Rieder, Sven Almer, Alessandro Armuzzi, Marcus Harbord, Jost Langhorst, Miquel Sans, Yehuda Chowers, Gionata Fiorino, Pascal Juillerat, Gerassimos J. Mantzaris, Fernando Rizzello, Stephan Vavricka, Paolo Gionchetti, on behalf of ECCO, ‘’3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management.’’ Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, Volume 11, Issue 1, January 2017, Pages 3–25.

-

Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, Adamina M, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gomollon F, González-Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Spinelli A, Stassen L, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Warusavitarne J, Zmora O, Fiorino G. ‘’ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment.’’ J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Jan 1; 14 (1): 4-22. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180. PMID: 31711158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan GG. ‘’The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025.’’ Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Dec; 12 (12): 720-7. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150. Epub 2015 Sep 1. PMID: 26323879. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011 Apr;7(4):235-41. PMID: 21857821; PMCID: PMC3127025.

-

Greuter T, Vavricka SR. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease - epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Apr;13(4):307-317. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2019.1574569. Epub 2019 Feb 20. PMID: 30791773. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrisani G, Guidi L, Papa A, Armuzzi A. ‘’Anti-TNF alpha therapy in the management of extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease.’’ Eur Rev Med Pharmacol 2012; 16: 890-901.

- Allen PB, Gower-Rousseau C, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Preventing disability in inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017 Nov; 10 (11): 865-876. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17732720. Epub 2017 Oct 16. PMID: 29147137; PMCID: PMC5673018. [CrossRef]

-

Ungaro RC, Yzet C, Bossuyt P, Baert FJ, Vanasek T, D’Haens GR, Joustra VW, Panaccione R, Novacek G, Reinisch W, Armuzzi A, Golovchenko O, Prymak O, Goldis A, Travis SP, Hébuterne X, Ferrante M, Rogler G, Fumery M, Danese S, Rydzewska G, Pariente B, Hertervig E, Stanciu C, Serrero M, Diculescu M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Laharie D, Wright JP, Gomollón F, Gubonina I, Schreiber S, Motoya S, Hellström PM, Halfvarson J, Butler JW, Petersson J, Petralia F, Colombel JF. Deep Remission at 1 Year Prevents Progression of Early Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul;159(1):139-147. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.039. Epub 2020 Mar 26. PMID: 32224129; PMCID: PMC7751802. [CrossRef]

- Marinelli C, Savarino E, Inferrera M, Lorenzon G, Rigo A, Ghisa M, Facchin S, D’Incà R, Zingone F. Factors Influencing Disability and Quality of Life during Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study on IBD Patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019 Aug 21; 2019: 5354320. doi: 10.1155/2019/5354320. PMID: 31531015; PMCID: PMC6721452. [CrossRef]

- Mir P, Klimiankou M, Findik B, Hähnel K, Mellor-Heineke S, Zeidler C, Skokowa J, Welte K. New insights into the pathomechanism of cyclic neutropenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020 Apr;1466(1):83-92. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14309. Epub 2020 Feb 21. PMID: 32083314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Tommasini A, Pirrone A, Palla G, Taddio A, Martelossi S, Crovella S, Ventura A. The universe of immune deficiencies in Crohn’s disease: a new viewpoint for an old disease? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct;45(10):1141-9. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.492529. PMID: 20497046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh N, Bernstein CN. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022 Dec;10(10):1047-1053. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12319. Epub 2022 Oct 19. PMID: 36262056; PMCID: PMC9752273. [CrossRef]

-

Glocker E, Grimbacher B. Inflammatory bowel disease: is it a primary immunodeficiency? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012 Jan;69(1):41-8. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0837-9. Epub 2011 Oct 14. PMID: 21997382. [CrossRef]

- de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. ‘’Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art.’’ Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan; 13 (1): 13-27. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186. Epub 2015 Dec 2. PMID: 26627550. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen ML, Sundrud MS. ‘’Cytokine networks and T-cell subsets in inflammatory bowel diseases.’’ Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016; 22: 1157-11. [CrossRef]

-

Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. ‘’Crohn’s disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management.’’ Mayo Clin Proc 2017; 92: 1088-1103. [CrossRef]

-

Lamport RD, Katz S, Eskreis D. Crohn’s disease associated with cyclic neutropenia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992 Nov;87(11):1638-42. PMID: 1442691. [PubMed]

-

Dale DC, Hammond WP 4th. Cyclic neutropenia: a clinical review. Blood Rev. 1988 Sep;2(3):178-85. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(88)90023-9. PMID: 3052663. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).